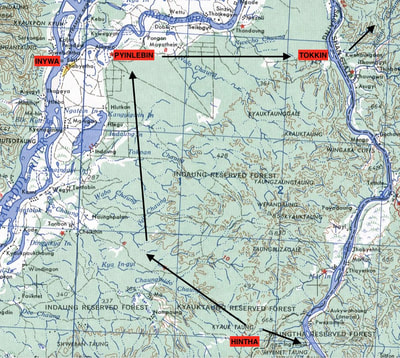

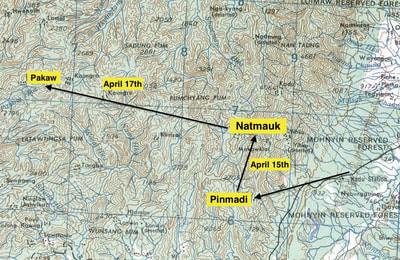

Following 5 Column (their Chindit journey in 1943 through maps).

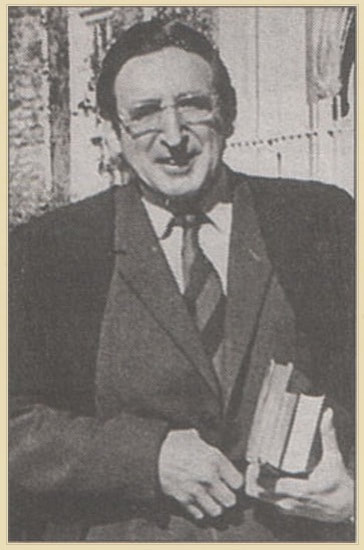

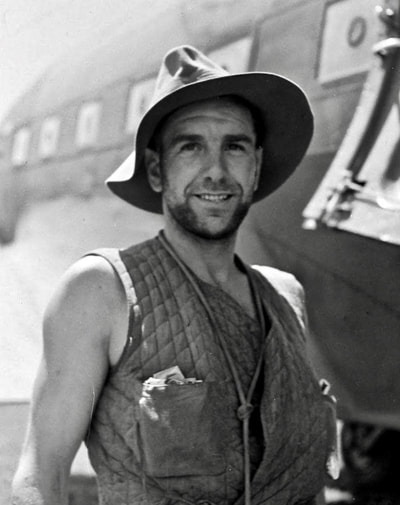

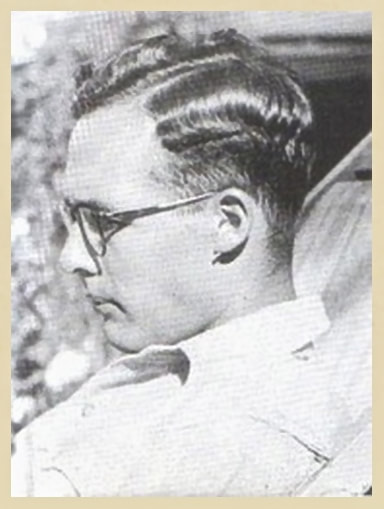

Major Bernard Fergusson.

Major Bernard Fergusson.

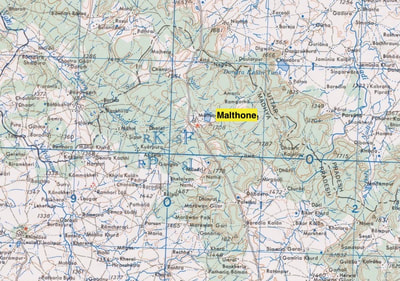

On the 17th October 1943, Major Bernard Fergusson, formerly of the Black Watch Regiment, assumed command of 5 Column at the Chindit camp based at Malthone in the Central Provinces of India. He had replaced Captain Ted Waugh of the King's Regiment who had recently fallen ill and was now deemed unfit to continue with the arduous training regime imposed by Brigadier Wingate.

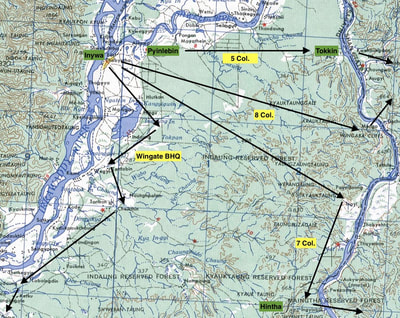

Over the course of my research into the first Chindit expedition, I have often sourced maps on line in order to trace the pathway of various columns during their journeys inside Burma in 1943. Not surprisingly by far the largest collection of these refer to the meanderings of 5 Column.

In early 2018, to commemorate the 75th Anniversary of Operation Longcloth, the Chindit Society decided to publish a week to week diary of Operation Longcloth, written by Tony Redding and supplemented by maps and images relevant to his text. The vast majority of these illustrations were taken from my own collection.

Having gone through the discipline of producing the Longcloth Diary for the Chindit Society's website, I have decided that to reproduce it here, would be the best way of displaying the remainder of the map archive in my possession.

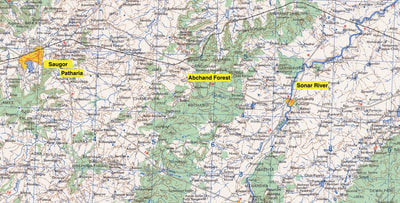

Before beginning the diary, shown in the first gallery are the maps for the various Chindit training areas based in the Central Provinces of India from July through December 1942. Also featured in this group is a photograph of the officers from 5 Column, enjoying their Christmas celebrations at the transitory camp located at Jhansi. The rail station town of Jhansi was where 77th Brigade congregated for their final training exercise in December 1942 and it was from here that the Brigade set off on their long journey to the Assam/Burmese border. As with all the following galleries and images, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Over the course of my research into the first Chindit expedition, I have often sourced maps on line in order to trace the pathway of various columns during their journeys inside Burma in 1943. Not surprisingly by far the largest collection of these refer to the meanderings of 5 Column.

In early 2018, to commemorate the 75th Anniversary of Operation Longcloth, the Chindit Society decided to publish a week to week diary of Operation Longcloth, written by Tony Redding and supplemented by maps and images relevant to his text. The vast majority of these illustrations were taken from my own collection.

Having gone through the discipline of producing the Longcloth Diary for the Chindit Society's website, I have decided that to reproduce it here, would be the best way of displaying the remainder of the map archive in my possession.

Before beginning the diary, shown in the first gallery are the maps for the various Chindit training areas based in the Central Provinces of India from July through December 1942. Also featured in this group is a photograph of the officers from 5 Column, enjoying their Christmas celebrations at the transitory camp located at Jhansi. The rail station town of Jhansi was where 77th Brigade congregated for their final training exercise in December 1942 and it was from here that the Brigade set off on their long journey to the Assam/Burmese border. As with all the following galleries and images, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

OPERATION LONGCLOTH: 75 YEARS ON

Written by Tony Redding, author of War in the Wilderness.

In early 1943 Brigadier (later Major-General) Orde Charles Wingate, DSO, got a chance to prove his Long-Range Penetration (LRP) concept of jungle warfare, based on mobile columns operating behind Japanese lines in North Burma, supplied by air alone and tasked with disrupting the enemy’s supply lines. This was OPERATION LONGCLOTH, a Brigade-strength foray deep into Japanese territory. While achieving little immediate military return, it led to the eventual destruction of Japanese forces in Burma, as it prompted the enemy to the launch the disastrous Imphal/Kohima offensive 12 months later.

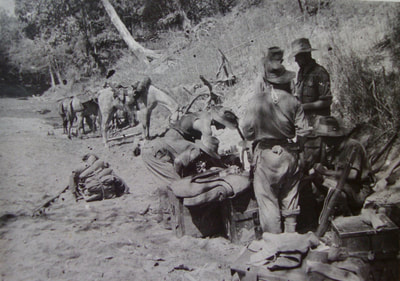

The 3,000 men of 77 Indian Infantry Brigade underwent some of the toughest training ever endured by British troops. When ready, the seven Columns, each of around 400 men accompanied by mules and ponies, began their epic campaign to penetrate Japanese-held territory and attack roads, railways, bridges and supply dumps. They were to suffer terrible casualties, from sickness, savage battles with the enemy, slow starvation and, for some, the horrors of capture by the Japanese.

This year, 2018, is the 75th anniversary of Operation Longcloth. Drawing on War in the Wilderness and, in particular, Bernard Fergusson’s masterly account, Beyond the Chindwin, visitors to this site have an opportunity to follow the 1943 campaign of Wingate’s Chindits as it unfolded. If you read this account, you will be spared none of the terror and suffering. You will also come to appreciate the stoicism, deep courage and extraordinary bonds that developed within the Columns.

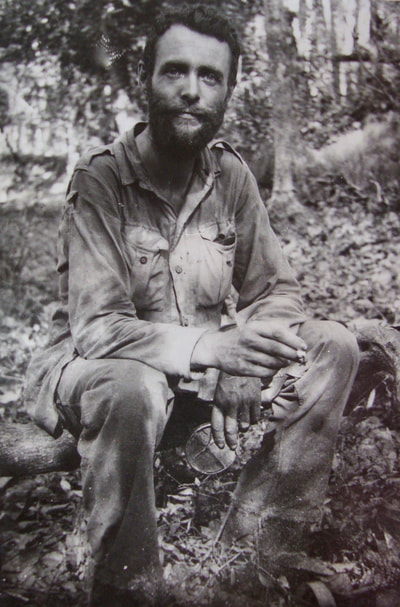

Major (later Brigadier) Bernard Fergusson commanded No. 5 Column during Operation Longcloth. We follow the 1943 campaign largely through his eyes, as described in Beyond the Chindwin.

FEBRUARY 8, 1943:

Major Bernard Fergusson’s No. 5 Column was one of five Columns making up the “main body” of 77 Brigade – No. 2 Group (Northern). They set out for the Chindwin on February 8 1943, with orders to attack the north-south railway and facilities near the town of Nankan, in an area known as “Railway Valley”. There were two additional Columns making up No. 1 Group (Southern). They had orders to cut the railway to the south and divert attention from the main body. This Group set out on the same day. They spent long days marching into position, initially along the Manipur Road. They moved by night, leaving the road free for long motor convoys during the day. They often marched in driving rain, when their heavy packs became even heavier.

Fergusson’s Column was to attack the Bonchaung Bridge and Gorge. He worried about the inevitable decisions on the fate of the sick and wounded who could no longer march: “I gave the officers a talk the afternoon before we entrained. The thing that worried us all most was having to leave behind the wounded, but it was quite obvious that there was nothing else to be done for them and that to linger with them meant risking the success of the show.”

Wingate’s force was inspected by General Wavell. The wider offensive that Operation Longcloth was designed to support had been cancelled, but Wingate succeeded in defending his opportunity to demonstrate the potential of the LRP jungle-fighting concept. In Fergusson’s words: “It was on."

FEBRUARY 12, 1943:

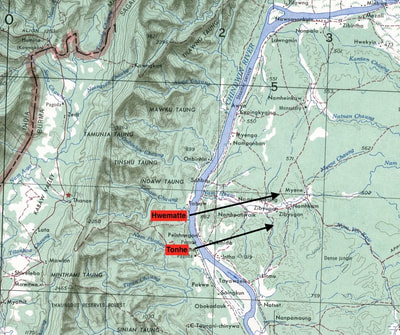

The columns left camp after Wavell’s inspection, still marching on the metalled road, but by day on the two-way stretches. They headed east, Fergusson reaching Lokchau on February 12. Wingate knew he had to conceal the location of the main river crossing. He decided the southern group would cross the Chindwin at Auktaung, acting as a feint, while the main body, the northern group led by Wingate himself, would cross at Tonhe. There was even a “second feint”, with a small party ordered to cross south of Auktaung.

FEBRUARY 14, 1943:

Fergusson’s No. 5 Column was now the tail of the Brigade – the worst position to be in. As the first Chindits crossed the Chindwin, Bernard Fergusson assembled his force and read Orde Wingate’s Order of the Day, which concluded with the words: “Finally, knowing the vanity of Man’s effort and the confusion of his purpose, let us pray that God may accept our services and direct our endeavours, so that when we shall have done all, we may see the fruits of our labours and be satisfied.” Then, with five days’ rations in their packs, they set off for the last stage to the Chindwin. They were climbing the last hill before the river and soon “bumped” the tail of the next column ahead.

The No. 5 Column Commander described the appalling state of the track: “The gradients were steep, but that was not all; for the recent rains had loosened much earth and the track was apt to give way and slither down the hillside.”

On the morning of February 15, Fergusson and two of his officers went ahead, reached a clearing and saw the river below: “… the Chindwin stretched away north and south, separated from us by about five miles of jungle-covered hill, sloping gently down to the river.” Through glasses, they could see the site for the first supply drop, promised for that night. News came that the Tonhe crossing was going badly. Fergusson, at the end of the queue, decided to cross elsewhere, at a point three miles upstream, then march independently to the drop zone. If things didn’t work out, he would have time to return to Tonhe when, hopefully, the muddle would have been sorted out.

No. 5 Column cut through an overgrown track, reached a deserted village (Hwematte) and surveyed the Chindwin: “The banks were high, the river about four hundred yards wide where I stood but a good deal wider both above and below. It reminded me of the Thames at Cliveden.”

They hired a passing small native boat. Meanwhile, Fergusson took a closer look: “I … tried to see it as a crossing place. The near bank was all right; there was a little track down which mules could be got, and a good beach, and a patch of deep water near the edge into which the mules could be shoved (for they like a gradual immersion no more than I do). But the far side was tricky: although there was a beach, it looked muddy, and was backed by steep banks. I resolved to go across and have a look.”

The Column Commander crossed in the small native boat. He found the far bank less muddy than feared, but the steep banks would be challenging. The best hope was to focus on where a stream entered the river. The banks here were less steep. They would cross that night, 15/16 February.

Animal Transport Officer Bill Smyly stared at the river: “I didn’t really know how to get my mules across. We put canoes out in front, tied some mules together in a line and set out. It is impossible to drive mules across a river. They simply turn around and come back to the near bank. They have to be led across to the other side.” The canoe strategy was Fergusson’s idea.

The Chindwin was formidable. Alex Gibson, a Cypher Officer with Major Michael Calvert’s No. 3 Column: “Confusion reigned in the darkness. There was a very strong current and even the best swimmers had so far failed to get a rope across to the opposite bank. This was essential, as none of our Gurkhas could swim.” During the following day, Gibson, an accomplished swimmer, went out and back three times.

Fergusson had nothing but praise for the water skills of the Karens of The Burma Rifles: “Their prowess in the water has to be seen to be believed. They would build boats from bamboo and ground sheets in a few minutes.” They crossed the Rubicon.

Written by Tony Redding, author of War in the Wilderness.

In early 1943 Brigadier (later Major-General) Orde Charles Wingate, DSO, got a chance to prove his Long-Range Penetration (LRP) concept of jungle warfare, based on mobile columns operating behind Japanese lines in North Burma, supplied by air alone and tasked with disrupting the enemy’s supply lines. This was OPERATION LONGCLOTH, a Brigade-strength foray deep into Japanese territory. While achieving little immediate military return, it led to the eventual destruction of Japanese forces in Burma, as it prompted the enemy to the launch the disastrous Imphal/Kohima offensive 12 months later.

The 3,000 men of 77 Indian Infantry Brigade underwent some of the toughest training ever endured by British troops. When ready, the seven Columns, each of around 400 men accompanied by mules and ponies, began their epic campaign to penetrate Japanese-held territory and attack roads, railways, bridges and supply dumps. They were to suffer terrible casualties, from sickness, savage battles with the enemy, slow starvation and, for some, the horrors of capture by the Japanese.

This year, 2018, is the 75th anniversary of Operation Longcloth. Drawing on War in the Wilderness and, in particular, Bernard Fergusson’s masterly account, Beyond the Chindwin, visitors to this site have an opportunity to follow the 1943 campaign of Wingate’s Chindits as it unfolded. If you read this account, you will be spared none of the terror and suffering. You will also come to appreciate the stoicism, deep courage and extraordinary bonds that developed within the Columns.

Major (later Brigadier) Bernard Fergusson commanded No. 5 Column during Operation Longcloth. We follow the 1943 campaign largely through his eyes, as described in Beyond the Chindwin.

FEBRUARY 8, 1943:

Major Bernard Fergusson’s No. 5 Column was one of five Columns making up the “main body” of 77 Brigade – No. 2 Group (Northern). They set out for the Chindwin on February 8 1943, with orders to attack the north-south railway and facilities near the town of Nankan, in an area known as “Railway Valley”. There were two additional Columns making up No. 1 Group (Southern). They had orders to cut the railway to the south and divert attention from the main body. This Group set out on the same day. They spent long days marching into position, initially along the Manipur Road. They moved by night, leaving the road free for long motor convoys during the day. They often marched in driving rain, when their heavy packs became even heavier.

Fergusson’s Column was to attack the Bonchaung Bridge and Gorge. He worried about the inevitable decisions on the fate of the sick and wounded who could no longer march: “I gave the officers a talk the afternoon before we entrained. The thing that worried us all most was having to leave behind the wounded, but it was quite obvious that there was nothing else to be done for them and that to linger with them meant risking the success of the show.”

Wingate’s force was inspected by General Wavell. The wider offensive that Operation Longcloth was designed to support had been cancelled, but Wingate succeeded in defending his opportunity to demonstrate the potential of the LRP jungle-fighting concept. In Fergusson’s words: “It was on."

FEBRUARY 12, 1943:

The columns left camp after Wavell’s inspection, still marching on the metalled road, but by day on the two-way stretches. They headed east, Fergusson reaching Lokchau on February 12. Wingate knew he had to conceal the location of the main river crossing. He decided the southern group would cross the Chindwin at Auktaung, acting as a feint, while the main body, the northern group led by Wingate himself, would cross at Tonhe. There was even a “second feint”, with a small party ordered to cross south of Auktaung.

FEBRUARY 14, 1943:

Fergusson’s No. 5 Column was now the tail of the Brigade – the worst position to be in. As the first Chindits crossed the Chindwin, Bernard Fergusson assembled his force and read Orde Wingate’s Order of the Day, which concluded with the words: “Finally, knowing the vanity of Man’s effort and the confusion of his purpose, let us pray that God may accept our services and direct our endeavours, so that when we shall have done all, we may see the fruits of our labours and be satisfied.” Then, with five days’ rations in their packs, they set off for the last stage to the Chindwin. They were climbing the last hill before the river and soon “bumped” the tail of the next column ahead.

The No. 5 Column Commander described the appalling state of the track: “The gradients were steep, but that was not all; for the recent rains had loosened much earth and the track was apt to give way and slither down the hillside.”

On the morning of February 15, Fergusson and two of his officers went ahead, reached a clearing and saw the river below: “… the Chindwin stretched away north and south, separated from us by about five miles of jungle-covered hill, sloping gently down to the river.” Through glasses, they could see the site for the first supply drop, promised for that night. News came that the Tonhe crossing was going badly. Fergusson, at the end of the queue, decided to cross elsewhere, at a point three miles upstream, then march independently to the drop zone. If things didn’t work out, he would have time to return to Tonhe when, hopefully, the muddle would have been sorted out.

No. 5 Column cut through an overgrown track, reached a deserted village (Hwematte) and surveyed the Chindwin: “The banks were high, the river about four hundred yards wide where I stood but a good deal wider both above and below. It reminded me of the Thames at Cliveden.”

They hired a passing small native boat. Meanwhile, Fergusson took a closer look: “I … tried to see it as a crossing place. The near bank was all right; there was a little track down which mules could be got, and a good beach, and a patch of deep water near the edge into which the mules could be shoved (for they like a gradual immersion no more than I do). But the far side was tricky: although there was a beach, it looked muddy, and was backed by steep banks. I resolved to go across and have a look.”

The Column Commander crossed in the small native boat. He found the far bank less muddy than feared, but the steep banks would be challenging. The best hope was to focus on where a stream entered the river. The banks here were less steep. They would cross that night, 15/16 February.

Animal Transport Officer Bill Smyly stared at the river: “I didn’t really know how to get my mules across. We put canoes out in front, tied some mules together in a line and set out. It is impossible to drive mules across a river. They simply turn around and come back to the near bank. They have to be led across to the other side.” The canoe strategy was Fergusson’s idea.

The Chindwin was formidable. Alex Gibson, a Cypher Officer with Major Michael Calvert’s No. 3 Column: “Confusion reigned in the darkness. There was a very strong current and even the best swimmers had so far failed to get a rope across to the opposite bank. This was essential, as none of our Gurkhas could swim.” During the following day, Gibson, an accomplished swimmer, went out and back three times.

Fergusson had nothing but praise for the water skills of the Karens of The Burma Rifles: “Their prowess in the water has to be seen to be believed. They would build boats from bamboo and ground sheets in a few minutes.” They crossed the Rubicon.

FEBRUARY 16, 1943:

Major Fergusson’s No.5 Column had struggled to cross the Chindwin – it was much wider than any previous river crossed. Once a light line was across and secured, a heavy line was pulled across, but it was impossible to eliminate the sag in the heavy rope, which fouled the bottom. The Column Commander wrote: “That began a weary cycle of twitching it, diving for it, dredging for it and then starting again.”

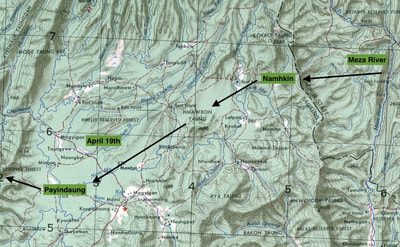

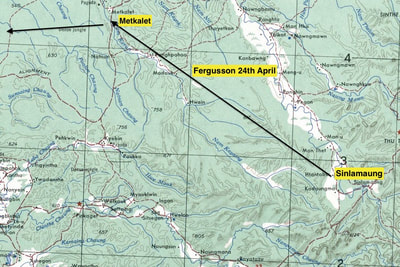

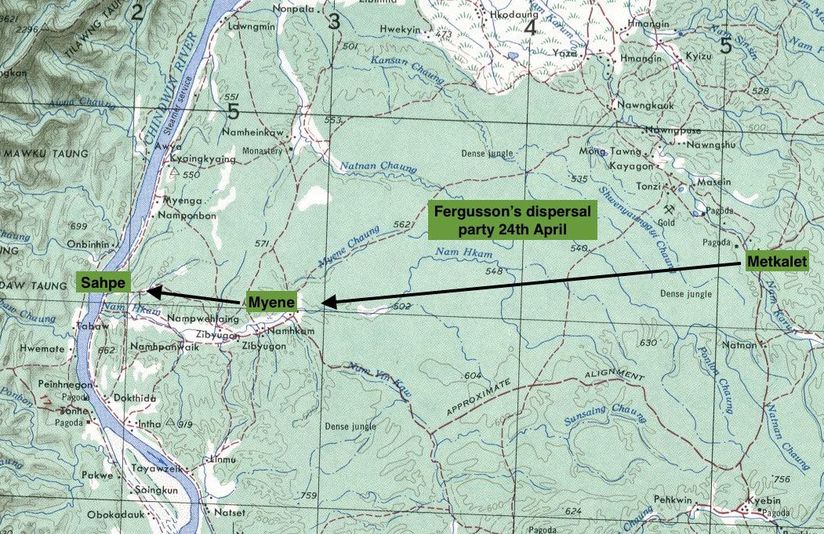

Once across, Fergusson’s men and their animals continued to march by night, resting up in dense jungle during the daylight hours. Some of the men had trouble with “night blindness”. The Column Commander was wary. “I never bivouacked within 500 yards of a track.” They met up with other Columns at the village of Myene. The big air drop was successful and the men of No.5 Column stowed six days’ rations in their packs. They marched through teak forest towards the next objective, the village of Metkalet. Mike Calvert, No.3 Column’s Commander, had reported a Japanese force of 200 at this location. No.5 Column had a chance to join this action. Fergusson wrote: “Besides the chance of complete surprise, we had all of us realised that the one thing needful to complete our training was a successful early brush.”

However, bad country got in the way of Fergusson’s plans. The maps promised a free run to Metkalet but No.5 Column found its way blocked: “…we came suddenly to a long narrow marsh of oozy black mud, covered with surface water…”. The only option was to build a causeway. In the next 24 hours they built 14 more causeways and were still struggling. Fergusson then received a Brigade signal: “Suspect you are on wild-goose chase, stop on to Tonmakeng.” Frustratingly, Fergusson found Metkalet abandoned by the Japanese. They made for Tonmakeng, a village close to the selected Brigade bivouac. Wingate had requested another big supply drop and Fergusson got the job of receiving it. The supplies included free-dropped corn for the mules. During this operation, a No.5 Column sentry was found asleep. Major Fergusson gave him the choice of walking back to India or taking a flogging. Not surprisingly, he accepted the latter. CSM Cairns administered the punishment with a makeshift cat-o-nine-tails fashioned from parachute cord. The Column Commander reflected on the sleeping sentry: “…he had all our lives in his hands, and put them in pawn.”

Commenting further on this incident, Fergusson wrote: “How do you punish a man for an offence like that, in circumstances like these? Shooting, thank goodness, is no longer the recognised punishment; to hold a field general court martial and give him penal servitude hardly helps towards making him a useful soldier during the next few months; detention, loss of pay, stoppage of leave, confinement to – Column? – none of these seem applicable.”

There was tension among the men. The jungle was rich in hazards, from falling trees and rotten branches to an impressive array of stinging and biting creatures, from ants and flies to caterpillars, ticks, scorpions and leeches. They loathed the ferocious red ants populating dry teak jungle. Fergusson said they had “the most vicious sting imaginable. They would stand on their heads and burrow into you as if with a pneumatic drill.” The Chindits learnt to remove leeches with salt or a burning cigarette. One particular worry was the possibility of an intrepid leech finding its way into the most private of private parts.

FEBRUARY 23, 1943:

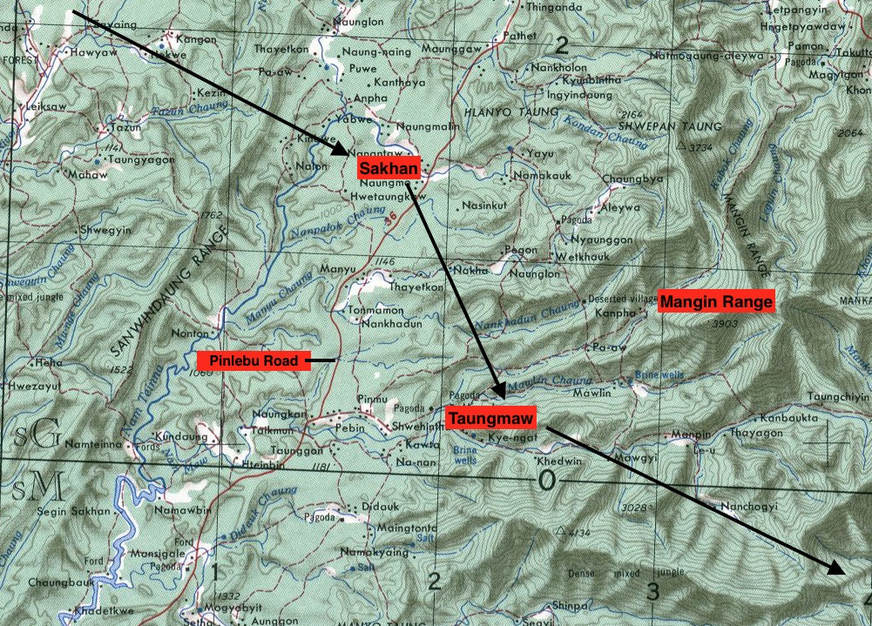

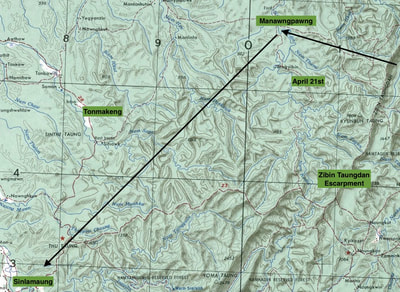

The country up ahead was thought unsuitable for supply drops, so Wingate called for a huge drop at Tonmakeng. Fergusson ran the drop. On February 23 Wingate issued his orders for the next phase. The Columns would enter the Mu Valley and turn south for Pinlebu. An attempt to tackle a Japanese garrison at Sinlamaung village proved abortive, as the enemy left it before it could be reached. The attacking force returned to the main body on February 26.

Wingate then gave new orders to the Column Commanders. Fergusson’s No.5 Column left at 03.00 the next morning. Once again, the Columns repeatedly bumped each other, largely because the lead Column – responsible for all the pioneering – made slow progress. On occasion, being lead column was worse than being tail column.

Wingate was as impatient as ever. During No.5 Column’s approach to the Pinlebu road, he gave Fergusson a personal demonstration of how to cut through dense jungle more efficiently. Rather than using two or three “slashers” in front, the Brigadier’s method employed an entire platoon. The leaders cut a narrow way, just wide enough for themselves, and the remaining slashers steadily widened it as they progressed, until it reached the 5ft required to allow laden mules to pass.

Wingate had ordered Fergusson to leave the Brigade, move independently to his main target, Bonchaung, and bring the gorge down onto the line. Afterwards, he was to cross the Irrawaddy, move down towards Mogok, where the Brigade would concentrate. Meanwhile, No.4 Column would attack the Japanese garrison at Pinbon, so allowing Brigade headquarters, 2 Group and Nos. 7 and 8 Columns to move rapidly south down to Pinlebu road. They would soon see action.

Major Fergusson’s No.5 Column had struggled to cross the Chindwin – it was much wider than any previous river crossed. Once a light line was across and secured, a heavy line was pulled across, but it was impossible to eliminate the sag in the heavy rope, which fouled the bottom. The Column Commander wrote: “That began a weary cycle of twitching it, diving for it, dredging for it and then starting again.”

Once across, Fergusson’s men and their animals continued to march by night, resting up in dense jungle during the daylight hours. Some of the men had trouble with “night blindness”. The Column Commander was wary. “I never bivouacked within 500 yards of a track.” They met up with other Columns at the village of Myene. The big air drop was successful and the men of No.5 Column stowed six days’ rations in their packs. They marched through teak forest towards the next objective, the village of Metkalet. Mike Calvert, No.3 Column’s Commander, had reported a Japanese force of 200 at this location. No.5 Column had a chance to join this action. Fergusson wrote: “Besides the chance of complete surprise, we had all of us realised that the one thing needful to complete our training was a successful early brush.”

However, bad country got in the way of Fergusson’s plans. The maps promised a free run to Metkalet but No.5 Column found its way blocked: “…we came suddenly to a long narrow marsh of oozy black mud, covered with surface water…”. The only option was to build a causeway. In the next 24 hours they built 14 more causeways and were still struggling. Fergusson then received a Brigade signal: “Suspect you are on wild-goose chase, stop on to Tonmakeng.” Frustratingly, Fergusson found Metkalet abandoned by the Japanese. They made for Tonmakeng, a village close to the selected Brigade bivouac. Wingate had requested another big supply drop and Fergusson got the job of receiving it. The supplies included free-dropped corn for the mules. During this operation, a No.5 Column sentry was found asleep. Major Fergusson gave him the choice of walking back to India or taking a flogging. Not surprisingly, he accepted the latter. CSM Cairns administered the punishment with a makeshift cat-o-nine-tails fashioned from parachute cord. The Column Commander reflected on the sleeping sentry: “…he had all our lives in his hands, and put them in pawn.”

Commenting further on this incident, Fergusson wrote: “How do you punish a man for an offence like that, in circumstances like these? Shooting, thank goodness, is no longer the recognised punishment; to hold a field general court martial and give him penal servitude hardly helps towards making him a useful soldier during the next few months; detention, loss of pay, stoppage of leave, confinement to – Column? – none of these seem applicable.”

There was tension among the men. The jungle was rich in hazards, from falling trees and rotten branches to an impressive array of stinging and biting creatures, from ants and flies to caterpillars, ticks, scorpions and leeches. They loathed the ferocious red ants populating dry teak jungle. Fergusson said they had “the most vicious sting imaginable. They would stand on their heads and burrow into you as if with a pneumatic drill.” The Chindits learnt to remove leeches with salt or a burning cigarette. One particular worry was the possibility of an intrepid leech finding its way into the most private of private parts.

FEBRUARY 23, 1943:

The country up ahead was thought unsuitable for supply drops, so Wingate called for a huge drop at Tonmakeng. Fergusson ran the drop. On February 23 Wingate issued his orders for the next phase. The Columns would enter the Mu Valley and turn south for Pinlebu. An attempt to tackle a Japanese garrison at Sinlamaung village proved abortive, as the enemy left it before it could be reached. The attacking force returned to the main body on February 26.

Wingate then gave new orders to the Column Commanders. Fergusson’s No.5 Column left at 03.00 the next morning. Once again, the Columns repeatedly bumped each other, largely because the lead Column – responsible for all the pioneering – made slow progress. On occasion, being lead column was worse than being tail column.

Wingate was as impatient as ever. During No.5 Column’s approach to the Pinlebu road, he gave Fergusson a personal demonstration of how to cut through dense jungle more efficiently. Rather than using two or three “slashers” in front, the Brigadier’s method employed an entire platoon. The leaders cut a narrow way, just wide enough for themselves, and the remaining slashers steadily widened it as they progressed, until it reached the 5ft required to allow laden mules to pass.

Wingate had ordered Fergusson to leave the Brigade, move independently to his main target, Bonchaung, and bring the gorge down onto the line. Afterwards, he was to cross the Irrawaddy, move down towards Mogok, where the Brigade would concentrate. Meanwhile, No.4 Column would attack the Japanese garrison at Pinbon, so allowing Brigade headquarters, 2 Group and Nos. 7 and 8 Columns to move rapidly south down to Pinlebu road. They would soon see action.

MARCH 1, 1943:

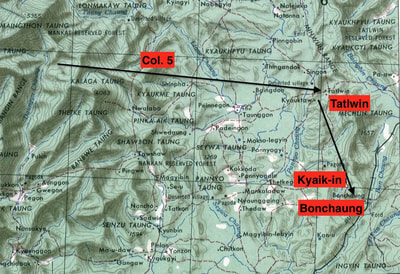

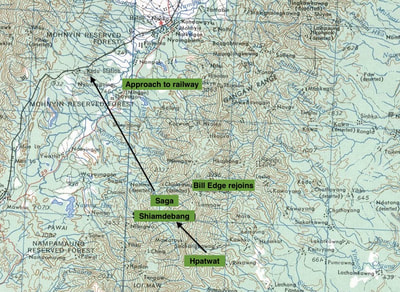

No. 5 Column moved north during the morning of March 1st, 1943, through impressive country. They were on the edge of an escarpment and a broad valley opened before them, with the high hills of the Mangin Range opposite. Beyond was the Meza Valley and, beyond that, the railway and important communications hub of Indaw. They would then face the formidable Gangaw Hills and, finally, the Irrawaddy.

This area, the Mu Valley, was easily defended as it was separated from the railway by hills offering few passes. There was also a good motorable road from Pinlebu in the south to Mansi in the north. Both were believed to hold Japanese forces, as were Pinbon and Thayethon.

As Bernard Fergusson’s column descended into the valley, Orde Wingate arrived and gave his Column Commander further orders. Fergusson was given free rein to strike out across country – to his intense relief. He had had enough of “bumping” other columns and “constant liability to thunderous reproaches from a great leader with unattainable demands …”

Once again, the going was bad – not enough jungle cover on the higher ground and, lower down, almost impenetrable country following the Chaunggyi stream. Villagers warned of Japanese troops in the area (although their information lacked precision). When they bivouacked for the night, other columns arrived and settled in nearby. Fergusson, as ever, was anxious to get on. They moved off at first light and soon reached the motorable road running east-west across their line of march. This appeared on maps as a track – the enemy had been busy. There were the unmistakable footprints of Japanese soldiers wearing rubber shoes.

Fergusson blocked the road in each direction and began to cross – always an anxious time: “…a column takes 10 minutes to pass a point and is a thousand yards long.” His precautions proved wise. The column rear bumped into coolies carrying kit for a Japanese patrol just 10 minutes ahead of them. The coolies were bribed to say nothing.

Fergusson then found himself between a rock and a hard place. The jungle grew even thicker and No. 5 Column’s lead ahead of the Brigade was dwindling. Even worse, Wingate turned up again and laid into the Column Commander, urging faster progress, using his patent method of cutting through dense jungle.

The Column marched on and soon burst through to the main road. This time, Bernard Fergusson was determined to get well clear of Brigade. They took a chance and used the road. “The sensation of walking along a main and motorable road, for the first time since the Kabaw Valley, was a strange one. Men with anti-vehicle grenades led the column and brought up the rear, for the possibility of meeting truckloads of infantry, or even armoured cars, was by no means remote … It was a solemn thought to think that the road ran ahead of us straight into Pinlebu, with nothing on it between us and the enemy.”

Fergusson then received a shock: he bumped into the other Columns; they had moved ahead of him! They had avoided the difficult jungle by the simple device of using the road earlier on. Wingate then appeared and repositioned No. 5 Column as lead. “I was not to halt until after dark and then only for four hours; thereafter not again until I had reached the point on the main road where he had told me to turn off to the eastward …”

Torrential rain began at four in the afternoon, soaking the men in 30 seconds: “Even on the road it was heavy going and the mules slithered and slipped in all directions.” They halted after dark near Sakhan village, the rain then slackened off and they managed to cook. When they moved off at 11 pm, a trying day ended badly for Major Fergusson: “… the marching was thoroughly unpleasant … I took a nasty fall into a ditch and twisted my kneecap so badly that it bothered me for the rest of the campaign.”

MARCH 3, 1943:

At around 4 am on March 3rd, No. 5 Column left the main road and entered the Nam Maw hills, known as “Happy Valley”. They had trouble finding a place to bivouac as the whole area was paddy. Eventually, they found a small wood. It was “thoroughly unsound” but, again, they took a chance: “So ended about the nastiest march of my life”, wrote Fergusson.

The Column’s rations would run out next evening. Fergusson could call in another air drop but the delay could lead to his force being intercepted before reaching the railway. The Column Commander preferred to use No. 5’s silver rupees, to buy rice from the villagers of Taungmaw, together with unhusked paddy for the mules. The men filled their spare socks with rice. Fergusson was warned about the state of the track ahead yet neglected to ask for a guide. The going soon became impossible for animals. They retraced their steps and took a better route, this time with the help of a guide. There followed a good day’s marching in beautiful country and it was at that point that it was dubbed “Happy Valley”. At the valley’s end was the Mankat Pass, leading into the Taung Chaung Valley. Their luck held: it was unoccupied by the Japanese, despite its obvious attractions to infiltrators. Ahead was the flat basin of the Taung Chaung – a mix of jungle and paddy. Beyond were the low hills leading to the railway and No. 5 Column’s main target. Fergusson noted: “Six miles to our left, but hidden by the broad shoulder of a hill which intervened, was Banmauk, with its reputedly formidable garrison.”

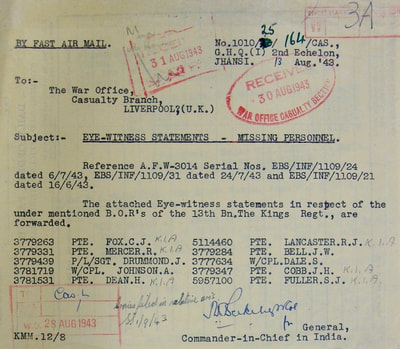

Fergusson lost a man in Happy Valley – his first casualty. He suspected that he may have fallen asleep during a halt. “We hoped he might catch us up, but he never did, and nothing has been heard of him since.” (The soldier in question was most probably Pte. Charles James Fox, who is recorded as having died on the 1st March 1943 and has no known grave in Burma).

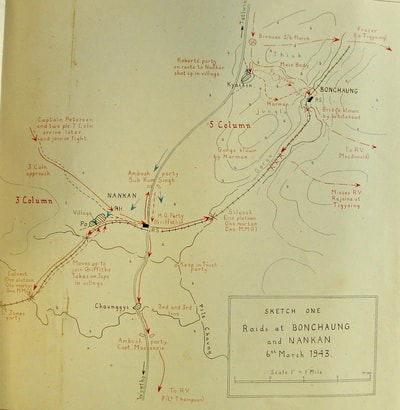

They covered 22 miles on March 4 and 18 on the next. Fergusson was told by a friendly priest that there was a small, 20-strong detachment of Japanese at Nankan, the next station south of Bonchaung, and another post at Meza Station, this of unknown strength. During the night of March 5/6 they bivouacked just three miles from Bonchaung Station. They had been across the Chindwin for 18 days and had yet to see a single Japanese soldier. The Column Commander had made his attack plan. His men assumed they would attack by night, but they were wrong: “To blow the bridge and gorge by daylight would be far quicker and better than to do it by night; and although never until today had it occurred to me that a daylight operation would be possible, the unexpected scarcity of Japs in the area put a new complexion on it.”

He knew that blowing the bridge and gorge would be much easier than getting out of the area afterwards and crossing the Irrawaddy without being hit by the Japanese. Fergusson wrote: “Even though in all probability he was not expecting us to cross the Irrawaddy, but to withdraw to India, he would quickly become aware of his mistake; and, with the new network of motor-roads which he had been building everywhere, it would not take him long to switch his troops from one area to another as information about our movements reached him.”

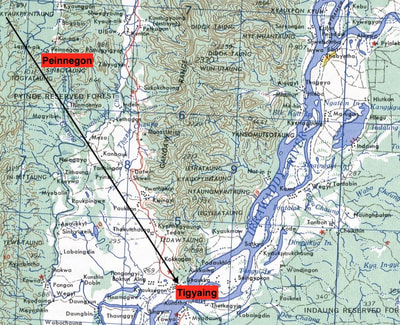

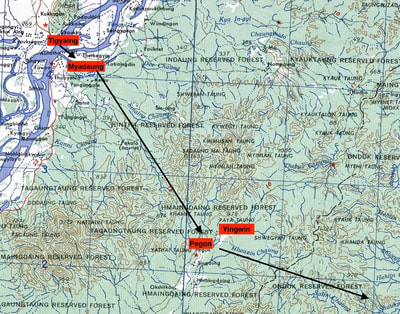

This shaped Fergusson’s thinking on the greatest challenge, a successful crossing of the immense width of the Irrawaddy. It would take several nights to cross in penny packets in their modest collection of rubber boats. Instead, he would make for the ferry town of Tigyaing, to the south east, “and try to cross in one bold stroke. It was some 20 miles from Katha and still farther from Wuntho, the two garrisons most likely to come out and hunt us.” The aim was to cross at Tigyaing Steamer Station on around March 9.

No. 5 Column prepared a force to blow the Gorge, two miles south of Bonchaung Station. This consisted of half the Commando Platoon, under Lieutenant Jim Harman, escorted by a platoon under Lieutenant Philip Stibbé. Another fighting group was to make for Nankan and keep the small enemy force there fully occupied. A third party would make for the gorge, while a fourth – the main body – would take the track leading to Bonchaung Station. They would destroy the three-span girder bridge at the station’s southern end. The rendezvous for everyone was a small stream in the Kunbaung Valley, about 25 miles away, up until noon on March 8. Everyone tried to sleep, putting the trials ahead out of their minds.

No. 5 Column moved north during the morning of March 1st, 1943, through impressive country. They were on the edge of an escarpment and a broad valley opened before them, with the high hills of the Mangin Range opposite. Beyond was the Meza Valley and, beyond that, the railway and important communications hub of Indaw. They would then face the formidable Gangaw Hills and, finally, the Irrawaddy.

This area, the Mu Valley, was easily defended as it was separated from the railway by hills offering few passes. There was also a good motorable road from Pinlebu in the south to Mansi in the north. Both were believed to hold Japanese forces, as were Pinbon and Thayethon.

As Bernard Fergusson’s column descended into the valley, Orde Wingate arrived and gave his Column Commander further orders. Fergusson was given free rein to strike out across country – to his intense relief. He had had enough of “bumping” other columns and “constant liability to thunderous reproaches from a great leader with unattainable demands …”

Once again, the going was bad – not enough jungle cover on the higher ground and, lower down, almost impenetrable country following the Chaunggyi stream. Villagers warned of Japanese troops in the area (although their information lacked precision). When they bivouacked for the night, other columns arrived and settled in nearby. Fergusson, as ever, was anxious to get on. They moved off at first light and soon reached the motorable road running east-west across their line of march. This appeared on maps as a track – the enemy had been busy. There were the unmistakable footprints of Japanese soldiers wearing rubber shoes.

Fergusson blocked the road in each direction and began to cross – always an anxious time: “…a column takes 10 minutes to pass a point and is a thousand yards long.” His precautions proved wise. The column rear bumped into coolies carrying kit for a Japanese patrol just 10 minutes ahead of them. The coolies were bribed to say nothing.

Fergusson then found himself between a rock and a hard place. The jungle grew even thicker and No. 5 Column’s lead ahead of the Brigade was dwindling. Even worse, Wingate turned up again and laid into the Column Commander, urging faster progress, using his patent method of cutting through dense jungle.

The Column marched on and soon burst through to the main road. This time, Bernard Fergusson was determined to get well clear of Brigade. They took a chance and used the road. “The sensation of walking along a main and motorable road, for the first time since the Kabaw Valley, was a strange one. Men with anti-vehicle grenades led the column and brought up the rear, for the possibility of meeting truckloads of infantry, or even armoured cars, was by no means remote … It was a solemn thought to think that the road ran ahead of us straight into Pinlebu, with nothing on it between us and the enemy.”

Fergusson then received a shock: he bumped into the other Columns; they had moved ahead of him! They had avoided the difficult jungle by the simple device of using the road earlier on. Wingate then appeared and repositioned No. 5 Column as lead. “I was not to halt until after dark and then only for four hours; thereafter not again until I had reached the point on the main road where he had told me to turn off to the eastward …”

Torrential rain began at four in the afternoon, soaking the men in 30 seconds: “Even on the road it was heavy going and the mules slithered and slipped in all directions.” They halted after dark near Sakhan village, the rain then slackened off and they managed to cook. When they moved off at 11 pm, a trying day ended badly for Major Fergusson: “… the marching was thoroughly unpleasant … I took a nasty fall into a ditch and twisted my kneecap so badly that it bothered me for the rest of the campaign.”

MARCH 3, 1943:

At around 4 am on March 3rd, No. 5 Column left the main road and entered the Nam Maw hills, known as “Happy Valley”. They had trouble finding a place to bivouac as the whole area was paddy. Eventually, they found a small wood. It was “thoroughly unsound” but, again, they took a chance: “So ended about the nastiest march of my life”, wrote Fergusson.

The Column’s rations would run out next evening. Fergusson could call in another air drop but the delay could lead to his force being intercepted before reaching the railway. The Column Commander preferred to use No. 5’s silver rupees, to buy rice from the villagers of Taungmaw, together with unhusked paddy for the mules. The men filled their spare socks with rice. Fergusson was warned about the state of the track ahead yet neglected to ask for a guide. The going soon became impossible for animals. They retraced their steps and took a better route, this time with the help of a guide. There followed a good day’s marching in beautiful country and it was at that point that it was dubbed “Happy Valley”. At the valley’s end was the Mankat Pass, leading into the Taung Chaung Valley. Their luck held: it was unoccupied by the Japanese, despite its obvious attractions to infiltrators. Ahead was the flat basin of the Taung Chaung – a mix of jungle and paddy. Beyond were the low hills leading to the railway and No. 5 Column’s main target. Fergusson noted: “Six miles to our left, but hidden by the broad shoulder of a hill which intervened, was Banmauk, with its reputedly formidable garrison.”

Fergusson lost a man in Happy Valley – his first casualty. He suspected that he may have fallen asleep during a halt. “We hoped he might catch us up, but he never did, and nothing has been heard of him since.” (The soldier in question was most probably Pte. Charles James Fox, who is recorded as having died on the 1st March 1943 and has no known grave in Burma).

They covered 22 miles on March 4 and 18 on the next. Fergusson was told by a friendly priest that there was a small, 20-strong detachment of Japanese at Nankan, the next station south of Bonchaung, and another post at Meza Station, this of unknown strength. During the night of March 5/6 they bivouacked just three miles from Bonchaung Station. They had been across the Chindwin for 18 days and had yet to see a single Japanese soldier. The Column Commander had made his attack plan. His men assumed they would attack by night, but they were wrong: “To blow the bridge and gorge by daylight would be far quicker and better than to do it by night; and although never until today had it occurred to me that a daylight operation would be possible, the unexpected scarcity of Japs in the area put a new complexion on it.”

He knew that blowing the bridge and gorge would be much easier than getting out of the area afterwards and crossing the Irrawaddy without being hit by the Japanese. Fergusson wrote: “Even though in all probability he was not expecting us to cross the Irrawaddy, but to withdraw to India, he would quickly become aware of his mistake; and, with the new network of motor-roads which he had been building everywhere, it would not take him long to switch his troops from one area to another as information about our movements reached him.”

This shaped Fergusson’s thinking on the greatest challenge, a successful crossing of the immense width of the Irrawaddy. It would take several nights to cross in penny packets in their modest collection of rubber boats. Instead, he would make for the ferry town of Tigyaing, to the south east, “and try to cross in one bold stroke. It was some 20 miles from Katha and still farther from Wuntho, the two garrisons most likely to come out and hunt us.” The aim was to cross at Tigyaing Steamer Station on around March 9.

No. 5 Column prepared a force to blow the Gorge, two miles south of Bonchaung Station. This consisted of half the Commando Platoon, under Lieutenant Jim Harman, escorted by a platoon under Lieutenant Philip Stibbé. Another fighting group was to make for Nankan and keep the small enemy force there fully occupied. A third party would make for the gorge, while a fourth – the main body – would take the track leading to Bonchaung Station. They would destroy the three-span girder bridge at the station’s southern end. The rendezvous for everyone was a small stream in the Kunbaung Valley, about 25 miles away, up until noon on March 8. Everyone tried to sleep, putting the trials ahead out of their minds.

MARCH 6, 1943:

On March 6, 1943, No. 5 Column split into its fighting groups and made for the small Japanese garrison at Nankan, the gorge and Bonchaung Station’s bridge. Meanwhile, a Burma Rifles (Burrif) party under Captain John Fraser was briefed to recce the planned Irrawaddy crossing point, the ferry town of Tigyaung, around 35 miles distant.

On that morning, as Fergusson moved off, a runner came in reporting that the Nankan group was engaging Japanese in Kyaik-in village. The gorge party then made straight for the gorge and Fergusson decided that his main body should go straight across country to Bonchaung, while the remaining Rifle Platoon was ordered to back up the group fighting in Nyaik-in. There were casualties on both sides, including Platoon Commander John Kerr, who suffered a leg wound. Fergusson decided to take a look. Kerr told him they had run into a Japanese truck parked in the village. They opened up and killed several of the enemy, sustaining two killed and several wounded themselves. The truck then drove off. At that point Kerr’s men had no idea they were still at risk. A new light machine gun opened fire, hitting Kerr and several others. Later, the Column Commander himself had a close shave: “While he was telling me this, there was a sudden report just behind my ear, and I spun round to find Peter Dorans with a smoking rifle, and one of the two ‘dead’ Japs in the road writhing. He had suddenly flung himself upon his elbow and pointed his rifle at me. Peter shot him again and finally dispatched him.”

Now Fergusson faced his greatest horror: “What to do with the wounded?” Five men were unable to move, including Kerr. He and two others were carried by mule into the village. The remaining two could not be moved. Fergusson told Kerr where they were. There were 16 dead Japanese around and more enemy troops could be expected when the truck driver raised the alarm. With the Rifle Platoons now back, Fergusson headed off but had trouble finding the Bonchaung track. After a hard struggle they arrived, and found the Commando Platoon busily preparing the bridge for demolition. “Hasty” charges were already in place, so they could be blown if the Chindits were disturbed before the main charges were ready.

When the bridge was blown the results were impressive: “The flash illuminated the whole hillside. It showed the men standing tense and waiting, the muleteers with a good grip of their mules; and the brown of the path and the green of the trees preternaturally vivid. Then came the bang. The mules plunged and kicked, the hills for miles around rolled the noise of it about their hollows and flung it to their neighbours … all of us hoped that John Kerr and his little group of abandoned men, whose sacrifice had helped to make it possible, heard it also, and knew that we had accomplished that which we had come so far to do.” Then they heard a second great explosion – the gorge was blown.

On that same day, Major Michael Calvert’s No. 3 Column blew up two large railway bridges (one with a 300 ft span). Calvert called in an air strike against Japanese positions at Wuntho, 10 miles to the south. They then set ambushes and killed many Japanese without loss to themselves. Both No. 3 and No. 5 Columns had mauled the railway.

MARCH 7, 1943:

It was now a question of avoiding trouble and getting to the Irrawaddy as quickly as possible. As they marched, No. 5 Column’s Commander worried about the party that had been dispatched to Nankan. He had expected them back by now. He could only hope this group of around 30 would turn up at the rendezvous.

They halted at noon on March 7 – Fergusson wanted the wireless. He reported the destruction of the bridge and the blown gorge. He also learnt that Captain John Fraser was making good progress towards Tigyaing, the river crossing.

The Column then reached a fordable point on the Meza River, at Peinnegon village. There was smallpox in this village, so the men didn’t linger. They turned south, moving along the east bank of the river. They halted in less than a mile. Fergusson wrote: “… the jungle was exceedingly thick and all of us tired: we had marched 113 miles in seven days and had a considerable emotional strain as well, while our loads weighed an average of 60 lbs.” They stopped for the night at 16.00 and were asleep before dark.

On March 8 a small group was sent on ahead to reach the RV, as it closed at noon and it was possible that the main body wouldn’t get there in time. In fact, the main body stopped before the RV for a meal and, most importantly, a scheduled communication with Brigade. Fergusson received the message that No. 1 (Southern) Group had not been heard from for 10 days, suggesting that crossing the Irrawaddy was hazardous. No. 5 Column was given discretion to cross the Irrawaddy or, instead, base itself in the Gangaw Hills and harass railway repair gangs.

The Southern Group had enjoyed mixed fortunes. No. 1 Column was the first to cut the railway, on March 3 just north of Kyaikthin. However, on the preceding night No. 2 Column fought an action near that village and was dispersed. Fergusson, meanwhile, found the warning message “distinctly unsettling”. He told Brigade he would think on it and respond with a decision in a few hours. As they moved on the Column Commander wrestled with the issues. He had received a favourable report on the prospects for crossing at Tigyaing and the Japanese would be expecting them to start their return to India rather than go further east. On the other hand, crossing the huge river would be tricky and No. 5 Column was still incomplete. There was also the thorny question of how to get back. He did not know that the Northern Group’s No. 4 Column had been ambushed and broken up. This meant that Wingate was left with just four columns under direction, to continue Longcloth.

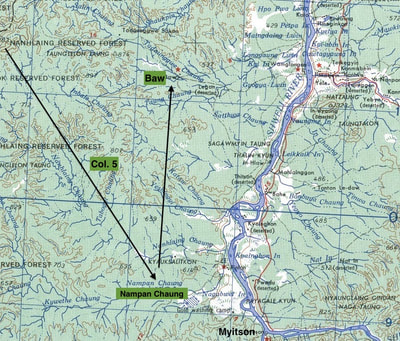

There was no sign of the missing groups – the Nankan and gorge parties. Bernard Fergusson told John Fraser that he’d wait at the RV for another 24 hours. Fraser said there were no Japanese at Tigyaing. Then the Nankan party reached the RV. They had been short-handed following the action involving Kerr and decided not to go on to Nankan. The No. 5 Column Commander signalled that he would attempt the Irrawaddy crossing: “… I proposed to try it and then to march for the Shweli bridge on the road running from the main Burma Road up to Bhamo. If this could be destroyed … the isolation of Myitkyina would be complete …” He hoped to reach this suspension bridge by around March 20.

Where was the gorge party? Fergusson fretted as he attempted to sleep. He was under tremendous pressure. He hoped for a supply drop on March 12 at Pegon village – 20 miles on the other side of the Irrawaddy: “The food problem was rather acute, for it was now 10 days since we started our last five days’ supply, and we were all heartily sick of the rice bought in the Happy Valley. A mule which had been shot in the action at Kyaik-in showed no signs of recovering, so we killed and ate it. This was only the 8th and we had four days more to go before the supply drop. We should be able to get food in Tigyaing, but our wireless batteries were running low and we had no more petrol left with which to run our charging engine.”

Fergusson had every reason to worry about rations: “The dieticians were horrified at our using it at all, since it was originally designed for parachutists to live on for a maximum period of five days.” Each man could expect a day’s ration, weighing two pounds, consisting of 12 biscuits, 2 oz of cheese, nuts and raisins, some dates, 20 cigarettes, tea, sugar and milk and a packet of salt. There was also supposed to be chocolate but two packets out of three had acid drops instead. Fergusson was especially unlucky: “I only got chocolate twice.”

Hungry and exhausted, they were still prepared to cross the gigantic Irrawaddy and march on east to destroy another target. Calvert’s No. 3 Column was also making for the Irrawaddy, but the Japanese were hot on their heels.

On March 6, 1943, No. 5 Column split into its fighting groups and made for the small Japanese garrison at Nankan, the gorge and Bonchaung Station’s bridge. Meanwhile, a Burma Rifles (Burrif) party under Captain John Fraser was briefed to recce the planned Irrawaddy crossing point, the ferry town of Tigyaung, around 35 miles distant.

On that morning, as Fergusson moved off, a runner came in reporting that the Nankan group was engaging Japanese in Kyaik-in village. The gorge party then made straight for the gorge and Fergusson decided that his main body should go straight across country to Bonchaung, while the remaining Rifle Platoon was ordered to back up the group fighting in Nyaik-in. There were casualties on both sides, including Platoon Commander John Kerr, who suffered a leg wound. Fergusson decided to take a look. Kerr told him they had run into a Japanese truck parked in the village. They opened up and killed several of the enemy, sustaining two killed and several wounded themselves. The truck then drove off. At that point Kerr’s men had no idea they were still at risk. A new light machine gun opened fire, hitting Kerr and several others. Later, the Column Commander himself had a close shave: “While he was telling me this, there was a sudden report just behind my ear, and I spun round to find Peter Dorans with a smoking rifle, and one of the two ‘dead’ Japs in the road writhing. He had suddenly flung himself upon his elbow and pointed his rifle at me. Peter shot him again and finally dispatched him.”

Now Fergusson faced his greatest horror: “What to do with the wounded?” Five men were unable to move, including Kerr. He and two others were carried by mule into the village. The remaining two could not be moved. Fergusson told Kerr where they were. There were 16 dead Japanese around and more enemy troops could be expected when the truck driver raised the alarm. With the Rifle Platoons now back, Fergusson headed off but had trouble finding the Bonchaung track. After a hard struggle they arrived, and found the Commando Platoon busily preparing the bridge for demolition. “Hasty” charges were already in place, so they could be blown if the Chindits were disturbed before the main charges were ready.

When the bridge was blown the results were impressive: “The flash illuminated the whole hillside. It showed the men standing tense and waiting, the muleteers with a good grip of their mules; and the brown of the path and the green of the trees preternaturally vivid. Then came the bang. The mules plunged and kicked, the hills for miles around rolled the noise of it about their hollows and flung it to their neighbours … all of us hoped that John Kerr and his little group of abandoned men, whose sacrifice had helped to make it possible, heard it also, and knew that we had accomplished that which we had come so far to do.” Then they heard a second great explosion – the gorge was blown.

On that same day, Major Michael Calvert’s No. 3 Column blew up two large railway bridges (one with a 300 ft span). Calvert called in an air strike against Japanese positions at Wuntho, 10 miles to the south. They then set ambushes and killed many Japanese without loss to themselves. Both No. 3 and No. 5 Columns had mauled the railway.

MARCH 7, 1943:

It was now a question of avoiding trouble and getting to the Irrawaddy as quickly as possible. As they marched, No. 5 Column’s Commander worried about the party that had been dispatched to Nankan. He had expected them back by now. He could only hope this group of around 30 would turn up at the rendezvous.

They halted at noon on March 7 – Fergusson wanted the wireless. He reported the destruction of the bridge and the blown gorge. He also learnt that Captain John Fraser was making good progress towards Tigyaing, the river crossing.

The Column then reached a fordable point on the Meza River, at Peinnegon village. There was smallpox in this village, so the men didn’t linger. They turned south, moving along the east bank of the river. They halted in less than a mile. Fergusson wrote: “… the jungle was exceedingly thick and all of us tired: we had marched 113 miles in seven days and had a considerable emotional strain as well, while our loads weighed an average of 60 lbs.” They stopped for the night at 16.00 and were asleep before dark.

On March 8 a small group was sent on ahead to reach the RV, as it closed at noon and it was possible that the main body wouldn’t get there in time. In fact, the main body stopped before the RV for a meal and, most importantly, a scheduled communication with Brigade. Fergusson received the message that No. 1 (Southern) Group had not been heard from for 10 days, suggesting that crossing the Irrawaddy was hazardous. No. 5 Column was given discretion to cross the Irrawaddy or, instead, base itself in the Gangaw Hills and harass railway repair gangs.

The Southern Group had enjoyed mixed fortunes. No. 1 Column was the first to cut the railway, on March 3 just north of Kyaikthin. However, on the preceding night No. 2 Column fought an action near that village and was dispersed. Fergusson, meanwhile, found the warning message “distinctly unsettling”. He told Brigade he would think on it and respond with a decision in a few hours. As they moved on the Column Commander wrestled with the issues. He had received a favourable report on the prospects for crossing at Tigyaing and the Japanese would be expecting them to start their return to India rather than go further east. On the other hand, crossing the huge river would be tricky and No. 5 Column was still incomplete. There was also the thorny question of how to get back. He did not know that the Northern Group’s No. 4 Column had been ambushed and broken up. This meant that Wingate was left with just four columns under direction, to continue Longcloth.

There was no sign of the missing groups – the Nankan and gorge parties. Bernard Fergusson told John Fraser that he’d wait at the RV for another 24 hours. Fraser said there were no Japanese at Tigyaing. Then the Nankan party reached the RV. They had been short-handed following the action involving Kerr and decided not to go on to Nankan. The No. 5 Column Commander signalled that he would attempt the Irrawaddy crossing: “… I proposed to try it and then to march for the Shweli bridge on the road running from the main Burma Road up to Bhamo. If this could be destroyed … the isolation of Myitkyina would be complete …” He hoped to reach this suspension bridge by around March 20.

Where was the gorge party? Fergusson fretted as he attempted to sleep. He was under tremendous pressure. He hoped for a supply drop on March 12 at Pegon village – 20 miles on the other side of the Irrawaddy: “The food problem was rather acute, for it was now 10 days since we started our last five days’ supply, and we were all heartily sick of the rice bought in the Happy Valley. A mule which had been shot in the action at Kyaik-in showed no signs of recovering, so we killed and ate it. This was only the 8th and we had four days more to go before the supply drop. We should be able to get food in Tigyaing, but our wireless batteries were running low and we had no more petrol left with which to run our charging engine.”

Fergusson had every reason to worry about rations: “The dieticians were horrified at our using it at all, since it was originally designed for parachutists to live on for a maximum period of five days.” Each man could expect a day’s ration, weighing two pounds, consisting of 12 biscuits, 2 oz of cheese, nuts and raisins, some dates, 20 cigarettes, tea, sugar and milk and a packet of salt. There was also supposed to be chocolate but two packets out of three had acid drops instead. Fergusson was especially unlucky: “I only got chocolate twice.”

Hungry and exhausted, they were still prepared to cross the gigantic Irrawaddy and march on east to destroy another target. Calvert’s No. 3 Column was also making for the Irrawaddy, but the Japanese were hot on their heels.

MARCH 9, 1943:

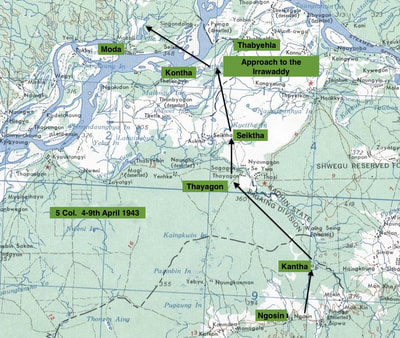

On March 8 Fergusson and Calvert had been given discretion on the issue of whether to cross the Irrawaddy, but then Southern Group’s No. 1 Column got back in touch - after a long radio silence - and announced their crossing of the Irrawaddy during the night of March 9/10. This made up Wingate’s mind. Northern Group columns would also cross, on 10-13 March, south of Tigyaing.

On the morning of March 9 Fergusson heard, with a mixture of relief and annoyance, that Jim Harman’s missing gorge group had already joined John Fraser at Tigyaing. This group had reached the RV two hours early, found no-one there and decided to press on to the river. Fergusson’s main body set off for the ferry town - a nervous march across open paddy. They could be seen for three miles in any direction. The main body arrived safely and met up with Fraser. Fergusson then set the wheels in motion. Three platoons were told to enter the town, take control of the boats and form a perimeter around Tigyaing. The main body would then enter. Within minutes of their arrival, a Japanese aircraft flew over the town and dropped leaflets, urging the Chindits to surrender. No. 5 Column’s Commander felt that the Japanese wouldn’t have bothered with leaflets if they were positioned to intercept them before a crossing. Nevertheless, there was a Japanese garrison at Tawma, just eight miles south west, across the marshes. They had to crack on as quickly as possible.

Fergusson marched his men in, in threes, to make an impression on the locals. The town soon developed a festive atmosphere and the shops opened. Jim Harman’s platoon was soon across and the boats were readied for the next group. Bernard Fergusson got his first look at the Irrawaddy: “My first reaction was to thank my stars I had come to a ferry town; getting across without the help of proper boats was obviously out of the question. It was fully a mile wide; although much of the space was filled up with sandbanks, the actual channel was not less than half a mile.”

Around 20 boats were soon busy. The men had to splash across the shallows from the waterfront to the main sandbank, where they embarked. Two platoons were told they were next.

Immediately opposite the crossing point was Myadaung village and beyond were the hills around Pegon, the location of their much-needed supply drop. They bought up supplies in Tigyaing – eggs, potatoes, rice, vegetables and fruit. Men and animals continued to cross over to the big sandbank, with others coming forward as boats became available. The afternoon was running thin but it looked as though they could be over before dark. About 45 minutes before dark, only one platoon remained to cross. It was brought in to hold a smaller perimeter around the waterfront. Suddenly, the atmosphere cooled, the waterfront crowd melted away and the boatmen – instead of bringing their boats back – disappeared downriver. They had just one boat still under command when this happened. Fortunately, another boat, on the other side of the river, was commandeered before it could shove off and retreat.

Major Fergusson later heard that 200 Japanese were marching towards them, following the Tigyaing bank from the south. The Longcloth force still had around 60 men and 10 animals waiting to cross. It was a slow business yet all but completed when they were fired on from the main river bank, just south of the town. Fergusson and the few still on the wrong side stayed stock still. All they could do was wait for a boat. It should be possible to get everyone over in one trip. Fergusson described the last minutes: “Out of the blackness came the creaking of a boat. We filled it with the remaining Bren gunners, with Cairns, Peter Dorans and a few more odd men. As they were getting in, the other boat came … and grounded safely … The rest of us got in …”

The heavily-laden Column Commander struggled to enter the boat. He was hauled in by the seat of his trousers. Fergusson crossed the river, under fire, in unflattering fashion: on his knees, with his behind in the air. He couldn’t move for fear of capsizing the small boat, which rolled at any excuse.

It proved difficult to form up on the other side of the river but, eventually, they succeeded and marched out of the village and away from the Irrawaddy. Major Fergusson wrote: “… it was not long before we were bedded down, after the most exciting day of my young life.”

Michael Calvert’s No. 3 Column had a similar experience, with the rear guard coming under fire. They crossed successfully but at the cost of seven dead and six wounded. Now on the other side, Calvert had to leave his wounded with the villagers. One was given a lethal dose of morphine, as an act of mercy. Calvert decided to reach out to the Japanese Commander who would eventually find the remaining five. He left a note which included the sentence: “I leave them confidently in your charge, knowing that with your well-known traditions of Bushido, you will look after them as well as if they were your own.” Much later, Calvert learned that his note had worked - the wounded were treated reasonably.

MARCH 11, 1943:

Fergusson’s No. 5 Column rested up after the crossing. They marched on for a few miles then called a halt in dense jungle. The Column Commander realised that to push on hard would endanger them, as the enemy would calculate their likely progress and would soon be on their heels.

The other side of the Irrawaddy felt safe but, within a short period, the country between the Irrawaddy and the Shweli would begin to feel like a prison. Fergusson struck out for Pegon on the 11th, hoping to reach it the following day. He would then call for a supply drop on the 13th. The jungle was the thickest they had encountered so far. On the 12th they marched along a virtually dry chaung. They avoided the road to Pegon and planned to descend on the village through the mountains that hedged it. At midday on March 12 the Column heard aircraft and were shocked by a wireless message revealing that the Pegon drop provisionally arranged for that day had just been delivered. Fergusson couldn’t believe that his request was honoured without the usual confirmation.

They spent the night at the head of the Myauk Chaung. On the morning of the 13th they moved off, climbing heavily then stopping at noon for three hours. There was a Sick Parade and Platoon Commanders inspected their men’s feet and rifles. The wireless was in operation. The men ate whatever was available to them. It was less than four miles to Pegon and Fergusson planned to give his men a rest that afternoon. The problem was that the route down from the mountains was so steep that it was impossible to get the mules down. By 16.00 they were no nearer the village than in the morning.

A drop had been confirmed for the following day, the 14th. Eventually, a track was discovered and an advance party managed to reach the drop site before the aircraft arrived at 10.00. The signal fires were ready for them.

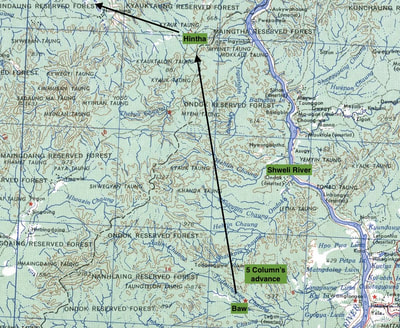

Fergusson wrote: “Out of that drop we got five days’ rations and the petrol, as well as much mail, newspapers and Penguin books. The only things missing were the boots and clothing for which we had indented and of which we were in dire need.” They were now well ahead of the Brigade and making for Inywa, where the Shweli and Irrawaddy come together. With time to spare, No. 5 Column waited for the aircraft to arrive with the all-important boots and clothes – anxiously awaited as the men were now infested with lice. Then came the news that aircraft couldn’t be spared for another drop.

The Column continued to rest on the morning of March 15. They left the village at 15.00, moving in a south-easterly direction and then south, making for Mogok village. In the late afternoon they were caught crossing open ground by a Japanese aircraft. Fergusson noted: “Luckily, at the moment we were spotted we were heading east, whereas our true direction was south …”

The going was unpleasant: “… the next few days of marching were desperately thirsty and only the strictest water discipline got us through them. The soil was red laterite and the jungle low dry teak; the only life that flourished there was red ants, with the most vicious sting imaginable. They would stand on their heads and burrow into you as if with a pneumatic drill. If you were unlucky enough to brush a tree with your sleeve, you would spend the next 15 minutes in a torture compared to which the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian was a holiday with pay.”

The next day, March 16, they found a few stinking waterholes at noon. They found two more that night and drank them dry. By morning, enough water had oozed into them to fill their water bottles for the trials ahead.

Wingate’s Columns were now being hunted in a waterless plain heavily patrolled by Japanese forces. They were near the limit of the range of supply-dropping aircraft. The four columns would have to go hungry for extended periods. There were only five aircraft earmarked for supply drops and two were Hudsons, unsuited to this role. Their only comfort was the presence of meat on the hoof.

On March 8 Fergusson and Calvert had been given discretion on the issue of whether to cross the Irrawaddy, but then Southern Group’s No. 1 Column got back in touch - after a long radio silence - and announced their crossing of the Irrawaddy during the night of March 9/10. This made up Wingate’s mind. Northern Group columns would also cross, on 10-13 March, south of Tigyaing.

On the morning of March 9 Fergusson heard, with a mixture of relief and annoyance, that Jim Harman’s missing gorge group had already joined John Fraser at Tigyaing. This group had reached the RV two hours early, found no-one there and decided to press on to the river. Fergusson’s main body set off for the ferry town - a nervous march across open paddy. They could be seen for three miles in any direction. The main body arrived safely and met up with Fraser. Fergusson then set the wheels in motion. Three platoons were told to enter the town, take control of the boats and form a perimeter around Tigyaing. The main body would then enter. Within minutes of their arrival, a Japanese aircraft flew over the town and dropped leaflets, urging the Chindits to surrender. No. 5 Column’s Commander felt that the Japanese wouldn’t have bothered with leaflets if they were positioned to intercept them before a crossing. Nevertheless, there was a Japanese garrison at Tawma, just eight miles south west, across the marshes. They had to crack on as quickly as possible.

Fergusson marched his men in, in threes, to make an impression on the locals. The town soon developed a festive atmosphere and the shops opened. Jim Harman’s platoon was soon across and the boats were readied for the next group. Bernard Fergusson got his first look at the Irrawaddy: “My first reaction was to thank my stars I had come to a ferry town; getting across without the help of proper boats was obviously out of the question. It was fully a mile wide; although much of the space was filled up with sandbanks, the actual channel was not less than half a mile.”

Around 20 boats were soon busy. The men had to splash across the shallows from the waterfront to the main sandbank, where they embarked. Two platoons were told they were next.

Immediately opposite the crossing point was Myadaung village and beyond were the hills around Pegon, the location of their much-needed supply drop. They bought up supplies in Tigyaing – eggs, potatoes, rice, vegetables and fruit. Men and animals continued to cross over to the big sandbank, with others coming forward as boats became available. The afternoon was running thin but it looked as though they could be over before dark. About 45 minutes before dark, only one platoon remained to cross. It was brought in to hold a smaller perimeter around the waterfront. Suddenly, the atmosphere cooled, the waterfront crowd melted away and the boatmen – instead of bringing their boats back – disappeared downriver. They had just one boat still under command when this happened. Fortunately, another boat, on the other side of the river, was commandeered before it could shove off and retreat.

Major Fergusson later heard that 200 Japanese were marching towards them, following the Tigyaing bank from the south. The Longcloth force still had around 60 men and 10 animals waiting to cross. It was a slow business yet all but completed when they were fired on from the main river bank, just south of the town. Fergusson and the few still on the wrong side stayed stock still. All they could do was wait for a boat. It should be possible to get everyone over in one trip. Fergusson described the last minutes: “Out of the blackness came the creaking of a boat. We filled it with the remaining Bren gunners, with Cairns, Peter Dorans and a few more odd men. As they were getting in, the other boat came … and grounded safely … The rest of us got in …”

The heavily-laden Column Commander struggled to enter the boat. He was hauled in by the seat of his trousers. Fergusson crossed the river, under fire, in unflattering fashion: on his knees, with his behind in the air. He couldn’t move for fear of capsizing the small boat, which rolled at any excuse.

It proved difficult to form up on the other side of the river but, eventually, they succeeded and marched out of the village and away from the Irrawaddy. Major Fergusson wrote: “… it was not long before we were bedded down, after the most exciting day of my young life.”

Michael Calvert’s No. 3 Column had a similar experience, with the rear guard coming under fire. They crossed successfully but at the cost of seven dead and six wounded. Now on the other side, Calvert had to leave his wounded with the villagers. One was given a lethal dose of morphine, as an act of mercy. Calvert decided to reach out to the Japanese Commander who would eventually find the remaining five. He left a note which included the sentence: “I leave them confidently in your charge, knowing that with your well-known traditions of Bushido, you will look after them as well as if they were your own.” Much later, Calvert learned that his note had worked - the wounded were treated reasonably.

MARCH 11, 1943:

Fergusson’s No. 5 Column rested up after the crossing. They marched on for a few miles then called a halt in dense jungle. The Column Commander realised that to push on hard would endanger them, as the enemy would calculate their likely progress and would soon be on their heels.

The other side of the Irrawaddy felt safe but, within a short period, the country between the Irrawaddy and the Shweli would begin to feel like a prison. Fergusson struck out for Pegon on the 11th, hoping to reach it the following day. He would then call for a supply drop on the 13th. The jungle was the thickest they had encountered so far. On the 12th they marched along a virtually dry chaung. They avoided the road to Pegon and planned to descend on the village through the mountains that hedged it. At midday on March 12 the Column heard aircraft and were shocked by a wireless message revealing that the Pegon drop provisionally arranged for that day had just been delivered. Fergusson couldn’t believe that his request was honoured without the usual confirmation.

They spent the night at the head of the Myauk Chaung. On the morning of the 13th they moved off, climbing heavily then stopping at noon for three hours. There was a Sick Parade and Platoon Commanders inspected their men’s feet and rifles. The wireless was in operation. The men ate whatever was available to them. It was less than four miles to Pegon and Fergusson planned to give his men a rest that afternoon. The problem was that the route down from the mountains was so steep that it was impossible to get the mules down. By 16.00 they were no nearer the village than in the morning.

A drop had been confirmed for the following day, the 14th. Eventually, a track was discovered and an advance party managed to reach the drop site before the aircraft arrived at 10.00. The signal fires were ready for them.

Fergusson wrote: “Out of that drop we got five days’ rations and the petrol, as well as much mail, newspapers and Penguin books. The only things missing were the boots and clothing for which we had indented and of which we were in dire need.” They were now well ahead of the Brigade and making for Inywa, where the Shweli and Irrawaddy come together. With time to spare, No. 5 Column waited for the aircraft to arrive with the all-important boots and clothes – anxiously awaited as the men were now infested with lice. Then came the news that aircraft couldn’t be spared for another drop.

The Column continued to rest on the morning of March 15. They left the village at 15.00, moving in a south-easterly direction and then south, making for Mogok village. In the late afternoon they were caught crossing open ground by a Japanese aircraft. Fergusson noted: “Luckily, at the moment we were spotted we were heading east, whereas our true direction was south …”