Family Pages 3

Christine and Dawn, nieces of Stephen Hector

Sometime late last year (2010) I was reading through some back issues of the Burma Star Association magazine, Dekho. Hidden amongst the pages of these were five requests for information about men who were lost during Wingate’s first Chindit operation in 1943. The Hector family were one of these five and had placed their enquiry in 2005; I decided to reply in the hope that they were still interested and looking for information.

I had always been drawn to Lieutenant Hector and the part he had played in the attempt to get a party of already sick and wounded men back to the safety of India. It also helped of course that to my knowledge he was the only man named Stephen to take part in operation Longcloth.

As my research progressed Lieutenant Hector's story began to materialise and the degree of his bravery become apparent. In brief, he along with three other young officers, had agreed to lead a group of men who were already suffering from the ravages of the operation, back to the Assam borders. Sadly, only four of the dispersal party ever reached the safety of India again, with three of these spending nearly two years in Rangoon Jail.

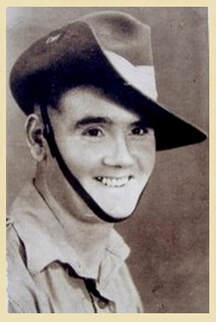

Pictured left is possibly the last photograph ever taken of the young officer, a short time before he ventured into Burma in February 1943. The copy of the photograph was kindly sent to me by Christine Stanton, one of Stephen's nieces. It is part of some wonderful paperwork and information that she and her cousin Dawn Holt have sent to me over the past year, all the result of that family enquiry in Dekho magazine in 2005.

I had always been drawn to Lieutenant Hector and the part he had played in the attempt to get a party of already sick and wounded men back to the safety of India. It also helped of course that to my knowledge he was the only man named Stephen to take part in operation Longcloth.

As my research progressed Lieutenant Hector's story began to materialise and the degree of his bravery become apparent. In brief, he along with three other young officers, had agreed to lead a group of men who were already suffering from the ravages of the operation, back to the Assam borders. Sadly, only four of the dispersal party ever reached the safety of India again, with three of these spending nearly two years in Rangoon Jail.

Pictured left is possibly the last photograph ever taken of the young officer, a short time before he ventured into Burma in February 1943. The copy of the photograph was kindly sent to me by Christine Stanton, one of Stephen's nieces. It is part of some wonderful paperwork and information that she and her cousin Dawn Holt have sent to me over the past year, all the result of that family enquiry in Dekho magazine in 2005.

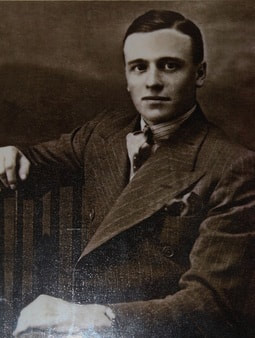

Here is what his own family have to say about Stephen Hector, a brother and uncle who was dearly loved. (Pictured right, is Stephen at a family wedding in the late 1930's).

Stephen Frederick Hector 1915-1943

Stephen Frederick Hector was born in Poplar, East London in 1915; one of the five boys and two girls born to Ellen and William Boyne Hector. Stephen was a gifted pupil at Culloden Street School and rose to become School Captain. When he left at the age of fourteen he decided to attend night school to study law for a further two years.

For employment, Stephen became a messenger for a firm of stockbrokers, Burt Taylor Ltd and quickly developed a flair for share dealing and a capacity to earn well from his efforts. As well as being shrewd he was also courteous and truthful in all his business dealings, this coupled with a gentle manner and dashing good looks, he was well respected by all who knew him.

Always smartly dressed he joined the Young Conservatives (a first for the family) and spent many hours at their meeting room developing his skills at billiards, becoming a very good player. Steve met Ivy Taylor, a pretty girl with an outgoing personality who worked at the local estate agents; she was to become the love of his life.

With the prospect of war edging nearer, Steve decided to join the Special Police Force stationed at Limehouse and when he eventually received his call up papers he was told he would join the South Wales Borderers. Before long Stephen was selected as Officer material and sent to the Officer Training Unit at Sandhurst, passing out as a 2nd Lieutenant much to the admiration and pride of his family. Steve and Ivy married and went to live with Ivy’s parents in Hemel Hempstead.

Stephen was posted abroard towards the middle of 1942, sailing to India. Here his original unit was posted to the 13th Kings Regiment (Liverpool) and would ultimately join operation Longcloth. Stephen was now a Lieutenant and in his letters sent to youngest brother John, with whom he shared regular contact, he describes the harsh training routines as almost a pleasure after the long periods of inactivity on board ship. Although, after the third route march in monsoon conditions he felt the training more than adequate.

In a letter to John dated September 16th 1942 from his Transit Camp base at Deolali, Stephen writes that he has taken to learning Urdu, but managed only a few phrases after struggling with his concentration at the difficult grammar, he decided to postpone the course when he knew he was joining a British Unit. He also wrote how good it was to receive letters from home and how all the family letters posted that May had all arrived together in September.

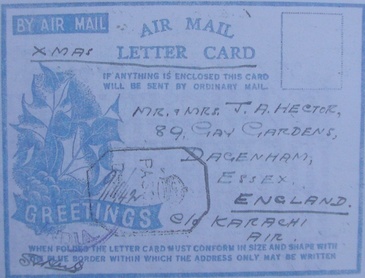

By January 1943 Steve wrote from the ‘Air Base Postal Depot’ in Karachi and other addresses, as security tightened over the whereabouts of Chindit training camps. He apologises for not being able to tell more of the Unit’s activities, but is pleased to report he has received rations of tobacco and ‘Naval quality’ rum. This postcard was to be the last that brother John received. It was dated Tuesday 2nd February 1943 and his closing sentences to his brother read as follows: “News certainly sounds good these days I hope it keeps up. Cheerio. Love to all, Steve."

John tried to piece together what had happened to his favourite brother after the news came, devastating the family, that Stephen was missing in April 1943. John tried, unsuccessfully, to find exact information regarding that fateful mission and was given a lot of confusing and untrue stories. John wrote to several of Stephen’s friends to ask if they had seen him on their travels, but to no avail, and because of the difficult fighting terrain the information John was given was either sketchy or inaccurate. One or two whom John contacted refused to talk about their experiences, highlighting just how bad the situation must have been for his dear brother.

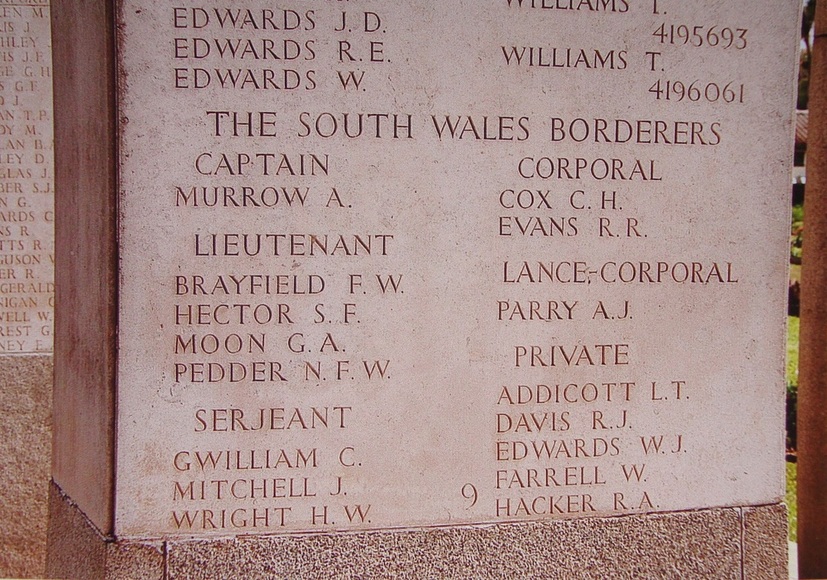

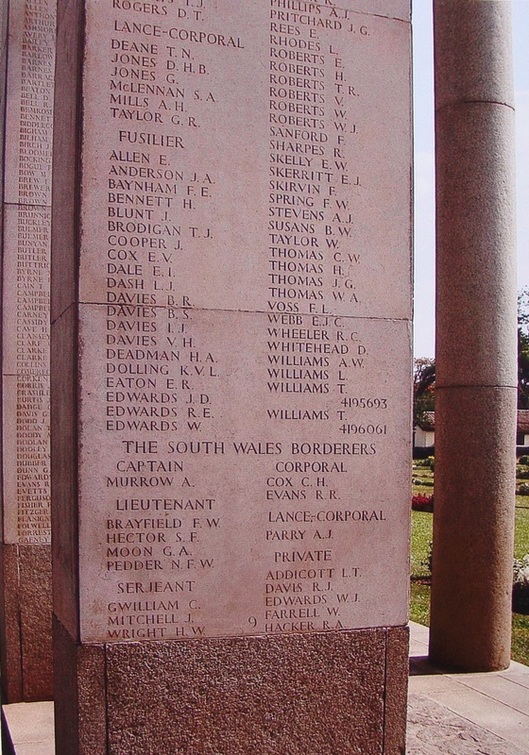

Dejected and saddened the only comfort John gained latterly was via the War Office granting him, as next of kin, Stephen’s posthumous medals. He also received a notification from the Burma Star Association informing him that Stephen’s name would be on the Roll of Honour, Face 9 of the Rangoon Memorial, situated in the grounds of Taukkyan War Cemetery.

Stephen’s niece, Dawn Holt, remembers her favourite Uncle’s lovely smile and as being kind, fun loving and very good looking. Steve’s mother Ellen (Dawn’s grandmother), died from cancer in 1939 and it fell to Dawn’s mother Ann, as eldest girl, to keep the family together. On his visits Stephen always had time for Dawn, taking her to Lyon’s Corner House for more cream cakes than she could eat and to local fairs, from where she would return laden with prizes and dolls. To this day Dawn finds it hard to believe that such a lovely young man was so cruelly taken from their close knit family.

Stephen F. Hector was 28 when he died on 11th April 1943, killed in the action of defending his injured colleagues of Dispersal Group 4, Column 7. A selfless and heroic act.

It is with grateful thanks that the remaining family of Stephen Hector acknowledge the hard work and diligence of Steve Fogden in setting up this valuable website. Without his investigations we would never have known the full story. This was the closure that his devoted brother sought, but sadly died without ever knowing.

Written by: Christine Stanton nee Hector (John’s daughter and niece of Stephen) and Dawn Holt, (daughter of Stephen’s sister Ann).

Stephen Frederick Hector 1915-1943

Stephen Frederick Hector was born in Poplar, East London in 1915; one of the five boys and two girls born to Ellen and William Boyne Hector. Stephen was a gifted pupil at Culloden Street School and rose to become School Captain. When he left at the age of fourteen he decided to attend night school to study law for a further two years.

For employment, Stephen became a messenger for a firm of stockbrokers, Burt Taylor Ltd and quickly developed a flair for share dealing and a capacity to earn well from his efforts. As well as being shrewd he was also courteous and truthful in all his business dealings, this coupled with a gentle manner and dashing good looks, he was well respected by all who knew him.

Always smartly dressed he joined the Young Conservatives (a first for the family) and spent many hours at their meeting room developing his skills at billiards, becoming a very good player. Steve met Ivy Taylor, a pretty girl with an outgoing personality who worked at the local estate agents; she was to become the love of his life.

With the prospect of war edging nearer, Steve decided to join the Special Police Force stationed at Limehouse and when he eventually received his call up papers he was told he would join the South Wales Borderers. Before long Stephen was selected as Officer material and sent to the Officer Training Unit at Sandhurst, passing out as a 2nd Lieutenant much to the admiration and pride of his family. Steve and Ivy married and went to live with Ivy’s parents in Hemel Hempstead.

Stephen was posted abroard towards the middle of 1942, sailing to India. Here his original unit was posted to the 13th Kings Regiment (Liverpool) and would ultimately join operation Longcloth. Stephen was now a Lieutenant and in his letters sent to youngest brother John, with whom he shared regular contact, he describes the harsh training routines as almost a pleasure after the long periods of inactivity on board ship. Although, after the third route march in monsoon conditions he felt the training more than adequate.

In a letter to John dated September 16th 1942 from his Transit Camp base at Deolali, Stephen writes that he has taken to learning Urdu, but managed only a few phrases after struggling with his concentration at the difficult grammar, he decided to postpone the course when he knew he was joining a British Unit. He also wrote how good it was to receive letters from home and how all the family letters posted that May had all arrived together in September.

By January 1943 Steve wrote from the ‘Air Base Postal Depot’ in Karachi and other addresses, as security tightened over the whereabouts of Chindit training camps. He apologises for not being able to tell more of the Unit’s activities, but is pleased to report he has received rations of tobacco and ‘Naval quality’ rum. This postcard was to be the last that brother John received. It was dated Tuesday 2nd February 1943 and his closing sentences to his brother read as follows: “News certainly sounds good these days I hope it keeps up. Cheerio. Love to all, Steve."

John tried to piece together what had happened to his favourite brother after the news came, devastating the family, that Stephen was missing in April 1943. John tried, unsuccessfully, to find exact information regarding that fateful mission and was given a lot of confusing and untrue stories. John wrote to several of Stephen’s friends to ask if they had seen him on their travels, but to no avail, and because of the difficult fighting terrain the information John was given was either sketchy or inaccurate. One or two whom John contacted refused to talk about their experiences, highlighting just how bad the situation must have been for his dear brother.

Dejected and saddened the only comfort John gained latterly was via the War Office granting him, as next of kin, Stephen’s posthumous medals. He also received a notification from the Burma Star Association informing him that Stephen’s name would be on the Roll of Honour, Face 9 of the Rangoon Memorial, situated in the grounds of Taukkyan War Cemetery.

Stephen’s niece, Dawn Holt, remembers her favourite Uncle’s lovely smile and as being kind, fun loving and very good looking. Steve’s mother Ellen (Dawn’s grandmother), died from cancer in 1939 and it fell to Dawn’s mother Ann, as eldest girl, to keep the family together. On his visits Stephen always had time for Dawn, taking her to Lyon’s Corner House for more cream cakes than she could eat and to local fairs, from where she would return laden with prizes and dolls. To this day Dawn finds it hard to believe that such a lovely young man was so cruelly taken from their close knit family.

Stephen F. Hector was 28 when he died on 11th April 1943, killed in the action of defending his injured colleagues of Dispersal Group 4, Column 7. A selfless and heroic act.

It is with grateful thanks that the remaining family of Stephen Hector acknowledge the hard work and diligence of Steve Fogden in setting up this valuable website. Without his investigations we would never have known the full story. This was the closure that his devoted brother sought, but sadly died without ever knowing.

Written by: Christine Stanton nee Hector (John’s daughter and niece of Stephen) and Dawn Holt, (daughter of Stephen’s sister Ann).

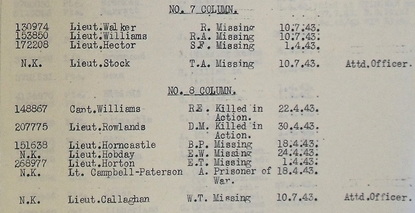

Seen above are two images concerning Lieutenant Hector. The first is part of the Officers Missing in Action list found in the 13th Kings War Diary for 1943. It clearly shows three of the four officers (Walker, Williams and Hector) who attempted to take those unfortunate soldiers back to India in April 1943. Stephen's date of April 1st would have been the last time the senior officer could place his whereabouts, as column 7 and the other men prepared to break down into smaller dispersal units. Ralph Williams and Rex Walker's dates are much later because both men had become POW's to the Japanese and were to end up at Rangoon Jail, where, sadly, both perished in mid-1943.

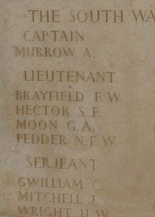

The other image (right) is Stephen Hector's inscription on the Rangoon Memorial. You will notice that his name was placed onto the panel that included the men lost from the South Wales Borderers, which was Stephen's original Army Regiment. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page. Here are his details from the CWGC: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2511297/stephen-frederick-hector/

The full story of the ill-fated dispersal party led by Rex Walker and Stephen Hector can be found and read by clicking on the link below:

Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

I was lucky enough to speak with Dawn on the telephone once or twice. She had told me that the family had sent Stephen a large parcel for his birthday in 1943, everyone in the family had contributed, there was a lovely cake, other presents including knitted items as well as all their good wishes. The parcel was returned to the family unopened, which obviously caused great upset to them all.

She also told me of how she had pictured many scenarios of how Stephen might have died that year. In her own words:

They were all quite horrific; at the hands of his Japanese captors, or from some ghastly disease, or worse still, all alone in the jungle. So when I found out he had been killed in action, with his comrades, simply doing his job, it seemed the most comforting outcome I could hope for.

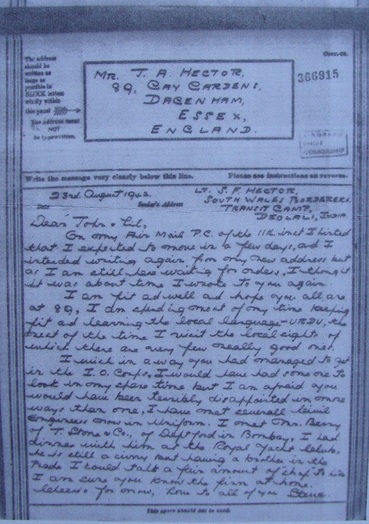

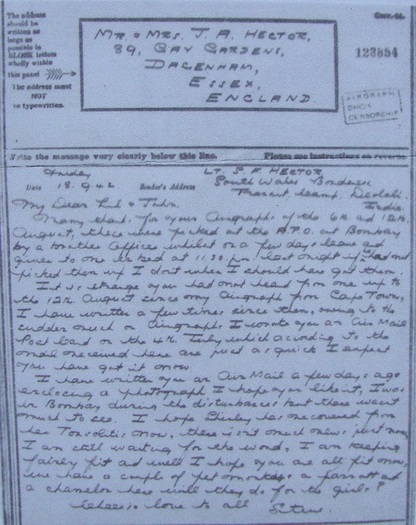

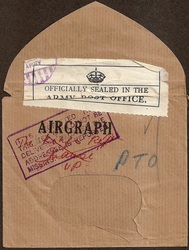

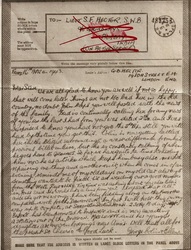

One of the most fortuitous things to occur from my contact with the Hector family was to finally see the different types of Army correspondence that were used by soldiers back in 1942-43. Seen below are some of the different types of postal options available to the soldiers at that time.

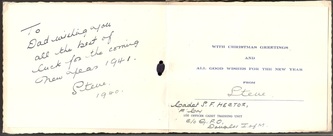

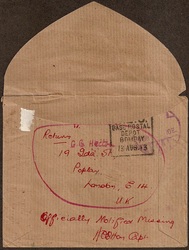

The top two images are the standard Airgraph letter. All correspondence would have been heavily censored by the Army during this period, removing any script which might give away or inform the enemy of pending military positions or plans, before continuing it's journey homeward to the UK. Delivery times improved as the tide of the war began to swing in favour of the Allied Forces.

The other two examples are the picture type lettercard (shown here, bottom left, with the Greeting for Christmas 1942) and the ordinary postcard seen to the right. This is the card that Christine mentions in the family story above as being the final message that Stephen sent home in February 1943.

The other image (right) is Stephen Hector's inscription on the Rangoon Memorial. You will notice that his name was placed onto the panel that included the men lost from the South Wales Borderers, which was Stephen's original Army Regiment. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page. Here are his details from the CWGC: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2511297/stephen-frederick-hector/

The full story of the ill-fated dispersal party led by Rex Walker and Stephen Hector can be found and read by clicking on the link below:

Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

I was lucky enough to speak with Dawn on the telephone once or twice. She had told me that the family had sent Stephen a large parcel for his birthday in 1943, everyone in the family had contributed, there was a lovely cake, other presents including knitted items as well as all their good wishes. The parcel was returned to the family unopened, which obviously caused great upset to them all.

She also told me of how she had pictured many scenarios of how Stephen might have died that year. In her own words:

They were all quite horrific; at the hands of his Japanese captors, or from some ghastly disease, or worse still, all alone in the jungle. So when I found out he had been killed in action, with his comrades, simply doing his job, it seemed the most comforting outcome I could hope for.

One of the most fortuitous things to occur from my contact with the Hector family was to finally see the different types of Army correspondence that were used by soldiers back in 1942-43. Seen below are some of the different types of postal options available to the soldiers at that time.

The top two images are the standard Airgraph letter. All correspondence would have been heavily censored by the Army during this period, removing any script which might give away or inform the enemy of pending military positions or plans, before continuing it's journey homeward to the UK. Delivery times improved as the tide of the war began to swing in favour of the Allied Forces.

The other two examples are the picture type lettercard (shown here, bottom left, with the Greeting for Christmas 1942) and the ordinary postcard seen to the right. This is the card that Christine mentions in the family story above as being the final message that Stephen sent home in February 1943.

I would like to thank Christine and Dawn for their wonderful help in compiling the story of a very brave and selfless man. I wish to dedicate this page not only to Lieutenant Stephen Frederick Hector, but to all his family, especially his youngest brother John and his sister Ann.

Update 25/07/2012

Following a trip to Burma by a family friend, shown below are some more recent photos of Stephen's inscription on the Rangoon Memorial.

Update 25/07/2012

Following a trip to Burma by a family friend, shown below are some more recent photos of Stephen's inscription on the Rangoon Memorial.

Lt. S. Hector. Seen in October 1942.

Update 21/09/2013.

Earlier in the year (April 2013) I received a contact email via this website from Paul Stephen Hector. Paul is the son of Lieutenant Steve Hector's eldest brother, George. Paul informed me that he was proud to have been named after Stephen Hector and had made a serious attempt to research his namesake in regards to his Burma and more general WW2 story. Paul sent me his contribution with this message:

Steve, well I have finally got around to putting a few words together. Please use as you see fit and include as many pictures as you wish from those I sent over. If you need anything else please do not hesitate to ask. Seventy years-so long but no time at all.

Here is the information that Paul has added to the story of Stephen Hector. It is based on his own research and the documents kept by his own father, George. The new content includes a two page letter written by Paul's uncle John Hector. This letter was sent by John to his own father and contains the information he had discovered in regard to Lt. Hector's disappearance in the jungles of Burma in April 1943.

STEPHEN FREDERICK HECTOR (SEVENTY YEARS- SO LONG BUT NO TIME AT ALL).

Steve’s story has been covered in some detail in the pages on this website, but there are a few more things to add, a few mistakes to be clarified and a few more speculations to consider that make the story even more remarkable.

Stephen was born at 19 Ida Street, Poplar on the 18th May 1915 in the middle of a Zeppelin raid. He was the sixth surviving child of the seven to achieve adulthood and the fifth of the six boys born to William Boyne Hector and Ellen Maud Gaster. I am the younger son of George Boyne Hector the oldest brother in a family of seven children who survived beyond infancy. Steve joined the South Wales Borderers, probably in the summer of 1940 as an Officer Cadet and joined A Company on the Isle of Man for basic training. He returned home in August 1940 to marry Ivy Taylor and went to live with Ivy’s parents in Hemel Hempstead.

He received his ‘Emergency Commission’ as 2nd Lieutenant on 15th February 1941 (he did not attend Sandhurst, a family myth, as Sandhurst was closed for much of the War) and by April 1941 he was based at Stockton-on-Tees in North East England with the 7th Battalion SWB’s and by Christmas 1941 was based at Hadrian’s Camp near Carlisle in North West England.

His last visit home was in April/May 1942, by which time the War was in a critical state on all fronts and it was decided that the SWB’s and some other units were to go on attachment to the 13th King's Liverpool Regiment who had shipped out to India for defensive duties in December 1941.

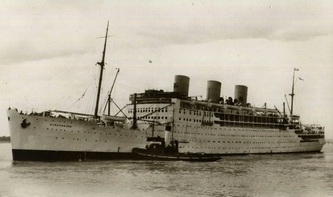

Steve left the UK with his unit on board the P&O Liner 'Strahaird', as part of WS (Winston’s Specials) Convoy 19 from the Clyde on the 11th May 1942 arriving in Durban, South Africa, on 9th June 1942.

The convoy split in two here, one part heading north for Suez and the other which was to cross the Indian Ocean, left on 16th June and arrived in Bombay, India on the 1st July. The SWB were then transferred to Deolali about 100 miles North East of Bombay. It was here that the men started their intensive jungle warfare training intended to weed out the weakest among them and also where Steve was promoted 1st Lieutenant on 15th August 1942.

From his letters we know he was in Deolali until December when he was moved up to Imphal in North East India on the border with Burma as the very last replacements for the 77th Infantry Brigade, the Chindits. Imphal became the base for the launch of Operation Longcloth under Orde Wingate.

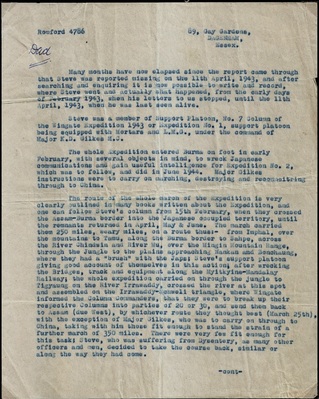

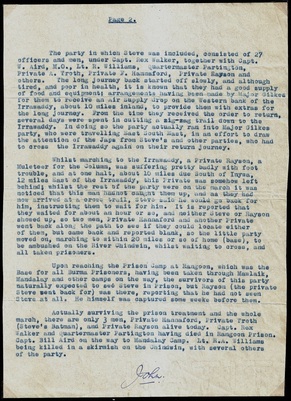

The story of the campaign has been covered in detail elsewhere, but I wish to pick up the story in detail in early April, when the decision to retreat was made and ‘Dispersal Group 4’ was further split under Lieutenant Walker with Captain Aird and Lieutenant’s Hector and Anderson-Williams. The fate of this group is also covered in some detail on this website, but there is an interesting family document compiled by John Hector soon after the end of the War which tells the story of the 10th and 11th April 1943. It is probably best simply to read the original document.

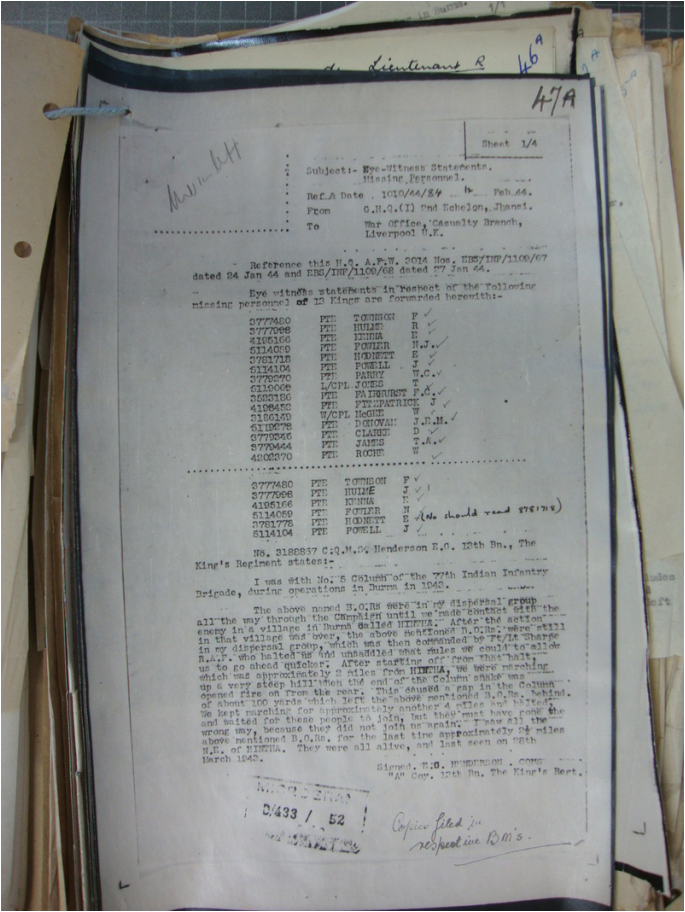

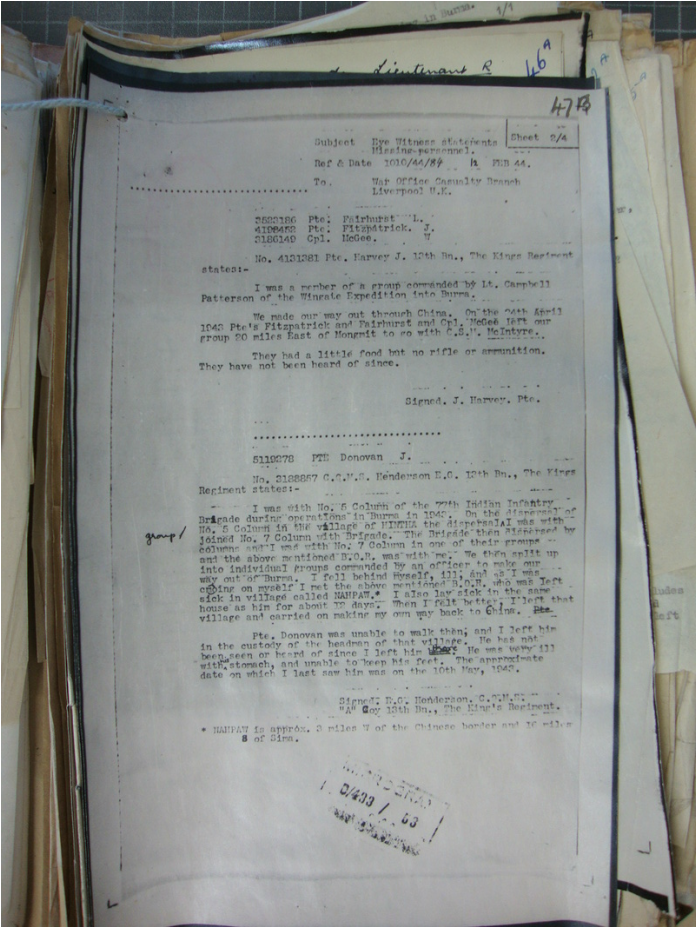

Seen below is the letter in question, it is a remarkable document in many ways, but perhaps most of all it is a testament to the incredible effort that John Hector made to find out what had happened to his dear brother back in 1943. Please click on the images to enlarge.

Earlier in the year (April 2013) I received a contact email via this website from Paul Stephen Hector. Paul is the son of Lieutenant Steve Hector's eldest brother, George. Paul informed me that he was proud to have been named after Stephen Hector and had made a serious attempt to research his namesake in regards to his Burma and more general WW2 story. Paul sent me his contribution with this message:

Steve, well I have finally got around to putting a few words together. Please use as you see fit and include as many pictures as you wish from those I sent over. If you need anything else please do not hesitate to ask. Seventy years-so long but no time at all.

Here is the information that Paul has added to the story of Stephen Hector. It is based on his own research and the documents kept by his own father, George. The new content includes a two page letter written by Paul's uncle John Hector. This letter was sent by John to his own father and contains the information he had discovered in regard to Lt. Hector's disappearance in the jungles of Burma in April 1943.

STEPHEN FREDERICK HECTOR (SEVENTY YEARS- SO LONG BUT NO TIME AT ALL).

Steve’s story has been covered in some detail in the pages on this website, but there are a few more things to add, a few mistakes to be clarified and a few more speculations to consider that make the story even more remarkable.

Stephen was born at 19 Ida Street, Poplar on the 18th May 1915 in the middle of a Zeppelin raid. He was the sixth surviving child of the seven to achieve adulthood and the fifth of the six boys born to William Boyne Hector and Ellen Maud Gaster. I am the younger son of George Boyne Hector the oldest brother in a family of seven children who survived beyond infancy. Steve joined the South Wales Borderers, probably in the summer of 1940 as an Officer Cadet and joined A Company on the Isle of Man for basic training. He returned home in August 1940 to marry Ivy Taylor and went to live with Ivy’s parents in Hemel Hempstead.

He received his ‘Emergency Commission’ as 2nd Lieutenant on 15th February 1941 (he did not attend Sandhurst, a family myth, as Sandhurst was closed for much of the War) and by April 1941 he was based at Stockton-on-Tees in North East England with the 7th Battalion SWB’s and by Christmas 1941 was based at Hadrian’s Camp near Carlisle in North West England.

His last visit home was in April/May 1942, by which time the War was in a critical state on all fronts and it was decided that the SWB’s and some other units were to go on attachment to the 13th King's Liverpool Regiment who had shipped out to India for defensive duties in December 1941.

Steve left the UK with his unit on board the P&O Liner 'Strahaird', as part of WS (Winston’s Specials) Convoy 19 from the Clyde on the 11th May 1942 arriving in Durban, South Africa, on 9th June 1942.

The convoy split in two here, one part heading north for Suez and the other which was to cross the Indian Ocean, left on 16th June and arrived in Bombay, India on the 1st July. The SWB were then transferred to Deolali about 100 miles North East of Bombay. It was here that the men started their intensive jungle warfare training intended to weed out the weakest among them and also where Steve was promoted 1st Lieutenant on 15th August 1942.

From his letters we know he was in Deolali until December when he was moved up to Imphal in North East India on the border with Burma as the very last replacements for the 77th Infantry Brigade, the Chindits. Imphal became the base for the launch of Operation Longcloth under Orde Wingate.

The story of the campaign has been covered in detail elsewhere, but I wish to pick up the story in detail in early April, when the decision to retreat was made and ‘Dispersal Group 4’ was further split under Lieutenant Walker with Captain Aird and Lieutenant’s Hector and Anderson-Williams. The fate of this group is also covered in some detail on this website, but there is an interesting family document compiled by John Hector soon after the end of the War which tells the story of the 10th and 11th April 1943. It is probably best simply to read the original document.

Seen below is the letter in question, it is a remarkable document in many ways, but perhaps most of all it is a testament to the incredible effort that John Hector made to find out what had happened to his dear brother back in 1943. Please click on the images to enlarge.

Paul continues:

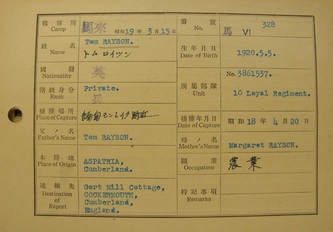

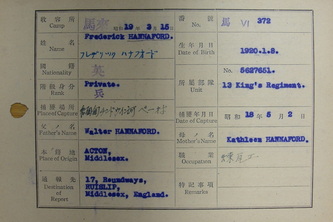

The report made by John I feel is accurate. It tells from an eyewitness view the story with compelling incidental details. Steve's dysentery, the meeting with the other Group, the fork in the trail, the waiting time, the details of Pte. Rayson's injury and the fact that he was a muleteer. After the War John met with all the survivors but one, one refused to meet with him even after travelling up North to see him. The only man that came from the north of the country was Pte. Rayson. We will probably never know the truth of the last hours of Steve’s life. What we do know is that Steve was a true hero.

Both Paul and I discussed the many intriguing aspects of the story brought to life from the information in John Hector's letter. As Paul rightly says, we will probably never really know, but it is incredible how much we all do now understand about those times. I have always felt that the bravery and devotion to duty of the four officers from 'Dispersal Group 4' stood out from amongst their peers in 1943. They knew from the beginning that their chances of returning to India in tact were slim, but they all stuck to the task and by their men.

As Paul told me: "In my mind it makes Steve's sacrifice even more heroic, especially when you consider Wingate's 'leave behind policy'. If ever a man (Steve Hector) deserved a medal."

It is also possible to understand the reluctance of those who did survive Operation Longcloth, to speak about their experiences and ordeals with others. Soldiers such as Tom Rayson, who had not only suffered injury during the operation itself, but had also survived the trauma of being held a prisoner of war.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Paul Hector for his valuable contribution to these website pages and dedicate this section to his father, George, for ensuring that the letters and information regarding Lieutenant Stephen Hector were kept safe and duly passed down through the family.

Seen below are some images further illustrating this section of the story.

The report made by John I feel is accurate. It tells from an eyewitness view the story with compelling incidental details. Steve's dysentery, the meeting with the other Group, the fork in the trail, the waiting time, the details of Pte. Rayson's injury and the fact that he was a muleteer. After the War John met with all the survivors but one, one refused to meet with him even after travelling up North to see him. The only man that came from the north of the country was Pte. Rayson. We will probably never know the truth of the last hours of Steve’s life. What we do know is that Steve was a true hero.

Both Paul and I discussed the many intriguing aspects of the story brought to life from the information in John Hector's letter. As Paul rightly says, we will probably never really know, but it is incredible how much we all do now understand about those times. I have always felt that the bravery and devotion to duty of the four officers from 'Dispersal Group 4' stood out from amongst their peers in 1943. They knew from the beginning that their chances of returning to India in tact were slim, but they all stuck to the task and by their men.

As Paul told me: "In my mind it makes Steve's sacrifice even more heroic, especially when you consider Wingate's 'leave behind policy'. If ever a man (Steve Hector) deserved a medal."

It is also possible to understand the reluctance of those who did survive Operation Longcloth, to speak about their experiences and ordeals with others. Soldiers such as Tom Rayson, who had not only suffered injury during the operation itself, but had also survived the trauma of being held a prisoner of war.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Paul Hector for his valuable contribution to these website pages and dedicate this section to his father, George, for ensuring that the letters and information regarding Lieutenant Stephen Hector were kept safe and duly passed down through the family.

Seen below are some images further illustrating this section of the story.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and the Hector family 2011/13.

The Family of George Albert Gale

Pte. George Gale was a member of D Company within the 13th battalion of the Kings regiment stationed in India in 1942. Being part of D Company automatically placed soldiers with Major Scott’s 8th column in Chindit training that year.

George (seen pictured to the left in his Chindit bush hat) was one of the very earliest casualties on operation Longcloth, being killed in action on Saturday 6th March 1943. Here is a link to his CWGC details:

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2509182/gale,-george-albert/

Not much is written about this period in early March and George has no witness report against his name in the WO 361 files (Missing in Action) held at the National Archives. However, around this time both 7 and 8 column were detailed to make secure the road which ran between two villages, in order for a much needed supply drop to take place. It was during this time that George Gale was sadly killed.

I have been very fortunate to make contact with the Gale family via Bob Holman, who has been investigating his family history for some years. I noticed his post in the Summer 2004 issue of the Burma Star magazine, Dekho. I sent off a letter and hoped for the best, it was wonderful to receive Bob's reply.

George (seen pictured to the left in his Chindit bush hat) was one of the very earliest casualties on operation Longcloth, being killed in action on Saturday 6th March 1943. Here is a link to his CWGC details:

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2509182/gale,-george-albert/

Not much is written about this period in early March and George has no witness report against his name in the WO 361 files (Missing in Action) held at the National Archives. However, around this time both 7 and 8 column were detailed to make secure the road which ran between two villages, in order for a much needed supply drop to take place. It was during this time that George Gale was sadly killed.

I have been very fortunate to make contact with the Gale family via Bob Holman, who has been investigating his family history for some years. I noticed his post in the Summer 2004 issue of the Burma Star magazine, Dekho. I sent off a letter and hoped for the best, it was wonderful to receive Bob's reply.

Here is what the family remember of George Gale and what was a sadly short life:

Pte. 5111657 George Albert Gale

Although George was a member of my family, I never had the privilege of knowing him; he died before I was born. I learned about him from my mother Violet Holman nee Knight, they were cousins. George’s father Albert, was my maternal grandmother’s brother; she was Lily Knight nee Gale.

Mom talked a lot about George, and always wondered what had happened to him as a ‘Chindit’ in Burma. They were obviously close. I know that after George’s first wife Gladys died with TB, their son Howard lived with my grandmother and her family.

I know a little of George’s life; he was born on the 6th February 1915 at 21 Court, 11 Watery Lane, Small Heath, Birmingham, the only son of Albert Henry Gale and Edith Gale nee Starling, his father was employed as an ammunition worker. This district of Birmingham was an inner city working class area.

George attended the nearby Alcock Street School, I know when he was10 years old the family had moved to 11/195 Watery Lane, remaining in the area where the extended Knight/Gale family also lived.

In 1935 George was working as a steel tube drawer in a local factory, on the 6th April that year he married Gladys North, at Birmingham Register Office. Both were 19 years of age, Gladys was a local girl, also working in a nearby factory. On 3rd November 1935 their only child, Howard Joseph Gale was born (see photograph above). Tragically, on the 10th March 1937, when Howard was barely 17 months old, Gladys died of tuberculosis. The family rallied round and Howard lived ostensibly with my grandmother and her family, Mom recalls how Howard became like a brother to her and her siblings.

Sometime between Gladys’s death and early 1939, George enlisted in the 8th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment. This was a territorial battalion, based I believe at Witton Barracks, in Aston. On the 25th August 1939, with war imminent the battalion was mobilised, being moved in mid-September to barracks in Swindon. On 2nd October 1939 as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) the battalion sailed from Dover on the “Ulster Princess’, landing at Le Havre. I believe George was in this draft.

I have copies of letters from George, sent to his cousin Ada Wiggall nee Knight whilst he was in France during the ‘Phoney War’ period. One of these dated 15/03/1940, shows that George was in B Company of the 8th Battalion. He seemed to be enjoying his time in France.

Once the German Army invaded France and Belgium the regiment was heavily engaged trying to stop the enemy advance, when things became critical it helped hold the perimeter, thus allowing the Dunkirk evacuation. I am aware the regiment suffered heavy casualties and was reduced to nearly half its original strength. George was involved in this action and was evacuated from Dunkirk. My mother believed he was wounded at Dunkirk, but I have been unable to substantiate this.

Pte. 5111657 George Albert Gale

Although George was a member of my family, I never had the privilege of knowing him; he died before I was born. I learned about him from my mother Violet Holman nee Knight, they were cousins. George’s father Albert, was my maternal grandmother’s brother; she was Lily Knight nee Gale.

Mom talked a lot about George, and always wondered what had happened to him as a ‘Chindit’ in Burma. They were obviously close. I know that after George’s first wife Gladys died with TB, their son Howard lived with my grandmother and her family.

I know a little of George’s life; he was born on the 6th February 1915 at 21 Court, 11 Watery Lane, Small Heath, Birmingham, the only son of Albert Henry Gale and Edith Gale nee Starling, his father was employed as an ammunition worker. This district of Birmingham was an inner city working class area.

George attended the nearby Alcock Street School, I know when he was10 years old the family had moved to 11/195 Watery Lane, remaining in the area where the extended Knight/Gale family also lived.

In 1935 George was working as a steel tube drawer in a local factory, on the 6th April that year he married Gladys North, at Birmingham Register Office. Both were 19 years of age, Gladys was a local girl, also working in a nearby factory. On 3rd November 1935 their only child, Howard Joseph Gale was born (see photograph above). Tragically, on the 10th March 1937, when Howard was barely 17 months old, Gladys died of tuberculosis. The family rallied round and Howard lived ostensibly with my grandmother and her family, Mom recalls how Howard became like a brother to her and her siblings.

Sometime between Gladys’s death and early 1939, George enlisted in the 8th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment. This was a territorial battalion, based I believe at Witton Barracks, in Aston. On the 25th August 1939, with war imminent the battalion was mobilised, being moved in mid-September to barracks in Swindon. On 2nd October 1939 as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) the battalion sailed from Dover on the “Ulster Princess’, landing at Le Havre. I believe George was in this draft.

I have copies of letters from George, sent to his cousin Ada Wiggall nee Knight whilst he was in France during the ‘Phoney War’ period. One of these dated 15/03/1940, shows that George was in B Company of the 8th Battalion. He seemed to be enjoying his time in France.

Once the German Army invaded France and Belgium the regiment was heavily engaged trying to stop the enemy advance, when things became critical it helped hold the perimeter, thus allowing the Dunkirk evacuation. I am aware the regiment suffered heavy casualties and was reduced to nearly half its original strength. George was involved in this action and was evacuated from Dunkirk. My mother believed he was wounded at Dunkirk, but I have been unable to substantiate this.

Once back in England George met and married Iris Winifred Ives, on the 24th December 1941 at Tavistock Parish Church, Devon. At this time he was still serving in the Warwickshire Regiment. The family moved to Tavistock (where Iris came from) taking Howard with them. Mom always remembered with tears in her eyes the day Howard left, even my grandfather George Knight, who was a WW1 veteran cried. Some fifty years later I managed to trace Howard, and in 2002 a joyful reunion with Mom was held.

After his marriage to Iris, George was either transferred or more likely volunteered to serve in the 13th Battalion, the Kings (Liverpool) Regiment. He subsequently became a ‘Chindit’ and in 1943 took part in operation Longcloth. He was in column 8 commanded by Major Scott.

George was killed in Burma on 6th March 1943, all the family knew was that he was reported killed in action on this date, and no further information was forthcoming. I am deeply grateful to Steve Fogden for his research and providing details of how George died; “together with a group of other men, he was protecting a large supply drop to columns 7 and 8, which took place on a well used track between a village called Pinlebu and a place called Kame.

The road came under attack from a Japanese machine gun unit, six men were killed or severely wounded”. He has no known grave and is remembered on Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, in Taukkyan War Cemetery. George was 28 years old when he died.

I have also included a letter from George’s cousin Ada Wiggall sent on the 26th June 1943, asking about his welfare; tragically George had already been dead for three months. I am regularly in touch with George’s son Howard, whose consent I have to write this story. I feel I know George, although I never met him, a brave man who died serving his country. It is so important that such men are not forgotten.

Robert Holman (written November 2011).

After his marriage to Iris, George was either transferred or more likely volunteered to serve in the 13th Battalion, the Kings (Liverpool) Regiment. He subsequently became a ‘Chindit’ and in 1943 took part in operation Longcloth. He was in column 8 commanded by Major Scott.

George was killed in Burma on 6th March 1943, all the family knew was that he was reported killed in action on this date, and no further information was forthcoming. I am deeply grateful to Steve Fogden for his research and providing details of how George died; “together with a group of other men, he was protecting a large supply drop to columns 7 and 8, which took place on a well used track between a village called Pinlebu and a place called Kame.

The road came under attack from a Japanese machine gun unit, six men were killed or severely wounded”. He has no known grave and is remembered on Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, in Taukkyan War Cemetery. George was 28 years old when he died.

I have also included a letter from George’s cousin Ada Wiggall sent on the 26th June 1943, asking about his welfare; tragically George had already been dead for three months. I am regularly in touch with George’s son Howard, whose consent I have to write this story. I feel I know George, although I never met him, a brave man who died serving his country. It is so important that such men are not forgotten.

Robert Holman (written November 2011).

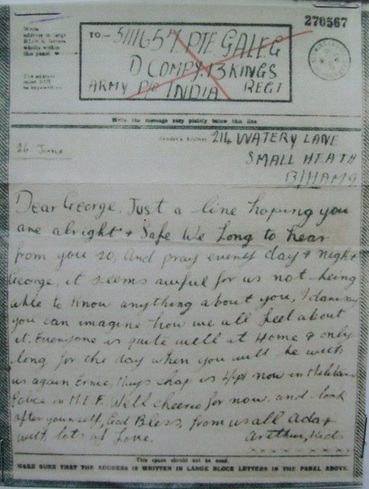

Here are the two letters Bob mentions, transcribed below. The image to the right is the final airgraph letter sent to George by cousin Ada. I do wonder whether the diagonal red cross through his name in the address panel tells it's own story.

Letter 1. Written whilst in France on 15/03/1940 to his cousin Ada Wiggall:

Dear Ada,

Thanks for your letters, I am sorry I did not answer your first one. I see Arthur is just the same as ever from what you told me about the mouse, and the notes from the kids were good, did they write them by themselves?

I have not seen Mag’s chap, although I have seen fellows from his lot, but I can never think of his name when I want to ask about him. Thanks for thinking about me, but I think I am more capable of looking after myself now, than I have ever been and I would not have missed this for anything, although we all grumble at times, so I should not worry.

Well Ada, I think that is about all, I wish I could put as much in a letter as you do and hope you understand. So give my love to Arthur and the children, I may be able to send you a photo, but I cannot promise you, good night and God bless you, Arthur and the children, I keep forgetting you have four now.

George xxxxx.

Letter 2 (Airgraph shown above): From Ada Wiggall to George dated 26/06/1943. Sadly written three months after his death in Burma.

Dear George,

Just a line hoping you are alright and safe. We long to hear from you so, and pray every day and night George, it seems awful for us not being able to know anything about you, I dare say you can imagine how we all feel about it.

Everyone is quite well at home and only long for the day when you will be us again. Ernie, Mag’s chap, is L/Corporal now in the Military Police in the M.E.F.

Well cheerio for now and look after yourself, God Bless from us all, with lots of love.

Ada, Arthur and kids. Xxxxxx

As stated earlier there is little direct information concerning George's death in March 1943, although we do know the column were involved in securing a position in readiness for a large air supply drop. Here are some passages taken from the 8th column war diary for that period:

4th and 5th March: column moved into the area around Pinlebu, there were said to be 600-1000 enemy troops in this locality. The Burma Rifle Officers had spoken to a native of the area, he turned out to be a Japanese spy and was shot. Water parties were sent out to replenish supplies, these units were engaged by enemy patrols but most managed to disengage and return to the main body.

More minor clashes with the Japanese were incurred late on 5th March, the column moved to the agreed rendezvous on the Pinlebu-Kame road. The party halted one mile north of Kame and settled down for the night. Their position was chosen by Major Scott and units were deployed to prevent any Japanese movement toward Pinlebu from this direction.

At first light on the 6th March, the Sabotage Squad led by Lieutenant Sprague and 16 Platoon set out toward Kame to secure the road block. At about 1100 hours Sprague’s men were attacked by the Japanese from all sides, he called dispersal in an attempt to extract his men, it was here that Lieutenant Callaghan was shot and killed.

At 1600 hours the whole column moved away toward the Supply drop rendezvous area.

So as you can see the situation was very confused, with enemy troops engaging the column positions on several occasions over that three day period. It would seem that George was most likely part of either Sprague’s Sabotage Squad or a member of Platoon 16.

Another good source of information from this period can be found in the book ‘Wingate Adventure’ by WG Burchett. From pages 72, 73 and 74 comes this paraphrased account:

As No. 2 Group neared Pinlebu, Gilkes and Brigade HQ moved east to arrange a Supply drop zone, whilst Major Scott’s Column took up defensive positions around Pinlebu.

On the 5th, Scott occupied a village two and a half miles from Pinlebu and sent his patrols out covering all directions.

The Japanese were everywhere, but usually betrayed their positions early by blazing away at the slightest movement or noise.

The minor battle lasted all day and into the night, dispersal was then called and the column moved away. Early on the 6th March, Scott set up roadblocks leading east and north out of Pinlebu, the supply drop continued unhindered.

Scott had no sooner closed the roadblocks and was preparing to move off, when a Japanese patrol opened fire on one of the furthest placed groups. A brisk thirty-minute battle ensued, leaving six men killed or badly wounded. Column 8 withdrew to safer ground.

For the loss of six men the column had held up the enemy for over 24 hours, covering Calvert and Fergusson’s dash to the railway and allowing HQ to secure a vital supply drop.

Sadly of course, one of these casualties would have been George Gale. From looking through the missing in action reports and witness statements for 8th March 1943, I believe the other men to be:

Lieutenant William Thomas Callaghan, a member of Lieutenant T.A.G. Sprague’s Sabotage Squad and also mentioned in the column War Diary as having been killed on that day. Here are his CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2506717/william-thomas-callaghan/

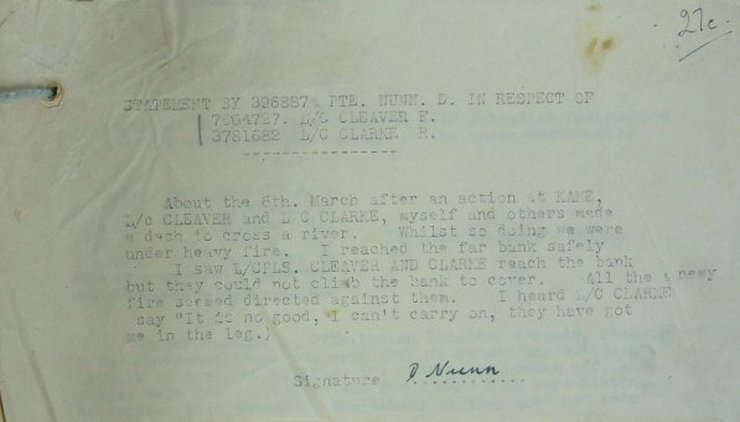

Lance Corporal 3781682 Robert Clarke. Lost whilst attempting to cross a small chaung as shown below in the witness statement of Pte. D. Nunn. Robert Clarke was from Manchester.

Letter 1. Written whilst in France on 15/03/1940 to his cousin Ada Wiggall:

Dear Ada,

Thanks for your letters, I am sorry I did not answer your first one. I see Arthur is just the same as ever from what you told me about the mouse, and the notes from the kids were good, did they write them by themselves?

I have not seen Mag’s chap, although I have seen fellows from his lot, but I can never think of his name when I want to ask about him. Thanks for thinking about me, but I think I am more capable of looking after myself now, than I have ever been and I would not have missed this for anything, although we all grumble at times, so I should not worry.

Well Ada, I think that is about all, I wish I could put as much in a letter as you do and hope you understand. So give my love to Arthur and the children, I may be able to send you a photo, but I cannot promise you, good night and God bless you, Arthur and the children, I keep forgetting you have four now.

George xxxxx.

Letter 2 (Airgraph shown above): From Ada Wiggall to George dated 26/06/1943. Sadly written three months after his death in Burma.

Dear George,

Just a line hoping you are alright and safe. We long to hear from you so, and pray every day and night George, it seems awful for us not being able to know anything about you, I dare say you can imagine how we all feel about it.

Everyone is quite well at home and only long for the day when you will be us again. Ernie, Mag’s chap, is L/Corporal now in the Military Police in the M.E.F.

Well cheerio for now and look after yourself, God Bless from us all, with lots of love.

Ada, Arthur and kids. Xxxxxx

As stated earlier there is little direct information concerning George's death in March 1943, although we do know the column were involved in securing a position in readiness for a large air supply drop. Here are some passages taken from the 8th column war diary for that period:

4th and 5th March: column moved into the area around Pinlebu, there were said to be 600-1000 enemy troops in this locality. The Burma Rifle Officers had spoken to a native of the area, he turned out to be a Japanese spy and was shot. Water parties were sent out to replenish supplies, these units were engaged by enemy patrols but most managed to disengage and return to the main body.

More minor clashes with the Japanese were incurred late on 5th March, the column moved to the agreed rendezvous on the Pinlebu-Kame road. The party halted one mile north of Kame and settled down for the night. Their position was chosen by Major Scott and units were deployed to prevent any Japanese movement toward Pinlebu from this direction.

At first light on the 6th March, the Sabotage Squad led by Lieutenant Sprague and 16 Platoon set out toward Kame to secure the road block. At about 1100 hours Sprague’s men were attacked by the Japanese from all sides, he called dispersal in an attempt to extract his men, it was here that Lieutenant Callaghan was shot and killed.

At 1600 hours the whole column moved away toward the Supply drop rendezvous area.

So as you can see the situation was very confused, with enemy troops engaging the column positions on several occasions over that three day period. It would seem that George was most likely part of either Sprague’s Sabotage Squad or a member of Platoon 16.

Another good source of information from this period can be found in the book ‘Wingate Adventure’ by WG Burchett. From pages 72, 73 and 74 comes this paraphrased account:

As No. 2 Group neared Pinlebu, Gilkes and Brigade HQ moved east to arrange a Supply drop zone, whilst Major Scott’s Column took up defensive positions around Pinlebu.

On the 5th, Scott occupied a village two and a half miles from Pinlebu and sent his patrols out covering all directions.

The Japanese were everywhere, but usually betrayed their positions early by blazing away at the slightest movement or noise.

The minor battle lasted all day and into the night, dispersal was then called and the column moved away. Early on the 6th March, Scott set up roadblocks leading east and north out of Pinlebu, the supply drop continued unhindered.

Scott had no sooner closed the roadblocks and was preparing to move off, when a Japanese patrol opened fire on one of the furthest placed groups. A brisk thirty-minute battle ensued, leaving six men killed or badly wounded. Column 8 withdrew to safer ground.

For the loss of six men the column had held up the enemy for over 24 hours, covering Calvert and Fergusson’s dash to the railway and allowing HQ to secure a vital supply drop.

Sadly of course, one of these casualties would have been George Gale. From looking through the missing in action reports and witness statements for 8th March 1943, I believe the other men to be:

Lieutenant William Thomas Callaghan, a member of Lieutenant T.A.G. Sprague’s Sabotage Squad and also mentioned in the column War Diary as having been killed on that day. Here are his CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2506717/william-thomas-callaghan/

Lance Corporal 3781682 Robert Clarke. Lost whilst attempting to cross a small chaung as shown below in the witness statement of Pte. D. Nunn. Robert Clarke was from Manchester.

Pte. 7664627 Frank Cleaver. This soldier was killed later on from Japanese mortar fire whilst in bivouac, he originally came from London. This information came from a witness statement given after hostilities had ended in Rangoon by Pte. Thomas Worthington a surviving POW.

Pte. 5184297 Ronald Edward Coleman. Sadly, there is no precise detail about this man.

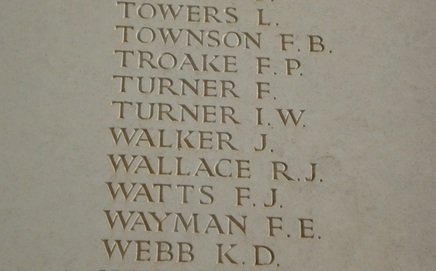

Pte. 3656817 James Walker. Apart from his recorded date of death, there is no more information about this soldier. Please see his inscription on the Rangoon Memorial panel pictured at the end of this story.

Another man who was fortunate enough to escape that day and indeed survive the whole expedition was Pte. 3968824 D. Nunn. It was from his witness statements given back in India in August 1943 that most of the known information is derived.

Pte. 5184297 Ronald Edward Coleman. Sadly, there is no precise detail about this man.

Pte. 3656817 James Walker. Apart from his recorded date of death, there is no more information about this soldier. Please see his inscription on the Rangoon Memorial panel pictured at the end of this story.

Another man who was fortunate enough to escape that day and indeed survive the whole expedition was Pte. 3968824 D. Nunn. It was from his witness statements given back in India in August 1943 that most of the known information is derived.

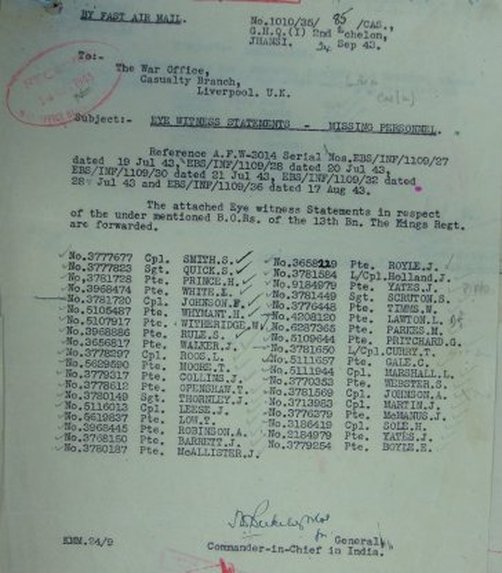

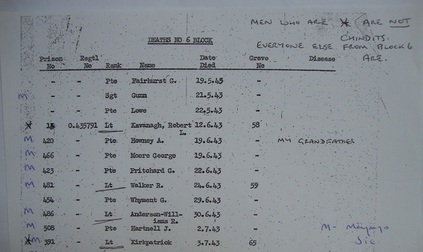

The only document I have found with George’s name on, and even here his initial is incorrect, is the one seen above. It is a simple list of names referring to men lost from operation Longcloth in 1943. There are many frustrations within the WO361 Missing in Action files held at the National Archives, with lead papers often suggesting more information to follow, but in too many instances these papers never appear. All the men listed on the above page are likely to have had some kind of witness statement against their name. Unfortunately, these pages were not present in the files.

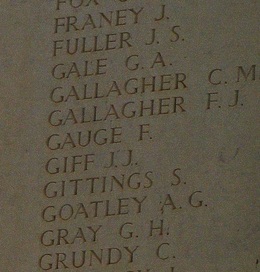

The last resting place of all these men was never recorded or at least when the war was over, could not be located. They are all remembered on the Rangoon Memorial, mostly on Faces 5 and 6. Seen below are the inscriptions for George Gale and James Walker.

(Images by kind courtesy of TonyB).

The last resting place of all these men was never recorded or at least when the war was over, could not be located. They are all remembered on the Rangoon Memorial, mostly on Faces 5 and 6. Seen below are the inscriptions for George Gale and James Walker.

(Images by kind courtesy of TonyB).

Update 09/07/2013.

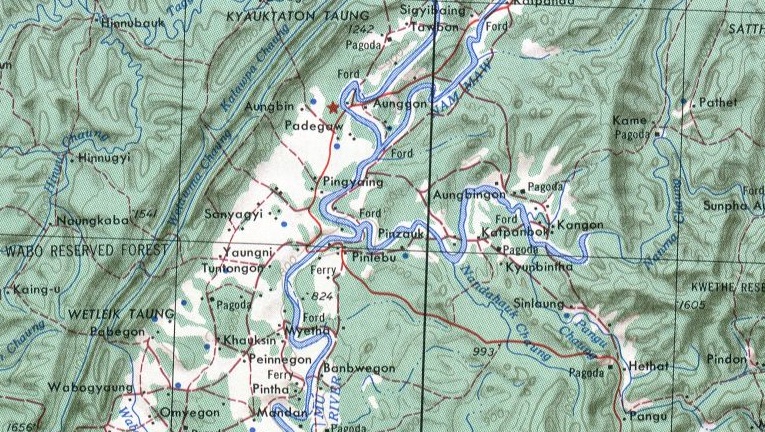

A reference map for the general area around the villages of Pinlebu and Kame.

A reference map for the general area around the villages of Pinlebu and Kame.

Update 26/08/2013.

I thought it would be of some interest to this story to read Wingate's own account and view of the action around Pinlebu in early March 1943. Here is a condensed, paraphrased summary of his appraisal:

I sent Column 8 off to Pinlebu to make the enemy believe that this was our main objective. In this we were successful. Intelligence had told us that the Japanese Garrison in the town was at double Company strength, with two more stationed at Wuntho. Allied bombing called in by our RAF Officers on the 4th March had been effective and the Japanese dispersed widely in organised defences covering several square miles.

Column 8 succeeded in attracting a good deal of attention and at one point even carried out a dispersal manoeuvre. The re-forming afterwards was also successful but for the loss of some of our Other Ranks. I ordered the continued ambush of tracks leading both North and East of Pinlebu to cover our main objective, a large Supply Drop planned for the 6th.

It was clear to me from these engagements with the enemy, that Column 8 had much to learn in the way of ordinary Infantry tactics and positioning, in this respect they were inferior to the Japanese. Nevertheless, they were superior to the enemy in handling their nerve, movement through the jungle and the power of surprise.

Lieut. Colonel Cooke took charge of the supply dropping on the 6th. While it was proceeding, the sounds of Mortar and Machine Gun fire could be heard from the direction of Pinlebu as Column 8 went about their business. Their action had confused the Japanese and the enemies fear of engaging the column in the surrounding jungle had left the supply drop unmolested.

Update 05/11/2013.

A new story has been added to these website pages about another soldier from both Column 8 and originally the 8th Warwick's. Pte. Frank Holland was not only in George Gale's original unit, but travelled over to India presumably on the same troopship. Both men were Chindit comrades and good pals in 1942/43, and Frank remembers the day that his mate, George Gale was killed.

To read more about his own Chindit experience, follow the link below: Pte. Frank Holland

I sent this new information to the family of Pte. George Gale. This is what they had to say:

Thanks Steve, I am most grateful to you, read the story and was amazed, as you say its obviously George. I will enquire with the family to see if anyone knew of the "Teddy" nickname. One thing that intrigues me is that Frank Holland went to see George's Mum after the war, she lived in Birmingham, in Watery Lane, Bordesley Green. Also, I often wondered how George Gale met his second wife Iris, who was from Tavistock in Devon. But Frank Holland's journal mentioned that the Warwick's were sent to Tavistock, which I think answers the question. Once again thanks for your help. Bob Holman

Update 22/03/2014.

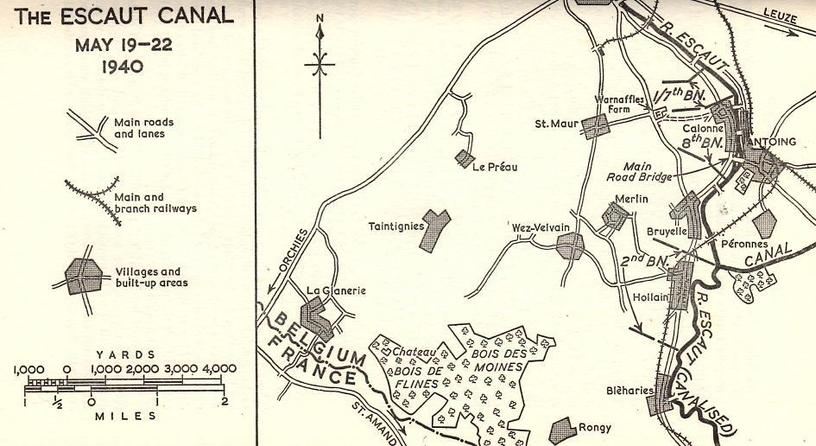

As mentioned earlier in this story, George Gale was a member of the 8th Battalion, the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and served with the BEF in France in 1940. The 8th Battalion found themselves in the region south of the Escaut Canal, near the town of Calonne. Here is a commentary for the battalion during the 20th, 21st and 22nd of May 1940, concentrating specifically on George's B Company:

Things went harder with the 8th Battalion on May 20th. All three forward companies were mortared, shelled, sniped and machine-gunned, with special attention to C Company on the right, where 2/Lieutenant D. F. Hanmer and RSM Knight were wounded early in the day.

Battalion HQ at Warnaffles Farm was like wise shelled. So was B Echelon, back at Le Preau. C Company brought down Artillery fire on the buildings opposite its front and managed to silence the enemy there, as well as to shoot a number of Germans driven out of the buildings by shelling.

B Company on the left, saw Germans at some distance bringing forward what looked like pontoon equipment, though no effort was made to bridge the river with it during daylight. At nightfall, however, enemy parties launched an attack against B Company with two assault boats, making use also of two small, partly demolished bridges. Both boats were destroyed, "one of them by a lucky grenade thrown when it was under cover of the bank on our side", and the attack was beaten off. But the battalion was losing a good many men from the unremitting enemy fire.

Captain N. S. Robinson, the Medical Officer, was killed by a shell while loading up an ambulance outside the battalion aid post. And by a horrible mischance Captain Glover of B Company was shot dead by one of his own Corporals, who had reportedly gone insane. It was doubly hard to lose a fine officer in such a manner. The German fire abated little by little. Shortly after midnight, on the B Company front the enemy was observed trying to swing a pontoon into a bridge gap. This bridge was blown right against the enemy side, and was close to some solid buildings with a wide gate just opposite, giving an easy approach to within a few yards of the gap. Fire was opened and the pontoon was left suspended in the air (from a crane) where, by keeping it under fire, it remained all night.

The day ended, then, with the battalion intact, but with two disquieting features. The first was that, at midnight, a C Company patrol covering the open flank was fired on from a building on the home bank: the Germans had secured a lodgement. The second was that there was no sign of the relieving battalion; and that there was no news either of its whereabouts or of future plans for the 8th Battalion.

May 21st was a grim day for both the 8th Battalion and the 2nd. During the night our Artillery had fired repeatedly at suspected enemy concentrations opposite the 2nd Battalion. Before dawn, D Company was reporting heavy enemy pressure, from Germans now in some numbers on the home bank of the river.

Though not under such direct pressure, B Company had likewise had some critical moments. During the night of May 20/21 enemy shelling was relentlessly heavy and accurate. The Commander and Sergeant of No. 10 Platoon were badly wounded; indeed so many men became casualties that the platoon became demoralised. It was courageously rallied by 2/ Lieutenant B. L. Gunnell, then acting as Company 2nd-in-Command, who went forward and reorganised the platoon, successfully restoring its confidence and morale. For this action, and for his subsequent resistance at Wormhoudt, where he was actually commanding No.10 Platoon, 2/ Lieutenant Gunnell won the MC.

By the morning of the 22nd and still at Calonne, enemy infantry, advancing on the heels of their own bombardment, tried to get across the river. But some B Company posts were still holding on among the shattered buildings, and they held back the enemy by small-arms fire. Some Germans did manage to cross on the Battalion's left, only to be wiped out by the Royal Scots.

As these attempts had come to nothing, the Germans resorted once more to pounding the battalion area with high-explosive. Many casualties were incurred by the battalion; and in the confusion some Germans seem to have crossed the river at about the junction between B and A Companies. All lines were smashed, and no contact could be made with Battalion HQ.

B Company had been effectively destroyed and had lost both Captain Glover and Captain H. Sparrow. The remainder of the company was led out by Sergeant Bate, but even here encountered German motor-cyclists as they moved through the main street at Calonne.

Finally, and after many hours of frustration in holding on, the Warwicks were able to hand over their position to the Royal Scots.

To read more about the men from the 8th Warwick's who served on Operation Longcloth in 1943, please click on the following link: 8th Warwick's at Dunkirk

I thought it would be of some interest to this story to read Wingate's own account and view of the action around Pinlebu in early March 1943. Here is a condensed, paraphrased summary of his appraisal:

I sent Column 8 off to Pinlebu to make the enemy believe that this was our main objective. In this we were successful. Intelligence had told us that the Japanese Garrison in the town was at double Company strength, with two more stationed at Wuntho. Allied bombing called in by our RAF Officers on the 4th March had been effective and the Japanese dispersed widely in organised defences covering several square miles.

Column 8 succeeded in attracting a good deal of attention and at one point even carried out a dispersal manoeuvre. The re-forming afterwards was also successful but for the loss of some of our Other Ranks. I ordered the continued ambush of tracks leading both North and East of Pinlebu to cover our main objective, a large Supply Drop planned for the 6th.

It was clear to me from these engagements with the enemy, that Column 8 had much to learn in the way of ordinary Infantry tactics and positioning, in this respect they were inferior to the Japanese. Nevertheless, they were superior to the enemy in handling their nerve, movement through the jungle and the power of surprise.

Lieut. Colonel Cooke took charge of the supply dropping on the 6th. While it was proceeding, the sounds of Mortar and Machine Gun fire could be heard from the direction of Pinlebu as Column 8 went about their business. Their action had confused the Japanese and the enemies fear of engaging the column in the surrounding jungle had left the supply drop unmolested.

Update 05/11/2013.

A new story has been added to these website pages about another soldier from both Column 8 and originally the 8th Warwick's. Pte. Frank Holland was not only in George Gale's original unit, but travelled over to India presumably on the same troopship. Both men were Chindit comrades and good pals in 1942/43, and Frank remembers the day that his mate, George Gale was killed.

To read more about his own Chindit experience, follow the link below: Pte. Frank Holland

I sent this new information to the family of Pte. George Gale. This is what they had to say:

Thanks Steve, I am most grateful to you, read the story and was amazed, as you say its obviously George. I will enquire with the family to see if anyone knew of the "Teddy" nickname. One thing that intrigues me is that Frank Holland went to see George's Mum after the war, she lived in Birmingham, in Watery Lane, Bordesley Green. Also, I often wondered how George Gale met his second wife Iris, who was from Tavistock in Devon. But Frank Holland's journal mentioned that the Warwick's were sent to Tavistock, which I think answers the question. Once again thanks for your help. Bob Holman

Update 22/03/2014.

As mentioned earlier in this story, George Gale was a member of the 8th Battalion, the Royal Warwickshire Regiment and served with the BEF in France in 1940. The 8th Battalion found themselves in the region south of the Escaut Canal, near the town of Calonne. Here is a commentary for the battalion during the 20th, 21st and 22nd of May 1940, concentrating specifically on George's B Company:

Things went harder with the 8th Battalion on May 20th. All three forward companies were mortared, shelled, sniped and machine-gunned, with special attention to C Company on the right, where 2/Lieutenant D. F. Hanmer and RSM Knight were wounded early in the day.

Battalion HQ at Warnaffles Farm was like wise shelled. So was B Echelon, back at Le Preau. C Company brought down Artillery fire on the buildings opposite its front and managed to silence the enemy there, as well as to shoot a number of Germans driven out of the buildings by shelling.

B Company on the left, saw Germans at some distance bringing forward what looked like pontoon equipment, though no effort was made to bridge the river with it during daylight. At nightfall, however, enemy parties launched an attack against B Company with two assault boats, making use also of two small, partly demolished bridges. Both boats were destroyed, "one of them by a lucky grenade thrown when it was under cover of the bank on our side", and the attack was beaten off. But the battalion was losing a good many men from the unremitting enemy fire.

Captain N. S. Robinson, the Medical Officer, was killed by a shell while loading up an ambulance outside the battalion aid post. And by a horrible mischance Captain Glover of B Company was shot dead by one of his own Corporals, who had reportedly gone insane. It was doubly hard to lose a fine officer in such a manner. The German fire abated little by little. Shortly after midnight, on the B Company front the enemy was observed trying to swing a pontoon into a bridge gap. This bridge was blown right against the enemy side, and was close to some solid buildings with a wide gate just opposite, giving an easy approach to within a few yards of the gap. Fire was opened and the pontoon was left suspended in the air (from a crane) where, by keeping it under fire, it remained all night.

The day ended, then, with the battalion intact, but with two disquieting features. The first was that, at midnight, a C Company patrol covering the open flank was fired on from a building on the home bank: the Germans had secured a lodgement. The second was that there was no sign of the relieving battalion; and that there was no news either of its whereabouts or of future plans for the 8th Battalion.

May 21st was a grim day for both the 8th Battalion and the 2nd. During the night our Artillery had fired repeatedly at suspected enemy concentrations opposite the 2nd Battalion. Before dawn, D Company was reporting heavy enemy pressure, from Germans now in some numbers on the home bank of the river.

Though not under such direct pressure, B Company had likewise had some critical moments. During the night of May 20/21 enemy shelling was relentlessly heavy and accurate. The Commander and Sergeant of No. 10 Platoon were badly wounded; indeed so many men became casualties that the platoon became demoralised. It was courageously rallied by 2/ Lieutenant B. L. Gunnell, then acting as Company 2nd-in-Command, who went forward and reorganised the platoon, successfully restoring its confidence and morale. For this action, and for his subsequent resistance at Wormhoudt, where he was actually commanding No.10 Platoon, 2/ Lieutenant Gunnell won the MC.

By the morning of the 22nd and still at Calonne, enemy infantry, advancing on the heels of their own bombardment, tried to get across the river. But some B Company posts were still holding on among the shattered buildings, and they held back the enemy by small-arms fire. Some Germans did manage to cross on the Battalion's left, only to be wiped out by the Royal Scots.

As these attempts had come to nothing, the Germans resorted once more to pounding the battalion area with high-explosive. Many casualties were incurred by the battalion; and in the confusion some Germans seem to have crossed the river at about the junction between B and A Companies. All lines were smashed, and no contact could be made with Battalion HQ.

B Company had been effectively destroyed and had lost both Captain Glover and Captain H. Sparrow. The remainder of the company was led out by Sergeant Bate, but even here encountered German motor-cyclists as they moved through the main street at Calonne.

Finally, and after many hours of frustration in holding on, the Warwicks were able to hand over their position to the Royal Scots.

To read more about the men from the 8th Warwick's who served on Operation Longcloth in 1943, please click on the following link: 8th Warwick's at Dunkirk

Copyright © Steve Fogden, Bob Holman and Howard Gale January 2012/14.

The Grandchildren of Francis Cyril Fairhurst

Francis Fairhurst in RCOS uniform

Pte. Francis Cyril Fairhurst has always been an intriguing figure in the research into Longcloth POW's and their journey down to Rangoon Jail in the summer of 1943. On the official list of deaths for the jail held at the Imperial War Museum in London, he is stated as having died at Rangoon on 19th May 1943, but he is then remembered on the Rangoon Memorial in Taukkyan War Cemetery. This memorial is for the men of the Burma campaign who died and have no known grave, where as the men who died in Rangoon Jail are buried almost to a man in Rangoon War Cemetery, which was but a few short miles from the jail itself.

I made contact with one of Pte. Fairhurst's grandsons in June 2012. Steve Fairhurst, like so many of the Longcloth families I have met had very little knowledge of what had happened to his grandfather in 1943 and I had only a missing in action date and his name on the Rangoon Jail POW lists to work with.

Fortunately help arrived in the form of Captain Tommy Roberts diary listings for Rangoon Jail and two missing in action reports from the WO361 file held at the National Archives. The latter document is a large grouping of first hand witness reports in regard to lost and missing from operation Longcloth. By piecing together all this information the outline of a story began to unfold.

Before this story continues I would like to draw attention to the photograph of Francis, seen here to the left and with him wearing the uniform of the Royal Corps of Signals. When Steve sent me this photograph I was surprised to see his grandfather in this particular uniform, complete with riding jodhpurs, crop, 1903 standard pattern bandolier and spurs. His service number 3523186 suggested he began his Army life as part of the Manchester regiment and there was nothing within the information found later on that pointed to a Signals involvement. From additional information gathered it is possible that this photograph might have been taken at the Catterick Garrison in Yorkshire, where all RCOS squads undertook basic training including learning to ride horses.

I made contact with one of Pte. Fairhurst's grandsons in June 2012. Steve Fairhurst, like so many of the Longcloth families I have met had very little knowledge of what had happened to his grandfather in 1943 and I had only a missing in action date and his name on the Rangoon Jail POW lists to work with.

Fortunately help arrived in the form of Captain Tommy Roberts diary listings for Rangoon Jail and two missing in action reports from the WO361 file held at the National Archives. The latter document is a large grouping of first hand witness reports in regard to lost and missing from operation Longcloth. By piecing together all this information the outline of a story began to unfold.

Before this story continues I would like to draw attention to the photograph of Francis, seen here to the left and with him wearing the uniform of the Royal Corps of Signals. When Steve sent me this photograph I was surprised to see his grandfather in this particular uniform, complete with riding jodhpurs, crop, 1903 standard pattern bandolier and spurs. His service number 3523186 suggested he began his Army life as part of the Manchester regiment and there was nothing within the information found later on that pointed to a Signals involvement. From additional information gathered it is possible that this photograph might have been taken at the Catterick Garrison in Yorkshire, where all RCOS squads undertook basic training including learning to ride horses.

Here is what Steve had to say about his grandfather and what his family knew about him:

Since sending you the inital e-mail I have looked on your web site and seen my Grandads name and even address appear on a few documents and I now have a lot more knowledge of what happened to him so thanks

already for that.

I have finally managed to get some photos of Grandad. The one of him wearing a suit (pictured right) I had seen before and have managed to get myself a copy off my Uncle Cyril's widow. The one in uniform I have never seen before, I managed to get a copy from my cousin whose mum was Francis's daughter Joan. The other two images are of the Wigan War Memorial in Wigan town centre, one of the memorial itself and one of the name plate on the memorial that shows Grandad's name.

Unfortunately I can't get any pre-war details about Grandad other than what I told you before. He lived in Frog Lane, Wigan and was married to Elizabeth. They had three children Cyril, Joan and Alan, all of whom were very young when he died. He only ever saw my own father (Alan) once, when he was first born in December 1940.

When Grandad did not return from Burma my Grandma eventually re-married and had three more children. I can remember as a child being taken to the war memorial in Wigan which bears his name, and then a few bits of conversation here and there about the Japanese and jungles. My own dad died when I was 11 so I never really had chance to speak to him about it and as happens with aunts and uncles the conversation never arises. My Grandma and her children with Francis are now all deceased, so the chances of getting any new information are slim.