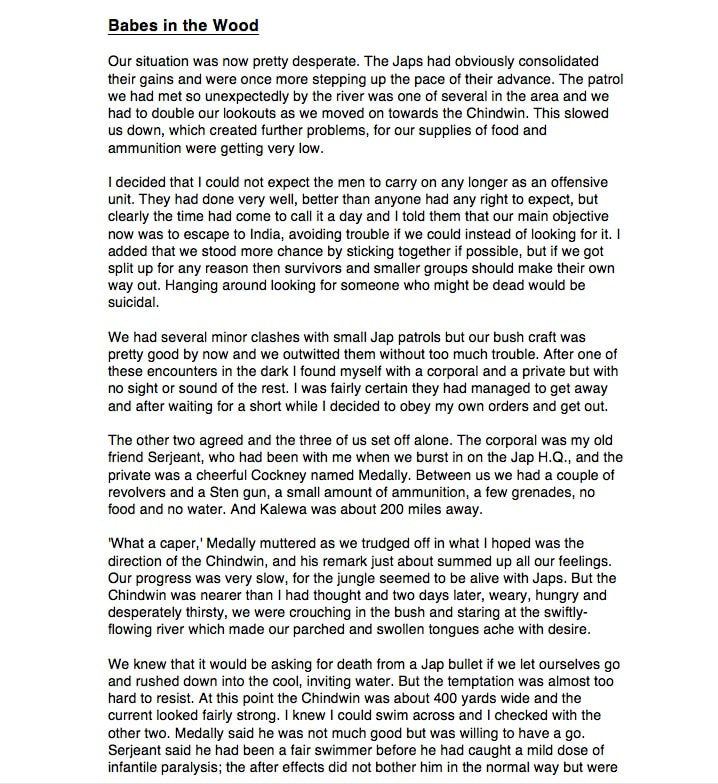

Clifford Sargent, Calvert's Bodyguard

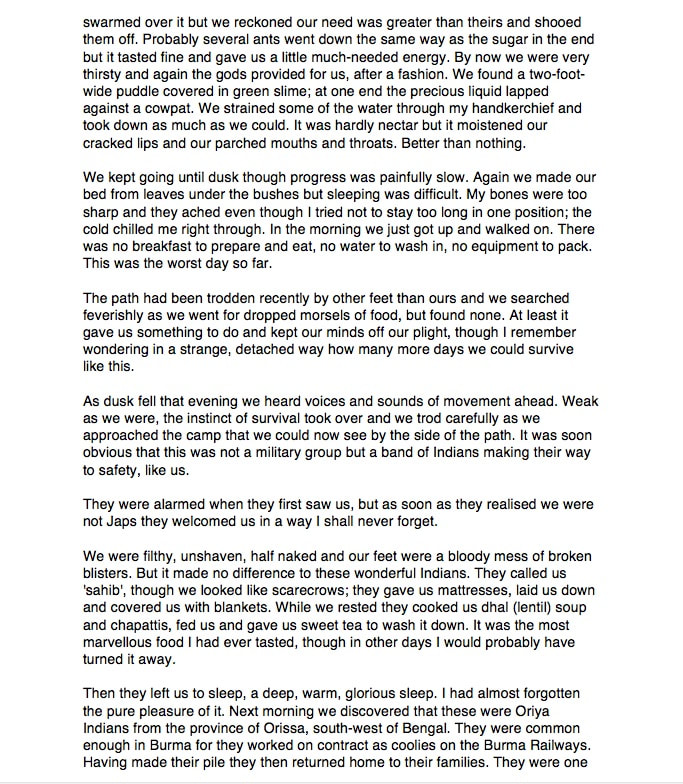

Clifford H. Sargent.

Clifford H. Sargent.

In June 2020, I was fortunate enough to be forwarded a letter recounting the exploits of a soldier who shared much, if not all of Mike Calvert's adventures in Burma (1942-44). The letter provoked the following email exchange:

Dear Rod,

Tony Redding has shared your recent letter with me, telling the WW2 experiences of your father, Clifford Sargent and his work with Mike Calvert. I am the archivist with the Chindit Society and by that very nature extremely interested in learning more about your father and his life during the war. The Society is collecting together as many photographs of men who served with the Chindits as it can and I wondered if you had an image of your father that you would be willing to share? I have already written about him on my Chindit website which deals with the first operation in 1943. The family of one of the other men with your father and Mike Calvert on the retreat from Burma, contacted me several years ago and I constructed a story from the information they gave me. The soldier was Jack Medalie, who Calvert calls Medally in his book Fighting Mad. Please take a look if you have a minute.

I hope you and your family are doing well during these difficult and rather challenging times.

Best wishes, Steve Fogden.

Dear Steve,

Great to hear from you, and thank you for the story about Jack Medalie, what an interesting read. I’m sure I’ve heard of the name Jack Medalie in my Dad’s stories before, in fact he may even be in at least one of my Dad’s photos. I would be happy to share any of Dad’s photos and stories. I’m sure he would approve as well. It’s a pleasure to talk to people who actually know there was a war in Burma, let alone what a Chindit was. There are not many veterans of any sort left in my small town in northern British Columbia. Canada in general doesn’t put much effort into military history. I’ve tried to keep myself informed with the Far East war story, reading or watching any programs I can find. Reading Tony Redding's book is what inspired me to contact him and find out what groups exist and what information is still out there. Generally, I learned about the war in Burma through my Dad's own stories and experiences. I am now appreciating learning about the bigger picture through websites like yours. Cheers and thank you for all your efforts. Rod Sargent.

Dear Rod,

Tony Redding has shared your recent letter with me, telling the WW2 experiences of your father, Clifford Sargent and his work with Mike Calvert. I am the archivist with the Chindit Society and by that very nature extremely interested in learning more about your father and his life during the war. The Society is collecting together as many photographs of men who served with the Chindits as it can and I wondered if you had an image of your father that you would be willing to share? I have already written about him on my Chindit website which deals with the first operation in 1943. The family of one of the other men with your father and Mike Calvert on the retreat from Burma, contacted me several years ago and I constructed a story from the information they gave me. The soldier was Jack Medalie, who Calvert calls Medally in his book Fighting Mad. Please take a look if you have a minute.

I hope you and your family are doing well during these difficult and rather challenging times.

Best wishes, Steve Fogden.

Dear Steve,

Great to hear from you, and thank you for the story about Jack Medalie, what an interesting read. I’m sure I’ve heard of the name Jack Medalie in my Dad’s stories before, in fact he may even be in at least one of my Dad’s photos. I would be happy to share any of Dad’s photos and stories. I’m sure he would approve as well. It’s a pleasure to talk to people who actually know there was a war in Burma, let alone what a Chindit was. There are not many veterans of any sort left in my small town in northern British Columbia. Canada in general doesn’t put much effort into military history. I’ve tried to keep myself informed with the Far East war story, reading or watching any programs I can find. Reading Tony Redding's book is what inspired me to contact him and find out what groups exist and what information is still out there. Generally, I learned about the war in Burma through my Dad's own stories and experiences. I am now appreciating learning about the bigger picture through websites like yours. Cheers and thank you for all your efforts. Rod Sargent.

Cap badge of the Seaforth Highlanders.

Cap badge of the Seaforth Highlanders.

The Sergeant-Major with the Odd name of Sargent (by Rod Sargent)

My father was born and raised in Kent, England. My sister and I still aren't sure of the year he was born, but we suspect it to be 1922. Sent off to an orphanage at a young age, he unceremoniously ended up in Balmoral Castle in Scotland for military training at the onset of WW2. Before he knew it (and possibly underage) he was a Seaforth Highlander and was then shipped off to India for overseas service. Selected for Special Forces training at Maymyo and then operations in Burma, he was soon facing the Japanese as one of Orde Wingate’s Chindits.

Dad went to sea after the war and worked as an electrician, eventually achieving master level. More than once our family had to move because he couldn't get along with employers. He liked to do things his own way and It was no surprise he ended up with his own company after he settled in Canada. As I know you are aware men like our fathers were honest and straight up. Dad didn't lie or exaggerate. He was the most honorable man I've ever known and he had this underlying duty to honour that seemed out of place in today's world. It was a strange sense of honour that I haven't seen in other people and it guided his actions. I'm surprised he didn't admire the Japanese more for their sense of duty and honour, but I know he hated them till he died in 2002.

If anyone asked him he would talk about the war, but rarely did that ever happen. Growing up it seemed a taboo subject around the house. We never asked about the huge scar that ran down his right leg. My parents divorced when I was nine and I didn't see him much through my teens. We came together after that and ended up living and working together. As we spent so much time together, I started asking questions about his war experiences and we talked in great detail about it. It seemed to be therapeutic for him and I became aware that I was hearing about an important part of history.

Dad was on every operation in Burma including the infamous retreat which is where he first worked with Mike Calvert. Dad was in the Calvert's third column on Operation Longcloth where he acted as his bodyguard. By the end of the war he had risen to the rank of Sergeant-Major. Calvert referred to him as the Sergeant-Major with the odd name of Sargent.

Dad had a knack of understating things. He referred to the brutal conditions in the jungle as tough, although on one occasion he described it as the worst conditions any soldier has ever suffered through. I have read the story of Calvert and a Corporal under fire running through the front door of a shack and coming face-to-face with several Japanese officers. That Corporal was my Dad, and he described it as follows:

The two of us were under fire and running across a dirt street. The only cover was this small hut, so we ran up the stairs missing the second step because it was often booby-trapped. We burst through the door with our guns in front of us. Around a table was a bunch of Japanese officers looking over maps. Calvert said something like, Sorry gentlemen, wrong door and we both jumped back out the way we came and ducked into the jungle. The Japs were able to follow us for a bit because they could hear us laughing. No one fired a shot!

My father was born and raised in Kent, England. My sister and I still aren't sure of the year he was born, but we suspect it to be 1922. Sent off to an orphanage at a young age, he unceremoniously ended up in Balmoral Castle in Scotland for military training at the onset of WW2. Before he knew it (and possibly underage) he was a Seaforth Highlander and was then shipped off to India for overseas service. Selected for Special Forces training at Maymyo and then operations in Burma, he was soon facing the Japanese as one of Orde Wingate’s Chindits.

Dad went to sea after the war and worked as an electrician, eventually achieving master level. More than once our family had to move because he couldn't get along with employers. He liked to do things his own way and It was no surprise he ended up with his own company after he settled in Canada. As I know you are aware men like our fathers were honest and straight up. Dad didn't lie or exaggerate. He was the most honorable man I've ever known and he had this underlying duty to honour that seemed out of place in today's world. It was a strange sense of honour that I haven't seen in other people and it guided his actions. I'm surprised he didn't admire the Japanese more for their sense of duty and honour, but I know he hated them till he died in 2002.

If anyone asked him he would talk about the war, but rarely did that ever happen. Growing up it seemed a taboo subject around the house. We never asked about the huge scar that ran down his right leg. My parents divorced when I was nine and I didn't see him much through my teens. We came together after that and ended up living and working together. As we spent so much time together, I started asking questions about his war experiences and we talked in great detail about it. It seemed to be therapeutic for him and I became aware that I was hearing about an important part of history.

Dad was on every operation in Burma including the infamous retreat which is where he first worked with Mike Calvert. Dad was in the Calvert's third column on Operation Longcloth where he acted as his bodyguard. By the end of the war he had risen to the rank of Sergeant-Major. Calvert referred to him as the Sergeant-Major with the odd name of Sargent.

Dad had a knack of understating things. He referred to the brutal conditions in the jungle as tough, although on one occasion he described it as the worst conditions any soldier has ever suffered through. I have read the story of Calvert and a Corporal under fire running through the front door of a shack and coming face-to-face with several Japanese officers. That Corporal was my Dad, and he described it as follows:

The two of us were under fire and running across a dirt street. The only cover was this small hut, so we ran up the stairs missing the second step because it was often booby-trapped. We burst through the door with our guns in front of us. Around a table was a bunch of Japanese officers looking over maps. Calvert said something like, Sorry gentlemen, wrong door and we both jumped back out the way we came and ducked into the jungle. The Japs were able to follow us for a bit because they could hear us laughing. No one fired a shot!

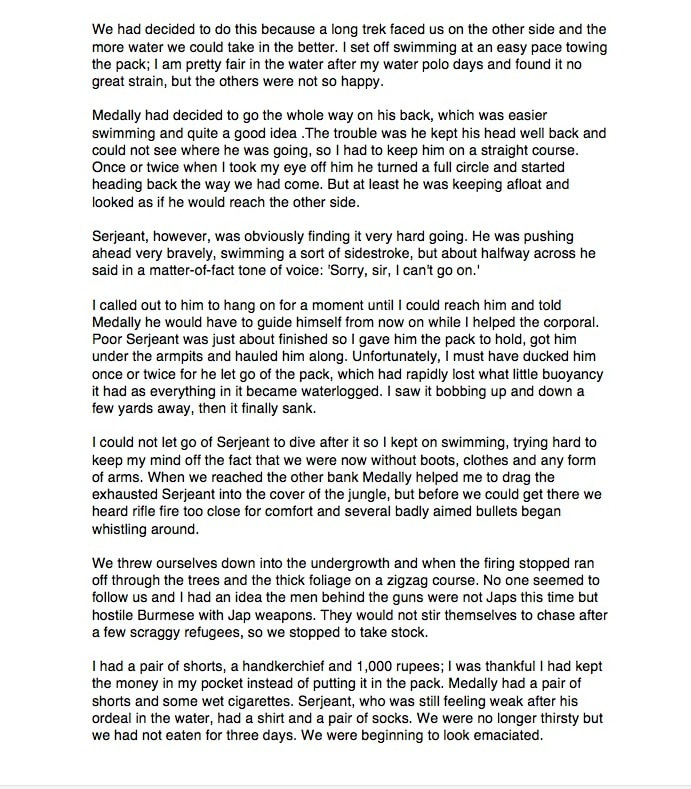

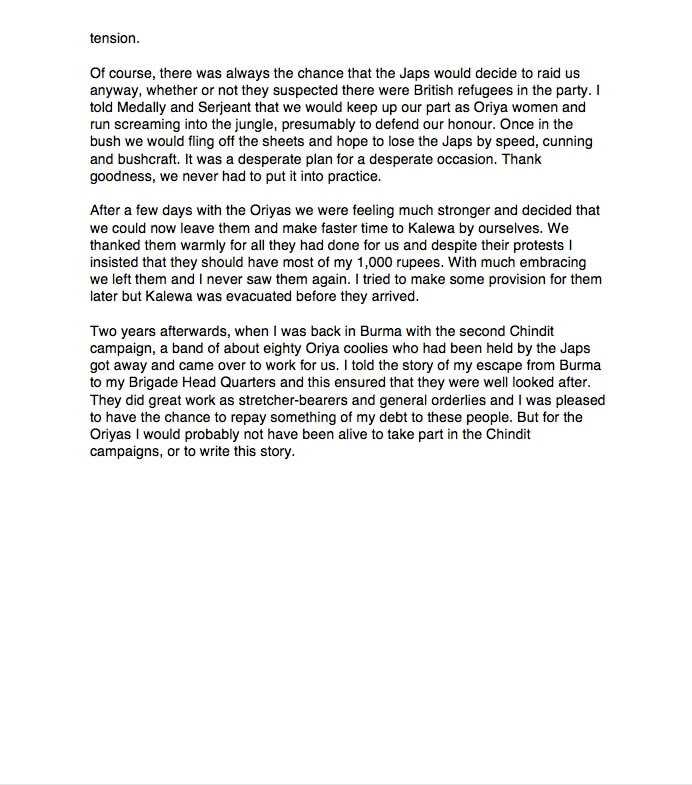

Brigadier Mike Calvert (1944).

Brigadier Mike Calvert (1944).

Dad talked about the Gurkha soldiers with the highest respect. He said they were the finest fighting soldiers. These indigenous men came from the Nepalese Himalayan mountains and considered being accepted into the British Army as the highest achievement possible. The testing was tough, but the parameters had to be adjusted as the Gurkha could not run straight on flat ground or swim very well.

The Gurkhas were so familiar with their Kukri knife, that it seemed to be a natural extension of their body. Dad saw a Gurkha ceremony where the object was for the young Gurkha to cut the head off a cow with a single blow. They were knowledgeable of the jungle and were experts at finding food when Chindits were out of air supply range. Dad described one method the Gurkha would use to kill some large species of lizard that lived along the many small rivers in Burma. One Gurkha would wade waist deep to the middle of the river. Several others would go upstream and beat the bushes along the river edges. These big lizards would spring out of the bushes and go straight to the middle of the river and head downstream. The Gurkha in the stream was motionless and would hold his Kukri in front of his chest and at the last moment the lizard would shoot left or right and in one motion his Kukri would flash down and the lizard's head would float off while the Gurkha snatched the body up.

Dad was given a Kukri by the Gurkhas and carried it with him always. It saved his life many times. The Gurkhas seemed to enjoy battle and thrived in the hand-to-hand fighting that so often occurred in Burma. Dad said he would see Gurkhas come out of a terrible battle involving swords and knives with the Japanese covered in blood, but with a big smile on their faces.

The hand-to-hand combat took place more than people know. I believe many men just never talked about it, or perhaps blocked it from their minds like how a person can't remember trauma after a bad car accident. I'm sure he never told me all he went through, but he did tell me about one incident. Pagoda Hill was a hilltop town with shrines and many small huts at the summit. The Japanese were entrenched and dug into these huts and had to be cleared out. It was a long stressful battle where the enemy wasn't always seen until they sprung out at you from the ground or a hut. Dad recalled a Jap jumping at him in this fashion and Dad knocked him down putting his boot on his back and taking his head off with his Kukri. The next instant another Jap leaped out of the same doorway screaming with his sword held high, and in an instant Dad buried his kukri into his head all the way down to his nose.

In another hand-to-hand fight, I'm not sure where, Dad had run out of ammunition and faced a Jap who had a pistol on his hip and a rifle fixed with a bayonet in front of him. He could have shot Dad, but it appeared he wanted to kill him with his bayonet. Dad let him thrust the bayonet to where it almost stuck him in the chest. At the same time, he blocked the bayonet down with his empty rifle and jumped up and over the Jap and brought a violent blow down across the back of his neck breaking his spine (at this point Dad showed me the exact neck bone to break to do this). Dad said he was confident enough in his skills that he learned not to fear any hand-to-hand combat. He also noticed the men that feared it usually didn't survive. Mike Calvert gives an account in his book Fighting Mad of a battle with a Japanese officer in a stream. Apparently both officers had wandered off from their respective camps and encountered each other by accident. Neither wanted to alert their camps so they fought quietly in the stream to the death. Calvert drowned the Jap and came back to camp. Dad picked up the story at this point and said:

We had no idea what Calvert had been through and that many Japanese soldiers were right around the bend in the river. Calvert had stumbled back into camp ragged and a mess. We subsequently snuck up and surrounded the Japanese camp and killed everyone there.

Many times they had to kill quietly. Their mission on the first Wingate expedition was to disrupt enemy communications, fuel dumps, supply stations, railways, whatever they could do to slow the enemy down. This meant stealthy approach at night and killing the soldiers on watch. Dad described how he would grab the soldier's head from behind and wipe the kukri across his throat. He said it was an easy motion, just a simple swiping across the throat and they would drop without making a sound. Dad said a strange thing happens when you're facing impossible odds in a prolonged hand-to-hand battle. Normal physical and mental limits don't seem to apply and you into a killing machine.

The Gurkhas were so familiar with their Kukri knife, that it seemed to be a natural extension of their body. Dad saw a Gurkha ceremony where the object was for the young Gurkha to cut the head off a cow with a single blow. They were knowledgeable of the jungle and were experts at finding food when Chindits were out of air supply range. Dad described one method the Gurkha would use to kill some large species of lizard that lived along the many small rivers in Burma. One Gurkha would wade waist deep to the middle of the river. Several others would go upstream and beat the bushes along the river edges. These big lizards would spring out of the bushes and go straight to the middle of the river and head downstream. The Gurkha in the stream was motionless and would hold his Kukri in front of his chest and at the last moment the lizard would shoot left or right and in one motion his Kukri would flash down and the lizard's head would float off while the Gurkha snatched the body up.

Dad was given a Kukri by the Gurkhas and carried it with him always. It saved his life many times. The Gurkhas seemed to enjoy battle and thrived in the hand-to-hand fighting that so often occurred in Burma. Dad said he would see Gurkhas come out of a terrible battle involving swords and knives with the Japanese covered in blood, but with a big smile on their faces.

The hand-to-hand combat took place more than people know. I believe many men just never talked about it, or perhaps blocked it from their minds like how a person can't remember trauma after a bad car accident. I'm sure he never told me all he went through, but he did tell me about one incident. Pagoda Hill was a hilltop town with shrines and many small huts at the summit. The Japanese were entrenched and dug into these huts and had to be cleared out. It was a long stressful battle where the enemy wasn't always seen until they sprung out at you from the ground or a hut. Dad recalled a Jap jumping at him in this fashion and Dad knocked him down putting his boot on his back and taking his head off with his Kukri. The next instant another Jap leaped out of the same doorway screaming with his sword held high, and in an instant Dad buried his kukri into his head all the way down to his nose.

In another hand-to-hand fight, I'm not sure where, Dad had run out of ammunition and faced a Jap who had a pistol on his hip and a rifle fixed with a bayonet in front of him. He could have shot Dad, but it appeared he wanted to kill him with his bayonet. Dad let him thrust the bayonet to where it almost stuck him in the chest. At the same time, he blocked the bayonet down with his empty rifle and jumped up and over the Jap and brought a violent blow down across the back of his neck breaking his spine (at this point Dad showed me the exact neck bone to break to do this). Dad said he was confident enough in his skills that he learned not to fear any hand-to-hand combat. He also noticed the men that feared it usually didn't survive. Mike Calvert gives an account in his book Fighting Mad of a battle with a Japanese officer in a stream. Apparently both officers had wandered off from their respective camps and encountered each other by accident. Neither wanted to alert their camps so they fought quietly in the stream to the death. Calvert drowned the Jap and came back to camp. Dad picked up the story at this point and said:

We had no idea what Calvert had been through and that many Japanese soldiers were right around the bend in the river. Calvert had stumbled back into camp ragged and a mess. We subsequently snuck up and surrounded the Japanese camp and killed everyone there.

Many times they had to kill quietly. Their mission on the first Wingate expedition was to disrupt enemy communications, fuel dumps, supply stations, railways, whatever they could do to slow the enemy down. This meant stealthy approach at night and killing the soldiers on watch. Dad described how he would grab the soldier's head from behind and wipe the kukri across his throat. He said it was an easy motion, just a simple swiping across the throat and they would drop without making a sound. Dad said a strange thing happens when you're facing impossible odds in a prolonged hand-to-hand battle. Normal physical and mental limits don't seem to apply and you into a killing machine.

Rod Sargent continues:

In one of the raids early on during the first campaign before they realised how brutal the Japanese treated their prisoners, Dad's small group was actually captured. They recognised him as an officer and separated him from the rest of the group. For a couple of days they kept him in a tent. They had him tied up and tortured him to get information. He said nothing and knew he was going to be killed. His only way to fight back was to stare in the eyes of the Japanese officer carrying out the torture. Dad said, he knew I would kill him if I could ever get my hands free. He could hear the rest of the men being killed and he figured this was it. For some reason the Japs left the tent and were away for awhile and during this time Dad got his hands free of the ropes.

At this time he could hear someone coming back to the tent. He stayed where he was as if still tied up. As luck would have it only a single Jap came through the tent door with his rifle slung over his shoulder. Dad immediately jumped on him and strangled him dead. As he cut a hole through the back of the tent, he could hear other Japs coming towards the tent. With no time to grab anything and in his rags, he dashed off into the jungle. The Japs came after him, but he somehow got away. Dad was a lost soldier wandering the jungle and things were getting desperate and dire when he came across a village. He said this was always tricky because you never knew who they were loyal to, but he had no choice and wandered in. The locals luckily were friendly took him in and nursed him back to health.

The enemy were brutal in their treatment of prisoners and had no regard for the lives of the those who surrendered. They wouldn't think anything of beating them till their bones broke, they starved them, drowned them in the latrines, buried them up to their necks and used them for bayonet practise, or simply worked them to death. Dad was always angry that the Japanese government never owned up to their actions or even taught their young people about their war history. He considered it insulting when the Canadian government gave retributions to Japanese citizens interned in Canada during the war.

In one horrible account, Dad spoke of liberating prisoners from a river front camp. The men were being held in a bus or truck. The rivers and estuaries of Burma contained huge crocodiles and some soldiers definitely were grabbed by crocs whilst swimming in bays and rivers like the Irrawaddy. The Chindits had to free the prisoners by killing the crocs that surrounded the truck. As It turned out, the Japs were feeding the prisoners to the crocs for entertainment. Dad said the only way to kill the crocs was to shoot into the ground under the snout and have the bullet ricochet up into the body. Dad never did like swimming and I only remember seeing him once in a pool for a brief swim on a hot day. I'm sure the thought of those crocs was the reason he never went into the water.

In one of the raids early on during the first campaign before they realised how brutal the Japanese treated their prisoners, Dad's small group was actually captured. They recognised him as an officer and separated him from the rest of the group. For a couple of days they kept him in a tent. They had him tied up and tortured him to get information. He said nothing and knew he was going to be killed. His only way to fight back was to stare in the eyes of the Japanese officer carrying out the torture. Dad said, he knew I would kill him if I could ever get my hands free. He could hear the rest of the men being killed and he figured this was it. For some reason the Japs left the tent and were away for awhile and during this time Dad got his hands free of the ropes.

At this time he could hear someone coming back to the tent. He stayed where he was as if still tied up. As luck would have it only a single Jap came through the tent door with his rifle slung over his shoulder. Dad immediately jumped on him and strangled him dead. As he cut a hole through the back of the tent, he could hear other Japs coming towards the tent. With no time to grab anything and in his rags, he dashed off into the jungle. The Japs came after him, but he somehow got away. Dad was a lost soldier wandering the jungle and things were getting desperate and dire when he came across a village. He said this was always tricky because you never knew who they were loyal to, but he had no choice and wandered in. The locals luckily were friendly took him in and nursed him back to health.

The enemy were brutal in their treatment of prisoners and had no regard for the lives of the those who surrendered. They wouldn't think anything of beating them till their bones broke, they starved them, drowned them in the latrines, buried them up to their necks and used them for bayonet practise, or simply worked them to death. Dad was always angry that the Japanese government never owned up to their actions or even taught their young people about their war history. He considered it insulting when the Canadian government gave retributions to Japanese citizens interned in Canada during the war.

In one horrible account, Dad spoke of liberating prisoners from a river front camp. The men were being held in a bus or truck. The rivers and estuaries of Burma contained huge crocodiles and some soldiers definitely were grabbed by crocs whilst swimming in bays and rivers like the Irrawaddy. The Chindits had to free the prisoners by killing the crocs that surrounded the truck. As It turned out, the Japs were feeding the prisoners to the crocs for entertainment. Dad said the only way to kill the crocs was to shoot into the ground under the snout and have the bullet ricochet up into the body. Dad never did like swimming and I only remember seeing him once in a pool for a brief swim on a hot day. I'm sure the thought of those crocs was the reason he never went into the water.

Rod Sargent's story concludes:

The war in the Far East went on log after it was supposed to be over. It was actually during this time Dad was wounded, somewhere in Java or Borneo I believe. He was shot in the leg and injured his femur. In traction for a year, refusing to allow the doctors to amputate, they finally came up with the solution of placing a steel pipe in place of his femur. He was told he would always need a wheelchair. After several months he walked using a cane and no chair. Then he was told he would always need the cane. Several months later he was walking without a cane. Then they told him he would always have a limp. Several months later he was walking normally. He carried out a disciplined exercise routine that included cycling and was determined to function normally. He started racing bicycles and became successful at it, totally regaining his strength and mobility.

He never ate rice, calling it the Burma Road and he hated the Japanese right to the end. I always made sure we weren't standing in line behind any Japanese people wherever we went as Dad wasn't very subtle. Strangely he seemed interested in the Samurai culture, perhaps he liked the discipline and honour of old, but he always said, that a Ninja would be no match for a Gurkha.

Dad never really made a good friend after the war. Perhaps he was unable to connect after all his friends had died out in Burma. In his later years we found a Burma veterans group on Vancouver Island and we went there several times. He started to become friends with a vet who was one of the British soldiers trapped at Imphal or Kohima. When he met Dad he gave him a big hug and thanked him for his service in Burma. Unfortunately, this man died soon afterwards. That was the only group he ever went to, although we had talked about getting back to Britain to connect with other groups, but we never did.

My father was shaped by the war. He was an intense interesting man with an an incredible ability to get over adversity very quickly. For a guy who had every reason to be depressed, he never seemed even close to it. Hardships could bring him down of course, but by the next day he was fine and ready to move forward. He was excellent at planning and had an eye for detail. He always seemed ready for confrontation and always spoke his mind. He had some regrets, especially not being able to help his mates who had died in Burma. He always felt the Chindits were the Forgotten Army and he was always angry at the military for making him write off to get his medals. After one particular discussion we had, I asked him how the hell he kept going in that damn jungle war. He simply replied: it was my job son.

The war in the Far East went on log after it was supposed to be over. It was actually during this time Dad was wounded, somewhere in Java or Borneo I believe. He was shot in the leg and injured his femur. In traction for a year, refusing to allow the doctors to amputate, they finally came up with the solution of placing a steel pipe in place of his femur. He was told he would always need a wheelchair. After several months he walked using a cane and no chair. Then he was told he would always need the cane. Several months later he was walking without a cane. Then they told him he would always have a limp. Several months later he was walking normally. He carried out a disciplined exercise routine that included cycling and was determined to function normally. He started racing bicycles and became successful at it, totally regaining his strength and mobility.

He never ate rice, calling it the Burma Road and he hated the Japanese right to the end. I always made sure we weren't standing in line behind any Japanese people wherever we went as Dad wasn't very subtle. Strangely he seemed interested in the Samurai culture, perhaps he liked the discipline and honour of old, but he always said, that a Ninja would be no match for a Gurkha.

Dad never really made a good friend after the war. Perhaps he was unable to connect after all his friends had died out in Burma. In his later years we found a Burma veterans group on Vancouver Island and we went there several times. He started to become friends with a vet who was one of the British soldiers trapped at Imphal or Kohima. When he met Dad he gave him a big hug and thanked him for his service in Burma. Unfortunately, this man died soon afterwards. That was the only group he ever went to, although we had talked about getting back to Britain to connect with other groups, but we never did.

My father was shaped by the war. He was an intense interesting man with an an incredible ability to get over adversity very quickly. For a guy who had every reason to be depressed, he never seemed even close to it. Hardships could bring him down of course, but by the next day he was fine and ready to move forward. He was excellent at planning and had an eye for detail. He always seemed ready for confrontation and always spoke his mind. He had some regrets, especially not being able to help his mates who had died in Burma. He always felt the Chindits were the Forgotten Army and he was always angry at the military for making him write off to get his medals. After one particular discussion we had, I asked him how the hell he kept going in that damn jungle war. He simply replied: it was my job son.

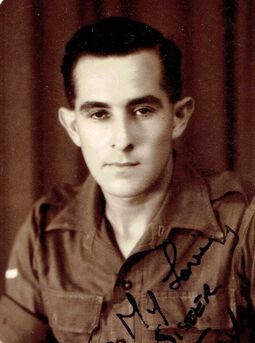

Seen below is a gallery containing the pages from Michael Calvert's book, Fighting Mad which tell the story of the author's journey back to India during the retreat from Burma in 1942. It is in this chapter of the book that Clifford Sargent and Jack Medalie are mentioned. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Rod Sargent, September 2020.