Flight Lieutenant Denis J.T. Sharp DFC

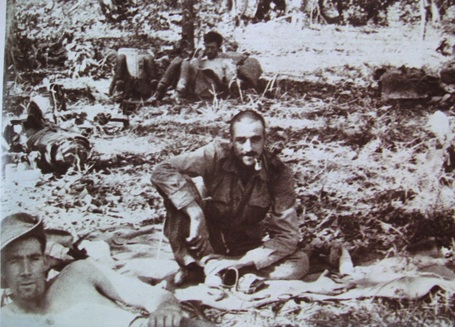

Denny Sharp (with pipe), photographed with his own camera in Burma in 1943.

'Officer in charge of droppings.'

This was the nickname given to Denis Sharp by his Chindit commander in 1943, Major Bernard Fergusson. It was something that, although delivered in good humour, was to annoy the Air Liaison officer from Column 5 throughout his time behind enemy lines that year.

Born in August 1918 and from Dunedin, New Zealand, Denny was to become one of the most vital components of Fergusson's unit on Wingate's fledgling Chindit expedition. Acting as Air Liaison officer, his role was central in the choosing and setting up of Supply Drop locations and for guiding the Dakota and Hudson aircraft to these drop zones from his position on the ground. His job was at the heart of Chindit philosophy and survival.

Denis had had a busy war, which saw him in action over Britain, Malaya and India, before he volunteered for an unknown special mission which turned out to be Operation Longcloth.

He entered Longcloth training fairly late, joining Column 5 in November 1942, whilst they were stationed at a place called Bahron. Here is how fellow Column 5 officer Philip Stibbe remembers his first meeting with Flight Lieutenant Sharp:

"During Chindit training we certainly did have some very enjoyable evenings around the fire. The Major had been in Palestine and Syria and had been A.D.C. to General Wavell; he had also been with Anthony Eden in Turkey and fought in the western desert. He had a remarkable gift for bringing each one of us into the discussion so that no one ever felt left out.

Denny Sharp was one of three new arrivals at our camp at Bahron, like many worthwhile people, he took a bit of getting to know, but the effort was well rewarded. He would throw some perfectly outrageous remark into the discussion, scowling fiercely as if challenging anyone not to take it seriously, and then he would lose control of his face and the most infectious grin would spread over his features. Denny also brought with him several RAF signallers to work our large wireless sets."

Denis thrived on his new role and soon became an integral and popular part of Column 5. In fact his talents were so well observed, that he was chosen to form part of a pre-operational scouting mission in January 1943 led by senior Burma Rifles officer, Lieutenant-Colonel L.G. Wheeler. This party was to cross over the River Chindwin and check the eastern banks for signs of the enemy, Denny Sharp's task was to find a suitable location for a large supply drop which was planned once the columns had crossed the river on the actual operation. Here is a paraphrased quote from 'Wingate's Raiders', written by Charles J. Rolo and describes the make up of Colonel Wheeler's group.

"Three days before the main body left Imphal Wingate had dispatched an advanced party under Lt. Colonel Wheeler, commanding officer of the Burma Rifles, to reconnoitre the crossing and establish a bridgehead on the east bank. With Wheeler was Flight Lieutenant Robert Thompson, at 27 years old Thompson had already covered a good deal of ground in the Far East and he was to be of great assistance to many of the other liaison officers over the coming months in Burma. Also in Wheeler's group was the only American in Wingate's mob, Flight Lieutenant James Gibson, known as 'Carolina'. Tanned a reddish-brown, with blue eyes, fairish hair, and a deceptively debonair appearance, he was Hollywood's idea of how a fighter pilot should look.

Gibson had joined the RCAF at the outbreak of war, helped to knock the Luftwaffe out of the skies over Britain, and was transferred to India in time to discourage the Japanese nuisance raiders from venturing near Calcutta. With a large bag of Zeros to his credit, he had volunteered for the Wingate expedition. "I'm sick of shooting down Jap planes," he explained. "I want to see the little devils faces when they finally get it."

The third RAF officer in the advanced party was Flight Lieutenant Denny Sharp, a New Zealand born Hurricane pilot, who had fought in Malaya, before escaping through Sumatra, and later had taken a high toll of Japanese planes in the enemies disastrous large-scale raid on Ceylon. He looked like a cross between a Commando and a hill-billy with his floppy hat, untrimmed black moustache, and four day old beard. All three were to be vital in linking the sky to the ground on the operation proper."

This was the nickname given to Denis Sharp by his Chindit commander in 1943, Major Bernard Fergusson. It was something that, although delivered in good humour, was to annoy the Air Liaison officer from Column 5 throughout his time behind enemy lines that year.

Born in August 1918 and from Dunedin, New Zealand, Denny was to become one of the most vital components of Fergusson's unit on Wingate's fledgling Chindit expedition. Acting as Air Liaison officer, his role was central in the choosing and setting up of Supply Drop locations and for guiding the Dakota and Hudson aircraft to these drop zones from his position on the ground. His job was at the heart of Chindit philosophy and survival.

Denis had had a busy war, which saw him in action over Britain, Malaya and India, before he volunteered for an unknown special mission which turned out to be Operation Longcloth.

He entered Longcloth training fairly late, joining Column 5 in November 1942, whilst they were stationed at a place called Bahron. Here is how fellow Column 5 officer Philip Stibbe remembers his first meeting with Flight Lieutenant Sharp:

"During Chindit training we certainly did have some very enjoyable evenings around the fire. The Major had been in Palestine and Syria and had been A.D.C. to General Wavell; he had also been with Anthony Eden in Turkey and fought in the western desert. He had a remarkable gift for bringing each one of us into the discussion so that no one ever felt left out.

Denny Sharp was one of three new arrivals at our camp at Bahron, like many worthwhile people, he took a bit of getting to know, but the effort was well rewarded. He would throw some perfectly outrageous remark into the discussion, scowling fiercely as if challenging anyone not to take it seriously, and then he would lose control of his face and the most infectious grin would spread over his features. Denny also brought with him several RAF signallers to work our large wireless sets."

Denis thrived on his new role and soon became an integral and popular part of Column 5. In fact his talents were so well observed, that he was chosen to form part of a pre-operational scouting mission in January 1943 led by senior Burma Rifles officer, Lieutenant-Colonel L.G. Wheeler. This party was to cross over the River Chindwin and check the eastern banks for signs of the enemy, Denny Sharp's task was to find a suitable location for a large supply drop which was planned once the columns had crossed the river on the actual operation. Here is a paraphrased quote from 'Wingate's Raiders', written by Charles J. Rolo and describes the make up of Colonel Wheeler's group.

"Three days before the main body left Imphal Wingate had dispatched an advanced party under Lt. Colonel Wheeler, commanding officer of the Burma Rifles, to reconnoitre the crossing and establish a bridgehead on the east bank. With Wheeler was Flight Lieutenant Robert Thompson, at 27 years old Thompson had already covered a good deal of ground in the Far East and he was to be of great assistance to many of the other liaison officers over the coming months in Burma. Also in Wheeler's group was the only American in Wingate's mob, Flight Lieutenant James Gibson, known as 'Carolina'. Tanned a reddish-brown, with blue eyes, fairish hair, and a deceptively debonair appearance, he was Hollywood's idea of how a fighter pilot should look.

Gibson had joined the RCAF at the outbreak of war, helped to knock the Luftwaffe out of the skies over Britain, and was transferred to India in time to discourage the Japanese nuisance raiders from venturing near Calcutta. With a large bag of Zeros to his credit, he had volunteered for the Wingate expedition. "I'm sick of shooting down Jap planes," he explained. "I want to see the little devils faces when they finally get it."

The third RAF officer in the advanced party was Flight Lieutenant Denny Sharp, a New Zealand born Hurricane pilot, who had fought in Malaya, before escaping through Sumatra, and later had taken a high toll of Japanese planes in the enemies disastrous large-scale raid on Ceylon. He looked like a cross between a Commando and a hill-billy with his floppy hat, untrimmed black moustache, and four day old beard. All three were to be vital in linking the sky to the ground on the operation proper."

During the early weeks of the full operation things went well for Column 5, they achieved an unopposed crossing of the Chindwin at a place called Tonhe. They had successfully moved through the jungle and reached their first objective, the railway at Bonchaung. Here the 142 Commando platoon proceeded to blow the bridge over the gorge and destroy as much of the rail track as possible. Fergusson led the unit on towards the Irrawaddy Delta and it was from here that things began to unwind. From his book 'Wild Green Earth':

"In 1943 the first two supply drops were on a grand scale, catering for Brigade Headquarters and five other columns. With so few aircraft, they took three days to accomplish this, and it seemed incredible that the Japanese should not get wind of them and fight for the drop. They didn't; but I was glad that after that period we had drops to individual columns only.

My own column was unlucky; we were the leading column for much of the time, and it was thought that a drop on us a few days ahead of the main body would give away Wingate's intentions to the enemy. The result was that I only got two drops: both beyond the Irrawaddy, and my total receipt of rations over more than 70 days inside Burma amounted to only 20 days worth of food.

We had Royal Air Force officers with us, and they were always first class. In 1943 they were invited to volunteer for special a mission, of which the nature was unspecified; they all thought they were going to fly some new type of aircraft; and the language when they heard that, instead, they were going to march more than a thousand miles through Burma, was not of the choicest. Their duty that first year was primarily to organise supply drops, and secondly to get some experience in that art. We used to torment ours, Flight Lieutenant Denny Sharp, by describing him as "Officer in Charge of Droppings", which he did not like."

Later on in March the column reached the western banks of the Irrawaddy and secured the village of Tigyaing by posting machine guns on all roads and pathways into the village, Fergusson then proceeded to secure boats to ferry his men across the river. A short time before they had reached Tigyaing the column had been spotted by a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft, this brought another of those trademark caustic responses from Flight Lieutenant Sharp. Fergusson recalls:

"At 4 o'clock in the afternoon, we were just crossing some paddy fields when a Jap aircraft came over us at about 1000 feet. It was a chance we had taken 50 times before without being seen, but this time we were caught well and truly out in the open. The aircraft circled us twice; one could imagine the little, malevolent yellow face of the pilot, staring down from his goggles and counting us as he banked away; and then he flew off southward. Denny Sharp growled, "If I had my way and I had been up there with a Hurricane, then he (the Japanese pilot) would be down here by now."

This was typical of Denny. The next day after a fearful march, with the sun blazing and absolutely no shade, at our first halt Denny pinched the slender tree I had in mind for my own benefit: I remember and am still ashamed of the way in which I told him to go and find another tree."

Column 5 moved off from the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy and continued their journey through the jungles of Burma, by late March they found themselves nearing a village called Hintha. It was here that the column met their 'Waterloo' and a fierce firefight took place against a Japanese patrol present in the village. After a violent hand to hand struggle lasting several hours, the unit broke away and dispersed toward the north east. Unfortunately the unit had lost cohesion and many men failed to re-join the column at the next agreed rendezvous. Denny Sharp took command of a large group of soldiers after the battle of Hintha, many of whom were to remain with the Flight Lieutenant for the rest of the expedition. Once the remnants of the column were together again, Major Fergusson decided to divide the men into three dispersal groups and head westward once more and home.

"After our skirmish at Hintha I organised all the men into three sections and I had Tommy Roberts and Denny Sharp command one each while I looked after the third. I had relied upon Denny more than once on the operation and he had always come up trumps. It was at this point and with a little sadness I watched the two groups move away from my party and headed down towards the Irrawaddy River once more.

Later on when we had been apart for around two weeks and whilst my party and I were sitting in a village next to the Headman's house, we spotted coming down the hill track a group of soldiers. As we sat, we saw, coming up along the path slowly from the south, a path so steep that our hearts bled for the men upon it, a group we knew at once must be Denny's. In the end both our parties crossed the Chindwin within hours of each other, with Sharp's group beating mine by around six hours."

"In 1943 the first two supply drops were on a grand scale, catering for Brigade Headquarters and five other columns. With so few aircraft, they took three days to accomplish this, and it seemed incredible that the Japanese should not get wind of them and fight for the drop. They didn't; but I was glad that after that period we had drops to individual columns only.

My own column was unlucky; we were the leading column for much of the time, and it was thought that a drop on us a few days ahead of the main body would give away Wingate's intentions to the enemy. The result was that I only got two drops: both beyond the Irrawaddy, and my total receipt of rations over more than 70 days inside Burma amounted to only 20 days worth of food.

We had Royal Air Force officers with us, and they were always first class. In 1943 they were invited to volunteer for special a mission, of which the nature was unspecified; they all thought they were going to fly some new type of aircraft; and the language when they heard that, instead, they were going to march more than a thousand miles through Burma, was not of the choicest. Their duty that first year was primarily to organise supply drops, and secondly to get some experience in that art. We used to torment ours, Flight Lieutenant Denny Sharp, by describing him as "Officer in Charge of Droppings", which he did not like."

Later on in March the column reached the western banks of the Irrawaddy and secured the village of Tigyaing by posting machine guns on all roads and pathways into the village, Fergusson then proceeded to secure boats to ferry his men across the river. A short time before they had reached Tigyaing the column had been spotted by a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft, this brought another of those trademark caustic responses from Flight Lieutenant Sharp. Fergusson recalls:

"At 4 o'clock in the afternoon, we were just crossing some paddy fields when a Jap aircraft came over us at about 1000 feet. It was a chance we had taken 50 times before without being seen, but this time we were caught well and truly out in the open. The aircraft circled us twice; one could imagine the little, malevolent yellow face of the pilot, staring down from his goggles and counting us as he banked away; and then he flew off southward. Denny Sharp growled, "If I had my way and I had been up there with a Hurricane, then he (the Japanese pilot) would be down here by now."

This was typical of Denny. The next day after a fearful march, with the sun blazing and absolutely no shade, at our first halt Denny pinched the slender tree I had in mind for my own benefit: I remember and am still ashamed of the way in which I told him to go and find another tree."

Column 5 moved off from the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy and continued their journey through the jungles of Burma, by late March they found themselves nearing a village called Hintha. It was here that the column met their 'Waterloo' and a fierce firefight took place against a Japanese patrol present in the village. After a violent hand to hand struggle lasting several hours, the unit broke away and dispersed toward the north east. Unfortunately the unit had lost cohesion and many men failed to re-join the column at the next agreed rendezvous. Denny Sharp took command of a large group of soldiers after the battle of Hintha, many of whom were to remain with the Flight Lieutenant for the rest of the expedition. Once the remnants of the column were together again, Major Fergusson decided to divide the men into three dispersal groups and head westward once more and home.

"After our skirmish at Hintha I organised all the men into three sections and I had Tommy Roberts and Denny Sharp command one each while I looked after the third. I had relied upon Denny more than once on the operation and he had always come up trumps. It was at this point and with a little sadness I watched the two groups move away from my party and headed down towards the Irrawaddy River once more.

Later on when we had been apart for around two weeks and whilst my party and I were sitting in a village next to the Headman's house, we spotted coming down the hill track a group of soldiers. As we sat, we saw, coming up along the path slowly from the south, a path so steep that our hearts bled for the men upon it, a group we knew at once must be Denny's. In the end both our parties crossed the Chindwin within hours of each other, with Sharp's group beating mine by around six hours."

From a witness statement given by CQMS. E. Henderson after reaching the safety of Allied held territory, comes this account of the period directly after the action at Hintha.

"I was with number five Column of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, during operations in Burma in 1943. The under-mentioned British Other Ranks were in my dispersal group all the way through the campaign until we made contact with the enemy in a village in Burma called Hintha.

After the action in that village was over, the under-mentioned soldiers were still in my dispersal group, which was then commanded by Flight Lieutenant Sharp of the RAF. We halted and unsaddled our mules so we could go ahead much quicker.

After starting off from that halt, which was approximately 2 miles from Hintha, we were attacked by a Japanese patrol. This caused a gap in the column, but we kept marching for approximately another 4 miles and then stopped, we waited for these people to catch up, but they must have gone wrong way, because they did not rejoin us again. I saw all the under-mentioned men for the last time approximately two and a half miles north east of Hintha. They were all alive, and last seen on 28th March 1943."

Signed by, CQMS. E.G. Henderson, 13th Kings Regiment.

The men in question did not attempt to re-join any of Fergusson's three main dispersal parties, but instead marched off in a more northerly direction, where eventually they met up with Major Gilkes and the majority of Column 7. Many of these soldiers never made it out of Burma alive in 1943, some perished on the arduous journey north towards the Chinese borders, while others became prisoners of war and died in captivity.

Here, in no particular order are their names:

"I was with number five Column of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, during operations in Burma in 1943. The under-mentioned British Other Ranks were in my dispersal group all the way through the campaign until we made contact with the enemy in a village in Burma called Hintha.

After the action in that village was over, the under-mentioned soldiers were still in my dispersal group, which was then commanded by Flight Lieutenant Sharp of the RAF. We halted and unsaddled our mules so we could go ahead much quicker.

After starting off from that halt, which was approximately 2 miles from Hintha, we were attacked by a Japanese patrol. This caused a gap in the column, but we kept marching for approximately another 4 miles and then stopped, we waited for these people to catch up, but they must have gone wrong way, because they did not rejoin us again. I saw all the under-mentioned men for the last time approximately two and a half miles north east of Hintha. They were all alive, and last seen on 28th March 1943."

Signed by, CQMS. E.G. Henderson, 13th Kings Regiment.

The men in question did not attempt to re-join any of Fergusson's three main dispersal parties, but instead marched off in a more northerly direction, where eventually they met up with Major Gilkes and the majority of Column 7. Many of these soldiers never made it out of Burma alive in 1943, some perished on the arduous journey north towards the Chinese borders, while others became prisoners of war and died in captivity.

Here, in no particular order are their names:

|

3777480 Pte. F. Townson

3777998 Pte. R. Hulme 4195166 Pte. E. Kenna 5114059 Pte. N.J. Fowler 3781718 Pte. E. Hodnett 5114104 Pte. J. Powell 3779270 Pte. W.C. Parry 5119069 L. Corp. T. Jones |

3523186 Pte. F.C. Fairhurst

4198452 Pte. J. Fitzpatrick 3186149 Corp. W. McGee 5119278 Pte. J. Donovan 3779346 Pte. D. Clarke 3779444 Pte. T. A. James 4202370 Pte. W. Roche Sgt. R.A. Rothwell BEM. |

The Distinguished Flying Cross or DFC.

As mentioned earlier, Denis Sharp had proved himself a worthy fighting man during his service in WW2. Here are the details of his service and the gallantry awards he received:

NZ-2145 Squadron Leader, Denis J. T. Sharp.

DFC, Mid(2). Born Dunedin, 30th Aug 1918; RAF 24th July 1939 to 31st December 1943, RAF number 42729; RNZAF 1st January 1944 to 17th November 1945; Pilot, later Squadron Leader D J T Sharp. RAF 1950 to 30th September 1958.

Citation Mention in Despatches (1) (Gazetted 16th December 1943): For meritorious service. Presumably for his efforts during Operation Longcloth.

Citation Distinguished Flying Cross (Gazetted 7th August 1944): This officer has completed a large number of sorties (flying Hurricanes), many of them against dangerous and difficult targets. He has displayed a high degree of skill and courage, setting an example which has been reflected in the operational efficiency of the squadron. He has destroyed three enemy aircraft.

Citation Mention in Despatches (2) (Gazetted 14th June 1945): For distinguished service with 11 Squadron RAF March-December 1944. On 27th January 1942 Squadron Leader Sharp flew a Hurricane of 258 Sqn. RAF off the deck of HMS INDOMITABLE to Batavia, his first tour being with 258 Sqn. in the UK and then the Far East. His second was flown with 5 and 11 Sqns. RAF (both Hurricane) in India and Burma. By mid-1944 he had flown 450 sorties and had also served as an Air Liaison Officer with 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in 1943 with Wingate's expedition into Burma. When the Chindit Brigade split up, on it's return to India, he was given command of one of the parties and in the hard and dangerous march back kept his men going with fine example and determination. He took part in a number of pitched battles with the Japanese during the course of this forced march.

NZ-2145 Squadron Leader, Denis J. T. Sharp.

DFC, Mid(2). Born Dunedin, 30th Aug 1918; RAF 24th July 1939 to 31st December 1943, RAF number 42729; RNZAF 1st January 1944 to 17th November 1945; Pilot, later Squadron Leader D J T Sharp. RAF 1950 to 30th September 1958.

Citation Mention in Despatches (1) (Gazetted 16th December 1943): For meritorious service. Presumably for his efforts during Operation Longcloth.

Citation Distinguished Flying Cross (Gazetted 7th August 1944): This officer has completed a large number of sorties (flying Hurricanes), many of them against dangerous and difficult targets. He has displayed a high degree of skill and courage, setting an example which has been reflected in the operational efficiency of the squadron. He has destroyed three enemy aircraft.

Citation Mention in Despatches (2) (Gazetted 14th June 1945): For distinguished service with 11 Squadron RAF March-December 1944. On 27th January 1942 Squadron Leader Sharp flew a Hurricane of 258 Sqn. RAF off the deck of HMS INDOMITABLE to Batavia, his first tour being with 258 Sqn. in the UK and then the Far East. His second was flown with 5 and 11 Sqns. RAF (both Hurricane) in India and Burma. By mid-1944 he had flown 450 sorties and had also served as an Air Liaison Officer with 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in 1943 with Wingate's expedition into Burma. When the Chindit Brigade split up, on it's return to India, he was given command of one of the parties and in the hard and dangerous march back kept his men going with fine example and determination. He took part in a number of pitched battles with the Japanese during the course of this forced march.

Denis Sharp, seen before Operation Longcloth.

Denis Sharp sadly died in 2004. He had moved to Australia after the war and made his new family home in Sydney. The Sydney Morning Herald recorded his obituary in their edition printed on the 6th February, the article was written by Gary Scully.

One of Churchill's Heroic Few

Denis (Denny) Sharp, WWII hero, yachtsman, 1918-2004.

The airmen he commanded had called him, affectionately, "the Black Prince". Until his peaceful death, aged 85, at home in Tweed Heads, Denis (Denny) Sharp had been one of the last remaining heroes of the World War II Battle of Britain.

He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his wartime exploits - after fighting the German Luftwaffe in the skies over Britain, he saw action above France, Germany, Singapore, India and in a gruelling ground campaign with General Orde Wingate's "Chindits" in Burma.

Sharp's aircraft was the legendary Hawker Hurricane. Defying the statistics on the average life of the fighter pilot, he survived air combat for six years and a crash in Indonesia after he had flown the last Hurricane out of Singapore before its surrender to the Japanese. His remarkable wartime career has been referred to in books by more than a dozen authors.

A native of New Zealand, Sharp brought his family to Australia after the war. He became known to many Sydneysiders as a champion yachtsman, and a member of the Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club at Newport. His wife, Beverley, also became prominent with her own television segment about craft and needlework, So Cleverly with Beverley, which ran for four years (1977-81) on Channel Ten's Good Morning Australia. They were to make many new friends on the Tweed and the Gold Coast after retirement.

Denis John Sharp was born in Dunedin, New Zealand, the son of hotelier John Sharp and his wife, Margaret. His boyhood hobbies included hunting and fishing - while still at Otago High School, at the age of 17 he was awarded the Kings Empire Medal for shooting.

His first job was with the government printing office, but the memory of a bi-plane on a barnstorming tour touching down in a tricky landing near his home in 1934 had left him with a yearning desire to be an airman.

His chance came in 1939 when the New Zealand government was offering flying training commissions in the RNZAF, to recruit pilots to ferry aircraft from Britain to New Zealand. He arrived in England in June 1939 for his flying training, and when war broke out three months later, he transferred to the RAF, stationed first at Kenley near the RAF fighter command at Biggin Hill.

Later he was incorporated into 258 Squadron, comprised mainly of New Zealanders, with the silver fern as its emblem.

Squadron 258 was in the thick of the action when the Battle of Britain began in the skies over southern England in July 1940, the Hurricanes and Spitfires of the RAF heavily outnumbered by the might of the German Luftwaffe. Their legendary success in denying Germany air supremacy ended plans for an invasion of Britain and became a turning point in the war.

Sharp's leadership and flying ability had earned him rapid promotion and during the Battle of Britain he was a Flight Commander. One of his wartime mates was Douglas "Tin Legs" Bader, another was Bernard Fergusson, a column leader in the "Chindits" and later to be knighted and Governor General of New Zealand.

Because of his dashing, dark good looks (often compared to Errol Flynn or Ronald Coleman) his men dubbed him "the Black Prince" - a sobriquet which was to stick to him throughout the war and at many reunions.

In later air combat, Sharp rose to the rank of Squadron Leader. After fighting in the skies over France and Germany, he realised a change was imminent when his unit was trained in short take-offs and landings for aircraft carriers.

However, their intended carrier, the Ark Royal, was sunk and they were taken on by the Indomitable, to fly from the carrier to Singapore where aircraft were desperately needed against the rapidly advancing Japanese. Flying the last Hurricane out of the beleaguered city, Sharp ran out of fuel and crashed at Singkep in Indonesia, wrecking his plane but escaping with minor injuries.

As the Japanese tightened their hold on Indonesia, and after a series of hair-raising exploits, he escaped by fishing boat to Colombo.

It was there that he volunteered for an unspecified "special mission", believing it would get him back in the air again. Instead, he found himself trekking for three months behind Japanese lines in Burma as air-controller for Wingate's guerilla force, the Chindits, directing the air drops that supplied them. It was a risky, dangerous mission and only about one-third of the Chindits returned. However, they had shown that it was possible to infiltrate and operate in difficult jungle terrain deep in enemy-held territory.

Sharp was later to command two Air Squadrons in India. Towards the end of the war, having renewed his commission with the RNZAF, he returned to New Zealand in early 1945 to convert to Corsair fighters for the Pacific air war. It was there that he renewed his friendship with Beverley Bryant, whom he had last seen six years before as a 15-year old at his farewell before leaving for England.

There was a whirlwind courtship and the couple eloped while Sharp was awaiting his re-posting to Pacific air combat. He was still in New Zealand when Japan surrendered.

In the immediate postwar years he rejoined the RAF, training pilots on Vampire, Meteor and Lightning jet aircraft.

After finally resigning his commission, he brought his family to Australia in 1959. As Beverley puts it: "We pored through an atlas in London looking for the best place to bring up our four boys, and we decided Australia was it."

Sharp bought The Henley South Hotel in South Australia and spent four years there until he and Beverley, caravanning to Cairns, were entranced by Sydney's Pittwater. He moved the family to Newport, in a house next door to the Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club, and set up business locally as a glass merchant.

He was to spend the next 30 years as a keen and popular member of the yacht club, winning many championships in several different yachts, from the Diamond class to Compass 29 and Catalina 30s.

Beverley says his crewmen nicknamed him "Araldite" because they couldn't pry him loose for a turn at the tiller.

It was the warmer weather that enticed him and Beverley to Tweed Heads in 1993, and Sharp was active in the Currumbin-Palm Beach RSL sub-branch and club across the Queensland border. Many of its members joined family and friends in a funeral service at Tweed Heads to hear a moving eulogy by Beverley, his wife of 60 years.

She recalled Winston Churchill's memorable phrase about the Battle of Britain: "Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few." "Denny," she said, "was one of those few."

Denis John Sharp is survived by Beverley and their four sons, Denis, Rodney, Geoffrey and Gary. Friends and family are planning a further memorial service for Sharp at his beloved Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club on February 8. His sons and grandchildren will join former crewmen on board a yacht, to scatter his ashes in Pittwater.

One of Churchill's Heroic Few

Denis (Denny) Sharp, WWII hero, yachtsman, 1918-2004.

The airmen he commanded had called him, affectionately, "the Black Prince". Until his peaceful death, aged 85, at home in Tweed Heads, Denis (Denny) Sharp had been one of the last remaining heroes of the World War II Battle of Britain.

He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for his wartime exploits - after fighting the German Luftwaffe in the skies over Britain, he saw action above France, Germany, Singapore, India and in a gruelling ground campaign with General Orde Wingate's "Chindits" in Burma.

Sharp's aircraft was the legendary Hawker Hurricane. Defying the statistics on the average life of the fighter pilot, he survived air combat for six years and a crash in Indonesia after he had flown the last Hurricane out of Singapore before its surrender to the Japanese. His remarkable wartime career has been referred to in books by more than a dozen authors.

A native of New Zealand, Sharp brought his family to Australia after the war. He became known to many Sydneysiders as a champion yachtsman, and a member of the Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club at Newport. His wife, Beverley, also became prominent with her own television segment about craft and needlework, So Cleverly with Beverley, which ran for four years (1977-81) on Channel Ten's Good Morning Australia. They were to make many new friends on the Tweed and the Gold Coast after retirement.

Denis John Sharp was born in Dunedin, New Zealand, the son of hotelier John Sharp and his wife, Margaret. His boyhood hobbies included hunting and fishing - while still at Otago High School, at the age of 17 he was awarded the Kings Empire Medal for shooting.

His first job was with the government printing office, but the memory of a bi-plane on a barnstorming tour touching down in a tricky landing near his home in 1934 had left him with a yearning desire to be an airman.

His chance came in 1939 when the New Zealand government was offering flying training commissions in the RNZAF, to recruit pilots to ferry aircraft from Britain to New Zealand. He arrived in England in June 1939 for his flying training, and when war broke out three months later, he transferred to the RAF, stationed first at Kenley near the RAF fighter command at Biggin Hill.

Later he was incorporated into 258 Squadron, comprised mainly of New Zealanders, with the silver fern as its emblem.

Squadron 258 was in the thick of the action when the Battle of Britain began in the skies over southern England in July 1940, the Hurricanes and Spitfires of the RAF heavily outnumbered by the might of the German Luftwaffe. Their legendary success in denying Germany air supremacy ended plans for an invasion of Britain and became a turning point in the war.

Sharp's leadership and flying ability had earned him rapid promotion and during the Battle of Britain he was a Flight Commander. One of his wartime mates was Douglas "Tin Legs" Bader, another was Bernard Fergusson, a column leader in the "Chindits" and later to be knighted and Governor General of New Zealand.

Because of his dashing, dark good looks (often compared to Errol Flynn or Ronald Coleman) his men dubbed him "the Black Prince" - a sobriquet which was to stick to him throughout the war and at many reunions.

In later air combat, Sharp rose to the rank of Squadron Leader. After fighting in the skies over France and Germany, he realised a change was imminent when his unit was trained in short take-offs and landings for aircraft carriers.

However, their intended carrier, the Ark Royal, was sunk and they were taken on by the Indomitable, to fly from the carrier to Singapore where aircraft were desperately needed against the rapidly advancing Japanese. Flying the last Hurricane out of the beleaguered city, Sharp ran out of fuel and crashed at Singkep in Indonesia, wrecking his plane but escaping with minor injuries.

As the Japanese tightened their hold on Indonesia, and after a series of hair-raising exploits, he escaped by fishing boat to Colombo.

It was there that he volunteered for an unspecified "special mission", believing it would get him back in the air again. Instead, he found himself trekking for three months behind Japanese lines in Burma as air-controller for Wingate's guerilla force, the Chindits, directing the air drops that supplied them. It was a risky, dangerous mission and only about one-third of the Chindits returned. However, they had shown that it was possible to infiltrate and operate in difficult jungle terrain deep in enemy-held territory.

Sharp was later to command two Air Squadrons in India. Towards the end of the war, having renewed his commission with the RNZAF, he returned to New Zealand in early 1945 to convert to Corsair fighters for the Pacific air war. It was there that he renewed his friendship with Beverley Bryant, whom he had last seen six years before as a 15-year old at his farewell before leaving for England.

There was a whirlwind courtship and the couple eloped while Sharp was awaiting his re-posting to Pacific air combat. He was still in New Zealand when Japan surrendered.

In the immediate postwar years he rejoined the RAF, training pilots on Vampire, Meteor and Lightning jet aircraft.

After finally resigning his commission, he brought his family to Australia in 1959. As Beverley puts it: "We pored through an atlas in London looking for the best place to bring up our four boys, and we decided Australia was it."

Sharp bought The Henley South Hotel in South Australia and spent four years there until he and Beverley, caravanning to Cairns, were entranced by Sydney's Pittwater. He moved the family to Newport, in a house next door to the Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club, and set up business locally as a glass merchant.

He was to spend the next 30 years as a keen and popular member of the yacht club, winning many championships in several different yachts, from the Diamond class to Compass 29 and Catalina 30s.

Beverley says his crewmen nicknamed him "Araldite" because they couldn't pry him loose for a turn at the tiller.

It was the warmer weather that enticed him and Beverley to Tweed Heads in 1993, and Sharp was active in the Currumbin-Palm Beach RSL sub-branch and club across the Queensland border. Many of its members joined family and friends in a funeral service at Tweed Heads to hear a moving eulogy by Beverley, his wife of 60 years.

She recalled Winston Churchill's memorable phrase about the Battle of Britain: "Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed by so many to so few." "Denny," she said, "was one of those few."

Denis John Sharp is survived by Beverley and their four sons, Denis, Rodney, Geoffrey and Gary. Friends and family are planning a further memorial service for Sharp at his beloved Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club on February 8. His sons and grandchildren will join former crewmen on board a yacht, to scatter his ashes in Pittwater.

In late 2009 I was fortunate to make contact with Dale Hartle. Dale is Denis Sharp's niece and she has painstakingly collated her family tree over the last few years, and this has led to her publishing a wonderful website showing the family's history. Included within these pages is the story of her Uncle Denis. I was able to supply Dale with some information about Denny Sharp's time in Burma and send over (to New Zealand) some of the war diaries containing entries about his involvement with the Chindits of 1943. Here are links to the website and the family story of Squadron Leader Denis Sharp.

http://www.webgirl.co.nz/SharpHealy/dennissharp.html

http://www.webgirl.co.nz/SharpHealy/dennissharp1.html

The link below opens a page showing a personal letter Denis sent home to his own mother in March 1942.

http://www.webgirl.co.nz/SharpHealy/files/LetterFromDennis1942.pdf

I'd like to take this opportunity to thank Dale and her family for all their help and support over the last few years and for allowing me to include family photographs and information within this biography.

I will end this story with Brigadier Wingate's own personal view about the calibre of his RAF detachment in 1943 and his views on their involvement with Air Supply that year.

"The most important thing to note is that SD (Supply Drop) was a brilliant and unexpected success in 1943. All kinds of gloomy prophesies had been made by the the experts. None was fulfilled.

The RAF officers and men provided were of the highest quality. The course of this particular operation did not afford them nearly enough scope to learn as was first hoped, nevertheless they were of great value to the Columns. It is essential to have RAF personnel with Long Range Penetration columns, as they afford the unit; continual air co-operation with rear base, vital air intelligence and the exploitation for calling in strategic bombing raids etc. on previously unknown enemy positions."

http://www.webgirl.co.nz/SharpHealy/dennissharp.html

http://www.webgirl.co.nz/SharpHealy/dennissharp1.html

The link below opens a page showing a personal letter Denis sent home to his own mother in March 1942.

http://www.webgirl.co.nz/SharpHealy/files/LetterFromDennis1942.pdf

I'd like to take this opportunity to thank Dale and her family for all their help and support over the last few years and for allowing me to include family photographs and information within this biography.

I will end this story with Brigadier Wingate's own personal view about the calibre of his RAF detachment in 1943 and his views on their involvement with Air Supply that year.

"The most important thing to note is that SD (Supply Drop) was a brilliant and unexpected success in 1943. All kinds of gloomy prophesies had been made by the the experts. None was fulfilled.

The RAF officers and men provided were of the highest quality. The course of this particular operation did not afford them nearly enough scope to learn as was first hoped, nevertheless they were of great value to the Columns. It is essential to have RAF personnel with Long Range Penetration columns, as they afford the unit; continual air co-operation with rear base, vital air intelligence and the exploitation for calling in strategic bombing raids etc. on previously unknown enemy positions."

Update 20/02/2020.

From the archive of the Air Force Museum of New Zealand. The photograph featured below is said to be of Pilots from No. 486 Squadron watching a demonstration with model aircraft. The names handwritten on the reverse are, L-R: Bush, Marshall, unknown, Anderson, John Clouston, Wilf Clouston, Sharp, Dobbyn, unknown. It did not take much working out that the Sharp in question was our very own Denis J.T. Sharp DFC.

From the archive of the Air Force Museum of New Zealand. The photograph featured below is said to be of Pilots from No. 486 Squadron watching a demonstration with model aircraft. The names handwritten on the reverse are, L-R: Bush, Marshall, unknown, Anderson, John Clouston, Wilf Clouston, Sharp, Dobbyn, unknown. It did not take much working out that the Sharp in question was our very own Denis J.T. Sharp DFC.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and Dale Hartle 2013.