Elephant Bill Williams

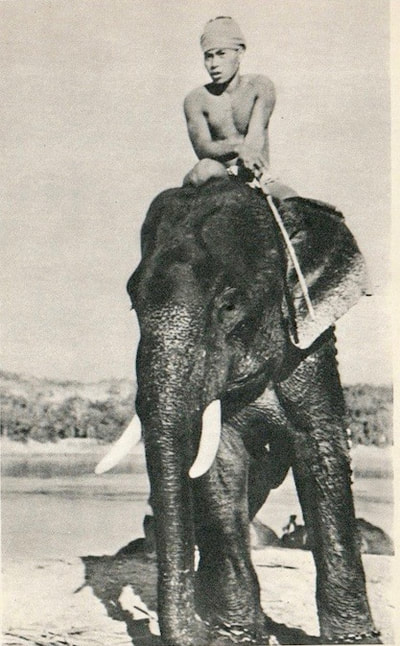

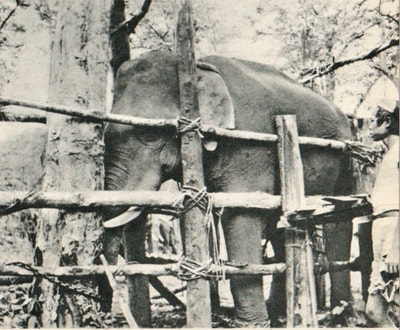

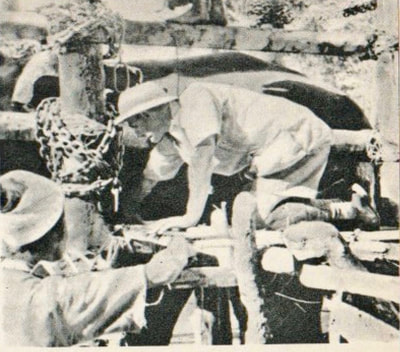

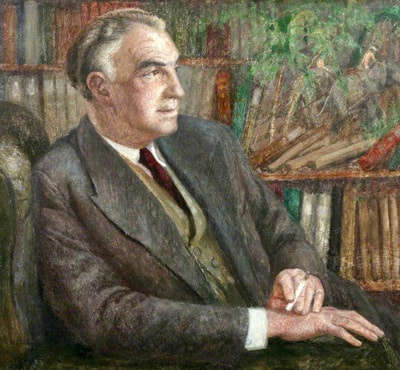

Bill Williams at work.

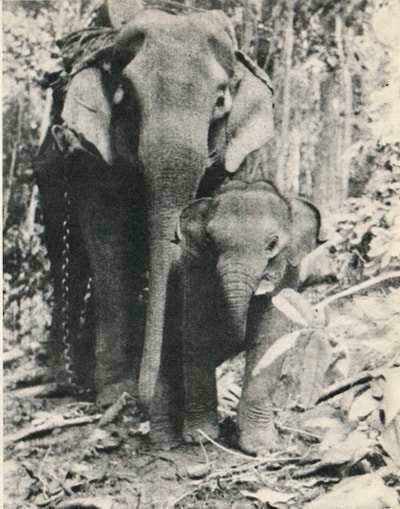

Bill Williams at work.

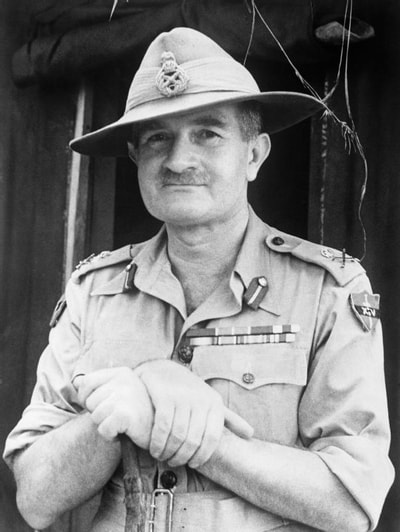

During the course of my research into the first Chindit expedition I have read many books. As a way of broadening my knowledge of the Burma campaign, I chose to investigate the 1950's classic, Elephant Bill. This book was written by James Howard Williams, an elephant expert working for the Bombay-Burmah Trading Corporation at the time of World War 2. Through his long-standing work with elephants, Williams became involved with the 14th Army during the Burma Campaign, reaching the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, being mentioned in dispatches no fewer than three times and eventually being awarded an OBE in 1945.

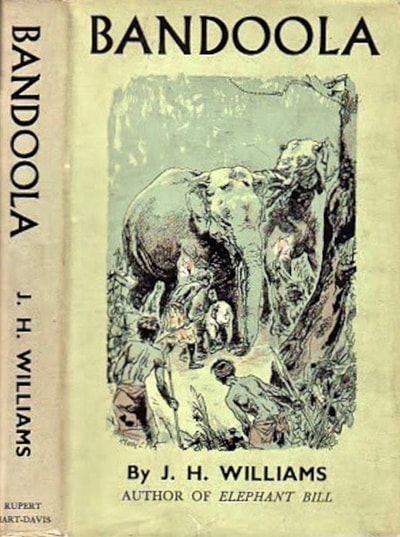

The book Elephant Bill became much more relevant to my research on the second read, when I discovered that Williams had rather reluctantly loaned some of his animals for work on Operation Longcloth. Indeed Williams' second book about his time with elephants, called Bandoola, refers to one of the animals he lent to Wingate in 1943. These animals were only supposed to assist in the movement of heavy supplies up until the Chindwin River. Sadly, they were eventually used to ferry the cargo across the river and one elephant was lost.

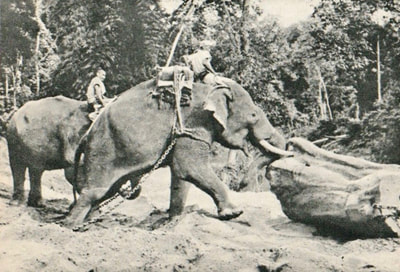

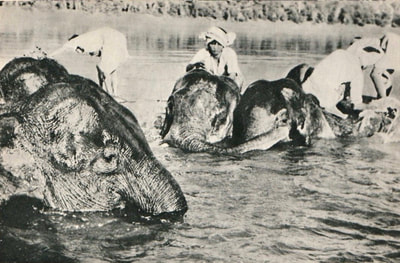

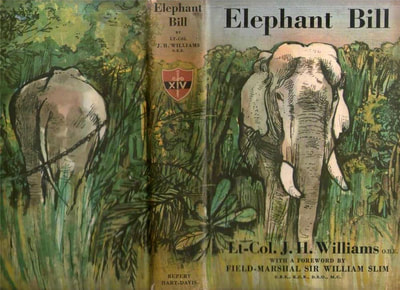

I always like to acquire the oldest hardback edition of these sorts of books. The main reason for this is that these often contain excellent photographs and maps, which sadly seem to disappear in later editions. My copy of Elephant Bill has no dust jacket and was an ex-library book printed in 1959, but contained no less than twenty black and white photographs depicting Williams' work with elephants in the teak industry. I also discovered that Williams was great friends with one of the lesser-known officers from Operation Longcloth, Captain Denis Clive Fish Herring, who supplied some of the photographs for the book.

From the pages of wikipedia:

James Howard Williams was born on the 15th November 1897 at St. Just in Cornwall. He was the son of a Cornish mining engineer who had once worked in South Africa and much like his elder brother, James studied at Queen's College, Taunton and the Camborne School of Mines and went on to serve as an officer in the Devonshire Regiment of the British Army in the Middle East during the First World War and later on in Afghanistan. During this time he served with the Camel Corps and as transport officer in charge of mules. After demobilisation he decided to join the Bombay-Burmah Trading Corporation as a forester working with trained elephants to extract teak logs.

During his service in the first war, he had read the book, The Diseases of the Camel and the Elephant, by H. P. Hawkes and decided he would be interested in a postwar job in Burma. So in 1920 he took up the position of a Forestry Assistant with the Bombay-Burmah Trading Corporation which milled teak in the Burmese jungles and used over 2000 elephants in this operation. Initially he was sent to a camp on the banks of the Chindwin River in Upper Burma. He was responsible for seventy elephants and their oozies (elephant handlers) in ten camps, in an area of about 400 square miles in the Myittha Valley, part of the Indaung Forest Reserve. The camps were often six or seven miles apart, with hills of three to four thousand feet high between them. In the teak process one tree was killed by ring-barking the base, then felled after standing in this condition for three years, so it had seasoned and was light enough to float downstream. The logs were hauled by elephants to a waterway, then floated down to Rangoon or Mandalay. Elephants were essential in the harvesting of teak; a single healthy elephant trained in the teak industry could be worth over $150,000.

In Burma, teak was as important a munition of war as steel and so timber extraction became an essential industry. Williams was based at Maymyo at the time of the Japanese invasion. Despite heavy criticism, the Bombay-Burmah Corporation arranged the evacuation of all European women and children from inside Burma in February 1942, using elephants for the evacuation rather than continuing with timber extraction. The retreat from Burma took these parties through to Assam via Imphal. The road to Assam went up the Chindwin River to Kalewa, then up the Kabaw Valley to Tamu and finally across the 5000ft mountains into Manipur and the Imphal Plain. Williams was attached to one evacuation party which included his own wife and children. The Kabaw Valley was nicknamed The Valley of Death because of the hundreds of refugees who died there from exhaustion, starvation and the tropical diseases of cholera, dysentery and smallpox.

After the initial retreat, Williams was employed producing timber surveys in Bengal and Assam and raising a labour corps. In October 1942 he joined the staff of the Eastern Army (later to become the 14th Army) as an Elephant Advisor to the Elephant Company of the Royal Indian Engineers. He was a Burmese speaker with knowledge of the country including the Irrawaddy River area and jungle tracks. He was initially posted to 4th Corps Headquarters at Jorhat in Assam.

Elephants were used being as sappers within the Royal Engineers, for use in bridge building in places where heavy equipment could otherwise not be brought in and were regarded simply as a branch of transport by their masters. Williams believed this to be a waste of the real benefit of elephants and their skill-set. It was during this time that Williams became known as Elephant Bill. General Slim, commander of the 14th Army, wrote: Elephants built hundreds of bridges for us, they helped to build and launch more ships for us than Helen ever did for Greece. Without them our retreat from Burma would have been even more arduous and our advance to its liberation slower and more difficult.

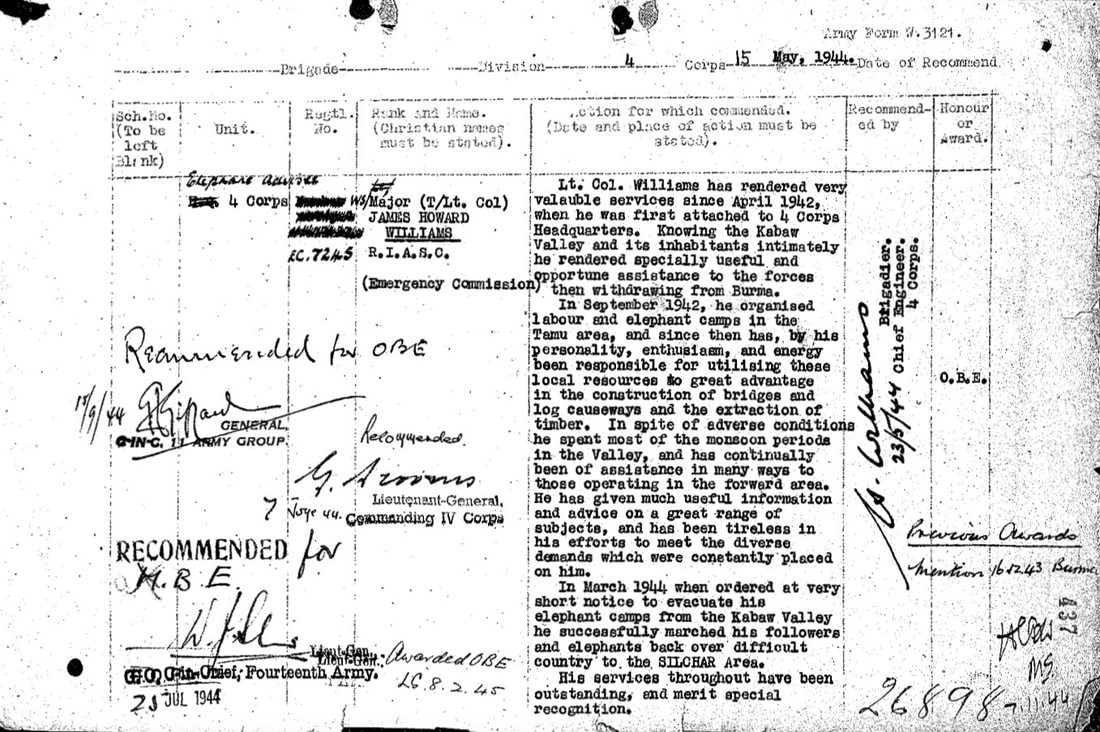

On the 15th May 1944, Williams was recommended for an OBE by Lieutenant-General G. Scoones, commander of IV Corps. The citation, shown below was counter-signed by General William Slim and the award announced amongst the pages of the London Gazette on the 8th February 1945. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

The book Elephant Bill became much more relevant to my research on the second read, when I discovered that Williams had rather reluctantly loaned some of his animals for work on Operation Longcloth. Indeed Williams' second book about his time with elephants, called Bandoola, refers to one of the animals he lent to Wingate in 1943. These animals were only supposed to assist in the movement of heavy supplies up until the Chindwin River. Sadly, they were eventually used to ferry the cargo across the river and one elephant was lost.

I always like to acquire the oldest hardback edition of these sorts of books. The main reason for this is that these often contain excellent photographs and maps, which sadly seem to disappear in later editions. My copy of Elephant Bill has no dust jacket and was an ex-library book printed in 1959, but contained no less than twenty black and white photographs depicting Williams' work with elephants in the teak industry. I also discovered that Williams was great friends with one of the lesser-known officers from Operation Longcloth, Captain Denis Clive Fish Herring, who supplied some of the photographs for the book.

From the pages of wikipedia:

James Howard Williams was born on the 15th November 1897 at St. Just in Cornwall. He was the son of a Cornish mining engineer who had once worked in South Africa and much like his elder brother, James studied at Queen's College, Taunton and the Camborne School of Mines and went on to serve as an officer in the Devonshire Regiment of the British Army in the Middle East during the First World War and later on in Afghanistan. During this time he served with the Camel Corps and as transport officer in charge of mules. After demobilisation he decided to join the Bombay-Burmah Trading Corporation as a forester working with trained elephants to extract teak logs.

During his service in the first war, he had read the book, The Diseases of the Camel and the Elephant, by H. P. Hawkes and decided he would be interested in a postwar job in Burma. So in 1920 he took up the position of a Forestry Assistant with the Bombay-Burmah Trading Corporation which milled teak in the Burmese jungles and used over 2000 elephants in this operation. Initially he was sent to a camp on the banks of the Chindwin River in Upper Burma. He was responsible for seventy elephants and their oozies (elephant handlers) in ten camps, in an area of about 400 square miles in the Myittha Valley, part of the Indaung Forest Reserve. The camps were often six or seven miles apart, with hills of three to four thousand feet high between them. In the teak process one tree was killed by ring-barking the base, then felled after standing in this condition for three years, so it had seasoned and was light enough to float downstream. The logs were hauled by elephants to a waterway, then floated down to Rangoon or Mandalay. Elephants were essential in the harvesting of teak; a single healthy elephant trained in the teak industry could be worth over $150,000.

In Burma, teak was as important a munition of war as steel and so timber extraction became an essential industry. Williams was based at Maymyo at the time of the Japanese invasion. Despite heavy criticism, the Bombay-Burmah Corporation arranged the evacuation of all European women and children from inside Burma in February 1942, using elephants for the evacuation rather than continuing with timber extraction. The retreat from Burma took these parties through to Assam via Imphal. The road to Assam went up the Chindwin River to Kalewa, then up the Kabaw Valley to Tamu and finally across the 5000ft mountains into Manipur and the Imphal Plain. Williams was attached to one evacuation party which included his own wife and children. The Kabaw Valley was nicknamed The Valley of Death because of the hundreds of refugees who died there from exhaustion, starvation and the tropical diseases of cholera, dysentery and smallpox.

After the initial retreat, Williams was employed producing timber surveys in Bengal and Assam and raising a labour corps. In October 1942 he joined the staff of the Eastern Army (later to become the 14th Army) as an Elephant Advisor to the Elephant Company of the Royal Indian Engineers. He was a Burmese speaker with knowledge of the country including the Irrawaddy River area and jungle tracks. He was initially posted to 4th Corps Headquarters at Jorhat in Assam.

Elephants were used being as sappers within the Royal Engineers, for use in bridge building in places where heavy equipment could otherwise not be brought in and were regarded simply as a branch of transport by their masters. Williams believed this to be a waste of the real benefit of elephants and their skill-set. It was during this time that Williams became known as Elephant Bill. General Slim, commander of the 14th Army, wrote: Elephants built hundreds of bridges for us, they helped to build and launch more ships for us than Helen ever did for Greece. Without them our retreat from Burma would have been even more arduous and our advance to its liberation slower and more difficult.

On the 15th May 1944, Williams was recommended for an OBE by Lieutenant-General G. Scoones, commander of IV Corps. The citation, shown below was counter-signed by General William Slim and the award announced amongst the pages of the London Gazette on the 8th February 1945. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

After the war Williams retired to St Buryan in Cornwall and worked as an author and market gardener. He had married Susan Margaret Rowland in 1932 after they met in Burma and they had two children, son Treve and daughter Lamorna. After Williams death in July 1958, his wife Susan wrote about their life together in the book, The Footprints of Elephant Bill.

Books written by J.H. Williams include:

Elephant Bill. Published by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1950.

Bandoola. Published by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1953.

The Spotted Deer. Published by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1957.

Big Charlie. Published by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1959.

In Quest of a Mermaid. Published by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1960.

A film named Bandoola was planned in 1956 by production company, Hecht-Hill-Lancaster and United Artists. It was scheduled to be filmed in Ceylon from November that year, with Ernest Borgnine and Sophia Loren in the leading roles. Sadly, it never materialised.

In 2015, author Vicki Croke re-visited the story of Elephant Bill and his exploits during WW2 in her publication, Elephant Company. For more information about this book, please click on the following link:

www.amazon.co.uk/Elephant-Company-Inspiring-Unlikely-Animals/dp/0812981650

To conclude this narrative, seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the story of J.H. Williams or Elephant Bill. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. This page is dedicated to James Howard Williams and his many elephants, just some of the unsung heroes from the Burma Campaign.

Books written by J.H. Williams include:

Elephant Bill. Published by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1950.

Bandoola. Published by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1953.

The Spotted Deer. Published by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1957.

Big Charlie. Published by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1959.

In Quest of a Mermaid. Published by Rupert Hart-Davis in 1960.

A film named Bandoola was planned in 1956 by production company, Hecht-Hill-Lancaster and United Artists. It was scheduled to be filmed in Ceylon from November that year, with Ernest Borgnine and Sophia Loren in the leading roles. Sadly, it never materialised.

In 2015, author Vicki Croke re-visited the story of Elephant Bill and his exploits during WW2 in her publication, Elephant Company. For more information about this book, please click on the following link:

www.amazon.co.uk/Elephant-Company-Inspiring-Unlikely-Animals/dp/0812981650

To conclude this narrative, seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the story of J.H. Williams or Elephant Bill. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. This page is dedicated to James Howard Williams and his many elephants, just some of the unsung heroes from the Burma Campaign.

Update 15/05/2020.

I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Rob Tandy:

Dear Steve, I was thinking about Elephant Bill today and came across your website. I think you've made a really great homage to all those who were involved in the Burma campaign. Your passion and respect really shines through those pages. Jim Williams was my Gran's cousin and copies of his books were always knocking around somewhere in her house when I was a child. I remember her talking about him when I was down in St. Just, on visits to her home on the outskirts of the town. I reckon there may be some other stuff relating to him somewhere in the family albums. I do have a little ink sketch drawing of St. Just Church made by his wife Susan in 1952, which I believe she gave to my grandparents at some stage.

Anyway, just thought I'd say hello and to keep up the good work. Reading work like yours, makes what we are going through right now (coronavirus) seem not so bad really. Kind regards, Rob.

I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Rob Tandy:

Dear Steve, I was thinking about Elephant Bill today and came across your website. I think you've made a really great homage to all those who were involved in the Burma campaign. Your passion and respect really shines through those pages. Jim Williams was my Gran's cousin and copies of his books were always knocking around somewhere in her house when I was a child. I remember her talking about him when I was down in St. Just, on visits to her home on the outskirts of the town. I reckon there may be some other stuff relating to him somewhere in the family albums. I do have a little ink sketch drawing of St. Just Church made by his wife Susan in 1952, which I believe she gave to my grandparents at some stage.

Anyway, just thought I'd say hello and to keep up the good work. Reading work like yours, makes what we are going through right now (coronavirus) seem not so bad really. Kind regards, Rob.

Update 22/10/2022.

From the pages of Elephant Bill, I have learned that another man, Stanley 'Chindwin' White was heavily involved in the supply and management of the elephants used on the first Chindit expedition in 1943. A former captain for the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company before the war, he had to scuttle his boat during the retreat from Burma in early 1942 and escape to the safety of the Chindwin River. He later met up with James Williams at the Tea Planters Club in Jorhat and became part of the elephant administration team. Stanley White worked closely with Brigadier Wingate January 1943, in the provision of the elephants to be used during the early stages of Operation Longcloth.

From the pages of Elephant Bill, I have learned that another man, Stanley 'Chindwin' White was heavily involved in the supply and management of the elephants used on the first Chindit expedition in 1943. A former captain for the Irrawaddy Flotilla Company before the war, he had to scuttle his boat during the retreat from Burma in early 1942 and escape to the safety of the Chindwin River. He later met up with James Williams at the Tea Planters Club in Jorhat and became part of the elephant administration team. Stanley White worked closely with Brigadier Wingate January 1943, in the provision of the elephants to be used during the early stages of Operation Longcloth.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Wikipedia, October 2017.