Bertie Castens' Secret Track

Herbert Castens, Katha 1942.

Herbert Castens, Katha 1942.

The Chindit operation of 1943 owed much to men such as Major Herbert Castens of General Staff Intelligence (Z) or Z Force as it became known. Castens, not only paved the way for the Chindit reconnaissance parties in late 1942, but had also informed Wingate of a secret track, which was used during the operation to bypass the Japanese garrisons stationed in the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment. Many of the men from Z Force and units just like them received recognition after the war for their brave and daring actions behind enemy lines. Without such men, the effectiveness of operations such as the first Chindit expedition would have been very much reduced, with bodies of troops moving blindly through territories held by the enemy and never knowing what they might encounter along the way.

Bernard Fergusson, in his many writings post war paid homage to these incredibly brave and resilient men:

In the course of the last war, I found myself serving with men of whose existence I had been only dimly aware. These were the British employees of the Burma firms, which had been engaged for three-quarters of a century in developing and handling the resources of that rich and beautiful country: timber, rice, mines, waterways and the like. By the time I came to know them, these men were all in uniform; but the characteristics which they had in common shone and shimmered through the anonymity which the donning of uniform sometimes involves.

They were all quite remarkably resourceful, and no wonder. I soon discovered that almost without exception they had lived up-country for long periods on their own. They had become accustomed in early youth to being self-sufficient, to taking major decisions without troubling their superiors, to dispensing rough medicine and even rougher justice, and to being, in short, responsible far beyond their years. They did not always take kindly to being bossed around by people like me.

In the book, ‘Wild Green Earth’, written about his exploits during the second Chindit expedition, Fergusson remembered more specifically, Herbert Castens:

Many and varied were our visitors at Aberdeen (Fergusson’s Brigade stronghold). Some were old friends. One was Major Bertie Castens, an intrepid British Forest Officer and an old ally of 1943. He had spent most of the period of the Japanese occupation wandering around the country with a wireless set, telling India what was going on. It was he who in 1943 had found for us the so-called ‘Secret Track’ which we used to slip through the Jap defences east of the Pinlebu Road. He came in one night by arrangement, with two companions, one a fine Anglo-Indian called Webster and the other a Kachin, all three in tattered uniforms.

Herbert Ernest Castens was the District Forestry Officer for the Katha Division of Northern Burma. He was an extremely tall and powerfully built man, weighing close to sixteen stone and sporting a large black beard. University educated, he possessed a forceful but well-mannered nature, however, once a point of view had been established Castens was a difficult man to persuade to the contrary.

His beard became somewhat of an issue in 1942 when he, like so many of his colleagues in the Forestry Commission joined the Armed Forces. Beards were against regulations and Castens was told to shave his off.

“Not on your life,” was his reply. “If I go back into Burma without it, none of the villagers will recognise me. Don’t you realise that this beard is my passport.” His statement was so forthright and convincing that the beard was allowed to stay.

Herbert was a well-loved character amongst the tribes people of the Katha region. In his role as District Officer he was known as a firm but fair man, who fully understood the customs and practices of the Burmese and adjusted the needs of the Commission to ensure good relations prevailed. It was for this reason that he was put in charge of the evacuation of Katha (situated on a branch line of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway on the west side of the Irrawaddy River) as the Japanese invasion swept across Burma in early 1942.

Having completed his mission and secured the safe passage of the majority of the inhabitants of Katha to the Assam Borders, Herbert then returned to his post for a few more days ensuring that there was nothing of value left behind for the Japanese to inherit. He eventually made his own way out of Burma in early May 1942, journeying for a time with General Stilwell of the United States Army.

Commissioned into the Indian Army with the service number EC9367, Castens made rapid progress through the ranks from 2nd Lieutenant in August 1942 to Temporary Major, with the new service number ABRO 15 by mid-1943. After reaching India in the summer months of 1942 he settled for a time in Calcutta and it was whilst living in this vibrant city that he learned of the plans to raise Z Force.

The head of Military Intelligence in Calcutta was Lieutenant-Colonel C.E. Gregory, formerly of the Royal Garwhal Rifles. Gregory, who had been attached to the civil police in India during the periods of unrest in Bengal and Orissa, was given the task of raising Z Force and recruiting suitable men to become the first ‘stay-behind’ agents. Herbert Castens was one of the first men he approached and together they built the unit up to its original strength of ten men.

The personnel that made up Z Force were given the nickname ‘The Johnnies.’ This comes from the breakdown of the colloquial description of the men who made up their number, namely, British Officer Johnnies. A fantastic book, sporting the same title and written by Lieutenant General, Sir Geoffrey Evans, provides the main resource for this story.

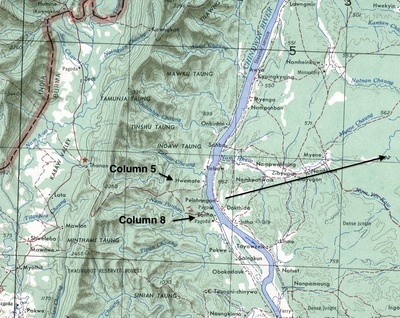

The men of Z Force worked together in pairs; Castens was teamed up with Major Freddy Webster and they were to patrol Z Force area No. 1. This was the area of their old stamping grounds in the Mansi Forest, between Homalin and Tonhe on the Chindwin, then out as far east as Katha. With this in mind, I wonder now whether it was a mere coincidence that when Wingate and his main force crossed the Chindwin in February 1943, it was at the village of Tonhe that the crossing was made.

From Evans' book, a quote that does well to describe the men of Z Force:

Although these ten men differed in appearance and background and each was an individualist, they shared certain attributes. All had a thorough knowledge of the jungle, its inhabitants and their language; all were tough and used to living on their own far from civilisation; all possessed courage of outstanding quality.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story, including photographs of some of the men mentioned. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Bernard Fergusson, in his many writings post war paid homage to these incredibly brave and resilient men:

In the course of the last war, I found myself serving with men of whose existence I had been only dimly aware. These were the British employees of the Burma firms, which had been engaged for three-quarters of a century in developing and handling the resources of that rich and beautiful country: timber, rice, mines, waterways and the like. By the time I came to know them, these men were all in uniform; but the characteristics which they had in common shone and shimmered through the anonymity which the donning of uniform sometimes involves.

They were all quite remarkably resourceful, and no wonder. I soon discovered that almost without exception they had lived up-country for long periods on their own. They had become accustomed in early youth to being self-sufficient, to taking major decisions without troubling their superiors, to dispensing rough medicine and even rougher justice, and to being, in short, responsible far beyond their years. They did not always take kindly to being bossed around by people like me.

In the book, ‘Wild Green Earth’, written about his exploits during the second Chindit expedition, Fergusson remembered more specifically, Herbert Castens:

Many and varied were our visitors at Aberdeen (Fergusson’s Brigade stronghold). Some were old friends. One was Major Bertie Castens, an intrepid British Forest Officer and an old ally of 1943. He had spent most of the period of the Japanese occupation wandering around the country with a wireless set, telling India what was going on. It was he who in 1943 had found for us the so-called ‘Secret Track’ which we used to slip through the Jap defences east of the Pinlebu Road. He came in one night by arrangement, with two companions, one a fine Anglo-Indian called Webster and the other a Kachin, all three in tattered uniforms.

Herbert Ernest Castens was the District Forestry Officer for the Katha Division of Northern Burma. He was an extremely tall and powerfully built man, weighing close to sixteen stone and sporting a large black beard. University educated, he possessed a forceful but well-mannered nature, however, once a point of view had been established Castens was a difficult man to persuade to the contrary.

His beard became somewhat of an issue in 1942 when he, like so many of his colleagues in the Forestry Commission joined the Armed Forces. Beards were against regulations and Castens was told to shave his off.

“Not on your life,” was his reply. “If I go back into Burma without it, none of the villagers will recognise me. Don’t you realise that this beard is my passport.” His statement was so forthright and convincing that the beard was allowed to stay.

Herbert was a well-loved character amongst the tribes people of the Katha region. In his role as District Officer he was known as a firm but fair man, who fully understood the customs and practices of the Burmese and adjusted the needs of the Commission to ensure good relations prevailed. It was for this reason that he was put in charge of the evacuation of Katha (situated on a branch line of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway on the west side of the Irrawaddy River) as the Japanese invasion swept across Burma in early 1942.

Having completed his mission and secured the safe passage of the majority of the inhabitants of Katha to the Assam Borders, Herbert then returned to his post for a few more days ensuring that there was nothing of value left behind for the Japanese to inherit. He eventually made his own way out of Burma in early May 1942, journeying for a time with General Stilwell of the United States Army.

Commissioned into the Indian Army with the service number EC9367, Castens made rapid progress through the ranks from 2nd Lieutenant in August 1942 to Temporary Major, with the new service number ABRO 15 by mid-1943. After reaching India in the summer months of 1942 he settled for a time in Calcutta and it was whilst living in this vibrant city that he learned of the plans to raise Z Force.

The head of Military Intelligence in Calcutta was Lieutenant-Colonel C.E. Gregory, formerly of the Royal Garwhal Rifles. Gregory, who had been attached to the civil police in India during the periods of unrest in Bengal and Orissa, was given the task of raising Z Force and recruiting suitable men to become the first ‘stay-behind’ agents. Herbert Castens was one of the first men he approached and together they built the unit up to its original strength of ten men.

The personnel that made up Z Force were given the nickname ‘The Johnnies.’ This comes from the breakdown of the colloquial description of the men who made up their number, namely, British Officer Johnnies. A fantastic book, sporting the same title and written by Lieutenant General, Sir Geoffrey Evans, provides the main resource for this story.

The men of Z Force worked together in pairs; Castens was teamed up with Major Freddy Webster and they were to patrol Z Force area No. 1. This was the area of their old stamping grounds in the Mansi Forest, between Homalin and Tonhe on the Chindwin, then out as far east as Katha. With this in mind, I wonder now whether it was a mere coincidence that when Wingate and his main force crossed the Chindwin in February 1943, it was at the village of Tonhe that the crossing was made.

From Evans' book, a quote that does well to describe the men of Z Force:

Although these ten men differed in appearance and background and each was an individualist, they shared certain attributes. All had a thorough knowledge of the jungle, its inhabitants and their language; all were tough and used to living on their own far from civilisation; all possessed courage of outstanding quality.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story, including photographs of some of the men mentioned. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Each Z Force group was made up of two officers and eight Other Ranks. Castens and Webster opted to make up their numbers with men from the Kachin tribes, with the view that they would have a better understanding of the area in which they would be working. The other Z Force units similarly chose their men from the areas in which they were patrolling, for example No. 5 Group led by Major C.G. 'Micky' Merton in the Chin Hills.

Castens decided that whilst on active patrol, his group would live and camp away from local villages. Other Z Force units would sometimes live within the community of a local village for a time, but this occurred mainly in areas where there were little or no enemy presence and where the villagers themselves could be fairly well trusted.

The first Z Force patrol began on the 7th August 1942. Castens and Webster collected their men and supplies together at Imphal and moved down to their operational area. In the area west of the Chindwin, they passed through a V Force patrol that guided them safely to the river bank and updated them on recent enemy positions on the far side of the river.

On this first patrol, Z Force units carried everything they required for their time in the jungle in rucksacks. At times these packs could weigh over fifty pounds. They also carried with them their radio, which was by far the most precious and important item they possessed. Rations came in the form of tinned and packeted goods, but the plan was always to purchase rice and other staples from local villages in their operational area. Eventually, most Z Force units had built up large supply dumps which were well concealed in jungle hideouts and stored enough food and equipment to last many weeks.

In order to purchase food and other items from the local tribes, Castens and the other Z Force units were issued silver rupees, gold sovereigns and in some cases opium. Silver rupees were very much welcomed by the Burmese, who had for many months suffered payment for goods and services by the Japanese with their almost worthless paper bank notes. Opium addiction was common place in Burma and could be used in place of hard currency when needed. The gold sovereigns however, proved to be a mistake, as villagers caught holding such wealth were almost always rigorously interrogated by the Japanese and brought the whole village under suspicion.

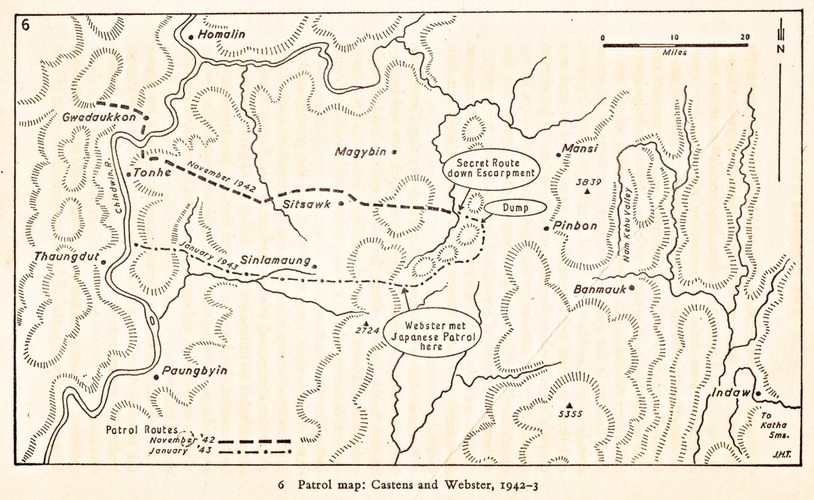

Major Castens initial reconnaissance patrol ended in November and he and his men returned to Imphal for a recuperation and refitting period. During his time back in Assam, Castens was debriefed by the Z Force command and was met by Brigadier Orde Wingate, who was keen to know what was going on over the other side of the Chindwin. The information Castens was able to give Wingate proved invaluable and this included the details of a hidden track which would eventually bring its users out from the mountain escarpment west of Mansi.

Wingate used this track to avoid enemy patrols in February 1943, leading part of his Chindit Brigade through the trail from the Sitsawk area and emerging again, close to the Burmese town of Pinbon. One of the British multeers from Wingate’s own Brigade Head Quarters remembered this journey and remarked:

“The trail was a bugger to clear through, but it was worth it to avoid the Japs.”

During his second patrol, Castens used the secret track on many occasions; he eventually placed his largest supply dump at the eastern end of the track, close to the village of Mansi. He and Webster had developed a good relationship with the headmen of the local area and had increased their supply of rice and other foodstuffs from these villages.

Another local man who helped Castens and Webster was Maung Thaung, who lived on his small holding close to the village of Sitsawk. Maung Thaung had known Freddy Webster from his days in the Forestry Commission and been assisted by Webster in an official capacity when his previous land was declared part of a reserved area for potential logging. Knowing that they could trust him implicitly, Maung Thaung became their main contact and scout in the area.

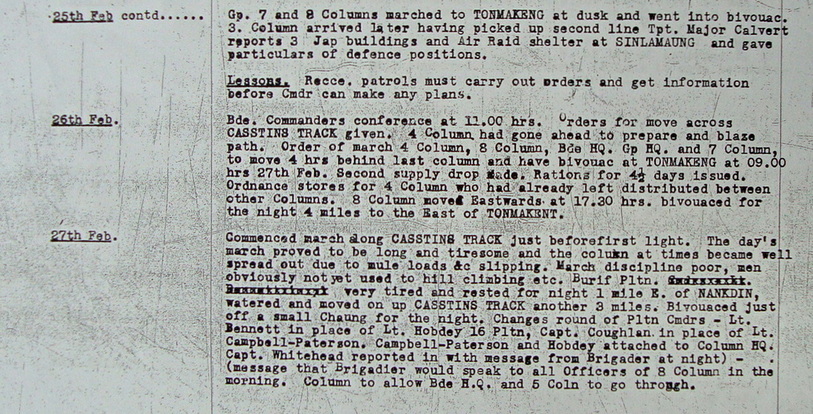

Seen below is a map of the Operational Area for Z Force No. 1 Group and the mention of Castens Track in the War diary for 8 Column in 1943. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Castens decided that whilst on active patrol, his group would live and camp away from local villages. Other Z Force units would sometimes live within the community of a local village for a time, but this occurred mainly in areas where there were little or no enemy presence and where the villagers themselves could be fairly well trusted.

The first Z Force patrol began on the 7th August 1942. Castens and Webster collected their men and supplies together at Imphal and moved down to their operational area. In the area west of the Chindwin, they passed through a V Force patrol that guided them safely to the river bank and updated them on recent enemy positions on the far side of the river.

On this first patrol, Z Force units carried everything they required for their time in the jungle in rucksacks. At times these packs could weigh over fifty pounds. They also carried with them their radio, which was by far the most precious and important item they possessed. Rations came in the form of tinned and packeted goods, but the plan was always to purchase rice and other staples from local villages in their operational area. Eventually, most Z Force units had built up large supply dumps which were well concealed in jungle hideouts and stored enough food and equipment to last many weeks.

In order to purchase food and other items from the local tribes, Castens and the other Z Force units were issued silver rupees, gold sovereigns and in some cases opium. Silver rupees were very much welcomed by the Burmese, who had for many months suffered payment for goods and services by the Japanese with their almost worthless paper bank notes. Opium addiction was common place in Burma and could be used in place of hard currency when needed. The gold sovereigns however, proved to be a mistake, as villagers caught holding such wealth were almost always rigorously interrogated by the Japanese and brought the whole village under suspicion.

Major Castens initial reconnaissance patrol ended in November and he and his men returned to Imphal for a recuperation and refitting period. During his time back in Assam, Castens was debriefed by the Z Force command and was met by Brigadier Orde Wingate, who was keen to know what was going on over the other side of the Chindwin. The information Castens was able to give Wingate proved invaluable and this included the details of a hidden track which would eventually bring its users out from the mountain escarpment west of Mansi.

Wingate used this track to avoid enemy patrols in February 1943, leading part of his Chindit Brigade through the trail from the Sitsawk area and emerging again, close to the Burmese town of Pinbon. One of the British multeers from Wingate’s own Brigade Head Quarters remembered this journey and remarked:

“The trail was a bugger to clear through, but it was worth it to avoid the Japs.”

During his second patrol, Castens used the secret track on many occasions; he eventually placed his largest supply dump at the eastern end of the track, close to the village of Mansi. He and Webster had developed a good relationship with the headmen of the local area and had increased their supply of rice and other foodstuffs from these villages.

Another local man who helped Castens and Webster was Maung Thaung, who lived on his small holding close to the village of Sitsawk. Maung Thaung had known Freddy Webster from his days in the Forestry Commission and been assisted by Webster in an official capacity when his previous land was declared part of a reserved area for potential logging. Knowing that they could trust him implicitly, Maung Thaung became their main contact and scout in the area.

Seen below is a map of the Operational Area for Z Force No. 1 Group and the mention of Castens Track in the War diary for 8 Column in 1943. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

The third Z Force patrols headed out in January 1943, this was just prior to the commencement of Operation Longcloth. Castens crossed the Chindwin close to Tonhe village and immediately found a large Japanese garrison present at Banmauk. This information was radioed back to HQ and Wingate was warned of their presence and the RAF was called in to bomb the town. Meanwhile, Z Force group No. 2, led by Major Richard W. Wood and Major J.R. Stewart had moved into their area covering the villages of Pinlebu, Wuntho and Pantha. Their intelligence came back to rear base, signalling no significant enemy activity in the area, but that the Burmese living there felt squarely between a rock and a hard place, having to deal with both British and Japanese patrols on a regular basis.

Pinlebu, Pantha and Wuntho would all be subjected to aerial attacks over the following weeks and it can be no coincidence that Wingate investigated all three places over the course of his expedition. Z Force unit No. 3, active closer to the Chindwin River, but slightly further south than the other groups, were also able to assist Brigadier Wingate in early 1943. Major J.G. Middleton had been patrolling in the Kabaw Valley with Lieutenant-Colonel G.W. Parker and had good intelligence for both Wingate and Mike Calvert about enemy positions at Kalewa and Mawlaik.

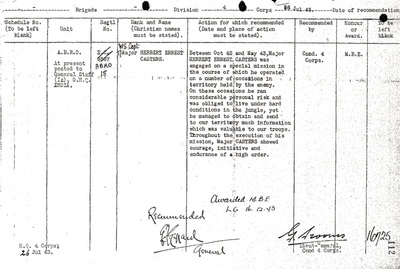

Major Castens and the other Z Force parties returned to India in May 1943, just before the start of the monsoon. Herbert Castens was awarded the M.B.E. in July for his valiant work behind enemy lines, including his invaluable reconnaissance on behalf of the Chindits.

Lieutenant-General G. A. P. Scoones, the then Commander of 4th Corps had this to say about the efforts of Z Force that year:

Now that the monsoon has arrived and the G.S.I.z forward parties, which have been operating in 4th Corps, are coming back, I would like at this juncture to express my appreciation of the work which these parties have been doing.

I know well enough the hard conditions under which they have been living and operating for weeks on end. I know too the strain that the work imposes on all members of the parties, it has been described to my staff by an officer (not a member of one of the forward parties) as similar to hunting a wounded tiger.

In spite, however, of the many difficulties with which the parties have had to contend, they have managed to provide a flow of information which has been most valuable to me and has, I think, enabled us to inflict a considerable amount of damage on the Japanese by air action. It has further been of assistance to me to be able to send requests for information to these parties, when I have wished to clear up the situation in any particular area.

When everyone has done such good work, it is perhaps invidious to single out any particular party for special mention, nevertheless I would like to express my particular appreciation for the efforts of Castens and Webster who have twice penetrated seventy miles across the Chindwin and operated in an area close to Pinbon, which was the centre from which a large proportion of the Japanese patrolling in the Upper Chindwin was initiated. I must mention too how greatly this patrol has assisted Major-General Wingate's columns on their way into and coming back from Burma.

As you might imagine, the Japanese were becoming very frustrated with having these covert British units operating in their midst. They had good intelligence about the Z Force officers involved and even possessed photographs of men such as Castens and Webster. They placed notices in all villages, asking for information on the whereabouts of the British spies and offered huge rewards for their capture, the most notable, 50,000 rupees in the area around Sinlamaung.

In October 1943 the ‘Johnnies’ went back into their operational areas and were immediately struck by the sudden increase in the number of Japanese present. They began to notice an obvious build-up of equipment and supplies during this period and also observed the construction of new and more substantial jungle tracks. In one particular case, close to the village of Homalin, there was a new road capable of transporting very large vehicles. All this information was radioed back to Delhi at once.

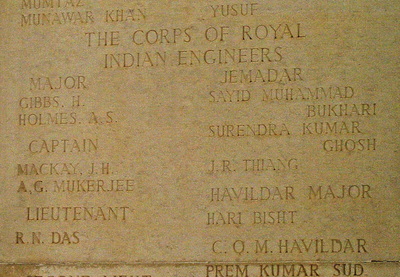

Around this time, Castens and Webster separated from each other in order to widen their area of reconnaissance. Webster took with him his trusted Kachin Havildar, Zau Gawng, while a new ‘Johnnie’ Captain John Henry Mackay teamed up with Bertie Castens. Sadly, Mackay became seriously ill with fever later in the year. Whilst out on his own reconnaissance patrol with Kachin NCO Hpawpaung Maw, Mackay and his group almost bumped into a Japanese patrol and had to retreat back into the jungle. In his growing delirium, Captain Mackay had to be supported as the party moved towards one of their jungle camps hidden behind a waterfall. Fortunately, the noise of the cascading water masked Mackay's fitful cries and the enemy patrol passed on by.

Two days later, on Christmas Eve, John Mackay died. The Kachin Levies laid out his body according to their own custom with all his valued possessions alongside him. They then moved away in search of Major Castens.

To view Captain Mackay's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2516209/MACKAY,%20JOHN%20HENRY

All Z Force units were now being supplied from the air, this enabled the groups to be far more active and free to patrol further than had been previously possible, it also ensured the regular supply of food and ammunition. Freddy Webster recalled the procedure for calling in an aircraft to the drop zone area:

We had a code by which we could communicate with the pilot and he with us. We sent out the message; 101 calling, 101 calling, to show we were ready. He replied, Get off the air, you’re interfering, which meant that he had received us. Then we called ‘223 572’ which meant, I can hear you away to my north, followed by other numbers when he was overhead. To this last message the reply was, ‘Get off the air, damn you’, this implied he had our location and we need not signal again.

It soon became quite clear to British India Command, that Castens and Webster had been observing the enemy moving up their forces in preparation for an attack on Imphal and Kohima. One report sent back by the ‘Johnnies’ included the sighting of Japanese tanks in the area, this was at first ridiculed by Allied Head Quarters, but the truth of the matter soon became apparent to the previously unsuspecting British Generals.

Castens, Webster and all the other Z Force units kept up an almost continual observation of the enemy preparations in the Chindwin area, reporting on new increased strengths of Japanese personnel and the location of any large concentrations of hardware and supplies. Many of these areas were then visited by the RAF with devastating results. Finally, in early March, the ‘Johnnies’ were able to report:

“All camps astir, general forward movement to the west set in.” A short time later came the update: “Practically all Japanese across the Chindwin.” The march on India had begun.

As the Japanese advance on Imphal and Kohima began, Castens and most of the other Z Force units moved back towards the Chindwin. Here they operated for a short time close to the west banks of the river, sending back their final reports on enemy movements. Apart from the Z Force patrol in the Chin Hills, this was the last action by the stay-behind units until after the battle for India was won.

However, Z Force was not to sit on its hands for long. General Slim had been a long-standing admirer of these gentlemen and planned to use their expertise again during the next phase of the war. Slim remarked:

I consider that the tactical information obtained by these patrols to be of paramount importance and there is no other G.S.I. organisation which produces Intelligence of the same operational importance and with such continuity. I consider it essential that every endeavour is made to ensure the continuation of Z Force British Officer Armed Patrols in front of any advance that the 14th Army may make into Central and Southern Burma.

By August 1944, Z Force patrols had increased in number to twenty, with some of these groups moving into new operational areas on foot, whilst others were parachuted in ahead of the 14th Army’s thrust across the Irrawaddy River. However, only six of the original ‘Johnnies’ took part in the expulsion of the Japanese from Burma during late 1944 and 1945. Both Bertie Castens and Robin Stewart dropped out of Z Force around this time and took up other important assignments.

The achievements of Z Force in Burma during the years 1942-45 cannot be over exaggerated. The intelligence they provided Allied Command formed the basis on which all future planning and decision making was based. By the end of the Japanese occupation in May 1945, twenty-six patrols had been in operation working alongside the conventional forces of the 14th Army.

Both Scoones and Slim had understood the value of these covert groups, and their enormous contribution to the war effort in Burma was recognised by India Command in the form of no fewer than 46 Gallantry awards.

Herbert Castens was recommended for the Distinguished Service Order in June 1944 in overall recognition of his work behind enemy lines during the Burma campaign. In the end, this award was reduced to a Military Cross by those in higher authority. His citation reads:

Throughout the greater part of the dry seasons 1942-1943 and 1943-1944, Major Castens carried out in Burma a mission during which he obtained for our forces a great deal of valuable information which would otherwise not have been available to us. In the course of this mission he led an extremely arduous existence and was constantly exposed to the risk of discovery and capture by the enemy; his area of operations was too remote from our Forces for him to have received any help in an emergency. He displayed an unusually high degree of personal courage, determination and endurance.

The above recommendation was signed by both Lieutenant-General Scoones and General Slim.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story, including the original recommendation for Major Castens' M.B.E. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Pinlebu, Pantha and Wuntho would all be subjected to aerial attacks over the following weeks and it can be no coincidence that Wingate investigated all three places over the course of his expedition. Z Force unit No. 3, active closer to the Chindwin River, but slightly further south than the other groups, were also able to assist Brigadier Wingate in early 1943. Major J.G. Middleton had been patrolling in the Kabaw Valley with Lieutenant-Colonel G.W. Parker and had good intelligence for both Wingate and Mike Calvert about enemy positions at Kalewa and Mawlaik.

Major Castens and the other Z Force parties returned to India in May 1943, just before the start of the monsoon. Herbert Castens was awarded the M.B.E. in July for his valiant work behind enemy lines, including his invaluable reconnaissance on behalf of the Chindits.

Lieutenant-General G. A. P. Scoones, the then Commander of 4th Corps had this to say about the efforts of Z Force that year:

Now that the monsoon has arrived and the G.S.I.z forward parties, which have been operating in 4th Corps, are coming back, I would like at this juncture to express my appreciation of the work which these parties have been doing.

I know well enough the hard conditions under which they have been living and operating for weeks on end. I know too the strain that the work imposes on all members of the parties, it has been described to my staff by an officer (not a member of one of the forward parties) as similar to hunting a wounded tiger.

In spite, however, of the many difficulties with which the parties have had to contend, they have managed to provide a flow of information which has been most valuable to me and has, I think, enabled us to inflict a considerable amount of damage on the Japanese by air action. It has further been of assistance to me to be able to send requests for information to these parties, when I have wished to clear up the situation in any particular area.

When everyone has done such good work, it is perhaps invidious to single out any particular party for special mention, nevertheless I would like to express my particular appreciation for the efforts of Castens and Webster who have twice penetrated seventy miles across the Chindwin and operated in an area close to Pinbon, which was the centre from which a large proportion of the Japanese patrolling in the Upper Chindwin was initiated. I must mention too how greatly this patrol has assisted Major-General Wingate's columns on their way into and coming back from Burma.

As you might imagine, the Japanese were becoming very frustrated with having these covert British units operating in their midst. They had good intelligence about the Z Force officers involved and even possessed photographs of men such as Castens and Webster. They placed notices in all villages, asking for information on the whereabouts of the British spies and offered huge rewards for their capture, the most notable, 50,000 rupees in the area around Sinlamaung.

In October 1943 the ‘Johnnies’ went back into their operational areas and were immediately struck by the sudden increase in the number of Japanese present. They began to notice an obvious build-up of equipment and supplies during this period and also observed the construction of new and more substantial jungle tracks. In one particular case, close to the village of Homalin, there was a new road capable of transporting very large vehicles. All this information was radioed back to Delhi at once.

Around this time, Castens and Webster separated from each other in order to widen their area of reconnaissance. Webster took with him his trusted Kachin Havildar, Zau Gawng, while a new ‘Johnnie’ Captain John Henry Mackay teamed up with Bertie Castens. Sadly, Mackay became seriously ill with fever later in the year. Whilst out on his own reconnaissance patrol with Kachin NCO Hpawpaung Maw, Mackay and his group almost bumped into a Japanese patrol and had to retreat back into the jungle. In his growing delirium, Captain Mackay had to be supported as the party moved towards one of their jungle camps hidden behind a waterfall. Fortunately, the noise of the cascading water masked Mackay's fitful cries and the enemy patrol passed on by.

Two days later, on Christmas Eve, John Mackay died. The Kachin Levies laid out his body according to their own custom with all his valued possessions alongside him. They then moved away in search of Major Castens.

To view Captain Mackay's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2516209/MACKAY,%20JOHN%20HENRY

All Z Force units were now being supplied from the air, this enabled the groups to be far more active and free to patrol further than had been previously possible, it also ensured the regular supply of food and ammunition. Freddy Webster recalled the procedure for calling in an aircraft to the drop zone area:

We had a code by which we could communicate with the pilot and he with us. We sent out the message; 101 calling, 101 calling, to show we were ready. He replied, Get off the air, you’re interfering, which meant that he had received us. Then we called ‘223 572’ which meant, I can hear you away to my north, followed by other numbers when he was overhead. To this last message the reply was, ‘Get off the air, damn you’, this implied he had our location and we need not signal again.

It soon became quite clear to British India Command, that Castens and Webster had been observing the enemy moving up their forces in preparation for an attack on Imphal and Kohima. One report sent back by the ‘Johnnies’ included the sighting of Japanese tanks in the area, this was at first ridiculed by Allied Head Quarters, but the truth of the matter soon became apparent to the previously unsuspecting British Generals.

Castens, Webster and all the other Z Force units kept up an almost continual observation of the enemy preparations in the Chindwin area, reporting on new increased strengths of Japanese personnel and the location of any large concentrations of hardware and supplies. Many of these areas were then visited by the RAF with devastating results. Finally, in early March, the ‘Johnnies’ were able to report:

“All camps astir, general forward movement to the west set in.” A short time later came the update: “Practically all Japanese across the Chindwin.” The march on India had begun.

As the Japanese advance on Imphal and Kohima began, Castens and most of the other Z Force units moved back towards the Chindwin. Here they operated for a short time close to the west banks of the river, sending back their final reports on enemy movements. Apart from the Z Force patrol in the Chin Hills, this was the last action by the stay-behind units until after the battle for India was won.

However, Z Force was not to sit on its hands for long. General Slim had been a long-standing admirer of these gentlemen and planned to use their expertise again during the next phase of the war. Slim remarked:

I consider that the tactical information obtained by these patrols to be of paramount importance and there is no other G.S.I. organisation which produces Intelligence of the same operational importance and with such continuity. I consider it essential that every endeavour is made to ensure the continuation of Z Force British Officer Armed Patrols in front of any advance that the 14th Army may make into Central and Southern Burma.

By August 1944, Z Force patrols had increased in number to twenty, with some of these groups moving into new operational areas on foot, whilst others were parachuted in ahead of the 14th Army’s thrust across the Irrawaddy River. However, only six of the original ‘Johnnies’ took part in the expulsion of the Japanese from Burma during late 1944 and 1945. Both Bertie Castens and Robin Stewart dropped out of Z Force around this time and took up other important assignments.

The achievements of Z Force in Burma during the years 1942-45 cannot be over exaggerated. The intelligence they provided Allied Command formed the basis on which all future planning and decision making was based. By the end of the Japanese occupation in May 1945, twenty-six patrols had been in operation working alongside the conventional forces of the 14th Army.

Both Scoones and Slim had understood the value of these covert groups, and their enormous contribution to the war effort in Burma was recognised by India Command in the form of no fewer than 46 Gallantry awards.

Herbert Castens was recommended for the Distinguished Service Order in June 1944 in overall recognition of his work behind enemy lines during the Burma campaign. In the end, this award was reduced to a Military Cross by those in higher authority. His citation reads:

Throughout the greater part of the dry seasons 1942-1943 and 1943-1944, Major Castens carried out in Burma a mission during which he obtained for our forces a great deal of valuable information which would otherwise not have been available to us. In the course of this mission he led an extremely arduous existence and was constantly exposed to the risk of discovery and capture by the enemy; his area of operations was too remote from our Forces for him to have received any help in an emergency. He displayed an unusually high degree of personal courage, determination and endurance.

The above recommendation was signed by both Lieutenant-General Scoones and General Slim.

Seen below is a final gallery of images in relation to this story, including the original recommendation for Major Castens' M.B.E. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2015. Special acknowledgement to the book, 'The Johnnies' by Lieutenant-General Sir Geoffrey Evans.