Jim Tomlinson, Column 8 Commando

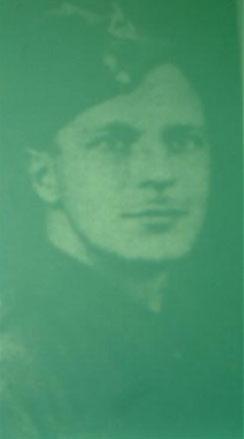

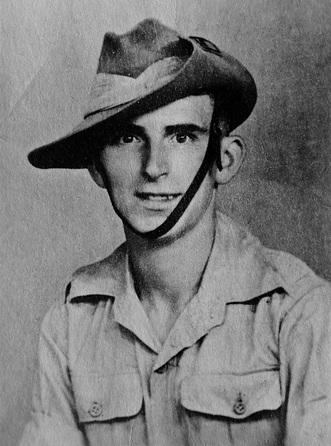

Pte. Jim Tomlinson in his Chindit bush hat.

Pte. Jim Tomlinson in his Chindit bush hat.

In early October this year (2013) I was busy with some on line research, looking for new leads in regard to surviving veterans from Operation Longcloth. That same evening I stumbled across an obituary in the Middlesborough Evening Gazette dated 31st May, it was for a man called Jim Tomlinson.

I recognised the name immediately as one of my Chindit prisoner's of war. Excited by my new discovery I read on:

Farewell to hero Jim Tomlinson: One of the last-surviving Chindit Special Forces soldiers dies at 91

Jim Tomlinson heroically took part in the Chindit Special Forces' most famous mission, Operation Longcloth, under Major General Orde Wingate. Jim Tomlinson, one of Britain’s last surviving Chindit Special Forces soldiers and a hero who will go down in history, has died aged 91.

The Chindits were a crack force similar to the SAS, fighting with great courage in Burma in the Second World War, operating deep behind Japanese lines, blowing up railway tracks and bridges and ambushing the enemy.

But they paid a heavy price with hundreds killed in action, or caught and tortured by the Japanese, imprisoned and starved to death, or dying of disease and malnutrition.

Jim, heroically took part in the force’s most famous mission, Operation Longcloth, under Major General Orde Wingate.

He also survived a hair-raising escape, hiding within feet of Japanese soldiers, intent on beheading him to make him an example to others.

A force of 3,000 Chindits caused havoc behind the lines in Burma in 1943, but many like Jim were surrounded and captured and imprisoned. The dwindling survivors suffered great cruelty for two years.

In their jungle prison camp, Jim’s commanding officer, Colonel Macdonald, got wind they were to be shipped to Japan as slave labourers - and certain death. MacDonald, Jim and a few others bravely escaped at last from their tormentor guards, hiding in a pagoda. Indian Army soldiers attacked the Japanese and liberated them at the last minute, but Jim told his family later they would have been beheaded if caught.

His niece, Diana, told how Jim bore whip marks on his back, inflicted by the brutal guards. Another sadistic soldier smashed a rifle butt into his groin, meaning he could never father children. He never married.

Diana said proudly:

“He was wonderful, always happy and joking. He was a great hero and much loved. A true gentleman.”

Her brother and Jim’s nephew Howard Rutland, said:

“He was one of a handful of Chindits left alive in Britain - one of the greatest heroes to come out of Teesside.”

Jim died in James Cook University Hospital on May 19th after suffering several strokes. He was born in Haddon Street in the Acklam district of Middlesbrough and excelled at sport at St. John’s Primary School and later was a handy boxer. He was tough and independent and at war’s outbreak in 1939, aged 18, volunteered for the Durham Light Infantry and later for the crack 142 Commando, before joining the Chindits.

Howard said: “He was a strong swimmer. With the Chindits in Burma he blew up bridges and ammo dumps. On one bridge, a pipe bomb fuse hadn’t worked and he ran back through heavy shelling to relight it. They faced a cruel and ferocious enemy in the Japanese.”

Diana also said that, after capture and against overwhelming odds, Jim and a comrade survived a forced death march without food by snatching bits of wild spinach.

She continued:

“This stopped them starving to death. But they were tortured, beaten and pistol whipped and ended up wearing just a loin cloth in the prison camp, which was bare huts on bamboo poles. They were told to write letters home to their mothers. Then the Japanese burned them all and taunted them that they would never see home again."

“That was the first of many horrors he bore bravely. But others lost their minds. After being captured and taken to Rangoon, most of his comrades died from ill treatment and disease. As well as his whipping scars, he had bullet wounds on his head and shrapnel in his leg. He was literally the man the Japanese couldn’t kill, but was like a skeleton when he eventually escaped - just six stones and he lost all his teeth through malnutrition.”

He was shipped home to recuperate, which took many months. After the war, he returned to his job as a master plasterer. Well known at South Gare (an area of reclaimed land near the mouth of the River Tees), where he had a hut and boat at Paddy’s Hole for 60 years, Jim proudly wore his Burma Star - the medal awarded to those who served in this key campaign of World War Two.

A private family funeral was held at St Bede’s Chapel, Middlesbrough Crematorium, yesterday.

My thanks go to the Gazette Live for allowing me to use some of the obituary in this story. The article was written by journalist Mike Morgan.

Having read through the obituary and seen the many images relating to Jim and his life which supplemented the story, I decided to leave this message at the foot of the on line page:

"I'm sorry to have missed Jim by such a short space of time. My name is Steve Fogden, my grandfather was also a Chindit, he died in Rangoon Jail. I have started a website about them all and I would dearly love to add Jim's story to the site, so that he could be alongside his old comrades. I have additional information about his time in Burma and some documents relating to his story. It would be wonderful to get in touch with his family."

Fortunately, it did not take too long to make contact with Jim's nephew, Howard, who was from the Acklam area of Middlesborough. Ironically, I had once spent an enjoyable evening in the Acklam Steel Workers Social Club as a guest of a close family friend who happened to be from Middlesborough. It is funny how things turn out!

Howard and I exchanged several emails, where I explained in more detail how Jim had became a Chindit in 1942.

As mentioned earlier he had enlisted into the Army and been posted in to the Durham Light Infantry, this could be confirmed by his Army Service number 4469363. It is most likely that, although he was to join the 13th King's as a reinforcement in 1942, he would have travelled to India still a soldier in the DLI and probably passed through the famous British Army Centre at Deolali.

Having joined the Chindits, Jim became part of the 142 Commando and trained in sabotage techniques, handling explosives and hand to hand combat. This unit of the 13th King's had a training camp at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. Their number had been made up from special personnel taken from the Bush Warfare School (Maymyo) and the 204 Military Mission, who had recently been fighting the Japanese in the border provinces of China.

In January 1943 as the men were preparing to enter Burma, Jim was placed into Chindit Column 8 under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott or 'Scottie' as he was known to his men. Major Scott, who was well loved by those he led handed the leadership of his Commando Platoon to a young fresh faced Lieutenant named Thomas Sprague. Lieutenant Sprague had originally served with the Herefords and had been newly promoted from the ranks after showing good promise during training.

I recognised the name immediately as one of my Chindit prisoner's of war. Excited by my new discovery I read on:

Farewell to hero Jim Tomlinson: One of the last-surviving Chindit Special Forces soldiers dies at 91

Jim Tomlinson heroically took part in the Chindit Special Forces' most famous mission, Operation Longcloth, under Major General Orde Wingate. Jim Tomlinson, one of Britain’s last surviving Chindit Special Forces soldiers and a hero who will go down in history, has died aged 91.

The Chindits were a crack force similar to the SAS, fighting with great courage in Burma in the Second World War, operating deep behind Japanese lines, blowing up railway tracks and bridges and ambushing the enemy.

But they paid a heavy price with hundreds killed in action, or caught and tortured by the Japanese, imprisoned and starved to death, or dying of disease and malnutrition.

Jim, heroically took part in the force’s most famous mission, Operation Longcloth, under Major General Orde Wingate.

He also survived a hair-raising escape, hiding within feet of Japanese soldiers, intent on beheading him to make him an example to others.

A force of 3,000 Chindits caused havoc behind the lines in Burma in 1943, but many like Jim were surrounded and captured and imprisoned. The dwindling survivors suffered great cruelty for two years.

In their jungle prison camp, Jim’s commanding officer, Colonel Macdonald, got wind they were to be shipped to Japan as slave labourers - and certain death. MacDonald, Jim and a few others bravely escaped at last from their tormentor guards, hiding in a pagoda. Indian Army soldiers attacked the Japanese and liberated them at the last minute, but Jim told his family later they would have been beheaded if caught.

His niece, Diana, told how Jim bore whip marks on his back, inflicted by the brutal guards. Another sadistic soldier smashed a rifle butt into his groin, meaning he could never father children. He never married.

Diana said proudly:

“He was wonderful, always happy and joking. He was a great hero and much loved. A true gentleman.”

Her brother and Jim’s nephew Howard Rutland, said:

“He was one of a handful of Chindits left alive in Britain - one of the greatest heroes to come out of Teesside.”

Jim died in James Cook University Hospital on May 19th after suffering several strokes. He was born in Haddon Street in the Acklam district of Middlesbrough and excelled at sport at St. John’s Primary School and later was a handy boxer. He was tough and independent and at war’s outbreak in 1939, aged 18, volunteered for the Durham Light Infantry and later for the crack 142 Commando, before joining the Chindits.

Howard said: “He was a strong swimmer. With the Chindits in Burma he blew up bridges and ammo dumps. On one bridge, a pipe bomb fuse hadn’t worked and he ran back through heavy shelling to relight it. They faced a cruel and ferocious enemy in the Japanese.”

Diana also said that, after capture and against overwhelming odds, Jim and a comrade survived a forced death march without food by snatching bits of wild spinach.

She continued:

“This stopped them starving to death. But they were tortured, beaten and pistol whipped and ended up wearing just a loin cloth in the prison camp, which was bare huts on bamboo poles. They were told to write letters home to their mothers. Then the Japanese burned them all and taunted them that they would never see home again."

“That was the first of many horrors he bore bravely. But others lost their minds. After being captured and taken to Rangoon, most of his comrades died from ill treatment and disease. As well as his whipping scars, he had bullet wounds on his head and shrapnel in his leg. He was literally the man the Japanese couldn’t kill, but was like a skeleton when he eventually escaped - just six stones and he lost all his teeth through malnutrition.”

He was shipped home to recuperate, which took many months. After the war, he returned to his job as a master plasterer. Well known at South Gare (an area of reclaimed land near the mouth of the River Tees), where he had a hut and boat at Paddy’s Hole for 60 years, Jim proudly wore his Burma Star - the medal awarded to those who served in this key campaign of World War Two.

A private family funeral was held at St Bede’s Chapel, Middlesbrough Crematorium, yesterday.

My thanks go to the Gazette Live for allowing me to use some of the obituary in this story. The article was written by journalist Mike Morgan.

Having read through the obituary and seen the many images relating to Jim and his life which supplemented the story, I decided to leave this message at the foot of the on line page:

"I'm sorry to have missed Jim by such a short space of time. My name is Steve Fogden, my grandfather was also a Chindit, he died in Rangoon Jail. I have started a website about them all and I would dearly love to add Jim's story to the site, so that he could be alongside his old comrades. I have additional information about his time in Burma and some documents relating to his story. It would be wonderful to get in touch with his family."

Fortunately, it did not take too long to make contact with Jim's nephew, Howard, who was from the Acklam area of Middlesborough. Ironically, I had once spent an enjoyable evening in the Acklam Steel Workers Social Club as a guest of a close family friend who happened to be from Middlesborough. It is funny how things turn out!

Howard and I exchanged several emails, where I explained in more detail how Jim had became a Chindit in 1942.

As mentioned earlier he had enlisted into the Army and been posted in to the Durham Light Infantry, this could be confirmed by his Army Service number 4469363. It is most likely that, although he was to join the 13th King's as a reinforcement in 1942, he would have travelled to India still a soldier in the DLI and probably passed through the famous British Army Centre at Deolali.

Having joined the Chindits, Jim became part of the 142 Commando and trained in sabotage techniques, handling explosives and hand to hand combat. This unit of the 13th King's had a training camp at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India. Their number had been made up from special personnel taken from the Bush Warfare School (Maymyo) and the 204 Military Mission, who had recently been fighting the Japanese in the border provinces of China.

In January 1943 as the men were preparing to enter Burma, Jim was placed into Chindit Column 8 under the command of Major Walter Purcell Scott or 'Scottie' as he was known to his men. Major Scott, who was well loved by those he led handed the leadership of his Commando Platoon to a young fresh faced Lieutenant named Thomas Sprague. Lieutenant Sprague had originally served with the Herefords and had been newly promoted from the ranks after showing good promise during training.

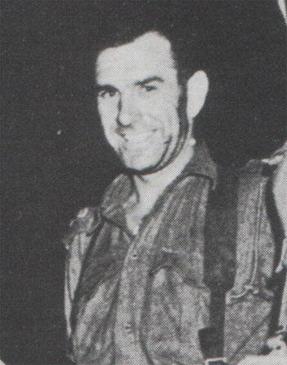

Major Walter Purcell Scott, Column 8 Commander.

Major Walter Purcell Scott, Column 8 Commander.

Column 8 crossed the Chindwin River in mid-February 1943, they travelled around Burma during the early weeks of the operation in close proximity to Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters, often protecting him against possible enemy attacks.

One of the columns major clashes with the enemy happened at a place called Pinlebu. Here is an extract taken from the Column 8 War Diary for that period of time:

“ 4th and 5th March: column moved into the area around Pinlebu, there were said to be 600-1000 enemy troops in this locality. The Burma Rifle Officers had spoken to a native of the area, he turned out to be a Japanese spy and was shot. Water parties were sent out to replenish supplies, these units were engaged by enemy patrols but most managed to disengage and return to the main body”.

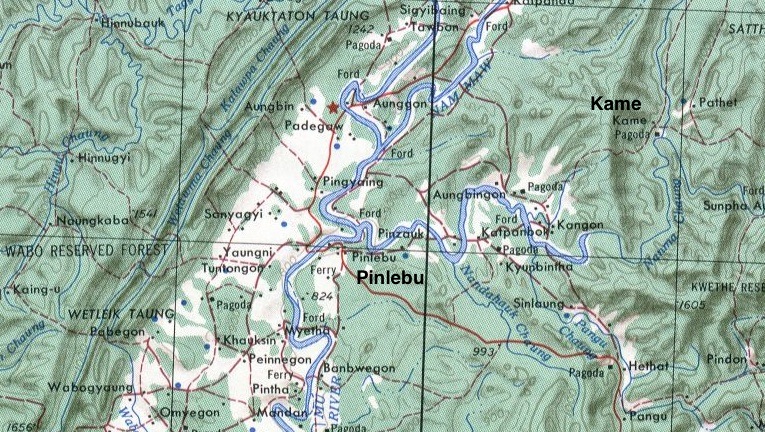

More minor clashes with the Japanese were incurred late on 5th March, the column moved to the agreed rendezvous on the Pinlebu-Kame Road (see map below). The party halted one mile north of Kame and settled down for the night. Their position was chosen by Major Scott and units were deployed to prevent any Japanese movement toward Pinlebu from this direction.

“At first light on the 6th March, the Sabotage Squad led by Lieutenant Sprague and 16 Platoon set out toward Kame to secure the road block. At about 1100 hours Sprague’s men were attacked by the Japanese from all sides, he called dispersal in an attempt to extract his men, it was here that Lieutenant Callaghan was shot and killed”.

“ At 1600 hours the whole column moved away toward the Supply drop rendezvous area.”

So as you can see the situation was very confused, with enemy troops engaging the column positions on several occasions over that three day period. The main purpose for Scott's men was to protect the road and keep the Japanese from interfering with the Brigade's latest supply drop.

Another good source of information from this period can be found in the book ‘Wingate Adventure’ by WG. Burchett. From pages 72, 73 and 74 comes this paraphrased account:

"As No. 2 Group neared Pinlebu, Gilkes (Column 7 Commander) and Brigade HQ's moved east to arrange a Supply drop zone, whilst Major Scott’s Column took up defensive positions around Pinlebu.

On the 5th, Scott occupied a village (Kame) two and a half miles from Pinlebu and sent his patrols out covering all directions.

The Japanese were everywhere, but usually betrayed their positions early by blazing away at the slightest movement or noise.

The minor battle lasted all day and into the night, dispersal was then called and the column moved away. Early on the 6th March, Scott set up roadblocks leading east and north out of Pinlebu, the supply drop continued unhindered.

Scott had no sooner closed the roadblocks and was preparing to move off, when a Japanese patrol opened fire on one of the furthest placed groups. A brisk thirty-minute battle ensued, leaving six men killed or badly wounded. Column 8 withdrew to safer ground.

For the loss of six men the column had held up the enemy for over 24 hours, covering Calvert and Fergusson’s dash to the railway and allowing HQ to secure a vital supply drop."

One of the columns major clashes with the enemy happened at a place called Pinlebu. Here is an extract taken from the Column 8 War Diary for that period of time:

“ 4th and 5th March: column moved into the area around Pinlebu, there were said to be 600-1000 enemy troops in this locality. The Burma Rifle Officers had spoken to a native of the area, he turned out to be a Japanese spy and was shot. Water parties were sent out to replenish supplies, these units were engaged by enemy patrols but most managed to disengage and return to the main body”.

More minor clashes with the Japanese were incurred late on 5th March, the column moved to the agreed rendezvous on the Pinlebu-Kame Road (see map below). The party halted one mile north of Kame and settled down for the night. Their position was chosen by Major Scott and units were deployed to prevent any Japanese movement toward Pinlebu from this direction.

“At first light on the 6th March, the Sabotage Squad led by Lieutenant Sprague and 16 Platoon set out toward Kame to secure the road block. At about 1100 hours Sprague’s men were attacked by the Japanese from all sides, he called dispersal in an attempt to extract his men, it was here that Lieutenant Callaghan was shot and killed”.

“ At 1600 hours the whole column moved away toward the Supply drop rendezvous area.”

So as you can see the situation was very confused, with enemy troops engaging the column positions on several occasions over that three day period. The main purpose for Scott's men was to protect the road and keep the Japanese from interfering with the Brigade's latest supply drop.

Another good source of information from this period can be found in the book ‘Wingate Adventure’ by WG. Burchett. From pages 72, 73 and 74 comes this paraphrased account:

"As No. 2 Group neared Pinlebu, Gilkes (Column 7 Commander) and Brigade HQ's moved east to arrange a Supply drop zone, whilst Major Scott’s Column took up defensive positions around Pinlebu.

On the 5th, Scott occupied a village (Kame) two and a half miles from Pinlebu and sent his patrols out covering all directions.

The Japanese were everywhere, but usually betrayed their positions early by blazing away at the slightest movement or noise.

The minor battle lasted all day and into the night, dispersal was then called and the column moved away. Early on the 6th March, Scott set up roadblocks leading east and north out of Pinlebu, the supply drop continued unhindered.

Scott had no sooner closed the roadblocks and was preparing to move off, when a Japanese patrol opened fire on one of the furthest placed groups. A brisk thirty-minute battle ensued, leaving six men killed or badly wounded. Column 8 withdrew to safer ground.

For the loss of six men the column had held up the enemy for over 24 hours, covering Calvert and Fergusson’s dash to the railway and allowing HQ to secure a vital supply drop."

I thought it would be of some interest to this story to read Wingate's own account and view of the action around Pinlebu in early March 1943. Here is a condensed, paraphrased summary of his appraisal:

"I sent Column 8 off to Pinlebu to make the enemy believe that this was our main objective. In this we were successful. Intelligence had told us that the Japanese Garrison in the town was at double Company strength, with two more stationed at Wuntho. Allied bombing called in by our RAF Officers on the 4th March had been effective and the Japanese dispersed widely in organised defences covering several square miles.

Column 8 succeeded in attracting a good deal of attention and at one point even carried out a dispersal manoeuvre. The re-forming afterwards was also successful but for the loss of some of our Other Ranks. I ordered the continued ambush of tracks leading both North and East of Pinlebu to cover our main objective, a large Supply Drop planned for the 6th.

It was clear to me from these engagements with the enemy, that Column 8 had much to learn in the way of ordinary Infantry tactics and positioning, in this respect they were inferior to the Japanese. Nevertheless, they were superior to the enemy in handling their nerve, movement through the jungle and the power of surprise.

Lieut. Colonel Cooke took charge of the supply dropping on the 6th. While it was proceeding, the sounds of Mortar and Machine Gun fire could be heard from the direction of Pinlebu as Column 8 went about their business. Their action had confused the Japanese and the enemies fear of engaging the column in the surrounding jungle had left the supply drop unmolested."

So, as you can clearly see, Jim and his comrades from 142 Commando had been involved in their fair share of action during the early stages of the fledgling Chindit Operation.

We now move on some four weeks to the beginning of April. The men of Column 8 had been marching inside Burma for over six weeks, the effects of poor amounts of rations and this physical exertion, combined with the emergence of tropical diseases such as malaria, began to take its toll. Wingate then received a message from General India Command, ordering the Brigade to return to India immediately.

On the 29th March Wingate and Columns 7 and 8 reached the banks of the Irrawaddy River near the town of Inywa. The first platoon of Chindits was sent across the river to form a protective bridgehead on the western banks. Disaster struck when a large patrol of Japanese arrived on that side of the river and opened fire on the lead boats with their mortars and machine guns. Many men were killed. Wingate abandoned the now opposed crossing and the Chindit groups melted away into the nearby jungle.

Eventually Columns 7 and 8 moved away from the area and headed in an easterly direction towards the River Shweli. The two units split up on the 1st April as they both searched for a means to cross the fast flowing river. Column 8 made several unsuccessful attempts at crossing the river using power ropes and dinghies, before finally fording the Shweli late on the 3rd April.

The next ten days were tortuous for the column, as they marched and then counter-marched across the large expanses of Burmese forest. They suffered several casualties during minor engagements with enemy patrols, then on the 14th April, Scott called a halt and the men set up a temporary camp at a rest house near the village of Misan. The idea was to rest up for the night and arrange by column radio a fresh supply drop for the 15th or 16th. The column leaders decided that it was also time to break the unit up into smaller dispersal parties of around 25-30 men. Lieutenant Sprague, Jim Tomlinson and his comrades from 142 Commando were placed into a group with the Gurkha mule drivers led by Lieutenant Dominic Neill.

"I sent Column 8 off to Pinlebu to make the enemy believe that this was our main objective. In this we were successful. Intelligence had told us that the Japanese Garrison in the town was at double Company strength, with two more stationed at Wuntho. Allied bombing called in by our RAF Officers on the 4th March had been effective and the Japanese dispersed widely in organised defences covering several square miles.

Column 8 succeeded in attracting a good deal of attention and at one point even carried out a dispersal manoeuvre. The re-forming afterwards was also successful but for the loss of some of our Other Ranks. I ordered the continued ambush of tracks leading both North and East of Pinlebu to cover our main objective, a large Supply Drop planned for the 6th.

It was clear to me from these engagements with the enemy, that Column 8 had much to learn in the way of ordinary Infantry tactics and positioning, in this respect they were inferior to the Japanese. Nevertheless, they were superior to the enemy in handling their nerve, movement through the jungle and the power of surprise.

Lieut. Colonel Cooke took charge of the supply dropping on the 6th. While it was proceeding, the sounds of Mortar and Machine Gun fire could be heard from the direction of Pinlebu as Column 8 went about their business. Their action had confused the Japanese and the enemies fear of engaging the column in the surrounding jungle had left the supply drop unmolested."

So, as you can clearly see, Jim and his comrades from 142 Commando had been involved in their fair share of action during the early stages of the fledgling Chindit Operation.

We now move on some four weeks to the beginning of April. The men of Column 8 had been marching inside Burma for over six weeks, the effects of poor amounts of rations and this physical exertion, combined with the emergence of tropical diseases such as malaria, began to take its toll. Wingate then received a message from General India Command, ordering the Brigade to return to India immediately.

On the 29th March Wingate and Columns 7 and 8 reached the banks of the Irrawaddy River near the town of Inywa. The first platoon of Chindits was sent across the river to form a protective bridgehead on the western banks. Disaster struck when a large patrol of Japanese arrived on that side of the river and opened fire on the lead boats with their mortars and machine guns. Many men were killed. Wingate abandoned the now opposed crossing and the Chindit groups melted away into the nearby jungle.

Eventually Columns 7 and 8 moved away from the area and headed in an easterly direction towards the River Shweli. The two units split up on the 1st April as they both searched for a means to cross the fast flowing river. Column 8 made several unsuccessful attempts at crossing the river using power ropes and dinghies, before finally fording the Shweli late on the 3rd April.

The next ten days were tortuous for the column, as they marched and then counter-marched across the large expanses of Burmese forest. They suffered several casualties during minor engagements with enemy patrols, then on the 14th April, Scott called a halt and the men set up a temporary camp at a rest house near the village of Misan. The idea was to rest up for the night and arrange by column radio a fresh supply drop for the 15th or 16th. The column leaders decided that it was also time to break the unit up into smaller dispersal parties of around 25-30 men. Lieutenant Sprague, Jim Tomlinson and his comrades from 142 Commando were placed into a group with the Gurkha mule drivers led by Lieutenant Dominic Neill.

Lieutenant Dominic Neill of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles.

Lieutenant Dominic Neill of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles.

From this point we pick up the story of the small dispersal party containing the 142 Commandos and Lieutenant Neill's Gurkhas. Dominic Neill put pen to paper and recorded his time in 1943; from his short journal entitled 'One More River', here is his account of the crucial fortnight following the failed crossing of the Irrawaddy River.

The following day we received our air drop and then, for the first time, I was invited to join Scotty's '0' (orders) Group. It was indeed true that all columns of the Brigade were to be split up into much smaller groups and were to find their own way back to India, or China, the latter country being the nearest to us now.

Our one radio in the column would go with Scotty's group after we had dispersed — lucky for some! Wingate had now played us his final ace card. He had taken us deep into enemy-held territory and now we were required to return to safety in penny-packets, on our own and without any communications, thus condemning us to receive no further administrative or tactical air support.

In my judgement, we should have forced a crossing of the Irrawaddy when we had the chance and when we were in considerable strength. We would of course have taken casualties during the crossing, but these, I believe, would have been far fewer than those ultimately suffered by the Brigade as a whole, during the retreat we were about to carry out in small groups, without any inter-linking support of any kind.

I asked Lieutenant Tag Sprague, who commanded the Column's Commando/demolition section from 142 Company, if he and his small band of Commandos might like to join my Gurkhas and I for the return journey. Much to my pleasure and relief he agreed readily to my suggestion. He was four years older than me and had fought in Norway with 1 Commando. We have remained friends to this day.

Scotty gave us the map co-ordinates of a number of Drop Zones to the north where the RAF would be dropping supplies and to which we could go if we required further supplies during our withdrawal. He then issued us with maps and compasses, the first time I had been given such navigation aids. Now in the middle of a wilderness, with the same poor knowledge of map reading as before, I was being required to take my small group of ill-trained young Gurkhas over hundreds of miles of inhospitable terrain and through the whole of the Japanese 33rd Division, who were already searching for us with the intention of preventing our escape.

It is perhaps not surprising that I should have been so critical of Wingate's training methods and battle tactics. So, in the early part of April, Tag and I, with my fifty-two Gurkhas and his dozen or so BORs (British Other Ranks), split from 8 Column to begin our long march back to the Chindwin. We crammed ten days' bulky rations into our packs, the only supplies we would have unless we could buy some from villages on the way.

I was given 400 silver rupees for this purpose and I put them into one of the two basic pouches on my web belt. They weighed a ton, as did my pack, and I nearly fell over as I put it on. The only way I could stand up straight was to place my rifle butt on the ground behind me and poke the muzzle underneath the pack to take the weight. But carry it I did. A man's pack from that day on carried very literally his lifeblood and it was never, ever to be discarded.

Tag (Lieuteneant Sprague's nickname taken from his intitials) and I decided to march in a northerly direction to try to recross the vast Irrawaddy somewhere along its stretch where it flows east-west between the big villages of Bhamo and Katha. We would have to avoid Shwegu though, as that village contained a Jap garrison.

Every escape group had been given a few soldiers from Nigel Whitehead's Platoon of 2 Burma Rifles and we were delighted to find that we had Naik Tun Tin and four Riflemen attached to us. An outstanding NCO, Tun Tin and his men were Karens and he had been educated at a mission school. He was very intelligent and spoke excellent English and was to prove to be of tremendous assistance to us. Sadly, however, we were soon parted from him.

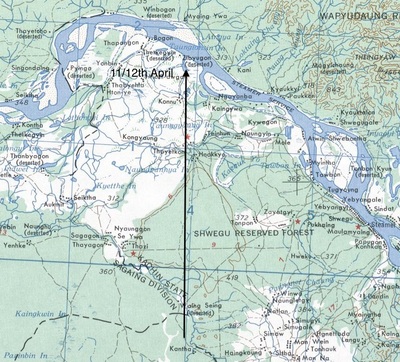

It took four days to reach the Irrawaddy, near the village of Zibyugon. The sal trees were in blossom; they smelt like a wet flannel and whenever I scent such a smell my mind goes back to that day at Zibyugon, and our brief stay there while we searched for boats to take us across the river. Tun Tin and two of his men changed into civilian clothes and went into Zibyugon to try to find boats to carry us across. He was successful and on the night of 11th-12th April four or five boats appeared and ferried all of us across the river.

We made camp four miles from the Irrawaddy. We had crossed the major river obstacle between us and safety. We still had to cross the Chindwin and other smaller rivers, but they should present us with little difficulty, providing we crossed them before the monsoon rains broke in late May or early June.

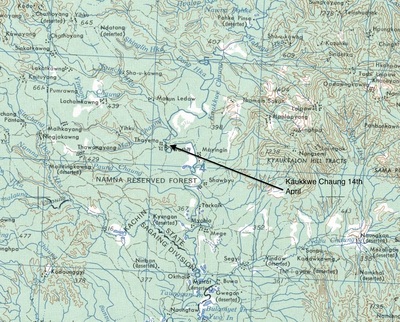

We had over 200 miles to cover before reaching the Chindwin. By the morning of 14th April we had crossed the Kaukkwe Chaung, a north-south flowing river which joined the Irrawaddy and entered the village of Thayetta. Tun Tin was arranging the purchase of rice, chickens and vegetables while I sat down to remove my boots and examine my sore feet. I noticed briefly a villager leaving the village on a bicycle and heading north. I thought nothing of this at the time and did not realise the significance until later in the morning.

We had not gone far from the village when, totally out of the blue, an ambush exploded abruptly to my immediate left. I can remember roaring out to my men "Dahine tira sut!" (Take cover, right!) before diving for cover myself into the bushes to the right of the track. I remember I wasn't actually frightened — which surprised me — but I was totally and utterly shocked. Never, ever, during any of my previous training had I been taught any of the approved contact drills; certainly the counter-ambush drill was unknown to me. I was utterly appalled to realise that I simply did not know what to do to extract myself and my men from our predicament.

A Jap gunner was firing his LMG immediately opposite me from the jungle on the far side of the track and another was firing at the men who were behind me. I could see the smoke rising from his gun muzzle and his bursts of fire were hitting the trees and bushes above my head. When the Jap gunner stopped firing to change magazines I roared above the noise of the continuing rifle fire, "Sabai jana ut! Mero pachhi aija!" (Everybody up! Follow me!). I leapt to my feet, turned away from the track and crashed through the jungle, calling to my men to follow.

I looked around and saw some of my Gurkhas and Tag's men running parallel to me. When we halted, there were only twenty of us. Tag and I, eleven Gurkhas, six of Tag's men and one Burma Rifleman. I did not believe that many of the others had been killed, but those missing were without maps and compasses. My guilt at not being able to do better for them in the ambush, and being unable to maintain contact with them afterwards, hung very heavy on my conscience and still does to this day.

It was clear that the villager who had left Thayetta on his bicycle had gone straight to the nearest Japanese outpost to alert them. The survivors of the ambush had to put as much distance between them and the village as possible, before making camp for the night. The next day they set a course westwards for the Chindwin, straight across country. They did not see a track again for three weeks.

After a couple of days, Sergeant Sennett and the five other British Commandos asked Tag Sprague if they could turn about and head east for China. They planned to make for one of the pre-arranged drop zones, collect some rations and then make for China. Tag told them frankly that they were mad to go to the DZ (drop zone) area, as the enemy would probably be waiting there by this time and by going towards China they would be heading into the unknown. They were adamant, however, and with reluctance Tag gave them a map and compass and allowed them to go. They were all highly-trained and experienced infantry soldiers, and in my opinion it was the correct thing to let them go. But they were never seen or heard of again, poor chaps.

Jim Tomlinson could have been with this break away party, or perhaps had become detached from the main group after the ambush at Thayetta. From other Chindit accounts relating to this decision to leave the group, it seems that Sergeant Sennett, (whose actual surname was spelled Sinnett) and the other men were suffering badly from eating nothing but rice. Their bodies, weakened by constant marching and ravaged by malaria and dysentery, craved some form of British food, which was the reason they chose to head off toward the drop zone area.

Whether Jim was with Sergeant Sinnett or not, he did not get very much further before things began to go wrong. One of his colleagues from 142 Commando, Pte. J. Lewis, formerly of the Royal Welch Fusiliers managed to make it safely back to India. Pte. Lewis gave a witness statement on his return and this is the last information we have in regard to the Commandos movements after leaving Lieutenants Sprague and Neill. Here is that statement:

In the case of:

Pte. S. Laybourne

Pte. J. Reeve

Pte. G. Park

Pte. J. Tomlinson

"I was a member of 142 Commando attached to No. 8 Column in the Wingate Expedition into Burma in 1943. The above-mentioned and myself were separated from the Column after a dispersal at Thayetta, on or about 16th April 1943. We intended making for the Chindwin by marching north-west.

This we did for three days until we came to the village of Mohnyin, on the Myitkhina-Mandalay Railway. We decided to cross the railway after dark and took cover in some bushes until we were ready to move. After approximately a quarter of an hour we were fired on by a group of Japs. We withdrew and after about fifteen minutes I discovered I was alone.

I looked about and waited until the following morning but they did not turn up. Eventually I left my hiding place and later contacted another group. I have not seen the above mentioned B.O.R's since. When I saw them last they had a rifle each and some ammunition but no food. Their condition was none too good as we had had very little food for several days."

Signed J. Lewis Pte. (No. 4202597).

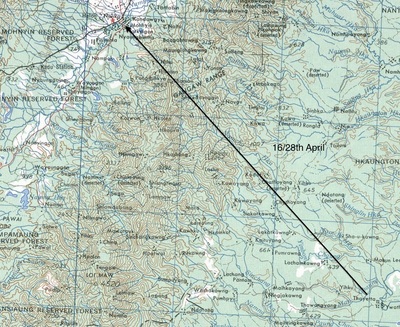

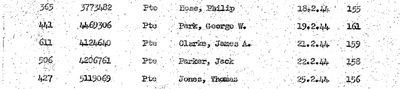

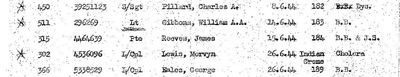

Although Pte. Lewis had managed to evade capture at this point and succeeded in returning all the way back to India, the other men were not so fortunate. From prisoner of war records held at the National Archives we now know that Jim was captured by the Japanese on the 28th April, James Reeve on the 29th and George Park a short time after that. Sadly, Sydney Laybourne was killed, most probably at the Mohnyin engagement.

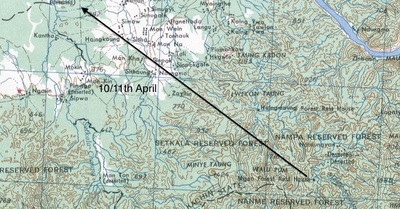

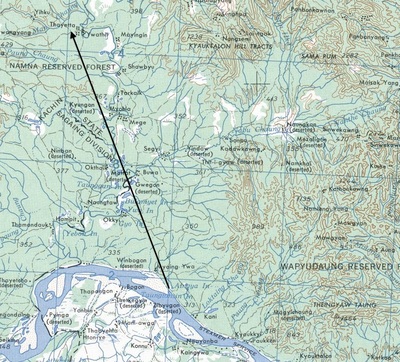

Shown below is a sequence of maps, tracing the pathway of the dispersal party led by Lieutenants Sprague and Neill, beginning at the rest house at Nisan and plotting their journey to the Irrawaddy at Zibyugon. The maps then show the journey to the village of Thayetta where the group were ambushed by the Japanese, after this we pick up Jim Tomlinson and his smaller group as they head up to the railway at Mohnyin. The last image shows the area around Mohnyin where Jim and his comrades attempted, but ultimately failed to evade capture by the Japanese. Please click on any image to enlarge it.

The following day we received our air drop and then, for the first time, I was invited to join Scotty's '0' (orders) Group. It was indeed true that all columns of the Brigade were to be split up into much smaller groups and were to find their own way back to India, or China, the latter country being the nearest to us now.

Our one radio in the column would go with Scotty's group after we had dispersed — lucky for some! Wingate had now played us his final ace card. He had taken us deep into enemy-held territory and now we were required to return to safety in penny-packets, on our own and without any communications, thus condemning us to receive no further administrative or tactical air support.

In my judgement, we should have forced a crossing of the Irrawaddy when we had the chance and when we were in considerable strength. We would of course have taken casualties during the crossing, but these, I believe, would have been far fewer than those ultimately suffered by the Brigade as a whole, during the retreat we were about to carry out in small groups, without any inter-linking support of any kind.

I asked Lieutenant Tag Sprague, who commanded the Column's Commando/demolition section from 142 Company, if he and his small band of Commandos might like to join my Gurkhas and I for the return journey. Much to my pleasure and relief he agreed readily to my suggestion. He was four years older than me and had fought in Norway with 1 Commando. We have remained friends to this day.

Scotty gave us the map co-ordinates of a number of Drop Zones to the north where the RAF would be dropping supplies and to which we could go if we required further supplies during our withdrawal. He then issued us with maps and compasses, the first time I had been given such navigation aids. Now in the middle of a wilderness, with the same poor knowledge of map reading as before, I was being required to take my small group of ill-trained young Gurkhas over hundreds of miles of inhospitable terrain and through the whole of the Japanese 33rd Division, who were already searching for us with the intention of preventing our escape.

It is perhaps not surprising that I should have been so critical of Wingate's training methods and battle tactics. So, in the early part of April, Tag and I, with my fifty-two Gurkhas and his dozen or so BORs (British Other Ranks), split from 8 Column to begin our long march back to the Chindwin. We crammed ten days' bulky rations into our packs, the only supplies we would have unless we could buy some from villages on the way.

I was given 400 silver rupees for this purpose and I put them into one of the two basic pouches on my web belt. They weighed a ton, as did my pack, and I nearly fell over as I put it on. The only way I could stand up straight was to place my rifle butt on the ground behind me and poke the muzzle underneath the pack to take the weight. But carry it I did. A man's pack from that day on carried very literally his lifeblood and it was never, ever to be discarded.

Tag (Lieuteneant Sprague's nickname taken from his intitials) and I decided to march in a northerly direction to try to recross the vast Irrawaddy somewhere along its stretch where it flows east-west between the big villages of Bhamo and Katha. We would have to avoid Shwegu though, as that village contained a Jap garrison.

Every escape group had been given a few soldiers from Nigel Whitehead's Platoon of 2 Burma Rifles and we were delighted to find that we had Naik Tun Tin and four Riflemen attached to us. An outstanding NCO, Tun Tin and his men were Karens and he had been educated at a mission school. He was very intelligent and spoke excellent English and was to prove to be of tremendous assistance to us. Sadly, however, we were soon parted from him.

It took four days to reach the Irrawaddy, near the village of Zibyugon. The sal trees were in blossom; they smelt like a wet flannel and whenever I scent such a smell my mind goes back to that day at Zibyugon, and our brief stay there while we searched for boats to take us across the river. Tun Tin and two of his men changed into civilian clothes and went into Zibyugon to try to find boats to carry us across. He was successful and on the night of 11th-12th April four or five boats appeared and ferried all of us across the river.

We made camp four miles from the Irrawaddy. We had crossed the major river obstacle between us and safety. We still had to cross the Chindwin and other smaller rivers, but they should present us with little difficulty, providing we crossed them before the monsoon rains broke in late May or early June.

We had over 200 miles to cover before reaching the Chindwin. By the morning of 14th April we had crossed the Kaukkwe Chaung, a north-south flowing river which joined the Irrawaddy and entered the village of Thayetta. Tun Tin was arranging the purchase of rice, chickens and vegetables while I sat down to remove my boots and examine my sore feet. I noticed briefly a villager leaving the village on a bicycle and heading north. I thought nothing of this at the time and did not realise the significance until later in the morning.

We had not gone far from the village when, totally out of the blue, an ambush exploded abruptly to my immediate left. I can remember roaring out to my men "Dahine tira sut!" (Take cover, right!) before diving for cover myself into the bushes to the right of the track. I remember I wasn't actually frightened — which surprised me — but I was totally and utterly shocked. Never, ever, during any of my previous training had I been taught any of the approved contact drills; certainly the counter-ambush drill was unknown to me. I was utterly appalled to realise that I simply did not know what to do to extract myself and my men from our predicament.

A Jap gunner was firing his LMG immediately opposite me from the jungle on the far side of the track and another was firing at the men who were behind me. I could see the smoke rising from his gun muzzle and his bursts of fire were hitting the trees and bushes above my head. When the Jap gunner stopped firing to change magazines I roared above the noise of the continuing rifle fire, "Sabai jana ut! Mero pachhi aija!" (Everybody up! Follow me!). I leapt to my feet, turned away from the track and crashed through the jungle, calling to my men to follow.

I looked around and saw some of my Gurkhas and Tag's men running parallel to me. When we halted, there were only twenty of us. Tag and I, eleven Gurkhas, six of Tag's men and one Burma Rifleman. I did not believe that many of the others had been killed, but those missing were without maps and compasses. My guilt at not being able to do better for them in the ambush, and being unable to maintain contact with them afterwards, hung very heavy on my conscience and still does to this day.

It was clear that the villager who had left Thayetta on his bicycle had gone straight to the nearest Japanese outpost to alert them. The survivors of the ambush had to put as much distance between them and the village as possible, before making camp for the night. The next day they set a course westwards for the Chindwin, straight across country. They did not see a track again for three weeks.

After a couple of days, Sergeant Sennett and the five other British Commandos asked Tag Sprague if they could turn about and head east for China. They planned to make for one of the pre-arranged drop zones, collect some rations and then make for China. Tag told them frankly that they were mad to go to the DZ (drop zone) area, as the enemy would probably be waiting there by this time and by going towards China they would be heading into the unknown. They were adamant, however, and with reluctance Tag gave them a map and compass and allowed them to go. They were all highly-trained and experienced infantry soldiers, and in my opinion it was the correct thing to let them go. But they were never seen or heard of again, poor chaps.

Jim Tomlinson could have been with this break away party, or perhaps had become detached from the main group after the ambush at Thayetta. From other Chindit accounts relating to this decision to leave the group, it seems that Sergeant Sennett, (whose actual surname was spelled Sinnett) and the other men were suffering badly from eating nothing but rice. Their bodies, weakened by constant marching and ravaged by malaria and dysentery, craved some form of British food, which was the reason they chose to head off toward the drop zone area.

Whether Jim was with Sergeant Sinnett or not, he did not get very much further before things began to go wrong. One of his colleagues from 142 Commando, Pte. J. Lewis, formerly of the Royal Welch Fusiliers managed to make it safely back to India. Pte. Lewis gave a witness statement on his return and this is the last information we have in regard to the Commandos movements after leaving Lieutenants Sprague and Neill. Here is that statement:

In the case of:

Pte. S. Laybourne

Pte. J. Reeve

Pte. G. Park

Pte. J. Tomlinson

"I was a member of 142 Commando attached to No. 8 Column in the Wingate Expedition into Burma in 1943. The above-mentioned and myself were separated from the Column after a dispersal at Thayetta, on or about 16th April 1943. We intended making for the Chindwin by marching north-west.

This we did for three days until we came to the village of Mohnyin, on the Myitkhina-Mandalay Railway. We decided to cross the railway after dark and took cover in some bushes until we were ready to move. After approximately a quarter of an hour we were fired on by a group of Japs. We withdrew and after about fifteen minutes I discovered I was alone.

I looked about and waited until the following morning but they did not turn up. Eventually I left my hiding place and later contacted another group. I have not seen the above mentioned B.O.R's since. When I saw them last they had a rifle each and some ammunition but no food. Their condition was none too good as we had had very little food for several days."

Signed J. Lewis Pte. (No. 4202597).

Although Pte. Lewis had managed to evade capture at this point and succeeded in returning all the way back to India, the other men were not so fortunate. From prisoner of war records held at the National Archives we now know that Jim was captured by the Japanese on the 28th April, James Reeve on the 29th and George Park a short time after that. Sadly, Sydney Laybourne was killed, most probably at the Mohnyin engagement.

Shown below is a sequence of maps, tracing the pathway of the dispersal party led by Lieutenants Sprague and Neill, beginning at the rest house at Nisan and plotting their journey to the Irrawaddy at Zibyugon. The maps then show the journey to the village of Thayetta where the group were ambushed by the Japanese, after this we pick up Jim Tomlinson and his smaller group as they head up to the railway at Mohnyin. The last image shows the area around Mohnyin where Jim and his comrades attempted, but ultimately failed to evade capture by the Japanese. Please click on any image to enlarge it.

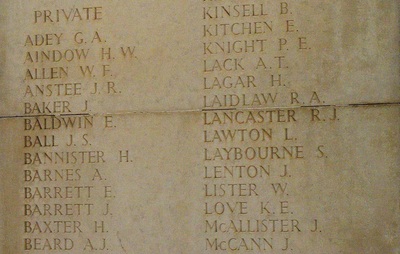

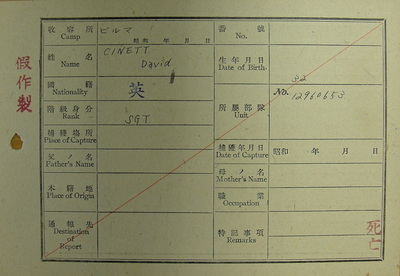

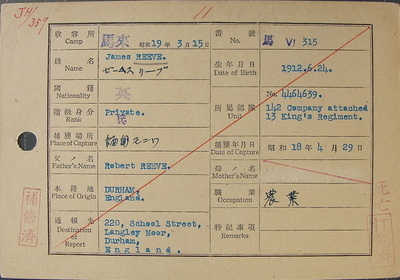

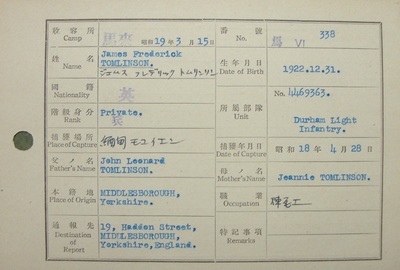

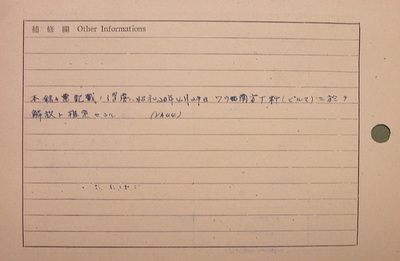

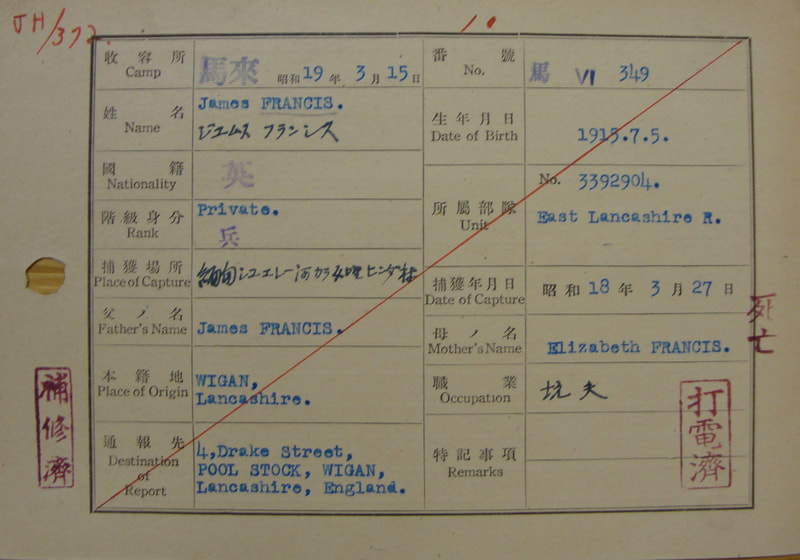

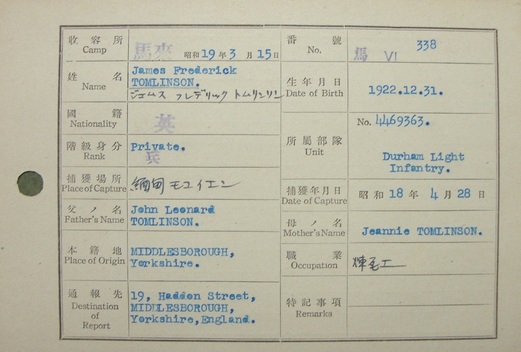

The Japanese Index Card for Jim Tomlinson.

The Japanese Index Card for Jim Tomlinson.

Here is the Japanese Index card for Jim Tomlinson, these cards are held at the National Archives in London and can be found in the file series WO345, the cards are stored alphabetically in boxes.

Jim's card shows his name, rank and next of kin details on the left hand side, with his POW number in the top right corner (338), his date of birth, service number and date of capture, which reads 28/04/1943.

He was captured comparatively late on in the operation and so I feel that he would probably have been transported almost immediately to Rangoon Jail, probably arriving in early May. Many Chindits captured earlier than this were taken to a concentration camp at Maymyo and soon learned the harsh reality of being a prisoner of the Japanese.

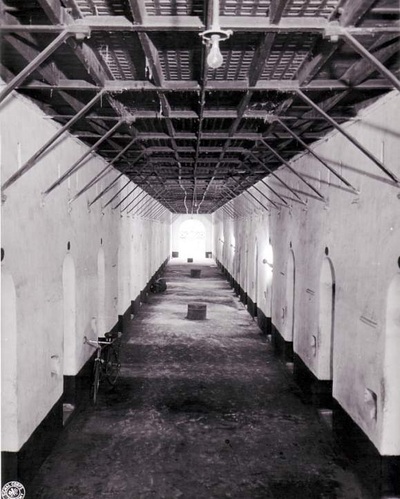

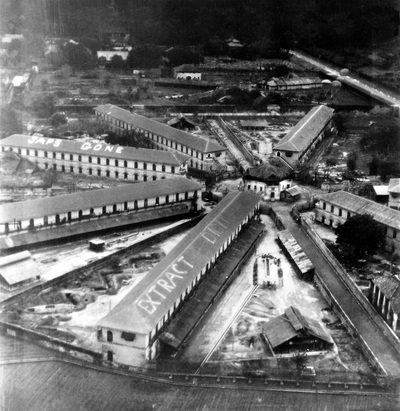

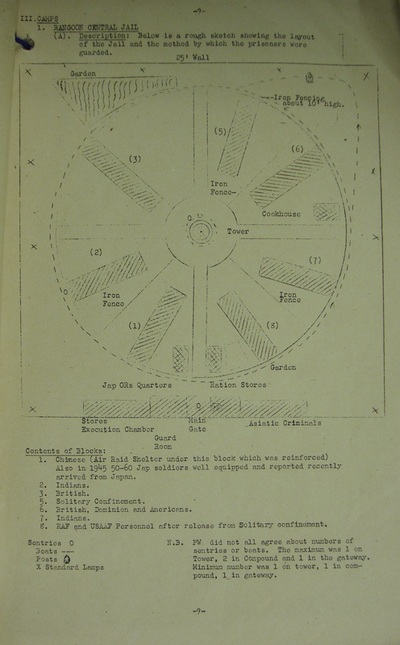

Having arrived at Rangoon Central Jail the captured Chindits from 1943 were placed into Block 6 of the prison. The jail is styled in the shape of a cartwheel with long cell blocks radiating off a central circular courtyard. Conditions in the jail were atrocious, with poor sanitary facilities, a lack of fresh running water and low quality rations of rice served twice a day to the already starving men. By the second week in May Jim would have found himself sharing Block 6 with well over 200 of his fellow Chindits from Operation Longcloth. These new POW's joined men who had ben captured during the infamous retreat out of Burma by British troops almost one year before. For a more detailed account of Rangoon Jail and the men imprisoned there, please click on the following link:

Chindit POW's

As mentioned earlier most of the men captured in 1943 were already suffering from the ravages of their time in the Burmese jungle. They were all malnourished and exhausted, some were injured or wounded and most showed the outward affects of at least one tropical disease. It was no surprise then that they began to fall away very quickly once inside the jail, dying in twos and threes almost every day. Block 6 became a desolate place in which to exist and the morale and behaviour of the Chindits deteriorated.

Block 6 had been run by Flight Lieutenant MacDonald, a New Zealand born RAF Officer captured some time earlier in the war. He struggled to keep up discipline in the block once the new and unruly influx of prisoners arrived. One of the newly imprisoned Chindits from 1943, Lieutenant Alan 'Willy' Wilding remembered the first few weeks in Rangoon:

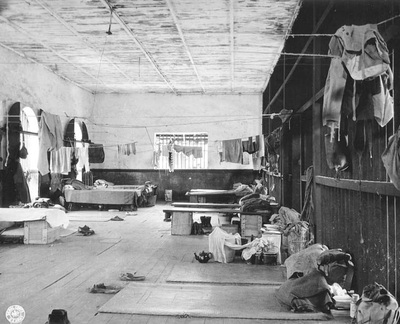

"Each block had two storeys, all except Block 5 (solitary confinement cells) had four rooms on each storey about 30 ft x 18 ft. Downstairs had a concrete floor and some rather uncomfortable beds. Upstairs the floors were wooden and no beds unless you were very lucky. Each had a water trough supplied by the mains, on and off, a lean-to cook house and a very primitive latrine.

On arrival at Rangoon the Chindits were marched straight in to Block 6, fortunate not to have a spell in solitary. Commanded by a New Zealander Flt/Lt Macdonald numbers there must have been just under 200. They had nothing but the clothes they were wearing and some sort of eating utensil.

Block 6 was chaotic. Most were Chindits and rebellious - with no intention of co-operating with the Nips. Macdonald was young and went along with them. As a result they had a pretty rotten time, to an extent their own fault, but they did it for the best.

I felt sorry for Company Quartermaster Sergeant Partington, for some time he had the thankless task of being the senior NCO in the turbulent and ramshackle Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. He did his best, and it was a very good best. Poor chap died quite early on of dysentery.

After a month a number of prisoners were released from solitary, including Major Ramsey the senior Medical Officer from Operation Longcloth. But the men's reputation for bloody mindedness was well established by then. Morale got very low when wood for the cooks fire was always wet and they got the worst vegetables. Despite Major Ramsey’s efforts they started losing one, often two men a day."

Conditions in Rangoon were extremely harsh for the POW's, even though they existed on meagre rations the prison guards still insisted they work long hours labouring for the Japanese cause. It was commonplace for the Chindits to be employed down at the local docks, loading and unloading ships cargo in the fierce heat of the Burmese summer, or the torrential rains of monsoon. The one bonus of this work was the opportunity to steal goods and more importantly food to supplement their poor diet.

The prison guards worked the POW's hard and were often brutal in meting out severe punishment to any man who did not complete his allotted task or was caught stealing food. Howard Rutland, Jim's nephew told me:

"Although I spent a lot of time with Jim, he didn't speak much about his time as a POW and when he did it was always light-hearted.

He gave me snippets of accounts of his escape, treatment by the guards especially the 'Bullfrog' and daily life in Rangoon Prison Camp, but not much detail really."

The Japanese Guard was nicknamed 'the Bullfrog' because of his ugly and squashed facial features which included his large bulbous eyes. This guard was infamous for mis-treating the men when out on working parties in the city. It is alleged that he once beat a prisoner so badly for falling asleep in a warehouse, that the man lost his mind and never recovered from this ordeal even after returning home to his family.

Sadly, many of the Chindits did not survive their time in Rangoon Jail, this was the case for both men captured with Jim in April 1943. George Park who was from Hartlepool died on the 19th February 1944 in Block 6, whilst James Reeve, originally from Durham lasted just a few months longer, perishing on 15th June from the combined affects of beri beri and acute jungle sores. They were both buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery situated less than 2 miles from the jail. It was normal practice for the closest friends of the departed to accompany them on their final journey to the cemetery, carrying the homemade coffin on a cart.

Amazingly Jim Tomlinson is mentioned in the notes from Lieutenant Wilding's memoir. Here is how the officer remembered Pte. Tomlinson of 142 Commando:

"There was a troublesome soldier called, I think, Tomlinson. As I was Adjutant, I had to try to discipline him. Nothing I could do or say would make him behave, and without discipline there could be no survival.

In despair, I looked round for the most revolting job I could think of and decided that it was washing swabs for the "Hospital". He had septic scabies all over his hands, but I understood the Medical Officer to say that one more infection wouldn't matter.

So I set him to do this job for a week. It did NOT reform him. Anyway, poor old Tomlinson carried out his sentence and, as he had his hands in warm or warmish water all day, his scabies cleared up. It was reported to me that he said, "Mr. ******* Ramsay couldn't ******* cure my ******* hands, but ******* Wilding did. Major Ramsay was our Medical Officer."

I sent this anecdote about Jim to his nephew Howard; this was his reply:

Thank you so very much Stephen. I really appreciate these updates. So do all of Jim's remaining family. The diary entry is so typical of Jim, acerbic and humourous in the same degree. Just wish he was still here to share it with.

In late April 1945 the Japanese, realising that the war in Burma was going badly wrong for them, decided to vacate Rangoon before the Allied troops advancing quickly from the north reached the city outskirts. The guards in the jail were instructed to sort the prisoners into 'fit' and 'unfit' categories, with the fittest men chosen to be removed from the jail and taken along with the Japanese troops as they marched out, with the view of escaping into Thailand. Jim was deemed to be fit enough to be part of this group.

The men were arranged into sections and marched away from the jail on the 24th April and moved in a north-easterly direction toward the town of Pegu. Many men found this march too much for their debilitated bodies and dropped out of the line, some were bayonetted where they fell by the Japanese guards. Allied forces were closing in on this area and many RAF aircraft patrolled the skies during daylight hours. Finally the Japanese Commander decided that the POW's were in fact hindering his men's progress and he called a meeting with the British senior officer, Brigadier Hobson. On the 29th April the 400 or so POW's were given their freedom near a very small village called Waw.

From the stories Jim told about his escape, I would suggest that he was not present when Brigadier Hobson announced to the men that they were at last free. Several small groups of prisoners had already decided to abscond from the march when circumstances were favourable. They had seen Japanese brutality once too often and reckoned to take their chance and escape into the jungle before they had crossed over into Thailand and doubtless further captivity. This was almost certainly the moment that Jim decided to escape.

Seen below are some photographs and documents relating to Jim Tomlinson and his time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail. Please click on any image to enlarge it, or the forward arrow to view the next image:

Jim's card shows his name, rank and next of kin details on the left hand side, with his POW number in the top right corner (338), his date of birth, service number and date of capture, which reads 28/04/1943.

He was captured comparatively late on in the operation and so I feel that he would probably have been transported almost immediately to Rangoon Jail, probably arriving in early May. Many Chindits captured earlier than this were taken to a concentration camp at Maymyo and soon learned the harsh reality of being a prisoner of the Japanese.

Having arrived at Rangoon Central Jail the captured Chindits from 1943 were placed into Block 6 of the prison. The jail is styled in the shape of a cartwheel with long cell blocks radiating off a central circular courtyard. Conditions in the jail were atrocious, with poor sanitary facilities, a lack of fresh running water and low quality rations of rice served twice a day to the already starving men. By the second week in May Jim would have found himself sharing Block 6 with well over 200 of his fellow Chindits from Operation Longcloth. These new POW's joined men who had ben captured during the infamous retreat out of Burma by British troops almost one year before. For a more detailed account of Rangoon Jail and the men imprisoned there, please click on the following link:

Chindit POW's

As mentioned earlier most of the men captured in 1943 were already suffering from the ravages of their time in the Burmese jungle. They were all malnourished and exhausted, some were injured or wounded and most showed the outward affects of at least one tropical disease. It was no surprise then that they began to fall away very quickly once inside the jail, dying in twos and threes almost every day. Block 6 became a desolate place in which to exist and the morale and behaviour of the Chindits deteriorated.

Block 6 had been run by Flight Lieutenant MacDonald, a New Zealand born RAF Officer captured some time earlier in the war. He struggled to keep up discipline in the block once the new and unruly influx of prisoners arrived. One of the newly imprisoned Chindits from 1943, Lieutenant Alan 'Willy' Wilding remembered the first few weeks in Rangoon:

"Each block had two storeys, all except Block 5 (solitary confinement cells) had four rooms on each storey about 30 ft x 18 ft. Downstairs had a concrete floor and some rather uncomfortable beds. Upstairs the floors were wooden and no beds unless you were very lucky. Each had a water trough supplied by the mains, on and off, a lean-to cook house and a very primitive latrine.

On arrival at Rangoon the Chindits were marched straight in to Block 6, fortunate not to have a spell in solitary. Commanded by a New Zealander Flt/Lt Macdonald numbers there must have been just under 200. They had nothing but the clothes they were wearing and some sort of eating utensil.

Block 6 was chaotic. Most were Chindits and rebellious - with no intention of co-operating with the Nips. Macdonald was young and went along with them. As a result they had a pretty rotten time, to an extent their own fault, but they did it for the best.

I felt sorry for Company Quartermaster Sergeant Partington, for some time he had the thankless task of being the senior NCO in the turbulent and ramshackle Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. He did his best, and it was a very good best. Poor chap died quite early on of dysentery.

After a month a number of prisoners were released from solitary, including Major Ramsey the senior Medical Officer from Operation Longcloth. But the men's reputation for bloody mindedness was well established by then. Morale got very low when wood for the cooks fire was always wet and they got the worst vegetables. Despite Major Ramsey’s efforts they started losing one, often two men a day."

Conditions in Rangoon were extremely harsh for the POW's, even though they existed on meagre rations the prison guards still insisted they work long hours labouring for the Japanese cause. It was commonplace for the Chindits to be employed down at the local docks, loading and unloading ships cargo in the fierce heat of the Burmese summer, or the torrential rains of monsoon. The one bonus of this work was the opportunity to steal goods and more importantly food to supplement their poor diet.

The prison guards worked the POW's hard and were often brutal in meting out severe punishment to any man who did not complete his allotted task or was caught stealing food. Howard Rutland, Jim's nephew told me:

"Although I spent a lot of time with Jim, he didn't speak much about his time as a POW and when he did it was always light-hearted.

He gave me snippets of accounts of his escape, treatment by the guards especially the 'Bullfrog' and daily life in Rangoon Prison Camp, but not much detail really."

The Japanese Guard was nicknamed 'the Bullfrog' because of his ugly and squashed facial features which included his large bulbous eyes. This guard was infamous for mis-treating the men when out on working parties in the city. It is alleged that he once beat a prisoner so badly for falling asleep in a warehouse, that the man lost his mind and never recovered from this ordeal even after returning home to his family.

Sadly, many of the Chindits did not survive their time in Rangoon Jail, this was the case for both men captured with Jim in April 1943. George Park who was from Hartlepool died on the 19th February 1944 in Block 6, whilst James Reeve, originally from Durham lasted just a few months longer, perishing on 15th June from the combined affects of beri beri and acute jungle sores. They were both buried in the English Cantonment Cemetery situated less than 2 miles from the jail. It was normal practice for the closest friends of the departed to accompany them on their final journey to the cemetery, carrying the homemade coffin on a cart.

Amazingly Jim Tomlinson is mentioned in the notes from Lieutenant Wilding's memoir. Here is how the officer remembered Pte. Tomlinson of 142 Commando:

"There was a troublesome soldier called, I think, Tomlinson. As I was Adjutant, I had to try to discipline him. Nothing I could do or say would make him behave, and without discipline there could be no survival.

In despair, I looked round for the most revolting job I could think of and decided that it was washing swabs for the "Hospital". He had septic scabies all over his hands, but I understood the Medical Officer to say that one more infection wouldn't matter.

So I set him to do this job for a week. It did NOT reform him. Anyway, poor old Tomlinson carried out his sentence and, as he had his hands in warm or warmish water all day, his scabies cleared up. It was reported to me that he said, "Mr. ******* Ramsay couldn't ******* cure my ******* hands, but ******* Wilding did. Major Ramsay was our Medical Officer."

I sent this anecdote about Jim to his nephew Howard; this was his reply:

Thank you so very much Stephen. I really appreciate these updates. So do all of Jim's remaining family. The diary entry is so typical of Jim, acerbic and humourous in the same degree. Just wish he was still here to share it with.

In late April 1945 the Japanese, realising that the war in Burma was going badly wrong for them, decided to vacate Rangoon before the Allied troops advancing quickly from the north reached the city outskirts. The guards in the jail were instructed to sort the prisoners into 'fit' and 'unfit' categories, with the fittest men chosen to be removed from the jail and taken along with the Japanese troops as they marched out, with the view of escaping into Thailand. Jim was deemed to be fit enough to be part of this group.

The men were arranged into sections and marched away from the jail on the 24th April and moved in a north-easterly direction toward the town of Pegu. Many men found this march too much for their debilitated bodies and dropped out of the line, some were bayonetted where they fell by the Japanese guards. Allied forces were closing in on this area and many RAF aircraft patrolled the skies during daylight hours. Finally the Japanese Commander decided that the POW's were in fact hindering his men's progress and he called a meeting with the British senior officer, Brigadier Hobson. On the 29th April the 400 or so POW's were given their freedom near a very small village called Waw.

From the stories Jim told about his escape, I would suggest that he was not present when Brigadier Hobson announced to the men that they were at last free. Several small groups of prisoners had already decided to abscond from the march when circumstances were favourable. They had seen Japanese brutality once too often and reckoned to take their chance and escape into the jungle before they had crossed over into Thailand and doubtless further captivity. This was almost certainly the moment that Jim decided to escape.

Seen below are some photographs and documents relating to Jim Tomlinson and his time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon Jail. Please click on any image to enlarge it, or the forward arrow to view the next image:

As I stated earlier, it has been my good fortune and pleasure to make contact with Jim's family. It is of course frustrating to have never had the opportunity to speak with the Jim in person, but had the family not taken the trouble to make his Army service known publicly, I would never of known all these fantastic details about him and his time in Burma.

Howard told me that:

"I'd like to sincerely thank you for all your efforts. It's greatly appreciated by myself and my family. It has added some detail to what was a largely unknown part of Jim's life. I'm really thirsty for more information now and I would really appreciate any more documents or records which pertain to Jim when you have the time.

My first overriding feeling is that Jim would have absolutely loved to have seen all of this. It's amazing to think of what these men went through back then, but didn't want to talk about it. Personally I'm sure I would have been bitter and wanted justice/revenge/retaliation, but Jim limited himself to not buying Japanese cars!

I read a book called 'Prisoners of the Japanese' by Gavan Daws, it absolutely horrified me. After reading it I found it hard not to hate the Japanese for what they did. I can't imagine myself or any of the people I know being so cruel. This makes it all the more remarkable that people like Jim kept it to themselves. I'm sure I would have wanted to tell the world.

I will pass everything onto my mother (Jim's sister) and my own sister. We all still miss Jim terribly and reminisce about him every Sunday when we raise a glass and proclaim 'arigato Jim'."

Howard told me that:

"I'd like to sincerely thank you for all your efforts. It's greatly appreciated by myself and my family. It has added some detail to what was a largely unknown part of Jim's life. I'm really thirsty for more information now and I would really appreciate any more documents or records which pertain to Jim when you have the time.

My first overriding feeling is that Jim would have absolutely loved to have seen all of this. It's amazing to think of what these men went through back then, but didn't want to talk about it. Personally I'm sure I would have been bitter and wanted justice/revenge/retaliation, but Jim limited himself to not buying Japanese cars!

I read a book called 'Prisoners of the Japanese' by Gavan Daws, it absolutely horrified me. After reading it I found it hard not to hate the Japanese for what they did. I can't imagine myself or any of the people I know being so cruel. This makes it all the more remarkable that people like Jim kept it to themselves. I'm sure I would have wanted to tell the world.

I will pass everything onto my mother (Jim's sister) and my own sister. We all still miss Jim terribly and reminisce about him every Sunday when we raise a glass and proclaim 'arigato Jim'."

Seen above are Jim's WW2 medals, the Burma Star, War Medal and 1939-45 Star and his treasured 142 Commando unit insignia. Listed below are the men he worked and trained with in the Commando Section of Chindit Column 8 and what ultimately happened to them on Operation Longcloth.

The Men of 142 Commando Platoon, Column 8

Lieutenant 75434 Thomas Anthony Grafton Sprague. Known as 'Tag' to his friends and comrades, this young and enthusiastic officer commanded his section with honesty and fairness and was well liked by his men. He returned to India in May 1943 in the company of Lieutenant Dominic Neill and his Gurkhas.

Sergeant 5183080 Walter Gordon Paginton. Gloucester born, this man was an original member of 142 Commando from its inception and had come from the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo. Walter was last seen crossing the Shweli River on April 1st with Captain Williams lead group, this party was ambushed by the Japanese and the Sergeant was reported as being killed on 27th April 1943.

Sergeant 3960653 David Sinnett. As we know from Lieutenant Neill's account, Sgt. Sinnett and his group of Commandos left the dispersal party to seek an alternative route out of Burma. David sadly died whilst a POW on 29th July, he had lasted longer than most in the jungles of Burma, but perished soon after his arrival in Rangoon. He is buried along with his fellow Chindit comrades in Rangoon War Cemetery.

Lance Corporal 2027853 Joseph Crompton White. A former soldier with the North Staffordshire regiment, this man fell out of line during a march near the Mandalay Railway in early April 1943. He was never seen or heard of again.

Lance Corporal 3959534 Thomas Edward Williams. Thomas was reported missing on the 1st March 1943, close to the town of Pinlebu. We know that Column 8 was involved in several actions against the enemy in this area, but nothing is known about the fate of Lance Corporal Williams.

Fusilier 4192910 Archibald Walter Allen. Born in Swansea, this man was lost after the engagement at the Nisan Rest House on 14th April 1943. He was later captured by the Japanese and died from the ravages of beri beri in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. Archibald is buried in Rangoon War Cemetery.

Pte. 5183169 John Boyd. An original member of 142 Commando having come over from the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo in the summer of 1942. John was also lost at the Nisan Rest House about the same time as Fusilier Allen. Here is a fairly harrowing quote from a witness statement in regard to Pte. Boyd:

"Boyd was last seen at the Irrawaddy, where he attempted to swim the river. Cries for help were heard shortly after he entered the water."

Pte. Boyd was given the 13th April as his official date of death although nobody actually witnessed his demise that day. According to his official Army Will, John Boyd was from Horfield, a suburb on the northern outskirts of Bristol. He had originally served with Gloucestershire Regiment before being posted overseas to India and left all his effects to his brother, J.A. Boyd of 26 Radnor Road, Horfield.

Fusilier 4187929 L. Britton. A soldier originally from the Royal Welch Fusiliers, not much is known about this man apart from the fact that he survived Operation Longcloth.

Sapper 1874407 Frederick Doyle. This Royal Engineer was attached to 142 Commando in the summer of 1942 at the Abchand Camp in Patharia. Frederick was lost on the line of march and was captured by the enemy. He sadly perished in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on 31st December 1943 and is now remembered at Rangoon War Cemetery.

Pte. 3392904 James Francis. From Wigan in Lancashire and formerly of the East Lancs Regiment, this man was last seen on the 27th March at the village of Inywa and soon after must have been captured by the Japanese. James sadly died in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail on the 7th August 1944 suffering from the disease beri beri. He was given the POW number 349 inside the jail and like all his fellow Chindit comrades who perished as prisoners of war at Rangoon, James now lies buried in Rangoon War Cemetery.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to Pte. Francis including a photograph of his grave plaque at Rangoon War Cemetery. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The Men of 142 Commando Platoon, Column 8

Lieutenant 75434 Thomas Anthony Grafton Sprague. Known as 'Tag' to his friends and comrades, this young and enthusiastic officer commanded his section with honesty and fairness and was well liked by his men. He returned to India in May 1943 in the company of Lieutenant Dominic Neill and his Gurkhas.

Sergeant 5183080 Walter Gordon Paginton. Gloucester born, this man was an original member of 142 Commando from its inception and had come from the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo. Walter was last seen crossing the Shweli River on April 1st with Captain Williams lead group, this party was ambushed by the Japanese and the Sergeant was reported as being killed on 27th April 1943.

Sergeant 3960653 David Sinnett. As we know from Lieutenant Neill's account, Sgt. Sinnett and his group of Commandos left the dispersal party to seek an alternative route out of Burma. David sadly died whilst a POW on 29th July, he had lasted longer than most in the jungles of Burma, but perished soon after his arrival in Rangoon. He is buried along with his fellow Chindit comrades in Rangoon War Cemetery.

Lance Corporal 2027853 Joseph Crompton White. A former soldier with the North Staffordshire regiment, this man fell out of line during a march near the Mandalay Railway in early April 1943. He was never seen or heard of again.

Lance Corporal 3959534 Thomas Edward Williams. Thomas was reported missing on the 1st March 1943, close to the town of Pinlebu. We know that Column 8 was involved in several actions against the enemy in this area, but nothing is known about the fate of Lance Corporal Williams.

Fusilier 4192910 Archibald Walter Allen. Born in Swansea, this man was lost after the engagement at the Nisan Rest House on 14th April 1943. He was later captured by the Japanese and died from the ravages of beri beri in Block 6 of Rangoon Jail. Archibald is buried in Rangoon War Cemetery.

Pte. 5183169 John Boyd. An original member of 142 Commando having come over from the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo in the summer of 1942. John was also lost at the Nisan Rest House about the same time as Fusilier Allen. Here is a fairly harrowing quote from a witness statement in regard to Pte. Boyd:

"Boyd was last seen at the Irrawaddy, where he attempted to swim the river. Cries for help were heard shortly after he entered the water."