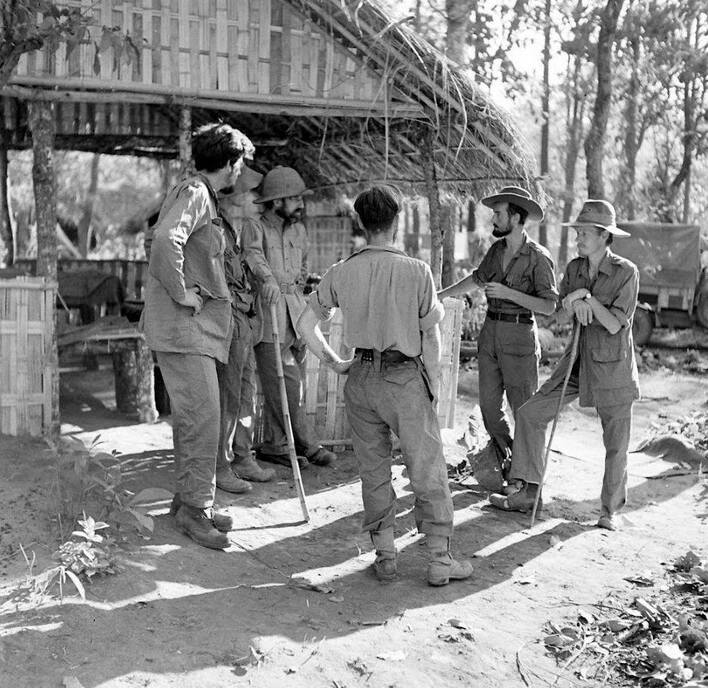

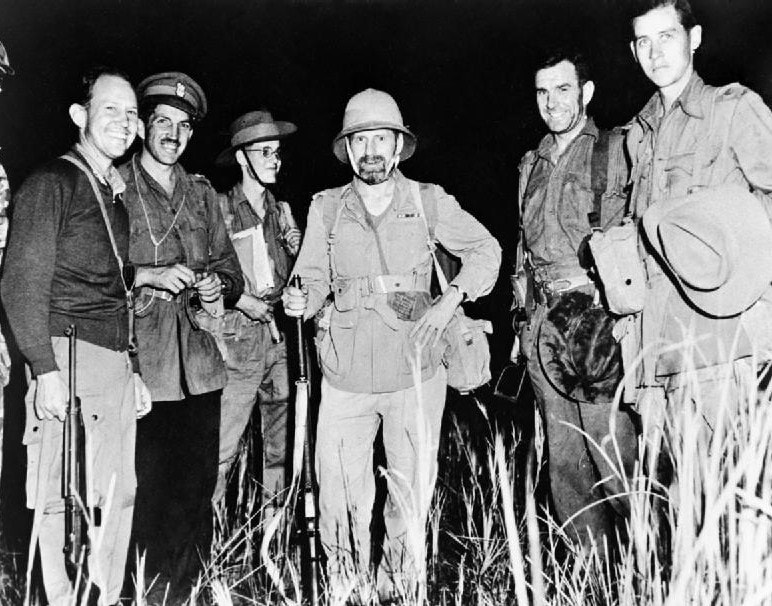

Wingate and his Column Commanders

Back in 2011, when I first published this website, it was my intention to concentrate my efforts in bringing the stories and eventual fate of the ordinary Chindit soldier to the public domain. After seven years of work and over 400 such narratives delivered, I feel it is time to devote some space here to the men who led the Longcloth columns in 1943. The following pages will cover, using a short biographical template, each individual Column Commander and his military career both before and after his Chindit experience.

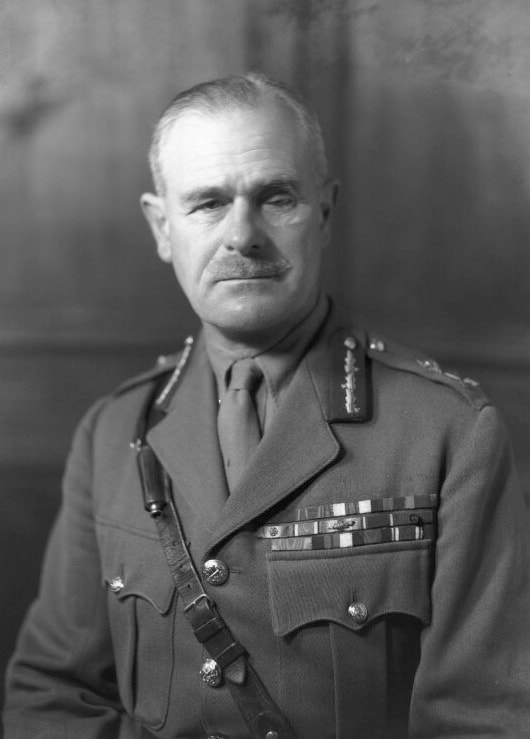

Major-General Orde Charles Wingate

Born on the 26th February 1903 in colonial India, Orde Charles Wingate is of course the man who devised and developed the theory of Long Range Penetration and brought together all these ideas in the creation of the Chindit phenomenon. Beginning his Army career as a young Subaltern with the Royal Artillery, he through endeavour and sometimes pure bloodymindedness pushed himself to the forefront of new military thinking, but rarely made friends along the way.

For a more thorough explanation of his time in the British Army, please click on the following link:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orde_Wingate

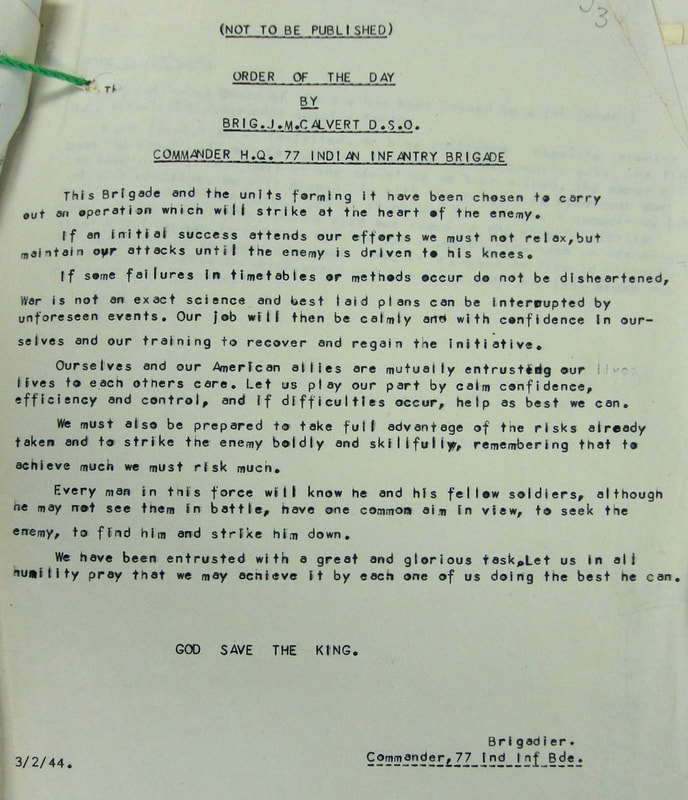

Wingate was not only the mastermind behind the concept of the Chindits in 1943, he also led his 3000 strong Brigade into Burma, controlling the seven columns from his Brigade HQ and adapting their role as the days and weeks passed by. For his efforts on Operation Longcloth, he was awarded a second bar to his DSO (Distinguished Service Order), having already received the award twice before, once for his time in Palestine in 1938 and again with Gideon Force in Ethiopia during 1941.

Transcript of Distinguished Service Order Citation for Operation Longcloth

Brigade-77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Corps- 4 Corps

Date of Recommendation-9th July 1943

Rank and Name-Brigadier Orde Charles Wingate D.S.O

Action for which recommended :-

Brigadier Wingate trained 77 Infantry Brigade and commanded it during the recent operations in Burma. Throughout the operation he displayed skill, personal courage and endurance of a high order. His determination and inspiring leadership were largely responsible for the success attained by what was definitely an arduous and dangerous undertaking. His ability and resolution gave great confidence to those under his command. It was noticeable that almost the first question asked by many officers and men on their return was for news of the Brigadier. Their relief at his safe return was most marked and was accompanied by spontaneous expressions of admiration for his courage and leadership. This attainment is reached by few. Brigadier Wingate has again proved himself to be a skilful and intrepid leader. His achievements during the recent operations were of a very high order and, in my opinion, merit immediate recognition.

Recommended By

Lieut-General Scoones, Commander, 4 Corps.

Honour or Reward-Second bar to D.S.O.

Signed By:

General Auchinleck

Commander-in-Chief India

London Gazette 05.08.1943

Born on the 26th February 1903 in colonial India, Orde Charles Wingate is of course the man who devised and developed the theory of Long Range Penetration and brought together all these ideas in the creation of the Chindit phenomenon. Beginning his Army career as a young Subaltern with the Royal Artillery, he through endeavour and sometimes pure bloodymindedness pushed himself to the forefront of new military thinking, but rarely made friends along the way.

For a more thorough explanation of his time in the British Army, please click on the following link:

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orde_Wingate

Wingate was not only the mastermind behind the concept of the Chindits in 1943, he also led his 3000 strong Brigade into Burma, controlling the seven columns from his Brigade HQ and adapting their role as the days and weeks passed by. For his efforts on Operation Longcloth, he was awarded a second bar to his DSO (Distinguished Service Order), having already received the award twice before, once for his time in Palestine in 1938 and again with Gideon Force in Ethiopia during 1941.

Transcript of Distinguished Service Order Citation for Operation Longcloth

Brigade-77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Corps- 4 Corps

Date of Recommendation-9th July 1943

Rank and Name-Brigadier Orde Charles Wingate D.S.O

Action for which recommended :-

Brigadier Wingate trained 77 Infantry Brigade and commanded it during the recent operations in Burma. Throughout the operation he displayed skill, personal courage and endurance of a high order. His determination and inspiring leadership were largely responsible for the success attained by what was definitely an arduous and dangerous undertaking. His ability and resolution gave great confidence to those under his command. It was noticeable that almost the first question asked by many officers and men on their return was for news of the Brigadier. Their relief at his safe return was most marked and was accompanied by spontaneous expressions of admiration for his courage and leadership. This attainment is reached by few. Brigadier Wingate has again proved himself to be a skilful and intrepid leader. His achievements during the recent operations were of a very high order and, in my opinion, merit immediate recognition.

Recommended By

Lieut-General Scoones, Commander, 4 Corps.

Honour or Reward-Second bar to D.S.O.

Signed By:

General Auchinleck

Commander-in-Chief India

London Gazette 05.08.1943

Although Operation Longcloth was perceived by the military as having achieved very little in regards the disruption of the Japanese war machine, it did offer a wonderful propaganda opportunity for the Allied leadership and had gone some way in dispelling the myth that the Japanese soldier was invincible in the jungles of South East Asia. From the acorn of Operation Longcloth, a full six brigade strength Chindit expedition was constructed for the following year, codenamed Operation Thursday.

To read more about Operation Thursday, please click on the following link: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chindits#Operation_Thursday

Tragically, Major-General Wingate was killed during the second Chindit expedition, when the B-25 Mitchell Bomber he was travelling in crashed into the hills of Assam on the 24th March 1944. Sadly, he did not live to see his plans and aspirations for Operation Thursday come to fruition, or continue to be the driving force behind his Chindit Brigades as they tackled the implementation of his ideas.

Many books and other writings have been penned around the subject of the Chindits and of course Wingate in particular. These include several biographies about the man himself:

Orde Wingate, by Christopher Sykes.

Wingate, in Peace and War, by Derek Tulloch.

There was a Man of Genius, by Alice Ivy Hay.

Fire in the Night, John Bierman and Colin Smith.

Orde Wingate, Unconventional Warrior, by Simon Anglim.

I thought it might be of interest as part of this review, to read what Orde Wingate thought about the enemy he faced across the tight-set jungles of Burma in 1943-44. From the operational debrief, written after his return from Burma in April 1943:

The Japanese thought they had found a technique of warfare in the jungles of the Far East to which the United Nations had no answer. With characteristic thoroughness and assiduity, they had not only studied the effects of jungle on all types of modern tactics, but had also trained large numbers of their best troops in the practical application of their approved methods. They boasted that the self-indulgent, ignorant troops of the United Nations could never equal them, either in skill or endurance, in the conditions of warfare that prevailed throughout their co-prosperity sphere.

From Japan to India, from Manchuria to Australasia, jungle and mountain predominate and make penetration, the premier weapon in modern warfare, everywhere possible. The Japanese were mistaken. The British soldier has shown that he can not only equal the Japanese, but surpass him in this very war of penetration in jungle. The reason is to be found in the qualities he shares with his ancestors: imagination, the ability to give of his best when the audience is smallest, self-reliance, and power of individual action. The Indian soldier, too, has shown himself fully capable of beating the Japanese in jungle fighting, where individuality and personal initiative are the qualities that count.

Believing that this was so, Field-Marshal Wavell gave me the task of raising and training a formation designed to carry out penetration of the enemy's back areas far deeper and on a far larger scale than anything the Japanese had practised against us. Essential to Wavell's plan was air power not only superior to that of the enemy but capable of operating in new ways, of fulfilling hitherto unheard-of demands. We had such air resources. The R.A.F. never failed us. In fact, seeing in us the ideal opportunity of driving home their own strategic attacks on the enemy, they supplied R.A.F. contingents for every column. And it was largely the presence and work of these R.A.F. elements that made the operation a success.

The force that was to go into the heart of Japanese-occupied Burma and singe the Mikado's beard was not composed of selected troops; it consisted of ordinary British and Indian infantry, sappers, signalmen, and others. Each column also had its quota of Burmese troops; without the brave and devoted Burma Rifles the operation would have been impossible. What was it that made these ordinary troops, born and bred for the most part to factories and workshops, capable of feats that would not have disgraced Commandos? The answer is that given imagination and individuality in sufficient quantities, the necessary minimum of training will always produce junior leaders and men capable of beating the unimaginative and stereotyped soldiers of the Axis. Remember, too, that all over this theatre of war human beings feel that the United Nations are fighting for something that means more than the severe and macabre ideals of the Axis.

The Jap is no superman. His operational schemes are the product of a third-rate brain. But the individual soldiers are fanatics. Put one of them in a hole with a hundred rounds of ammunition and tell him to die for the Emperor—and he will do it. The way to deal with him is to leave him in his hole and go behind him. Jungle warfare places a great demand for resourcefulness and endurance on the individual, who may be cut off from his comrades at any time. The Jap is not resourceful. He is assiduous, hard-working, courageous, and possesses tremendous energy, but he can't solve problems which he has never faced before. The city-bred. Englishman, given the right kind of training, meets new and unexpected conditions with imagination and originality.

Although not given to the humourless self-immolation of the Japanese, he has a stronger, saner heroism. Most of us are waiting to renew our experience of this dull, ferocious, and poverty-stricken little enemy at the earliest possible moment. Some of us did not come back. They have done some-thing for their country. They have demonstrated a new kind of warfare—the combination of the oldest with the newest methods. They have not been thrown away. We have proved that we can beat the Jap on his own chosen ground. And as here, so will it be elsewhere.

To read more about Operation Thursday, please click on the following link: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chindits#Operation_Thursday

Tragically, Major-General Wingate was killed during the second Chindit expedition, when the B-25 Mitchell Bomber he was travelling in crashed into the hills of Assam on the 24th March 1944. Sadly, he did not live to see his plans and aspirations for Operation Thursday come to fruition, or continue to be the driving force behind his Chindit Brigades as they tackled the implementation of his ideas.

Many books and other writings have been penned around the subject of the Chindits and of course Wingate in particular. These include several biographies about the man himself:

Orde Wingate, by Christopher Sykes.

Wingate, in Peace and War, by Derek Tulloch.

There was a Man of Genius, by Alice Ivy Hay.

Fire in the Night, John Bierman and Colin Smith.

Orde Wingate, Unconventional Warrior, by Simon Anglim.

I thought it might be of interest as part of this review, to read what Orde Wingate thought about the enemy he faced across the tight-set jungles of Burma in 1943-44. From the operational debrief, written after his return from Burma in April 1943:

The Japanese thought they had found a technique of warfare in the jungles of the Far East to which the United Nations had no answer. With characteristic thoroughness and assiduity, they had not only studied the effects of jungle on all types of modern tactics, but had also trained large numbers of their best troops in the practical application of their approved methods. They boasted that the self-indulgent, ignorant troops of the United Nations could never equal them, either in skill or endurance, in the conditions of warfare that prevailed throughout their co-prosperity sphere.

From Japan to India, from Manchuria to Australasia, jungle and mountain predominate and make penetration, the premier weapon in modern warfare, everywhere possible. The Japanese were mistaken. The British soldier has shown that he can not only equal the Japanese, but surpass him in this very war of penetration in jungle. The reason is to be found in the qualities he shares with his ancestors: imagination, the ability to give of his best when the audience is smallest, self-reliance, and power of individual action. The Indian soldier, too, has shown himself fully capable of beating the Japanese in jungle fighting, where individuality and personal initiative are the qualities that count.

Believing that this was so, Field-Marshal Wavell gave me the task of raising and training a formation designed to carry out penetration of the enemy's back areas far deeper and on a far larger scale than anything the Japanese had practised against us. Essential to Wavell's plan was air power not only superior to that of the enemy but capable of operating in new ways, of fulfilling hitherto unheard-of demands. We had such air resources. The R.A.F. never failed us. In fact, seeing in us the ideal opportunity of driving home their own strategic attacks on the enemy, they supplied R.A.F. contingents for every column. And it was largely the presence and work of these R.A.F. elements that made the operation a success.

The force that was to go into the heart of Japanese-occupied Burma and singe the Mikado's beard was not composed of selected troops; it consisted of ordinary British and Indian infantry, sappers, signalmen, and others. Each column also had its quota of Burmese troops; without the brave and devoted Burma Rifles the operation would have been impossible. What was it that made these ordinary troops, born and bred for the most part to factories and workshops, capable of feats that would not have disgraced Commandos? The answer is that given imagination and individuality in sufficient quantities, the necessary minimum of training will always produce junior leaders and men capable of beating the unimaginative and stereotyped soldiers of the Axis. Remember, too, that all over this theatre of war human beings feel that the United Nations are fighting for something that means more than the severe and macabre ideals of the Axis.

The Jap is no superman. His operational schemes are the product of a third-rate brain. But the individual soldiers are fanatics. Put one of them in a hole with a hundred rounds of ammunition and tell him to die for the Emperor—and he will do it. The way to deal with him is to leave him in his hole and go behind him. Jungle warfare places a great demand for resourcefulness and endurance on the individual, who may be cut off from his comrades at any time. The Jap is not resourceful. He is assiduous, hard-working, courageous, and possesses tremendous energy, but he can't solve problems which he has never faced before. The city-bred. Englishman, given the right kind of training, meets new and unexpected conditions with imagination and originality.

Although not given to the humourless self-immolation of the Japanese, he has a stronger, saner heroism. Most of us are waiting to renew our experience of this dull, ferocious, and poverty-stricken little enemy at the earliest possible moment. Some of us did not come back. They have done some-thing for their country. They have demonstrated a new kind of warfare—the combination of the oldest with the newest methods. They have not been thrown away. We have proved that we can beat the Jap on his own chosen ground. And as here, so will it be elsewhere.

In the period leading up to Christmas 1942 the final finishing touches were being made to the first Chindit Brigade. Last minute reinforcements were arriving from all over India to bolster column numbers and the last of the mules were being allocated to the Chindit groups still without their animals.

On the 9th December all columns had been involved in a full field exercise. This included a three day route march up to the rail station at Jhansi, where certain columns were pitched against each other, some defending and some attacking the station buildings. Wingate was not overly impressed by the Chindits performance at Jhansi and so another full Brigade exercise was arranged for late December. It was at this juncture that the officers of 77th Indian Infantry Brigade were issued with Wingate's orders for the forthcoming operation.

Here for your interest, is the twenty point list given to all column officers by Wingate on the 29th December 1942. Some of the younger officers present were shocked by some of Wingate's ideas and the language used in the document, if they had not already guessed previously, they now knew that they were in for a tough and uncompromising time once inside Burma.

Secret (29 Dec. 1942).

77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Maxims for all Officers

1.The Chindwin is your Jordan, once crossed there is no re-crossing. The exit from Burma is via Rangoon.

2. Success in operations depends on the perfecting of an exact and well conducted drill for every procedure.

3. Our reply to noise is silence.

4. When in doubt do not fire.

5. Never await the enemy's blow, evade it.

6. Fight when surprise has been gained. When surprise is lost at the outset, break off the action and come again.

7. Security is gained by intelligence, good dispersal procedure and counter attack. Thus all depends on good 'guerilla' procedure plus careful drill. Read and then re-read "Security in bivouac".

8. Always maintain a margin of strength for a time of need. It is the reserve of energy that saves from disaster, that gives the weight required for victory.

9. Avoid defiles. If you must use them, secure your flanks first. Pass by night whenever possible. For us, a defile may be defined as a track from which dispersal is not possible owing to physical obstacles.

10. Times of darkness, of rain, mist and storm, these are our times of achievement.

11. Never retrace your steps.

12. The movement of the column must be unpredictable, even for it's own members.

13. Never bivouac within three miles of a motor road or waterway. Three miles of good forest will give the same protection as ten miles of open country.

14. Use your W/T (radio) to capacity, it is your greatest weapon.

15. Use every weapon and every man to capacity. It is their combined and simultaneous employment that gives strength. Work together and rest together.

16. Festina lente (make haste slowly). Let your haste be a considered haste, the fitting end to a leisurely examination and preparation. Speed should be the result, not of fear and confusion, but of superior knowledge, planning and drill.

17. Intelligence is useless unless it passed on. Use your W/T.

18. See that your men think the same of the situation as you do. For this, constant talks and explanations will be necessary.

19. Get rid of casualties, never keep serious cases with the Column.

20. Spend your cash.

Signed Orde C. Wingate (Brigadier Commander 77 Ind. Inf. Brigade).

On the 9th December all columns had been involved in a full field exercise. This included a three day route march up to the rail station at Jhansi, where certain columns were pitched against each other, some defending and some attacking the station buildings. Wingate was not overly impressed by the Chindits performance at Jhansi and so another full Brigade exercise was arranged for late December. It was at this juncture that the officers of 77th Indian Infantry Brigade were issued with Wingate's orders for the forthcoming operation.

Here for your interest, is the twenty point list given to all column officers by Wingate on the 29th December 1942. Some of the younger officers present were shocked by some of Wingate's ideas and the language used in the document, if they had not already guessed previously, they now knew that they were in for a tough and uncompromising time once inside Burma.

Secret (29 Dec. 1942).

77th Indian Infantry Brigade

Maxims for all Officers

1.The Chindwin is your Jordan, once crossed there is no re-crossing. The exit from Burma is via Rangoon.

2. Success in operations depends on the perfecting of an exact and well conducted drill for every procedure.

3. Our reply to noise is silence.

4. When in doubt do not fire.

5. Never await the enemy's blow, evade it.

6. Fight when surprise has been gained. When surprise is lost at the outset, break off the action and come again.

7. Security is gained by intelligence, good dispersal procedure and counter attack. Thus all depends on good 'guerilla' procedure plus careful drill. Read and then re-read "Security in bivouac".

8. Always maintain a margin of strength for a time of need. It is the reserve of energy that saves from disaster, that gives the weight required for victory.

9. Avoid defiles. If you must use them, secure your flanks first. Pass by night whenever possible. For us, a defile may be defined as a track from which dispersal is not possible owing to physical obstacles.

10. Times of darkness, of rain, mist and storm, these are our times of achievement.

11. Never retrace your steps.

12. The movement of the column must be unpredictable, even for it's own members.

13. Never bivouac within three miles of a motor road or waterway. Three miles of good forest will give the same protection as ten miles of open country.

14. Use your W/T (radio) to capacity, it is your greatest weapon.

15. Use every weapon and every man to capacity. It is their combined and simultaneous employment that gives strength. Work together and rest together.

16. Festina lente (make haste slowly). Let your haste be a considered haste, the fitting end to a leisurely examination and preparation. Speed should be the result, not of fear and confusion, but of superior knowledge, planning and drill.

17. Intelligence is useless unless it passed on. Use your W/T.

18. See that your men think the same of the situation as you do. For this, constant talks and explanations will be necessary.

19. Get rid of casualties, never keep serious cases with the Column.

20. Spend your cash.

Signed Orde C. Wingate (Brigadier Commander 77 Ind. Inf. Brigade).

I am deeply grieved at the loss of this man of genius, who might have become a man of destiny.

Winston Churchill 30th March 1944.

Winston Churchill 30th March 1944.

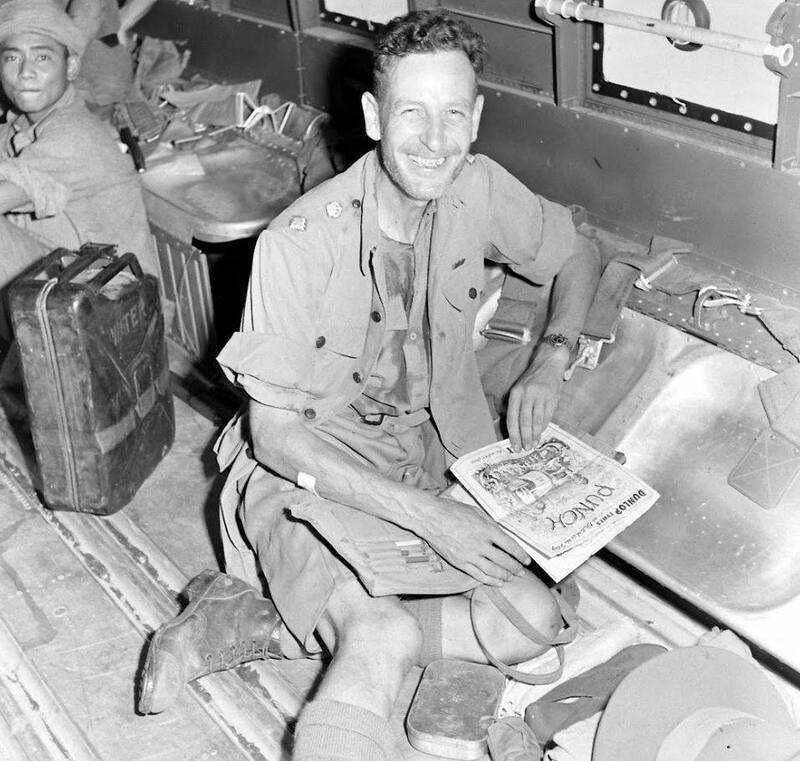

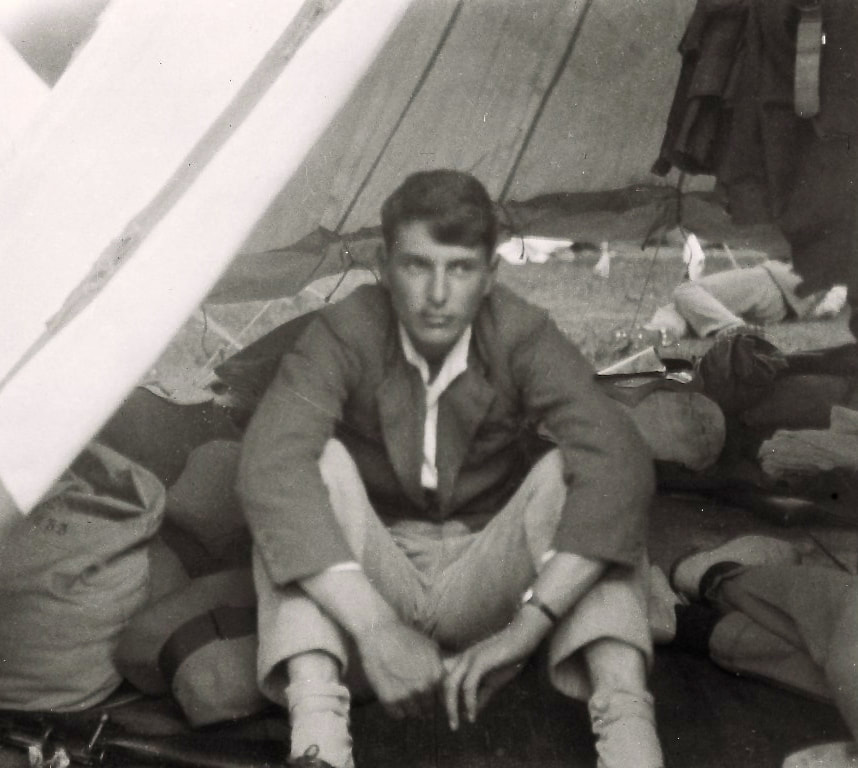

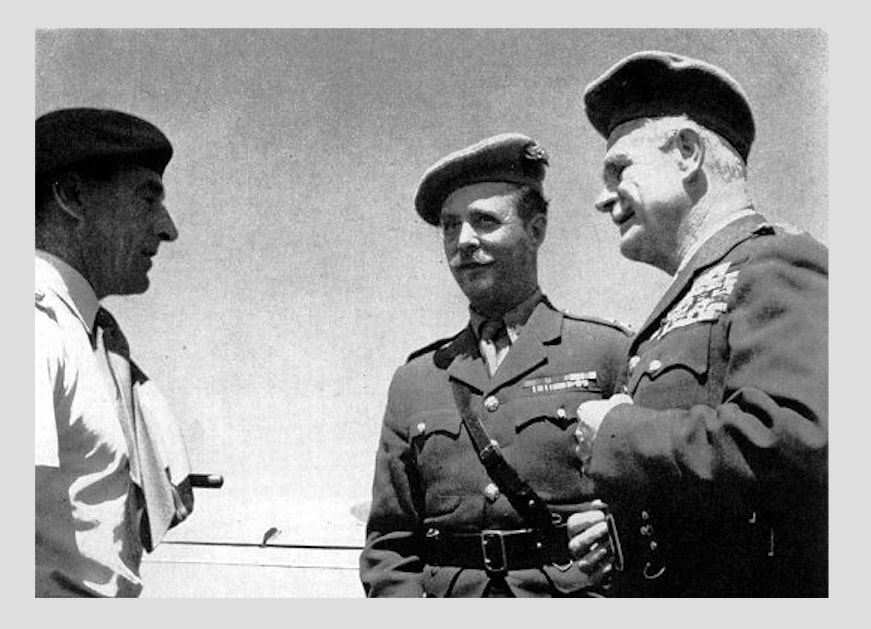

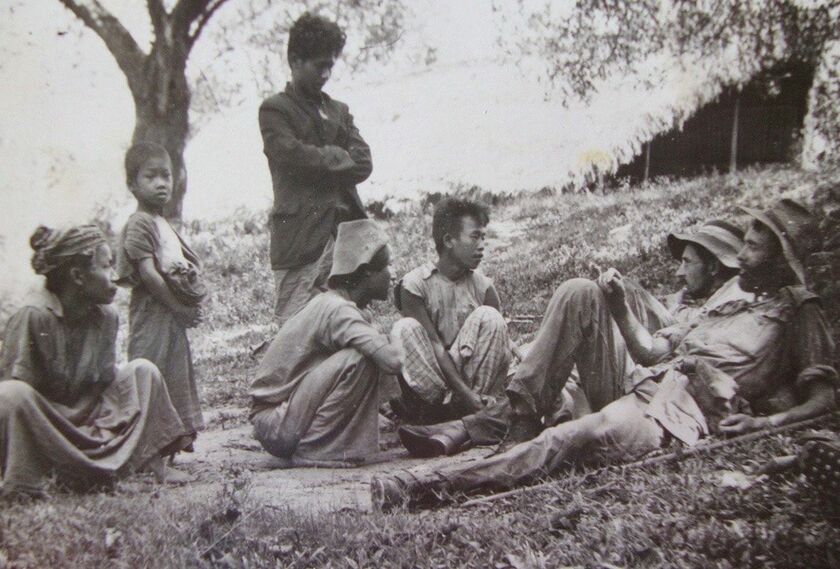

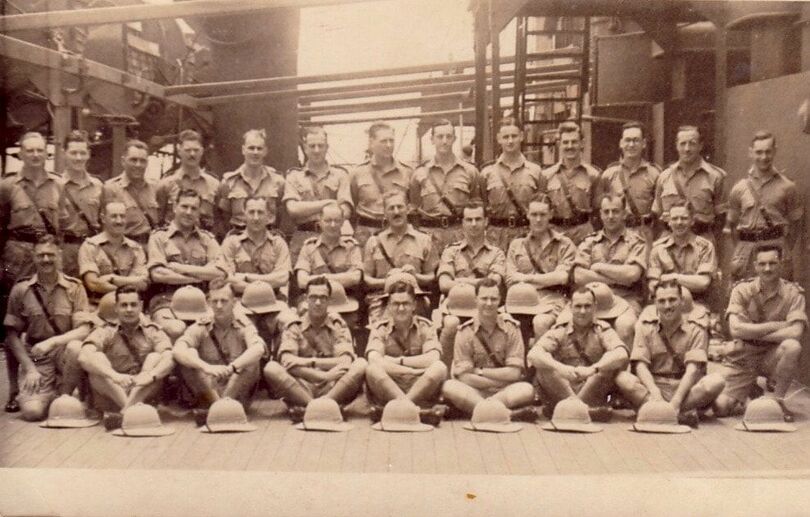

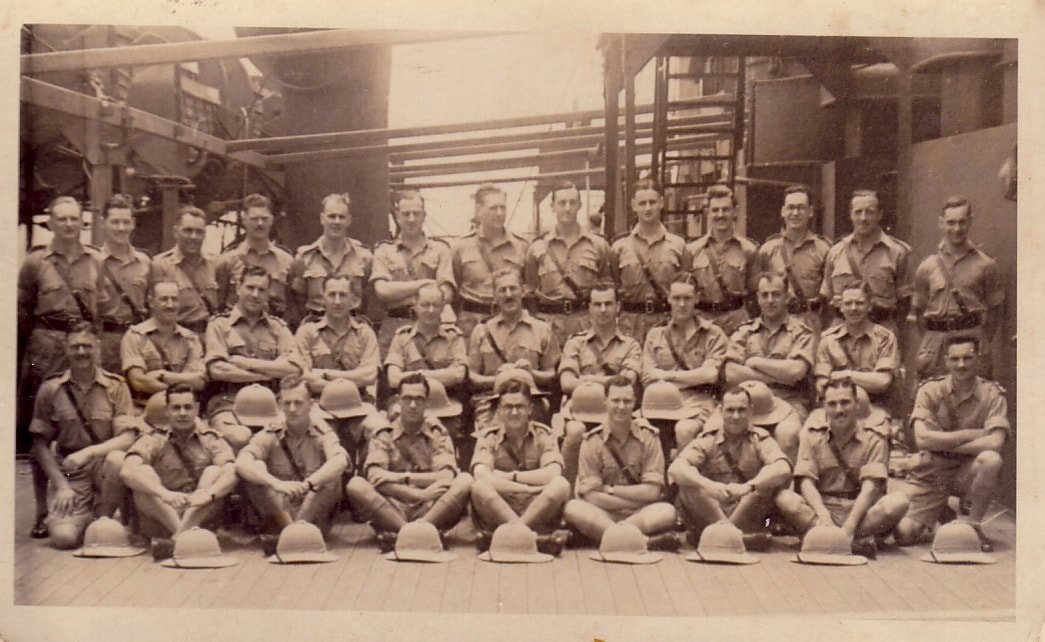

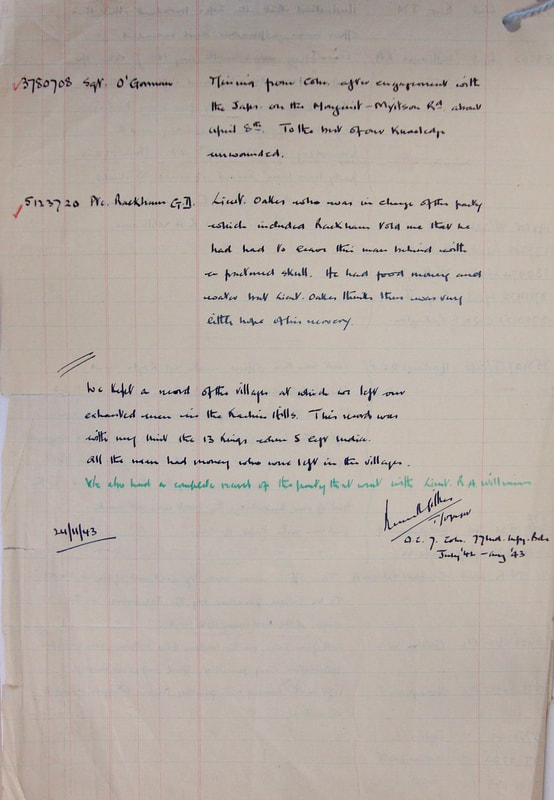

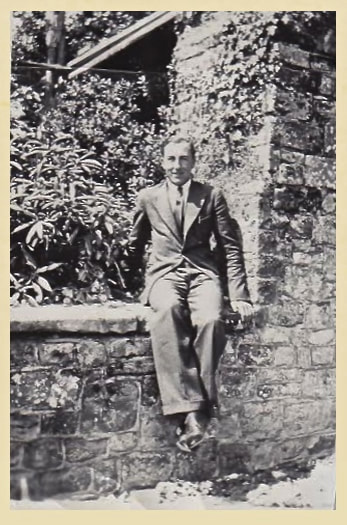

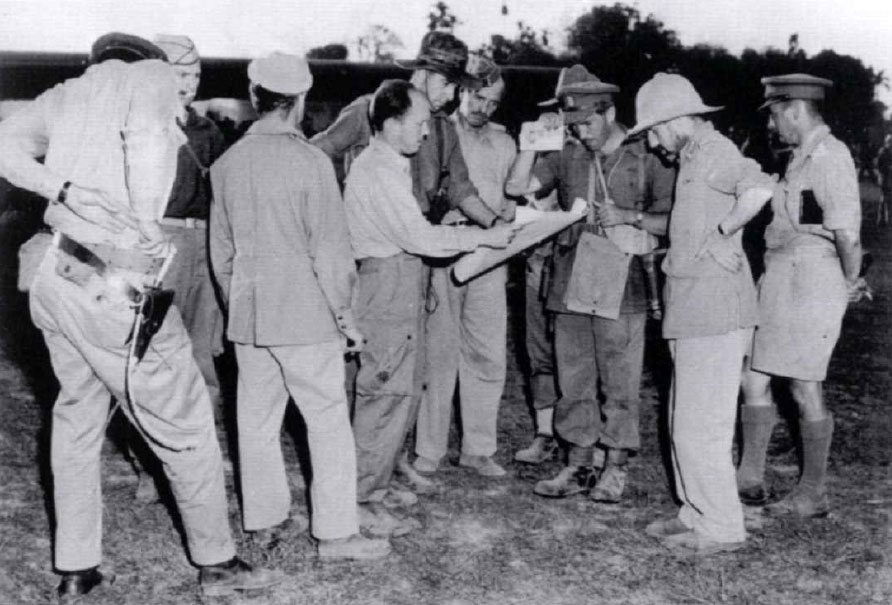

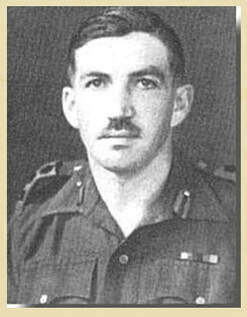

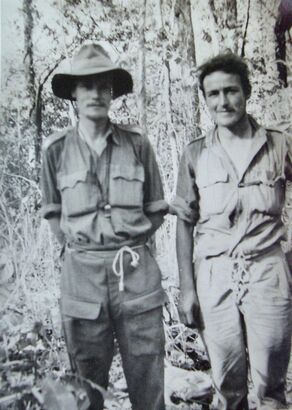

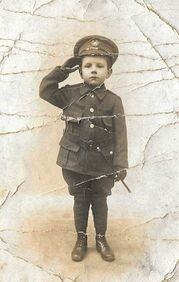

Colonel Cooke in April 1943.

Colonel Cooke in April 1943.

Lt-Colonel Sidney Arthur Cooke

Colonel Cooke became the Commanding Officer of the 13th King's on the 3rd November 1942 while the battalion were completing their Chindit training at the Atta Camp in the Central Provinces of India. Cooke replaced Lt-Colonel William Moncrieff Robinson, who had been the battalion's C/O from October 1940 and had led the 13th King's during their voyage to India in late 1941 and throughout the units early months on the sub-continent.

Sidney Arthur Cooke, known to his closest Army comrades as Sam, was formerly with the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Lincolnshire Regiment and had served with this unit in Palestine as part of the British Garrison at Aqaba. After taking up his duties as senior officer with the 13th King's, Cooke formed an excellent relationship with Brigadier Wingate and was given command of Northern Group Head Quarters (Chindit columns 4, 5, 7 and 8) during Operation Longcloth.

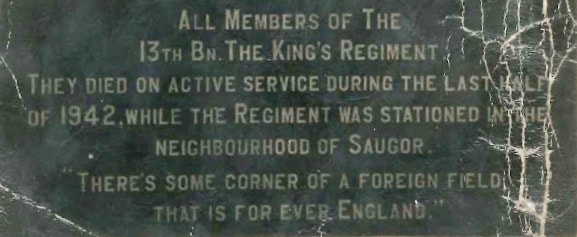

Sadly, not all duties that befell Colonel Cooke were directly to do with training and combat. After the unfortunate death of Pte. Ronald Braithwaite during a training accident in late 1942, Cooke felt obliged to send the following letter to Pte. Braithwaite's wife:

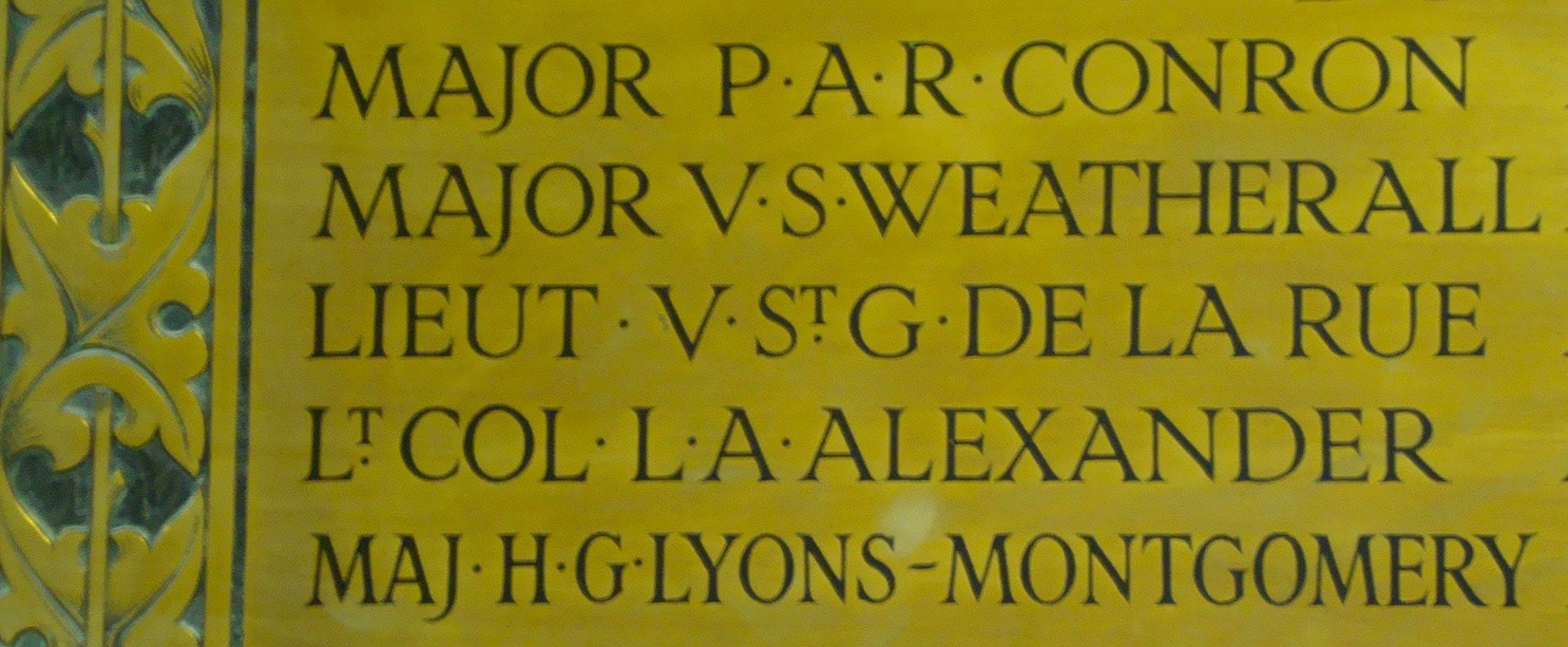

Dear Mrs. Braithwaite,

I am sending you a photograph of a Memorial tablet which has been placed in the Garrison Church at Saugor and which includes the name of your husband, Ronald Braithwaite. The memorial is a small token of the high regard both officers and men had for your husband, and I hope that you will accept this photograph in the sentiment with which it is being sent.

Yours most sincerely, S.A. Cooke

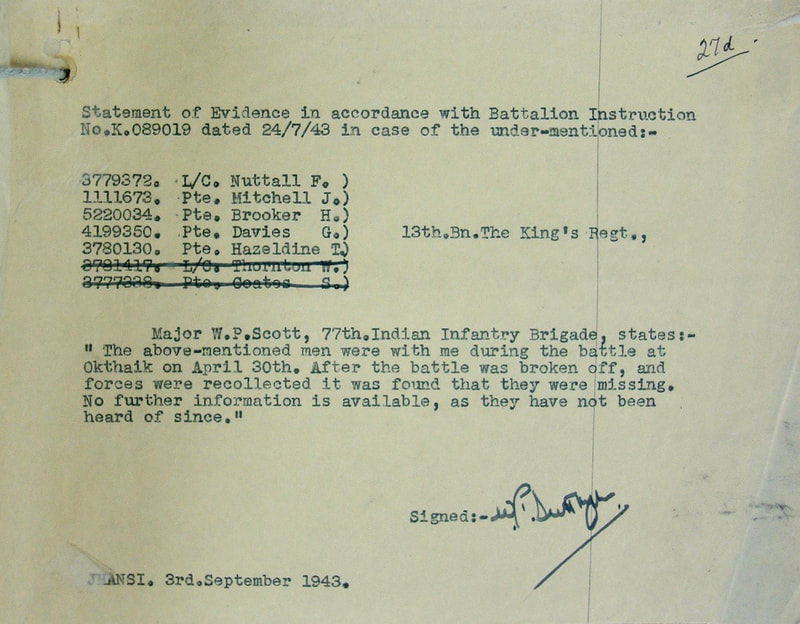

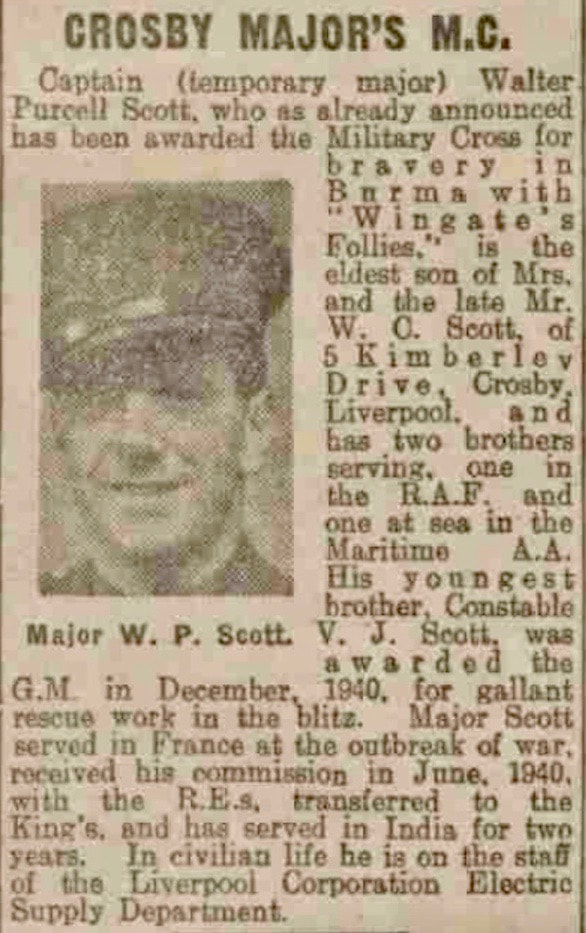

Colonel Cooke performed well in Burma, leading his men with skill and determination during the first weeks of the expedition. His one great talent was in the choosing, setting up and then defending supply drop locations. In his debrief in June 1943, Brigadier Wingate remarks on Cooke's excellent performance in arranging these locations, known as SDZ's on Operation Longcloth. On the 13th March 1943, at a drop zone area close to the Burmese village of Kyunbin, Colonel Cooke assumed total command of the location which included having to beat off a determined Japanese attack whilst the supply drop was actually taking place. On the 24th March, the same thing happened during an extensive supply dropping on the outskirts of a village called Baw. Once again, Cooke, this time in conjunction with No. 8 Column, commanded by Major Scott of the King's Regiment dealt effectively with the enemy interference.

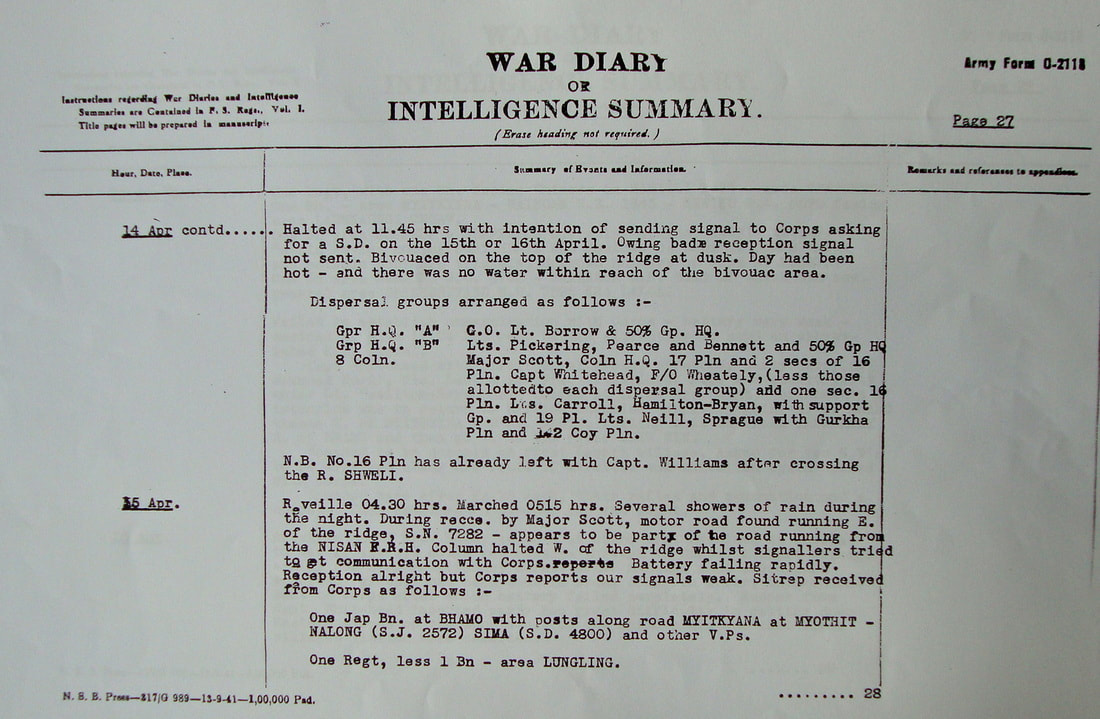

As the expedition unfolded, Colonel Cooke formed what was to become a life-long friendship with Major Scott and on dispersal both men decided to march back to India together. The two officers attempted to keep their units as one group on the return journey with Cooke and Scott sharing the responsibility of command. This arrangement worked well for a few weeks, but as rations and supplies ran low and after several minor skirmishes with the Japanese, Scott and Cooke decided to break up their group into smaller dispersal parties in order to maximise the mens chances of survival.

Sadly, the exertions of the expedition began to tell on Colonel Cooke and by the 24th April, he was struggling to continue whilst suffering with severe dysentery and acute jungle sores. Not long after this time, Major Scott's dispersal group which still included Colonel Cooke stumbled upon a large meadow in the middle of the previously dense jungle. An idea came to Scott, that perhaps a Dakota could land on this area and rescue the worst of his casualties and fly them back to India. This episode became known as the Piccadilly incident and would be remembered as one of the most iconic stories within Chindit circles for many years to come.

In the end, seventeen injured and sick Chindits were flown out of Burma from the meadow near Sonpu village, amongst these very fortunate passengers was Colonel Cooke. Although Colonel Cooke had insisted that he remain with his men, Major Scott realised the importance of not losing the commanding officer of the King's on the first expedition and over-ruled his commander, placing him reluctantly aboard the plane on the 28th April 1943. To read more about this incident, please click on the following link: The Piccadilly Incident

For his efforts on the first Wingate expedition, Colonel Cooke was awarded the OBE and received this decoration during a ceremony at Napier Barracks in Karachi on the 13th March 1944, the medal was presented by Lord Wavell who was the Viceroy of India at that time.

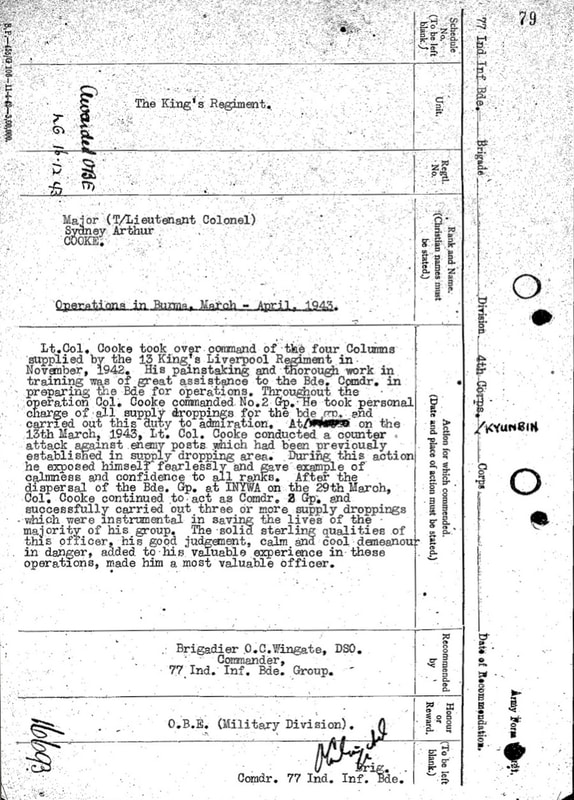

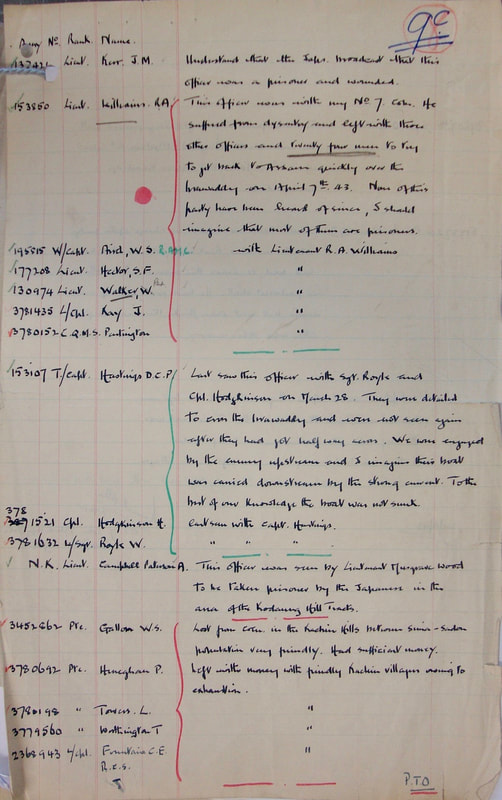

Operations in Burma March-April 1943

Colonel Cooke took over command of the four columns supplied by the 13th King's Liverpool Regiment in November 1942. His painstaking and thorough work in training was of great assistance to the Brigade Commander in preparing the Brigade for operations. Throughout the expedition, Cooke commanded No. 2 Group. He took personal charge of all supply droppings for the Brigade Group and carried out this duty to admiration.

At Kyunbin on the 13th March 1943, he conducted a counter attack against enemy posts which had been previously established in the supply dropping area. During this action he exposed himself fearlessly and gave a great example of calmness and confidence to all ranks. After the dispersal of the Brigade at Inywa on the 29th March, Cooke continued to act as Commander of No. 2 Group and successfully carried out three or more supply droppings which were instrumental in saving the lives of the majority of his group.

The solid sterling qualities of this officer, his good judgement, calm and cool demeanour in facing danger added to his valuable experience in these operations, made him a most valuable officer.

Award-OBE (Military Division).

Recommended by- Brigadier O.C. Wingate DSO. Commander 77 Indian Infantry Brigade.

London Gazette-16th December 1943.

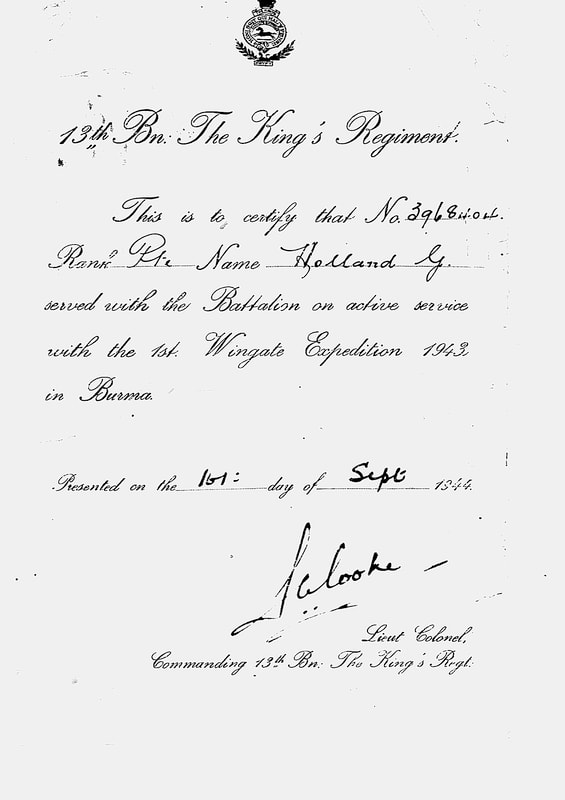

After returning to India in late April 1943, Colonel Cooke took on the responsibility of recording the adventures of No. 2 Group and No. 8 Column, writing out both units respective war diaries. With his strong involvement in the arrangement of the Brigade's supply drops, he took the time to officially congratulate and thank 31 Squadron RAF, for their invaluable and on occasions life-saving work in feeding the Chindits from the sky. In the years after Operation Longcloth, Colonel Cooke made the effort to recognise all the men who had served under him in 1943, issuing each man with a certificate confirming his participation on the first Wingate expedition.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this narrative, including an example of the above mentioned certificate and the original recommendation for the award of the OBE. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Colonel Cooke became the Commanding Officer of the 13th King's on the 3rd November 1942 while the battalion were completing their Chindit training at the Atta Camp in the Central Provinces of India. Cooke replaced Lt-Colonel William Moncrieff Robinson, who had been the battalion's C/O from October 1940 and had led the 13th King's during their voyage to India in late 1941 and throughout the units early months on the sub-continent.

Sidney Arthur Cooke, known to his closest Army comrades as Sam, was formerly with the 2nd Battalion, the Royal Lincolnshire Regiment and had served with this unit in Palestine as part of the British Garrison at Aqaba. After taking up his duties as senior officer with the 13th King's, Cooke formed an excellent relationship with Brigadier Wingate and was given command of Northern Group Head Quarters (Chindit columns 4, 5, 7 and 8) during Operation Longcloth.

Sadly, not all duties that befell Colonel Cooke were directly to do with training and combat. After the unfortunate death of Pte. Ronald Braithwaite during a training accident in late 1942, Cooke felt obliged to send the following letter to Pte. Braithwaite's wife:

Dear Mrs. Braithwaite,

I am sending you a photograph of a Memorial tablet which has been placed in the Garrison Church at Saugor and which includes the name of your husband, Ronald Braithwaite. The memorial is a small token of the high regard both officers and men had for your husband, and I hope that you will accept this photograph in the sentiment with which it is being sent.

Yours most sincerely, S.A. Cooke

Colonel Cooke performed well in Burma, leading his men with skill and determination during the first weeks of the expedition. His one great talent was in the choosing, setting up and then defending supply drop locations. In his debrief in June 1943, Brigadier Wingate remarks on Cooke's excellent performance in arranging these locations, known as SDZ's on Operation Longcloth. On the 13th March 1943, at a drop zone area close to the Burmese village of Kyunbin, Colonel Cooke assumed total command of the location which included having to beat off a determined Japanese attack whilst the supply drop was actually taking place. On the 24th March, the same thing happened during an extensive supply dropping on the outskirts of a village called Baw. Once again, Cooke, this time in conjunction with No. 8 Column, commanded by Major Scott of the King's Regiment dealt effectively with the enemy interference.

As the expedition unfolded, Colonel Cooke formed what was to become a life-long friendship with Major Scott and on dispersal both men decided to march back to India together. The two officers attempted to keep their units as one group on the return journey with Cooke and Scott sharing the responsibility of command. This arrangement worked well for a few weeks, but as rations and supplies ran low and after several minor skirmishes with the Japanese, Scott and Cooke decided to break up their group into smaller dispersal parties in order to maximise the mens chances of survival.

Sadly, the exertions of the expedition began to tell on Colonel Cooke and by the 24th April, he was struggling to continue whilst suffering with severe dysentery and acute jungle sores. Not long after this time, Major Scott's dispersal group which still included Colonel Cooke stumbled upon a large meadow in the middle of the previously dense jungle. An idea came to Scott, that perhaps a Dakota could land on this area and rescue the worst of his casualties and fly them back to India. This episode became known as the Piccadilly incident and would be remembered as one of the most iconic stories within Chindit circles for many years to come.

In the end, seventeen injured and sick Chindits were flown out of Burma from the meadow near Sonpu village, amongst these very fortunate passengers was Colonel Cooke. Although Colonel Cooke had insisted that he remain with his men, Major Scott realised the importance of not losing the commanding officer of the King's on the first expedition and over-ruled his commander, placing him reluctantly aboard the plane on the 28th April 1943. To read more about this incident, please click on the following link: The Piccadilly Incident

For his efforts on the first Wingate expedition, Colonel Cooke was awarded the OBE and received this decoration during a ceremony at Napier Barracks in Karachi on the 13th March 1944, the medal was presented by Lord Wavell who was the Viceroy of India at that time.

Operations in Burma March-April 1943

Colonel Cooke took over command of the four columns supplied by the 13th King's Liverpool Regiment in November 1942. His painstaking and thorough work in training was of great assistance to the Brigade Commander in preparing the Brigade for operations. Throughout the expedition, Cooke commanded No. 2 Group. He took personal charge of all supply droppings for the Brigade Group and carried out this duty to admiration.

At Kyunbin on the 13th March 1943, he conducted a counter attack against enemy posts which had been previously established in the supply dropping area. During this action he exposed himself fearlessly and gave a great example of calmness and confidence to all ranks. After the dispersal of the Brigade at Inywa on the 29th March, Cooke continued to act as Commander of No. 2 Group and successfully carried out three or more supply droppings which were instrumental in saving the lives of the majority of his group.

The solid sterling qualities of this officer, his good judgement, calm and cool demeanour in facing danger added to his valuable experience in these operations, made him a most valuable officer.

Award-OBE (Military Division).

Recommended by- Brigadier O.C. Wingate DSO. Commander 77 Indian Infantry Brigade.

London Gazette-16th December 1943.

After returning to India in late April 1943, Colonel Cooke took on the responsibility of recording the adventures of No. 2 Group and No. 8 Column, writing out both units respective war diaries. With his strong involvement in the arrangement of the Brigade's supply drops, he took the time to officially congratulate and thank 31 Squadron RAF, for their invaluable and on occasions life-saving work in feeding the Chindits from the sky. In the years after Operation Longcloth, Colonel Cooke made the effort to recognise all the men who had served under him in 1943, issuing each man with a certificate confirming his participation on the first Wingate expedition.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to this narrative, including an example of the above mentioned certificate and the original recommendation for the award of the OBE. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

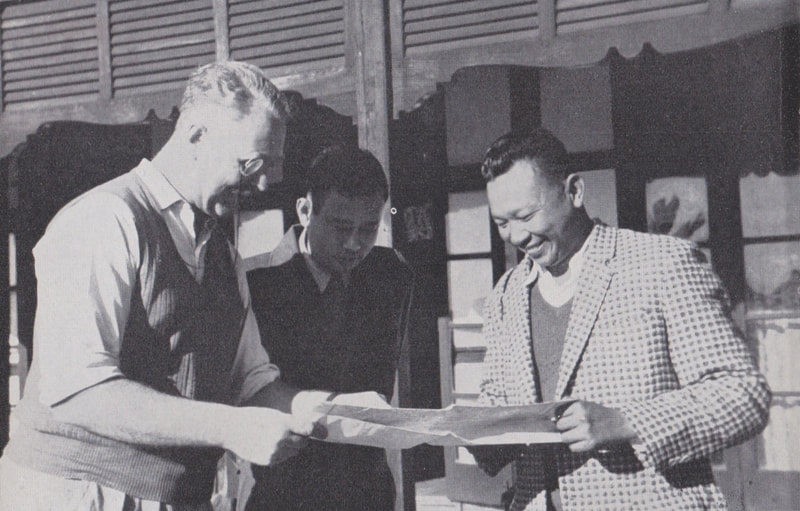

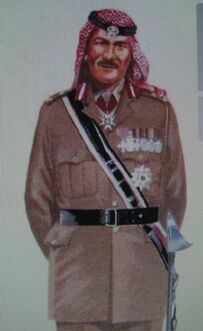

Cooke Pasha (1951).

Cooke Pasha (1951).

After war Sidney Cooke went on to command the Arab Legion. From the Osprey (Publishing) book on the subject written by Peter Young and with illustrations by Michael Roffe:

Cooke Pasha

Born on the 21st July 1903, Major-General Sidney Arthur Cooke joined the Arab Legion in 1951 to assume command of its 1st Division. Like many officers who came to the Legion, he was no stranger to Jordan, having some years previously commanded his battalion, the Royal Lincoln’s when it had formed part of ‘O’ Force, the British Garrison in Aqaba.

A tall, broad-shouldered man, Sam Cooke was always immaculately dressed and set a high standard for an already well turned out division. The particular attributes which he brought to the Legion were those of an organiser and administrator, and there is little doubt that the efficiency of 1st Division, probably at its peak around mid-1955, was largely the result of his efforts.

He was possessed of great patience, an essential quality for any British officer with the Legion. Arab soldiers are amongst the keenest to learn, but it must be admitted that they do not always take kindly to European discipline and the thorough training which most modern armies require.

Patient though Cooke was, he could be caustic. Never hesitating to take a decision himself, he could be intolerant of others who were less decisive. On one occasion a staff officer, questioned as to the action taken over some incident, admitted to Cooke, that he had in fact done nothing. “To do nothing”, came the classic rejoinder, “is always wrong."

Cooke never had to command his division in full-scale operations, but he was faced with the equally difficult task of training for war, while simultaneously directing defensive operations on the West Bank under conditions not of peace but of armistice. Towards the end of his tenure he had also to deal with a massive internal security problem in Amman and the main towns and refugee camps on the East Bank.

These heavy responsibilities never affected his composure. After the assassination of King Abdallah, Cooke’s commander General John Bagot Glubb telephoned him orders for the maintenance of law and order in Jerusalem. Glubb recalled: One thing about Cooke was that he was always calm and acknowledged these orders, as if I had said, come round later and have a drink. He was a man who inspired confidence in all those under his command.

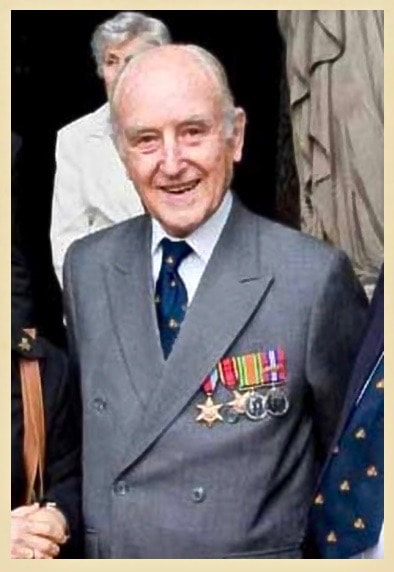

After his retirement from military life, Sidney Cooke became a member of the Burma Star Association and was a keen attendee of the many Chindit reunions. He was for a time the President of the Chindit Old Comrades Association and kept in touch with many of his former comrades from Operation Longcloth. Sidney Cooke lived for many years in Holt, a market town in the county of Norfolk, where sadly he passed away aged 73 on the 25th March 1977.

Cooke Pasha

Born on the 21st July 1903, Major-General Sidney Arthur Cooke joined the Arab Legion in 1951 to assume command of its 1st Division. Like many officers who came to the Legion, he was no stranger to Jordan, having some years previously commanded his battalion, the Royal Lincoln’s when it had formed part of ‘O’ Force, the British Garrison in Aqaba.

A tall, broad-shouldered man, Sam Cooke was always immaculately dressed and set a high standard for an already well turned out division. The particular attributes which he brought to the Legion were those of an organiser and administrator, and there is little doubt that the efficiency of 1st Division, probably at its peak around mid-1955, was largely the result of his efforts.

He was possessed of great patience, an essential quality for any British officer with the Legion. Arab soldiers are amongst the keenest to learn, but it must be admitted that they do not always take kindly to European discipline and the thorough training which most modern armies require.

Patient though Cooke was, he could be caustic. Never hesitating to take a decision himself, he could be intolerant of others who were less decisive. On one occasion a staff officer, questioned as to the action taken over some incident, admitted to Cooke, that he had in fact done nothing. “To do nothing”, came the classic rejoinder, “is always wrong."

Cooke never had to command his division in full-scale operations, but he was faced with the equally difficult task of training for war, while simultaneously directing defensive operations on the West Bank under conditions not of peace but of armistice. Towards the end of his tenure he had also to deal with a massive internal security problem in Amman and the main towns and refugee camps on the East Bank.

These heavy responsibilities never affected his composure. After the assassination of King Abdallah, Cooke’s commander General John Bagot Glubb telephoned him orders for the maintenance of law and order in Jerusalem. Glubb recalled: One thing about Cooke was that he was always calm and acknowledged these orders, as if I had said, come round later and have a drink. He was a man who inspired confidence in all those under his command.

After his retirement from military life, Sidney Cooke became a member of the Burma Star Association and was a keen attendee of the many Chindit reunions. He was for a time the President of the Chindit Old Comrades Association and kept in touch with many of his former comrades from Operation Longcloth. Sidney Cooke lived for many years in Holt, a market town in the county of Norfolk, where sadly he passed away aged 73 on the 25th March 1977.

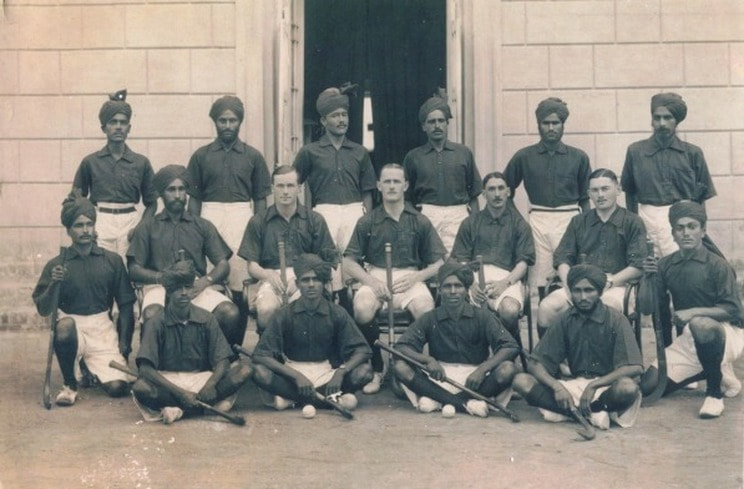

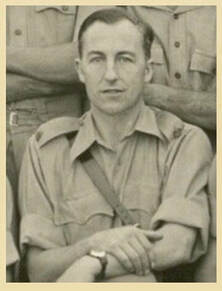

Lt-Colonel Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander

The most senior Gurkha officer on Operation and commander of Southern Group, Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander was born on the 4th July 1898 in Umzinto, a town some 70km or so from Durban in the Kwazulu/Natal province of South Africa. He was the son of Major William Alexander and Ethel Rubina Arbuthnot and the younger brother of Gilbert William. Both Leigh and Gilbert were keen sportsmen and played cricket and hockey for several representative sides at school and later on in colonial India.

Leigh was commissioned into the Indian Army on the 27th October 1917, when aged 19. He had studied at the Officers Cadet College in Quetta and was gazetted to 2nd Lieutenant on the above mentioned date, eventually taking up his commission in the 2/5 Royal Gurkha Rifles at their regimental centre in Abbottabad. The Staff College at Quetta had been founded in 1907 and was the main training centre for young officer cadets destined for service in the Indian Army. Leigh's Army career progressed steadily with promotion to Captain in 1922 and again to Major in 1935. During the latter years of WW1, he served with the 2/5 Royal Gurkha Rifle Frontier Force on the Indian/Afghanistan border, or Northwest Frontier as it was known back then.

By mid-1942, Alexander was commander of the newly raised 3rd Battalion of the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles, known as the Sirmoor Rifles. This young and inexperienced battalion were posted to form one half of the infantry element of Brigadier Wingate's 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. In July 1942, the battalion arrived in the Central Provinces of India and took up their Chindit training at the Saugor Camp.

I have already written about Colonel Alexander at length on these website pages and see no advantage in repeating those words here. To read more about him, please click on the following link: Lieutenant-Colonel L.A. Alexander

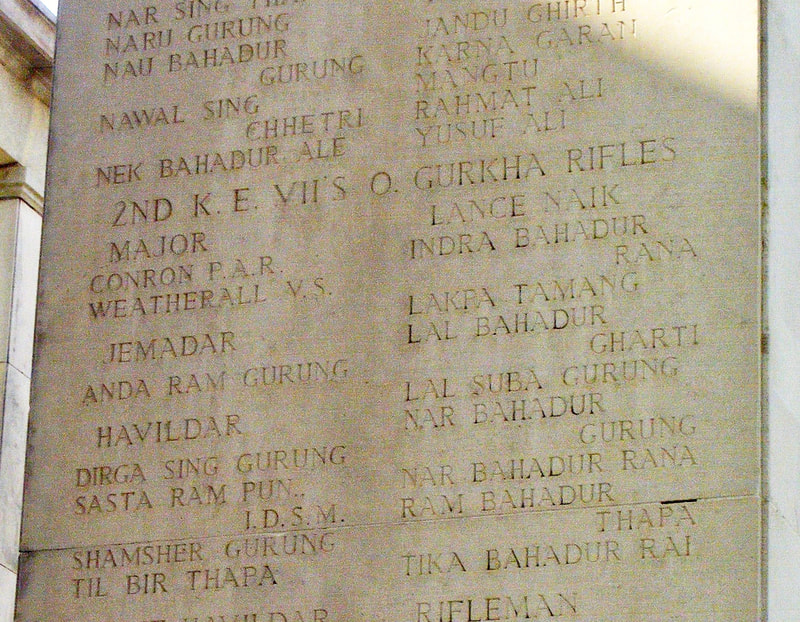

Tragically, Colonel Alexander lost his life during the first Chindit expedition, suffering mortal injuries from a Japanese mortar shell on the 28th April 1943. His body, and that of Lt. De la Rue, who had perished alongside him that day, were later recovered after the war and re-buried firstly in Mandalay and then finally in the mid-1950's at Taukkyan War Cemetery.

Over the years of my research, quite remarkably, I have been contacted by four of Colonel Alexander's grandchildren. Bruce Luxmoore was first to make contact back in 2011, followed closely by his cousin, Jane Marsh that same year. In 2013, James Luxmoore made contact via his friend, Kevin Hills and finally Rory Luxmoore in 2016. Many of the families comments and information can be seen on the webpage highlighted above.

I would like to finish this narrative by reproducing Rory's short obituary notice in honour of his grandfather after a visit to Taukkyan War Cemetery in March 2016:

Lieutenant Colonel Leigh Alexander

Leigh was born in Umzinto, Natal, South Africa July 4, 1898 and died in Burma on April 28th 1943 at the age of 45. He was British Army officer a first-class cricketer and a father to three children. He joined the Gurkhas on 11 May 1917 during the First World War and first saw service on the North West Frontier. He was commissioned into the British Indian Army on the 27 October 1917. He was promoted to Captain in 1922 and to Major in 1935.

In the Second World War he commanded the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Gurkha Rifles, and took part in the 1st Chindit expedition, a deep penetration raid behind Japanese lines, with the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade when he died during the operation. He was a great sportsman. He played first class cricket for India in 1920. He also excelled in field hockey and tennis. His wife Nancy Alexander (Dalrymple) boasted that he was also a good boxer and seen as one of the better marksmen.

Leigh had three children; Nigel, Vernon and Verity. He is survived by several grandchildren and great grandchildren including Nigel's daughter Jane Marsh and Verity's four son's Mark, Rory, Bruce and James Luxmoore.

The grandchildren grew up hearing stories about their grandfather from his wife Nancy. She remembers going on tiger hunts in Kashmir and meetings with the Maharajahs of different states of India. She also remembers that he was respected by the Gurkha (Nepalese) and Indian soldiers he served. He would ensure that all his men were cared for and fed before he ate and relaxed. He served his men with well until up his death in the jungles of Burma. He is written about in several books including Safer Than a Known Way by Lieutenant Ian MacHorton and A Signals Officer by Robin Painter.

It is with the greatest respect that we stand in front of his grave. We are humbled by the sacrifices he and others made during these times and wish with all our hearts that they have not been in vain. We pray that there can be peace for all.

The most senior Gurkha officer on Operation and commander of Southern Group, Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander was born on the 4th July 1898 in Umzinto, a town some 70km or so from Durban in the Kwazulu/Natal province of South Africa. He was the son of Major William Alexander and Ethel Rubina Arbuthnot and the younger brother of Gilbert William. Both Leigh and Gilbert were keen sportsmen and played cricket and hockey for several representative sides at school and later on in colonial India.

Leigh was commissioned into the Indian Army on the 27th October 1917, when aged 19. He had studied at the Officers Cadet College in Quetta and was gazetted to 2nd Lieutenant on the above mentioned date, eventually taking up his commission in the 2/5 Royal Gurkha Rifles at their regimental centre in Abbottabad. The Staff College at Quetta had been founded in 1907 and was the main training centre for young officer cadets destined for service in the Indian Army. Leigh's Army career progressed steadily with promotion to Captain in 1922 and again to Major in 1935. During the latter years of WW1, he served with the 2/5 Royal Gurkha Rifle Frontier Force on the Indian/Afghanistan border, or Northwest Frontier as it was known back then.

By mid-1942, Alexander was commander of the newly raised 3rd Battalion of the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles, known as the Sirmoor Rifles. This young and inexperienced battalion were posted to form one half of the infantry element of Brigadier Wingate's 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. In July 1942, the battalion arrived in the Central Provinces of India and took up their Chindit training at the Saugor Camp.

I have already written about Colonel Alexander at length on these website pages and see no advantage in repeating those words here. To read more about him, please click on the following link: Lieutenant-Colonel L.A. Alexander

Tragically, Colonel Alexander lost his life during the first Chindit expedition, suffering mortal injuries from a Japanese mortar shell on the 28th April 1943. His body, and that of Lt. De la Rue, who had perished alongside him that day, were later recovered after the war and re-buried firstly in Mandalay and then finally in the mid-1950's at Taukkyan War Cemetery.

Over the years of my research, quite remarkably, I have been contacted by four of Colonel Alexander's grandchildren. Bruce Luxmoore was first to make contact back in 2011, followed closely by his cousin, Jane Marsh that same year. In 2013, James Luxmoore made contact via his friend, Kevin Hills and finally Rory Luxmoore in 2016. Many of the families comments and information can be seen on the webpage highlighted above.

I would like to finish this narrative by reproducing Rory's short obituary notice in honour of his grandfather after a visit to Taukkyan War Cemetery in March 2016:

Lieutenant Colonel Leigh Alexander

Leigh was born in Umzinto, Natal, South Africa July 4, 1898 and died in Burma on April 28th 1943 at the age of 45. He was British Army officer a first-class cricketer and a father to three children. He joined the Gurkhas on 11 May 1917 during the First World War and first saw service on the North West Frontier. He was commissioned into the British Indian Army on the 27 October 1917. He was promoted to Captain in 1922 and to Major in 1935.

In the Second World War he commanded the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Gurkha Rifles, and took part in the 1st Chindit expedition, a deep penetration raid behind Japanese lines, with the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade when he died during the operation. He was a great sportsman. He played first class cricket for India in 1920. He also excelled in field hockey and tennis. His wife Nancy Alexander (Dalrymple) boasted that he was also a good boxer and seen as one of the better marksmen.

Leigh had three children; Nigel, Vernon and Verity. He is survived by several grandchildren and great grandchildren including Nigel's daughter Jane Marsh and Verity's four son's Mark, Rory, Bruce and James Luxmoore.

The grandchildren grew up hearing stories about their grandfather from his wife Nancy. She remembers going on tiger hunts in Kashmir and meetings with the Maharajahs of different states of India. She also remembers that he was respected by the Gurkha (Nepalese) and Indian soldiers he served. He would ensure that all his men were cared for and fed before he ate and relaxed. He served his men with well until up his death in the jungles of Burma. He is written about in several books including Safer Than a Known Way by Lieutenant Ian MacHorton and A Signals Officer by Robin Painter.

It is with the greatest respect that we stand in front of his grave. We are humbled by the sacrifices he and others made during these times and wish with all our hearts that they have not been in vain. We pray that there can be peace for all.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to Colonel Alexander and his life as a soldier, including a photograph of Rory Luxmoore and his children, Nelson and Alexandra at Taukkyan War Cemetery. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

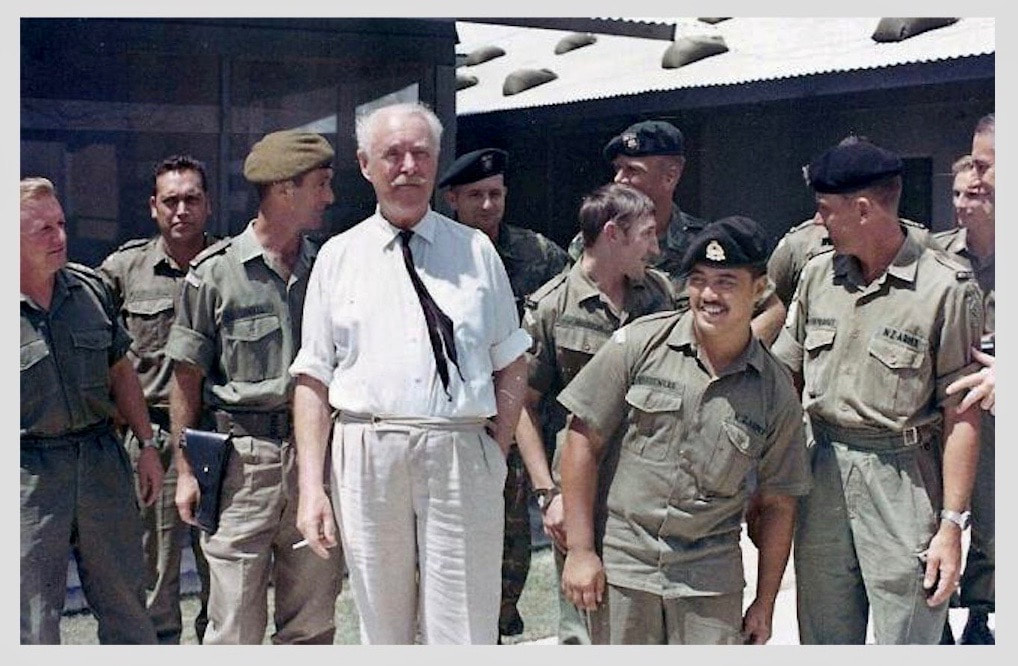

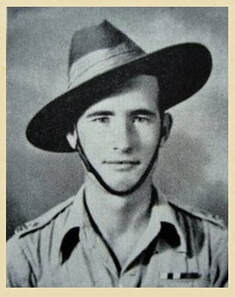

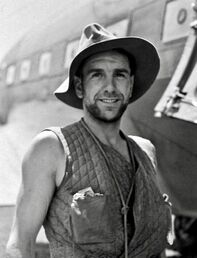

Major George Dunlop MC (1942).

Major George Dunlop MC (1942).

Major George Dickson Dunlop

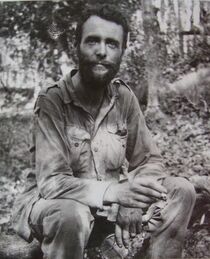

I found Major Dunlop leaning on his rifle. His tattered clothes, hanging loosely upon him, not only gave him a scarecrow aspect but accentuated the slightness of his figure. Yet his protruding red beard, curling upwards at the end, gave him a buccaneer look which added strength and purpose to the overall picture of this man. Penetrating green eyes, vitally alive in his drawn and sun-bronzed face, went well with the swashbuckling beard.

Firm and decisive though it was, George Dunlop's voice was tired. It had the underlying tone of tiredness inevitable in a man who, at this moment, had behind him more than ten long weeks of responsibility and decisions. Ten precarious weeks all the time with nerves at hair-trigger tautness with the responsibility of being a leader campaigning in the midst of the enemy.

(From the book, Safer Than a Known Way, by Ian MacHorton).

George Dickson Dunlop was born in Calcutta, (India) on the 6th April 1917. His father sadly died when George was just nine years old and for this reason his mother decided to take her young family back to Scotland to live. George attended Edinburgh Academy where he joined the school OTC. After leaving school he entered the Sandhurst Military Academy, from which he was commissioned on the 28th January 1938 into the 1st Battalion of the Royal Scots, based at the time at Catterick in North Yorkshire.

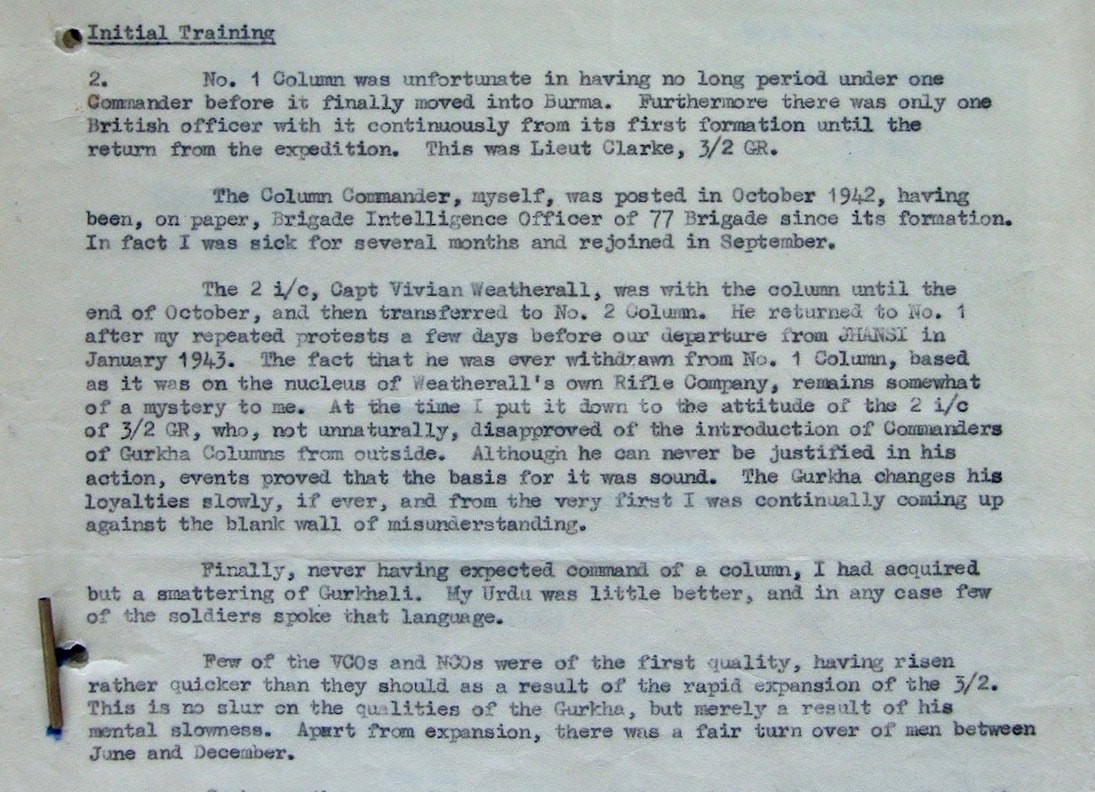

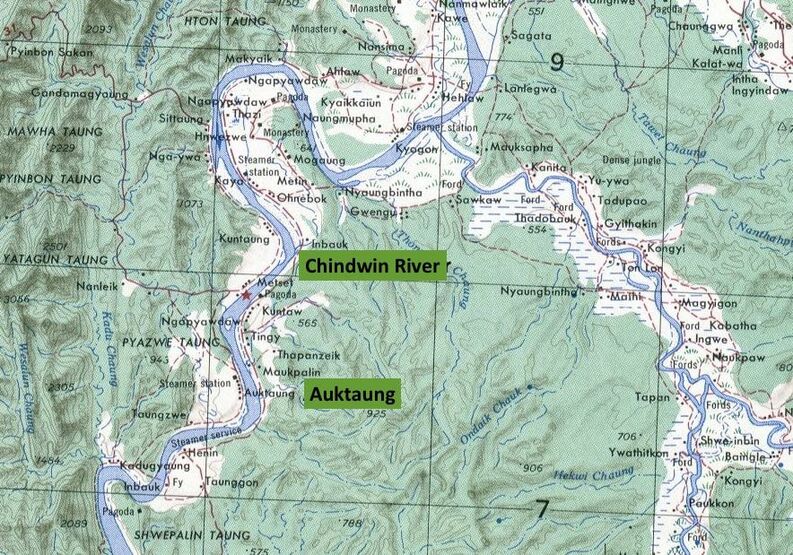

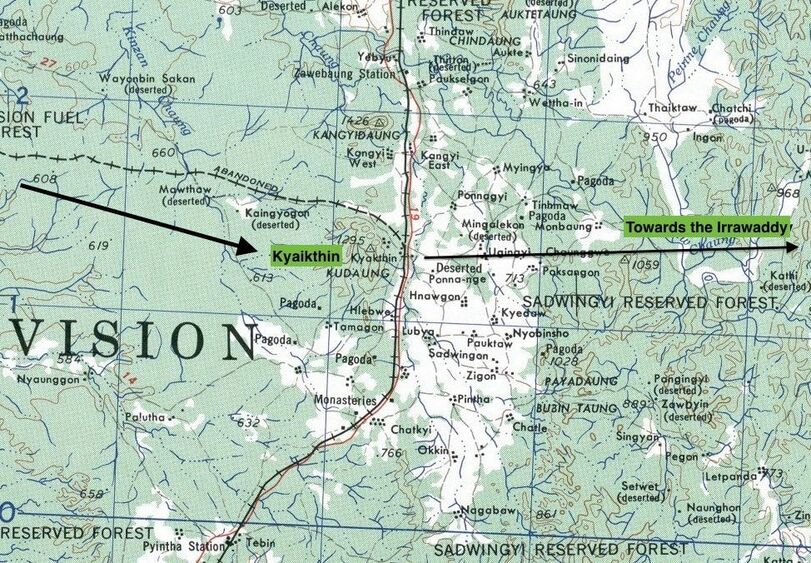

(War Substantive) Major George Dunlop MC was given command of No. 1 Column on Operation Longcloth, a predominantly Gurkha unit comprising some 392 personnel as of February 15th 1943. He had come to Chindit training fairly late on and had replaced Captain Vivian Weatherall as commander of the column. He had previously worked alongside Mike Calvert at the Bush Warfare School, based at Maymyo in Northern Burma and had participated on Mission 204, a clandestine operation on the Burma/China borders in conjunction with Chinese troops in late 1941. By the time of dispersal at the close of Operation Longcloth, Major Dunlop had under his command the remnants of not just his own column, but that of No. 2 Column and Southern Group Head Quarters. The above mentioned description of Dunlop's demeanour in May 1943 by Chindit officer Ian MacHorton, paints an in depth picture of George Dunlop during those arduous times.

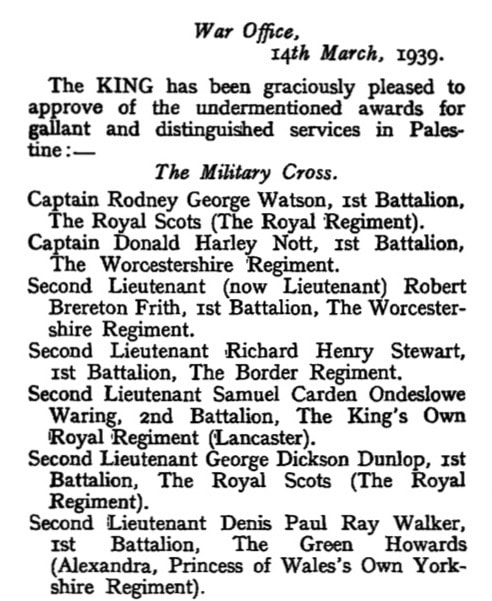

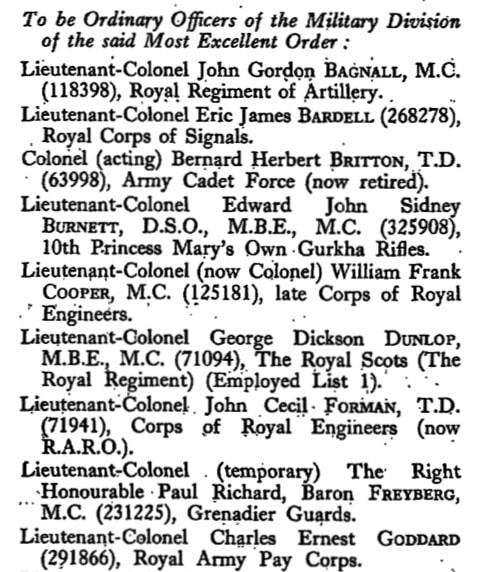

Previously to his service on the first Wingate expedition, he had fought in Hong Kong, Trans-Jordan and Palestine; where in October 1938 he was awarded the Military Cross for his efforts against the Arab Rebellion. As well as his MC, won at the tender age of just 21years, Dunlop was also Mentioned in Despatches on two occasions and awarded both the MBE and OBE.

I found Major Dunlop leaning on his rifle. His tattered clothes, hanging loosely upon him, not only gave him a scarecrow aspect but accentuated the slightness of his figure. Yet his protruding red beard, curling upwards at the end, gave him a buccaneer look which added strength and purpose to the overall picture of this man. Penetrating green eyes, vitally alive in his drawn and sun-bronzed face, went well with the swashbuckling beard.

Firm and decisive though it was, George Dunlop's voice was tired. It had the underlying tone of tiredness inevitable in a man who, at this moment, had behind him more than ten long weeks of responsibility and decisions. Ten precarious weeks all the time with nerves at hair-trigger tautness with the responsibility of being a leader campaigning in the midst of the enemy.

(From the book, Safer Than a Known Way, by Ian MacHorton).

George Dickson Dunlop was born in Calcutta, (India) on the 6th April 1917. His father sadly died when George was just nine years old and for this reason his mother decided to take her young family back to Scotland to live. George attended Edinburgh Academy where he joined the school OTC. After leaving school he entered the Sandhurst Military Academy, from which he was commissioned on the 28th January 1938 into the 1st Battalion of the Royal Scots, based at the time at Catterick in North Yorkshire.

(War Substantive) Major George Dunlop MC was given command of No. 1 Column on Operation Longcloth, a predominantly Gurkha unit comprising some 392 personnel as of February 15th 1943. He had come to Chindit training fairly late on and had replaced Captain Vivian Weatherall as commander of the column. He had previously worked alongside Mike Calvert at the Bush Warfare School, based at Maymyo in Northern Burma and had participated on Mission 204, a clandestine operation on the Burma/China borders in conjunction with Chinese troops in late 1941. By the time of dispersal at the close of Operation Longcloth, Major Dunlop had under his command the remnants of not just his own column, but that of No. 2 Column and Southern Group Head Quarters. The above mentioned description of Dunlop's demeanour in May 1943 by Chindit officer Ian MacHorton, paints an in depth picture of George Dunlop during those arduous times.

Previously to his service on the first Wingate expedition, he had fought in Hong Kong, Trans-Jordan and Palestine; where in October 1938 he was awarded the Military Cross for his efforts against the Arab Rebellion. As well as his MC, won at the tender age of just 21years, Dunlop was also Mentioned in Despatches on two occasions and awarded both the MBE and OBE.

Awards for gallant conduct recommended by the General Officer Commanding, British Forces in Palestine and Trans-Jordan (January 1939).

Submitted by the War Office and the Air Ministry.

I am directed by the Chairman of the committee to inform you that the following immediate award has been recommended:

2nd Lieutenant 71094 G. D. Dunlop (1st Battalion Royal Scots).

The Military Cross, for bravery of the highest order under heavy fire while in command of a platoon engaged with an enemy band near Fardisya on the 2nd October 1938, again near Irtah on the 9th November and on several other occasions.

London Gazette 14th March 1939.

Submitted by the War Office and the Air Ministry.

I am directed by the Chairman of the committee to inform you that the following immediate award has been recommended:

2nd Lieutenant 71094 G. D. Dunlop (1st Battalion Royal Scots).

The Military Cross, for bravery of the highest order under heavy fire while in command of a platoon engaged with an enemy band near Fardisya on the 2nd October 1938, again near Irtah on the 9th November and on several other occasions.

London Gazette 14th March 1939.

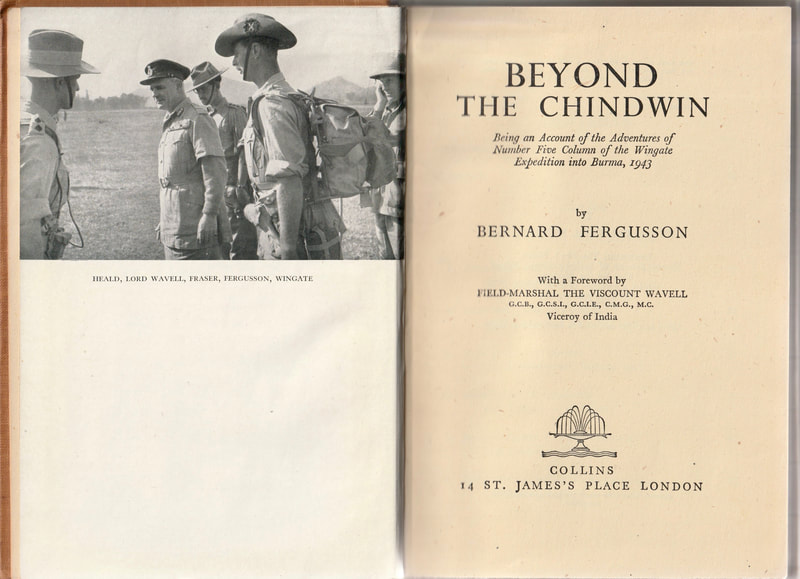

George Dunlop is mentioned in most books concerning the general overview of the two Chindit campaigns, but is featured particularly within:

Safer Than a Known Way, by Ian MacHorton

Wingate's Lost Brigade, by Philip Chinnery

Fighting Mad, by Mike Calvert

A Signal Honour, by Robin Painter

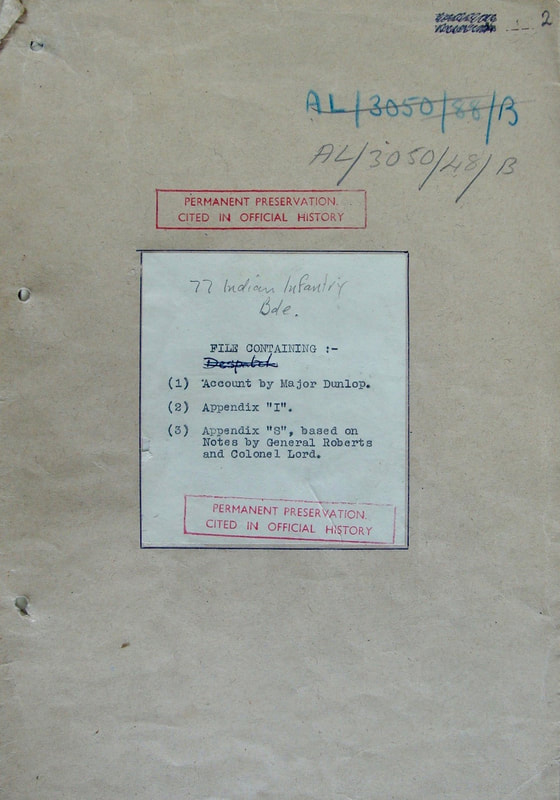

Major Dunlop also wrote down his experiences and that of his Chindit Column during Operation Longcloth in a report drafted immediately upon his return to Allied territory in 1943. This document is held at the British National Archives, under file reference CAB106/204:

discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C374143

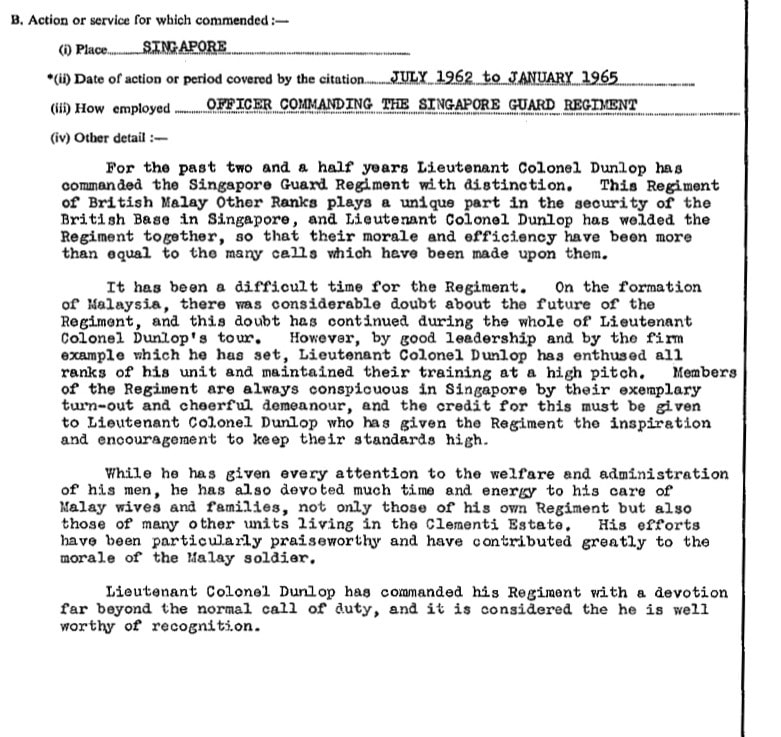

After the war he served in Greece during the country's civil war of 1948, performing liaison duties within the Greek Army and is remembered from those days as "possessing the happy knack of being able to advise his colleagues, without appearing to instruct them."

Following his time in Greece he served in Berlin and Korea with the British Army. From 1962 to 1965 he commanded the Singapore Guard Regiment which was made up from local Malay soldiers, but was commanded by British Officers. Immediately after leaving the Army he ran an Outward Bound Centre in Scotland.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to George Dunlop and his military career, including the original citation for the award of his OBE. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Safer Than a Known Way, by Ian MacHorton

Wingate's Lost Brigade, by Philip Chinnery

Fighting Mad, by Mike Calvert

A Signal Honour, by Robin Painter

Major Dunlop also wrote down his experiences and that of his Chindit Column during Operation Longcloth in a report drafted immediately upon his return to Allied territory in 1943. This document is held at the British National Archives, under file reference CAB106/204:

discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C374143

After the war he served in Greece during the country's civil war of 1948, performing liaison duties within the Greek Army and is remembered from those days as "possessing the happy knack of being able to advise his colleagues, without appearing to instruct them."

Following his time in Greece he served in Berlin and Korea with the British Army. From 1962 to 1965 he commanded the Singapore Guard Regiment which was made up from local Malay soldiers, but was commanded by British Officers. Immediately after leaving the Army he ran an Outward Bound Centre in Scotland.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to George Dunlop and his military career, including the original citation for the award of his OBE. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Obituary, Daily Telegraph December 2000

An officer who took on the armed gangs in Palestine and later joined a Chindit raid to deceive the Japanese in Burma; LIEUTENANT-COLONEL GEORGE DUNLOP, who has died aged 83, was awarded an MC when serving with the 1st Battalion, the Royal Scots in Palestine during the Arab rebellion.

On October 2nd 1938, the platoon Dunlop was commanding was on the way from Sarafand to Tulkarm, when it was fired on by a gang some 30 strong. Having arranged covering machine-gun fire, Dunlop led his men into the attack, inflicting at least three casualties. On November 9th, he and his platoon were in the vicinity of Irtah. When firing broke out from the houses on the village outskirts, Dunlop rushed forward and so placed his men that they were able to block exits from the village and to rout the attacking force.

During these operations, his citation stated: "Second Lieutenant Dunlop has shown bravery of the highest order." George Dickson Dunlop was born in Calcutta on April 6 1917. His father, an accountant, died when George was nine; his mother remarried and returned with her new husband and six children to her native Edinburgh, where George attended Edinburgh Academy and joined the OTC.

After Sandhurst, he was commissioned into the Royal Scots (the Royal Regiment) in 1937 and posted to the 1st Battalion at Catterick. Within a year, he was serving in Palestine, where, in addition to winning his MC aged 21, he was twice mentioned in despatches. By the time war broke out in 1939, Dunlop was with the 2nd Battalion in Hong Kong, commanding a Bren gun carrier platoon. In 1941, now in command of C Company, 2nd Royal Scots, he was asked to volunteer for a dangerous secret mission outside Hong Kong, for which he might select nine men to go with him. Reckoning that the mission could be no more dangerous than staying in Hong Kong - a view subsequently borne out by the 2nd Battalion's experience when the Japanese did attack - he volunteered. Mission 204, as the operation was called, took place in Burma in late 1941 and was concerned with, among other things, long range reconnaissance and the destruction of selected targets.

While in Burma, Dunlop met Orde Wingate, of whose military tactics he was already a keen student having only just missed Wingate when they were both serving in Palestine. He joined the Chindits and was placed in command of No.1 Column in the first long range penetration raid. With No. 2 Column, Dunlop and his men formed the deception force whose purpose was to be visible to the Japanese, to pose a threat, and so to tie down enemy forces while other columns did damage elsewhere. These tactics worked well, but at a heavy price.

When the Japanese closed in, Dunlop's column lost its mule transport and radios, which were crucial for air supply. Dunlop himself had to swim the Chindwin River and as he did so blessed his time spent in earlier days at Drumsheugh Baths in Edinburgh. When Dunlop got out of Burma with the remnants of Nos. 1 and 2 Columns, he weighed just six stone and was suffering from a variety of tropical diseases. On recovery, he became an instructor at the Special Forces Training School in India in 1943, after which he returned to Britain and some well-earned leave.

Dunlop then went as an instructor to 166 OCTU on the Isle of Man, and after that as chief instructor to Mons OCTU on its formation. There followed a spell as a liaison officer with the Greek Army on special (anti-Communist) operations in the Civil War of 1948, in recognition of which he was awarded an MBE. After attending the Staff College, Camberley, he was GSO2 (Ops), HQ Northern Ireland, after which he rejoined 1 Royal Scots. Subsequent postings took him to Berlin, Scotland, Korea and Egypt and twice to Singapore.

From 1962 to 1965 he commanded the Singapore Guard Regiment, composed of Malay soldiers and mainly British officers, during the period of the Confrontation with Indonesia. Physically tough, and possessing a quick, unconventional mind, Dunlop was known to his men as Dan after the character Desperate Dan in the Beano. At the end of his second tour in Singapore he was awarded an OBE. He retired from the Army in 1967.

Dunlop was then warden of the Outward Bound Centre at Loch Eil for a year, before joining the Guide Dogs for the Blind Association to run their Scottish office. He travelled the length and breadth of Scotland encouraging fund-raising branches, and his knowledge of Scotland and its history delighted many of the guide dog owners who accompanied him. He finally retired in 1981.

Dunlop's wise counsel, attractive smile, lack of pomposity and impish sense of humour - as well the kindness and consideration he showed for others - endeared him to all. He was genuinely interested in what other people had to say, and resolutely modest about his own accomplishments. He was a first-class rifle and pistol shot, and during his Army days trained his battalion swimming team. He was also a skilful model-maker and sketcher in pencil and pen-and-ink. He kept up his regimental connections, seldom missing an annual reunion. He is survived by his wife Aline (nee Arthur), whom he married in 1944, and by their son and two daughters.

An officer who took on the armed gangs in Palestine and later joined a Chindit raid to deceive the Japanese in Burma; LIEUTENANT-COLONEL GEORGE DUNLOP, who has died aged 83, was awarded an MC when serving with the 1st Battalion, the Royal Scots in Palestine during the Arab rebellion.

On October 2nd 1938, the platoon Dunlop was commanding was on the way from Sarafand to Tulkarm, when it was fired on by a gang some 30 strong. Having arranged covering machine-gun fire, Dunlop led his men into the attack, inflicting at least three casualties. On November 9th, he and his platoon were in the vicinity of Irtah. When firing broke out from the houses on the village outskirts, Dunlop rushed forward and so placed his men that they were able to block exits from the village and to rout the attacking force.

During these operations, his citation stated: "Second Lieutenant Dunlop has shown bravery of the highest order." George Dickson Dunlop was born in Calcutta on April 6 1917. His father, an accountant, died when George was nine; his mother remarried and returned with her new husband and six children to her native Edinburgh, where George attended Edinburgh Academy and joined the OTC.

After Sandhurst, he was commissioned into the Royal Scots (the Royal Regiment) in 1937 and posted to the 1st Battalion at Catterick. Within a year, he was serving in Palestine, where, in addition to winning his MC aged 21, he was twice mentioned in despatches. By the time war broke out in 1939, Dunlop was with the 2nd Battalion in Hong Kong, commanding a Bren gun carrier platoon. In 1941, now in command of C Company, 2nd Royal Scots, he was asked to volunteer for a dangerous secret mission outside Hong Kong, for which he might select nine men to go with him. Reckoning that the mission could be no more dangerous than staying in Hong Kong - a view subsequently borne out by the 2nd Battalion's experience when the Japanese did attack - he volunteered. Mission 204, as the operation was called, took place in Burma in late 1941 and was concerned with, among other things, long range reconnaissance and the destruction of selected targets.

While in Burma, Dunlop met Orde Wingate, of whose military tactics he was already a keen student having only just missed Wingate when they were both serving in Palestine. He joined the Chindits and was placed in command of No.1 Column in the first long range penetration raid. With No. 2 Column, Dunlop and his men formed the deception force whose purpose was to be visible to the Japanese, to pose a threat, and so to tie down enemy forces while other columns did damage elsewhere. These tactics worked well, but at a heavy price.

When the Japanese closed in, Dunlop's column lost its mule transport and radios, which were crucial for air supply. Dunlop himself had to swim the Chindwin River and as he did so blessed his time spent in earlier days at Drumsheugh Baths in Edinburgh. When Dunlop got out of Burma with the remnants of Nos. 1 and 2 Columns, he weighed just six stone and was suffering from a variety of tropical diseases. On recovery, he became an instructor at the Special Forces Training School in India in 1943, after which he returned to Britain and some well-earned leave.

Dunlop then went as an instructor to 166 OCTU on the Isle of Man, and after that as chief instructor to Mons OCTU on its formation. There followed a spell as a liaison officer with the Greek Army on special (anti-Communist) operations in the Civil War of 1948, in recognition of which he was awarded an MBE. After attending the Staff College, Camberley, he was GSO2 (Ops), HQ Northern Ireland, after which he rejoined 1 Royal Scots. Subsequent postings took him to Berlin, Scotland, Korea and Egypt and twice to Singapore.

From 1962 to 1965 he commanded the Singapore Guard Regiment, composed of Malay soldiers and mainly British officers, during the period of the Confrontation with Indonesia. Physically tough, and possessing a quick, unconventional mind, Dunlop was known to his men as Dan after the character Desperate Dan in the Beano. At the end of his second tour in Singapore he was awarded an OBE. He retired from the Army in 1967.

Dunlop was then warden of the Outward Bound Centre at Loch Eil for a year, before joining the Guide Dogs for the Blind Association to run their Scottish office. He travelled the length and breadth of Scotland encouraging fund-raising branches, and his knowledge of Scotland and its history delighted many of the guide dog owners who accompanied him. He finally retired in 1981.

Dunlop's wise counsel, attractive smile, lack of pomposity and impish sense of humour - as well the kindness and consideration he showed for others - endeared him to all. He was genuinely interested in what other people had to say, and resolutely modest about his own accomplishments. He was a first-class rifle and pistol shot, and during his Army days trained his battalion swimming team. He was also a skilful model-maker and sketcher in pencil and pen-and-ink. He kept up his regimental connections, seldom missing an annual reunion. He is survived by his wife Aline (nee Arthur), whom he married in 1944, and by their son and two daughters.

In February 2016, I was delighted to receive an email from George Dunlop's son, Peter:

My father was Major George Dunlop MC. As you already know No.1 Column penetrated the furthest eastwards in 1943 and my father was one of the last Chindits to get out of Burma that year. I was interested to read the extract from his debriefing which mentions an argument with Wingate back in India. In my recollection he was sometimes critical but generally supportive of Wingate's ideas, in fact he applied to join Wingate in Palestine during 1937/38, but his application was refused by the commander of 1st Royal Scots.

He was a member of the old comrades association until he died in 2000, but because we lived in Scotland he was at some distance from most other members. He kept in touch with fellow Scot Bernard Ferguson and also with Mike Calvert who sometimes came to stay with us. He left a fair amount of paperwork about his army career, but so far I have concentrated on his very complete writings about his time during the Greek civil war in 1948. His posting to Greece was clearly as a result of his earlier guerrilla war experience.

I will have to get hold of a full copy of his Longcloth debrief. He like may others, spoke little of his wartime experiences, except when others who had served in Burma were around, but he did occasionally mention that during his way out from Burma he had drawn his pistol and threatened to shoot some of his men who wanted to give up, having picked up Japanese leaflets that sought to persuade Chindits to surrender. After Longcloth, my father was summoned to Delhi to meet with Wingate, but was sent immediately back to hospital and did not take up active service again for many months.

My father was always considered by his colleagues to be a first class regimental officer, he passed Staff College, but sadly was twice passed over for command of his own regiment because of successive amalgamations and the reordering of seniority by 21st birthday in place of date of commission. He had no time for desk wallahs and thus failed to make friends among those who did not know him well.

Steve, if you have anything you can send me about my father I would be very pleased to receive it. Best regards, Peter Dunlop.

To conclude this appreciation of George Dunlop and his time as a Chindit commander, written below are some of his own thoughts on the command structure during Operation Longcloth and his reflections about how the expedition was assessed back in India, especially in relation to the Gurkha columns:

The great mistake was to have commanders who could not speak directly and properly to their men. Quite apart from misunderstanding itself, there was far too great a strain placed on the commander. In Gurkha columns there were men of four different races and language. To get these to work as a unit in times of great hardship was difficult in the extreme. I have to confess that it wore me right down.

The Commander must be fit and as strong as the best of his men, as far more is asked of him than of anyone else. Acting on our own as we were in Burma, every single thing, right down to the last grain of rice, had to be arranged through him. He decided everything and took all the blame if it went wrong. No doubt that this is how it should be; but it is hard nevertheless.

There was so little written about the Gurkha decoy section (Southern Group) and No. 1 Column in 1943. I have often thought that my report, written after a request from General Scoones was repressed to allow the propaganda myth that the operation had been a success to persist and prevail. To be honest, after fifty years have passed by, I do not think too much about that time in my military career. Remembering the deaths and suffering of so many friends and comrades gives me no pleasure, so I have left it to others to tell the tale.

The great mistake was to have commanders who could not speak directly and properly to their men. Quite apart from misunderstanding itself, there was far too great a strain placed on the commander. In Gurkha columns there were men of four different races and language. To get these to work as a unit in times of great hardship was difficult in the extreme. I have to confess that it wore me right down.

The Commander must be fit and as strong as the best of his men, as far more is asked of him than of anyone else. Acting on our own as we were in Burma, every single thing, right down to the last grain of rice, had to be arranged through him. He decided everything and took all the blame if it went wrong. No doubt that this is how it should be; but it is hard nevertheless.

There was so little written about the Gurkha decoy section (Southern Group) and No. 1 Column in 1943. I have often thought that my report, written after a request from General Scoones was repressed to allow the propaganda myth that the operation had been a success to persist and prevail. To be honest, after fifty years have passed by, I do not think too much about that time in my military career. Remembering the deaths and suffering of so many friends and comrades gives me no pleasure, so I have left it to others to tell the tale.

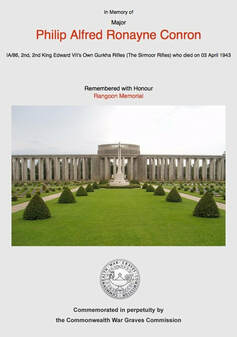

Major Arthur Alfred John Emmett.

Major Arthur Alfred John Emmett.

Major Arthur Alfred John Emmett

Very little has ever been written about Arthur Emmett and his experiences during the first Wingate expedition in 1943. Major Emmett was the commander of No. 2 Column on Operation Longcloth having been commissioned into the Indian Army in July 1941 and posted to the newly formed 3rd Battalion of the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles.

In August 2017, I was extremely fortunate to receive an email from Alex McMurray, the nephew of Major Emmett, who in turn put me in contact with Arthur Emmett's son, Andrew. It was from these communications, which included a visit to Andrew's home in December 2017, that the following information was put together.

Major Arthur Alfred John Emmett

Major Arthur Emmett, who had been a tea planter in North Bengal before the war, I found to be a kindly man with a quiet smile that instantly put one at ease.[1]