CSM John 'Jackie' Cairns MM an "Ideal Sergeant-Major"

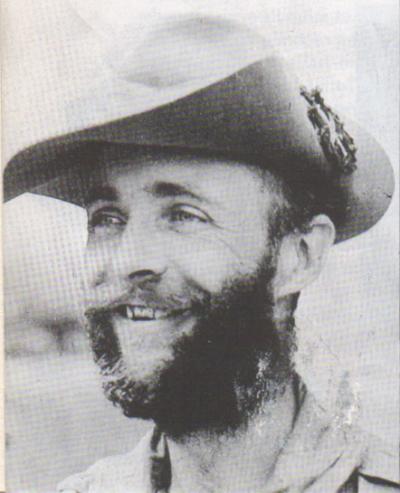

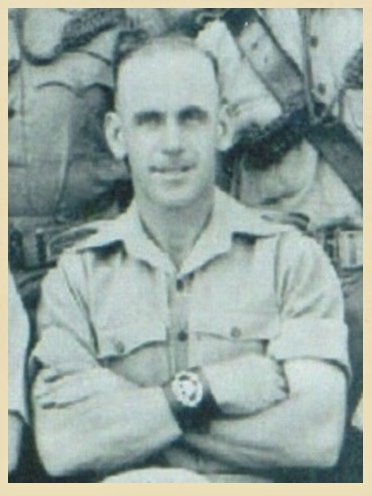

CSM John Cairns MM, Karachi in 1944.

CSM John Cairns MM, Karachi in 1944.

3183901 Company Sergeant-Major John Cairns was from Stranraer in Scotland and had enlisted in to the British Army early in WW2, originally joining the King's Own Scottish Borderer's, possibly at their regimental centre at Berwick.

John Cairns was one of a group of NCO's that were drafted into the 13th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment, soon after it had been raised in early 1940 and had taken up residence at the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow.

Nicknamed 'old Jackie', Cairns was to become a very popular and much respected NCO within A' Company of the new King's battalion. In early December 1941, he was part of the battalion's organisational party, as preparations began for the forthcoming overseas adventure, which would eventually lead to India and ultimately Wingate's arms. Nobody at this time could have ever imagined what lay in store for these men, or how few of them would ever return after the war was over.

NB. The source for John Cairns nickname was Georgina Livingstone, the wife of RSM William Livingstone, the Battalions Regimental Sergeant-Major and good friend of CSM Cairns. She told me that Jackie was a lovely man, a disciplinarian there can be no doubt, but with a good heart.

When the 13th King's were handed over to Orde Wingate in June 1942, A' Company was re-designated as Chindit Column 5 and 'Jackie' Cairns became Column Sergeant-Major. The column was originally commanded by Captain Edward Raymond Waugh from Manchester, a warm-hearted officer with a knack of putting everyone at ease. Ted Waugh had joined the 13th King's back in 1940 while the battalion were stationed in Wales; in India he had performed well and became the obvious choice to lead Column 5 when the King's moved up to Saugor. Unfortunately, Captain Waugh became unwell during Chindit training and was replaced by Bernard Fergusson as Column 5 commander on the 17th October, at this time the unit were operating close to the Indian town of Malthone.

Sergeant-Major Cairns was popular with men and officers alike. Lieutenant Philip Stibbe mentioned him in his book, 'Return via Rangoon':

"The Column Sergeant-Major was Jock Cairns of the King's Own Scottish Borderer's; a less dour Scot it would be hard to find. He had a grand sense of humour and was the personification of the Scots word 'leal'.

NB. 'Leal' literally means loyal and honest, used in particular when referring to loyalty to the crown or King and country.

Jackie Cairns took his place at the vanguard of Column 5 in 1943, marching close to his Major on the tracks and through the jungles of Burma that year. It was from Bernard Fergusson's book, 'Beyond the Chindwin', that the title quote for this short story was taken. Fergusson described the make up of his Column Head Quarters Company in the early pages of the book:

"Up at the head of the column marched Duncan and I and John Fraser; behind us came Cairns, the ideal Serjeant-Major, in temperament as much as efficiency; then came Peter Dorans; Serjeant Rothwell the Animal Transport Serjeant; L./Cpl. Lee the clerk; Horton the cipher operator, known throughout the column as Jimmy 'Orton; Foster and White, the two Signallers; Serjeant Skillander an Irish ex-jockey and spare Serjeant in Column Headquarters; and finally Brookes the bugler. They were a witty and cheerful lot, and John, Duncan and I were often in fits of laughter at what we overheard from just behind us."

Cairns was present at the demolition of the Bonchaung railway bridge on March 6th, which was the column's main objective on Operation Longcloth. He was also one of the last men across the Irrawaddy River (travelling eastward) at Tigyaing, enquiring and ensuring that his commander was safely on his way over that evening.

Jackie Cairns was perhaps remembered most for his quick-witted and humorous remarks, which he delivered with almost perfect timing. On one such occasion, as the column approached a village which they had traced on the map for many miles, and in which they hoped to find food; the men were suddenly confronted with a notice on the village stockade that read; "nobody allowed in this village after six pm." Cairns turned to Major Fergusson and said: "That is too bad sir, and after we have come all this way."

John Cairns was one of a group of NCO's that were drafted into the 13th Battalion of the King's Liverpool Regiment, soon after it had been raised in early 1940 and had taken up residence at the Jordan Hill Barracks in Glasgow.

Nicknamed 'old Jackie', Cairns was to become a very popular and much respected NCO within A' Company of the new King's battalion. In early December 1941, he was part of the battalion's organisational party, as preparations began for the forthcoming overseas adventure, which would eventually lead to India and ultimately Wingate's arms. Nobody at this time could have ever imagined what lay in store for these men, or how few of them would ever return after the war was over.

NB. The source for John Cairns nickname was Georgina Livingstone, the wife of RSM William Livingstone, the Battalions Regimental Sergeant-Major and good friend of CSM Cairns. She told me that Jackie was a lovely man, a disciplinarian there can be no doubt, but with a good heart.

When the 13th King's were handed over to Orde Wingate in June 1942, A' Company was re-designated as Chindit Column 5 and 'Jackie' Cairns became Column Sergeant-Major. The column was originally commanded by Captain Edward Raymond Waugh from Manchester, a warm-hearted officer with a knack of putting everyone at ease. Ted Waugh had joined the 13th King's back in 1940 while the battalion were stationed in Wales; in India he had performed well and became the obvious choice to lead Column 5 when the King's moved up to Saugor. Unfortunately, Captain Waugh became unwell during Chindit training and was replaced by Bernard Fergusson as Column 5 commander on the 17th October, at this time the unit were operating close to the Indian town of Malthone.

Sergeant-Major Cairns was popular with men and officers alike. Lieutenant Philip Stibbe mentioned him in his book, 'Return via Rangoon':

"The Column Sergeant-Major was Jock Cairns of the King's Own Scottish Borderer's; a less dour Scot it would be hard to find. He had a grand sense of humour and was the personification of the Scots word 'leal'.

NB. 'Leal' literally means loyal and honest, used in particular when referring to loyalty to the crown or King and country.

Jackie Cairns took his place at the vanguard of Column 5 in 1943, marching close to his Major on the tracks and through the jungles of Burma that year. It was from Bernard Fergusson's book, 'Beyond the Chindwin', that the title quote for this short story was taken. Fergusson described the make up of his Column Head Quarters Company in the early pages of the book:

"Up at the head of the column marched Duncan and I and John Fraser; behind us came Cairns, the ideal Serjeant-Major, in temperament as much as efficiency; then came Peter Dorans; Serjeant Rothwell the Animal Transport Serjeant; L./Cpl. Lee the clerk; Horton the cipher operator, known throughout the column as Jimmy 'Orton; Foster and White, the two Signallers; Serjeant Skillander an Irish ex-jockey and spare Serjeant in Column Headquarters; and finally Brookes the bugler. They were a witty and cheerful lot, and John, Duncan and I were often in fits of laughter at what we overheard from just behind us."

Cairns was present at the demolition of the Bonchaung railway bridge on March 6th, which was the column's main objective on Operation Longcloth. He was also one of the last men across the Irrawaddy River (travelling eastward) at Tigyaing, enquiring and ensuring that his commander was safely on his way over that evening.

Jackie Cairns was perhaps remembered most for his quick-witted and humorous remarks, which he delivered with almost perfect timing. On one such occasion, as the column approached a village which they had traced on the map for many miles, and in which they hoped to find food; the men were suddenly confronted with a notice on the village stockade that read; "nobody allowed in this village after six pm." Cairns turned to Major Fergusson and said: "That is too bad sir, and after we have come all this way."

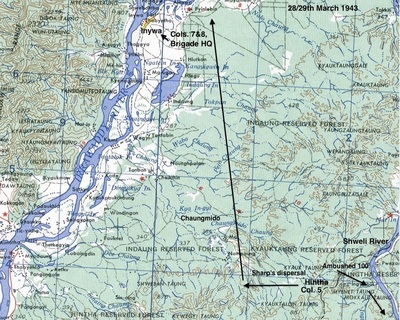

Wingate had taken a calculated gamble in ordering his Brigade over the Irrawaddy in March 1943, he had enjoyed relative success so far on the expedition and wanted to see just how far his methods of long range penetration could be pushed. It turned out to be an error of judgement on his part, as five of his Chindit Columns now found themselves trapped within an area of land, hemmed in on two sides by the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers and to the south, a motor road patrolled heavily by the Japanese.

Back in India, 4 Corps HQ in conversation with Wingate decided it was time to recall the Brigade and general dispersal was ordered on the 29th March. Wingate and his men headed west towards the Irrawaddy at place called Inywa. At this time Column 5 had been separated from the main body for about a week, they had also been unlucky with their supply drops, having missed their share at a place called Baw on the 24th March. On top of this, the Brigadier was now asking them to act as rearguard and lead the Japanese away from the area around Inywa.

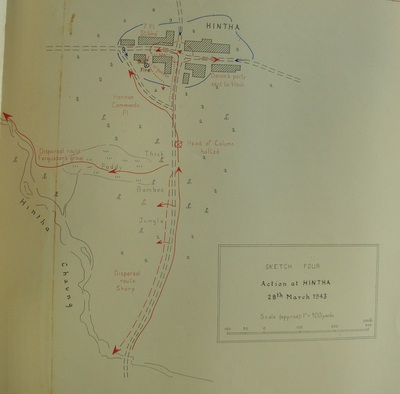

Acting as decoy and 'trailing their coat', Fergusson and Column 5 moved back south-eastwards towards the Hethin Chaung. On the evening of the 28th March they had reached the outskirts of a village named Hintha (please see the maps shown above for more detail about the village and the action fought there). After several hours of reconnaissance in search of an alternative, Fergusson realised that he and his men would have to move through the village as thick and impenetrable bamboo jungle prevented any route around. It was at Hintha that Column 5 met their 'Waterloo' as they soon discovered that the village was occupied by a large Japanese patrol.

Fighting platoons led by Lieutenant Stibbe and Jim Harman entered the village in an attempt to clear the road of Japanese. These were met in full force by the enemy and several casualties were taken on both sides. Stibbe, himself now wounded, returned to the base position of the column and reported to the Major that the situation was getting very hot and that the Japanese were making any forward movement extremely difficult.

From his book 'Beyond the Chindwin' Bernard Fergusson takes up the story:

"Alec Macdonald was beside me, and immediately said: "I'll have a look. Come on," and disappeared up the track. I had a feeling that, having failed on Peter Dorans' flank, the Japs would try and come in on the right, somewhere down the column; so I passed the word back to try and work a small flank guard into the jungle on that side if possible.

Then I went back to the T-junction, and made arrangements to attract all the attention we could, so as to give Alec a free run. I seemed to spend the whole action trotting up and down that seventy yards of track.

There came another burst of fire from the little track, a mixture of light machine gun, tommy-guns and grenades. The Commando Platoon alone in the column had tommy-guns, which was one of the reasons I had selected them for the role. Their cheerful rattle, however, meant that the little track was no longer clear. I hurried back to the fork, and there found Denny Sharp.

"This is going to be no good," I said. "Denny, take all the animals you can find, go back to the chaung and see if you can get down it. We'll go on playing about here to keep their attention fixed; I'll try and join you farther down the chaung, but if I don't then you know the next rendezvous point. Keep away from Chaungmido, as we don't want to get Brigade muddled up in this."

Seen below are photographs of Major Bernard Fergusson and Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp, click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Back in India, 4 Corps HQ in conversation with Wingate decided it was time to recall the Brigade and general dispersal was ordered on the 29th March. Wingate and his men headed west towards the Irrawaddy at place called Inywa. At this time Column 5 had been separated from the main body for about a week, they had also been unlucky with their supply drops, having missed their share at a place called Baw on the 24th March. On top of this, the Brigadier was now asking them to act as rearguard and lead the Japanese away from the area around Inywa.

Acting as decoy and 'trailing their coat', Fergusson and Column 5 moved back south-eastwards towards the Hethin Chaung. On the evening of the 28th March they had reached the outskirts of a village named Hintha (please see the maps shown above for more detail about the village and the action fought there). After several hours of reconnaissance in search of an alternative, Fergusson realised that he and his men would have to move through the village as thick and impenetrable bamboo jungle prevented any route around. It was at Hintha that Column 5 met their 'Waterloo' as they soon discovered that the village was occupied by a large Japanese patrol.

Fighting platoons led by Lieutenant Stibbe and Jim Harman entered the village in an attempt to clear the road of Japanese. These were met in full force by the enemy and several casualties were taken on both sides. Stibbe, himself now wounded, returned to the base position of the column and reported to the Major that the situation was getting very hot and that the Japanese were making any forward movement extremely difficult.

From his book 'Beyond the Chindwin' Bernard Fergusson takes up the story:

"Alec Macdonald was beside me, and immediately said: "I'll have a look. Come on," and disappeared up the track. I had a feeling that, having failed on Peter Dorans' flank, the Japs would try and come in on the right, somewhere down the column; so I passed the word back to try and work a small flank guard into the jungle on that side if possible.

Then I went back to the T-junction, and made arrangements to attract all the attention we could, so as to give Alec a free run. I seemed to spend the whole action trotting up and down that seventy yards of track.

There came another burst of fire from the little track, a mixture of light machine gun, tommy-guns and grenades. The Commando Platoon alone in the column had tommy-guns, which was one of the reasons I had selected them for the role. Their cheerful rattle, however, meant that the little track was no longer clear. I hurried back to the fork, and there found Denny Sharp.

"This is going to be no good," I said. "Denny, take all the animals you can find, go back to the chaung and see if you can get down it. We'll go on playing about here to keep their attention fixed; I'll try and join you farther down the chaung, but if I don't then you know the next rendezvous point. Keep away from Chaungmido, as we don't want to get Brigade muddled up in this."

Seen below are photographs of Major Bernard Fergusson and Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp, click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Denny Sharp moved away from Hintha that evening with the majority of the column in tow, amongst their number was Sergeant-Major Cairns. Not long afterwards this unit was cut in two when it was ambushed by a Japanese patrol. One hundred men including Cairns were separated from the main body. This group, now split up into penny packets, headed almost directly north and rather fortuitously met up with Column 7 at the Shweli River.

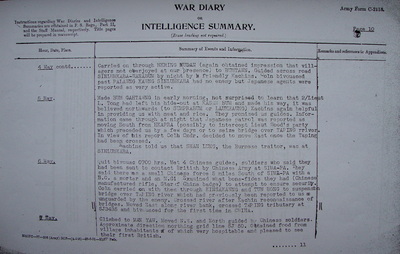

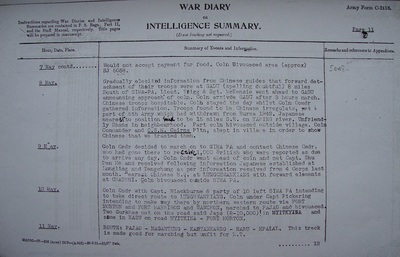

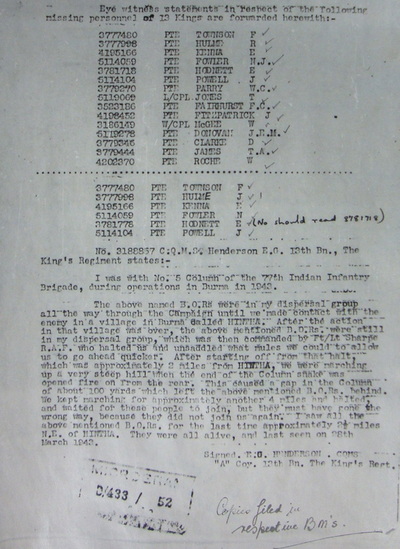

Another man present with this breakaway group was Quartermaster Sergeant Ernest Henderson, also formerly of the King's Own Scottish Borderer's. Henderson gave a witness statement in February 1944, explaining what had happened after the dispersal party had left Hintha:

"I was with number five Column of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, during operations in Burma in 1943. The above-mentioned British Other Ranks (shown in the image below) were in my dispersal group all the way through the campaign until we made contact with the enemy in a village in Burma called Hintha.

After the action in that village was over, the above-mentioned soldiers were still in my dispersal group, which was then commanded by Flight Lieutenant Sharp of the RAF. We halted and unsaddled our mules so we could go ahead much quicker.

After starting off from that halt, which was approximately 2 miles from Hintha, we were attacked by a Japanese patrol. This caused a gap in the column, but we kept marching for approximately another 4 miles and then stopped, we waited for these people to catch up, but they must have gone wrong way, because they did not rejoin us again. I saw all the above-mentioned men for the last time approximately two and a half miles north east of Hintha. They were all alive, and last seen on 28th March 1943."

As previously stated, the group, now cut adrift from Flight-Lieutenant Sharp moved towards the Shweli and by good fortune met up with Column 7 at the river. Major Gilkes took the stragglers from Column 5 under his wing. He allocated these men into his already pre-arranged dispersal groups and the men headed towards the Yunnan Borders of China in order to exit Burma.

Meanwhile, Bernard Fergusson after a long and protracted withdrawal from Hintha, had finally met up with Denny Sharp and the rest of Column 5 at the agreed rendezvous point. Fergusson halted the column to take stock of the situation and to check his numbers. From his book, Beyond the Chindwin he recalls:

"With me were Duncan and John, the bulk of Column Headquarters, Tommy Blow and his platoon, Tommy Roberts and the bulk of the Support Platoon and Sergeant Thornborrow and the remnants of Philip Stibbe's Platoon. Missing were, Sergeant-Major Cairns, Pepper the runner, Lance Corporal Lee the column clerk, Foster and White the Signallers and one or two others. Cairns had last been seen helping Denny Sharp with all the animals and Foster, White and Lee were believed to have gone with the animals which carried their various bits of property.

I consoled my men by telling them that if any man was likely to get himself out of Burma, together with whoever was with him, it was Serjeant-Major Cairns."

Fergusson proved to be accurate in his thoughts and statement, as Jackie Cairns and the fifteen men from Column 5 present with him during the march through the Chinese Yunnan Borders in May/June 1943, did indeed survive and reach the safety of India once more. Reading through the Column 7 war diaries it would appear that Cairns worked alongside men such as Lieutenant Trigg of the Royal Engineers and led his own dispersal platoon which formed part of Major Gilkes's main party.

After reaching the Chinese city of Paoshan, Column 7 and the remaining men from Column 5 were airlifted back to India aboard USAAF Dakotas and went straight into hospital. After a period of rest and recuperation, Jackie Cairns and the other survivors of the 13th King's re-joined their comrades at the Napier Barracks in Karachi.

Seen below are two pages from the Column 7 war diary, describing the long trek out through the Yunnan Borders and Cairns contribution to the group. Also shown is the witness statement given by Quartermaster Sergeant Ernest Henderson in February 1944. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Another man present with this breakaway group was Quartermaster Sergeant Ernest Henderson, also formerly of the King's Own Scottish Borderer's. Henderson gave a witness statement in February 1944, explaining what had happened after the dispersal party had left Hintha:

"I was with number five Column of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, during operations in Burma in 1943. The above-mentioned British Other Ranks (shown in the image below) were in my dispersal group all the way through the campaign until we made contact with the enemy in a village in Burma called Hintha.

After the action in that village was over, the above-mentioned soldiers were still in my dispersal group, which was then commanded by Flight Lieutenant Sharp of the RAF. We halted and unsaddled our mules so we could go ahead much quicker.

After starting off from that halt, which was approximately 2 miles from Hintha, we were attacked by a Japanese patrol. This caused a gap in the column, but we kept marching for approximately another 4 miles and then stopped, we waited for these people to catch up, but they must have gone wrong way, because they did not rejoin us again. I saw all the above-mentioned men for the last time approximately two and a half miles north east of Hintha. They were all alive, and last seen on 28th March 1943."

As previously stated, the group, now cut adrift from Flight-Lieutenant Sharp moved towards the Shweli and by good fortune met up with Column 7 at the river. Major Gilkes took the stragglers from Column 5 under his wing. He allocated these men into his already pre-arranged dispersal groups and the men headed towards the Yunnan Borders of China in order to exit Burma.

Meanwhile, Bernard Fergusson after a long and protracted withdrawal from Hintha, had finally met up with Denny Sharp and the rest of Column 5 at the agreed rendezvous point. Fergusson halted the column to take stock of the situation and to check his numbers. From his book, Beyond the Chindwin he recalls:

"With me were Duncan and John, the bulk of Column Headquarters, Tommy Blow and his platoon, Tommy Roberts and the bulk of the Support Platoon and Sergeant Thornborrow and the remnants of Philip Stibbe's Platoon. Missing were, Sergeant-Major Cairns, Pepper the runner, Lance Corporal Lee the column clerk, Foster and White the Signallers and one or two others. Cairns had last been seen helping Denny Sharp with all the animals and Foster, White and Lee were believed to have gone with the animals which carried their various bits of property.

I consoled my men by telling them that if any man was likely to get himself out of Burma, together with whoever was with him, it was Serjeant-Major Cairns."

Fergusson proved to be accurate in his thoughts and statement, as Jackie Cairns and the fifteen men from Column 5 present with him during the march through the Chinese Yunnan Borders in May/June 1943, did indeed survive and reach the safety of India once more. Reading through the Column 7 war diaries it would appear that Cairns worked alongside men such as Lieutenant Trigg of the Royal Engineers and led his own dispersal platoon which formed part of Major Gilkes's main party.

After reaching the Chinese city of Paoshan, Column 7 and the remaining men from Column 5 were airlifted back to India aboard USAAF Dakotas and went straight into hospital. After a period of rest and recuperation, Jackie Cairns and the other survivors of the 13th King's re-joined their comrades at the Napier Barracks in Karachi.

Seen below are two pages from the Column 7 war diary, describing the long trek out through the Yunnan Borders and Cairns contribution to the group. Also shown is the witness statement given by Quartermaster Sergeant Ernest Henderson in February 1944. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

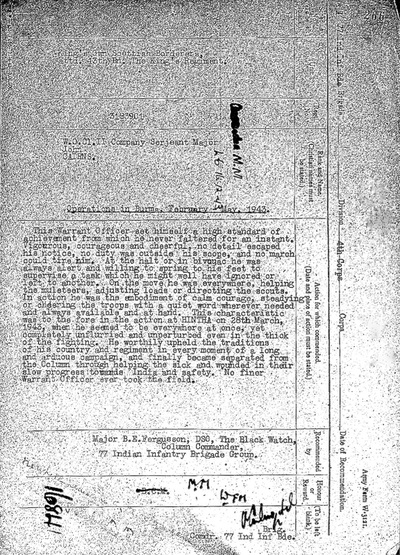

For his actions and leadership on Operation Longcloth, Sergeant-Major John Cairns was awarded the Military Medal. The award was recommended by his Column Commander, Major Bernard Fergusson, but one would imagine that Major Gilkes had some small involvement in the process too. Sergeant-Major Cairns received this award in early 1944, the presentation ceremony was held at the Napier Barracks in Karachi and the medal was presented by the then Viceroy of India, Archibald Wavell.

There follows a transcription of Bernard Fergusson's recommendation for the award of the Military Medal. The actual paper recommendation can be viewed in the final gallery seen below.

Award of the Military Medal to Company Sergeant-Major John Cairns

King's Own Scottish Borderer's (attached 13th Bn. The King's Regiment).

77th Indian Infantry Brigade, 4th Corps.

Action for which recommended :-

Operations in Burma, February - May 1943

This Warrant Officer set himself a high standard of achievements from which he never faltered for an instant. Vigorous, courageous and cheerful, no detail escaped his notice, no duty was outside his scope, and no march could tire him. At the halt or in bivouac he was always alert and willing to spring to his feet to supervise a task which he might well have ignored or left to another.

On the move he was everywhere, helping the muleteers, adjusting loads or directing the scouts. In action he was the embodiment of calm courage, steadying or cheering the troops with a quiet word wherever needed and always available and at hand. This characteristic was to the fore in the action at Hintha on 28th March 1943, when he seemed to be everywhere at once, yet completely unflurried and unperturbed even in the thick of the fighting.

He worthily upheld the traditions of his country and regiment in every moment of a long and arduous campaign, and finally became separated from the Column through helping the sick and wounded in their slow progress towards India and safety. No finer Warrant Officer ever took the field.

Recommended by. Major B. E. Fergusson DSO, Column Commander, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Honour or Reward. The Military Medal.

Signed by. Brigadier O. C. Wingate DSO.

Appeared in the London Gazette 16th December 1943.

I think the reader will agree that nothing further needs to be said in regards to Sergeant-Major Cairns. Seen below are some more images in relation to John Cairns and his time with the Chindits of 1943, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

There follows a transcription of Bernard Fergusson's recommendation for the award of the Military Medal. The actual paper recommendation can be viewed in the final gallery seen below.

Award of the Military Medal to Company Sergeant-Major John Cairns

King's Own Scottish Borderer's (attached 13th Bn. The King's Regiment).

77th Indian Infantry Brigade, 4th Corps.

Action for which recommended :-

Operations in Burma, February - May 1943

This Warrant Officer set himself a high standard of achievements from which he never faltered for an instant. Vigorous, courageous and cheerful, no detail escaped his notice, no duty was outside his scope, and no march could tire him. At the halt or in bivouac he was always alert and willing to spring to his feet to supervise a task which he might well have ignored or left to another.

On the move he was everywhere, helping the muleteers, adjusting loads or directing the scouts. In action he was the embodiment of calm courage, steadying or cheering the troops with a quiet word wherever needed and always available and at hand. This characteristic was to the fore in the action at Hintha on 28th March 1943, when he seemed to be everywhere at once, yet completely unflurried and unperturbed even in the thick of the fighting.

He worthily upheld the traditions of his country and regiment in every moment of a long and arduous campaign, and finally became separated from the Column through helping the sick and wounded in their slow progress towards India and safety. No finer Warrant Officer ever took the field.

Recommended by. Major B. E. Fergusson DSO, Column Commander, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Honour or Reward. The Military Medal.

Signed by. Brigadier O. C. Wingate DSO.

Appeared in the London Gazette 16th December 1943.

I think the reader will agree that nothing further needs to be said in regards to Sergeant-Major Cairns. Seen below are some more images in relation to John Cairns and his time with the Chindits of 1943, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 02/09/2015.

Some anecdotes and memories of John 'Jackie' Cairns, as told by his grandson Graeme McPhee.

John Cairns was born on the 23rd of August 1913 in Stranraer, Galloway in the extreme south west of Scotland, he was the second of four children; he had an older brother Andrew and younger brother Peter and sister Elizabeth (Betty). He described himself as an adventurous and curious child growing up in rural Galloway, but judging from the fact that he attended all of the local schools and was eventually sent to be schooled at a convent school in Ayr, unruly and wayward may be a better description.

He used to enjoy retelling stories of his time at the school in Ayr where he was the only Presbyterian at a Catholic school, not that faith played a particularly large part in his life at that time. On one occasion he was confined to standing behind the blackboard for some misdemeanour in the classroom and he could hardly contain his laughter as he told of how the young nun continued to teach the class writing on the blackboard; as she progressed the lesson and got closer towards the bottom of the blackboard he reached up and grabbed the top of the board and pulled it down hitting the nun and sending her tumbling to the floor much to the shock and amusement of the rest of the class. But he said he had to be fast as the nun was on here feet quickly grabbing her board pointer (which was as thick as a broom handle) and proceeded to chase him around the class.

"I remember the swish as she chased me around the class", exclaimed Jack. "Was she aiming for your legs Granpa?" I asked. "No my head " came the reply.

The 1920's in rural Scotland were a difficult time and Jack's older brother Andrew joined the Army as a boy soldier in 1922. He served with the Kings Own Scottish Borderer's, sending home most of his Army pay to help the family. Having left the school system, Jack took up work in a variety of jobs mostly in agriculture; then in 1928 at the age of 15 he joined the local TA unit, the 5th KOSB's, lying about his age in order to receive a man's wage, which again helped supplement the family's meagre income.

Eventually, he became a traction engine driver and as such toured all the farms in the south west of Scotland, which is noted by Bernard Fergusson in his book, Beyond the Chindwin. Fergusson recounts conversations between my grandfather and his (Fergusson's) batman, Peter Dorans, another native of the area, discussing of all things sheep prices whilst in the jungles of Burma.

In the early 1930's Jack started courting Mary (May) Murchison who worked in service for the Playfair family. The family spent part of the year in Scotland and the rest in London. This courtship didn't last due to the nature of May's work and moving around the country.

Jack continued to serve in the TA and enjoyed the summer camps and training. He was promoted to the rank of Sergeant and then Warrant Officer Class 2. As the clouds of war gathered in 1938 he was mobilised and employed at Jordanhill College in Glasgow, training officers in handling smalls arms.

With the outbreak of war, Jack applied for a posting to an active service unit, but this was refused as his experience was deemed of better use in training new recruits. During this time his elder brother Andrew, who had risen to Pipe-Major with the 2nd Battalion, King's Own Scottish Borderer's, was commissioned and seconded as a Captain to the 7th Battalion, the York and Lancaster Regiment.

The brothers had not spent a great deal of time together due to their Army service, but Jack recalled an occasion at Catterick during a court martial hearing, when one of the other officers commented that a previous case had also been brought by an officer with the surname Cairns. Upon enquiring of the officers regiment it turned out to be his brother Andrew, they had missed each other by a few short hours.

When telling this story, my Granpa would always remind me "If you are charging a man with an offence, make sure you double up the charges, that way if he doesn't get found guilty on the first you will always get him on the second." That being said, he was always known as a very fair NCO, albeit a stickler for detail.

Andrew was posted to France with the BEF, he was captured twice, but escaped on both occasions eventually returning to the UK via the Netherlands. He had sustained multiple injuries during this time and eventually succumbed to pneumonia on 2nd February 1942 aged just 34. He was laid to rest in a CWGC grave at Colinton Parish Churchyard in Edinburgh. Jack's younger brother Peter also served in WW2, he was with the Royal Highland Regiment (Black Watch), serving in North Africa with the 8th Army, then in Italy and finally Northern Europe.

NB. According to CWGC records the Cairns family wished to add the following epitaph to Andrew's headstone at Colinton:

He's asleep by thy murmuring stream; flow gently, sweet river, disturb not his dream."

I am not sure however, if this tribute has ever been added to the headstone. Seen below are photographs of the Colinton Parish Church and of Andrew's grave. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

To view Andrew's CWGC details, please click on the following link: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2451701/CAIRNS,%20ANDREW

Some anecdotes and memories of John 'Jackie' Cairns, as told by his grandson Graeme McPhee.

John Cairns was born on the 23rd of August 1913 in Stranraer, Galloway in the extreme south west of Scotland, he was the second of four children; he had an older brother Andrew and younger brother Peter and sister Elizabeth (Betty). He described himself as an adventurous and curious child growing up in rural Galloway, but judging from the fact that he attended all of the local schools and was eventually sent to be schooled at a convent school in Ayr, unruly and wayward may be a better description.

He used to enjoy retelling stories of his time at the school in Ayr where he was the only Presbyterian at a Catholic school, not that faith played a particularly large part in his life at that time. On one occasion he was confined to standing behind the blackboard for some misdemeanour in the classroom and he could hardly contain his laughter as he told of how the young nun continued to teach the class writing on the blackboard; as she progressed the lesson and got closer towards the bottom of the blackboard he reached up and grabbed the top of the board and pulled it down hitting the nun and sending her tumbling to the floor much to the shock and amusement of the rest of the class. But he said he had to be fast as the nun was on here feet quickly grabbing her board pointer (which was as thick as a broom handle) and proceeded to chase him around the class.

"I remember the swish as she chased me around the class", exclaimed Jack. "Was she aiming for your legs Granpa?" I asked. "No my head " came the reply.

The 1920's in rural Scotland were a difficult time and Jack's older brother Andrew joined the Army as a boy soldier in 1922. He served with the Kings Own Scottish Borderer's, sending home most of his Army pay to help the family. Having left the school system, Jack took up work in a variety of jobs mostly in agriculture; then in 1928 at the age of 15 he joined the local TA unit, the 5th KOSB's, lying about his age in order to receive a man's wage, which again helped supplement the family's meagre income.

Eventually, he became a traction engine driver and as such toured all the farms in the south west of Scotland, which is noted by Bernard Fergusson in his book, Beyond the Chindwin. Fergusson recounts conversations between my grandfather and his (Fergusson's) batman, Peter Dorans, another native of the area, discussing of all things sheep prices whilst in the jungles of Burma.

In the early 1930's Jack started courting Mary (May) Murchison who worked in service for the Playfair family. The family spent part of the year in Scotland and the rest in London. This courtship didn't last due to the nature of May's work and moving around the country.

Jack continued to serve in the TA and enjoyed the summer camps and training. He was promoted to the rank of Sergeant and then Warrant Officer Class 2. As the clouds of war gathered in 1938 he was mobilised and employed at Jordanhill College in Glasgow, training officers in handling smalls arms.

With the outbreak of war, Jack applied for a posting to an active service unit, but this was refused as his experience was deemed of better use in training new recruits. During this time his elder brother Andrew, who had risen to Pipe-Major with the 2nd Battalion, King's Own Scottish Borderer's, was commissioned and seconded as a Captain to the 7th Battalion, the York and Lancaster Regiment.

The brothers had not spent a great deal of time together due to their Army service, but Jack recalled an occasion at Catterick during a court martial hearing, when one of the other officers commented that a previous case had also been brought by an officer with the surname Cairns. Upon enquiring of the officers regiment it turned out to be his brother Andrew, they had missed each other by a few short hours.

When telling this story, my Granpa would always remind me "If you are charging a man with an offence, make sure you double up the charges, that way if he doesn't get found guilty on the first you will always get him on the second." That being said, he was always known as a very fair NCO, albeit a stickler for detail.

Andrew was posted to France with the BEF, he was captured twice, but escaped on both occasions eventually returning to the UK via the Netherlands. He had sustained multiple injuries during this time and eventually succumbed to pneumonia on 2nd February 1942 aged just 34. He was laid to rest in a CWGC grave at Colinton Parish Churchyard in Edinburgh. Jack's younger brother Peter also served in WW2, he was with the Royal Highland Regiment (Black Watch), serving in North Africa with the 8th Army, then in Italy and finally Northern Europe.

NB. According to CWGC records the Cairns family wished to add the following epitaph to Andrew's headstone at Colinton:

He's asleep by thy murmuring stream; flow gently, sweet river, disturb not his dream."

I am not sure however, if this tribute has ever been added to the headstone. Seen below are photographs of the Colinton Parish Church and of Andrew's grave. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

To view Andrew's CWGC details, please click on the following link: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2451701/CAIRNS,%20ANDREW

Through the early years of the war Jack continued to apply for a posting to an active service unit, but still to no avail. Around this time he had the good fortune to bump into May Murchison. This chance encounter renewed the courtship and they married in 1940. Jack was eventually granted his wish of an active service roll and was attached to the 13th Kings; he was immensely proud of his parent regiment (KOSB) and said the only reason he agreed to go was because he was attached to the King's and not transferred.

Jack would recount various tales about his time with the King's prior to going to India, mostly involving catching men out of barracks drinking etc. All these stories ended with a comic twist. I remember him telling of the time en route to India when the ship stopped in Durban, there was a near riot as the some of the senior NCO's had decided to go for a drink in a local bar far away from the majority of the men, to give themselves their own space to let off a bit of steam after the voyage from the UK. Part way through the session the South African Police arrived and started to smash the pub up as it was a coloured only establishment unbeknown to the NCO's, who took umbrage to their session being interrupted.

Jack's service in India/Burma is well detailed on the rest of your site and he never really spoke of events in combat, but would recall funny events and unusual happenings: paying the Naga headhunters for Japanese heads, sitting in the jungle with the local tribes drinking their version of home brew made from the sap of trees, eating snakes and most bizarrely of all monkeys paws which he said were incredibly sweet.

He did tell the story of his return to India after the break up from No. 5 Column, after organising stragglers and the injured, he and several others eventually made it out to China. By this time they were emaciated, with their uniforms in rags and riddled with malaria, they had used all the quinine tablets and were on their last legs when they encountered some local Chinese who gave them the bark of the Cinchona tree to chew. They were eventually flown back to India by the Americans, Jack said the Americans didn't want to take them back to India as the men were riddled with malaria, "so how did you get back" I asked, "diplomacy at the end of a gun" he replied. They made it back but he never expanded on the story and was always rather terse about the American airforce thereafter.

During his time away from the UK, May, who was pregnant gave birth to his daughter Mary (Maisie) in January 1942. It would be six years before Jack returned home to see her. When Maisie was growing up she would kiss the picture of her daddy in his slouch hat every night before she went to bed, but when Jack came home Maisie ran away from him, whether it was because he wasn't wearing a slouch hat or because he was in colour instead of black and white I don't know. Upon leaving the service he started work for Weir Homes as a Saw Doctor, he attended College in Glasgow to get the appropriate training and qualifications and continued to work there until he retired in 1977.

Work aside, May and Jack were blessed with a second daughter called Elizabeth; Maisie who was born when Jack was oversees and was named after her mother, grandmother and great-grandmother. Jack, who was at work when Elizabeth was born was sent to the local registrar to register the birth upon his return home. On the ten minute walk from the family home to the registry office, Jack decided that Margaret, his mothers name would be far more appropriate, so from that day to this she is Margaret Elizabeth and known as Margaret.

Jack continued to work at Weirs as a Saw Doctor and was also the union shop steward, but he was a committed Conservative voter as he said they are the party of business and its business that pays the wages and keeps the family. A third daughter named Angela was soon to join the growing family, again born while Jack was at work, so upon his return he was again despatched to the registry office, but this time with a written note stating the name: Angela Catherine Cairns.

As it was raining that day the note was somewhat wet when he arrived at the registry office and not exactly recalling what was on the note and with the hope of a son looking less and less likely, he plumped for Joan, as this was close enough to John. So my mum was called Joan Catherine Cairns; at least he was showing improvement on this occasion, getting the name half correct.

This is not the end of the expanding Cairns family, a year after Joan was born a son duly arrived; again Jack was at work and again note in hand he was sent to register the birth of Cameron John Cairns, but for some reason the registrar made a mistake and recorded the name as John Cameron Cairns; this was the last straw for May who insisted that: "his first name might be John but I'm calling him Cameron," and that is the name by which he was known.

Granpa was a very astute and caring man, my gran would recount the story of when, one Saturday morning, Jack brought one of the apprentices from Weirs home for his breakfast. May had made ham and eggs and sausages which they sat down to eat, after a few minutes Jack realised that the apprentice wasn't eating and quick as a flash asked May for bread and butter and proceeded to put his breakfast on the bread; the apprentice didn't know how to use a knife and fork which seems alien now, but I am told was common place back then. Not a word was said but the apprentice followed suit and the breakfast was consumed minus knife and fork.

As mentioned previously, Jack never spoke about the war and a lot of vestiges of his time with the colours were packed away in boxes or thrown away. He did keep up infrequently with his old comrades, my mum recalls letters from William Livingstone and John Thornborrow. He was a member of the Burma Star Association, but was not one for attending meeting or commemorations, his medals spent many years gathering dust in a drawer. However, one of his most treasured possessions was a silver tankard engraved 'J. Cairns Burma 1943, this was presented to him by the men with an additional handwritten note "To a great Sergeant No. 5 Plt".

Below is a well known sketch of Jack's old comrade from 5 Column, Sergeant John Thornborrow. This image can be found in the book 'Return via Rangoon', written by the former 5 Column officer, Lieutenant Philip Stibbe. Also shown is a photograph of William Livingstone, taken at Secunderabad in 1942 and an image from the Orderly Room at the Napier Barracks in Karachi (1944). Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Jack would recount various tales about his time with the King's prior to going to India, mostly involving catching men out of barracks drinking etc. All these stories ended with a comic twist. I remember him telling of the time en route to India when the ship stopped in Durban, there was a near riot as the some of the senior NCO's had decided to go for a drink in a local bar far away from the majority of the men, to give themselves their own space to let off a bit of steam after the voyage from the UK. Part way through the session the South African Police arrived and started to smash the pub up as it was a coloured only establishment unbeknown to the NCO's, who took umbrage to their session being interrupted.

Jack's service in India/Burma is well detailed on the rest of your site and he never really spoke of events in combat, but would recall funny events and unusual happenings: paying the Naga headhunters for Japanese heads, sitting in the jungle with the local tribes drinking their version of home brew made from the sap of trees, eating snakes and most bizarrely of all monkeys paws which he said were incredibly sweet.

He did tell the story of his return to India after the break up from No. 5 Column, after organising stragglers and the injured, he and several others eventually made it out to China. By this time they were emaciated, with their uniforms in rags and riddled with malaria, they had used all the quinine tablets and were on their last legs when they encountered some local Chinese who gave them the bark of the Cinchona tree to chew. They were eventually flown back to India by the Americans, Jack said the Americans didn't want to take them back to India as the men were riddled with malaria, "so how did you get back" I asked, "diplomacy at the end of a gun" he replied. They made it back but he never expanded on the story and was always rather terse about the American airforce thereafter.

During his time away from the UK, May, who was pregnant gave birth to his daughter Mary (Maisie) in January 1942. It would be six years before Jack returned home to see her. When Maisie was growing up she would kiss the picture of her daddy in his slouch hat every night before she went to bed, but when Jack came home Maisie ran away from him, whether it was because he wasn't wearing a slouch hat or because he was in colour instead of black and white I don't know. Upon leaving the service he started work for Weir Homes as a Saw Doctor, he attended College in Glasgow to get the appropriate training and qualifications and continued to work there until he retired in 1977.

Work aside, May and Jack were blessed with a second daughter called Elizabeth; Maisie who was born when Jack was oversees and was named after her mother, grandmother and great-grandmother. Jack, who was at work when Elizabeth was born was sent to the local registrar to register the birth upon his return home. On the ten minute walk from the family home to the registry office, Jack decided that Margaret, his mothers name would be far more appropriate, so from that day to this she is Margaret Elizabeth and known as Margaret.

Jack continued to work at Weirs as a Saw Doctor and was also the union shop steward, but he was a committed Conservative voter as he said they are the party of business and its business that pays the wages and keeps the family. A third daughter named Angela was soon to join the growing family, again born while Jack was at work, so upon his return he was again despatched to the registry office, but this time with a written note stating the name: Angela Catherine Cairns.

As it was raining that day the note was somewhat wet when he arrived at the registry office and not exactly recalling what was on the note and with the hope of a son looking less and less likely, he plumped for Joan, as this was close enough to John. So my mum was called Joan Catherine Cairns; at least he was showing improvement on this occasion, getting the name half correct.

This is not the end of the expanding Cairns family, a year after Joan was born a son duly arrived; again Jack was at work and again note in hand he was sent to register the birth of Cameron John Cairns, but for some reason the registrar made a mistake and recorded the name as John Cameron Cairns; this was the last straw for May who insisted that: "his first name might be John but I'm calling him Cameron," and that is the name by which he was known.

Granpa was a very astute and caring man, my gran would recount the story of when, one Saturday morning, Jack brought one of the apprentices from Weirs home for his breakfast. May had made ham and eggs and sausages which they sat down to eat, after a few minutes Jack realised that the apprentice wasn't eating and quick as a flash asked May for bread and butter and proceeded to put his breakfast on the bread; the apprentice didn't know how to use a knife and fork which seems alien now, but I am told was common place back then. Not a word was said but the apprentice followed suit and the breakfast was consumed minus knife and fork.

As mentioned previously, Jack never spoke about the war and a lot of vestiges of his time with the colours were packed away in boxes or thrown away. He did keep up infrequently with his old comrades, my mum recalls letters from William Livingstone and John Thornborrow. He was a member of the Burma Star Association, but was not one for attending meeting or commemorations, his medals spent many years gathering dust in a drawer. However, one of his most treasured possessions was a silver tankard engraved 'J. Cairns Burma 1943, this was presented to him by the men with an additional handwritten note "To a great Sergeant No. 5 Plt".

Below is a well known sketch of Jack's old comrade from 5 Column, Sergeant John Thornborrow. This image can be found in the book 'Return via Rangoon', written by the former 5 Column officer, Lieutenant Philip Stibbe. Also shown is a photograph of William Livingstone, taken at Secunderabad in 1942 and an image from the Orderly Room at the Napier Barracks in Karachi (1944). Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

When he eventually retired in 1977 he purchased a holiday home in Stranraer and spent half the year there and half the year in Airdrie. As well as raising his his own children he also had six grandchildren, myself Graeme, John, Vicki, Cameron, Douglas and Cameron, he was also fortunate enough to meet his great grandson Ryan. He had a massive impact on all his grandchildren and through country walks would tell us what plants were which, what could be eaten, how to start a fire without matches and lots of other field craft techniques, but it was all done in a wonderfully casual manner and for us it was all great fun. Every week until we were 16 he would give us our 'wages', which was the equivalent of an apprentices pay, but we had to go and visit him to get them, thus ensuring himself plenty of visitors.

He was spiritual in his own way and had great faith but not much time for organised religion. The example he gave was of a train-station platform in India; sitting waiting on a train with the sun beating down, there were water fountains up and down the platform, separate water fountains for Christians, all the Hindu casts, Muslims, Sihks etc. He said it was while sitting watching the comings and goings at these water fountains that he finally got religion; the fountains were the creation of man, but they were all fed from the same pipe running under the platform. In Scotland we say, we are all Jock Tamson's bairns (we are all gods children).

He enjoyed his retirement but most of all he loved his family, if he could have had us all living under one roof that would have been him happy, he loved us all being together at the one time. May passed away in 1993 she had been married to Jack for over 50 years, he was heart broken at the loss of his life long love, but still had the inner strength to stop and console the mourners at her funeral, telling them that they should be happy that they spent time with her and not be sad now that she was gone.

Being fair skinned and having worked outside for most of his life he had to attend hospital in his later years for operations due to skin cancer, including having his left ear removed, but as with everything else this never got him down; the consultant asked if he would like to be fitted with a prosthetic ear which would save embarrassing looks in public. Jack thought about this for a minute then said "well, now I'm on my own I do like to stop and talk to the women in Morrisons, but on second thoughts it might fall off and the poor wee woman would have a heart attack and where would I be then."

As he got older his health got worse and his trips to Galloway became less frequent, after a battle against cancer he passed away March 2001. Following his radiotherapy treatment he had been in hospital for several weeks and towards the end had not spoken and barely opened his eyes for days. The last time I visited him was on the Sunday afternoon, I sat and read my book while my mum and aunts read and talked to their daddy. I had to leave eventually and got up to kiss him good bye and tell him how much I loved him, he held my arm opened his eyes and said "I will see you later son." He passed away later that night with his family around him.

He had a massive impact on all of our lives, his Army service was part of him but it did not define him. Every day I still think of him and especially on his birthday, the 23rd of August, which happens to also be my birthday. Once a Borderer, always a Borderer.

I would like to this opportunity to thank Graeme for his wonderfully personal and heartfelt memories in relation to his grandfather.

Update 04/05/2019.

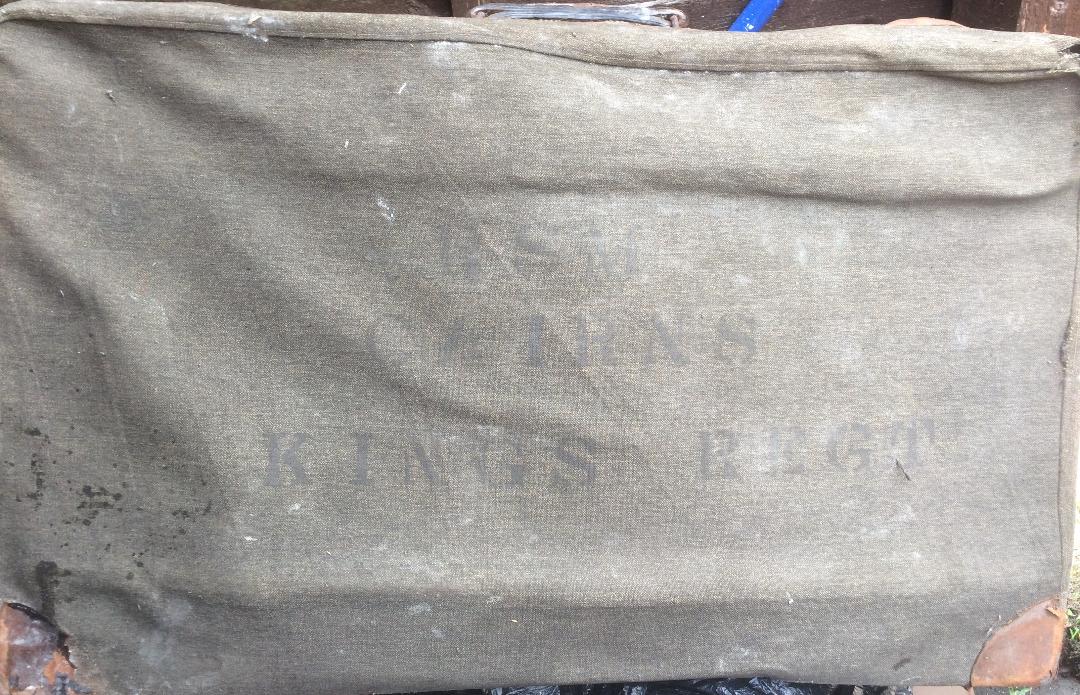

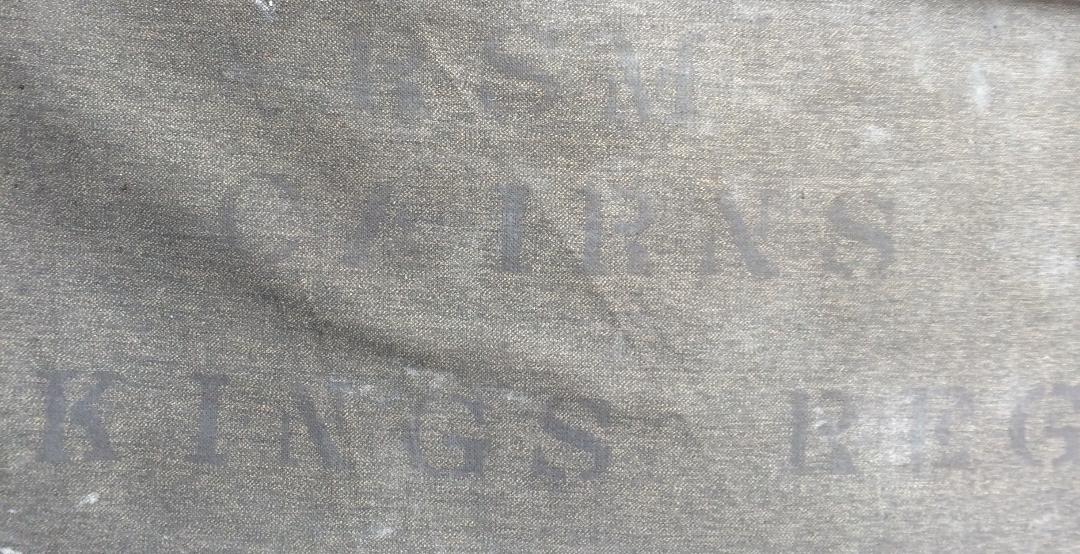

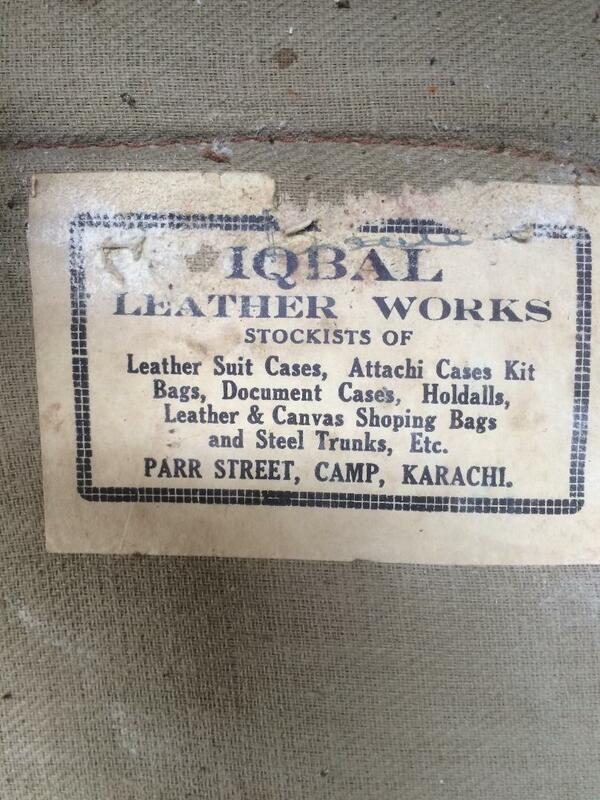

I recently received a new email contact from Graeme McPhee, the grandson of Jackie Cairns. Included in the email were three photographs of his grandfather's old Army luggage/kit bag, including the now rather faint naming, which had been stencilled on to the material way back in 1943/44 when the 13th King's were stationed at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. The fact that the items are still intact and the labelling can still be read, pays tribute to the Indian workers that made them. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

He was spiritual in his own way and had great faith but not much time for organised religion. The example he gave was of a train-station platform in India; sitting waiting on a train with the sun beating down, there were water fountains up and down the platform, separate water fountains for Christians, all the Hindu casts, Muslims, Sihks etc. He said it was while sitting watching the comings and goings at these water fountains that he finally got religion; the fountains were the creation of man, but they were all fed from the same pipe running under the platform. In Scotland we say, we are all Jock Tamson's bairns (we are all gods children).

He enjoyed his retirement but most of all he loved his family, if he could have had us all living under one roof that would have been him happy, he loved us all being together at the one time. May passed away in 1993 she had been married to Jack for over 50 years, he was heart broken at the loss of his life long love, but still had the inner strength to stop and console the mourners at her funeral, telling them that they should be happy that they spent time with her and not be sad now that she was gone.

Being fair skinned and having worked outside for most of his life he had to attend hospital in his later years for operations due to skin cancer, including having his left ear removed, but as with everything else this never got him down; the consultant asked if he would like to be fitted with a prosthetic ear which would save embarrassing looks in public. Jack thought about this for a minute then said "well, now I'm on my own I do like to stop and talk to the women in Morrisons, but on second thoughts it might fall off and the poor wee woman would have a heart attack and where would I be then."

As he got older his health got worse and his trips to Galloway became less frequent, after a battle against cancer he passed away March 2001. Following his radiotherapy treatment he had been in hospital for several weeks and towards the end had not spoken and barely opened his eyes for days. The last time I visited him was on the Sunday afternoon, I sat and read my book while my mum and aunts read and talked to their daddy. I had to leave eventually and got up to kiss him good bye and tell him how much I loved him, he held my arm opened his eyes and said "I will see you later son." He passed away later that night with his family around him.

He had a massive impact on all of our lives, his Army service was part of him but it did not define him. Every day I still think of him and especially on his birthday, the 23rd of August, which happens to also be my birthday. Once a Borderer, always a Borderer.

I would like to this opportunity to thank Graeme for his wonderfully personal and heartfelt memories in relation to his grandfather.

Update 04/05/2019.

I recently received a new email contact from Graeme McPhee, the grandson of Jackie Cairns. Included in the email were three photographs of his grandfather's old Army luggage/kit bag, including the now rather faint naming, which had been stencilled on to the material way back in 1943/44 when the 13th King's were stationed at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. The fact that the items are still intact and the labelling can still be read, pays tribute to the Indian workers that made them. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, December 2014.