Captain George Henry Astell MC

Cap Badge of the Burma Rifles.

Cap Badge of the Burma Rifles.

George Henry Astell was born on the 17th May 1910, at Hoylake, a seaside town within the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral in Merseyside. Not much is known about his early or school life, but I do know that he travelled to Burma several years before the Japanese invasion of that country in January 1942. George went to Burma to take up a position with The Steel Brothers Burma Trading Company, acting as a merchant in their Rice Department.

One of George Astell's contemporaries at Steel Brothers was Harold Braund, and it is from Harold's book, Distinctly I Remember, that much of the information in regards to George's early years in Burma is taken. The two men first met in November 1940, when they both arrived, although independently at the Alexandra Barracks in the hill station town of Maymyo. Both George and Harold had decided to offer up their services to the military, as the likelihood of a Japanese invasion became more and more apparent.

On the 21st November 1940, they became Privates of the Line in the Militia Company of the 2nd Battalion, the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. Professional men, regardless of their position in civil life, were expected to learn the basics of Army discipline at the level of private, even though their time at this rank would predictably be short.

George and Harold shared a room together at 'Ingleston', a large property maintained by the Forestry Department of Steel Brothers at the time. Both men enjoyed their time at the hill station town, taking advantage of the outdoor lifestyle, including a host of sporting activities and membership of the famous and exclusive Maymyo Club. Harold Braund makes mention of the club at Maymyo and the early days of their coming to terms with Army life in his book:

While we were yet civilians, George and I established our membership of the Maymyo Club, within the holy precincts of which no private soldier normally could hope to seek a drink. There had in fact been no little discussion at the committee level with regard to the continuing eligibility or otherwise of privates of the Militia Company who might already be members. Fortunately reason, as we saw it, had prevailed.

George and I reported together at the Militia Company's guard room on what we soon found was to be no empty formality. I was impressed from the start by the complete indifference shown by the Warrant Officers and N.C.O.s at an intake so far removed from what must have been their normal experience. Managers, chartered accountants, engineers, civil servants—we were just one more bunch of `bleedin recruits' to be made men of as quickly and as irrevocably as possible. Any show of familiarity or hint of patronage was rounded on with stentorian bellows of 'jump to it' or 'stand to attention when talking to me'—and God help the fool who assumed that this treatment was just an act and invited a second dose!

Soon we were blundering around with arms full of equipment and bedding; and with rifles, and anything else that could be suspended, hanging round our necks; and with Company Sergeant-Major Guest colourfully reminding us that we weren't in a 'carpeted bloody office' now. Having found our way to 'A' Platoon's barrack, we received from Corporal Butcher a quick-fire demonstration of how to make up a bed, un-make a bed and then make up a bed again; next we learnt how to stow our equipment in cubic capacity half of what was required; then we received instruction on how to clean rifles and equipment; and finally on how to spring-clean the barrack daily.

After what might be recognised by any who have served as initial training, the new recruits went on to perform tactical manoeuvres and other such drills, executing these whilst in the jungle scrubland that surrounds Maymyo. George Astell's love of outdoor activities, especially golf, tennis and cricket, led to his selection for the Militia's Cricket team and a place alongside Harold Braund on an eight day tour of the oilfields at Yenangyaung in December 1940.

Having borrowed a suitable vehicle, Harold, George and two other members of the team packed their kit and set off towards Mount Popa. Here disaster struck, when their truck, whilst descending a steep hill, lost control and left the road. Fortunately for the occupants, the vehicle came to rest, although upside down, supported on either side by a dry nullah or ditch. Apart from being somewhat shaken and suffering from minor cuts and bruises, no one was seriously hurt. For accuracies sake I should report that in the first match against the Oilfield's Eleven, George and Harold shared a very important partnership, with Astell scoring a commendable 126 runs in the match.

George Astell and Harold Braund passed out from the Militia Company ranks in early 1941, with both gentlemen taking up places in the Officer Cadet Training Unit at Maymyo almost immediately afterwards. It would be from the O.C.T.U. that George would receive his commission on the 28th April 1941 into the Burma Rifles, passing out as 2nd Lieutenant and with the Army number 189598. Harold Braund would go on to serve with distinction in the Chin Hills Levies, fighting the Japanese close to the Indian border state of Assam.

By October 1941, George Astell was given the War Substantive Rank of Lieutenant, and it was whilst holding this rank that he became part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and commenced training for the first Chindit expedition.

One of George Astell's contemporaries at Steel Brothers was Harold Braund, and it is from Harold's book, Distinctly I Remember, that much of the information in regards to George's early years in Burma is taken. The two men first met in November 1940, when they both arrived, although independently at the Alexandra Barracks in the hill station town of Maymyo. Both George and Harold had decided to offer up their services to the military, as the likelihood of a Japanese invasion became more and more apparent.

On the 21st November 1940, they became Privates of the Line in the Militia Company of the 2nd Battalion, the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. Professional men, regardless of their position in civil life, were expected to learn the basics of Army discipline at the level of private, even though their time at this rank would predictably be short.

George and Harold shared a room together at 'Ingleston', a large property maintained by the Forestry Department of Steel Brothers at the time. Both men enjoyed their time at the hill station town, taking advantage of the outdoor lifestyle, including a host of sporting activities and membership of the famous and exclusive Maymyo Club. Harold Braund makes mention of the club at Maymyo and the early days of their coming to terms with Army life in his book:

While we were yet civilians, George and I established our membership of the Maymyo Club, within the holy precincts of which no private soldier normally could hope to seek a drink. There had in fact been no little discussion at the committee level with regard to the continuing eligibility or otherwise of privates of the Militia Company who might already be members. Fortunately reason, as we saw it, had prevailed.

George and I reported together at the Militia Company's guard room on what we soon found was to be no empty formality. I was impressed from the start by the complete indifference shown by the Warrant Officers and N.C.O.s at an intake so far removed from what must have been their normal experience. Managers, chartered accountants, engineers, civil servants—we were just one more bunch of `bleedin recruits' to be made men of as quickly and as irrevocably as possible. Any show of familiarity or hint of patronage was rounded on with stentorian bellows of 'jump to it' or 'stand to attention when talking to me'—and God help the fool who assumed that this treatment was just an act and invited a second dose!

Soon we were blundering around with arms full of equipment and bedding; and with rifles, and anything else that could be suspended, hanging round our necks; and with Company Sergeant-Major Guest colourfully reminding us that we weren't in a 'carpeted bloody office' now. Having found our way to 'A' Platoon's barrack, we received from Corporal Butcher a quick-fire demonstration of how to make up a bed, un-make a bed and then make up a bed again; next we learnt how to stow our equipment in cubic capacity half of what was required; then we received instruction on how to clean rifles and equipment; and finally on how to spring-clean the barrack daily.

After what might be recognised by any who have served as initial training, the new recruits went on to perform tactical manoeuvres and other such drills, executing these whilst in the jungle scrubland that surrounds Maymyo. George Astell's love of outdoor activities, especially golf, tennis and cricket, led to his selection for the Militia's Cricket team and a place alongside Harold Braund on an eight day tour of the oilfields at Yenangyaung in December 1940.

Having borrowed a suitable vehicle, Harold, George and two other members of the team packed their kit and set off towards Mount Popa. Here disaster struck, when their truck, whilst descending a steep hill, lost control and left the road. Fortunately for the occupants, the vehicle came to rest, although upside down, supported on either side by a dry nullah or ditch. Apart from being somewhat shaken and suffering from minor cuts and bruises, no one was seriously hurt. For accuracies sake I should report that in the first match against the Oilfield's Eleven, George and Harold shared a very important partnership, with Astell scoring a commendable 126 runs in the match.

George Astell and Harold Braund passed out from the Militia Company ranks in early 1941, with both gentlemen taking up places in the Officer Cadet Training Unit at Maymyo almost immediately afterwards. It would be from the O.C.T.U. that George would receive his commission on the 28th April 1941 into the Burma Rifles, passing out as 2nd Lieutenant and with the Army number 189598. Harold Braund would go on to serve with distinction in the Chin Hills Levies, fighting the Japanese close to the Indian border state of Assam.

By October 1941, George Astell was given the War Substantive Rank of Lieutenant, and it was whilst holding this rank that he became part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and commenced training for the first Chindit expedition.

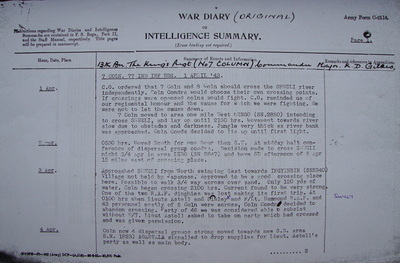

It has always been difficult to ascertain exactly which Chindit unit Lt. Astell belonged to in 1943. Some documents suggest he was attached to 7 Column under the overall command of Major Kenneth Gilkes. It seems more likely, as with so many of his fellow officers from the 2nd Battalion of the Burma Rifles, that George enjoyed somewhat of a free role, allowing him to move across the columns of Northern Group and provide assistance wherever it was needed at the time. This is borne out by the many mentions of him in the individual Chindit Column War diaries from that period.

The main responsibility of the Burma Rifle units on Operation Longcloth, was to seek out the local tribes people and assess their demeanour towards the new British presence in their country. According to the War diary of the 2nd Burma Rifles, this was Lt. Astell's first assignment, when on the 10th March 1943, he accompanied his commanding officer, Lt-Colonel Peter Buchanan, also of the 2nd Burma Rifles, on a reconnaissance mission to the railway town of Wuntho. The pair spent 24 hours at Wuntho, where they spoke to the local Headman and checked on recent enemy activity in the area.

The nature of Lt. Astell's roaming remit on Operation Longcloth is again borne out, when he next appears in the War diary of 8 Column, led by Major Walter Purcell Scott. On the 23rd March, the majority of Northern Group had gathered together to receive a large supply drop at a place called Baw, located a few miles west of the Shweli River. Wingate required that the village be locked down for the duration of the drop and that all exits from it be secured. Unfortunately this was not achieved in time and the drop zone area was compromised by a Japanese incursion.

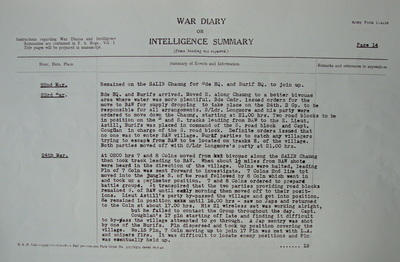

From the 8 Column diary:

"On 23rd March the Brigadier ordered the group to move toward the village of Baw for a large SD (Supply drop). Two road blocks were to be set up on the tracks leading north and south of the village. Lieut. Astell of the Burma Rifles to set the northern block and Captain Coughlan the southern block. Coughlan's platoon started off late and did not secure their block until first light. They had to go through the village itself where they were contacted by the Japanese. Tied down by enemy sniper fire and mortars the platoon became isolated from the main body. It took several hours of fierce fighting to extricate Coughlan from his position and relieve his unit. Good work here from Platoon 15, Column 7, led by Captain Petersen. The supply drop continued, but enemy interference hindered proceedings greatly."

The supply drop at Baw was called in order to fully re-equip the Chindit Brigade for their return journey to India. Wingate had ordered that the Chindit columns break down into smaller dispersal groups of 20-30 men, which were often led by a single officer and a member of the Burma Rifles acting as a guide. On the 3rd April, Lt. Astell was working within 7 Column as the unit prepared to cross the fast flowing and treacherous Shweli river. At this time a large section of 5 Column had arrived at the river after being separated from their own unit during an enemy ambush four days previously.

According to the 7 Column War diary, George Astell, along with Bill Smyly, the Animal Transport officer from 5 Column, managed to make the crossing in rubber dinghies and with a party of around 40 other men, continued their outward journey from Burma. The same diary, with an entry for the 2nd May 1943, confirms that:

Captain Astell and 45 Other Ranks (British, Gurkha and Burrif) went through on the 16th April. These dates are given from memory and should be considered as approximate.

It is understood that the majority of the men mentioned in the entry for May 2nd, had been heading for Fort Hertz the northernmost territory in Burma still occupied by Allied Forces. Sadly, not all the men from George Astell's party succeeded in exiting Burma in 1943. According to a witness statement given after the expedition by Corporal J. Carroll of the 13th King's, Pte. Harold Victor Cummings, one of the messenger dog handlers from 5 Column and Pte. Kenneth Dalrymple Webb also from 5 Column, had to be left in a friendly Kachin village, both were suffering from the effects of severe dysentery.

Update 16/01/2023.

Some confirmation of the above events appears in the pages of the book Wingate's Adventure, written by war correspondent Wilfred Burchett in 1944:

On the 3rd April (1943), Gilkes' column succeeded in getting 40 men across the Shweli. Unfortunately, the second boat was cast adrift after the power-rope severed and the boat was carried away downstream. The current swirled them across to the opposite bank, but a mile distant from the column. Gilkes then gave these men the option of waiting for the rest of the party to cross, or joining up wit the 40 men already over and making their own way out. They chose the latter and Gilkes arranged supply drops for them along the way. Most of the group, led by Lt. George Astell and Flight-Lieutenant Derek Hammond of the RAF came through to Fort Hertz and were then flown back to India from there.

Shown below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story, including some of the War diary extracts previously mentioned. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The main responsibility of the Burma Rifle units on Operation Longcloth, was to seek out the local tribes people and assess their demeanour towards the new British presence in their country. According to the War diary of the 2nd Burma Rifles, this was Lt. Astell's first assignment, when on the 10th March 1943, he accompanied his commanding officer, Lt-Colonel Peter Buchanan, also of the 2nd Burma Rifles, on a reconnaissance mission to the railway town of Wuntho. The pair spent 24 hours at Wuntho, where they spoke to the local Headman and checked on recent enemy activity in the area.

The nature of Lt. Astell's roaming remit on Operation Longcloth is again borne out, when he next appears in the War diary of 8 Column, led by Major Walter Purcell Scott. On the 23rd March, the majority of Northern Group had gathered together to receive a large supply drop at a place called Baw, located a few miles west of the Shweli River. Wingate required that the village be locked down for the duration of the drop and that all exits from it be secured. Unfortunately this was not achieved in time and the drop zone area was compromised by a Japanese incursion.

From the 8 Column diary:

"On 23rd March the Brigadier ordered the group to move toward the village of Baw for a large SD (Supply drop). Two road blocks were to be set up on the tracks leading north and south of the village. Lieut. Astell of the Burma Rifles to set the northern block and Captain Coughlan the southern block. Coughlan's platoon started off late and did not secure their block until first light. They had to go through the village itself where they were contacted by the Japanese. Tied down by enemy sniper fire and mortars the platoon became isolated from the main body. It took several hours of fierce fighting to extricate Coughlan from his position and relieve his unit. Good work here from Platoon 15, Column 7, led by Captain Petersen. The supply drop continued, but enemy interference hindered proceedings greatly."

The supply drop at Baw was called in order to fully re-equip the Chindit Brigade for their return journey to India. Wingate had ordered that the Chindit columns break down into smaller dispersal groups of 20-30 men, which were often led by a single officer and a member of the Burma Rifles acting as a guide. On the 3rd April, Lt. Astell was working within 7 Column as the unit prepared to cross the fast flowing and treacherous Shweli river. At this time a large section of 5 Column had arrived at the river after being separated from their own unit during an enemy ambush four days previously.

According to the 7 Column War diary, George Astell, along with Bill Smyly, the Animal Transport officer from 5 Column, managed to make the crossing in rubber dinghies and with a party of around 40 other men, continued their outward journey from Burma. The same diary, with an entry for the 2nd May 1943, confirms that:

Captain Astell and 45 Other Ranks (British, Gurkha and Burrif) went through on the 16th April. These dates are given from memory and should be considered as approximate.

It is understood that the majority of the men mentioned in the entry for May 2nd, had been heading for Fort Hertz the northernmost territory in Burma still occupied by Allied Forces. Sadly, not all the men from George Astell's party succeeded in exiting Burma in 1943. According to a witness statement given after the expedition by Corporal J. Carroll of the 13th King's, Pte. Harold Victor Cummings, one of the messenger dog handlers from 5 Column and Pte. Kenneth Dalrymple Webb also from 5 Column, had to be left in a friendly Kachin village, both were suffering from the effects of severe dysentery.

Update 16/01/2023.

Some confirmation of the above events appears in the pages of the book Wingate's Adventure, written by war correspondent Wilfred Burchett in 1944:

On the 3rd April (1943), Gilkes' column succeeded in getting 40 men across the Shweli. Unfortunately, the second boat was cast adrift after the power-rope severed and the boat was carried away downstream. The current swirled them across to the opposite bank, but a mile distant from the column. Gilkes then gave these men the option of waiting for the rest of the party to cross, or joining up wit the 40 men already over and making their own way out. They chose the latter and Gilkes arranged supply drops for them along the way. Most of the group, led by Lt. George Astell and Flight-Lieutenant Derek Hammond of the RAF came through to Fort Hertz and were then flown back to India from there.

Shown below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story, including some of the War diary extracts previously mentioned. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In 1943 Lieutenant George Astell had served with distinction. Although originally attached to 7 Column, he had moved freely around the various other units in Northern Group, assisting where he could with reconnaissance and scouting duties. His high level of performance and expertise on Operation Longcloth led to his immediate promotion through the ranks and the eventual command of Chindit Columns 45 and 54 during the second Chindit expedition in 1944. These two columns were originally part of the 16th British Infantry Brigade which was commanded by Bernard Fergusson and were made up from men of the 45th Reconnaissance Regiment, fighting as infantry in this instance. As in 1943, Astell was given a free reign and Columns 45 and 54 were used as floating patrols, seeking out and destroying enemy positions.

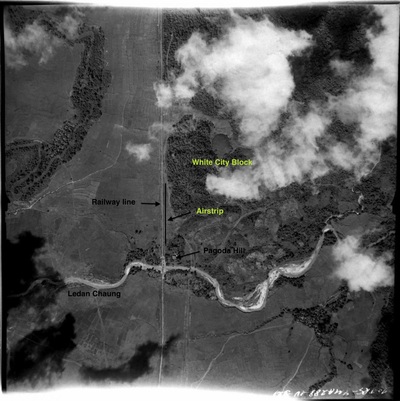

16th Brigade had been the only Chindit unit to march into Burma in 1944 and had a very tough time in doing so. This makes it all the more remarkable that Major Astell and his men had then been able to reach the outskirts of the famous Chindit stronghold of 'White City' by the third week of April. By doing so, Astell's columns had now come under the command of 77th Brigade, led by Brigadier Mike Calvert.

From his own book, Prisoners of Hope, Calvert recalled George Astell's arrival at White City:

After their famous march and subsequent actions, 16 Brigade were due for relief, and were about to be flown out. One of their battalions, which had had the misfortune during the attack on Indaw to go waterless for two days, had been reorganised and re-formed under Major Astell, who was now made Lieutenant-Colonel. He was the officer who had started the battle of Broadway. He was a pugnacious ball of fire, and was just what this battalion wanted.

They were to fight their last action under my command before they were flown out. After landing I met them and told them the position. I told them that I was very proud to have them under command, and that they were not going to cease being under my command until the Japanese in this area had been defeated. Then they could go home.

They were a good lot, these chaps, but they had been formed as a Divisional Reconnaissance Regiment in tanks and armoured cars, and they had at first taken hardly to being used as infantry. On the whole they were Devonshire men, and they had grown enormous patriarchal red beards during their long trek. General Wingate had ordered that beards could be worn. On the first campaign I grew a black bushy thing, with a list to the left. This time I was clean-shaven. Beards very definitely have their uses. If a man feels that he is tough, and looks tough, he will very often act tough.

It was for the engagement that ensued at 'White City' and his actions in commanding his forces during the fighting, that George Astell was awarded the Military Cross.

189598 Captain (temporary Major) George Henry Astell

Brigade-16th British Infantry

Division-3rd Indian.

Unit-The Burma Rifles

Date of Recommendation-25th June 1944.

Action for which recommended:

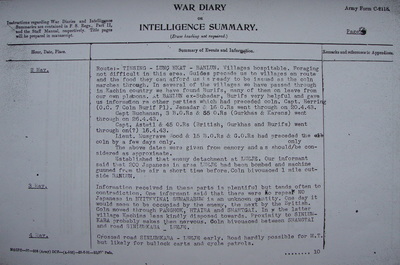

On 18th April 1944, two Columns under Major Astell, which had been taking part in heavy fighting during the previous three weeks, were moving towards a British block which had been established astride a road and railway at Henu in Burma.

At 0630 hours, the leading troops had reached the broad stream bed of the Mawlu Chaung, when heavy fire was opened from the far side. Fighting developed on all sides, the enemy proved to be for the most part in dug-in positions. It became apparent that the route of the columns had taken them right between two strongly defended localities, which the enemy was holding in great strength with heavy and medium machine guns and mortars. The ensuing action, which was exceedingly hard-fought, continued for over four hours, when Major Astell received orders to disengage and continue his march by another route. This disengagement was hotly opposed by the enemy, who were by this time all around the columns; but with great skill Major Astell succeeded in withdrawing the greater part of his wounded.

Although in this action he lost twenty percent of his strength, the number of Japanese killed is known to have been more than twice his own losses, and is believed to be much higher still. Although twelve out of fourteen mules were killed, all mortars and machine guns were successfully manhandled out of the battle, and carried many miles. The whole action was fought with great determination by all ranks, and reflected as much credit on them as if it had been crowned with success. The personal conduct of Major Astell throughout was magnificent. He exposed himself fearlessly where the fire was hottest, his exemplary courage and demeanour inspired his troops to great deeds, and won their admiration for ever.

Recommended by-Brigadier B.E. Fergusson DSO.

Commanding 16th Infantry Brigade.

Honour or Reward-Military Cross

Signed By-Major General W.D.A. Lentaigne

Commander 3rd Indian Division

Gazetted 02.01.1945

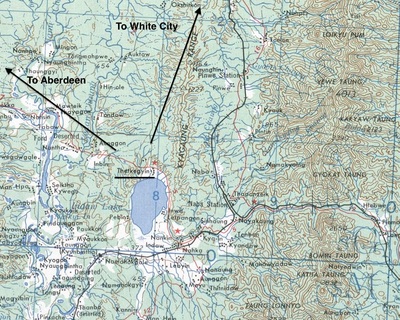

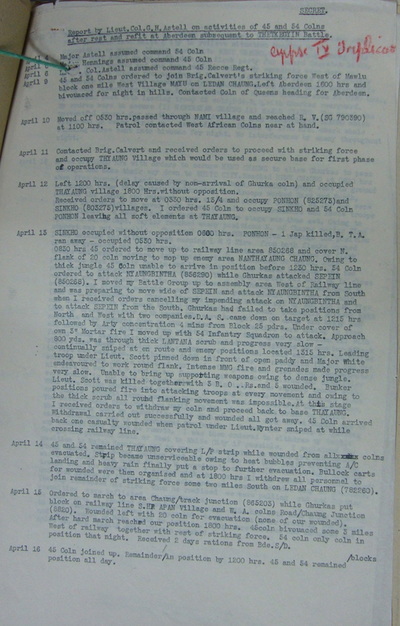

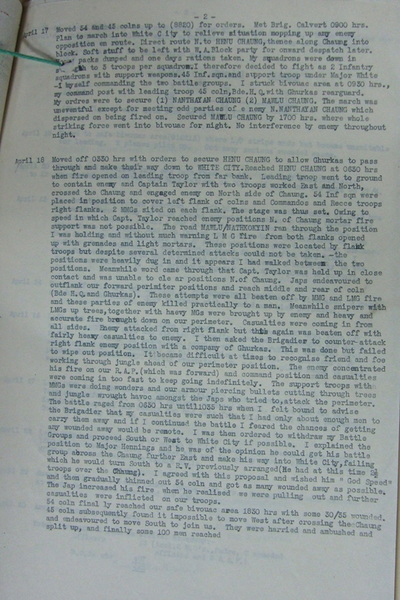

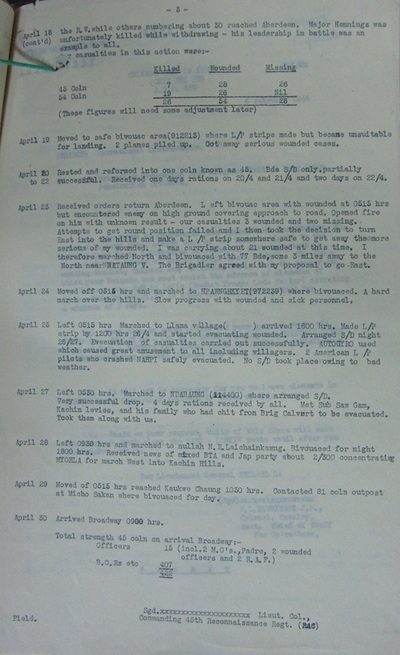

Seen below are some more images in relation to George Astell's involvement with the second Chindit expedition 1944. These include a three page report he constructed about his unit's actions around the White City Block in April that year and a map depicting the location of a previous battle at Thetkegyin, whilst still fighting with 16th Brigade. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

16th Brigade had been the only Chindit unit to march into Burma in 1944 and had a very tough time in doing so. This makes it all the more remarkable that Major Astell and his men had then been able to reach the outskirts of the famous Chindit stronghold of 'White City' by the third week of April. By doing so, Astell's columns had now come under the command of 77th Brigade, led by Brigadier Mike Calvert.

From his own book, Prisoners of Hope, Calvert recalled George Astell's arrival at White City:

After their famous march and subsequent actions, 16 Brigade were due for relief, and were about to be flown out. One of their battalions, which had had the misfortune during the attack on Indaw to go waterless for two days, had been reorganised and re-formed under Major Astell, who was now made Lieutenant-Colonel. He was the officer who had started the battle of Broadway. He was a pugnacious ball of fire, and was just what this battalion wanted.

They were to fight their last action under my command before they were flown out. After landing I met them and told them the position. I told them that I was very proud to have them under command, and that they were not going to cease being under my command until the Japanese in this area had been defeated. Then they could go home.

They were a good lot, these chaps, but they had been formed as a Divisional Reconnaissance Regiment in tanks and armoured cars, and they had at first taken hardly to being used as infantry. On the whole they were Devonshire men, and they had grown enormous patriarchal red beards during their long trek. General Wingate had ordered that beards could be worn. On the first campaign I grew a black bushy thing, with a list to the left. This time I was clean-shaven. Beards very definitely have their uses. If a man feels that he is tough, and looks tough, he will very often act tough.

It was for the engagement that ensued at 'White City' and his actions in commanding his forces during the fighting, that George Astell was awarded the Military Cross.

189598 Captain (temporary Major) George Henry Astell

Brigade-16th British Infantry

Division-3rd Indian.

Unit-The Burma Rifles

Date of Recommendation-25th June 1944.

Action for which recommended:

On 18th April 1944, two Columns under Major Astell, which had been taking part in heavy fighting during the previous three weeks, were moving towards a British block which had been established astride a road and railway at Henu in Burma.

At 0630 hours, the leading troops had reached the broad stream bed of the Mawlu Chaung, when heavy fire was opened from the far side. Fighting developed on all sides, the enemy proved to be for the most part in dug-in positions. It became apparent that the route of the columns had taken them right between two strongly defended localities, which the enemy was holding in great strength with heavy and medium machine guns and mortars. The ensuing action, which was exceedingly hard-fought, continued for over four hours, when Major Astell received orders to disengage and continue his march by another route. This disengagement was hotly opposed by the enemy, who were by this time all around the columns; but with great skill Major Astell succeeded in withdrawing the greater part of his wounded.

Although in this action he lost twenty percent of his strength, the number of Japanese killed is known to have been more than twice his own losses, and is believed to be much higher still. Although twelve out of fourteen mules were killed, all mortars and machine guns were successfully manhandled out of the battle, and carried many miles. The whole action was fought with great determination by all ranks, and reflected as much credit on them as if it had been crowned with success. The personal conduct of Major Astell throughout was magnificent. He exposed himself fearlessly where the fire was hottest, his exemplary courage and demeanour inspired his troops to great deeds, and won their admiration for ever.

Recommended by-Brigadier B.E. Fergusson DSO.

Commanding 16th Infantry Brigade.

Honour or Reward-Military Cross

Signed By-Major General W.D.A. Lentaigne

Commander 3rd Indian Division

Gazetted 02.01.1945

Seen below are some more images in relation to George Astell's involvement with the second Chindit expedition 1944. These include a three page report he constructed about his unit's actions around the White City Block in April that year and a map depicting the location of a previous battle at Thetkegyin, whilst still fighting with 16th Brigade. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Another officer from the 45 Reconnaissance Regiment present at the time George Astell assumed overall control of 45 & 54 Columns, was Captain Peter Taylor. He recalled:

"At Aberdeen (one of the Chindit airstrips on Operation Thursday) the C/O (Colonel R. Cumberlege) and Major Varcoe were both flown out sick. Major Ted Hennings took over and the much depleted columns were re-organised into two large companies. I was made commander of the mainly 45 Column personnel and Captain Jimmy White the remainder of the other (54 Column). Later Lt-Colonel George Astell of the Burma Rifles was appointed commander. He was not a regular soldier and his tactical sense was almost non-existent, but he was an exceptionally brave man and a great morale booster."

George Astell retained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel after Operation Thursday was closed. He then returned to India and was subsequently appointed as C/O to the newly formed 15th (Kings) Parachute Battalion in April 1945. George did not retain this command for long and by July Astell had given way to Major F.E. Templer of the Royal Ulster Rifles.

After the war George Astell returned to England in the first instance, but was much travelled thereafter. He returned to India with his wife Barbara in March 1949, presumably to continue his work with Steel Brothers. Another voyage from the port of Liverpool, aboard the Bibby Line ship Warwickshire in May 1952, saw George, Barbara and their two children, Rosemary Jeane and Nigel Hugh Astell, take up residence once more in Rangoon. According to the register of deaths for the United Kingdom, George Henry Astell sadly passed away in the last quarter of 1974, whilst living in Bromley, a town located in the English county of Kent.

Update 29/05/2023.

I was delighted to receive an email contact from Susan Hargreaves:

My husband is the history teacher at St Hugh's School. The school used to be located at Bickley in Kent, but suffered severe bomb damage during WW2 and moved to Faringdon in Oxfordshire, where it has remained. A few of the school magazines from about 1908-22 survive and a few years ago we did a big project to look into the school's Old Boys who fought and died in WW1. Recently an old card index was found in an attic which contains some very basic information about many of the boys who attended the school between 1905 and about 1968. Amongst the index were cards for George Astell and his twin brother, Carleton William Astell. I can tell you that both attended St. Hugh's School for about two years, before moving on to Tonbridge School.

"At Aberdeen (one of the Chindit airstrips on Operation Thursday) the C/O (Colonel R. Cumberlege) and Major Varcoe were both flown out sick. Major Ted Hennings took over and the much depleted columns were re-organised into two large companies. I was made commander of the mainly 45 Column personnel and Captain Jimmy White the remainder of the other (54 Column). Later Lt-Colonel George Astell of the Burma Rifles was appointed commander. He was not a regular soldier and his tactical sense was almost non-existent, but he was an exceptionally brave man and a great morale booster."

George Astell retained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel after Operation Thursday was closed. He then returned to India and was subsequently appointed as C/O to the newly formed 15th (Kings) Parachute Battalion in April 1945. George did not retain this command for long and by July Astell had given way to Major F.E. Templer of the Royal Ulster Rifles.

After the war George Astell returned to England in the first instance, but was much travelled thereafter. He returned to India with his wife Barbara in March 1949, presumably to continue his work with Steel Brothers. Another voyage from the port of Liverpool, aboard the Bibby Line ship Warwickshire in May 1952, saw George, Barbara and their two children, Rosemary Jeane and Nigel Hugh Astell, take up residence once more in Rangoon. According to the register of deaths for the United Kingdom, George Henry Astell sadly passed away in the last quarter of 1974, whilst living in Bromley, a town located in the English county of Kent.

Update 29/05/2023.

I was delighted to receive an email contact from Susan Hargreaves:

My husband is the history teacher at St Hugh's School. The school used to be located at Bickley in Kent, but suffered severe bomb damage during WW2 and moved to Faringdon in Oxfordshire, where it has remained. A few of the school magazines from about 1908-22 survive and a few years ago we did a big project to look into the school's Old Boys who fought and died in WW1. Recently an old card index was found in an attic which contains some very basic information about many of the boys who attended the school between 1905 and about 1968. Amongst the index were cards for George Astell and his twin brother, Carleton William Astell. I can tell you that both attended St. Hugh's School for about two years, before moving on to Tonbridge School.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, July 2016.