The Longcloth Family Pages

Over the last 15 years or so I have been extremely lucky to have met or bumped into many families with Longcloth connections. It has been a great source of information for my research and a wonderfully rewarding experience sharing this information with them all.

In the these following pages you will see some of their thoughts and feelings, as they discovered more about their Chindit soldier.

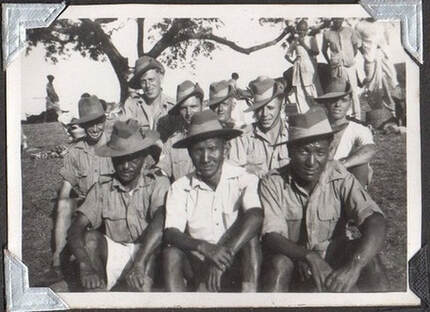

The photo seen to the left was taken in the Central Provinces of India during Longcloth training. My guess is that it is a group of British and Gurkha NCO's who were working together in some kind of training exercise. This typifies the team ethic that was to be found in those Chindit platoons and columns. It is easily forgotten that the men of operation Longcloth were themselves an extended family, consisting of British, Commonwealth and Indian personnel.

(Image courtesy of Peter Brydon).

In the these following pages you will see some of their thoughts and feelings, as they discovered more about their Chindit soldier.

The photo seen to the left was taken in the Central Provinces of India during Longcloth training. My guess is that it is a group of British and Gurkha NCO's who were working together in some kind of training exercise. This typifies the team ethic that was to be found in those Chindit platoons and columns. It is easily forgotten that the men of operation Longcloth were themselves an extended family, consisting of British, Commonwealth and Indian personnel.

(Image courtesy of Peter Brydon).

Liz Hosegood: relative of Wingate's Brigade Intelligence officer

I first made contact with Liz in June 2008. I had seen her enquiry on the Burma Star website asking for information about Captain Graham Hosegood, but unfortunately the post was over 5 years old and the email address she had left was no longer valid. After what can only be described as some persistent detective work, I finally tracked her down.

The photo of Graham (left) is Liz's choice to supplement her feelings about her journey in finding his story. I will say just one other thing here: Graham Hosegood was one of the most respected and well loved officers involved with the operation in 1943, whether it be Wingate himself or simply one of the men under his command, all spoke only good things about him.

Researching into Graham Hosegood.

Captain Graham Hosegood of the 13th Kings Regiment was my father’s cousin, he died aged 24 in Rangoon jail three weeks before liberation. Graham’s short life and involvement in the 2nd World War was always a bit of a mystery to me. My father didn’t really know the details. Joy, Graham’s sister seemed reticent to talk about Graham’s time in the army and his death always seemed to be a very painful memory. I knew for a long time that Joy had Graham’s letters home and his diaries, but I understood, was reluctant to study them too closely as she feared he had been tortured at the hands of the Japanese.

Family History for me has not just been about finding out names and dates, but trying to put flesh on the bone of people’s lives. About 15 years ago I was living near Joy and got to know her better. She happily let me borrow Graham’s letters and diaries which I transcribed. This gave me a skeleton on which to carry out my research, leaving a big gap as most of it was before jungle training, for the Chindits, began.

I knew very little about the 2nd World War in India and Burma so I found books in my local library to try and understand the context in which his experience was happening. The books I found often drew on the experience and memories of those who had been involved and survived. I was very lucky, one actually mentioned Graham. A letter to the author put me in touch with this person’s widow. She very kindly sent me a copy of his written account of his time in the Chindits. This was an invaluable contribution to Graham’s history as they had been in the same dispersal group in Burma avoiding the Japanese and then prisoners together. Wind falls like this are exciting to the family historian as it opens a whole new personal vista.

My second invaluable contact was Stephen Fogden, who has compiled this website – I’m sure he is telling his story elsewhere, but the nature of his researches meant that he was finding information on many of the Chindits. We exchanged what information we found, but I think I was probably the winner. In this way I was put in touch with another survivor of Rangoon who had been in the same room as Graham. We attempted to meet up, but it was unsuccessful. (I am currently living in Zambia.)

You learn as a family historian that you reach a point that you have to make a decision to go ahead and compile your information into a readable format. The research never ends, there is always something else. Finally in 2009 I finished writing Graham’s history.

So why do it? What difference does it make?

Personally I never had any interest in reading about war, but with Graham it became personal. Previously I had no idea who the Chindits were. I felt I got to know Graham as a person, someone I felt I would have liked to have known. Graham’s history also showed me how willing people were to go to war and defend our country – and in Graham’s case were never to see the outcome of their efforts.

When I was still doing my research I talked to my young niece and nephew about Graham and his life. The story captivated them. My niece was to later use Graham in a school project on someone she admired.

Joy, Graham’s sister, felt that the history enabled more people to get to know Graham and what his life had been, it gave it some value. We were able to give copies to all his cousins and their families.

So writing this history was not only for personal interest, but had an impact on the rest of the family too.

The photo of Graham (left) is Liz's choice to supplement her feelings about her journey in finding his story. I will say just one other thing here: Graham Hosegood was one of the most respected and well loved officers involved with the operation in 1943, whether it be Wingate himself or simply one of the men under his command, all spoke only good things about him.

Researching into Graham Hosegood.

Captain Graham Hosegood of the 13th Kings Regiment was my father’s cousin, he died aged 24 in Rangoon jail three weeks before liberation. Graham’s short life and involvement in the 2nd World War was always a bit of a mystery to me. My father didn’t really know the details. Joy, Graham’s sister seemed reticent to talk about Graham’s time in the army and his death always seemed to be a very painful memory. I knew for a long time that Joy had Graham’s letters home and his diaries, but I understood, was reluctant to study them too closely as she feared he had been tortured at the hands of the Japanese.

Family History for me has not just been about finding out names and dates, but trying to put flesh on the bone of people’s lives. About 15 years ago I was living near Joy and got to know her better. She happily let me borrow Graham’s letters and diaries which I transcribed. This gave me a skeleton on which to carry out my research, leaving a big gap as most of it was before jungle training, for the Chindits, began.

I knew very little about the 2nd World War in India and Burma so I found books in my local library to try and understand the context in which his experience was happening. The books I found often drew on the experience and memories of those who had been involved and survived. I was very lucky, one actually mentioned Graham. A letter to the author put me in touch with this person’s widow. She very kindly sent me a copy of his written account of his time in the Chindits. This was an invaluable contribution to Graham’s history as they had been in the same dispersal group in Burma avoiding the Japanese and then prisoners together. Wind falls like this are exciting to the family historian as it opens a whole new personal vista.

My second invaluable contact was Stephen Fogden, who has compiled this website – I’m sure he is telling his story elsewhere, but the nature of his researches meant that he was finding information on many of the Chindits. We exchanged what information we found, but I think I was probably the winner. In this way I was put in touch with another survivor of Rangoon who had been in the same room as Graham. We attempted to meet up, but it was unsuccessful. (I am currently living in Zambia.)

You learn as a family historian that you reach a point that you have to make a decision to go ahead and compile your information into a readable format. The research never ends, there is always something else. Finally in 2009 I finished writing Graham’s history.

So why do it? What difference does it make?

Personally I never had any interest in reading about war, but with Graham it became personal. Previously I had no idea who the Chindits were. I felt I got to know Graham as a person, someone I felt I would have liked to have known. Graham’s history also showed me how willing people were to go to war and defend our country – and in Graham’s case were never to see the outcome of their efforts.

When I was still doing my research I talked to my young niece and nephew about Graham and his life. The story captivated them. My niece was to later use Graham in a school project on someone she admired.

Joy, Graham’s sister, felt that the history enabled more people to get to know Graham and what his life had been, it gave it some value. We were able to give copies to all his cousins and their families.

So writing this history was not only for personal interest, but had an impact on the rest of the family too.

Lynn Ventre: granddaughter of Pte. William Ventre

I replied to a post left by Lynn on one of the many Chindit websites (I think it was the Ian Lambert site) in November 2008. Her Grandad William was one of the first men from 1943 who I had traced that actually survived Longcloth and returned home. Lynn has been fantastic in her support for this website and our two family stories although very different in their outcome, share massive emotional similarities, none more so than the understanding of the wife's or widow's perspective during those difficult times.

Here is what she has contributed from her family:

William Ventre was among the first generation of Italian descendants born in Liverpool.

His father was one of many Italian immigrants to make a home in an area off Scotland Road which became known as Little Italy, making the family a notable part of the city’s history.

William grew up around the corner from his future wife Margaret Singleton and the pair soon fell in love after attending St Joseph’s school together with just a year between them.

They married and had their first child Billy before William was sent to Burma with the Duke of Wellington’s regiment, playing a crucial role for nearly five years. He was one of the Chindits, the largest of the allied Special Forces of World War II. They operated deep behind enemy lines in the jungle where William survived malaria at least a dozen times.

On his return, the couple had six more children, Rita, Lawrence, Maureen, Beth, Cathy and Francis. Later 15 grandchildren and 16 great-grandchildren followed.

Margaret worked morning and night cleaning the banks in Liverpool, but when she was at home she was rarely out of the kitchen. She fed everyone who stepped over her doorstep and was proud of her recipes.

Margaret attended mass for over 40 years and never went into a pub. She said she had far more important things to do.

William served for many years with the army, mainly as a mechanical engineer for the King’s regiment. Thankfully, he was frequently on leave as a reward for winning the army’s boxing competitions. He never lost a fight. William also worked for the TA teaching cadets to drive, receiving a long service award for his dedication.

In Liverpool, William worked on the docks and only stopped through severe arthritis. He worked long hours in all weathers and when he retired could barely use his hands.

Daughter Beth said: “We are such a close family. Our mum and dad knew how much we loved them but they did not know how proud we are of them. Their legacy will live on.”

Now to remember them the family listen to Margaret’s favourite song Unforgettable by Nat King Cole, which is what they both were to their family, simply unforgettable.

Margaret Ventre-November 4th 1920-May 23rd 2006.

William Ventre-April 20th 1920-May 22nd 1990.

Here is what she has contributed from her family:

William Ventre was among the first generation of Italian descendants born in Liverpool.

His father was one of many Italian immigrants to make a home in an area off Scotland Road which became known as Little Italy, making the family a notable part of the city’s history.

William grew up around the corner from his future wife Margaret Singleton and the pair soon fell in love after attending St Joseph’s school together with just a year between them.

They married and had their first child Billy before William was sent to Burma with the Duke of Wellington’s regiment, playing a crucial role for nearly five years. He was one of the Chindits, the largest of the allied Special Forces of World War II. They operated deep behind enemy lines in the jungle where William survived malaria at least a dozen times.

On his return, the couple had six more children, Rita, Lawrence, Maureen, Beth, Cathy and Francis. Later 15 grandchildren and 16 great-grandchildren followed.

Margaret worked morning and night cleaning the banks in Liverpool, but when she was at home she was rarely out of the kitchen. She fed everyone who stepped over her doorstep and was proud of her recipes.

Margaret attended mass for over 40 years and never went into a pub. She said she had far more important things to do.

William served for many years with the army, mainly as a mechanical engineer for the King’s regiment. Thankfully, he was frequently on leave as a reward for winning the army’s boxing competitions. He never lost a fight. William also worked for the TA teaching cadets to drive, receiving a long service award for his dedication.

In Liverpool, William worked on the docks and only stopped through severe arthritis. He worked long hours in all weathers and when he retired could barely use his hands.

Daughter Beth said: “We are such a close family. Our mum and dad knew how much we loved them but they did not know how proud we are of them. Their legacy will live on.”

Now to remember them the family listen to Margaret’s favourite song Unforgettable by Nat King Cole, which is what they both were to their family, simply unforgettable.

Margaret Ventre-November 4th 1920-May 23rd 2006.

William Ventre-April 20th 1920-May 22nd 1990.

Les Bourne: best friend of Fred Hartnell

I wrote to Les Bourne in August 2009 after seeing his memoir on the Witheridge village website. We then swapped several letters and spoke a few times on the telephone. He had almost exactly the same accent and voice as the last WW1 veteran Harry Patch, it was uncanny. Always full of great stories and never without a little anecdote or joke, he had me smiling during our conversations on the phone. One of these involved a local farmer managing to sell one single crop of swedes to the War Office, no fewer than 3 times!

More importantly, here are his thoughts about his best mate Fred:

Learning that Fred had died was a big blow for me and my family, it was like losing a brother. We lived quite near each other in Witheridge village in Devon and we started school on the same day and became great pals.

On leaving school we both went to work in the same firm, learning the trade as carpenters. But the war came and we were both called up, along with most of the other lads in the Territorial Army at the time. We had joined the TA in 1938 and always hoped that we could remain together as a group. This didn't happen and we all went our separate ways.

We were all in the 6th battalion of the Devonshire Regiment to begin with, but the sergeant in charge said that too many boys from the same village could not stay together in case we all went in one go whilst in action. Another battalion was drawn up and that became the 9th Devon's. I forgot to say, none of Fred's family are still alive, they were a lovely family and we all lived in one another's pockets through our childhood years. As a group we always helped each other out and fought each other's battles when trouble was about.

Many times I think about Fred and what might of happened to him and now I know. Another of our mates Percy Chapple was also killed in Burma. He was a big lad and the only boy in a family of six children. I remember when we called for him on the way to school his older sisters were always trying to get his boots on for him. Poor old Percy, he hated school!

Witheridge was quite a big Parish, but only two of the farmer's sons ended up in the forces, this didn't go down too well with my mother I can tell you.

All the boys from the Devon's had service numbers beginning 562, it didn't matter if you changed battalion or even regiment, you always kept the same number. The photo I have sent you was taken in my father's garden, when we were all back on our first leave. Fred is on the extreme right with his arm round my sister, my brother is peeking out from behind the lad in the peak cap. Sometimes there were 15 or 16 of us on leave, my Mum certainly used to have a house full. She enjoyed every minute of it, honestly.

Thank you for all you have sent me Steve, it isn't a happy thing to learn, but it has made me think of Fred and those days and that is no bad thing at all.

Fred Hartnell's Chindit story can be seen in the section 'The Men'.

More importantly, here are his thoughts about his best mate Fred:

Learning that Fred had died was a big blow for me and my family, it was like losing a brother. We lived quite near each other in Witheridge village in Devon and we started school on the same day and became great pals.

On leaving school we both went to work in the same firm, learning the trade as carpenters. But the war came and we were both called up, along with most of the other lads in the Territorial Army at the time. We had joined the TA in 1938 and always hoped that we could remain together as a group. This didn't happen and we all went our separate ways.

We were all in the 6th battalion of the Devonshire Regiment to begin with, but the sergeant in charge said that too many boys from the same village could not stay together in case we all went in one go whilst in action. Another battalion was drawn up and that became the 9th Devon's. I forgot to say, none of Fred's family are still alive, they were a lovely family and we all lived in one another's pockets through our childhood years. As a group we always helped each other out and fought each other's battles when trouble was about.

Many times I think about Fred and what might of happened to him and now I know. Another of our mates Percy Chapple was also killed in Burma. He was a big lad and the only boy in a family of six children. I remember when we called for him on the way to school his older sisters were always trying to get his boots on for him. Poor old Percy, he hated school!

Witheridge was quite a big Parish, but only two of the farmer's sons ended up in the forces, this didn't go down too well with my mother I can tell you.

All the boys from the Devon's had service numbers beginning 562, it didn't matter if you changed battalion or even regiment, you always kept the same number. The photo I have sent you was taken in my father's garden, when we were all back on our first leave. Fred is on the extreme right with his arm round my sister, my brother is peeking out from behind the lad in the peak cap. Sometimes there were 15 or 16 of us on leave, my Mum certainly used to have a house full. She enjoyed every minute of it, honestly.

Thank you for all you have sent me Steve, it isn't a happy thing to learn, but it has made me think of Fred and those days and that is no bad thing at all.

Fred Hartnell's Chindit story can be seen in the section 'The Men'.

Sylvia Frank, wife of Pte. Leon Frank, column 7.

In early 2010 I decided to take one of those chances and write off to the family of Leon Frank, asking for details of his service in Burma in 1943. I knew that Leon had died in 2003, but thought I might be lucky enough to still make contact with his family.

Leon (pictured left, photo taken in Secunderabad, India) had given several interviews to authors and researchers involved in the telling of the Chindit 1 story. He had also been a regular attendee of the Rangoon Jail ex-POW association, which had been created and organised by Karnig Thomassian and his wife Diane.

Karnig was an American airman who had been captured in Burma after his aircraft had crashed in late 1944. It was from these association records that I had found Leon’s last known address. It should be remembered here that at the time of writing to the Frank family, I had no idea of Grandad’s connection with Leon and the other 4 men from the Lonsa village dispersal group.

This was the reply I received from Leon’s widow, Sylvia:

Dear Mr. Fogden

Thank you for your letter. I hope the information which I am giving to you will help in your research.

My husband Leon Frank was captured on his 21st birthday. He spent two years in Rangoon. As far as I can make out, your grandfather must have died before my husband arrived.

There is a book written by Philip D. Chinnery, called ‘March or Die’, telling about the Chindits, my husband is mentioned on pages 75-76-77-80 and 81, also there are a few photos. I would expect you might be able to get this from your local library.

Unfortunately my husband passed away in April 2003 aged nearly 83. The Imperial War Museum have a tape of his exploits, from when he was interviewed at home. If you visit the museum I am sure you can listen to the recording.

We kept in touch for a number of years with some of he Ex-POW’s from Rangoon, but sadly they have all passed away. Leon was a good man and tried desperately to make sure these men were remembered, especially the soldiers who did not return.

I hope I have been of some help to you and I wish you the best for the New Year and good health always.

Yours sincerely

Mrs. Sylvia G. Frank

PS. I have done my best writing at 88!

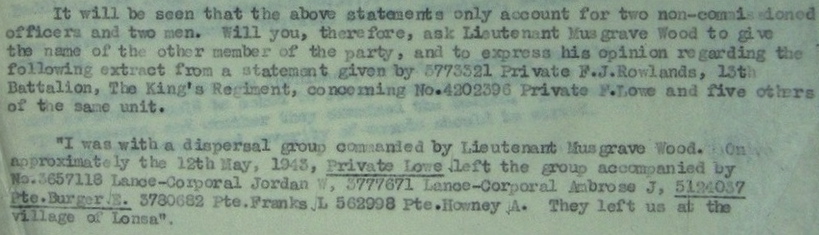

It was just 10 months after receiving Sylvia's kind letter, that I discovered the witness statements for the 13th King's and Leon's part in my Grandad's story. See the excerpt below from one of those reports, as given by Pte. F.J. Rowlands. As you can see Leon and Grandad sit side by side in the short narrative.

Leon (pictured left, photo taken in Secunderabad, India) had given several interviews to authors and researchers involved in the telling of the Chindit 1 story. He had also been a regular attendee of the Rangoon Jail ex-POW association, which had been created and organised by Karnig Thomassian and his wife Diane.

Karnig was an American airman who had been captured in Burma after his aircraft had crashed in late 1944. It was from these association records that I had found Leon’s last known address. It should be remembered here that at the time of writing to the Frank family, I had no idea of Grandad’s connection with Leon and the other 4 men from the Lonsa village dispersal group.

This was the reply I received from Leon’s widow, Sylvia:

Dear Mr. Fogden

Thank you for your letter. I hope the information which I am giving to you will help in your research.

My husband Leon Frank was captured on his 21st birthday. He spent two years in Rangoon. As far as I can make out, your grandfather must have died before my husband arrived.

There is a book written by Philip D. Chinnery, called ‘March or Die’, telling about the Chindits, my husband is mentioned on pages 75-76-77-80 and 81, also there are a few photos. I would expect you might be able to get this from your local library.

Unfortunately my husband passed away in April 2003 aged nearly 83. The Imperial War Museum have a tape of his exploits, from when he was interviewed at home. If you visit the museum I am sure you can listen to the recording.

We kept in touch for a number of years with some of he Ex-POW’s from Rangoon, but sadly they have all passed away. Leon was a good man and tried desperately to make sure these men were remembered, especially the soldiers who did not return.

I hope I have been of some help to you and I wish you the best for the New Year and good health always.

Yours sincerely

Mrs. Sylvia G. Frank

PS. I have done my best writing at 88!

It was just 10 months after receiving Sylvia's kind letter, that I discovered the witness statements for the 13th King's and Leon's part in my Grandad's story. See the excerpt below from one of those reports, as given by Pte. F.J. Rowlands. As you can see Leon and Grandad sit side by side in the short narrative.

Sheila Wilson, niece of William McIntyre

In the summer of 2010 some photos of William McIntyre were posted on the Special Forces website. I left a note next to these images in the hope that eventually the family might see it and make contact, this duly happened in December that same year.

It was wonderful to make contact with Sheila, Wes and Tim Wilson and to exchange details and information about William, who had been Sheila’s Uncle.

Here is how Sheila remembers her Uncle from the early 1940’s:

I was a little girl when he went away; memories are there because he was a larger than life character to me. He played Blueberry Hill on the piano, my Mum’s pride and joy and he would constantly scratch the polished wood with his army boots, those scratches remained long after he was gone.

He was always ready to kick a ball around the garden and he and my Dad had long discussions about the world's problems, When he would stay over at the house I would always hear them talking about things sometimes they would raise their voices. Uncle Billy had been rescued from the beaches at Dunkirk and my father worried about him all the time, he would laugh and say he could take care of himself.

I remember getting a frilly new dress to attend his wedding, which I think, was a surprise to the family, I thought his bride (I think they called her Tessie) looked like a princess and I remember the cake was delicious. Tessie disappeared from my life soon after William left for the Far East and the contact with him was sporadic since he moved from India to Burma. His death was not confirmed till I think 1948. My Aunt Esther, his older sister who really raised him was devastated and would go to the Cable and Wireless in Liverpool almost every week. I never knew what happened to him until Tim got the address at the Ministry of Defence who sent us the web site of the monument in Rangoon. He was full of life and curious about everything, quiet and determined and his loss was keenly felt in the family, especially my Dad.

Sheila also told me in one of our email conversations that:

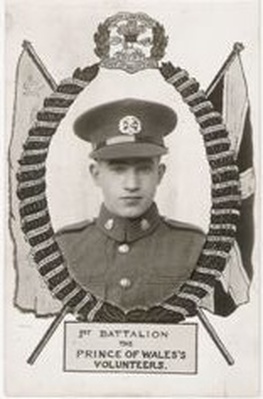

"I have an old photo with regimental flags and underneath it says 1st Battalion, Prince of Wales Volunteers (William’s first regiment). He looks very young and some of the family always said he lied about his age to get in to the military and was 18 when he was rescued from Dunkirk. So much to learn and so many mixed emotions." The photo that Sheila mentions is the one shown above.

"Tim forwarded all of the paperwork that you sent to him; I was very touched to have especially the eyewitness account. My Dad never really ever knew this information and died not knowing."

Sheila’s son Tim told me that:

"William joined up underage--he was 17. He turned 18 waiting to be picked up at Dunkirk as he was in France with the BEF (3d Infantry Division) and was evacuated. As you probably know, the 13th King’s were combed out after that campaign and personnel were sent to India, William among them. I've always found it ironic that he escaped from France only to die in Burma. Would his chances have been better as a German POW? Maybe, but who knows. Such are the vagaries of fate."

"My Mom told me they did not get confirmation of William's death until 1948--he was officially MIA until then."

William and my Grandfather were not in the same column in 1943, but it is possible that they crossed paths in that last few weeks as both men attempted to escape Burma via China. What is for sure is that both men were extremely unlucky in May that year, William for falling ill so close to freedom and Grandad for being captured by the Japanese having run out of food and the energy to continue marching.

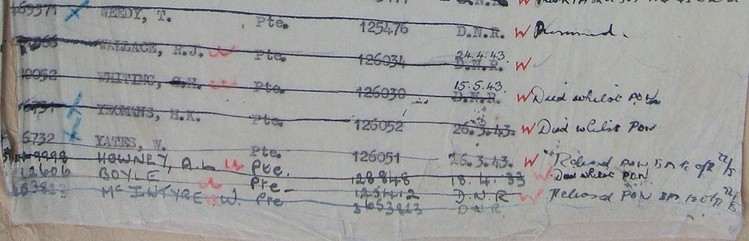

Here is the last page of the original handwritten ‘Missing in Action’ nominal rolls from 1943. It is uncanny how both men are shown together at the very bottom of the page. Sadly, this also meant that the respective families had the long and agonizing wait for news, which in the end proved so heartbreaking.

It was wonderful to make contact with Sheila, Wes and Tim Wilson and to exchange details and information about William, who had been Sheila’s Uncle.

Here is how Sheila remembers her Uncle from the early 1940’s:

I was a little girl when he went away; memories are there because he was a larger than life character to me. He played Blueberry Hill on the piano, my Mum’s pride and joy and he would constantly scratch the polished wood with his army boots, those scratches remained long after he was gone.

He was always ready to kick a ball around the garden and he and my Dad had long discussions about the world's problems, When he would stay over at the house I would always hear them talking about things sometimes they would raise their voices. Uncle Billy had been rescued from the beaches at Dunkirk and my father worried about him all the time, he would laugh and say he could take care of himself.

I remember getting a frilly new dress to attend his wedding, which I think, was a surprise to the family, I thought his bride (I think they called her Tessie) looked like a princess and I remember the cake was delicious. Tessie disappeared from my life soon after William left for the Far East and the contact with him was sporadic since he moved from India to Burma. His death was not confirmed till I think 1948. My Aunt Esther, his older sister who really raised him was devastated and would go to the Cable and Wireless in Liverpool almost every week. I never knew what happened to him until Tim got the address at the Ministry of Defence who sent us the web site of the monument in Rangoon. He was full of life and curious about everything, quiet and determined and his loss was keenly felt in the family, especially my Dad.

Sheila also told me in one of our email conversations that:

"I have an old photo with regimental flags and underneath it says 1st Battalion, Prince of Wales Volunteers (William’s first regiment). He looks very young and some of the family always said he lied about his age to get in to the military and was 18 when he was rescued from Dunkirk. So much to learn and so many mixed emotions." The photo that Sheila mentions is the one shown above.

"Tim forwarded all of the paperwork that you sent to him; I was very touched to have especially the eyewitness account. My Dad never really ever knew this information and died not knowing."

Sheila’s son Tim told me that:

"William joined up underage--he was 17. He turned 18 waiting to be picked up at Dunkirk as he was in France with the BEF (3d Infantry Division) and was evacuated. As you probably know, the 13th King’s were combed out after that campaign and personnel were sent to India, William among them. I've always found it ironic that he escaped from France only to die in Burma. Would his chances have been better as a German POW? Maybe, but who knows. Such are the vagaries of fate."

"My Mom told me they did not get confirmation of William's death until 1948--he was officially MIA until then."

William and my Grandfather were not in the same column in 1943, but it is possible that they crossed paths in that last few weeks as both men attempted to escape Burma via China. What is for sure is that both men were extremely unlucky in May that year, William for falling ill so close to freedom and Grandad for being captured by the Japanese having run out of food and the energy to continue marching.

Here is the last page of the original handwritten ‘Missing in Action’ nominal rolls from 1943. It is uncanny how both men are shown together at the very bottom of the page. Sadly, this also meant that the respective families had the long and agonizing wait for news, which in the end proved so heartbreaking.

This is what we know about William McIntyre’s time in Burma:

William found himself in column 7 on operation Longcloth and was possibly a member of Erik Petersen’s platoon number 15. As such, he would have had a very varied and exciting time during the early weeks of the operation. Petersen (pictured, right) had formed part of the protection flank for Wingate’s own HQ during February and March that year, but had lost contact with the main body of column 7 shortly after.

They moved independently for a number of days until finally stumbling across column 3 as it prepared to blow the railway bridges and tracks at Nankan. Petersen’s men helped stave off a Japanese counter attack at the station by joining in with Calvert’s men and killing two-lorry load of enemy infantry.

Back once more with his own column, Petersen with his platoon alongside and William included, played a major roll in protecting the outskirts of the village named Baw, where Wingate was attempting to take a massive air supply drop. Here under fire from the enemy defensive positions Petersen was seriously wounded.

Platoon 15 were next involved in the provision of a bridgehead protection for the column’s attempt to cross the Shweli River in early April 1943. The commanding officer Major Gilkes had often considered attempting dispersal via the Chinese province of Yunnan and had even discussed this idea with Wingate himself. This is the route that the vast majority of column 7 took in exiting Burma; Petersen still wounded and strapped to a horse went with the largest party, led by Major Gilkes.

At the Shweli rendezvous many of the men from columns 5 and 7 had become inter mixed, so it is impossible to be sure which dispersal group William may have been part of. It is likely that he remained with the larger dispersal group under Ken Gilkes as they headed out toward the Chinese borders. We do know that William made it as far as Fort Morton, but had become too ill to continue.

Here is the witness report by 3779384 Pte. J. Greavey, 13th battalion King’s Regiment.

Dated 27/11/1943.

“I was a member of 15 Platoon, 7 Column, in Brigadier Wingate’s expedition into Burma from January to June 1943.

About the third week in May I was a member of a small party of about six men marching North-east towards the China border. Pte. McCartney was in charge of the party and we eventually arrived at Fort Morton.

We there saw Pte. McIntyre; he had been ill for two days, and during this period he had been cared for by Chinese villagers. Our party stayed at Fort Morton for one night and set out on our journey the next morning. Pte. McIntyre, who was feeling a little better stated that he thought he was capable of continuing the journey with us; however after about a half hour’s march he took ill again, and set out on his own to Fort Morton.

That was the last we saw of him on approximately 20/05/43. He had neither arms or equipment, but I think he was in possession of about 30 rupees in money".

Signed: J. Greavey.

William sadly died the next day.

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2516202/McINTYRE,%20WILLIAM

Below are two photos of William, taken at Saugor during Chindit training in 1942.

William found himself in column 7 on operation Longcloth and was possibly a member of Erik Petersen’s platoon number 15. As such, he would have had a very varied and exciting time during the early weeks of the operation. Petersen (pictured, right) had formed part of the protection flank for Wingate’s own HQ during February and March that year, but had lost contact with the main body of column 7 shortly after.

They moved independently for a number of days until finally stumbling across column 3 as it prepared to blow the railway bridges and tracks at Nankan. Petersen’s men helped stave off a Japanese counter attack at the station by joining in with Calvert’s men and killing two-lorry load of enemy infantry.

Back once more with his own column, Petersen with his platoon alongside and William included, played a major roll in protecting the outskirts of the village named Baw, where Wingate was attempting to take a massive air supply drop. Here under fire from the enemy defensive positions Petersen was seriously wounded.

Platoon 15 were next involved in the provision of a bridgehead protection for the column’s attempt to cross the Shweli River in early April 1943. The commanding officer Major Gilkes had often considered attempting dispersal via the Chinese province of Yunnan and had even discussed this idea with Wingate himself. This is the route that the vast majority of column 7 took in exiting Burma; Petersen still wounded and strapped to a horse went with the largest party, led by Major Gilkes.

At the Shweli rendezvous many of the men from columns 5 and 7 had become inter mixed, so it is impossible to be sure which dispersal group William may have been part of. It is likely that he remained with the larger dispersal group under Ken Gilkes as they headed out toward the Chinese borders. We do know that William made it as far as Fort Morton, but had become too ill to continue.

Here is the witness report by 3779384 Pte. J. Greavey, 13th battalion King’s Regiment.

Dated 27/11/1943.

“I was a member of 15 Platoon, 7 Column, in Brigadier Wingate’s expedition into Burma from January to June 1943.

About the third week in May I was a member of a small party of about six men marching North-east towards the China border. Pte. McCartney was in charge of the party and we eventually arrived at Fort Morton.

We there saw Pte. McIntyre; he had been ill for two days, and during this period he had been cared for by Chinese villagers. Our party stayed at Fort Morton for one night and set out on our journey the next morning. Pte. McIntyre, who was feeling a little better stated that he thought he was capable of continuing the journey with us; however after about a half hour’s march he took ill again, and set out on his own to Fort Morton.

That was the last we saw of him on approximately 20/05/43. He had neither arms or equipment, but I think he was in possession of about 30 rupees in money".

Signed: J. Greavey.

William sadly died the next day.

www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2516202/McINTYRE,%20WILLIAM

Below are two photos of William, taken at Saugor during Chindit training in 1942.

My great thanks go to Sheila, Wes and Tim Wilson for their kind help and involvement in telling William McIntyre's story.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and all family contributors 2011.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and all family contributors 2011.