Alec McKay Gibson

On the 30th March 1943 the officers of Column 3 gathered round their leader Major Mike Calvert as he toasted their commendable efforts during operation Longcloth. With that message still ringing in their ears the men moved off in their designated dispersal groups, hoping to meet each other again on the western banks of the Chindwin River.

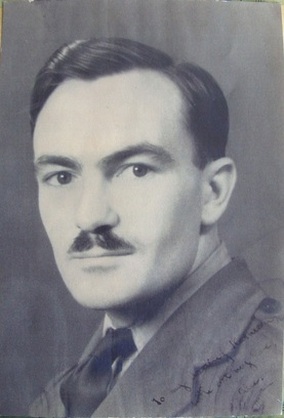

Alec Gibson (pictured left) had been Calvert's Administration and Cipher Officer on the operation and now leading a dispersal group alongside Ken Gourlie of the Burma Rifles marched directly west for toward the Irrawaddy River. He and Gourlie were not to get far.

Weak with dysentery and starving hungry Alec walked into a village called Taungang near the railway town of Wuntho. Instead of receiving food and the help he needed from the Burmese, he was arrested by them and held captive until the Japanese were called to take him away. On the 26th April 1943 Lieutenant Gibson became a Japanese prisoner of war and would spend the next two years a POW in Rangoon Jail. Ken Gourlie was also captured and although starting his time as a POW in Rangoon, was soon moved across to Changi Jail in Singapore, along with a small group of other Chindit officers, the reason for this is unknown.

No news or confirmation that Alec Gibson was indeed a prisoner in Japanese hands reached Allied lines until early July 1944. At this time a group of 3/2 Gurkha Riflemen who had succeeded in escaping their own incarceration by the Japanese reported that they had seen "Gibson sahib" in one of the POW Camps. One of the Gurkha personnel to give information about Lieutenant Gibson and his status as a POW was Rifleman Tekbahadur Rai, also formerly of Column 3 and who had been held at both the the Katha and Maymyo Camps.

Alec Gibson (pictured left) had been Calvert's Administration and Cipher Officer on the operation and now leading a dispersal group alongside Ken Gourlie of the Burma Rifles marched directly west for toward the Irrawaddy River. He and Gourlie were not to get far.

Weak with dysentery and starving hungry Alec walked into a village called Taungang near the railway town of Wuntho. Instead of receiving food and the help he needed from the Burmese, he was arrested by them and held captive until the Japanese were called to take him away. On the 26th April 1943 Lieutenant Gibson became a Japanese prisoner of war and would spend the next two years a POW in Rangoon Jail. Ken Gourlie was also captured and although starting his time as a POW in Rangoon, was soon moved across to Changi Jail in Singapore, along with a small group of other Chindit officers, the reason for this is unknown.

No news or confirmation that Alec Gibson was indeed a prisoner in Japanese hands reached Allied lines until early July 1944. At this time a group of 3/2 Gurkha Riflemen who had succeeded in escaping their own incarceration by the Japanese reported that they had seen "Gibson sahib" in one of the POW Camps. One of the Gurkha personnel to give information about Lieutenant Gibson and his status as a POW was Rifleman Tekbahadur Rai, also formerly of Column 3 and who had been held at both the the Katha and Maymyo Camps.

I was extremely fortunate to make contact with Alec back in 2009. One of the veterans from the trip to Burma in March 2008, Tom Webb, was a friend of Alec's from the war and it was he who put in a good word on my behalf. Alec has always been very kind when answering my questions and queries in regard to the Chindit operation of 1943.

I think it is true to say that he was very pleasantly surprised by the amount of information that I was able to uncover in regard to his and the other men's time, both on the operation and more so whilst POW.

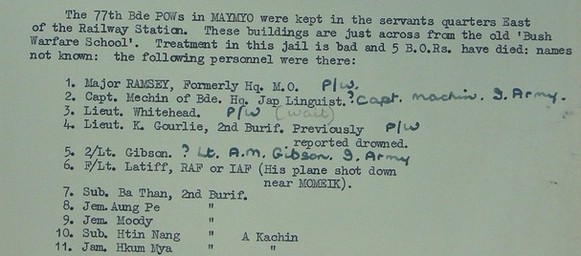

An example of such a document can be seen here (right). It is a report from the Kachin Levies underground movement (local tribesman trained and armed by Allied forces) stating who had recently been captured and sent to the Maymyo transitory POW camp. As you can see it includes Alec as an inmate at the time and his fellow Column 3 officer Ken Gourlay. Ken had fortunately turned up at Maymyo having previously believed to have drowned.

When I finally discovered what in essence had happened to my Grandfather in 1943, I sent the run down of the story to Alec, this is what he wrote in reply:

"Many thanks for your letter and enclosures. I am amazed at the amount of detail you have managed to dig out, congratulations. I had no idea that these documents even existed. It must have been very sad for you to learn all these details about your grandfather, you must however be very proud of him. It seems quite clear to me that he, and his comrades stayed behind because they felt that they were holding up the rest of the group. We all knew that, if we could not keep up with the rest of the column, we would have to be left behind. I can appreciate exactly what your grandfather was thinking at that time. The reason why I was captured was because I was starving and suffering from acute dysentery, if I had not walked into that village to get food and drink, then I would have died in the jungle. I at least was lucky enough to survive and have lived to a ripe old age."

I think it is true to say that he was very pleasantly surprised by the amount of information that I was able to uncover in regard to his and the other men's time, both on the operation and more so whilst POW.

An example of such a document can be seen here (right). It is a report from the Kachin Levies underground movement (local tribesman trained and armed by Allied forces) stating who had recently been captured and sent to the Maymyo transitory POW camp. As you can see it includes Alec as an inmate at the time and his fellow Column 3 officer Ken Gourlay. Ken had fortunately turned up at Maymyo having previously believed to have drowned.

When I finally discovered what in essence had happened to my Grandfather in 1943, I sent the run down of the story to Alec, this is what he wrote in reply:

"Many thanks for your letter and enclosures. I am amazed at the amount of detail you have managed to dig out, congratulations. I had no idea that these documents even existed. It must have been very sad for you to learn all these details about your grandfather, you must however be very proud of him. It seems quite clear to me that he, and his comrades stayed behind because they felt that they were holding up the rest of the group. We all knew that, if we could not keep up with the rest of the column, we would have to be left behind. I can appreciate exactly what your grandfather was thinking at that time. The reason why I was captured was because I was starving and suffering from acute dysentery, if I had not walked into that village to get food and drink, then I would have died in the jungle. I at least was lucky enough to survive and have lived to a ripe old age."

Here is the Japanese index card of Alec Gibson showing all his details for his time as a prisoner of war. It shows the date of capture as 28th April 1943, that he was captured at Taungang and that his previous occupation was a clerk.

Alec sent me a copy of his memoirs which explain his POW experience, it is entitled a Guest of the Emperor:

“Missing from April 4th-last seen swimming the Irrawaddy.” That was the news given to my parents in July 1943 by Lt. McKenzie of the 3/2nd Gurkha Rifles, who had managed to return to India from the first Chindit operation. My parents had no further news of me until I was reported “recovered from the enemy on April 30th 1945."

Following Wingate’s dispersal order we were trapped on the East side of the Irrawaddy, my party was unable to find boats, so swimming was the only alternative. After two abortive attempts I found myself alone with one Gurkha when we were jumped by eight Burmese Independent Army soldiers who tied us up and dragged us to the nearest Jap outpost some 5 miles away.

When initially interrogated by a Japanese Captain who spoke little English, I refused to answer and had a sword stuck at my throat! I thought that was to be my end, but managed to survive the ordeal with very evasive or completely inaccurate answers. Later I was taken by train, with many other prisoners, to Maymyo near Mandalay. Our hands were tied and 26 men were crammed into a railway wagon meant to accommodate only four cattle. At the Maymyo camp we had to learn Japanese drill: commands were shouted to us in Japanese and we were expected to understand them. If we got the drill wrong then we were knocked down with rifle butts, pick handles or bamboo canes. We managed to learn it in about two days. I was again interrogated and beaten if my answers were unsatisfactory. Both officers and men were up at dawn and made to work on various jobs till dusk. We all had to go and collect our food, two meals a day of rice and vegetable stew.

As a deliberate policy of humiliation we were lined up at least once per day and subjected to considerable face slapping by the Jap guards. Every now and again a prisoner would be called out for interrogation and you knew that you would undergo considerable punishment before you got back again. At night and during air-raids we were locked up, four to a wooden hut about the size of a bathing hut back home. There was a small oil drum inside to use as a latrine, this had to be emptied by one of the four each morning.

At this camp I met one of the Gurkha Subadars wearing the armband with the Jap Rising Sun the sign of the Indian National Army. I asked him how he could do this and he replied “Don’t worry Sahib- I have plans to get out of here.” I heard later that after training with the Japs he and the rest of the Gurkhas were given arms and sent to the front, here they promptly killed the Japs with them and went straight across to the Allied troops.

After several weeks at Maymyo we were transported by train to Rangoon, once again tied up and in cattle trucks. On arrival we were marched to what was previously Rangoon Central Jail, and placed into the solitary confinement block. These cells were about 9 Feet Square with one small window, dark and gloomy, with only the stone floor to sleep on! We were given one blanket each. The guards patrolled the block and we were not supposed to talk to each other, any breach being punished by a beating. Food was brought to us in the morning and evening by one of the British POW’s in the jail. We were only taken out for interrogation. By this time we had all agreed to give up various pieces of misleading information, this we hoped would save us from further torture and punishment. The difficulty was remembering what one had said previously and I nearly got caught out on two occasions. I was in solitary for only a few weeks but some prisoners spent months there.

Alec sent me a copy of his memoirs which explain his POW experience, it is entitled a Guest of the Emperor:

“Missing from April 4th-last seen swimming the Irrawaddy.” That was the news given to my parents in July 1943 by Lt. McKenzie of the 3/2nd Gurkha Rifles, who had managed to return to India from the first Chindit operation. My parents had no further news of me until I was reported “recovered from the enemy on April 30th 1945."

Following Wingate’s dispersal order we were trapped on the East side of the Irrawaddy, my party was unable to find boats, so swimming was the only alternative. After two abortive attempts I found myself alone with one Gurkha when we were jumped by eight Burmese Independent Army soldiers who tied us up and dragged us to the nearest Jap outpost some 5 miles away.

When initially interrogated by a Japanese Captain who spoke little English, I refused to answer and had a sword stuck at my throat! I thought that was to be my end, but managed to survive the ordeal with very evasive or completely inaccurate answers. Later I was taken by train, with many other prisoners, to Maymyo near Mandalay. Our hands were tied and 26 men were crammed into a railway wagon meant to accommodate only four cattle. At the Maymyo camp we had to learn Japanese drill: commands were shouted to us in Japanese and we were expected to understand them. If we got the drill wrong then we were knocked down with rifle butts, pick handles or bamboo canes. We managed to learn it in about two days. I was again interrogated and beaten if my answers were unsatisfactory. Both officers and men were up at dawn and made to work on various jobs till dusk. We all had to go and collect our food, two meals a day of rice and vegetable stew.

As a deliberate policy of humiliation we were lined up at least once per day and subjected to considerable face slapping by the Jap guards. Every now and again a prisoner would be called out for interrogation and you knew that you would undergo considerable punishment before you got back again. At night and during air-raids we were locked up, four to a wooden hut about the size of a bathing hut back home. There was a small oil drum inside to use as a latrine, this had to be emptied by one of the four each morning.

At this camp I met one of the Gurkha Subadars wearing the armband with the Jap Rising Sun the sign of the Indian National Army. I asked him how he could do this and he replied “Don’t worry Sahib- I have plans to get out of here.” I heard later that after training with the Japs he and the rest of the Gurkhas were given arms and sent to the front, here they promptly killed the Japs with them and went straight across to the Allied troops.

After several weeks at Maymyo we were transported by train to Rangoon, once again tied up and in cattle trucks. On arrival we were marched to what was previously Rangoon Central Jail, and placed into the solitary confinement block. These cells were about 9 Feet Square with one small window, dark and gloomy, with only the stone floor to sleep on! We were given one blanket each. The guards patrolled the block and we were not supposed to talk to each other, any breach being punished by a beating. Food was brought to us in the morning and evening by one of the British POW’s in the jail. We were only taken out for interrogation. By this time we had all agreed to give up various pieces of misleading information, this we hoped would save us from further torture and punishment. The difficulty was remembering what one had said previously and I nearly got caught out on two occasions. I was in solitary for only a few weeks but some prisoners spent months there.

Pictured to the right is Rangoon Jail taken from an air reconnaissance plane in 1945. You can just make out the words 'Japs Gone' on the roof of the block building at seven o'clock.

Alec Gibson continues his story:

Then the day came when I was transferred to one of the open blocks. Rangoon Jail, built during colonial times, resembled a large wheel with a well and water tower as the hub and the main blocks radiating out from there like the spokes of a wheel. The blocks were contained in compounds made of seven-foot high brick walls and high iron barred fences at the centre and outer perimeter. The guards patrolling the centre and the hub could see the whole compound. Whenever a guard appeared the nearest person had to call the whole group to attention and all had to bow to the guard. Failure to do so incurred an immediate beating. The blocks were two-storied buildings, each floor containing five rooms with long barred windows down to floor level on one side, and floor to ceiling bars on the whole of the other side, which opened onto a corridor running the length of the block. Stone steps at both ends of the block led to the upper corridor.

In the compound was a long concrete trough containing water and a basha containing lots of ammunition boxes used as latrines. These had to be emptied every day by the Sanitary Squad. Apart from the solitary confinement block and the punishment block, two of the other blocks were occupied by British and American prisoners, two more by Indians, one by Chinese and one by American Airmen in long-term solitary confinement.

In number 3 block where I spent most of my time, the officers were in two rooms on the upper floor, about 26 of us in each room. The other ranks occupied the other rooms with between 30 and 40 POW’s in each. There was no glass in any windows so the Monsoon rains just pored in, but at least this did cool things down. We all had to sleep on the floor with just our blanket and using what you could as a pillow. The Japanese had taken all we possessed; leaving us with the tattered clothes we stood up in. No more clothing was issued; we had to patch whatever we had with materials stolen while out on working parties. Most of the time we wore only a fandoshi or loincloth made from a rectangle of cloth and a piece of string. As our boots fell apart we went barefoot, our feet soon got pretty tough.

Things settled down into a regular routine, up at dawn for roll call, numbering in Japanese, a brief cup of tea (so called), then detailed off for working parties as notified from the previous day. Every fit person including officers had to work. Working parties consisted of one officer in charge, 15 to 20 men and two or three Jap guards; there were sometimes work parties made up entirely of officers. We marched out of the jail taking with us rice and vegetables for our midday meal, plus all the tools needed for the job we were on. One man would cook the meal while the rest of us were employed as slave labour.

We worked on the railway, unloaded rice and stores at the docks, helped to build an underground headquarters for the Japs, repaired roads and bridges, dug up unexploded bombs and cleared up after air-raid damage. Sometimes we had to work further away such as Mingladon airfield. On these days we were transported in trucks. If anything went wrong, the man concerned and the officer in charge were both beaten up. At dusk we returned to the jail where our cooks would have a meal ready for us. Then after another roll call we were shut up for the night, there were no lights in the blocks.

On Sundays we were usually allowed a rest day, when there were no outside working parties. Sometimes we played football or netball, always being careful not to injure ourselves. On the odd occasion we were allowed to have a concert party, at which I used to sing some of the popular songs, accompanied by a band consisting of one mouthorgan, two men on paper combs and another emulating a trumpet. The Japs used to come along to watch as well. We had no cigarettes but used to make some from Burmese cheroots, rolled in newspaper and stuck down with rice. No Red Cross parcels were ever received and only twice did we get any mail, most of us had never been notified as POW’s anyway. No attempts to escape were made, although it would have been easy enough to get away. Apart from being unfit for such efforts; the chances of travelling hundreds of miles trying to look Indian or Burmese were pretty slim.

For those not fit enough to work outside there were inside working parties for sanitary duties, sick bay orderlies, gardening parties to grow vegetables, cleaning the cell blocks and collecting and delivering food and firewood. All this was interspersed with the need to stop and come to attention and bow every time a guard came near. Some men were permanently on cooking duties and did their best with the rations we were given. This was basically rice and vegetables with occasional meat scrounged from outside, or maybe a pigeon caught on the inside! Sometimes we had a sort of porridge made from ground up husks of rice. It tasted horrible but contained vitamin B1 and was a great help against beriberi. We also had tea, or rather hot water with a few leaves thrown in, no milk and no sugar.

The odd thing about working parties was that the men were paid, albeit only 10 cents (about two pence) per day. Officers were paid a salary once a month, for my rank this amounted to 160 rupees about £12. However deductions were made for board and lodging, contribution to Japanese Defence Bonds and various other items. I actually signed for and received 10 rupees each month, half of which went to fund extra food for sick bay.

We were able to buy small quantities of sugar, eggs, sometimes meat, and Burmese cheroots through the Jap Quartermaster. These items became scarcer and more expensive as time went by. On outside work parties we had become accomplished thieves and stole anything we could lay our hands on. In spite of a search at the guard room when we returned, we used to smuggle in meat, eggs, dried fish, sugar, books and English language newspapers. Sometimes we were caught and severely punished, often beaten or made to stand to attention in the hot sun for hours, but it was worth it.

The things which kept us going were the conviction that we would win the war, a great sense of humour and a determination to outwit the Jap at every opportunity. The last was a particularly difficult path to tread. Any deliberate wrong doing incurred immediate and severe punishment, so everything had to look like an accident or show the British as being incompetent idiots. The following stories indicate some of the plots in which I was involved, each needing careful coordination between officer and the men. We were unloading rice from barges at Rangoon Docks, carrying it in large jute sacks. Holes were made in the bottom of these sacks so that as we staggered to the warehouse we left a trail of rice along the dockside. Before the Japs could intervene I complained to them that all the sacks were no good. When unloading 40 gallon drums of petrol we made sure that each drum was dumped heavily on to one of the sharp stones we had placed on the dockside-the whole place reeked of fuel. On another occasion a crate of vital fuses for the Japanese shells fell overboard form the ship in spite of our valiant efforts to save it. All successful attempts were of course a great boost to morale.

Alec Gibson continues his story:

Then the day came when I was transferred to one of the open blocks. Rangoon Jail, built during colonial times, resembled a large wheel with a well and water tower as the hub and the main blocks radiating out from there like the spokes of a wheel. The blocks were contained in compounds made of seven-foot high brick walls and high iron barred fences at the centre and outer perimeter. The guards patrolling the centre and the hub could see the whole compound. Whenever a guard appeared the nearest person had to call the whole group to attention and all had to bow to the guard. Failure to do so incurred an immediate beating. The blocks were two-storied buildings, each floor containing five rooms with long barred windows down to floor level on one side, and floor to ceiling bars on the whole of the other side, which opened onto a corridor running the length of the block. Stone steps at both ends of the block led to the upper corridor.

In the compound was a long concrete trough containing water and a basha containing lots of ammunition boxes used as latrines. These had to be emptied every day by the Sanitary Squad. Apart from the solitary confinement block and the punishment block, two of the other blocks were occupied by British and American prisoners, two more by Indians, one by Chinese and one by American Airmen in long-term solitary confinement.

In number 3 block where I spent most of my time, the officers were in two rooms on the upper floor, about 26 of us in each room. The other ranks occupied the other rooms with between 30 and 40 POW’s in each. There was no glass in any windows so the Monsoon rains just pored in, but at least this did cool things down. We all had to sleep on the floor with just our blanket and using what you could as a pillow. The Japanese had taken all we possessed; leaving us with the tattered clothes we stood up in. No more clothing was issued; we had to patch whatever we had with materials stolen while out on working parties. Most of the time we wore only a fandoshi or loincloth made from a rectangle of cloth and a piece of string. As our boots fell apart we went barefoot, our feet soon got pretty tough.

Things settled down into a regular routine, up at dawn for roll call, numbering in Japanese, a brief cup of tea (so called), then detailed off for working parties as notified from the previous day. Every fit person including officers had to work. Working parties consisted of one officer in charge, 15 to 20 men and two or three Jap guards; there were sometimes work parties made up entirely of officers. We marched out of the jail taking with us rice and vegetables for our midday meal, plus all the tools needed for the job we were on. One man would cook the meal while the rest of us were employed as slave labour.

We worked on the railway, unloaded rice and stores at the docks, helped to build an underground headquarters for the Japs, repaired roads and bridges, dug up unexploded bombs and cleared up after air-raid damage. Sometimes we had to work further away such as Mingladon airfield. On these days we were transported in trucks. If anything went wrong, the man concerned and the officer in charge were both beaten up. At dusk we returned to the jail where our cooks would have a meal ready for us. Then after another roll call we were shut up for the night, there were no lights in the blocks.

On Sundays we were usually allowed a rest day, when there were no outside working parties. Sometimes we played football or netball, always being careful not to injure ourselves. On the odd occasion we were allowed to have a concert party, at which I used to sing some of the popular songs, accompanied by a band consisting of one mouthorgan, two men on paper combs and another emulating a trumpet. The Japs used to come along to watch as well. We had no cigarettes but used to make some from Burmese cheroots, rolled in newspaper and stuck down with rice. No Red Cross parcels were ever received and only twice did we get any mail, most of us had never been notified as POW’s anyway. No attempts to escape were made, although it would have been easy enough to get away. Apart from being unfit for such efforts; the chances of travelling hundreds of miles trying to look Indian or Burmese were pretty slim.

For those not fit enough to work outside there were inside working parties for sanitary duties, sick bay orderlies, gardening parties to grow vegetables, cleaning the cell blocks and collecting and delivering food and firewood. All this was interspersed with the need to stop and come to attention and bow every time a guard came near. Some men were permanently on cooking duties and did their best with the rations we were given. This was basically rice and vegetables with occasional meat scrounged from outside, or maybe a pigeon caught on the inside! Sometimes we had a sort of porridge made from ground up husks of rice. It tasted horrible but contained vitamin B1 and was a great help against beriberi. We also had tea, or rather hot water with a few leaves thrown in, no milk and no sugar.

The odd thing about working parties was that the men were paid, albeit only 10 cents (about two pence) per day. Officers were paid a salary once a month, for my rank this amounted to 160 rupees about £12. However deductions were made for board and lodging, contribution to Japanese Defence Bonds and various other items. I actually signed for and received 10 rupees each month, half of which went to fund extra food for sick bay.

We were able to buy small quantities of sugar, eggs, sometimes meat, and Burmese cheroots through the Jap Quartermaster. These items became scarcer and more expensive as time went by. On outside work parties we had become accomplished thieves and stole anything we could lay our hands on. In spite of a search at the guard room when we returned, we used to smuggle in meat, eggs, dried fish, sugar, books and English language newspapers. Sometimes we were caught and severely punished, often beaten or made to stand to attention in the hot sun for hours, but it was worth it.

The things which kept us going were the conviction that we would win the war, a great sense of humour and a determination to outwit the Jap at every opportunity. The last was a particularly difficult path to tread. Any deliberate wrong doing incurred immediate and severe punishment, so everything had to look like an accident or show the British as being incompetent idiots. The following stories indicate some of the plots in which I was involved, each needing careful coordination between officer and the men. We were unloading rice from barges at Rangoon Docks, carrying it in large jute sacks. Holes were made in the bottom of these sacks so that as we staggered to the warehouse we left a trail of rice along the dockside. Before the Japs could intervene I complained to them that all the sacks were no good. When unloading 40 gallon drums of petrol we made sure that each drum was dumped heavily on to one of the sharp stones we had placed on the dockside-the whole place reeked of fuel. On another occasion a crate of vital fuses for the Japanese shells fell overboard form the ship in spite of our valiant efforts to save it. All successful attempts were of course a great boost to morale.

Above is a panoramic view of Rangoon War Cemetery taken from the roof of the main entrance.

(Photo courtesy of Tony B nt872b(at)hotmail.com).

It is here that the Chindits who died as POW's in Rangoon Jail are remembered. In 1985 Alec Gibson travelled back to Burma on the Royal British Legion War Widows pilgrimage. He says in one of his letters to me that he found the experience very moving, especially his conversations with the widows and trying to console them. He remembered one lady who asked him about the men who had died in the jail and how they were buried. He told her "When a man died he was taken from the jail to a burial place with an escort of six men, (some of whom would be his friends) and a British officer in charge. This group was accompanied by two Japanese guards. The body, covered with a tattered but recognisable Union Jack, was carried through the streets on a small hand cart by the escort. The grave was dug, a brief service was conducted including a text read from the bible by the officer, the body was then interred."

Alec's description of these events and his discussions with the widows is of great significance to me as my Nan was fortunate to travel out to Burma the very next year, I can only hope she received the same kindness and consideration.

Here is the remainder of his POW experiences:

The one thing that really worried us was being injured or becoming ill as medical treatment was non-existent. We had several medical Officers with us as prisoners but they had virtually nothing in the way of medicines or equipment. Jungle sores or ulcers were treated with copper sulphate crystals, dysentery with charcoal tablets, and beriberi with grain husks. Incredibly, two successful amputations were carried out with the crudest of instruments and no anaesthetics. Most of us suffered from ulcers, dysentery, beriberi, or dengue fever at sometime, but if became serious it was usually terminal. Two thirds of the complement of the camp died, and of the 210 captured Chindits from both expeditions 168 died of their wounds, diseases or malnutrition. Fourteen POW’s died when a stick of bombs from a crippled American bomber fell right across the jail.

One point I must mention is that, whilst we were treated as dirt as POW’s, the Japanese respected our dead. When a prisoner died he was taken to a burial ground outside the jail by a funeral party consisting of, a British Officer, six other ranks and two guards. His body was carried on small hand cart covered in a very tattered Union Jack. We dug a grave, buried the man, held a brief funeral service and put up a wooden cross. The position of each grave was plotted on a map by our senior officer. Once I was scheduled to take out a funeral party for one man on the following day, by the time I went there were five bodies to be buried. That burial ground is now an official War Cemetery (Rangoon War Cemetery), beautifully laid out, and on the Far East Pilgrimage 40 years later I was able to assure some of the War widows that at least their husbands had been given a proper burial.

Eventually in April 1945 the Japs decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 of us were classified as fit to march and on the 24th of April we marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and crippled. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, we were North of Pegu and nearing the Sittang Bridge when we ran into the 14th Army. The Jap Commandant left us in a village told us we were free and disappeared with the rest of the guards. We were in no-mans land with firing coming from all sides. That night we managed to contact our own troops, the West Yorkshires, and were released.

Copyright © Alec Gibson/Steve Fogden 2011.

(Photo courtesy of Tony B nt872b(at)hotmail.com).

It is here that the Chindits who died as POW's in Rangoon Jail are remembered. In 1985 Alec Gibson travelled back to Burma on the Royal British Legion War Widows pilgrimage. He says in one of his letters to me that he found the experience very moving, especially his conversations with the widows and trying to console them. He remembered one lady who asked him about the men who had died in the jail and how they were buried. He told her "When a man died he was taken from the jail to a burial place with an escort of six men, (some of whom would be his friends) and a British officer in charge. This group was accompanied by two Japanese guards. The body, covered with a tattered but recognisable Union Jack, was carried through the streets on a small hand cart by the escort. The grave was dug, a brief service was conducted including a text read from the bible by the officer, the body was then interred."

Alec's description of these events and his discussions with the widows is of great significance to me as my Nan was fortunate to travel out to Burma the very next year, I can only hope she received the same kindness and consideration.

Here is the remainder of his POW experiences:

The one thing that really worried us was being injured or becoming ill as medical treatment was non-existent. We had several medical Officers with us as prisoners but they had virtually nothing in the way of medicines or equipment. Jungle sores or ulcers were treated with copper sulphate crystals, dysentery with charcoal tablets, and beriberi with grain husks. Incredibly, two successful amputations were carried out with the crudest of instruments and no anaesthetics. Most of us suffered from ulcers, dysentery, beriberi, or dengue fever at sometime, but if became serious it was usually terminal. Two thirds of the complement of the camp died, and of the 210 captured Chindits from both expeditions 168 died of their wounds, diseases or malnutrition. Fourteen POW’s died when a stick of bombs from a crippled American bomber fell right across the jail.

One point I must mention is that, whilst we were treated as dirt as POW’s, the Japanese respected our dead. When a prisoner died he was taken to a burial ground outside the jail by a funeral party consisting of, a British Officer, six other ranks and two guards. His body was carried on small hand cart covered in a very tattered Union Jack. We dug a grave, buried the man, held a brief funeral service and put up a wooden cross. The position of each grave was plotted on a map by our senior officer. Once I was scheduled to take out a funeral party for one man on the following day, by the time I went there were five bodies to be buried. That burial ground is now an official War Cemetery (Rangoon War Cemetery), beautifully laid out, and on the Far East Pilgrimage 40 years later I was able to assure some of the War widows that at least their husbands had been given a proper burial.

Eventually in April 1945 the Japs decided to move as many POW’s as possible back to Japan via Thailand. Some 400 of us were classified as fit to march and on the 24th of April we marched out of the jail for the last time, leaving behind another 400 sick and crippled. After five gruelling days and having covered about 55 miles, we were North of Pegu and nearing the Sittang Bridge when we ran into the 14th Army. The Jap Commandant left us in a village told us we were free and disappeared with the rest of the guards. We were in no-mans land with firing coming from all sides. That night we managed to contact our own troops, the West Yorkshires, and were released.

Copyright © Alec Gibson/Steve Fogden 2011.