Dalbahadur Pun and the death of Major Conron.

Regimental Banner of 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

Regimental Banner of 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

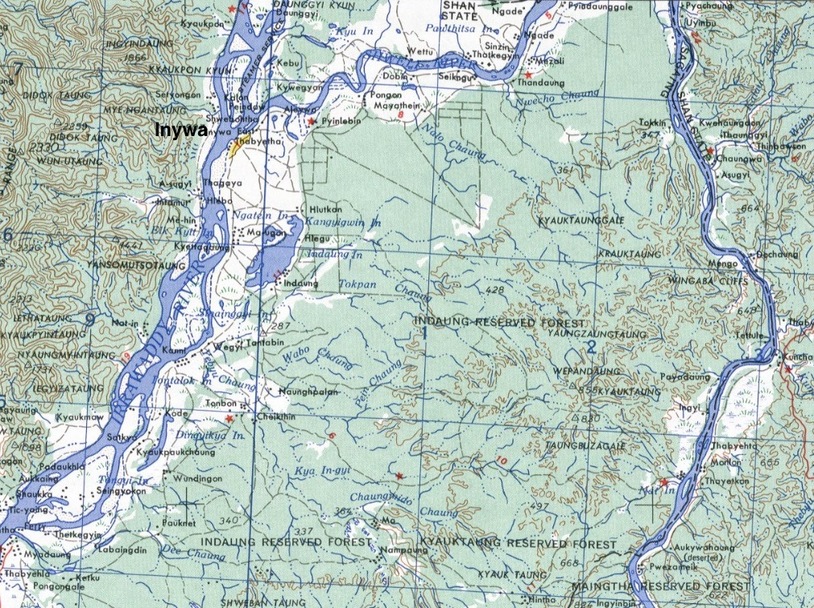

Dalbahadur Pun was most likely a part of Chindit Column number 1 on Operation Longcloth. The evidence strongly points towards this, especially with his mention of 'Weatherall sahib' as being a commander and his presence at the Irrawaddy and Shweli River crossings. However, it is possible that he may have been a member of the ill-fated number 2 Column and that after their disastrous contact with the Japanese at the rail station at Kyaikthin, managed to move forward to the agreed rendezvous location and join up with Column 1 there.

Regardless of which Chindit unit he may have been with, the most important element of his story is the close proximity of Dalbahadur to the place where Major Conron lost his life and how this may of occurred. But more of that later.

Here is his testimony:

From Manipur we invaded Burma in Wingate's column. I remember a big battle (possibly the Kyaikthin rail station action) when our ammunition finished and we had no re-supply. We were told to make our own way back to India. It was an unpleasant situation. Weatherall sahib, who spoke very good Khaskura, had been killed and we were surrounded by Japanese and had been in Burma for three months. NB. Dalbahadur moves his account swiftly onward to the time around early April 1943 when most of the Chindit personnel were attempting to return to the relative safety of the Chindwin River.

We searched for jungle produce, especially yams, to eat. We tried to buy food in Burmese villages with "king's money" that had been dropped in to us with the earlier rations. There were mosquitoes everywhere. NB. All Chindit officers and men were issued with silver rupees, Wingate felt that this coinage would be able to recruit the help of local villagers far more than the almost worthless Japanese paper equivalent.

Our clothes were in rags, footwear was worn out and our feet were in a bad state. Our hair hung down our shoulders. Those who were too sick to move were left with some money near Burmese villages or left to die where they were. I, a machine gunner, was with two Gurkha Officers. We dumped our weapons. The officers wanted to surrender but I said "No, let's escape or die. If we stay alive we'll meet in India, if we die, we'll die here." We soon separated.

I reached the Irrawaddy (I think that Dalbahadur probably means the Shweli, but the two rivers were very close to each other at this point and it would be very easy to mix them up) and the problem was how to cross over. Just short of the near bank in the jungle I met Major Conron who had a biscuit in one hand and a life jacket in the other. He asked me where I had come from, where the Subedar and the other Gurkha Officers were, and where was my machine gun. I told him I didn't know where the officers were. He said "What's gone has gone. You and I have to cross the river. Let's go together. If we live we live, if we die we die." He was so weak he could not swim so I went to look for a boatman.

Regardless of which Chindit unit he may have been with, the most important element of his story is the close proximity of Dalbahadur to the place where Major Conron lost his life and how this may of occurred. But more of that later.

Here is his testimony:

From Manipur we invaded Burma in Wingate's column. I remember a big battle (possibly the Kyaikthin rail station action) when our ammunition finished and we had no re-supply. We were told to make our own way back to India. It was an unpleasant situation. Weatherall sahib, who spoke very good Khaskura, had been killed and we were surrounded by Japanese and had been in Burma for three months. NB. Dalbahadur moves his account swiftly onward to the time around early April 1943 when most of the Chindit personnel were attempting to return to the relative safety of the Chindwin River.

We searched for jungle produce, especially yams, to eat. We tried to buy food in Burmese villages with "king's money" that had been dropped in to us with the earlier rations. There were mosquitoes everywhere. NB. All Chindit officers and men were issued with silver rupees, Wingate felt that this coinage would be able to recruit the help of local villagers far more than the almost worthless Japanese paper equivalent.

Our clothes were in rags, footwear was worn out and our feet were in a bad state. Our hair hung down our shoulders. Those who were too sick to move were left with some money near Burmese villages or left to die where they were. I, a machine gunner, was with two Gurkha Officers. We dumped our weapons. The officers wanted to surrender but I said "No, let's escape or die. If we stay alive we'll meet in India, if we die, we'll die here." We soon separated.

I reached the Irrawaddy (I think that Dalbahadur probably means the Shweli, but the two rivers were very close to each other at this point and it would be very easy to mix them up) and the problem was how to cross over. Just short of the near bank in the jungle I met Major Conron who had a biscuit in one hand and a life jacket in the other. He asked me where I had come from, where the Subedar and the other Gurkha Officers were, and where was my machine gun. I told him I didn't know where the officers were. He said "What's gone has gone. You and I have to cross the river. Let's go together. If we live we live, if we die we die." He was so weak he could not swim so I went to look for a boatman.

Dalbahadur continues:

It was evening. I went to a house and all inside were very scared. I pulled one man out and took him back. He trembled a lot. The Major put his pistol to the Burman's head and told him either to take us across in his boat "Or I'll kill you here." That made the Burman even more scared. He put us in his boat and started rowing us across. There was just enough moonlight to see forwards. We finished up on the other side exactly opposite a Japanese post.

They opened fire on us and killed the Major. I was unhurt. It was around 0100 hours and I started walking. At the top of a bamboo-covered hill I stopped. I was worried; the Major was dead and I was by myself. We had come 700 miles from India. How was I to go back the same distance. I had a compass. At Imphal we had been told that if we had to escape we were to march on a bearing of 300 degrees to reach Manipur.

I started on 300 degrees and moved between 300 degrees and 310 degrees. It would still take me a long time to reach India once more. That night it was moonlit and I sat down to rest under a tree and got covered in red ants. Did they bite!

I had to avoid the Burmans at all costs as they would have speared me to death. They had already killed many of us that way as I had seen for myself. I was afraid of being captured by the Japanese, but was also afraid of one animal, a ferocious type of deer that was big, red and horned. I knew it would attack any human it smelled. I was only once attacked by one and I escaped by hiding under a large fallen tree.

I saw many tigers. The first one I saw did frighten me, but I managed to jump into a river and swim across. Then I nearly bumped into a group of Burmese, who were all smoking. They didn't see me but they would have killed me had they caught me. When I came across other tigers they took no notice of me. I put that down to the fact that my body smell was different by then. They do not have a sense of smell but have good eyesight. Bears, on the other hand, have dim sight but a good sense of smell. I only saw the red-nosed bear in Burma, not the black-nosed type we have in Nepal.

Once, trying to cross a broken railway bridge, I came across a group of Japanese riding on elephants and I hid from them. One evening I was fascinated to find myself in the middle of a large herd of deer. By then I was always hungry. I started fishing with my hands in one river and caught some prawns which I ate immediately, as I did two fish I caught in a teeming pool formed by the monsoon at the side of another river. I scooped some out and ate them alive also. There was no salt but they were good.

It was evening. I went to a house and all inside were very scared. I pulled one man out and took him back. He trembled a lot. The Major put his pistol to the Burman's head and told him either to take us across in his boat "Or I'll kill you here." That made the Burman even more scared. He put us in his boat and started rowing us across. There was just enough moonlight to see forwards. We finished up on the other side exactly opposite a Japanese post.

They opened fire on us and killed the Major. I was unhurt. It was around 0100 hours and I started walking. At the top of a bamboo-covered hill I stopped. I was worried; the Major was dead and I was by myself. We had come 700 miles from India. How was I to go back the same distance. I had a compass. At Imphal we had been told that if we had to escape we were to march on a bearing of 300 degrees to reach Manipur.

I started on 300 degrees and moved between 300 degrees and 310 degrees. It would still take me a long time to reach India once more. That night it was moonlit and I sat down to rest under a tree and got covered in red ants. Did they bite!

I had to avoid the Burmans at all costs as they would have speared me to death. They had already killed many of us that way as I had seen for myself. I was afraid of being captured by the Japanese, but was also afraid of one animal, a ferocious type of deer that was big, red and horned. I knew it would attack any human it smelled. I was only once attacked by one and I escaped by hiding under a large fallen tree.

I saw many tigers. The first one I saw did frighten me, but I managed to jump into a river and swim across. Then I nearly bumped into a group of Burmese, who were all smoking. They didn't see me but they would have killed me had they caught me. When I came across other tigers they took no notice of me. I put that down to the fact that my body smell was different by then. They do not have a sense of smell but have good eyesight. Bears, on the other hand, have dim sight but a good sense of smell. I only saw the red-nosed bear in Burma, not the black-nosed type we have in Nepal.

Once, trying to cross a broken railway bridge, I came across a group of Japanese riding on elephants and I hid from them. One evening I was fascinated to find myself in the middle of a large herd of deer. By then I was always hungry. I started fishing with my hands in one river and caught some prawns which I ate immediately, as I did two fish I caught in a teeming pool formed by the monsoon at the side of another river. I scooped some out and ate them alive also. There was no salt but they were good.

Dalbahadur's story concludes:

I once came across a nest of 12 eggs of jungle fowl. I ate six straightaway and kept the other six for later. I came across a nest of two young doves. I killed one, plucked it and ate it raw as I had no method of making fire, I kept the other bird for later. After one spell of three or four days without any food I came across a Burmese village. The Burmans were afraid of me and ran away. I found some dried maize and carried as much as I could away with me.

The Burmans were very scared of the Japanese. The Japanese would come and check on such things as the number of chickens or eggs and if the amount was inexplicably less punishments were meted out, sometimes extra work for the people or even death. Women suffered badly; they would be gang raped and then stabbed to death.

I was happy to find wood apples which were most sustaining. They kept hunger away for up to three days. The fruit of the ebony tree only kept hunger away for 12 hours. One day I came across three boxes of cigarettes that had been dropped from an aircraft, so I knew I was on the correct path. Three months after I started back I saw a 3/5 Gurkha Rifle post on the far bank of the Chindwin, with artillery near by. 1/8 GR was to one flank. They knew about our column. A British Captain aimed his weapon at me as I approached the near bank. I waved a leaf at him hoping he'd take that as a recognition sign. He signalled to me to stay there and a boat came over to fetch me.

In great haste I got into the boat and when we reached midstream firing broke out from both sides of the river, British and Japanese. I felt I was finished. I almost collapsed when I reached the bank and the Captain sahib pulled me into the safety of dead ground. He gave me a drink of rum from his water bottle. I drank it. I was told to hide there and food and drink would be brought to me. I stayed in a trench.

The sahib spoke good Khaskura and gave me a towel. My morale soared. I had not had a rice meal for three months so when some was brought I ate four mess tins and slept for the rest of the day. That evening the Captain came to see how I was and woke me up. He told me he had contacted battalion HQ and I had to report there. This might be difficult, as reports from an agent had been received indicating an enemy attack.

I was to be sent by mule with an escort squad as I had sore feet, but I did not know how to ride a mule so I went by foot. At battalion HQ the Medical Officer looked at my feet. I was not allowed to stay there because of the attack so I was sent on to 3/3 GR. I got there in the evening. I was told how dangerous it was so I would have to move on. I had a Havildar cousin in 3/3 GR and I told them his number and asked if I could see him. He died in 1998 aged 87. I did spent the night there. There were three attacks over the next three days but next morning 3/3 GR contacted Imphal by telephone and I was sent there.

I met Bain sahib who had raised 3/2 GR and was now a Colonel. He asked me if I knew him and I said I did, telling him his name. He asked me all about what had happened to 3/2 GR and I told him as much as I knew, which was not much. Of the 1,700 men of the original column only 665 had returned to Imphal. I made the total 666. I was given a medical inspection, re-equipped and, with the other Gurkhas, sent back to Dehra Dun.

NB. The officer mentioned by Dalbahadur was the then Lieutenant-Colonel, George Alexander Bain. This officer had been 3/2 GR's Brigade-Major in 1939 and had been with the 2nd Gurkha Rifles since WW1. He was to command the 64th Indian Infantry Brigade later in the war.

I would like to thank John P. Cross once again for permission to reproduce the story of Dalbahadur Pun from his book 'Gurkhas at War'. To hear more about the adventures of Dalbahadur, click on the link below, which will take you to his Imperial War Museum audio interview recorded in 2002:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80025555

I once came across a nest of 12 eggs of jungle fowl. I ate six straightaway and kept the other six for later. I came across a nest of two young doves. I killed one, plucked it and ate it raw as I had no method of making fire, I kept the other bird for later. After one spell of three or four days without any food I came across a Burmese village. The Burmans were afraid of me and ran away. I found some dried maize and carried as much as I could away with me.

The Burmans were very scared of the Japanese. The Japanese would come and check on such things as the number of chickens or eggs and if the amount was inexplicably less punishments were meted out, sometimes extra work for the people or even death. Women suffered badly; they would be gang raped and then stabbed to death.

I was happy to find wood apples which were most sustaining. They kept hunger away for up to three days. The fruit of the ebony tree only kept hunger away for 12 hours. One day I came across three boxes of cigarettes that had been dropped from an aircraft, so I knew I was on the correct path. Three months after I started back I saw a 3/5 Gurkha Rifle post on the far bank of the Chindwin, with artillery near by. 1/8 GR was to one flank. They knew about our column. A British Captain aimed his weapon at me as I approached the near bank. I waved a leaf at him hoping he'd take that as a recognition sign. He signalled to me to stay there and a boat came over to fetch me.

In great haste I got into the boat and when we reached midstream firing broke out from both sides of the river, British and Japanese. I felt I was finished. I almost collapsed when I reached the bank and the Captain sahib pulled me into the safety of dead ground. He gave me a drink of rum from his water bottle. I drank it. I was told to hide there and food and drink would be brought to me. I stayed in a trench.

The sahib spoke good Khaskura and gave me a towel. My morale soared. I had not had a rice meal for three months so when some was brought I ate four mess tins and slept for the rest of the day. That evening the Captain came to see how I was and woke me up. He told me he had contacted battalion HQ and I had to report there. This might be difficult, as reports from an agent had been received indicating an enemy attack.

I was to be sent by mule with an escort squad as I had sore feet, but I did not know how to ride a mule so I went by foot. At battalion HQ the Medical Officer looked at my feet. I was not allowed to stay there because of the attack so I was sent on to 3/3 GR. I got there in the evening. I was told how dangerous it was so I would have to move on. I had a Havildar cousin in 3/3 GR and I told them his number and asked if I could see him. He died in 1998 aged 87. I did spent the night there. There were three attacks over the next three days but next morning 3/3 GR contacted Imphal by telephone and I was sent there.

I met Bain sahib who had raised 3/2 GR and was now a Colonel. He asked me if I knew him and I said I did, telling him his name. He asked me all about what had happened to 3/2 GR and I told him as much as I knew, which was not much. Of the 1,700 men of the original column only 665 had returned to Imphal. I made the total 666. I was given a medical inspection, re-equipped and, with the other Gurkhas, sent back to Dehra Dun.

NB. The officer mentioned by Dalbahadur was the then Lieutenant-Colonel, George Alexander Bain. This officer had been 3/2 GR's Brigade-Major in 1939 and had been with the 2nd Gurkha Rifles since WW1. He was to command the 64th Indian Infantry Brigade later in the war.

I would like to thank John P. Cross once again for permission to reproduce the story of Dalbahadur Pun from his book 'Gurkhas at War'. To hear more about the adventures of Dalbahadur, click on the link below, which will take you to his Imperial War Museum audio interview recorded in 2002:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80025555

The death of Major Philip Conron

Major Philip Alfred Ronayne Conron

Born 21st November 1902.

First Commission 31st August 1922.

Lieutenant/Indian Army 30th November 1924.

Attained the rank of Captain 31st August 1931.

Specialist in small arms weaponry and became an Instructor in 1938.

Died close to or whilst crossing the Shweli River on 3rd April 1943.

Brigadier Wingate had not been overly impressed by the performance of his Gurkha troops in either training, or the early weeks of Operation Longcloth, perhaps with the notable exception of Mike Calvert's Column 3. The vast majority of Gurkha Columns 2 and 4 had returned to India early on after meeting the Japanese in combat, deciding on dispersal to the rear, rather than following the Brigadier's instruction to always move forward. He had also planned for Southern Group to liaise with a special scouting mission in the Kachin Hills led by Captain 'Fish' Herring. The rendezvous date of 29th March was missed, but presumably this was only due to the unexpected engagement with the Japanese at Kyaikthin rail station which had caught out Column 2 so disastrously.

I feel that the criticism aimed at 3/2 Gurkha was extremely harsh, they were after all a very young and inexperienced battalion, who had endured many 'last minute' changes to both leadership and command. I do wonder if Wingate was sub-consciously venting his obvious frustrations against the Indian General Command and their overt lack of support for his Chindit program and theories. Did he take these frustrations out on the commanders of the Gurkha Columns in 1943?

According to Mountbatten, Wingate had caused great offence in New Delhi, by describing the Indian Army as 'the largest unemployed relief organisation in the world', and made it clear that under no circumstances would he want Indian soldiers under his command. In particular he disliked the close, almost mystical, family relationship which existed between the officers and men of most Indian Army Regiments. Of course this was particularly true in the case of the Gurkhas.

The Gurkhas in turn did not like the way in which Wingate treated their officers in public. Early on in Saugor, while preparing the training regime, Wingate insisted that all officers should run from one position to the next and angrily berated those who could not keep up with him. To the Gurkha soldiers, schooled in a tradition of mutual respect, this was thoroughly disagreeable and they detested seeing their officers lose face in such a public way.

Wingate was the only British Officer in more than 130 years to criticise the performance of Gurkha soldiers, characterising them as mentally unsuited for their role as Chindits.

The first Gurkha Commander to suffer the wrath of his leader was Major Conron of Column 4. The men of Northern Group had crossed into the Meza Valley and were preparing to re-stock with a pre-planned supply drop. Column 4 were given the job of setting up and defending this SD area. It is not known whether they failed in this task, but by March 1st Wingate had removed Major Conron as Column 4 Commander, replacing him with his own Brigade-Major, George Bromhead.

Bernard Fergusson recalled that "As we reached the Meza Valley floor, Wingate was not in the best of tempers. He was annoyed at Column 4 for some reason." An official explanation has never been found for the decision to remove Major Conron and the incident was not mentioned in Wingate's own debrief notes.

Major Bromhead however, has recounted the story in his conversations about the operation:

"We were halfway across Burma when the 4 Column Commander lost his nerve. He could not stand the sound of a battery charging engine, so he turned these off and his radios failed. Wingate withdrew him to Brigade HQ and I took his place. We managed after a day or two to get the main radio working again and set off to follow Brigade HQ, who by now were way ahead of us."

Regretfully, Philip Conron never had the opportunity to tell his side of the story. On April 1st Wingate split his Head Quarters into several small dispersal groups and Major Conron was given a platoon of his beloved 3/2 Gurkha Rifles to lead back to India. There were many Chindit Columns present around the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers in early April and Conron's party soon met up with Major Scott and Column 8.

Scott's men had been attempting to bridge the Shweli for a couple of days, they had succeeded in getting a 'power-rope' across at one point and a section of troops had crossed under the command of Captain Williams. However, the rope had been accidentally cut by one of the men and the rest of the group were now stranded. It was while they were busily constructing rafts from bamboo and groundsheets that Major Conron arrived.

He told them that he had attempted to cross using rafts made from banana trees, but the crossing had been a complete failure due to the fast running current of the river. Scott sent a radio signal to rear base asking for RAF dinghies to be dropped for his men, he also invited Major Conron to remain with him while they waited for the supplies to arrive. Conron politely declined and he marched away with his platoon of Gurkhas, nothing more was seen or heard of the group from that moment on.

Anecdotal stories relating to the death of Philip Conron can be found within books and diaries featuring the men from Operation Longcloth. All accounts seem to revolve around his attempt to cross the Shweli River. Some say he was betrayed by a Burmese boatman who took him directly into the hands of the Japanese, another, that he was shot and killed on the eastern banks having successfully crossed over, while yet another account suggests that he simply drowned in the river. This is why Dalbahadur Pun's eye-witness testimony is so important, as it puts slightly more flesh on the bones of the incident. In any event it was a sad way for a brave and courageous man to perish, having been through so many trials and tribulations during those weeks in the Burmese jungle.

Born 21st November 1902.

First Commission 31st August 1922.

Lieutenant/Indian Army 30th November 1924.

Attained the rank of Captain 31st August 1931.

Specialist in small arms weaponry and became an Instructor in 1938.

Died close to or whilst crossing the Shweli River on 3rd April 1943.

Brigadier Wingate had not been overly impressed by the performance of his Gurkha troops in either training, or the early weeks of Operation Longcloth, perhaps with the notable exception of Mike Calvert's Column 3. The vast majority of Gurkha Columns 2 and 4 had returned to India early on after meeting the Japanese in combat, deciding on dispersal to the rear, rather than following the Brigadier's instruction to always move forward. He had also planned for Southern Group to liaise with a special scouting mission in the Kachin Hills led by Captain 'Fish' Herring. The rendezvous date of 29th March was missed, but presumably this was only due to the unexpected engagement with the Japanese at Kyaikthin rail station which had caught out Column 2 so disastrously.

I feel that the criticism aimed at 3/2 Gurkha was extremely harsh, they were after all a very young and inexperienced battalion, who had endured many 'last minute' changes to both leadership and command. I do wonder if Wingate was sub-consciously venting his obvious frustrations against the Indian General Command and their overt lack of support for his Chindit program and theories. Did he take these frustrations out on the commanders of the Gurkha Columns in 1943?

According to Mountbatten, Wingate had caused great offence in New Delhi, by describing the Indian Army as 'the largest unemployed relief organisation in the world', and made it clear that under no circumstances would he want Indian soldiers under his command. In particular he disliked the close, almost mystical, family relationship which existed between the officers and men of most Indian Army Regiments. Of course this was particularly true in the case of the Gurkhas.

The Gurkhas in turn did not like the way in which Wingate treated their officers in public. Early on in Saugor, while preparing the training regime, Wingate insisted that all officers should run from one position to the next and angrily berated those who could not keep up with him. To the Gurkha soldiers, schooled in a tradition of mutual respect, this was thoroughly disagreeable and they detested seeing their officers lose face in such a public way.

Wingate was the only British Officer in more than 130 years to criticise the performance of Gurkha soldiers, characterising them as mentally unsuited for their role as Chindits.

The first Gurkha Commander to suffer the wrath of his leader was Major Conron of Column 4. The men of Northern Group had crossed into the Meza Valley and were preparing to re-stock with a pre-planned supply drop. Column 4 were given the job of setting up and defending this SD area. It is not known whether they failed in this task, but by March 1st Wingate had removed Major Conron as Column 4 Commander, replacing him with his own Brigade-Major, George Bromhead.

Bernard Fergusson recalled that "As we reached the Meza Valley floor, Wingate was not in the best of tempers. He was annoyed at Column 4 for some reason." An official explanation has never been found for the decision to remove Major Conron and the incident was not mentioned in Wingate's own debrief notes.

Major Bromhead however, has recounted the story in his conversations about the operation:

"We were halfway across Burma when the 4 Column Commander lost his nerve. He could not stand the sound of a battery charging engine, so he turned these off and his radios failed. Wingate withdrew him to Brigade HQ and I took his place. We managed after a day or two to get the main radio working again and set off to follow Brigade HQ, who by now were way ahead of us."

Regretfully, Philip Conron never had the opportunity to tell his side of the story. On April 1st Wingate split his Head Quarters into several small dispersal groups and Major Conron was given a platoon of his beloved 3/2 Gurkha Rifles to lead back to India. There were many Chindit Columns present around the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers in early April and Conron's party soon met up with Major Scott and Column 8.

Scott's men had been attempting to bridge the Shweli for a couple of days, they had succeeded in getting a 'power-rope' across at one point and a section of troops had crossed under the command of Captain Williams. However, the rope had been accidentally cut by one of the men and the rest of the group were now stranded. It was while they were busily constructing rafts from bamboo and groundsheets that Major Conron arrived.

He told them that he had attempted to cross using rafts made from banana trees, but the crossing had been a complete failure due to the fast running current of the river. Scott sent a radio signal to rear base asking for RAF dinghies to be dropped for his men, he also invited Major Conron to remain with him while they waited for the supplies to arrive. Conron politely declined and he marched away with his platoon of Gurkhas, nothing more was seen or heard of the group from that moment on.

Anecdotal stories relating to the death of Philip Conron can be found within books and diaries featuring the men from Operation Longcloth. All accounts seem to revolve around his attempt to cross the Shweli River. Some say he was betrayed by a Burmese boatman who took him directly into the hands of the Japanese, another, that he was shot and killed on the eastern banks having successfully crossed over, while yet another account suggests that he simply drowned in the river. This is why Dalbahadur Pun's eye-witness testimony is so important, as it puts slightly more flesh on the bones of the incident. In any event it was a sad way for a brave and courageous man to perish, having been through so many trials and tribulations during those weeks in the Burmese jungle.

Update 08/12/2013.

As mentioned earlier, there are several different accounts in reference to the death of Philip Conron. The following excerpt is taken from the witness statement of Rifleman Tek Bahadur Rai of Column 3, which was given on his return to India. He had travelled with Mike Calvert after dispersal was called and by early April the group was approaching the Shweli River.

Tek Bahadur stated:

"After breaking up into our new dispersal groups I remained with Major Calvert. We went to collect some supplies that we had hidden in the jungle some weeks earlier. We then moved off toward the Shweli. Here we bumped into Major Conron who was attempting to find suitable boats to get across. He had been in the vicinity for a few days." (In fact Philip Conron had led his own group of Gurkha soldiers away from Wingate's Head Quarters Brigade when the dispersal order had been given in late March).

Tek Bahadur remembers:

"A gathering of officers from Column 3 were on the river bank, including Subedar Kumbasing Gurung, Lts. Gourlie and Gibson and Capt. McKenzie. Major Conron finally obtained seven boats for the men and he, along with some of his Gurkha Riflemen set out in the first boat. Half way across I saw the Burmese boatman purposely overturn the boat and then swim away, some of our men swam to the other side of the river, but Major Conron and Rifleman Gyalbosing Tamang were lost."

"After seeing this treachery on the part of the boatman, we decided not to rely upon them anymore and quickly moved away into the nearby jungle where we wandered for about two weeks."

From the large group present that day on the banks of the Shweli many failed to return to India at all, while others had to endure two years as prisoners in Japanese hands. Tek Bahadur was slightly more fortunate, although he was captured later on in April, he managed to escape his captors in the spring of 1944, as the second Chindit expedition was over-running the area where he was held.

My thanks must go to the Gurkha Museum at Winchester for their help and co-operation in regards to this update.

As mentioned earlier, there are several different accounts in reference to the death of Philip Conron. The following excerpt is taken from the witness statement of Rifleman Tek Bahadur Rai of Column 3, which was given on his return to India. He had travelled with Mike Calvert after dispersal was called and by early April the group was approaching the Shweli River.

Tek Bahadur stated:

"After breaking up into our new dispersal groups I remained with Major Calvert. We went to collect some supplies that we had hidden in the jungle some weeks earlier. We then moved off toward the Shweli. Here we bumped into Major Conron who was attempting to find suitable boats to get across. He had been in the vicinity for a few days." (In fact Philip Conron had led his own group of Gurkha soldiers away from Wingate's Head Quarters Brigade when the dispersal order had been given in late March).

Tek Bahadur remembers:

"A gathering of officers from Column 3 were on the river bank, including Subedar Kumbasing Gurung, Lts. Gourlie and Gibson and Capt. McKenzie. Major Conron finally obtained seven boats for the men and he, along with some of his Gurkha Riflemen set out in the first boat. Half way across I saw the Burmese boatman purposely overturn the boat and then swim away, some of our men swam to the other side of the river, but Major Conron and Rifleman Gyalbosing Tamang were lost."

"After seeing this treachery on the part of the boatman, we decided not to rely upon them anymore and quickly moved away into the nearby jungle where we wandered for about two weeks."

From the large group present that day on the banks of the Shweli many failed to return to India at all, while others had to endure two years as prisoners in Japanese hands. Tek Bahadur was slightly more fortunate, although he was captured later on in April, he managed to escape his captors in the spring of 1944, as the second Chindit expedition was over-running the area where he was held.

My thanks must go to the Gurkha Museum at Winchester for their help and co-operation in regards to this update.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and JP Cross 2013.