Lance Corporal Gerald Desmond

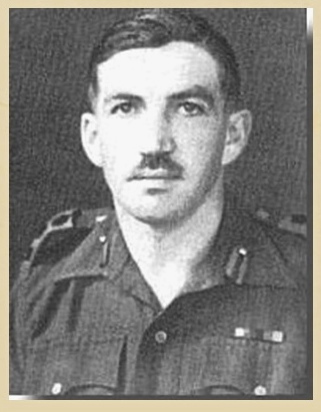

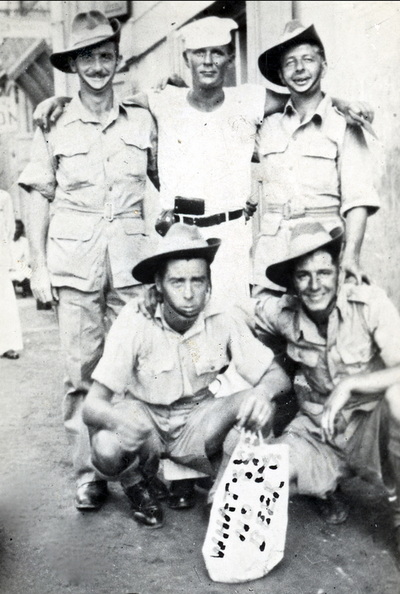

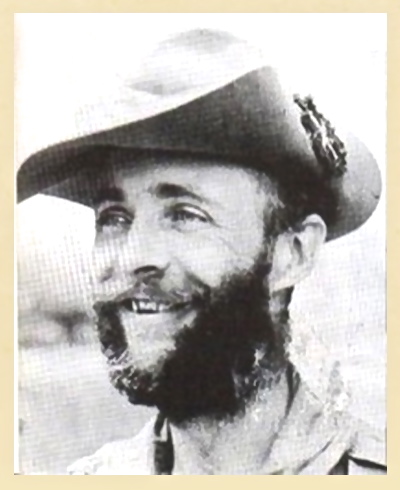

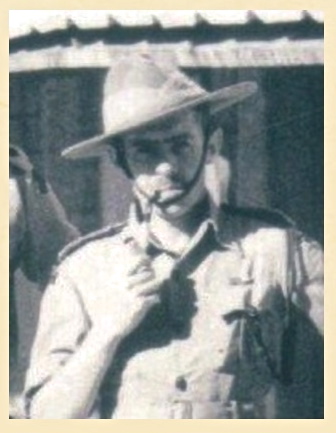

Gerald Desmond in September 1940.

Gerald Desmond in September 1940.

In February 2015, I received an email contact from Liam Brady, the grandson of Lance Corporal Gerald Desmond. Gerald was a commando and served with Bernard Fergusson's 5 Column on Operation Longcloth; he became a prisoner of war in 1943, but thankfully survived his time in Japanese hands and returned home to Ireland in 1945.

Liam told me that:

My knowledge of my Grandfather's time in Burma is all second hand and told to me by my uncles and my mother. He rarely mentioned the war to any of the grandchildren. I will look through what I have in regards to his time during WW2 and forward you anything of interest. If you find any mention of Gerry in your research, no matter how small, please let us know as we are trying to build our own record of his time in the war. On behalf of his family, I would like to thank you for all your effort in putting together such a brilliant website.

Liam and I have exchanged a fair amount of information over the last year, mostly in regards to his grandfather, but also concerning those men he served and fought alongside in Burma. Liam has worked hard in piecing together his granddad's journey and our email conversations have been extremely interesting and rewarding in their content. Following on from these email exchanges, Liam has kindly put together the story of Gerald Desmond and his wartime experiences:

Lance Corporal Gerald Desmond

Gerald Desmond was born in Dublin and grew up in one of the most troubled times in Irish history. A young Gerald was surrounded by the trappings and stories of soldiers. His father John had survived the First World War, but was deeply affected by what he experienced having been at the front from 1914 to the end of the war. Four of his uncles also went to the front during the war; two of them were killed in action. One of his uncles, also named Gerald Desmond was captured on the retreat from Mons in 1914 and spent the rest of the war as a POW in Germany. After the war the Local Government Board awarded Gerald's family one of 250 new houses being built at Killester in Dublin. These houses were built for Irish ex-servicemen of the British Army. So whilst growing up, most everyone around him had in some way been touched by war.

He enlisted in the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers at Belfast on the 3rd September 1940. The story goes, that he was sent up to Belfast to retrieve his younger brother Michael, who left to enlist a day earlier. On hearing the news, his mother Jane had to run to a pawnshop to get the money for Gerald’s train fare. On arriving at the recruitment office he was told Michael had enlisted and was gone and there was nothing he could do. The Recruiting Sergeant did a number on Gerry and talked him into enlisting. He told him he knew his father and had served with him during the first war. Instead of putting him in his brother’s regiment he sent Gerry to his father’s old regiment.

Gerry’s father, John was in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers during WW1 (which was disbanded in the 1920’s), but he had been in the Northumberland Fusiliers for a brief time in 1903. On returning home to Dublin to say his good byes to his family, his father advised Gerry to move to a specialist unit. So Gerald volunteered to the Special Services Unit and was placed in the 5th Special Services Battalion in December 1940. In March 1941 the 5th SSB was split in two and formed No. 5 and No. 6 Commando units. Gerry found himself in No. 6 Commando (he also spent a little time in No. 4 Commando before being sent back to No. 6 Commando) where he specialised in demolition.

On the 24th February 1942 Gerald attended a meeting called by the Commanding Officer of No. 6 Commando, Lt-Col. Featherstonehaugh at their base in Dumbarton, Scotland. The Lt-Col. was looking for volunteers for a secret mission that involved ‘overseas service’. Lieutenant Long and a group made up of 4 Sergeants, 38 Lance Corporals and Privates all put their names forward. Among those who volunteered was Gerald. On the 11th March, Lt. Long and his draft unit left No. 6 Commando for London, with orders to meet in the Hotel Central at Marylebone where they were billeted and given their kit.

At the hotel in London they were joined by volunteers from other Commando Units from all over Britain. This new draft unit was headed up by Lt-Col. Featherstonehaugh who had resigned his position as Commanding Officer of No. 6 Commando in order to lead the new team. This group of about 100 Commandos had all volunteered for 204 British Military Mission, its objective and destination was still unknown to them. They were instructed to depart London on the morning of the 16th March and take the train to Liverpool where HMS Holland was waiting for them. The train journey took most of the day and the group arrived in Liverpool at about 10 o’clock that night where they made their way down to the docks and boarded HMS Holland.

It was only when they had set sail from Liverpool on the 20th March, did they find out they were heading to India as part of Convoy WS17. They had to wait a further four days before they were allowed to open their orders. It was only then that they found out what they had volunteered for. They were part of Military Mission 204, they were being sent into China to help Chiang Kai Shek’s Chinese Army fight against the Japanese by providing military expertise and training. Since Britain still wasn’t officially at war with Japan it was deemed a Top Secret mission and if captured, the men were told they would be on their own. They were to report to the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo in Burma, which was a cover for Mission 204 operations and from there into China.

They reached Bombay in India on the 17th May 1942, on arrival they were known as the Burma Detail and were sent after disembarking to the Deolali Reinforcement Camp for a few days to acclimatise. From there they were moved and stationed at Jubbulpore, where they were attached to the 2nd Battalion of the Green Howards. The Commanding Officer of the mission, Lieutenant Colonel T. Featherstonehaugh left for Army HQ in Meerut for orders.

During their journey to India which took them around Africa via Capetown, the situation in the Far East had changed. The Japanese had invaded and taken Burma. The 204 Military Mission had been scrapped. While at Army HQ, Lt-Col. Featherstonehaugh put the command of his Commandos with Major Cooper- Key. The unit, now left in limbo adopted the letters RZGHA, which had made up their drafting code for their overseas posting. It is at this point that the figure of Orde Wingate stepped into Gerald’s life.

Orde Wingate had been brought to India by General Wavell who had remembered Wingate from his time in the Middle East. Wingate had shown a talent for guerrilla warfare in Palestine and Abyssinia. General Wavell placed Wingate in charge of the 204 Mission in July 1942 soon after his arrival in India. However, with the fall of Burma, Wingate was assigned to forming the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade which would become part of a counter offensive operation against the Japanese.

Wingate, in his search for men, quickly set about trying to secure the commandos from 204 Military Mission for his Brigade which included draft unit RZGHA. By June, Wingate had decided to set up his training camp for the operation in the jungles of Central India. On the 15th June, orders were issued to raise 142 Commando Company which would be attached to the new 77th Brigade. Lieut-Col. Featherstonehaugh was given responsibility for its raising until a new Commanding Officer could be appointed. On the same day, Major Copper-Key was ordered to take an advance party of 30 men from Draft Unit RZGHA, which included Gerald, to form a base at Ramna Camp near Jubbulpore.

The Ramna Camp was located in the jungle area of Central India at a place called Patharia. The RZGHA Draft unit, together with some of those who had survived the original 204 Mission, were formed into the 142 Commando Company. On July 13th, Lt-Colonel Featherstonehaugh was replaced as commanding officer of 142 Commando Company by Major Mike Calvert. Major Calvert had been one of the last British soldiers out of Burma in 1942, having been part of a rear-guard group harassing the Japanese advance; he had also been head of the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo which was the cover for the 204 Mission and its operations. Calvert was the ideal candidate to be CO of the 142 Commando Company; he had experience of the Japanese which dated back to his time based in Shanghai during 1937 and he also had first-hand experience of fighting a guerrilla war in the jungles of Burma.

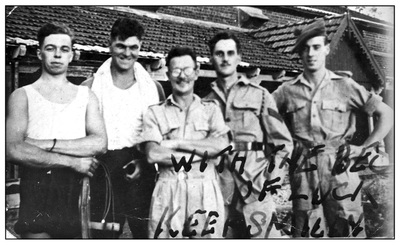

Seen below is the first gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Liam told me that:

My knowledge of my Grandfather's time in Burma is all second hand and told to me by my uncles and my mother. He rarely mentioned the war to any of the grandchildren. I will look through what I have in regards to his time during WW2 and forward you anything of interest. If you find any mention of Gerry in your research, no matter how small, please let us know as we are trying to build our own record of his time in the war. On behalf of his family, I would like to thank you for all your effort in putting together such a brilliant website.

Liam and I have exchanged a fair amount of information over the last year, mostly in regards to his grandfather, but also concerning those men he served and fought alongside in Burma. Liam has worked hard in piecing together his granddad's journey and our email conversations have been extremely interesting and rewarding in their content. Following on from these email exchanges, Liam has kindly put together the story of Gerald Desmond and his wartime experiences:

Lance Corporal Gerald Desmond

Gerald Desmond was born in Dublin and grew up in one of the most troubled times in Irish history. A young Gerald was surrounded by the trappings and stories of soldiers. His father John had survived the First World War, but was deeply affected by what he experienced having been at the front from 1914 to the end of the war. Four of his uncles also went to the front during the war; two of them were killed in action. One of his uncles, also named Gerald Desmond was captured on the retreat from Mons in 1914 and spent the rest of the war as a POW in Germany. After the war the Local Government Board awarded Gerald's family one of 250 new houses being built at Killester in Dublin. These houses were built for Irish ex-servicemen of the British Army. So whilst growing up, most everyone around him had in some way been touched by war.

He enlisted in the Royal Northumberland Fusiliers at Belfast on the 3rd September 1940. The story goes, that he was sent up to Belfast to retrieve his younger brother Michael, who left to enlist a day earlier. On hearing the news, his mother Jane had to run to a pawnshop to get the money for Gerald’s train fare. On arriving at the recruitment office he was told Michael had enlisted and was gone and there was nothing he could do. The Recruiting Sergeant did a number on Gerry and talked him into enlisting. He told him he knew his father and had served with him during the first war. Instead of putting him in his brother’s regiment he sent Gerry to his father’s old regiment.

Gerry’s father, John was in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers during WW1 (which was disbanded in the 1920’s), but he had been in the Northumberland Fusiliers for a brief time in 1903. On returning home to Dublin to say his good byes to his family, his father advised Gerry to move to a specialist unit. So Gerald volunteered to the Special Services Unit and was placed in the 5th Special Services Battalion in December 1940. In March 1941 the 5th SSB was split in two and formed No. 5 and No. 6 Commando units. Gerry found himself in No. 6 Commando (he also spent a little time in No. 4 Commando before being sent back to No. 6 Commando) where he specialised in demolition.

On the 24th February 1942 Gerald attended a meeting called by the Commanding Officer of No. 6 Commando, Lt-Col. Featherstonehaugh at their base in Dumbarton, Scotland. The Lt-Col. was looking for volunteers for a secret mission that involved ‘overseas service’. Lieutenant Long and a group made up of 4 Sergeants, 38 Lance Corporals and Privates all put their names forward. Among those who volunteered was Gerald. On the 11th March, Lt. Long and his draft unit left No. 6 Commando for London, with orders to meet in the Hotel Central at Marylebone where they were billeted and given their kit.

At the hotel in London they were joined by volunteers from other Commando Units from all over Britain. This new draft unit was headed up by Lt-Col. Featherstonehaugh who had resigned his position as Commanding Officer of No. 6 Commando in order to lead the new team. This group of about 100 Commandos had all volunteered for 204 British Military Mission, its objective and destination was still unknown to them. They were instructed to depart London on the morning of the 16th March and take the train to Liverpool where HMS Holland was waiting for them. The train journey took most of the day and the group arrived in Liverpool at about 10 o’clock that night where they made their way down to the docks and boarded HMS Holland.

It was only when they had set sail from Liverpool on the 20th March, did they find out they were heading to India as part of Convoy WS17. They had to wait a further four days before they were allowed to open their orders. It was only then that they found out what they had volunteered for. They were part of Military Mission 204, they were being sent into China to help Chiang Kai Shek’s Chinese Army fight against the Japanese by providing military expertise and training. Since Britain still wasn’t officially at war with Japan it was deemed a Top Secret mission and if captured, the men were told they would be on their own. They were to report to the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo in Burma, which was a cover for Mission 204 operations and from there into China.

They reached Bombay in India on the 17th May 1942, on arrival they were known as the Burma Detail and were sent after disembarking to the Deolali Reinforcement Camp for a few days to acclimatise. From there they were moved and stationed at Jubbulpore, where they were attached to the 2nd Battalion of the Green Howards. The Commanding Officer of the mission, Lieutenant Colonel T. Featherstonehaugh left for Army HQ in Meerut for orders.

During their journey to India which took them around Africa via Capetown, the situation in the Far East had changed. The Japanese had invaded and taken Burma. The 204 Military Mission had been scrapped. While at Army HQ, Lt-Col. Featherstonehaugh put the command of his Commandos with Major Cooper- Key. The unit, now left in limbo adopted the letters RZGHA, which had made up their drafting code for their overseas posting. It is at this point that the figure of Orde Wingate stepped into Gerald’s life.

Orde Wingate had been brought to India by General Wavell who had remembered Wingate from his time in the Middle East. Wingate had shown a talent for guerrilla warfare in Palestine and Abyssinia. General Wavell placed Wingate in charge of the 204 Mission in July 1942 soon after his arrival in India. However, with the fall of Burma, Wingate was assigned to forming the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade which would become part of a counter offensive operation against the Japanese.

Wingate, in his search for men, quickly set about trying to secure the commandos from 204 Military Mission for his Brigade which included draft unit RZGHA. By June, Wingate had decided to set up his training camp for the operation in the jungles of Central India. On the 15th June, orders were issued to raise 142 Commando Company which would be attached to the new 77th Brigade. Lieut-Col. Featherstonehaugh was given responsibility for its raising until a new Commanding Officer could be appointed. On the same day, Major Copper-Key was ordered to take an advance party of 30 men from Draft Unit RZGHA, which included Gerald, to form a base at Ramna Camp near Jubbulpore.

The Ramna Camp was located in the jungle area of Central India at a place called Patharia. The RZGHA Draft unit, together with some of those who had survived the original 204 Mission, were formed into the 142 Commando Company. On July 13th, Lt-Colonel Featherstonehaugh was replaced as commanding officer of 142 Commando Company by Major Mike Calvert. Major Calvert had been one of the last British soldiers out of Burma in 1942, having been part of a rear-guard group harassing the Japanese advance; he had also been head of the Bush Warfare School at Maymyo which was the cover for the 204 Mission and its operations. Calvert was the ideal candidate to be CO of the 142 Commando Company; he had experience of the Japanese which dated back to his time based in Shanghai during 1937 and he also had first-hand experience of fighting a guerrilla war in the jungles of Burma.

Seen below is the first gallery of images in relation to this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Liam continues:

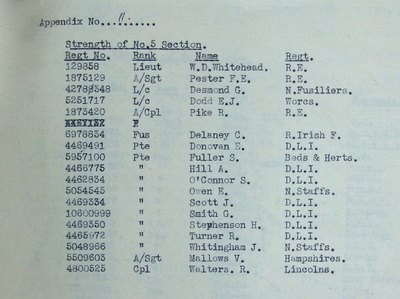

Wingate had 142 Commando Company transferred to the 13th Kings Regiment on the 1st October 1942. Gerald was promoted to Lance Corporal at this time and placed in Major Bernard Fergusson’s 5 Column and was attached to the Commando platoon under Lt. Jim Harman. Wingate knew full well what condition his men and officers had to be in for his operation to succeed. So he trained the men of his new 77th Indian Brigade hard, with the intention of weeding out the weak.

Men died during the training for this operation, the conditions were tough, firstly in baking heat and then in the Monsoon rains. Gerald said they would set up a cross fire with two machine guns, to cover their river crossings against interference from Mugger crocodiles. He also told a story that they were approached by local villagers who claimed there was a man eating tiger in the area and pleaded with them to kill it. Gerald said they built a hide and set out a goat as bait for the tiger. Wingate arrived with a rifle and waited for the tiger, then to their surprise a panther arrived out of the jungle, which Wingate shot. Gerald said it was great and the locals treated them as heroes from then on.

One night on the way back to camp with his column the monsoon rains came, the stream they had crossed earlier in the day quickly started swelling and soon the whole camp was under raging flood waters. Gerald and a number of others found themselves stranded on an island that had been formed by the rising water. He said they had to place sentries throughout the night around the island to shoot a number of wild animals that the flood had washed up amongst them. Three Chindits in the camp were not so lucky and drowned during the flood; many had to spend the night in the trees before being rescued.

Towards the end of November, Wingate granted his men their final leave before heading out to Burma, L/Cpl. Desmond like many of his fellow Chindits headed for Bombay. The Brigade certainly made the most of it, because the Commander of Bombay District sent a telegram to Wingate demanding that no more of his troops were to be sent to Bombay, because of the uproar caused from the bad behaviour of the first draft of men.

Over the course of seven months Wingate had trained and marched the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade across the sub-continent, before finally arriving at the Indian state of Manipur. It started with a 100 mile march to Saugor, then a 160 mile march to Jhansi; all marching was done at night in practice for the operation. They practiced receiving air drops at Dimapur and marched again by night up through the mountains to Imphal. They set up camp outside of Imphal, situated in the mountains that separate India from Burma and waited for the order from General Wavell to push on into enemy held territory.

As Wingate’s men readied themselves for the off, General Wavell’s plans for a counter offensive were coming unstuck due to logistical problems. General Wavell had no option but to cancel the larger offensive. Wingate knew that when General Wavell came to see him, it was likely he might cancel the whole operation. Wingate felt that if his operation didn’t go ahead, it would then be buried and never see the light of day again. After a two hour meeting with General Wavell, Wingate convinced him to let the operation go ahead.

From Major Fergusson book Beyond the Chindwin:

“Offensive or no offensive, for him it was now or never; and there was the further point, that he had brought his Brigade to the boil, and by no stretch of the imagination could it be kept simmering until next cold weather. I know that doubt has been cast on his wisdom in pressing to be allowed to carry on independently, and even an intolerable impertinence, it has always seemed to me, in the wisdom of the commander-in-chief in allowing him to do so. I can only say that every column commander was in agreement; so would have been every officer had they been consulted; and not one of us, even in light of after-events, has ever regretted the decision.”

The Chindits then experienced something quite rare for soldier. As they left Imphal General Wavell, Commander-in-Chief of India and a member of the Governor General’s Executive Council saluted them as they marched by and he waited for each and every man to pass. From this gesture alone, no one was under any illusion about the danger that awaited them.

On February 8th 1943, Wingate set off from Imphal with his Brigade, this included nearly 3000 men, more than a 1000 mules, a few horses and even three elephants. They marched up through the high mountain passes in a scene that must have looked something akin to Hannibal crossing the Alps and down into the Kabaw Valley and the jungles of Burma.

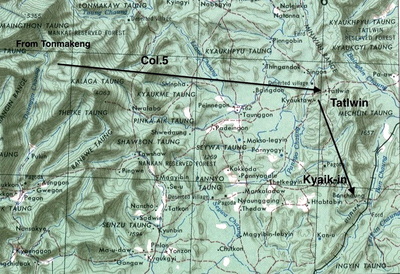

On February 13th, the first part of Wingate’s plan was put in motion; the Brigade split into a Northern Group and a Southern Group. The Southern Group was made up of Columns 1 and 2 and they entered Burma first as a diversion for the main force. They even had someone impersonate Wingate [1] complete with uniform to add to the ruse. During the night of February 14th the Northern Group was able to cross the Chindwin River completely unnoticed, at a place called Tonhe, however, the rain had made conditions very muddy and this had caused a back log. Major Fergusson moved Column 5 who were at the rear of the Brigade further upstream and crossed at Hwematte.

Before heading into Burma, Gerald said they removed all flash insignia denoting regiment or the battalion. Noise was also to be kept to a minimum while in enemy territory. Once across, the column started to push up the Myene Valley, the night marches were miserable in the cold rain. On the 22nd February they had reached Tonmakeng, where they picked up their first air drop, and from there Wingate’s plan was to take a secret jungle track[2] from Tonmakeng to the Zibya Taungdan Escapement.

Wingate’s intelligence proved correct, the track was unknown to the Japanese and it would lead the Chindits right through the Japanese frontline. From there he planned to take the Northern Group through the Mu Valley. The columns had to cover as much ground through the night as possible and all in single file; this became known as the Column Snake. On March 1st they crossed the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment and moved south east towards Namkasa, by late afternoon the whole of Northern Group had reached the assembly area. They bivouacked around the area of Kadaung Chaung.

Wingate told Column's 3 and 5 to separate from the main group and head towards their targets on the Mandalay-Myitkyina railway. On March 2nd they pushed south with all speed with Column 5 leading the way. After reaching Sachan, Column 5 branched off en route for Bonchaung.

By March 6th Column 5 had reached their main objective on the Mandalay–Myitkyina railway at Bonchaung. It had taken them nineteen days to cover the 150 miles from their crossing point on the Chindwin River and Major Fergusson quickly set to work carrying out his orders. The Column 5 Commando Platoon had two targets just south of the train station at Bonchaung. Their job was to blow the main rail bridge and a gorge through which the rail tracks ran. Lt. Jim Harman took half of his Commando Platoon to the gorge and the other half went with Lt. David Whitehead to destroy the bridge.

My additional notes:

[1] Major John Jefferies of the Royal Irish Fusiliers.

[2] This was called Castens Track, after the man (Major Herbert Castens) who had discovered it on the retreat from Burma in 1942.

Wingate had 142 Commando Company transferred to the 13th Kings Regiment on the 1st October 1942. Gerald was promoted to Lance Corporal at this time and placed in Major Bernard Fergusson’s 5 Column and was attached to the Commando platoon under Lt. Jim Harman. Wingate knew full well what condition his men and officers had to be in for his operation to succeed. So he trained the men of his new 77th Indian Brigade hard, with the intention of weeding out the weak.

Men died during the training for this operation, the conditions were tough, firstly in baking heat and then in the Monsoon rains. Gerald said they would set up a cross fire with two machine guns, to cover their river crossings against interference from Mugger crocodiles. He also told a story that they were approached by local villagers who claimed there was a man eating tiger in the area and pleaded with them to kill it. Gerald said they built a hide and set out a goat as bait for the tiger. Wingate arrived with a rifle and waited for the tiger, then to their surprise a panther arrived out of the jungle, which Wingate shot. Gerald said it was great and the locals treated them as heroes from then on.

One night on the way back to camp with his column the monsoon rains came, the stream they had crossed earlier in the day quickly started swelling and soon the whole camp was under raging flood waters. Gerald and a number of others found themselves stranded on an island that had been formed by the rising water. He said they had to place sentries throughout the night around the island to shoot a number of wild animals that the flood had washed up amongst them. Three Chindits in the camp were not so lucky and drowned during the flood; many had to spend the night in the trees before being rescued.

Towards the end of November, Wingate granted his men their final leave before heading out to Burma, L/Cpl. Desmond like many of his fellow Chindits headed for Bombay. The Brigade certainly made the most of it, because the Commander of Bombay District sent a telegram to Wingate demanding that no more of his troops were to be sent to Bombay, because of the uproar caused from the bad behaviour of the first draft of men.

Over the course of seven months Wingate had trained and marched the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade across the sub-continent, before finally arriving at the Indian state of Manipur. It started with a 100 mile march to Saugor, then a 160 mile march to Jhansi; all marching was done at night in practice for the operation. They practiced receiving air drops at Dimapur and marched again by night up through the mountains to Imphal. They set up camp outside of Imphal, situated in the mountains that separate India from Burma and waited for the order from General Wavell to push on into enemy held territory.

As Wingate’s men readied themselves for the off, General Wavell’s plans for a counter offensive were coming unstuck due to logistical problems. General Wavell had no option but to cancel the larger offensive. Wingate knew that when General Wavell came to see him, it was likely he might cancel the whole operation. Wingate felt that if his operation didn’t go ahead, it would then be buried and never see the light of day again. After a two hour meeting with General Wavell, Wingate convinced him to let the operation go ahead.

From Major Fergusson book Beyond the Chindwin:

“Offensive or no offensive, for him it was now or never; and there was the further point, that he had brought his Brigade to the boil, and by no stretch of the imagination could it be kept simmering until next cold weather. I know that doubt has been cast on his wisdom in pressing to be allowed to carry on independently, and even an intolerable impertinence, it has always seemed to me, in the wisdom of the commander-in-chief in allowing him to do so. I can only say that every column commander was in agreement; so would have been every officer had they been consulted; and not one of us, even in light of after-events, has ever regretted the decision.”

The Chindits then experienced something quite rare for soldier. As they left Imphal General Wavell, Commander-in-Chief of India and a member of the Governor General’s Executive Council saluted them as they marched by and he waited for each and every man to pass. From this gesture alone, no one was under any illusion about the danger that awaited them.

On February 8th 1943, Wingate set off from Imphal with his Brigade, this included nearly 3000 men, more than a 1000 mules, a few horses and even three elephants. They marched up through the high mountain passes in a scene that must have looked something akin to Hannibal crossing the Alps and down into the Kabaw Valley and the jungles of Burma.

On February 13th, the first part of Wingate’s plan was put in motion; the Brigade split into a Northern Group and a Southern Group. The Southern Group was made up of Columns 1 and 2 and they entered Burma first as a diversion for the main force. They even had someone impersonate Wingate [1] complete with uniform to add to the ruse. During the night of February 14th the Northern Group was able to cross the Chindwin River completely unnoticed, at a place called Tonhe, however, the rain had made conditions very muddy and this had caused a back log. Major Fergusson moved Column 5 who were at the rear of the Brigade further upstream and crossed at Hwematte.

Before heading into Burma, Gerald said they removed all flash insignia denoting regiment or the battalion. Noise was also to be kept to a minimum while in enemy territory. Once across, the column started to push up the Myene Valley, the night marches were miserable in the cold rain. On the 22nd February they had reached Tonmakeng, where they picked up their first air drop, and from there Wingate’s plan was to take a secret jungle track[2] from Tonmakeng to the Zibya Taungdan Escapement.

Wingate’s intelligence proved correct, the track was unknown to the Japanese and it would lead the Chindits right through the Japanese frontline. From there he planned to take the Northern Group through the Mu Valley. The columns had to cover as much ground through the night as possible and all in single file; this became known as the Column Snake. On March 1st they crossed the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment and moved south east towards Namkasa, by late afternoon the whole of Northern Group had reached the assembly area. They bivouacked around the area of Kadaung Chaung.

Wingate told Column's 3 and 5 to separate from the main group and head towards their targets on the Mandalay-Myitkyina railway. On March 2nd they pushed south with all speed with Column 5 leading the way. After reaching Sachan, Column 5 branched off en route for Bonchaung.

By March 6th Column 5 had reached their main objective on the Mandalay–Myitkyina railway at Bonchaung. It had taken them nineteen days to cover the 150 miles from their crossing point on the Chindwin River and Major Fergusson quickly set to work carrying out his orders. The Column 5 Commando Platoon had two targets just south of the train station at Bonchaung. Their job was to blow the main rail bridge and a gorge through which the rail tracks ran. Lt. Jim Harman took half of his Commando Platoon to the gorge and the other half went with Lt. David Whitehead to destroy the bridge.

My additional notes:

[1] Major John Jefferies of the Royal Irish Fusiliers.

[2] This was called Castens Track, after the man (Major Herbert Castens) who had discovered it on the retreat from Burma in 1942.

Lance Corporal Desmond's story continues:

Lt. Harman and his men were able to bury the tracks by blowing up the cliff face of the gorge. Gerald was with the other half of the Commando Platoon under Lt. David Whitehead; their Job was to blow the bridge that lay at the southern end of the Bonchaung station. The bridge was a steel girder construction that crossed a river bed about fifty feet below, it was made up of three spans supported on piers. While assisting in the demolition of the bridge Gerald removed his boots and left them with the main Column. They wore rope soled shoes when setting the charges because there was a real risk that Army boots would create sparks on the steel girders and accidentally set off the explosives. After finishing the job he caught up with the Column only to find they didn’t have his boots. He had to march on in the rope soled shoes for about ten days, until they received an Air Drop which contained new boots. Gerald told his family that the Japanese would taunt them from the jungle about the Air Drops which missed their targets and landed up in Japanese hands.

The destruction of the bridge and gorge was a total success. The Brigade had completed its main objective, now Wingate in consultation with his Column Commanders gave the order to cross the Irrawaddy River. Wingate hoped to push deeper into Burma with the objective of cutting the Mandalay-Lashio railway and communication network. Column 5 and Column 3 who were ahead of the Brigade where ordered to make for the Gokteik Gorge[3] and blow up the giant viaduct there.

Gerald and the Commandos were put in an advance party to secure the town of Tigyang; Major Ferguson had chosen this as the place the Column would cross the Irrawaddy River. As they moved towards the Irrawaddy, a Japanese aircraft started dropping pamphlets demanding that the British soldiers surrender and calling on the locals to capture them. On March 10th the advance party reached Tigyang after a 35 mile march from Bonchaung; the Commando Platoon quickly set to work securing all the boats they could find down at the river side. Major Fergusson and his men got a friendly reception in Tigyang, whilst in the village he bought as many supplies as he could for the Column and gathered information on the Japanese. The next day Column 5 crossed the Irrawaddy, Jim Harman’s Commando Platoon where sent over first to form a bridgehead at around three in the afternoon.

Gerald said they buried a box of silver rupees on a sandbank there. This cannot be confirmed but it is known that the British buried maps and coins in locations for RAF crew who had been shot down over Burma. These dumps were marked on maps for the air crew. The Chindits carried silver coins to trade with the locals, Wingate knew that these silver coins would carry more store than the paper money the Japanese where issuing to the local villages. Every soldier was given 25 silver rupees to carry on his person in order to buy food from the locals. Also in case of being separated from their columns they could use them to bribe or buy assistance. The whole Column was almost across the river, but as the light faded the Japanese arrived at Tigyang. The Japanese opened up with Mortar fire and light machine guns, but in the darkness the last boats slipped away and made the far bank without any trouble.

While Column 5 was crossing at Tigyang, Column 3 under Major Calvert had also crossed the Irrawaddy at Nyaungbintha. As the Columns pushed deeper into Burma they found a change in the terrain and weather conditions. Baking hot days and cold nights, combined with little food meant the columns became exhausted. Due to missed air drops, Column 5 only received twenty days of full rations during their eighty days behind Japanese lines. They were able to buy some supplies from locals along the way, but never enough to meet their calorific needs. Everybody was experiencing muscle loss from the continuous marching, sometimes up to thirty miles through jungle at night, carrying packs which were over half their body weight. There can be no doubt that this contributed to the heavy losses that Column 5 suffered as the operation went on.

Their uniforms where in poor shape and many of them had lice; also men were in desperate need of new boots. On the 14th March they got a supply drop near Pegon, but only half of what they asked for was delivered and no clothing was included. They had to wait till the 23rd of March before they got their next supply drop, which this time included clothing, but only three days rations. Gerald told his family that foot care was vital; he said the Chindits marched with three pairs of socks; one pair on their feet, one pair in there Slouch hat to keep dry and one pair hanging from their shoulders, drying out after being washed. The further east they marched the more water became an issue, they were in the Burmese dry season and they were forced to dig water holes in the dry river beds, known as chaungs.

Columns 3 and 5 had pushed south east as fast as they could, trying to cover the 140 miles to the Gokteik Gorge. Reports started coming in from scouts that a large build-up of Japanese troops was in forming in front of them at Myitson and Wingate also received word from India Command that they were moving beyond the range of air supply. So Wingate gave the order to Columns 3 and 5 to halt their push east.

By March 20th Column 5 had turned around and had started heading back towards the Irrawaddy River to rendezvous with Wingate. Whilst waiting for the other columns Fergusson took the chance to give his men a much needed rest. Fergusson was worried they had stayed too long in one spot, so he relocated their bivouac location. Gerald and the other Commandos booby-trapped the first camp site before leaving, they placed tempting items around the site to draw the Japanese in. It wasn’t long after they had moved on to their new camp site, that the jungle rang to the sound of explosions. A patrol of about fifty Japanese had found the old bivouac area and while searching through its remains for any information had triggered the explosives.

It was at this point that the Column 5 doctor, Bill Aird was able to assess the condition of the men. What he had to report to Major Ferguson was shocking; the column was in an awful state and some of the men were showing signs of starvation. It is therefore not surprising that when General Command back in India were informed about the state of the Brigade, they sent an order to Wingate on the 24th of March, telling him to return home.

Wingate was told that his Brigade was now beyond the range of the fighter escorts that accompanied the supply planes and unless they turned around they wouldn’t be able to receive fresh supply drops. 5 Column’s next supply drop arrived on the 23rd March, which as mentioned earlier, included clothing, but only three days rations. Major Ferguson was ordered to march north towards the village of Baw for another supply drop and to rendezvous with Wingate and the rest of 77 Brigade. As they approached they could hear mortar fire in the distance and on finally meeting up with the other columns, found only one day’s rations waiting for them.[4]

The Japanese had initially thought that the reports of the British presence in Burma were just scouting parties in search of intelligence and felt they could be mopped up by the local units in the area. At the end of February, General Renya Mutaguchi of the 15th Army was notified that a major force had crossed the Chindwin River. The Japanese had the 18th and 33rd Divisions defending the western part of Burma and these where rushed to the Chindwin River by Mutaguchi, because he mistakenly thought the Chindits were being supplied by land via the Chindwin River.

As Operation Longcloth progressed and the Japanese realised that the Chindits were being supplied by air, the 18th and the 56th Divisions were redirected east with orders to destroy Wingate’s Brigade. The Brigade found itself caught in a trap; it had the Irrawaddy River to the west, the Shweli River to the north and east, plus the Mongmit-Myitson Road to the south, which was heavily patrolled by the Japanese. The Japanese were bringing up more and more reinforcements and closing in from all directions. They also realised that the British would be short on supplies, being so deep into Burma and started to garrison troops in villages and towns knowing that the Chindits would have to visit them eventually to look for food.

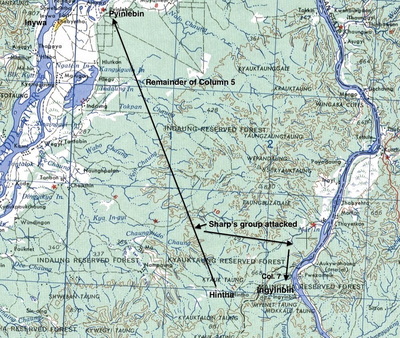

Wingate decided to take his main group back across the Irrawaddy at Inywa, in what he hoped would be a double bluff; he hoped the since he crossed over at Inywa on the out-going journey, the Japanese would never expect him to re-cross at the same place. He ordered Major Fergusson to take Column 5 south of Inywa and act as decoy for the pursuing Japanese.

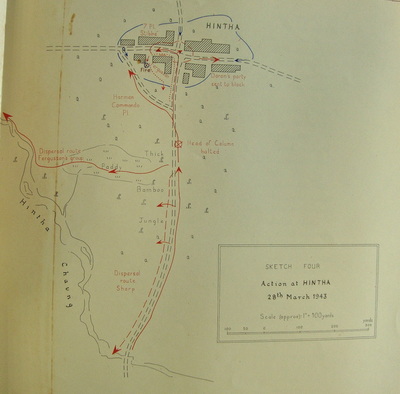

On the night of the 28th March, Column 5 came to the village of Hintha; the village was situated in an area of thick bamboo scrub. They were unable to navigate around the settlement, so reluctantly Major Fergusson decided to enter the village by the main track. He stopped the Column before the village and took a group that consisted of Lt. Philip Stibbe’s 7th Rifle Platoon, Jim Harman’s Commando Platoon and some Burma Rifles. They walked straight into some Japanese troops who were garrisoned in the village.

Fierce fighting ensued at the cross roads in the middle of the village. Major Fergusson sent the commando platoon down a track running around the left side of the village in an effort to encircle the Japanese. Whilst moving down the track they ran into enemy machine gun fire. The Commandos were able to take the Japanese positions on the left side of Hintha at the cost of two men. After about an hour and a half of fighting Major Ferguson and his men were forced to withdraw, as their position was considered too exposed, especially with dawn fast approaching. Gerald’s friend, Stan Fuller[5] and another fellow Commando died in the attack on the left side of the village, along with the Columns Administrative Officer Captain Alex MacDonald. Altogether six men lost their lives in the engagement.

Back down the track, Lt. Sharp, the RAF officer had found a way to circle past the village to the west by taking the main body of the column down a chaung (a dry river bed). The order was given for the Column to disperse and the bugler sounded two bugle calls, everyone slipped off into the jungle to meet at the prearranged rendezvous site a few miles north east of Hintha. Major Fergusson was then able to follow with what was left of his group.

Not long after the unit had regrouped, the rear section of the Column was ambushed by the Japanese. In the confusion about a third of the Column became detached from Major Fergusson and the main group. Gerald was one of those men separated from the main column and his group of about 100 men turned north and started to head towards the Shweli River where they meet Major Gilkes and 7 Column. From Major Fergusson’s book Beyond the Chindwin:

“After starting off from that halt, which was approximately 2 miles from Hintha, we were attacked by a Japanese patrol. This caused a gap in the column, but we kept marching for approximately another 4 miles and then stopped, we waited for these people to catch up, but they must have gone wrong way, because they did not re-join us again. I saw all these men for the last time approximately two and a half miles north east of Hintha. They were all alive, and last seen on 28th March 1943."

Additional notes:

[3] Mike Calvert had been close to destroying the Gokteik viaduct on the retreat from Burma in April 1942.

[4] Lt. David Rowland of 8 Column had been given the task of awaiting 5 Column’s arrival and delivering their food and other supplies.

[5] To view Stan Fuller’s CWGC details, please click on the following link: Pte. Stanley Fuller

Lt. Harman and his men were able to bury the tracks by blowing up the cliff face of the gorge. Gerald was with the other half of the Commando Platoon under Lt. David Whitehead; their Job was to blow the bridge that lay at the southern end of the Bonchaung station. The bridge was a steel girder construction that crossed a river bed about fifty feet below, it was made up of three spans supported on piers. While assisting in the demolition of the bridge Gerald removed his boots and left them with the main Column. They wore rope soled shoes when setting the charges because there was a real risk that Army boots would create sparks on the steel girders and accidentally set off the explosives. After finishing the job he caught up with the Column only to find they didn’t have his boots. He had to march on in the rope soled shoes for about ten days, until they received an Air Drop which contained new boots. Gerald told his family that the Japanese would taunt them from the jungle about the Air Drops which missed their targets and landed up in Japanese hands.

The destruction of the bridge and gorge was a total success. The Brigade had completed its main objective, now Wingate in consultation with his Column Commanders gave the order to cross the Irrawaddy River. Wingate hoped to push deeper into Burma with the objective of cutting the Mandalay-Lashio railway and communication network. Column 5 and Column 3 who were ahead of the Brigade where ordered to make for the Gokteik Gorge[3] and blow up the giant viaduct there.

Gerald and the Commandos were put in an advance party to secure the town of Tigyang; Major Ferguson had chosen this as the place the Column would cross the Irrawaddy River. As they moved towards the Irrawaddy, a Japanese aircraft started dropping pamphlets demanding that the British soldiers surrender and calling on the locals to capture them. On March 10th the advance party reached Tigyang after a 35 mile march from Bonchaung; the Commando Platoon quickly set to work securing all the boats they could find down at the river side. Major Fergusson and his men got a friendly reception in Tigyang, whilst in the village he bought as many supplies as he could for the Column and gathered information on the Japanese. The next day Column 5 crossed the Irrawaddy, Jim Harman’s Commando Platoon where sent over first to form a bridgehead at around three in the afternoon.

Gerald said they buried a box of silver rupees on a sandbank there. This cannot be confirmed but it is known that the British buried maps and coins in locations for RAF crew who had been shot down over Burma. These dumps were marked on maps for the air crew. The Chindits carried silver coins to trade with the locals, Wingate knew that these silver coins would carry more store than the paper money the Japanese where issuing to the local villages. Every soldier was given 25 silver rupees to carry on his person in order to buy food from the locals. Also in case of being separated from their columns they could use them to bribe or buy assistance. The whole Column was almost across the river, but as the light faded the Japanese arrived at Tigyang. The Japanese opened up with Mortar fire and light machine guns, but in the darkness the last boats slipped away and made the far bank without any trouble.

While Column 5 was crossing at Tigyang, Column 3 under Major Calvert had also crossed the Irrawaddy at Nyaungbintha. As the Columns pushed deeper into Burma they found a change in the terrain and weather conditions. Baking hot days and cold nights, combined with little food meant the columns became exhausted. Due to missed air drops, Column 5 only received twenty days of full rations during their eighty days behind Japanese lines. They were able to buy some supplies from locals along the way, but never enough to meet their calorific needs. Everybody was experiencing muscle loss from the continuous marching, sometimes up to thirty miles through jungle at night, carrying packs which were over half their body weight. There can be no doubt that this contributed to the heavy losses that Column 5 suffered as the operation went on.

Their uniforms where in poor shape and many of them had lice; also men were in desperate need of new boots. On the 14th March they got a supply drop near Pegon, but only half of what they asked for was delivered and no clothing was included. They had to wait till the 23rd of March before they got their next supply drop, which this time included clothing, but only three days rations. Gerald told his family that foot care was vital; he said the Chindits marched with three pairs of socks; one pair on their feet, one pair in there Slouch hat to keep dry and one pair hanging from their shoulders, drying out after being washed. The further east they marched the more water became an issue, they were in the Burmese dry season and they were forced to dig water holes in the dry river beds, known as chaungs.

Columns 3 and 5 had pushed south east as fast as they could, trying to cover the 140 miles to the Gokteik Gorge. Reports started coming in from scouts that a large build-up of Japanese troops was in forming in front of them at Myitson and Wingate also received word from India Command that they were moving beyond the range of air supply. So Wingate gave the order to Columns 3 and 5 to halt their push east.

By March 20th Column 5 had turned around and had started heading back towards the Irrawaddy River to rendezvous with Wingate. Whilst waiting for the other columns Fergusson took the chance to give his men a much needed rest. Fergusson was worried they had stayed too long in one spot, so he relocated their bivouac location. Gerald and the other Commandos booby-trapped the first camp site before leaving, they placed tempting items around the site to draw the Japanese in. It wasn’t long after they had moved on to their new camp site, that the jungle rang to the sound of explosions. A patrol of about fifty Japanese had found the old bivouac area and while searching through its remains for any information had triggered the explosives.

It was at this point that the Column 5 doctor, Bill Aird was able to assess the condition of the men. What he had to report to Major Ferguson was shocking; the column was in an awful state and some of the men were showing signs of starvation. It is therefore not surprising that when General Command back in India were informed about the state of the Brigade, they sent an order to Wingate on the 24th of March, telling him to return home.

Wingate was told that his Brigade was now beyond the range of the fighter escorts that accompanied the supply planes and unless they turned around they wouldn’t be able to receive fresh supply drops. 5 Column’s next supply drop arrived on the 23rd March, which as mentioned earlier, included clothing, but only three days rations. Major Ferguson was ordered to march north towards the village of Baw for another supply drop and to rendezvous with Wingate and the rest of 77 Brigade. As they approached they could hear mortar fire in the distance and on finally meeting up with the other columns, found only one day’s rations waiting for them.[4]

The Japanese had initially thought that the reports of the British presence in Burma were just scouting parties in search of intelligence and felt they could be mopped up by the local units in the area. At the end of February, General Renya Mutaguchi of the 15th Army was notified that a major force had crossed the Chindwin River. The Japanese had the 18th and 33rd Divisions defending the western part of Burma and these where rushed to the Chindwin River by Mutaguchi, because he mistakenly thought the Chindits were being supplied by land via the Chindwin River.

As Operation Longcloth progressed and the Japanese realised that the Chindits were being supplied by air, the 18th and the 56th Divisions were redirected east with orders to destroy Wingate’s Brigade. The Brigade found itself caught in a trap; it had the Irrawaddy River to the west, the Shweli River to the north and east, plus the Mongmit-Myitson Road to the south, which was heavily patrolled by the Japanese. The Japanese were bringing up more and more reinforcements and closing in from all directions. They also realised that the British would be short on supplies, being so deep into Burma and started to garrison troops in villages and towns knowing that the Chindits would have to visit them eventually to look for food.

Wingate decided to take his main group back across the Irrawaddy at Inywa, in what he hoped would be a double bluff; he hoped the since he crossed over at Inywa on the out-going journey, the Japanese would never expect him to re-cross at the same place. He ordered Major Fergusson to take Column 5 south of Inywa and act as decoy for the pursuing Japanese.

On the night of the 28th March, Column 5 came to the village of Hintha; the village was situated in an area of thick bamboo scrub. They were unable to navigate around the settlement, so reluctantly Major Fergusson decided to enter the village by the main track. He stopped the Column before the village and took a group that consisted of Lt. Philip Stibbe’s 7th Rifle Platoon, Jim Harman’s Commando Platoon and some Burma Rifles. They walked straight into some Japanese troops who were garrisoned in the village.

Fierce fighting ensued at the cross roads in the middle of the village. Major Fergusson sent the commando platoon down a track running around the left side of the village in an effort to encircle the Japanese. Whilst moving down the track they ran into enemy machine gun fire. The Commandos were able to take the Japanese positions on the left side of Hintha at the cost of two men. After about an hour and a half of fighting Major Ferguson and his men were forced to withdraw, as their position was considered too exposed, especially with dawn fast approaching. Gerald’s friend, Stan Fuller[5] and another fellow Commando died in the attack on the left side of the village, along with the Columns Administrative Officer Captain Alex MacDonald. Altogether six men lost their lives in the engagement.

Back down the track, Lt. Sharp, the RAF officer had found a way to circle past the village to the west by taking the main body of the column down a chaung (a dry river bed). The order was given for the Column to disperse and the bugler sounded two bugle calls, everyone slipped off into the jungle to meet at the prearranged rendezvous site a few miles north east of Hintha. Major Fergusson was then able to follow with what was left of his group.

Not long after the unit had regrouped, the rear section of the Column was ambushed by the Japanese. In the confusion about a third of the Column became detached from Major Fergusson and the main group. Gerald was one of those men separated from the main column and his group of about 100 men turned north and started to head towards the Shweli River where they meet Major Gilkes and 7 Column. From Major Fergusson’s book Beyond the Chindwin:

“After starting off from that halt, which was approximately 2 miles from Hintha, we were attacked by a Japanese patrol. This caused a gap in the column, but we kept marching for approximately another 4 miles and then stopped, we waited for these people to catch up, but they must have gone wrong way, because they did not re-join us again. I saw all these men for the last time approximately two and a half miles north east of Hintha. They were all alive, and last seen on 28th March 1943."

Additional notes:

[3] Mike Calvert had been close to destroying the Gokteik viaduct on the retreat from Burma in April 1942.

[4] Lt. David Rowland of 8 Column had been given the task of awaiting 5 Column’s arrival and delivering their food and other supplies.

[5] To view Stan Fuller’s CWGC details, please click on the following link: Pte. Stanley Fuller

Liam continues with his account:

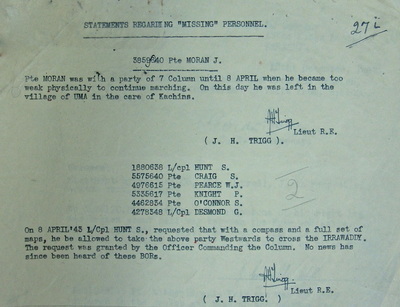

Wingate’s attempt to cross the Irrawaddy with his main force at Inywa was beaten back by the Japanese. After this failed crossing, Major Gilkes moved back towards the Shweli River and this is when he met up with the men from 5 Column and absorbed them into his own unit. Major Gilkes was shocked at the condition of these men and did his best to issue them with extra rations.

On the 1st April, 7 Column turned east to cross the Shweli River independently. Major Gilkes had decided the best way out of Burma was to march east for Yunnan Province and from there trek north towards Allied held territory. On the 3rd April, 7 Column tried to cross the Shweli River at Ingyinbin. The Shweli was a fast flowing river with strong currents, its banks where high and covered in thick jungle and it proved to be a nightmare for all those who tried to cross.

The column moved out on to a sandbank after dark and tried to cross about 120 yards of river, one of their two boats was swept away and by 01.00 hours, Major Gilkes had cancelled the crossing. About forty-five men had made it across the river, including Lt. Astell, Lt. Smyly and F/Lt. Hammond, they were ordered to proceed eastwards under their own steam. Major Gilkes had no choice but to move the rest of the Column southwards along the Shweli banks in the hope of finding another crossing point. By now Wingate had ordered that everyone should divide into dispersal groups of around forty men each and make their way home by whatever means, however, Major Gilkes choose to keep his Column intact.

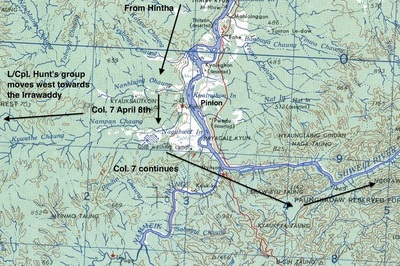

Five days later, 7 Column still hadn’t found anywhere suitable to cross the Shweli. The condition of many of the men was desperate, especially those who had joined from Column 5. On the 8th April near Pinlon in the Nahnlaing Chaung, L/Cpl. Hunt made a request to the commanding officer, that he and five other men, which included L/Cpl. Desmond, be allowed leave 7 Column and try make their own way back to India by heading west, the way they had first come.

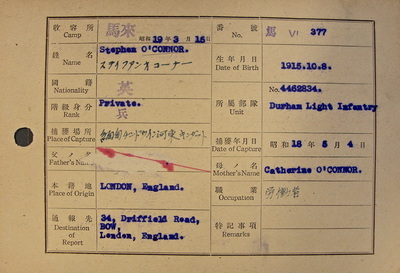

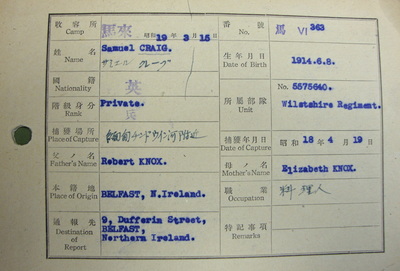

The group included, L/Cpl. Desmond, L/Cpl. Sidney Hunt (Bradford), Pte. Samuel Craig (Belfast), Pte. William Pearce (Dagenham), William John Pearce (who had also been part of the draft unit RZGHA with Gerald), Pte. Peter Knight and Pte. Stephen O’Connor (both from London). The family story goes that five of them were wounded and only Gerald was fit enough to hold a rifle. They were faced at that time with either a nine week march home through China, or a four week march back through Burma; in their condition they had no choice.

All six of them where from 142 Commando Company, it is possible to say they all knew each other. Pte. Stephen O’Connor was part of the Commando Platoon from 5 Column along with Gerald, who told his family later, that he had elected to stay with his friend. They were given maps, a compass, a tin of biscuits, a half blanket for each man and one rifle (.303 short magazine Lee Enfield) between them. On the night of the 8th April, they turned west and headed towards the Irrawaddy River. The Japanese had by now secured the western bank of the Irrawaddy and removed all the boats from the eastern bank in an effort to stop any Chindits crossing the mile wide river.

On reaching the Irrawaddy River, they waited till dark before making their crossing. Gerald told his son that they made a makeshift raft and put the wounded on it while the others swam behind to bring the raft across. He said they swam till they were exhausted then let the currents of the river drag them part of the way, then swam a bit more and then used the currents again. They got to the opposite bank, but had finished up much further downstream from their original starting point than they had hoped. He said the Japanese where patrolling the river bank using search lights on the river.

Now that they had made it across the Irrawaddy, the next major geographical obstacle in their way was the Mu River. On the 13th April they crossed the Myitkyina-Mandalay railway around the area of Kanbalu and entered the Mu River Valley. The following day on the 14th April, L/Cpl. Desmond according to the family story, left the others hidden while he scouted the trail ahead. He came across some Buddhist Monks and while trying to gather information about the Japanese in the surrounding area, he didn’t notice one the Monks slip off into the jungle. The Monk notified the Japanese in a nearby village and Gerald was quickly captured.

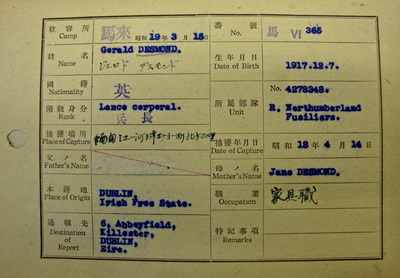

His POW index card records his place of capture as: seventy miles north of Ye-u on the banks of the Mu River. As a group they had covered more than 110 miles in six days and considering their physical condition, and the fact they had crossed one of the great rivers of Asia, one can only marvel at the mental strength shown by these men.

At the time of his capture, Gerald was carrying explosives in some condoms to keep them dry. At the arrival of the Japanese, all that flashed through his mind was how to dispose of the explosives without his captors noticing. He was able to do this before reaching the village. The Japanese interrogated him, looking for information on Operation Longcloth; a map of central Burma was placed in front of him and he was ordered to show where he had been over the previous weeks. Apparently he started pointing everywhere on the map, which earned him a beating. They also interrogated him for information about a British Officer (possibly Major Seagrim)[6] who was fighting a guerrilla war along with the help of the Karen tribes of Northern Burma.

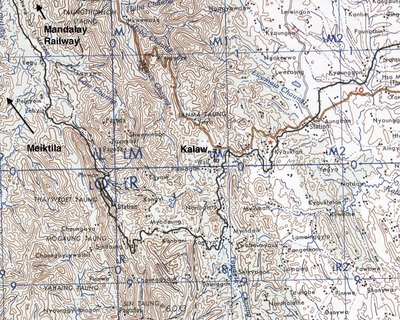

Tied and bound L/Cpl. Desmond was marched back through the jungle by his Japanese captors, but this time in a southerly direction. Over the course of the next eighteen days he was joined by other Chindits who had also been captured. They passed through the village of Ye- U and then back across the Irrawaddy River, finally arriving at Kalaw on the 2nd May.

Additional notes:

[6] This was Major Hugh Paul Seagrim GC, DSO, MBE. Seagrim led the Karens in a campaign of sabotage against the Japanese occupation. His force enjoyed much support from Karen civilians despite a series of brutal Japanese reprisal killings against Karen villages. His force was gradually wiped out by a concentrated Japanese manhunt. To prevent further bloodshed Seagrim surrendered himself to the Japanese forces on 15th March 1944. He and eight of his Karen companions were executed by the Japanese on 22nd September in Rangoon.

Wingate’s attempt to cross the Irrawaddy with his main force at Inywa was beaten back by the Japanese. After this failed crossing, Major Gilkes moved back towards the Shweli River and this is when he met up with the men from 5 Column and absorbed them into his own unit. Major Gilkes was shocked at the condition of these men and did his best to issue them with extra rations.

On the 1st April, 7 Column turned east to cross the Shweli River independently. Major Gilkes had decided the best way out of Burma was to march east for Yunnan Province and from there trek north towards Allied held territory. On the 3rd April, 7 Column tried to cross the Shweli River at Ingyinbin. The Shweli was a fast flowing river with strong currents, its banks where high and covered in thick jungle and it proved to be a nightmare for all those who tried to cross.

The column moved out on to a sandbank after dark and tried to cross about 120 yards of river, one of their two boats was swept away and by 01.00 hours, Major Gilkes had cancelled the crossing. About forty-five men had made it across the river, including Lt. Astell, Lt. Smyly and F/Lt. Hammond, they were ordered to proceed eastwards under their own steam. Major Gilkes had no choice but to move the rest of the Column southwards along the Shweli banks in the hope of finding another crossing point. By now Wingate had ordered that everyone should divide into dispersal groups of around forty men each and make their way home by whatever means, however, Major Gilkes choose to keep his Column intact.

Five days later, 7 Column still hadn’t found anywhere suitable to cross the Shweli. The condition of many of the men was desperate, especially those who had joined from Column 5. On the 8th April near Pinlon in the Nahnlaing Chaung, L/Cpl. Hunt made a request to the commanding officer, that he and five other men, which included L/Cpl. Desmond, be allowed leave 7 Column and try make their own way back to India by heading west, the way they had first come.

The group included, L/Cpl. Desmond, L/Cpl. Sidney Hunt (Bradford), Pte. Samuel Craig (Belfast), Pte. William Pearce (Dagenham), William John Pearce (who had also been part of the draft unit RZGHA with Gerald), Pte. Peter Knight and Pte. Stephen O’Connor (both from London). The family story goes that five of them were wounded and only Gerald was fit enough to hold a rifle. They were faced at that time with either a nine week march home through China, or a four week march back through Burma; in their condition they had no choice.

All six of them where from 142 Commando Company, it is possible to say they all knew each other. Pte. Stephen O’Connor was part of the Commando Platoon from 5 Column along with Gerald, who told his family later, that he had elected to stay with his friend. They were given maps, a compass, a tin of biscuits, a half blanket for each man and one rifle (.303 short magazine Lee Enfield) between them. On the night of the 8th April, they turned west and headed towards the Irrawaddy River. The Japanese had by now secured the western bank of the Irrawaddy and removed all the boats from the eastern bank in an effort to stop any Chindits crossing the mile wide river.

On reaching the Irrawaddy River, they waited till dark before making their crossing. Gerald told his son that they made a makeshift raft and put the wounded on it while the others swam behind to bring the raft across. He said they swam till they were exhausted then let the currents of the river drag them part of the way, then swam a bit more and then used the currents again. They got to the opposite bank, but had finished up much further downstream from their original starting point than they had hoped. He said the Japanese where patrolling the river bank using search lights on the river.

Now that they had made it across the Irrawaddy, the next major geographical obstacle in their way was the Mu River. On the 13th April they crossed the Myitkyina-Mandalay railway around the area of Kanbalu and entered the Mu River Valley. The following day on the 14th April, L/Cpl. Desmond according to the family story, left the others hidden while he scouted the trail ahead. He came across some Buddhist Monks and while trying to gather information about the Japanese in the surrounding area, he didn’t notice one the Monks slip off into the jungle. The Monk notified the Japanese in a nearby village and Gerald was quickly captured.

His POW index card records his place of capture as: seventy miles north of Ye-u on the banks of the Mu River. As a group they had covered more than 110 miles in six days and considering their physical condition, and the fact they had crossed one of the great rivers of Asia, one can only marvel at the mental strength shown by these men.

At the time of his capture, Gerald was carrying explosives in some condoms to keep them dry. At the arrival of the Japanese, all that flashed through his mind was how to dispose of the explosives without his captors noticing. He was able to do this before reaching the village. The Japanese interrogated him, looking for information on Operation Longcloth; a map of central Burma was placed in front of him and he was ordered to show where he had been over the previous weeks. Apparently he started pointing everywhere on the map, which earned him a beating. They also interrogated him for information about a British Officer (possibly Major Seagrim)[6] who was fighting a guerrilla war along with the help of the Karen tribes of Northern Burma.

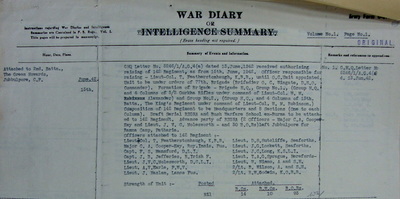

Tied and bound L/Cpl. Desmond was marched back through the jungle by his Japanese captors, but this time in a southerly direction. Over the course of the next eighteen days he was joined by other Chindits who had also been captured. They passed through the village of Ye- U and then back across the Irrawaddy River, finally arriving at Kalaw on the 2nd May.

Additional notes:

[6] This was Major Hugh Paul Seagrim GC, DSO, MBE. Seagrim led the Karens in a campaign of sabotage against the Japanese occupation. His force enjoyed much support from Karen civilians despite a series of brutal Japanese reprisal killings against Karen villages. His force was gradually wiped out by a concentrated Japanese manhunt. To prevent further bloodshed Seagrim surrendered himself to the Japanese forces on 15th March 1944. He and eight of his Karen companions were executed by the Japanese on 22nd September in Rangoon.

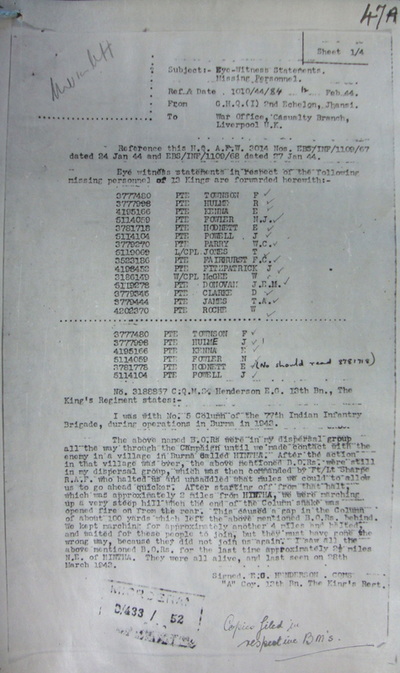

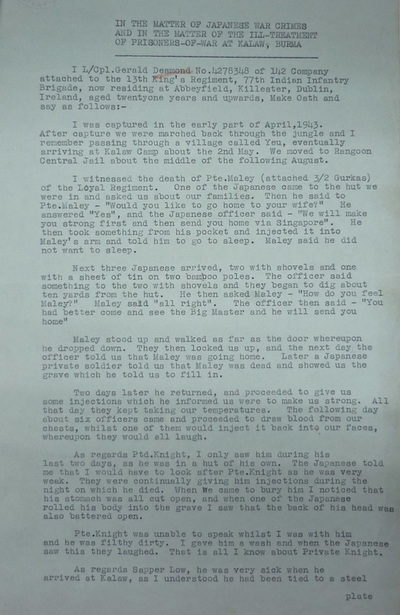

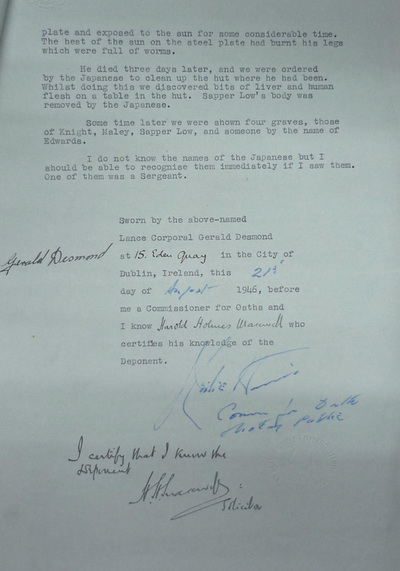

While in Kalaw Gerald witnessed the Japanese conduct horrendous atrocities upon POW’s. This involved medical experiments on him and his fellow prisoners. The Japanese administered injections to all the prisoners during their time in Kalaw; these injections were most likely different strains of malaria and dengue fever which they were testing. Gerald told his son, that they would stab him in the chest with the needle when giving the injection and when taking blood samples they would squirt some blood in his face from the syringe, which the Japanese found very amusing. After the war Gerald gave a witness statement about these events at Kalaw.

Here is a part transcription of his testimony to the War Office.

“As regards Pte. Knight, I only saw him during his last two days, as he was in a hut of his own. The Japanese told me I would have to look after Pte. Knight as he was very weak. They were continually giving him injections during the night on which he died. When we came to bury him I noticed that his stomach was all cut open, and when one of the Japanese rolled his body into the grave I saw that the back of his head was also battered open.”

“As regards Sapper Low, he was very sick when he arrived at Kalaw, as I understand he had been tied to a steel plate and exposed to the sun for some considerable time. The heat from the sun on the steel plate had burnt his legs which were full of worms.

He died three days later, and we were ordered by the Japanese to clean up the hut where he had been. Whilst doing this we discovered bits of liver and human flesh on a table in the hut. Sapper Low’s body was removed by the Japanese.”

Shown below is Lance Corporal Gerald Desmond's full testimony document. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Here is a part transcription of his testimony to the War Office.

“As regards Pte. Knight, I only saw him during his last two days, as he was in a hut of his own. The Japanese told me I would have to look after Pte. Knight as he was very weak. They were continually giving him injections during the night on which he died. When we came to bury him I noticed that his stomach was all cut open, and when one of the Japanese rolled his body into the grave I saw that the back of his head was also battered open.”

“As regards Sapper Low, he was very sick when he arrived at Kalaw, as I understand he had been tied to a steel plate and exposed to the sun for some considerable time. The heat from the sun on the steel plate had burnt his legs which were full of worms.

He died three days later, and we were ordered by the Japanese to clean up the hut where he had been. Whilst doing this we discovered bits of liver and human flesh on a table in the hut. Sapper Low’s body was removed by the Japanese.”

Shown below is Lance Corporal Gerald Desmond's full testimony document. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

In terms of the men travelling with his grandfather after 8th April 1943, Liam discovered the following:

Regarding the other men, who along with L/Cpl. Desmond had left Column 7 and tried to make their way back to India, all of them were captured by the Japanese over the following days and weeks.

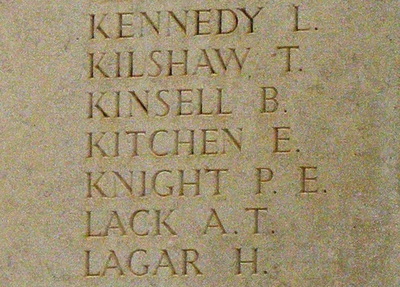

As mentioned above, Pte. Peter ‘Rocky’ Knight, who Gerald had left in hiding on the day he was captured, died at Kalaw aged 25. Gerald always said he looked after him as best he could during his last few days.

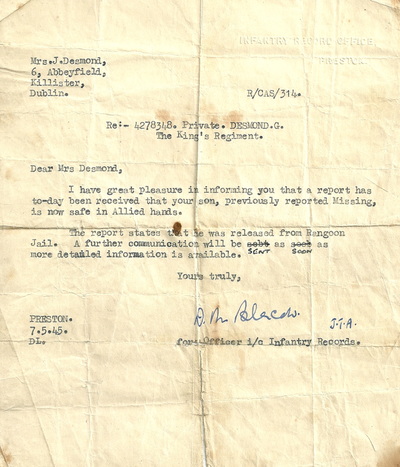

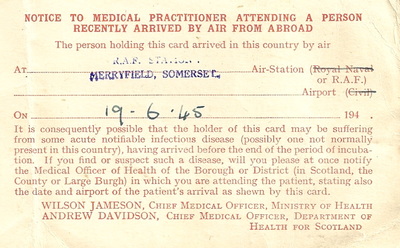

L/Cpl. Sidney Hunt was captured and also taken to Kalaw and eventually died on the 2nd September 1943 whilst in Rangoon Jail, he was just 22 years old. William Pearce also died in Rangoon Jail on the 17th September 1944, he was 25 years old. Samuel Craig made it all the way to the Chindwin River before being captured on the 19th April, some four days after Gerald fell into Japanese hands. Stephen O’Connor and William Pearce were captured together at the town of Kindat, east of the Chindwin River on the 4th May, nearly a month after they had left Column 7.

Of these men, only O’Connor, Desmond and Craig survived their time as prisoners in Rangoon Jail. The Longcloth Chindit survival rate for prisoners of war makes for shocking reading. Of the 213 non-officer ranked men captured by the Japanese, 141 died in Rangoon Jail. Of the 33 officers captured, six perished inside the jail. Column 5 had the worst record of all when it came to having men captured by the Japanese, with 85 soldiers falling into enemy hands during 1943.

By mid-August 1943, Gerald and those Chindits still alive where moved from Kalaw to Rangoon Central Jail, where they were placed into solitary confinement. Gerald’s cell was about 8 feet square, there was no bed in the room and the only items the Japanese provided were a blanket, a mess tin and an ammunition box to be used as a latrine. Anybody caught talking in their cell received a beating from the guards and the only other POW you could see was the man in the cell opposite you.

Over the following weeks, Gerald was taken out for interrogation by the Kempeitai, the Japanese secret police. It was during one of these interrogations that L/Cpl. Desmond had a strange conversation with a Japanese officer; the officer asked him what an Irishman was doing fighting for the British. Gerald said nothing in reply. Then the officer asked him if he wouldn’t prefer to be in Mooney’s (a pub chain in Dublin) with a pint of Guinness.

Gerald said his knees started to shake under the table at the mention of the Dublin Pub, but he answered the officer by asking if he was referring to Mooney’s on Parnell Street, the officer picked up his sword and beat Gerald around the room with the side of his blade. The Japanese officer then told Gerald that it was the Mooney’s Pub on College Green that he was talking about. He claimed to have been a student at Trinity College in Dublin and knew the city well. A recent search for a Japanese Student in Trinity College during the 1920’s and 30’s in the records of Alumni returned no information.

Gerald was released from solitary confinement and placed in Block 6 of the jail, his POW number was 365. The only thing he possessed was the uniform he arrived in which was rotten and falling to pieces. All orders and commands given to the POW’s by their captors were spoken in Japanese; failure to understand resulted in a beating. Failure to bow to a Japanese soldier resulted in a beating even if you were unaware of his presence. Every morning there was a Roll Call or ‘Tenko’, again it was all done in Japanese and the men present had to call out their numbers in Japanese. Nearly all the men who arrived at Rangoon from Operation Longcloth where in a terrible state, suffering from wounds, disease, dysentery and jungle sores. Block 6 had no doctor or medical staff. One of the Chindit officers, Lt. Allen Wilding[7] described it as follows:

There were no beds or sick room equipment of any kind, not even bedpans. There was an empty lime drum which dysentery patients could use if they had the strength and resolve; otherwise, to wash a dysentery patient’s blanket when you have no tub, no soap or hot water, just cold water and a bit of concrete to bash it on, is rather unpleasant.

Men were dying at a rate of at least one a day in Block 6, until Major Raymond Ramsay, the Brigades Medical Officer was released from solitary confinement. Only about 30% of the Chindits captured in 1943 survived there time as prisoners of war. Gerald was one of the few Other Ranks from the Chindits to survive Rangoon Jail. It was noticable, that the further these soldiers got from the front line, the worse their treatment became. In Rangoon the prisoners experienced torture, slave labour, malnutrition, plus diseases such as cholera, beri beri and malaria, it was a daily test of their will just to survive. Gerald was to suffer from the effects of having beri beri, dengue fever and malaria for the rest of his life.

Additional notes:

[7] Lt. Richard Allen Wilding, Cipher Officer to Wingate’s Brigade HQ.

Seen below are some photographs, maps and other documents in relation to the group of men led by L/Cpl. Hunt, who decided to leave the relative safety of Gilkes' Column on the 8th April 1943, in an attempt to reach India via the Chindwin River. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Regarding the other men, who along with L/Cpl. Desmond had left Column 7 and tried to make their way back to India, all of them were captured by the Japanese over the following days and weeks.

As mentioned above, Pte. Peter ‘Rocky’ Knight, who Gerald had left in hiding on the day he was captured, died at Kalaw aged 25. Gerald always said he looked after him as best he could during his last few days.

L/Cpl. Sidney Hunt was captured and also taken to Kalaw and eventually died on the 2nd September 1943 whilst in Rangoon Jail, he was just 22 years old. William Pearce also died in Rangoon Jail on the 17th September 1944, he was 25 years old. Samuel Craig made it all the way to the Chindwin River before being captured on the 19th April, some four days after Gerald fell into Japanese hands. Stephen O’Connor and William Pearce were captured together at the town of Kindat, east of the Chindwin River on the 4th May, nearly a month after they had left Column 7.

Of these men, only O’Connor, Desmond and Craig survived their time as prisoners in Rangoon Jail. The Longcloth Chindit survival rate for prisoners of war makes for shocking reading. Of the 213 non-officer ranked men captured by the Japanese, 141 died in Rangoon Jail. Of the 33 officers captured, six perished inside the jail. Column 5 had the worst record of all when it came to having men captured by the Japanese, with 85 soldiers falling into enemy hands during 1943.