Enlistment and Joining Up

What did you join the Army for?

Why did you join the Army?

Why did you join the King's Regiment?

You must 'ave bin bloomin' well barmy.

Why did you join the Army?

Why did you join the King's Regiment?

You must 'ave bin bloomin' well barmy.

Although the men of the 13th King's that eventually fought as part of the first Wingate expedition were from all over the British Isles, the vast majority of the soldiers that comprised the battalion were from the Liverpool and Manchester areas.

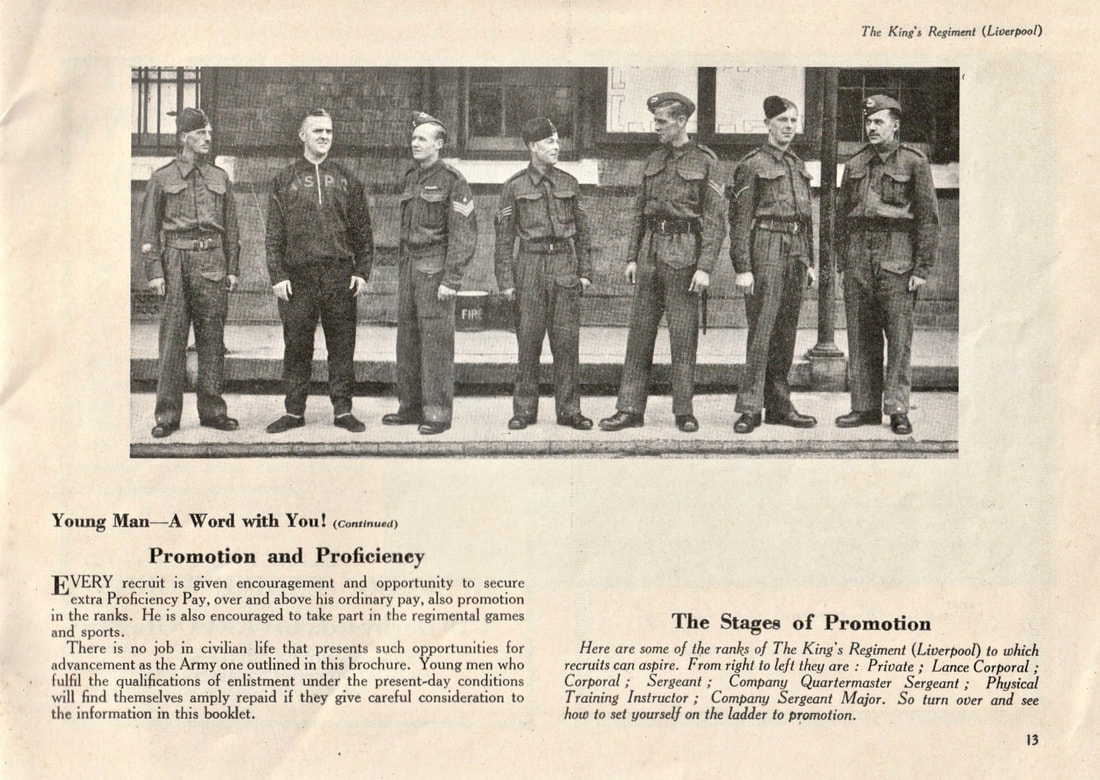

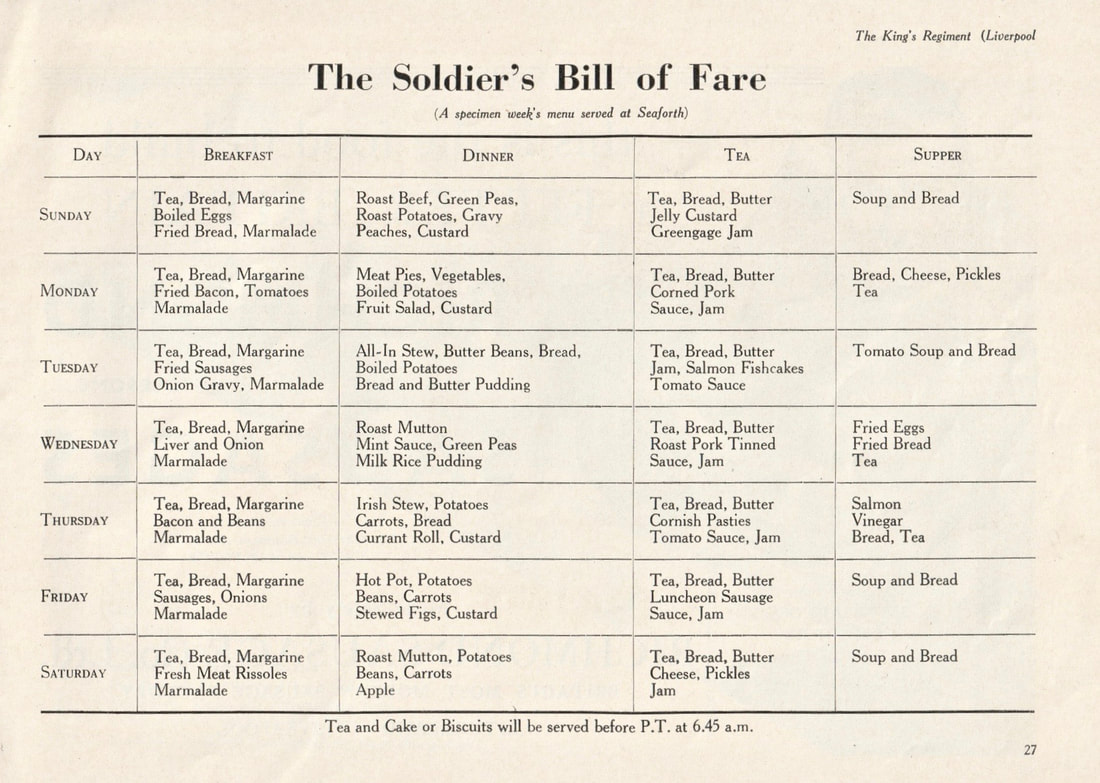

From a brochure produced by the King's Regimental Head Quarters at the Seaforth Barracks in March 1941, comes this interesting recruitment drive statement, aimed at the young men of Liverpool in an attempt to boost the number of regular enlistments into the Regiment.

To the Men of Liverpool

The British Empire is fighting today for everything that makes life worth living. If we should fail to win, our homes will be swept away; our freedom will be taken from us; many of us will end our lives in Nazi concentration camps and our children will grow up in a world wherein they will never have a chance. It is up to each one of us to do his or her utmost to ensure that we do win. How can a man do better at such a time than to join his local Regiment? Read through the following pages and learn something of what the Regiment has to offer you.

You will realise, if you are a thinking man, that by enlisting in the Army you are not only going to serve your country, but you are also embarking on a career which holds good prospects for getting on in life. You will not be joining a ‘dead end’ trade, but you will be adopting a profession. You will be seizing, perhaps the best chance which has ever come your way to better yourself. Take this opportunity now before it is too late.

Lieut. Colonel G.W.P. Thorn, the King’s Regiment (Liverpool).

From a brochure produced by the King's Regimental Head Quarters at the Seaforth Barracks in March 1941, comes this interesting recruitment drive statement, aimed at the young men of Liverpool in an attempt to boost the number of regular enlistments into the Regiment.

To the Men of Liverpool

The British Empire is fighting today for everything that makes life worth living. If we should fail to win, our homes will be swept away; our freedom will be taken from us; many of us will end our lives in Nazi concentration camps and our children will grow up in a world wherein they will never have a chance. It is up to each one of us to do his or her utmost to ensure that we do win. How can a man do better at such a time than to join his local Regiment? Read through the following pages and learn something of what the Regiment has to offer you.

You will realise, if you are a thinking man, that by enlisting in the Army you are not only going to serve your country, but you are also embarking on a career which holds good prospects for getting on in life. You will not be joining a ‘dead end’ trade, but you will be adopting a profession. You will be seizing, perhaps the best chance which has ever come your way to better yourself. Take this opportunity now before it is too late.

Lieut. Colonel G.W.P. Thorn, the King’s Regiment (Liverpool).

Young Man-A Word with You

This brochure is being distributed with a view to bringing to your notice the many advantages to be gained by joining the Army, and in particular your City Regiment, The King’s Regiment (Liverpool). It is fitting therefore, that I, the Recruiting Sergeant, should at this stage briefly outline what those advantages are.

1. Although Great Britain is at war, and the Government of our country has, by statute, called upon the manpower of our nation to serve their Country, either in the Navy, Army of Air Force, recruiting for the King’s Regiment will, from time to time, proceed in its normal manner, that is, on a voluntary basis.

2. The call for voluntary recruits to the Regiment only applies to men between the ages of 18 and 19 and 19 and 20 and a half years of age. It is important that these men should understand that voluntary recruiting does not apply to those engaged in an industry that is scheduled as a Reserved Occupation.

3. Young Man! If you come within the age limit and fulfil the high standard of physical fitness required by the Army of Britain, then come along and join the King’s Regiment.

An opportunity presents itself for young men between the ages of 18 and 19 to come along now and not wait to be called up. Enlist now for seven years in the Regular Army and insist on joining the King’s Regiment. Wars do not last forever. The Army encourages every private soldier to advance in his profession, and every recruit from the moment of enlistment, is given the facilities under the Army Educational Scheme to improve his general knowledge so that when he returns to civilian life, he will stand a far better chance of securing employment than did a soldier in the old days. It is no longer simply a question of making a man physically fit and proficient on the parade ground.

Every recruit is given encouragement and opportunity to secure extra Proficiency Pay over and above his ordinary pay, and also promotion in the ranks. He is also encouraged to take part in Regimental games and sports. Think this over, then call in and see me. I will be glad to give you complete details of the qualifications required for normal enlistment into the King’s Regiment, and also the periods and terms of service. You will find me at:

The Central Recruiting Office, Renshaw Hall, Renshaw Street, Liverpool; or at Price Street, Birkenhead.

This brochure is being distributed with a view to bringing to your notice the many advantages to be gained by joining the Army, and in particular your City Regiment, The King’s Regiment (Liverpool). It is fitting therefore, that I, the Recruiting Sergeant, should at this stage briefly outline what those advantages are.

1. Although Great Britain is at war, and the Government of our country has, by statute, called upon the manpower of our nation to serve their Country, either in the Navy, Army of Air Force, recruiting for the King’s Regiment will, from time to time, proceed in its normal manner, that is, on a voluntary basis.

2. The call for voluntary recruits to the Regiment only applies to men between the ages of 18 and 19 and 19 and 20 and a half years of age. It is important that these men should understand that voluntary recruiting does not apply to those engaged in an industry that is scheduled as a Reserved Occupation.

3. Young Man! If you come within the age limit and fulfil the high standard of physical fitness required by the Army of Britain, then come along and join the King’s Regiment.

An opportunity presents itself for young men between the ages of 18 and 19 to come along now and not wait to be called up. Enlist now for seven years in the Regular Army and insist on joining the King’s Regiment. Wars do not last forever. The Army encourages every private soldier to advance in his profession, and every recruit from the moment of enlistment, is given the facilities under the Army Educational Scheme to improve his general knowledge so that when he returns to civilian life, he will stand a far better chance of securing employment than did a soldier in the old days. It is no longer simply a question of making a man physically fit and proficient on the parade ground.

Every recruit is given encouragement and opportunity to secure extra Proficiency Pay over and above his ordinary pay, and also promotion in the ranks. He is also encouraged to take part in Regimental games and sports. Think this over, then call in and see me. I will be glad to give you complete details of the qualifications required for normal enlistment into the King’s Regiment, and also the periods and terms of service. You will find me at:

The Central Recruiting Office, Renshaw Hall, Renshaw Street, Liverpool; or at Price Street, Birkenhead.

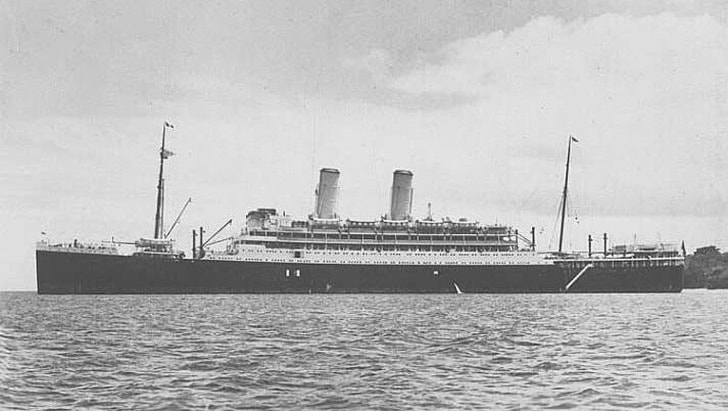

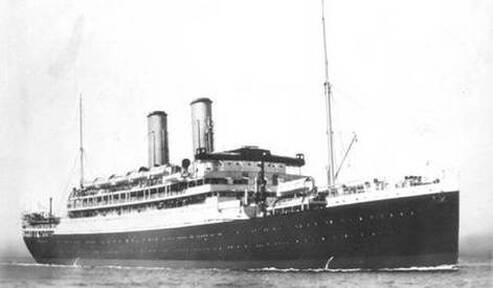

The 13th Kings aboard the troopship Oronsay

The SS Oronsay.

The SS Oronsay.

In early December 1941 an advance party consisting of Lieutenants Tuck and Saffer along with Captain Harry Holland left the battalion in their barracks at Blackburn, their job was to prepare the way for the men to board the troopship Oronsay quietly awaiting the men at Liverpool docks.

At 14.00 hours on the 8th of December the ship moved out into the Irish Sea and the battalion headed north toward Greenock, before pushing out into the Atlantic at first in a north-westerly course to avoid unwanted attention from enemy U-Boats.

There were over 3000 men aboard the troopship and conditions were very cramped for the Other ranks, who shared the hot and claustrophobic lower decks. Officers fared somewhat better aboard the ship.

Here is a quote from the diary of Captain Graham Hosegood an officer with the 13th King's:

I managed to get on board before most of the battalion and Holland showed me my cabin. Four of us were in it, but it is really comfy. It is on D deck and is cabin M. We have our own bathroom and lavatory and a nice little “storeroom”. It is a suite style and one of the best on board. We got our lunch about 1.30 and the food was excellent.

As with all convoy experiences in WW2, sea-sickness was a severe problem for many of the men, especially in those early days of the voyage as the ships passed through the rougher north Atlantic waters. There had been enemy submarine activity in the early part of the journey and although the Oronsay herself was not affected other ships had been attacked from within Convoy WS 14. Destroyer HMS Resolution joined the convoy and the sound of Sunderland flying boats (sub-killers as they were called back then) was a regular feature in the first week of the voyage.

The convoy had now turned course to a more southerly direction and was heading for its first re-supply docking at Freetown, Sierra Leone. By the 21st December the ship was anchored off the shores of Freetown and the native boats were ferrying out new supplies to the convoy. No shore leave was granted to the troops, but native boats visited the new convoy in an attempt to sell the men their wares. Here is another quote from Graham Hosegood’s diary from that time:

At 10.15 we saw the first sight of land for nearly a fortnight. It really was lovely. We could see the palm trees sticking up round Freetown while away in the distance there were big rolling hills. It was not long before the little 'bum' boats were along side selling oranges and bananas. Some of the other natives were diving into the water for coins. They amused us all right up to lunchtime.

On the 29th December the battalion suffered their first casualty away from the British mainland. From the battalion War Diary that year:

One of our OR's died today (29/12) from peritonitis and was buried at sea. It was hoped to have got him to Capetown for medical attention.

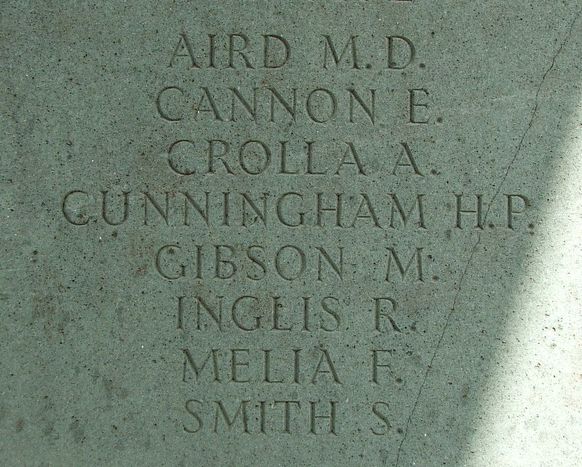

The unfortunate man was Pte. 3781551 Sinclair Smith, who is now remembered upon the Brookwood Memorial, Panel 9, Column 2. Here is a link to his CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2148166/SMITH,%20SINCLAIR

With the assistance of WW2Talk forum member, Andy B. I now have an image of Sinclair's inscription on the memorial at Brookwood, shown below alongside seven other Private soldiers from the King's (Liverpool) Regiment.

At 14.00 hours on the 8th of December the ship moved out into the Irish Sea and the battalion headed north toward Greenock, before pushing out into the Atlantic at first in a north-westerly course to avoid unwanted attention from enemy U-Boats.

There were over 3000 men aboard the troopship and conditions were very cramped for the Other ranks, who shared the hot and claustrophobic lower decks. Officers fared somewhat better aboard the ship.

Here is a quote from the diary of Captain Graham Hosegood an officer with the 13th King's:

I managed to get on board before most of the battalion and Holland showed me my cabin. Four of us were in it, but it is really comfy. It is on D deck and is cabin M. We have our own bathroom and lavatory and a nice little “storeroom”. It is a suite style and one of the best on board. We got our lunch about 1.30 and the food was excellent.

As with all convoy experiences in WW2, sea-sickness was a severe problem for many of the men, especially in those early days of the voyage as the ships passed through the rougher north Atlantic waters. There had been enemy submarine activity in the early part of the journey and although the Oronsay herself was not affected other ships had been attacked from within Convoy WS 14. Destroyer HMS Resolution joined the convoy and the sound of Sunderland flying boats (sub-killers as they were called back then) was a regular feature in the first week of the voyage.

The convoy had now turned course to a more southerly direction and was heading for its first re-supply docking at Freetown, Sierra Leone. By the 21st December the ship was anchored off the shores of Freetown and the native boats were ferrying out new supplies to the convoy. No shore leave was granted to the troops, but native boats visited the new convoy in an attempt to sell the men their wares. Here is another quote from Graham Hosegood’s diary from that time:

At 10.15 we saw the first sight of land for nearly a fortnight. It really was lovely. We could see the palm trees sticking up round Freetown while away in the distance there were big rolling hills. It was not long before the little 'bum' boats were along side selling oranges and bananas. Some of the other natives were diving into the water for coins. They amused us all right up to lunchtime.

On the 29th December the battalion suffered their first casualty away from the British mainland. From the battalion War Diary that year:

One of our OR's died today (29/12) from peritonitis and was buried at sea. It was hoped to have got him to Capetown for medical attention.

The unfortunate man was Pte. 3781551 Sinclair Smith, who is now remembered upon the Brookwood Memorial, Panel 9, Column 2. Here is a link to his CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2148166/SMITH,%20SINCLAIR

With the assistance of WW2Talk forum member, Andy B. I now have an image of Sinclair's inscription on the memorial at Brookwood, shown below alongside seven other Private soldiers from the King's (Liverpool) Regiment.

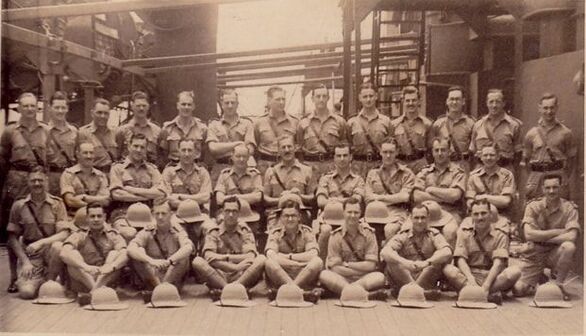

Pictured left, the officers of the 13th King's aboard the Oronsay, possibly taken as the men reached Durban in South Africa. (Photograph courtesy of Liz Hosegood).

As it transpired the Oronsay never docked in Capetown and headed slightly further around the South African coastline to Durban, where on 8th January it was greeted by the famous Lady in White (Perla Siedle), singing her arias as the convoy ships disgorged their human cargoes.

It is true to say that Durban and South African home life in general astounded the weary British soldiers. Durban welcomed the men with open arms and treated them to the best of everything, food, wine and entertainment.

Here is another quote from the Hosegood diaries:

Officer Commanding the camp spoke to us all at 10am. Went into Durban to cash a travellers cheque with Gilkes and Scott. Lunched at the Grill Room of the Playhouse cinema, had a grand meal. Met Bill & crowd at Paynes. Tea at the Balmoral, a rather good hotel on the front. Went up to Brian’s (Horncastle) Aunt’s house after dinner. Glorious to see all the lights. Very hot day but glorious.

It was during their short stay in Durban that a number of men went AWOL, they were not found and did not return before the convoy was due to resume its journey eastward. (NB. These men were eventually found and did rejoin the 13th Kings in Secunderabad). The battalion boarded the troopship Duchess of Athol on the 14th January for the resumption of their journey, but she developed engine trouble a little way out to sea. So back to Durban they went and here the battalion crammed aboard the troopship Andes, in which they completed the voyage to India.

On the 19th January part of WS 14 split away from the main group and headed for Singapore and Batavia, the rest of the ships headed across the Indian Ocean arriving ultimately at the Alexandra Docks in Bombay. On the 30th of January 1942 a section of the 1st Kings met their sister battalion as they disembarked and escorted them to their new home in the garrison town of Secunderabad.

Here is a link to a brilliant website Convoyweb, showing the route and composition of WS 14. WS stands for Winston’s Specials.

http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/ws/index.html

As a sub note to this story, the troopship Oronsay was sunk by an Italian submarine off the West African coastline on the 8th October 1942, when the Orient liner was on passage back to the UK from Capetown, she was torpedoed 500 miles from the West African city of Freetown. She was sailing unescorted at the time of the sinking and was unable to send out an SOS message, as the first torpedo strike damaged the ships radio aerial. This meant that the air search for the survivors was unfortunately delayed and this caused additional suffering to the crew because of the extended stay in lifeboats exposed to the sun and heat, in the end five of the crew died.

The Oronsay was torpedoed by the long range Italian submarine, Archimede, operating out of the German submarine base at Bordeaux, on the west coast of France. Twenty six of the Oronsay crew were captured and became prisoners of war. On its next patrol the Archimede itself was sunk off the Brazilian coast by two US Navy Catalina flying boats on the 15th of April 1943. To read more about the eventual fate of the SS Oronsay, please click on the following link to the diary of Pilot Officer Roger Quigley, a survivor of the sinking on the 8th October 1942:

www.shipsnostalgia.com/threads/troopship-oronsay-survivors-report.302544/#post-3068304

As it transpired the Oronsay never docked in Capetown and headed slightly further around the South African coastline to Durban, where on 8th January it was greeted by the famous Lady in White (Perla Siedle), singing her arias as the convoy ships disgorged their human cargoes.

It is true to say that Durban and South African home life in general astounded the weary British soldiers. Durban welcomed the men with open arms and treated them to the best of everything, food, wine and entertainment.

Here is another quote from the Hosegood diaries:

Officer Commanding the camp spoke to us all at 10am. Went into Durban to cash a travellers cheque with Gilkes and Scott. Lunched at the Grill Room of the Playhouse cinema, had a grand meal. Met Bill & crowd at Paynes. Tea at the Balmoral, a rather good hotel on the front. Went up to Brian’s (Horncastle) Aunt’s house after dinner. Glorious to see all the lights. Very hot day but glorious.

It was during their short stay in Durban that a number of men went AWOL, they were not found and did not return before the convoy was due to resume its journey eastward. (NB. These men were eventually found and did rejoin the 13th Kings in Secunderabad). The battalion boarded the troopship Duchess of Athol on the 14th January for the resumption of their journey, but she developed engine trouble a little way out to sea. So back to Durban they went and here the battalion crammed aboard the troopship Andes, in which they completed the voyage to India.

On the 19th January part of WS 14 split away from the main group and headed for Singapore and Batavia, the rest of the ships headed across the Indian Ocean arriving ultimately at the Alexandra Docks in Bombay. On the 30th of January 1942 a section of the 1st Kings met their sister battalion as they disembarked and escorted them to their new home in the garrison town of Secunderabad.

Here is a link to a brilliant website Convoyweb, showing the route and composition of WS 14. WS stands for Winston’s Specials.

http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/ws/index.html

As a sub note to this story, the troopship Oronsay was sunk by an Italian submarine off the West African coastline on the 8th October 1942, when the Orient liner was on passage back to the UK from Capetown, she was torpedoed 500 miles from the West African city of Freetown. She was sailing unescorted at the time of the sinking and was unable to send out an SOS message, as the first torpedo strike damaged the ships radio aerial. This meant that the air search for the survivors was unfortunately delayed and this caused additional suffering to the crew because of the extended stay in lifeboats exposed to the sun and heat, in the end five of the crew died.

The Oronsay was torpedoed by the long range Italian submarine, Archimede, operating out of the German submarine base at Bordeaux, on the west coast of France. Twenty six of the Oronsay crew were captured and became prisoners of war. On its next patrol the Archimede itself was sunk off the Brazilian coast by two US Navy Catalina flying boats on the 15th of April 1943. To read more about the eventual fate of the SS Oronsay, please click on the following link to the diary of Pilot Officer Roger Quigley, a survivor of the sinking on the 8th October 1942:

www.shipsnostalgia.com/threads/troopship-oronsay-survivors-report.302544/#post-3068304

Here is another photograph from the Oronsay in 1942. The officers shown are from left to right, back row, Gordon Foulds attached for a time to No. 5 Column and J.R. Carroll of No. 8 Column. Seated (L-R): Keith Gibbon Scott-Farnie who transferred to another Army unit whilst in India, Lieutenant Gilmour Menzies-Anderson and Lieutenant F. Summerfield. (Photograph courtesy of Jane Murray daughter of Lieutenant Scott-Farnie).

Notice all the men pose with their tropical issue topee or Wolseley style sun helmet. This headgear was soon swapped in most cases for the Australian style bush hat, which were the standard issue for the Chindits on both Wingate operations.

My final illustration for the King's journey out to India comes from the pocket diary of Pte. John Bromley who came from Chorley in Lancashire. John served in No. 8 Column in 1943 and was sadly being killed in action around the 18th April that year. Here is his run down of the Oronsay voyage:

Went to Liverpool to board the Oronsay on 05/12/1941. Sailed 08/12/1941. Started to wear our tropical kit on the 18th December. Arrived Freetown 21/12/1941, not allowed off of boat, no blackout. On guard 24/12/41 from 0900 hours to 0900 hours on the 25th, very hot day, winter season. Left Freetown 25/12/41 at 1200 hours, ceremony of crossing the line on 28/12/41. Landed Durban, South Africa 08/01/42, went to Clairwood Camp. Left Durban on 11/01/42 a Sunday, went onto the Duchess of Athol, sailed Tuesday the 13th, turned back after four hours. Went on the Andes (new ship), sailed Wednesday the 14th, caught up convoy Friday morning the 16th. Landed Bombay 21/01/42. Disembarked on 30/01/42. Went to Secunderabad on the 4pm train on Friday. Arrived at 9.30 pm Saturday at the Gough Barracks.

These barracks were to be the 13th King's home whilst they performed garrison and policing duties in the local area, this was right up until Wingate took them over, as his British Infantry element for the Longcloth operation. According to the diaries of Leon Frank (No. 7 Column) the battalion also spent some time at the Meadows Barracks which also formed part of the Secunderabad Cantonment in 1942.

Notice all the men pose with their tropical issue topee or Wolseley style sun helmet. This headgear was soon swapped in most cases for the Australian style bush hat, which were the standard issue for the Chindits on both Wingate operations.

My final illustration for the King's journey out to India comes from the pocket diary of Pte. John Bromley who came from Chorley in Lancashire. John served in No. 8 Column in 1943 and was sadly being killed in action around the 18th April that year. Here is his run down of the Oronsay voyage:

Went to Liverpool to board the Oronsay on 05/12/1941. Sailed 08/12/1941. Started to wear our tropical kit on the 18th December. Arrived Freetown 21/12/1941, not allowed off of boat, no blackout. On guard 24/12/41 from 0900 hours to 0900 hours on the 25th, very hot day, winter season. Left Freetown 25/12/41 at 1200 hours, ceremony of crossing the line on 28/12/41. Landed Durban, South Africa 08/01/42, went to Clairwood Camp. Left Durban on 11/01/42 a Sunday, went onto the Duchess of Athol, sailed Tuesday the 13th, turned back after four hours. Went on the Andes (new ship), sailed Wednesday the 14th, caught up convoy Friday morning the 16th. Landed Bombay 21/01/42. Disembarked on 30/01/42. Went to Secunderabad on the 4pm train on Friday. Arrived at 9.30 pm Saturday at the Gough Barracks.

These barracks were to be the 13th King's home whilst they performed garrison and policing duties in the local area, this was right up until Wingate took them over, as his British Infantry element for the Longcloth operation. According to the diaries of Leon Frank (No. 7 Column) the battalion also spent some time at the Meadows Barracks which also formed part of the Secunderabad Cantonment in 1942.

Pictured left is a photograph of Pte. John Bromley taken aboard the Oronsay in 1941/42. His diary entries from back then give a perfect overview of the ships voyage from Liverpool to India, with some important added detail, such as the name of the Army transit camp at Clairwood in Durban. Thanks go to John's granddaughter, Elaine Livesey and his father Jim for permission to use extracts from the diary and the Oronsay photograph.

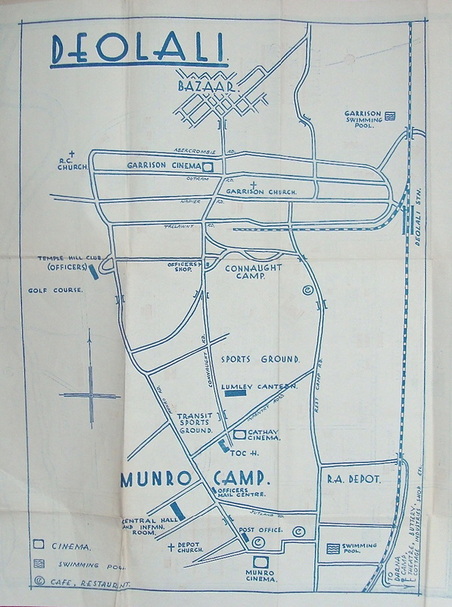

Although this clearly did not apply to the journey of the 13th Kings, as we have read from the above, many, if not the majority of men travelling to India during WW2 were processed at the Deolali Base Reinforcement Camp. This vast encampment was located roughly 100 miles north-east of Bombay and was formerly a Staff Training College. Deolali was not a place that was ever remembered with fondness by the visiting troops, it was where you would wait for your posting to another part of India and could be very boring and restrictive.

My grandfather, Pte. Arthur Howney, was stationed at the camp for a few days in September 1942, just before he received his posting to the 13th King's as a reinforcement and joined the battalion at the Saugor training camp in the Central Provinces of India.

Deolali is also the source of the slang phrase doolally meaning gone mad or eccentric, which comes from the colloquial doolally tap, describing a man with 'camp fever'. This saying was borne out of the length of time men remained at the Deolali Camp whilst waiting for their repatriation to the UK after their war service had ended. The encampment was also the inspiration as a setting, for the early episodes of the 1970's comedy sitcom, It Ain't Half Hot Mum.

For more information on repatriation from the Far East and the related official procedures involved in the preparation for the long voyage home, please click on the link below: http://www.britain-at-war.org.uk/ww2/Transport_Home/Westward_Bound/index.htm

Seen below is a simple outline map of the vast Deolali Encampment. Men were accommodated in long rows of wooden hutments or were billeted under canvas. Please click on the map to bring it forward on the page:

Although this clearly did not apply to the journey of the 13th Kings, as we have read from the above, many, if not the majority of men travelling to India during WW2 were processed at the Deolali Base Reinforcement Camp. This vast encampment was located roughly 100 miles north-east of Bombay and was formerly a Staff Training College. Deolali was not a place that was ever remembered with fondness by the visiting troops, it was where you would wait for your posting to another part of India and could be very boring and restrictive.

My grandfather, Pte. Arthur Howney, was stationed at the camp for a few days in September 1942, just before he received his posting to the 13th King's as a reinforcement and joined the battalion at the Saugor training camp in the Central Provinces of India.

Deolali is also the source of the slang phrase doolally meaning gone mad or eccentric, which comes from the colloquial doolally tap, describing a man with 'camp fever'. This saying was borne out of the length of time men remained at the Deolali Camp whilst waiting for their repatriation to the UK after their war service had ended. The encampment was also the inspiration as a setting, for the early episodes of the 1970's comedy sitcom, It Ain't Half Hot Mum.

For more information on repatriation from the Far East and the related official procedures involved in the preparation for the long voyage home, please click on the link below: http://www.britain-at-war.org.uk/ww2/Transport_Home/Westward_Bound/index.htm

Seen below is a simple outline map of the vast Deolali Encampment. Men were accommodated in long rows of wooden hutments or were billeted under canvas. Please click on the map to bring it forward on the page:

Jungle Training

The usual route for reinforcements in India was to spend time at camps to acclimatize to the heat, dust and noise of the sub-continent. The most famous of these was Deolali; this would be a likely destination for men like my Grandad as most soldiers passed through the camp at sometime during their Indian adventures. From here they would travel to their relevant training areas by train, journeys by which often took days on end in crowded carriages. Training for the potential Chindit operations comprised of continuous marches across the arid plains and scrublands in Central India. The marches were arduous and designed to weed out the weak of mind as well as the unfit soldier. Failure to complete these long marches meant the end of your chance to take part in the forthcoming expedition. It is said that each man was offered the chance to leave the training camp if he felt he was not able to complete the extremely testing regime. Nobody took up this option of his own choosing.

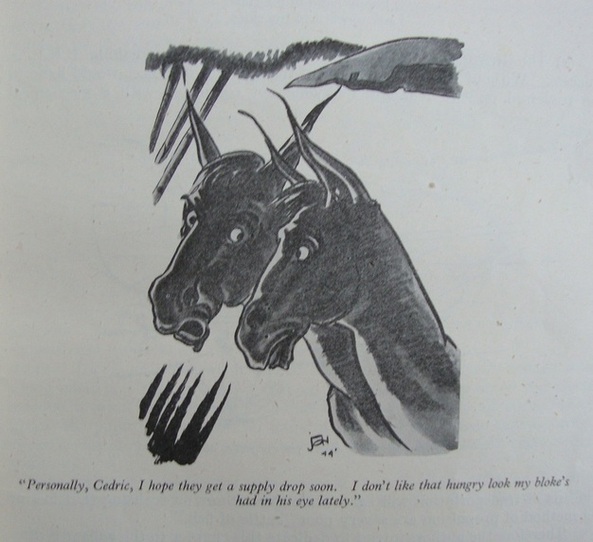

A general exercise day on these trips began with breakfast at 4.15am with the days march starting at 5am. Strict rules were to be adhered to at all times, no drinking water while on the move, columns to proceed in single file (column 'snake' formation), and all officers to eat and sleep with the group regardless of rank. This last order was to promote full respect and understanding amongst all soldiers and helped build a strong team ethic on which they would rely heavily in the jungles of Burma. Punishments were given for any breach of these rules including, loss of rations, isolation from the group, and even floggings for the more serious failures, such as falling asleep on watch duties. The marches were tough and with only a 10-minute break every 2 hours or so, only the hardiest of men survived to take part in the field exercises that followed. Columns were broken down into platoons of around 100 men. These groups were then responsible for all their own basic needs, these included defence of bivouac (camp area), food (mostly bully beef and army biscuit), and the collection of decent drinking water. The rations issued to the platoons were standard British army fare and must have become monotonous in practice, but going without food in the Burma jungle for days on end, meant these meals became extremely precious. Sometimes food rations could be supplemented by local jungle fair. The Chindit became partial to peacock, monkey (this resembled pork apparently), and in the jungle itself eventually even the trusted mule was not exempt from the cooking pot. The men trained in unarmed combat and were expert with their knives and bayonets.

The usual route for reinforcements in India was to spend time at camps to acclimatize to the heat, dust and noise of the sub-continent. The most famous of these was Deolali; this would be a likely destination for men like my Grandad as most soldiers passed through the camp at sometime during their Indian adventures. From here they would travel to their relevant training areas by train, journeys by which often took days on end in crowded carriages. Training for the potential Chindit operations comprised of continuous marches across the arid plains and scrublands in Central India. The marches were arduous and designed to weed out the weak of mind as well as the unfit soldier. Failure to complete these long marches meant the end of your chance to take part in the forthcoming expedition. It is said that each man was offered the chance to leave the training camp if he felt he was not able to complete the extremely testing regime. Nobody took up this option of his own choosing.

A general exercise day on these trips began with breakfast at 4.15am with the days march starting at 5am. Strict rules were to be adhered to at all times, no drinking water while on the move, columns to proceed in single file (column 'snake' formation), and all officers to eat and sleep with the group regardless of rank. This last order was to promote full respect and understanding amongst all soldiers and helped build a strong team ethic on which they would rely heavily in the jungles of Burma. Punishments were given for any breach of these rules including, loss of rations, isolation from the group, and even floggings for the more serious failures, such as falling asleep on watch duties. The marches were tough and with only a 10-minute break every 2 hours or so, only the hardiest of men survived to take part in the field exercises that followed. Columns were broken down into platoons of around 100 men. These groups were then responsible for all their own basic needs, these included defence of bivouac (camp area), food (mostly bully beef and army biscuit), and the collection of decent drinking water. The rations issued to the platoons were standard British army fare and must have become monotonous in practice, but going without food in the Burma jungle for days on end, meant these meals became extremely precious. Sometimes food rations could be supplemented by local jungle fair. The Chindit became partial to peacock, monkey (this resembled pork apparently), and in the jungle itself eventually even the trusted mule was not exempt from the cooking pot. The men trained in unarmed combat and were expert with their knives and bayonets.

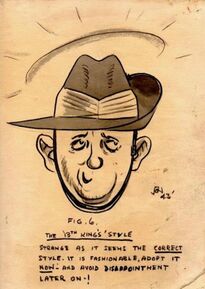

Picture above is a cartoon by artist Jon, who was in fact, Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood of the Burma Rifles in 1943. The image is taken courtesy of the book Jungle, Jungle, Little Chindit, written by Musgrave-Wood and Major Patrick Boyle.

Apart from mule husbandry and jungle survival the soldiers needed to be skilled users of map and compass. This, and being a strong swimmer were vital for their safe return to Allied held areas after the operation had ended. So it was that the selected soldiers moved into the camp that was to be their training area for the forthcoming operation into Burma. Some of the men had been training for the task for two or three months, others for a few short weeks, and as the Christmas season drew near, others were recruited almost at the last minute.

In the Abchand jungle of Patharia, in the Central Provinces of India the 77th Brigade trained hard. Marching miles each day, learning how to control mules for transporting their kit and fording fast flowing rivers. All of these things they would need to make the journey into the Burmese jungle a success. The men were separated into fighting units of column strength. This would be around 400 men, made up of infantry soldiers, Burma Riflemen who were jungle experts and local to the areas to be traversed, demolition engineers, signalmen and RAF officers who liaised with the Aircrews during the supply airdrops along the way. The 13th Kings were mainly attached to the columns of Major Gilkes and Major Scott who are the commanders of 7th and 8th columns respectively. Others were attached to Bernard Fergusson's column 5 and also to Brigade HQ.

The average age of the men of the 13th Kings was 33. This was a major factor in the eventual numbers of soldiers that dropped out of training through sickness and injury and the general survival rate of other ranks on the mission itself. It was at this point in time that the new draft of reinforcements arrived to bolster the Brigade numbers, amongst these men was my Grandfather. Here is a quote from the battalion War diary dated August 10th 1942:

Most of our sick are to be given an opportunity for getting over their illnesses. The battalion sick today, not counting the 80 men left behind at Patharia is; general illness 98, jungle sores 83 and hospital cases 34. This accounts for one third of the British Other Ranks on operational training.

One of the men left in Patharia was Richard Glyn Jones, who sadly became one of the early casualties from amongst the men of the 13th Kings, dying from dysentery in mid August 1942. You can read more about Richard and some of the other men who perished during training here:

Men Who Died During Training

Here are Richard Glyn Jones' CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2190491/JONES,%20RICHARD%20GLYN

Eventually Wingate took the drastic steps of removing the obviously unfit personnel from the training area. He then toughened up on the remaining men and their medical staff, insisting that minor illness be ignored and that the men take responsibility for their own well being as much as possible. This shake up seemed to work and in mid-November the last reorganisation took place when column six was disbanded and it's fit personnel redistributed amongst the other columns. Here is another quote from the War diary dated 14/11/42, which rather callously describes the final weeding out of unsuitable personnel.

Most of the unfit personnel left for the reinforcement camp Deolali today. It was originally thought that they were going to join our 1st battalion in barracks, this was an unpopular move, because we did not want to send them our cast offs.

The men that had been sent away from the original 13th King's battalion and back to resume garrison duties all over India, were given the derisory nickname of Jossers. This was an unsavoury term that the remaining men of the Kings had christened, implying that the recent leavers had let the side down in failing Chindit training. This was more than a little unfair in my opinion. The Kingsmen that survived the cut in late November now referred to themselves as Pukka Kings.

Apart from mule husbandry and jungle survival the soldiers needed to be skilled users of map and compass. This, and being a strong swimmer were vital for their safe return to Allied held areas after the operation had ended. So it was that the selected soldiers moved into the camp that was to be their training area for the forthcoming operation into Burma. Some of the men had been training for the task for two or three months, others for a few short weeks, and as the Christmas season drew near, others were recruited almost at the last minute.

In the Abchand jungle of Patharia, in the Central Provinces of India the 77th Brigade trained hard. Marching miles each day, learning how to control mules for transporting their kit and fording fast flowing rivers. All of these things they would need to make the journey into the Burmese jungle a success. The men were separated into fighting units of column strength. This would be around 400 men, made up of infantry soldiers, Burma Riflemen who were jungle experts and local to the areas to be traversed, demolition engineers, signalmen and RAF officers who liaised with the Aircrews during the supply airdrops along the way. The 13th Kings were mainly attached to the columns of Major Gilkes and Major Scott who are the commanders of 7th and 8th columns respectively. Others were attached to Bernard Fergusson's column 5 and also to Brigade HQ.

The average age of the men of the 13th Kings was 33. This was a major factor in the eventual numbers of soldiers that dropped out of training through sickness and injury and the general survival rate of other ranks on the mission itself. It was at this point in time that the new draft of reinforcements arrived to bolster the Brigade numbers, amongst these men was my Grandfather. Here is a quote from the battalion War diary dated August 10th 1942:

Most of our sick are to be given an opportunity for getting over their illnesses. The battalion sick today, not counting the 80 men left behind at Patharia is; general illness 98, jungle sores 83 and hospital cases 34. This accounts for one third of the British Other Ranks on operational training.

One of the men left in Patharia was Richard Glyn Jones, who sadly became one of the early casualties from amongst the men of the 13th Kings, dying from dysentery in mid August 1942. You can read more about Richard and some of the other men who perished during training here:

Men Who Died During Training

Here are Richard Glyn Jones' CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2190491/JONES,%20RICHARD%20GLYN

Eventually Wingate took the drastic steps of removing the obviously unfit personnel from the training area. He then toughened up on the remaining men and their medical staff, insisting that minor illness be ignored and that the men take responsibility for their own well being as much as possible. This shake up seemed to work and in mid-November the last reorganisation took place when column six was disbanded and it's fit personnel redistributed amongst the other columns. Here is another quote from the War diary dated 14/11/42, which rather callously describes the final weeding out of unsuitable personnel.

Most of the unfit personnel left for the reinforcement camp Deolali today. It was originally thought that they were going to join our 1st battalion in barracks, this was an unpopular move, because we did not want to send them our cast offs.

The men that had been sent away from the original 13th King's battalion and back to resume garrison duties all over India, were given the derisory nickname of Jossers. This was an unsavoury term that the remaining men of the Kings had christened, implying that the recent leavers had let the side down in failing Chindit training. This was more than a little unfair in my opinion. The Kingsmen that survived the cut in late November now referred to themselves as Pukka Kings.

Operational training was a dangerous occupation in it's own right and many men were injured or wounded during the summer months of 1942.

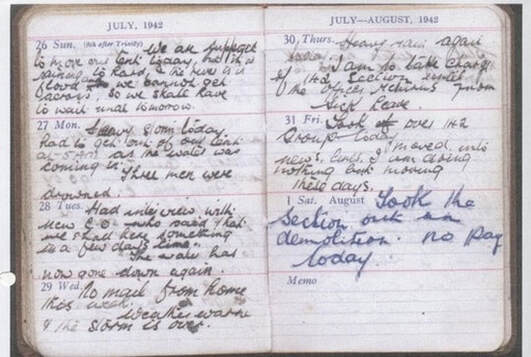

The image to your left is of Lieutenant Andrew O'Marah's personal diary recording the training period at the Saugor Camp. He was attached to the Brigade from the R.A.O.C. (Image courtesy of Kevin O'Marah).

On 27th July 1942, a terrible training accident occurred when the HQ Section of No. 6 Column were attempting to cross the Sunwar River.

CSM George Bateman was swept away by the strong current when he lost control of the power rope his unit were using to ford the river that day. Alongside him were Ptes. Harold Marsh and Francis McKibbin, all three men were drowned.

Seen below are maps showing the Saugor, Patharia and Abchand jungle areas. Also shown is the River Sonar, which is the correct spelling of the river in which the above mentioned men drowned. Please click on either map to bring it forward on the page.

The image to your left is of Lieutenant Andrew O'Marah's personal diary recording the training period at the Saugor Camp. He was attached to the Brigade from the R.A.O.C. (Image courtesy of Kevin O'Marah).

On 27th July 1942, a terrible training accident occurred when the HQ Section of No. 6 Column were attempting to cross the Sunwar River.

CSM George Bateman was swept away by the strong current when he lost control of the power rope his unit were using to ford the river that day. Alongside him were Ptes. Harold Marsh and Francis McKibbin, all three men were drowned.

Seen below are maps showing the Saugor, Patharia and Abchand jungle areas. Also shown is the River Sonar, which is the correct spelling of the river in which the above mentioned men drowned. Please click on either map to bring it forward on the page.

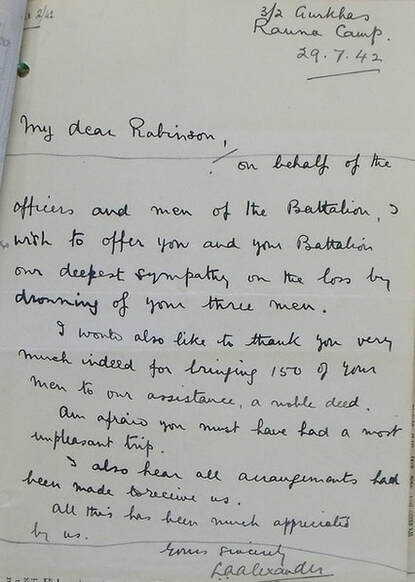

Pictured left is a personal letter from the Commander of the 3/2nd Gurkha Rifles on Operation Longcloth, Colonel L.A. Alexander. He sends his condolences to his opposite number in the King's Regiment, Lieutenant-Colonel W.M. Robinson, regarding the drownings on the 27th July.

Also mentioned in the letter is the 13th King's efforts in helping out a large section of Gurkha troops, who had become marooned on a sandbank whilst the Sunwar River levels rose so high it cut them off from the main group. The Gurkha Riflemen had to spend at least one full night perched high up in trees until the waters abated. To fully confirm the story here is a paraphrased extract from Captain Graham Hosegood's diary for the period.

River Sunwar rising rapidly, a raging torrent around the Irish Bridge nullah. CSM Bateman drowned, we all had to swim back to safety. Marsh and McKibbin also drowned, a terrible night with water raging all around us. This morning the water had subsided, found the bodies of Marsh and McKibbin and buried them. Mud terrible and has ruined all tents.

As a footnote to this sad account an award of the Royal Humane Society Testimonial was presented to Quartermaster Sergeant W.D.L. Bett, for his gallant attempt to save CSM Bateman.

Here are the drowned men's CWGC details:

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2189820/BATEMAN,%20GEORGE

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2190664/McKIBBIN,%20FRANCIS%20DONALD

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2190688/MARSH,%20HAROLD

Also mentioned in the letter is the 13th King's efforts in helping out a large section of Gurkha troops, who had become marooned on a sandbank whilst the Sunwar River levels rose so high it cut them off from the main group. The Gurkha Riflemen had to spend at least one full night perched high up in trees until the waters abated. To fully confirm the story here is a paraphrased extract from Captain Graham Hosegood's diary for the period.

River Sunwar rising rapidly, a raging torrent around the Irish Bridge nullah. CSM Bateman drowned, we all had to swim back to safety. Marsh and McKibbin also drowned, a terrible night with water raging all around us. This morning the water had subsided, found the bodies of Marsh and McKibbin and buried them. Mud terrible and has ruined all tents.

As a footnote to this sad account an award of the Royal Humane Society Testimonial was presented to Quartermaster Sergeant W.D.L. Bett, for his gallant attempt to save CSM Bateman.

Here are the drowned men's CWGC details:

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2189820/BATEMAN,%20GEORGE

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2190664/McKIBBIN,%20FRANCIS%20DONALD

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2190688/MARSH,%20HAROLD

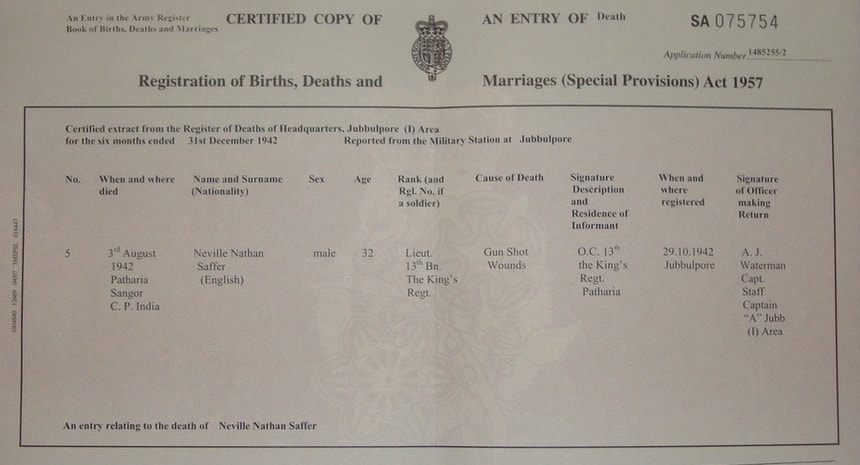

Here is another extract from the battalion War Diary in regard to the death of Lieutenant Neville Nathan Saffer (pictured left):

Lieutenant N.N. Saffer was killed this morning (03/08/42) by being shot by one of his platoon. The accident occurred in a weapons training parade and was purely accidental.

There had been some extremely exacting training exercises during the period and it is known that the men were under severe stress and in a weakened condition physically at the time of the accident. Lieutenant Saffer had been in charge of a small platoon of men and had recently put them through a tough regime of river-craft, including swimming lessons and raft building. One anecdotal account suggests that his death was caused by a mortar explosion, but all official documents confirm his death as by gunshot wounds.

Here are his CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2190991/SAFFER,%20NEVILLE%20NATHAN

There were obviously many more accidents and even deaths during the training for Operation Longcloth. Other incidents I have come across include crush injuries from falling mules and horses and motor vehicle accidents caused by landslide and night time travel.

Below is a copy of Neville Saffer's death certificate from the Overseas Deaths, British Army records held by the PRO. As with many of these type of documents, information is scant and limited in value.

Lieutenant N.N. Saffer was killed this morning (03/08/42) by being shot by one of his platoon. The accident occurred in a weapons training parade and was purely accidental.

There had been some extremely exacting training exercises during the period and it is known that the men were under severe stress and in a weakened condition physically at the time of the accident. Lieutenant Saffer had been in charge of a small platoon of men and had recently put them through a tough regime of river-craft, including swimming lessons and raft building. One anecdotal account suggests that his death was caused by a mortar explosion, but all official documents confirm his death as by gunshot wounds.

Here are his CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2190991/SAFFER,%20NEVILLE%20NATHAN

There were obviously many more accidents and even deaths during the training for Operation Longcloth. Other incidents I have come across include crush injuries from falling mules and horses and motor vehicle accidents caused by landslide and night time travel.

Below is a copy of Neville Saffer's death certificate from the Overseas Deaths, British Army records held by the PRO. As with many of these type of documents, information is scant and limited in value.

Update 20/09/2014. In the period leading up to Christmas 1942 the final finishing touches were being made to the Brigade. Last minute reinforcements were arriving from all over India to bolster column numbers and the last of the mules were being allocated to the Chindit groups still without their animals.

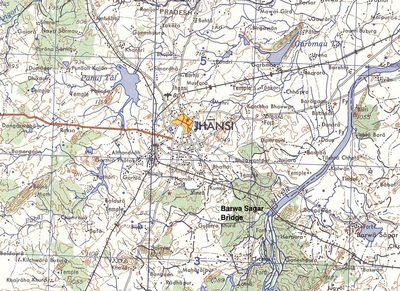

On the 9th December all columns had been involved in a full field exercise. This included a three day route march up to the rail station at Jhansi, where certain columns were pitched against each other, some defending and some attacking the station buildings. Wingate was not overly impressed by the Chindits performance at Jhansi and so another full Brigade exercise was arranged for late December. It was at this juncture that the officers of 77th Indian Infantry Brigade were issued with Wingate's orders for the forthcoming operation.

Here transcribed, is the twenty point list given to all column officers by Wingate on the 29th December 1942. Some of the younger officers present were shocked by Wingate's ideas and the language used in the document, if they had not already guessed previously, they now knew that they were in for a tough and uncompromising time once inside Burma.

Secret (29 Dec. 1942).

77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Maxims for all Officers

1.The Chindwin is your Jordan, once crossed there is no re-crossing. The exit from Burma is via Rangoon.

2. Success in operations depends on the perfecting of an exact and well conducted drill for every procedure.

3. Our reply to noise is silence.

4. When in doubt do not fire.

5. Never await the enemy's blow, evade it.

6. Fight when surprise has been gained. When surprise is lost at the outset, break off the action and come again.

7. Security is gained by intelligence, good dispersal procedure and counter attack. Thus all depends on good 'guerilla' procedure plus careful drill. Read and then re-read "Security in bivouac".

8. Always maintain a margin of strength for a time of need. It is the reserve of energy that saves from disaster, that gives the weight required for victory.

9. Avoid defiles. If you must use them, secure your flanks first. Pass by night whenever possible. For us, a defile may be defined as a track from which dispersal is not possible owing to physical obstacles.

10. Times of darkness, of rain, mist and storm, these are our times of achievement.

11. Never retrace your steps.

12. The movement of the column must be unpredictable, even for it's own members.

13. Never bivouac within three miles of a motor road or waterway. Three miles of good forest will give the same protection as ten miles of open country.

14. Use your W/T (radio) to capacity, it is your greatest weapon.

15. Use every weapon and every man to capacity. It is their combined and simultaneous employment that gives strength. Work together and rest together.

16. Festina lente (make haste slowly). Let your haste be a considered haste, the fitting end to a leisurely examination and preparation. Speed should be the result, not of fear and confusion, but of superior knowledge, planning and drill.

17. Intelligence is useless unless it passed on. Use your W/T.

18. See that your men think the same of the situation as you do. For this, constant talks and explanations will be necessary.

19. Get rid of casualties, never keep serious cases with the Column.

20. Spend your cash.

Signed Orde C. Wingate (Brigadier Commander 77 Ind. Inf. Brigade).

As mentioned above a further operational exercise was organised for the Brigade in late December 1942. This exercise focussed heavily on the transport of a column over water. Transcribed below is the written programme for the exercise and what it hoped to achieve. Reading through the document today it is obvious to see that much more work was needed, even at this late stage, before the men were fit and ready for the expedition into Burma.

Copy

77 Indian Infantry Brigade

Training Programme 21/12/1942 to 07/01/1943.

General. The above mentioned period will be divided in to two periods, the first devoted to recuperation after the recent exercise at the Jhansi rail station, the second to carrying out training along the lines indicated by that exercise.

The first period will terminate on 26th December. During both periods a certain number of Brigade courses will take place.

1. Animal Management. This course will be conducted by the training teams now with the Brigade, under the general direction of Captain Carey-Foster. Separate instructions have now been issued.

2. Horsemastership. Officer courses in riding and 'horsemastership' have been arranged by Carey-Foster. Group and Column Commanders will arrange for the attendance of as many Officers as possible.

3. TEWTS and Lectures. T.E.W.T's (Tactical exercises without troops) and lectures should be arranged by Group Commanders for all officers in order to correct faults brought out by the recent exercise. Not less than three Brigade level T.E.W.T's are to be held before January 7th. Separate instructions will follow shortly.

Column Training Period 27/12/1942 to 07/01/1943 inclusive.

1. River Crossing. Every column will carry out a crossing of the Betwa River, complete with animals, men and equipment. In order that full value may be obtained from these exercises, columns will use their own mules, muleteers and equipment. Additional mules, to make up a proper strength may be borrowed from other Columns not involved with the exercise on the date in question.

The crossing will be carried out as follows:

The Column will parade at 0800 hours on the date allotted on the parade ground and will be moved off by route march cross country to the stretch of the Betwa, north of Bawar Sagar Railway Bridge. The crossing point over the Betwa will be selected by the Burma Rifle Recce section and the crossing to the far bank will be carried out as a Military Operation.

It is estimated that the initial crossing will take approximately six hours. The Column will spend the following period of darkness on the right bank and will return on the following day across the Betwa. The second crossing will afford an opportunity to correct any faults experienced on the first attempt. A mock attack will be staged on the second crossing. Dates for the exercise are as follows:

Column 1 and 2, 27th and 28th December 1942.

Column 3 and 4, 29th and 30th December 1942.

Column 5 and 6, 31st December 1942 and 1st January 1943.

Column 7 and 8, 2nd and 3rd January 1943.

Rubber boats will be pooled by the Group Commanders for the purpose of the exercise. Points to concentrate on are; the swimming of mules and horses, the dry porterage of articles such as wireless sets, explosives etc. The free swimming of fighting personnel across the river by water-wings to gain a bridgehead on the far bank is an essential element of the exercise. During the period directly before the exercise begins, all water-wings will be thoroughly tested.

NB. The actual crossing of the river should not commence before 11.00 hours owing to the cold weather presently experienced.

2. Battle Practice. There are two battle practice ranges in Jhansi, both these are now at the disposal of the Brigade. Group Commanders will ensure that columns use these on a daily basis and that all troops are familiar with their battle plans. These programmes will be submitted to the relevant Head quarters by 24th December 1942.

3. The Zeroing of all Small Arms. All rifles will be zeroed before leaving Jhansi. Great importance is attached to this procedure. In many cases foresights will need to be changed and in the event of any deficiencies a report will be issued to this office.

4. Completion of Mobilisation. Much remains to be done in completing stores and equipment for operational use. The recent exercises have shown that certain adaptations are necessary in respect of carrying equipment. There are two R.E. Workshop Companys at Jhansi and they have agreed to undertake any necessary works. Column Commanders will at once approach these Coys using Major J.M. Calvert R.E. as liaison to ensure that full advantage is taken of this opportunity to make alterations and improvements.

Signed. Orde C. Wingate (Brigadier, Commander 77 Indian Infantry Brigade).

20th December 1942.

NB. Column 6 did not make the above appointment on New Years Day 1943. This unit was disbanded on Boxing Day 1942 due to the large number of ill and unfit men present in the column. The remaining personnel who were still fit for operational duty were redistributed amongst the other Chindit Columns.

Shown below is a map of the Jhansi/Betwa River area and a photograph of the Bawar Sagar Rail Bridge taken in December 1942 by Lance Corporal James Ambrose of Chindit Column 5. Also included below are some present day images of Jhansi and the Betwa River areas, taken by Chindit grandson, Daniel Berke. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

On the 9th December all columns had been involved in a full field exercise. This included a three day route march up to the rail station at Jhansi, where certain columns were pitched against each other, some defending and some attacking the station buildings. Wingate was not overly impressed by the Chindits performance at Jhansi and so another full Brigade exercise was arranged for late December. It was at this juncture that the officers of 77th Indian Infantry Brigade were issued with Wingate's orders for the forthcoming operation.

Here transcribed, is the twenty point list given to all column officers by Wingate on the 29th December 1942. Some of the younger officers present were shocked by Wingate's ideas and the language used in the document, if they had not already guessed previously, they now knew that they were in for a tough and uncompromising time once inside Burma.

Secret (29 Dec. 1942).

77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Maxims for all Officers

1.The Chindwin is your Jordan, once crossed there is no re-crossing. The exit from Burma is via Rangoon.

2. Success in operations depends on the perfecting of an exact and well conducted drill for every procedure.

3. Our reply to noise is silence.

4. When in doubt do not fire.

5. Never await the enemy's blow, evade it.

6. Fight when surprise has been gained. When surprise is lost at the outset, break off the action and come again.

7. Security is gained by intelligence, good dispersal procedure and counter attack. Thus all depends on good 'guerilla' procedure plus careful drill. Read and then re-read "Security in bivouac".

8. Always maintain a margin of strength for a time of need. It is the reserve of energy that saves from disaster, that gives the weight required for victory.

9. Avoid defiles. If you must use them, secure your flanks first. Pass by night whenever possible. For us, a defile may be defined as a track from which dispersal is not possible owing to physical obstacles.

10. Times of darkness, of rain, mist and storm, these are our times of achievement.

11. Never retrace your steps.

12. The movement of the column must be unpredictable, even for it's own members.

13. Never bivouac within three miles of a motor road or waterway. Three miles of good forest will give the same protection as ten miles of open country.

14. Use your W/T (radio) to capacity, it is your greatest weapon.

15. Use every weapon and every man to capacity. It is their combined and simultaneous employment that gives strength. Work together and rest together.

16. Festina lente (make haste slowly). Let your haste be a considered haste, the fitting end to a leisurely examination and preparation. Speed should be the result, not of fear and confusion, but of superior knowledge, planning and drill.

17. Intelligence is useless unless it passed on. Use your W/T.

18. See that your men think the same of the situation as you do. For this, constant talks and explanations will be necessary.

19. Get rid of casualties, never keep serious cases with the Column.

20. Spend your cash.

Signed Orde C. Wingate (Brigadier Commander 77 Ind. Inf. Brigade).

As mentioned above a further operational exercise was organised for the Brigade in late December 1942. This exercise focussed heavily on the transport of a column over water. Transcribed below is the written programme for the exercise and what it hoped to achieve. Reading through the document today it is obvious to see that much more work was needed, even at this late stage, before the men were fit and ready for the expedition into Burma.

Copy

77 Indian Infantry Brigade

Training Programme 21/12/1942 to 07/01/1943.

General. The above mentioned period will be divided in to two periods, the first devoted to recuperation after the recent exercise at the Jhansi rail station, the second to carrying out training along the lines indicated by that exercise.

The first period will terminate on 26th December. During both periods a certain number of Brigade courses will take place.

1. Animal Management. This course will be conducted by the training teams now with the Brigade, under the general direction of Captain Carey-Foster. Separate instructions have now been issued.

2. Horsemastership. Officer courses in riding and 'horsemastership' have been arranged by Carey-Foster. Group and Column Commanders will arrange for the attendance of as many Officers as possible.

3. TEWTS and Lectures. T.E.W.T's (Tactical exercises without troops) and lectures should be arranged by Group Commanders for all officers in order to correct faults brought out by the recent exercise. Not less than three Brigade level T.E.W.T's are to be held before January 7th. Separate instructions will follow shortly.

Column Training Period 27/12/1942 to 07/01/1943 inclusive.

1. River Crossing. Every column will carry out a crossing of the Betwa River, complete with animals, men and equipment. In order that full value may be obtained from these exercises, columns will use their own mules, muleteers and equipment. Additional mules, to make up a proper strength may be borrowed from other Columns not involved with the exercise on the date in question.

The crossing will be carried out as follows:

The Column will parade at 0800 hours on the date allotted on the parade ground and will be moved off by route march cross country to the stretch of the Betwa, north of Bawar Sagar Railway Bridge. The crossing point over the Betwa will be selected by the Burma Rifle Recce section and the crossing to the far bank will be carried out as a Military Operation.

It is estimated that the initial crossing will take approximately six hours. The Column will spend the following period of darkness on the right bank and will return on the following day across the Betwa. The second crossing will afford an opportunity to correct any faults experienced on the first attempt. A mock attack will be staged on the second crossing. Dates for the exercise are as follows:

Column 1 and 2, 27th and 28th December 1942.

Column 3 and 4, 29th and 30th December 1942.

Column 5 and 6, 31st December 1942 and 1st January 1943.

Column 7 and 8, 2nd and 3rd January 1943.

Rubber boats will be pooled by the Group Commanders for the purpose of the exercise. Points to concentrate on are; the swimming of mules and horses, the dry porterage of articles such as wireless sets, explosives etc. The free swimming of fighting personnel across the river by water-wings to gain a bridgehead on the far bank is an essential element of the exercise. During the period directly before the exercise begins, all water-wings will be thoroughly tested.

NB. The actual crossing of the river should not commence before 11.00 hours owing to the cold weather presently experienced.

2. Battle Practice. There are two battle practice ranges in Jhansi, both these are now at the disposal of the Brigade. Group Commanders will ensure that columns use these on a daily basis and that all troops are familiar with their battle plans. These programmes will be submitted to the relevant Head quarters by 24th December 1942.

3. The Zeroing of all Small Arms. All rifles will be zeroed before leaving Jhansi. Great importance is attached to this procedure. In many cases foresights will need to be changed and in the event of any deficiencies a report will be issued to this office.

4. Completion of Mobilisation. Much remains to be done in completing stores and equipment for operational use. The recent exercises have shown that certain adaptations are necessary in respect of carrying equipment. There are two R.E. Workshop Companys at Jhansi and they have agreed to undertake any necessary works. Column Commanders will at once approach these Coys using Major J.M. Calvert R.E. as liaison to ensure that full advantage is taken of this opportunity to make alterations and improvements.

Signed. Orde C. Wingate (Brigadier, Commander 77 Indian Infantry Brigade).

20th December 1942.

NB. Column 6 did not make the above appointment on New Years Day 1943. This unit was disbanded on Boxing Day 1942 due to the large number of ill and unfit men present in the column. The remaining personnel who were still fit for operational duty were redistributed amongst the other Chindit Columns.

Shown below is a map of the Jhansi/Betwa River area and a photograph of the Bawar Sagar Rail Bridge taken in December 1942 by Lance Corporal James Ambrose of Chindit Column 5. Also included below are some present day images of Jhansi and the Betwa River areas, taken by Chindit grandson, Daniel Berke. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 03/10/2021.

Further to the list of Wingate's maxims seen in the text above, Bernard Fergusson in his book Wild Green Earth, explains some of the more important elements of his commander's philosophy and how these might play out in the field:

Orde Wingate had three sound slogans for fighting the Japanese which stood the test of time. They were: Don't be Predictable. When in Doubt, Don't Shoot and The Answer to Noise is Silence. Predictability was a Jap sin, and it was a sheer gain to us. Ourselves, we went to great lengths to observe this basic Wingate law. Only once was it badly broken, and from that breach sprang all our troubles in 1943. Our whole Force, less certain columns outside the ring, allowed itself to linger in the great loop formed by the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers, long enough for the Japs to become aware of it. They knew that we must break out, and lined the rivers to prevent our doing so. We had excuses in plenty, but the Law knows no excuses, and that particular law is fundamental. We never offended again.

When in Doubt, Don't Shoot. I believe that in New Guinea the Australians followed a different teaching and continued to believe in it. I have heard for instance, that once bivouacked for the night, they forbade all movement outside the perimeter and brought down a heavy fire without question if such movement were heard. I prefer the Wingate teaching; the other leads to trigger-happiness and jumpiness and mutual slaughter. We never forbade movement outside the perimeter; although anybody going out had to be properly cleared before doing so. Certainly, if this slogan had not been learned and taught ad nauseam we should have had a lot of unnecessary firing. As it was, men repeated it in moments of stress, and it induced self-control and self-confidence of a high order.

The same applies to the last slogan, The Answer to Noise is Silence. The Jap relies on noise. He shrieks when he goes into action; he fires shots at random when he thinks he is on to something suspicious. If he is answered by noise, he knows the most of what he wants to know: that somebody is there; whereabouts he is and his approximate strength. All this knowledge he has won for the price of a few rounds. If, on the other hand, he gets no answering cry or shot, he is either falsely reassured or thoroughly discomfited; if the latter, he has lost the moral initiative and the seeds of nervousness are sown in him. And again, he who answers with silence knows that he has given nothing away, and feels himself to be a Strong, as well as a Silent, Man. For the worst thing that can befall the commander of a small force in a jungle encounter is the loss of control. When indiscriminate shooting starts, you have begun to lose control; from there it is only a small step to losing moral and physical control of your force. When that disintegrates you are sunk; and soon you will be fighting other elements of your own men.

Bernard Fergusson, Wild Green Earth, 1946.

Further to the list of Wingate's maxims seen in the text above, Bernard Fergusson in his book Wild Green Earth, explains some of the more important elements of his commander's philosophy and how these might play out in the field:

Orde Wingate had three sound slogans for fighting the Japanese which stood the test of time. They were: Don't be Predictable. When in Doubt, Don't Shoot and The Answer to Noise is Silence. Predictability was a Jap sin, and it was a sheer gain to us. Ourselves, we went to great lengths to observe this basic Wingate law. Only once was it badly broken, and from that breach sprang all our troubles in 1943. Our whole Force, less certain columns outside the ring, allowed itself to linger in the great loop formed by the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers, long enough for the Japs to become aware of it. They knew that we must break out, and lined the rivers to prevent our doing so. We had excuses in plenty, but the Law knows no excuses, and that particular law is fundamental. We never offended again.

When in Doubt, Don't Shoot. I believe that in New Guinea the Australians followed a different teaching and continued to believe in it. I have heard for instance, that once bivouacked for the night, they forbade all movement outside the perimeter and brought down a heavy fire without question if such movement were heard. I prefer the Wingate teaching; the other leads to trigger-happiness and jumpiness and mutual slaughter. We never forbade movement outside the perimeter; although anybody going out had to be properly cleared before doing so. Certainly, if this slogan had not been learned and taught ad nauseam we should have had a lot of unnecessary firing. As it was, men repeated it in moments of stress, and it induced self-control and self-confidence of a high order.

The same applies to the last slogan, The Answer to Noise is Silence. The Jap relies on noise. He shrieks when he goes into action; he fires shots at random when he thinks he is on to something suspicious. If he is answered by noise, he knows the most of what he wants to know: that somebody is there; whereabouts he is and his approximate strength. All this knowledge he has won for the price of a few rounds. If, on the other hand, he gets no answering cry or shot, he is either falsely reassured or thoroughly discomfited; if the latter, he has lost the moral initiative and the seeds of nervousness are sown in him. And again, he who answers with silence knows that he has given nothing away, and feels himself to be a Strong, as well as a Silent, Man. For the worst thing that can befall the commander of a small force in a jungle encounter is the loss of control. When indiscriminate shooting starts, you have begun to lose control; from there it is only a small step to losing moral and physical control of your force. When that disintegrates you are sunk; and soon you will be fighting other elements of your own men.

Bernard Fergusson, Wild Green Earth, 1946.

The 13th King's Last Leave in Bombay

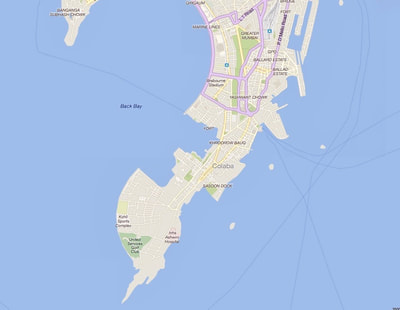

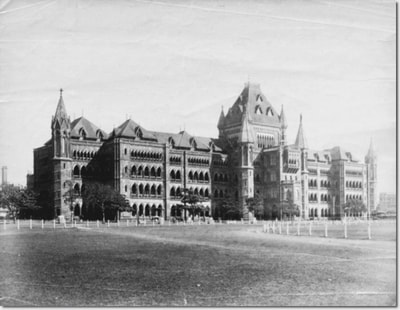

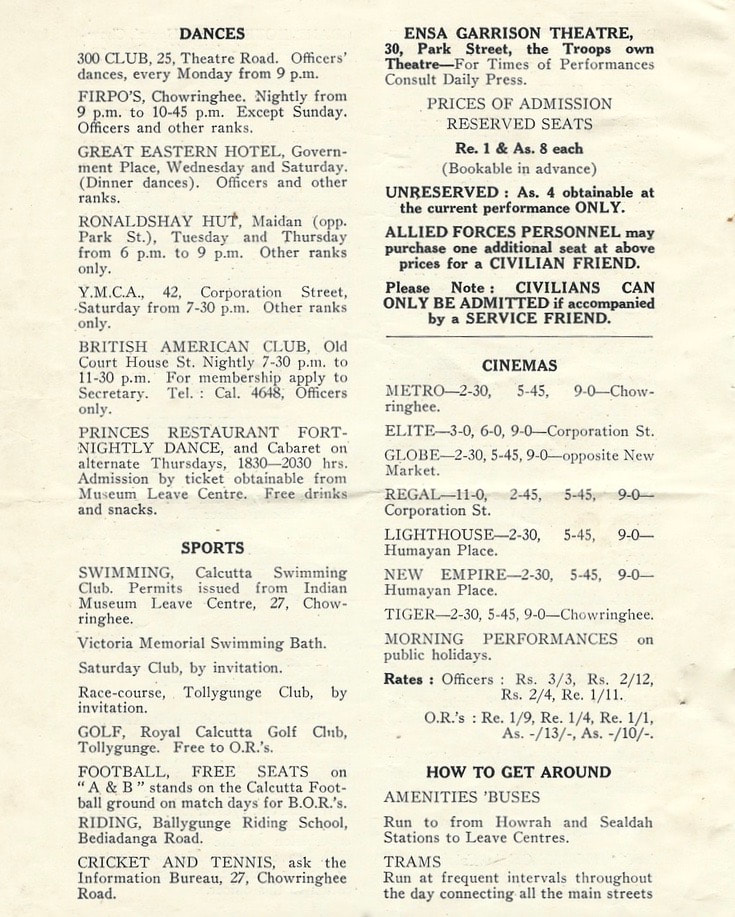

The Gateway Arch at Bombay was very often a British soldier’s first glimpse of the Indian mainland. More often than not, he would disembark his ship at a dock from amongst the many that comprised the Ballard Pier and almost immediately take the awaiting train transport to the centre of the city, or on occasion, be sent straight to the British Base Reinforcement Camp at Deolali, some 100 miles to the northeast.

Bombay would become the most visited city in India for British Other Ranks and officers, when away from their units on periods of leave or rest and recuperation. The city was chosen for its entertainment value; whether this be the many hotels and restaurants, its infamous night life and amusements, or the array of impressive Victorian buildings and architecture.

After the training period for Operation Longcloth came to an end, Bombay was the venue of choice for the vast majority of British Other Ranks, mostly men from the 13th King’s, to spend their final few days leave before beginning their march to the Chindwin River.

The Chindits last leave was staggered over a period beginning in mid-November 1942 and ending around the first week in January 1943. Sixty soldiers were released at any one time and arrangements had been made by the Battalion Adjutant, Captain David Hastings, for the men to stay at the Army Rest Camp at Colaba one of the seven islands that made up the Bombay peninsula. Unfortunately, these initial parties of Kingsmen did not behave too well at Colaba, or indeed during their perambulations throughout the city of Bombay.

From the Battalion War diary, dated 27th November 1942:

The latest draft of men have caused trouble in Bombay on their leave and a telegram was received today from the Area Commander in Bombay saying that he is not prepared to have any more of our men, unless discipline and uniform turn-out improves.

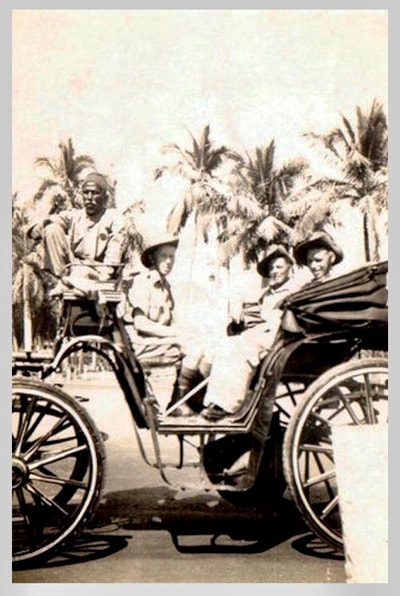

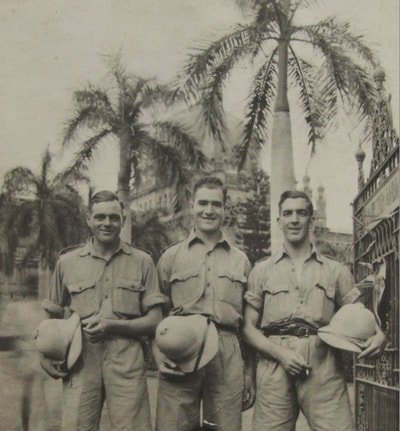

Behaviour must have improved, as over the next five weeks, most, if not all of the battalion enjoyed up to ten days leave in Bombay. Many of the Chindits used their time in Bombay to have photographs taken to send home to their families and loved ones. Some of these images can be viewed in the gallery below, along with other related images of Bombay from that time. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

To read a contemporary booklet in regards visiting Bombay which was prepared for the soldiers of the CBI theatre, please click on the following link: www.cbi-theater.com/bombay/bombay.html

The Gateway Arch at Bombay was very often a British soldier’s first glimpse of the Indian mainland. More often than not, he would disembark his ship at a dock from amongst the many that comprised the Ballard Pier and almost immediately take the awaiting train transport to the centre of the city, or on occasion, be sent straight to the British Base Reinforcement Camp at Deolali, some 100 miles to the northeast.

Bombay would become the most visited city in India for British Other Ranks and officers, when away from their units on periods of leave or rest and recuperation. The city was chosen for its entertainment value; whether this be the many hotels and restaurants, its infamous night life and amusements, or the array of impressive Victorian buildings and architecture.

After the training period for Operation Longcloth came to an end, Bombay was the venue of choice for the vast majority of British Other Ranks, mostly men from the 13th King’s, to spend their final few days leave before beginning their march to the Chindwin River.

The Chindits last leave was staggered over a period beginning in mid-November 1942 and ending around the first week in January 1943. Sixty soldiers were released at any one time and arrangements had been made by the Battalion Adjutant, Captain David Hastings, for the men to stay at the Army Rest Camp at Colaba one of the seven islands that made up the Bombay peninsula. Unfortunately, these initial parties of Kingsmen did not behave too well at Colaba, or indeed during their perambulations throughout the city of Bombay.

From the Battalion War diary, dated 27th November 1942:

The latest draft of men have caused trouble in Bombay on their leave and a telegram was received today from the Area Commander in Bombay saying that he is not prepared to have any more of our men, unless discipline and uniform turn-out improves.

Behaviour must have improved, as over the next five weeks, most, if not all of the battalion enjoyed up to ten days leave in Bombay. Many of the Chindits used their time in Bombay to have photographs taken to send home to their families and loved ones. Some of these images can be viewed in the gallery below, along with other related images of Bombay from that time. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

To read a contemporary booklet in regards visiting Bombay which was prepared for the soldiers of the CBI theatre, please click on the following link: www.cbi-theater.com/bombay/bombay.html