Chindit Memorials, Cemeteries and Graves

This page is devoted to the men of Operation Longcloth and where they are remembered, whether this be in a Commonwealth Graves War Cemetery or simply on the local War Memorial for the town where they had lived. This picture gallery will hopefully grow over time as new images come in to my possession. Thank you in advance to all the contributors responsible for helping me build this page and the information found on it. If anyone has an image for, or is aware of any other relevant memorial suitable for this collection, then I would be happy to include it.

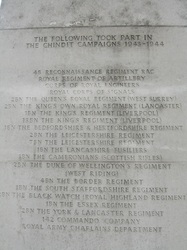

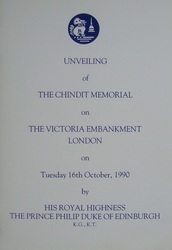

We will begin with the Chindit Memorial which is situated on the Victoria Embankment, London, which was unveiled on the 16th October 1990 by the Duke of Edinburgh. Photographs courtesy of Edward Chandler, please click on the images to enlarge. For more information please follow the link here: http://www.chindits.info/Memorial/Main.html

We will begin with the Chindit Memorial which is situated on the Victoria Embankment, London, which was unveiled on the 16th October 1990 by the Duke of Edinburgh. Photographs courtesy of Edward Chandler, please click on the images to enlarge. For more information please follow the link here: http://www.chindits.info/Memorial/Main.html

The next general Chindit Memorial can be found in the grounds of the National Arboretum in Staffordshire. The Arboretum is an amazing place to visit and has as it's centre piece the 'Armed Forces Memorial', which honours the men and women of Her Majesty's Armed Forces who have lost their lives in conflict or as the result of terrorism since the end of the Second World War. For more information please follow the link here: http://www.thenma.org.uk

On the 15th August 2013 a commemoration service took place at the Chindit Memorial. It marked the 68th Anniversary of the Victory over Japan, but also the consecration of the Memorial with the addition of a new bronze statue of a Chinthe (the mythical beast that stands protective over many Burmese Pagodas and from which the Chindits took their name in 1943).

The statue was cast from a wooden carving made by Roger Neal, the Public Relations Officer of the Birmingham Branch of the Burma Star Association. Amongst other roles, Roger also performs duties for the Association as a Standard Bearer.

Roger explained:

"I was very relieved to finally get the carving to the foundry. The week it was mounted and consecrated was just so full of emotion, I was completely drained. I have trouble accepting that something I have had a hand in will be around long after I'm not. Seeing the emotions of the Chindits and knowing what it means to them is what is more important, and that is what makes the last few years of wondering if I could even complete it, fighting with myself over how to even try to do it, so worthwhile. At the commemoration the Chindits present just kept coming up to me and thanking me for my efforts, I don't deserve their thanks, it is me who should be thanking them for what they did, to give us a chance to live in peace."

Roger continued:

"My father was in Burma in 20th Indian Division (1st Northamptonshire Regiment) as a Regimental Signaller, involved around the Imphal area starting at Kyaukchaw and covering the 17th Division's retreat to Silchar. After this he went forward again through the battle of Imphal until he was injured in the chest, resulting in a collapsed lung and his evacuation away from the front. From the effects of his injury he was deemed unfit for front line service and became an instructor. I wish he could have seen the finished statue."

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Roger, not only for his time and endeavour in producing this wonderful tribute to the Chindits and their memory, but also for allowing me to record his words and to display some photographs of his craftsmanship.

The statue was cast from a wooden carving made by Roger Neal, the Public Relations Officer of the Birmingham Branch of the Burma Star Association. Amongst other roles, Roger also performs duties for the Association as a Standard Bearer.

Roger explained:

"I was very relieved to finally get the carving to the foundry. The week it was mounted and consecrated was just so full of emotion, I was completely drained. I have trouble accepting that something I have had a hand in will be around long after I'm not. Seeing the emotions of the Chindits and knowing what it means to them is what is more important, and that is what makes the last few years of wondering if I could even complete it, fighting with myself over how to even try to do it, so worthwhile. At the commemoration the Chindits present just kept coming up to me and thanking me for my efforts, I don't deserve their thanks, it is me who should be thanking them for what they did, to give us a chance to live in peace."

Roger continued:

"My father was in Burma in 20th Indian Division (1st Northamptonshire Regiment) as a Regimental Signaller, involved around the Imphal area starting at Kyaukchaw and covering the 17th Division's retreat to Silchar. After this he went forward again through the battle of Imphal until he was injured in the chest, resulting in a collapsed lung and his evacuation away from the front. From the effects of his injury he was deemed unfit for front line service and became an instructor. I wish he could have seen the finished statue."

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Roger, not only for his time and endeavour in producing this wonderful tribute to the Chindits and their memory, but also for allowing me to record his words and to display some photographs of his craftsmanship.

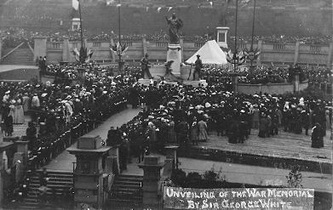

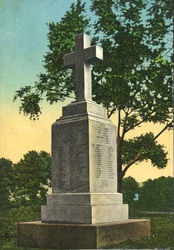

The next set of photographs are of the King's Liverpool Regimental Memorial in St. John's Gardens, Liverpool. The memorial was unveiled by Field Marshall Sir George White on the 9th of September 1905. The manufacturer and mason were William Kirkpatrick Limited and the designer Sir William Goscombe John. These photographs are courtesy of Marc Fogden (please click on the image to enlarge), with kind thanks to Ozzy Graves from the Liverpool Branch of the Burma Star Association for his help and assistance.

For more information about the memorial please click on the link here: http://www.victorianweb.org/sculpture/john/9.html

For more information about the memorial please click on the link here: http://www.victorianweb.org/sculpture/john/9.html

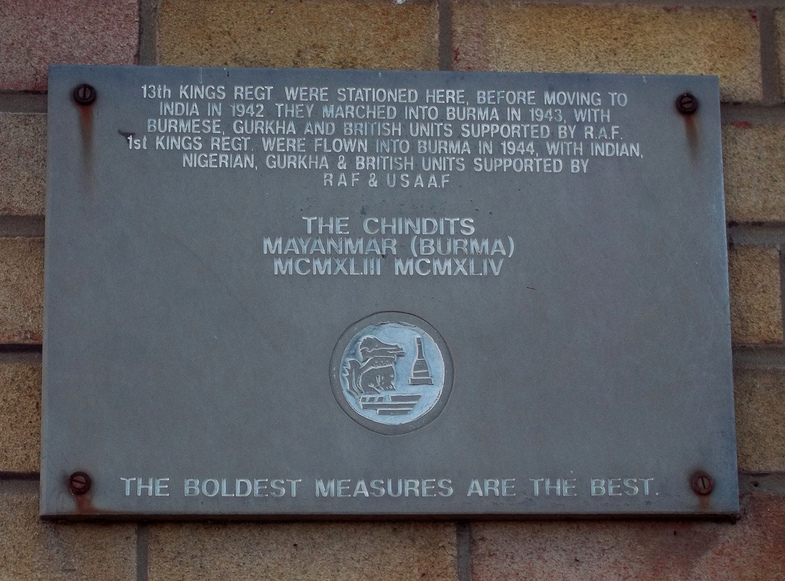

The image below is the memorial plaque for the Kings Liverpool battalions who served in Burma during WW2. It commemorates the 13th Kings presence at the Harington Barracks, located at Formby in Merseyside, just before they left for their service overseas in India. Sadly, the barracks no longer exist and were demolished to make way for a housing estate in the 1960's. For more information on the Harrington Barracks including some contemporary images, please click on the following link: www.kingsownmuseum.com/gallery4559formby01.htm

From the Formby Times in 2008:

Formby's Harington Barracks is remembered

March 13th 2008

by Clifford Birchall, Formby Times.

Formby Civic Society's Dr. Reg Yorke was one of the thousands of soldiers who passed through Harington Barracks, yet very few people are aware these days of its presence. "I spent my first six weeks of Army life there from February 1947, before moving on to the 17th Training Regiment, Royal Artillery on the Salisbury Plain." He is particularly anxious to have Formby's role in the life of the King's Regiment, which underwent amalgamation recently, acknowledged.

The King's Liverpool Regiment depot and Regimental Infantry Training Centre was in Formby, at Harington Barracks, throughout World War Two. Prior to the outbreak of war the King's Depot was based at Seaforth, but in view of the need for much more accommodation and an expanded military training area, a new barracks was rapidly constructed as a 'hutted camp' in 1940 on open farm land, some farmed by John Brooks of Larkhill Farm, between Formby village and the coast (in the area where Harington Road is today).

This became the King's Regiment Infantry Training Centre and continued in the early part of the war to receive 200 recruits every fortnight. The War Office originally planned to take over Formby Golf Club which was in fact used as officer's accommodation for a period, but in the end the new purpose-built barracks was built with vehicular access from Victoria Road and pedestrian access via Blundell Path. This path, which still survives today was the shortest route to the nearest rail station.

The barracks was named after the former Colonel in Chief, General Sir Charles Harington, GCB, GYIE, DSO who died in 1940. From 1941 to 1945 the Commanding Officer was Lieutenant-Colonel Burke Gaffney MC, who soon established a good relationship with the local residents. He later wrote the official history of the modern regiment, 'The Story of the King's Regiment (Liverpool) 1914-1948'.

Training took place in large gyms, on a large parade ground and on the surrounding open fields. There were football pitches and an athletic ground on the west side of Larkhill Lane (where the National Trust heath reserve is today). Rifle training began using .22 Rifles in a covered range situated near where St. Jerome's Church is today. Following this, further practice took place on the open range at the seaward end of Albert Road; followed by practice at the Altcar Rifle Range, then reached by a track across Marsh Farm from Range Lane.

A short black and white sound film exists produced by the Army Kinema Corporation, this is of the Queen Mother's visit to the barracks in 1954 to review and present the new colours to the 1st Battalion of the Manchester Regiment who were by then in residence. The Formby Civic Society also have a number of photographs of this visit.

Many thanks to Val Gornell for sending me this short article on the history of Harington Barracks.

From the Formby Times in 2008:

Formby's Harington Barracks is remembered

March 13th 2008

by Clifford Birchall, Formby Times.

Formby Civic Society's Dr. Reg Yorke was one of the thousands of soldiers who passed through Harington Barracks, yet very few people are aware these days of its presence. "I spent my first six weeks of Army life there from February 1947, before moving on to the 17th Training Regiment, Royal Artillery on the Salisbury Plain." He is particularly anxious to have Formby's role in the life of the King's Regiment, which underwent amalgamation recently, acknowledged.

The King's Liverpool Regiment depot and Regimental Infantry Training Centre was in Formby, at Harington Barracks, throughout World War Two. Prior to the outbreak of war the King's Depot was based at Seaforth, but in view of the need for much more accommodation and an expanded military training area, a new barracks was rapidly constructed as a 'hutted camp' in 1940 on open farm land, some farmed by John Brooks of Larkhill Farm, between Formby village and the coast (in the area where Harington Road is today).

This became the King's Regiment Infantry Training Centre and continued in the early part of the war to receive 200 recruits every fortnight. The War Office originally planned to take over Formby Golf Club which was in fact used as officer's accommodation for a period, but in the end the new purpose-built barracks was built with vehicular access from Victoria Road and pedestrian access via Blundell Path. This path, which still survives today was the shortest route to the nearest rail station.

The barracks was named after the former Colonel in Chief, General Sir Charles Harington, GCB, GYIE, DSO who died in 1940. From 1941 to 1945 the Commanding Officer was Lieutenant-Colonel Burke Gaffney MC, who soon established a good relationship with the local residents. He later wrote the official history of the modern regiment, 'The Story of the King's Regiment (Liverpool) 1914-1948'.

Training took place in large gyms, on a large parade ground and on the surrounding open fields. There were football pitches and an athletic ground on the west side of Larkhill Lane (where the National Trust heath reserve is today). Rifle training began using .22 Rifles in a covered range situated near where St. Jerome's Church is today. Following this, further practice took place on the open range at the seaward end of Albert Road; followed by practice at the Altcar Rifle Range, then reached by a track across Marsh Farm from Range Lane.

A short black and white sound film exists produced by the Army Kinema Corporation, this is of the Queen Mother's visit to the barracks in 1954 to review and present the new colours to the 1st Battalion of the Manchester Regiment who were by then in residence. The Formby Civic Society also have a number of photographs of this visit.

Many thanks to Val Gornell for sending me this short article on the history of Harington Barracks.

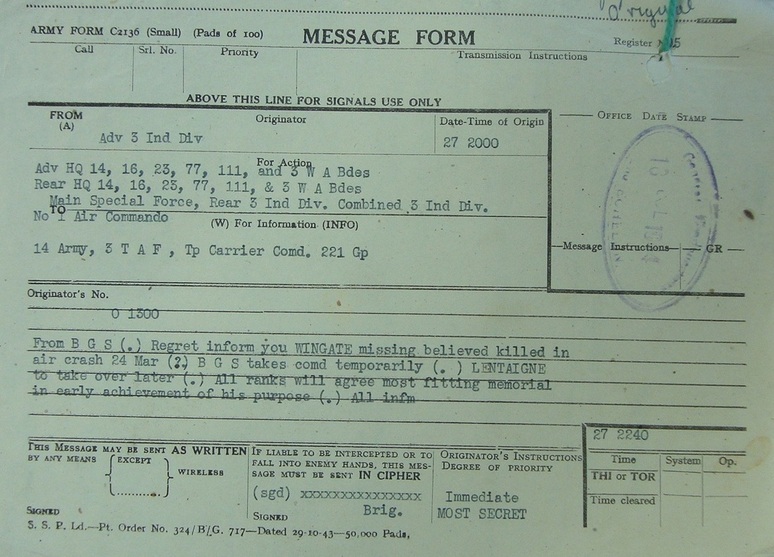

Memorials to General Orde Wingate

On 24th March 1944 General Wingate flew into Broadway (the Chindit constructed airfield used to land the invasion force during Operation Thursday) in a B-25 Mitchell Bomber from 1st Air Commandos. From there he visited the White City and Aberdeen Strongholds. After returning to Broadway he flew on to Imphal to meet Air Marshall Baldwin and from there he set off back to Lalaghat air base. Wingate's plane crashed on the return journey in the hills above Bishenpur near the village of Thiulon. All on board were killed including his Adjutant George Borrow and a number of newspaper war correspondents. The exact cause of the accident is not known. There were reports of isolated storms in the area and also that the one of the B-25's engines was not developing full power.

On the 30th March 1944, after several previous communications in relation to the tragic loss of General Wingate, the following telegram was sent to Admiral Mountbatten from the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill:

I am deeply grieved at the loss of this man of genius, who might have been a man of destiny and send you my heart-felt sympathy. I have consulted my Chiefs of Staff about your deception plan. They share my doubts whether it would be effective and my feeling is that it would lead to unnecessary and undesirable complications. You should therefore drop the idea and report Wingate as killed on Saturday April 1st, as you first proposed. Mrs. Wingate has now been informed that an obituary notice will be printed in the Times this Saturday.

NB. The deception plan mentioned in Churchill's memo, was to report that Wingate was only missing and not actually killed. The hope was to keep the Japanese guessing and not give them the definite knowledge that one of their greatest adversaries in the Burma theatre was now dead.

Seen below are some of the places where General Wingate is remembered, but first here is a copy of the telegram sent by the HQ of the 3rd Indian Division to the various Chindit Brigades on the 27th May 1944.

On the 30th March 1944, after several previous communications in relation to the tragic loss of General Wingate, the following telegram was sent to Admiral Mountbatten from the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill:

I am deeply grieved at the loss of this man of genius, who might have been a man of destiny and send you my heart-felt sympathy. I have consulted my Chiefs of Staff about your deception plan. They share my doubts whether it would be effective and my feeling is that it would lead to unnecessary and undesirable complications. You should therefore drop the idea and report Wingate as killed on Saturday April 1st, as you first proposed. Mrs. Wingate has now been informed that an obituary notice will be printed in the Times this Saturday.

NB. The deception plan mentioned in Churchill's memo, was to report that Wingate was only missing and not actually killed. The hope was to keep the Japanese guessing and not give them the definite knowledge that one of their greatest adversaries in the Burma theatre was now dead.

Seen below are some of the places where General Wingate is remembered, but first here is a copy of the telegram sent by the HQ of the 3rd Indian Division to the various Chindit Brigades on the 27th May 1944.

Shown below is a photograph of a unique memorial in honour of the Chindit leaders death, which was located as close as possible to the actual crash site in the hills of Assam. From the Burma Star website: This remarkable memorial is now located at the Officers Club of the Assam Rifles in Shillong. It shows the mechanical remains of the Mitchell Bomber involved, many rumours and stories have developed over the years as to what caused the accident and what was eventually found at the scene, nothing conclusive has ever been released into the public arena.

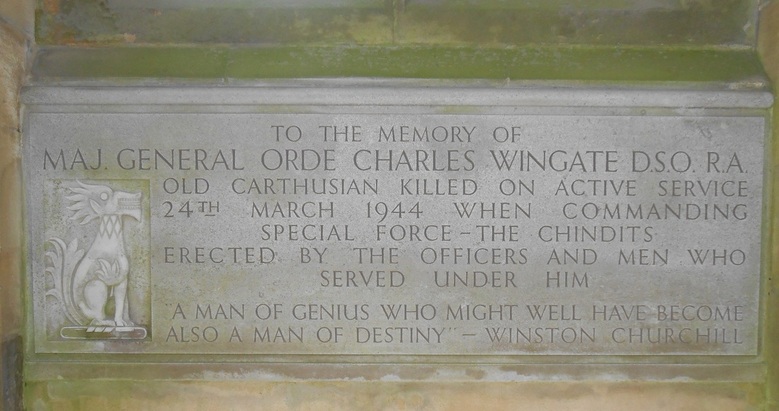

Here are website links concerning two other Wingate Memorials, one at Charterhouse School and the other proposed by Wingate's longtime friend Chaim Weizmann, who became the first President of the State of Israel in 1949. There have been many buildings, institutes and streets named in honour of General Orde Wingate in Israel. (please click on link to open page):

www.scribd.com/document/103257792/Charterhouse-School-The-Heritage-Tour

www.shapell.org/search/?q=wingate

Here is another link to a website which holds film footage of the original memorial service held for General Wingate and the other casualties from the Mitchell Bomber plane crash, the service was held in Manipur, India.

http://www.colonialfilm.org.uk/node/6477

It is well known that General Orde Wingate's official memorial is to be found in the Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, USA. It was here that the unidentified remains of all the casualties were taken and buried after the war was over. By the agreed Allied policy that the majority of those killed in terms of nationality would determine the location of the grave, those lost aboard the Mitchell Bomber were removed from the original gravesite and re-interred at Arlington. This caused a great deal of controversy and consternation at the time, not least amongst the Wingate family themselves. Here is a transcript of a Burma Star magazine article written I think in the 1970's which remarks upon the situation and the Wingate families viewpoint in particular. It comes in the form of a response to whether or not any of General Wingate's remains lie beneath a family grave site in Charlton Cemetery, SE London:

From Judge W. Grant Wingate QC, brother of General Wingate:

"The history of the matter is this. The plane carrying my brother, his ADC Borrow and several Americans crashed on a mountain top in Burma. An expedition was sent out to find the spot at once. They found scattered remains unidentifiable, collected these and buried them upon a mound on which they placed a bronze plate (I have it) engraved with the names of all who perished in the plane. I believe this bronze plate is now held by the Imperial War Museum, click on this link to view: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30081698.

In many ways it would have been fitting to have left this internment undisturbed but in due course the British War Graves authorities removed the remains to Imphal in April 1947. Later (November 1950), without the consent or knowledge of my family the remains were again dug up and removed to Arlington Cemetery, Washington, USA. This was done on agreement between the British and American Courts, that where bodies were buried unidentified in a mass grave, the Americans had the right to re-internment in the United States if there were more Americans than British concerned. Accordingly such remains (and none I repeat were identifiable) of my brother as may have been found and interred with the rest, are now in Arlington Cemetery.

We were represented at the re-internment ceremony at Arlington by a personal friend of mine, who happened to be the First Secretary at the British Embassy in Washington at the time. We had only 24 hours notice of the re-internment ceremony. The manner in which this matter was handled was the subject of a complaint taken up on our behalf by Winston Churchill, but nothing could be done. We felt and and feel that it was quite inappropriate for General Wingate to be buried in the States. Although I don't suppose he would have minded as much as his family.

It follows from what I have said that no remains of my brother are buried in the Charlton Cemetery. This is a memorial inscription only. There is another memorial of a more impressive character in the North Porch of the Charterhouse School Chapel."

The author of this article was Bill Lawrence formerly a member of the Lewisham Branch of the Burma Star Association. Although I do have a photograph of the Wingate family memorial found in Charlton Cemetery I am not going to show it on these pages in respect to the family and their right to privacy.

Below is the memorial stone found at the Arlington Cemetery in Washington DC.

www.scribd.com/document/103257792/Charterhouse-School-The-Heritage-Tour

www.shapell.org/search/?q=wingate

Here is another link to a website which holds film footage of the original memorial service held for General Wingate and the other casualties from the Mitchell Bomber plane crash, the service was held in Manipur, India.

http://www.colonialfilm.org.uk/node/6477

It is well known that General Orde Wingate's official memorial is to be found in the Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, USA. It was here that the unidentified remains of all the casualties were taken and buried after the war was over. By the agreed Allied policy that the majority of those killed in terms of nationality would determine the location of the grave, those lost aboard the Mitchell Bomber were removed from the original gravesite and re-interred at Arlington. This caused a great deal of controversy and consternation at the time, not least amongst the Wingate family themselves. Here is a transcript of a Burma Star magazine article written I think in the 1970's which remarks upon the situation and the Wingate families viewpoint in particular. It comes in the form of a response to whether or not any of General Wingate's remains lie beneath a family grave site in Charlton Cemetery, SE London:

From Judge W. Grant Wingate QC, brother of General Wingate:

"The history of the matter is this. The plane carrying my brother, his ADC Borrow and several Americans crashed on a mountain top in Burma. An expedition was sent out to find the spot at once. They found scattered remains unidentifiable, collected these and buried them upon a mound on which they placed a bronze plate (I have it) engraved with the names of all who perished in the plane. I believe this bronze plate is now held by the Imperial War Museum, click on this link to view: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30081698.

In many ways it would have been fitting to have left this internment undisturbed but in due course the British War Graves authorities removed the remains to Imphal in April 1947. Later (November 1950), without the consent or knowledge of my family the remains were again dug up and removed to Arlington Cemetery, Washington, USA. This was done on agreement between the British and American Courts, that where bodies were buried unidentified in a mass grave, the Americans had the right to re-internment in the United States if there were more Americans than British concerned. Accordingly such remains (and none I repeat were identifiable) of my brother as may have been found and interred with the rest, are now in Arlington Cemetery.

We were represented at the re-internment ceremony at Arlington by a personal friend of mine, who happened to be the First Secretary at the British Embassy in Washington at the time. We had only 24 hours notice of the re-internment ceremony. The manner in which this matter was handled was the subject of a complaint taken up on our behalf by Winston Churchill, but nothing could be done. We felt and and feel that it was quite inappropriate for General Wingate to be buried in the States. Although I don't suppose he would have minded as much as his family.

It follows from what I have said that no remains of my brother are buried in the Charlton Cemetery. This is a memorial inscription only. There is another memorial of a more impressive character in the North Porch of the Charterhouse School Chapel."

The author of this article was Bill Lawrence formerly a member of the Lewisham Branch of the Burma Star Association. Although I do have a photograph of the Wingate family memorial found in Charlton Cemetery I am not going to show it on these pages in respect to the family and their right to privacy.

Below is the memorial stone found at the Arlington Cemetery in Washington DC.

The placing of pebbles on top of gravestones or other memorials is a long standing Jewish tradition probably dating back to Old Testament times. Today it is meant as a way of honouring the deceased person's memory with a visit to their resting place and acts as a 'calling card' on behalf of the visitor. Before the advent of inscribed stone memorials Jewish families would build up the ground covering a recently deceased relative with rocks and stones, it is thought that the more stones covering the grave signified the prominence of the deceased.

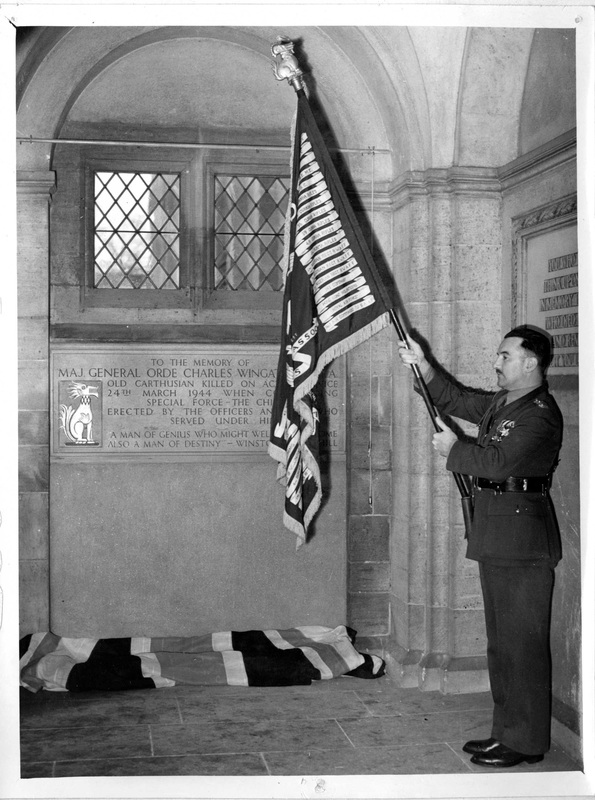

Below are two more images showing the Wingate Memorial at Charterhouse School in Godalming, Surrey. These were sent to me courtesy of Catherine Smith the School Archivist and the Reverend Clive Case, the School's Senior Chaplain. My thanks and appreciation go to both the afore-mentioned and of course the school itself. The Standard Bearer depicted in the photograph below is said to be Captain Harold Blackburne, formerly an officer with 7 Column on Operation Longcloth.

Update 31st March 2018

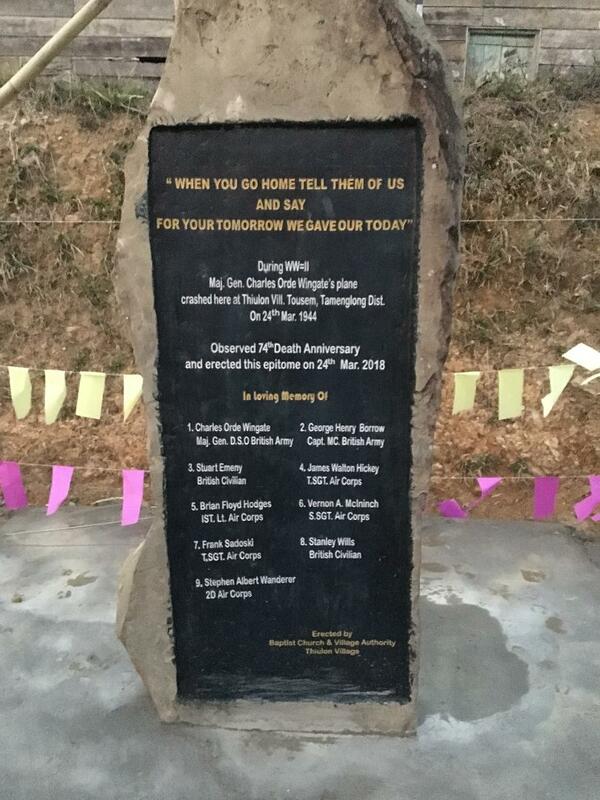

A commemoration and wreath laying ceremony was performed at the plane crash site of General Orde Charles Wingate on 10th February 2018. The site is located near the village of Thiulon in the Tamenglong District of Manipur State, India. The crash site is around 1.5km from the south western perimeter of the village. The coordinates measured by GPS were N 24*59’17”and E 93*23’27”. The elevation read 740 meters above sea level.

The ceremony was conducted and arranged by WW2 battlefield researcher, Yumnam Rajeshwor Singh with assistance from his many associates and the Headman from the village Thiulon. The journey to the crash site began on the 9th February and involved travelling through some extremely testing terrain. Rajeshwor had always been keen and interested to make the pilgrimage to Thiulon and now his chance had come. After passing through Tamenglong, the road deteriorates badly and vehicles cannot go beyond a speed of 20km per hour. From the town the road immediately bends like a snake on a steep downward gradient towards the Barak River. A new hanging bridge on the Barak River had recently been built, with the old broken bridge lying next to it in the river.

Raj and his party reached Thiulon later on the 9th February and were greeted by the village elders at the church. After enjoying a meal prepared by the villagers, the explorers bedded down for the night in the Church Office. The next morning, Raj was taken around the village and shown what seemed to be various pieces of plane debris from the Mitchell Bomber. These included part of a radial engine and some landing gear apparatus.

The villagers then told the story of the 24th March 1944, as passed down from one generation to the next. They explained that were having their evening prayer when they saw a ball of fire coming down from the sky. A plane had caught fire and was falling down onto the western slopes of the mountain, some 2km from the village. Just after the crash, loud explosions were heard by the villagers and pebbles and debris from the explosion rattled down on the village houses. They also remembered that several soldiers made the trip to the crash site over the coming weeks to investigate what had happened and to remove items from the scene.

Thanks to Raj’s efforts and visit to the crash site, the villagers of Thiulon have agreed and wish to commemorate the anniversary of General Charles Orde Wingate’s death, alongside the other eight casualties on the 24th March each year. A full report of this pilgrimage, together with some excellent photographs can be seen on the Chindit Society pages, here: The Chindit Society

Update 31st March 2019

After his first visit to Thiulon last year, Raj returned to the village once more on the 24th March 2019. During this second visit he joined with the local villagers in commemorating the 75th Anniversary of Orde Wingate's death, including the unveiling of a permanent memorial stone at the crash location. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

A commemoration and wreath laying ceremony was performed at the plane crash site of General Orde Charles Wingate on 10th February 2018. The site is located near the village of Thiulon in the Tamenglong District of Manipur State, India. The crash site is around 1.5km from the south western perimeter of the village. The coordinates measured by GPS were N 24*59’17”and E 93*23’27”. The elevation read 740 meters above sea level.

The ceremony was conducted and arranged by WW2 battlefield researcher, Yumnam Rajeshwor Singh with assistance from his many associates and the Headman from the village Thiulon. The journey to the crash site began on the 9th February and involved travelling through some extremely testing terrain. Rajeshwor had always been keen and interested to make the pilgrimage to Thiulon and now his chance had come. After passing through Tamenglong, the road deteriorates badly and vehicles cannot go beyond a speed of 20km per hour. From the town the road immediately bends like a snake on a steep downward gradient towards the Barak River. A new hanging bridge on the Barak River had recently been built, with the old broken bridge lying next to it in the river.

Raj and his party reached Thiulon later on the 9th February and were greeted by the village elders at the church. After enjoying a meal prepared by the villagers, the explorers bedded down for the night in the Church Office. The next morning, Raj was taken around the village and shown what seemed to be various pieces of plane debris from the Mitchell Bomber. These included part of a radial engine and some landing gear apparatus.

The villagers then told the story of the 24th March 1944, as passed down from one generation to the next. They explained that were having their evening prayer when they saw a ball of fire coming down from the sky. A plane had caught fire and was falling down onto the western slopes of the mountain, some 2km from the village. Just after the crash, loud explosions were heard by the villagers and pebbles and debris from the explosion rattled down on the village houses. They also remembered that several soldiers made the trip to the crash site over the coming weeks to investigate what had happened and to remove items from the scene.

Thanks to Raj’s efforts and visit to the crash site, the villagers of Thiulon have agreed and wish to commemorate the anniversary of General Charles Orde Wingate’s death, alongside the other eight casualties on the 24th March each year. A full report of this pilgrimage, together with some excellent photographs can be seen on the Chindit Society pages, here: The Chindit Society

Update 31st March 2019

After his first visit to Thiulon last year, Raj returned to the village once more on the 24th March 2019. During this second visit he joined with the local villagers in commemorating the 75th Anniversary of Orde Wingate's death, including the unveiling of a permanent memorial stone at the crash location. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Taukkyan War Cemetery and the Rangoon Memorial

After the war was over the Imperial War Graves Commission set up Taukkyan War Cemetery as the main location for the commemoration of the casualties from the Burma campaign. It is here that the vast majority of Chindits either lie or are remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial. This memorial is the centre piece structure of the entire cemetery grounds and contains the names of some 27,000 casualties from the campaign who have 'no known grave'.

The Chindits of Operation Longcloth mainly occupy face panels 3, 4, 5, 6, 57 and 58 of the Rangoon Memorial, but can also be found upon other panels and for some even beneath individual grave plots. Here is the history of the cemetery:

Taukkyan War Cemetery is in Taukkyan town in the township of Mingaladon, Rangoon greater area, on the main highway No.1 Pyay (formerly Prome) Road. From the centre of the city of Rangoon, it is 21 miles north, 45 minutes drive from the centre of Rangoon and 24 minutes from the International airport. Exact location of the cemetery is North (17º02'08.24") and East (96º07'55.28").

Taukkyan War Cemetery is the largest of the three war cemeteries in Burma (now Myanmar). It was begun in 1951 for the reception of graves from four battlefield cemeteries at Akyab, Mandalay, Meiktila and Sahmaw which were difficult to access and could not be maintained. The last was an original 'Chindit' cemetery containing many of those who died in the battle for Myitkyina and other battle sites in 1944. The graves have been grouped together at Taukkyan to preserve the individuality of these battlefield cemeteries

Burials were also transferred from civil and cantonment cemeteries, and from a number of isolated jungle and roadside sites. Because of prolonged post-war unrest, considerable delay occurred before the Army Graves Service were able to complete their work, and in the meantime many such graves had disappeared. However, when the task was resumed, several hundred more graves were retrieved from scattered positions throughout the country and brought together here.

The cemetery now contains 6,374 Commonwealth burials of the Second World War, 867 of them unidentified.

In the 1950's, the graves of 52 Commonwealth servicemen of the First World War were brought into the cemetery from the following cemeteries where permanent maintenance was not possible: Henzada, Meiktila Cantonment, Thayetmyo New, Thamakan, Mandalay Military and Maymyo Cantonment.

Taukkyan War Cemetery also contains:

The Rangoon Memorial, which bears the names of almost 27,000 men of the Commonwealth land forces who died during the campaigns in Burma and who have no known grave.

The Taukkyan Cremation Memorial, commemorating more than 1,000 Second World War casualties whose remains were cremated in accordance with their faith, and the Taukkyan Memorial, which commemorates 45 servicemen of both wars who died and were buried elsewhere in Burma but whose graves could not be maintained. For more general information about Taukkyan, please visit the CWGC website using the link below:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/92002/TAUKKYAN%20WAR%20CEMETERY

The Chindits of Operation Longcloth mainly occupy face panels 3, 4, 5, 6, 57 and 58 of the Rangoon Memorial, but can also be found upon other panels and for some even beneath individual grave plots. Here is the history of the cemetery:

Taukkyan War Cemetery is in Taukkyan town in the township of Mingaladon, Rangoon greater area, on the main highway No.1 Pyay (formerly Prome) Road. From the centre of the city of Rangoon, it is 21 miles north, 45 minutes drive from the centre of Rangoon and 24 minutes from the International airport. Exact location of the cemetery is North (17º02'08.24") and East (96º07'55.28").

Taukkyan War Cemetery is the largest of the three war cemeteries in Burma (now Myanmar). It was begun in 1951 for the reception of graves from four battlefield cemeteries at Akyab, Mandalay, Meiktila and Sahmaw which were difficult to access and could not be maintained. The last was an original 'Chindit' cemetery containing many of those who died in the battle for Myitkyina and other battle sites in 1944. The graves have been grouped together at Taukkyan to preserve the individuality of these battlefield cemeteries

Burials were also transferred from civil and cantonment cemeteries, and from a number of isolated jungle and roadside sites. Because of prolonged post-war unrest, considerable delay occurred before the Army Graves Service were able to complete their work, and in the meantime many such graves had disappeared. However, when the task was resumed, several hundred more graves were retrieved from scattered positions throughout the country and brought together here.

The cemetery now contains 6,374 Commonwealth burials of the Second World War, 867 of them unidentified.

In the 1950's, the graves of 52 Commonwealth servicemen of the First World War were brought into the cemetery from the following cemeteries where permanent maintenance was not possible: Henzada, Meiktila Cantonment, Thayetmyo New, Thamakan, Mandalay Military and Maymyo Cantonment.

Taukkyan War Cemetery also contains:

The Rangoon Memorial, which bears the names of almost 27,000 men of the Commonwealth land forces who died during the campaigns in Burma and who have no known grave.

The Taukkyan Cremation Memorial, commemorating more than 1,000 Second World War casualties whose remains were cremated in accordance with their faith, and the Taukkyan Memorial, which commemorates 45 servicemen of both wars who died and were buried elsewhere in Burma but whose graves could not be maintained. For more general information about Taukkyan, please visit the CWGC website using the link below:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/92002/TAUKKYAN%20WAR%20CEMETERY

I visited Taukkyan in March 2008, this is how I described that day in my Burma diary as written during trip:

"The day of the cemetery visits had arrived. Everyone rose early so we could get on the road to Taukkyan Cemetery as soon as breakfast was over. The earlier start meant that the cool of the morning still remained as we boarded the coach. I remember that coolness well as we passed through the streets of Rangoon, and then out into it's suburbs. I was extremely emotional from the outset that day, and kept on thinking how Nan would have felt those 20 years previous, when she too had visited the cemetery.

The strange mix of emotions aboard the coach was apparent as little was spoken between the group on the journey to Taukkyan. All of us I guess had an internal battle with our feelings that day. As I stepped down off the coach at Taukkyan Cemetery I was totally overwhelmed by the way the strong morning sunlight caught the shape of the Rangoon Memorial, it was an awesome image, but brought home straight away the immense melancholy of the site as one reflected on it's significance and meaning. The cemetery was atmospheric, almost in an overpowering way.

Straight away you are impressed by the cemetery's stature and are stunned by the heat, sounds and all your eyes can take in across the beautifully kept grounds. I am really struggling to come to terms with how I felt walking amongst those soldiers spirits, especially those upon the Rangoon Memorial. Here are written the names of the men who have no known grave. On faces 3, 4, 5 and 6 were many names I had read about, whose exploits I have digested and put to memory. Now I stood before them, it was an incredible sensation and I found myself in tears.

After taking part in a short commemorative service, we all took the time to pay our respects to the men we had come such a long way to honour. We also met the cemetery curator. Oscar was a wonderfully exuberant man, who clearly loves his job. He was only too glad to answer our questions, and gave a good account of how the cemeteries are financed, organised and then cared for by himself and his staff. He told me that the men buried at Rangoon War Cemetery were all originally found and exhumed from their previous resting places within the city limits of Rangoon. This was one of the few facts that I learned on the trip pertaining to my grandfather. This statement was seconded when we reached Rangoon War Cemetery, by the Head Groundsman there, Mohan Segran.

Taukkyan War Cemetery is a beautiful dedication to the men who perished in Burma, it was a humbling experience to be amongst their memory."

As mentioned earlier the Rangoon Memorial has recorded upon it the names of those who cannot be identified as having a known place or site of burial. Many of these casualties would have been 'buried' by their comrades in the best way as was possible at the time. Some were lost on jungle paths and tracks, others were drowned in the great rivers of Burma during the three long years of conflict. Even after the war had ended, and sometimes with good information to hand it proved impossible to relocate these burial sites as the jungle speedily reclaimed the areas involved.

On the monument itself the men are recorded alphabetically by regiment and cover as many of the stone faces as is necessary to recount the numbers lost. The 13th Battalion, King's Liverpool are to be found mostly on Faces 5 and 6, the Burma Rifles on Faces 3 and 4, with the 3/2 Gurkhas occupying Faces 57 and 58. I have decided not to show any individual grave or panel face here, as there are many examples of both types of memorial shown throughout the other pages of this website.

To learn more about the Rangoon Memorial, please follow this link to the CWGC website:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/100/Rangoon%20Memorial

On the monument itself the men are recorded alphabetically by regiment and cover as many of the stone faces as is necessary to recount the numbers lost. The 13th Battalion, King's Liverpool are to be found mostly on Faces 5 and 6, the Burma Rifles on Faces 3 and 4, with the 3/2 Gurkhas occupying Faces 57 and 58. I have decided not to show any individual grave or panel face here, as there are many examples of both types of memorial shown throughout the other pages of this website.

To learn more about the Rangoon Memorial, please follow this link to the CWGC website:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/100/Rangoon%20Memorial

For further information about the Rangoon Memorial, it's history and the dedication ceremony held in February 1958, please follow the link to the excellent King's Own Royal Regiment Museum website here: www.kingsownmuseum.com/gallerywarmemorials002.htm

There is a website devoted to the memory of a Chindit casualty from the second expedition in 1944, Operation Thursday. Private David Bennett Jones was with the 1st Battalion South Staffordshires in 1944 fighting under Brigadier Mike Calvert in the jungles of Burma. He was killed and is remembered on the Rangoon Memorial, here is a link to the website showing the documents sent to the family in regard to his death and to his name being placed upon the memorial.

The papers concerning the Rangoon Memorial have unique informational value, as I have not come across examples of these anywhere else before. http://www.lindahome.co.uk/page68.html

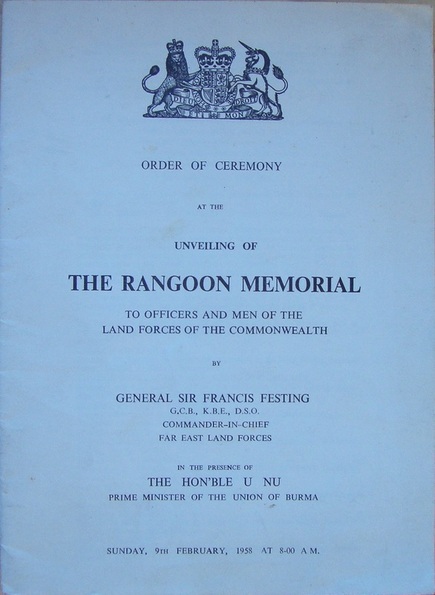

The final image below is the front cover of the Order of Service program for the unveiling ceremony mentioned above.

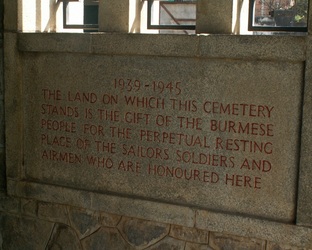

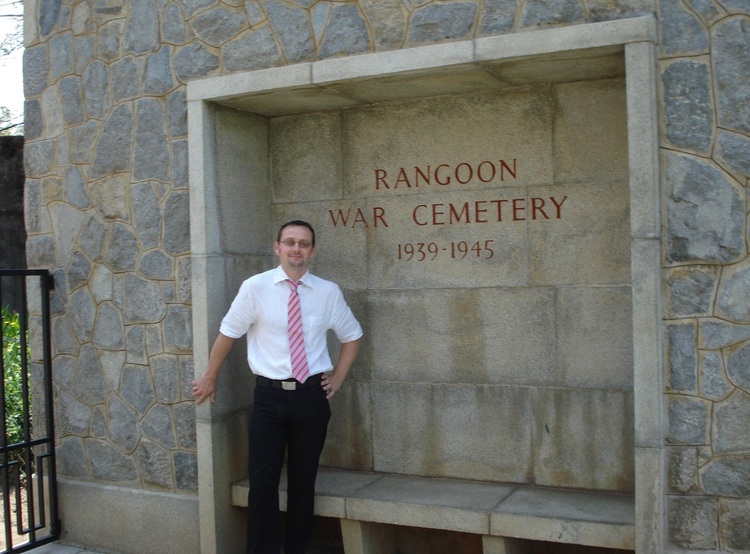

Rangoon War Cemetery

From a Chindit perspective Rangoon War Cemetery plays an important part in the story of the men who became prisoners of war in 1943 and 1944. Of the 230 plus men from Operation Longcloth who became POW's, 138 of them would eventually be buried in Rangoon War Cemetery, the numbers for 1944 make for better reading, with only a handful of men perishing in Rangoon Jail from the 35 captured. Most of these were men from the 1st Battalion, King's Liverpool Regiment whose gliders had crash landed in the jungle, having failed to reach the Chindit landing area nicknamed 'Broadway' in March 1944.

Here are some details about the cemetery:

Rangoon War Cemetery was first used as a burial ground immediately following the recapture of Rangoon in May 1945. Later, the Army Graves Service moved in graves from several burial sites in and around Rangoon, including those of the men who died in Rangoon Jail as prisoners of war.

There are now 1,381 Commonwealth servicemen of the Second World War buried or commemorated in this cemetery. Eighty-six of the burials are unidentified and there are special memorials to more than sixty casualties whose graves could not be precisely located. These graves have the words 'buried near this spot' written on the memorial plaques, one of which belongs to my grandfather.

In 1948, the graves of thirty-six Commonwealth servicemen who died in Rangoon during the First World War were moved into this cemetery, thirty-five of them from Rangoon Cantonment Cemetery and one from Rangoon (Pazundaung) Town Cemetery.

The entrance to the cemetery is in a lane facing east along PYI Road (formerly Prome Road) some 8 kilometres from the port, 12 kilometres from the airport and 5 kilometres from the main railway station. Monasteries surround the cemetery on three sides. The cemetery is tended by locally engaged staff and a Caretaker resides on site. The cemetery gates are open between 8 am and 5 pm.

Here is a link to the CWGC website showing details for Rangoon War Cemetery:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/92001/RANGOON%20WAR%20CEMETERY

The photographs below were taken in 2010 and where sent to me care of Tony B. nt872b(at)hotmail.com

Please click on any photograph to enlarge.

Here are some details about the cemetery:

Rangoon War Cemetery was first used as a burial ground immediately following the recapture of Rangoon in May 1945. Later, the Army Graves Service moved in graves from several burial sites in and around Rangoon, including those of the men who died in Rangoon Jail as prisoners of war.

There are now 1,381 Commonwealth servicemen of the Second World War buried or commemorated in this cemetery. Eighty-six of the burials are unidentified and there are special memorials to more than sixty casualties whose graves could not be precisely located. These graves have the words 'buried near this spot' written on the memorial plaques, one of which belongs to my grandfather.

In 1948, the graves of thirty-six Commonwealth servicemen who died in Rangoon during the First World War were moved into this cemetery, thirty-five of them from Rangoon Cantonment Cemetery and one from Rangoon (Pazundaung) Town Cemetery.

The entrance to the cemetery is in a lane facing east along PYI Road (formerly Prome Road) some 8 kilometres from the port, 12 kilometres from the airport and 5 kilometres from the main railway station. Monasteries surround the cemetery on three sides. The cemetery is tended by locally engaged staff and a Caretaker resides on site. The cemetery gates are open between 8 am and 5 pm.

Here is a link to the CWGC website showing details for Rangoon War Cemetery:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-a-cemetery/cemetery/92001/RANGOON%20WAR%20CEMETERY

The photographs below were taken in 2010 and where sent to me care of Tony B. nt872b(at)hotmail.com

Please click on any photograph to enlarge.

As you can imagine the memories I have of my families visit to Rangoon War Cemetery will always remain with me. It is a place of serene calmness, but of course is inevitably etched with sadness and sacrifice. Here is another extract from my Burma diary, which may go some way to help describe those emotions and recollections from March 6th 2008:

"We boarded the coach once more and headed back into Rangoon to visit Rangoon War Cemetery. This was situated within the city itself, and located down a small unassuming track road, which you would doubt led to anywhere of interest. As we approached the entrance a man appeared, greeting us gently as he opened simple black gates to the cemetery. This was Mohan Segran the caretaker at Rangoon War Cemetery. The grounds were beautifully arranged, laid out with pride in an area no bigger than a large football pitch. The size of the cemetery was I think a shock to my family, as we had all individually pictured the cemetery as being much bigger. We all made our way to the stark white Stone of Remembrance, which threw an unbelievable glare against the lush green vegetation around it. We stood in silence as the second service of the day began."

"That day was a great experience for us all, not just for visiting the last resting place of our father or grandfather for the first time, or from being somewhere our mother and Nan had been before us. But for the way it brought all of us together to feel common emotions and to share in something we had all considered separately at various times in our lives.

One by one each of us spoke with our kin, I know that for me it was an opportunity to speak to a man about his beautiful and courageous wife. My obsession with finding out more about my grandfather is a way for me to stay with my Nan and her memory, more than to seek out her husband and his story. I know that he knows this and that he understands.

I found out that day that the soldier who shares Granddad's plot of 9.B.2, Private Phillip Hose, does have a connection more than purely alphabetical to my Granddad. It seems that when the two men were relocated to Rangoon War Cemetery their remains were previously buried so close together that neither could be identified as one or the other. This tells me that the two have laid beside each other from their initial burial to their final resting place at Rangoon.

Denis Gudgeon (both a Longcloth Chindit and Rangoon Jail survivor) mentioned on the tour about how they buried the bodies of the soldiers outside the jail, on a piece of ground that was next door to Rangoon Zoo. I wonder now if that could have been Granddad's first resting place, before being relocated to Rangoon War Cemetery."

Of course all my research since 2008 has uncovered most of what happened to my grandfather and many of his fellow Chindits from 1943. At the time of my visit to Burma I knew very little of these facts and was working mostly on supposition and guess work. As it turned out nearly all of the hunches turned out to be correct.

Below are some examples of the memorial grave plaques found at Rangoon War Cemetery. I have chosen men at random, apart from my Grandfather's and another member from Column 5, Lance-Corporal George Lee. George was the Cipher Clerk in Fergusson's Head Quarters group and had been lost from the line of march after he had attempted to rescue some equipment which had fallen into a ravine. George's son Arthur was another of the people on our tour and it was wonderful to have another Column 5 family member with us.

"We boarded the coach once more and headed back into Rangoon to visit Rangoon War Cemetery. This was situated within the city itself, and located down a small unassuming track road, which you would doubt led to anywhere of interest. As we approached the entrance a man appeared, greeting us gently as he opened simple black gates to the cemetery. This was Mohan Segran the caretaker at Rangoon War Cemetery. The grounds were beautifully arranged, laid out with pride in an area no bigger than a large football pitch. The size of the cemetery was I think a shock to my family, as we had all individually pictured the cemetery as being much bigger. We all made our way to the stark white Stone of Remembrance, which threw an unbelievable glare against the lush green vegetation around it. We stood in silence as the second service of the day began."

"That day was a great experience for us all, not just for visiting the last resting place of our father or grandfather for the first time, or from being somewhere our mother and Nan had been before us. But for the way it brought all of us together to feel common emotions and to share in something we had all considered separately at various times in our lives.

One by one each of us spoke with our kin, I know that for me it was an opportunity to speak to a man about his beautiful and courageous wife. My obsession with finding out more about my grandfather is a way for me to stay with my Nan and her memory, more than to seek out her husband and his story. I know that he knows this and that he understands.

I found out that day that the soldier who shares Granddad's plot of 9.B.2, Private Phillip Hose, does have a connection more than purely alphabetical to my Granddad. It seems that when the two men were relocated to Rangoon War Cemetery their remains were previously buried so close together that neither could be identified as one or the other. This tells me that the two have laid beside each other from their initial burial to their final resting place at Rangoon.

Denis Gudgeon (both a Longcloth Chindit and Rangoon Jail survivor) mentioned on the tour about how they buried the bodies of the soldiers outside the jail, on a piece of ground that was next door to Rangoon Zoo. I wonder now if that could have been Granddad's first resting place, before being relocated to Rangoon War Cemetery."

Of course all my research since 2008 has uncovered most of what happened to my grandfather and many of his fellow Chindits from 1943. At the time of my visit to Burma I knew very little of these facts and was working mostly on supposition and guess work. As it turned out nearly all of the hunches turned out to be correct.

Below are some examples of the memorial grave plaques found at Rangoon War Cemetery. I have chosen men at random, apart from my Grandfather's and another member from Column 5, Lance-Corporal George Lee. George was the Cipher Clerk in Fergusson's Head Quarters group and had been lost from the line of march after he had attempted to rescue some equipment which had fallen into a ravine. George's son Arthur was another of the people on our tour and it was wonderful to have another Column 5 family member with us.

Not long after our visit to Burma in 2008 the country was hit by the tropical cyclone named Nargis. Much devastation was caused by the storm across a large area of the country. Having been in the Burma just 8 weeks prior to the storm obviously all our thoughts turned toward the people we had met and the places we had visited. Fortunately Rangoon and most of the major cities were spared the full wrath of cyclone 'Nargis', but there was considerable damage done to the outer suburbs and villages of the area. This is how Mohan Segran, the caretaker from Rangoon War Cemetery described the storm and the consequences for his grounds and team:

Dear Steven,

Thank you so much for your mail sent on 9 May 2008. Due to no electricity and phone line out of order, I could no reply to you immediately. All the staffs at three cemeteries in Myanmar are all safe from cyclone Nargis. We had some big trees at the cemetery were up-rooted and some damages occurred to staff quarters where we will need rebuild etc. I am very pleased and glad to note that you appreciated our work and your message was passed on to my team mates at Rangoon War Cemetery. There was little damage to any of the memorials or graves, so you must not worry here.

Best Regards,

Mohan.

Although Rangoon War Cemetery is an emotional place to visit (as are all such places, across sadly, all our continents) it does provide a positive experience as well as the obvious feelings of sadness and reflection. We went back to Rangoon War Cemetery on the last day of our trip and on that day were able to absorb more of the cemetery's atmosphere. The heat was more apparent on the second visit and the noise made by the community living around the perimeter of the grounds. The continual shriek of one specie of bird was an ever present and the low hum of insects provided a never ending backing track to the day. These noises were not taken in on the previous visit. The central monuments present in all CWGC cemeteries throughout the world, the Cross of Sacrifice and the Stone of Remembrance seemed so starkly white against the lush green tropical grasses that surrounded them and occasionally a warm breeze would rustle through the low growing evergreen bushes dotted here and there.

Rangoon War Cemetery is a beautiful place to spend time in and now holds an important place in our hearts, for here we shared some very special moments.

Below are some more photos from the visit to Rangoon War Cemetery, including me spending time to walk amongst the men of the 13th King's, but also showing the Cross of Sacrifice and Stone of Remembrance. My Mum, sister and myself just before we left the cemetery on our first visit and my brother Marc standing alongside the cemetery inscription near the front gates. Please click on image to bring it forward.

Dear Steven,

Thank you so much for your mail sent on 9 May 2008. Due to no electricity and phone line out of order, I could no reply to you immediately. All the staffs at three cemeteries in Myanmar are all safe from cyclone Nargis. We had some big trees at the cemetery were up-rooted and some damages occurred to staff quarters where we will need rebuild etc. I am very pleased and glad to note that you appreciated our work and your message was passed on to my team mates at Rangoon War Cemetery. There was little damage to any of the memorials or graves, so you must not worry here.

Best Regards,

Mohan.

Although Rangoon War Cemetery is an emotional place to visit (as are all such places, across sadly, all our continents) it does provide a positive experience as well as the obvious feelings of sadness and reflection. We went back to Rangoon War Cemetery on the last day of our trip and on that day were able to absorb more of the cemetery's atmosphere. The heat was more apparent on the second visit and the noise made by the community living around the perimeter of the grounds. The continual shriek of one specie of bird was an ever present and the low hum of insects provided a never ending backing track to the day. These noises were not taken in on the previous visit. The central monuments present in all CWGC cemeteries throughout the world, the Cross of Sacrifice and the Stone of Remembrance seemed so starkly white against the lush green tropical grasses that surrounded them and occasionally a warm breeze would rustle through the low growing evergreen bushes dotted here and there.

Rangoon War Cemetery is a beautiful place to spend time in and now holds an important place in our hearts, for here we shared some very special moments.

Below are some more photos from the visit to Rangoon War Cemetery, including me spending time to walk amongst the men of the 13th King's, but also showing the Cross of Sacrifice and Stone of Remembrance. My Mum, sister and myself just before we left the cemetery on our first visit and my brother Marc standing alongside the cemetery inscription near the front gates. Please click on image to bring it forward.

Update 08/02/2013.

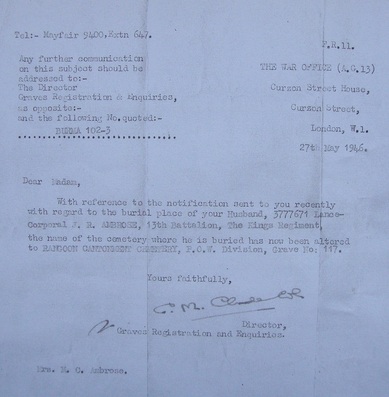

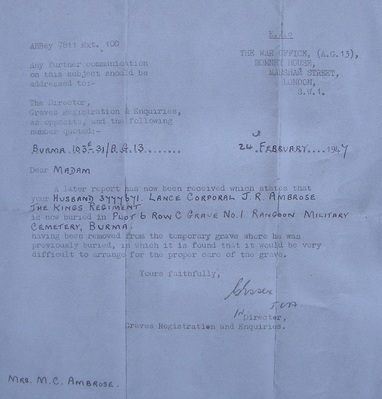

I recently received some new photographs and papers in regard to Lance Corporal James Ambrose. James was a member of the final dispersal party of six men mostly from Column 5 and which included my own grandfather, who all became POW's whilst trying to reach the Chinese borders in May 1943. Amongst these documents were a number of official Army notices to his family concerning his final resting place. Firstly and shown below to the left, is the clarification that his intital burial took place at Rangoon Cantonment Cemetery and that his grave number was 117. This information matches up to the record of POW Deaths in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail which can be found in the Imperial War Museum, London. The family received this notification from the Imperial Graves Registration Unit on 27th May 1946.

The other document, shown to the right, informs the family that James's body had been removed from the Cantonment Cemetery and re-interred at the newly built Rangoon War Cemetery, which is where he lies today. The second letter was received on the 24th February 1947. These two documents have proved invaluable to my research, as they prove beyond doubt that the men of Rangoon Jail were buried intitally in the Cantonment Cemetery and it was only well after the war was over that the Imperial Graves Commission moved them over to Rangoon War Cemetery. The information provided by these letters is all the more priceless to me, as they give me an idea of the correspondence my Nan would have received from the War Office back in the late 1940's.

My thanks as always goes to Val Gornell, the daughter of James Ambrose, for sending me this information and for allowing me to use it on this website. To read more about Lance Corporal James Ambrose, please click here, his story is the second on the page: Family 2

I recently received some new photographs and papers in regard to Lance Corporal James Ambrose. James was a member of the final dispersal party of six men mostly from Column 5 and which included my own grandfather, who all became POW's whilst trying to reach the Chinese borders in May 1943. Amongst these documents were a number of official Army notices to his family concerning his final resting place. Firstly and shown below to the left, is the clarification that his intital burial took place at Rangoon Cantonment Cemetery and that his grave number was 117. This information matches up to the record of POW Deaths in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail which can be found in the Imperial War Museum, London. The family received this notification from the Imperial Graves Registration Unit on 27th May 1946.

The other document, shown to the right, informs the family that James's body had been removed from the Cantonment Cemetery and re-interred at the newly built Rangoon War Cemetery, which is where he lies today. The second letter was received on the 24th February 1947. These two documents have proved invaluable to my research, as they prove beyond doubt that the men of Rangoon Jail were buried intitally in the Cantonment Cemetery and it was only well after the war was over that the Imperial Graves Commission moved them over to Rangoon War Cemetery. The information provided by these letters is all the more priceless to me, as they give me an idea of the correspondence my Nan would have received from the War Office back in the late 1940's.

My thanks as always goes to Val Gornell, the daughter of James Ambrose, for sending me this information and for allowing me to use it on this website. To read more about Lance Corporal James Ambrose, please click here, his story is the second on the page: Family 2

Update 30/04/2014.

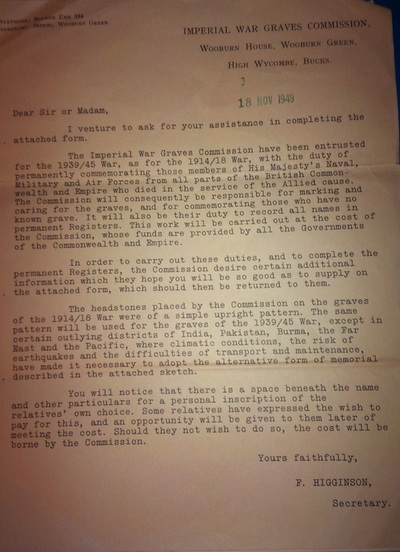

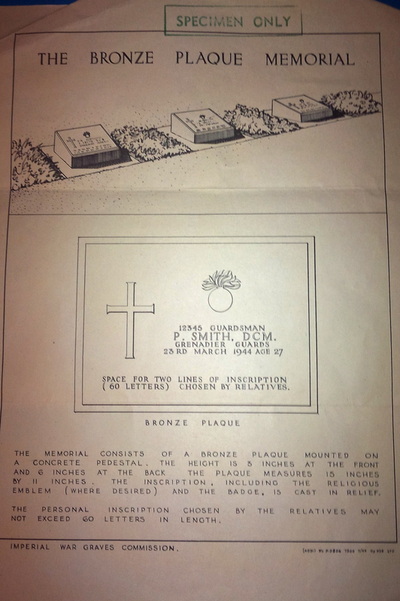

Below are two interesting notifications sent out by the Imperial War Graves Commission to families of WW2 casualties lost in the Far East theatre. These documents were sent to me by the family of Pte. George Sullivan, a member of Column 8 in 1943, George had survived the westward journey back to India, but sadly died in Kohima Hospital suffering from exhaustion and kidney failure.

My presumption is that these papers were sent to all families who suffered a similar bereavement to the Sullivan's, although I have never come across them before in my research. They explain the reasons for choosing the different style of commemorative stone found in Commonwealth Cemeteries across SE Asia and then how the family could contribute to the memorial with a personal epitaph. Please click on each image to bring them forward on the screen.

Below are two interesting notifications sent out by the Imperial War Graves Commission to families of WW2 casualties lost in the Far East theatre. These documents were sent to me by the family of Pte. George Sullivan, a member of Column 8 in 1943, George had survived the westward journey back to India, but sadly died in Kohima Hospital suffering from exhaustion and kidney failure.

My presumption is that these papers were sent to all families who suffered a similar bereavement to the Sullivan's, although I have never come across them before in my research. They explain the reasons for choosing the different style of commemorative stone found in Commonwealth Cemeteries across SE Asia and then how the family could contribute to the memorial with a personal epitaph. Please click on each image to bring them forward on the screen.

Update 23/08/2015.

From new information released by the CWGC on the 70th Anniversary of VJ Day, it has now come to light that the re-internment of all burials at Rangoon War Cemetery from the English Cantonment Cemetery, took place on the 14th June 1946. This information, along with other related documents can be viewed on the CWGC website by simply searching for a casualty by name and scrolling to the appropriate section on the page.

Update 12/01/2016.

From information shown on one of the new documents mentioned in the last update, it has now been confirmed that at least some of the memorial plaques presented at Rangoon War Cemetery, were engraved by the firm, 'Arrow Engraving Company' of Melbourne, Australia. The company still exist today, but are now known as Arrow Bronze. http://www.arrowbronze.com.au/history

From new information released by the CWGC on the 70th Anniversary of VJ Day, it has now come to light that the re-internment of all burials at Rangoon War Cemetery from the English Cantonment Cemetery, took place on the 14th June 1946. This information, along with other related documents can be viewed on the CWGC website by simply searching for a casualty by name and scrolling to the appropriate section on the page.

Update 12/01/2016.

From information shown on one of the new documents mentioned in the last update, it has now been confirmed that at least some of the memorial plaques presented at Rangoon War Cemetery, were engraved by the firm, 'Arrow Engraving Company' of Melbourne, Australia. The company still exist today, but are now known as Arrow Bronze. http://www.arrowbronze.com.au/history

The English Cantonment Cemetery, Rangoon.

On one of the early days during our tour of Burma in 2008, veteran Denis Gudgeon recounted a story of a typical burial for one of the many Chindit casualties in Rangoon Jail during 1943. An officer was elected to take charge of the service, some of the deceased friends or comrades were gathered together and the body, often wrapped in rice sacks would be placed onto a cart and pushed through the streets of Rangoon to the cemetery just over a mile to the east of the jail. A tattered Union Jack would drape the body as the procession moved slowly from the jail to the burial ground.

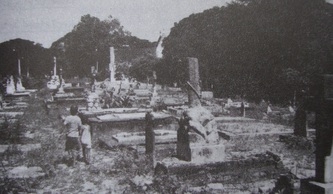

The burial ground was the old Cantonment Cemetery which had been used for many years as the final resting place for military men and European civilians who had died in or around the city of Rangoon. The deceased POW received as decent a Christian burial as the group could provide, hymns were sung and simple prayers were spoken. For once the Japanese guards would offer up some form of courtesy and allow the process to be carried out in a respectful and dignified way. Denis remembered the many occasions when he too was involved with these desperately solemn ceremonies, sometimes burying several men in a single service. He also told us that the burial ground was right next door to the zoo and close to the Royal Lakes in the eastern quarter of the city. He said that often the cries and sounds of the animals could be heard over the quiet voices of the officers and men as they read out the prayers for the recently deceased soldiers.

Below are some old photographs of the Cantonment Cemetery and gardens probably from the period just after WW1, the more modern photograph was taken in 2010 and shows the original outside walls of the cemetery which is now used by the Burmese military. Please click on each image to enlarge:

The burial ground was the old Cantonment Cemetery which had been used for many years as the final resting place for military men and European civilians who had died in or around the city of Rangoon. The deceased POW received as decent a Christian burial as the group could provide, hymns were sung and simple prayers were spoken. For once the Japanese guards would offer up some form of courtesy and allow the process to be carried out in a respectful and dignified way. Denis remembered the many occasions when he too was involved with these desperately solemn ceremonies, sometimes burying several men in a single service. He also told us that the burial ground was right next door to the zoo and close to the Royal Lakes in the eastern quarter of the city. He said that often the cries and sounds of the animals could be heard over the quiet voices of the officers and men as they read out the prayers for the recently deceased soldiers.

Below are some old photographs of the Cantonment Cemetery and gardens probably from the period just after WW1, the more modern photograph was taken in 2010 and shows the original outside walls of the cemetery which is now used by the Burmese military. Please click on each image to enlarge:

I have been unable to find out too much information in regard to the history of the Cantonment Cemetery in Rangoon, but it would have acted as the main burial site for all British Military deaths during the late Victorian era, through until the outbreak of WW2. The British Army had located garrisons throughout Burma since the early 1800's and this included one at Rangoon. The vast majority of the burials at Rangoon would have been casualties from the last Burmese War in the late 1880's and men who had lost their lives performing garrison duties in WW1 and in the subsequent years up until about 1932.

Major-General Sir Herbert Taylor MacPherson VC was buried in the Cantonment Cemetery in 1886, he had suffered a long drawn out battle against malaria and fever, something that would be a common cause of death for many of the soldiers present in Burma at that time. It is true to say that disease accounted for the majority of the deaths in Burma back then, something that was to continue right through to the early years of the campaign in WW2. There was also a local folklore which stated that the great Irrawaddy River would always take at least one life by drowning from every new British regimental unit sent to garrison in Burma. Eerily, this did happen more often than not.

The Cantonment Cemetery received a new group of burials in January 1929. These were the exhumed bodies of British soldiers who had perished during the years taken up by World War One. Previously these men had lain in the northeast platform of the Shwedagon Pagoda, the most famous and revered landmark in Rangoon and one of the most sacred pagodas anywhere in the world. The Burmese government had repeatedly asked the British representatives in Rangoon to remove these burials from the sacred Buddhist monument, thus allowing the religious site to be free of this desecration for the first time in over a decade.

The Japanese had used the cemetery as a convenient place to bury the Allied casualties from Rangoon Jail and other surrounding areas, after the war was over the Imperial War Graves Commission moved the burials to the newly created Rangoon War Cemetery, built on grounds close to the old University. This took place in late 1945 and continued on into 1947, in the meantime the old Cantonment Cemetery was left unattended for several years until the Burmese Military decided to use it as a base.

Below and just for interest sake really, are two photographs of the campaign medals awarded to British and Indian troops which served in Burmese garrisons during the latter part of Queen Victoria's reign, and the years leading up to World War One, and who would have been buried in places like the English Cantonment Cemetery. Please click on the image to enlarge.

Major-General Sir Herbert Taylor MacPherson VC was buried in the Cantonment Cemetery in 1886, he had suffered a long drawn out battle against malaria and fever, something that would be a common cause of death for many of the soldiers present in Burma at that time. It is true to say that disease accounted for the majority of the deaths in Burma back then, something that was to continue right through to the early years of the campaign in WW2. There was also a local folklore which stated that the great Irrawaddy River would always take at least one life by drowning from every new British regimental unit sent to garrison in Burma. Eerily, this did happen more often than not.

The Cantonment Cemetery received a new group of burials in January 1929. These were the exhumed bodies of British soldiers who had perished during the years taken up by World War One. Previously these men had lain in the northeast platform of the Shwedagon Pagoda, the most famous and revered landmark in Rangoon and one of the most sacred pagodas anywhere in the world. The Burmese government had repeatedly asked the British representatives in Rangoon to remove these burials from the sacred Buddhist monument, thus allowing the religious site to be free of this desecration for the first time in over a decade.

The Japanese had used the cemetery as a convenient place to bury the Allied casualties from Rangoon Jail and other surrounding areas, after the war was over the Imperial War Graves Commission moved the burials to the newly created Rangoon War Cemetery, built on grounds close to the old University. This took place in late 1945 and continued on into 1947, in the meantime the old Cantonment Cemetery was left unattended for several years until the Burmese Military decided to use it as a base.

Below and just for interest sake really, are two photographs of the campaign medals awarded to British and Indian troops which served in Burmese garrisons during the latter part of Queen Victoria's reign, and the years leading up to World War One, and who would have been buried in places like the English Cantonment Cemetery. Please click on the image to enlarge.

At the Imperial War Museum there are files containing listings for all those men who perished in Blocks 3 and 6 of Rangoon Jail, the vast majority of the men featured were Chindits from 1943. Presumably there must have been similar lists for all the other blocks and for all the other nationalities present. On the lists for Blocks 3 and 6 along with the casualties name, rank and service number, sometimes appears two other entries. These are his POW number as allocated on his arrival at the jail and a grave reference number which records whereabouts in the Cantonment Cemetery he was first buried. I am not sure whether it was the Japanese authorities who insisted on recording such details or, and perhaps more likely, the senior officers amongst the Allied POW's themselves.

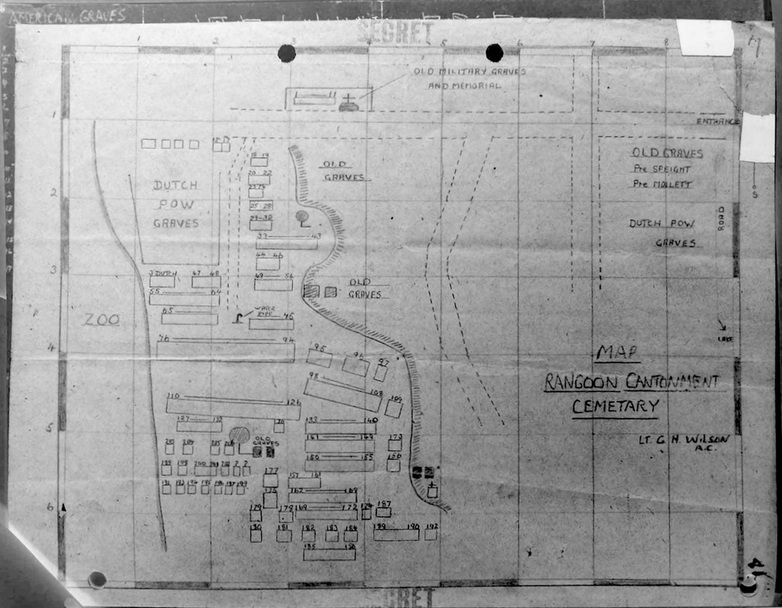

At the National Archives in Washington (NARA) there are many documents in regard to the numerous American POW's held in Rangoon Jail. Included amongst these is a map of the Old Cantonment Cemetery in Rangoon and the information upon it helps put all the other details mentioned on the casualty listing into perspective. It also confirms the close location of the cemetery to the city zoo and that there were at one time a large contingent of Dutch POW's held in Rangoon Jail.

Shown below is the map in question. It clearly shows the dimensions of the cemetery, the location of the numbered burials and the Dutch graves, also the map shows the zoo on the cemetery's western border. Please click on the image to bring it forward.

At the National Archives in Washington (NARA) there are many documents in regard to the numerous American POW's held in Rangoon Jail. Included amongst these is a map of the Old Cantonment Cemetery in Rangoon and the information upon it helps put all the other details mentioned on the casualty listing into perspective. It also confirms the close location of the cemetery to the city zoo and that there were at one time a large contingent of Dutch POW's held in Rangoon Jail.

Shown below is the map in question. It clearly shows the dimensions of the cemetery, the location of the numbered burials and the Dutch graves, also the map shows the zoo on the cemetery's western border. Please click on the image to bring it forward.

The large contingent of Dutch POW's came from the ill-fated voyage of the hell-ship 'Tacoma Maru'. This ship had left Batavia on the 16th October 1942 and had docked at Singapore with many of the prisoners already suffering from severe dysentery, some left the ship at this point, but many more were cruelly left aboard by the callous Japanese guards as the ship moved out to sea once more. After being attacked by Allied submarines the Tacoma Maru decided to head for the west coast of Burma, by this time (07/11/1942) there were over 600 hundred cases of dysentery aboard. Here is a transcription from Rohan Rivett's book 'Behind Bamboo', where he mentions the stricken POW's aboard the Tacoma Maru:

"All things considered we were tremendously lucky that the dysentery epidemic did not sweep through our own crowded holds. The sad fate of 1500 Dutch POW's who left Batavia just one week after us, proved how uncheckable the infection would be in such circumstances. The prisoners never left the ship during 22 days and nights of hell from Batavia to Rangoon. After taking 10 days to reach Penang they lay stifling there for 9 days following a submarine attack. Dysentery, already bad, now spread like a bushfire. All the prisoners were eventually herded into Rangoon Jail where the worst cases were placed in batches of 60 into bare stone cells with nothing but straw on the floor. They were left all night without food, water, pans, buckets or anything else, this was a death sentence for many."

The Japanese medical staff did nothing to help these men and as the living buried the dead the guards even switched the wooden crosses from grave to grave to confuse the accurate recording of the casualties identity. By the time the remainder of the party was moved on in late December to work on the infamous Burma Railway, there were 260 dead Dutch POW's buried in the Cantonment Cemetery. After the war the Dutch authorities removed the remains of these POW's and re-interred them at their own war cemetery, Menteng Pulo, located in the Indonesian capital city, Jakarta.

The two photographs shown below give an aerial view of the cemetery as seen circa December 1944. The images were I presume, taken by Allied reconnaissance aircraft flying over Rangoon at that time. The second image although rotated by 90 degrees, shows the NARA map superimposed onto the original photograph and gives us a perfect plan of cemetery's orientation. Once again it confirms the nearby location of the city zoo bordering the western boundary of the cemetery, so it was no wonder that the sound of elephants trumpeting was a regular occurrence during the funeral services held there.