Chindits that became Prisoners of War

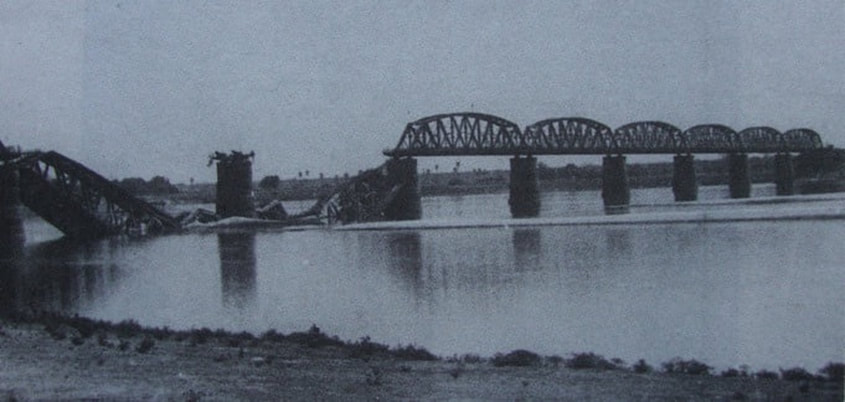

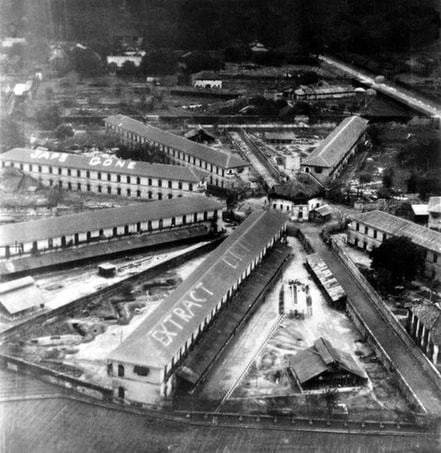

In most of the books and paperwork written about the 1943 Chindits, the figure for the number of bonfide POW's is usually put at around 210. This refers to the men who were known to be captured by the Japanese and who ended up being held at Rangoon Central Jail. (Pictured left, a short time before WW2 began).

During my research I have found perhaps 25 or so more men who were held by the Japanese in 1943, but not all of whom made it down to Rangoon. I would go further and say that it is my belief that many other men were captured alongside jungle paths or in Burmese villages back then. In most cases these men were already in advance stages of starvation, exhaustion or suffering from the multitude of diseases available in Burma at that time. I am sure that these men perished soon after capture and were hastily buried along the way.

My numbers for POW status are 239 confirmed Chindit prisoners of whom roughly 60% did not make it home after liberation in 1945. The lists held at the Imperial War Museum make for grim reading as the soldiers perish in batches of two or three every few days, starting in May 1943 until the deaths finally begin to slow down by early 1944. There is no doubt that, as in the case of my Grandfather, the Longcloth men tended to die more from the privations of the operation, than from anything the Japanese had meted out. Of course the Japanese could have saved them, this is true, with any sensible level of nutrition and medical care, most of the prisoners would have survived. But this was simply not to be.

The men who were destined to be POW's were usually captured alone or in small groups all over the area west and northeast of the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. One group of column 5 men found themselves trapped on a large sandbank in the middle of the Shweli and here around 40 men were taken prisoner in what surely was the single largest group to be rounded up that year. Others had made it all the way back to the eastern banks of the Chindwin River, the natural and unofficial border between Burma and India, only to be captured at this final hurdle.

The story was the same for most of the men. Captured in the field by their opposite number, they were tied and bound, but generally treated decently by the Japanese Imperial infantryman. Most of the men agreed that the further away from the combat zone they travelled the worse their treatment became. After a short while the men were taken to holding camps in the local area. Bhamo camp seems to be the first collection point where a large number of Chindits found themselves crammed together in small wooden pens. Men who might not have seen each other for up to 4 weeks were suddenly reunited in these squalid cell rooms. Here is a quote from Philip Stibbe's book Return via Rangoon when recounting Bhamo Jail.

Bhamo jail consisted of a series of solidly constructed wooden buildings surrounded by a high stone wall. Under the British it had probably been a quite a good jail, as jails go. On our arrival we were searched once again and then put in a large room on the first floor. In this room we found about 60 of our men, most of them were from column 5 and had failed to cross the Shweli River.

Conditions in this room were appalling; to begin with we were terribly overcrowded and sanitary arrangements were revoltingly conspicuous by their absence. The Japs would not allow us out of the room for any reason whatsoever and in consequence we had to relieve nature in buckets in a corner of the room.

During my research I have found perhaps 25 or so more men who were held by the Japanese in 1943, but not all of whom made it down to Rangoon. I would go further and say that it is my belief that many other men were captured alongside jungle paths or in Burmese villages back then. In most cases these men were already in advance stages of starvation, exhaustion or suffering from the multitude of diseases available in Burma at that time. I am sure that these men perished soon after capture and were hastily buried along the way.

My numbers for POW status are 239 confirmed Chindit prisoners of whom roughly 60% did not make it home after liberation in 1945. The lists held at the Imperial War Museum make for grim reading as the soldiers perish in batches of two or three every few days, starting in May 1943 until the deaths finally begin to slow down by early 1944. There is no doubt that, as in the case of my Grandfather, the Longcloth men tended to die more from the privations of the operation, than from anything the Japanese had meted out. Of course the Japanese could have saved them, this is true, with any sensible level of nutrition and medical care, most of the prisoners would have survived. But this was simply not to be.

The men who were destined to be POW's were usually captured alone or in small groups all over the area west and northeast of the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. One group of column 5 men found themselves trapped on a large sandbank in the middle of the Shweli and here around 40 men were taken prisoner in what surely was the single largest group to be rounded up that year. Others had made it all the way back to the eastern banks of the Chindwin River, the natural and unofficial border between Burma and India, only to be captured at this final hurdle.

The story was the same for most of the men. Captured in the field by their opposite number, they were tied and bound, but generally treated decently by the Japanese Imperial infantryman. Most of the men agreed that the further away from the combat zone they travelled the worse their treatment became. After a short while the men were taken to holding camps in the local area. Bhamo camp seems to be the first collection point where a large number of Chindits found themselves crammed together in small wooden pens. Men who might not have seen each other for up to 4 weeks were suddenly reunited in these squalid cell rooms. Here is a quote from Philip Stibbe's book Return via Rangoon when recounting Bhamo Jail.

Bhamo jail consisted of a series of solidly constructed wooden buildings surrounded by a high stone wall. Under the British it had probably been a quite a good jail, as jails go. On our arrival we were searched once again and then put in a large room on the first floor. In this room we found about 60 of our men, most of them were from column 5 and had failed to cross the Shweli River.

Conditions in this room were appalling; to begin with we were terribly overcrowded and sanitary arrangements were revoltingly conspicuous by their absence. The Japs would not allow us out of the room for any reason whatsoever and in consequence we had to relieve nature in buckets in a corner of the room.

As more and more of the men were rounded up the Japanese decide to move the captured Chindits to a larger camp in the hill station town of Maymyo. It was here that things really began to turn sour for the prisoners. Treatment at Maymyo Camp was severe and the guards also insisted on the POW's learning all commands and drills in the Japanese language. Failure to comply with these orders would often result in a beating and it was in Maymyo that the first Chindit POW deaths began to occur.

Another rigid expectation put upon the exhausted soldiers was the Japanese insistence on them joining in in Shinto worship. Once again from the pages of Return via Rangoon.

At the beginning and end of every day we had to attend the Japanese prayer parade, which was held in a nearby field. The Japs would stand facing a kind of altar and there would be a great deal of shouting and praying and bowing in the direction of Japan. We used to call it "toots" parade because at one stage of the ceremony they all said some responses and every response ended with the word "toots". Of course we had no idea what it was all about.

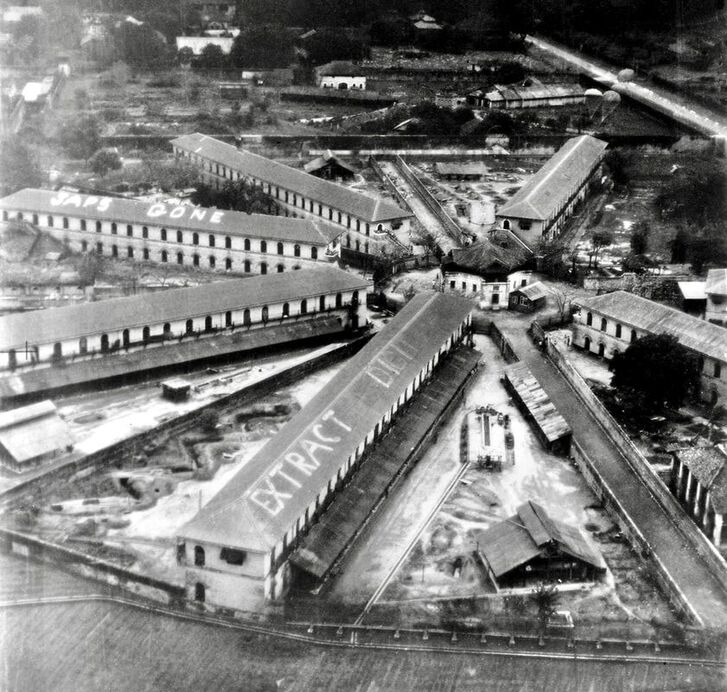

Pictured left, is probably the most well known image of Rangoon Jail with the famous lettering painted on the roofs of some of the blocks. This was done to warn the Allied bombers that the jail contained POW's, the warning did not always work.

The time eventually came to move the prisoners down to Rangoon Central Jail. The men were transported in cattle trucks on the single gauge railway from Maymyo to Mandalay. Conditions were once again appallingly cramped as the train reached the Ava Bridge just outside of Mandalay. There was a problem, the bridge had recently been visited by the RAF and two large central spans were laying twisted in the river. The men had to be detrained on one side of the river and transported across to the other side by ferryboats. Loaded back onto another train on the other side they completed the long journey to Rangoon.

Below is an image of the Ava Bridge as seen after the visit from the RAF.

Another rigid expectation put upon the exhausted soldiers was the Japanese insistence on them joining in in Shinto worship. Once again from the pages of Return via Rangoon.

At the beginning and end of every day we had to attend the Japanese prayer parade, which was held in a nearby field. The Japs would stand facing a kind of altar and there would be a great deal of shouting and praying and bowing in the direction of Japan. We used to call it "toots" parade because at one stage of the ceremony they all said some responses and every response ended with the word "toots". Of course we had no idea what it was all about.

Pictured left, is probably the most well known image of Rangoon Jail with the famous lettering painted on the roofs of some of the blocks. This was done to warn the Allied bombers that the jail contained POW's, the warning did not always work.

The time eventually came to move the prisoners down to Rangoon Central Jail. The men were transported in cattle trucks on the single gauge railway from Maymyo to Mandalay. Conditions were once again appallingly cramped as the train reached the Ava Bridge just outside of Mandalay. There was a problem, the bridge had recently been visited by the RAF and two large central spans were laying twisted in the river. The men had to be detrained on one side of the river and transported across to the other side by ferryboats. Loaded back onto another train on the other side they completed the long journey to Rangoon.

Below is an image of the Ava Bridge as seen after the visit from the RAF.

The men finally arrived in the Burmese capital in very late May or early June that year. Marching from the train station through the bomb damaged streets of Rangoon they must have been an extraordinary sight for the local population. Eventually they found themselves outside the main gates (left) of the infamous Central Jail and caught their first glimpse of the establishment that, if they were lucky, was to be their home for the next two years.

For a description of the POW experience inside Rangoon Jail in 1943 I will leave you in the capable hands of Lieutenant Alec Gibson, formerly of Column 3 on Operation Longcloth. This is his personal account of his time as a Chindit POW, which he kindly sent to me after we had made contact through a mutual friend. Thank you Alec and thank you Tom.

A Guest of the Emperor

Alec Gibson was one of three young 8th Gurkha Rifles officers who, in January 1943 were sent to join Wingate’s first Chindit operation just days before it ventured into Burma. He found himself a member of 3 Column consisting mainly of Gurkha troops and commanded by the famous Mike Calvert. What follows is his own account of his time in captivity and his memories of Rangoon Jail.

Alec told me that he was captured near a village called Taugaung situated on the Eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River. He was taken to the railway town of Wuntho, from where he was transported to the transitory POW camp at Maymyo.

Here is his story….

“Missing from April 4th-last seen swimming the Irrawaddy.” That was the news given to my parents in July 1943 by Lt. McKenzie of the 3/2nd Gurkha Rifles, who had managed to return to India from the first Chindit operation. My parents had no further news of me until I was reported “recovered from the enemy on April 30th 1945."

Following Wingate’s dispersal order we were trapped on the East side of the Irrawaddy, my party was unable to find boats, so swimming was the only alternative. After two abortive attempts I found myself alone with one Gurkha when we were jumped by eight Burmese Independent Army soldiers who tied us up and dragged us to the nearest Jap outpost some 5 miles away.

When initially interrogated by a Japanese Captain who spoke little English, I refused to answer and had a sword stuck at my throat! I thought that was to be my end, but managed to survive the ordeal with very evasive or completely inaccurate answers. Later I was taken by train, with many other prisoners, to Maymyo near Mandalay. Our hands were tied and 26 men were crammed into a railway wagon meant to accommodate only four cattle. At the Maymyo camp we had to learn Japanese drill: commands were shouted to us in Japanese and we were expected to understand them. If we got the drill wrong then we were knocked down with rifle butts, pick handles or bamboo canes. We managed to learn it in about two days!! I was again interrogated and beaten if my answers were unsatisfactory. Both officers and men were up at dawn and made to work on various jobs till dusk. We all had to go and collect our food, two meals a day of rice and vegetable stew.

As a deliberate policy of humiliation we were lined up at least once per day and subjected to considerable face slapping by the Jap guards. Every now and again a prisoner would be called out for interrogation and you knew that you would undergo considerable punishment before you got back again. At night and during air-raids we were locked up, four to a wooden hut about the size of a bathing hut back home. There was a small oil drum inside to use as a latrine, this had to be emptied by one of the four each morning.

At this camp I met one of the Gurkha Subadars wearing the armband with the Jap Rising Sun the sign of the Indian National Army. I asked him how he could do this and he replied “Don’t worry Sahib- I have plans to get out of here.” I heard later that after training with the Japs he and the rest of the Gurkhas were given arms and sent to the front, here they promptly killed the Japs with them and went straight across to the Allied troops.

After several weeks at Maymyo we were transported by train to Rangoon, once again tied up and in cattle trucks. On arrival we were marched to what was previously Rangoon Central Jail, and placed into the solitary confinement block. These cells were about 9 Feet Square with one small window, dark and gloomy, with only the stone floor to sleep on. We were given one blanket each. The guards patrolled the block and we were not supposed to talk to each other, any breach being punished by a beating. Food was brought to us in the morning and evening by one of the British POW’s in the jail. We were only taken out for interrogation. By this time we had all agreed to give up various pieces of misleading information, this we hoped would save us from further torture and punishment. The difficulty was remembering what one had said previously and I nearly got caught out on two occasions. I was in solitary for only a few weeks but some prisoners spent months there.

Then the day came when I was transferred to one of the open blocks. Rangoon Jail, built during colonial times, resembled a large wheel with a well and water tower as the hub and the main blocks radiating out from there like the spokes of a wheel. The blocks were contained in compounds made of seven-foot high brick walls and high iron barred fences at the centre and outer perimeter. The guards patrolling the centre and the hub could see the whole compound. Whenever a guard appeared the nearest person had to call the whole group to attention and all had to bow to the guard. Failure to do so incurred an immediate beating. The blocks were two – storied buildings, each floor containing five rooms with long barred windows down to floor level on one side, and floor to ceiling bars on the whole of the other side, which opened onto a corridor running the length of the block. Stone steps at both ends of the block led to the upper corridor.

In the compound was a long concrete trough containing water and a basha containing lots of ammunition boxes used as latrines. These had to be emptied every day by the Sanitary Squad. Apart from the solitary confinement block and the punishment block, two of the other blocks were occupied by British and American prisoners, two more by Indians, one by Chinese and one by American Airmen in long-term solitary confinement.

In number 3 block where I spent most of my time, the officers were in two rooms on the upper floor, about 26 of us in each room. The other ranks occupied the other rooms with between 30 and 40 POW’s in each. There was no glass in any windows so the Monsoon rains just pored in, but at least this did cool things down. We all had to sleep on the floor with just our blanket and using what you could as a pillow. The Japanese had taken all we possessed; leaving us with the tattered clothes we stood up in. No more clothing was issued; we had to patch whatever we had with materials stolen while out on working parties. Most of the time we wore only a fandoshi or loincloth made from a rectangle of cloth and a piece of string. As our boots fell apart we went barefoot, our feet soon got pretty tough.

For a description of the POW experience inside Rangoon Jail in 1943 I will leave you in the capable hands of Lieutenant Alec Gibson, formerly of Column 3 on Operation Longcloth. This is his personal account of his time as a Chindit POW, which he kindly sent to me after we had made contact through a mutual friend. Thank you Alec and thank you Tom.

A Guest of the Emperor

Alec Gibson was one of three young 8th Gurkha Rifles officers who, in January 1943 were sent to join Wingate’s first Chindit operation just days before it ventured into Burma. He found himself a member of 3 Column consisting mainly of Gurkha troops and commanded by the famous Mike Calvert. What follows is his own account of his time in captivity and his memories of Rangoon Jail.

Alec told me that he was captured near a village called Taugaung situated on the Eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River. He was taken to the railway town of Wuntho, from where he was transported to the transitory POW camp at Maymyo.

Here is his story….

“Missing from April 4th-last seen swimming the Irrawaddy.” That was the news given to my parents in July 1943 by Lt. McKenzie of the 3/2nd Gurkha Rifles, who had managed to return to India from the first Chindit operation. My parents had no further news of me until I was reported “recovered from the enemy on April 30th 1945."

Following Wingate’s dispersal order we were trapped on the East side of the Irrawaddy, my party was unable to find boats, so swimming was the only alternative. After two abortive attempts I found myself alone with one Gurkha when we were jumped by eight Burmese Independent Army soldiers who tied us up and dragged us to the nearest Jap outpost some 5 miles away.

When initially interrogated by a Japanese Captain who spoke little English, I refused to answer and had a sword stuck at my throat! I thought that was to be my end, but managed to survive the ordeal with very evasive or completely inaccurate answers. Later I was taken by train, with many other prisoners, to Maymyo near Mandalay. Our hands were tied and 26 men were crammed into a railway wagon meant to accommodate only four cattle. At the Maymyo camp we had to learn Japanese drill: commands were shouted to us in Japanese and we were expected to understand them. If we got the drill wrong then we were knocked down with rifle butts, pick handles or bamboo canes. We managed to learn it in about two days!! I was again interrogated and beaten if my answers were unsatisfactory. Both officers and men were up at dawn and made to work on various jobs till dusk. We all had to go and collect our food, two meals a day of rice and vegetable stew.

As a deliberate policy of humiliation we were lined up at least once per day and subjected to considerable face slapping by the Jap guards. Every now and again a prisoner would be called out for interrogation and you knew that you would undergo considerable punishment before you got back again. At night and during air-raids we were locked up, four to a wooden hut about the size of a bathing hut back home. There was a small oil drum inside to use as a latrine, this had to be emptied by one of the four each morning.

At this camp I met one of the Gurkha Subadars wearing the armband with the Jap Rising Sun the sign of the Indian National Army. I asked him how he could do this and he replied “Don’t worry Sahib- I have plans to get out of here.” I heard later that after training with the Japs he and the rest of the Gurkhas were given arms and sent to the front, here they promptly killed the Japs with them and went straight across to the Allied troops.

After several weeks at Maymyo we were transported by train to Rangoon, once again tied up and in cattle trucks. On arrival we were marched to what was previously Rangoon Central Jail, and placed into the solitary confinement block. These cells were about 9 Feet Square with one small window, dark and gloomy, with only the stone floor to sleep on. We were given one blanket each. The guards patrolled the block and we were not supposed to talk to each other, any breach being punished by a beating. Food was brought to us in the morning and evening by one of the British POW’s in the jail. We were only taken out for interrogation. By this time we had all agreed to give up various pieces of misleading information, this we hoped would save us from further torture and punishment. The difficulty was remembering what one had said previously and I nearly got caught out on two occasions. I was in solitary for only a few weeks but some prisoners spent months there.

Then the day came when I was transferred to one of the open blocks. Rangoon Jail, built during colonial times, resembled a large wheel with a well and water tower as the hub and the main blocks radiating out from there like the spokes of a wheel. The blocks were contained in compounds made of seven-foot high brick walls and high iron barred fences at the centre and outer perimeter. The guards patrolling the centre and the hub could see the whole compound. Whenever a guard appeared the nearest person had to call the whole group to attention and all had to bow to the guard. Failure to do so incurred an immediate beating. The blocks were two – storied buildings, each floor containing five rooms with long barred windows down to floor level on one side, and floor to ceiling bars on the whole of the other side, which opened onto a corridor running the length of the block. Stone steps at both ends of the block led to the upper corridor.

In the compound was a long concrete trough containing water and a basha containing lots of ammunition boxes used as latrines. These had to be emptied every day by the Sanitary Squad. Apart from the solitary confinement block and the punishment block, two of the other blocks were occupied by British and American prisoners, two more by Indians, one by Chinese and one by American Airmen in long-term solitary confinement.

In number 3 block where I spent most of my time, the officers were in two rooms on the upper floor, about 26 of us in each room. The other ranks occupied the other rooms with between 30 and 40 POW’s in each. There was no glass in any windows so the Monsoon rains just pored in, but at least this did cool things down. We all had to sleep on the floor with just our blanket and using what you could as a pillow. The Japanese had taken all we possessed; leaving us with the tattered clothes we stood up in. No more clothing was issued; we had to patch whatever we had with materials stolen while out on working parties. Most of the time we wore only a fandoshi or loincloth made from a rectangle of cloth and a piece of string. As our boots fell apart we went barefoot, our feet soon got pretty tough.

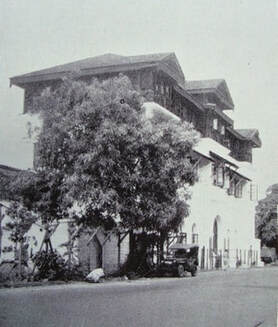

Pictured right is one of the corridors in Rangoon Jail (possibly Block 5, ground floor), this photograph I would imagine was taken well after 1945, note the bicycle outside one of the cell doors. (Picture from Pegasus Archive website)

Alec contiues....

Things settled down into a regular routine, up at dawn for roll call, numbering in Japanese, a brief cup of tea (so called), then detailed off for working parties as notified from the previous day. Every fit person including officers had to work. Working parties consisted of one officer in charge, 15 to 20 men and two or three Jap guards; there were sometimes work parties made up entirely of officers. We marched out of the jail taking with us rice and vegetables for our midday meal, plus all the tools needed for the job we were on. One man would cook the meal while the rest of us were employed as slave labour.

We worked on the railway, unloaded rice and stores at the docks, helped to build an underground headquarters for the Japs, repaired roads and bridges, dug up unexploded bombs and cleared up after air-raid damage. Sometimes we had to work further away such as Mingladon airfield. On these days we were transported in trucks. If anything went wrong, the man concerned and the officer in charge were both beaten up. At dusk we returned to the jail where our cooks would have a meal ready for us. Then after another roll call we were shut up for the night, there were no lights in the blocks.

On Sundays we were usually allowed a rest day, when there were no outside working parties. Sometimes we played football or netball, always being careful not to injure ourselves. On the odd occasion we were allowed to have a concert party, at which I used to sing some of the popular songs, accompanied by a band consisting of one mouthorgan, two men on paper combs and another emulating a trumpet. The Japs used to come along to watch as well. We had no cigarettes but used to make some from Burmese cheroots, rolled in newspaper and stuck down with rice. No Red Cross parcels were ever received and only twice did we get any mail, most of us had never been notified as POW’s anyway. No attempts to escape were made, although it would have been easy enough to get away. Apart from being unfit for such efforts; the chances of travelling hundreds of miles trying to look Indian or Burmese were pretty slim.

For those not fit enough to work outside there were inside working parties for sanitary duties, sick bay orderlies, gardening parties to grow vegetables, cleaning the cell blocks and collecting and delivering food and firewood. All this was interspersed with the need to stop and come to attention and bow every time a guard came near. Some men were permanently on cooking duties and did their best with the rations we were given. This was basically rice and vegetables with occasional meat scrounged from outside, or maybe a pigeon caught on the inside! Sometimes we had a sort of porridge made from ground up husks of rice. It tasted horrible but contained vitamin B1 and was a great help against beriberi. We also had tea, or rather hot water with a few leaves thrown in, no milk and no sugar.

The odd thing about working parties was that the men were paid, albeit only 10 cents (about two pence) per day. Officers were paid a salary once a month, for my rank this amounted to 160 rupees about £12. However deductions were made for board and lodging, contribution to Japanese Defence Bonds and various other items. I actually signed for and received 10 rupees each month, half of which went to fund extra food for sick bay.

We were able to buy small quantities of sugar, eggs, sometimes meat, and Burmese cheroots through the Jap Quartermaster. These items became scarcer and more expensive as time went by. On outside work parties we had become accomplished thieves and stole anything we could lay our hands on. In spite of a search at the guard room when we returned, we used to smuggle in meat, eggs, dried fish, sugar, books and English language newspapers. Sometimes we were caught and severely punished, often beaten or made to stand to attention in the hot sun for hours, but it was worth it.

Alec contiues....

Things settled down into a regular routine, up at dawn for roll call, numbering in Japanese, a brief cup of tea (so called), then detailed off for working parties as notified from the previous day. Every fit person including officers had to work. Working parties consisted of one officer in charge, 15 to 20 men and two or three Jap guards; there were sometimes work parties made up entirely of officers. We marched out of the jail taking with us rice and vegetables for our midday meal, plus all the tools needed for the job we were on. One man would cook the meal while the rest of us were employed as slave labour.

We worked on the railway, unloaded rice and stores at the docks, helped to build an underground headquarters for the Japs, repaired roads and bridges, dug up unexploded bombs and cleared up after air-raid damage. Sometimes we had to work further away such as Mingladon airfield. On these days we were transported in trucks. If anything went wrong, the man concerned and the officer in charge were both beaten up. At dusk we returned to the jail where our cooks would have a meal ready for us. Then after another roll call we were shut up for the night, there were no lights in the blocks.

On Sundays we were usually allowed a rest day, when there were no outside working parties. Sometimes we played football or netball, always being careful not to injure ourselves. On the odd occasion we were allowed to have a concert party, at which I used to sing some of the popular songs, accompanied by a band consisting of one mouthorgan, two men on paper combs and another emulating a trumpet. The Japs used to come along to watch as well. We had no cigarettes but used to make some from Burmese cheroots, rolled in newspaper and stuck down with rice. No Red Cross parcels were ever received and only twice did we get any mail, most of us had never been notified as POW’s anyway. No attempts to escape were made, although it would have been easy enough to get away. Apart from being unfit for such efforts; the chances of travelling hundreds of miles trying to look Indian or Burmese were pretty slim.

For those not fit enough to work outside there were inside working parties for sanitary duties, sick bay orderlies, gardening parties to grow vegetables, cleaning the cell blocks and collecting and delivering food and firewood. All this was interspersed with the need to stop and come to attention and bow every time a guard came near. Some men were permanently on cooking duties and did their best with the rations we were given. This was basically rice and vegetables with occasional meat scrounged from outside, or maybe a pigeon caught on the inside! Sometimes we had a sort of porridge made from ground up husks of rice. It tasted horrible but contained vitamin B1 and was a great help against beriberi. We also had tea, or rather hot water with a few leaves thrown in, no milk and no sugar.

The odd thing about working parties was that the men were paid, albeit only 10 cents (about two pence) per day. Officers were paid a salary once a month, for my rank this amounted to 160 rupees about £12. However deductions were made for board and lodging, contribution to Japanese Defence Bonds and various other items. I actually signed for and received 10 rupees each month, half of which went to fund extra food for sick bay.

We were able to buy small quantities of sugar, eggs, sometimes meat, and Burmese cheroots through the Jap Quartermaster. These items became scarcer and more expensive as time went by. On outside work parties we had become accomplished thieves and stole anything we could lay our hands on. In spite of a search at the guard room when we returned, we used to smuggle in meat, eggs, dried fish, sugar, books and English language newspapers. Sometimes we were caught and severely punished, often beaten or made to stand to attention in the hot sun for hours, but it was worth it.

Pictured here is a typical coupon, the like of which the POW's of Rangoon Jail may have been issued with as part of their paltry food rations.

Alec Gibson continues.......

The things which kept us going were the conviction that we would win the war, a great sense of humour and a determination to outwit the Jap at every opportunity. The last was a particularly difficult path to tread. Any deliberate wrong doing incurred immediate and severe punishment, so everything had to look like an accident or show the British as being incompetent idiots.

The following stories indicate some of the plots in which I was involved, each needing careful coordination between officer and the men. We were unloading rice from barges at Rangoon Docks, carrying it in large jute sacks. Holes were made in the bottom of these sacks so that as we staggered to the warehouse we left a trail of rice along the dockside. Before the Japs could intervene I complained to them that all the sacks were no good. When unloading 40 gallon drums of petrol we made sure that each drum was dumped heavily on to one of the sharp stones we had placed on the dockside-the whole place reeked of fuel. On another occasion a crate of vital fuses for the Japanese shells fell overboard form the ship in spite of our valiant efforts to save it. All successful attempts were of course a great boost to morale.

The one thing that really worried us was being injured or becoming ill as medical treatment was non-existent. We had several medical Officers with us as prisoners but they had virtually nothing in the way of medicines or equipment. Jungle sores or ulcers were treated with copper sulphate crystals, dysentery with charcoal tablets, and beriberi with grain husks. Incredibly, two successful amputations were carried out with the crudest of instruments and no anaesthetics. Most of us suffered from ulcers, dysentery, beriberi, or dengue fever at sometime, but if became serious it was usually terminal. Two thirds of the complement of the camp died, and of the 210 captured Chindits from both expeditions 168 died of their wounds, diseases or malnutrition. Fourteen POW’s died when a Stick of bombs from a crippled American bomber fell right across the jail.

One point I must mention is that, whilst we were treated as dirt as POW’s, the Japanese respected our dead. When a prisoner died he was taken to a burial ground outside the jail by a funeral party consisting of, a British Officer, six other ranks and two guards. His body was carried on small hand cart covered in a very tattered Union Jack. We dug a grave, buried the man, held a brief funeral service and put up a wooden cross. The position of each grave was plotted on a map by our senior officer. Once I was scheduled to take out a funeral party for one man on the following day, by the time I went there were five bodies to be buried. That burial ground is now an official War Cemetery (Rangoon War Cemetery), beautifully laid out, and on the Far East Pilgrimage 40 years later I was able to assure some of the War widows that at least their husbands had been given a proper burial.

Eventually in April 1945 the Japs decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 of us were classified as fit to march and on the 24th of April we marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and crippled. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, we were North of Pegu and nearing the Sittang Bridge when we ran into the 14th Army. The Jap Commandant left us in a village told us we were free and disappeared with the rest of the guards. We were in no-mans land with firing coming from all sides. That night we managed to contact our own troops, the West Yorkshire's, and were released.

Alec Gibson continues.......

The things which kept us going were the conviction that we would win the war, a great sense of humour and a determination to outwit the Jap at every opportunity. The last was a particularly difficult path to tread. Any deliberate wrong doing incurred immediate and severe punishment, so everything had to look like an accident or show the British as being incompetent idiots.

The following stories indicate some of the plots in which I was involved, each needing careful coordination between officer and the men. We were unloading rice from barges at Rangoon Docks, carrying it in large jute sacks. Holes were made in the bottom of these sacks so that as we staggered to the warehouse we left a trail of rice along the dockside. Before the Japs could intervene I complained to them that all the sacks were no good. When unloading 40 gallon drums of petrol we made sure that each drum was dumped heavily on to one of the sharp stones we had placed on the dockside-the whole place reeked of fuel. On another occasion a crate of vital fuses for the Japanese shells fell overboard form the ship in spite of our valiant efforts to save it. All successful attempts were of course a great boost to morale.

The one thing that really worried us was being injured or becoming ill as medical treatment was non-existent. We had several medical Officers with us as prisoners but they had virtually nothing in the way of medicines or equipment. Jungle sores or ulcers were treated with copper sulphate crystals, dysentery with charcoal tablets, and beriberi with grain husks. Incredibly, two successful amputations were carried out with the crudest of instruments and no anaesthetics. Most of us suffered from ulcers, dysentery, beriberi, or dengue fever at sometime, but if became serious it was usually terminal. Two thirds of the complement of the camp died, and of the 210 captured Chindits from both expeditions 168 died of their wounds, diseases or malnutrition. Fourteen POW’s died when a Stick of bombs from a crippled American bomber fell right across the jail.

One point I must mention is that, whilst we were treated as dirt as POW’s, the Japanese respected our dead. When a prisoner died he was taken to a burial ground outside the jail by a funeral party consisting of, a British Officer, six other ranks and two guards. His body was carried on small hand cart covered in a very tattered Union Jack. We dug a grave, buried the man, held a brief funeral service and put up a wooden cross. The position of each grave was plotted on a map by our senior officer. Once I was scheduled to take out a funeral party for one man on the following day, by the time I went there were five bodies to be buried. That burial ground is now an official War Cemetery (Rangoon War Cemetery), beautifully laid out, and on the Far East Pilgrimage 40 years later I was able to assure some of the War widows that at least their husbands had been given a proper burial.

Eventually in April 1945 the Japs decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 of us were classified as fit to march and on the 24th of April we marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and crippled. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, we were North of Pegu and nearing the Sittang Bridge when we ran into the 14th Army. The Jap Commandant left us in a village told us we were free and disappeared with the rest of the guards. We were in no-mans land with firing coming from all sides. That night we managed to contact our own troops, the West Yorkshire's, and were released.

The photograph to the left is of a cell room in Rangoon Jail, it is an upstairs room judging by the visible floorboards. In rooms such as these there might have been as many as 20-25 men.

The windows to the front have only bars between the room and the outside elements, this not only allowed in the monsoon rains, but more disastrously the dreaded mosquito. (Photo from the Pegasus Archive website).

Pictured right are the liberated prisoners from Rangoon Jail receiving new clothes and kit just outside Pegu. These were the so-called fit POW's chosen by the Japanese guards to be marched out toward Siam in April 1945.

The Japanese eventually left them in a village named Waw and it was from here that the men carefully made their way toward the oncoming Allied forces.

Some of the POW's had been issued and were dressed in Japanese uniform and were extremely concerned that from a distance they would be mistaken for the enemy by the advancing 14th Army. (Photograph from the book, Return via Rangoon).

The men were right to fear so-called 'friendly fire', as back at the jail and throughout the final 6 months of their imprisonment Allied bombing raids were drawing closer and closer. The dockyards and railway sidings were perilously close to the jail and sadly it wasn't long before disaster struck and the jail was hit. (Photograph of bomb strikes over Rangoon Jail. Source NARA, USA).

The men who were not fit enough to be chosen for the Pegu march were finally liberated from the jail in early May 1945. They were eventually taken down to the Rangoon docks and put aboard the HMHS Karapara.

The hospitalship pulled away from Rangoon and headed back across the Bay of Bengal to the Indian mainland, disembarking at Calcutta. (Pictured here are the POW's leaving the ship in Calcutta).

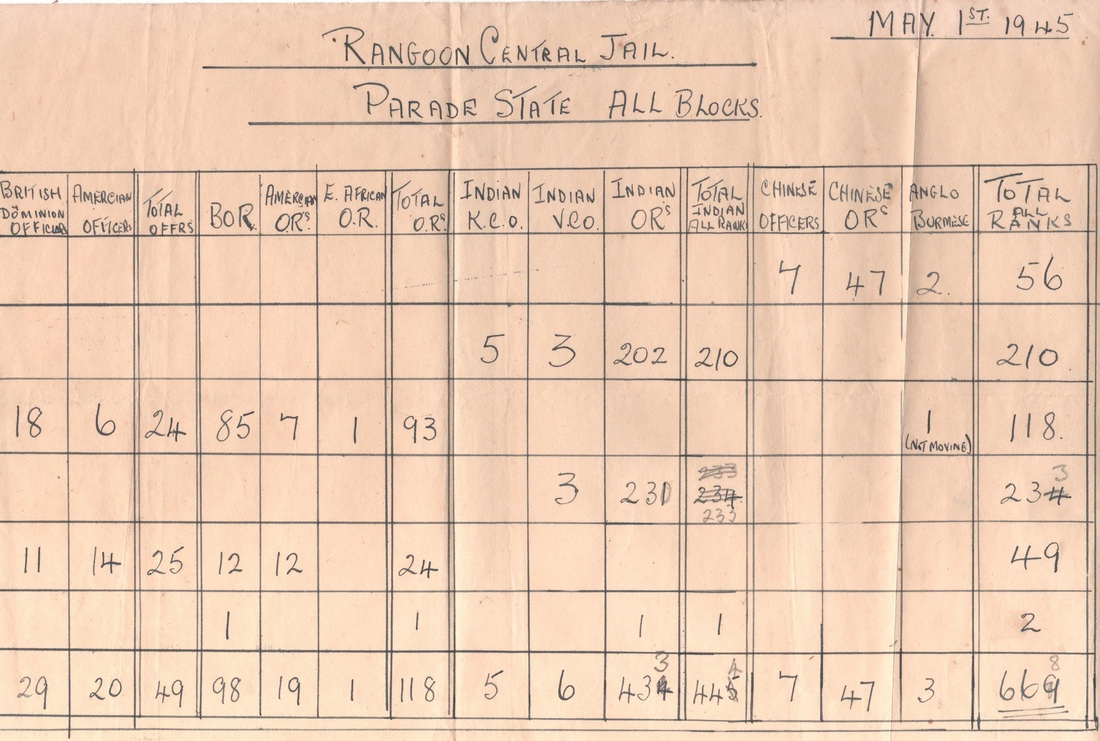

Seen below are the final numbers of prisoners still left in the jail as of May 1st 1945. The listing was collated by the senior officers still present within the prison at that time, these included John Murray Kerr, Tim Finnerty and Lionel Hudson.

The roll shows all the varying nationalities present in Rangoon Jail on that date, but obviously does not include the 400 men who marched out just a few days before and were liberated at Pegu.

The columns shown represent the personnel totals for (running from the top row to the bottom) Blocks 1, 2, 6, 7, 8 and solitary confinement. (Image is courtesy and copyright of Miranda Skinner).

The hospitalship pulled away from Rangoon and headed back across the Bay of Bengal to the Indian mainland, disembarking at Calcutta. (Pictured here are the POW's leaving the ship in Calcutta).

Seen below are the final numbers of prisoners still left in the jail as of May 1st 1945. The listing was collated by the senior officers still present within the prison at that time, these included John Murray Kerr, Tim Finnerty and Lionel Hudson.

The roll shows all the varying nationalities present in Rangoon Jail on that date, but obviously does not include the 400 men who marched out just a few days before and were liberated at Pegu.

The columns shown represent the personnel totals for (running from the top row to the bottom) Blocks 1, 2, 6, 7, 8 and solitary confinement. (Image is courtesy and copyright of Miranda Skinner).

It is difficult and probably wrong to single out individuals from the Chindits of Rangoon Jail. However, men such as Graham Hosegood, Jock Masterton, Brian Horncastle and Private Golding all stand out from the crowd and all served their fellow inmates well during those long months as prisoners of war.

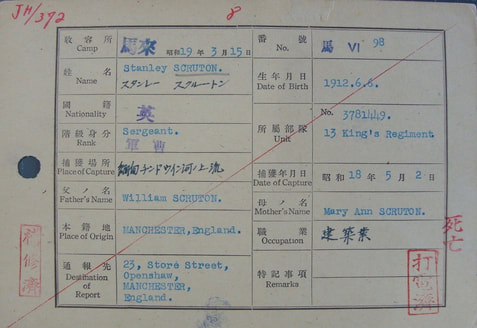

Opposite is the Japanese Index card (please click on the image to bring it forward on the page) for Sergeant Stanley Scruton, possibly the most selfless of all these men. In his mind he was responsible for a group of men becoming POW after a mistake was made crossing the Shweli River in April 1943. He worked tirelessly in the makeshift hospital in the jail, almost as his way of making amends.

For a long time in the jail he was the senior ranked soldier in the hospital whilst all the actual Medical officers were being held in solitary confinement. Stanley died of exhaustion and the ravages of beri beri on 13th May 1944. He was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery alongside many of men he had so tenderly cared for.

To end this section here is what Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding one of the Chindit officers from 1943 said of Scruton in his memoirs:

A bricklayer's labourer by trade. I am sure that his (Scruton) death was at least in part, due to frustration because he could do so little for his charges. He was a splendid chap.

To read more about Stanley Scruton and how he ended up as a prisoner or war, please click on the following link: Eric Allen and the Lost Boat on the Shweli

Update 23/07/2012

From the records kept by Captain Tommy Roberts, we now know that some of the men who made the gruelling journey from the Maymyo concentration camp down to Rangoon, died almost immediately on arrival at the Central Jail. The following men were buried at St. Mary's Catholic Church cemetery: Sgt. Edward Gunn, Pte. Fred Lowe and Pte. Francis Cyril Fairhurst.

Update 20/12/2012

For more information about the Maymyo Concentration Camp, please click the link below.

Maymyo Camp

Update 28/01/2013

For information about what happened to some of the Gurkha Riflemen captured in 1943, please click on the following link:

The Trials of Purna Bahadur Gurung

Update 04/02/2013

For information about alleged Japanese medical experiments performed on Longcloth Chindits, please click on the following link:

Japanese Experimentation on POW's

Update 19/07/2013

From the personal papers of Lieutenant John Murray Kerr. Official War Office notices for families in regard to enquiring about and contacting Prisoners of War suspected of being held by the Japanese. Images courtesy of Miranda Skinner. Please click on each image to enlarge.

Opposite is the Japanese Index card (please click on the image to bring it forward on the page) for Sergeant Stanley Scruton, possibly the most selfless of all these men. In his mind he was responsible for a group of men becoming POW after a mistake was made crossing the Shweli River in April 1943. He worked tirelessly in the makeshift hospital in the jail, almost as his way of making amends.

For a long time in the jail he was the senior ranked soldier in the hospital whilst all the actual Medical officers were being held in solitary confinement. Stanley died of exhaustion and the ravages of beri beri on 13th May 1944. He was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery alongside many of men he had so tenderly cared for.

To end this section here is what Lieutenant 'Willie' Wilding one of the Chindit officers from 1943 said of Scruton in his memoirs:

A bricklayer's labourer by trade. I am sure that his (Scruton) death was at least in part, due to frustration because he could do so little for his charges. He was a splendid chap.

To read more about Stanley Scruton and how he ended up as a prisoner or war, please click on the following link: Eric Allen and the Lost Boat on the Shweli

Update 23/07/2012

From the records kept by Captain Tommy Roberts, we now know that some of the men who made the gruelling journey from the Maymyo concentration camp down to Rangoon, died almost immediately on arrival at the Central Jail. The following men were buried at St. Mary's Catholic Church cemetery: Sgt. Edward Gunn, Pte. Fred Lowe and Pte. Francis Cyril Fairhurst.

Update 20/12/2012

For more information about the Maymyo Concentration Camp, please click the link below.

Maymyo Camp

Update 28/01/2013

For information about what happened to some of the Gurkha Riflemen captured in 1943, please click on the following link:

The Trials of Purna Bahadur Gurung

Update 04/02/2013

For information about alleged Japanese medical experiments performed on Longcloth Chindits, please click on the following link:

Japanese Experimentation on POW's

Update 19/07/2013

From the personal papers of Lieutenant John Murray Kerr. Official War Office notices for families in regard to enquiring about and contacting Prisoners of War suspected of being held by the Japanese. Images courtesy of Miranda Skinner. Please click on each image to enlarge.

Listed below are the men from operation Longcloth who became POW's in 1943. As I stated earlier in this section, I believe that there were more men taken prisoner in the field of combat and held at places like Bhamo jail and the Maymyo concentration camp, but who sadly, never made the journey to Rangoon Jail. Also shown on the lists below are the handful of men taken from Rangoon Jail by the Japanese secret police (Kempai-Tai) and sent to their Singapore headquarters for further interrogation. These men were eventually released from Changi POW camp.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Update 10/10/2013.

The Chindit prisoners in Rangoon Jail gave humorous nicknames to some of their Japanese guards, usually depicting a physical characteristic or personality trait. Guards such as:

'Pompous Percy', who was present on the Pegu march in 1945; an arrogant and obnoxious creature.

'The Kicker', no need to explain this man's special skill I shouldn't think.

'The Jockey', said to be the guard responsible for bayonetting stragglers on the Pegu march in April 1945. His nickname came from the style of his Army cap.

'Creeping Jesus', a bespectacled guard who attempted to surprise POW's by appearing out of nowhere, then beating them for not acknowledging his presence with a bow.

'Smiler', a decent character unluckily killed by an Allied bombing raid on the jail.

'Weary Willie', could be hot or cold, typical Jap. (Quote by Denis Gudgeon).

Others included:

The Bullfog, Limpy, Little Lance Corporal, Moose Face, Death Warmed Up and The Bulldozer.

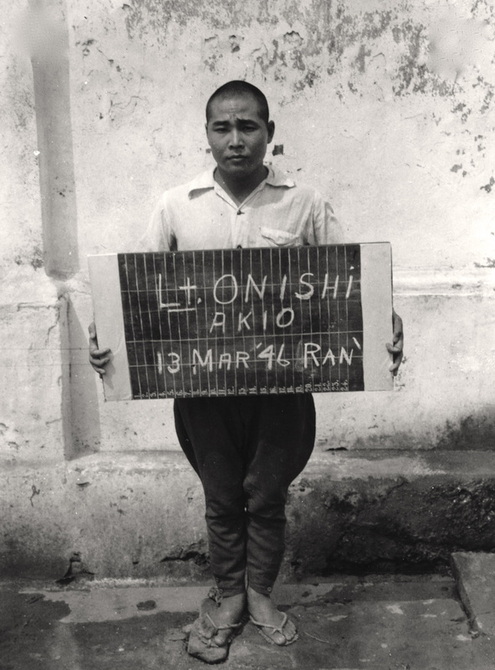

Medical Officer Lieutenant Akio Onishi was the senior Japanese doctor in Rangoon Jail, he withheld drugs from being administered to POW's causing great and unnecessary suffering. He was also probably involved in the callous experimentation on prisoners, testing the effects of malarial strains on the already physically exhausted men. Sentenced to death by a War Crimes Court after the war, this sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. See photograph below. For more information about the experimentation on the Chindit POW's and others, please click here:

Japanese Experimentation on POW's

Sgt. Samuel Quick.

Sgt. Samuel Quick.

Update 30/10/2013.

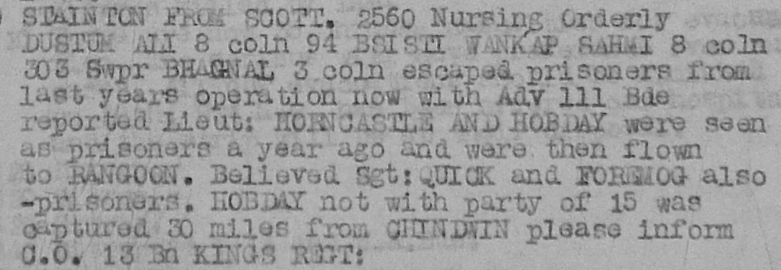

Confirmed POW Status of Edward Hobday, Brian Horncastle and Samuel Quick

Whilst researching the 1944 Chindit operation, codenamed 'Thursday', some interesting documents have come to light which mention the recovery of POW's in the field who were members of Operation Longcloth in 1943. Taken from the War Diary of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in 1944 the following extracts reveal Gurkha, Indian and Burmese personnel who were captured on Longcloth and were employed by the Japanese as porters and mule transport during the time of the enemy build up for the invasion of India and the battles at Imphal and Kohima.

In 1944 as Chindit units moved through areas in the rear of the Japanese lines they liberated small groups of men from villages and towns, or as news of the new Chindit force began to perculate through to these locations, the POW's grew in confidence and escaped their captors and re-joined the Allied cause.

The first image shown below tells of three Indian personnel, two formerly with Major Scott's 8 Column and one Gurkha other rank from Mike Calvert's 3 Column. They were recovered by the advance of 111th Brigade in 1944 and had information confirming the POW status of two 13th King's officers, Lieutenants Horncastle and Hobday, a Sgt. Quick and a soldier by the name of Foremog. Of the latter I know nothing, but the other three men were all part of Column 8 in 1943. Sadly, Lieutenants Horncastle and Hobday did not survive the war, in fact it was not until I read this short report that it became apparent that Edward William Hobday had at one point been a prisoner of war. To see Edward's CWGC details, please click on the link below:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2511502/HOBDAY,%20EDWARD%20WILLIAM

The War Diary for Column 8 has this entry for April 1st 1943:

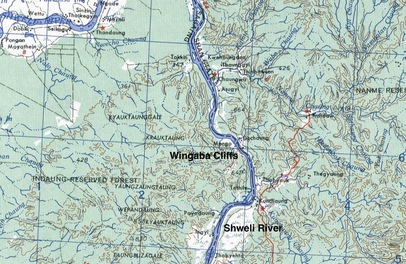

" A recce of the River Shweli was taken this afternoon and it was decided to attempt to cross tonight near the Wingaba Cliffs S.N. 2563. Column moved down to the river at dusk. Rope was got across, but the river was flowing very fast on the near side. Capt. Williams, with Lieutenants Hobday and Horton and 29 Other Ranks crossed over to form a bridgehead. The next party across under Sgt. Scruton got into difficulties mid-stream and had to cut the rope, both Scruton's boat and the rope were lost. Capt. Williams and his party moved off from the far bank at first light the following day."

From that point onward nothing more was heard of Captain Williams or any of his group. We now know that Edward Hobday was captured by the Japanese, but we still do not understand the details of his death on 17th April 1943. Lieutenant Horton ended up a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail and did survive this ordeal, he was liberated in late April 1945.

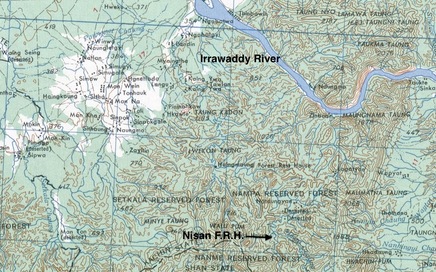

Lt. Horncastle was still with the main body of Column 8 as they moved away from the Shweli River, they succeeded in taking a full supply drop not long afterward and then continued their march. After several days they had reached a place called the Nisan Forest and had set up camp near a small stream or chaung. The Chindits location was given away by some local Burmese and a fierce firefight took place between a Japanese company and the men of Column 8. Several Chindit casualties were suffered from Japanese mortars and machine gun fire. Eventually Major Scott led his men westward, to some higher ground and away from the Nisan Rest House area.

On the 12th April, Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke ordered that a stretcher party be formed to assist with the moving of the wounded men. He also asked for a recce patrol to be sent back toward the Nisan Rest House in order to ascertain the strength and location of the enemy. Lt. Horncastle led this recce patrol. By the evening of the 12th both Lt. Horncastle and 14 Other Ranks were reported missing. One of the missing men was Sgt. Quick. From the War diary of Column 8, an entry dated 13th April:

"Reveille at 04.30 hrs. attempts were made to find Horncastle's party, but no contact made by 15.00 hrs. Column moved southward and reached the Nampa Chaung at dusk. Route very tough and jarring for the wounded and stretcher bearers. Conference of Officers agreed that a supply drop should be asked for, then for the Column to break up into dispersal groups before heading for the Irrawaddy once more. It is thought that Lt. Horncastle may have decided to move off as a separate dispersal party."

From the diary entry below it is now clear that he had become a prisoner of war. Brian Pape Horncastle worked tirelessly in Rangoon Jail trying to care for his ailing men in the makeshift hospital, he died in February 1944 and was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery. An explanation of Lieutenant Horncastle's death can be found in the personal memoirs of another Chindit POW from 1943, Lieutenant R.A. Wilding.

"Brian was always a kind and helpful man and quiet about it too. He was troubled about the danger of jungle sores and experimented on his own with carbolic. The sores became infected and gangrenous from which he died. All this happened while there was no Medical Officer available in Block 6."

NB. At that time the senior Medical Officer for the Chindits, Major Raymond Ramsay was still being held in a solitary confinement cell in another part of the jail.

Sgt. Samuel Anthony Quick was liberated from Rangoon Jail in May 1945 as part of the Pegu Marchers group (see story earlier on this page) and returned to the 13th Battalion who by then were stationed at Karachi, from here he was repatriated to the United Kingdom.

Confirmed POW Status of Edward Hobday, Brian Horncastle and Samuel Quick

Whilst researching the 1944 Chindit operation, codenamed 'Thursday', some interesting documents have come to light which mention the recovery of POW's in the field who were members of Operation Longcloth in 1943. Taken from the War Diary of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in 1944 the following extracts reveal Gurkha, Indian and Burmese personnel who were captured on Longcloth and were employed by the Japanese as porters and mule transport during the time of the enemy build up for the invasion of India and the battles at Imphal and Kohima.

In 1944 as Chindit units moved through areas in the rear of the Japanese lines they liberated small groups of men from villages and towns, or as news of the new Chindit force began to perculate through to these locations, the POW's grew in confidence and escaped their captors and re-joined the Allied cause.

The first image shown below tells of three Indian personnel, two formerly with Major Scott's 8 Column and one Gurkha other rank from Mike Calvert's 3 Column. They were recovered by the advance of 111th Brigade in 1944 and had information confirming the POW status of two 13th King's officers, Lieutenants Horncastle and Hobday, a Sgt. Quick and a soldier by the name of Foremog. Of the latter I know nothing, but the other three men were all part of Column 8 in 1943. Sadly, Lieutenants Horncastle and Hobday did not survive the war, in fact it was not until I read this short report that it became apparent that Edward William Hobday had at one point been a prisoner of war. To see Edward's CWGC details, please click on the link below:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2511502/HOBDAY,%20EDWARD%20WILLIAM

The War Diary for Column 8 has this entry for April 1st 1943:

" A recce of the River Shweli was taken this afternoon and it was decided to attempt to cross tonight near the Wingaba Cliffs S.N. 2563. Column moved down to the river at dusk. Rope was got across, but the river was flowing very fast on the near side. Capt. Williams, with Lieutenants Hobday and Horton and 29 Other Ranks crossed over to form a bridgehead. The next party across under Sgt. Scruton got into difficulties mid-stream and had to cut the rope, both Scruton's boat and the rope were lost. Capt. Williams and his party moved off from the far bank at first light the following day."

From that point onward nothing more was heard of Captain Williams or any of his group. We now know that Edward Hobday was captured by the Japanese, but we still do not understand the details of his death on 17th April 1943. Lieutenant Horton ended up a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail and did survive this ordeal, he was liberated in late April 1945.

Lt. Horncastle was still with the main body of Column 8 as they moved away from the Shweli River, they succeeded in taking a full supply drop not long afterward and then continued their march. After several days they had reached a place called the Nisan Forest and had set up camp near a small stream or chaung. The Chindits location was given away by some local Burmese and a fierce firefight took place between a Japanese company and the men of Column 8. Several Chindit casualties were suffered from Japanese mortars and machine gun fire. Eventually Major Scott led his men westward, to some higher ground and away from the Nisan Rest House area.

On the 12th April, Lieutenant-Colonel Cooke ordered that a stretcher party be formed to assist with the moving of the wounded men. He also asked for a recce patrol to be sent back toward the Nisan Rest House in order to ascertain the strength and location of the enemy. Lt. Horncastle led this recce patrol. By the evening of the 12th both Lt. Horncastle and 14 Other Ranks were reported missing. One of the missing men was Sgt. Quick. From the War diary of Column 8, an entry dated 13th April:

"Reveille at 04.30 hrs. attempts were made to find Horncastle's party, but no contact made by 15.00 hrs. Column moved southward and reached the Nampa Chaung at dusk. Route very tough and jarring for the wounded and stretcher bearers. Conference of Officers agreed that a supply drop should be asked for, then for the Column to break up into dispersal groups before heading for the Irrawaddy once more. It is thought that Lt. Horncastle may have decided to move off as a separate dispersal party."

From the diary entry below it is now clear that he had become a prisoner of war. Brian Pape Horncastle worked tirelessly in Rangoon Jail trying to care for his ailing men in the makeshift hospital, he died in February 1944 and was buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery. An explanation of Lieutenant Horncastle's death can be found in the personal memoirs of another Chindit POW from 1943, Lieutenant R.A. Wilding.

"Brian was always a kind and helpful man and quiet about it too. He was troubled about the danger of jungle sores and experimented on his own with carbolic. The sores became infected and gangrenous from which he died. All this happened while there was no Medical Officer available in Block 6."

NB. At that time the senior Medical Officer for the Chindits, Major Raymond Ramsay was still being held in a solitary confinement cell in another part of the jail.

Sgt. Samuel Anthony Quick was liberated from Rangoon Jail in May 1945 as part of the Pegu Marchers group (see story earlier on this page) and returned to the 13th Battalion who by then were stationed at Karachi, from here he was repatriated to the United Kingdom.

Below are some maps and images that relate to the stories of Lieutenants Hobday and Horncastle. Please click on the maps and photographs to enlarge.

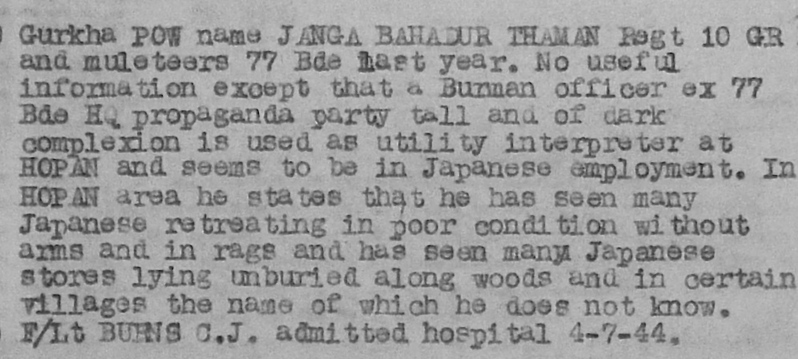

The next entry is from the 1944 War diary for the 77th Brigade and shows the details of a 10th Gurkha Rifleman, Janga Bahadur Thaman. Janga was a muleteer on Operation Longcloth and was employed as such by his Japanese captors during his time as a POW. Gurkha troops from the 10th Regiment were attached to Operation Longcloth at the very last hour before entering Burma, these men were already trained as mule handlers and provided this expertise on the expedition. For a more detailed account of a captured Gurkha muleteer and his time as a POW please read The Trials of Purna Bahadur Gurung.

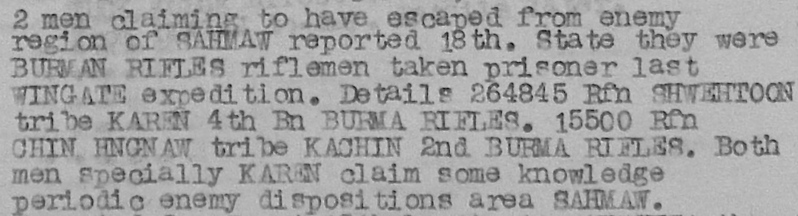

The final diary entry records the recovery of two Burma Riflemen who took part in the operation of 1943 and who were captured by the Japanese. There is nothing of real interest within the report, although the two men do claim to have important intelligence on Japanese positions in the area around Sahmaw. The engrossing aspect of this report really only comes with the fact that it was extremely unusual for men from the Burma Rifles to be captured in the first instance. So, Rifleman Shwehtoon from the Karen tribe and Rifleman Chin Hngnaw, a Kachin were unique in this respect.

Update 16/05/2016.

I should have placed the following video links on this page many moons ago. The first is an eight minute film recording the liberation of the POW's marched out of Rangoon Jail by the Japanese guards on the 24th April 1945. They are shown receiving food and new clothing from their liberators, the soldiers of the West Yorkshire Regiment, who as part of the advancing 14th Army came across the former prisoners of war at a small village named Waw situated very close to the Burmese town of Pegu.

Liberation of the Pegu marchers

The second film is an American Combat bulletin showing the release of the men who remained inside Rangoon Jail and did not march out to Pegu on 24th April 1945. Most of these prisoners were deemed too ill or infirm to make the march, but found that on the morning of the 29th April, the Japanese had vacated the jail and indeed the city itself. The section of the film showing the POW's from Rangoon can be seen around the 15 minute mark.

POW's Liberated from Rangoon Central Jail

I recently received an email contact from the family of Chindit POW, Tom Worthington. The family provided me with several photographs, including the one shown below. The image is of eight POW's and was taken shortly after their liberation at the village of Waw on the 29th April 1945. Tom Worthington is the tall man, seen third from the right as we look. In front of him (second right) is Tommy Byrne and I believe, although I cannot be 100% certain, that the man seen third from the left is Leon Frank. It would be fantastic if over the course of time, we could identify the rest of the group.

I should have placed the following video links on this page many moons ago. The first is an eight minute film recording the liberation of the POW's marched out of Rangoon Jail by the Japanese guards on the 24th April 1945. They are shown receiving food and new clothing from their liberators, the soldiers of the West Yorkshire Regiment, who as part of the advancing 14th Army came across the former prisoners of war at a small village named Waw situated very close to the Burmese town of Pegu.

Liberation of the Pegu marchers

The second film is an American Combat bulletin showing the release of the men who remained inside Rangoon Jail and did not march out to Pegu on 24th April 1945. Most of these prisoners were deemed too ill or infirm to make the march, but found that on the morning of the 29th April, the Japanese had vacated the jail and indeed the city itself. The section of the film showing the POW's from Rangoon can be seen around the 15 minute mark.

POW's Liberated from Rangoon Central Jail

I recently received an email contact from the family of Chindit POW, Tom Worthington. The family provided me with several photographs, including the one shown below. The image is of eight POW's and was taken shortly after their liberation at the village of Waw on the 29th April 1945. Tom Worthington is the tall man, seen third from the right as we look. In front of him (second right) is Tommy Byrne and I believe, although I cannot be 100% certain, that the man seen third from the left is Leon Frank. It would be fantastic if over the course of time, we could identify the rest of the group.

Major John Finnerty.

Major John Finnerty.

Update 29/12/2017.

Major John Finnerty

From the book, All Quiet on the Irrawaddy, written by Major John 'Tim' Finnerty of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, comes a vivid description of the preparation at Rangoon Jail for a soldier's funeral. Tim Finnerty had been captured in 1942 and became one of the highest ranked NCO's present in the jail during his three year incarceration. Although obviously fit enough to be included on the march out to Pegu in late April 1945, Finnerty chose to remain behind and look after the remaining sick and wounded men.

Having been taken prisoner at a time when the Japanese had spectacular successes in South East Asia and the Pacific, one could only think of freedom years ahead in the distant future. But as we moved the seriously wounded and those very ill to an end cell set up as a hospital in our block it became painfully obvious that their release through death was only a matter of time. Next day, after evening roll call, I was just in time to see a private soldier who had been in great pain reach the end of his journey. Watching his final convulsions I could not help wondering how long it would be before his mother heard of his death, or whether she would go on thinking during the war that her Tommy would turn up when it was all over.

When I informed the Japanese, they said the burial would be next morning. We removed his body to a tool shack in the garden, and a couple of his friends took turns guarding the corpse to prevent mutilation by animals. Visiting the mortuary during the night I was surprised to find two men where there was only room for one, and their whispered replies were scarcely audible because they did not want to disturb their dead pal. It was explained to me that all three were close friends who wanted to be together on this night. Next morning the Japanese gave me a sack for the body and said the funeral party would be myself and six others.

We felt it important for all those in the block to pay their last respects to the dead man, and everyone fit to stand paraded in two ranks facing inwards. The funeral cortege moved through in slow time, the body carried on a wooden platform covered by the Union Jack. This became the form of parade for all too many funerals. Some insisted on taking part who were very unfit, but no matter how strong the sun they would stand rigidly at attention, and add all possible dignity to the occasion. Needless to add, some of their own funerals were to be in the not too distant future.

This was all so different from civilian funerals at home, where death had probably occurred in hospital. There, the body would be taken to the mortuary, followed by a funeral; a quiet sombre affair of relatives wearing their best dark suits, flowers, a hearse, a cortege of hired cars and back to work next day. But now, in some cases, the corpse remained in the cell until carried out feet first, wrapped in hessian, the next day. The close proximity of the dead to the living, even for this short time, made some think deeply, and depressed others.

Our funeral party was conveyed to the British Cemetery in a dilapidated truck, where a newly dug grave was pointed out. The Japanese stood back, we prayed according to our religion and lowered the body into the grave; but when it was only half filled in the escort said it was time to return to the jail. Before and during the burial was the only time the Japanese kept remarkably silent. As time passed it was not unusual to be sent for during the night as death was imminent. There one found the dying man being comforted quietly by his friends. None died lonely.

A Corporal belonging to an English county regiment sent for me one night; he was one of three expected to die within hours; before being called up less than two years earlier, he worked in his native Leeds. He was an intelligent man and realised his end was near. The effort of every word he spoke was reducing his time, but he insisted on having his final say, despite my plea for him to relax. "I don't mind dying, if only people at home are told how we have been treated here." he said, and died shortly afterwards.

Major John Finnerty

From the book, All Quiet on the Irrawaddy, written by Major John 'Tim' Finnerty of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, comes a vivid description of the preparation at Rangoon Jail for a soldier's funeral. Tim Finnerty had been captured in 1942 and became one of the highest ranked NCO's present in the jail during his three year incarceration. Although obviously fit enough to be included on the march out to Pegu in late April 1945, Finnerty chose to remain behind and look after the remaining sick and wounded men.

Having been taken prisoner at a time when the Japanese had spectacular successes in South East Asia and the Pacific, one could only think of freedom years ahead in the distant future. But as we moved the seriously wounded and those very ill to an end cell set up as a hospital in our block it became painfully obvious that their release through death was only a matter of time. Next day, after evening roll call, I was just in time to see a private soldier who had been in great pain reach the end of his journey. Watching his final convulsions I could not help wondering how long it would be before his mother heard of his death, or whether she would go on thinking during the war that her Tommy would turn up when it was all over.

When I informed the Japanese, they said the burial would be next morning. We removed his body to a tool shack in the garden, and a couple of his friends took turns guarding the corpse to prevent mutilation by animals. Visiting the mortuary during the night I was surprised to find two men where there was only room for one, and their whispered replies were scarcely audible because they did not want to disturb their dead pal. It was explained to me that all three were close friends who wanted to be together on this night. Next morning the Japanese gave me a sack for the body and said the funeral party would be myself and six others.

We felt it important for all those in the block to pay their last respects to the dead man, and everyone fit to stand paraded in two ranks facing inwards. The funeral cortege moved through in slow time, the body carried on a wooden platform covered by the Union Jack. This became the form of parade for all too many funerals. Some insisted on taking part who were very unfit, but no matter how strong the sun they would stand rigidly at attention, and add all possible dignity to the occasion. Needless to add, some of their own funerals were to be in the not too distant future.

This was all so different from civilian funerals at home, where death had probably occurred in hospital. There, the body would be taken to the mortuary, followed by a funeral; a quiet sombre affair of relatives wearing their best dark suits, flowers, a hearse, a cortege of hired cars and back to work next day. But now, in some cases, the corpse remained in the cell until carried out feet first, wrapped in hessian, the next day. The close proximity of the dead to the living, even for this short time, made some think deeply, and depressed others.

Our funeral party was conveyed to the British Cemetery in a dilapidated truck, where a newly dug grave was pointed out. The Japanese stood back, we prayed according to our religion and lowered the body into the grave; but when it was only half filled in the escort said it was time to return to the jail. Before and during the burial was the only time the Japanese kept remarkably silent. As time passed it was not unusual to be sent for during the night as death was imminent. There one found the dying man being comforted quietly by his friends. None died lonely.

A Corporal belonging to an English county regiment sent for me one night; he was one of three expected to die within hours; before being called up less than two years earlier, he worked in his native Leeds. He was an intelligent man and realised his end was near. The effort of every word he spoke was reducing his time, but he insisted on having his final say, despite my plea for him to relax. "I don't mind dying, if only people at home are told how we have been treated here." he said, and died shortly afterwards.

Lt. Charles Coubrough, India 1945.

Lt. Charles Coubrough, India 1945.

Update 06/08/2018.

Lt. Charles Couborough

From the book, Memories of a Perpetual Second Lieutenant, by Charles Coubrough formerly of the Indian Army (7/10 Baluchis), comes an informative account of what happened to Rangoon Jail in the years after WW2. I would like to thank Charles, who has since sadly passed away, for all his time and assistance back in 2010, when we spoke in relation to his time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon during the years 1942-45.

Rangoon, January 1976:

I had already been informed that a visit to the jail was not possible due to the political situation in Burma. However, I knew that a road now ran through the site of the old jail and I decided to hire a taxi and take a chance in passing down this avenue. As we traveled on this road, we found a number of small stores or shops on the left hand side alongside the remains of the old jail wall. All the other buildings on the left side of the road had been destroyed. On the right hand side stood the prison blocks and central water tower, these were guarded by four or five Burmese soldiers holding their rifles in both hands with fixed bayonets.

With excitement and curiosity I got out of the car and walked into this compound and stopped by the water tower. With their green uniforms and inscrutable faces, the Burmese were not unlike the Japanese guards of thirty years past. I tried to find my bearings in identifying each of the prison blocks and it was at this point that we were asked in no uncertain terms to leave. I continued down the Prome Road on foot and turned right into what had been the old jail entrance. The corridor to the guardhouse seemed much longer than I remembered and was now occupied by a number of Burmese families. It was from this location that I was able to find my bearings and pick out each of the jail blocks I had occupied during my imprisonment.

Previously on my tour, we had driven up to Pegu from Rangoon and retraced the 55 miles taken by those of us who had marched out of the jail in late April 1945. I noticed how little cover there was on either side of the road and how exposed we really had been to aerial attack by the RAF. I attempted to identify the wooded glades, where we 400 prisoners had rested up during that long march. It was shortly after this that our coach suffered a puncture whilst travelling at 50mph. The driver just, but only just, kept the coach from overturning and plunging down into the rice fields below the road. While the driver and some local villagers attempted to replace the wheel, I wandered through the woody thickets on that side of the track and realised that this was the exact location where back in 1945, we had been attacked by our own planes, zooming overhead and machine-gunning us on the road. It seemed ironic, that I had come nearer to death just a few yards away and in peaceful conditions some 30 years later.

Lt. Charles Couborough

From the book, Memories of a Perpetual Second Lieutenant, by Charles Coubrough formerly of the Indian Army (7/10 Baluchis), comes an informative account of what happened to Rangoon Jail in the years after WW2. I would like to thank Charles, who has since sadly passed away, for all his time and assistance back in 2010, when we spoke in relation to his time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon during the years 1942-45.

Rangoon, January 1976:

I had already been informed that a visit to the jail was not possible due to the political situation in Burma. However, I knew that a road now ran through the site of the old jail and I decided to hire a taxi and take a chance in passing down this avenue. As we traveled on this road, we found a number of small stores or shops on the left hand side alongside the remains of the old jail wall. All the other buildings on the left side of the road had been destroyed. On the right hand side stood the prison blocks and central water tower, these were guarded by four or five Burmese soldiers holding their rifles in both hands with fixed bayonets.