Frank Lea, Ellis Grundy and the Kaukkwe Chaung

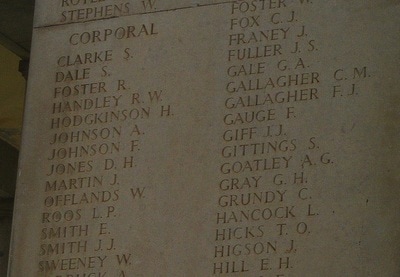

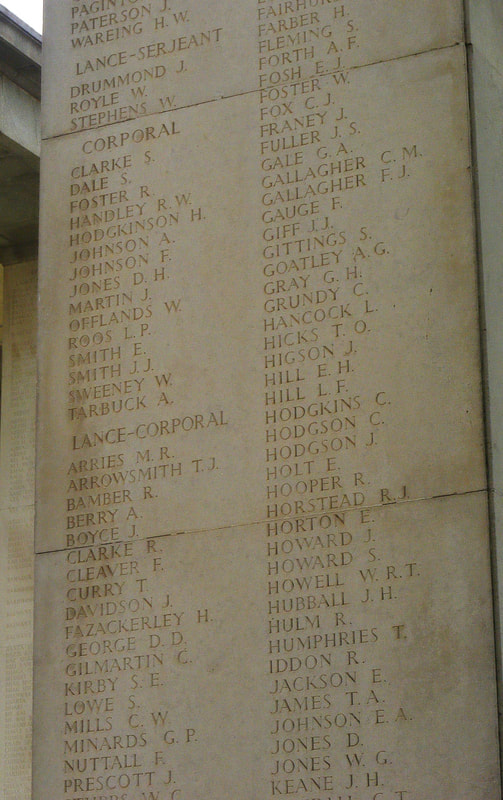

The Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery.

The Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery.

The soldier’s memoir written below was published in the Burma Star Association magazine, Dekho in the Spring of 2011. It was an old veteran’s way of honouring his lost comrade from their days in the jungles of Burma in 1943. The short article was meant as a thank you from one man who lived to tell the tale to another whom sadly did not. For me and my ongoing research into Operation Longcloth, the article unlocked another of the mysteries from those fateful days.

Seen pictured to the left is the Rangoon Memorial, the monument constructed to remember the men from the Burma campaign who have no known grave and who lie hidden somewhere in the jungles of that far off land. You will find the names of the men mentioned in this story inscribed upon Face 5 of the memorial.

Firstly, here is what Frank Lea had to say about his fellow Chindit comrade Clifford ‘Ellis’ Grundy. There are some minor adjustments made to his story in order to help the reader understand the context of the time, otherwise it is presented exactly as Frank intended:

We of the first Wingate expedition in Burma had been ambushed by the Japanese, while on our way back to India. Myself, Frank Lea (3780184) having fractured my wrist a week earlier, was unable to fire my rifle, but was able to render assistance to a few who had been wounded.

One chap was named Ellis Grundy, a Lancashire man from Earlstown. He had been shot in the upper arm and I believe that the humerus was fractured. After dressing the wound and improvising a splint and arm sling, I found that the main body of 8 Column had split up and that six of us were now alone. We set off in a generally North-westerly direction and collected other stragglers.

Grundy kept dropping back, I brought him up to the front though he protested, saying that he was holding us up. For four days he kept on going, though he was in considerable pain. It was very rough terrain where we were, and clambering up river gorges was arduous enough even for a man with two good arms.

I took his rifle to make his task a little easier and each day borrowed another field dressing to dress his wound. On the fourth day after the ambush we stopped at a friendly village called Kashang and it was here that Grundy resolved to stay until his wound healed. I tried to persuade him to carry on, but he was adamant, the headman of the village promised to look after him and provide shelter away from the village in case enemy troops passed through.

Ellis Grundy never came out. Twelve months later I re-visited the village with a patrol of Burma Riflemen. On questioning the headman, who did recognise me, I was told that Grundy had only stayed one night and the next morning had set off on his own. I realised that Grundy’s action in 1943 was but an heroic subterfuge and he had never intended to stay in the village. He knew he was slowing us down and used the village as an excuse to let us go on our way unhindered.

Every one has heard of Captain Oates on Scott’s Antarctic expedition, who went out in a blizzard so that his compatriots would have a better chance of survival. Until now, few have known of the heroism of Ellis Grundy, a son of Earlstown, who gave his life for others. I am proud to be the one to tell this story, that for so long has been hidden. No medals were won, but of such men are heroes made.

If there be any relatives or friends still living in Earlstown, let them be proud of this little place, which appears as a dot on the map, but from where Ellis Grundy came.

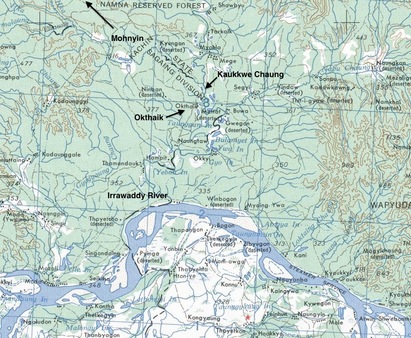

So there you have the story, as remembered by Frank Lea almost 68 years after the event. His memoir added to the information I already possessed about the 13th King's, and began to add flesh to the statement made by Major Walter Scott, commander of Column 8 that year, when he said that he had lost 6 men killed and several missing after the action at the Kaukkwe Chaung. The column had been caught out by a Japanese patrol on the 30th April, when the enemy had attacked the rear of the column as it tried to ferry its non-swimmers over the fast flowing Kaukkwe Chaung. A number of NCO's had defended the retreating unit from the near bank as the others struggled to get across.

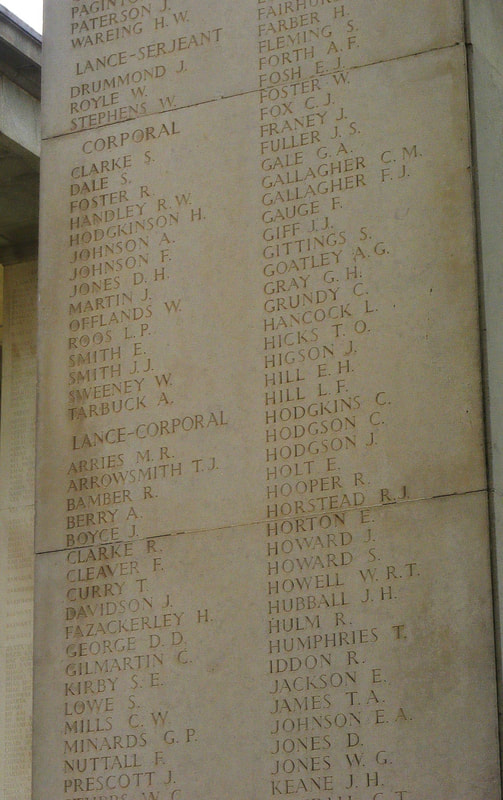

Shown below are two photographs in relation to this story. The first is an image of Pte. Clifford Grundy, seen in his Army greatcoat and most likely taken earlier in the war and back home in England. The other is an image of Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, including the inscription for Clifford Grundy. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Seen pictured to the left is the Rangoon Memorial, the monument constructed to remember the men from the Burma campaign who have no known grave and who lie hidden somewhere in the jungles of that far off land. You will find the names of the men mentioned in this story inscribed upon Face 5 of the memorial.

Firstly, here is what Frank Lea had to say about his fellow Chindit comrade Clifford ‘Ellis’ Grundy. There are some minor adjustments made to his story in order to help the reader understand the context of the time, otherwise it is presented exactly as Frank intended:

We of the first Wingate expedition in Burma had been ambushed by the Japanese, while on our way back to India. Myself, Frank Lea (3780184) having fractured my wrist a week earlier, was unable to fire my rifle, but was able to render assistance to a few who had been wounded.

One chap was named Ellis Grundy, a Lancashire man from Earlstown. He had been shot in the upper arm and I believe that the humerus was fractured. After dressing the wound and improvising a splint and arm sling, I found that the main body of 8 Column had split up and that six of us were now alone. We set off in a generally North-westerly direction and collected other stragglers.

Grundy kept dropping back, I brought him up to the front though he protested, saying that he was holding us up. For four days he kept on going, though he was in considerable pain. It was very rough terrain where we were, and clambering up river gorges was arduous enough even for a man with two good arms.

I took his rifle to make his task a little easier and each day borrowed another field dressing to dress his wound. On the fourth day after the ambush we stopped at a friendly village called Kashang and it was here that Grundy resolved to stay until his wound healed. I tried to persuade him to carry on, but he was adamant, the headman of the village promised to look after him and provide shelter away from the village in case enemy troops passed through.

Ellis Grundy never came out. Twelve months later I re-visited the village with a patrol of Burma Riflemen. On questioning the headman, who did recognise me, I was told that Grundy had only stayed one night and the next morning had set off on his own. I realised that Grundy’s action in 1943 was but an heroic subterfuge and he had never intended to stay in the village. He knew he was slowing us down and used the village as an excuse to let us go on our way unhindered.

Every one has heard of Captain Oates on Scott’s Antarctic expedition, who went out in a blizzard so that his compatriots would have a better chance of survival. Until now, few have known of the heroism of Ellis Grundy, a son of Earlstown, who gave his life for others. I am proud to be the one to tell this story, that for so long has been hidden. No medals were won, but of such men are heroes made.

If there be any relatives or friends still living in Earlstown, let them be proud of this little place, which appears as a dot on the map, but from where Ellis Grundy came.

So there you have the story, as remembered by Frank Lea almost 68 years after the event. His memoir added to the information I already possessed about the 13th King's, and began to add flesh to the statement made by Major Walter Scott, commander of Column 8 that year, when he said that he had lost 6 men killed and several missing after the action at the Kaukkwe Chaung. The column had been caught out by a Japanese patrol on the 30th April, when the enemy had attacked the rear of the column as it tried to ferry its non-swimmers over the fast flowing Kaukkwe Chaung. A number of NCO's had defended the retreating unit from the near bank as the others struggled to get across.

Shown below are two photographs in relation to this story. The first is an image of Pte. Clifford Grundy, seen in his Army greatcoat and most likely taken earlier in the war and back home in England. The other is an image of Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, including the inscription for Clifford Grundy. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

From the lists available in the battalion’s War Diary for 1943 and the witness reports made by men who had been fortunate enough to get back to India that year, I can now present with some confidence ten of the missing from the engagement at the Kaukkwe Chaung.

Those killed in action were:

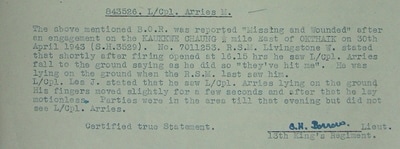

Lance Corporal 843526 Mansfield Robert Arries as mentioned in Lea’s report (seen below) given after his return to India.

Pte. 3772261 Joseph Cooke stated as last seen at 16.15 hours taking up a firing position at the river, but was subsequently never seen or heard of again. This was witnessed by Pte. A. Reed. To view Joseph Cooke's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2507656/joseph-cooke/

CSM 3186646 John Fraser-Wilson, reported to have been last seen engaging the Japanese with his Thompson sub machine gun at the Kaukkwe Chaung, as witnessed by RSM Livingstone. John's own story can be seen by clicking this link: JF Wilson and scrolling to the third story on the page.

Arries, Cooke and Fraser-Wilson had all served in Northern Section’s HQ and had come to be with 8 Column after the mass dispersal at the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March. The rest of the men were all with 8 Column from the outset.

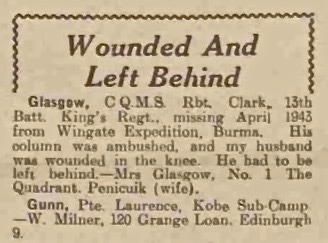

Colour Sergeant Major 3192553 Robert Clark Glasgow. As witnessed by Major Scott and mentioned in several books about Operation Longcloth, here is a paraphrased account of what happened to CSM Glasgow. Taken from Wingate’s Lost Brigade and with thanks to author Phil Chinnery for permission to reproduce his narrative on this website.

As Major Scott collected up the stragglers in the area, he came across Colour Sergeant Glasgow, who had received a serious wound, which resulted in a shattered knee. He refused all offers of help and asked Scott and some of the other men to shoot him. He knew that in his condition the Japanese would not bother to take him prisoner and would most likely have bayoneted him. Scott told him to lie low until after dark, when he would send some men back to collect him, Glasgow told the commander to give him some grenades and to leave him be. He was never seen again.

In his recorded interview at the Imperial War Museum in 1990, Scott simply stated that the Colour Sergeant was “an outstanding soldier."

Here are Robert Glasgow's CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/3069841/robert-clark-glasgow/

The soldiers who gave witness statements for the action at the Kaukkwe Chaung action, were:

Lance/Sgt. 7013950 G. McCool

Pte. 3780184 Frank Lea

Pte. 5192278 A. Reed

Seen below are some images in relation to this section of the story, including the witness statement given by Frank Lea in regards the last known condition of Lance Corporal Mansfield Arries. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Those killed in action were:

Lance Corporal 843526 Mansfield Robert Arries as mentioned in Lea’s report (seen below) given after his return to India.

Pte. 3772261 Joseph Cooke stated as last seen at 16.15 hours taking up a firing position at the river, but was subsequently never seen or heard of again. This was witnessed by Pte. A. Reed. To view Joseph Cooke's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/2507656/joseph-cooke/

CSM 3186646 John Fraser-Wilson, reported to have been last seen engaging the Japanese with his Thompson sub machine gun at the Kaukkwe Chaung, as witnessed by RSM Livingstone. John's own story can be seen by clicking this link: JF Wilson and scrolling to the third story on the page.

Arries, Cooke and Fraser-Wilson had all served in Northern Section’s HQ and had come to be with 8 Column after the mass dispersal at the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March. The rest of the men were all with 8 Column from the outset.

Colour Sergeant Major 3192553 Robert Clark Glasgow. As witnessed by Major Scott and mentioned in several books about Operation Longcloth, here is a paraphrased account of what happened to CSM Glasgow. Taken from Wingate’s Lost Brigade and with thanks to author Phil Chinnery for permission to reproduce his narrative on this website.

As Major Scott collected up the stragglers in the area, he came across Colour Sergeant Glasgow, who had received a serious wound, which resulted in a shattered knee. He refused all offers of help and asked Scott and some of the other men to shoot him. He knew that in his condition the Japanese would not bother to take him prisoner and would most likely have bayoneted him. Scott told him to lie low until after dark, when he would send some men back to collect him, Glasgow told the commander to give him some grenades and to leave him be. He was never seen again.

In his recorded interview at the Imperial War Museum in 1990, Scott simply stated that the Colour Sergeant was “an outstanding soldier."

Here are Robert Glasgow's CWGC details: www.cwgc.org/find-records/find-war-dead/casualty-details/3069841/robert-clark-glasgow/

The soldiers who gave witness statements for the action at the Kaukkwe Chaung action, were:

Lance/Sgt. 7013950 G. McCool

Pte. 3780184 Frank Lea

Pte. 5192278 A. Reed

Seen below are some images in relation to this section of the story, including the witness statement given by Frank Lea in regards the last known condition of Lance Corporal Mansfield Arries. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

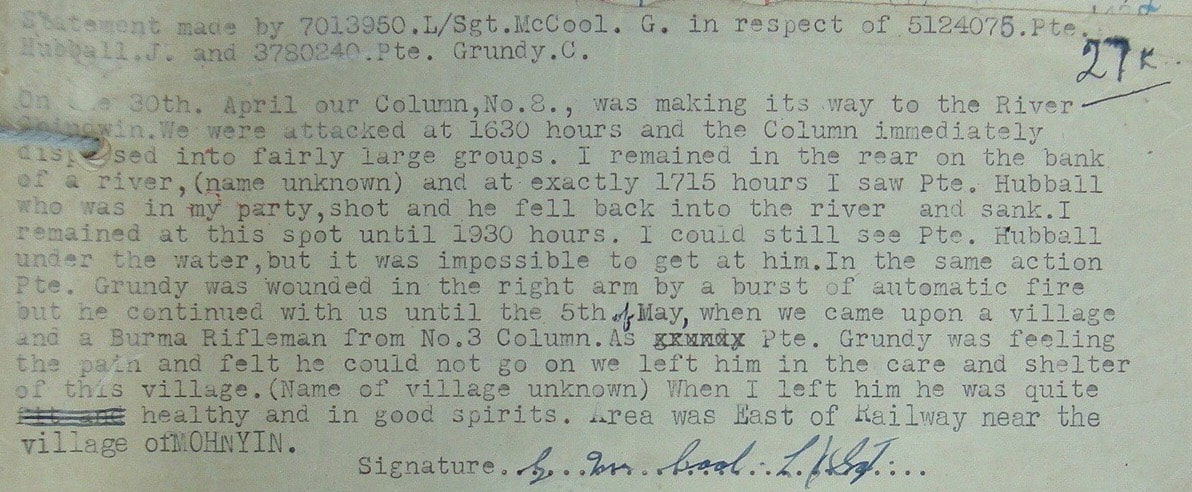

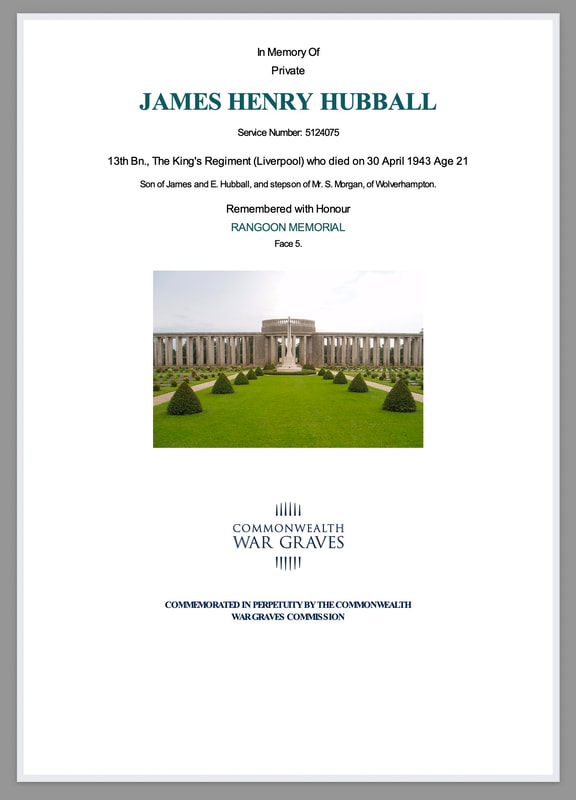

And so, what of Pte. 3780240 Clifford Grundy? His last movements and those of Pte. 5124075 James Henry Hubball are shown in the witness statement seen in the gallery below, as given by Lance Sergeant McCool. As you will read, his account differs hardly at all from the story Frank Lea has told us all these years later. James Henry Hubball was the son of James and Mrs. E. Hubball and the stepson of Mr. S. Morgan from Wolverhampton in the West Midlands of England.

James had been posted to the Royal Warwickshire Regiment earlier in the war, before being transferred to the 13th King's in India during September 1942. He was originally listed as missing in action as of the 1st May 1943, but this was later corrected, as per Sgt. McCool's testimony to killed in action on the 30th April. Pte. Hubball is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, just a few feet lower down the panel from Clifford Grundy and within the pages of the Wolverhampton Roll of Honour for WW2. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

James had been posted to the Royal Warwickshire Regiment earlier in the war, before being transferred to the 13th King's in India during September 1942. He was originally listed as missing in action as of the 1st May 1943, but this was later corrected, as per Sgt. McCool's testimony to killed in action on the 30th April. Pte. Hubball is remembered upon Face 5 of the Rangoon Memorial, just a few feet lower down the panel from Clifford Grundy and within the pages of the Wolverhampton Roll of Honour for WW2. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 26/07/2012

Having recently found some new documents in regard to the missing men from 1943, here is clarification of Clifford Grundy's last known whereabouts: "Pte. Grundy C. last seen 03/05/1943, left in village of Khasang, north east of Mohnyin."

Update 02/11/2013.

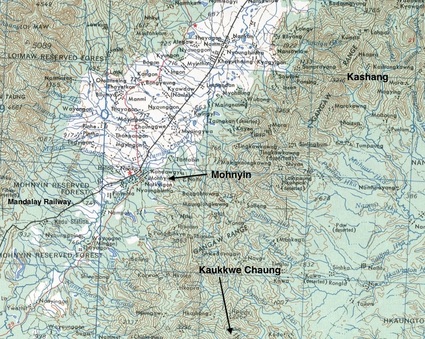

Shown below are two maps highlighting the locations mentioned during this story, the Kaukkwe Chaung and the village of Okthaik and the villages of Mohnyin and Kashang. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Having recently found some new documents in regard to the missing men from 1943, here is clarification of Clifford Grundy's last known whereabouts: "Pte. Grundy C. last seen 03/05/1943, left in village of Khasang, north east of Mohnyin."

Update 02/11/2013.

Shown below are two maps highlighting the locations mentioned during this story, the Kaukkwe Chaung and the village of Okthaik and the villages of Mohnyin and Kashang. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 01/12/2014.

In early August 2014, I was excited to receive an email contact from the family of Clifford Grundy. Karen Fazackerley told me that she had stumbled across my website when searching for information about her Great Uncle and his time in Burma. She was hoping that I would be able to put her in touch with Frank Lea. Sadly, although I had tried to make contact with Frank via the Burma Star Association Head Quarters, no contact address or telephone number were available from when he sent in his original article in 2011.

Karen also told me that:

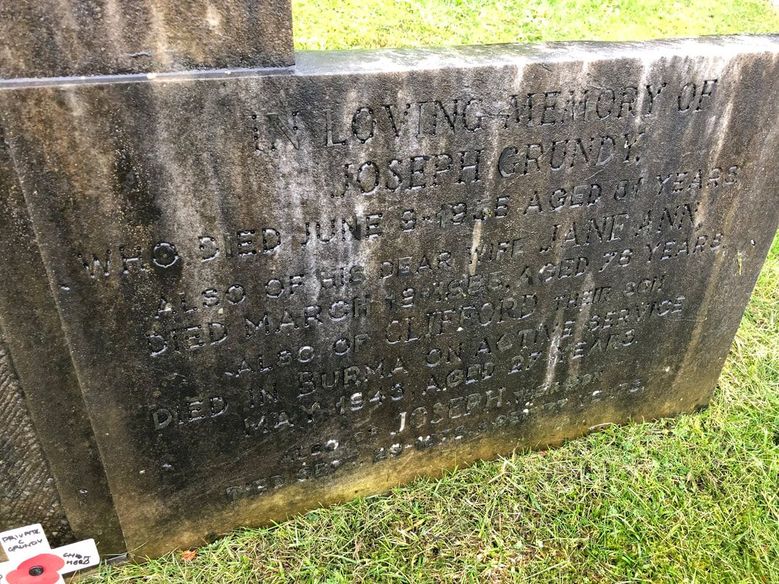

When my Grandma (Clifford's sister Jane) died I inherited all her photos and I have a photo of Clifford in Army uniform. I also have a photo of his gravestone at Heywood Cemetery, near Rochdale. His parents wanted somewhere to go to feel close to him when his body never came home from Burma, the gravestone is a little weather-worn but you can still see the inscription.

His parents were from Heywood and that's where he grew up with his three sisters Jane, Bertha and Temperance and I believe three brothers; his brother Leslie is still alive and aged 93. The family played a major role in the local Salvation Army.

I will ask my Dad what he has been told about Clifford's story over the years, growing up I was always told that he was shot and killed in the Burma jungle and left for dead. I had no idea at all that he took the decision to leave his men because he felt he was holding them back. His parents were told that he was shot in the jungle and left, there was also a story about him being blown up in a tank in the jungle too.

I was very pleased to be able to provide Karen with some of the original photographs and documents shown in the above story, especially the witness statements containing information about her Great Uncle Clifford. It would be an honour for me to add an image of Clifford Grundy to these pages at some point in the future.

Update 11/03/2015.

Seen below is a wonderful photograph of the extended Grundy family taken sometime during the years of WW1. This has been sent to me by Karen Fazackerley, the great niece of Clifford Grundy. Karen told me:

"Here is the photograph I promised you Steve; Clifford is standing to the left of his mother, he is the little boy wearing all black and standing on a chair, with his parents Joseph and Jane Ann and his other brothers and sisters. My Grandma (Jane) is sitting on the chair at the front on the left and my Great Uncle Leslie is the baby on my Great Grandma's knee."

In early August 2014, I was excited to receive an email contact from the family of Clifford Grundy. Karen Fazackerley told me that she had stumbled across my website when searching for information about her Great Uncle and his time in Burma. She was hoping that I would be able to put her in touch with Frank Lea. Sadly, although I had tried to make contact with Frank via the Burma Star Association Head Quarters, no contact address or telephone number were available from when he sent in his original article in 2011.

Karen also told me that:

When my Grandma (Clifford's sister Jane) died I inherited all her photos and I have a photo of Clifford in Army uniform. I also have a photo of his gravestone at Heywood Cemetery, near Rochdale. His parents wanted somewhere to go to feel close to him when his body never came home from Burma, the gravestone is a little weather-worn but you can still see the inscription.

His parents were from Heywood and that's where he grew up with his three sisters Jane, Bertha and Temperance and I believe three brothers; his brother Leslie is still alive and aged 93. The family played a major role in the local Salvation Army.

I will ask my Dad what he has been told about Clifford's story over the years, growing up I was always told that he was shot and killed in the Burma jungle and left for dead. I had no idea at all that he took the decision to leave his men because he felt he was holding them back. His parents were told that he was shot in the jungle and left, there was also a story about him being blown up in a tank in the jungle too.

I was very pleased to be able to provide Karen with some of the original photographs and documents shown in the above story, especially the witness statements containing information about her Great Uncle Clifford. It would be an honour for me to add an image of Clifford Grundy to these pages at some point in the future.

Update 11/03/2015.

Seen below is a wonderful photograph of the extended Grundy family taken sometime during the years of WW1. This has been sent to me by Karen Fazackerley, the great niece of Clifford Grundy. Karen told me:

"Here is the photograph I promised you Steve; Clifford is standing to the left of his mother, he is the little boy wearing all black and standing on a chair, with his parents Joseph and Jane Ann and his other brothers and sisters. My Grandma (Jane) is sitting on the chair at the front on the left and my Great Uncle Leslie is the baby on my Great Grandma's knee."

Update 12/03/2017.

Submitted in 1952 to The People newspaper as an entry in their 'War Stories' contest, here is another memoir from Pte. Frank Lea. The idea of the competition was to encourage ordinary men and women from the war services to speak up about their own unique WW2 experiences.

Over My Dead Body

BY FRANCIS LEA

I was with General Wingate somewhere behind the Jap lines in Burma and my orders were like this : "Corporal Lea! You will lead your column ahead to the road junction marked on the map, and No. 1 Platoon will follow directly behind. Go steady and keep your eyes skinned." Off we went through undergrowth until we came to a wide clearing. Things seemed ominously quiet, so I skirted the edge of the field.

Then came gunshots from our right. "Move to the left!" I shouted to my men and ran myself for the cover of a clump of bamboo, only to find in front of me a Japanese patrol not three yards away. I shouted and dropped as they fired. There was a sharp pain in my shoulder. My head was buried in the bamboo stubble, my right hand held my compass under my body and my left was outstretched just touching the sling of my Sten gun that had bounced out of my hand.

I opened my eyes and waited for the next shots that would end my short life. They did not come. Instead I felt a slight pull on my left hand as my Sten gun was picked up and then a slithering movement toward me in the undergrowth. The next second I felt the barrel of a rifle resting on my back. A Jap was using what he thought was my dead body as a sandbag. I held my breath and this time waited for the bullets of my own comrades to finish me.

I lay deathly still and then tried to move my right hand that was under my body toward the pouch in which were two hand grenades. I got there, then realised that I would have to lift my body to withdraw a grenade and that to move meant death. Next came the clatter of the rifle on my back. Hot cartridge shells ejected from it began dancing round my ears. I prayed that none would touch and burn me so that I should wince and show life.

The next seconds seemed like years, and I forced all my thoughts on a desire to see my son who was born after I left England. I lay scarcely daring to breathe, then came a tug at the pack on my back. The Japs were robbing me before they moved on. I closed my eyes. There was a tread of a boot on my fingers and I had to fight myself not to pull them away. A hand grasped the arm under my body and my whole body was lifted up while a knife slashed at the straps of my pack.

I sagged in their arms and was dropped. There was the tread of feet as the Japs moved off, and slowly I raised my head. My hand went to my grenade pouch and I lifted my body to throw one after them. At once came the sound of a movement, this time behind me. Down I dropped again to a new agony of suspense. Had I been seen moving by another Jap patrol? Was this to be the end after all? The next second came a low whistle, it was the tune of There's No Place Like Home. It was our own recognition signal and, such was my relief, my mouth was too dry to whistle back. Instead I whispered hoarsely : "Okay—it's Lea here." I had preserved my life, but I might have been a hero.

Submitted in 1952 to The People newspaper as an entry in their 'War Stories' contest, here is another memoir from Pte. Frank Lea. The idea of the competition was to encourage ordinary men and women from the war services to speak up about their own unique WW2 experiences.

Over My Dead Body

BY FRANCIS LEA

I was with General Wingate somewhere behind the Jap lines in Burma and my orders were like this : "Corporal Lea! You will lead your column ahead to the road junction marked on the map, and No. 1 Platoon will follow directly behind. Go steady and keep your eyes skinned." Off we went through undergrowth until we came to a wide clearing. Things seemed ominously quiet, so I skirted the edge of the field.

Then came gunshots from our right. "Move to the left!" I shouted to my men and ran myself for the cover of a clump of bamboo, only to find in front of me a Japanese patrol not three yards away. I shouted and dropped as they fired. There was a sharp pain in my shoulder. My head was buried in the bamboo stubble, my right hand held my compass under my body and my left was outstretched just touching the sling of my Sten gun that had bounced out of my hand.

I opened my eyes and waited for the next shots that would end my short life. They did not come. Instead I felt a slight pull on my left hand as my Sten gun was picked up and then a slithering movement toward me in the undergrowth. The next second I felt the barrel of a rifle resting on my back. A Jap was using what he thought was my dead body as a sandbag. I held my breath and this time waited for the bullets of my own comrades to finish me.

I lay deathly still and then tried to move my right hand that was under my body toward the pouch in which were two hand grenades. I got there, then realised that I would have to lift my body to withdraw a grenade and that to move meant death. Next came the clatter of the rifle on my back. Hot cartridge shells ejected from it began dancing round my ears. I prayed that none would touch and burn me so that I should wince and show life.

The next seconds seemed like years, and I forced all my thoughts on a desire to see my son who was born after I left England. I lay scarcely daring to breathe, then came a tug at the pack on my back. The Japs were robbing me before they moved on. I closed my eyes. There was a tread of a boot on my fingers and I had to fight myself not to pull them away. A hand grasped the arm under my body and my whole body was lifted up while a knife slashed at the straps of my pack.

I sagged in their arms and was dropped. There was the tread of feet as the Japs moved off, and slowly I raised my head. My hand went to my grenade pouch and I lifted my body to throw one after them. At once came the sound of a movement, this time behind me. Down I dropped again to a new agony of suspense. Had I been seen moving by another Jap patrol? Was this to be the end after all? The next second came a low whistle, it was the tune of There's No Place Like Home. It was our own recognition signal and, such was my relief, my mouth was too dry to whistle back. Instead I whispered hoarsely : "Okay—it's Lea here." I had preserved my life, but I might have been a hero.

Update 18/05/2017.

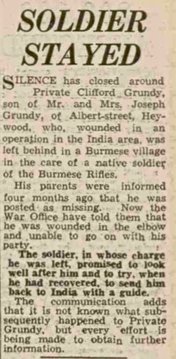

After an announcement in the Manchester Evening News on the 2nd August 1943, which reported Clifford Grundy as officially missing in the Indian theatre. The same newspaper followed up on this notification 12 weeks later with the following short article.

From the Manchester Evening News dated 12th November 1943 and under the headline, Soldier Stayed:

Silence has closed around Private Clifford Grundy, son of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Grundy of Albert Street in Heywood, who, wounded in an operation in the India area, was left behind in a Burmese village in the care of a native soldier of the Burma Rifles.

His parents were informed four months ago that he was posted as missing. Now the War Office have told them that he was wounded in the elbow and unable to go on with his party. The soldier, in whose charge he was left, promised to look well after him and to try when he had recovered, to send him back to India with a guide. The communication adds that it is not known what subsequently happened to Private Grundy, but every effort is being made to obtain further information.

The article transcribed above can be viewed by clicking on the image seen to the left.

After an announcement in the Manchester Evening News on the 2nd August 1943, which reported Clifford Grundy as officially missing in the Indian theatre. The same newspaper followed up on this notification 12 weeks later with the following short article.

From the Manchester Evening News dated 12th November 1943 and under the headline, Soldier Stayed:

Silence has closed around Private Clifford Grundy, son of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Grundy of Albert Street in Heywood, who, wounded in an operation in the India area, was left behind in a Burmese village in the care of a native soldier of the Burma Rifles.

His parents were informed four months ago that he was posted as missing. Now the War Office have told them that he was wounded in the elbow and unable to go on with his party. The soldier, in whose charge he was left, promised to look well after him and to try when he had recovered, to send him back to India with a guide. The communication adds that it is not known what subsequently happened to Private Grundy, but every effort is being made to obtain further information.

The article transcribed above can be viewed by clicking on the image seen to the left.

Update 16/07/2017.

It has been wonderful to see this website story grow over the past 6 years or so, with new information and photographs from many different sources. In June this year (2017), I was extremely pleased to receive the following email contact from Peter Lea, the son of Pte. Francis Lea:

My father served with the Chindits in both the first and second campaigns in Burma. He was Francis Lea, of the 13th Kings Liverpool Regiment. My father served in the first campaign, was shot, then when he became fit once more, returned to Burma with the Lancashire Fusiliers. My Dad didn't talk much about his experiences from the war until his latter years when he started to put it down in writing. He sadly died in 1990. In his writings he tells of a man named Clifford Ellis Grundy, who he left in the care and safety of the Headman of a village called Khasang. Pte. Grundy was injured and realised he was slowing the others down and said he couldn't carry on so as the others could make it back. My Dad desperately wanted to contact the Grundy family after the war and tell them what had happened, but was unable to do so. I believe that you have been in touch with the Grundy family and I would appreciate it if you could pass on my contact details so I could complete his wishes.

Many thanks, Peter Lea.

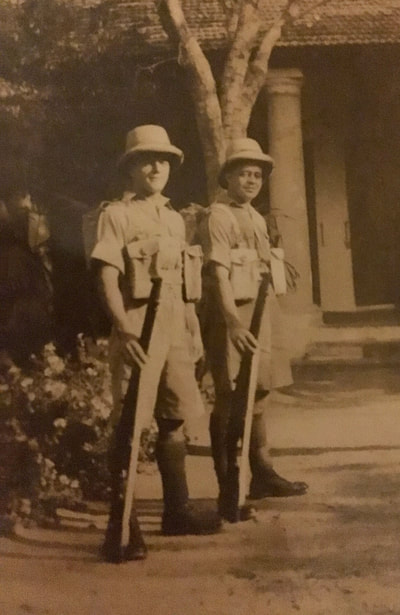

I have since sent both families the relevant contact details and sincerely hope that they have now spoken to one another and exchanged information and family anecdotes in relation to this incredible story. Seen below are some more photographs of the two soldiers at the centre of this narrative: Clifford Grundy and Francis Lea. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

It has been wonderful to see this website story grow over the past 6 years or so, with new information and photographs from many different sources. In June this year (2017), I was extremely pleased to receive the following email contact from Peter Lea, the son of Pte. Francis Lea:

My father served with the Chindits in both the first and second campaigns in Burma. He was Francis Lea, of the 13th Kings Liverpool Regiment. My father served in the first campaign, was shot, then when he became fit once more, returned to Burma with the Lancashire Fusiliers. My Dad didn't talk much about his experiences from the war until his latter years when he started to put it down in writing. He sadly died in 1990. In his writings he tells of a man named Clifford Ellis Grundy, who he left in the care and safety of the Headman of a village called Khasang. Pte. Grundy was injured and realised he was slowing the others down and said he couldn't carry on so as the others could make it back. My Dad desperately wanted to contact the Grundy family after the war and tell them what had happened, but was unable to do so. I believe that you have been in touch with the Grundy family and I would appreciate it if you could pass on my contact details so I could complete his wishes.

Many thanks, Peter Lea.

I have since sent both families the relevant contact details and sincerely hope that they have now spoken to one another and exchanged information and family anecdotes in relation to this incredible story. Seen below are some more photographs of the two soldiers at the centre of this narrative: Clifford Grundy and Francis Lea. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 04/02/2018.

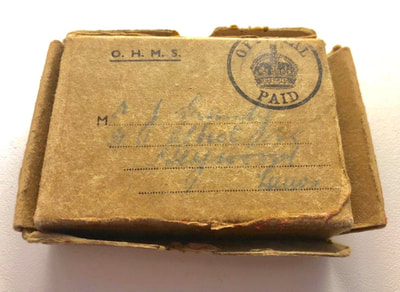

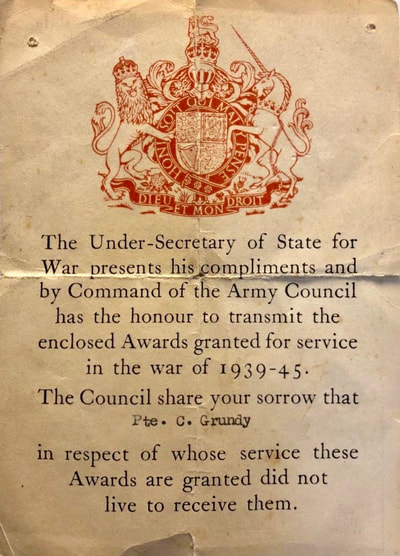

I was pleased recently, to receive the following email from Nigel Fitton:

Dear Steve,

Clifford Grundy was my great uncle on my mother's side of the family. I’m afraid the only thing I knew about Clifford was that he was missing in action in Burma, until my mother came across your web page this summer and we learned about the Chindits and Clifford’s fate. His medals were given to me by his brother Stanley (my grandfather) when I was a young child along with some other war memorabilia which I collected at that time. If you would like some photographs of his medals to add to your archive of valuable information, I am happy to send these to you. Keep up the good work and all the best.

Seen below are some of the photographs Nigel sent over to me. I would like to thank him for allowing me to add these images to Clifford Grundy's story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I was pleased recently, to receive the following email from Nigel Fitton:

Dear Steve,

Clifford Grundy was my great uncle on my mother's side of the family. I’m afraid the only thing I knew about Clifford was that he was missing in action in Burma, until my mother came across your web page this summer and we learned about the Chindits and Clifford’s fate. His medals were given to me by his brother Stanley (my grandfather) when I was a young child along with some other war memorabilia which I collected at that time. If you would like some photographs of his medals to add to your archive of valuable information, I am happy to send these to you. Keep up the good work and all the best.

Seen below are some of the photographs Nigel sent over to me. I would like to thank him for allowing me to add these images to Clifford Grundy's story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 16/11/2018.

I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Karen Fazackerley, the great niece of Clifford Grundy.

Hi Steve, I went to visit the family gravestone in Heywood Cemetery, near Rochdale, ahead of Remembrance Sunday. Clifford’s body isn’t there of course as it was never found, but the family wanted his name on the gravestone so they had somewhere to visit. I took a photograph of the stone as an update for the website. Speak soon and thank you for all your continued research, it means a lot to us all.

I was delighted to receive the following email contact from Karen Fazackerley, the great niece of Clifford Grundy.

Hi Steve, I went to visit the family gravestone in Heywood Cemetery, near Rochdale, ahead of Remembrance Sunday. Clifford’s body isn’t there of course as it was never found, but the family wanted his name on the gravestone so they had somewhere to visit. I took a photograph of the stone as an update for the website. Speak soon and thank you for all your continued research, it means a lot to us all.

Copyright © Frank Lea and Steve Fogden 2011.