History and Overview

In December 1941 Japan declared war on Britain and the United States of America. Japan had already been at war with China since 1931 and had forces positioned in the Far East ready to attack. Lightning strikes were made against such targets as Pearl Harbour, Hong Kong and Malaya. Soon after the British suffered a humiliating defeat in Burma and had to retreat westwards into India.

In January 1942, when the Japanese invaded Burma, the British War Office offered the services of Lieutenant-Colonel Orde Wingate DSO, to General Archibald Wavell, the then Commander-in-Chief of Allied forces in India. It was thought that there would be a role for Wingate in Burma with his proven guerrilla expertise, having previously carried out such operations operations in Palestine and Abyssinia with great success.

When Wingate arrived in March 1942 he was tasked with organising these guerrilla operations. He then began to investigate the job at hand and this was when he met Major Michael Calvert, who later became one of Wingate's most trusted and successful Chindit commanders. Together they carried out a reconnaissance of the terrain of north Burma.

In January 1942, when the Japanese invaded Burma, the British War Office offered the services of Lieutenant-Colonel Orde Wingate DSO, to General Archibald Wavell, the then Commander-in-Chief of Allied forces in India. It was thought that there would be a role for Wingate in Burma with his proven guerrilla expertise, having previously carried out such operations operations in Palestine and Abyssinia with great success.

When Wingate arrived in March 1942 he was tasked with organising these guerrilla operations. He then began to investigate the job at hand and this was when he met Major Michael Calvert, who later became one of Wingate's most trusted and successful Chindit commanders. Together they carried out a reconnaissance of the terrain of north Burma.

Long Range Penetration Theory

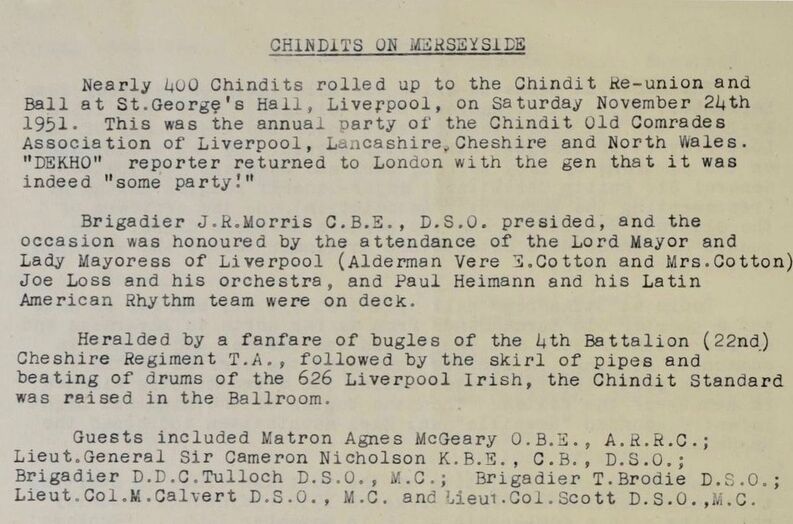

Wingate (pictured left) then put forward his theory that formations of troops supplied from the air could operate for long periods in the jungle. The troops would be organised into columns, each large enough to inflict a heavy blow on the enemy but small enough to evade action if outnumbered. The columns would march into enemy territory to disrupt the Japanese Army’s communications and supply chain and to generally create havoc behind its lines.

Wingate called this Long Range Penetration.

77th Indian Infantry Brigade (Chindits)

The Long Range Penetration theory was approved and Wingate’s experimental force was formed and became 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

The Brigade was made up of:

13th Battalion The King’s (Liverpool) Regiment

3/2nd Gurkha Rifles

142 Commando Company

2nd Burma Rifles

Eight RAF Air liaison sections

Brigade Signal Section from The Royal Corp of Signals

A mule transport company.

The brigade now had to prepare themselves for two enemies, the jungle and the Japanese. Wingate did this by training them in the jungles of the Central Provinces of India, at places like Patharia and Saugor near Jhansi. The men prepared for column and bivouac life, learning to live off the land, train for jungle warfare, river crossings and the care of their beloved mules.

The mules were vital to the Chindit operation as they carried the heavy weapons, ammunition, radios and medical supplies. In Burma supply drops to the Chindits would also include fodder for the mules.

It was during this training period that Wingate chose the name Chindits for the force. It was a mispronunciation of the Burmese word Chinthe (a mythical creature that stands guard outside Burmese pagodas). It is said that Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles was the originator of the name, suggesting that the half griffin, half lion creature symbolised the nature of the Chindits task in Burma that year.

Wingate (pictured left) then put forward his theory that formations of troops supplied from the air could operate for long periods in the jungle. The troops would be organised into columns, each large enough to inflict a heavy blow on the enemy but small enough to evade action if outnumbered. The columns would march into enemy territory to disrupt the Japanese Army’s communications and supply chain and to generally create havoc behind its lines.

Wingate called this Long Range Penetration.

77th Indian Infantry Brigade (Chindits)

The Long Range Penetration theory was approved and Wingate’s experimental force was formed and became 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

The Brigade was made up of:

13th Battalion The King’s (Liverpool) Regiment

3/2nd Gurkha Rifles

142 Commando Company

2nd Burma Rifles

Eight RAF Air liaison sections

Brigade Signal Section from The Royal Corp of Signals

A mule transport company.

The brigade now had to prepare themselves for two enemies, the jungle and the Japanese. Wingate did this by training them in the jungles of the Central Provinces of India, at places like Patharia and Saugor near Jhansi. The men prepared for column and bivouac life, learning to live off the land, train for jungle warfare, river crossings and the care of their beloved mules.

The mules were vital to the Chindit operation as they carried the heavy weapons, ammunition, radios and medical supplies. In Burma supply drops to the Chindits would also include fodder for the mules.

It was during this training period that Wingate chose the name Chindits for the force. It was a mispronunciation of the Burmese word Chinthe (a mythical creature that stands guard outside Burmese pagodas). It is said that Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles was the originator of the name, suggesting that the half griffin, half lion creature symbolised the nature of the Chindits task in Burma that year.

Operation Longcloth

The original plan was that the Long Range Penetration group would be part of a three phased offensive into northern Burma in 1943 (codenamed Ravenous), but this offensive was cancelled. Wingate then proposed that the Long Range Penetration operation should proceed alone, to test his theories and gain vital experience in the jungles of Burma.

General Wavell (seen left with Wingate in India in early 1943) agreed to this and the Chindits were ordered into Burma. The campaign was given the code name Operation Longcloth.

Wavell had hoped that the Wingate force would be the catalyst for a link up between Stilwell's group in the north, IV Corps in the west and Chiang Kai-Shek's Chinese Army in the east. As time moved on and the Chinese leader procrastinated it seemed inevitable that the plan was doomed to failure and should be cancelled.

On the 6th February Wavell arrived at Imphal to speak with Wingate. A long discussion took place that afternoon between the two men in the company of a third interested party, General Somervell of the United States Army.

Wavell explained:

"I had to balance the inevitable losses—the larger since there would be no other operations to divide the enemy's forces—to be sustained without strategical profit, against the experience to be gained of Wingate's new method and organization. I had little doubt in my own mind of the proper course, but I had to satisfy myself that the enterprise had a good chance of success and would not be a senseless sacrifice: and I went into Wingate's proposals in some detail before giving the sanction to proceed for which he and his brigade were so anxious."

Wavell then turned to General Somervell and asked for his view on the decision, the General answered:

"Well, I guess I'd let them roll."

And so the die was cast.

Column Organisation

Wingate organised his force into two groups.

1. Northern Group, consisting of columns 3,4,5,7,8 and Brigade HQ, totalling 2,000 men and 850 mules.

2. Southern Group, consisting of columns 1, 2 and group HQ, totalling 1,000 men and 250 mules.

(the fit men of no. 6 column were broken up and dispersed into the other column units to replace the sick and wounded from the arduous training).

Attached to each column was a RAF Air Liaison section.

A rear HQ remained behind to organise the air supplies for the columns, this was led by Captain Horace Lord.

Each column was typically composed of:

about 400 men built around an infantry company

plus:

a reconnaissance platoon of the Burma Rifles

a Commando platoon

two mortar and two Vickers machine guns teams

a mule transport platoon (about 120 mules)

RAF liaison officer and radio operators to direct air supplies

a doctor

a radio detachment to provide communications between columns.

Each column would march independently and be supplied by air. Where necessary columns would concentrate to achieve specific tasks.

Wingate’s aim for this type of column organisation was to achieve mobility and security. Without having to rely on road-based transport and land based communications lines, a column could go anywhere it wished. These mobile units would then disappear back into the jungle screen making it almost impossible for the Japanese to find them and thereby providing the security it required to operate successfully.

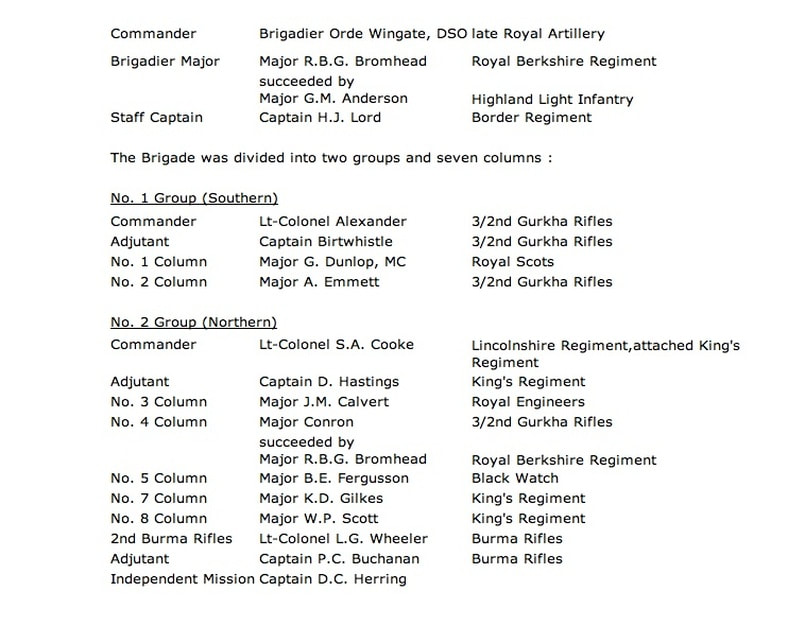

Below is the Operational Order of Battle for Longcloth, showing the breakdown of Units and Columns and their respective Commanders.

The original plan was that the Long Range Penetration group would be part of a three phased offensive into northern Burma in 1943 (codenamed Ravenous), but this offensive was cancelled. Wingate then proposed that the Long Range Penetration operation should proceed alone, to test his theories and gain vital experience in the jungles of Burma.

General Wavell (seen left with Wingate in India in early 1943) agreed to this and the Chindits were ordered into Burma. The campaign was given the code name Operation Longcloth.

Wavell had hoped that the Wingate force would be the catalyst for a link up between Stilwell's group in the north, IV Corps in the west and Chiang Kai-Shek's Chinese Army in the east. As time moved on and the Chinese leader procrastinated it seemed inevitable that the plan was doomed to failure and should be cancelled.

On the 6th February Wavell arrived at Imphal to speak with Wingate. A long discussion took place that afternoon between the two men in the company of a third interested party, General Somervell of the United States Army.

Wavell explained:

"I had to balance the inevitable losses—the larger since there would be no other operations to divide the enemy's forces—to be sustained without strategical profit, against the experience to be gained of Wingate's new method and organization. I had little doubt in my own mind of the proper course, but I had to satisfy myself that the enterprise had a good chance of success and would not be a senseless sacrifice: and I went into Wingate's proposals in some detail before giving the sanction to proceed for which he and his brigade were so anxious."

Wavell then turned to General Somervell and asked for his view on the decision, the General answered:

"Well, I guess I'd let them roll."

And so the die was cast.

Column Organisation

Wingate organised his force into two groups.

1. Northern Group, consisting of columns 3,4,5,7,8 and Brigade HQ, totalling 2,000 men and 850 mules.

2. Southern Group, consisting of columns 1, 2 and group HQ, totalling 1,000 men and 250 mules.

(the fit men of no. 6 column were broken up and dispersed into the other column units to replace the sick and wounded from the arduous training).

Attached to each column was a RAF Air Liaison section.

A rear HQ remained behind to organise the air supplies for the columns, this was led by Captain Horace Lord.

Each column was typically composed of:

about 400 men built around an infantry company

plus:

a reconnaissance platoon of the Burma Rifles

a Commando platoon

two mortar and two Vickers machine guns teams

a mule transport platoon (about 120 mules)

RAF liaison officer and radio operators to direct air supplies

a doctor

a radio detachment to provide communications between columns.

Each column would march independently and be supplied by air. Where necessary columns would concentrate to achieve specific tasks.

Wingate’s aim for this type of column organisation was to achieve mobility and security. Without having to rely on road-based transport and land based communications lines, a column could go anywhere it wished. These mobile units would then disappear back into the jungle screen making it almost impossible for the Japanese to find them and thereby providing the security it required to operate successfully.

Below is the Operational Order of Battle for Longcloth, showing the breakdown of Units and Columns and their respective Commanders.

Below is a copy of a listing I came across in one of the many file documents concerning the operation in 1943. It shows the final numbers in regards to personnel of each of the columns and Group head quarters as the Brigade entered Burma in February that year. It shows us the small number of Column 6 soldiers still available just before they were disbanded and re-distributed amongst the other British units. The title groupings are self explanatory apart from perhaps the ambiguous heading of 'Others'. This, I believe, refers to the mainly Indian orderlies, cooks and camp followers that helped make up the numbers of 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. This is the only time I have seen such a precise document in terms of company numbers and I think it makes for very interesting reading.

Air Supplies

Air supply was provided by a detachment from 31 Squadron of the RAF and operated from Agartala in eastern Bengal. It varied in size during the expedition but seldom exceeded three Hudson and three DC3 aircrafts. Fighter escorts were provided when the range permitted but were not available when emergency drops had to be made at short notice. No aircraft was lost during the operation. The Chindits selected the drop zones when and where required. Initially it was thought that airdrops would only succeed in open clearings, but by chance an emergency airdrop had to be made in jungle terrain, this proved successful and this method was to be used again. Even though the airdrops themselves were successful, the difficulty of the operation meant that on average each man only received half of the rations they required.

NB. Column 5 only received a mere 20 full days rations during the 80 days it spent in Burma that year.

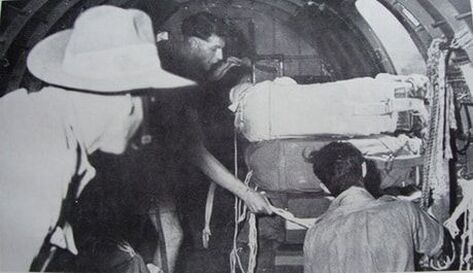

The photo pictured above is a typical preparation for a supply drop, with 'kicker's out' ready to push the required Chindit stores out from the aircraft to the hungry men below.

Into Burma

On the 8th February 1943 the Chindits commenced their advance into Burma from Indian base town of Imphal.

Wingate issued his Order of the Day as the Chindit Columns commenced their crossing of the Chindwin River on 13th February:

Today we stand on the threshold of battle. The time of preparation is over, and we are moving on the enemy to prove ourselves and our methods. At this moment we stand beside the soldiers of the United Nations in the front line trenches throughout the world. It is always a minority that occupies the front line. It is still a smaller minority that accepts with a good heart tasks like this that we have chosen to carry out. We need not, therefore, as we go forward into the conflict, suspect ourselves of selfish or interested motives. We have all had opportunity of withdrawing and we are here because we have chosen to be here; that is, we have chosen to bear the burden and heat of the day. Men who make this choice are above the average in courage. We need therefore have no fear for the staunchness and guts of our comrades.

The motive which has led each and all of us to devote ourselves to what lies ahead cannot conceivably have been a bad motive. Comfort and security are not sacrificed voluntarily for the sake of others by ill-disposed people. Our motive, therefore, may be taken to be the desire to serve our day and generation in the way that seems nearest to our hand. The battle is not always to the strong nor the race to the swift. Victory in war cannot be counted upon, but what can be counted upon is that we shall go forward determined to do what we can to bring this war to the end which we believe best for our friends and comrades in arms, without boastfulness or forgetting our duty, resolved to do the right so far as we can see the right.

Our aim is to make possible a government of the world in which all men can live at peace and with equal opportunity of service.

Finally, knowing the vanity of man's effort and the confusion of his purpose, let us pray that God may accept our services and direct our endeavours, so that when we shall have done all we shall see the fruit of our labours and be satisfied.

O.C. Wingate, Commander,

77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Initially the columns met no opposition, but soon some of the units were sighted by the Japanese, who initially believed them to be small groups gathering intelligence. It was not until there had been a number of engagements with Japanese outposts and patrols and the successful demolition of railway bridges, that the enemy realised the force opposing them was of Brigade strength. The Japanese had been caught by surprise and were confused, not knowing the intention of the Chindits or how they were supplied. Three regiments, each of three battalions, were sent to the area to locate and destroy the invaders. The Chindits now became the hunted.

The Japanese were not aware that the Chindits were being supplied by air and so sent troops westward hoping to cut their land supply routes. On 13th March an airdrop was interrupted and had to be aborted, due to Japanese interference. The Japanese at last realised that the Chindits were being supplied from the air and the enemy troops searching for traditional supply lines were brought back to intensify the hunt for the elusive intruders.

By now the Chindits were deep in enemy territory. Withdrawal would be hazardous as the return route to India required the re-crossing of two major rivers (Irrawaddy and Chindwin), which would now be guarded by the Japanese. Despite this, the Chindits continued their advance eastwards attacking targets as they went.

Pictured below is the Gokteik viaduct in 1945, this was the most southeasterly target considered for destruction on operation Longcloth. Mike Calvert's column 3 were on their way there, when the order came through to return home to India. Frustratingly, this was the second time he had just missed out on destroying the structure, having failed to complete the task the year before on his mischievous retreat out of Burma.

Air supply was provided by a detachment from 31 Squadron of the RAF and operated from Agartala in eastern Bengal. It varied in size during the expedition but seldom exceeded three Hudson and three DC3 aircrafts. Fighter escorts were provided when the range permitted but were not available when emergency drops had to be made at short notice. No aircraft was lost during the operation. The Chindits selected the drop zones when and where required. Initially it was thought that airdrops would only succeed in open clearings, but by chance an emergency airdrop had to be made in jungle terrain, this proved successful and this method was to be used again. Even though the airdrops themselves were successful, the difficulty of the operation meant that on average each man only received half of the rations they required.

NB. Column 5 only received a mere 20 full days rations during the 80 days it spent in Burma that year.

The photo pictured above is a typical preparation for a supply drop, with 'kicker's out' ready to push the required Chindit stores out from the aircraft to the hungry men below.

Into Burma

On the 8th February 1943 the Chindits commenced their advance into Burma from Indian base town of Imphal.

Wingate issued his Order of the Day as the Chindit Columns commenced their crossing of the Chindwin River on 13th February:

Today we stand on the threshold of battle. The time of preparation is over, and we are moving on the enemy to prove ourselves and our methods. At this moment we stand beside the soldiers of the United Nations in the front line trenches throughout the world. It is always a minority that occupies the front line. It is still a smaller minority that accepts with a good heart tasks like this that we have chosen to carry out. We need not, therefore, as we go forward into the conflict, suspect ourselves of selfish or interested motives. We have all had opportunity of withdrawing and we are here because we have chosen to be here; that is, we have chosen to bear the burden and heat of the day. Men who make this choice are above the average in courage. We need therefore have no fear for the staunchness and guts of our comrades.

The motive which has led each and all of us to devote ourselves to what lies ahead cannot conceivably have been a bad motive. Comfort and security are not sacrificed voluntarily for the sake of others by ill-disposed people. Our motive, therefore, may be taken to be the desire to serve our day and generation in the way that seems nearest to our hand. The battle is not always to the strong nor the race to the swift. Victory in war cannot be counted upon, but what can be counted upon is that we shall go forward determined to do what we can to bring this war to the end which we believe best for our friends and comrades in arms, without boastfulness or forgetting our duty, resolved to do the right so far as we can see the right.

Our aim is to make possible a government of the world in which all men can live at peace and with equal opportunity of service.

Finally, knowing the vanity of man's effort and the confusion of his purpose, let us pray that God may accept our services and direct our endeavours, so that when we shall have done all we shall see the fruit of our labours and be satisfied.

O.C. Wingate, Commander,

77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Initially the columns met no opposition, but soon some of the units were sighted by the Japanese, who initially believed them to be small groups gathering intelligence. It was not until there had been a number of engagements with Japanese outposts and patrols and the successful demolition of railway bridges, that the enemy realised the force opposing them was of Brigade strength. The Japanese had been caught by surprise and were confused, not knowing the intention of the Chindits or how they were supplied. Three regiments, each of three battalions, were sent to the area to locate and destroy the invaders. The Chindits now became the hunted.

The Japanese were not aware that the Chindits were being supplied by air and so sent troops westward hoping to cut their land supply routes. On 13th March an airdrop was interrupted and had to be aborted, due to Japanese interference. The Japanese at last realised that the Chindits were being supplied from the air and the enemy troops searching for traditional supply lines were brought back to intensify the hunt for the elusive intruders.

By now the Chindits were deep in enemy territory. Withdrawal would be hazardous as the return route to India required the re-crossing of two major rivers (Irrawaddy and Chindwin), which would now be guarded by the Japanese. Despite this, the Chindits continued their advance eastwards attacking targets as they went.

Pictured below is the Gokteik viaduct in 1945, this was the most southeasterly target considered for destruction on operation Longcloth. Mike Calvert's column 3 were on their way there, when the order came through to return home to India. Frustratingly, this was the second time he had just missed out on destroying the structure, having failed to complete the task the year before on his mischievous retreat out of Burma.

Withdrawal

On 24th March Wingate was ordered to withdraw. By then the Chindits had advanced so far to the east that they were almost out of range for air supply. They also found themselves in an area short of water and heavily patrolled by the Japanese, exhaustion and hunger began to take it's toll. The Japanese had now committed a large force in an attempt to surround and capture the Chindits.

Wingate gave the order to disperse into smaller groups. Non-essential equipment was dumped and mules no longer required were turned loose. By now the Chindits were tired and very short of food, many were wounded or sick, now they faced an arduous journey home pursued by a determined enemy. Many of them would not make it back to India.

One column (seven) made their way out toward China, another (eight) built an airstrip in jungle clearings and evacuated the sick and wounded by air, the rest returned by re-crossing the Irrawaddy and Chindwin Rivers either as a column unit or split into smaller dispersal groups to avoid the Japanese net.

Of the 3,000 officers and men that went into Burma in 1943, only 2,182 came back four months later, having covered between 1,000 and 1,500 miles deep in enemy held territory. They were in poor condition, suffering from tropical diseases and malnutrition but in high spirits and proud of their achievements. Of those that returned only about 600 were passed fit for further active service.

Achievements and Lessons Learned

Longcloth had panache, it had glamour, it had cheek, it had everything the successive Arakan failures lacked. It was the perfect psychological medicine for an Army sadly devoid of confidence in its methods, its purposes and its ability to fulfil them. (Louis Allen).

The Chindits had entered northern Burma, caused some damage to the railway and inflicted minor casualties on the enemy. They had shown that it was possible to infiltrate and operate in difficult jungle terrain deep within enemy held territory.

Wingate had proved his theory of Long Range Penetration could work and that Allied troops could raid effectively behind enemy lines. The use of new styled radio communication and most importantly of all the success of the air supply system were valuable plus points during the 1943 expedition.

The Japanese admitted afterwards that the Chindits had been difficult to deal with and had disrupted their plans to rest their troops in preparation for the invasion of Assam and the battles for Imphal and Kohima. The Mandalay-Myitkyina railway was put out of action for a few weeks forcing the Japanese to use longer and more limiting lines of communications. Between six and eight Japanese battalions had been diverted from other planned operations in order to eradicate the Chindit nuisance.

The Chindits were the first troops to fight back after the defeat in Burma and the operation showed that British troops could take on the Japanese and win. The Japanese had been thought to be invincible jungle fighters, the Chindits proved that this was not so. The legend of the Japanese superman was dealt a savage blow. This had a tremendous effect on the morale of troops in India and the population back home in Britain.

There were problems with the care of the sick and wounded, many had to be abandoned or left in so called friendly Burmese villages. This above all else had caused great consternation amongst the men on the operation, distraught at having to leave behind good friends and brave comrades, when they could no longer march or keep up with the group. As a result, the ability to evacuate sick and wounded became high priority for future missions.

Churchill had been so impressed with the operation that he, along with other Allied leaders, agreed to Wingate’s plans to launch another Chindit expedition the following year. Back in India the foundations were already being laid by General Wavell, but this time on a much larger scale, with six full Brigades making up the newly formed Special Force. This second expedition returned to northern Burma in March 1944. Most of the men in this force would have the luxury of being flown into Burma instead of marching and landed in areas deemed suitable for purpose by reconnaissance from the year before.

Many thanks to Frank Young for allowing me to reproduce his overview and background to Operation Longcloth, taken from his brilliant website 'Chindits, Special Force, Burma 1942-44.'

Below is a typical Chindit dispersal group preparing to move out after a halt. This is almost certainly from the 1944 operation and I cannot recall the source for the photograph, so apologies to whoever that might have been.

On 24th March Wingate was ordered to withdraw. By then the Chindits had advanced so far to the east that they were almost out of range for air supply. They also found themselves in an area short of water and heavily patrolled by the Japanese, exhaustion and hunger began to take it's toll. The Japanese had now committed a large force in an attempt to surround and capture the Chindits.

Wingate gave the order to disperse into smaller groups. Non-essential equipment was dumped and mules no longer required were turned loose. By now the Chindits were tired and very short of food, many were wounded or sick, now they faced an arduous journey home pursued by a determined enemy. Many of them would not make it back to India.

One column (seven) made their way out toward China, another (eight) built an airstrip in jungle clearings and evacuated the sick and wounded by air, the rest returned by re-crossing the Irrawaddy and Chindwin Rivers either as a column unit or split into smaller dispersal groups to avoid the Japanese net.

Of the 3,000 officers and men that went into Burma in 1943, only 2,182 came back four months later, having covered between 1,000 and 1,500 miles deep in enemy held territory. They were in poor condition, suffering from tropical diseases and malnutrition but in high spirits and proud of their achievements. Of those that returned only about 600 were passed fit for further active service.

Achievements and Lessons Learned

Longcloth had panache, it had glamour, it had cheek, it had everything the successive Arakan failures lacked. It was the perfect psychological medicine for an Army sadly devoid of confidence in its methods, its purposes and its ability to fulfil them. (Louis Allen).

The Chindits had entered northern Burma, caused some damage to the railway and inflicted minor casualties on the enemy. They had shown that it was possible to infiltrate and operate in difficult jungle terrain deep within enemy held territory.

Wingate had proved his theory of Long Range Penetration could work and that Allied troops could raid effectively behind enemy lines. The use of new styled radio communication and most importantly of all the success of the air supply system were valuable plus points during the 1943 expedition.

The Japanese admitted afterwards that the Chindits had been difficult to deal with and had disrupted their plans to rest their troops in preparation for the invasion of Assam and the battles for Imphal and Kohima. The Mandalay-Myitkyina railway was put out of action for a few weeks forcing the Japanese to use longer and more limiting lines of communications. Between six and eight Japanese battalions had been diverted from other planned operations in order to eradicate the Chindit nuisance.

The Chindits were the first troops to fight back after the defeat in Burma and the operation showed that British troops could take on the Japanese and win. The Japanese had been thought to be invincible jungle fighters, the Chindits proved that this was not so. The legend of the Japanese superman was dealt a savage blow. This had a tremendous effect on the morale of troops in India and the population back home in Britain.

There were problems with the care of the sick and wounded, many had to be abandoned or left in so called friendly Burmese villages. This above all else had caused great consternation amongst the men on the operation, distraught at having to leave behind good friends and brave comrades, when they could no longer march or keep up with the group. As a result, the ability to evacuate sick and wounded became high priority for future missions.

Churchill had been so impressed with the operation that he, along with other Allied leaders, agreed to Wingate’s plans to launch another Chindit expedition the following year. Back in India the foundations were already being laid by General Wavell, but this time on a much larger scale, with six full Brigades making up the newly formed Special Force. This second expedition returned to northern Burma in March 1944. Most of the men in this force would have the luxury of being flown into Burma instead of marching and landed in areas deemed suitable for purpose by reconnaissance from the year before.

Many thanks to Frank Young for allowing me to reproduce his overview and background to Operation Longcloth, taken from his brilliant website 'Chindits, Special Force, Burma 1942-44.'

Below is a typical Chindit dispersal group preparing to move out after a halt. This is almost certainly from the 1944 operation and I cannot recall the source for the photograph, so apologies to whoever that might have been.

Seen below is a narrative taken from the 23rd Indian Division history in relation to the receiving of returning Chindit soldiers from Operation Longcloth. It shows that there was a great effort made to locate these men in April and May 1943 as they approached and attempted to regain the west banks of the Chindwin River.

Extract from the 23rd Indian Division History 1942-1947

The scheme for the reception of the Wingate force was for the 1st and 49th Brigades to have, near the west bank of the Chindwin, a series of forward reception posts from which the survivors were passed with all speed to Tamu. As part of this scheme, 49 Brigade increased the number of rowers available on our boat service between Yuma and Kyaukchaw by giving some quick instruction to the Mahrattas, who achieved an adequate degree of skill in a short time.

Once at Tamu the survivors were given the best taste of civilisation that we could provide - hot baths, barbers for those who were willing to sacrifice their two months' growth, fresh clothing and boots and food, with a double issue of milk, tea and sugar. After a twenty-four-hour rest, transport was waiting for the last stage of the journey back to Imphal.

But we were far from passive spectators of the return of the exhausted survivors of a gallant expedition. Technical language would describe the Japs as reacting vigorously to the presence of a hostile force in their midst, and everyone knew that Wingate must have a very difficult task to extricate his troops when the order for withdrawal came at the end of March. The Jap, a slow animal in moving to meet the unexpected, at least had the sense to realise that the raiders must go back across the Chindwin and in the area where our troops were known to be.

Hence the task set us, was to draw off the Japs who were watching particularly the area between Mawlaik and Thaungdut, and the result during April was that the ground between Tabaw and Sittaung on the east bank of the river became for about thirty miles inland a vast No Man’s Land where there was a melee of Japs trying to intercept the Wingate force and ourselves trying to distract the Japs, and Wingate’s men trying to reach safety.

The plan was that the Patialas should simulate No. 1 Brigade with a special wireless build-up and the Seaforths form a subsidiary force advancing against Pinlebu and Pinbon respectively from bases at Kaungkasi and Wetauk; whilst the main Head Quarters of the battalions were to remain on the west bank. The Seaforths crossed on March 31st with a company of 3/5 Gurkhas under command, the Patialas a day later, and a dangerous game of hide and seek began with neither side knowing when the other would appear out of the jungle. The Patialas were involved in two clashes in the first week and laid a successful ambush on April 7th, after which they observed the Japs removing seven laden stretchers.

At this point, partly as the first stage in our coming withdrawal during the monsoon and partly to give 37th Brigade more experience after their road-making, 3/5 GR and 3/10 G.R began to take over from the Patialas and the Seaforths, with the command for trans-Chindwin passing to 37 Brigade on the night of April 13th/14th.

From the middle of the month many parties of Wingate’s force reached the river. It was on the 15th that Flight-Lieutenant Thompson (No. 3 Column) and his band bumped into one of the last Patiala posts to be in position. Needless to say, Colonel Balwant Singh was still on the east bank and, after conducting them across the river, he had the pleasure of offering a sample of Patiala hospitality. When they reached the farther bank and safety, the Warrant Officer with the party had marched his men off as though they were on a drill parade. The spirit with which the force set out had not gone, even though the survivors came back half-starved, emaciated and utterly exhausted.

Extract from the 23rd Indian Division History 1942-1947

The scheme for the reception of the Wingate force was for the 1st and 49th Brigades to have, near the west bank of the Chindwin, a series of forward reception posts from which the survivors were passed with all speed to Tamu. As part of this scheme, 49 Brigade increased the number of rowers available on our boat service between Yuma and Kyaukchaw by giving some quick instruction to the Mahrattas, who achieved an adequate degree of skill in a short time.

Once at Tamu the survivors were given the best taste of civilisation that we could provide - hot baths, barbers for those who were willing to sacrifice their two months' growth, fresh clothing and boots and food, with a double issue of milk, tea and sugar. After a twenty-four-hour rest, transport was waiting for the last stage of the journey back to Imphal.

But we were far from passive spectators of the return of the exhausted survivors of a gallant expedition. Technical language would describe the Japs as reacting vigorously to the presence of a hostile force in their midst, and everyone knew that Wingate must have a very difficult task to extricate his troops when the order for withdrawal came at the end of March. The Jap, a slow animal in moving to meet the unexpected, at least had the sense to realise that the raiders must go back across the Chindwin and in the area where our troops were known to be.

Hence the task set us, was to draw off the Japs who were watching particularly the area between Mawlaik and Thaungdut, and the result during April was that the ground between Tabaw and Sittaung on the east bank of the river became for about thirty miles inland a vast No Man’s Land where there was a melee of Japs trying to intercept the Wingate force and ourselves trying to distract the Japs, and Wingate’s men trying to reach safety.

The plan was that the Patialas should simulate No. 1 Brigade with a special wireless build-up and the Seaforths form a subsidiary force advancing against Pinlebu and Pinbon respectively from bases at Kaungkasi and Wetauk; whilst the main Head Quarters of the battalions were to remain on the west bank. The Seaforths crossed on March 31st with a company of 3/5 Gurkhas under command, the Patialas a day later, and a dangerous game of hide and seek began with neither side knowing when the other would appear out of the jungle. The Patialas were involved in two clashes in the first week and laid a successful ambush on April 7th, after which they observed the Japs removing seven laden stretchers.

At this point, partly as the first stage in our coming withdrawal during the monsoon and partly to give 37th Brigade more experience after their road-making, 3/5 GR and 3/10 G.R began to take over from the Patialas and the Seaforths, with the command for trans-Chindwin passing to 37 Brigade on the night of April 13th/14th.

From the middle of the month many parties of Wingate’s force reached the river. It was on the 15th that Flight-Lieutenant Thompson (No. 3 Column) and his band bumped into one of the last Patiala posts to be in position. Needless to say, Colonel Balwant Singh was still on the east bank and, after conducting them across the river, he had the pleasure of offering a sample of Patiala hospitality. When they reached the farther bank and safety, the Warrant Officer with the party had marched his men off as though they were on a drill parade. The spirit with which the force set out had not gone, even though the survivors came back half-starved, emaciated and utterly exhausted.

The 23rd Division history concludes:

The 3/5 GR continued where the Patialas had left off, and the Seaforths, who were not relieved until the 21st, had a very hard last week. On the 16th one of their platoons encountered two companies of Japs, and in the stiff engagement that followed an officer and three other ranks were killed against enemy casualties estimated at forty; another officer and nine other ranks were reported missing after a further skirmish on the 18th; on the 20th a patrol from the west bank ran into a strong Japanese force as it landed; two men were killed and two posted as missing, but the rest of the patrol escaped to safety across the river, covered by the Sergeant in command, who gained the Military Medal for his gallantry.

3/5 GR, who were more fortunate over casualties, had five clashes between the 12th and 25th. After one, a wounded Rifleman who became separated from his party paddled back across the Chindwin using only his hands; on another occasion the interpreter with a patrol was lost after he had been wounded in the pelvis, despite which he swam the Chindwin and reported back to his HQ.; in a third encounter the courage of the commander was rewarded with a Military Cross.

Some indication of the intensity of effort called for is given by the statement that 3/5 GR undertook fifty patrols at this time. The fate of those unfortunate enough to be captured alive is unknown, but a Rifleman of 3/10 GR had an experience that does not encourage the belief that the enemy was anything other than barbarous. He was on a two-man patrol which met a party of about a hundred Japs; his partner escaped, but he was taken prisoner, had his hands tied behind his back and endured the stabs of a bayonet in his face and blows on the head with the butt end of a rifle. By good fortune the Japs ran into another Gurkha patrol of similar strength, took alarm at the first volley and allowed their prisoner to escape.

On the evening of April 28th, a party of five spent and ill-kempt men staggered into the Head Quarters of "B" Company 3/10 GR at Letpantha on the west bank of the river. One of the five was wearing an old, battered pith helmet - Wingate had returned. The war diary records that Major Anderson was of the party, but that is an error; this officer was still on the east bank with the bulk of those that Wingate had led out from the farther side of the Irrawaddy, and it was to organise the extrication of these men who were beset by Jap patrols that Wingate had swum the Chindwin.

That evening Wingate and the Gurkhas went down to the agreed crossing-place, but no signal came from the east bank. During the 29th April, messages came from Anderson fixing a new rendezvous and that night, with the Japs bringing a mortar into action, the Gurkhas rowed across the river and brought out the rest of the party. Their Brigadier was waiting to receive them.

Though small parties continued to straggle back until the middle of May and even later, the burden of our task had been discharged by the end of April and an uneasy quiet settled over the Chindwin front, with the air full of rumours.

NB: The above narrative has highlighted the great efforts made by the 23rd Indian Division in extracting the exhausted Chindits during their final push for liberation. As already mentioned, there was a cost to these participating battalions. On the 26th April 1943, Lt. William Kirkpatrick of the 3/5 Gurkha Rifles was reported as missing in the battalion's war diary, his fate at that time was unknown. Sadly, William had been captured by the Japanese and perished a few weeks later as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail.

The 3/5 GR continued where the Patialas had left off, and the Seaforths, who were not relieved until the 21st, had a very hard last week. On the 16th one of their platoons encountered two companies of Japs, and in the stiff engagement that followed an officer and three other ranks were killed against enemy casualties estimated at forty; another officer and nine other ranks were reported missing after a further skirmish on the 18th; on the 20th a patrol from the west bank ran into a strong Japanese force as it landed; two men were killed and two posted as missing, but the rest of the patrol escaped to safety across the river, covered by the Sergeant in command, who gained the Military Medal for his gallantry.

3/5 GR, who were more fortunate over casualties, had five clashes between the 12th and 25th. After one, a wounded Rifleman who became separated from his party paddled back across the Chindwin using only his hands; on another occasion the interpreter with a patrol was lost after he had been wounded in the pelvis, despite which he swam the Chindwin and reported back to his HQ.; in a third encounter the courage of the commander was rewarded with a Military Cross.

Some indication of the intensity of effort called for is given by the statement that 3/5 GR undertook fifty patrols at this time. The fate of those unfortunate enough to be captured alive is unknown, but a Rifleman of 3/10 GR had an experience that does not encourage the belief that the enemy was anything other than barbarous. He was on a two-man patrol which met a party of about a hundred Japs; his partner escaped, but he was taken prisoner, had his hands tied behind his back and endured the stabs of a bayonet in his face and blows on the head with the butt end of a rifle. By good fortune the Japs ran into another Gurkha patrol of similar strength, took alarm at the first volley and allowed their prisoner to escape.

On the evening of April 28th, a party of five spent and ill-kempt men staggered into the Head Quarters of "B" Company 3/10 GR at Letpantha on the west bank of the river. One of the five was wearing an old, battered pith helmet - Wingate had returned. The war diary records that Major Anderson was of the party, but that is an error; this officer was still on the east bank with the bulk of those that Wingate had led out from the farther side of the Irrawaddy, and it was to organise the extrication of these men who were beset by Jap patrols that Wingate had swum the Chindwin.

That evening Wingate and the Gurkhas went down to the agreed crossing-place, but no signal came from the east bank. During the 29th April, messages came from Anderson fixing a new rendezvous and that night, with the Japs bringing a mortar into action, the Gurkhas rowed across the river and brought out the rest of the party. Their Brigadier was waiting to receive them.

Though small parties continued to straggle back until the middle of May and even later, the burden of our task had been discharged by the end of April and an uneasy quiet settled over the Chindwin front, with the air full of rumours.

NB: The above narrative has highlighted the great efforts made by the 23rd Indian Division in extracting the exhausted Chindits during their final push for liberation. As already mentioned, there was a cost to these participating battalions. On the 26th April 1943, Lt. William Kirkpatrick of the 3/5 Gurkha Rifles was reported as missing in the battalion's war diary, his fate at that time was unknown. Sadly, William had been captured by the Japanese and perished a few weeks later as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail.

Brigadier Wingate and Major Anderson post Longcloth.

Brigadier Wingate and Major Anderson post Longcloth.

On his return to India in late April 1943, Brigadier Wingate had this to say about the men of 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, and about the enemy they had faced in Burma:

The Japanese thought they had found a technique of warfare in the jungles of the Far East to which the United Nations had no answer. With characteristic thoroughness and assiduity, they had not only studied the effects of jungle on all types of modern tactics, but had also trained large numbers of their best troops in the practical application of their approved methods. They boasted that the self-indulgent, ignorant troops of the United Nations could never equal them, either in skill or endurance, in the conditions of warfare that prevailed throughout their co-prosperity sphere.

From Japan to India, from Manchuria to Australasia, jungle and mountain predominate and make penetration, the premier weapon in modern warfare, everywhere possible. The Japanese were mistaken. The British soldier has shown that he can not only equal the Japanese, but surpass him in this very war of penetration in jungle. The reason is to be found in the qualities he (the British soldier) shares with his ancestors: imagination, the ability to give of his best when the audience is smallest, self-reliance and power of individual action. The Indian soldier too, has shown himself fully capable of beating the Japanese in jungle fighting, where individuality and personal initiative are the qualities that count.

Believing that this was so, Field-Marshal Wavell gave me the task of raising and training a formation designed to carry out penetration of the enemy's back areas far deeper and on a far larger scale than anything the Japanese had practised against us. Essential to Wavell's plan was air power not only superior to that of the enemy, but capable of operating in new ways of fulfilling hitherto unheard-of demands. We had such air resources. The R.A.F. never failed us. In fact, seeing in us the ideal opportunity of driving home their own strategic attacks on the enemy, they supplied R.A.F. contingents for every column. And it was largely the presence and work of these R.A.F. elements that made the operation a success.

The force that was to go into the heart of Japanese-occupied Burma and singe the Mikado's beard was not composed of selected troops; it consisted of ordinary British and Indian infantry, sappers, signalmen and others. Each column also had its quota of Burmese troops and without the brave and devoted Burma Rifles the operation would have been impossible. What was it that made these ordinary troops, born and bred for the most part to factories and workshops, capable of feats that would not have disgraced Commandos? The answer is that given imagination and individuality in sufficient quantities, the necessary minimum of training will always produce junior leaders and men capable of beating the unimaginative and stereotyped soldiers of the Axis. Remember too, that all over this theatre of war human beings feel that the United Nations are fighting for something that means more than the severe and macabre ideals of the Axis.

The Japanese soldier is no superman. His operational schemes are the product of a third-rate brain. But the individual soldiers are fanatics. Put one of them in a hole with a hundred rounds of ammunition and tell him to die for the Emperor, and he will do it. The way to deal with him is to leave him in his hole and go behind him. Jungle warfare places a great demand for resourcefulness and endurance on the individual, who may be cut off from his comrades at any time. The Japanese soldier is not resourceful. He is assiduous, hard-working, courageous, and possesses tremendous energy, but he can't solve problems which he has never faced before. The city-bred Englishman, given the right kind of training, meets new and unexpected conditions with imagination and originality.

Although not given to the humourless self-immolation of the Japanese, the British infantryman has a stronger, saner heroism. Most of us are waiting to renew our experience of this dull, ferocious, and poverty-stricken little enemy at the earliest possible moment. Some of us did not come back. They have done something for their country. They have demonstrated a new kind of warfare, the combination of the oldest with the newest methods. They have not been thrown away. We have proved that we can beat the Japanese on his own chosen ground. And as here, so will it be elsewhere.

The Japanese thought they had found a technique of warfare in the jungles of the Far East to which the United Nations had no answer. With characteristic thoroughness and assiduity, they had not only studied the effects of jungle on all types of modern tactics, but had also trained large numbers of their best troops in the practical application of their approved methods. They boasted that the self-indulgent, ignorant troops of the United Nations could never equal them, either in skill or endurance, in the conditions of warfare that prevailed throughout their co-prosperity sphere.

From Japan to India, from Manchuria to Australasia, jungle and mountain predominate and make penetration, the premier weapon in modern warfare, everywhere possible. The Japanese were mistaken. The British soldier has shown that he can not only equal the Japanese, but surpass him in this very war of penetration in jungle. The reason is to be found in the qualities he (the British soldier) shares with his ancestors: imagination, the ability to give of his best when the audience is smallest, self-reliance and power of individual action. The Indian soldier too, has shown himself fully capable of beating the Japanese in jungle fighting, where individuality and personal initiative are the qualities that count.

Believing that this was so, Field-Marshal Wavell gave me the task of raising and training a formation designed to carry out penetration of the enemy's back areas far deeper and on a far larger scale than anything the Japanese had practised against us. Essential to Wavell's plan was air power not only superior to that of the enemy, but capable of operating in new ways of fulfilling hitherto unheard-of demands. We had such air resources. The R.A.F. never failed us. In fact, seeing in us the ideal opportunity of driving home their own strategic attacks on the enemy, they supplied R.A.F. contingents for every column. And it was largely the presence and work of these R.A.F. elements that made the operation a success.

The force that was to go into the heart of Japanese-occupied Burma and singe the Mikado's beard was not composed of selected troops; it consisted of ordinary British and Indian infantry, sappers, signalmen and others. Each column also had its quota of Burmese troops and without the brave and devoted Burma Rifles the operation would have been impossible. What was it that made these ordinary troops, born and bred for the most part to factories and workshops, capable of feats that would not have disgraced Commandos? The answer is that given imagination and individuality in sufficient quantities, the necessary minimum of training will always produce junior leaders and men capable of beating the unimaginative and stereotyped soldiers of the Axis. Remember too, that all over this theatre of war human beings feel that the United Nations are fighting for something that means more than the severe and macabre ideals of the Axis.

The Japanese soldier is no superman. His operational schemes are the product of a third-rate brain. But the individual soldiers are fanatics. Put one of them in a hole with a hundred rounds of ammunition and tell him to die for the Emperor, and he will do it. The way to deal with him is to leave him in his hole and go behind him. Jungle warfare places a great demand for resourcefulness and endurance on the individual, who may be cut off from his comrades at any time. The Japanese soldier is not resourceful. He is assiduous, hard-working, courageous, and possesses tremendous energy, but he can't solve problems which he has never faced before. The city-bred Englishman, given the right kind of training, meets new and unexpected conditions with imagination and originality.

Although not given to the humourless self-immolation of the Japanese, the British infantryman has a stronger, saner heroism. Most of us are waiting to renew our experience of this dull, ferocious, and poverty-stricken little enemy at the earliest possible moment. Some of us did not come back. They have done something for their country. They have demonstrated a new kind of warfare, the combination of the oldest with the newest methods. They have not been thrown away. We have proved that we can beat the Japanese on his own chosen ground. And as here, so will it be elsewhere.

Postscript

On the 24th March 1944 Wingate was lost to his Chindits, when he perished in an air crash whilst returning to India after several meetings with his Chindit Brigade commanders in Burma. His untimely death heralded a change in the tactical use of his troops and brought an unplanned and rather abrupt end to the ideology of long range penetration.

Below is a transcription of the communication of Wingate's death, between the Supreme Allied Commander in theatre, Lord Louis Mountbatten and Prime Minister Winston Churchill:

Letter dated 28th March 1944 and headed Top Secret.

My Dear Prime Minister,

I need not enlarge on the terrible blow which Wingate’s death has dealt to all of us in South East Asia. In the seven months since I have known him we became great personal friends. He always stayed with me in Faridkot House when he came to Delhi and I have visited him on many occasions.

He was not popular with all his seniors, as I think you realise, but when I was at Comilla after the fly-in of his second force had been completed, Slim and Baldwin both told me how reasonable and enthusiastic they had found him. Slim told me that during the days preceding the fly-in, Wingate showed signs of strain, but this I feel, is thoroughly understandable when one thinks of what he has been through.

No one but Wingate could possibly have invented such a bold scheme, devised such an orthodox technique, or trained and inspired his force to an almost fanatical degree of enthusiasm. It was a great help having such a fire-eater on his level. When he wanted to get on with a plan, I only had to back him. It is not going to be easy to try and instil the same degree of enthusiasm from my level, though you can count on me to do what I can.

I will be visiting many areas of the Burma front in the coming days and I plan to see Wingate’s 14th and 23rd Brigades, which are the only two I have never visited. I explained in my recent telegram, the possibility of using Wingate’s death to confuse the Japanese in some way. I believe this might buy us some time and mystify the enemy as to our plans.

No one can say that the formation of South East Asia Command has not caused a considerable diversion of Japanese forces. When I arrived in this theatre there were just four Army Divisions, now there are eight and we believe an ninth is on its way. I am more than ever convinced that you were right to tell me to go to Kandy to form my command. We shall never learn to stand on our own legs if we remain just an off-shoot of GHQ, India.

Yours sincerely, Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten.

Letter dated 30th March 1944 and headed Immediate from London.

Following: Most Secret and Personal from Prime Minister to Admiral Mountbatten.

I am deeply grieved at the loss of this man of genius who might have been a man of destiny and send you my heartfelt sympathy. I have consulted Chiefs of Staff about your thoughts on using Wingate’s death in deception of the enemy. They share my doubts whether it would be effective and may possibly lead to unnecessary and undesirable complications.

We should therefore drop this idea and report this sad event on Saturday April 1st. Moreover, Mrs. Wingate has been informed that an obituary notice will be published in the Times on Saturday.

Signed: W.S.C.

On the 24th March 1944 Wingate was lost to his Chindits, when he perished in an air crash whilst returning to India after several meetings with his Chindit Brigade commanders in Burma. His untimely death heralded a change in the tactical use of his troops and brought an unplanned and rather abrupt end to the ideology of long range penetration.

Below is a transcription of the communication of Wingate's death, between the Supreme Allied Commander in theatre, Lord Louis Mountbatten and Prime Minister Winston Churchill:

Letter dated 28th March 1944 and headed Top Secret.

My Dear Prime Minister,

I need not enlarge on the terrible blow which Wingate’s death has dealt to all of us in South East Asia. In the seven months since I have known him we became great personal friends. He always stayed with me in Faridkot House when he came to Delhi and I have visited him on many occasions.

He was not popular with all his seniors, as I think you realise, but when I was at Comilla after the fly-in of his second force had been completed, Slim and Baldwin both told me how reasonable and enthusiastic they had found him. Slim told me that during the days preceding the fly-in, Wingate showed signs of strain, but this I feel, is thoroughly understandable when one thinks of what he has been through.

No one but Wingate could possibly have invented such a bold scheme, devised such an orthodox technique, or trained and inspired his force to an almost fanatical degree of enthusiasm. It was a great help having such a fire-eater on his level. When he wanted to get on with a plan, I only had to back him. It is not going to be easy to try and instil the same degree of enthusiasm from my level, though you can count on me to do what I can.

I will be visiting many areas of the Burma front in the coming days and I plan to see Wingate’s 14th and 23rd Brigades, which are the only two I have never visited. I explained in my recent telegram, the possibility of using Wingate’s death to confuse the Japanese in some way. I believe this might buy us some time and mystify the enemy as to our plans.

No one can say that the formation of South East Asia Command has not caused a considerable diversion of Japanese forces. When I arrived in this theatre there were just four Army Divisions, now there are eight and we believe an ninth is on its way. I am more than ever convinced that you were right to tell me to go to Kandy to form my command. We shall never learn to stand on our own legs if we remain just an off-shoot of GHQ, India.

Yours sincerely, Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten.

Letter dated 30th March 1944 and headed Immediate from London.

Following: Most Secret and Personal from Prime Minister to Admiral Mountbatten.

I am deeply grieved at the loss of this man of genius who might have been a man of destiny and send you my heartfelt sympathy. I have consulted Chiefs of Staff about your thoughts on using Wingate’s death in deception of the enemy. They share my doubts whether it would be effective and may possibly lead to unnecessary and undesirable complications.

We should therefore drop this idea and report this sad event on Saturday April 1st. Moreover, Mrs. Wingate has been informed that an obituary notice will be published in the Times on Saturday.

Signed: W.S.C.

Those Were The Days!

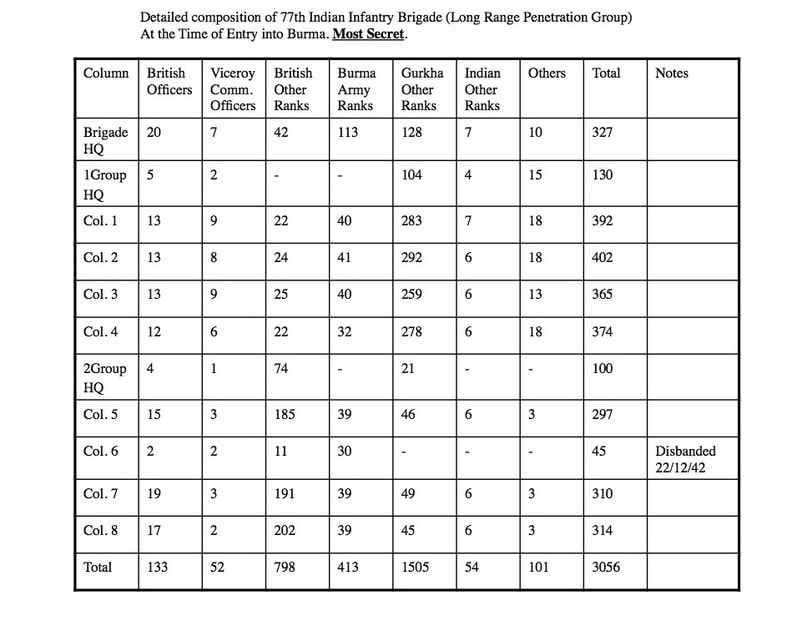

The text below was taken from the Burma Star Association magazine, Dekho! Issue No. 2 1952. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

The text below was taken from the Burma Star Association magazine, Dekho! Issue No. 2 1952. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

The Chindit Legacy

Today, upholding the Chindit legacy rests upon the shoulders of the Chindit Society.

The aims and objectives of the new Society are:

His Royal Highness, The Prince of Wales has maintained a strong interest in the Chindits and has keenly supported the various Chindit organisations over the past thirty years or more. On the occasion of the 60th Anniversary of VJ Day in 2005, he had this to say on the subject:

Ladies and gentlemen, as we commemorate the 60th Anniversary of the end of the Second World War, I just wanted to pay tribute, once again, to the veterans who helped secure an historic victory in South East Asia. Today we remember the appalling losses suffered in the course of defeating Japanese tyranny, but we also give thanks for the courage, resourcefulness and tenacity of the British and Allied Forces in defeating such aggression.

My dear Great Uncle, Lord Mountbatten, used to tell me of the quite atrocious conditions endured by those fighting in Burma — and throughout South East Asia. He told me many other stories too and of his famous soap-box talks to the troops under his command.

They must have had some effect, for in April 1945 he was able to write to my Grandfather, King George VI, that what South East Asia Command did have finally was something which was lacking at the beginning of 1944, which was morale: once you have that, the same troops, with the same equipment, without any rest or re-training, or even new Commander can beat an enemy twice as strong.

The sheer scale of Allied operations in Burma and South East Asia was quite incredible. The 14th Army, led by the inspirational General Slim, (whom I so well remember when I was much younger telling me stories at dinner in Windsor Castle about his exploits during the Gallipoli campaign where he was so badly wounded) was, at its height, nearly 1 million strong and it remains the largest single Army ever formed in time of war, winning 101 battle Honours.

It is so hard for us now, 60 years later, to appreciate fully the extent of what you all endured. Not only was there the brutality of the Japanese to contend with, whether on the battlefield or in the horror of the prison camps, but there was also the additional scourge of sickness, mostly malaria and dysentery which, as Lord Mountbatten reminded the press in August 1944, had claimed close on a quarter of a million casualties amongst Allied Forces since the beginning of that year. And yet, despite all this, so few people seemed to know what heroic tasks you were performing, which must have been profoundly frustrating (but perhaps nothing much changes and our troops today may feel the same!).

Again, in 1944, Lord Mountbatten said 'we do not want a lot of limelight, in fact we do not want any, but I go round and talk to the men in the Command and what worries them is that their wives, their mothers, their daughters, their sweethearts and their sisters don't seem to know that the war they are fighting is important and worthwhile — which, it most assuredly is.' It is, of course, perhaps telling that no fewer that 29 VCs were awarded during the campaign - the largest number in any theatre of war.

It is worth recalling that there were so many exceptionally courageous aircrew and sailors supporting our ground forces. Quite simply operations could not have continued without the pivotal support of British and Allied pilots and aircrew, who not only flew thousands of daring re-supply missions in the most appalling weather conditions imaginable, but also defeated a well equipped and highly motivated Japanese Air Force. And, at sea, the Royal Navy fought with distinction alongside other Allied Navies to destroy the Japanese fleets and gain control of the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

All of this was achieved while the world focused on the war in Europe, which consumed the lion's share of military resources. It is also worth recalling that, unlike the war in Europe, our veterans in South East Asia carried out much of the fighting at very close range, spending many months enduring exceptionally harsh conditions in the jungle.

As Patron of the Chindits' Old Comrades Association, I have, over the last 25 years or so, gained an insight in to the actions of the remarkable men who operated hundreds of miles behind enemy lines. It is wonderful to know that this country of ours still produces equally remarkable people whose bravery and tenacity are truly inspiring.

Let us not forget today the Prisoners of War who suffered so appallingly at the hands of a ruthless and brutal enemy. Over a quarter of all Allied Far East Prisoners of War lost their lives in captivity. The prisoners, including women and even children, endured severe malnutrition, slave labour, illness and disease, and horrendously inhuman treatment from their captors. Around 12,500 British Prisoners of War perished in those vile camps, but the resolve of the British and Allied Forces was unbreakable.

These 60th Anniversary celebrations and commemorations afford us —particularly my generation, the sons and daughters of those who gave the best part of their young lives to secure freedom in South East Asia — the opportunity to pay our deepest respects to all of you, the veterans and survivors of what must have seemed an interminable and terrible campaign. Above all, we remember all your friends and fellow servicemen and women who never returned and we pray your memories and stories will be passed onto the generations of today and tomorrow so that we can learn from the past. Yours is such a special generation — stoical, loyal, indefatigable and dutiful. You have been the bedrock of this country for all these years and it will not be the same without you. We salute you with all our hearts.

Today, upholding the Chindit legacy rests upon the shoulders of the Chindit Society.

The aims and objectives of the new Society are:

- To protect and maintain the legacy and good name of the Chindits and their great deeds during the Burma Campaign.

- To carry that name forward into the public domain, through presentations and education.

- To gather together and keep safe Chindit writings, memoirs and other treasures for the benefit of future generations.

- To assist families and other interested parties in seeking out the history of their Chindit relative or loved one.

- Wherever possible, to ensure the continued well being of all our Chindit veterans.

His Royal Highness, The Prince of Wales has maintained a strong interest in the Chindits and has keenly supported the various Chindit organisations over the past thirty years or more. On the occasion of the 60th Anniversary of VJ Day in 2005, he had this to say on the subject:

Ladies and gentlemen, as we commemorate the 60th Anniversary of the end of the Second World War, I just wanted to pay tribute, once again, to the veterans who helped secure an historic victory in South East Asia. Today we remember the appalling losses suffered in the course of defeating Japanese tyranny, but we also give thanks for the courage, resourcefulness and tenacity of the British and Allied Forces in defeating such aggression.

My dear Great Uncle, Lord Mountbatten, used to tell me of the quite atrocious conditions endured by those fighting in Burma — and throughout South East Asia. He told me many other stories too and of his famous soap-box talks to the troops under his command.

They must have had some effect, for in April 1945 he was able to write to my Grandfather, King George VI, that what South East Asia Command did have finally was something which was lacking at the beginning of 1944, which was morale: once you have that, the same troops, with the same equipment, without any rest or re-training, or even new Commander can beat an enemy twice as strong.

The sheer scale of Allied operations in Burma and South East Asia was quite incredible. The 14th Army, led by the inspirational General Slim, (whom I so well remember when I was much younger telling me stories at dinner in Windsor Castle about his exploits during the Gallipoli campaign where he was so badly wounded) was, at its height, nearly 1 million strong and it remains the largest single Army ever formed in time of war, winning 101 battle Honours.

It is so hard for us now, 60 years later, to appreciate fully the extent of what you all endured. Not only was there the brutality of the Japanese to contend with, whether on the battlefield or in the horror of the prison camps, but there was also the additional scourge of sickness, mostly malaria and dysentery which, as Lord Mountbatten reminded the press in August 1944, had claimed close on a quarter of a million casualties amongst Allied Forces since the beginning of that year. And yet, despite all this, so few people seemed to know what heroic tasks you were performing, which must have been profoundly frustrating (but perhaps nothing much changes and our troops today may feel the same!).

Again, in 1944, Lord Mountbatten said 'we do not want a lot of limelight, in fact we do not want any, but I go round and talk to the men in the Command and what worries them is that their wives, their mothers, their daughters, their sweethearts and their sisters don't seem to know that the war they are fighting is important and worthwhile — which, it most assuredly is.' It is, of course, perhaps telling that no fewer that 29 VCs were awarded during the campaign - the largest number in any theatre of war.

It is worth recalling that there were so many exceptionally courageous aircrew and sailors supporting our ground forces. Quite simply operations could not have continued without the pivotal support of British and Allied pilots and aircrew, who not only flew thousands of daring re-supply missions in the most appalling weather conditions imaginable, but also defeated a well equipped and highly motivated Japanese Air Force. And, at sea, the Royal Navy fought with distinction alongside other Allied Navies to destroy the Japanese fleets and gain control of the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

All of this was achieved while the world focused on the war in Europe, which consumed the lion's share of military resources. It is also worth recalling that, unlike the war in Europe, our veterans in South East Asia carried out much of the fighting at very close range, spending many months enduring exceptionally harsh conditions in the jungle.

As Patron of the Chindits' Old Comrades Association, I have, over the last 25 years or so, gained an insight in to the actions of the remarkable men who operated hundreds of miles behind enemy lines. It is wonderful to know that this country of ours still produces equally remarkable people whose bravery and tenacity are truly inspiring.

Let us not forget today the Prisoners of War who suffered so appallingly at the hands of a ruthless and brutal enemy. Over a quarter of all Allied Far East Prisoners of War lost their lives in captivity. The prisoners, including women and even children, endured severe malnutrition, slave labour, illness and disease, and horrendously inhuman treatment from their captors. Around 12,500 British Prisoners of War perished in those vile camps, but the resolve of the British and Allied Forces was unbreakable.

These 60th Anniversary celebrations and commemorations afford us —particularly my generation, the sons and daughters of those who gave the best part of their young lives to secure freedom in South East Asia — the opportunity to pay our deepest respects to all of you, the veterans and survivors of what must have seemed an interminable and terrible campaign. Above all, we remember all your friends and fellow servicemen and women who never returned and we pray your memories and stories will be passed onto the generations of today and tomorrow so that we can learn from the past. Yours is such a special generation — stoical, loyal, indefatigable and dutiful. You have been the bedrock of this country for all these years and it will not be the same without you. We salute you with all our hearts.

Imphal and the Chindits

by Steve Fogden

The following article was first published in the Yening Hunba magazine back in August this year, as part of the commemorations for the 75th Anniversary of the end of WW2:

During January and February 1943 Imphal was chosen by the then Brigadier Wingate, as the final staging point for his 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, before they pushed on across the Chindwin River and took on the Japanese inside Burma. His Brigade had left Jhansi by rail and journeyed for several days, including by paddle-steamer across the Brahmaputra River, before reaching Dimapur and marching from there to Imphal.

Many of the Chindits from 1943 remarked about the lengthy and arduous march, along the muddy and twisting road that led them to Imphal. This was the last time they ever needed their Army greatcoats to protect them from the freezing temperatures of the hills, whilst marching at night to avoid the busy daytime traffic and to keep their presence on the road a secret. Some of course would never make the return trip, but all at that time were in wonder of the beautiful and majestic scenery.

Wingate chose the pavilion at the town’s golf course to be his temporary map room, as he and his staff made the final preparations for the forthcoming expedition. It was whilst at Imphal that the final decision for Operation Longcloth to go ahead was made. General Wavell famously visited the Chindits at their camp just outside the town on the 6th February and after an intense and protracted meeting with Wingate and the other senior officers present, agreed to let the expedition proceed even though the other elements of the planned offensive had fallen through.

Wavell recalled:

I had to balance the inevitable losses against the experience to be gained of Wingate’s new methods and organisation. I had little doubt in my own mind of the proper course, but I had to satisfy myself that the enterprise had a good chance of success and would not be a senseless sacrifice; and I went into Wingate’s proposals in some detail before giving the sanction to proceed for which he and his brigade were so anxious. I was impressed by what I found and was proud to salute the brigade as it marched out.

The town of Imphal was to play an important role in welcoming back the surviving Chindits from Operation Longcloth. The 19th Casualty Clearing Station was located on the outskirts of the town and was the first medical treatment point for these sick and wounded men, many of whom had spent over 12 weeks behind enemy lines. The makeshift hospital, consisting mainly of rudimentary basha-type huts was run for the most part by Matron Agnes McGearey, who alongside her devoted staff, brought these exhausted and malnourished soldiers back to life. For her efforts in 1943, Agnes McGearey was awarded the MBE.