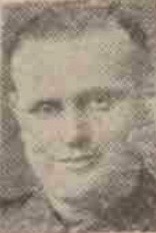

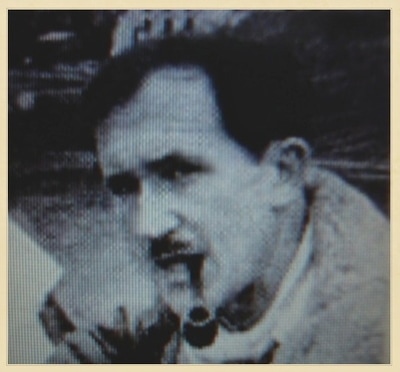

Pte. Arthur Leslie Howney

This is my Grandad, the photograph was taken sometime during his early infantry training. It is one of only four images that we have of him from that time.

He has always been the mystery man of our family, not just because we lost him so cruelly in 1943, but even in terms of his own family roots and history.

My brother Marc has spent many a long hour researching and collating the general family tree. In regard to Arthur all he had to go on was his death certificate from the War Office and it was through this document that our journey began.

"died whilst in Japanese hands." Apart from his name, service number and place of demise (Burma) this was all that appeared on his death certificate. We knew he had died in Burma in 1943 and that Nan had been very lucky to have travelled to Rangoon in 1987 with the British Legion and the War Widows Association. A trip that was to change her outlook on her husbands World War 2 service and give her some sort of closure after 43 years of waiting. With his details from the Commonwealth Graves Commission and the scant detail on the death certificate, my brother had worked out that Granddad had been a Chindit in 1943 and was part of the 13th Battalion, of the King's Liverpool Regiment, which formed the British half of the infantry soldiers for the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade that year.

He has always been the mystery man of our family, not just because we lost him so cruelly in 1943, but even in terms of his own family roots and history.

My brother Marc has spent many a long hour researching and collating the general family tree. In regard to Arthur all he had to go on was his death certificate from the War Office and it was through this document that our journey began.

"died whilst in Japanese hands." Apart from his name, service number and place of demise (Burma) this was all that appeared on his death certificate. We knew he had died in Burma in 1943 and that Nan had been very lucky to have travelled to Rangoon in 1987 with the British Legion and the War Widows Association. A trip that was to change her outlook on her husbands World War 2 service and give her some sort of closure after 43 years of waiting. With his details from the Commonwealth Graves Commission and the scant detail on the death certificate, my brother had worked out that Granddad had been a Chindit in 1943 and was part of the 13th Battalion, of the King's Liverpool Regiment, which formed the British half of the infantry soldiers for the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade that year.

The image to the right is Granddad's memorial plaque from Rangoon War Cemetery.

Our next step was to apply for Arthur's Army Service Records from the MOD offices at Glasgow. These documents duly arrived and with them the story began to open up for us.

We discovered that he had begun his Army service with the Devonshire Regiment and was part of their 9th Battalion. In 1941 after his initial training, he was posted to the above battalion and they began to perform a series of coastal defence duties along the south east coastline of England.

"ceased to be attached." This was the entry in the service records as of 17/06/1942 and this was the point in time when he found himself part of a draft of men destined for hotter climes.

It is likely that he travelled to India as part of convoy 'WS20', as this convoy matches both his date of transfer to the new draft at embarkation and then the convoys arrival in India. WS20 left Liverpool on the 21st of June 1942 and after taking in Freetown and Durban en route, reached Bombay in early August.

Our next step was to apply for Arthur's Army Service Records from the MOD offices at Glasgow. These documents duly arrived and with them the story began to open up for us.

We discovered that he had begun his Army service with the Devonshire Regiment and was part of their 9th Battalion. In 1941 after his initial training, he was posted to the above battalion and they began to perform a series of coastal defence duties along the south east coastline of England.

"ceased to be attached." This was the entry in the service records as of 17/06/1942 and this was the point in time when he found himself part of a draft of men destined for hotter climes.

It is likely that he travelled to India as part of convoy 'WS20', as this convoy matches both his date of transfer to the new draft at embarkation and then the convoys arrival in India. WS20 left Liverpool on the 21st of June 1942 and after taking in Freetown and Durban en route, reached Bombay in early August.

The 13th Kings had been in India since January 1942, where they initially performed garrison duties from their base at the Gough Barracks in Secunderabad. Fate took them into Wingate's arms and they became part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and began to train as a Long Range Penetration force. This proved tough for many of the city born soldiers of the King's battalion. Their average age was 33 and this type of physical based training soon began to take its toll.

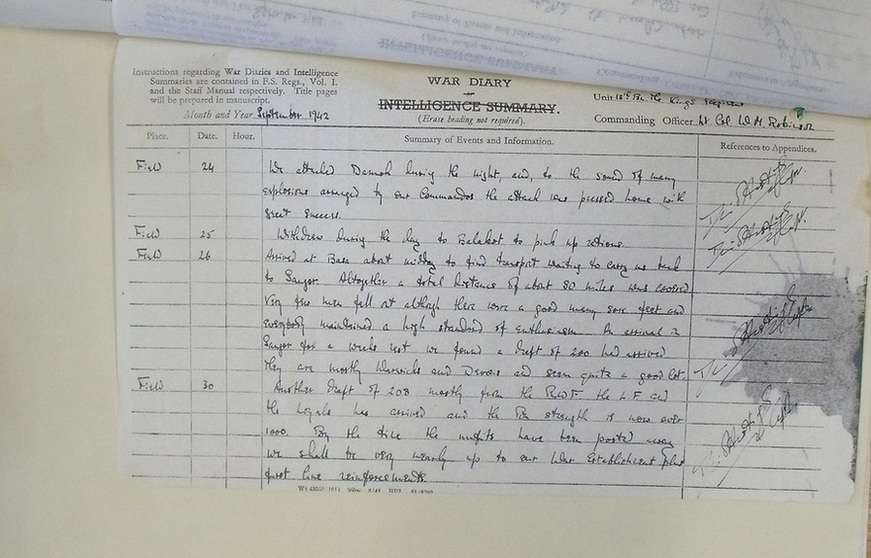

This was how Arthur Howney ended up joining the battalion at the training camp in Saugor, which was located in the Central Provinces of India. The War Diary page (above) marks the day (September 26th 1942) he reported for duty with Wingate's fledgling Chindits. The quote from the Adjutant in the diary states: a draft of 200 had arrived, they are mostly Warwicks and Devons and seem quite a good lot.

I should say here that the 13th King's War Diary can be found at the National Archives located at Kew, London. This has become my second home and is where the majority of the information I have found originates from. Reading the 1942 War Diary at Kew was one of the first things I did as part of my research into Granddad's Burma story. The other was to try and find his POW Index card which are also held at the National Archives. I remember that particular day very clearly and I remember the great disappointment when no card was found. These cards are a record for the majority of Far East POW's from WW2 and show detail in both English and Japanese characters about the prisoner in question. Mostly it is basic detail, name, rank, date of capture and so on, but sometimes you can be lucky and find out more personal information about the soldiers time as a prisoner of war. But I am moving the tale too far forward, let us go back to the War diaries.

The next and obvious step was to read the War Diary for 1943, the account of the operation itself. I think I first did this in 2007. The diary, supplemented by a host of books gave me a good understanding of Operation Longcloth, its objectives and main players, but could not establish my Granddad's involvement.

In 2008 I took a trip to Burma, traveling with my Mum, sister and brother to many of the places of Chindit folklore. The point here is that when we were out in Burma we neither knew Granddad's place of death nor his Chindit column unit. The trip was emotional and memorable for many reasons, not least for meeting the wonderful people of this amazing country.

An example of a WW1 pair, the British War and Victory medals.

An example of a WW1 pair, the British War and Victory medals.

As I sat in Rangoon War Cemetery that day in March 2008, I promised myself, but more importantly my Granddad and all the men that lay all around him that I would unlock their story. And shortly afterwards fate or serendipity first stepped in to help my quest.

Whilst browsing eBay one day in early 2009, I noticed the WW1 medals of a man named Maurice Yacoby had come up for sale. I was attracted to the medals because, one, they belonged to a man of the Liverpool Regiment and two, because the surname, although spelled slightly differently was the same as that of my best mate at school.

I bid, I won and they duly arrived. Nothing special, just a ordinary WW1 pair to a man who survived the horrors of that conflict.

However, the medals were not to stay with me for long. Asking for information on the British Medal Forum, I enquired as to the likely battalion of Yacoby whilst serving with the King's Liverpool Regiment in WW1. As usual I received some prompt and good information, but then a reply came up that caused quite a surprise. A relative of Maurice Yacoby had seen my request for information and wondered if they might have his medals returned to their family. I was in two minds to be honest, but eventually realised that it was the right thing to do given the circumstances.

Roy was a keen WW1 researcher and we agreed to meet up at the National Archives, where else! Having handed the medals back over a cup of tea in the Archives cafeteria, he showed me several areas of the Archives I had not really explored before and how to access some of the other document data bases. He asked me what I had ordered to view that day and then offered the use of his spare digital camera to photograph the files, bypassing the laborious reading and note taking from previous visits.

I began to photograph the War Diaries of the 13th King's, 1942 and then 1943, they are large files and I happily clicked away until I reached the latter pages of the second diary. There suddenly in front of me were six pages of nominal rolls, the Missing in Action lists of Brigade HQ and for columns 5, 7 and 8. These pages were not there in 2007 when I first read the diary and I was astounded by their miraculous appearance, but also very excited.

Finding Arthur as I have said before, is never easy or straight forward, he was not present in an alphabetical search of the list, but did finally leap out at me half way down one of the pages for the men of Column 5, listed as missing in action on 18/04/1943. So he had served under Bernard Fergusson, whose book Beyond the Chindwin I had read many times previously during the early days of my research.

Whilst browsing eBay one day in early 2009, I noticed the WW1 medals of a man named Maurice Yacoby had come up for sale. I was attracted to the medals because, one, they belonged to a man of the Liverpool Regiment and two, because the surname, although spelled slightly differently was the same as that of my best mate at school.

I bid, I won and they duly arrived. Nothing special, just a ordinary WW1 pair to a man who survived the horrors of that conflict.

However, the medals were not to stay with me for long. Asking for information on the British Medal Forum, I enquired as to the likely battalion of Yacoby whilst serving with the King's Liverpool Regiment in WW1. As usual I received some prompt and good information, but then a reply came up that caused quite a surprise. A relative of Maurice Yacoby had seen my request for information and wondered if they might have his medals returned to their family. I was in two minds to be honest, but eventually realised that it was the right thing to do given the circumstances.

Roy was a keen WW1 researcher and we agreed to meet up at the National Archives, where else! Having handed the medals back over a cup of tea in the Archives cafeteria, he showed me several areas of the Archives I had not really explored before and how to access some of the other document data bases. He asked me what I had ordered to view that day and then offered the use of his spare digital camera to photograph the files, bypassing the laborious reading and note taking from previous visits.

I began to photograph the War Diaries of the 13th King's, 1942 and then 1943, they are large files and I happily clicked away until I reached the latter pages of the second diary. There suddenly in front of me were six pages of nominal rolls, the Missing in Action lists of Brigade HQ and for columns 5, 7 and 8. These pages were not there in 2007 when I first read the diary and I was astounded by their miraculous appearance, but also very excited.

Finding Arthur as I have said before, is never easy or straight forward, he was not present in an alphabetical search of the list, but did finally leap out at me half way down one of the pages for the men of Column 5, listed as missing in action on 18/04/1943. So he had served under Bernard Fergusson, whose book Beyond the Chindwin I had read many times previously during the early days of my research.

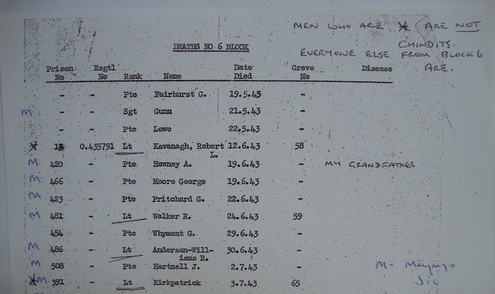

POW deaths, Block 6, Rangoon Jail.

POW deaths, Block 6, Rangoon Jail.

The next stroke of good fortune came not long after the Yacoby incident. I had made contact with the author Phil Chinnery and provided him with some documents and photos as a help towards his new book (2010) Wingate's Lost Brigade.

We had talked in general about the first Chindit expedition and in particular the men who became POW's back then. About two weeks or so after our meeting I came home from work to find a large A4 envelope waiting for me on my door mat. Contained within, were the lists of deaths from prison Blocks 3 and 6 inside Rangoon Jail. On page one just five names down, was my Granddad's name. Arthur Leslie Howney was the fifth Chindit to die inside Rangoon Jail in 1943 and had perished shortly after arriving in Block 6 on the 19th June. This date differed slightly from his Army death certificate which states the 17th June.

We had talked in general about the first Chindit expedition and in particular the men who became POW's back then. About two weeks or so after our meeting I came home from work to find a large A4 envelope waiting for me on my door mat. Contained within, were the lists of deaths from prison Blocks 3 and 6 inside Rangoon Jail. On page one just five names down, was my Granddad's name. Arthur Leslie Howney was the fifth Chindit to die inside Rangoon Jail in 1943 and had perished shortly after arriving in Block 6 on the 19th June. This date differed slightly from his Army death certificate which states the 17th June.

Denny Sharp's dispersal group, safe back over the Chindwin.

Denny Sharp's dispersal group, safe back over the Chindwin.

So at last we had something factual to go on, granddad's column placement and his definite place of death. Rangoon Jail had been pulled down by the Burmese government sometime in the 1980's (I think) and not being able to visit this location in 2008 was one of the few disappointments of that amazing tour.

I continued with my search and began to close in on what I thought could be a possible scenario for my Granddad's fate back in 1943. Now armed with the MIA date of 18/04/1943, I began to re-read all the books and diaries once again.

The men of 5 Column that shared Arthur's MIA date were James Ambrose and William Robert Jordan. Both these men had featured regularly in my research and I had made contact with James's daughter Val in July 2009 and we had shared information and photos.

William Jordan had always interested me, as he had been briefly mentioned in Phil Chinnery's other book on the Chindits March or Die and had also been awarded the Military Medal for his time in Burma. The reason for his award still eludes me and his family to this day.

NB. On 31st October 2011, I spoke for the first time with the family of William Jordan, who had seen a post I had left on the Burma Star forum in 2009.

From Bernard Fergusson's book, Beyond the Chindwin:

Denny Sharp had bumped a patrol that very hour, two miles north of us (Fergusson's dispersal group). He had gone right-handed round Nanhkin and come back on to the track beyond it. One of his men had collapsed from exhaustion, they were giving him half an hour's rest to see if he would recover. It was during this period that the Japs came up the path and bumped their sentry.

The incident described above occurred on the 18th April and involved the dispersal group of 22 men (see photo above) led by Flight Lieutenant Denis Sharp, 5 Column's RAF Air Liaison officer. Everything seemed to fit perfectly, or as perfectly as things could when considering the time that had elapsed and the information that seemed to be available. I pinned my colours to the mast and decided that this must have been when Granddad was lost to his main dispersal unit back in 1943. I was wrong.

As a wonderful aside to this period in my research, I made contact with the family of Denny Sharp via Dale Hartle in New Zealand and we have exchanged information and photographs with each other. During my research I have made contact with so many different families and other like minded souls whose endeavour is to trace the stories of past loved ones. Each one has brought something new to my research table and I am extremely grateful to them all.

I continued with my search and began to close in on what I thought could be a possible scenario for my Granddad's fate back in 1943. Now armed with the MIA date of 18/04/1943, I began to re-read all the books and diaries once again.

The men of 5 Column that shared Arthur's MIA date were James Ambrose and William Robert Jordan. Both these men had featured regularly in my research and I had made contact with James's daughter Val in July 2009 and we had shared information and photos.

William Jordan had always interested me, as he had been briefly mentioned in Phil Chinnery's other book on the Chindits March or Die and had also been awarded the Military Medal for his time in Burma. The reason for his award still eludes me and his family to this day.

NB. On 31st October 2011, I spoke for the first time with the family of William Jordan, who had seen a post I had left on the Burma Star forum in 2009.

From Bernard Fergusson's book, Beyond the Chindwin:

Denny Sharp had bumped a patrol that very hour, two miles north of us (Fergusson's dispersal group). He had gone right-handed round Nanhkin and come back on to the track beyond it. One of his men had collapsed from exhaustion, they were giving him half an hour's rest to see if he would recover. It was during this period that the Japs came up the path and bumped their sentry.

The incident described above occurred on the 18th April and involved the dispersal group of 22 men (see photo above) led by Flight Lieutenant Denis Sharp, 5 Column's RAF Air Liaison officer. Everything seemed to fit perfectly, or as perfectly as things could when considering the time that had elapsed and the information that seemed to be available. I pinned my colours to the mast and decided that this must have been when Granddad was lost to his main dispersal unit back in 1943. I was wrong.

As a wonderful aside to this period in my research, I made contact with the family of Denny Sharp via Dale Hartle in New Zealand and we have exchanged information and photographs with each other. During my research I have made contact with so many different families and other like minded souls whose endeavour is to trace the stories of past loved ones. Each one has brought something new to my research table and I am extremely grateful to them all.

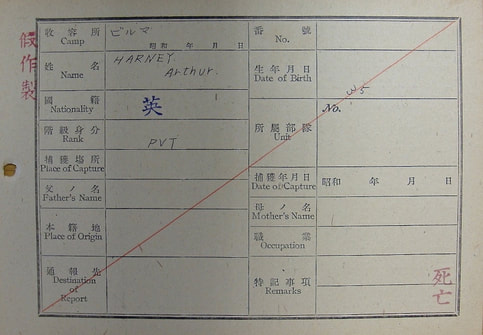

Lady luck struck again on 18th August 2010. On one of my many visits to the National Archives I had ordered Japanese index card box number 23. This was to seek out the card of Jack Hill, a British POW of the Japanese who had been captured in Java.

I went straight to the Hills section and had quickly found Jack's card putting it to one side and marking the place where I had extracted it from the box. I decided to then to search through the rest of the box. After about 10 minutes and around 100 cards later I had in my hands the card shown here to the right; it was my grandfather's card.

My hand was shaking and my eyes began to fill with tears, I scrutinized the detail on the card, which to be honest was not very much. Harney instead of Howney, but the correct christian name and age on the front of the card.

On the reverse my small knowledge of Japanese characters picked out the date of death, 19th June 1943, once again totally correct. While the details presented were scant and limited to say the least, I knew in my heart that we had found yet another piece of the jigsaw.

After having the card fully translated it told us that: Arthur had died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail at 3.15 pm on the 19th June 1943. His cause of death was stated as malnutrition and exhaustion and he was interred at Rangoon Cemetery, Burma.

Rangoon Cemetery was a reference to the old English Cantonment Cemetery, located to the east of the city, close to the Royal Lakes. So, it would seem that Granddad had died in reality from the trials and tribulations of being a Chindit in 5 Column in 1943, rather than by anything the Japanese had inflicted upon him during his short period of captivity. Column 5 had had the worst of records in receiving their rations from the RAF during Operation Longcloth, and took possession of only 20 days supply whilst being at large in Burma for over 80 days.

I went straight to the Hills section and had quickly found Jack's card putting it to one side and marking the place where I had extracted it from the box. I decided to then to search through the rest of the box. After about 10 minutes and around 100 cards later I had in my hands the card shown here to the right; it was my grandfather's card.

My hand was shaking and my eyes began to fill with tears, I scrutinized the detail on the card, which to be honest was not very much. Harney instead of Howney, but the correct christian name and age on the front of the card.

On the reverse my small knowledge of Japanese characters picked out the date of death, 19th June 1943, once again totally correct. While the details presented were scant and limited to say the least, I knew in my heart that we had found yet another piece of the jigsaw.

After having the card fully translated it told us that: Arthur had died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail at 3.15 pm on the 19th June 1943. His cause of death was stated as malnutrition and exhaustion and he was interred at Rangoon Cemetery, Burma.

Rangoon Cemetery was a reference to the old English Cantonment Cemetery, located to the east of the city, close to the Royal Lakes. So, it would seem that Granddad had died in reality from the trials and tribulations of being a Chindit in 5 Column in 1943, rather than by anything the Japanese had inflicted upon him during his short period of captivity. Column 5 had had the worst of records in receiving their rations from the RAF during Operation Longcloth, and took possession of only 20 days supply whilst being at large in Burma for over 80 days.

With the POW card finally translated, it seemed that all the information that could possibly be uncovered about Arthur Howney was now in my hands. We had travelled a very long road and it was quite incredible what we had found out in regards to an ordinary Private soldier and his time in Burma. But then in October 2010, I received a tip-off about a certain group of documents recently released at the National Archives. This included WO361/442, the Missing in Action Reports for the 13th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment in 1943. Thank you Peter!

Another emotional day at Kew provided me with four, yes four, pages of witness statements for Arthur and his dispersal group. The new information completely blew my previous theories apart as it became clear that Granddad had not been part of Denny Sharp's dispersal group, but was in a larger group of men from 5 Column, that had joined up with 7 Column and which then decided to make for the Chinese Yunnan border towards the north east.

5 Column had met its Waterloo in an engagement on the 29th March at a village called Hintha. Here, after a fierce fire-fight the column suffered many casualties and had eventually been forced to disperse in the practiced manner. It was during the march away from Hintha that the men of 5 Column became separated, some remaining with their Major, including Denny Sharp and the Support Platoon leader Tommy Roberts. As all the remaining columns began to congregate at the confluence of the two great obstacles that were the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers, the stragglers from 5 Column (around one hundred men) were taken in by Major Gilkes, the CO of 7 Column on Operation Longcloth.

NB. In a conversation with my Uncle on 17th December 2012, I discovered that Granddad had been a very strong and competent swimmer. We were chatting about the rivers in Burma and that Granddad had crossed them no fewer than four times. I had often wondered how he would have faired with these crossings, so with this new information to hand, presumably he took them in his stride. Neither my Nan, Mum or my Uncle were confident swimmers; it is strange how things work out.

After great deliberation with his fellow officers, Gilkes broke his unit up into dispersal parties of roughly 25-30 men in each. From the documents found in the MIA reports, Arthur Howney found himself under the charge of Burma Rifles officer, Lt. John Musgrave-Wood. It was decided that the group would make for the Chinese borders as this was the closest and shortest route away from the pursuing Japanese forces.

This decision, although made with the best of intentions and probably the correct one for the recently refitted and well fed members of 7 Column, was a disaster for the exhausted and hungry men of Column 5. And so in the early days of April these groups set forth toward their ultimate goal of Fort Hertz, the most northerly outpost of Burma still in Allied hands. Of the 25 men in Musgrave-Wood's party that set off from the Shweli River dispersal, only nine made it home to the United Kingdom after the war and three of these had to endure over two years imprisonment in Rangoon Jail. But what of Arthur Leslie Howney?

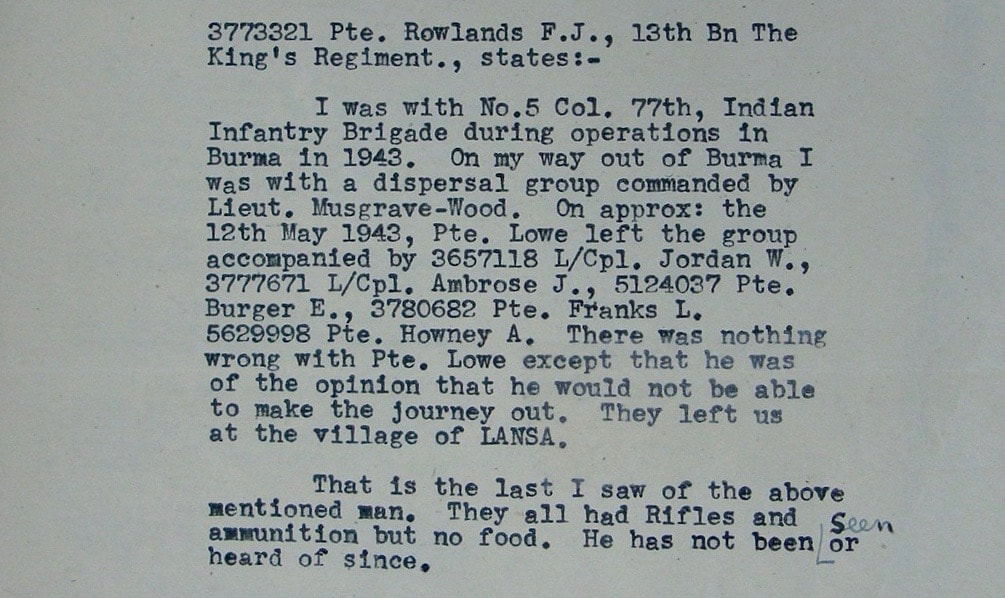

I was with a dispersal group commanded by Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood. On approximately the 12th May 1943 Pte. Lowe elected to leave our group, accompanied by, Lance Corporal Jordan, Lance Corporal Ambrose, Pte. Burger, Pte. Franks and Pte. Howney. They left us at the village of Lonsa.

This is a quote taken from the witness report of Private F.J. Rowlands of the King's Regiment as given by him to the Army enquiry officer in India on 14th July 1943. Another of his reports can be seen in the gallery below, replicating his account of the break off group listed above, but this time recording the village name as Lansa.

Another emotional day at Kew provided me with four, yes four, pages of witness statements for Arthur and his dispersal group. The new information completely blew my previous theories apart as it became clear that Granddad had not been part of Denny Sharp's dispersal group, but was in a larger group of men from 5 Column, that had joined up with 7 Column and which then decided to make for the Chinese Yunnan border towards the north east.

5 Column had met its Waterloo in an engagement on the 29th March at a village called Hintha. Here, after a fierce fire-fight the column suffered many casualties and had eventually been forced to disperse in the practiced manner. It was during the march away from Hintha that the men of 5 Column became separated, some remaining with their Major, including Denny Sharp and the Support Platoon leader Tommy Roberts. As all the remaining columns began to congregate at the confluence of the two great obstacles that were the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers, the stragglers from 5 Column (around one hundred men) were taken in by Major Gilkes, the CO of 7 Column on Operation Longcloth.

NB. In a conversation with my Uncle on 17th December 2012, I discovered that Granddad had been a very strong and competent swimmer. We were chatting about the rivers in Burma and that Granddad had crossed them no fewer than four times. I had often wondered how he would have faired with these crossings, so with this new information to hand, presumably he took them in his stride. Neither my Nan, Mum or my Uncle were confident swimmers; it is strange how things work out.

After great deliberation with his fellow officers, Gilkes broke his unit up into dispersal parties of roughly 25-30 men in each. From the documents found in the MIA reports, Arthur Howney found himself under the charge of Burma Rifles officer, Lt. John Musgrave-Wood. It was decided that the group would make for the Chinese borders as this was the closest and shortest route away from the pursuing Japanese forces.

This decision, although made with the best of intentions and probably the correct one for the recently refitted and well fed members of 7 Column, was a disaster for the exhausted and hungry men of Column 5. And so in the early days of April these groups set forth toward their ultimate goal of Fort Hertz, the most northerly outpost of Burma still in Allied hands. Of the 25 men in Musgrave-Wood's party that set off from the Shweli River dispersal, only nine made it home to the United Kingdom after the war and three of these had to endure over two years imprisonment in Rangoon Jail. But what of Arthur Leslie Howney?

I was with a dispersal group commanded by Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood. On approximately the 12th May 1943 Pte. Lowe elected to leave our group, accompanied by, Lance Corporal Jordan, Lance Corporal Ambrose, Pte. Burger, Pte. Franks and Pte. Howney. They left us at the village of Lonsa.

This is a quote taken from the witness report of Private F.J. Rowlands of the King's Regiment as given by him to the Army enquiry officer in India on 14th July 1943. Another of his reports can be seen in the gallery below, replicating his account of the break off group listed above, but this time recording the village name as Lansa.

In another of the reports found, Lt. Musgrave-Wood states that the group of six decided to remain at Lonsa, mostly it seems due to exhaustion and with the intention to rest for a while and then follow on after the main group had pushed on. From the reports it is known that the six were still free men on the 12th May, but it is unclear why Leon Frank, originally from 7 Column had joined up with the other five men who were all from Column 5. The natural leader of the group in terms of soldiering skill and experience should have been Fred Lowe, who had been part of the Guerilla Platoon and 142 Commando in 5 Column and would have come into the operation with more survival training than any of the other men. However, it would transpire that Lance Corporal William Jordan took up the lead role within the group as they resumed their march toward the Chinese borders.

The six were clearly in trouble; hungry, exhausted and probably now without rifles and ammunition as they moved from village to village in a desperate search for food and water. As mentioned earlier I had always been drawn to Ambrose and Jordan as playing some part in my Grandfather's ultimate story in Burma. I had placed my hopes on the Denny Sharp dispersal party from the pages of Beyond the Chindwin, but my hopes had been misplaced. Now, with the information from the witness statements in WO361/442 and the presence of Pte. Leon Frank in the dispersal group, a whole new avenue of research opened up in the form of Leon's anecdotal account, found in Phil Chinnery's book March or Die.

The six were clearly in trouble; hungry, exhausted and probably now without rifles and ammunition as they moved from village to village in a desperate search for food and water. As mentioned earlier I had always been drawn to Ambrose and Jordan as playing some part in my Grandfather's ultimate story in Burma. I had placed my hopes on the Denny Sharp dispersal party from the pages of Beyond the Chindwin, but my hopes had been misplaced. Now, with the information from the witness statements in WO361/442 and the presence of Pte. Leon Frank in the dispersal group, a whole new avenue of research opened up in the form of Leon's anecdotal account, found in Phil Chinnery's book March or Die.

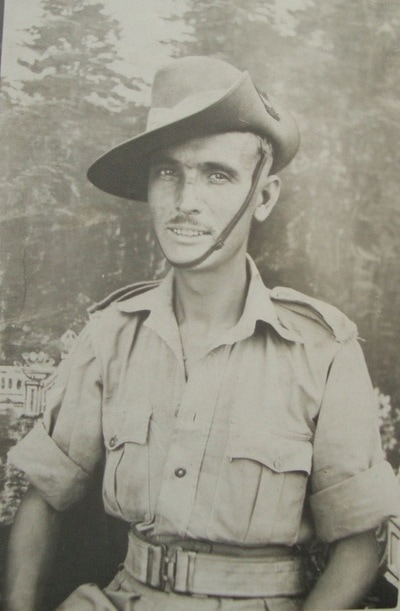

This is Leon Frank photographed at Secunderabad in India, probably during the summer of 1942. He was a diminutive man at only 5' 3'' tall, brought up in East London, the son of immigrant Jewish tailors who were originally from Eastern Europe. He had been with the 13th King's from the outset and had trained with the newly formed battalion at the Jordan Hill Barracks at Glasgow in June 1940.

After performing the ubiquitous coastal defence duties in 1941, he set sail with the battalion aboard the troopship Oronsay in December 1941, headed unbeknown at the time for India. Here the battalion settled into the Gough Barracks at Secunderabad and were used as garrison and policing units patrolling the streets of the city.

Leon was eventually placed into 7 Column under the command of Major Kenneth Gilkes and commenced Chindit training in the jungle scrubland of Patharia. I have listened to Leon's account of his time during WW2 from an archive sound recording he gave to the Imperial War Museum back in the 1990's.

To listen to his interview please follow this link: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80015277

He was a softly spoken and charming man who clearly had a need to talk about his time in Burma and to tell the tale of what happened to the men of the 13th King's in 1943. At times his account would be strained with sadness and emotion, as he remembered the more horrific moments of that time.

Leon sadly died in 2004, which means I missed him by 3 years, having began my own research in 2007. But to be honest, as with all things in relation to family genealogy, there is no point in wishing or hoping one had started earlier, or asked family members more questions, frustrating though that might be. We are who we are and we start our journey when we do for our own personal reasons, even if sometimes these are not openly apparent at the time.

And so to continue the story. Here in full, is Leon Frank's account of those last few days of freedom in May 1943. He would be the only man from the small group of six to survive their time as a prisoner of war and return home to his family in the UK. My very great thanks must go the author Phil Chinnery, for giving me permission to quote directly from his book March or Die:

I was in a group of thirty men under a Lieutenant from the Sherwood Foresters (Musgrave-Wood) and we decided to make our way northwards to Fort Hertz, which was still in British hands. The idea was that we would take some guides from a village, who could take us on to the next village, and so on. We did this successfully for a while, then we had these two guides that were leading us up a hill, towards a cross-shaped junction of tracks. suddenly one dived left and the other right and disappeared into the jungle. In front of us across the track was a Japanese patrol. Well, we just melted into the jungle either side, but the Japs had spotted us.

We hoped that if were quiet enough they would just go away, but one of our chaps (Dennett) looked up and for no apparent reason shouted 'Japs' and this gave our position away. They started to open fire on us, so we turned and rolled and scrambled down the hill. We did everything we could to put them off our tracks and eventually eluded them. We realised that our party was too large and an obvious target, so our Lieutenant told us it was every man for himself. Myself and five others, including Lance Corporal Jordan, decided to go east and try and get into China.

We became like bandits; we would go into villages and demand rice and food at gunpoint. We eventually came to a hillside with a hut on the side of it and a stream below and settled down to rest. Someone should have been on guard but we were very exhausted. Next thing we knew the door burst open and in came a Jap soldier with a fixed bayonet and stabbed Jordan in the hand. He was about to have another go when an officer called him off. We walked outside to find a half moon circle of Japanese soldiers with a machine-gun in the centre, pointed at us. I remember turning round and saying, "the bastards are going to shoot us in cold blood!"

Fortunately we had been captured by the Imperial Guard, who were professional soldiers. They tied our hands and led us to their camp. We were fed and given various jobs to do around the camp. I was made batman to one of the Japanese officers and had to sleep with five other Japanese batmen. One of the soldiers could speak English. He had been a barber in Tokyo and asked me to go to his hut for supper one night. He gave me some rice and kidneys to eat and invited me to go to Tokyo after the war and meet his family.

After about ten days we were put on a truck and sent to Maymyo. On the way we stopped at another jungle camp (probably Bhamo) and our escort left us in the hands of the camp's personnel. We were taken into a hut and made to kneel in the execution position with our hands tied behind our back. A big Japanese officer came in whirling his sword and we thought our time had come. However, it was just a sick joke.

When got to Maymyo we were beaten up by the Korean guards, who were just as bad as, if not worse than the Japanese. Eventually we were sent to Rangoon by train, crammed into cattle trucks for the three day trip. I remember when we stopped at Mandalay the door opened and we saw one of the big six foot Imperial guardsmen who had captured us. He went away and came back with a bunch of bananas which he gave to us. Our next stop was block number 6, Rangoon Jail. I was the only one of the six to survive.

After performing the ubiquitous coastal defence duties in 1941, he set sail with the battalion aboard the troopship Oronsay in December 1941, headed unbeknown at the time for India. Here the battalion settled into the Gough Barracks at Secunderabad and were used as garrison and policing units patrolling the streets of the city.

Leon was eventually placed into 7 Column under the command of Major Kenneth Gilkes and commenced Chindit training in the jungle scrubland of Patharia. I have listened to Leon's account of his time during WW2 from an archive sound recording he gave to the Imperial War Museum back in the 1990's.

To listen to his interview please follow this link: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80015277

He was a softly spoken and charming man who clearly had a need to talk about his time in Burma and to tell the tale of what happened to the men of the 13th King's in 1943. At times his account would be strained with sadness and emotion, as he remembered the more horrific moments of that time.

Leon sadly died in 2004, which means I missed him by 3 years, having began my own research in 2007. But to be honest, as with all things in relation to family genealogy, there is no point in wishing or hoping one had started earlier, or asked family members more questions, frustrating though that might be. We are who we are and we start our journey when we do for our own personal reasons, even if sometimes these are not openly apparent at the time.

And so to continue the story. Here in full, is Leon Frank's account of those last few days of freedom in May 1943. He would be the only man from the small group of six to survive their time as a prisoner of war and return home to his family in the UK. My very great thanks must go the author Phil Chinnery, for giving me permission to quote directly from his book March or Die:

I was in a group of thirty men under a Lieutenant from the Sherwood Foresters (Musgrave-Wood) and we decided to make our way northwards to Fort Hertz, which was still in British hands. The idea was that we would take some guides from a village, who could take us on to the next village, and so on. We did this successfully for a while, then we had these two guides that were leading us up a hill, towards a cross-shaped junction of tracks. suddenly one dived left and the other right and disappeared into the jungle. In front of us across the track was a Japanese patrol. Well, we just melted into the jungle either side, but the Japs had spotted us.

We hoped that if were quiet enough they would just go away, but one of our chaps (Dennett) looked up and for no apparent reason shouted 'Japs' and this gave our position away. They started to open fire on us, so we turned and rolled and scrambled down the hill. We did everything we could to put them off our tracks and eventually eluded them. We realised that our party was too large and an obvious target, so our Lieutenant told us it was every man for himself. Myself and five others, including Lance Corporal Jordan, decided to go east and try and get into China.

We became like bandits; we would go into villages and demand rice and food at gunpoint. We eventually came to a hillside with a hut on the side of it and a stream below and settled down to rest. Someone should have been on guard but we were very exhausted. Next thing we knew the door burst open and in came a Jap soldier with a fixed bayonet and stabbed Jordan in the hand. He was about to have another go when an officer called him off. We walked outside to find a half moon circle of Japanese soldiers with a machine-gun in the centre, pointed at us. I remember turning round and saying, "the bastards are going to shoot us in cold blood!"

Fortunately we had been captured by the Imperial Guard, who were professional soldiers. They tied our hands and led us to their camp. We were fed and given various jobs to do around the camp. I was made batman to one of the Japanese officers and had to sleep with five other Japanese batmen. One of the soldiers could speak English. He had been a barber in Tokyo and asked me to go to his hut for supper one night. He gave me some rice and kidneys to eat and invited me to go to Tokyo after the war and meet his family.

After about ten days we were put on a truck and sent to Maymyo. On the way we stopped at another jungle camp (probably Bhamo) and our escort left us in the hands of the camp's personnel. We were taken into a hut and made to kneel in the execution position with our hands tied behind our back. A big Japanese officer came in whirling his sword and we thought our time had come. However, it was just a sick joke.

When got to Maymyo we were beaten up by the Korean guards, who were just as bad as, if not worse than the Japanese. Eventually we were sent to Rangoon by train, crammed into cattle trucks for the three day trip. I remember when we stopped at Mandalay the door opened and we saw one of the big six foot Imperial guardsmen who had captured us. He went away and came back with a bunch of bananas which he gave to us. Our next stop was block number 6, Rangoon Jail. I was the only one of the six to survive.

Arthur Leslie Howney, India 1942.

Arthur Leslie Howney, India 1942.

So there we have the story so far. After receiving or stumbling upon each new piece of information or evidence in relation to Granddad's Burma story, I always feel there could not possibly be more to come.

When I sat up at the IWM research room listening to Leon Frank's sound recording, in my heart of hearts I knew he was unlikely to mention my Grandfather by name and even though the interviewer did press him to name the other five men, emotions overcame Leon and he moved away from the subject. To be fair to Leon, I do believe he could not remember or simply chose not to say in order to protect the families of those involved.

During my time searching for Granddad, he has always turned up last, or not found and even miss spelled in documentary evidence for his WW2 story. We have had no better luck with his civilian records either and true to form the latest piece of evidence I found continued this trend perfectly.

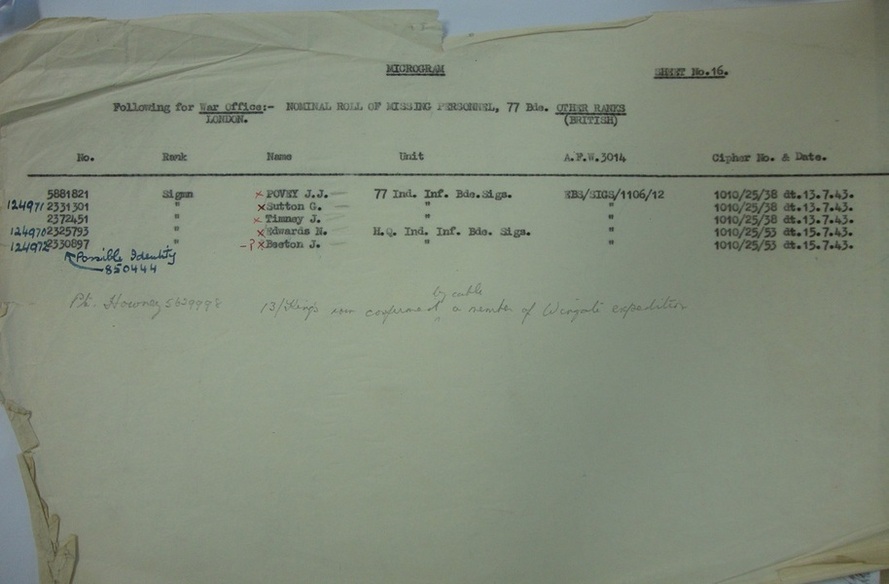

In February 2011, in the document WO361/436 (Missing in Action Reports for 77th Indian Infantry Brigade 1943) and once again at the National Archives, he turned up last of all on the list of the missing. The detail had been written in pencil (see below) onto the very last printed page of the roll for the missing men that year.

It simply states: Pte. Howney 5629998 13/King's now confirmed by cable a member of Wingate's expedition.

When I sat up at the IWM research room listening to Leon Frank's sound recording, in my heart of hearts I knew he was unlikely to mention my Grandfather by name and even though the interviewer did press him to name the other five men, emotions overcame Leon and he moved away from the subject. To be fair to Leon, I do believe he could not remember or simply chose not to say in order to protect the families of those involved.

During my time searching for Granddad, he has always turned up last, or not found and even miss spelled in documentary evidence for his WW2 story. We have had no better luck with his civilian records either and true to form the latest piece of evidence I found continued this trend perfectly.

In February 2011, in the document WO361/436 (Missing in Action Reports for 77th Indian Infantry Brigade 1943) and once again at the National Archives, he turned up last of all on the list of the missing. The detail had been written in pencil (see below) onto the very last printed page of the roll for the missing men that year.

It simply states: Pte. Howney 5629998 13/King's now confirmed by cable a member of Wingate's expedition.

Update 15/02/2012.

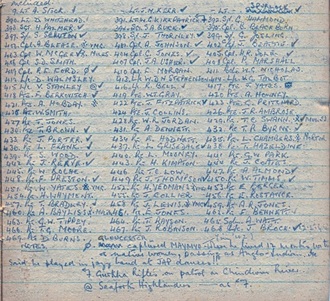

The document pictured to the left came into my possession in February 2012 (please click on the image to enlarge). It shows a list of Chindit POW's complete with their prisoner number alongside their name. It was a listing created by Captain H. Machin, who was attempting to collate the men from 77th Indian Infantry Brigade found to be present at Rangoon Jail.

Captain Machin was part of Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth and was present as an interrupter due to his fluency in speaking the Japanese language. He was captured by the Japanese during the dispersal in 1943 and was eventually taken to Singapore, where he was interrogated by the Kempai-Tai, the Japanese secret police. He was one of a small group of Chindits to be removed from Rangoon Jail in late May 1943 and was eventually liberated from Changi Prison Camp in mid-1945.

The list is of great importance to me, as it is the first time that my Grandfather is mentioned in any personal diary, memoir or book. It also clearly shows the soldier's POW number. One other point of interest is the presence of the the officers names above the three columns. It makes me wonder if Lieutenants Stock, Kerr and Spurlock were not in some way responsible for the men written beneath their names. The list runs in sequence of POW number across the page rather than down, separating the men in numerical rather than alphabetical order. The reason for this is unknown at present and could just be an idiosyncrasy of the time. You will also notice that the each column runs in rank order as the list progresses downwards.

As for the six men of Grandad's dispersal group, they are split across all three columns with Fred Lowe missing entirely from the list. The only non-Chindit to be found in the group is Cpl. Ford (Gloucesters) who seems to have been captured in the Maymyo area in 1943, having lived for over a year posing as a Burmese native. Patrick Flannigan Ford certainly survived his time in Rangoon Jail; however, whether he returned to Maymyo or his home town of Dublin after the war is unclear.

Update 08/08/2013.

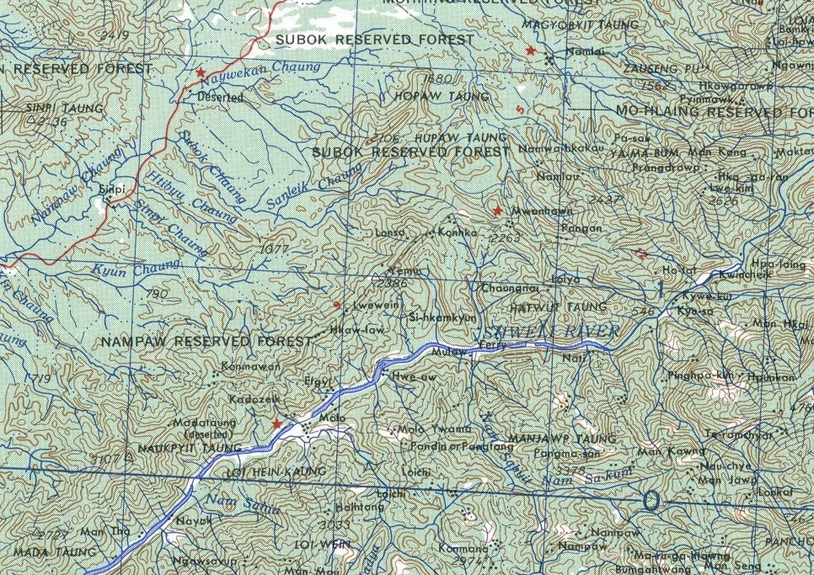

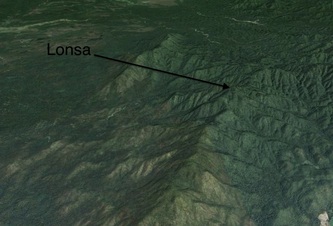

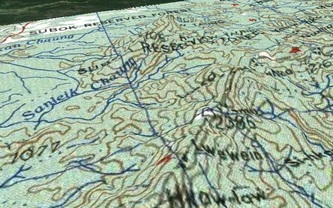

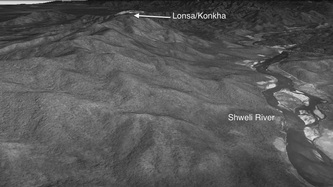

Whilst searching through some old maps, attempting to locate the movements of other Longcloth men, I stumbled across the village of Lonsa. This was the place name mentioned in the witness statements made by Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood and Pte. Rowlands and shown earlier in this story. The map location of this village has eluded me for nearly three years, so you can imagine the joy I experienced when I accidentally came across it. Of course I cannot be 100% certain that this is the exact place mentioned, especially as Burmese villages did tend to move around due to the employment of the 'crop-rotation' system; that being the exhaustion of the land over 3-5 years and then re-locating to a new site and beginning the process all over again.

Another consideration is that the spelling and pronunciation of Burmese place names by British soldiers could be notoriously poor, often writing examples down in a simplistic or phonetic fashion. Nevertheless, the village found on the map is in the area where the Chindits from Column 7 and their recently acquired comrades from Column 5 gathered in April 1943, close to the southern banks of the Shweli River.

Lonsa is positioned just north of the Shweli River, this means that Arthur and the other men did not make as much progress toward the Chinese borders as I first thought. The village is situated on high ground which keeps true to Leon Frank's account of their capture on a hillside. With the great help of my friend and cartographer, Matt Poole, I can now show several images of the village and its location, including super-imposed relief maps and overview satellite pictures. Lonsa has the approximate Latitude/Longitude co-ordinates of:

23 deg 26 min 56.36 sec North.

96 deg 55 min 09.66 sec East.

The document pictured to the left came into my possession in February 2012 (please click on the image to enlarge). It shows a list of Chindit POW's complete with their prisoner number alongside their name. It was a listing created by Captain H. Machin, who was attempting to collate the men from 77th Indian Infantry Brigade found to be present at Rangoon Jail.

Captain Machin was part of Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters on Operation Longcloth and was present as an interrupter due to his fluency in speaking the Japanese language. He was captured by the Japanese during the dispersal in 1943 and was eventually taken to Singapore, where he was interrogated by the Kempai-Tai, the Japanese secret police. He was one of a small group of Chindits to be removed from Rangoon Jail in late May 1943 and was eventually liberated from Changi Prison Camp in mid-1945.

The list is of great importance to me, as it is the first time that my Grandfather is mentioned in any personal diary, memoir or book. It also clearly shows the soldier's POW number. One other point of interest is the presence of the the officers names above the three columns. It makes me wonder if Lieutenants Stock, Kerr and Spurlock were not in some way responsible for the men written beneath their names. The list runs in sequence of POW number across the page rather than down, separating the men in numerical rather than alphabetical order. The reason for this is unknown at present and could just be an idiosyncrasy of the time. You will also notice that the each column runs in rank order as the list progresses downwards.

As for the six men of Grandad's dispersal group, they are split across all three columns with Fred Lowe missing entirely from the list. The only non-Chindit to be found in the group is Cpl. Ford (Gloucesters) who seems to have been captured in the Maymyo area in 1943, having lived for over a year posing as a Burmese native. Patrick Flannigan Ford certainly survived his time in Rangoon Jail; however, whether he returned to Maymyo or his home town of Dublin after the war is unclear.

Update 08/08/2013.

Whilst searching through some old maps, attempting to locate the movements of other Longcloth men, I stumbled across the village of Lonsa. This was the place name mentioned in the witness statements made by Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood and Pte. Rowlands and shown earlier in this story. The map location of this village has eluded me for nearly three years, so you can imagine the joy I experienced when I accidentally came across it. Of course I cannot be 100% certain that this is the exact place mentioned, especially as Burmese villages did tend to move around due to the employment of the 'crop-rotation' system; that being the exhaustion of the land over 3-5 years and then re-locating to a new site and beginning the process all over again.

Another consideration is that the spelling and pronunciation of Burmese place names by British soldiers could be notoriously poor, often writing examples down in a simplistic or phonetic fashion. Nevertheless, the village found on the map is in the area where the Chindits from Column 7 and their recently acquired comrades from Column 5 gathered in April 1943, close to the southern banks of the Shweli River.

Lonsa is positioned just north of the Shweli River, this means that Arthur and the other men did not make as much progress toward the Chinese borders as I first thought. The village is situated on high ground which keeps true to Leon Frank's account of their capture on a hillside. With the great help of my friend and cartographer, Matt Poole, I can now show several images of the village and its location, including super-imposed relief maps and overview satellite pictures. Lonsa has the approximate Latitude/Longitude co-ordinates of:

23 deg 26 min 56.36 sec North.

96 deg 55 min 09.66 sec East.

Update 04/09/2013.

With the help of Matt Poole and other members from the WW2Talk website, here are some more images from various maps of the village named Lonsa. We were waiting for site of the village upon a contemporary map from the time, Map 93 A/15, and WW2Talk member 'Charpoy Chindit' was good enough to oblige, thus confirming the village was present in the general location in 1942. Thanks also go to another WW2Talk member, 'Maureen', who provided us with a link to the 'Gazetter of Upper Burma and the Shan States' which lists Lonsa in its directory of place names. This is how it described the village of Lonsa in 1901:

LONCHA or LONSA. -- A Kachin village in Tract No. 9, Bhamo district, situated in 24 deg 19' north latitude and 97 deg 26' east longitude. In 1892 it contained thirty houses with a population of 104. The headman of the village has no others subordinate to him. The inhabitants are of the Lepai tribe and Kaori sub-tribe, and own three bullocks and two buffaloes.

For more in depth information on how we achieved this amount of detail, please click on the link below which will take you to the discussion thread on the WW2Talk website: ww2talk.com/index.php?threads/burma-map-93-a-15-and-93-a.49218/

With the help of Matt Poole and other members from the WW2Talk website, here are some more images from various maps of the village named Lonsa. We were waiting for site of the village upon a contemporary map from the time, Map 93 A/15, and WW2Talk member 'Charpoy Chindit' was good enough to oblige, thus confirming the village was present in the general location in 1942. Thanks also go to another WW2Talk member, 'Maureen', who provided us with a link to the 'Gazetter of Upper Burma and the Shan States' which lists Lonsa in its directory of place names. This is how it described the village of Lonsa in 1901:

LONCHA or LONSA. -- A Kachin village in Tract No. 9, Bhamo district, situated in 24 deg 19' north latitude and 97 deg 26' east longitude. In 1892 it contained thirty houses with a population of 104. The headman of the village has no others subordinate to him. The inhabitants are of the Lepai tribe and Kaori sub-tribe, and own three bullocks and two buffaloes.

For more in depth information on how we achieved this amount of detail, please click on the link below which will take you to the discussion thread on the WW2Talk website: ww2talk.com/index.php?threads/burma-map-93-a-15-and-93-a.49218/

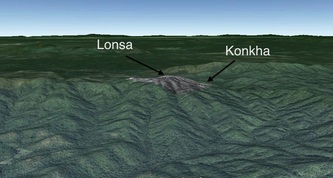

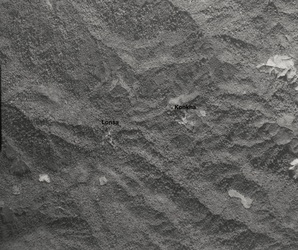

Update 02/10/2013.

With yet more help from the talented Matt Poole, a contemporary photographic image of the village of Lonsa has been sourced at the American National Archives (NARA). This came in the form of an aerial image of the locale taken on 2nd December 1944 by a sortie flown by the 24th Combat Mapping Squadron, USAAF. It shows that Lonsa was a very small village, perhaps comprising of no more than four of five buildings and two simple tracks leading in and out at either end.

One of the photographs also shows the neighbouring village of Konkha, situated slightly northeast of Lonsa as we view the image. Both villages sit astride hill ridge lines. The photographs were taken from an altitude of 22,000 feet.

Also shown in this section are modern annotated images using Google Earth to depict the villages of Lonsa and Konkha in 3D, with the 1944 positions draped onto the newer more up to date visual. It was no surprise to learn that neither village exists in its original WW2 location today.

With yet more help from the talented Matt Poole, a contemporary photographic image of the village of Lonsa has been sourced at the American National Archives (NARA). This came in the form of an aerial image of the locale taken on 2nd December 1944 by a sortie flown by the 24th Combat Mapping Squadron, USAAF. It shows that Lonsa was a very small village, perhaps comprising of no more than four of five buildings and two simple tracks leading in and out at either end.

One of the photographs also shows the neighbouring village of Konkha, situated slightly northeast of Lonsa as we view the image. Both villages sit astride hill ridge lines. The photographs were taken from an altitude of 22,000 feet.

Also shown in this section are modern annotated images using Google Earth to depict the villages of Lonsa and Konkha in 3D, with the 1944 positions draped onto the newer more up to date visual. It was no surprise to learn that neither village exists in its original WW2 location today.

Update 28/12/2013.

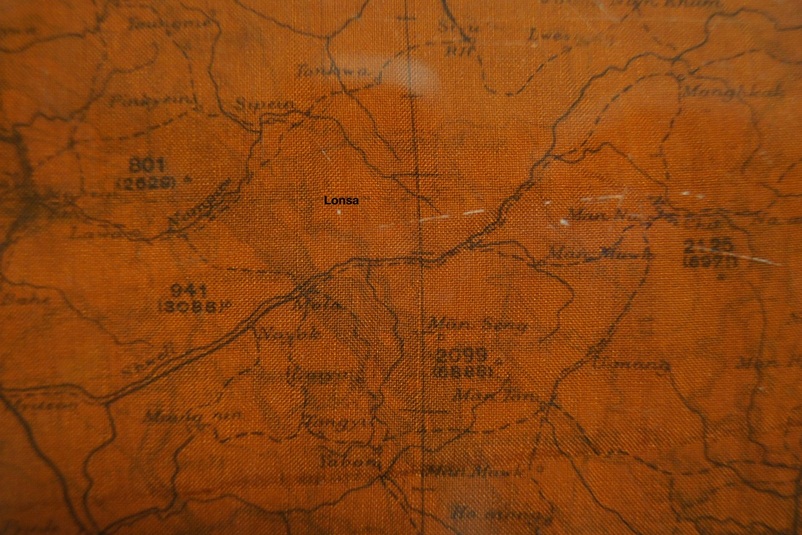

I am extremely grateful to John Griffett for sending me the map image seen below. It is taken from the RAF 'escape map' belonging to RCAF Pilot David Bockus DFC, who flew L-5 rescue planes in and out of the Chindit landing strip codenamed 'Broadway' in 1944. The L-5 plane was used extensively in the second Chindit operation to remove casualties from forward areas, returning them to base hospitals and clearing stations back in India.

These maps were issued to Chindit personnel during both operations in Burma and were used as a basic guides when exiting the country having been lost or shot down. Of larger scale and lacking in any real detail, any man who succeeded in reaching Allied held territory using these maps alone had performed very well indeed. I have added Lonsa to the map in order to give an idea of the distance between the Shweli River and the village.

I am extremely grateful to John Griffett for sending me the map image seen below. It is taken from the RAF 'escape map' belonging to RCAF Pilot David Bockus DFC, who flew L-5 rescue planes in and out of the Chindit landing strip codenamed 'Broadway' in 1944. The L-5 plane was used extensively in the second Chindit operation to remove casualties from forward areas, returning them to base hospitals and clearing stations back in India.

These maps were issued to Chindit personnel during both operations in Burma and were used as a basic guides when exiting the country having been lost or shot down. Of larger scale and lacking in any real detail, any man who succeeded in reaching Allied held territory using these maps alone had performed very well indeed. I have added Lonsa to the map in order to give an idea of the distance between the Shweli River and the village.

Update 12/05/2016.

To further illustrate this story, seen below are some general images of the Shweli River and the landscape slightly north of the Wingaba Cliffs, close to where 8 Column attempted their first crossing on 1st April 1943. Arthur Howney and the other detached souls from 5 Column, met up with Major Gilkes and his men some 10 miles further south of this point. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

To further illustrate this story, seen below are some general images of the Shweli River and the landscape slightly north of the Wingaba Cliffs, close to where 8 Column attempted their first crossing on 1st April 1943. Arthur Howney and the other detached souls from 5 Column, met up with Major Gilkes and his men some 10 miles further south of this point. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 02/05/2017.

I recently stumbled upon a photograph of Pte. Fred Lowe, from a newspaper article published in the Manchester Evening News dated 22nd July 1943 under the headline: Prisoners in the Indian Theatre. This now means I possess a photograph of all the men from the small dispersal group of six soldiers captured alongside my grandfather, except for an image of Pte. Edgar Burger. Seen below is a Gallery showing all of the men involved and including an image of the officer in charge of their original dispersal group, Lt. Jon Musgrave-Wood of the Sherwood Foresters. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I recently stumbled upon a photograph of Pte. Fred Lowe, from a newspaper article published in the Manchester Evening News dated 22nd July 1943 under the headline: Prisoners in the Indian Theatre. This now means I possess a photograph of all the men from the small dispersal group of six soldiers captured alongside my grandfather, except for an image of Pte. Edgar Burger. Seen below is a Gallery showing all of the men involved and including an image of the officer in charge of their original dispersal group, Lt. Jon Musgrave-Wood of the Sherwood Foresters. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2011/2013. Most of the green background, detailed maps used on this website are Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin, USA.