Alec Gibson, a Tribute and a Thank You

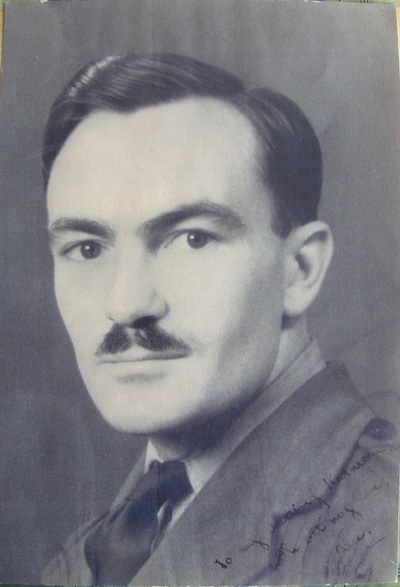

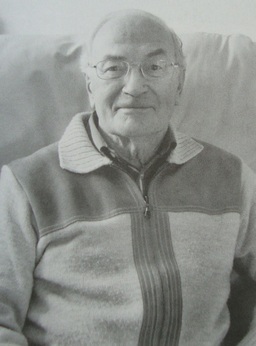

Alec McKay Gibson in 2011.

Alec McKay Gibson in 2011.

Alec McKay Gibson passed away on the 3rd November 2015, he was 94 years old. I first made contact with Alec in September 2008, after being introduced by another Burma veteran friend of his, Tom Webb. Over the next five years or so, we enjoyed several telephone conversations and letter exchanges. Alec was always very generous to me with both his time and knowledge and as my own research into the first Chindit expedition evolved, he showed great interest in what I had managed to uncover.

His intimate knowledge in regards to the first Wingate expedition, and possibly more so in relation to his experiences as a prisoner of war, are already recorded in many places amongst the pages of this website. However, I wanted to acknowledge his contribution just one more time, as a way of saying thank you.

Alec Gibson was born on the 14th January 1921. He volunteered for military service even though he was in a reserved occupation, working as an apprentice draughtsman for Hawker Aircraft at their Kingston factory. Aged just 18, his first posting was as a private soldier in the East Surrey Regiment, where his duties included coastal defence.

In due course, he was recommended for a commission as an officer, but opportunities in the British Army were few and far between. He then applied and was successful in gaining a commission into the Indian Army, taking up a posting with the 8th Gurkha Rifles at their Quetta Barracks in India. He was then called up to join the ranks of Wingate's force in January 1943 and with only three days notice, he had very little time to adjust or acclimatise to his new role. Alec arrived at the Chindit training centre along with other new boys, Ian MacHorton and Harold James and became Cypher Officer in Mike Calvert's 3 Column.

Alec remembered: They had been training for months but I had no jungle experience. In fact, I'd never been in the jungle! Furthermore, I spoke only a few words of Urdu and had no Gurkhali. Fortunately, I was extremely fit. The first day's march with full kit wasn't too bad, but the mules kept shedding their loads. I had the job of looking after those mules carrying wireless and other signals related equipment. This was a new experience, I was very cautious around the animals and managed to avoid getting kicked. I soon discovered that mules are cunning. They expand their bellies as the girth strap is tightened, frustrating all efforts to stop loads slipping. The trick was to give them a kick at exactly the right moment. Our mules had not been debrayed and made plenty of noise.

Alec recalled the crossing of the Chindwin as being "a bit of a shambles" and not inspiring him with any confidence. He recalled: "The river had a strong under-current it was quite formidable and at its widest about 200 yards across, I went back and forth three times that day, as we had some problems getting the mules across."

According to Alec, everyone in 3 Column got on well with each other, but communication across the length of the column snake was a problem. He was a great admirer of Mike Calvert: "He was a marvellous man, unsurpassed at map reading. At one stage we took an airdrop and Calvert decided to cache some stores in a jungle hideout. Several days later we returned to the exact same spot in the jungle and recovered some supplies. It was very impressive. He was a strong leader, yet very approachable."

As the operation continued 3 Column had their fair share of skirmishes with the Japanese, not least than during their demolition of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway at a place called Nankan. However, it became apparent, that whilst 3 Column were active and engaged, they produced their best work and morale remained high. Alec began to worry more, when the column crossed over the Irrawaddy in early March 1943 and probed deeper into occupied territory. Later that month and being Cypher officer, Lt. Gibson was one of the first men to learn of Wingate's decision to call off Operation Longcloth and order the men back to India. He particularly recalled the phrase that Wingate used in his radio message to the columns at that time: "Strive to save all valuable personnel." He also remembered how upset Mike Calvert was with these new orders and how his own commander dearly wanted to carry on with the operation.

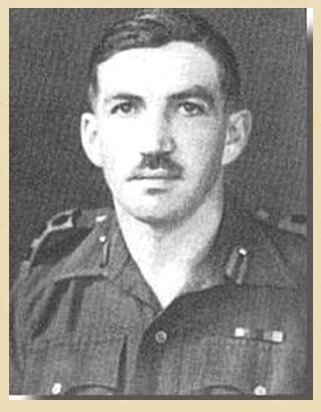

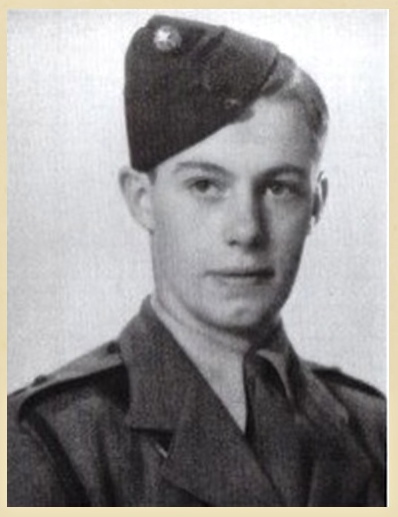

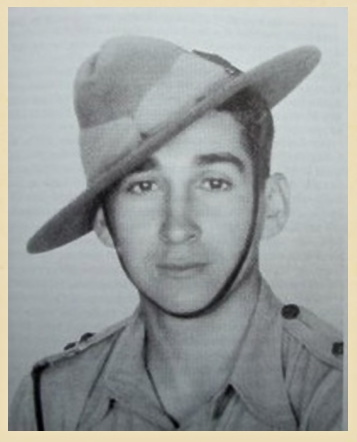

Seen below are photographs of Major Mike Calvert, 3 Column's commander in Burma and two of the young Gurkha officers who joined the Chindits on the same day as Alec Gibson in January 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

His intimate knowledge in regards to the first Wingate expedition, and possibly more so in relation to his experiences as a prisoner of war, are already recorded in many places amongst the pages of this website. However, I wanted to acknowledge his contribution just one more time, as a way of saying thank you.

Alec Gibson was born on the 14th January 1921. He volunteered for military service even though he was in a reserved occupation, working as an apprentice draughtsman for Hawker Aircraft at their Kingston factory. Aged just 18, his first posting was as a private soldier in the East Surrey Regiment, where his duties included coastal defence.

In due course, he was recommended for a commission as an officer, but opportunities in the British Army were few and far between. He then applied and was successful in gaining a commission into the Indian Army, taking up a posting with the 8th Gurkha Rifles at their Quetta Barracks in India. He was then called up to join the ranks of Wingate's force in January 1943 and with only three days notice, he had very little time to adjust or acclimatise to his new role. Alec arrived at the Chindit training centre along with other new boys, Ian MacHorton and Harold James and became Cypher Officer in Mike Calvert's 3 Column.

Alec remembered: They had been training for months but I had no jungle experience. In fact, I'd never been in the jungle! Furthermore, I spoke only a few words of Urdu and had no Gurkhali. Fortunately, I was extremely fit. The first day's march with full kit wasn't too bad, but the mules kept shedding their loads. I had the job of looking after those mules carrying wireless and other signals related equipment. This was a new experience, I was very cautious around the animals and managed to avoid getting kicked. I soon discovered that mules are cunning. They expand their bellies as the girth strap is tightened, frustrating all efforts to stop loads slipping. The trick was to give them a kick at exactly the right moment. Our mules had not been debrayed and made plenty of noise.

Alec recalled the crossing of the Chindwin as being "a bit of a shambles" and not inspiring him with any confidence. He recalled: "The river had a strong under-current it was quite formidable and at its widest about 200 yards across, I went back and forth three times that day, as we had some problems getting the mules across."

According to Alec, everyone in 3 Column got on well with each other, but communication across the length of the column snake was a problem. He was a great admirer of Mike Calvert: "He was a marvellous man, unsurpassed at map reading. At one stage we took an airdrop and Calvert decided to cache some stores in a jungle hideout. Several days later we returned to the exact same spot in the jungle and recovered some supplies. It was very impressive. He was a strong leader, yet very approachable."

As the operation continued 3 Column had their fair share of skirmishes with the Japanese, not least than during their demolition of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway at a place called Nankan. However, it became apparent, that whilst 3 Column were active and engaged, they produced their best work and morale remained high. Alec began to worry more, when the column crossed over the Irrawaddy in early March 1943 and probed deeper into occupied territory. Later that month and being Cypher officer, Lt. Gibson was one of the first men to learn of Wingate's decision to call off Operation Longcloth and order the men back to India. He particularly recalled the phrase that Wingate used in his radio message to the columns at that time: "Strive to save all valuable personnel." He also remembered how upset Mike Calvert was with these new orders and how his own commander dearly wanted to carry on with the operation.

Seen below are photographs of Major Mike Calvert, 3 Column's commander in Burma and two of the young Gurkha officers who joined the Chindits on the same day as Alec Gibson in January 1943. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Lieutenant Gibson and Lieutenant Ken Gourlay led one of the two dispersal groups consisting of HQ personnel from 3 Column; this party also contained a platoon of Gurkha Riflemen.

Alec recalled:

Navigation in the jungle is very difficult. It is absolutely critical to know exactly where you are when you start out. Naturally, it is impossible to follow an absolutely straight course in thick jungle and our maps were indifferent at best. Before we left we ditched all heavy equipment. We had no wireless and no means of calling up supply drops. We would be living off the land. There was the obvious possibility of being killed or wounded but I didn't give that much thought. I just assumed I'd be OK. Yet we all knew we would be left behind if we were wounded or became too ill to march.

Lt. Gibson calculated that it was about 120 miles to the Chindwin's east bank. Allowing for frequent diversions and ascents and descents in deep, narrow valleys, the actual distance would be closer to 180 miles.

After two days march the group reached the Irrawaddy. Here they searched the river bank for a suitable boat to get them across, unfortunately the Japanese had removed all such craft and villagers were reluctant to assist the Chindits for fear of reprisals. In the end Alec, Ken Gourlie and the rest of their group attempted to swim the mile wide river. Alec failed to reach the far bank on his first attempt and many others drowned in their own efforts to cross the river. Only one of the group successfully made the crossing that day. Deeply dispirited, the rest returned to their previous bivouac and slumped down to rest. Alec Gibson attempted to swim the river again sometime later, but lost consciousness in the process. When he finally came around, he found he was still on the eastern bank of the river, quite near the village of Taugaung.

In the book Marxism and Resistance in Burma 1942-1945, written by Thakin Thein Pe Myint, the town of Taugaung is described thus:

Taugaung is situated on a small hill that rests its chin on the Irrawaddy riverside. Although famous as a historical site from which all Burma is supposed to originate, it is more like a country village. There are no ancient buildings of any significance. The former town wall appears as an old rampart, with what was once the moat now just a dry bed. The government archaeology department had shown an interest, but no excavations had been completed. The ruined stupas are said to be from the reign of Abi Raza, the King of Taugaung and a descendant of the Sakya Kings of India. The Japanese seemed to hold the town in some reverence and we heard no bad reports about the Japanese from the townsfolk.

Exhausted and hungry, Alec and one other Gurkha soldier went into a nearby village to seek out some food. It was here that they were arrested by a group of local Burmese and handed over to the Japanese. Alec was now suffering very badly with bouts of dysentery. After capture he was interrogated thoroughly by the Japanese, but gave nothing important away. He and his fellow captive were taken to the railway town of Wuntho, where they met up with other Chindit POWs, not long after they were sent down to Maymyo by rail in cattle trucks. At Maymyo some 200 Chindits were assembled and were taught the harsh realities of prison life under the Japanese. Interrogations continued and on more than one occasion Alec was badly beaten after failing to answer questions about the intentions of Wingate's operation.

Eventually all Chindit POWs were sent to Rangoon Jail:

I was luckier than some. I had only five weeks in solitary confinement. The idea was to soften up the prisoner for interrogation. Eventually I was moved to the Officers Block. The treatment in Rangoon Jail was slightly better than at Maymyo, but we were beaten occasionally.

Alec spent two years in Rangoon before being liberated on 29th April 1945; he had been selected as one of the fitter men in the prison and chosen to accompany the retreating Japanese as they moved back into Thailand. Unexpectedly, this group of over 400 POWs were given their freedom close to the Burmese town of Pegu. Alec remembered his concern that his family would not know if he was even still alive. He also was aware of the physical and psychological effect his time in Japanese hands had placed on his own psyche and personality.

About his captors he said this: I felt real hatred towards our guards. We would have cheerfully killed them all, if we had been given the chance. I have no idea if they were ever brought to justice after the war. Our hatred did not come from our own suffering, but for all those unnecessary deaths of our men due to lack of medicines or good food.

Alec did not speak to his family about his experiences in Burma or as a prisoner of war in Rangoon. He did not really open up about his war time experiences until he returned to Burma in 1985 as part of a Royal British Legion tour for War Widows to visit their husbands graves in Rangoon War Cemetery. My own Nan would take up the opportunity to visit Rangoon War Cemetery on a similar pilgrimage just two years later.

Lt. Alec Gibson returned home to the United Kingdom in 1946 and married Kathleen. After leaving the Army, he elected not to return to his role in engineering, choosing instead, a new career in Local Government Finance.

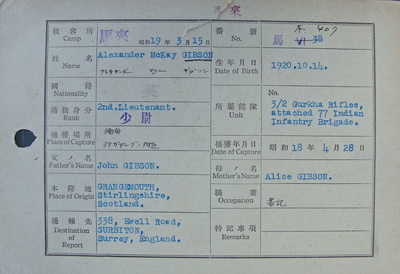

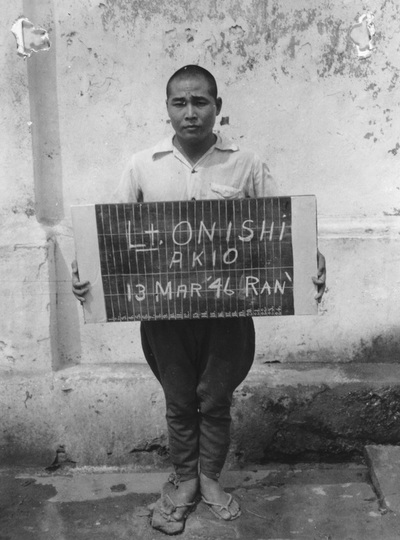

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to Alec Gibson and his time as a prisoner of war. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Alec recalled:

Navigation in the jungle is very difficult. It is absolutely critical to know exactly where you are when you start out. Naturally, it is impossible to follow an absolutely straight course in thick jungle and our maps were indifferent at best. Before we left we ditched all heavy equipment. We had no wireless and no means of calling up supply drops. We would be living off the land. There was the obvious possibility of being killed or wounded but I didn't give that much thought. I just assumed I'd be OK. Yet we all knew we would be left behind if we were wounded or became too ill to march.

Lt. Gibson calculated that it was about 120 miles to the Chindwin's east bank. Allowing for frequent diversions and ascents and descents in deep, narrow valleys, the actual distance would be closer to 180 miles.

After two days march the group reached the Irrawaddy. Here they searched the river bank for a suitable boat to get them across, unfortunately the Japanese had removed all such craft and villagers were reluctant to assist the Chindits for fear of reprisals. In the end Alec, Ken Gourlie and the rest of their group attempted to swim the mile wide river. Alec failed to reach the far bank on his first attempt and many others drowned in their own efforts to cross the river. Only one of the group successfully made the crossing that day. Deeply dispirited, the rest returned to their previous bivouac and slumped down to rest. Alec Gibson attempted to swim the river again sometime later, but lost consciousness in the process. When he finally came around, he found he was still on the eastern bank of the river, quite near the village of Taugaung.

In the book Marxism and Resistance in Burma 1942-1945, written by Thakin Thein Pe Myint, the town of Taugaung is described thus:

Taugaung is situated on a small hill that rests its chin on the Irrawaddy riverside. Although famous as a historical site from which all Burma is supposed to originate, it is more like a country village. There are no ancient buildings of any significance. The former town wall appears as an old rampart, with what was once the moat now just a dry bed. The government archaeology department had shown an interest, but no excavations had been completed. The ruined stupas are said to be from the reign of Abi Raza, the King of Taugaung and a descendant of the Sakya Kings of India. The Japanese seemed to hold the town in some reverence and we heard no bad reports about the Japanese from the townsfolk.

Exhausted and hungry, Alec and one other Gurkha soldier went into a nearby village to seek out some food. It was here that they were arrested by a group of local Burmese and handed over to the Japanese. Alec was now suffering very badly with bouts of dysentery. After capture he was interrogated thoroughly by the Japanese, but gave nothing important away. He and his fellow captive were taken to the railway town of Wuntho, where they met up with other Chindit POWs, not long after they were sent down to Maymyo by rail in cattle trucks. At Maymyo some 200 Chindits were assembled and were taught the harsh realities of prison life under the Japanese. Interrogations continued and on more than one occasion Alec was badly beaten after failing to answer questions about the intentions of Wingate's operation.

Eventually all Chindit POWs were sent to Rangoon Jail:

I was luckier than some. I had only five weeks in solitary confinement. The idea was to soften up the prisoner for interrogation. Eventually I was moved to the Officers Block. The treatment in Rangoon Jail was slightly better than at Maymyo, but we were beaten occasionally.

Alec spent two years in Rangoon before being liberated on 29th April 1945; he had been selected as one of the fitter men in the prison and chosen to accompany the retreating Japanese as they moved back into Thailand. Unexpectedly, this group of over 400 POWs were given their freedom close to the Burmese town of Pegu. Alec remembered his concern that his family would not know if he was even still alive. He also was aware of the physical and psychological effect his time in Japanese hands had placed on his own psyche and personality.

About his captors he said this: I felt real hatred towards our guards. We would have cheerfully killed them all, if we had been given the chance. I have no idea if they were ever brought to justice after the war. Our hatred did not come from our own suffering, but for all those unnecessary deaths of our men due to lack of medicines or good food.

Alec did not speak to his family about his experiences in Burma or as a prisoner of war in Rangoon. He did not really open up about his war time experiences until he returned to Burma in 1985 as part of a Royal British Legion tour for War Widows to visit their husbands graves in Rangoon War Cemetery. My own Nan would take up the opportunity to visit Rangoon War Cemetery on a similar pilgrimage just two years later.

Lt. Alec Gibson returned home to the United Kingdom in 1946 and married Kathleen. After leaving the Army, he elected not to return to his role in engineering, choosing instead, a new career in Local Government Finance.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to Alec Gibson and his time as a prisoner of war. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As mentioned previously, Alec and I exchanged several letters over the past six years or so; shown below are just a few examples of how much he helped me in my quest to find out more about the Chindits of 1943 in general and my own grandfather in particular.

Firstly, his reply to my original letter dated 21/09/2008. This was in answer to some very general questions about Operation Longcloth and well before I even knew which Chindit column my grandfather actually belonged to:

Dear Steve,

Since talking with you the other day, I have been rummaging through all my old papers about Burma and the Chindits, which has been fascinating! To answer some of your specific points:

Columns 1, 2, 3 and 4 were mainly composed of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles. Columns 5, 7 and 8 were the 13th King's; so your grandfather must have been in one of those columns I would say. The 13th King's were not a fighting unit and many of the older, less fit men were weeded out and replaced by other soldiers.

In relation to my time in Rangoon Jail; I was captured on the 26th April 1943 and transferred to the Maymyo Camp for several weeks. I was then transferred to Rangoon, where I was placed into solitary confinement for about five weeks before being moved to one of the open blocks. Your grandfather would therefore have died before I was released from solitary.

Colonel Henry Power of the Dogra Regiment did keep a record of all the burials at Rangoon, but I imagine that information would have gone to the War Graves Commission. In relation to my POW index card, perhaps mine is held by the Indian Army Office, due to my position with the 8th Gurkhas and is not at our National Archives. We never had a liberation debrief. We were the first POW's recovered from the Japanese and were under strict orders not to speak to anyone, especially the press. I believe this was because of the possible repercussions for those still held by the Japanese in Thailand and Singapore.

A letter dated 30/11/2008, in response to some POW documents I had been able to unearth.

Dear Steve,

Thanks for your phone call the other night. I enjoyed our chat, it took my mind off home just now where things have been difficult as my wife is now in hospital. I have to say, I am amazed at the amount of information you have dug out from different places and I wish you luck with in your future research. When we came back from the war, we were told that all documents and paperwork was strictly off-limits to us. Mind you, not many of us were looking to chase things up.

To answer some of your queries:

I did have contact with some of the officers from King's columns who were held in Rangoon; Philip Stibbe for example. However, you must appreciate that although we were in the same block at Rangoon, officers and men were not allowed to talk to one another, except of course on working parties.

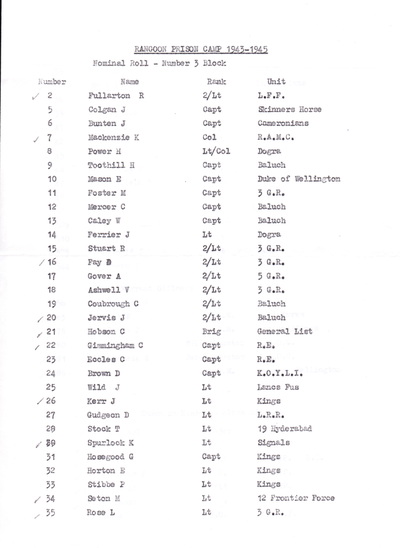

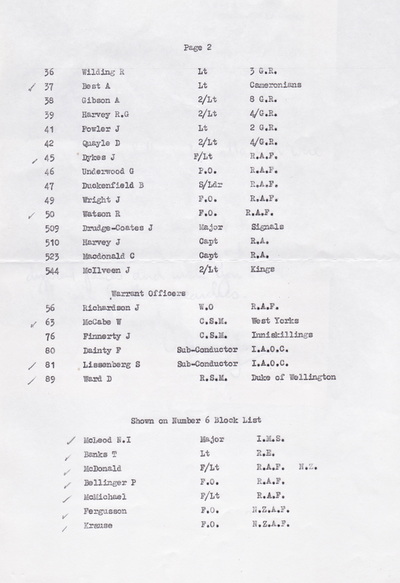

I was interested in the list of prisoners which you sent me. Incredibly, this must cover the vast majority of the 200 or so Chindits in the jail at Rangoon. I enclose a copy of a list which was salvaged by one of the officers from 3 Block during 1943-45. Thank you for my POW index card; so it was listed under the M's; I was listed on the Pay Roll as Lt. McKay Gibson, so that is the reason for the difficulty in finding my card in the first instance. In relation to my capture, I was captured somewhere near Taugaung on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy and then sent to Wuntho on the railway.

I do not know why the American's inside Rangoon were treated more harshly, but the Japanese were extremely scared of air-raids once 1944 came. It might also be that the Americans could be a little too 'cocky' at times, which never paid with the Japs.

The man who brought me food when I was in solitary confinement was George Leggate of the Cameronians. I met him again about 40 years after the war and we saw quite a bit of each other until he sadly died about 4 years go.

Seen below are the lists that Alec sent me, showing the officers present in 3 Block at Rangoon Jail. Please click on either image to bring to forward on the page.

Firstly, his reply to my original letter dated 21/09/2008. This was in answer to some very general questions about Operation Longcloth and well before I even knew which Chindit column my grandfather actually belonged to:

Dear Steve,

Since talking with you the other day, I have been rummaging through all my old papers about Burma and the Chindits, which has been fascinating! To answer some of your specific points:

Columns 1, 2, 3 and 4 were mainly composed of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles. Columns 5, 7 and 8 were the 13th King's; so your grandfather must have been in one of those columns I would say. The 13th King's were not a fighting unit and many of the older, less fit men were weeded out and replaced by other soldiers.

In relation to my time in Rangoon Jail; I was captured on the 26th April 1943 and transferred to the Maymyo Camp for several weeks. I was then transferred to Rangoon, where I was placed into solitary confinement for about five weeks before being moved to one of the open blocks. Your grandfather would therefore have died before I was released from solitary.

Colonel Henry Power of the Dogra Regiment did keep a record of all the burials at Rangoon, but I imagine that information would have gone to the War Graves Commission. In relation to my POW index card, perhaps mine is held by the Indian Army Office, due to my position with the 8th Gurkhas and is not at our National Archives. We never had a liberation debrief. We were the first POW's recovered from the Japanese and were under strict orders not to speak to anyone, especially the press. I believe this was because of the possible repercussions for those still held by the Japanese in Thailand and Singapore.

A letter dated 30/11/2008, in response to some POW documents I had been able to unearth.

Dear Steve,

Thanks for your phone call the other night. I enjoyed our chat, it took my mind off home just now where things have been difficult as my wife is now in hospital. I have to say, I am amazed at the amount of information you have dug out from different places and I wish you luck with in your future research. When we came back from the war, we were told that all documents and paperwork was strictly off-limits to us. Mind you, not many of us were looking to chase things up.

To answer some of your queries:

I did have contact with some of the officers from King's columns who were held in Rangoon; Philip Stibbe for example. However, you must appreciate that although we were in the same block at Rangoon, officers and men were not allowed to talk to one another, except of course on working parties.

I was interested in the list of prisoners which you sent me. Incredibly, this must cover the vast majority of the 200 or so Chindits in the jail at Rangoon. I enclose a copy of a list which was salvaged by one of the officers from 3 Block during 1943-45. Thank you for my POW index card; so it was listed under the M's; I was listed on the Pay Roll as Lt. McKay Gibson, so that is the reason for the difficulty in finding my card in the first instance. In relation to my capture, I was captured somewhere near Taugaung on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy and then sent to Wuntho on the railway.

I do not know why the American's inside Rangoon were treated more harshly, but the Japanese were extremely scared of air-raids once 1944 came. It might also be that the Americans could be a little too 'cocky' at times, which never paid with the Japs.

The man who brought me food when I was in solitary confinement was George Leggate of the Cameronians. I met him again about 40 years after the war and we saw quite a bit of each other until he sadly died about 4 years go.

Seen below are the lists that Alec sent me, showing the officers present in 3 Block at Rangoon Jail. Please click on either image to bring to forward on the page.

Letter dated 19/02/2009:

Dear Steve,

Thanks for your letter and all the enclosures, you seem to be doing very well with your research, good luck and carry on. I have replied to your various queries under their paragraph number:

The original burials at Rangoon were in very shallow graves with a simply wooden cross placed over the earth. When I visited Rangoon in 1985, I was given to understand that the War Cemetery was on the site where we originally buried our casualties.

I did not have first-hand knowledge of any medical experiments on our troops at Maymyo or Rangoon. I was one of the officers suspected of aiding the man (Pte. Hardy) of escaping from the jail. If I remember correctly I was in solitary confinement for about two weeks over this incident.

I did not know Lt. Rex Walker I'm afraid. I think you may well be correct about the deaths of prisoners before they got down to Rangoon. By the time I was moved into 6 Block several officers who had been there before me had been sent on to Singapore, I don't know why.

Letter dated 24/06/2011, in regards to the forthcoming TV documentary 'Narrow Escapes'.

Dear Steve,

Thanks for your letter. You have managed to dig out a fantastic amount of detail about Longcloth, I am always amazed at what you have found.

My Army number was EC 13988, my commission was incorrectly registered in 1942 and was not rectified until after I was released from Rangoon in 1945. Apart from my Identity Card, where the photograph is overprinted, the only decent photograph I have was taken just before I returned to India in October 1945. This is a photocopy of the original, which I cannot find at the moment, so I would appreciate the return of this in due course.

I am not quite sure how the new TV programme will turn out. The request for an interview was at very short notice. I believe that it is due out about September time, the team were here for about three hours.

Letter undated, although I believe it was from sometime in late 2011:

Dear Steve,

Congratulations on the website, it is a fitting tribute to your grandfather and all Longcloth men. It must have been very sad for you to learn all these details about your grandfather. You must however, be very proud of him. It seems quite clear to me that he and his comrades stayed behind because they felt that they were holding up the rest of the group. We all knew when we went in, that if we could not keep up with the rest of the column, we would have to be left behind.

I can appreciate your grandfather's thoughts at that time too. When I was captured by the Burmese, it was because I was starving and had dysentery. If I had not gone into that village to get food and drink, I would have died in the jungle. I at least was lucky to survive and live to a ripe old age.

I recently read 'Wingate's Lost Brigade' to which I see you contributed. I was fascinated by the book, as it showed me how little I knew about what went on that year, apart from with my own column. I have spoken to other survivors who have all said the same thing.

Letter dated 01/04/2013:

Dear Steve,

Thank you for your recent note. I only met Colonel Alexander once in January 1943, just before we moved down to Imphal. I only possessed a few words of Gurkhali and fully endorse your suggestion about the difficulties of communicating with my Gurkha comrades on Longcloth.

I would very much like to meet up for a chat, however, I have several hospital appointments coming up and I shall be glad to get some warmer weather. I will contact you a bit later and let you know. You would have to come to me as I am not very mobile nowadays.

Yours sincerely Alec Gibson.

Dear Steve,

Thanks for your letter and all the enclosures, you seem to be doing very well with your research, good luck and carry on. I have replied to your various queries under their paragraph number:

The original burials at Rangoon were in very shallow graves with a simply wooden cross placed over the earth. When I visited Rangoon in 1985, I was given to understand that the War Cemetery was on the site where we originally buried our casualties.

I did not have first-hand knowledge of any medical experiments on our troops at Maymyo or Rangoon. I was one of the officers suspected of aiding the man (Pte. Hardy) of escaping from the jail. If I remember correctly I was in solitary confinement for about two weeks over this incident.

I did not know Lt. Rex Walker I'm afraid. I think you may well be correct about the deaths of prisoners before they got down to Rangoon. By the time I was moved into 6 Block several officers who had been there before me had been sent on to Singapore, I don't know why.

Letter dated 24/06/2011, in regards to the forthcoming TV documentary 'Narrow Escapes'.

Dear Steve,

Thanks for your letter. You have managed to dig out a fantastic amount of detail about Longcloth, I am always amazed at what you have found.

My Army number was EC 13988, my commission was incorrectly registered in 1942 and was not rectified until after I was released from Rangoon in 1945. Apart from my Identity Card, where the photograph is overprinted, the only decent photograph I have was taken just before I returned to India in October 1945. This is a photocopy of the original, which I cannot find at the moment, so I would appreciate the return of this in due course.

I am not quite sure how the new TV programme will turn out. The request for an interview was at very short notice. I believe that it is due out about September time, the team were here for about three hours.

Letter undated, although I believe it was from sometime in late 2011:

Dear Steve,

Congratulations on the website, it is a fitting tribute to your grandfather and all Longcloth men. It must have been very sad for you to learn all these details about your grandfather. You must however, be very proud of him. It seems quite clear to me that he and his comrades stayed behind because they felt that they were holding up the rest of the group. We all knew when we went in, that if we could not keep up with the rest of the column, we would have to be left behind.

I can appreciate your grandfather's thoughts at that time too. When I was captured by the Burmese, it was because I was starving and had dysentery. If I had not gone into that village to get food and drink, I would have died in the jungle. I at least was lucky to survive and live to a ripe old age.

I recently read 'Wingate's Lost Brigade' to which I see you contributed. I was fascinated by the book, as it showed me how little I knew about what went on that year, apart from with my own column. I have spoken to other survivors who have all said the same thing.

Letter dated 01/04/2013:

Dear Steve,

Thank you for your recent note. I only met Colonel Alexander once in January 1943, just before we moved down to Imphal. I only possessed a few words of Gurkhali and fully endorse your suggestion about the difficulties of communicating with my Gurkha comrades on Longcloth.

I would very much like to meet up for a chat, however, I have several hospital appointments coming up and I shall be glad to get some warmer weather. I will contact you a bit later and let you know. You would have to come to me as I am not very mobile nowadays.

Yours sincerely Alec Gibson.

Over the past few years, Alec helped out with many Chindit related projects. These included being interviewed for Tony Redding's excellently researched book 'War in the Wilderness', from which some of the information used above was taken and the television documentary series, 'Narrow Escapees of World War 2.'

In late 2014, Alec moved away from his home in Surbiton, where he had lived for many years and moved to the Royal Star & Garter Home at Solihull in Birmingham. Even here he contributed to an article for 'Soldier' magazine in August 2015 and produced another story for the VJ Day Celebrations run by the Royal Star & Garter organisation that same month.

The Royal Star & Garter Homes have also placed an obituary for Alec Gibson on their 'Memorial Wall.' As a way of concluding this tribute, I will reproduce the sentiment I placed upon the Royal Star & Garter Memorial Wall, as my appreciation for all the help and encouragement Alec gave me during my initial research into the men of the first Wingate expedition.

In late 2014, Alec moved away from his home in Surbiton, where he had lived for many years and moved to the Royal Star & Garter Home at Solihull in Birmingham. Even here he contributed to an article for 'Soldier' magazine in August 2015 and produced another story for the VJ Day Celebrations run by the Royal Star & Garter organisation that same month.

The Royal Star & Garter Homes have also placed an obituary for Alec Gibson on their 'Memorial Wall.' As a way of concluding this tribute, I will reproduce the sentiment I placed upon the Royal Star & Garter Memorial Wall, as my appreciation for all the help and encouragement Alec gave me during my initial research into the men of the first Wingate expedition.

"God Bless Alec. You gave me such an important insight in regards to Operation Longcloth. You also shared with me some of your darker moments inside Rangoon Jail, where my grandfather sadly perished in June 1943. I am forever grateful to you for your generosity and for taking the time to speak and write to me."

Copyright © Steve Fogden, June 2016.