More Longcloth Cemeteries and Memorials

Maymyo Concentration Camp

"The whole time we were at Maymyo we felt we were living on the edge of a volcano and at every step we expected a snarling little tornado to appear and beat us up." (Lieutenant Philip Stibbe recounting the days at Maymyo in 1943).

As more and more of the men from Operation Longcloth became prisoners of war, the Japanese decide to move the captured Chindits to a larger camp in the hill station town of Maymyo. It was here that things really began to turn sour for the prisoners. Treatment at Maymyo Camp was severe and the guards also insisted on the POW's learning all commands and drills in the Japanese language. Failure to comply with these orders would often result in a beating and it was in Maymyo that the first Chindit POW deaths began to occur. It is suggested that the camp was located somewhere near to the rail station and quite close to the Bush Warfare School where Mike Calvert and the 142 Commandos had trained just a few months before.

It is difficult to say for sure how many men were held at Maymyo, but by the middle of May there were probably the best part of 200 men present in the camp. Conditions and treatment at Maymyo, combined with the exhaustion and starvation of the expedition meant that men began to fall ill and ultimately die in the cramped sheds, which were no bigger than the bathing huts found at English seaside resorts. I would estimate that approximately 20 men died at Maymyo, with perhaps another 10 or so losing their fight for life when the Chindits were eventually moved down to Rangoon in late May or early June. I first thought that all 200 or so Chindits were sent by rail to Rangoon in one group, but recent documents have shown that this was not the case. Several journeys were needed to transport them all to the city jail and this took two or three weeks to complete.

Here are some memories of the camp from Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding, this young officer was a member of Wingate's Head Quarters and had been captured after failing to cross the Irrawaddy in late April 1943.

"After some time we were sent to Maymyo, to a sort of 'Hell Camp' where we were supposed to learn Japanese drill. Believe it or not, the Japanese for 'Right turn' is 'Migi Mugi Migi'. Of course it doesn't sound like that any more than an English sergeant bellowing "Right turn" sounds like that, but you will see our difficulty in understanding these commands.

It was here that we met the 'landsturmer' type of Jap. And he is a bad type. (Landsturmer is a German colloquial word for a third class infantryman or soldier).

In the compound there was a 'one holer' (a single latrine). Each morning we had to line up with our chamber pots to empty them therein. In the camp there was an Anglo-Burmese family - father, mother, and two teenaged daughters. One of the girls, scarlet in the face, lined up with the troops, many, if not all, in a desperate hurry. They ALL stood back and said, "After you, Miss." It may seem dotty in the circumstances, but I was very proud of them.

We drew our rice in wooden buckets which we were supposed to wash up and return. In those days I was not the accomplished 'washerupper' that I am today, and I must have missed a grain or two. I gave my bucket to one of the cooks (a Burman), who remonstrated, but I paid no heed.

A bit later the cook and our Jap drill instructor arrived, the cook bearing my bucket. The Jap carried a teak club fashioned in the shape of a samurai sword, very dangerous looking. We were just standing about. The unwritten law was that if you saw trouble coming and knew it was yours, you told your friends and they faded away. There was no point in getting others involved, but it was pretty lonely business.

Up they came and the Jap said something or other. It sounded pretty hostile to me, so I said, "Wakeru nai", which means, I think, "I do not understand". This was always the first (and often the last) line of defence.

The cook, bless him, said, "Hey Johnnie." That was his big mistake. The Jap looked at me and said, "Shoko?", which means,"Officer?" I said "Hai", which means "Yes". He then said to the cook,"Bo-jee"; this is the Burmese for "Officer". The cook indicated that he knew this. Whereupon the Jap gave me a little bow and drove the cook away beating him about the shoulders.

I can only suppose that while he, the Jap, had not the slightest compunction about beating up an Allied Officer, he was hanged if a non-combatant was going to be rude to one. I was a bit relieved because if he had hit me over the head my skull would most certainly have been fractured. I did not wash up again.

After Maymyo we had a perfectly foul journey, in very hot, metal, closed doored railway trucks to Rangoon and were then marched from the station to Rangoon Central Jail in Commissioner Road."

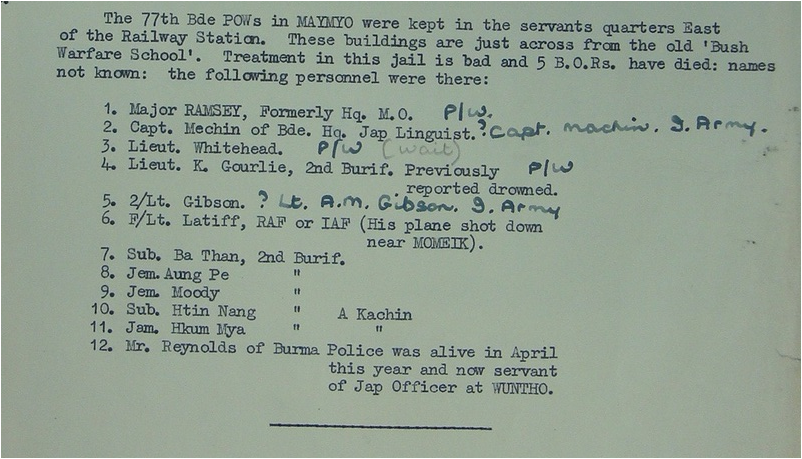

Below is a page from a Kachin Levees intelligence report, the Kachins were a tribe from within Burma who had remained totally loyal to the British throughout and indeed after the war. The report gives some minor details about the location and conditions at Maymyo.

As more and more of the men from Operation Longcloth became prisoners of war, the Japanese decide to move the captured Chindits to a larger camp in the hill station town of Maymyo. It was here that things really began to turn sour for the prisoners. Treatment at Maymyo Camp was severe and the guards also insisted on the POW's learning all commands and drills in the Japanese language. Failure to comply with these orders would often result in a beating and it was in Maymyo that the first Chindit POW deaths began to occur. It is suggested that the camp was located somewhere near to the rail station and quite close to the Bush Warfare School where Mike Calvert and the 142 Commandos had trained just a few months before.

It is difficult to say for sure how many men were held at Maymyo, but by the middle of May there were probably the best part of 200 men present in the camp. Conditions and treatment at Maymyo, combined with the exhaustion and starvation of the expedition meant that men began to fall ill and ultimately die in the cramped sheds, which were no bigger than the bathing huts found at English seaside resorts. I would estimate that approximately 20 men died at Maymyo, with perhaps another 10 or so losing their fight for life when the Chindits were eventually moved down to Rangoon in late May or early June. I first thought that all 200 or so Chindits were sent by rail to Rangoon in one group, but recent documents have shown that this was not the case. Several journeys were needed to transport them all to the city jail and this took two or three weeks to complete.

Here are some memories of the camp from Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding, this young officer was a member of Wingate's Head Quarters and had been captured after failing to cross the Irrawaddy in late April 1943.

"After some time we were sent to Maymyo, to a sort of 'Hell Camp' where we were supposed to learn Japanese drill. Believe it or not, the Japanese for 'Right turn' is 'Migi Mugi Migi'. Of course it doesn't sound like that any more than an English sergeant bellowing "Right turn" sounds like that, but you will see our difficulty in understanding these commands.

It was here that we met the 'landsturmer' type of Jap. And he is a bad type. (Landsturmer is a German colloquial word for a third class infantryman or soldier).

In the compound there was a 'one holer' (a single latrine). Each morning we had to line up with our chamber pots to empty them therein. In the camp there was an Anglo-Burmese family - father, mother, and two teenaged daughters. One of the girls, scarlet in the face, lined up with the troops, many, if not all, in a desperate hurry. They ALL stood back and said, "After you, Miss." It may seem dotty in the circumstances, but I was very proud of them.

We drew our rice in wooden buckets which we were supposed to wash up and return. In those days I was not the accomplished 'washerupper' that I am today, and I must have missed a grain or two. I gave my bucket to one of the cooks (a Burman), who remonstrated, but I paid no heed.

A bit later the cook and our Jap drill instructor arrived, the cook bearing my bucket. The Jap carried a teak club fashioned in the shape of a samurai sword, very dangerous looking. We were just standing about. The unwritten law was that if you saw trouble coming and knew it was yours, you told your friends and they faded away. There was no point in getting others involved, but it was pretty lonely business.

Up they came and the Jap said something or other. It sounded pretty hostile to me, so I said, "Wakeru nai", which means, I think, "I do not understand". This was always the first (and often the last) line of defence.

The cook, bless him, said, "Hey Johnnie." That was his big mistake. The Jap looked at me and said, "Shoko?", which means,"Officer?" I said "Hai", which means "Yes". He then said to the cook,"Bo-jee"; this is the Burmese for "Officer". The cook indicated that he knew this. Whereupon the Jap gave me a little bow and drove the cook away beating him about the shoulders.

I can only suppose that while he, the Jap, had not the slightest compunction about beating up an Allied Officer, he was hanged if a non-combatant was going to be rude to one. I was a bit relieved because if he had hit me over the head my skull would most certainly have been fractured. I did not wash up again.

After Maymyo we had a perfectly foul journey, in very hot, metal, closed doored railway trucks to Rangoon and were then marched from the station to Rangoon Central Jail in Commissioner Road."

Below is a page from a Kachin Levees intelligence report, the Kachins were a tribe from within Burma who had remained totally loyal to the British throughout and indeed after the war. The report gives some minor details about the location and conditions at Maymyo.

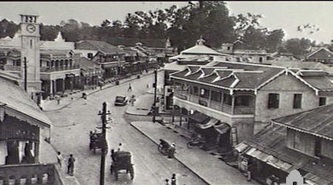

Maymyo was a British garrison town, and had been the summer get away for the military and civilian hierarchy present in Burma for many years. As the extreme heat of the Burmese plains and Irrawaddy delta became too much for these colonials, they simply moved their families up into the fresher and more pleasant air of the hill station.

We visited the town on our tour in 2008 and it was remarkable how different the climate was at Maymyo, even though it was only around 50 miles from Mandalay. The roads leading up to the town are steep with numerous 'hair-pin' bends, these tested both driver and bus alike and we made painfully slow progress at times. Here is a short extract from my Burma Diary describing the scenery around Maymyo:

"As we climbed steadily up the hills toward Maymyo, the air became much fresher and the scenery healthier and greener. We saw roadside food stalls and signs of agricultural crops other than rice. The flora of this region was noticeably richer and more vibrant. All the favourites from our own English gardens were there, pansies, poinsettias, mulberry and dianthus amongst many others. But most magnificent of all was the giant bamboo plants, several meters high, and of the darkest greens, and one yellow example with green piping running through the canes.

We stayed at the Kandawgyi Hill Resort, which was once an old style colonial house. This now has chalet style accommodation in its grounds, and was a very beautiful location indeed. You could very easily see why the British made this place their favourite holiday destination back in the mid 1800’s. Some of their old houses still remain, but sadly have fallen into disrepair and lost their former splendour. The Burmese military have their Army Training Centre up in the hills of Maymyo, we often saw the junior officers walking around, much to the distaste of our guide, but to be fair they were always pleasant and courteous to us all."

As a point of reference I should of mentioned that Maymyo (May's town) is named after the soldier, Major-General James May who founded and designed the town whilst serving in Burma during 1886-7. For more information about Maymyo and some memories of the town during WW2 please click on the link below:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/41/a9029441.shtml

During our trip to Maymyo we stopped off at the railway station and visited the local churches. As I have mentioned before when I was in Burma in 2008 I knew almost nothing about my grandfather and his time there during WW2, so I never realised that when we we all standing in the European Cemetery looking at the graves of soldiers buried there in the 1800's, we were probably as close to a place that Grandad had frequented when he was still alive, than at any other time on the tour. The cemetery was in a poor state of repair and many of the tomb stones had fallen over or simply crumbled away, however, the grounds still held an incredible atmosphere and sense of history.

In the book 'Helen of Burma', the story of nurse Helen Rodriguez and her time in Burma during WW2, she mentions that the British Army POW's were held close to St. Joseph's Convent School. This is located just across the road from the old Garrison Church and the cemetery. The Garrison Church (now Sacred Heart Catholic Church) was used by the Japanese as an officer's club during the years of occupation and some of the British soldiers were used as servants and worked at this club.

It seems logical to me that any soldiers who perished in the Maymyo Camp would be buried in the cemetery just over the road from where they existed as prisoners of war. However, no graves from Maymyo (as far as I can ascertain) were ever exhumed and moved down to Taukkyan or Rangoon War Cemeteries. The men who died at Maymyo are then almost certainly remembered with an inscription on the Rangoon Memorial. I suppose that the bodies of the men who died at Maymyo could have been disposed of in other ways, for instance cremation, but unless diseases such as cholera were present in the camp this seems unlikely.

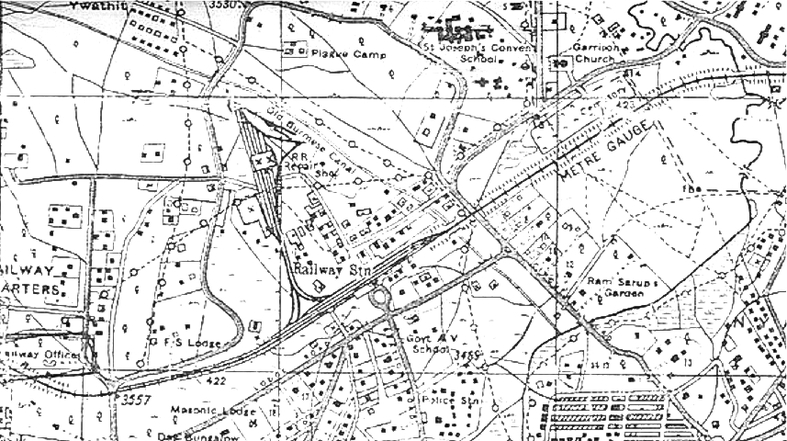

The brilliant website 'Memories of Maymyo' (link seen above) has a good map of the area around the railway station circa 1944, it is shown below and features the European Cemetery, railway line and station, St. Joseph's Convent School and the Garrison Church. Surely this map shows the local area in Maymyo town where the Longcloth Chindits were held.

NB. The European Cemetery is situated just the other side of the railway line in the top right hand corner of the map, above the words METRE GAUGE.

To finish this section about Maymyo and the POW camp situated there, here are some general images showing some of the places mentioned in the above narrative. The modern images are courtesy of Denise McCulloch and Marc Fogden.

Update 11/01/2013. More memories of the Maymyo Camp from Lieutenant Philip Stibbe:

"About 12th May we were told that those of us who were fit were going to go to Maymyo, we were all assembled in the compound and they told us we would march the 201 miles to Lashio and from there go by train to Maymyo. They painted a very pretty picture of Maymyo, there would be a large house for us to live in and we would be paid, there would be bread, cakes and sweets instead of nothing but rice and that we would be allowed to write home. It all sounded too good to be true, and it was.

The beautiful big house turned out to be the wooden building which had been built for the native followers of a British battalion in peace time. There were simple rows of mosquito infested rooms, about the size of a horse box, with a rough wooden veranda running along outside. If we expected better treatment at Maymyo it was not long before we were disappointed. As soon as we arrived at Jap approached Ted Horton and me and, we thought, motioned us to sit down on the ground. We did so, but were at once lifted to our feet again by a couple of swinging blows on the jaw.

The object of the at Maymyo was to teach us the Japanese words of command, to make us respect the Japs and, above all, to train us in discipline. This discipline was enforced by varying degrees of corporal punishment, depending partly on the seriousness of the offence, but chiefly on the mood of the Japs. Ignorance of a rule or failure to understand an order, even when it was in Japanese, was never considered an excuse. The most common offence was forgetting to salute or bow to a sentry or guard. The Japanese looked upon all sentries as direct representatives of the Emperor and had to be treated as such. Anyone failing to bow was treated extremely harshly.

At the beginning and end of every day we all had to attend the Japanese prayer parade, which was held in a nearby field. The Japs would all stand facing a kind of altar and there would be a great deal of shouting and praying and bowing in the direction of Japan. We were just expected to stand there quietly and bow when the Japs bowed.

At night we were locked in our little rooms but they were so crowded that there was hardly space for us to lie down. Nevertheless, we were always thankful to be shut in at night because it did mean that for a few hours we were free on the prying eyes of the Japanese guards. Each day working parties went out into Maymyo. The usual jobs were digging air raid shelters or pulling down bombed houses; those who did not go out were employed in the camp, either digging shelters or weeding the gardens.

We were given three meals a day and the food was well cooked but there was never enough. A few days after we arrived, some more prisoners from our Brigade were brought in. One of them was in a terrible state and died after he had been in the camp for only a few minutes. I was taken with four other men to dig a grave for him in the cemetery opposite the British Church. During our time at Maymyo I think I came nearer to despair than at any other time during my captivity."

"About 12th May we were told that those of us who were fit were going to go to Maymyo, we were all assembled in the compound and they told us we would march the 201 miles to Lashio and from there go by train to Maymyo. They painted a very pretty picture of Maymyo, there would be a large house for us to live in and we would be paid, there would be bread, cakes and sweets instead of nothing but rice and that we would be allowed to write home. It all sounded too good to be true, and it was.

The beautiful big house turned out to be the wooden building which had been built for the native followers of a British battalion in peace time. There were simple rows of mosquito infested rooms, about the size of a horse box, with a rough wooden veranda running along outside. If we expected better treatment at Maymyo it was not long before we were disappointed. As soon as we arrived at Jap approached Ted Horton and me and, we thought, motioned us to sit down on the ground. We did so, but were at once lifted to our feet again by a couple of swinging blows on the jaw.

The object of the at Maymyo was to teach us the Japanese words of command, to make us respect the Japs and, above all, to train us in discipline. This discipline was enforced by varying degrees of corporal punishment, depending partly on the seriousness of the offence, but chiefly on the mood of the Japs. Ignorance of a rule or failure to understand an order, even when it was in Japanese, was never considered an excuse. The most common offence was forgetting to salute or bow to a sentry or guard. The Japanese looked upon all sentries as direct representatives of the Emperor and had to be treated as such. Anyone failing to bow was treated extremely harshly.

At the beginning and end of every day we all had to attend the Japanese prayer parade, which was held in a nearby field. The Japs would all stand facing a kind of altar and there would be a great deal of shouting and praying and bowing in the direction of Japan. We were just expected to stand there quietly and bow when the Japs bowed.

At night we were locked in our little rooms but they were so crowded that there was hardly space for us to lie down. Nevertheless, we were always thankful to be shut in at night because it did mean that for a few hours we were free on the prying eyes of the Japanese guards. Each day working parties went out into Maymyo. The usual jobs were digging air raid shelters or pulling down bombed houses; those who did not go out were employed in the camp, either digging shelters or weeding the gardens.

We were given three meals a day and the food was well cooked but there was never enough. A few days after we arrived, some more prisoners from our Brigade were brought in. One of them was in a terrible state and died after he had been in the camp for only a few minutes. I was taken with four other men to dig a grave for him in the cemetery opposite the British Church. During our time at Maymyo I think I came nearer to despair than at any other time during my captivity."

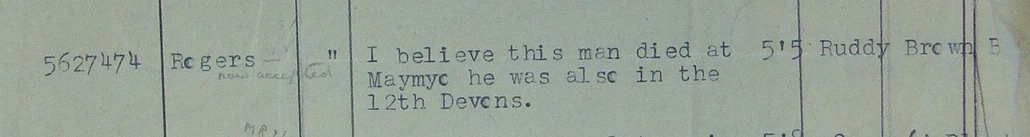

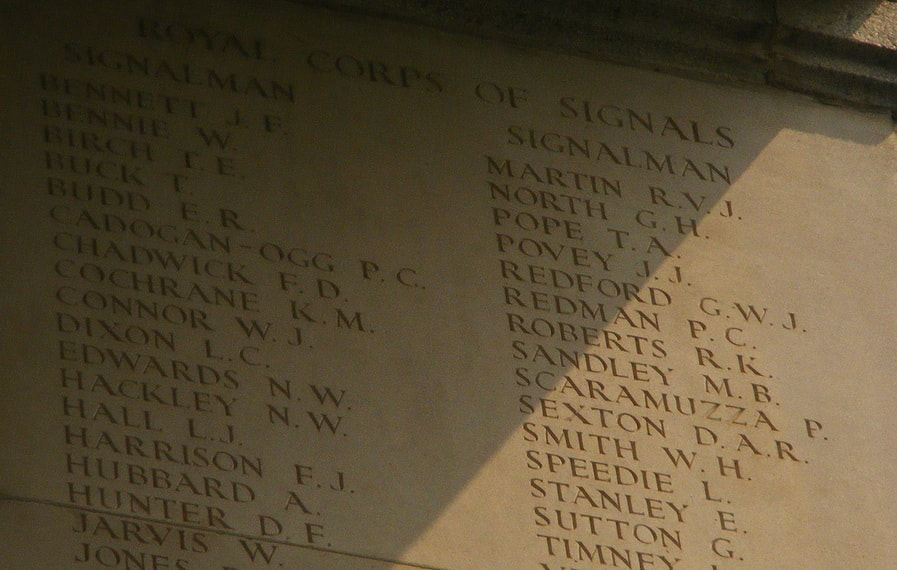

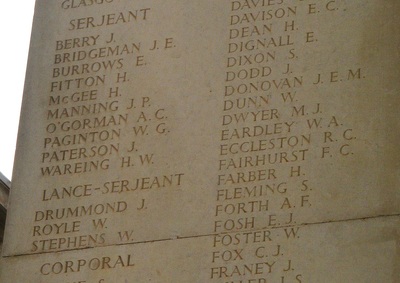

I believe it is possible that the following men all died as prisoners of war in the Maymyo Camp, or if not, perished on the POW's journey down to Rangoon Jail in early June 1943. Books and memoirs tell us that several men certainly died there, but I feel the number is nearer 20, although there is little actual documentary evidence for this claim.

The men listed below are all remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial suggesting that they had no known grave. It seems strange to me that the men stated as being buried at Maymyo did not have their remains exhumed and transported to either Taukkyan or Rangoon War Cemetery for re-burial after the war. Maymyo had a long history as a British Military town, so it was not as if these graves could have been missed when the Imperial War Graves Commission began their long task of locating British casualties and their last known resting places.

Of the 20 men listed below sixteen of them have the registered date of death of 01/06/1943. I believe this was an agreed date decided upon by the 'powers that be', which rounded up all those who perished at Maymyo or camps before that, such as Kalaw and Bhamo, but whose precise details had not been recorded and could not then be remembered. It may also include those who left Maymyo alive, but sadly were never to reach Rangoon Jail. Here is the list of possible Maymyo casualties:

The men listed below are all remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial suggesting that they had no known grave. It seems strange to me that the men stated as being buried at Maymyo did not have their remains exhumed and transported to either Taukkyan or Rangoon War Cemetery for re-burial after the war. Maymyo had a long history as a British Military town, so it was not as if these graves could have been missed when the Imperial War Graves Commission began their long task of locating British casualties and their last known resting places.

Of the 20 men listed below sixteen of them have the registered date of death of 01/06/1943. I believe this was an agreed date decided upon by the 'powers that be', which rounded up all those who perished at Maymyo or camps before that, such as Kalaw and Bhamo, but whose precise details had not been recorded and could not then be remembered. It may also include those who left Maymyo alive, but sadly were never to reach Rangoon Jail. Here is the list of possible Maymyo casualties:

|

Pte. 5119068 Harry Bannister

Pte. 3861126 Albert Barnes Pte. 3607260 Ernest Thomas Belcher Signalman 3717500 Frederick Douglas Chadwick Pte. 5619756 Lawrence Frederick Hill Pte. 3445372 Ernest Holt Signalman 2573618 William Jarvis Pte. 5335617 Peter Edwin 'Rocky' Knight Sapper 1882430 Percy Ronald Lowe Lieut. 73137 James Vernon Crispin Molesworth |

Capt. 91900 Arthur Lotherington Moxham

Signalman 5881821 John James Povey Pte. 5627474 Everard Donald Rogers Pte. 3658229 John Royle W/Cpl. 1871395 Thomas Smith Signalman 2363697 Lawrence Speedie Pte. 5628525 William Thomas Samuel Symons Signalman 2372451 Joseph Timney Pte. 5626116 Frank James Watts Rflm. Karna Bahadur Tamang |

Apart from the witness statement from Fred Morgan in regard to the death of Everard Rogers at Maymyo, the only other information I have come across refers to the death of Lieutenant James Molesworth. James, originally from St. Helier in Jersey, had been attached to the 142 Commando unit on Operation Longcloth, possibly with Column 5. He had dispersed with some Gurkha and Burmese Rifles in late March, but had become separated and was taken prisoner. In a statement made by Lieutenant Ted Horton which forms part of the Chindit Collection of papers held at the Imperial War Museum, Molesworth was said to have died at Maymyo and his body cremated.

To read more about Lieutenant Molesworth, please click on the following link: Lt. James V. C. Molesworth

Update 04/02/2013.

For information about the alleged Japanese experiments performed on POW's, please click on the link here: Japanese Experimentation on POW's

Pte. Albert Barnes.

Pte. Albert Barnes.

Update 21/04/2014.

Pte. Albert Barnes was a member of 142 Commando in 1943 and was attached to Chindit Column 2 under the original command of Major Arthur Emmett. Albert was formerly with the Loyal Regiment, before being posted to the 13th King's in 1942 and undertaking Chindit training.

After the disastrous engagement with the Japanese at the rail station of Kyaikthin, he and a few other men joined up with Column 1 and became part of Major George Dunlop's Commando Platoon. The photograph seen opposite was found in the 'War Illustrated' magazine, and formed part of the periodicals 1939-45 Roll of Honour, alongside the photograph was this simple caption stating:

Pte. A. Barnes, aged 29, King's Liverpool Regiment, died of wounds at Kalewa, June 1943.

This information immediately helps confirm his POW status, as the village of Kalewa was another of the holding camps for captured Chindits in 1943. More details about Albert materialised from the 'missing in action' files for the 13th King's held at the National Archives, where a short report had been submitted by Lieutenant P.W. MacLagan:

Regarding Pte. E. Belcher and Pte. A. Barnes amongst others, who were recorded as missing on the 9th May, 1943 in Burma:

"On the 8th May 1943 at mid-day, the party under Major Dunlop was attacked on the Katun Chaung about 3 miles from the Chindwin River. Major Dunlop led the party up a dry nullah into the surrounding hills. The above mentioned men were in a group led by Lance Corporal McMurran which went on with Major Dunlop."

The report then goes on to recommend that a statement is obtained from Major Dunlop in order to further clarify what happened to these men. In Dunlop's own debrief documents for 1943 he mentions that in the area close to the east banks of the Chindwin there were many Japanese and Burmese fighting patrols, all on the lookout for the Chindits attempting to escape back to India.

It seems highly likely that Albert Barnes was captured shortly after the engagement on the 8th May, as both Ernest Belcher, also formerly of the Loyal Regiment and William George McMurrin are recorded as being prisoners of war. It also seems certain that Albert had been wounded in some way during the attack at the Katun Chaung, where he was only a few short miles from the relative safety of the Chindwin River. According to the dates given on the CWGC website, Albert died sometime between the 1st and 20th June 1943. This matches up with the criteria mentioned previously in this section for men who perished whilst POW's in Japanese hands, but had never made it down to Rangoon Jail.

Albert Barnes is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2504907/BARNES,%20ALBERT

Pte. Albert Barnes was a member of 142 Commando in 1943 and was attached to Chindit Column 2 under the original command of Major Arthur Emmett. Albert was formerly with the Loyal Regiment, before being posted to the 13th King's in 1942 and undertaking Chindit training.

After the disastrous engagement with the Japanese at the rail station of Kyaikthin, he and a few other men joined up with Column 1 and became part of Major George Dunlop's Commando Platoon. The photograph seen opposite was found in the 'War Illustrated' magazine, and formed part of the periodicals 1939-45 Roll of Honour, alongside the photograph was this simple caption stating:

Pte. A. Barnes, aged 29, King's Liverpool Regiment, died of wounds at Kalewa, June 1943.

This information immediately helps confirm his POW status, as the village of Kalewa was another of the holding camps for captured Chindits in 1943. More details about Albert materialised from the 'missing in action' files for the 13th King's held at the National Archives, where a short report had been submitted by Lieutenant P.W. MacLagan:

Regarding Pte. E. Belcher and Pte. A. Barnes amongst others, who were recorded as missing on the 9th May, 1943 in Burma:

"On the 8th May 1943 at mid-day, the party under Major Dunlop was attacked on the Katun Chaung about 3 miles from the Chindwin River. Major Dunlop led the party up a dry nullah into the surrounding hills. The above mentioned men were in a group led by Lance Corporal McMurran which went on with Major Dunlop."

The report then goes on to recommend that a statement is obtained from Major Dunlop in order to further clarify what happened to these men. In Dunlop's own debrief documents for 1943 he mentions that in the area close to the east banks of the Chindwin there were many Japanese and Burmese fighting patrols, all on the lookout for the Chindits attempting to escape back to India.

It seems highly likely that Albert Barnes was captured shortly after the engagement on the 8th May, as both Ernest Belcher, also formerly of the Loyal Regiment and William George McMurrin are recorded as being prisoners of war. It also seems certain that Albert had been wounded in some way during the attack at the Katun Chaung, where he was only a few short miles from the relative safety of the Chindwin River. According to the dates given on the CWGC website, Albert died sometime between the 1st and 20th June 1943. This matches up with the criteria mentioned previously in this section for men who perished whilst POW's in Japanese hands, but had never made it down to Rangoon Jail.

Albert Barnes is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2504907/BARNES,%20ALBERT

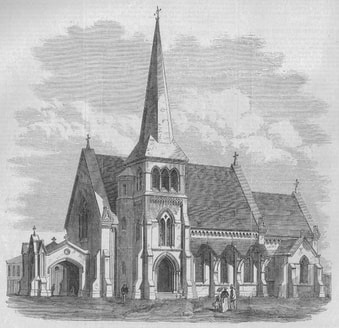

The Cathedral of The Holy Trinity

The Cathedral of the Holy Trinity circa late 1800's.

The Cathedral of the Holy Trinity circa late 1800's.

A visit to the Holy Trinity Cathedral has been included in most of the tours and pilgrimages run by the Royal British Legion ever since it began to include Burma and Rangoon in it's program. In relation to the Chindits and the men who were held captive in Rangoon Jail I am not sure whether any were ever buried in the grounds of the Cathedral. However, since the end of WW2 the Cathedral has been used as the centre for remembrance in regard to British Forces and their service in and around the city.

Holy Trinity is the primary Anglican Cathedral in Burma today and is located оn Bogyoke Aung San Road, close to the old 'Scott's' market. The Cathedral wаs designed by Robert Fellowes Chisholm, construction began іn 1886, wіth the laying оf the foundation stone by Lord Dufferin, the then Viceroy оf India.

Although the foundation stone had been laid in 1886 due to a shortage of funds it took another 9 years to complete the church and it's vestibule. The spire was added in 1913 and the bell tower installed the following year.

During the occupation of Rangoon, the Cathedral was used as a brewery making sake and cooking sauces for the Japanese forces. After liberation, the Cathedral was cleaned up by a volunteer working party which included many British military contributors, all working with picks and shovels and willing to generally 'muck in.' The chapel was dedicated to the 12th and 14th Armies who fought during the Burma Campaign. On the walls of the Forces Chapel there are various regimental plaques depicting the many British and Indian units which took part in the fighting leading up to the liberation of Rangoon.

The Cathedral was heavily associated with the early Anglican movement in Burma in the late 1870's. Then in 1970 Burma formally became a province within the Anglican communion, with its base in Rangoon, at Holy Trinity. In 1977 Holy Trinity was twinned with Winchester Cathedral and is remembered by them at every Evensong.

Holy Trinity is the primary Anglican Cathedral in Burma today and is located оn Bogyoke Aung San Road, close to the old 'Scott's' market. The Cathedral wаs designed by Robert Fellowes Chisholm, construction began іn 1886, wіth the laying оf the foundation stone by Lord Dufferin, the then Viceroy оf India.

Although the foundation stone had been laid in 1886 due to a shortage of funds it took another 9 years to complete the church and it's vestibule. The spire was added in 1913 and the bell tower installed the following year.

During the occupation of Rangoon, the Cathedral was used as a brewery making sake and cooking sauces for the Japanese forces. After liberation, the Cathedral was cleaned up by a volunteer working party which included many British military contributors, all working with picks and shovels and willing to generally 'muck in.' The chapel was dedicated to the 12th and 14th Armies who fought during the Burma Campaign. On the walls of the Forces Chapel there are various regimental plaques depicting the many British and Indian units which took part in the fighting leading up to the liberation of Rangoon.

The Cathedral was heavily associated with the early Anglican movement in Burma in the late 1870's. Then in 1970 Burma formally became a province within the Anglican communion, with its base in Rangoon, at Holy Trinity. In 1977 Holy Trinity was twinned with Winchester Cathedral and is remembered by them at every Evensong.

Cathedral of the Holy Trinity circa March 2008.

Cathedral of the Holy Trinity circa March 2008.

We visited the Cathedral in March 2008, directly after our excursions to the war cemeteries at Taukkyan and Rangoon. Here a service of remembrance was held in honour of all those who had perished during the fighting in World War Two.

The service was conducted by the Reverend Samuel Htang Oak and was also attended by a representative of the British Consul in Rangoon as well as many of the local parishioners. On our tour was the son of another Chindit casualty from 1943, Arthur Lee. His father, George Lee was also in Column 5 just like my grandfather and Arthur had returned to Rangoon for the second time in order to place a new regimental plaque upon the walls of the church chapel. And so it was that the plaque representing the Kings Liverpool Regiment finally took it's place amongst the other illustrious units involved in the Burma Campaign.

Here is what I remembered about the service that evening. Taken from my Burma diary:

"We left Rangoon War Cemetery and headed for the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, where a special service was conducted for our group. It was here that we saw a book of remembrance kept in the Forces Chapel, which had been lovingly drawn up by a lady called Marjorie G. Dyer in 1949. This book had all the names of the fallen, beautifully written in longhand and including Granddad, but also, it had placed Reg Milkins in the correct Regiment as well, which made me feel a lot better.

The ceremony was very touching, but you could tell the anxiety of the day had passed as more and more the pilgrims returned to a normal and more relaxed demeanour. It was for this venue that Arthur Lee had brought the regimental plaque of the King’s Liverpool’s. He had noticed this sad omission on a previous visit to Rangoon and had promised to correct it, and so it was duly done. Amongst the congregation were three older Anglo-Burmese worshipers, they had been present in Rangoon during the war and were a great wealth of information. Denis (Gudgeon) had been speaking with them earlier and they were fascinated by his stories about Rangoon Jail and his time working at the city docks."

NB. Pte. Reginald Milkins a soldier with the 13th Kings in 1943 has been mistakenly remembered on the Rangoon Memorial as serving with the Lancaster Regiment. His name sits rather ironically, just above that of his true Chindit comrades, on Face 5 of the Memorial. Seeing this error at Taukkyan War Cemetery had been a source of great upset for me, so it was reassuring to see him remembered correctly in Marjorie Dyer's book. Later on after returning home from Burma, I was able to provide my good friend Lars Ahlkvist with enough documentary evidence to prove Milkins presence on Operation Longcloth, and in turn to convince the CWGC to amend his details online. This they have done, but we still await the correction upon the Rangoon Memorial itself.

Seen below are some other photos and images in relation to the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity and the Chindit Pilgrimage in 2008. These include the full order of service and the local parish brochure for the month of March that year, a photo of the King's Liverpool Regimental plaque as presented by Arthur Lee and a fascinating aerial view of the Cathedral from 1945. Also shown is a photograph of my grandfather's entry in the book of remembrance, as written by Marjorie Dyer. The chapel room was quite dark and so the quality of this image is somewhat blurred.

The service was conducted by the Reverend Samuel Htang Oak and was also attended by a representative of the British Consul in Rangoon as well as many of the local parishioners. On our tour was the son of another Chindit casualty from 1943, Arthur Lee. His father, George Lee was also in Column 5 just like my grandfather and Arthur had returned to Rangoon for the second time in order to place a new regimental plaque upon the walls of the church chapel. And so it was that the plaque representing the Kings Liverpool Regiment finally took it's place amongst the other illustrious units involved in the Burma Campaign.

Here is what I remembered about the service that evening. Taken from my Burma diary:

"We left Rangoon War Cemetery and headed for the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, where a special service was conducted for our group. It was here that we saw a book of remembrance kept in the Forces Chapel, which had been lovingly drawn up by a lady called Marjorie G. Dyer in 1949. This book had all the names of the fallen, beautifully written in longhand and including Granddad, but also, it had placed Reg Milkins in the correct Regiment as well, which made me feel a lot better.

The ceremony was very touching, but you could tell the anxiety of the day had passed as more and more the pilgrims returned to a normal and more relaxed demeanour. It was for this venue that Arthur Lee had brought the regimental plaque of the King’s Liverpool’s. He had noticed this sad omission on a previous visit to Rangoon and had promised to correct it, and so it was duly done. Amongst the congregation were three older Anglo-Burmese worshipers, they had been present in Rangoon during the war and were a great wealth of information. Denis (Gudgeon) had been speaking with them earlier and they were fascinated by his stories about Rangoon Jail and his time working at the city docks."

NB. Pte. Reginald Milkins a soldier with the 13th Kings in 1943 has been mistakenly remembered on the Rangoon Memorial as serving with the Lancaster Regiment. His name sits rather ironically, just above that of his true Chindit comrades, on Face 5 of the Memorial. Seeing this error at Taukkyan War Cemetery had been a source of great upset for me, so it was reassuring to see him remembered correctly in Marjorie Dyer's book. Later on after returning home from Burma, I was able to provide my good friend Lars Ahlkvist with enough documentary evidence to prove Milkins presence on Operation Longcloth, and in turn to convince the CWGC to amend his details online. This they have done, but we still await the correction upon the Rangoon Memorial itself.

Seen below are some other photos and images in relation to the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity and the Chindit Pilgrimage in 2008. These include the full order of service and the local parish brochure for the month of March that year, a photo of the King's Liverpool Regimental plaque as presented by Arthur Lee and a fascinating aerial view of the Cathedral from 1945. Also shown is a photograph of my grandfather's entry in the book of remembrance, as written by Marjorie Dyer. The chapel room was quite dark and so the quality of this image is somewhat blurred.

St. Mary's Cathedral, Rangoon

St. Mary's Cathedral pre-WW2.

St. Mary's Cathedral pre-WW2.

St. Mary’s Cathedral is situated on Bo Aung Kyaw Street in Botahtaung Township, Yangon. It was designed by Dutch architect Jos Cuypers and is another striking example of the European styled red brick design favoured by architects during the late 1800's.

Construction began in 1895 and was completed in 1899. The interior of the Cathedral is richly decorated with some outstanding period features and renowned throughout Burma for it's exquisite stained glass windows. St. Mary's is the largest Cathedral in Burma today.

Although the earthquake in May 1930 wrought havoc to the city in general, the Cathedral survived relatively unscathed with only two interior vaults collapsing and some other minor cracking to outside walls. Within a few short weeks all the repairs had been completed and the building re-opened for worship once more.

The Cathedral withstood the Japanese bombing during the British Army's retreat from Burma, but the Allied bombing on the 14th December 1944 blew away many of the ornate stain glass windows. These were replaced with ordinary glass from local manufacturers. On 2 May 2008, the Cathedral windows were once again damaged by the Cyclone Nargis.

For more information and some fantastic photos of how the Cathedral looks today, please click on the following link: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Mary%27s_Cathedral,_Yangon

Construction began in 1895 and was completed in 1899. The interior of the Cathedral is richly decorated with some outstanding period features and renowned throughout Burma for it's exquisite stained glass windows. St. Mary's is the largest Cathedral in Burma today.

Although the earthquake in May 1930 wrought havoc to the city in general, the Cathedral survived relatively unscathed with only two interior vaults collapsing and some other minor cracking to outside walls. Within a few short weeks all the repairs had been completed and the building re-opened for worship once more.

The Cathedral withstood the Japanese bombing during the British Army's retreat from Burma, but the Allied bombing on the 14th December 1944 blew away many of the ornate stain glass windows. These were replaced with ordinary glass from local manufacturers. On 2 May 2008, the Cathedral windows were once again damaged by the Cyclone Nargis.

For more information and some fantastic photos of how the Cathedral looks today, please click on the following link: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Mary%27s_Cathedral,_Yangon

A modern day view of St. Mary's

A modern day view of St. Mary's

It was only recently that I became aware of the significance of St. Mary's to the Chindit story in 1943. The information came from the personal diaries of Captain Tommy Roberts, in the form of casualty listings he had drawn up after his capture by the Japanese and his initial incarceration in Rangoon Jail. Roberts had attempted to keep a record of each man taken prisoner that year, which included their place of burial if the soldier had happened to die in Japanese hands.

From his list three burials were recorded as having taken place in the grounds of St. Mary's Cemetery, it must be assumed that he was referring to the cemetery in the Catherdral grounds. The men involved were Francis Fairhurst, Edward Gunn and Fred Lowe. It is my belief that Francis, Edward and Fred all died very soon after reaching Rangoon Jail, possibly within a matter of days and that a decision was made to take them to St. Mary's as the only obvious Christian burial site available at the time. Subsequently after a few weeks had passed, the powers that be decided to use the Old Cantonment Cemetery, which was much nearer to the jail and more convenient for the unfortunately steady steam of Chindit deaths.

As mentioned elsewhere on this website, after the war was over the bodies of the men who had died in Rangoon Jail were removed from the Cantonment Cemetery and re-interred at Rangoon War Cemetery. Both Edward Gunn and Fred Lowe were also re-located to the new war cemetery, but somehow Francis Fairhurst was forgotten. It can only be assumed that after liberation in May 1945 none of the survivors from Rangoon Jail had remembered that Francis had also been buried at St. Mary's and so his body was never moved over to Rangoon War Cemetery.

Francis Fairhurst is remembered on the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery which is located on the outskirts of the city. This memorial contains over 26,000 names and commemorates those who were lost in the Burma Campaign, but who have no known grave. To read Pte. Fairhurst's full story please click on the following link: Family 3, Francis Fairhurst

To complete this story, seen below are the three memorials found in Taukkyan and Rangoon War Cemetery's remembering the Chindit men who were buried at St. Mary's Cathedral. Please click on any image to bring them forward on the page.

From his list three burials were recorded as having taken place in the grounds of St. Mary's Cemetery, it must be assumed that he was referring to the cemetery in the Catherdral grounds. The men involved were Francis Fairhurst, Edward Gunn and Fred Lowe. It is my belief that Francis, Edward and Fred all died very soon after reaching Rangoon Jail, possibly within a matter of days and that a decision was made to take them to St. Mary's as the only obvious Christian burial site available at the time. Subsequently after a few weeks had passed, the powers that be decided to use the Old Cantonment Cemetery, which was much nearer to the jail and more convenient for the unfortunately steady steam of Chindit deaths.

As mentioned elsewhere on this website, after the war was over the bodies of the men who had died in Rangoon Jail were removed from the Cantonment Cemetery and re-interred at Rangoon War Cemetery. Both Edward Gunn and Fred Lowe were also re-located to the new war cemetery, but somehow Francis Fairhurst was forgotten. It can only be assumed that after liberation in May 1945 none of the survivors from Rangoon Jail had remembered that Francis had also been buried at St. Mary's and so his body was never moved over to Rangoon War Cemetery.

Francis Fairhurst is remembered on the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery which is located on the outskirts of the city. This memorial contains over 26,000 names and commemorates those who were lost in the Burma Campaign, but who have no known grave. To read Pte. Fairhurst's full story please click on the following link: Family 3, Francis Fairhurst

To complete this story, seen below are the three memorials found in Taukkyan and Rangoon War Cemetery's remembering the Chindit men who were buried at St. Mary's Cathedral. Please click on any image to bring them forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2013.