James Alexander Ewen MacPherson

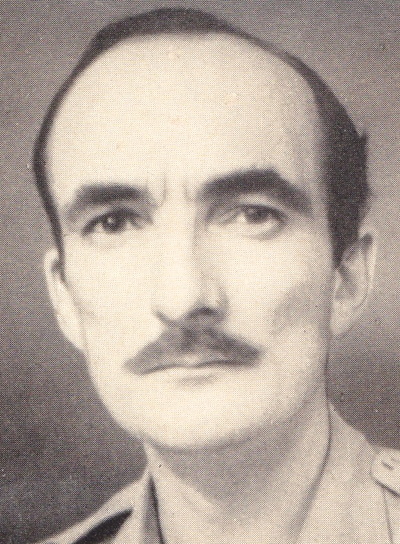

James MacPherson, circa 1944.

James MacPherson, circa 1944.

Captain James MacPherson was a member of the 2nd Burma Rifles during the first Chindit Operation in 1943. He was already an officer with experience and knowledge in meeting the new enemy by the time Wingate welcomed him into the ranks of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

James was born in Kimberley, South Africa on the 1st March 1913 and was the son of Alexander and Dora Louisa MacPherson. His father, of Scottish decent, had married Dora Louisa and the couple had chosen to settle in Dora's native South Africa.

James grew up in Kimberley and was educated to a high standard at the Christian Brother's College during the years 1920-1930. He then went on the University of Cape Town where he studied mathematics. In 1933 he was chosen to receive a Rhodes Scholarship and travelled to England to study philosophy and politics at Oxford University.

After his time at Oxford James travelled to several countries including a visit to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, this voyage of adventure was presumably to gain some experience of the world and to see what opportunities it might offer. By 1937 he was in India and looking for a career.

Towards the end of WW2, James returned to England as part of his duties with S.O.E. (the Special Operations Executive).

It was at this time that he married Phyllis Mary Millward on the 10th May 1945 at Christ Church, Burton in the county of Derbyshire. The newly married couple lived at 20b Nevern Place, South Kensington, London. In all Army correspondence, James had given his contact details as, ℅ Lloyds Bank, Pall Mall, London.

In 1937 he took a job with the Bombay/Burma Trading Corporation. The corporation had ventured in to Burma in order to develop the countries fledgling tea business and was one of the largest merchants in India at that time. For more information about the Bombay/Burma Trading Corporation, please click on the following link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombay_Burmah_Trading_Corporation

As the threat of war began to loom large over the region, James decided to enlist into the Army and was sent to the Officers Training Centre at Maymyo. From here he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant into the Burma Rifles on the 10th November 1939. During the first Burma campaign and the disastrous retreat in front of the all conquering Japanese, young Lieutenant MacPherson was posted to the 14th Shan States Battalion.

By early 1942, the newly promoted Captain MacPherson was part of the Army in Burma Reverse of Officers, with the Army number ABRO51.

His Army service records stated that James was:

5'11" tall and weighed approximately 140 llbs.

Had brown eyes and brown hair.

Was fluent in the Burmese, Hindustani and Afrikaans languages and was suitable for Army Intelligence work.

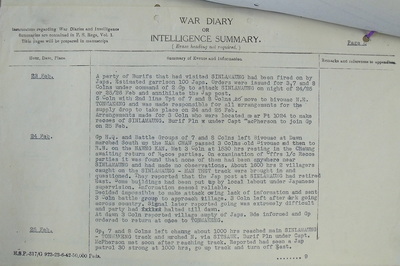

The officers of the 2nd Burma Rifles joined Chindit training on the 3rd September 1942 at the Abchand Camp in Patharia. James MacPherson was almost certainly part of the Battalion's Head Quarters commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel L.G. Wheeler, although he is mentioned in the Column 7 and Column 8 War diaries as having commanded platoons in both these units. There can be no doubt that he was a busy man, especially in those first few weeks inside Burma in February 1943.

Captain MacPherson and his platoon of Burma Riflemen were often used as a scouting party, sent out on their own to check on known Japanese positions. He was given the task of monitoring and preparing the route ahead as Wingate and Northern Group advanced eastwards towards the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. Another role that he performed was selecting and securing the locations for planned supply drops. MacPherson was basically the conduit by which all Chindit Columns received their information or orders during the early weeks of Operation Longcloth.

James was born in Kimberley, South Africa on the 1st March 1913 and was the son of Alexander and Dora Louisa MacPherson. His father, of Scottish decent, had married Dora Louisa and the couple had chosen to settle in Dora's native South Africa.

James grew up in Kimberley and was educated to a high standard at the Christian Brother's College during the years 1920-1930. He then went on the University of Cape Town where he studied mathematics. In 1933 he was chosen to receive a Rhodes Scholarship and travelled to England to study philosophy and politics at Oxford University.

After his time at Oxford James travelled to several countries including a visit to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, this voyage of adventure was presumably to gain some experience of the world and to see what opportunities it might offer. By 1937 he was in India and looking for a career.

Towards the end of WW2, James returned to England as part of his duties with S.O.E. (the Special Operations Executive).

It was at this time that he married Phyllis Mary Millward on the 10th May 1945 at Christ Church, Burton in the county of Derbyshire. The newly married couple lived at 20b Nevern Place, South Kensington, London. In all Army correspondence, James had given his contact details as, ℅ Lloyds Bank, Pall Mall, London.

In 1937 he took a job with the Bombay/Burma Trading Corporation. The corporation had ventured in to Burma in order to develop the countries fledgling tea business and was one of the largest merchants in India at that time. For more information about the Bombay/Burma Trading Corporation, please click on the following link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombay_Burmah_Trading_Corporation

As the threat of war began to loom large over the region, James decided to enlist into the Army and was sent to the Officers Training Centre at Maymyo. From here he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant into the Burma Rifles on the 10th November 1939. During the first Burma campaign and the disastrous retreat in front of the all conquering Japanese, young Lieutenant MacPherson was posted to the 14th Shan States Battalion.

By early 1942, the newly promoted Captain MacPherson was part of the Army in Burma Reverse of Officers, with the Army number ABRO51.

His Army service records stated that James was:

5'11" tall and weighed approximately 140 llbs.

Had brown eyes and brown hair.

Was fluent in the Burmese, Hindustani and Afrikaans languages and was suitable for Army Intelligence work.

The officers of the 2nd Burma Rifles joined Chindit training on the 3rd September 1942 at the Abchand Camp in Patharia. James MacPherson was almost certainly part of the Battalion's Head Quarters commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel L.G. Wheeler, although he is mentioned in the Column 7 and Column 8 War diaries as having commanded platoons in both these units. There can be no doubt that he was a busy man, especially in those first few weeks inside Burma in February 1943.

Captain MacPherson and his platoon of Burma Riflemen were often used as a scouting party, sent out on their own to check on known Japanese positions. He was given the task of monitoring and preparing the route ahead as Wingate and Northern Group advanced eastwards towards the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. Another role that he performed was selecting and securing the locations for planned supply drops. MacPherson was basically the conduit by which all Chindit Columns received their information or orders during the early weeks of Operation Longcloth.

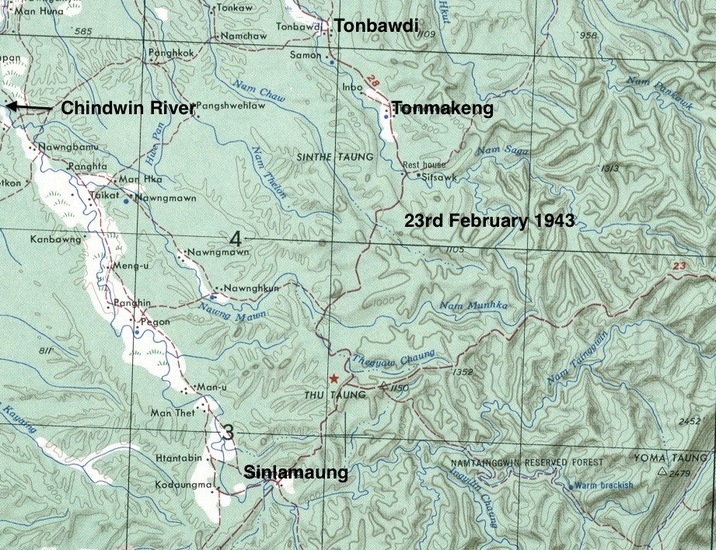

As the last week of February arrived the Chindits of Northern Group approached the village of Tonmakeng. Wingate decided that this location would be the ideal spot for the men to take their first large supply drop from Rear Base. Bernard Fergusson and Column 5 were ordered to secure the dropping zone. In the meantime news had come in via a Burma Rifle patrol, that a Japanese garrison was present in the village of Sinlamaung roughly 20 miles south of Tonmakeng. A combat party was assembled and set off to engage the enemy at Sinlamaung.

Captain MacPherson was employed at this time by ensuring that the tracks around the supply drop zone were kept clear of any inquisitive Burmese or enemy interference. From Bernard Fergusson's book, 'Beyond the Chindwin', here is his recollection of those few days in February 1943:

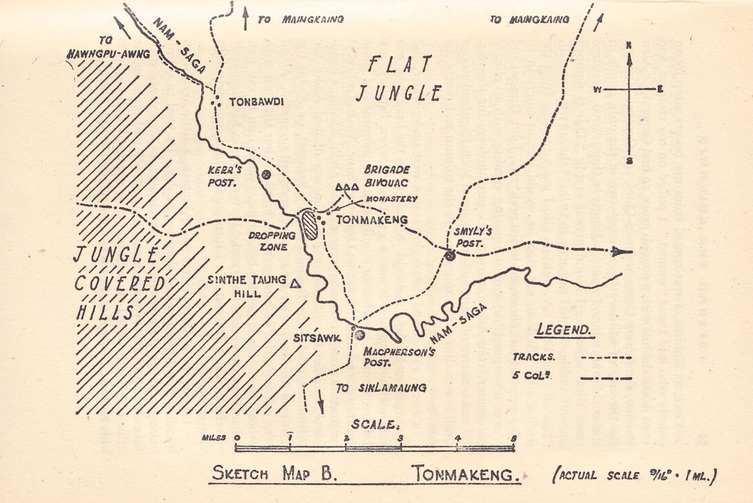

Tonmakeng stands on one of the most important north to south tracks in the district, and is an attractive village, fairly large by local standards. It lies on the Nam Saga, and is the most upstream of a series of villages whose paddy areas are almost continuous.

Above Tonmakeng, the chaung runs through jungle, and the flat lands on either side are crowded out by hills. The track by which we had come was poor and precipitous, not easy to follow. The last hill, the Sinthe Taung or Dead Elephant Hill, dominates the village. To the north, low rolling hills spread away to the Uyu River, a considerable stream that has its source up in the north near the Hukawng Valley.

At Tonmakeng we met Wheeler's party, which was camped on the Nam Saga about a mile from the village. He and Peter Buchanan were both in good form. A patrol had been sent to Sinlamaung, twenty miles south-east along the track and had found it held: one Burrif had a bullet in his leg to show for it, our first casualty.

We were in need of more food, and the country ahead was thought to be unsuitable for supply dropping; so the Brigadier had decided to have a mammoth supply drop at Tonmakeng for his whole force—Brigade Headquarters and the five columns with it. The few aircraft available for supplying the expedition would need three whole days to complete the drop. Rather than waste these three days, he would leave two columns to run the drop, and send three to beat up Sinlamaung, where the garrison was believed to be three hundred strong.

Orders for this operation were given at a conference on the bank of the chaung on the 23rd of February. Sam Cooke was to command the expeditionary force, which would be made up of 3 Column (Mike Calvert), 7 Column (Ken Gilkes) and 8 Column (Scotty).

4 Column was to be the first to ration up, and push out along the so-called "Secret Track"; I was to have the not very honourable task of running the supply drop. Until they were ready to move, 4 Column's Support Platoon and various other platoons were to come under me to help me in the defence of the area, for which I was made responsible. The more unwieldy parts of the expeditionary columns were to be left in a safe bivouac, which I was to select and protect.

Brigade Headquarters was going off for a little peace and quiet by itself in the jungle. I found a secluded place for the bivouac, and a use for the telephone, which everybody had mocked me for bringing. I had a permanent defence centre on the dropping ground (the big paddy near the village); and I put Tommy Roberts in charge.

John Kerr I sent off with his platoon about a mile away to stop the track down the valley, and gave him Judy, the message-carrying dog, and one of the two men between whom she ran. Bill Smyly, who was always pestering me for more militant employment than A.T.O., I sent off with ten of his Gurkhas as a stop on another track; Macpherson of the Burma Rifles with his platoon of Chins was already blocking the only other approach I knew of.

The march to Sinlamaung and the supply drop both began next morning. Hopes were high of doing some good at Sinlamaung; Alex's (Lieut. Col. Alexander) group down south had already drawn blood without loss to themselves, and we were hoping to do better. The fighting patrol sent to recover our mail had returned empty handed, and their report left little room for doubt that the Japs had got it. This meant that they knew our order of battle, and could probably have a fair guess at our strength, which was to be regretted, but, since there was nothing to be done about it, not to be unduly mourned.

The supply dropping was excellent. Everything fell on good ground, and I distributed it all round the columns as it came, the representatives of those columns on their way to Sinlamaung collecting it on their behalf. I was anxious that if the Japs should interrupt the performance before the curtain, the rations available should nevertheless be evenly distributed.

Denny Sharp, who was running the technical side of the drop, gossiped most of the day with Tommy Roberts and took photographs of the scene. The Sinlamaung expedition was abortive, in that the Japs got wind of it and skedaddled before the village was reached. They hurtled eastwards, spreading alarmist tales and causing much marching and counter-marching; so some benefit accrued.

The columns, thwarted of their prey, solaced themselves by destroying a large rice dump and other stores, and burning down some new and half-finished hutments which were apparently intended for monsoon quarters. They returned on the 26th tired, but not ill-pleased with themselves.

Meanwhile, we had had our own minor excitements. A patrol had come into Tonbawdi, the next village downstream from Tonmakeng, from the south-west. It must have crossed our recent track; but it continued on its way north without showing any interest in us. I made inquiries in Tonbawdi, and found that the patrol had no interpreter with it, so presumably it had come through villages teeming with gossip about us which it had failed to overhear.

As a patrol, it sounded rather inefficient. Another patrol had passed through Macpherson's post, but instead of coming towards Tonmakeng had kept on up the track towards Bill Smyly's. I sent him a warning, to keep a sharp look-out, but it never showed up there. There was no other known track up which it could have turned; and our complete loss of contact rather worried me.

Mac (MacPherson) was positive the Japs had not seen his men (with whom incidentally he was furious for not having opened up: he had, been snatching a sleep at the time), and Bill had had his finger on the trigger for twenty-four hours. Long afterwards, we heard that they had tumbled to our presence in Tonmakeng, and were so frightened that they hid starving in the jungle until sometime after we had moved on.

NB. The 'secret track' mentioned by Bernard Fergusson was a little known jungle trail that would, if navigated successfully, enable the Chindits to move through this area of Burma much more quickly than using the more obvious and well-used paths. It was known as 'Casten's Track', named after the Forestry Officer who first found it, Herbert Castens of Z Force.

Seen below is a diagram of the area around Tonmakeng, showing the supply drop zone and the position of the various Chindit patrols including that of Captain MacPherson. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Captain MacPherson was employed at this time by ensuring that the tracks around the supply drop zone were kept clear of any inquisitive Burmese or enemy interference. From Bernard Fergusson's book, 'Beyond the Chindwin', here is his recollection of those few days in February 1943:

Tonmakeng stands on one of the most important north to south tracks in the district, and is an attractive village, fairly large by local standards. It lies on the Nam Saga, and is the most upstream of a series of villages whose paddy areas are almost continuous.

Above Tonmakeng, the chaung runs through jungle, and the flat lands on either side are crowded out by hills. The track by which we had come was poor and precipitous, not easy to follow. The last hill, the Sinthe Taung or Dead Elephant Hill, dominates the village. To the north, low rolling hills spread away to the Uyu River, a considerable stream that has its source up in the north near the Hukawng Valley.

At Tonmakeng we met Wheeler's party, which was camped on the Nam Saga about a mile from the village. He and Peter Buchanan were both in good form. A patrol had been sent to Sinlamaung, twenty miles south-east along the track and had found it held: one Burrif had a bullet in his leg to show for it, our first casualty.

We were in need of more food, and the country ahead was thought to be unsuitable for supply dropping; so the Brigadier had decided to have a mammoth supply drop at Tonmakeng for his whole force—Brigade Headquarters and the five columns with it. The few aircraft available for supplying the expedition would need three whole days to complete the drop. Rather than waste these three days, he would leave two columns to run the drop, and send three to beat up Sinlamaung, where the garrison was believed to be three hundred strong.

Orders for this operation were given at a conference on the bank of the chaung on the 23rd of February. Sam Cooke was to command the expeditionary force, which would be made up of 3 Column (Mike Calvert), 7 Column (Ken Gilkes) and 8 Column (Scotty).

4 Column was to be the first to ration up, and push out along the so-called "Secret Track"; I was to have the not very honourable task of running the supply drop. Until they were ready to move, 4 Column's Support Platoon and various other platoons were to come under me to help me in the defence of the area, for which I was made responsible. The more unwieldy parts of the expeditionary columns were to be left in a safe bivouac, which I was to select and protect.

Brigade Headquarters was going off for a little peace and quiet by itself in the jungle. I found a secluded place for the bivouac, and a use for the telephone, which everybody had mocked me for bringing. I had a permanent defence centre on the dropping ground (the big paddy near the village); and I put Tommy Roberts in charge.

John Kerr I sent off with his platoon about a mile away to stop the track down the valley, and gave him Judy, the message-carrying dog, and one of the two men between whom she ran. Bill Smyly, who was always pestering me for more militant employment than A.T.O., I sent off with ten of his Gurkhas as a stop on another track; Macpherson of the Burma Rifles with his platoon of Chins was already blocking the only other approach I knew of.

The march to Sinlamaung and the supply drop both began next morning. Hopes were high of doing some good at Sinlamaung; Alex's (Lieut. Col. Alexander) group down south had already drawn blood without loss to themselves, and we were hoping to do better. The fighting patrol sent to recover our mail had returned empty handed, and their report left little room for doubt that the Japs had got it. This meant that they knew our order of battle, and could probably have a fair guess at our strength, which was to be regretted, but, since there was nothing to be done about it, not to be unduly mourned.

The supply dropping was excellent. Everything fell on good ground, and I distributed it all round the columns as it came, the representatives of those columns on their way to Sinlamaung collecting it on their behalf. I was anxious that if the Japs should interrupt the performance before the curtain, the rations available should nevertheless be evenly distributed.

Denny Sharp, who was running the technical side of the drop, gossiped most of the day with Tommy Roberts and took photographs of the scene. The Sinlamaung expedition was abortive, in that the Japs got wind of it and skedaddled before the village was reached. They hurtled eastwards, spreading alarmist tales and causing much marching and counter-marching; so some benefit accrued.

The columns, thwarted of their prey, solaced themselves by destroying a large rice dump and other stores, and burning down some new and half-finished hutments which were apparently intended for monsoon quarters. They returned on the 26th tired, but not ill-pleased with themselves.

Meanwhile, we had had our own minor excitements. A patrol had come into Tonbawdi, the next village downstream from Tonmakeng, from the south-west. It must have crossed our recent track; but it continued on its way north without showing any interest in us. I made inquiries in Tonbawdi, and found that the patrol had no interpreter with it, so presumably it had come through villages teeming with gossip about us which it had failed to overhear.

As a patrol, it sounded rather inefficient. Another patrol had passed through Macpherson's post, but instead of coming towards Tonmakeng had kept on up the track towards Bill Smyly's. I sent him a warning, to keep a sharp look-out, but it never showed up there. There was no other known track up which it could have turned; and our complete loss of contact rather worried me.

Mac (MacPherson) was positive the Japs had not seen his men (with whom incidentally he was furious for not having opened up: he had, been snatching a sleep at the time), and Bill had had his finger on the trigger for twenty-four hours. Long afterwards, we heard that they had tumbled to our presence in Tonmakeng, and were so frightened that they hid starving in the jungle until sometime after we had moved on.

NB. The 'secret track' mentioned by Bernard Fergusson was a little known jungle trail that would, if navigated successfully, enable the Chindits to move through this area of Burma much more quickly than using the more obvious and well-used paths. It was known as 'Casten's Track', named after the Forestry Officer who first found it, Herbert Castens of Z Force.

Seen below is a diagram of the area around Tonmakeng, showing the supply drop zone and the position of the various Chindit patrols including that of Captain MacPherson. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

As the expedition went on, James MacPherson was employed in much the same manner as before, including relaying Wingate's orders to various columns after the failed crossing of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March. As the disheartened Chindits moved back into the jungle on the east banks of the river close to the town Inywa, Wingate told MacPherson to travel eastward and find Bernard Fergusson and Column 5. MacPherson then gave Major Fergusson the order to act as Brigade decoy and lead the Japanese away from the other columns giving them a chance to re-group and disperse.

Once this was accomplished, Captain MacPherson returned to his own Brigade HQ. Eventually this group, led by Peter Buchanan made its way out of Burma via Fort Hertz in the far north of the country. After a period of rest and recuperation the 2nd Burma Rifles were reassembled at Karachi and it was here that some of the officers, including James were asked to prepare for Wingate's second Chindit operation planned for early 1944.

I have not been able to find out much detail in regards to his participation in 1944. However, from reading the book, The Road Past Mandalay, by John Masters, I do know that MacPherson was the commander of the Burma Rifles Platoon, in the Head Quarters Section of Masters' 111th Indian Infantry Brigade and was also attached at times to the columns of the 1st Cameronians. His main responsibilities on Operation Thursday, were communicating with the local villages and tribes people and of course scouting forward on the Brigade's line of march.

In April 1944, the Brigade were moving north and looking for a suitable location to set up a new Chindit stronghold. As his men were approaching the village of Namkwin and with the Burma Riflemen leading the way, John Masters recalled:

All my Burma Rifles were as happy as sand boys. Naturally enough, as this is their country. Saw Lader looks as though he has just stepped out of a bandbox. MacPherson is staring at the teak trees, but not with war in mind. In peacetime it was his job to cut and extract these trees for the mighty Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation.

James MacPherson interrogated the locals around Namkwin, seeking out news on the Japanese and their strength in the area. He was then selected by Lt-Colonel Masters to form part of a small reconnaissance group, whose job it was to select a location for the new stronghold:

I called the column commanders and we shared a bottle of rum, Thompson, Heap, Henning, Brennan, and I. Together we studied the map and the photographs, and I told them of my reconnaissance plan for the morrow. If I failed to return by dawn the day after, they must make no effort to find me. Tommy would assume command of the Brigade and carry out our task. I advised him that if I disappeared he would probably do best to move the Brigade right up to the position that night, inspect it personally the following dawn, and, if it were at all possible, occupy it. Tommy agreed, but I knew I was really just wasting breath.

The moment I vanished the responsibility would be his, and no post-mortem instructions from me could release him from that load. Just before first light the next day I left the harbour, with Flight-Lieutenant Chesty Jennings, Major Macpherson, and three Gurkha Riflemen. As the light strengthened we climbed out of the shallow valley, crossing a patch of very heavy going which had once held a village, probably Pumkrawng. We struggled through dense thorn underbush, lantana and prickly bamboo. We were very glad to get into the jungle again on top.

After rest, and now over an hour from harbour, we moved along the hill towards the railway valley. From this ridge, in places between the great trees, I could see the hump shape of the ridge between the Namyang and Namkwin Chaungs where I intended to place the block. The Gurkhas wore tattered, dirty uniform. Chesty, Mac, and I wore boots, a length of filthy checked green cotton material wound round our waists in the fashion of the Burmese longyi, and shirts, hats and light equipment.

We went carefully down the end of the ridge and entered the Namkwin Chaung, here running full between low cliffs. We walked a quarter of a mile down the bed in the water, and then climbed out into the actual complex of ridges of my chosen site. I began my inspection. The flanking hills stood too close to the north; but the water was excellent, plenty of it, good, and defiladed from all directions. The total perimeter length was about right; but reverse slopes, for protection against artillery fire, were only just adequate.

I searched the valley and the neighbouring hills through binoculars. Observation, good; fields of fire, fair in most directions. The aerial photographs had shown nothing better than this, and inspection confirmed it. We could hold this place for a good time against any attack and, when 14th Brigade arrived within the next week or so, what a bastion it would be. Supported by guns; as artillery would be flown in to me as soon as I had a C-47 field, we could really chew up any enemy within five miles, north or south. As for getting into position, there was the railway, in plain view, and the village of Namkwin, probably occupied by a few Japanese clerks and supply personnel.

Now for the last, the vital question, the airfield. We slipped down to the forward foot of the hills, and crouched in low scrub at the edge of the paddy. Some Burmans were working in a field between us and Namkwin railroad station; no one else in sight. Chesty Jennings adjusted a cloth round his head and stuck his carbine down his leg under his longyi. The paddy fields lay under the hot morning sun, with tall kaing grass at the far edge, and some trees beyond. I inspected Chesty. He didn't look at all like a Burman really, although marching for days with no shirt, his magnificent torso bared, had given him about the right colour. He'd have to do.

MacPherson and the Gurkhas prepared to give instant covering fire. Chesty and I walked out on to the paddy, and continued down the middle of it as though going somewhere, but not in a hurry. After four hundred yards we came to a steep drop of five feet; beyond this the paddy continued. I stayed at the drop, crouched as though smoking, my carbine ready. Chesty strolled on. I counted his paces. Another four hundred yards to the end of the flat and cleared land. Eight hundred yards in all. Chesty reached the end, drifted into the scrub, and came back round the edge of the fields. When he joined me, sweating richly, he muttered, 'Couldn't I do with a beer! . . . He told me the strip was good enough if we could flatten out a couple of humps halfway down.

Content with his choice for the Blackpool Block, Colonel Masters decided to dispense with the majority of the Brigade mules, choosing MacPherson to escort these animals and their handlers to an already predetermined rear base at a place called Mokso Sakan. From the pages of The Road Past Mandalay:

While my battalions filed into the block I gave orders for the evacuation of the animals. At the White City I had seen the effects of shell fire on the beasts, which could not be adequately protected. Nor did I have room for them in Blackpool. I kept only twenty-five, for emergency, to go out with patrols, and to help carry stores up from the strip. The rest I sent back, under Macpherson, over the hills to the Mokso Sakan base.

Unfortunately, Blackpool Block was not in operation for very long, in spite of desperate and tenacious defence by 111 Brigade, the position was overwhelmed by an intense enemy attack on the 24th May 1944. The surviving Chindits marching wearily away towards Mokso Sakan, making very slow headway across the flooded terrain and often knee-deep in mud. It is not known if Major MacPherson was still with the Brigade at this time.

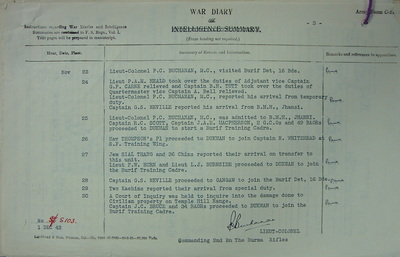

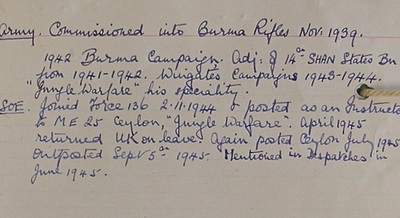

After Operation Thursday James joined another of the Special Forces acting inside Burma at that time. He took up an instructors role in Force 136 on the 2nd of November 1944, now holding the rank of Major he was based at the ME25 Jungle Warfare academy at Horona in Ceylon. He remained with Force 136 until leaving S.O.E. in September 1945. James was 'Mentioned in Despatches' in June 1945, I do not know whether this was for his work with Force 136 or the Chindits beforehand, potentially the award could have been for his combined efforts in Special Forces throughout the years of WW2.

For more information about Force 136, please click on the following link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Force_136

As mentioned at the beginning of this story, James married Phyllis Millward in May 1945, this was achieved whilst home on leave from his time with Force 136. I am not sure how the two met or whether Phyllis returned to India with James after their honeymoon.

James MacPherson and his contribution towards defeating the Japanese in WW2 was typical of the men who had originally made up the strength of 2nd Burma Rifles in 1943. Wingate stated that, of all the different component groups from his first Chindit Brigade, the 2nd Burma Rifles, or 'Burrifs' as they were nicknamed, were the stand out performers.

James MacPherson died on the 20th of December 1985 at Sudbury, a market town on the Essex-Suffolk borders, he was 72 years old.

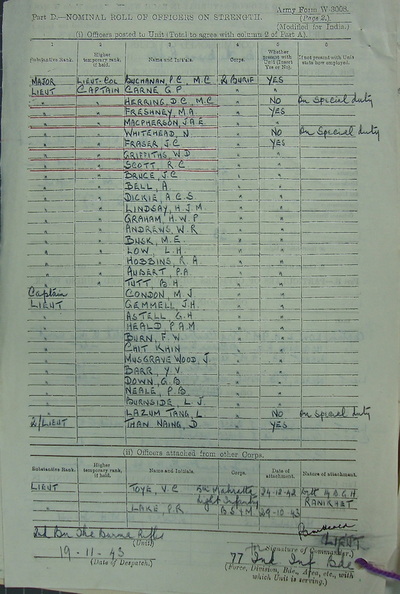

Seen below are some images depicting the Army career of James MacPherson, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Once this was accomplished, Captain MacPherson returned to his own Brigade HQ. Eventually this group, led by Peter Buchanan made its way out of Burma via Fort Hertz in the far north of the country. After a period of rest and recuperation the 2nd Burma Rifles were reassembled at Karachi and it was here that some of the officers, including James were asked to prepare for Wingate's second Chindit operation planned for early 1944.

I have not been able to find out much detail in regards to his participation in 1944. However, from reading the book, The Road Past Mandalay, by John Masters, I do know that MacPherson was the commander of the Burma Rifles Platoon, in the Head Quarters Section of Masters' 111th Indian Infantry Brigade and was also attached at times to the columns of the 1st Cameronians. His main responsibilities on Operation Thursday, were communicating with the local villages and tribes people and of course scouting forward on the Brigade's line of march.

In April 1944, the Brigade were moving north and looking for a suitable location to set up a new Chindit stronghold. As his men were approaching the village of Namkwin and with the Burma Riflemen leading the way, John Masters recalled:

All my Burma Rifles were as happy as sand boys. Naturally enough, as this is their country. Saw Lader looks as though he has just stepped out of a bandbox. MacPherson is staring at the teak trees, but not with war in mind. In peacetime it was his job to cut and extract these trees for the mighty Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation.

James MacPherson interrogated the locals around Namkwin, seeking out news on the Japanese and their strength in the area. He was then selected by Lt-Colonel Masters to form part of a small reconnaissance group, whose job it was to select a location for the new stronghold:

I called the column commanders and we shared a bottle of rum, Thompson, Heap, Henning, Brennan, and I. Together we studied the map and the photographs, and I told them of my reconnaissance plan for the morrow. If I failed to return by dawn the day after, they must make no effort to find me. Tommy would assume command of the Brigade and carry out our task. I advised him that if I disappeared he would probably do best to move the Brigade right up to the position that night, inspect it personally the following dawn, and, if it were at all possible, occupy it. Tommy agreed, but I knew I was really just wasting breath.

The moment I vanished the responsibility would be his, and no post-mortem instructions from me could release him from that load. Just before first light the next day I left the harbour, with Flight-Lieutenant Chesty Jennings, Major Macpherson, and three Gurkha Riflemen. As the light strengthened we climbed out of the shallow valley, crossing a patch of very heavy going which had once held a village, probably Pumkrawng. We struggled through dense thorn underbush, lantana and prickly bamboo. We were very glad to get into the jungle again on top.

After rest, and now over an hour from harbour, we moved along the hill towards the railway valley. From this ridge, in places between the great trees, I could see the hump shape of the ridge between the Namyang and Namkwin Chaungs where I intended to place the block. The Gurkhas wore tattered, dirty uniform. Chesty, Mac, and I wore boots, a length of filthy checked green cotton material wound round our waists in the fashion of the Burmese longyi, and shirts, hats and light equipment.

We went carefully down the end of the ridge and entered the Namkwin Chaung, here running full between low cliffs. We walked a quarter of a mile down the bed in the water, and then climbed out into the actual complex of ridges of my chosen site. I began my inspection. The flanking hills stood too close to the north; but the water was excellent, plenty of it, good, and defiladed from all directions. The total perimeter length was about right; but reverse slopes, for protection against artillery fire, were only just adequate.

I searched the valley and the neighbouring hills through binoculars. Observation, good; fields of fire, fair in most directions. The aerial photographs had shown nothing better than this, and inspection confirmed it. We could hold this place for a good time against any attack and, when 14th Brigade arrived within the next week or so, what a bastion it would be. Supported by guns; as artillery would be flown in to me as soon as I had a C-47 field, we could really chew up any enemy within five miles, north or south. As for getting into position, there was the railway, in plain view, and the village of Namkwin, probably occupied by a few Japanese clerks and supply personnel.

Now for the last, the vital question, the airfield. We slipped down to the forward foot of the hills, and crouched in low scrub at the edge of the paddy. Some Burmans were working in a field between us and Namkwin railroad station; no one else in sight. Chesty Jennings adjusted a cloth round his head and stuck his carbine down his leg under his longyi. The paddy fields lay under the hot morning sun, with tall kaing grass at the far edge, and some trees beyond. I inspected Chesty. He didn't look at all like a Burman really, although marching for days with no shirt, his magnificent torso bared, had given him about the right colour. He'd have to do.

MacPherson and the Gurkhas prepared to give instant covering fire. Chesty and I walked out on to the paddy, and continued down the middle of it as though going somewhere, but not in a hurry. After four hundred yards we came to a steep drop of five feet; beyond this the paddy continued. I stayed at the drop, crouched as though smoking, my carbine ready. Chesty strolled on. I counted his paces. Another four hundred yards to the end of the flat and cleared land. Eight hundred yards in all. Chesty reached the end, drifted into the scrub, and came back round the edge of the fields. When he joined me, sweating richly, he muttered, 'Couldn't I do with a beer! . . . He told me the strip was good enough if we could flatten out a couple of humps halfway down.

Content with his choice for the Blackpool Block, Colonel Masters decided to dispense with the majority of the Brigade mules, choosing MacPherson to escort these animals and their handlers to an already predetermined rear base at a place called Mokso Sakan. From the pages of The Road Past Mandalay:

While my battalions filed into the block I gave orders for the evacuation of the animals. At the White City I had seen the effects of shell fire on the beasts, which could not be adequately protected. Nor did I have room for them in Blackpool. I kept only twenty-five, for emergency, to go out with patrols, and to help carry stores up from the strip. The rest I sent back, under Macpherson, over the hills to the Mokso Sakan base.

Unfortunately, Blackpool Block was not in operation for very long, in spite of desperate and tenacious defence by 111 Brigade, the position was overwhelmed by an intense enemy attack on the 24th May 1944. The surviving Chindits marching wearily away towards Mokso Sakan, making very slow headway across the flooded terrain and often knee-deep in mud. It is not known if Major MacPherson was still with the Brigade at this time.

After Operation Thursday James joined another of the Special Forces acting inside Burma at that time. He took up an instructors role in Force 136 on the 2nd of November 1944, now holding the rank of Major he was based at the ME25 Jungle Warfare academy at Horona in Ceylon. He remained with Force 136 until leaving S.O.E. in September 1945. James was 'Mentioned in Despatches' in June 1945, I do not know whether this was for his work with Force 136 or the Chindits beforehand, potentially the award could have been for his combined efforts in Special Forces throughout the years of WW2.

For more information about Force 136, please click on the following link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Force_136

As mentioned at the beginning of this story, James married Phyllis Millward in May 1945, this was achieved whilst home on leave from his time with Force 136. I am not sure how the two met or whether Phyllis returned to India with James after their honeymoon.

James MacPherson and his contribution towards defeating the Japanese in WW2 was typical of the men who had originally made up the strength of 2nd Burma Rifles in 1943. Wingate stated that, of all the different component groups from his first Chindit Brigade, the 2nd Burma Rifles, or 'Burrifs' as they were nicknamed, were the stand out performers.

James MacPherson died on the 20th of December 1985 at Sudbury, a market town on the Essex-Suffolk borders, he was 72 years old.

Seen below are some images depicting the Army career of James MacPherson, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 01/11/2016.

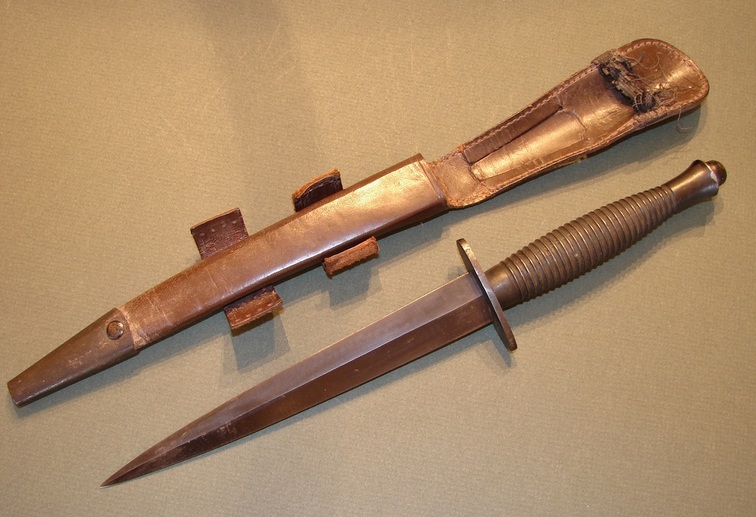

In early October 2016, I received an email contact from David Decker, informing me that he was now in possession of a Fairbairn Sykes fighting knife that once belonged to James MacPherson. After exchanging information about Major MacPherson and his Army career, (which now forms part of a website page on David's website), he was kind enough to send over a photograph of the knife in question, which can be seen below.

To visit David's interesting and informative website, please click on the following link: www.fairbairnsykesfightingknives.com/the-stories.html

In early October 2016, I received an email contact from David Decker, informing me that he was now in possession of a Fairbairn Sykes fighting knife that once belonged to James MacPherson. After exchanging information about Major MacPherson and his Army career, (which now forms part of a website page on David's website), he was kind enough to send over a photograph of the knife in question, which can be seen below.

To visit David's interesting and informative website, please click on the following link: www.fairbairnsykesfightingknives.com/the-stories.html

Copyright © Steve Fogden, October 2014.