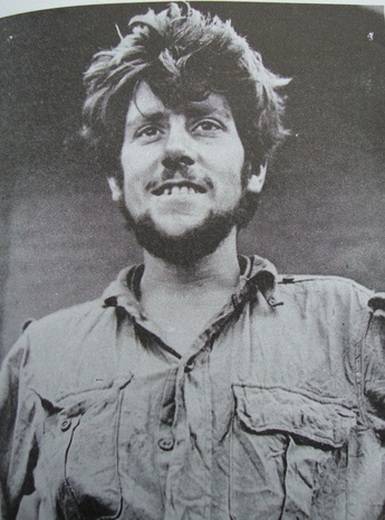

RAF Sergeant Douglas Mills

Here is an extract from the Missing in Action reports circa 19/09/1943, held at the time at the Army HQ, Bombay, India.

The following received from Army authorities (witnesses statements).

RE: 591733 Corporal/Acting Sergeant Mills D.L.L. Attached Brigade HQ which split into dispersal groups on 30th March 1943, east banks of Irrawaddy River. This Airman accompanied one of these groups, no further news.

This was all the information known about Sergeant Doug Mills shortly after the witness statements and first hand accounts of lost personnel had been collated at Indian Army HQ in the autumn of 1943. He had been a member of the Air liaison section of Wingate’s own HQ Brigade on the operation and had dispersed from the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River in late March that year.

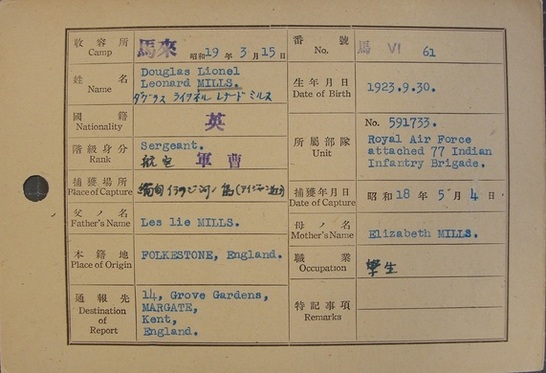

Born in September 1923 and from the Folkestone area of Kent, he had been in India since 1941 performing various RAF duties. From his Japanese index card (front face seen above) found at the National Archives, it is known that he was eventually captured on the 4th May and so had been attempting to reach India for roughly 34 days since the first dispersal at the Irrawaddy.

He would of, like all the Chindits captured that year, found himself in Block 6 of the infamous and daunting Rangoon Jail. Seeing Doug’s age from his card makes me wonder if he may have been one of the youngest British POW’s in the jail at the time, being just 19 years and 8 months old. Once again from his index card it is known that he was one of the so called ‘fit’ men, marched out of the jail by the Japanese guards in late April 1945 and subsequently released close to the town of Pegu. The Japanese had finally realised that their time in control of Burma was up and they headed away toward the Siam borders.

Enough question and speculation. Here is Doug’s own memoir from those days, which he wrote down in the early 1990’s. Seen here courtesy of Matt Poole, who corresponded with Doug based around their shared interest of the Air War in Burma. Matt states that Doug was “a wonderful bloke, with a healthy sense of humour when recalling those WW2 days”.

The following received from Army authorities (witnesses statements).

RE: 591733 Corporal/Acting Sergeant Mills D.L.L. Attached Brigade HQ which split into dispersal groups on 30th March 1943, east banks of Irrawaddy River. This Airman accompanied one of these groups, no further news.

This was all the information known about Sergeant Doug Mills shortly after the witness statements and first hand accounts of lost personnel had been collated at Indian Army HQ in the autumn of 1943. He had been a member of the Air liaison section of Wingate’s own HQ Brigade on the operation and had dispersed from the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River in late March that year.

Born in September 1923 and from the Folkestone area of Kent, he had been in India since 1941 performing various RAF duties. From his Japanese index card (front face seen above) found at the National Archives, it is known that he was eventually captured on the 4th May and so had been attempting to reach India for roughly 34 days since the first dispersal at the Irrawaddy.

He would of, like all the Chindits captured that year, found himself in Block 6 of the infamous and daunting Rangoon Jail. Seeing Doug’s age from his card makes me wonder if he may have been one of the youngest British POW’s in the jail at the time, being just 19 years and 8 months old. Once again from his index card it is known that he was one of the so called ‘fit’ men, marched out of the jail by the Japanese guards in late April 1945 and subsequently released close to the town of Pegu. The Japanese had finally realised that their time in control of Burma was up and they headed away toward the Siam borders.

Enough question and speculation. Here is Doug’s own memoir from those days, which he wrote down in the early 1990’s. Seen here courtesy of Matt Poole, who corresponded with Doug based around their shared interest of the Air War in Burma. Matt states that Doug was “a wonderful bloke, with a healthy sense of humour when recalling those WW2 days”.

A Royal Air Force Chindit

By Doug Mills

I should start by giving a bit of background as to how I, a member of the Royal Air Force, came to be in the ranks of the Chindits. I had been in the R.A.F. since early 1939, and by the middle of 1942 I was a sergeant involved with Coastal Defence from out of Karachi. (I don't know how many people can remember our bi-planes, Wapiti's (seen pictured right) with Lewis gun firing through the prop, more like 1919 than 1941). Anyway at this time I was recuperating in Bombay from an accident and had nothing official to do except report daily to the Base Personnel Office in Sir Phirosha Meta Road, just in case I was required. One morning I saw in Routine Orders an item calling for volunteers for a special mission. This did surprise me somewhat as I had always been given to understand that, unlike Hollywood, the forces rarely called for volunteers, they just detailed you to any job or duty they thought fit! Anyway, something (curiosity I think) impelled me to follow it up and see the C.O., who asked a number of questions, but oddly enough did not query my sanity, eventually telling me that I would be sent to Delhi for interview.

Having arrived in Delhi, which after Bombay I found to be quite cold at night, I was taken by a Flying Officer somebody or other to be interviewed by Air Vice Marshal Williams and Air Commodore Darvell. I was ushered into their presence and actually asked to sit down, presumably to make it easier for me to withstand any shocks. I was questioned at length but was not given a great deal of detail as to what I was to do, just that I would find out when I arrived, if I went. I was also told that I would have no better than a fifty fifty chance of getting back in one piece, plus a casual aside that as far as was known the Japs were not keen on taking prisoners! The A.V.M. finished up by telling me that nothing less would be thought of me if, as it were, I declined to take up the contract, and walked out. I was so scared of showing that I was scared that I indicated my willingness to go, at which he grabbed a scrap of paper, wrote a few words and passed me back to his aide. On the paper were the words "Send him to Saugor."

Well off I went to Saugor by train, where from memory the station consisted of a couple of wooden planks on piles on either side of the line, all in the middle of absolutely nowhere. I was met by an M.P. Sergeant with a small truck who told me that my destination was '42nd milestone'. Thus enlightened, I settled back to the most bumpy vehicle ride that I can ever remember. The training camp was at the said milestone, where I was handed over to an army major who took me to be given the once-over by a most impressive person, the then-Brigadier Wingate. At the time I was nearly nineteen, just over six feet tall and weighed thirteen and a half stone.

From here on, remember I was an Airman who had to prove myself. I settled down to a rigorous program of intensive training, living rough, heavy pack marching, lots of running, learning to construct a bed from odd bits of wood. No problem really, I'd been a Wolf Cub. I was also taught to ride a horse, to which I would like to give a bit of a mention.

This horse riding business was really quite entertaining, particularly to the instructor, a Captain Carey-Foster. I learned that the first thing to master was to be able to clamber on the horse, stay put in the saddle and face the same direction as the horse’s head was pointing, which, after a little difficulty, I managed to achieve. There would have been close to a dozen of us under instruction, formed into a circle with the instructor in the middle. Well, we were first told how to make the horse walk, after which came the trot, which is the bit I found uncomfortable. The best part came whilst we were in a circle, trotting around and around and the instructor bawled out, "You might at least have the decency to smile and look as if you are enjoying it!" However, I did make progress and it wasn't long before I was one of the fittest men in all of India.

After a few months and having shifted to Jhansi, we entrained and finished up some days later at the Manipur railhead, where we made camp for a few days before moving over very hairy roads through the mountains to Imphal. This was to be our last stop before moving into Burma, and I can remember being paraded and told that anyone who didn't want to continue on this sightseeing tour should speak up now. I was once again too scared to take up the offer.

It was now about February 1943 when we upped sticks and marched to the Chindwin River, which, after being crossed, put us into enemy territory. I was with Brigade Head Quarters Column, which of course included Wingate. We were now in Burma.

Many much better scribes than me have written of the Chindit expeditions, so I will keep to my own personal tales and won't attempt to describe the campaigns. My duties included cypher and radio work, calling in supplies at dropping zones. We were able to receive mail but of course couldn't send any out. It was dropped by parachute with the other supplies. On one occasion I recollect it included a new monocle for the then-Major Bernard Ferguson. I got the odd letter from my dear parents which usually contained a postal order. Cash-wise this was utterly useless as we were quite unable to locate a post-office in the middle of the jungle! Of course there was nowhere to spend any cash. However, I never tore up the orders or threw them out, although not as soft as Kleenex they did a turn.

We have all at some time or another heard jokes about the words "military intelligence" being a contradiction in terms. I often feel that this could have arisen from one of the Intelligence Officers in our group. He had found an unexploded Jap mortar bomb, which he stashed in a yakdan, presumably for future inspection. A yakdan, by the way, is the name given to a sort of overgrown suitcase, one of which is slung over each side of a mule in order to let the mule know that he wasn't just going for a stroll. As we made our way along a dry chaung, not the kind that the M.L.s fought in over in the Arakan, the mule with the mortar must have somehow stumbled and up went the bomb, causing a great deal of consternation and a few other things I couldn't possibly now get my tongue around. When the smoke cleared we were minus one mule and two yakdans. Fortunately, to my knowledge, no further such bombs were located by anyone.

The time came when we had to make an attempt to get back to India. One could write a whole book on the varied happenings in such an Exercise, but I will restrict myself to the final independent part of the expedition as far as it affected me. I finished up on an island in the middle of the Irrawaddy, thinking I had reached the west bank of that river and not realising I was wrong until, when moving off in a westerly direction, I was confronted by more water. Well, it didn't take long for the Nips to discover that the island was occupied by the unwanted; that is where and how I came to be captured. Having been flung to the ground and securely tied up, a guard, possibly as he was a really big fellow he could have been a Korean, decided to have a bit of fun by lunging at me with his fixed bayonet, all the while screaming, "you want this?" Naturally I considered it prudent to keep my trap shut under these extreme circumstances and he eventually tired of the game, which is just as well, or I wouldn't now be telling this story.

Leaving Doug's account for a moment here is how Brigadier Wingate remembers the same moment in time, paraphrased from his own personal dispersal diary, dated 09/04/43:

“In the early afternoon we descended on MAUNGGON and eventually with local help found two boats in a backwater. Later we stopped a third boat, which was moving upstream. We began crossing about 1530 hrs but when half the party was over automatic fire was heard from the NORTH and our native boatmen made off with the boats leaving half our party on the EAST bank".

"We had apparently been landed on an island in the middle of the river and we immediately pushed on towards NYAUNGBINTHA where we got a large boat and crossed at dusk.

We lay up for the night about 2 miles N.E. of NYAUNGBINTHA. The mosquitoes were intolerable and we got little sleep".

Below is a rather special photograph which I believe was taken by Wingate's replacement Brigade Major, 'Gim' Anderson. I have a feeling that this photo was taken just before the group broke up into their respective dispersal parties and headed back to India, possibly sometime in the first week of April. From left to right we have:

Back Row: An RAF Sergeant?. Squadron Leader Cecil Longmore. Motilal Katju. Wingate. Ken Spurlock.

Front Row: Albert Tooth. Lieut.Lewis Rose. Major J. Jefferies (foreground with rifle). Alan Fidler.

All of these men attempted the return to India as part of Wingate's own dispersal party, some made it back, others were captured and spent two years in Rangoon Jail. The Indian Army officer Motilal Katju was sadly killed by the Japanese in a village close to the Chindwin River. He took part in operation Longcloth as an official observer and had kept a detailed diary of the expedition, which was lost forever when he was killed.

By Doug Mills

I should start by giving a bit of background as to how I, a member of the Royal Air Force, came to be in the ranks of the Chindits. I had been in the R.A.F. since early 1939, and by the middle of 1942 I was a sergeant involved with Coastal Defence from out of Karachi. (I don't know how many people can remember our bi-planes, Wapiti's (seen pictured right) with Lewis gun firing through the prop, more like 1919 than 1941). Anyway at this time I was recuperating in Bombay from an accident and had nothing official to do except report daily to the Base Personnel Office in Sir Phirosha Meta Road, just in case I was required. One morning I saw in Routine Orders an item calling for volunteers for a special mission. This did surprise me somewhat as I had always been given to understand that, unlike Hollywood, the forces rarely called for volunteers, they just detailed you to any job or duty they thought fit! Anyway, something (curiosity I think) impelled me to follow it up and see the C.O., who asked a number of questions, but oddly enough did not query my sanity, eventually telling me that I would be sent to Delhi for interview.

Having arrived in Delhi, which after Bombay I found to be quite cold at night, I was taken by a Flying Officer somebody or other to be interviewed by Air Vice Marshal Williams and Air Commodore Darvell. I was ushered into their presence and actually asked to sit down, presumably to make it easier for me to withstand any shocks. I was questioned at length but was not given a great deal of detail as to what I was to do, just that I would find out when I arrived, if I went. I was also told that I would have no better than a fifty fifty chance of getting back in one piece, plus a casual aside that as far as was known the Japs were not keen on taking prisoners! The A.V.M. finished up by telling me that nothing less would be thought of me if, as it were, I declined to take up the contract, and walked out. I was so scared of showing that I was scared that I indicated my willingness to go, at which he grabbed a scrap of paper, wrote a few words and passed me back to his aide. On the paper were the words "Send him to Saugor."

Well off I went to Saugor by train, where from memory the station consisted of a couple of wooden planks on piles on either side of the line, all in the middle of absolutely nowhere. I was met by an M.P. Sergeant with a small truck who told me that my destination was '42nd milestone'. Thus enlightened, I settled back to the most bumpy vehicle ride that I can ever remember. The training camp was at the said milestone, where I was handed over to an army major who took me to be given the once-over by a most impressive person, the then-Brigadier Wingate. At the time I was nearly nineteen, just over six feet tall and weighed thirteen and a half stone.

From here on, remember I was an Airman who had to prove myself. I settled down to a rigorous program of intensive training, living rough, heavy pack marching, lots of running, learning to construct a bed from odd bits of wood. No problem really, I'd been a Wolf Cub. I was also taught to ride a horse, to which I would like to give a bit of a mention.

This horse riding business was really quite entertaining, particularly to the instructor, a Captain Carey-Foster. I learned that the first thing to master was to be able to clamber on the horse, stay put in the saddle and face the same direction as the horse’s head was pointing, which, after a little difficulty, I managed to achieve. There would have been close to a dozen of us under instruction, formed into a circle with the instructor in the middle. Well, we were first told how to make the horse walk, after which came the trot, which is the bit I found uncomfortable. The best part came whilst we were in a circle, trotting around and around and the instructor bawled out, "You might at least have the decency to smile and look as if you are enjoying it!" However, I did make progress and it wasn't long before I was one of the fittest men in all of India.

After a few months and having shifted to Jhansi, we entrained and finished up some days later at the Manipur railhead, where we made camp for a few days before moving over very hairy roads through the mountains to Imphal. This was to be our last stop before moving into Burma, and I can remember being paraded and told that anyone who didn't want to continue on this sightseeing tour should speak up now. I was once again too scared to take up the offer.

It was now about February 1943 when we upped sticks and marched to the Chindwin River, which, after being crossed, put us into enemy territory. I was with Brigade Head Quarters Column, which of course included Wingate. We were now in Burma.

Many much better scribes than me have written of the Chindit expeditions, so I will keep to my own personal tales and won't attempt to describe the campaigns. My duties included cypher and radio work, calling in supplies at dropping zones. We were able to receive mail but of course couldn't send any out. It was dropped by parachute with the other supplies. On one occasion I recollect it included a new monocle for the then-Major Bernard Ferguson. I got the odd letter from my dear parents which usually contained a postal order. Cash-wise this was utterly useless as we were quite unable to locate a post-office in the middle of the jungle! Of course there was nowhere to spend any cash. However, I never tore up the orders or threw them out, although not as soft as Kleenex they did a turn.

We have all at some time or another heard jokes about the words "military intelligence" being a contradiction in terms. I often feel that this could have arisen from one of the Intelligence Officers in our group. He had found an unexploded Jap mortar bomb, which he stashed in a yakdan, presumably for future inspection. A yakdan, by the way, is the name given to a sort of overgrown suitcase, one of which is slung over each side of a mule in order to let the mule know that he wasn't just going for a stroll. As we made our way along a dry chaung, not the kind that the M.L.s fought in over in the Arakan, the mule with the mortar must have somehow stumbled and up went the bomb, causing a great deal of consternation and a few other things I couldn't possibly now get my tongue around. When the smoke cleared we were minus one mule and two yakdans. Fortunately, to my knowledge, no further such bombs were located by anyone.

The time came when we had to make an attempt to get back to India. One could write a whole book on the varied happenings in such an Exercise, but I will restrict myself to the final independent part of the expedition as far as it affected me. I finished up on an island in the middle of the Irrawaddy, thinking I had reached the west bank of that river and not realising I was wrong until, when moving off in a westerly direction, I was confronted by more water. Well, it didn't take long for the Nips to discover that the island was occupied by the unwanted; that is where and how I came to be captured. Having been flung to the ground and securely tied up, a guard, possibly as he was a really big fellow he could have been a Korean, decided to have a bit of fun by lunging at me with his fixed bayonet, all the while screaming, "you want this?" Naturally I considered it prudent to keep my trap shut under these extreme circumstances and he eventually tired of the game, which is just as well, or I wouldn't now be telling this story.

Leaving Doug's account for a moment here is how Brigadier Wingate remembers the same moment in time, paraphrased from his own personal dispersal diary, dated 09/04/43:

“In the early afternoon we descended on MAUNGGON and eventually with local help found two boats in a backwater. Later we stopped a third boat, which was moving upstream. We began crossing about 1530 hrs but when half the party was over automatic fire was heard from the NORTH and our native boatmen made off with the boats leaving half our party on the EAST bank".

"We had apparently been landed on an island in the middle of the river and we immediately pushed on towards NYAUNGBINTHA where we got a large boat and crossed at dusk.

We lay up for the night about 2 miles N.E. of NYAUNGBINTHA. The mosquitoes were intolerable and we got little sleep".

Below is a rather special photograph which I believe was taken by Wingate's replacement Brigade Major, 'Gim' Anderson. I have a feeling that this photo was taken just before the group broke up into their respective dispersal parties and headed back to India, possibly sometime in the first week of April. From left to right we have:

Back Row: An RAF Sergeant?. Squadron Leader Cecil Longmore. Motilal Katju. Wingate. Ken Spurlock.

Front Row: Albert Tooth. Lieut.Lewis Rose. Major J. Jefferies (foreground with rifle). Alan Fidler.

All of these men attempted the return to India as part of Wingate's own dispersal party, some made it back, others were captured and spent two years in Rangoon Jail. The Indian Army officer Motilal Katju was sadly killed by the Japanese in a village close to the Chindwin River. He took part in operation Longcloth as an official observer and had kept a detailed diary of the expedition, which was lost forever when he was killed.

Now let's return to the Mills memoir:

Next day I was taken to a village on the west bank of the river and incarcerated in a large room in a house along with about a dozen other chaps who had been nabbed. While we were here we were comparatively well fed and the Jap commander, who spoke pretty good English, came and gave us the once over. As far as Japs are concerned he was the nearest thing to a human being I ever came across. He advised that as we would be moved in stages to Rangoon our treatment wouldn't be so good. He was dead right.

We were shifted by truck, first to a place called Wuntho, then on to Maymyo, where there were many more prisoners. We were kept in a small room, only large enough for us to squat on our haunches. We nearly choked to death at night through clouds of stinking smoke from a mixture of wood and leaves, which were used to keep down the mossies. Eventually we moved on to Rangoon by rail. It wasn't the Orient Express; in fact the cattle trucks had no creature comforts of any kind.

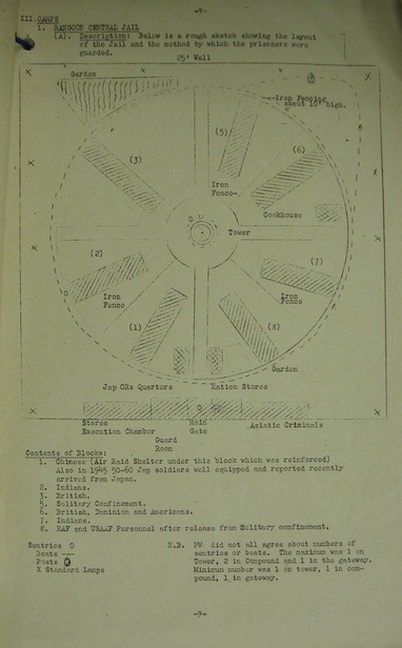

At Rangoon we were taken to the Central Jail, (see sketch map pictured right, showing the aerial view of the jail and the block numbers) which was to be my home for the next couple of years. I finished up in No. 6 compound, which was predominantly occupied by Britishers plus quite a few Americans and others from around the Commonwealth. Orders were given in Japanese, the basics of which we soon learned on pain of being belted up if we didn't.

You will no doubt be fully aware that the vast majority of members of the armed forces are born linguists. In fact in a very short time they acquire a good knowledge of an alternative form of the English language which would undoubtedly be frowned upon if used in the drawing room at home, probably to the degree where one would immediately be thrown out on one's ear and cut off without a cent. I have to admit that I was no exception. This alternative language usually consisted of sentences interspersed with words of no more than four letters. Anyway, I would like to tell you of an incident which occurred at this time, hopefully without causing offence.

As time passed it became obvious to us, due mainly to the almost daily bombing raids, that we were indeed on the winning side. We were able to dig some primitive slit trenches in order to obtain a bit of protection. It so happened that at about this time I had volunteered to become the Char Wallah. We had two or three vats, about three feet in diameter, in which the food, such as it was, was cooked. The vats sat on bricks and fires were lit underneath to do the necessary. My slit trench was close to the cookhouse and whilst a number of us were huddled in it a bomb dropped pretty close, shaking the ground as if there was an earthquake. I, on hearing a clanging noise from the direction of the said cookhouse, yelled "There goes my f———g tea urn", which caused the rest of the blokes to forget the fact that we were in the middle of a raid and laugh their heads off; at least it eased the tension.

As time passed there was a change in camp commander, the new one being less inhumane than his predecessor. Somewhere along the line, I really don't know how it came about, he gave permission for the prisoners putting on a concert party. At one end of the compound was a very large hut in which the show was held. We had no music or instruments but a group of the boys were able to make a decent sound by humming and blowing into their hands. Where I came into all of this was that I was drafted into the part of Carmen Miranda. Anyway, to cut a long story sideways, the lads were packed into the hut along with some Jap officers. The various artists did their bit and then my turn came to face the audience, including the Nips. I gave a somewhat distorted rendition of "I, I, I, I like you very much,....", which amused everyone except me. Regardless to the words of my song, I still do not like the Japs at all, never mind "very much".

Well, enough is enough. I must point out that there was a much more dark and sinister aspect, which I have studiously avoided recording, in the overall story of our imprisonment in Rangoon Jail, described by Picture Post as a notorious living hell. In conclusion, I would like to pay tribute to those who never made it back to freedom and their loved ones. I salute them and may God bless them and keep them. Lest We forget.

It may be useful to look more closely at the story of Wingate’s dispersal party and their progress to the Chindwin. There can be no doubt that many of the men who finally made it back to India from that group, look upon Wingate’s actions during the journey with angry eyes.

Some feel that he chose the best and most useful soldiers for his own party. People like Captain Aung Thin, the Burmese Rifleman and expert on the local area, or the fact that he took many of 142 Commando into his group for best protection. Some might say that this was a selfish act, while others would say it made total sense to ensure that the chief got home in one piece.

I have heard comments that Wingate chose to stay in the jungle on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy for over a week after the failure of the initial attempt to cross, so that he and his men could rest and build up their strength for the arduous journey that lay ahead. While others suggest this was a callous act in allowing the other groups to head off first to test the Japanese strength and presence in the area.

To be honest it is difficult to judge, but there certainly were more detractors than supporters when everyone met up again in India.

Here is Signaller Eric Hutchins viewpoint, as paraphrased from the book ‘March or Die’:

Firstly, describing the escape over the Irrawaddy: “The first six boats (including Wingate) made it over. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the other bank, we found no trace of the others. Wingate’s excuse, he thought we had all been captured”.

"So we set out west, only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Now our problems really began”.

Hutchins continues: "Wingate was my hero before the campaign, but after his deliberate abandonment on the east bank of the Irrawaddy, I know he considered his own safety and not others. He would deliberately abandon anyone he considered to be a handicap. This he proved when he left Ken Spurlock (Signals officer HQ Brigade) in a village close to the safety of the Chindwin”. Spurlock was suffering from dysentery and could not continue, he later survived his time in Rangoon Jail and was liberated in May 1945.

Hutchins concludes: “I was weak with dysentery, but my companions never abandoned me”.

So feelings ran high over Wingate’s attitude to his own survival, but the men were told from the outset that if they found themselves unable to continue their journey on operation Longcloth, then they would almost certainly be left behind and face whatever fate had in store for them that year. Below are two photographs of Signalman Eric Hutchins, one before the operation, probably taken in an Indian photographic studio, the other after he had successfully returned to Assam in April 1943. Thanks goes to Phil Chinnery for use of the photos and quotes from his book, 'March or Die'.

Next day I was taken to a village on the west bank of the river and incarcerated in a large room in a house along with about a dozen other chaps who had been nabbed. While we were here we were comparatively well fed and the Jap commander, who spoke pretty good English, came and gave us the once over. As far as Japs are concerned he was the nearest thing to a human being I ever came across. He advised that as we would be moved in stages to Rangoon our treatment wouldn't be so good. He was dead right.

We were shifted by truck, first to a place called Wuntho, then on to Maymyo, where there were many more prisoners. We were kept in a small room, only large enough for us to squat on our haunches. We nearly choked to death at night through clouds of stinking smoke from a mixture of wood and leaves, which were used to keep down the mossies. Eventually we moved on to Rangoon by rail. It wasn't the Orient Express; in fact the cattle trucks had no creature comforts of any kind.

At Rangoon we were taken to the Central Jail, (see sketch map pictured right, showing the aerial view of the jail and the block numbers) which was to be my home for the next couple of years. I finished up in No. 6 compound, which was predominantly occupied by Britishers plus quite a few Americans and others from around the Commonwealth. Orders were given in Japanese, the basics of which we soon learned on pain of being belted up if we didn't.

You will no doubt be fully aware that the vast majority of members of the armed forces are born linguists. In fact in a very short time they acquire a good knowledge of an alternative form of the English language which would undoubtedly be frowned upon if used in the drawing room at home, probably to the degree where one would immediately be thrown out on one's ear and cut off without a cent. I have to admit that I was no exception. This alternative language usually consisted of sentences interspersed with words of no more than four letters. Anyway, I would like to tell you of an incident which occurred at this time, hopefully without causing offence.

As time passed it became obvious to us, due mainly to the almost daily bombing raids, that we were indeed on the winning side. We were able to dig some primitive slit trenches in order to obtain a bit of protection. It so happened that at about this time I had volunteered to become the Char Wallah. We had two or three vats, about three feet in diameter, in which the food, such as it was, was cooked. The vats sat on bricks and fires were lit underneath to do the necessary. My slit trench was close to the cookhouse and whilst a number of us were huddled in it a bomb dropped pretty close, shaking the ground as if there was an earthquake. I, on hearing a clanging noise from the direction of the said cookhouse, yelled "There goes my f———g tea urn", which caused the rest of the blokes to forget the fact that we were in the middle of a raid and laugh their heads off; at least it eased the tension.

As time passed there was a change in camp commander, the new one being less inhumane than his predecessor. Somewhere along the line, I really don't know how it came about, he gave permission for the prisoners putting on a concert party. At one end of the compound was a very large hut in which the show was held. We had no music or instruments but a group of the boys were able to make a decent sound by humming and blowing into their hands. Where I came into all of this was that I was drafted into the part of Carmen Miranda. Anyway, to cut a long story sideways, the lads were packed into the hut along with some Jap officers. The various artists did their bit and then my turn came to face the audience, including the Nips. I gave a somewhat distorted rendition of "I, I, I, I like you very much,....", which amused everyone except me. Regardless to the words of my song, I still do not like the Japs at all, never mind "very much".

Well, enough is enough. I must point out that there was a much more dark and sinister aspect, which I have studiously avoided recording, in the overall story of our imprisonment in Rangoon Jail, described by Picture Post as a notorious living hell. In conclusion, I would like to pay tribute to those who never made it back to freedom and their loved ones. I salute them and may God bless them and keep them. Lest We forget.

It may be useful to look more closely at the story of Wingate’s dispersal party and their progress to the Chindwin. There can be no doubt that many of the men who finally made it back to India from that group, look upon Wingate’s actions during the journey with angry eyes.

Some feel that he chose the best and most useful soldiers for his own party. People like Captain Aung Thin, the Burmese Rifleman and expert on the local area, or the fact that he took many of 142 Commando into his group for best protection. Some might say that this was a selfish act, while others would say it made total sense to ensure that the chief got home in one piece.

I have heard comments that Wingate chose to stay in the jungle on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy for over a week after the failure of the initial attempt to cross, so that he and his men could rest and build up their strength for the arduous journey that lay ahead. While others suggest this was a callous act in allowing the other groups to head off first to test the Japanese strength and presence in the area.

To be honest it is difficult to judge, but there certainly were more detractors than supporters when everyone met up again in India.

Here is Signaller Eric Hutchins viewpoint, as paraphrased from the book ‘March or Die’:

Firstly, describing the escape over the Irrawaddy: “The first six boats (including Wingate) made it over. Eventually the boat returned for us, but when we reached the other bank, we found no trace of the others. Wingate’s excuse, he thought we had all been captured”.

"So we set out west, only to find we were on an island in the middle of the river. Now our problems really began”.

Hutchins continues: "Wingate was my hero before the campaign, but after his deliberate abandonment on the east bank of the Irrawaddy, I know he considered his own safety and not others. He would deliberately abandon anyone he considered to be a handicap. This he proved when he left Ken Spurlock (Signals officer HQ Brigade) in a village close to the safety of the Chindwin”. Spurlock was suffering from dysentery and could not continue, he later survived his time in Rangoon Jail and was liberated in May 1945.

Hutchins concludes: “I was weak with dysentery, but my companions never abandoned me”.

So feelings ran high over Wingate’s attitude to his own survival, but the men were told from the outset that if they found themselves unable to continue their journey on operation Longcloth, then they would almost certainly be left behind and face whatever fate had in store for them that year. Below are two photographs of Signalman Eric Hutchins, one before the operation, probably taken in an Indian photographic studio, the other after he had successfully returned to Assam in April 1943. Thanks goes to Phil Chinnery for use of the photos and quotes from his book, 'March or Die'.

Update 31/03/2017.

From the archive of the Thanet Advertiser and Echo newspaper, transcribed below are two short articles announcing the safe return to England of Sergeant Douglas Mills. Firstly, from an issue dated Friday 25th May 1945:

Posted Missing, Now Safe

Posted as missing over two years ago, Sgt. Douglas L.L. Mills, RAF, who failed to return from the Wingate Expedition in Burma (1943), is now known to be safe in Allied hands. Sgt. Mills is the eldest son of Mrs. Fitzmaurice, of 14 Grove Gardens, Margate, who has received a cable from him saying he will be home soon. By a coincidence, on the same day as the cable arrived, Mr. and Mrs. Fitzmaurice heard that their daughter, Mrs. R. Petersen, who has been in Denmark throughout the war, is safe and well.

From the same newspaper, published on Friday 31st August 1945:

Back From a Jap Camp

Sgt. Douglas L. L. Mills, RAF, has returned to England after two years as a prisoner of the Japanese. Captured on a small island in the Irrawaddy River, Sgt. Mills was taken to Tigyaing, twenty five miles south of Katha in upper Burma. Following interrogation he was sent to a prison camp at Maymyo which he says, was a sort of punishment camp, the purpose of which seemed to be to break the spirits of the prisoners. "Our treatment there was pretty grim," says Sgt. Mills.

Transferred to a permanent camp at Rangoon, he and his colleagues watched British bombers fly over. The Japs put the prisoners to work on bomb disposal operations after air raids. Their food was almost entirely rice, with an occasional small piece of meat. In order to augment rations, the men cultivated and cooked a weed that tasted much like spinach. With only a sack each to lie on, the prisoners slept on a stone floor. As the Allied troops advanced, the Japs tried to march the POW's to Moulmein, but only got as far as Pegu. Here the Japs left and the prisoners contacted British troops on the 3rd May this year. Weakened by the forced march, Sgt. Mills was in several hospitals before reaching Bombay (for repatriation).

From the archive of the Thanet Advertiser and Echo newspaper, transcribed below are two short articles announcing the safe return to England of Sergeant Douglas Mills. Firstly, from an issue dated Friday 25th May 1945:

Posted Missing, Now Safe

Posted as missing over two years ago, Sgt. Douglas L.L. Mills, RAF, who failed to return from the Wingate Expedition in Burma (1943), is now known to be safe in Allied hands. Sgt. Mills is the eldest son of Mrs. Fitzmaurice, of 14 Grove Gardens, Margate, who has received a cable from him saying he will be home soon. By a coincidence, on the same day as the cable arrived, Mr. and Mrs. Fitzmaurice heard that their daughter, Mrs. R. Petersen, who has been in Denmark throughout the war, is safe and well.

From the same newspaper, published on Friday 31st August 1945:

Back From a Jap Camp

Sgt. Douglas L. L. Mills, RAF, has returned to England after two years as a prisoner of the Japanese. Captured on a small island in the Irrawaddy River, Sgt. Mills was taken to Tigyaing, twenty five miles south of Katha in upper Burma. Following interrogation he was sent to a prison camp at Maymyo which he says, was a sort of punishment camp, the purpose of which seemed to be to break the spirits of the prisoners. "Our treatment there was pretty grim," says Sgt. Mills.

Transferred to a permanent camp at Rangoon, he and his colleagues watched British bombers fly over. The Japs put the prisoners to work on bomb disposal operations after air raids. Their food was almost entirely rice, with an occasional small piece of meat. In order to augment rations, the men cultivated and cooked a weed that tasted much like spinach. With only a sack each to lie on, the prisoners slept on a stone floor. As the Allied troops advanced, the Japs tried to march the POW's to Moulmein, but only got as far as Pegu. Here the Japs left and the prisoners contacted British troops on the 3rd May this year. Weakened by the forced march, Sgt. Mills was in several hospitals before reaching Bombay (for repatriation).

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2011.