Lance Corporal Fred Nightingale

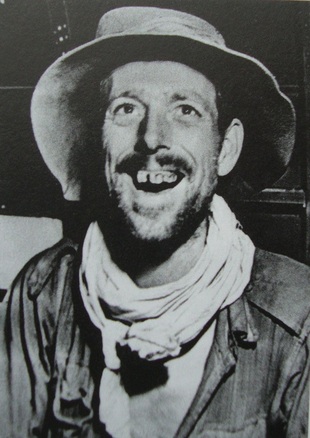

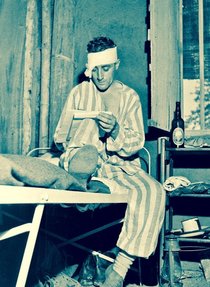

L. Corp. Nightingale seen aboard the Dakota rescue plane.

L. Corp. Nightingale seen aboard the Dakota rescue plane.

On the 28th April 1943, a small group of wretched looking men huddled together in the bowels of a DC 3 transporter plane, they were heading west towards India. They were the very sick and wounded from Major Scott's Chindit Column number 8. I use the word 'very' because at that time most men from the column were suffering in one way or another from the ravages of over ten weeks in the Burmese jungle.

As the Dakota's Flight Sergeant offered these exhausted human frames some much needed and sweet tasting tea, one man from Lancaster looked across at his pal Jim and simply touched his arm. He knew that they were probably the luckiest men in Burma at that precise moment in time.

Fred Nightingale had been with Major Scott since the early training days at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces. Scott had known the jovial Lancastrian for quite sometime as both had travelled over to India with the battalion aboard the troopship 'Oronsay' in late 1941. It was with great concern, that Major Scott now watched his men fall by the wayside on the tracks of the Burmese jungle, worn out and weary from their trials and experiences on Operation Longcloth.

Fred was suffering from jungle sores, these were normally caused by the tiniest of scratches or insect bite, but turned into horrifically large ulcerated areas of infected flesh. By now malaria also plagued his every move and the normally resilient Lancastrian knew his chances of survival were wearing as thin as his emaciated body. His morale was not boosted by the sight of his comrades dropping out in twos and threes from the column's line of march.

Column 8 had been moving almost continuously since dispersal had been called at the end of March. Now the full effects of two difficult river crossings, insufficient rations and debilitating disease were threatening the disintegration of this unit. After what seemed like an eternity trapped within the envelope of dense and dark jungle tracks a shaft of light appeared in the near distance. The reconnaissance scouts from the column came back to their commander and reported that the unit had reached the location of the the next planned supply drop. It was a large open space, much bigger than the brigade maps had suggested, Scott looked out across the meadow and an idea took hold in his mind. 'Could a plane land here?'

Many books have recounted the story of the colloquially named 'Piccadilly Dakota' incident. It had become known as Piccadilly because the open space was scheduled to be used as one of the Chindit landing strips by the following years much larger invasion force. Due to events at the time this in fact never materialised, but the nickname stuck.

There now follows a transcription of the events leading up to and including the Dakota airlift of seventeen injured and sick Chindits in late April 1943. It is taken from the book 'Wingate's Lost Brigade', written by Phil Chinnery, but is in fact an amalgamation of first hand accounts given by men and journalists present at the time. My thanks must go to Philip for allowing me to reproduce his text on these pages.

Firstly, from the personal diary of Private Dennis Brown, remembering the speech that Lieutenant Colonel Cooke had made to the men, the day after they crossed the river Irrawaddy for the second time:

"It was not very encouraging. The gist of it was that he had orders from HQ to make the return journey to India, but that if he had his way, we would fight on to the last man and last bullet! You can image how that went down with the rank and file! I did hear that at one time he suggested that the RAF should drop soap, towels and razors, until it was pointed out that you can't eat them! The next day, our last mule, carrying the radio, keeled over and died. We radioed for one last supply drop, smashed the set and continued on our journey."

On 23rd April, Corporal Worsley fell by the side of the track. Suffering from acute jungle sores and with legs swollen to twice their normal size he could go no further. His platoon stayed behind to guide him to the next bivouac, but he would not budge and was left to follow in his own time. By now the troops were completely out of rations and water was becoming scarce. The next day Corporal Walker fell out from exhaustion. He had been suffering from dysentery for the past two weeks. Three Gurkhas fell out with him.

Company Quartermaster Sergeant Duncan Bett later recalled:

"We were all scared of being left behind. When we dropped down exhausted at night it was so dark under the jungle canopy that you could not see your hand at the end of your nose. It was like the tomb. I remember waking up suddenly once and I couldn't see a thing or hear a sound. No mules, no sentries, nothing. I thought I had been left behind when the column moved on before dawn. I scrabbled around in a panic, feeling for another body and the relief was indescribable when I felt someone else there on the ground. It seems hard to believe, but several men were left behind in the dark. Presumably they were so exhausted they didn't wake up and were not missed in the confusion when the column moved off."

The rendezvous for the next supply drop was a clearing near Bhamo, a large town 150 miles behind Japanese lines. As he marched along through the dark jungle, Major Scott noticed that the track ahead of him was growing lighter, as if he were approaching the end of a tunnel. Soon he was standing at the edge of the jungle, looking out on what was probably the largest patch of open ground in northern Burma. The following day, 25th April, the Chindits scanned the sky, praying for a supply drop. Captain Johnny Carroll, the Support Group Commander, was one of them:

"Colonel Cooke agreed that we should work out the best area for a supply drop using white maps and socks. I suggested that we mark out PLANE LAND HERE NOW, Colonel Cooke said that we could not issue orders to the RAF and should therefore mark out REQUEST PLANE LAND HERE NOW. As the noise of a supply plane could already be heard, I suggested we start without the word REQUEST and add it later if time permitted."

The planes came over and dropped supplies to the waiting Chindits. Tommy guns, waterproof capes, bully beef, cheese and chocolate, and five days rations floated to the ground. One of the planes circled lower and saw the message. Flying Officer 'Lummie' Lord lowered his undercarriage and tried to land, but the area was too short and too rough to put down safely. The plane then made off to the west in a great hurry.

Shortly afterwards a thunderstorm burst upon them, hailstones the size of marbles fell and the troops started collecting them to eat. Only half of the rations had arrived, so the Chindits moved into bivouac to cook what they had and hope that the planes would return later. At 0600 hours the next day the planes returned and dropped enough rations for five more days. Another charged battery arrived, but there was no wireless now to send messages. They were also in desperate need of new clothing as their shirts and trousers were dropping to pieces. Many men had no sleeves to their shirts and no seats to their trousers, and many pairs of trousers had been cut down as shorts, with the result that at night the men were pestered by mosquitoes.

As the Dakota's Flight Sergeant offered these exhausted human frames some much needed and sweet tasting tea, one man from Lancaster looked across at his pal Jim and simply touched his arm. He knew that they were probably the luckiest men in Burma at that precise moment in time.

Fred Nightingale had been with Major Scott since the early training days at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces. Scott had known the jovial Lancastrian for quite sometime as both had travelled over to India with the battalion aboard the troopship 'Oronsay' in late 1941. It was with great concern, that Major Scott now watched his men fall by the wayside on the tracks of the Burmese jungle, worn out and weary from their trials and experiences on Operation Longcloth.

Fred was suffering from jungle sores, these were normally caused by the tiniest of scratches or insect bite, but turned into horrifically large ulcerated areas of infected flesh. By now malaria also plagued his every move and the normally resilient Lancastrian knew his chances of survival were wearing as thin as his emaciated body. His morale was not boosted by the sight of his comrades dropping out in twos and threes from the column's line of march.

Column 8 had been moving almost continuously since dispersal had been called at the end of March. Now the full effects of two difficult river crossings, insufficient rations and debilitating disease were threatening the disintegration of this unit. After what seemed like an eternity trapped within the envelope of dense and dark jungle tracks a shaft of light appeared in the near distance. The reconnaissance scouts from the column came back to their commander and reported that the unit had reached the location of the the next planned supply drop. It was a large open space, much bigger than the brigade maps had suggested, Scott looked out across the meadow and an idea took hold in his mind. 'Could a plane land here?'

Many books have recounted the story of the colloquially named 'Piccadilly Dakota' incident. It had become known as Piccadilly because the open space was scheduled to be used as one of the Chindit landing strips by the following years much larger invasion force. Due to events at the time this in fact never materialised, but the nickname stuck.

There now follows a transcription of the events leading up to and including the Dakota airlift of seventeen injured and sick Chindits in late April 1943. It is taken from the book 'Wingate's Lost Brigade', written by Phil Chinnery, but is in fact an amalgamation of first hand accounts given by men and journalists present at the time. My thanks must go to Philip for allowing me to reproduce his text on these pages.

Firstly, from the personal diary of Private Dennis Brown, remembering the speech that Lieutenant Colonel Cooke had made to the men, the day after they crossed the river Irrawaddy for the second time:

"It was not very encouraging. The gist of it was that he had orders from HQ to make the return journey to India, but that if he had his way, we would fight on to the last man and last bullet! You can image how that went down with the rank and file! I did hear that at one time he suggested that the RAF should drop soap, towels and razors, until it was pointed out that you can't eat them! The next day, our last mule, carrying the radio, keeled over and died. We radioed for one last supply drop, smashed the set and continued on our journey."

On 23rd April, Corporal Worsley fell by the side of the track. Suffering from acute jungle sores and with legs swollen to twice their normal size he could go no further. His platoon stayed behind to guide him to the next bivouac, but he would not budge and was left to follow in his own time. By now the troops were completely out of rations and water was becoming scarce. The next day Corporal Walker fell out from exhaustion. He had been suffering from dysentery for the past two weeks. Three Gurkhas fell out with him.

Company Quartermaster Sergeant Duncan Bett later recalled:

"We were all scared of being left behind. When we dropped down exhausted at night it was so dark under the jungle canopy that you could not see your hand at the end of your nose. It was like the tomb. I remember waking up suddenly once and I couldn't see a thing or hear a sound. No mules, no sentries, nothing. I thought I had been left behind when the column moved on before dawn. I scrabbled around in a panic, feeling for another body and the relief was indescribable when I felt someone else there on the ground. It seems hard to believe, but several men were left behind in the dark. Presumably they were so exhausted they didn't wake up and were not missed in the confusion when the column moved off."

The rendezvous for the next supply drop was a clearing near Bhamo, a large town 150 miles behind Japanese lines. As he marched along through the dark jungle, Major Scott noticed that the track ahead of him was growing lighter, as if he were approaching the end of a tunnel. Soon he was standing at the edge of the jungle, looking out on what was probably the largest patch of open ground in northern Burma. The following day, 25th April, the Chindits scanned the sky, praying for a supply drop. Captain Johnny Carroll, the Support Group Commander, was one of them:

"Colonel Cooke agreed that we should work out the best area for a supply drop using white maps and socks. I suggested that we mark out PLANE LAND HERE NOW, Colonel Cooke said that we could not issue orders to the RAF and should therefore mark out REQUEST PLANE LAND HERE NOW. As the noise of a supply plane could already be heard, I suggested we start without the word REQUEST and add it later if time permitted."

The planes came over and dropped supplies to the waiting Chindits. Tommy guns, waterproof capes, bully beef, cheese and chocolate, and five days rations floated to the ground. One of the planes circled lower and saw the message. Flying Officer 'Lummie' Lord lowered his undercarriage and tried to land, but the area was too short and too rough to put down safely. The plane then made off to the west in a great hurry.

Shortly afterwards a thunderstorm burst upon them, hailstones the size of marbles fell and the troops started collecting them to eat. Only half of the rations had arrived, so the Chindits moved into bivouac to cook what they had and hope that the planes would return later. At 0600 hours the next day the planes returned and dropped enough rations for five more days. Another charged battery arrived, but there was no wireless now to send messages. They were also in desperate need of new clothing as their shirts and trousers were dropping to pieces. Many men had no sleeves to their shirts and no seats to their trousers, and many pairs of trousers had been cut down as shorts, with the result that at night the men were pestered by mosquitoes.

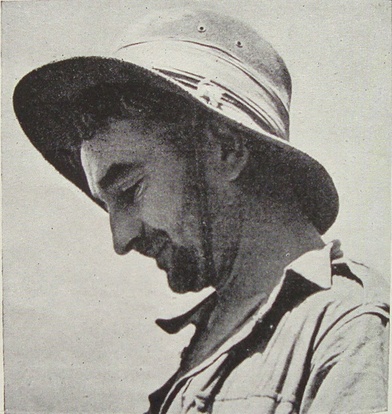

Sgt. Bert Fitton.

Sgt. Bert Fitton.

The book description continues:

During the day the men were sent down to a nearby stream to bathe and to try to remove some of the lice which plagued them. On 27th April, a message was dropped to the men: 'Mark out 1,200 yard landing ground to hold twelve-ton transport.' A second message gave details of the route taken by Major Fergusson of 5 Column who had by now found his way back to India.

At dawn on 28th April, the Dakota rescue plane took off, escorted by eight Mohawk fighters. Flying Officer Michael Vlasto and his crew had been given a pair of Army boots each to walk home in if the plane did not land safely. When he reached the clearing, a white line was marked out on the field, together with a message: 'LAND ON WHITE LINE. GROUND THERE V.G.' The crew braced themselves as Vlasto made his approach. They touched down and the pilot hit the brakes, coming to a halt just at the end of the strip.

The plane was soon surrounded by bearded, malnourished men. But who would go out in the plane? There was only one answer: the wounded would go out first — Corporal Jimmy Walker of 7 Column, who had dropped out of the column with dysentery and an infected hip, but had dragged himself along behind them; Private Jim Suddery who had been shot in the back, the bullet going right through him; and Private Robert Hulse, shaken every couple of hours by violent fits of vomiting.

Lieutenant Colonel Cooke also went aboard. This was a controversial decision which provoked much discussion among those left behind, that being, should the most senior soldier from the group leave the field ahead of his men.

Eighteen men were counted into the plane and the cargo door was closed behind them. One of them, Corporal Bert Fitton, who played left half in the company football team, helped Lieutenant Colonel Cooke and the sick and wounded into the plane, only to find himself locked in and about to take off and had to plead with the pilot to let him out. Back on the ground he told Major Scott, 'I came in on my feet and I'd like to go out the same way,' and rejoined his comrades.

Michael Vlasto gripped the control column as the end of the field rushed towards his plane. The runway was too short and they were overloaded. With knuckles white and his face dripping with sweat, he pulled back on the stick and the plane staggered into the air, brushing the treetops below. 'God bless number eighteen,' he said.

For the record, in addition to those mentioned above, the other lucky ones included Privates Lambert, Walsh (7 Col), Yates, Wilson and Crowhurst; Lance Corporals Nightingale and Rogerson; Sergeants Flowers, Aubrey, McElroy, Whittaker and Berry; Tun Tin, one of the Burma Riflemen, who was suffering from malaria and Rifleman Kulbahadur of the Gurkhas.

NB: Sadly, the incredibly brave and fine man that was Bert Fitton, never made it out of Burma in 1943, he was lost just a few days later, killed in action during an ambush by a Japanese patrol. Here are his and Corporal Edward Worsley's CWGC details:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/1292591/FITTON,%20HERBERT

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2528615/WORSLEY,%20EDWARD

During the day the men were sent down to a nearby stream to bathe and to try to remove some of the lice which plagued them. On 27th April, a message was dropped to the men: 'Mark out 1,200 yard landing ground to hold twelve-ton transport.' A second message gave details of the route taken by Major Fergusson of 5 Column who had by now found his way back to India.

At dawn on 28th April, the Dakota rescue plane took off, escorted by eight Mohawk fighters. Flying Officer Michael Vlasto and his crew had been given a pair of Army boots each to walk home in if the plane did not land safely. When he reached the clearing, a white line was marked out on the field, together with a message: 'LAND ON WHITE LINE. GROUND THERE V.G.' The crew braced themselves as Vlasto made his approach. They touched down and the pilot hit the brakes, coming to a halt just at the end of the strip.

The plane was soon surrounded by bearded, malnourished men. But who would go out in the plane? There was only one answer: the wounded would go out first — Corporal Jimmy Walker of 7 Column, who had dropped out of the column with dysentery and an infected hip, but had dragged himself along behind them; Private Jim Suddery who had been shot in the back, the bullet going right through him; and Private Robert Hulse, shaken every couple of hours by violent fits of vomiting.

Lieutenant Colonel Cooke also went aboard. This was a controversial decision which provoked much discussion among those left behind, that being, should the most senior soldier from the group leave the field ahead of his men.

Eighteen men were counted into the plane and the cargo door was closed behind them. One of them, Corporal Bert Fitton, who played left half in the company football team, helped Lieutenant Colonel Cooke and the sick and wounded into the plane, only to find himself locked in and about to take off and had to plead with the pilot to let him out. Back on the ground he told Major Scott, 'I came in on my feet and I'd like to go out the same way,' and rejoined his comrades.

Michael Vlasto gripped the control column as the end of the field rushed towards his plane. The runway was too short and they were overloaded. With knuckles white and his face dripping with sweat, he pulled back on the stick and the plane staggered into the air, brushing the treetops below. 'God bless number eighteen,' he said.

For the record, in addition to those mentioned above, the other lucky ones included Privates Lambert, Walsh (7 Col), Yates, Wilson and Crowhurst; Lance Corporals Nightingale and Rogerson; Sergeants Flowers, Aubrey, McElroy, Whittaker and Berry; Tun Tin, one of the Burma Riflemen, who was suffering from malaria and Rifleman Kulbahadur of the Gurkhas.

NB: Sadly, the incredibly brave and fine man that was Bert Fitton, never made it out of Burma in 1943, he was lost just a few days later, killed in action during an ambush by a Japanese patrol. Here are his and Corporal Edward Worsley's CWGC details:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/1292591/FITTON,%20HERBERT

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2528615/WORSLEY,%20EDWARD

The book transcription concludes:

The Chindits hoped that more planes would be sent to take them all home and divided themselves into groups in anticipation. But it was not to be. After receiving reports from Lieutenant Colonel Cooke and the pilot of the Dakota, the commander of IV Corps decided it was too risky to repeat the operation. Major Scott had been relieved of his wounded and they had enough supplies to last them three weeks. They also had Fergusson's details of his escape route, so they were in a much better position to walk out. The next day a plane appeared overhead and dropped a message to Major Scott, which read:

"After very careful consideration I have reluctantly decided not to allow the pilot to take the risk of attempting to land his plane again. Apart from the actual landing risks there is considerable danger of interference from Japanese land and air forces. This must, I realise, be a very great disappointment to you and all your men. We will do all in our power to help you, and patrols are now operating east of the Chindwin to meet you. I have no doubt at all that you will be able to reach the Chindwin safely by one of the two routes given you by Fergusson. Have just heard Wingate crossed the Chindwin today. Hope to see you soon. G. Scoones, Major General, Corps HQ 29th April 1943."

Before the plane departed it parachuted more supplies to the men, including a large bundle of boots. The column, now down to 159 disappointed men, shouldered their bulging packs and continued their journey.

We will leave the book 'Wingate's Lost Brigade' at this point and return to the Dakota.

The men made their short air journey back to India, where they were met at Imphal airfield by Brigade-Major George Bromhead, himself only recently back from serving on Operation Longcloth having marched out with men of Column 4. They were escorted to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station at Imphal and into the caring arms of Matron Agnes McGeary.

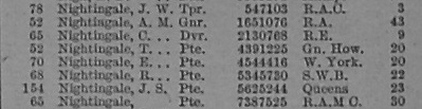

Listed below is the exact nominal roll of the seventeen men flown to safety by Flight Officer Michael Vlasto, as recorded in the 8 Column's War Diary at the time:

The Chindits hoped that more planes would be sent to take them all home and divided themselves into groups in anticipation. But it was not to be. After receiving reports from Lieutenant Colonel Cooke and the pilot of the Dakota, the commander of IV Corps decided it was too risky to repeat the operation. Major Scott had been relieved of his wounded and they had enough supplies to last them three weeks. They also had Fergusson's details of his escape route, so they were in a much better position to walk out. The next day a plane appeared overhead and dropped a message to Major Scott, which read:

"After very careful consideration I have reluctantly decided not to allow the pilot to take the risk of attempting to land his plane again. Apart from the actual landing risks there is considerable danger of interference from Japanese land and air forces. This must, I realise, be a very great disappointment to you and all your men. We will do all in our power to help you, and patrols are now operating east of the Chindwin to meet you. I have no doubt at all that you will be able to reach the Chindwin safely by one of the two routes given you by Fergusson. Have just heard Wingate crossed the Chindwin today. Hope to see you soon. G. Scoones, Major General, Corps HQ 29th April 1943."

Before the plane departed it parachuted more supplies to the men, including a large bundle of boots. The column, now down to 159 disappointed men, shouldered their bulging packs and continued their journey.

We will leave the book 'Wingate's Lost Brigade' at this point and return to the Dakota.

The men made their short air journey back to India, where they were met at Imphal airfield by Brigade-Major George Bromhead, himself only recently back from serving on Operation Longcloth having marched out with men of Column 4. They were escorted to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station at Imphal and into the caring arms of Matron Agnes McGeary.

Listed below is the exact nominal roll of the seventeen men flown to safety by Flight Officer Michael Vlasto, as recorded in the 8 Column's War Diary at the time:

Sergeant Jack Berry who served under Major Scott again in 1944.

Sergeant Jack Berry who served under Major Scott again in 1944.

The following wounded and sick personnel were emplaned.

Lt.-Col. S.A. Cooke.

3657813 Pte. N. Lambert 8 Coln. - wounded in chest.

3861783 Pte. H. Walsh 7 Coln. - injured knee.

3968528 Pte. J. Suddery 8 Coln. - wounded chest & arm.

3781410 L/C. F. Nightingale 8 Coln. - sick.

3780181 Pte. R. Hulse 8 Coln. - rupture.

3781736 Pte. J. Yates 8 Coln. - wounded hand.

3460507 Pte. J. Wilson 8 Coln. - sick.

3778705 L/C. J. Rogerson 8 Coln. - sick.

4197265 L/S. L. Flowers 8 Coln. - sick.

3968495 Pte. W. Crowhurst 8 Coln.

4189704 L/S. T. Aubrey 8 Coln. - wounded arm. 3189237 Cpl. J. Walker 7 Coln. - dysentery.

7016701 Sgt. E. Whittaker Group H.Q. 3823 Rfm. Tun Tin 2/Burma Rifles - malaria.

3780480 Sgt. J. Berry Group H.Q. 10468 Rfm. Kalabahadur 3/2 G. R.

3781595 L/S. L. McElroy 8 Coln. - wounded arm.

NB: Sergeant Jack Berry would serve with Lieutenant Colonel Scott again in the following years Chindit expedition, sadly he was killed on the 20th May 1944 whilst with the 1st Battalion of the King's Regiment. He would be amongst the elite group of men to serve in both Wingate operations. Here are his CWGC details:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2505157/BERRY,%20JACK

On board Dakota FD-781, part of 31 Squadron's complement at Agartala air base in 1943, was war correspondent William Vandivert. He had heard about the imminent rescue of the stranded Chindits and had tagged along with the Dakota crew looking for the chance of a good story for the readers of the popular 'Illustrated' magazine. Returning primarily to the story of Fred Nightingale, here is a transcription of Vandivert's article from the magazine in relation to his meeting with Fred aboard the plane.

From Illustrated magazine issue published 10th July 1943, with William Vandivert narrating:

Our supplies had saved them. Sunday's drop had turned the tide of fortune. Some stragglers had come back up. With rations and unexpected rest they now were fit again for the march to India, racing against time, monsoons and impassable rivers. That was the story.

The pilot then gave permission to smoke. The corporal on the end seat, Fred Nightingale, of Lancaster, handed me a battered tin, saying : "Here, have one of mine. They fly them specially from India for me."

A chunk of white parachute around Nightingale's neck made him look garish. Ulcers had worn him thin. The last two days to the rendezvous had been his last effort, and he had known it; will power had just kept him moving. He had straggled back to the rear of the column and seen men dropping by the dusty jungle track. It happened quietly.

One chum, with jungle sores deeply infecting his legs, just couldn't lift them again. He had dropped, saying softly : "Well, I guess I've had it." The column had moved slowly on and dust had settled.

Another ruptured soldier sat silently forward, elbows on knees. I asked him about the jungle and he only said: "It's bitter cruel." He was Corporal Jimmy Walker, who had dropped two days before the rendezvous with dysentery and infected hips. It was only his great will that had brought him hobbling back in just the day before.

From Illustrated magazine issue published 10th July 1943, with William Vandivert narrating:

Our supplies had saved them. Sunday's drop had turned the tide of fortune. Some stragglers had come back up. With rations and unexpected rest they now were fit again for the march to India, racing against time, monsoons and impassable rivers. That was the story.

The pilot then gave permission to smoke. The corporal on the end seat, Fred Nightingale, of Lancaster, handed me a battered tin, saying : "Here, have one of mine. They fly them specially from India for me."

A chunk of white parachute around Nightingale's neck made him look garish. Ulcers had worn him thin. The last two days to the rendezvous had been his last effort, and he had known it; will power had just kept him moving. He had straggled back to the rear of the column and seen men dropping by the dusty jungle track. It happened quietly.

One chum, with jungle sores deeply infecting his legs, just couldn't lift them again. He had dropped, saying softly : "Well, I guess I've had it." The column had moved slowly on and dust had settled.

Another ruptured soldier sat silently forward, elbows on knees. I asked him about the jungle and he only said: "It's bitter cruel." He was Corporal Jimmy Walker, who had dropped two days before the rendezvous with dysentery and infected hips. It was only his great will that had brought him hobbling back in just the day before.

Fred Nightingale in King's Regiment 1940/41.

Fred Nightingale in King's Regiment 1940/41.

In July this year (2013) I received an email contact from Paul Kirby. This is what he had to tell me about Fred Nightingale:

There is a well-known photo of the, I think, 17 Chindits flying out of the jungle, with one man in the centre of the picture giving a drink to another, who is sat down. A friend of my family, now sadly deceased, is in that photo: his name was Fred Nightingale of Lancaster and the 13th King's Liverpool's. Fred was a great bloke, a mill worker and keen cricketer who ended up in what the Lancaster Guardian described as the "Burmese Epic". His photo appeared on the front page of the Daily Mail in July 1943 too.

The photo referred to is the first one used to illustrate this story, the transcription alongside the photo in the Daily Mail mentioned by Paul read:

Wingate's Follies, Get Back From Jungle

These grinning, bearded men are back on British territory after three months spent behind the Japanese lines in the Burma jungle. They are members of Brigadier Wingate's famous expedition (Wingate's Follies) which penetrated more than 200 miles into Japanese-occupied land destroying dumps, cutting communications, and collecting valuable information. They lived " on the country " apart from supplies dropped by parachute in the jungle clearings.

Paul contiuned:

Fred brought home a kukri knife, given to him by a Gurkha, which some years ago I donated to the King's Liverpool Regiment Museum. I hope they are looking after it. Fred used it for chopping up wood for the fire. He was an old pal of my Dad's, although my brother and I knew him very well. He was a lovely man.

Thank you for sending over the full passenger list and war diary, very interesting, such a pity I can't show it to Fred. I hope the newspaper cuttings I sent over will be of use to your project? I'm guessing that Fred's wife must have kept all these to show him after he came home.

If I can help with anything else to do with Fred, just let me know.

All the best. Paul.

There is a well-known photo of the, I think, 17 Chindits flying out of the jungle, with one man in the centre of the picture giving a drink to another, who is sat down. A friend of my family, now sadly deceased, is in that photo: his name was Fred Nightingale of Lancaster and the 13th King's Liverpool's. Fred was a great bloke, a mill worker and keen cricketer who ended up in what the Lancaster Guardian described as the "Burmese Epic". His photo appeared on the front page of the Daily Mail in July 1943 too.

The photo referred to is the first one used to illustrate this story, the transcription alongside the photo in the Daily Mail mentioned by Paul read:

Wingate's Follies, Get Back From Jungle

These grinning, bearded men are back on British territory after three months spent behind the Japanese lines in the Burma jungle. They are members of Brigadier Wingate's famous expedition (Wingate's Follies) which penetrated more than 200 miles into Japanese-occupied land destroying dumps, cutting communications, and collecting valuable information. They lived " on the country " apart from supplies dropped by parachute in the jungle clearings.

Paul contiuned:

Fred brought home a kukri knife, given to him by a Gurkha, which some years ago I donated to the King's Liverpool Regiment Museum. I hope they are looking after it. Fred used it for chopping up wood for the fire. He was an old pal of my Dad's, although my brother and I knew him very well. He was a lovely man.

Thank you for sending over the full passenger list and war diary, very interesting, such a pity I can't show it to Fred. I hope the newspaper cuttings I sent over will be of use to your project? I'm guessing that Fred's wife must have kept all these to show him after he came home.

If I can help with anything else to do with Fred, just let me know.

All the best. Paul.

Here is the newspaper article Paul refers to from The Lancaster Observer and Morcambe Chronicle, dated 28th May 1943.

Burmese Epic A Lancaster Cricketer's Part

Lance Corporal Fred Nightingale, a member of a well known Marsh family, came into the news at the week-end, consequent upon the fact that he was one of the party which successfully penetrated behind the Japanese lines in the Burmese jungle, and generally played havoc with their communications.

During the operations Nightingale was removed to hospital in a transport plane, used for bringing up supplies, the pilot of which effected a landing, and also a successful take off, from an open piece of ground hardly half as long as is usually required to take off. He has since cabled to his wife, who, with her five year-old son, resides in Gerrard Street, that he is safe.

Lance Corporal Nightingale, whose mother lives in Willow Lane, was in the service of Messrs. J. Williamson and Son Limited, at Lune Mills, when he joined the Army nearly three years ago. Prior to that time he had been a keen follower of cricket and football, and participated in the former game as a member of the works side, competing in the Lancaster and District League.

He left this country some eighteen months ago, and eventually arrived in India from whence he has written home letters describing his visits to places where his late father, Mr. William Nightingale, served whilst in the London Rifles during the last war.

When interviewed, Mrs. Nightingale said she had received a letter from her husband in which he said it might be some time before he could write again, but he gave her no idea as to why. She, however, said she could well imagine Fred volunteering for the expedition since it would be after his own heart.

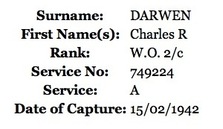

Lance Corporal Nightingale's brother, Charles, who is in the Royal Engineers, has been a prisoner in Italy since February of last year. Another brother, Thomas, who joined the RAF, has been invalided out. His brother-in-law, Battery Sergeant-Major Charles. R. Darwen, of the Royal Artillery, is a prisoner in Japanese hands.

Seen below are some limited details in regard to Fred's brother Charles and his imprisonment in the Italian POW Camp at Gravina in the Province of Bari. Also shown are details for Charles Darwen who was captured by the Japanese at the surrender of Singapore in February 1942. Charles Darwen sadly died whilst working on the infamous Burma 'Death' Railway in August 1943, he is buried in Kanchanaburi War Cemetery in Thailand. Also featured is Fred's place of employment, the James Williamson Lune Mills which manufactured linoleum. The photograph is circa 1932 and can be found amongst others from the general Lancaster area by clicking on the link below:

http://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/asearch?search=lancaster&quicktabs_image=0

Burmese Epic A Lancaster Cricketer's Part

Lance Corporal Fred Nightingale, a member of a well known Marsh family, came into the news at the week-end, consequent upon the fact that he was one of the party which successfully penetrated behind the Japanese lines in the Burmese jungle, and generally played havoc with their communications.

During the operations Nightingale was removed to hospital in a transport plane, used for bringing up supplies, the pilot of which effected a landing, and also a successful take off, from an open piece of ground hardly half as long as is usually required to take off. He has since cabled to his wife, who, with her five year-old son, resides in Gerrard Street, that he is safe.

Lance Corporal Nightingale, whose mother lives in Willow Lane, was in the service of Messrs. J. Williamson and Son Limited, at Lune Mills, when he joined the Army nearly three years ago. Prior to that time he had been a keen follower of cricket and football, and participated in the former game as a member of the works side, competing in the Lancaster and District League.

He left this country some eighteen months ago, and eventually arrived in India from whence he has written home letters describing his visits to places where his late father, Mr. William Nightingale, served whilst in the London Rifles during the last war.

When interviewed, Mrs. Nightingale said she had received a letter from her husband in which he said it might be some time before he could write again, but he gave her no idea as to why. She, however, said she could well imagine Fred volunteering for the expedition since it would be after his own heart.

Lance Corporal Nightingale's brother, Charles, who is in the Royal Engineers, has been a prisoner in Italy since February of last year. Another brother, Thomas, who joined the RAF, has been invalided out. His brother-in-law, Battery Sergeant-Major Charles. R. Darwen, of the Royal Artillery, is a prisoner in Japanese hands.

Seen below are some limited details in regard to Fred's brother Charles and his imprisonment in the Italian POW Camp at Gravina in the Province of Bari. Also shown are details for Charles Darwen who was captured by the Japanese at the surrender of Singapore in February 1942. Charles Darwen sadly died whilst working on the infamous Burma 'Death' Railway in August 1943, he is buried in Kanchanaburi War Cemetery in Thailand. Also featured is Fred's place of employment, the James Williamson Lune Mills which manufactured linoleum. The photograph is circa 1932 and can be found amongst others from the general Lancaster area by clicking on the link below:

http://www.britainfromabove.org.uk/asearch?search=lancaster&quicktabs_image=0

After recovering from his ordeal in 1943, Fred Nightingale left the care of the Imphal Hospital and rejoined the 13th King's at the Napier Barracks in Karachi. Here he remained for the duration of the war performing garrison duties with the battalion and attending training courses when required. The men of the 13th King's began receiving repatriation orders in mid-1945 with the last cohort of men leaving Indian shores in late September.

I would like to thank Paul Kirby for his welcome knowledge and information in regard to Fred Nightingale and his life after returning home from Burma and for sending me the newspaper articles and photographs.

To end this story, here is an image that must have featured in the dreams of at least seventeen former Chindits on many occasions during their lives after the war. Perhaps this image was also a re-occurring feature in the dreams of 159 more.

I would like to thank Paul Kirby for his welcome knowledge and information in regard to Fred Nightingale and his life after returning home from Burma and for sending me the newspaper articles and photographs.

To end this story, here is an image that must have featured in the dreams of at least seventeen former Chindits on many occasions during their lives after the war. Perhaps this image was also a re-occurring feature in the dreams of 159 more.

Fred Nightingale in hospital at Imphal.

Fred Nightingale in hospital at Imphal.

Update 27/04/2017.

From the pages of the Lancaster Guardian dated Friday 28th May 1943, and under the headline, Lancaster Man in Burma Expedition:

A Lancastrian who took part in the famous Burma expedition which caused havoc behind Japanese lines was Lance Corporal Fred Nightingale. Unfortunately, he became ill and was one of those who were daringly recused by plane. He cabled his wife and five year-old son David, who live at Gerrard Street, Marsh, that he is safe. Fred Nightingale attained his 31st birthday last Thursday. Mrs. Nightingale said: "Although Fred wrote to tell me that it would be sometime before he could make contact, I had no idea that he was taking part in such a dangerous adventure. I can imagine him volunteering for such an expedition because he has always been of a sporty and plucky type."

Before joining the Army three years ago, L/Cpl. Nightingale was employed at Lune Mills in Lancaster. He played cricket for the works team and was a keen football follower. Eighteen months ago he was drafted to India and had frequently written home describing his visits to places where his late father, William Nightingale had been whilst serving with the London Rifles during the last war. His mother lives in Willow Lane, Lancaster and a brother, Sapper Charles Nightingale of the Royal Engineers, has been a prisoner of war in Italy since February 1942. Another brother, Thomas, has recently been invalided out of the RAF and brother-in-law, BSM Charles R. Darwen, Royal Artillery, has been a prisoner of war in Japanese hands since the fall of Singapore.

From the pages of the Lancaster Guardian dated Friday 28th May 1943, and under the headline, Lancaster Man in Burma Expedition:

A Lancastrian who took part in the famous Burma expedition which caused havoc behind Japanese lines was Lance Corporal Fred Nightingale. Unfortunately, he became ill and was one of those who were daringly recused by plane. He cabled his wife and five year-old son David, who live at Gerrard Street, Marsh, that he is safe. Fred Nightingale attained his 31st birthday last Thursday. Mrs. Nightingale said: "Although Fred wrote to tell me that it would be sometime before he could make contact, I had no idea that he was taking part in such a dangerous adventure. I can imagine him volunteering for such an expedition because he has always been of a sporty and plucky type."

Before joining the Army three years ago, L/Cpl. Nightingale was employed at Lune Mills in Lancaster. He played cricket for the works team and was a keen football follower. Eighteen months ago he was drafted to India and had frequently written home describing his visits to places where his late father, William Nightingale had been whilst serving with the London Rifles during the last war. His mother lives in Willow Lane, Lancaster and a brother, Sapper Charles Nightingale of the Royal Engineers, has been a prisoner of war in Italy since February 1942. Another brother, Thomas, has recently been invalided out of the RAF and brother-in-law, BSM Charles R. Darwen, Royal Artillery, has been a prisoner of war in Japanese hands since the fall of Singapore.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2013.