'Jai Mahakali, Ayo Gorkhali'

'Victory to the Goddess Mahakali, here come the Gurkhas.'

This has been the traditional battle cry of the Gurkhas throughout their history as a warrior race. Instilled into the young recruits is a passion for honour, brotherhood and glory, with the motto exclaiming "it is better to die, than to live life as a coward."

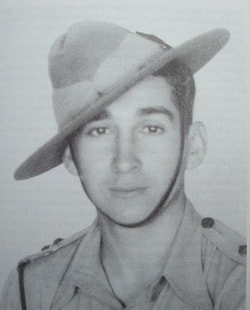

Pictured left is a group of young recruits who are taking the first steps toward representing their family clan within the regiment. (Photo taken from 'The Gurkhas', a book by Harold James).

Many of the men of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles paid the ultimate price in 1943, as they helped to prove the theory of Long Range Penetration. The survivors of operation Longcloth went on to serve again in 1944, this time in the treacherous conditions of the Arakan peninsula, many perished here as they slowly pushed the Japanese back toward the Irrawaddy delta. The young soldiers of 3/2 Gurkha never failed to impress the men who commanded them in both these conflicts, against a ruthless and determined foe. Here are the thoughts and views of some of the men who led Gurkha sections in 1943 and 1944.

This has been the traditional battle cry of the Gurkhas throughout their history as a warrior race. Instilled into the young recruits is a passion for honour, brotherhood and glory, with the motto exclaiming "it is better to die, than to live life as a coward."

Pictured left is a group of young recruits who are taking the first steps toward representing their family clan within the regiment. (Photo taken from 'The Gurkhas', a book by Harold James).

Many of the men of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles paid the ultimate price in 1943, as they helped to prove the theory of Long Range Penetration. The survivors of operation Longcloth went on to serve again in 1944, this time in the treacherous conditions of the Arakan peninsula, many perished here as they slowly pushed the Japanese back toward the Irrawaddy delta. The young soldiers of 3/2 Gurkha never failed to impress the men who commanded them in both these conflicts, against a ruthless and determined foe. Here are the thoughts and views of some of the men who led Gurkha sections in 1943 and 1944.

Column 3 commander Mike Calvert took over control of his Gurkhas from one of the few men on Operation Longcloth that could actually speak Gurkhali. There is no doubt that George Silcock was annoyed to hand over the command of his unit to Calvert, but he remained the ever professional soldier throughout the expedition ensuring the men fully understood their orders and backing his C/O to the hilt.

To Calvert's credit he then allowed Silcock his area of influence within the column and together they achieved arguably the best results with the Gurkha Riflemen they commanded. Calvert had spotted the Gurkhas dislike and misunderstanding of the dispersal tactic during their training period and he rarely used this system when the column was on active service in Burma. He realised that breaking the unit down into smaller groups when trouble or danger threatened, went totally against the Gurkhas instincts and deep sense of loyalty to what they saw as their extended family.

He also realised that language was a real problem when communicating complex battle plans to the Gurkha troops, despite this he was always impressed with their efforts:

"They underwent great physical endurance and hardships, which would have tested the finest troops in the world. I cannot show too much admiration for the way these young Gurkhas marched great distances over very difficult country, bore heavy loads, carried out rearguard actions, were restrained at all times in matters of line discipline, fire and bivouac procedure. They also quickly learned to fight on the run, with great bravery and rarely cracked under pressure."

The Gurkha Riflemen of Column 3 recognised the strong leadership qualities of their Commander, however, from the many books I have read, they rarely remembered his name correctly. Some refer to him as our 'Mad Brigade Major', others as Major 'Calpat'.

To Calvert's credit he then allowed Silcock his area of influence within the column and together they achieved arguably the best results with the Gurkha Riflemen they commanded. Calvert had spotted the Gurkhas dislike and misunderstanding of the dispersal tactic during their training period and he rarely used this system when the column was on active service in Burma. He realised that breaking the unit down into smaller groups when trouble or danger threatened, went totally against the Gurkhas instincts and deep sense of loyalty to what they saw as their extended family.

He also realised that language was a real problem when communicating complex battle plans to the Gurkha troops, despite this he was always impressed with their efforts:

"They underwent great physical endurance and hardships, which would have tested the finest troops in the world. I cannot show too much admiration for the way these young Gurkhas marched great distances over very difficult country, bore heavy loads, carried out rearguard actions, were restrained at all times in matters of line discipline, fire and bivouac procedure. They also quickly learned to fight on the run, with great bravery and rarely cracked under pressure."

The Gurkha Riflemen of Column 3 recognised the strong leadership qualities of their Commander, however, from the many books I have read, they rarely remembered his name correctly. Some refer to him as our 'Mad Brigade Major', others as Major 'Calpat'.

Major George Dunlop was never overly comfortable leading one of the Gurkha units, in his case No. 1 Column. He could see the mistake of replacing established Gurkha officers who could converse with their NCO's, with British officers of quality, but with little experience leading Indian troops. He had come from a special forces background and had fought alongside Mike Calvert in 1942 and also trained men at the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo.

After returning to India post Longcloth, Dunlop was keen to discuss a few things with his commanding officer and he and Wingate had some rather frank conversations while recuperating in hospital. In the end Wingate put a stop to these arguments, telling Dunlop that there was no reward in "washing their dirty linen in public."

Here is what George Dunlop had to say about his time with the Gurkhas:

"The great mistake was having officers that could not speak directly and properly to their men. This placed far too greater a strain on the column commander. In the Gurkha columns on Longcloth there were men from four different races and languages. To get these groups to work together in times of hardship was difficult in the extreme. I have to confess that this wore me right down.

The commander must be as fit and strong as any of his men, indeed probably more so, as all questions and decisions are ultimately down to him. This is of course how it should be, but I can tell you it is very hard. He must decide everything, right down to the last grain of rice (literally) and he must take all the blame if things go wrong."

In the end Dunlop felt that the Gurkha columns had produced mixed results, with the other ranks performing well and willingly obeying the company orders. He had felt rather sorry for the younger subalterns, who had the toughest of all jobs, leading the riflemen, whilst having no real power to influence decisions themselves.

After returning to India post Longcloth, Dunlop was keen to discuss a few things with his commanding officer and he and Wingate had some rather frank conversations while recuperating in hospital. In the end Wingate put a stop to these arguments, telling Dunlop that there was no reward in "washing their dirty linen in public."

Here is what George Dunlop had to say about his time with the Gurkhas:

"The great mistake was having officers that could not speak directly and properly to their men. This placed far too greater a strain on the column commander. In the Gurkha columns on Longcloth there were men from four different races and languages. To get these groups to work together in times of hardship was difficult in the extreme. I have to confess that this wore me right down.

The commander must be as fit and strong as any of his men, indeed probably more so, as all questions and decisions are ultimately down to him. This is of course how it should be, but I can tell you it is very hard. He must decide everything, right down to the last grain of rice (literally) and he must take all the blame if things go wrong."

In the end Dunlop felt that the Gurkha columns had produced mixed results, with the other ranks performing well and willingly obeying the company orders. He had felt rather sorry for the younger subalterns, who had the toughest of all jobs, leading the riflemen, whilst having no real power to influence decisions themselves.

Lieutenant Dominic Neill was from the 2nd Gurkhas, and one of the newly commissioned subalterns detailed as Animal Transport officers in 1943. He was posted originally at a place called Guna, where he and the Gurkha muleteers met with and trained their charges. He was attached to the mainly British 8 Column under the leadership of Major Scott:

"To this day I can remember how heart-broken I was. As a young man and about to go to war for the first time, I had wanted so dearly to go with my own regiment, and to lead the Gurkhas, whom I had already grown to love and admire greatly."

He need not of worried, as a day or so later a section of 10th Gurkhas arrived complete with mules and joined his unit as a second line of muleteers for Scott's column. 'Nick' Neill (as he was known during his Army career) was fairly scathing about the quality of Chindit training, especially over the communication difficulties posed by having a mix of British and Indian troops working so closely together and yet having no common language. He also thought exchanging the experienced Gurkha officers originally chosen to lead columns one, three and four, with British commanders was a terrible decision, that would prove very costly once inside Burma.

In Burma that year things had gone decently for Lieutenant Neill and his 52 Gurkha muleteers. When the order to return to India came he and his unit turned around and headed back westward. On the 14th April and having just collected some rice from a local village his group was ambushed by the Japanese. It was at this point that he suddenly realised how inexperienced he and his young Gurkhas really were:

"I was totally shocked, I had not been taught any contact or anti-ambush drills in training and was appalled to realise I simply did not know what to do for my men."

During a lull in the fighting Nick decided to try an extricate his men and called out "Sabai jana ut! Mero pachhi aija!" (everybody up, follow me). The group moved away as quickly as it could manage through the bamboo thickets that made up the jungle in those parts. When at last they could slow down and take stock of the situation, Neill found to his horror that only one fifth of his Gurkhas were still with him: "Although I felt that the remainder would not necessarily have been killed, I knew that they had no maps or compasses and so their chances of escaping were slim. My guilt at not being able to do better for them in the ambush, and being unable to maintain contact with them afterwards, hung very heavy on my conscience and still does to this day."

Lieutenant Nick Neill went on to enjoy an illustrious career in the Armed Forces and taught the art of Guerrilla Warfare to many soldiers after his experiences in 1942/43. He obviously was determined never to find himself in such a helpless position again, especially when commanding young and inexperienced Gurkha troops. Here is the last paragraph from his Military Cross citation which he was awarded the very next year, whilst fighting in the Maungdaw area of the Arakan. It shows that in a very short space of time he had learned his lessons in army tactical drills and how to take control of his beloved Gurkha riflemen.

"On another occasion he (Neill) relentlessly pursued a Japanese unit for over 3000 yards, completely destroying it in the end. The manner in which Lt. Neill carried out this task was outstanding. He displayed great courage, devotion to duty and powers of dealing with rapidly changing situations. His leadership undoubtedly inspired all ranks under his command."

"To this day I can remember how heart-broken I was. As a young man and about to go to war for the first time, I had wanted so dearly to go with my own regiment, and to lead the Gurkhas, whom I had already grown to love and admire greatly."

He need not of worried, as a day or so later a section of 10th Gurkhas arrived complete with mules and joined his unit as a second line of muleteers for Scott's column. 'Nick' Neill (as he was known during his Army career) was fairly scathing about the quality of Chindit training, especially over the communication difficulties posed by having a mix of British and Indian troops working so closely together and yet having no common language. He also thought exchanging the experienced Gurkha officers originally chosen to lead columns one, three and four, with British commanders was a terrible decision, that would prove very costly once inside Burma.

In Burma that year things had gone decently for Lieutenant Neill and his 52 Gurkha muleteers. When the order to return to India came he and his unit turned around and headed back westward. On the 14th April and having just collected some rice from a local village his group was ambushed by the Japanese. It was at this point that he suddenly realised how inexperienced he and his young Gurkhas really were:

"I was totally shocked, I had not been taught any contact or anti-ambush drills in training and was appalled to realise I simply did not know what to do for my men."

During a lull in the fighting Nick decided to try an extricate his men and called out "Sabai jana ut! Mero pachhi aija!" (everybody up, follow me). The group moved away as quickly as it could manage through the bamboo thickets that made up the jungle in those parts. When at last they could slow down and take stock of the situation, Neill found to his horror that only one fifth of his Gurkhas were still with him: "Although I felt that the remainder would not necessarily have been killed, I knew that they had no maps or compasses and so their chances of escaping were slim. My guilt at not being able to do better for them in the ambush, and being unable to maintain contact with them afterwards, hung very heavy on my conscience and still does to this day."

Lieutenant Nick Neill went on to enjoy an illustrious career in the Armed Forces and taught the art of Guerrilla Warfare to many soldiers after his experiences in 1942/43. He obviously was determined never to find himself in such a helpless position again, especially when commanding young and inexperienced Gurkha troops. Here is the last paragraph from his Military Cross citation which he was awarded the very next year, whilst fighting in the Maungdaw area of the Arakan. It shows that in a very short space of time he had learned his lessons in army tactical drills and how to take control of his beloved Gurkha riflemen.

"On another occasion he (Neill) relentlessly pursued a Japanese unit for over 3000 yards, completely destroying it in the end. The manner in which Lt. Neill carried out this task was outstanding. He displayed great courage, devotion to duty and powers of dealing with rapidly changing situations. His leadership undoubtedly inspired all ranks under his command."

Another young officer who found himself leading Gurkha riflemen in 1943 was Lieutenant Denis Gudgeon. He was part of column 3 that year and under the command of Major Mike Calvert. He once told me that if you showed an understanding and appreciation of the Gurkha soldier and what he stood for, then the soldier would be totally loyal to you as an officer in return. He could not help but admire their devotion to each other and the cause at hand.

In April 1943, Denis and the rest of column 3 prepared for dispersal and the return journey back to India, he led a small group of men, eleven of which were Gurkha riflemen. At one of the main river crossings on the journey back Denis and his men became separated. They had built a makeshift rafts and tried to get across, but the raft had collapsed and they had to return to their starting point. Eventually Denis organised a local boatman to take them across to the other side, once over he ordered his Gurkhas to move on quickly toward India while he recuperated from the days tribulations. The loyal Gurkha soldiers moved off as ordered, but then decided to return for their leader, sadly he was nowhere to be found.

Denis had accepted the hospitality of another local Burmese villager, but had been turned over to a Japanese patrol party who were in the vicinity. I remember in 2008 when the British Legion tour visited the cemeteries at Rangoon and Taukkyan, how Denis would become uncharacteristically quiet and wander around the graves and memorials of his lost comrades. This was never more apparent than when he stood in front of panels 57 and 58 of the Rangoon Memorial and looked upon the names of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles. I will let Denis have the last word on the subject with a quote taken from our discussions whilst in Burma in March 2008.

"These young soldiers were at first very confused by the nature of Long range penetration, it was of course against their frank and forthright nature as fighting men. But if you took them under your wing and attempted, (and this was not easy with the language barrier), to explain the plans and theories, then they would perform the role with total commitment and many times lay down their lives doing so."

In April 1943, Denis and the rest of column 3 prepared for dispersal and the return journey back to India, he led a small group of men, eleven of which were Gurkha riflemen. At one of the main river crossings on the journey back Denis and his men became separated. They had built a makeshift rafts and tried to get across, but the raft had collapsed and they had to return to their starting point. Eventually Denis organised a local boatman to take them across to the other side, once over he ordered his Gurkhas to move on quickly toward India while he recuperated from the days tribulations. The loyal Gurkha soldiers moved off as ordered, but then decided to return for their leader, sadly he was nowhere to be found.

Denis had accepted the hospitality of another local Burmese villager, but had been turned over to a Japanese patrol party who were in the vicinity. I remember in 2008 when the British Legion tour visited the cemeteries at Rangoon and Taukkyan, how Denis would become uncharacteristically quiet and wander around the graves and memorials of his lost comrades. This was never more apparent than when he stood in front of panels 57 and 58 of the Rangoon Memorial and looked upon the names of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles. I will let Denis have the last word on the subject with a quote taken from our discussions whilst in Burma in March 2008.

"These young soldiers were at first very confused by the nature of Long range penetration, it was of course against their frank and forthright nature as fighting men. But if you took them under your wing and attempted, (and this was not easy with the language barrier), to explain the plans and theories, then they would perform the role with total commitment and many times lay down their lives doing so."

Column 2 made it's way along the railway tracks toward the village of Kyaikthin, it was dark and roughly ten o'clock on the night of the 2nd March. Columns one and two knew they had been sent out as a decoy, and now they were approaching the main objective of their involvement on operation Longcloth.

Near the rear of the column was a young officer, Lieutenant Ian MacHorton, he had been following the man in front for over two hours as the column progressed toward the rail station, nerves were very much on edge as moonlight came and went from behind the cloud covered Burmese sky. Ian had joined the operation at the last minute and had been sent to join Major Arthur Emmett's group, Emmett was the only original Gurkha column commander from training, to enter Burma still in charge of his unit.

All of a sudden his world turned to chaos as the Japanese opened fire on the unsuspecting Chindits. An atmosphere of confusion and panic overwhelmed the men as they attempted to find precious cover and locate the position of their enemy. As MacHorton pushed himself as deeply as he could into the loose gravel of the rail embankment and set his weapon forward, he began to wonder how the young Gurkhas would stand up to their first engagement with the Japanese.

Even in the heat of the battle his mind kept returning to the training drills just a few short weeks before and how the men would boast about what they might do to the enemy in battle.

"They were always in high spirits, sharpening their kukris and pronouncing their intent toward the Japanese. Already I was greatly attached to these stocky little warriors, with their wide set almond shaped eyes, flat noses and faces that never seemed capable of growing even a single hair. They were good tempered and trained well, they did not know the meaning of the word fear, they simply loved soldiering and adventure."

Rifleman Kulbahadur Thapa was chosen as MacHorton's orderly on operation Longcloth and had shadowed him faithfully during the early weeks inside Burma. He was right next to him during the engagement at Kyaikthin, and again as they extricated themselves from that desperate situation. Eventually the column broke out from the railway embankment and what was left of the unit gathered once more at the previously agreed forward rendezvous. Later on the during the campaign the unthinkable happened and MacHorton was wounded in a fire fight with the Japanese. He knew he would not be able to continue marching with the column and the horror of being left to fend for himself and worse still being taken prisoner by the Japanese began to torment his mind. Once again the loyalty and selfless nature of the Gurkha Other ranks showed through. I will leave Lieutenant MacHorton to explain the situation:

"Kulbahadur was cutting away the undergrowth to create a space for me to lie up and hopefully regain my strength. I noticed he was clearing quite a large area and told him to stop. He answered that the space was not just for one man, but two and that he intended to remain with me. I was astounded by this action and fell silent for a minute. Kulbahadur went on to elaborate, saying that as my orderly it was his duty to stay with me. The magnificence of his loyalty touched me deeply. The rush of relief to hear that I would not be alone, soon turned to the sad realisation that I could not ask him to give up his freedom and probably his life, by remaining with me in that lonely jungle copse. Digging deep I found the resolve to ask and then order Kulbahadur to leave me where I lay and rejoin the column. Just before he went on his way Kulbahadur announced that we would certainly meet again some day, of this he felt sure, then there was a rustle of leaves and he was gone."

Near the rear of the column was a young officer, Lieutenant Ian MacHorton, he had been following the man in front for over two hours as the column progressed toward the rail station, nerves were very much on edge as moonlight came and went from behind the cloud covered Burmese sky. Ian had joined the operation at the last minute and had been sent to join Major Arthur Emmett's group, Emmett was the only original Gurkha column commander from training, to enter Burma still in charge of his unit.

All of a sudden his world turned to chaos as the Japanese opened fire on the unsuspecting Chindits. An atmosphere of confusion and panic overwhelmed the men as they attempted to find precious cover and locate the position of their enemy. As MacHorton pushed himself as deeply as he could into the loose gravel of the rail embankment and set his weapon forward, he began to wonder how the young Gurkhas would stand up to their first engagement with the Japanese.

Even in the heat of the battle his mind kept returning to the training drills just a few short weeks before and how the men would boast about what they might do to the enemy in battle.

"They were always in high spirits, sharpening their kukris and pronouncing their intent toward the Japanese. Already I was greatly attached to these stocky little warriors, with their wide set almond shaped eyes, flat noses and faces that never seemed capable of growing even a single hair. They were good tempered and trained well, they did not know the meaning of the word fear, they simply loved soldiering and adventure."

Rifleman Kulbahadur Thapa was chosen as MacHorton's orderly on operation Longcloth and had shadowed him faithfully during the early weeks inside Burma. He was right next to him during the engagement at Kyaikthin, and again as they extricated themselves from that desperate situation. Eventually the column broke out from the railway embankment and what was left of the unit gathered once more at the previously agreed forward rendezvous. Later on the during the campaign the unthinkable happened and MacHorton was wounded in a fire fight with the Japanese. He knew he would not be able to continue marching with the column and the horror of being left to fend for himself and worse still being taken prisoner by the Japanese began to torment his mind. Once again the loyalty and selfless nature of the Gurkha Other ranks showed through. I will leave Lieutenant MacHorton to explain the situation:

"Kulbahadur was cutting away the undergrowth to create a space for me to lie up and hopefully regain my strength. I noticed he was clearing quite a large area and told him to stop. He answered that the space was not just for one man, but two and that he intended to remain with me. I was astounded by this action and fell silent for a minute. Kulbahadur went on to elaborate, saying that as my orderly it was his duty to stay with me. The magnificence of his loyalty touched me deeply. The rush of relief to hear that I would not be alone, soon turned to the sad realisation that I could not ask him to give up his freedom and probably his life, by remaining with me in that lonely jungle copse. Digging deep I found the resolve to ask and then order Kulbahadur to leave me where I lay and rejoin the column. Just before he went on his way Kulbahadur announced that we would certainly meet again some day, of this he felt sure, then there was a rustle of leaves and he was gone."

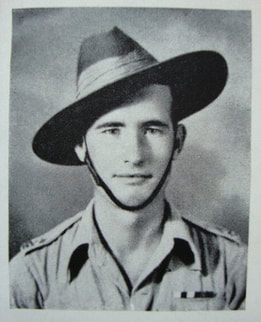

Major Adrian G. Hayter MBE, MC.

Major Adrian G. Hayter MBE, MC.

From his book 'The Second Step', Officer Cadet Adrian Hayter tells of his decision and passion to join the British Indian Army and in particular a Gurkha Regiment. For those young officers whose father or grandfather had already served, the choice was simple and acceptance all but assured, but for the other men the pathway was not so straightforward.

The criteria for a successful recruitment was a mix of many things: which regiment you were plumping for, your performance and passing out scores at Sandhurst, your financial means and support which may be needed to supplement the often poor remuneration provided by some of the regiments and of course the old boy network. Hayter, coming as he did from New Zealand farming stock had no such means at his disposal and so stated in his application papers:

Choice 1. A Gurkha Regiment

Choice 2. A Gurkha Regiment

Choice 3. A Gurkha Regiment

The strategy worked. He was soon interviewed by a recently retired senior officer from a Gurkha Regiment, where his credentials were inspected and the requirements of joining such a well respected regiment clearly laid out. When asked which of the 10 Gurkha units he was hoping for, Hayter, somewhat unsure of himself stated "I'm sure I'd be very happy in any, sir". It was an answer that opened the door, but in reality the choice would not be that simple.

Here is how Hayter came to his final decision: "Of all the races which formed the Regiments of the Indian Army, none to my knowledge had a more consistent reputation than the Gurkhas, whether this be their cheerful candour, their integrity as individuals or their courage and unshakeable loyalty as friends. It was only after arrival in India that I learnt that the ten regiments varied so much in character and that there was a need to make my choice with care.

All Gurkha Regiments had their regimental homes and depots in the hills above the Indian plains, this was done because the homes of the men themselves were at heights generally between 2000 and 7000 feet above sea-level, in their own country Nepal, which lies along the southern buttress of the mighty Himalayas.

In some cases those regimental homes were very isolated and the officers tended to become a bit mad. They flung themselves fanatically into every local outdoor pursuit and eventually became more 'Gurkha' than the men they were supposed to command.

However, there was another variation between the regimental units, this being the tribes and sub-tribes from which they recruited. The 7th and 10th recruited Limbus and Rais from Eastern Nepal, and these men had a name for being less stable than the ordinary Gurkha soldier. They were said to be quick to anger and to take offence. The 9th recruited Tahkurs and Chettris, who are high caste and orthodox Hindus, I shied away from orthodoxy on principle because it too easily demands a greater loyalty than logic itself, and is more than I am prepared to give.

The remaining seven Regiments all took from the two big work-a-day tribal castes of Magars and Gurungs, who are farmers and fighters. Of these I found the 1st and 3rd to be somewhat strange, with the British Officers insisting on speaking Gurkhali even in the Mess, the 4th seemed to have no particular reputation of any kind and the 5th and 6th far too dedicated. The 8th were supposed to be a bit casual, and I'd already learnt that whenever I was allowed to be casual, I begun to show distressing signs of delinquency; which always left me without friends.

That assessment of Regiments was probably inaccurate, but it was the best one could do from the meagre hearsay available at the time. It left only the 2nd, known as "God's Own", but I couldn't expect to have everything. And so it was to the 2nd that I applied. In due course I received a letter from the Adjutant of the 2nd Battalion, 2nd King Edward the Seventh's Own Gurkha Rifles:

Dear Hayter,

We hear you would like to come to us as your permanent Indian Army unit. We are not sure yet whether the MS will give us a vacancy, but we'd be so pleased if you could take a week's leave and come up to Dehra Doon to stay with us. It would give you a good opportunity to meet us all, the Gurkha Officers and the men, and to find out how we live and what our interests are. Let us know when you'll arrive and we will send someone to meet you at the station.

Your sincerely etc.

What the letter really meant was, we do have a vacancy and when we've had a look at you and if we approve, then fair enough we might offer you the posting. So I took my first leave and went up to Dehra Doon to find out if they did!

Adrian Hayter was a natural born Gurkha officer and quickly earned the respect of the men he commanded. In September 1944 during the fiercely fought actions in the Arakan region of Burma he was awarded the Military Cross for his instinctive and courageous leadership of a platoon of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles, and their success in wrestling a vital strategic position from the Japanese.

The criteria for a successful recruitment was a mix of many things: which regiment you were plumping for, your performance and passing out scores at Sandhurst, your financial means and support which may be needed to supplement the often poor remuneration provided by some of the regiments and of course the old boy network. Hayter, coming as he did from New Zealand farming stock had no such means at his disposal and so stated in his application papers:

Choice 1. A Gurkha Regiment

Choice 2. A Gurkha Regiment

Choice 3. A Gurkha Regiment

The strategy worked. He was soon interviewed by a recently retired senior officer from a Gurkha Regiment, where his credentials were inspected and the requirements of joining such a well respected regiment clearly laid out. When asked which of the 10 Gurkha units he was hoping for, Hayter, somewhat unsure of himself stated "I'm sure I'd be very happy in any, sir". It was an answer that opened the door, but in reality the choice would not be that simple.

Here is how Hayter came to his final decision: "Of all the races which formed the Regiments of the Indian Army, none to my knowledge had a more consistent reputation than the Gurkhas, whether this be their cheerful candour, their integrity as individuals or their courage and unshakeable loyalty as friends. It was only after arrival in India that I learnt that the ten regiments varied so much in character and that there was a need to make my choice with care.

All Gurkha Regiments had their regimental homes and depots in the hills above the Indian plains, this was done because the homes of the men themselves were at heights generally between 2000 and 7000 feet above sea-level, in their own country Nepal, which lies along the southern buttress of the mighty Himalayas.

In some cases those regimental homes were very isolated and the officers tended to become a bit mad. They flung themselves fanatically into every local outdoor pursuit and eventually became more 'Gurkha' than the men they were supposed to command.

However, there was another variation between the regimental units, this being the tribes and sub-tribes from which they recruited. The 7th and 10th recruited Limbus and Rais from Eastern Nepal, and these men had a name for being less stable than the ordinary Gurkha soldier. They were said to be quick to anger and to take offence. The 9th recruited Tahkurs and Chettris, who are high caste and orthodox Hindus, I shied away from orthodoxy on principle because it too easily demands a greater loyalty than logic itself, and is more than I am prepared to give.

The remaining seven Regiments all took from the two big work-a-day tribal castes of Magars and Gurungs, who are farmers and fighters. Of these I found the 1st and 3rd to be somewhat strange, with the British Officers insisting on speaking Gurkhali even in the Mess, the 4th seemed to have no particular reputation of any kind and the 5th and 6th far too dedicated. The 8th were supposed to be a bit casual, and I'd already learnt that whenever I was allowed to be casual, I begun to show distressing signs of delinquency; which always left me without friends.

That assessment of Regiments was probably inaccurate, but it was the best one could do from the meagre hearsay available at the time. It left only the 2nd, known as "God's Own", but I couldn't expect to have everything. And so it was to the 2nd that I applied. In due course I received a letter from the Adjutant of the 2nd Battalion, 2nd King Edward the Seventh's Own Gurkha Rifles:

Dear Hayter,

We hear you would like to come to us as your permanent Indian Army unit. We are not sure yet whether the MS will give us a vacancy, but we'd be so pleased if you could take a week's leave and come up to Dehra Doon to stay with us. It would give you a good opportunity to meet us all, the Gurkha Officers and the men, and to find out how we live and what our interests are. Let us know when you'll arrive and we will send someone to meet you at the station.

Your sincerely etc.

What the letter really meant was, we do have a vacancy and when we've had a look at you and if we approve, then fair enough we might offer you the posting. So I took my first leave and went up to Dehra Doon to find out if they did!

Adrian Hayter was a natural born Gurkha officer and quickly earned the respect of the men he commanded. In September 1944 during the fiercely fought actions in the Arakan region of Burma he was awarded the Military Cross for his instinctive and courageous leadership of a platoon of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles, and their success in wrestling a vital strategic position from the Japanese.

The three young 2nd Lieutenants excited by the news that they were to join a new force created for a special operation travelled up to Jhansi and entered the Chindit camp, which was then billeted at the town's racecourse. They were met by the Brigade Adjutant, Captain 'Bertie' Birtwhistle;

"Hello gentlemen, welcome aboard, by the way you are going straight into Burma, have you made your will."

Lieutenant Harold James was another of the young recruits from the Gurkha Rifles to join operation Longcloth at the very last moment in 1942. He came to 77th Brigade along with Alec Gibson and Ian MacHorton from the 8th Gurkhas who were previously based in Quetta. He was allocated a place in Mike Calvert's 3 column and settled down to work leading platoon 13.

Harold would go on to write several books about his time with the Gurkhas and also about their fabled military history throughout their decades within the British Army. The book Across the Threshold of Battle gives a stirring account of his own and his Gurkhas time in Burma that year. His admiration for the men of 3/2 Gurkha is very apparent and his defence of their performance in 1943 staunch and unwavering.

Lieutenant James was awarded the Military Cross in 1943 for his consistent bravery in the face of the enemy, usually beating back the determined Japanese patrols as the column attempted to cross the various rivers that year.

Here is part of the citation for his award as written down by Major Mike Calvert:

At NANKAN Railway Station on 6th March 1943, he showed coolness and self confidence in his first action when leading his platoon into the attack. On 23rd March 1943, during the crossing of the IRRAWADDY, his platoon was sited in a position to prevent the enemy crossing a creek, when the column was suddenly attacked by the enemy with small arms fire and mortars. He immediately attacked them inflicting heavy casualties and preventing them from crossing, personally walking round his platoon while under fire and placing his men in the best positions. This officer showed great devotion to duty throughout the campaign and great gallantry on many occasions.

Although very proud of his service in 1943, and rightly so, Harold would always be the first to congratulate his Gurkha Rilfemen and their contribution to the defence of the unit. He especially noted the performance of Jemadar (Junior Lieutenant) Andaram Gurung and of Lance Naik (Lance Corporal) Sherbahadur Ale, both of whom took part in all the actions mentioned within the citation of Harold's MC. In fact Sherbahadur went on to be awarded the Indian Distinguished Service Medal for his efforts on operation Longcloth. Here is part of his citation for the IDSM:

At PAGO on 25th March 1943 L/Nk. SHERBAHADUR ALE, under the orders of his Platoon Commander, led his section to the attack through the jungle, inflicted casualties on the enemy, got into position for the enemy counter attack, where more casualties were inflicted, and finally, on orders withdrew, keeping his section under good order and in control. In other engagements he also did well.

Harold James returned to Nepal some fifty years after the war in search of his brave Lance Naik, after many attempts to track Sherbahadur down a meeting was finally arranged in 1992. Sherbahadur used to travel to collect his British Army pension from the depot in Pokhara. I will leave Harold James to describe their emotional reunion, held with the beautiful Annapura mountain range as a backdrop to the meeting:

"Coming face to face with someone after fifty years, especially as we had once shared a very dangerous episode in our lives, was a strange experience. Seeing Sherbahdur in his traditional Nepali clothes and so much older, was like meeting a complete stranger. But quite suddenly as he grasped my hand in his, the years seemed to rush back and his face took on that somewhat cheeky look I remembered so well, and in particular I could recall how his eyes crinkled up at the sides.

So we talked as old friends do, although he did most of the talking as we relived those desperate moments in the Burmese jungle. His recollections of the Chindits and the actions of column 3 were almost the same as mine. It seemed as if the impression made on our minds had been equally strong, a passage of time quite impossible to ever erase. There were sad moments too when we spoke of those who had died that year. And eventually the all too sad moment when we finally had to say goodbye. Sherbahadur then grasped my hand fiercely once more and implored me to come back and visit him again the following year."

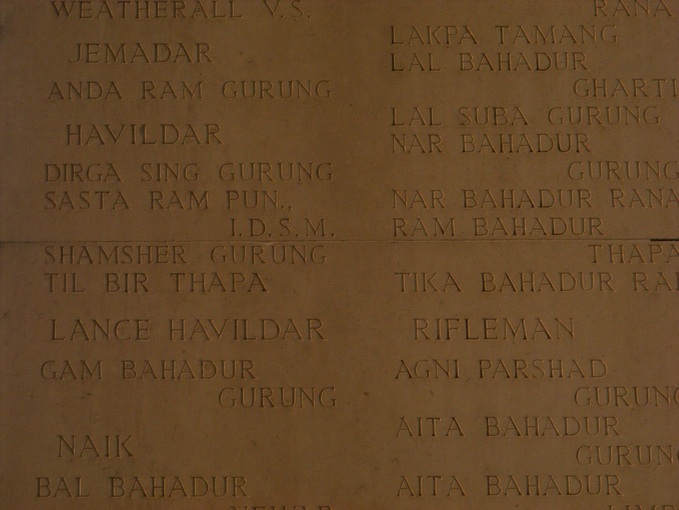

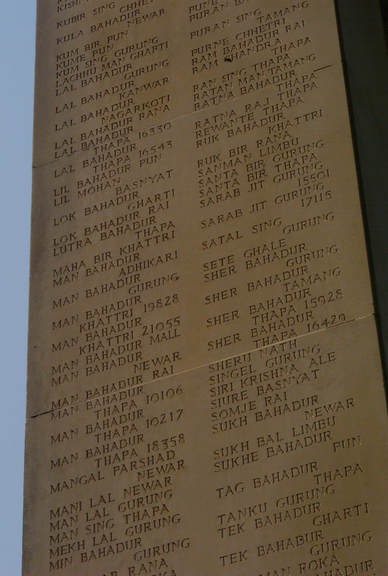

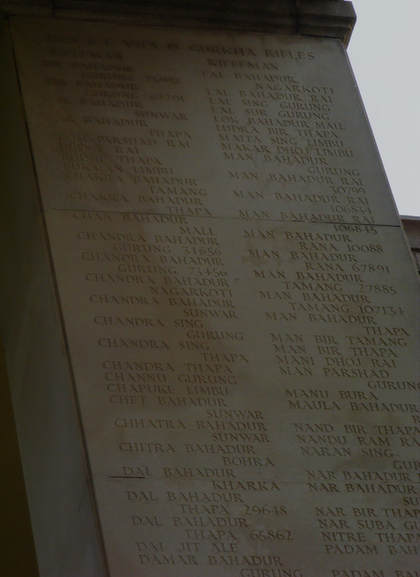

Below is a photograph of part of Face panel 57 from the Rangoon Memorial in Taukkyan War Cemetery. It shows the name of Jemadar Andaram Gurung (amongst others), the young Gurkha officer who fought alongside Harold throughout the expedition in 1943. Although Andaram had managed to escape back across the Chindwin River in 1943, he sadly died from the ravages of malaria in June that same year.

"Hello gentlemen, welcome aboard, by the way you are going straight into Burma, have you made your will."

Lieutenant Harold James was another of the young recruits from the Gurkha Rifles to join operation Longcloth at the very last moment in 1942. He came to 77th Brigade along with Alec Gibson and Ian MacHorton from the 8th Gurkhas who were previously based in Quetta. He was allocated a place in Mike Calvert's 3 column and settled down to work leading platoon 13.

Harold would go on to write several books about his time with the Gurkhas and also about their fabled military history throughout their decades within the British Army. The book Across the Threshold of Battle gives a stirring account of his own and his Gurkhas time in Burma that year. His admiration for the men of 3/2 Gurkha is very apparent and his defence of their performance in 1943 staunch and unwavering.

Lieutenant James was awarded the Military Cross in 1943 for his consistent bravery in the face of the enemy, usually beating back the determined Japanese patrols as the column attempted to cross the various rivers that year.

Here is part of the citation for his award as written down by Major Mike Calvert:

At NANKAN Railway Station on 6th March 1943, he showed coolness and self confidence in his first action when leading his platoon into the attack. On 23rd March 1943, during the crossing of the IRRAWADDY, his platoon was sited in a position to prevent the enemy crossing a creek, when the column was suddenly attacked by the enemy with small arms fire and mortars. He immediately attacked them inflicting heavy casualties and preventing them from crossing, personally walking round his platoon while under fire and placing his men in the best positions. This officer showed great devotion to duty throughout the campaign and great gallantry on many occasions.

Although very proud of his service in 1943, and rightly so, Harold would always be the first to congratulate his Gurkha Rilfemen and their contribution to the defence of the unit. He especially noted the performance of Jemadar (Junior Lieutenant) Andaram Gurung and of Lance Naik (Lance Corporal) Sherbahadur Ale, both of whom took part in all the actions mentioned within the citation of Harold's MC. In fact Sherbahadur went on to be awarded the Indian Distinguished Service Medal for his efforts on operation Longcloth. Here is part of his citation for the IDSM:

At PAGO on 25th March 1943 L/Nk. SHERBAHADUR ALE, under the orders of his Platoon Commander, led his section to the attack through the jungle, inflicted casualties on the enemy, got into position for the enemy counter attack, where more casualties were inflicted, and finally, on orders withdrew, keeping his section under good order and in control. In other engagements he also did well.

Harold James returned to Nepal some fifty years after the war in search of his brave Lance Naik, after many attempts to track Sherbahadur down a meeting was finally arranged in 1992. Sherbahadur used to travel to collect his British Army pension from the depot in Pokhara. I will leave Harold James to describe their emotional reunion, held with the beautiful Annapura mountain range as a backdrop to the meeting:

"Coming face to face with someone after fifty years, especially as we had once shared a very dangerous episode in our lives, was a strange experience. Seeing Sherbahdur in his traditional Nepali clothes and so much older, was like meeting a complete stranger. But quite suddenly as he grasped my hand in his, the years seemed to rush back and his face took on that somewhat cheeky look I remembered so well, and in particular I could recall how his eyes crinkled up at the sides.

So we talked as old friends do, although he did most of the talking as we relived those desperate moments in the Burmese jungle. His recollections of the Chindits and the actions of column 3 were almost the same as mine. It seemed as if the impression made on our minds had been equally strong, a passage of time quite impossible to ever erase. There were sad moments too when we spoke of those who had died that year. And eventually the all too sad moment when we finally had to say goodbye. Sherbahadur then grasped my hand fiercely once more and implored me to come back and visit him again the following year."

Below is a photograph of part of Face panel 57 from the Rangoon Memorial in Taukkyan War Cemetery. It shows the name of Jemadar Andaram Gurung (amongst others), the young Gurkha officer who fought alongside Harold throughout the expedition in 1943. Although Andaram had managed to escape back across the Chindwin River in 1943, he sadly died from the ravages of malaria in June that same year.

Seen below is a Roll of Honour for the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles who died or were wounded during WW2 in Burma. This includes the men who perished whilst participating in Operation Longcloth, but also includes those who died in the Arakan in 1944 and beyond. Because of the obvious difficulties in successfully researching Gurkha soldiers and their exploits during these campaigns, I have decided to include all the following names, so as not to miss any potential Longcloth casualty or participant. I hope you will understand this decision and the reason for making it. I also realise that the roll below will not include all the men from the battalion who died from wounds or disease in the years that followed the war, or who were captured by the Japanese and died as POW's.

I would like to thank everyone who has helped in any way towards the story of the 3/2 Gurkha Rilfes in 1943 and the ultimate collation of this Roll of Honour. I would also like to thank Chris Peterson, JP Cross and Enes Smajic in particular and of course Tony B. for the photographs of the Gurkha memorials.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Seen above are photographs of Faces 57 and 58 of the Rangoon Memorial as found in the grounds of Taukkyan War Cemetery, which is situated on the outskirts of Rangoon. These are the panels which show the names of the men from 3/2 Gurkha Rifles who lost their lives whilst fighting in the Burma campaign. The memorial itself is dedicated to the casualties from the campaign who were lost with no known grave and contains over 26,000 inscriptions. It is a stunningly powerful piece of architecture and is the central focus of the cemetery at Taukkyan. Thanks as always to Tony B. for the magnificent photographs of the memorial panels.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2012.