Family Pages (2)

Georgina Livingstone, wife of RSM William Livingstone MC

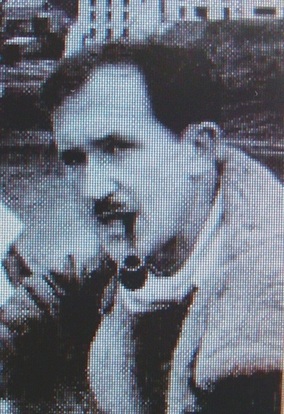

Bill and Georgina in their younger days.

Georgina Livingstone replied to my very first article in the Burma Star magazine of Autumn 2007. Since then we have kept in contact by letter and the occasional telephone call, eventually meeting one another at the Chindit Old Comrades Dinner in June 2009. She has been of great help to me in my quest for knowledge regarding the Chindits of 1943 and a wonderful supporter of all that I have tried to do.

How fortunate I have been to meet the wife of the 13th King's Regimental Sergeant Major, William Livingstone and to learn of his life and times in Burma. I asked Georgina if she would like to contribute to this site, with her own memories and thoughts about William and his time in the Army and this is what she wrote:

Steve, I have done as much as I can, but I’m afraid that most of the personal anecdotes about Bill have now slipped my mind. Its 34 years since he died, and although so many memories constantly come to mind, there were never any significant tales that I remember. He never, ever spoke of that last long march out of Burma, not in any detail anyway. I’ve learned most of what I know from books and none of those really speak of his actual group.

Bill enlisted in to the Royal Ulster Rifles on the 24th March 1930. His early days and years took him to places such as Palestine, Egypt and Hong Kong, then finally to India from where he was repatriated in early 1939. We married in April 1941.

He was, in spite of his rank and Army career, a quiet, but strong minded man, a very hard working family man too. When he left the Army, sadly he never tried to contact even his closest friends. Times were hard then, and people just did not get around as much or meet up with old friends. Also he never wanted to write letters and so did not contact anyone for addresses, which he could have done. He did join the Burma Star Association for a short while, but shift work meant he could not attend the meetings very often, so he gave that up. If he talked to me at all about the Army and his travels, it was always to say how much he loved it and the good opportunities it gave him. However, I think Burma plus the long separation was enough, as he now had a wife and young son to look after, he was glad to settle down and enjoy a peaceful life.

He did so love the Army and was proud of what his men and all the other Chindits achieved. He was saddened by the losses of so many good men, but was also a true believer in all Brigadier Wingate wanted to do. I have tried to list all Bill’s postings, it is a very rough guide, sorry if it is of no use.

Enlisted into the 2nd battalion Royal Ulster Rifles at the Omagh Barracks in 1930.

Then on to Victoria Barracks Belfast, for training. Posted to Palestine, which Bill enjoyed very much, then on to Alexandria in Egypt.

Hong Kong, which Bill told me was a very good posting, except that often you had to go up to Shanghai. The regiment was very happy there (Hong Kong), but did lose some men on operations. Next was a short stay in India, the battalion were probably awaiting their troopship home and sailed from Bombay back to the UK.

In 1940 the 13th Kings were formed in Wales, but soon went to the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow. The battalion were asked to perform garrison and coastal duties over the next period in place like Felixstowe, Ipswich (where they were stationed at the airport), Colchester (Cherry tree and McMahon Barracks) and Burford.

In late 1941 the men went to Blackburn in Lancashire, some of the men were very near home and took the opportunity to visit their families. It was at Blackburn that the battalion prepared for overseas duty and sailed from Liverpool on 7th December 1941 bound for India.

They were stationed at Secunderabad at the Gough Barracks and performed garrison duties until Wingate came along. Bill was made up to Regimental Quarter Master Sergeant at Secunderabad.

During the second half of 1942 the battalion saw many changes of personnel, as men unfit for jungle training were transferred out. Bill was then made up to RSM.

In February 1943 they went into Burma and behind enemy lines. He was in column number 8 with Scotty (Major Walter Scott). On dispersal he led a small group of 20 men out of the jungle and was awarded the Military Cross and commissioned to Lieutenant Quarter Master. On his return to India Bill was hospitalized, then after recuperation, sent on extended leave.

After operation Longcloth, the battalion was stationed in Karachi until the end of the war. In July 1945 Bill was offered a promotion to the rank of Captain if he stayed on in the Army. But he declined the offer and arrived home via Southampton on VJ Day.

How fortunate I have been to meet the wife of the 13th King's Regimental Sergeant Major, William Livingstone and to learn of his life and times in Burma. I asked Georgina if she would like to contribute to this site, with her own memories and thoughts about William and his time in the Army and this is what she wrote:

Steve, I have done as much as I can, but I’m afraid that most of the personal anecdotes about Bill have now slipped my mind. Its 34 years since he died, and although so many memories constantly come to mind, there were never any significant tales that I remember. He never, ever spoke of that last long march out of Burma, not in any detail anyway. I’ve learned most of what I know from books and none of those really speak of his actual group.

Bill enlisted in to the Royal Ulster Rifles on the 24th March 1930. His early days and years took him to places such as Palestine, Egypt and Hong Kong, then finally to India from where he was repatriated in early 1939. We married in April 1941.

He was, in spite of his rank and Army career, a quiet, but strong minded man, a very hard working family man too. When he left the Army, sadly he never tried to contact even his closest friends. Times were hard then, and people just did not get around as much or meet up with old friends. Also he never wanted to write letters and so did not contact anyone for addresses, which he could have done. He did join the Burma Star Association for a short while, but shift work meant he could not attend the meetings very often, so he gave that up. If he talked to me at all about the Army and his travels, it was always to say how much he loved it and the good opportunities it gave him. However, I think Burma plus the long separation was enough, as he now had a wife and young son to look after, he was glad to settle down and enjoy a peaceful life.

He did so love the Army and was proud of what his men and all the other Chindits achieved. He was saddened by the losses of so many good men, but was also a true believer in all Brigadier Wingate wanted to do. I have tried to list all Bill’s postings, it is a very rough guide, sorry if it is of no use.

Enlisted into the 2nd battalion Royal Ulster Rifles at the Omagh Barracks in 1930.

Then on to Victoria Barracks Belfast, for training. Posted to Palestine, which Bill enjoyed very much, then on to Alexandria in Egypt.

Hong Kong, which Bill told me was a very good posting, except that often you had to go up to Shanghai. The regiment was very happy there (Hong Kong), but did lose some men on operations. Next was a short stay in India, the battalion were probably awaiting their troopship home and sailed from Bombay back to the UK.

In 1940 the 13th Kings were formed in Wales, but soon went to the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow. The battalion were asked to perform garrison and coastal duties over the next period in place like Felixstowe, Ipswich (where they were stationed at the airport), Colchester (Cherry tree and McMahon Barracks) and Burford.

In late 1941 the men went to Blackburn in Lancashire, some of the men were very near home and took the opportunity to visit their families. It was at Blackburn that the battalion prepared for overseas duty and sailed from Liverpool on 7th December 1941 bound for India.

They were stationed at Secunderabad at the Gough Barracks and performed garrison duties until Wingate came along. Bill was made up to Regimental Quarter Master Sergeant at Secunderabad.

During the second half of 1942 the battalion saw many changes of personnel, as men unfit for jungle training were transferred out. Bill was then made up to RSM.

In February 1943 they went into Burma and behind enemy lines. He was in column number 8 with Scotty (Major Walter Scott). On dispersal he led a small group of 20 men out of the jungle and was awarded the Military Cross and commissioned to Lieutenant Quarter Master. On his return to India Bill was hospitalized, then after recuperation, sent on extended leave.

After operation Longcloth, the battalion was stationed in Karachi until the end of the war. In July 1945 Bill was offered a promotion to the rank of Captain if he stayed on in the Army. But he declined the offer and arrived home via Southampton on VJ Day.

William Livingstone was one of the unsung heroes of 1943 and a vital part of the leadership of column 8 on operation Longcloth. He led one of the final dispersal groups of the column home to India, after the disaster at Kaukkwe Chaung on April 30th that year. The Japanese had caught the tail of the column crossing the fast flowing river and the RSM and other experienced NCO’s had all formed the rear guard to defend the unit’s escape. Georgina told me once in one of her letters that Bill and some of the other NCO’s had spent most of that day trying to ferry all the non-swimmers over the river whilst under fire from the Japanese.

In the book ‘Wingate’s Phantom Army’, W.G. Burchett describes the scene: “The battle of Kaukkwe Chaung was the end of Scott’s column as one unit. Their rendezvous existed on the map only, and none of the parties ever found it. Delaney took one party out to India, the regimental sergeant major (William) another, and Scott a third. Most of the men had lost their packs at the river. By the time they had divided up what was left, instead of 14 days good rations, they had only 2 days per man, and no possibility of further droppings."

From the War Diary of the 13th King’s dated 27th May 1943: “ Reports received that the dispersal party of Number 2 Group HQ under the command of Lieutenant J. Pickering had arrived at Layshi. The party contained Lieutenants Bennett, Gillow and Pearce, with 28 British Other Ranks, 21 Gurkhas and others. It is also known that Lieutenant Hamilton-Bryan, RSM Livingstone and a CSM from column 8 (Delaney) were following on independently."

On 12th November 1943 William received his commission to the rank of Lieutenant QM, this promotion allowed him to be awarded the Military Cross for his actions in Burma that year. He received his medal from Archibald Wavell no less. (Pictured left, image courtesy of Georgia Livingstone).

In the book ‘Wingate’s Phantom Army’, W.G. Burchett describes the scene: “The battle of Kaukkwe Chaung was the end of Scott’s column as one unit. Their rendezvous existed on the map only, and none of the parties ever found it. Delaney took one party out to India, the regimental sergeant major (William) another, and Scott a third. Most of the men had lost their packs at the river. By the time they had divided up what was left, instead of 14 days good rations, they had only 2 days per man, and no possibility of further droppings."

From the War Diary of the 13th King’s dated 27th May 1943: “ Reports received that the dispersal party of Number 2 Group HQ under the command of Lieutenant J. Pickering had arrived at Layshi. The party contained Lieutenants Bennett, Gillow and Pearce, with 28 British Other Ranks, 21 Gurkhas and others. It is also known that Lieutenant Hamilton-Bryan, RSM Livingstone and a CSM from column 8 (Delaney) were following on independently."

On 12th November 1943 William received his commission to the rank of Lieutenant QM, this promotion allowed him to be awarded the Military Cross for his actions in Burma that year. He received his medal from Archibald Wavell no less. (Pictured left, image courtesy of Georgia Livingstone).

Above is a photograph of William (second from left) proudly displaying his well deserved Military Cross. The other gallantry recipients were, from left to right: Major JS Pickering, William Livingstone, CSM Richard Cheevers, Sergeant Jackie Cairns and Sergeant John Thornborrow.

Georgina never saw the citation for William’s Military Cross until some years after he had sadly passed away. Here is a transcription of the citation as put forward by Major WS Scott:

On 30th April, 1943, a dispersal group under the command of Major W.P. Scott, which had spent the day crossing the KAUKWE CHAUNG on rafts, was forming up to continue its march when it was suddenly attacked by a strong Japanese patrol. Regimental Sergeant Major Livingstone instantly organised the troops in his immediate neighbourhood in a most gallant and spirited defence, engaging the enemy wherever they showed themselves, regardless of their superior strength and of their great superiority in automatic weapons. By so doing, and by opening a heavy fire on the enemy whenever and wherever they showed themselves, he succeeded in holding a ring where by he helped to prevent a large number of non-swimmers from being thrust into the river by the Japanese attack. But for his resolute action the great majority of these men would have inevitably been either killed or drowned.

When the enemy transferred their attention to another part of the area, R.S.M. LIVINGSTONE was with difficulty dissuaded from following them through the thick jungle in an effort to reach them with the bayonet. Finally, becoming separated from the main body, he collected, organised and led a large party of troops through the Japanese lines to a safe area where he joined an officer and with him marched his men 150 miles to the Chindwin River.

Throughout the campaign his courage, bearing and endurance have been of a high order and an inspiration to British, Burmese and Gurkha ranks alike.

Copyright © Georgina Livingstone and Steve Fogden 2011.

Georgina never saw the citation for William’s Military Cross until some years after he had sadly passed away. Here is a transcription of the citation as put forward by Major WS Scott:

On 30th April, 1943, a dispersal group under the command of Major W.P. Scott, which had spent the day crossing the KAUKWE CHAUNG on rafts, was forming up to continue its march when it was suddenly attacked by a strong Japanese patrol. Regimental Sergeant Major Livingstone instantly organised the troops in his immediate neighbourhood in a most gallant and spirited defence, engaging the enemy wherever they showed themselves, regardless of their superior strength and of their great superiority in automatic weapons. By so doing, and by opening a heavy fire on the enemy whenever and wherever they showed themselves, he succeeded in holding a ring where by he helped to prevent a large number of non-swimmers from being thrust into the river by the Japanese attack. But for his resolute action the great majority of these men would have inevitably been either killed or drowned.

When the enemy transferred their attention to another part of the area, R.S.M. LIVINGSTONE was with difficulty dissuaded from following them through the thick jungle in an effort to reach them with the bayonet. Finally, becoming separated from the main body, he collected, organised and led a large party of troops through the Japanese lines to a safe area where he joined an officer and with him marched his men 150 miles to the Chindwin River.

Throughout the campaign his courage, bearing and endurance have been of a high order and an inspiration to British, Burmese and Gurkha ranks alike.

Copyright © Georgina Livingstone and Steve Fogden 2011.

Val Gornell, daughter of James Ambrose

I finally made contact with Valerie in July 2009, after seeing her request for information about her father's time in WW2 on the Burma Star website. Both my Grandfather and Val's father James had been mentioned as missing in action on the same day, the 18th April 1943.

I knew that they were both in Bernard Fergusson's column 5, but at the time Valerie and I first spoke, neither of us realised how close the two men had been during those last few fateful weeks of freedom on the Burma/China borders.

Here are her thoughts about her father James Ambrose.

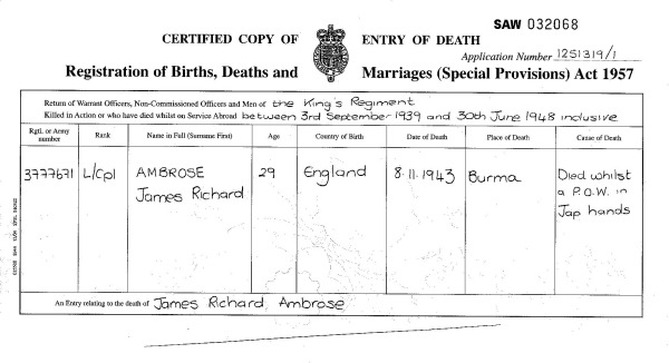

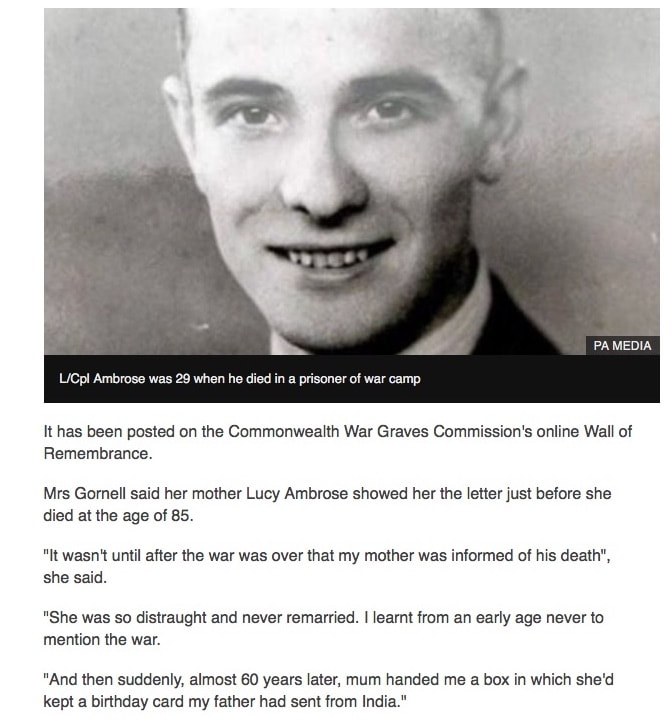

3777671 L/Cpl. James Richard Ambrose 13th Bn Kings (Liverpool) Regt.

Born Liverpool 28th March 1914 – Died Burma 8th November 1943

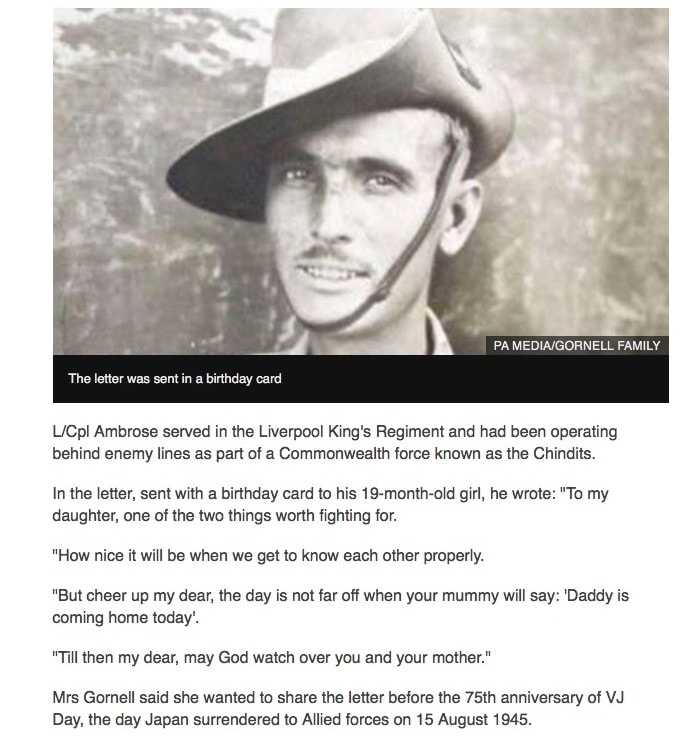

I have no memory of my father as I was only 8 months old when he sailed from Liverpool on December 8th 1941, for India on the SS Oronsay. He died in Rangoon Jail on 8th November 1943. My mother was informed that he was a prisoner of the Japanese in Burma in 1943 but his death was not confirmed until 4th May 1945. She was so deeply upset that she could not talk about him and I learned at a very early age not to mention Burma, Chindits or Wingate. She never remarried and I am their only child.

His photo stood at the side of her bed – an unsmiling man in uniform wearing, I thought, a funny hat. I could not understand why people became upset whilst saying how very like him I looked. I knew he had been a keen amateur racing cyclist with the Phoenix Cycling Club in Liverpool, that he had worked for Moores as a driver but it was not until 1998, and nearing her death at the age of 85 that my Mum began to talk a bit more openly about him. One of things she gave me was a letter he had written to me just before he sailed from Liverpool, where he talks about taking me for walks when he returns, and also the card he sent from India for my 1st birthday. She had kept these for nearly 60 years and I had never seen them before. Shortly after this I began tracing my family history and contacted as many member's of my father’s family as I could asking them to tell me about him. They came up with so many stories and so much information that I began to feel that I knew him a little better.

Eventually my husband and I decided we had to go to Burma, something my Mum would never consider doing when it was offered by the British Legion. We decided on a tour with a holiday company which visited Mandalay, Bagan, and included a day sailing on the Irrawaddy ending with two days in Rangoon. I wanted to see more of the country where he had fought and died. There were so many conflicting emotions during the time we were there but standing by his grave in Rangoon Cemetery, surrounded by the graves of many other Chindits and Kingsmen, I knew my father was resting in peace.

Since Steve contacted me I have found out so much more from him about my father’s time in Burma, with Steve’s grandfather, their eventual capture and death in Rangoon Jail. I am proud of my Chindit father and grateful to have had the opportunity to commemorate his life.

Val Gornell

11th August 2011.

I knew that they were both in Bernard Fergusson's column 5, but at the time Valerie and I first spoke, neither of us realised how close the two men had been during those last few fateful weeks of freedom on the Burma/China borders.

Here are her thoughts about her father James Ambrose.

3777671 L/Cpl. James Richard Ambrose 13th Bn Kings (Liverpool) Regt.

Born Liverpool 28th March 1914 – Died Burma 8th November 1943

I have no memory of my father as I was only 8 months old when he sailed from Liverpool on December 8th 1941, for India on the SS Oronsay. He died in Rangoon Jail on 8th November 1943. My mother was informed that he was a prisoner of the Japanese in Burma in 1943 but his death was not confirmed until 4th May 1945. She was so deeply upset that she could not talk about him and I learned at a very early age not to mention Burma, Chindits or Wingate. She never remarried and I am their only child.

His photo stood at the side of her bed – an unsmiling man in uniform wearing, I thought, a funny hat. I could not understand why people became upset whilst saying how very like him I looked. I knew he had been a keen amateur racing cyclist with the Phoenix Cycling Club in Liverpool, that he had worked for Moores as a driver but it was not until 1998, and nearing her death at the age of 85 that my Mum began to talk a bit more openly about him. One of things she gave me was a letter he had written to me just before he sailed from Liverpool, where he talks about taking me for walks when he returns, and also the card he sent from India for my 1st birthday. She had kept these for nearly 60 years and I had never seen them before. Shortly after this I began tracing my family history and contacted as many member's of my father’s family as I could asking them to tell me about him. They came up with so many stories and so much information that I began to feel that I knew him a little better.

Eventually my husband and I decided we had to go to Burma, something my Mum would never consider doing when it was offered by the British Legion. We decided on a tour with a holiday company which visited Mandalay, Bagan, and included a day sailing on the Irrawaddy ending with two days in Rangoon. I wanted to see more of the country where he had fought and died. There were so many conflicting emotions during the time we were there but standing by his grave in Rangoon Cemetery, surrounded by the graves of many other Chindits and Kingsmen, I knew my father was resting in peace.

Since Steve contacted me I have found out so much more from him about my father’s time in Burma, with Steve’s grandfather, their eventual capture and death in Rangoon Jail. I am proud of my Chindit father and grateful to have had the opportunity to commemorate his life.

Val Gornell

11th August 2011.

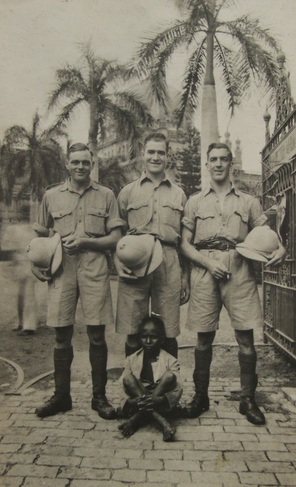

Here is James again, pictured right, with a group of other NCO's and an Indian bearer at Saugor. James had travelled to India with the original battalion and settled in to the Gough Barracks at Secunderabad. He would have performed garrison duties in the town and local area for the first few months of 1942.

Eventually Wingate took control of the 13th Kings and their Chindit training began in earnest in July that year. James was to be one of the 400 or so Kingsmen that survived the whole 6 months of Chindit training and found himself crossing the Chindwin River and marching into Burma in February 1943.

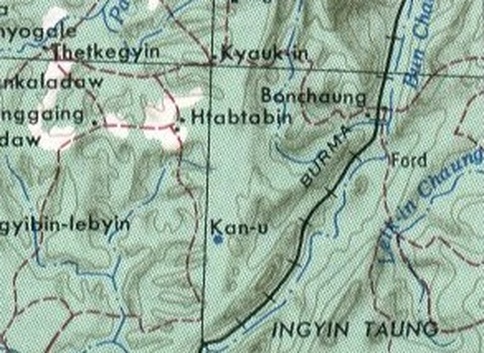

As part of column 5 he would have played a part in demolishing the bridges and railway lines at Bonchaung and the engagement at the village of Hintha. This last action on the 29th March is where the men of column 5 became separated as one unit. Around 100 men, with James amongst them had missed the rendezvous with Fergusson a few miles northeast of Hintha and chose to march in the direction of the Shweli River.

Fortune looked down on them at this point, and by luck they bumped into column 7 at the river and Major Gilkes took them under his command. The men of both columns became inter mixed and were organised into dispersal parties of 20-30 men and an officer was assigned to lead them. James and my grandfather found themselves led by the Burma Rifle officer, Captain Jon Musgrave-Wood.

Eventually Wingate took control of the 13th Kings and their Chindit training began in earnest in July that year. James was to be one of the 400 or so Kingsmen that survived the whole 6 months of Chindit training and found himself crossing the Chindwin River and marching into Burma in February 1943.

As part of column 5 he would have played a part in demolishing the bridges and railway lines at Bonchaung and the engagement at the village of Hintha. This last action on the 29th March is where the men of column 5 became separated as one unit. Around 100 men, with James amongst them had missed the rendezvous with Fergusson a few miles northeast of Hintha and chose to march in the direction of the Shweli River.

Fortune looked down on them at this point, and by luck they bumped into column 7 at the river and Major Gilkes took them under his command. The men of both columns became inter mixed and were organised into dispersal parties of 20-30 men and an officer was assigned to lead them. James and my grandfather found themselves led by the Burma Rifle officer, Captain Jon Musgrave-Wood.

Initially all the dispersal groups split up, in the hope of meeting up once more in a few days for a large supply drop. The agreed rendezvous was set, but very few groups made that appointment. With the dates now to hand it would seem that James passed through many friendly Kachin villages on the journey out toward the Yunnan border.

Then for some unknown reason a group of 6 men decided to leave the main dispersal group of Captain Musgrave-Wood (pictured left, after the war). I spoke of this with Longcloth survivor Alec Gibson, he said it sounded to him like a decision was made by the men to stop holding up the fitter members of their party and to drop out of the march. He also said that he had done something similar in 1943, when he also realised that he could no longer continue.

Here is a transcription of a witness report by one of the other members of Musgrave-Wood's dispersal party:

3773321 Pte. F.J. Rowlands, 13th battalion Kings Regiment states:

I was with number 5 column, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade during operations in Burma in 1943. On my way out of Burma I was with a dispersal group commanded by Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood. On about the 12th of May 1943, Pte. Lowe left the group, accompanied by Lance Corporal William Jordan, Lance Corporal James Ambrose, Pte. Edgar Burger, Pte. Leon Franks and Pte. A. Howney.

There was nothing wrong with Pte. Lowe except that he was of the opinion that he would not be able to make the journey out. They left us at the village of Lansa. That is the last I saw of the above mentioned men. They all had rifles and some ammunition, but no food.

So what was the actual situation concerning these men? It is almost impossible to say, but the presence of Leon Frank in the group enables us to push this story on a little further.

Then for some unknown reason a group of 6 men decided to leave the main dispersal group of Captain Musgrave-Wood (pictured left, after the war). I spoke of this with Longcloth survivor Alec Gibson, he said it sounded to him like a decision was made by the men to stop holding up the fitter members of their party and to drop out of the march. He also said that he had done something similar in 1943, when he also realised that he could no longer continue.

Here is a transcription of a witness report by one of the other members of Musgrave-Wood's dispersal party:

3773321 Pte. F.J. Rowlands, 13th battalion Kings Regiment states:

I was with number 5 column, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade during operations in Burma in 1943. On my way out of Burma I was with a dispersal group commanded by Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood. On about the 12th of May 1943, Pte. Lowe left the group, accompanied by Lance Corporal William Jordan, Lance Corporal James Ambrose, Pte. Edgar Burger, Pte. Leon Franks and Pte. A. Howney.

There was nothing wrong with Pte. Lowe except that he was of the opinion that he would not be able to make the journey out. They left us at the village of Lansa. That is the last I saw of the above mentioned men. They all had rifles and some ammunition, but no food.

So what was the actual situation concerning these men? It is almost impossible to say, but the presence of Leon Frank in the group enables us to push this story on a little further.

Pictured above are, on the left Leon Frank (courtesy of the AJEX Museum) and on the right Arthur Howney, both photos were taken in India, I know that Leon's was taken at Saugor in August 1942. Leon would be the only survivor from this small group of 6 men. The date mentioned by Pte. Rowlands in his statement (12th May) means that the group were all but in China by this time, however, their physical condition meant that they were still far from safety.

Here is Leon Frank's account of those last few days of freedom, taken from the book 'March or Die', and with the kind permission of the author Phil Chinnery:

I was in a group of thirty men under a Lieutenant from the Sherwood Foresters (Musgrave-Wood) and we decided to make our way northwards to Fort Hertz, which was still in British hands. The idea was that we would take some guides from a village, who could take us on to the next village, and so on. We did this successfully for a while, then we had these two guides that were leading us up a hill, towards a cross-shaped junction of tracks. suddenly one dived left and the other right and disappeared into the jungle. In front of us across the track was a Japanese patrol. Well, we just melted into the jungle either side, but the Japs had spotted us.

We hoped that if were quiet enough they would just go away, but one of our chaps (Dennett) looked up and for no apparent reason shouted 'Japs' and this gave our position away. They started to open fire on us, so we turned and rolled and scrambled down the hill. We did everything we could to put them off our tracks and eventually eluded them. We realised that our party was too large and an obvious target, so our Lieutenant told us it was every man for himself. Myself and five others, including Lance Corporal Jordan, decided to go east and try and get into China.

We became like bandits; we would go into villages and demand rice and food at gunpoint. We eventually came to a hillside with a hut on the side of it and a stream below and settled down to rest. Someone should have been on guard but we were very exhausted. Next thing we knew the door burst open and in came a Jap soldier with a fixed bayonet and stabbed Jordan in the hand. He was about to have another go when an officer called him off. We walked outside to find a half moon circle of Japanese soldiers with a machine-gun in the centre, pointed at us. I remember turning round and saying, "the bastards are going to shoot us in cold blood!"

Fortunately we had been captured by the Imperial Guard, who were professional soldiers. They tied our hands and led us to their camp. We were fed and given various jobs to do around the camp. I was made batman to one of the Japanese officers and had to sleep with five other Japanese batmen. One of the soldiers could speak English. He had been a barber in Tokyo and asked me to go to his hut for supper one night. He gave me some rice and kidneys to eat and invited me to go to Tokyo after the war and meet his family.

After about ten days we were put on a truck and sent to Maymyo. On the way we stopped at another jungle camp (probably Bhamo) and our escort left us in the hands of the camp's personnel. We were taken into a hut and made to kneel in the execution position with our hands tied behind our back. A big Japanese officer came in whirling his sword and we thought our time had come. However, it was just a sick joke.

When got to Maymyo we were beaten up by the Korean guards, who were just as bad as, if not worse than the Japanese. Eventually we were sent to Rangoon by train, crammed into cattle trucks for the three day trip. I remember when we stopped at Mandalay the door opened and we saw one of the big six foot Imperial guardsmen who had captured us. He went away and came back with a bunch of bananas which he gave to us. Our next stop was block number 6, Rangoon Jail. I was the only one of the six to survive.

Leon Frank's recorded interview which he gave to the Imperial War Museum in 1995 can be found by clicking the following link:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80015277 (This link came back online in January 2013).

Here is Leon Frank's account of those last few days of freedom, taken from the book 'March or Die', and with the kind permission of the author Phil Chinnery:

I was in a group of thirty men under a Lieutenant from the Sherwood Foresters (Musgrave-Wood) and we decided to make our way northwards to Fort Hertz, which was still in British hands. The idea was that we would take some guides from a village, who could take us on to the next village, and so on. We did this successfully for a while, then we had these two guides that were leading us up a hill, towards a cross-shaped junction of tracks. suddenly one dived left and the other right and disappeared into the jungle. In front of us across the track was a Japanese patrol. Well, we just melted into the jungle either side, but the Japs had spotted us.

We hoped that if were quiet enough they would just go away, but one of our chaps (Dennett) looked up and for no apparent reason shouted 'Japs' and this gave our position away. They started to open fire on us, so we turned and rolled and scrambled down the hill. We did everything we could to put them off our tracks and eventually eluded them. We realised that our party was too large and an obvious target, so our Lieutenant told us it was every man for himself. Myself and five others, including Lance Corporal Jordan, decided to go east and try and get into China.

We became like bandits; we would go into villages and demand rice and food at gunpoint. We eventually came to a hillside with a hut on the side of it and a stream below and settled down to rest. Someone should have been on guard but we were very exhausted. Next thing we knew the door burst open and in came a Jap soldier with a fixed bayonet and stabbed Jordan in the hand. He was about to have another go when an officer called him off. We walked outside to find a half moon circle of Japanese soldiers with a machine-gun in the centre, pointed at us. I remember turning round and saying, "the bastards are going to shoot us in cold blood!"

Fortunately we had been captured by the Imperial Guard, who were professional soldiers. They tied our hands and led us to their camp. We were fed and given various jobs to do around the camp. I was made batman to one of the Japanese officers and had to sleep with five other Japanese batmen. One of the soldiers could speak English. He had been a barber in Tokyo and asked me to go to his hut for supper one night. He gave me some rice and kidneys to eat and invited me to go to Tokyo after the war and meet his family.

After about ten days we were put on a truck and sent to Maymyo. On the way we stopped at another jungle camp (probably Bhamo) and our escort left us in the hands of the camp's personnel. We were taken into a hut and made to kneel in the execution position with our hands tied behind our back. A big Japanese officer came in whirling his sword and we thought our time had come. However, it was just a sick joke.

When got to Maymyo we were beaten up by the Korean guards, who were just as bad as, if not worse than the Japanese. Eventually we were sent to Rangoon by train, crammed into cattle trucks for the three day trip. I remember when we stopped at Mandalay the door opened and we saw one of the big six foot Imperial guardsmen who had captured us. He went away and came back with a bunch of bananas which he gave to us. Our next stop was block number 6, Rangoon Jail. I was the only one of the six to survive.

Leon Frank's recorded interview which he gave to the Imperial War Museum in 1995 can be found by clicking the following link:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80015277 (This link came back online in January 2013).

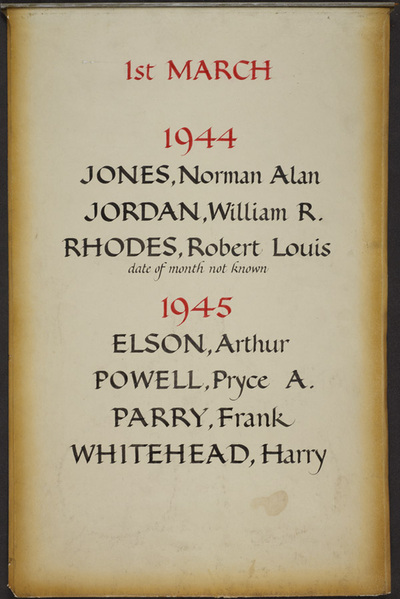

All six men entered Rangoon Jail sometime in late May 1943, all except Leon Frank perished there in Block 6 of that infamous establishment. According to the lists from Rangoon Jail, held at the Imperial War Museum:

4202396 Pte. Frederick Lowe died on 01/06/1943. (I now know that Fred died almost immediately on arrival in Rangoon, and was buried at St. Mary's Catholic Church cemetery). Recently (19/06/2014) Fred's Japanese index card was found at the National Archives, his name had been mis-spelled as Rowe. From translation of the details on the reverse of the card, it is now understood that he died in Rangoon on the 22nd May 1943 and had suffered a heart attack that day.

5629998 Pte. Arthur Howney died on 19/06/1943

5124637 Pte. Edgar Burger died on 28/09/1943

3777671 L/Cpl. James R. Ambrose died on 08/11/1943

3657118 L/Cpl. William R. Jordan died on 01/03/1944

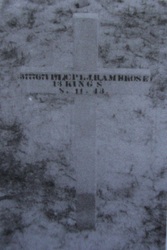

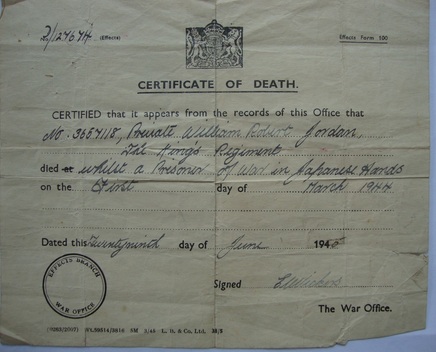

James Ambrose was recorded as POW number 426 and was originally buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery in Rangoon, with the grave reference 117. Sadly, no Japanese index card seems to exist for James, which could of given up more details of his time as a POW. Below are two images, one is a photo of James's memorial grave plaque found in Rangoon War Cemetery, the other, his Army Overseas Death Certificate, showing the scant details recorded and offered to his family as an explanation for his death in WW2.

4202396 Pte. Frederick Lowe died on 01/06/1943. (I now know that Fred died almost immediately on arrival in Rangoon, and was buried at St. Mary's Catholic Church cemetery). Recently (19/06/2014) Fred's Japanese index card was found at the National Archives, his name had been mis-spelled as Rowe. From translation of the details on the reverse of the card, it is now understood that he died in Rangoon on the 22nd May 1943 and had suffered a heart attack that day.

5629998 Pte. Arthur Howney died on 19/06/1943

5124637 Pte. Edgar Burger died on 28/09/1943

3777671 L/Cpl. James R. Ambrose died on 08/11/1943

3657118 L/Cpl. William R. Jordan died on 01/03/1944

James Ambrose was recorded as POW number 426 and was originally buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery in Rangoon, with the grave reference 117. Sadly, no Japanese index card seems to exist for James, which could of given up more details of his time as a POW. Below are two images, one is a photo of James's memorial grave plaque found in Rangoon War Cemetery, the other, his Army Overseas Death Certificate, showing the scant details recorded and offered to his family as an explanation for his death in WW2.

My great thanks go to Val Gornell and her family for all the help and support they have given me and for the photos of James and his time in India. It is incredible how her story and her life has mirrored that of my Mum, especially in regard to growing up without their father.

Update 20/02/2012.

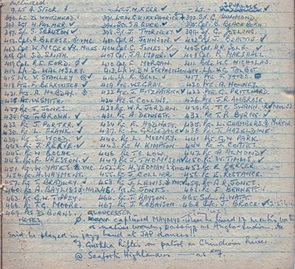

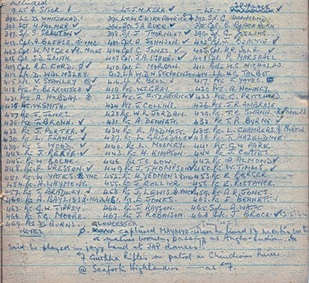

The document pictured to the left came into my possession in February 2012 (please click on the image to enlarge). It shows a list of Chindit POW's complete with their prisoner number alongside their name. It was a listing created by Captain H. Machin, who was attempting to collate the men from 77th Indian Infantry Brigade found to be present in Rangoon Jail.

Machin was part of Wingate's Head Quarters on operation Longcloth and was present as an interrupter due to his fluency in Japanese. He was captured by the Japanese during the dispersal and was eventually taken to Singapore, where he was interrogated by the Kempai-Tai (Japanese secret police). He was one of a small group of Chindits to be removed from Rangoon Jail in late May 1943 and was eventually liberated from Changi Prison Camp in mid-1945.

The list is of great importance to me, as it is the first time that either James or my Grandfather are mentioned in any personal diary, memoir or book. It also clearly shows the soldier's POW number. One other point of interest is the presence of the the officers names above the three columns. It makes me wonder if Lieutenants Stock, Kerr and Spurlock were not in some way responsible for the men written beneath their names. The list runs in sequence of POW number across the page rather than down, separating the men in numerical rather than alphabetical order. The reason for this is unknown at present and could just be an idiosyncrasy of the time. You will also notice that the each column runs in rank order as the list progresses downward.

As for the six men of James's dispersal group, they are split across all three columns with Fred Lowe missing entirely from the list. The only non-Chindit to be found in the group is Cpl. Ford (Gloucesters) who seems to have been captured in the Maymyo area in 1943, having lived for over a year posing as a Burmese native. Patrick Flannigan Ford survived his time in Rangoon Jail, whether he returned to Maymyo or his home town of Dublin after the war is unknown.

Update 13/02/2013.

Seen below is a new set of photographs featuring James Ambrose and some of his comrades from Longcloth, mostly from training in Saugor in 1942. These came from a collection kept by Val Gornell's mother along with a letter. In this letter, two other soldiers are mentioned, George Wareing and Les Shaw, both from the Wirrall area of Liverpool. Neither man features in any paperwork in relation to the first Wingate expedition or are listed on the CWGC website, so it must be presumed that they both survived the war and returned home. Many thanks again to Val Gornell for kindly giving me permission to show these photographs of her father's WW2 service.

The document pictured to the left came into my possession in February 2012 (please click on the image to enlarge). It shows a list of Chindit POW's complete with their prisoner number alongside their name. It was a listing created by Captain H. Machin, who was attempting to collate the men from 77th Indian Infantry Brigade found to be present in Rangoon Jail.

Machin was part of Wingate's Head Quarters on operation Longcloth and was present as an interrupter due to his fluency in Japanese. He was captured by the Japanese during the dispersal and was eventually taken to Singapore, where he was interrogated by the Kempai-Tai (Japanese secret police). He was one of a small group of Chindits to be removed from Rangoon Jail in late May 1943 and was eventually liberated from Changi Prison Camp in mid-1945.

The list is of great importance to me, as it is the first time that either James or my Grandfather are mentioned in any personal diary, memoir or book. It also clearly shows the soldier's POW number. One other point of interest is the presence of the the officers names above the three columns. It makes me wonder if Lieutenants Stock, Kerr and Spurlock were not in some way responsible for the men written beneath their names. The list runs in sequence of POW number across the page rather than down, separating the men in numerical rather than alphabetical order. The reason for this is unknown at present and could just be an idiosyncrasy of the time. You will also notice that the each column runs in rank order as the list progresses downward.

As for the six men of James's dispersal group, they are split across all three columns with Fred Lowe missing entirely from the list. The only non-Chindit to be found in the group is Cpl. Ford (Gloucesters) who seems to have been captured in the Maymyo area in 1943, having lived for over a year posing as a Burmese native. Patrick Flannigan Ford survived his time in Rangoon Jail, whether he returned to Maymyo or his home town of Dublin after the war is unknown.

Update 13/02/2013.

Seen below is a new set of photographs featuring James Ambrose and some of his comrades from Longcloth, mostly from training in Saugor in 1942. These came from a collection kept by Val Gornell's mother along with a letter. In this letter, two other soldiers are mentioned, George Wareing and Les Shaw, both from the Wirrall area of Liverpool. Neither man features in any paperwork in relation to the first Wingate expedition or are listed on the CWGC website, so it must be presumed that they both survived the war and returned home. Many thanks again to Val Gornell for kindly giving me permission to show these photographs of her father's WW2 service.

Update 19/07/2020.

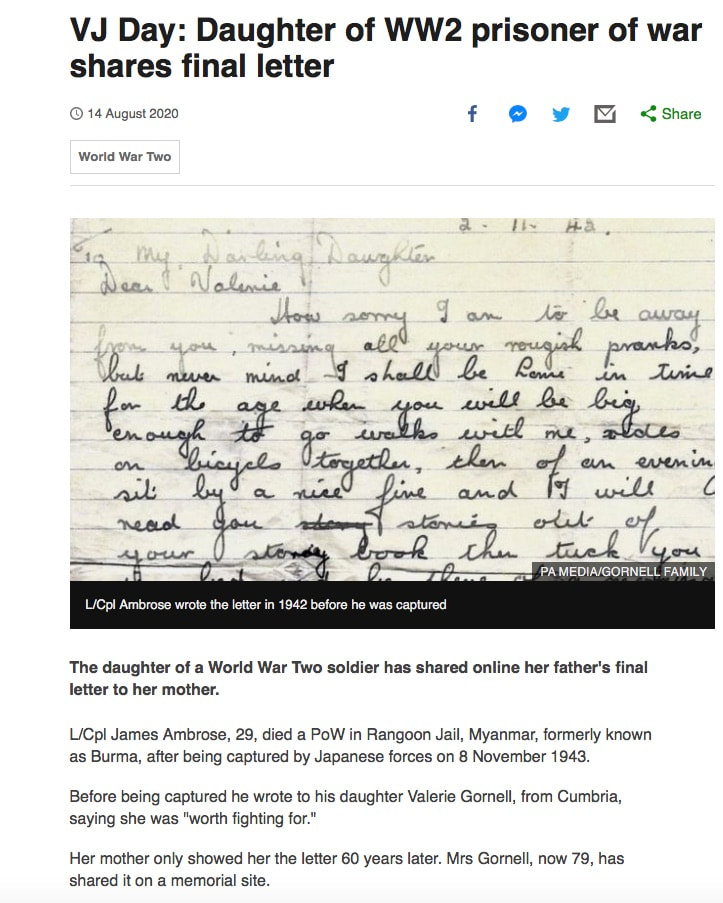

I was delighted to receive another email from Val Gornell in relation to the upcoming VJ Day 75 commemorations this August:

Hello Steve, it’s a while since I’ve been in touch with you and I hope you are well. I put a tribute to my Dad on the CWGC Wall of Remembrance and today I received an email from them asking if I would be prepared to talk to them about his war service for VJ Day. I said I would, but also directed them to your website and said what a tremendous amount of help you had given me. You are probably already known to them, but if not I hope this is OK?

Best wishes, Val Gornell.

I was pleased to see that Val's tribute to her father was featured by the BBC (Northwest) as part of their build up to this years VJ Day 75 commemorations. Here is a link to the BBC website and also for the purposes of prosperity, a gallery of images covering the on line article.

www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cumbria-53776378

I was delighted to receive another email from Val Gornell in relation to the upcoming VJ Day 75 commemorations this August:

Hello Steve, it’s a while since I’ve been in touch with you and I hope you are well. I put a tribute to my Dad on the CWGC Wall of Remembrance and today I received an email from them asking if I would be prepared to talk to them about his war service for VJ Day. I said I would, but also directed them to your website and said what a tremendous amount of help you had given me. You are probably already known to them, but if not I hope this is OK?

Best wishes, Val Gornell.

I was pleased to see that Val's tribute to her father was featured by the BBC (Northwest) as part of their build up to this years VJ Day 75 commemorations. Here is a link to the BBC website and also for the purposes of prosperity, a gallery of images covering the on line article.

www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cumbria-53776378

Copyright © Valerie Gornell and Steve Fogden 2011/13.

The Family of William Robert Jordan MM

Does anyone have any information on William Robert Jordan of the 13th King's Regiment. He was a 1943 Chindit from Failsworth in Lancashire. He, like James Ambrose and my Grandfather Arthur Leslie Howney, were all reported Missing in Action on the same day, 18/04/43.

William died on 01/03/44, almost certainly in Rangoon Jail. He was also awarded the Military Medal, so if anyone can help me find out about him or the reason for his award, I would be very grateful.

This was the post I left on the Burma Star forum on the 11th April 2009. It was part of my search for details about a soldier who I had always felt had something to do with my Grandfather’s time in Burma in 1943. They had both shared, along with Lance corporal James Ambrose exactly the same missing in action date, shown on all column 5 paperwork as 18/04/43.

William had been awarded the Military Medal (seen here, pictured right) and although I had found the London Gazette details, no citation had ever come to light. The award details were gazetted on 11th April 1946 and I felt sure they must have had something to do with his actions as a POW.

Then suddenly this October (2011), completely out of the blue, came an email response to my enquiry. It was from the family of William Jordan in the form of David and Brenda Pollitt. Brenda is William’s daughter and the family had just embarked on their own journey to find out what had happened to him back in 1943.

William died on 01/03/44, almost certainly in Rangoon Jail. He was also awarded the Military Medal, so if anyone can help me find out about him or the reason for his award, I would be very grateful.

This was the post I left on the Burma Star forum on the 11th April 2009. It was part of my search for details about a soldier who I had always felt had something to do with my Grandfather’s time in Burma in 1943. They had both shared, along with Lance corporal James Ambrose exactly the same missing in action date, shown on all column 5 paperwork as 18/04/43.

William had been awarded the Military Medal (seen here, pictured right) and although I had found the London Gazette details, no citation had ever come to light. The award details were gazetted on 11th April 1946 and I felt sure they must have had something to do with his actions as a POW.

Then suddenly this October (2011), completely out of the blue, came an email response to my enquiry. It was from the family of William Jordan in the form of David and Brenda Pollitt. Brenda is William’s daughter and the family had just embarked on their own journey to find out what had happened to him back in 1943.

‘Bob’ Jordan was born on 5th November 1917 in a village parish close to the town of Oldham. On all his Army records he was said to have come from the village of Failsworth, where some of his relatives still reside today.

Not much is known about his early life, but according to his service records, he did work as a labourer in the local rubber works.

Here is how David, Brenda and their family described how they had stumbled across my post on the Burma Star forum:

It all started with a medal yearbook from a carboot sale, which sent us on this journey to discover about the medal which has been sat in a drawer for over 60 years!! We visited the Manchester Military Museum who were very helpful pointing us in the right direction and told us about some websites to visit, and some books to read.

While we were searching trying to find the reason why Bob was given the Military Medal we stumbled on your message, which just floored us! We couldn't believe it.

Our only regret is that we wished we would have started this search many years ago. Brenda's mother never spoke about her husband; I suppose it was too painful for her to talk about, so no one ever mentioned it. Brenda can remember her dad sending her a dress from India which was very colourful but too big, and she couldn't wait to grow so she could wear it.

She also remembers going to the palace with her mother to be awarded the medal from King George, she thinks it must have been about November she remembers being freezing cold and it being very foggy, we have worked out it must have been 1946 or 1947. Brenda and her mother had their photo taken by the press and were told it would appear in the newspaper.

Brenda now 71, remembers family stories of how he died escaping from prison with others and went back to help a comrade and was killed. She understands he was awarded the Military Medal for this act.

I am very grateful to the Pollitt family, as David and Brenda kindly agreed to send down all the photos and documents they possessed about Bob Jordan and his time in Burma. Some of the official letters were extremely interesting to me, as I had never seen such documents before. Although the content of these official notices was very sad to read, it gave me some idea of what type of paperwork my own Nan would have received in 1945-46.

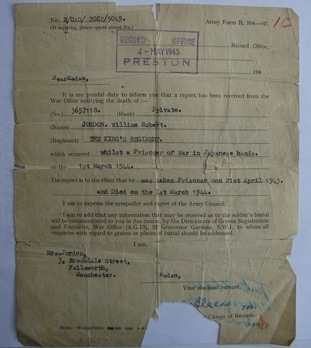

Seen below are two such documents, the first, informing the family of William's death in March 1944, however, because of the complication of him being a Prisoner of War, his death could not be confirmed until 4th May 1945. Rangoon Jail had been liberated just a few days beforehand, after the Japanese guards had vacated the premises on the 29th April. The second document appears to be the final issue death certificate from the War Office and was sent to the family in late June 1945. As stated earlier, this was the first time I had seen such official documents, especially ones that would have mirrored those received by my Nan that very same year. We need to bear in mind here that the families involved would have heard no firm news from the War Office since the men were posted as being missing, in the case of the Chindit POW's, this was nearly two years.

Not much is known about his early life, but according to his service records, he did work as a labourer in the local rubber works.

Here is how David, Brenda and their family described how they had stumbled across my post on the Burma Star forum:

It all started with a medal yearbook from a carboot sale, which sent us on this journey to discover about the medal which has been sat in a drawer for over 60 years!! We visited the Manchester Military Museum who were very helpful pointing us in the right direction and told us about some websites to visit, and some books to read.

While we were searching trying to find the reason why Bob was given the Military Medal we stumbled on your message, which just floored us! We couldn't believe it.

Our only regret is that we wished we would have started this search many years ago. Brenda's mother never spoke about her husband; I suppose it was too painful for her to talk about, so no one ever mentioned it. Brenda can remember her dad sending her a dress from India which was very colourful but too big, and she couldn't wait to grow so she could wear it.

She also remembers going to the palace with her mother to be awarded the medal from King George, she thinks it must have been about November she remembers being freezing cold and it being very foggy, we have worked out it must have been 1946 or 1947. Brenda and her mother had their photo taken by the press and were told it would appear in the newspaper.

Brenda now 71, remembers family stories of how he died escaping from prison with others and went back to help a comrade and was killed. She understands he was awarded the Military Medal for this act.

I am very grateful to the Pollitt family, as David and Brenda kindly agreed to send down all the photos and documents they possessed about Bob Jordan and his time in Burma. Some of the official letters were extremely interesting to me, as I had never seen such documents before. Although the content of these official notices was very sad to read, it gave me some idea of what type of paperwork my own Nan would have received in 1945-46.

Seen below are two such documents, the first, informing the family of William's death in March 1944, however, because of the complication of him being a Prisoner of War, his death could not be confirmed until 4th May 1945. Rangoon Jail had been liberated just a few days beforehand, after the Japanese guards had vacated the premises on the 29th April. The second document appears to be the final issue death certificate from the War Office and was sent to the family in late June 1945. As stated earlier, this was the first time I had seen such official documents, especially ones that would have mirrored those received by my Nan that very same year. We need to bear in mind here that the families involved would have heard no firm news from the War Office since the men were posted as being missing, in the case of the Chindit POW's, this was nearly two years.

William Jordan was posted to the 1/4 South Lancashire’s on 17/10/1940, he joined the men of ‘A’ Company (see photograph below, Bob is third from the right, as we look, third row from the front). It is difficult to know what other fighting William was involved in during the early years of WW2. The battalion had been present in Norway in the form of some Commando units, but it is not possible to place William here with any certainty.

Here again is what the family had to tell me about their knowledge of William’s Army service:

This is all we have of Bob’s records (referring to the documents they sent to me), Brenda was only 3 and a half when her father died, she did go and see her Dad’s family as often as she could, but no questions were ever asked about Burma or the war. Bob was often mentioned in conversation and it was clear that Brenda’s Gran absolutely worshipped him. I am ashamed to say that I had never heard the word ‘Chindits’ until a few weeks ago.

Just like my own Grandfather, William Jordan was not an original 13th Kingsman in 1942. According to his service records he was posted to the unit on 31st July 1942. Here is a quote from the 13th King’s War diary also dated 31/07/1942:

A draft of 144 men arrived here (Patharia) today. They had come from the 5th, 8th and 9th Kings Liverpool battalions, with a few men from the South Lancashire’s. On the whole they seem like a very good lot.

Using all the dates to be found on his service record it seems likely that William travelled out to India as part of the convoy WS (Winston’s Specials) 19. This, as with all the Far Eastern bound troopship convoys, would have left Liverpool, headed northwest into the Atlantic, then dropped south to dock at Freetown, Sierra Leone for supplies.

The soldiers themselves would not step onto solid ground until the convoy had split and their ship docked at either Cape Town or Durban in South Africa. Here the men were treated literally like Kings, as their South African hosts fed and entertained them for a memorable few days. Many men remarked about their time in South Africa, praising their hosts and revelling in a land that seemed to be untouched by the austerity and restrictions of war.

This is all we have of Bob’s records (referring to the documents they sent to me), Brenda was only 3 and a half when her father died, she did go and see her Dad’s family as often as she could, but no questions were ever asked about Burma or the war. Bob was often mentioned in conversation and it was clear that Brenda’s Gran absolutely worshipped him. I am ashamed to say that I had never heard the word ‘Chindits’ until a few weeks ago.

Just like my own Grandfather, William Jordan was not an original 13th Kingsman in 1942. According to his service records he was posted to the unit on 31st July 1942. Here is a quote from the 13th King’s War diary also dated 31/07/1942:

A draft of 144 men arrived here (Patharia) today. They had come from the 5th, 8th and 9th Kings Liverpool battalions, with a few men from the South Lancashire’s. On the whole they seem like a very good lot.

Using all the dates to be found on his service record it seems likely that William travelled out to India as part of the convoy WS (Winston’s Specials) 19. This, as with all the Far Eastern bound troopship convoys, would have left Liverpool, headed northwest into the Atlantic, then dropped south to dock at Freetown, Sierra Leone for supplies.

The soldiers themselves would not step onto solid ground until the convoy had split and their ship docked at either Cape Town or Durban in South Africa. Here the men were treated literally like Kings, as their South African hosts fed and entertained them for a memorable few days. Many men remarked about their time in South Africa, praising their hosts and revelling in a land that seemed to be untouched by the austerity and restrictions of war.

After landing at Bombay, Bob would have almost certainly been taken to the reinforcement camp of Deolali. It would most likely have been from here that he got his posting to join the 13th Kings at the Saugor (pronounced Saw-gore) training camp in the Central Provinces of India. He arrived by train at the Chindit training location on 8th August and was placed into column 5. His arrival preceded both my Grandfather and the eventual column commander Bernard Fergusson by a few weeks.

The men were placed into platoons at this stage and this is probably the least known area of the story, both for William and my Grandad. It is not possible at the moment to place them into any of the known groups, which have come to light through various books and diaries. NB. Photographed left is Bob and two of his mates, Pat and Tom, probably taken in Bombay during late 1942.

After the training was completed and the strengths of the columns had been bolstered and secured, the men took advantage of their last break from the preparations, with a final weeks leave in Bombay. Christmas came and went and as 1943 dawned the columns moved their winding way toward the Indian/Burmese border, travelling through the majestic scenery of Assam.

Column 5 crossed the Chindwin at a place called Hwematte and found themselves for the first time behind Japanese lines. William would have been present at all the columns well documented engagements that year, the railway demolitions at Bonchaung gorge, the crossing of the Irrawaddy at Tigyaing and of course the columns major action against the Japanese at Hintha.

It was undoubtedly at Hintha that column five’s story began to unravel. After the unit had disengaged the enemy in the village and the dispersal bugle had been sounded, the men were all meant to meet up again some 4 miles north east of their present position.

Only one third of the column ever made the fixed rendezvous, leaving around 200 men adrift from the unit and in some difficulty. The majority of this group were saved when in the far distance the sound of Dakota air supply planes could be heard and then the sight of parachutes falling from the sky were seen. This was column 7 receiving a much needed supply drop from the Chindit rear base at Agartala.

The men from column 5 moved as quickly as they could toward the drop zone, close to the banks of the River Shweli, here Major Gilkes the C/O of column 7 took them under his command. It is impossible to know whether William and my Grandfather were always together during the operation that year, but we do know that it was at this juncture that they found themselves in the same dispersal group, now led by the column 7 Burma Rifles officer John Musgrave-Wood.

Gilkes had decided that he and the men he commanded were going to head towards the Chinese borders to the northeast and exit Burma in this way. The trip would take much longer than a direct march west back to India, but was likely to be safer in regard to contact with the Japanese. Column 7 were relatively well fed and now sported new boots and weaponry from the recent supply drop, however, the stragglers from column 5 were not in such a fortunate position. The choice of China as the way out would be their eventual undoing.

The men were placed into platoons at this stage and this is probably the least known area of the story, both for William and my Grandad. It is not possible at the moment to place them into any of the known groups, which have come to light through various books and diaries. NB. Photographed left is Bob and two of his mates, Pat and Tom, probably taken in Bombay during late 1942.

After the training was completed and the strengths of the columns had been bolstered and secured, the men took advantage of their last break from the preparations, with a final weeks leave in Bombay. Christmas came and went and as 1943 dawned the columns moved their winding way toward the Indian/Burmese border, travelling through the majestic scenery of Assam.

Column 5 crossed the Chindwin at a place called Hwematte and found themselves for the first time behind Japanese lines. William would have been present at all the columns well documented engagements that year, the railway demolitions at Bonchaung gorge, the crossing of the Irrawaddy at Tigyaing and of course the columns major action against the Japanese at Hintha.

It was undoubtedly at Hintha that column five’s story began to unravel. After the unit had disengaged the enemy in the village and the dispersal bugle had been sounded, the men were all meant to meet up again some 4 miles north east of their present position.

Only one third of the column ever made the fixed rendezvous, leaving around 200 men adrift from the unit and in some difficulty. The majority of this group were saved when in the far distance the sound of Dakota air supply planes could be heard and then the sight of parachutes falling from the sky were seen. This was column 7 receiving a much needed supply drop from the Chindit rear base at Agartala.

The men from column 5 moved as quickly as they could toward the drop zone, close to the banks of the River Shweli, here Major Gilkes the C/O of column 7 took them under his command. It is impossible to know whether William and my Grandfather were always together during the operation that year, but we do know that it was at this juncture that they found themselves in the same dispersal group, now led by the column 7 Burma Rifles officer John Musgrave-Wood.

Gilkes had decided that he and the men he commanded were going to head towards the Chinese borders to the northeast and exit Burma in this way. The trip would take much longer than a direct march west back to India, but was likely to be safer in regard to contact with the Japanese. Column 7 were relatively well fed and now sported new boots and weaponry from the recent supply drop, however, the stragglers from column 5 were not in such a fortunate position. The choice of China as the way out would be their eventual undoing.

Pictured to the right is one of the group photos from Bob's time in India, once again my guess is that this is part of his platoon, seen here at the jungle training area in Saugor. Bob is seen standing far left as we look and sporting a fine moustache, with the men named Pat and Tom also in the back row. None of the other men can be identified at this time.

Of the group of around 30 men that left the northern banks of the Shweli River with Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood in early April 1943, only 9 would ever see their homes again. From documents held at the National Archives I now know that 6 men were to break off from the dispersal party at a village called Lonsa, these included William, my Grandfather, James Ambrose, Leon Frank, Edgar Burger and Fred Lowe.

It would appear from reading the literature available for this group, that it was William who assumed command. The men were reported as missing by Musgrave-Wood on the 18th April, but witness reports given later on in India, placed them at Lonsa and still free men on the 12th May.

The story of this group and their remaining days of freedom has been told by the only survivor, Pte. Leon Frank. It has always puzzled me why Leon, an original member of column 7, found himself in this group of soldiers from column 5. It is no coincidence however, that the only man from the column with a better rate of supply and especially food, was to be the only one to return home in 1945.

To read Leon’s account, please see either the story of Arthur Leslie Howney or that of James Ambrose, which is the story preceding this one, on the Family Pages 2. To listen to Leon Frank's audio sound recording, which he gave in 1995 at the Imperial War Museum, click on the link below:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80015277 (This link came back online in January 2013).

Of the group of around 30 men that left the northern banks of the Shweli River with Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood in early April 1943, only 9 would ever see their homes again. From documents held at the National Archives I now know that 6 men were to break off from the dispersal party at a village called Lonsa, these included William, my Grandfather, James Ambrose, Leon Frank, Edgar Burger and Fred Lowe.

It would appear from reading the literature available for this group, that it was William who assumed command. The men were reported as missing by Musgrave-Wood on the 18th April, but witness reports given later on in India, placed them at Lonsa and still free men on the 12th May.

The story of this group and their remaining days of freedom has been told by the only survivor, Pte. Leon Frank. It has always puzzled me why Leon, an original member of column 7, found himself in this group of soldiers from column 5. It is no coincidence however, that the only man from the column with a better rate of supply and especially food, was to be the only one to return home in 1945.

To read Leon’s account, please see either the story of Arthur Leslie Howney or that of James Ambrose, which is the story preceding this one, on the Family Pages 2. To listen to Leon Frank's audio sound recording, which he gave in 1995 at the Imperial War Museum, click on the link below:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80015277 (This link came back online in January 2013).

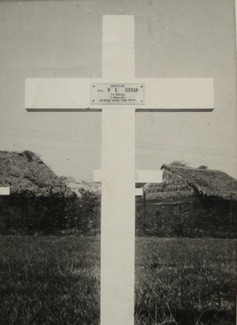

Lance Corporal 3657118 William Robert Jordan died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on 1st March 1944. His POW number in the jail was 428 and he was the last of the group of five men to perish inside that establishment. He was buried originally in the grounds of the English Cantonment Cemetery, located near the Royal Lakes in Rangoon. After the war, the Imperial Graves Commission moved all the men buried here to then newly constructed Rangoon War Cemetery, where they remain to this day.

Below are two photographs of William Jordan's memorials at Rangoon War Cemetery. The first photo was sent to the family by the Imperial War Graves Commission, probably in 1946. All the Chindit POW families as far as I understand were sent this image of the original grave marker. Later on these crosses were replaced by the memorial plaques as we know them today. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page. William's grave reference is 9.B.4 and lies just two graves down from my own Grandfather's in 9.B.2. The family chose to have their own epitaph placed on his memorial: Just a beautiful memory, resting where no shadows fall, R.I.P.

My heartfelt thanks go to the family of William Robert Jordan for allowing me to bring this story to these website pages, Bob was a true Chindit hero in every sense of the word.

Below are two photographs of William Jordan's memorials at Rangoon War Cemetery. The first photo was sent to the family by the Imperial War Graves Commission, probably in 1946. All the Chindit POW families as far as I understand were sent this image of the original grave marker. Later on these crosses were replaced by the memorial plaques as we know them today. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page. William's grave reference is 9.B.4 and lies just two graves down from my own Grandfather's in 9.B.2. The family chose to have their own epitaph placed on his memorial: Just a beautiful memory, resting where no shadows fall, R.I.P.

My heartfelt thanks go to the family of William Robert Jordan for allowing me to bring this story to these website pages, Bob was a true Chindit hero in every sense of the word.

Update.

The document pictured to the left came into my possession in February 2012 (please click on the image to enlarge). It shows a list of Chindit POW's complete with their prisoner number alongside their name. It was a listing created by Captain H. Machin, who was attempting to collate the men from 77th Indian Infantry Brigade found to be present in Rangoon Jail.

Machin was part of Wingate's Head Quarters on operation Longcloth and was present as an interrupter due to his fluency in Japanese. He was captured by the Japanese during the dispersal and was eventually taken to Singapore, where he was interrogated by the Kempai-Tai (Japanese secret police). He was one of a small group of Chindits to be removed from Rangoon Jail in late May 1943 and was eventually liberated from Changi Prison Camp in mid-1945.

The list is of great importance to me, as it is the first time that William Jordan or my Grandfather are mentioned in any personal diary or memoir from 1943. It also clearly shows the soldier's POW number. One other point of interest is the presence of the the officers names above the three columns. It makes me wonder if Lieutenants Stock, Kerr and Spurlock were not in some way responsible for the men written beneath their names. The list runs in sequence of POW number across the page rather than down, separating the men in numerical rather than alphabetical order. The reason for this is unknown at present and could just be an idiosyncrasy of the time. You will also notice that the each column runs in rank order as the list progresses downward.

As for the six men of William's dispersal group, they are split across all three columns with Fred Lowe missing entirely from the list. The only non-Chindit to be found in the group is Cpl. Ford (Gloucesters) who seems to have been captured in the Maymyo area in 1943, having lived for over a year posing as a Burmese native. Patrick Flannigan Ford survived his time in Rangoon Jail, whether he returned to Maymyo or his home town of Dublin after the war is unknown.

The document pictured to the left came into my possession in February 2012 (please click on the image to enlarge). It shows a list of Chindit POW's complete with their prisoner number alongside their name. It was a listing created by Captain H. Machin, who was attempting to collate the men from 77th Indian Infantry Brigade found to be present in Rangoon Jail.

Machin was part of Wingate's Head Quarters on operation Longcloth and was present as an interrupter due to his fluency in Japanese. He was captured by the Japanese during the dispersal and was eventually taken to Singapore, where he was interrogated by the Kempai-Tai (Japanese secret police). He was one of a small group of Chindits to be removed from Rangoon Jail in late May 1943 and was eventually liberated from Changi Prison Camp in mid-1945.

The list is of great importance to me, as it is the first time that William Jordan or my Grandfather are mentioned in any personal diary or memoir from 1943. It also clearly shows the soldier's POW number. One other point of interest is the presence of the the officers names above the three columns. It makes me wonder if Lieutenants Stock, Kerr and Spurlock were not in some way responsible for the men written beneath their names. The list runs in sequence of POW number across the page rather than down, separating the men in numerical rather than alphabetical order. The reason for this is unknown at present and could just be an idiosyncrasy of the time. You will also notice that the each column runs in rank order as the list progresses downward.

As for the six men of William's dispersal group, they are split across all three columns with Fred Lowe missing entirely from the list. The only non-Chindit to be found in the group is Cpl. Ford (Gloucesters) who seems to have been captured in the Maymyo area in 1943, having lived for over a year posing as a Burmese native. Patrick Flannigan Ford survived his time in Rangoon Jail, whether he returned to Maymyo or his home town of Dublin after the war is unknown.

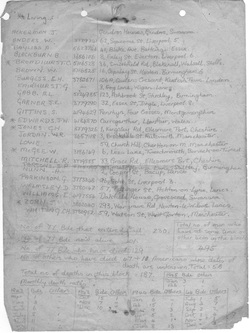

Another document to surface in February 2012 was a list of soldiers addresses collated by an officer from the 13th Kings in Rangoon Jail that year. Included in that short list was the then home address of William Robert Jordan.

Also shown on the document were the numbers for the 77th Brigade in terms of prisoners in Rangoon Jail, stated here as 230. I know from my own research that the numbers were slightly higher than this and probably more like 240.

At the time the list was compiled the death rate in Block 6 in terms of Longcloth personnel had reached 129. According to other records that number of Chindit deaths was reached in October 1944 and so makes this list very accurate and places it's collation toward the end of that year. The death rate is recorded both on a monthly and then yearly basis. There is no doubt in my mind that details were added to the page ongoing, as more men perished over time. The very fact that the list suggests the addressees were still 'living' is proof of this, as hardly any of the men mentioned actually made it home.

Please click on the image to enlarge.

Below is a photograph showing Bob Jordan, along with two of his mates from training at the Saugor camp. The other men are Alf Johnson (left) and 'Patto' Patterson seen to the right as we look. This image was sent to me by Gill Simmonds who is the granddaughter of Alfred Johnson and who contacted me in early March 2012. Gill had recognised her grandfather from one of the group photos shown in this story and decided to share her knowledge about his time in the months leading up to Operation Longcloth. Corporal Alfred Johnson was part of a platoon led by Lieutenant John Kerr in 1943, this unit was ambushed on 6th March whilst covering the demolitions at Bonchaung and Alfred was sadly killed in action. With the help of Gill and her family I hope to place Alfred's story on these pages presently.

Update 01/01/2014.

After an inexcusably long delay, here finally is a link to the story of Alfred Johnson and the other men lost at the engagement with the Japanese at Kyaik-in on March 6th 1943. Lieutenant John Kerr and the Fighting Men of Kyaik-in

Also shown on the document were the numbers for the 77th Brigade in terms of prisoners in Rangoon Jail, stated here as 230. I know from my own research that the numbers were slightly higher than this and probably more like 240.

At the time the list was compiled the death rate in Block 6 in terms of Longcloth personnel had reached 129. According to other records that number of Chindit deaths was reached in October 1944 and so makes this list very accurate and places it's collation toward the end of that year. The death rate is recorded both on a monthly and then yearly basis. There is no doubt in my mind that details were added to the page ongoing, as more men perished over time. The very fact that the list suggests the addressees were still 'living' is proof of this, as hardly any of the men mentioned actually made it home.

Please click on the image to enlarge.

Below is a photograph showing Bob Jordan, along with two of his mates from training at the Saugor camp. The other men are Alf Johnson (left) and 'Patto' Patterson seen to the right as we look. This image was sent to me by Gill Simmonds who is the granddaughter of Alfred Johnson and who contacted me in early March 2012. Gill had recognised her grandfather from one of the group photos shown in this story and decided to share her knowledge about his time in the months leading up to Operation Longcloth. Corporal Alfred Johnson was part of a platoon led by Lieutenant John Kerr in 1943, this unit was ambushed on 6th March whilst covering the demolitions at Bonchaung and Alfred was sadly killed in action. With the help of Gill and her family I hope to place Alfred's story on these pages presently.

Update 01/01/2014.

After an inexcusably long delay, here finally is a link to the story of Alfred Johnson and the other men lost at the engagement with the Japanese at Kyaik-in on March 6th 1943. Lieutenant John Kerr and the Fighting Men of Kyaik-in

Update 20/07/2013.

From recent information it is now possible to place Bob Jordan with Lieutenant John Kerr's platoon on March 4/6th 1943 at the engagement with the Japanese near the village of Kyaik-in. This was Column 5's first major skirmish with the enemy and came as the main body of the column was preparing to blow the railway at Bonchaung.

John Kerr's diary states: "Fight NW of Nankan. Fox, Dean, Mercer, Jordan (?). Lancaster killed, Sgt. Drummond and Alf Johnson too badly wounded to move. Cpl. Dale, Pte. JW Bell and self left wounded in village."