Lance Corporal John William Brock

Cap badge of the Suffolk Regiment.

Cap badge of the Suffolk Regiment.

5826561 L/Cpl. John William Brock was born in Leiston, Suffolk on the 13th June 1916, he was the son of William and Isobel Maude Brock from Saxmundham in Suffolk. After enlistment at Bury St. Edmunds, John was posted to the 2nd Battalion of his local regiment.

Private John Brock was sent overseas to join the 2nd Battalion who had been serving in India since 1926 and where they would remain until the outbreak of war in 1939. During the early period of his service, John Brock was employed on the North West Frontier of India and having been promoted to Lance Corporal at this time, qualified for the Indian General Service Medal with the clasp ‘North West Frontier 1937-39’.

These frontier policing duties continued on into 1940, with the 2nd Battalion Suffolk Regiment engaged in skirmishes against the tribesman of the Tochi Valley, situated on today's Afghan and Pakistan borders. Later on in the war, many men from the battalion decided to join units where they felt they stood a better chance of seeing frontline action against the real enemy, namely Japan.

This is noted in the Suffolk's Regimental history for that period:

“During the next two years (1942-43) the 2nd Battalion was to lose a high proportion of its experienced soldiers, as its role altered from that of a frontier force to one occupied in maintaining law and order within India itself."

In 1942 Lance Corporal Brock was mentioned in the 2nd Battalion's Daily Orders, dated 22nd June, under a list headed “Attachments”, as now serving in A' Company of the 13th Battalion The King’s (Liverpool) Regiment. John Brock was officially posted to the 13th King's on the 1st July 1942, joining the battalion at their Chindit training camp in the Central Provinces of India.

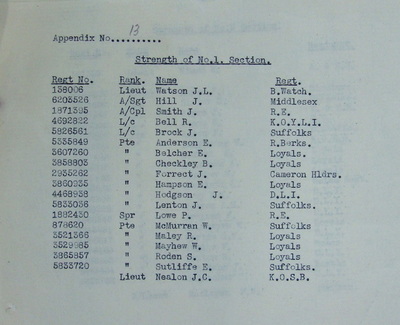

At the Saugor Camp he was taken on strength into the 142 Commando Platoon for Chindit Column 1 under the command of Lieutenant John Lindsay Watson, formerly of the Black Watch.

Lance Corporal Brock was one of five men from the 2nd Suffolk's to be placed into the 142 Commando Platoon for this column in 1942. He trained in the art of unarmed combat and learned how to use explosives and other clandestine weaponry. The names of three of the other men from the Suffolk's can be seen in the nominal roll for the Commando Platoon shown in the gallery below.

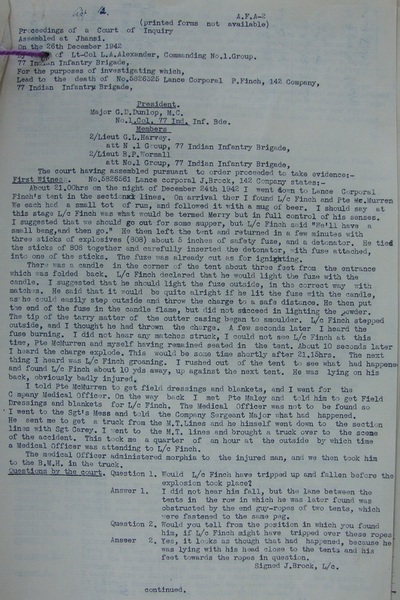

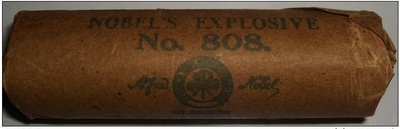

Training at Saugor could be a dangerous occupation, as John Brock was to discover just before Christmas 1942. One of his fellow Commandos, Percy Finch and some other men had been drinking in their tents back at the main camp lines. Lance Corporal Finch, also formerly with the Suffolk Regiment and presumably a member of Chindit Column 1, was then rather foolishly playing around with some explosives and fuses.

To cut a long story short, the explosive he was handling went off and Percy Finch was mortally wounded on the 24th December. A Court of Enquiry was held on Boxing Day and John Brock was the first witness called. Here is his testimony from that day:

About 21:00 hours on the night of December 24th 1942 I went down to Lance Cpl. Finch's tent in the section lines. On arrival there I found Lance Cpl. Finch and Pte. McMurran. We each had a small tot of rum, and followed it with a mug of beer. I should say at this stage that Lance Cpl. Finch was what would be termed as 'merry' but in full control of his senses. I suggested that we should go out for some supper, but Finch said "Well have a small bang first, and then go."

He then left the tent and returned within a few minutes with three sticks of explosives (type 808), about 5 inches of safety fuse, and a detonator. He tied the sticks of 808 together and carefully inserted the detonator, with the fuse attached into one of the sticks. The fuse had already been cut as for igniting.

There was a candle in the corner of the tent about 3 feet from the entrance flap, which was folded back. Finch declared that he would light the fuse with the candle. I suggested that he should light the fuse outside, in the correct way, with matches. He said that it would quite alright if he lit the fuse with the candle, as he could easily step outside and throw the charge to a safe distance. He then put the end of the fuse in the candle flame, but did not succeed in lighting the powder. The tip of the tarry matter of the outer casing began to smoulder. Finch stepped outside, and I thought he had thrown the charge.

A few seconds later I heard the fuse burning. I did not hear any matches struck, I could not see Finch at this time, Pte. McMurran and myself having remained seated in the tent. About 10 seconds later I heard the charge explode. This would be sometime shortly after 21:15 hours. The next thing I heard was Finch groaning. I rushed out of the tent to see what had happened and found Lance Cpl. Finch about 10 yards away, up against the next tent. He was lying on his back and obviously badly injured.

I told Pte. McMurran to get field-dressings and blankets, I went for the Company Medical Officer. On the way back I met Pte. Maley and told him to get more field dressings and blankets for Finch. The Medical Officer was not to be found so I went to the Sergeant's mess and told the Company Sgt. Major what had happened. He sent me to get a truck from the M.T. (motor transport) lines and he himself went down to the section lines with Sgt. Carey. I went to the M.T. lines and brought a truck over to the scene of the accident. This took me a quarter of an hour at the outside by which time a Medical Officer was attending Lance Cpl. Finch.

The Medical Officer administered morphia to the injured man, and we then took him to the British Military Hospital in the truck.

Percy Finch was originally buried at the Saugor Camp. After the war his remains were moved to Kirkee War Cemetery located close to the Indian town of Poona. To read more about Percy Finch and his accident, please follow this link: Lance Corporal Percy Finch

Seen below are some images relating to Lance Corporal Brock and his time at Saugor. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Private John Brock was sent overseas to join the 2nd Battalion who had been serving in India since 1926 and where they would remain until the outbreak of war in 1939. During the early period of his service, John Brock was employed on the North West Frontier of India and having been promoted to Lance Corporal at this time, qualified for the Indian General Service Medal with the clasp ‘North West Frontier 1937-39’.

These frontier policing duties continued on into 1940, with the 2nd Battalion Suffolk Regiment engaged in skirmishes against the tribesman of the Tochi Valley, situated on today's Afghan and Pakistan borders. Later on in the war, many men from the battalion decided to join units where they felt they stood a better chance of seeing frontline action against the real enemy, namely Japan.

This is noted in the Suffolk's Regimental history for that period:

“During the next two years (1942-43) the 2nd Battalion was to lose a high proportion of its experienced soldiers, as its role altered from that of a frontier force to one occupied in maintaining law and order within India itself."

In 1942 Lance Corporal Brock was mentioned in the 2nd Battalion's Daily Orders, dated 22nd June, under a list headed “Attachments”, as now serving in A' Company of the 13th Battalion The King’s (Liverpool) Regiment. John Brock was officially posted to the 13th King's on the 1st July 1942, joining the battalion at their Chindit training camp in the Central Provinces of India.

At the Saugor Camp he was taken on strength into the 142 Commando Platoon for Chindit Column 1 under the command of Lieutenant John Lindsay Watson, formerly of the Black Watch.

Lance Corporal Brock was one of five men from the 2nd Suffolk's to be placed into the 142 Commando Platoon for this column in 1942. He trained in the art of unarmed combat and learned how to use explosives and other clandestine weaponry. The names of three of the other men from the Suffolk's can be seen in the nominal roll for the Commando Platoon shown in the gallery below.

Training at Saugor could be a dangerous occupation, as John Brock was to discover just before Christmas 1942. One of his fellow Commandos, Percy Finch and some other men had been drinking in their tents back at the main camp lines. Lance Corporal Finch, also formerly with the Suffolk Regiment and presumably a member of Chindit Column 1, was then rather foolishly playing around with some explosives and fuses.

To cut a long story short, the explosive he was handling went off and Percy Finch was mortally wounded on the 24th December. A Court of Enquiry was held on Boxing Day and John Brock was the first witness called. Here is his testimony from that day:

About 21:00 hours on the night of December 24th 1942 I went down to Lance Cpl. Finch's tent in the section lines. On arrival there I found Lance Cpl. Finch and Pte. McMurran. We each had a small tot of rum, and followed it with a mug of beer. I should say at this stage that Lance Cpl. Finch was what would be termed as 'merry' but in full control of his senses. I suggested that we should go out for some supper, but Finch said "Well have a small bang first, and then go."

He then left the tent and returned within a few minutes with three sticks of explosives (type 808), about 5 inches of safety fuse, and a detonator. He tied the sticks of 808 together and carefully inserted the detonator, with the fuse attached into one of the sticks. The fuse had already been cut as for igniting.

There was a candle in the corner of the tent about 3 feet from the entrance flap, which was folded back. Finch declared that he would light the fuse with the candle. I suggested that he should light the fuse outside, in the correct way, with matches. He said that it would quite alright if he lit the fuse with the candle, as he could easily step outside and throw the charge to a safe distance. He then put the end of the fuse in the candle flame, but did not succeed in lighting the powder. The tip of the tarry matter of the outer casing began to smoulder. Finch stepped outside, and I thought he had thrown the charge.

A few seconds later I heard the fuse burning. I did not hear any matches struck, I could not see Finch at this time, Pte. McMurran and myself having remained seated in the tent. About 10 seconds later I heard the charge explode. This would be sometime shortly after 21:15 hours. The next thing I heard was Finch groaning. I rushed out of the tent to see what had happened and found Lance Cpl. Finch about 10 yards away, up against the next tent. He was lying on his back and obviously badly injured.

I told Pte. McMurran to get field-dressings and blankets, I went for the Company Medical Officer. On the way back I met Pte. Maley and told him to get more field dressings and blankets for Finch. The Medical Officer was not to be found so I went to the Sergeant's mess and told the Company Sgt. Major what had happened. He sent me to get a truck from the M.T. (motor transport) lines and he himself went down to the section lines with Sgt. Carey. I went to the M.T. lines and brought a truck over to the scene of the accident. This took me a quarter of an hour at the outside by which time a Medical Officer was attending Lance Cpl. Finch.

The Medical Officer administered morphia to the injured man, and we then took him to the British Military Hospital in the truck.

Percy Finch was originally buried at the Saugor Camp. After the war his remains were moved to Kirkee War Cemetery located close to the Indian town of Poona. To read more about Percy Finch and his accident, please follow this link: Lance Corporal Percy Finch

Seen below are some images relating to Lance Corporal Brock and his time at Saugor. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Chindit Column 1 was commanded by Major George Dunlop MC, formerly of the Royal Scots. Major Dunlop's unit formed part of Southern Group on Operation Longcloth, which consisted of Gurkha Columns 1 and 2, and Southern Group Head Quarters. Southern Group was used by Wingate as a decoy on the operation, the intention being for them to draw attention away from the main Chindit columns of Northern Group whilst they crossed the Chindwin River and moved quickly east toward their targets along the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktang. Their orders were to march toward their own prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. These supplementary units were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their objectives.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Dunlop was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst Column 2 under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Group HQ were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also lost radio contact with each other. Column 2 and Group Head Quarters, in the black of night stumbled into an enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment.

The Chindits were taken by surprise during that terrible night and suffered many casualties. After dispersal was called and amongst much confusion the men disengaged from the enemy at Kyaikthin and withdrew into the surrounding jungle. Many of the surviving Chindits mistakenly turned west and set off back to India. Some of the remainder, having received the correct instructions moved on eastwards toward the Irrawaddy River. It was here that they joined up with Major Dunlop and Column 1 on about the 7/8th March.

From this moment on the two groups moved as one unit, with Dunlop sharing command with Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander, the overall commander of Southern Group. By the time full dispersal was called by Brigadier Wingate on the 29th March, Column 1 found themselves the furthest east of any of the surviving Chindit units. After eventually deciding to return to India rather than try for the Chinese Yunnan Borders, the group suffered a long a arduous journey back, including having to re-cross both the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. Over the coming weeks the column lost many men, some through sharp engagements with the enemy, but the majority simply due to thirst, starvation and total exhaustion.

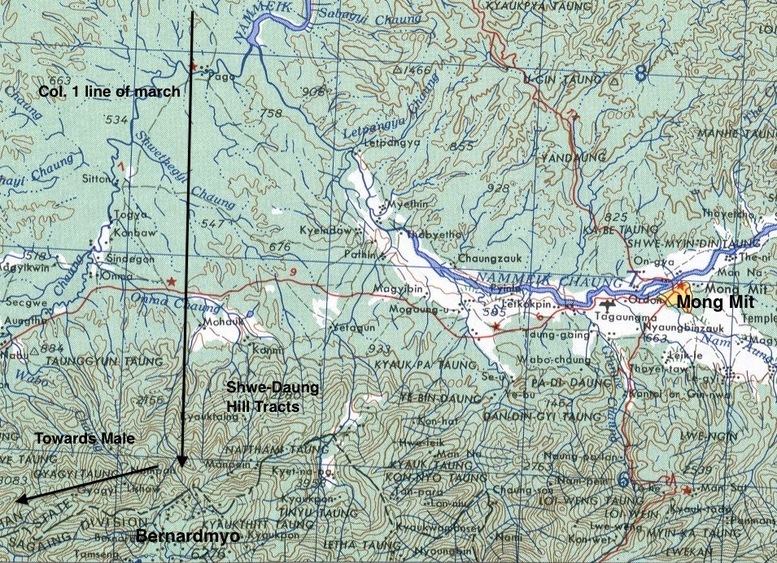

Around the first week of April the column were in the area around the Burmese town of Mong Mit. They moved south towards the Mong Mit-Male motor road, keeping the Shweli River on their left-handside. Once over the road the unit moved up into the hill tracts of the Shwe-Daung district. It was at this point that they were ambushed by the Japanese. The 142 Commando Platoon, now led by 2nd Lieutenant John Nealon, would have been involved in much of the fighting that day, possibly acting as rearguard as the column attempted to climb away from the encircling Japanese.

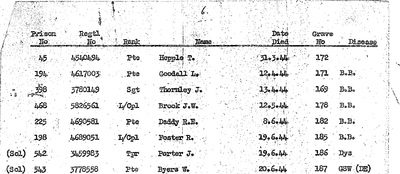

The Chindits suffered many casualties during their retreat into the Shwe-Daung Hills. It seems likely to me that this was also the point at which John Brock was lost to his unit in 1943. John became a prisoner of war, according to his POW index card on the 18th April, at a place called Moregumito. I have tried on many occasions to locate this Burmese village, scouring maps and searching place names on the internet, but to no avail. As Moregumito is a direct translation from the Japanese Kanji characters present on his POW index card, I now wonder if it actually refers to the town of Mong Mit, which was the largest town in the vicinity of his capture. Sadly, we will probably never know for sure.

Seen below is a map, showing Column 1's line of march during the first week of April 1943. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktang. Their orders were to march toward their own prime objective, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. These supplementary units were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their objectives.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Dunlop was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst Column 2 under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Group HQ were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also lost radio contact with each other. Column 2 and Group Head Quarters, in the black of night stumbled into an enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment.

The Chindits were taken by surprise during that terrible night and suffered many casualties. After dispersal was called and amongst much confusion the men disengaged from the enemy at Kyaikthin and withdrew into the surrounding jungle. Many of the surviving Chindits mistakenly turned west and set off back to India. Some of the remainder, having received the correct instructions moved on eastwards toward the Irrawaddy River. It was here that they joined up with Major Dunlop and Column 1 on about the 7/8th March.

From this moment on the two groups moved as one unit, with Dunlop sharing command with Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander, the overall commander of Southern Group. By the time full dispersal was called by Brigadier Wingate on the 29th March, Column 1 found themselves the furthest east of any of the surviving Chindit units. After eventually deciding to return to India rather than try for the Chinese Yunnan Borders, the group suffered a long a arduous journey back, including having to re-cross both the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. Over the coming weeks the column lost many men, some through sharp engagements with the enemy, but the majority simply due to thirst, starvation and total exhaustion.

Around the first week of April the column were in the area around the Burmese town of Mong Mit. They moved south towards the Mong Mit-Male motor road, keeping the Shweli River on their left-handside. Once over the road the unit moved up into the hill tracts of the Shwe-Daung district. It was at this point that they were ambushed by the Japanese. The 142 Commando Platoon, now led by 2nd Lieutenant John Nealon, would have been involved in much of the fighting that day, possibly acting as rearguard as the column attempted to climb away from the encircling Japanese.

The Chindits suffered many casualties during their retreat into the Shwe-Daung Hills. It seems likely to me that this was also the point at which John Brock was lost to his unit in 1943. John became a prisoner of war, according to his POW index card on the 18th April, at a place called Moregumito. I have tried on many occasions to locate this Burmese village, scouring maps and searching place names on the internet, but to no avail. As Moregumito is a direct translation from the Japanese Kanji characters present on his POW index card, I now wonder if it actually refers to the town of Mong Mit, which was the largest town in the vicinity of his capture. Sadly, we will probably never know for sure.

Seen below is a map, showing Column 1's line of march during the first week of April 1943. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

As mentioned earlier, we cannot be sure of the exact details of John Brock's capture. After separation from his column unit, he may well have been alone and on the run from the Japanese for several days. Column 1 re-crossed the Irrawaddy River at a place called Sinhnyat on approximately the 20th April 1943, it is possible that he was lost to the unit just a few days previously.

By late April 1943 the Japanese had captured around 200 Chindit soldiers from all over the area of the Irrawaddy-Shweli confluence. A decision was made to take all these men to a concentration camp at the hill station town of Maymyo. John was sent to Maymyo, located some 50 miles east of Mandalay, where he met up with his Chindit comrades now held in Japanese hands.

The Chindit POW's were held at this first concentration camp until roughly the end of May, as June arrived the Japanese began moving the prisoners down to Rangoon Central Jail. This journey was mostly undertaken by train. The men were herded into metal cattle trucks and spent a very uncomfortable few days making the 400 mile journey south to the capital city. The Japanese only used the railway at night for fear of Allied air-raids during daylight hours. This is why the journey took so long, a factor which would exacerbate the problem of the cramped and unsanitary conditions experienced inside these wagons, filled with the already sick and stricken Chindits.

On arrival at Rangoon the Chindits generally spent a few weeks in Block 5, the solitary confinement wing of the jail. Lower ranked soldiers were then moved out to Block 6, which basically became the domain of the men captured from Operation Longcloth. There was no hospital inside the jail and no Medical Officer or doctor was available to Block 6 at this time. This disastrous consequence led to the death of many of the already exhausted and malnourished Chindits, with almost one-third of their number perishing within the first few months.

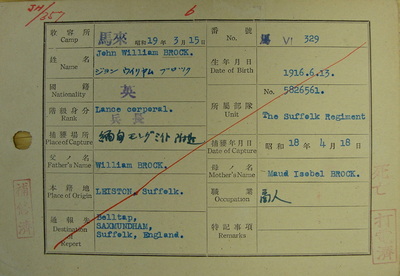

Lance Corporal Brock was held in Block 6 of the jail for the first few months of his incarceration. He was given the POW number 329 (see his POW index card below) and would recite this number in Japanese at every 'tenko' or roll call. Presumably, his physical condition at this point must have been fairly satisfactory, resulting in a move to Block 3 as 1943 turned into 1944. In most cases as a POW, if a Chindit Other Rank survived the first six months inside Rangoon and settled down to prison life, he tended to endure the full experience and live to see his home and family again.

Understanding this fact, makes it all the more poignant, that John Brock did not make it home in 1945, dying instead, inside the makeshift hospital room in Block 6, suffering from the ravages of beri beri. John had lasted longer than most, but succumbed to the disease that accounted for the vast majority of deaths inside Rangoon Jail during the years of WW2. Beri beri is a condition brought on by a lack of Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) in a persons diet and was common inside Rangoon Jail due to rations comprised almost exclusively of polish white rice.

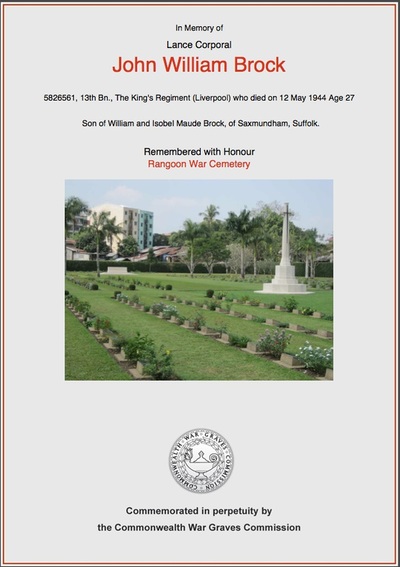

John died on the 12th May 1944, having not long past the landmark of his first full year as a prisoner of war. He was buried in the first instance at the English Cantonment Cemetery on the eastern outskirts of the city, close to the Royal Lakes. His grave number in the cemetery was recorded as 178. After the war, the Imperial War Graves Commission moved all these burials over to the newly constructed, Rangoon War Cemetery.

To view Lance Corporal Brock's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2259758/BROCK,%20JOHN%20WILLIAM

John William Brock is also remembered upon his home town war memorial at Saxmundham and inside St. John the Baptist Church situated on the south-eastern outskirts of the town. Seen below are some more images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The Longcloth journey of Lance Corporal John William Brock has been an intrinsic part of my research, ever since I first discovered that his missing in action date, the 18th April 1943, was the same as my own grandfather's. Back in July 2007 I matched Brock and two other men; James Ambrose and William Jordan, with my grandfather as men who were all reported missing on the same day. At that time I had no idea which column my grandfather belonged to and possessed little information about the other three men, apart from John Brock's POW index card and a brief mention of William Jordan in the book 'March or Die' by Phil Chinnery.

When the 'Missing in action' witness reports were opened at the National Archives in the autumn of 2010, my theory was proved two-thirds correct; Ambrose, Jordan and Howney were all from Column 5 and had been part of a small group of six Chindits attempting to exit Burma via the Chinese Yunnan Borders. John Brock, a Commando from Column 1 was not with them at dispersal, but all four would meet up as POW's and sadly perish inside Rangoon Jail.

By late April 1943 the Japanese had captured around 200 Chindit soldiers from all over the area of the Irrawaddy-Shweli confluence. A decision was made to take all these men to a concentration camp at the hill station town of Maymyo. John was sent to Maymyo, located some 50 miles east of Mandalay, where he met up with his Chindit comrades now held in Japanese hands.

The Chindit POW's were held at this first concentration camp until roughly the end of May, as June arrived the Japanese began moving the prisoners down to Rangoon Central Jail. This journey was mostly undertaken by train. The men were herded into metal cattle trucks and spent a very uncomfortable few days making the 400 mile journey south to the capital city. The Japanese only used the railway at night for fear of Allied air-raids during daylight hours. This is why the journey took so long, a factor which would exacerbate the problem of the cramped and unsanitary conditions experienced inside these wagons, filled with the already sick and stricken Chindits.

On arrival at Rangoon the Chindits generally spent a few weeks in Block 5, the solitary confinement wing of the jail. Lower ranked soldiers were then moved out to Block 6, which basically became the domain of the men captured from Operation Longcloth. There was no hospital inside the jail and no Medical Officer or doctor was available to Block 6 at this time. This disastrous consequence led to the death of many of the already exhausted and malnourished Chindits, with almost one-third of their number perishing within the first few months.

Lance Corporal Brock was held in Block 6 of the jail for the first few months of his incarceration. He was given the POW number 329 (see his POW index card below) and would recite this number in Japanese at every 'tenko' or roll call. Presumably, his physical condition at this point must have been fairly satisfactory, resulting in a move to Block 3 as 1943 turned into 1944. In most cases as a POW, if a Chindit Other Rank survived the first six months inside Rangoon and settled down to prison life, he tended to endure the full experience and live to see his home and family again.

Understanding this fact, makes it all the more poignant, that John Brock did not make it home in 1945, dying instead, inside the makeshift hospital room in Block 6, suffering from the ravages of beri beri. John had lasted longer than most, but succumbed to the disease that accounted for the vast majority of deaths inside Rangoon Jail during the years of WW2. Beri beri is a condition brought on by a lack of Vitamin B1 (Thiamine) in a persons diet and was common inside Rangoon Jail due to rations comprised almost exclusively of polish white rice.

John died on the 12th May 1944, having not long past the landmark of his first full year as a prisoner of war. He was buried in the first instance at the English Cantonment Cemetery on the eastern outskirts of the city, close to the Royal Lakes. His grave number in the cemetery was recorded as 178. After the war, the Imperial War Graves Commission moved all these burials over to the newly constructed, Rangoon War Cemetery.

To view Lance Corporal Brock's CWGC details, please click on the following link:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2259758/BROCK,%20JOHN%20WILLIAM

John William Brock is also remembered upon his home town war memorial at Saxmundham and inside St. John the Baptist Church situated on the south-eastern outskirts of the town. Seen below are some more images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The Longcloth journey of Lance Corporal John William Brock has been an intrinsic part of my research, ever since I first discovered that his missing in action date, the 18th April 1943, was the same as my own grandfather's. Back in July 2007 I matched Brock and two other men; James Ambrose and William Jordan, with my grandfather as men who were all reported missing on the same day. At that time I had no idea which column my grandfather belonged to and possessed little information about the other three men, apart from John Brock's POW index card and a brief mention of William Jordan in the book 'March or Die' by Phil Chinnery.

When the 'Missing in action' witness reports were opened at the National Archives in the autumn of 2010, my theory was proved two-thirds correct; Ambrose, Jordan and Howney were all from Column 5 and had been part of a small group of six Chindits attempting to exit Burma via the Chinese Yunnan Borders. John Brock, a Commando from Column 1 was not with them at dispersal, but all four would meet up as POW's and sadly perish inside Rangoon Jail.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, January 2015.