Captain Leslie Randle Cottrell

Lieutenant Leslie Cottrell, Colchester 1941.

Lieutenant Leslie Cottrell, Colchester 1941.

Leslie Randle Cottrell was born on 1st October 1919 in the West Derby suburb of Liverpool on Merseyside. So it can be of no surprise that he was to join his local Army Regiment in order to do 'his duty' for King and country during WW2. The young officer had excelled at school and was actually studying at Liverpool University when war broke out. Leslie had begun his University life in October 1938 and was studying for his degree in the Arts.

He had been part of the University Officer Training Corps which had been affiliated to the King's Regiment for many years, using the Regimental Seaforth Barracks as it's training base. Leslie was commissioned into the 13th Battalion in 1940 aged 21 and would eventually travel with them to India in late 1941.

NB. Shortly before his commission, Leslie had received his 'call-up' papers from the Army and actually began his war service with the Lancashire Fusiliers, who he joined on the 15th December 1939 at the Wellington Barracks in Bury.

Returning to his time with the 13th King's and shortly after their arrival at Secunderabad in India, Leslie received the terrible news that his brother Roy, serving in the RNVR, had been killed in the Mediterranean whilst participating in the relief of Malta.

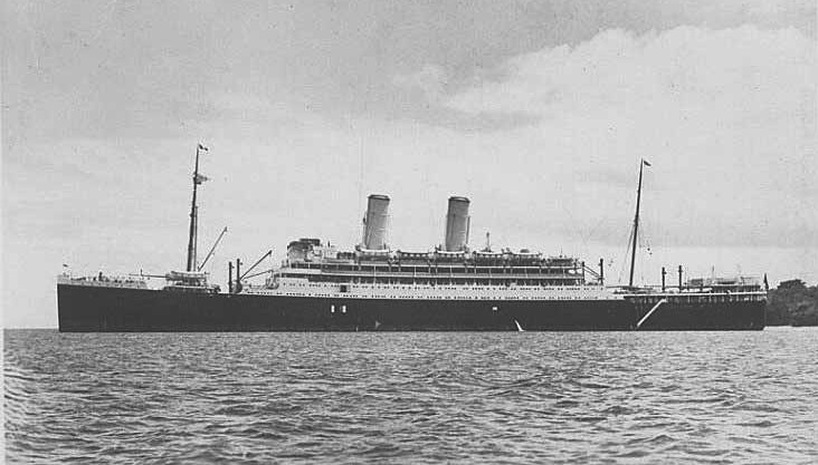

In India Leslie served with the 13th Kings as they performed a mixture of local policing and garrison duties. Here, he would work closely with senior officer, Major Kenneth Daintry Gilkes. The two men had built up a strong friendship during their time with the battalion, firstly on the south-east coastlines of England and then on the long voyage out to India aboard the troopship SS Oronsay.

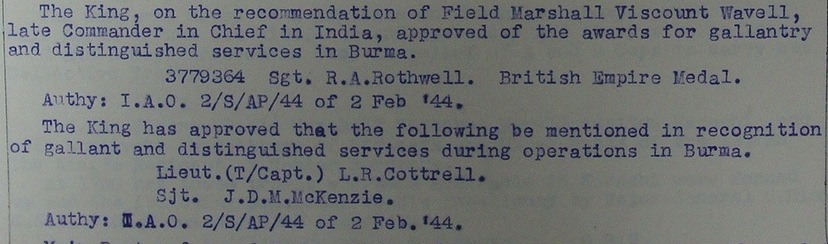

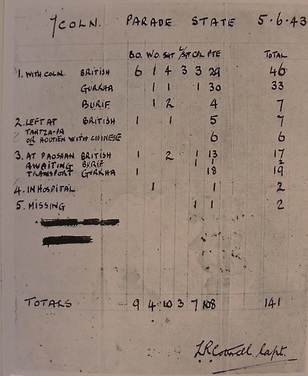

Cottrell was to become Adjutant to Kenneth Gilkes as he took command of Chindit Column 7 in preparation for Operation Longcloth. As Adjutant he would have been responsible for the Column's administration, organisation and discipline. He would also have the duty of recording the events of the Column's daily life in what is known as a War Diary. This daily discipline possibly encouraged Captain Cottrell to write down his own personal memoir of his experiences in India and Burma.

There has been no shortage of books written by the Chindits of 1943, but Column 7 has been perhaps the one unit where precious little has ever come to light, so we are very fortunate to have Cottrell's short journal to fall back on.

He had been part of the University Officer Training Corps which had been affiliated to the King's Regiment for many years, using the Regimental Seaforth Barracks as it's training base. Leslie was commissioned into the 13th Battalion in 1940 aged 21 and would eventually travel with them to India in late 1941.

NB. Shortly before his commission, Leslie had received his 'call-up' papers from the Army and actually began his war service with the Lancashire Fusiliers, who he joined on the 15th December 1939 at the Wellington Barracks in Bury.

Returning to his time with the 13th King's and shortly after their arrival at Secunderabad in India, Leslie received the terrible news that his brother Roy, serving in the RNVR, had been killed in the Mediterranean whilst participating in the relief of Malta.

In India Leslie served with the 13th Kings as they performed a mixture of local policing and garrison duties. Here, he would work closely with senior officer, Major Kenneth Daintry Gilkes. The two men had built up a strong friendship during their time with the battalion, firstly on the south-east coastlines of England and then on the long voyage out to India aboard the troopship SS Oronsay.

Cottrell was to become Adjutant to Kenneth Gilkes as he took command of Chindit Column 7 in preparation for Operation Longcloth. As Adjutant he would have been responsible for the Column's administration, organisation and discipline. He would also have the duty of recording the events of the Column's daily life in what is known as a War Diary. This daily discipline possibly encouraged Captain Cottrell to write down his own personal memoir of his experiences in India and Burma.

There has been no shortage of books written by the Chindits of 1943, but Column 7 has been perhaps the one unit where precious little has ever come to light, so we are very fortunate to have Cottrell's short journal to fall back on.

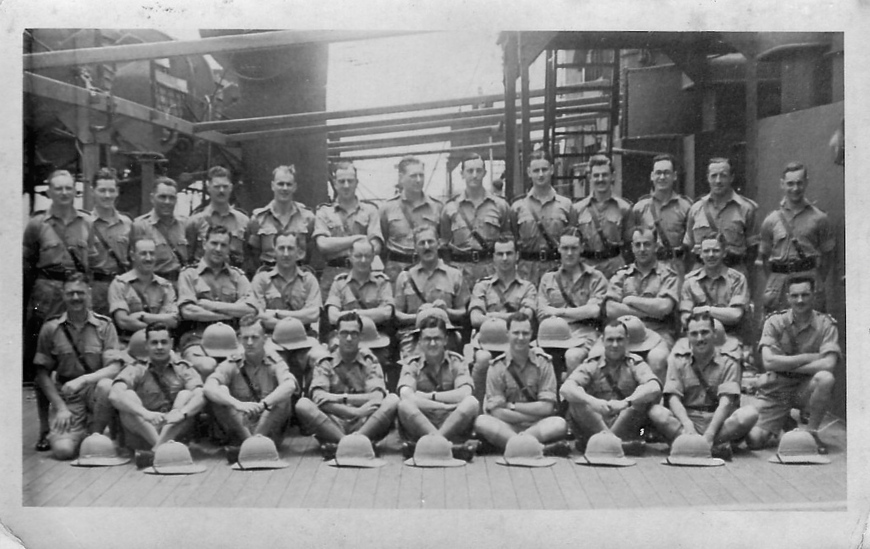

The photograph above shows some of the officers from the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment aboard the troopship SS Oronsay. This photograph, showing Leslie Cottrell in the centre of the front row was taken in early January 1942 whilst the troopship had docked at Durban, South Africa for re-stocking and re-fuelling. The men from the battalion spent five enjoyable days in Durban, taking a rest from the long voyage which would culminate at Bombay, India.

The battalion would end up at the Gough Barracks in Secunderabad, where they were assigned policing and garrison duties. For a more in depth look at the battalion's time during this period, please read the Voyage and Training pages from this website found here: Voyage and Training

Whilst residing at the Gough Barracks, Leslie Cottrell, like most officers at that time took on an Indian servant or bearer. He recalled:

On our arrival at Secunderabad, at the gates we noticed a largish gathering of Indian men, all seeking employment as bearers to the battalion. One approached me and showed me his written testimonials, some many years old, which had been written by other officers he had served. He seemed a nice enough man so I took him on. Joseph, for that was his name, was quite ecstatic when he realised he was once again in work and within a couple of hours, had cleaned my quarters, made my bed and unpacked my luggage.

Leslie Cottrell had started his Army service as a 2nd Lieutenant, but by the time he found himself in India and just before he became part of the first Chindit operation, he had been promoted to full Lieutenant. Further promotions in the coming months saw him attain the rank of Captain and then Adjutant of Column 7 whilst on operational duty in Burma.

Around April 1942 the area close to the Battalion's Head Quarters had suffered air-raids from long range Japanese bombers. On the 6th April it was decided to send an Anti-Aircraft and Ground Defence unit over to Bezwada to protect the local town from these attacks. Lieutenant Cottrell was given command of one of these units and early on the morning of the 7th April was sent over to Bezwada to set up the defence post.

From the King's Regimental War diary for that time, comes this quote:

The A/A Platoon under Lt. Cottrell moved off at 0730 hours, the duration of their stay is indefinite, but it is more than likely that they will see some action.

By the next day news of a tragic accident had reached the battalion Adjutant, Captain David Hastings, he reported in the diary that:

We heard today that one of the trucks carrying our men to Bezwada had overturned on the road and that one man was killed and four others injured. Details are yet unknown, but Major Stuart Lockhart and the Medical Officer left last night to attend to the men involved.

It appears that the truck fell down an embankment during a landslide and was not anyone's fault as such. One man was killed having been struck on the head by an ammunition box. The driver was seriously injured and the other men were still in a state of shock.

Sadly, by the 10th April and having never regained consciousness the driver also died. Thankfully, it seems that Leslie had not been one of the other men inside the unfortunate vehicle, but had been travelling in the truck just behind.

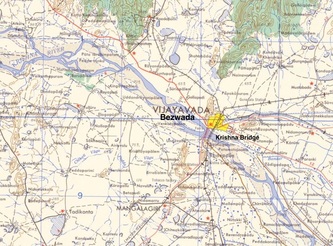

By matching up the dates of death with known 13th King's casualties for that time, I am confident that the driver of the truck was Lance Corporal Douglas Purchase and the other man Pte. Alfred Haines. Both men are buried in Madras War Cemetery, Chennai. Here are their CWGC details and photographs of their grave stones in Madras War Cemetery. Also shown is a map of Bezwada and the Krishna Bridge, the town was known colloquially as Bezwada, but was actually called Vijayavada. Please click on any of the images seen within this story to bring them forward on the page:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2173036/PURCHASE,%20DOUGLAS%20ALEC

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2172723/HAINES,%20ALFRED%20JAMES%20CHARLES

The battalion would end up at the Gough Barracks in Secunderabad, where they were assigned policing and garrison duties. For a more in depth look at the battalion's time during this period, please read the Voyage and Training pages from this website found here: Voyage and Training

Whilst residing at the Gough Barracks, Leslie Cottrell, like most officers at that time took on an Indian servant or bearer. He recalled:

On our arrival at Secunderabad, at the gates we noticed a largish gathering of Indian men, all seeking employment as bearers to the battalion. One approached me and showed me his written testimonials, some many years old, which had been written by other officers he had served. He seemed a nice enough man so I took him on. Joseph, for that was his name, was quite ecstatic when he realised he was once again in work and within a couple of hours, had cleaned my quarters, made my bed and unpacked my luggage.

Leslie Cottrell had started his Army service as a 2nd Lieutenant, but by the time he found himself in India and just before he became part of the first Chindit operation, he had been promoted to full Lieutenant. Further promotions in the coming months saw him attain the rank of Captain and then Adjutant of Column 7 whilst on operational duty in Burma.

Around April 1942 the area close to the Battalion's Head Quarters had suffered air-raids from long range Japanese bombers. On the 6th April it was decided to send an Anti-Aircraft and Ground Defence unit over to Bezwada to protect the local town from these attacks. Lieutenant Cottrell was given command of one of these units and early on the morning of the 7th April was sent over to Bezwada to set up the defence post.

From the King's Regimental War diary for that time, comes this quote:

The A/A Platoon under Lt. Cottrell moved off at 0730 hours, the duration of their stay is indefinite, but it is more than likely that they will see some action.

By the next day news of a tragic accident had reached the battalion Adjutant, Captain David Hastings, he reported in the diary that:

We heard today that one of the trucks carrying our men to Bezwada had overturned on the road and that one man was killed and four others injured. Details are yet unknown, but Major Stuart Lockhart and the Medical Officer left last night to attend to the men involved.

It appears that the truck fell down an embankment during a landslide and was not anyone's fault as such. One man was killed having been struck on the head by an ammunition box. The driver was seriously injured and the other men were still in a state of shock.

Sadly, by the 10th April and having never regained consciousness the driver also died. Thankfully, it seems that Leslie had not been one of the other men inside the unfortunate vehicle, but had been travelling in the truck just behind.

By matching up the dates of death with known 13th King's casualties for that time, I am confident that the driver of the truck was Lance Corporal Douglas Purchase and the other man Pte. Alfred Haines. Both men are buried in Madras War Cemetery, Chennai. Here are their CWGC details and photographs of their grave stones in Madras War Cemetery. Also shown is a map of Bezwada and the Krishna Bridge, the town was known colloquially as Bezwada, but was actually called Vijayavada. Please click on any of the images seen within this story to bring them forward on the page:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2173036/PURCHASE,%20DOUGLAS%20ALEC

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2172723/HAINES,%20ALFRED%20JAMES%20CHARLES

The memoir of Captain Leslie Cottrell and his time with the 13th Battalion the King's Regiment during the years of World War Two.

Wingate's Seventh Column.

Anyone at Glasgow Central Station one afternoon in August 1940 could have seen an unusual sight. Several trains arrived and all their passengers were men aged thirty. These men were in fact members of the thirty year-old age group who had been called up to join various Army units then forming in the Glasgow area. Eight hundred of them were recruits for 13th Battalion The King's Regiment, the regiment of Liverpool, which was coming into existence at the Jordan Hill Teacher Training College.

There the 13th King's received the traditional Infantry training. One year after the outbreak of war military equipment and weapons were still in desperately short supply and at first the battalion had only forty rifles and one two-inch mortar. After three months in Glasgow the battalion moved to the east coast of England to perform coastal defence duties at Felixstowe, Clacton-on-Sea, Mersea Island and other places. That's what these not so young men, many married and with young families, were good for; they were not and never would be elite, front-line troops.

But little did they know. As they patrolled the coast at night through uncharted minefields, they watched helplessly and angrily as the glow in the sky grow greater while the Luftwaffe bombed and set fire to London.

In the summer of 1941 the battalion moved again, this time to Burford in Oxfordshire, and rumours that they were to be sent to India appeared to be at least in part substantiated by the issue of tropical kit. A further move in late autumn took them to Blackburn. Then, late one afternoon in December, orders were given that at five o'clock the following morning the battalion would entrain for Riverside Station, Liverpool. This they did and at Canada Dock they boarded the Orient liner 'Oronsay'.

Many people had said that they were lucky being posted to India. There, they might have more difficult duties to perform as Gandhi's Congress Party became more civilly disobedient, but at least they would be spared the invasion of Europe.

In fact, while they had been on embarkation leave, the commanding officer had sent a telegram to his officers stating: "Strongly advise bring dinner jacket". But, on 7th December 1941, while the Oronsay with the 13th King's on board lay at anchor in the Mersey awaiting orders to sail, something utterly unexpected happened on the other side of the world. The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour. So, irony of ironies, when the 13th King's sailed the following day, they were sailing from one war to another more savage and barbaric war.

At the end of January 1942, after seven weeks at sea and four days ashore in South Africa, the 13th King's arrived at Bombay and were immediately sent to perform garrison duties in Secunderabad. There they spent three months living the gracious, if somewhat boring and monotonous life of a peace-time unit. Early rising, horse-riding before breakfast, half-hearted morning drill parades and a compulsory siesta, would be followed by football, hockey, tennis and squash. For the officers there was swimming at the Club, of which all officers had been elected members.

Wingate's Seventh Column.

Anyone at Glasgow Central Station one afternoon in August 1940 could have seen an unusual sight. Several trains arrived and all their passengers were men aged thirty. These men were in fact members of the thirty year-old age group who had been called up to join various Army units then forming in the Glasgow area. Eight hundred of them were recruits for 13th Battalion The King's Regiment, the regiment of Liverpool, which was coming into existence at the Jordan Hill Teacher Training College.

There the 13th King's received the traditional Infantry training. One year after the outbreak of war military equipment and weapons were still in desperately short supply and at first the battalion had only forty rifles and one two-inch mortar. After three months in Glasgow the battalion moved to the east coast of England to perform coastal defence duties at Felixstowe, Clacton-on-Sea, Mersea Island and other places. That's what these not so young men, many married and with young families, were good for; they were not and never would be elite, front-line troops.

But little did they know. As they patrolled the coast at night through uncharted minefields, they watched helplessly and angrily as the glow in the sky grow greater while the Luftwaffe bombed and set fire to London.

In the summer of 1941 the battalion moved again, this time to Burford in Oxfordshire, and rumours that they were to be sent to India appeared to be at least in part substantiated by the issue of tropical kit. A further move in late autumn took them to Blackburn. Then, late one afternoon in December, orders were given that at five o'clock the following morning the battalion would entrain for Riverside Station, Liverpool. This they did and at Canada Dock they boarded the Orient liner 'Oronsay'.

Many people had said that they were lucky being posted to India. There, they might have more difficult duties to perform as Gandhi's Congress Party became more civilly disobedient, but at least they would be spared the invasion of Europe.

In fact, while they had been on embarkation leave, the commanding officer had sent a telegram to his officers stating: "Strongly advise bring dinner jacket". But, on 7th December 1941, while the Oronsay with the 13th King's on board lay at anchor in the Mersey awaiting orders to sail, something utterly unexpected happened on the other side of the world. The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour. So, irony of ironies, when the 13th King's sailed the following day, they were sailing from one war to another more savage and barbaric war.

At the end of January 1942, after seven weeks at sea and four days ashore in South Africa, the 13th King's arrived at Bombay and were immediately sent to perform garrison duties in Secunderabad. There they spent three months living the gracious, if somewhat boring and monotonous life of a peace-time unit. Early rising, horse-riding before breakfast, half-hearted morning drill parades and a compulsory siesta, would be followed by football, hockey, tennis and squash. For the officers there was swimming at the Club, of which all officers had been elected members.

Memoir continues:

During this time the Japanese had swept through the Pacific, occupied Sumatra, Java and Malaya, captured Singapore and driven the British ignominiously out of Burma. Having bombed Vizagapatam and Cocanada on the east coast of India, and with Naval Forces in the Bay of Bengal, they now threatened the whole of the sub-continent. In most quarters the reaction to this threat appeared to be one of ostrich-like indifference. General Wavell, the Commander-in-Chief, and a few others alone realised the dreadful seriousness of the situation.

In May 1942 the commanding officer of the 13th King's returned from Delhi, whither he had been hastily summoned, to say that the battalion (those men now aged nearly thirty-three who had never been considered as front-line troops) had been selected to undergo special training in jungle warfare in the Central and United Provinces under the command of Brigadier Orde Charles WIngate.

Who was this soldier, Brigadier Orde Wingate? Educated at Charterhouse, he had been commissioned in 1923 from the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich into the Royal Artillery. In 1932 he had served with the Sudan Defence Force when, it is pertinent to point out, he had deliberately worked in great heat to assess his powers of endurance. Four years later he had been posted to Palestine where he had espoused the Zionist cause and formed and led guerrilla groups of Jews against the Arabs.

His success in Palestine has been considered as limited, but has probably been unfairly assessed. In 1940 he had played an active part in the Abyssinian Campaign and, alongside Emperor Haile Selassie, he had ridden into Addis Ababa at the head of the British Forces when the Italians had surrendered. It has been generally felt that the Italians had not been difficult to beat, so, again, Wingate's success has not been given the credit due to it.

Wingate appears always to have needed a cause for which to fight. Without one he became frustrated and depressed. In a fit of deep depression he had in fact once attempted to take his own life. The eventual reconquest of Burma now became his cause and for the next twelve months he was to dominate every waking hour of the 13th King's.

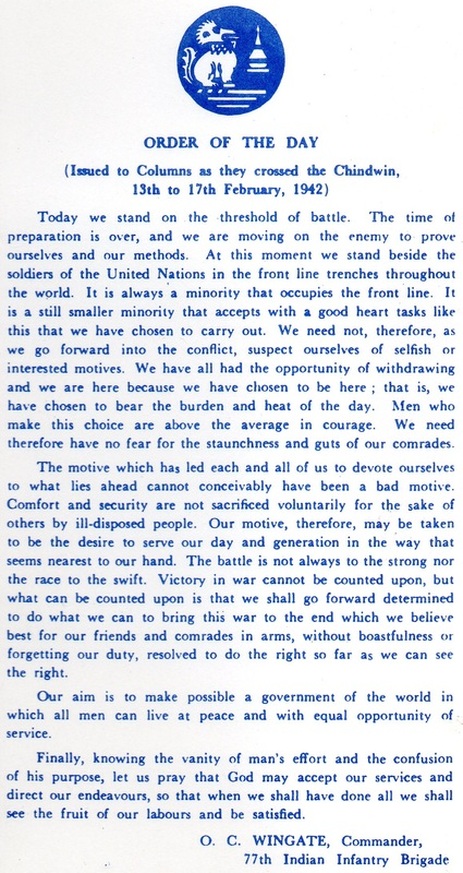

General Wavell had given Wingate a Brigade with which to operate in Burma. In addition to the 13th King's this Brigade, whose official designation was 77th Independent Infantry Brigade and whose troops later came to be known as Chindits, consisted of a battalion of Gurkhas, a battalion of Burma Rifles, a Company of 142 Commando, a mule transport company and eight RAF Sections.

The training of 77 Brigade was desperately tough and became almost a matter of mere survival when the monsoon broke. All men bore signs of their having fought the jungle until they had learned to treat it with respect. Most had jungle sores the size of a 10 pence piece and septic to the bone. Wingate led his Brigade through months of exhausting exercises during which they experienced great hardship and privation. In extreme heat his men made long marches; on meagre rations they carried heavy loads. Flooding rivers washed them out of their jungle camps and there were deaths due to drowning and accident. Daily routine was turned upside-down. Breakfast might be ordered for the middle of the night; the day's main meal could be omitted. Scores of men required medical treatment but reporting sick was viewed as moral weakness and Wingate discouraged it.

Yet under these tough conditions the 13th King's and the remainder of 77 Brigade learned a great deal. If they did not fight the jungle, it could be their friend for they could move in dense jungle very close to an enemy without being seen and, with practice, without being heard. They became experts in navigation with map and compass, they learned to move rapidly even in quite dense jungle and to turn up in places where they had never been expected; and in scrub country they learned to navigate with reasonable accuracy by the stars at night.

Above all they learned to survive; to obtain water from dried-up river beds by digging deep holes and waiting for the water to trickle through; to obtain water from creepers, if they cut a creeper hanging from the trees thirty or forty feet above no water would drip from it, but if they cut the same creeper in two places simultaneously water would eventually drip from the piece of creeper they had removed; to treat septic scratches caused by thorns of the ubiquitous lantana plant with the antiseptic juice contained in the leaves of the same plant; to deal with leeches, badoos (an Indian insect) and mosquitoes; and finally to make out of bamboo a host of useful and fiendish things, ranging from cooking pots to punji traps (a bamboo constructed booby trap often with poisoned sharpened tips).

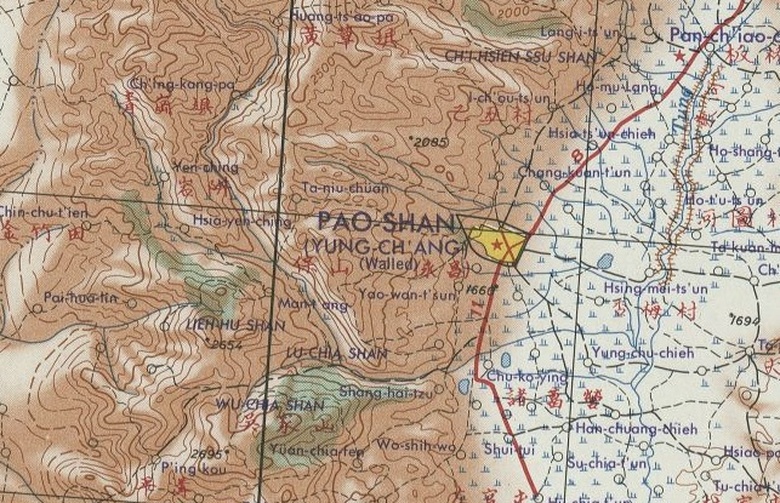

The shape of Burma, in which 77 Brigade was to operate, is that of two triangles forming a diamond. Initially the Brigade was to confine its operations to Northern Burma, the top triangle of the two. The natural features of the country, rivers and mountain ranges, run from north to south and this configuration has dictated the way in which the man-made communications, roads and railways run, namely from north to south also. Anyone moving from west to east or from east to west is moving against the grain of some of the most difficult country in the world. General Slim referred to the mountains west of the River Chindwin as "those hellish jungle mountains" and they are possibly not the most difficult mountains in Burma to cross.

Physically Northern Burma can be likened to your right hand. Your thumb represents the foothills of the Himalayas and the space between your thumb and forefinger Assam. Your forefinger is the mountains, six thousand feet high, on the Assam/Burma border, whilst the space between your forefinger and your second finger is the River Chindwin, a quarter of a mile wide and swift-flowing. Your second finger represents another range of mountains between three thousand and six thousand feet high. The next space represents the mighty River Irrawaddy, one mile wide. Finally there is the mountain range more than twelve thousand feet high behind which the River Salween carves its way.

Approximately sixty per cent of Burma is jungle, forest or woodland and the northern half is more densely forested than the southern. Of the hundred and fifty or so principal countries of the world only twenty are more densely forested than Burma. The jungles of Burma are formidable and in places the dankness of their vegetation renders them most unpleasant. There are dense, matted evergreens with thick creepers through which 77 Brigade had to hack every inch of their way.

In parts these jungles are treacherously swampy. There are magnificent forests of huge teak trees whose leaves are two or three times the size of dinner plates. A column of 77 Brigade struck a patch of jungle so dense that after cutting their way continuously for twenty-four hours they estimated that they had covered only three miles. The jungles contain a wide variety of wild animals, not all of which may be said to be friendly; a herd of about forty elephant with young were encountered; and a group of men, having run out of rations, were glad to be able to cook and eat python steaks.

During this time the Japanese had swept through the Pacific, occupied Sumatra, Java and Malaya, captured Singapore and driven the British ignominiously out of Burma. Having bombed Vizagapatam and Cocanada on the east coast of India, and with Naval Forces in the Bay of Bengal, they now threatened the whole of the sub-continent. In most quarters the reaction to this threat appeared to be one of ostrich-like indifference. General Wavell, the Commander-in-Chief, and a few others alone realised the dreadful seriousness of the situation.

In May 1942 the commanding officer of the 13th King's returned from Delhi, whither he had been hastily summoned, to say that the battalion (those men now aged nearly thirty-three who had never been considered as front-line troops) had been selected to undergo special training in jungle warfare in the Central and United Provinces under the command of Brigadier Orde Charles WIngate.

Who was this soldier, Brigadier Orde Wingate? Educated at Charterhouse, he had been commissioned in 1923 from the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich into the Royal Artillery. In 1932 he had served with the Sudan Defence Force when, it is pertinent to point out, he had deliberately worked in great heat to assess his powers of endurance. Four years later he had been posted to Palestine where he had espoused the Zionist cause and formed and led guerrilla groups of Jews against the Arabs.

His success in Palestine has been considered as limited, but has probably been unfairly assessed. In 1940 he had played an active part in the Abyssinian Campaign and, alongside Emperor Haile Selassie, he had ridden into Addis Ababa at the head of the British Forces when the Italians had surrendered. It has been generally felt that the Italians had not been difficult to beat, so, again, Wingate's success has not been given the credit due to it.

Wingate appears always to have needed a cause for which to fight. Without one he became frustrated and depressed. In a fit of deep depression he had in fact once attempted to take his own life. The eventual reconquest of Burma now became his cause and for the next twelve months he was to dominate every waking hour of the 13th King's.

General Wavell had given Wingate a Brigade with which to operate in Burma. In addition to the 13th King's this Brigade, whose official designation was 77th Independent Infantry Brigade and whose troops later came to be known as Chindits, consisted of a battalion of Gurkhas, a battalion of Burma Rifles, a Company of 142 Commando, a mule transport company and eight RAF Sections.

The training of 77 Brigade was desperately tough and became almost a matter of mere survival when the monsoon broke. All men bore signs of their having fought the jungle until they had learned to treat it with respect. Most had jungle sores the size of a 10 pence piece and septic to the bone. Wingate led his Brigade through months of exhausting exercises during which they experienced great hardship and privation. In extreme heat his men made long marches; on meagre rations they carried heavy loads. Flooding rivers washed them out of their jungle camps and there were deaths due to drowning and accident. Daily routine was turned upside-down. Breakfast might be ordered for the middle of the night; the day's main meal could be omitted. Scores of men required medical treatment but reporting sick was viewed as moral weakness and Wingate discouraged it.

Yet under these tough conditions the 13th King's and the remainder of 77 Brigade learned a great deal. If they did not fight the jungle, it could be their friend for they could move in dense jungle very close to an enemy without being seen and, with practice, without being heard. They became experts in navigation with map and compass, they learned to move rapidly even in quite dense jungle and to turn up in places where they had never been expected; and in scrub country they learned to navigate with reasonable accuracy by the stars at night.

Above all they learned to survive; to obtain water from dried-up river beds by digging deep holes and waiting for the water to trickle through; to obtain water from creepers, if they cut a creeper hanging from the trees thirty or forty feet above no water would drip from it, but if they cut the same creeper in two places simultaneously water would eventually drip from the piece of creeper they had removed; to treat septic scratches caused by thorns of the ubiquitous lantana plant with the antiseptic juice contained in the leaves of the same plant; to deal with leeches, badoos (an Indian insect) and mosquitoes; and finally to make out of bamboo a host of useful and fiendish things, ranging from cooking pots to punji traps (a bamboo constructed booby trap often with poisoned sharpened tips).

The shape of Burma, in which 77 Brigade was to operate, is that of two triangles forming a diamond. Initially the Brigade was to confine its operations to Northern Burma, the top triangle of the two. The natural features of the country, rivers and mountain ranges, run from north to south and this configuration has dictated the way in which the man-made communications, roads and railways run, namely from north to south also. Anyone moving from west to east or from east to west is moving against the grain of some of the most difficult country in the world. General Slim referred to the mountains west of the River Chindwin as "those hellish jungle mountains" and they are possibly not the most difficult mountains in Burma to cross.

Physically Northern Burma can be likened to your right hand. Your thumb represents the foothills of the Himalayas and the space between your thumb and forefinger Assam. Your forefinger is the mountains, six thousand feet high, on the Assam/Burma border, whilst the space between your forefinger and your second finger is the River Chindwin, a quarter of a mile wide and swift-flowing. Your second finger represents another range of mountains between three thousand and six thousand feet high. The next space represents the mighty River Irrawaddy, one mile wide. Finally there is the mountain range more than twelve thousand feet high behind which the River Salween carves its way.

Approximately sixty per cent of Burma is jungle, forest or woodland and the northern half is more densely forested than the southern. Of the hundred and fifty or so principal countries of the world only twenty are more densely forested than Burma. The jungles of Burma are formidable and in places the dankness of their vegetation renders them most unpleasant. There are dense, matted evergreens with thick creepers through which 77 Brigade had to hack every inch of their way.

In parts these jungles are treacherously swampy. There are magnificent forests of huge teak trees whose leaves are two or three times the size of dinner plates. A column of 77 Brigade struck a patch of jungle so dense that after cutting their way continuously for twenty-four hours they estimated that they had covered only three miles. The jungles contain a wide variety of wild animals, not all of which may be said to be friendly; a herd of about forty elephant with young were encountered; and a group of men, having run out of rations, were glad to be able to cook and eat python steaks.

Kenneth Daintry Gilkes, 7 Column Commander.

Kenneth Daintry Gilkes, 7 Column Commander.

Cottrell's memoir continues:

The intention of the Indian High Command in 1943 was to recapture Northern Burma. This would be carried out by British troops attacking from the Assam front, simultaneously with Chiang Kai-Shek's troops attacking from the Yunnan front in the east. The special role of 77 Brigade was to operate as long-range penetration groups ahead of the main British advance.

Long-range penetration groups are bodies of men capable of rapid movement, up to thirty miles a day under very good conditions, turning up at their objective unexpectedly, taking the enemy by surprise and on terms of their choosing, and then vanishing as it were into thin air.

They attempt to prevent the enemy from having the advantage and will only fight him when they themselves have it. If they can do this a hundred miles behind what the enemy considered to be his foremost positions they will have him baffled and worried. There is nothing new about long-range penetration; it is as old as war itself. Brigadier Wingate was amongst the first and the few to appreciate how effective it might be in jungle and densely forested terrain.

The theory of long-range penetration inevitably rules out lines of communication on the ground. How then is a long-range penetration group to be supplied? In 1942 Wingate's answer to this apparently unanswerable question was completely revolutionary. 77th Brigade would be supplied by air and they would be in communication with their air base and with each other by wireless.

Apart from General Wavell, there was scarcely another high-ranking commander who considered that Wingate's theory and all it implied would work in practice. Indeed, he came in for the most serious criticism. The supplying by air of three thousand troops and a thousand animals was considered completely unfeasible. Medical opinion was that British troops would not be able to resist disease; if the Japanese did not kill Wingate's troops, then beri-beri, dysentery and malaria would surely do so. A sick or wounded soldier had the right to be evacuated to hospital and there was no way in which this might be done.

There were certain firm traditions which could not be overcome. Gurkhas had always been used to returning to a firm base at night and they would not even participate in a campaign in which it was not possible to do so. British troops were used to having their meals cooked for them; they could not be expected to survive for long if, like boy scouts, they had to cook for themselves in small groups round their own little fires.

The receipt of mail would be difficult, its despatch impossible and in consequence the morale of men would be adversely affected. Finally, Wavell himself was believed to doubt whether British troops were physically and mentally equipped to beat the Japanese in the jungle.

Wingate's answers to these criticisms were courageous and typical of the man, though many thought, not wholly satisfactory. Casualties would be left in the care of friendly village Headmen who would be given money to look after them and clearly informed that, depending upon how they treated these casualties, they would be rewarded or punished when the war was won.

Men's mail would be dropped to them from the air with their rations and other supplies, and personnel at air base would write regularly to the next-of-kin of all troops, saying that they were alive and well though in no position to write home themselves. As to the other criticisms they could only be proved valid or not if Wingate's theories were in fact put to the test.

In January 1943 77 Brigade moved by train (it took 9 locomotives, several carriages in length to transport the whole Brigade) to the railhead at Dimapur in north-eastern Assam. Manipur Road, the only supply route to the 4 Corps front, passes through mountains of breath-taking grandeur and was in those days, and may still be an un-metalled road. Carrying full loads of sixty pounds, men of the Brigade covered the one hundred and thirty-three miles to Imphal in eight nights. They marched at night for security reasons and because the narrow road was reserved during the hours of daylight for use by motorised transport.

At Imphal, Wavell, who had flown there especially to see Wingate, delivered his bombshell. He said that the movement of 4 Corps had been stopped because Chiang Kai-Shek would not agree to the advance of his troops, and that in consequence 77 Brigade's entry into Burma was pointless. Indignantly, yet persuasively, Wingate protested that in every way his forces were prepared and that G.H.Q. would go on denying his theories if he were not allowed to put them to the test. He also advanced a more feeble argument, that his Brigade in Burma might divert Japanese attention from the beleaguered outpost at Fort Hertz.

Wavell pondered hard and long and then, displaying complete confidence in Wingate, he gave his permission for 77 Brigade to enter Burma. Under these circumstances it would have been normal for the Brigade to salute the Commander-in-Chief, but instead, because Wavell considered the expedition which was about to begin so hazardous, he saluted 77 Brigade.

77 Brigade consisted of a Brigade Headquarters with, of course, Wingate himself in command, and two groups. 1 Group comprised two columns and 2 Group five columns. Each column was made up of a company of British or Gurkha troops, a platoon of Burmese troops (Kachins or Karens) who could operate in civilian clothes as well as in uniform, a section of 142 Commando who were experts in demolition work, a hundred mules and a hundred mule-leaders and an R.A.F. section commanded by a Flight Lieutenant.

The R.A.F. section played a vital role in each column because it was responsible for operating the R.A.F. wireless set - the most powerful wireless set the British had out east at that time - and thereby maintaining essential communications with the Brigade's air base at Agartala in Assam. There was some justification for the contemptuous referring to this heterogeneous organisation as Fred Karno's Army.

The intention of the Indian High Command in 1943 was to recapture Northern Burma. This would be carried out by British troops attacking from the Assam front, simultaneously with Chiang Kai-Shek's troops attacking from the Yunnan front in the east. The special role of 77 Brigade was to operate as long-range penetration groups ahead of the main British advance.

Long-range penetration groups are bodies of men capable of rapid movement, up to thirty miles a day under very good conditions, turning up at their objective unexpectedly, taking the enemy by surprise and on terms of their choosing, and then vanishing as it were into thin air.

They attempt to prevent the enemy from having the advantage and will only fight him when they themselves have it. If they can do this a hundred miles behind what the enemy considered to be his foremost positions they will have him baffled and worried. There is nothing new about long-range penetration; it is as old as war itself. Brigadier Wingate was amongst the first and the few to appreciate how effective it might be in jungle and densely forested terrain.

The theory of long-range penetration inevitably rules out lines of communication on the ground. How then is a long-range penetration group to be supplied? In 1942 Wingate's answer to this apparently unanswerable question was completely revolutionary. 77th Brigade would be supplied by air and they would be in communication with their air base and with each other by wireless.

Apart from General Wavell, there was scarcely another high-ranking commander who considered that Wingate's theory and all it implied would work in practice. Indeed, he came in for the most serious criticism. The supplying by air of three thousand troops and a thousand animals was considered completely unfeasible. Medical opinion was that British troops would not be able to resist disease; if the Japanese did not kill Wingate's troops, then beri-beri, dysentery and malaria would surely do so. A sick or wounded soldier had the right to be evacuated to hospital and there was no way in which this might be done.

There were certain firm traditions which could not be overcome. Gurkhas had always been used to returning to a firm base at night and they would not even participate in a campaign in which it was not possible to do so. British troops were used to having their meals cooked for them; they could not be expected to survive for long if, like boy scouts, they had to cook for themselves in small groups round their own little fires.

The receipt of mail would be difficult, its despatch impossible and in consequence the morale of men would be adversely affected. Finally, Wavell himself was believed to doubt whether British troops were physically and mentally equipped to beat the Japanese in the jungle.

Wingate's answers to these criticisms were courageous and typical of the man, though many thought, not wholly satisfactory. Casualties would be left in the care of friendly village Headmen who would be given money to look after them and clearly informed that, depending upon how they treated these casualties, they would be rewarded or punished when the war was won.

Men's mail would be dropped to them from the air with their rations and other supplies, and personnel at air base would write regularly to the next-of-kin of all troops, saying that they were alive and well though in no position to write home themselves. As to the other criticisms they could only be proved valid or not if Wingate's theories were in fact put to the test.

In January 1943 77 Brigade moved by train (it took 9 locomotives, several carriages in length to transport the whole Brigade) to the railhead at Dimapur in north-eastern Assam. Manipur Road, the only supply route to the 4 Corps front, passes through mountains of breath-taking grandeur and was in those days, and may still be an un-metalled road. Carrying full loads of sixty pounds, men of the Brigade covered the one hundred and thirty-three miles to Imphal in eight nights. They marched at night for security reasons and because the narrow road was reserved during the hours of daylight for use by motorised transport.

At Imphal, Wavell, who had flown there especially to see Wingate, delivered his bombshell. He said that the movement of 4 Corps had been stopped because Chiang Kai-Shek would not agree to the advance of his troops, and that in consequence 77 Brigade's entry into Burma was pointless. Indignantly, yet persuasively, Wingate protested that in every way his forces were prepared and that G.H.Q. would go on denying his theories if he were not allowed to put them to the test. He also advanced a more feeble argument, that his Brigade in Burma might divert Japanese attention from the beleaguered outpost at Fort Hertz.

Wavell pondered hard and long and then, displaying complete confidence in Wingate, he gave his permission for 77 Brigade to enter Burma. Under these circumstances it would have been normal for the Brigade to salute the Commander-in-Chief, but instead, because Wavell considered the expedition which was about to begin so hazardous, he saluted 77 Brigade.

77 Brigade consisted of a Brigade Headquarters with, of course, Wingate himself in command, and two groups. 1 Group comprised two columns and 2 Group five columns. Each column was made up of a company of British or Gurkha troops, a platoon of Burmese troops (Kachins or Karens) who could operate in civilian clothes as well as in uniform, a section of 142 Commando who were experts in demolition work, a hundred mules and a hundred mule-leaders and an R.A.F. section commanded by a Flight Lieutenant.

The R.A.F. section played a vital role in each column because it was responsible for operating the R.A.F. wireless set - the most powerful wireless set the British had out east at that time - and thereby maintaining essential communications with the Brigade's air base at Agartala in Assam. There was some justification for the contemptuous referring to this heterogeneous organisation as Fred Karno's Army.

Leslie Cottrell remembers:

In the second week in February 1943 the various units of 77 Brigade headed for the River Chindwin. They could of course operate separately, or as two or more columns working together, since they were in daily touch with Wingate by wireless. Their objectives now were vastly different from what they would have originally been. Their orders were to harass and ambush the enemy, to destroy weak forces and lightly guarded installations, to carry out general reconnaissance and to map new roads which the Japanese were constructing.

One of their major tasks was the destruction of the railway line running from Mandalay to Myitkyina. Anyone stopping to think for a moment, will appreciate that what 77 Brigade was proposing to do was commit an act of bare-faced impudence by entering a country from which the Japanese had decisively expelled them less than a year before. The Japanese were unlikely to have a welcoming committee to receive them.

From this point onwards it is possible to describe the exploits of only one of the 13th King's columns, 7 Column under the command of Major K.D. Gilkes. They crossed the Assam/Burma border at midnight on 13th February 1943 and two days later reached the River Chindwin where they were at once confronted with a major problem. How were they to get one hundred and thirty animals across a swiftly flowing river a quarter of a mile wide?

The few bullocks with the column did the trick. The Chindits bellowed and waved their arms about, the bullocks entered the water and the other animals, mules and horses, followed. One officer finished up hanging on to a bullock's tail and arrived naked on the east bank as night fell. Fortunately for him an efficient batman turned up with his clothes two hours later.

Once to the east of the Chindwin, 7 Column took its first supply drop. Happily this drop was unopposed by the enemy, for it was during supply drops that a column was at its most vulnerable. The procedure was as follows. Forty-eight hours before supplies were required a dropping area was selected from the map by the column commander in consultation with the R.A.F. officer. Because supplies were most easily taken on open ground which could usually be expected close to habitation, where villagers had their paddy-fields, the dropping area was chosen close to a village.

A signal in cipher giving a list of the supplies required and the map reference of the supply area was then sent to air base at Agartala. Next, the column would move to the dropping area, aiming to arrive there a very short time before the DC3s or Hudson transports delivering the supplies were expected. A small number of men would debouch from the jungle and mark out the actual dropping zone, a rectangle four hundred yards long and one hundred yards wide, by lighting fires at intervals along one of the long and one of the short sides.

When the aircraft arrived they would receive a green or red signal from the ground, depending on whether or not it was safe to proceed with the drop. Most supplies were dropped using statichutes, but some were free-dropped with greater success than might have been expected. The R.A.F. performed miracles in making deliveries to columns who had unavoidably needed to choose places for their supply drops which were almost inaccessible to the supply aircraft. It was unsafe for a column to remain long in a dropping area and therefore supplies had to be picked up and fairly distributed with all speed.

The Japanese quickly realised that enemy troops were being supplied by air and they craftily instructed village Headmen to light fires on the ground beneath circling aircraft. It would follow that the British were more than likely within the circle of fires. More than once a column was trapped in such a way, but it was able to fade into the jungle before Japanese reinforcements could be called up.

Of 7 Column's next two supply drops one was opposed by the Japanese, but nevertheless successfully taken, and the other had to be completely abandoned owing to the strength of the forces the enemy had in the area which had been selected.

7 Column trailed it's coat, marching blatantly down the Pinbon/Pinlebu Road for twenty-four hours to distract the attention of the Japanese from another column which was moving swiftly to destroy the Mandalay/Myitkyina railway line. This was a very dangerous role for 7 Column because the Japanese were advancing to meet them with eight hundred troops of which some were motorised.

At the critical moment the column faded into the jungle, calmly took a supply drop and headed towards Wuntho, a town they had been ordered to attack. However, some of the column's Burmese troops wearing civilian dress had been into the town and reported that the Japanese Garrison had been strongly reinforced. In accordance with the basic principles of long-range penetration the attack was therefore called off.

It is now known that the Japanese had two divisions in Burma and later brought two more into Northern Burma to hunt out Wingate's Columns. There were therefore about twenty thousand Japanese searching for the Chindits.

The Japanese would have been more successful in doing this had they not shown an extreme reluctance to move through the jungle. If they had not relied on patrols moving along roads and jungle tracks there would have undoubtedly been more encounters with the British. Moreover, these patrols were very likely to be ambushed by the Chindits. General Mutaguchi, the Japanese commander in Burma, has since said that he did not know for some time whether he was dealing with a full-scale invasion of Northern Burma or merely with strong patrols, and that the Chindits had him completely baffled.

In the second week in February 1943 the various units of 77 Brigade headed for the River Chindwin. They could of course operate separately, or as two or more columns working together, since they were in daily touch with Wingate by wireless. Their objectives now were vastly different from what they would have originally been. Their orders were to harass and ambush the enemy, to destroy weak forces and lightly guarded installations, to carry out general reconnaissance and to map new roads which the Japanese were constructing.

One of their major tasks was the destruction of the railway line running from Mandalay to Myitkyina. Anyone stopping to think for a moment, will appreciate that what 77 Brigade was proposing to do was commit an act of bare-faced impudence by entering a country from which the Japanese had decisively expelled them less than a year before. The Japanese were unlikely to have a welcoming committee to receive them.

From this point onwards it is possible to describe the exploits of only one of the 13th King's columns, 7 Column under the command of Major K.D. Gilkes. They crossed the Assam/Burma border at midnight on 13th February 1943 and two days later reached the River Chindwin where they were at once confronted with a major problem. How were they to get one hundred and thirty animals across a swiftly flowing river a quarter of a mile wide?

The few bullocks with the column did the trick. The Chindits bellowed and waved their arms about, the bullocks entered the water and the other animals, mules and horses, followed. One officer finished up hanging on to a bullock's tail and arrived naked on the east bank as night fell. Fortunately for him an efficient batman turned up with his clothes two hours later.

Once to the east of the Chindwin, 7 Column took its first supply drop. Happily this drop was unopposed by the enemy, for it was during supply drops that a column was at its most vulnerable. The procedure was as follows. Forty-eight hours before supplies were required a dropping area was selected from the map by the column commander in consultation with the R.A.F. officer. Because supplies were most easily taken on open ground which could usually be expected close to habitation, where villagers had their paddy-fields, the dropping area was chosen close to a village.

A signal in cipher giving a list of the supplies required and the map reference of the supply area was then sent to air base at Agartala. Next, the column would move to the dropping area, aiming to arrive there a very short time before the DC3s or Hudson transports delivering the supplies were expected. A small number of men would debouch from the jungle and mark out the actual dropping zone, a rectangle four hundred yards long and one hundred yards wide, by lighting fires at intervals along one of the long and one of the short sides.

When the aircraft arrived they would receive a green or red signal from the ground, depending on whether or not it was safe to proceed with the drop. Most supplies were dropped using statichutes, but some were free-dropped with greater success than might have been expected. The R.A.F. performed miracles in making deliveries to columns who had unavoidably needed to choose places for their supply drops which were almost inaccessible to the supply aircraft. It was unsafe for a column to remain long in a dropping area and therefore supplies had to be picked up and fairly distributed with all speed.

The Japanese quickly realised that enemy troops were being supplied by air and they craftily instructed village Headmen to light fires on the ground beneath circling aircraft. It would follow that the British were more than likely within the circle of fires. More than once a column was trapped in such a way, but it was able to fade into the jungle before Japanese reinforcements could be called up.

Of 7 Column's next two supply drops one was opposed by the Japanese, but nevertheless successfully taken, and the other had to be completely abandoned owing to the strength of the forces the enemy had in the area which had been selected.

7 Column trailed it's coat, marching blatantly down the Pinbon/Pinlebu Road for twenty-four hours to distract the attention of the Japanese from another column which was moving swiftly to destroy the Mandalay/Myitkyina railway line. This was a very dangerous role for 7 Column because the Japanese were advancing to meet them with eight hundred troops of which some were motorised.

At the critical moment the column faded into the jungle, calmly took a supply drop and headed towards Wuntho, a town they had been ordered to attack. However, some of the column's Burmese troops wearing civilian dress had been into the town and reported that the Japanese Garrison had been strongly reinforced. In accordance with the basic principles of long-range penetration the attack was therefore called off.

It is now known that the Japanese had two divisions in Burma and later brought two more into Northern Burma to hunt out Wingate's Columns. There were therefore about twenty thousand Japanese searching for the Chindits.

The Japanese would have been more successful in doing this had they not shown an extreme reluctance to move through the jungle. If they had not relied on patrols moving along roads and jungle tracks there would have undoubtedly been more encounters with the British. Moreover, these patrols were very likely to be ambushed by the Chindits. General Mutaguchi, the Japanese commander in Burma, has since said that he did not know for some time whether he was dealing with a full-scale invasion of Northern Burma or merely with strong patrols, and that the Chindits had him completely baffled.

As all columns now approached the River Irrawaddy, Wingate had to answer the agonising question whether he should put two rivers between his Brigade and safety. Eventually he decided for good or ill to cross. The crossings of some columns were opposed, though 7 Column encountered no opposition. It was then, however, that trouble began.

Many mules and horses, underfed and overworked after thirty-three days of heavy load-carrying over difficult country, did not have the strength to swim across the Irrawaddy and had to be destroyed on the west bank. Any loads they were carrying had to be jettisoned. The precious wireless sets were allotted to the strongest mules which managed to reach the east bank.

Moreover, 77 Brigade now had no clear objectives. For two weeks 7 Column were constantly on the move, turning up in unexpected places and still hoping to mystify the Japanese and make them believe that they were a far larger force than they really were. After all, it could be argued, only a large force would have dared to advance so far into an occupied country. Then, unexpectedly, orders were received from India that the Chindits were to withdraw, before the monsoon broke and made withdrawal virtually impossible.

7 Column made a forced march of a day and a night and regained the Irrawaddy at dawn to discover that they could find but one boat with which to re-cross. A small party was ordered to take this boat and reconnoitre the west bank. The boat moved slowly into mid-river in the stillness of the dawn, a stillness suddenly shattered by the chatter of medium machine guns. The occupants of that boat, which received direct hits, were never seen again.

NB. At this moment both Wingate's HQ and Column 8 were also on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy with Column 7, they were situated near the town of Inywa, which was close to the spot where they had crossed over originally. The idea being that the Japanese would not think they would dare return from whence they had come.

Leslie Cottrell continues:

When strong Japanese Forces were observed on the west bank, it became evident that a whole column attempting to cross at that point would be annihilated. 7 Column therefore withdrew into the jungle to make an appreciation of the situation; and the Administrative Officer, writing up the day's events in the War Diary, wryly noted the date. It was 1st April.

7 Column were now in an even more desperate situation than they had previously imagined, for not only did they have the Irrawaddy to their west, but they also had a major tributary of it, the River Shweli, to their north and to their east. They were trapped on three sides by water.

That night they approached the Shweli but could not even reach the waters edge because of thick reeds stretching a hundred yards out into the river. The next night they approached the Shweli again, but in the course of several hours, succeeded in putting only one officer and sixty men across. It was considered unwise to remain longer endeavouring to put the whole column across as, according to intelligence reports, the river was under close scrutiny by the Japanese.

In such a situation the military manuals tell you to do what the enemy least expects you to do. So 7 Column moved south and were still doing so a fortnight after receiving orders so withdraw. They engaged and drove a Japanese force out of the village of Hintha-Baw at a cost of two wounded.

In bivouac two nights later the Column Commander, Major Gilkes, held a council of war with his most senior officers.

They would decide with him how to get out of the trap. Major Gilkes said that he had always considered withdrawal to China a possibility. Indeed, at the time of the final pre-operational Brigade orders, he had asked that when the withdrawal was ordered 7 Column might come out through China and that Wingate had given his permission for them to do so. Withdrawal to China, however, had very serious implications.

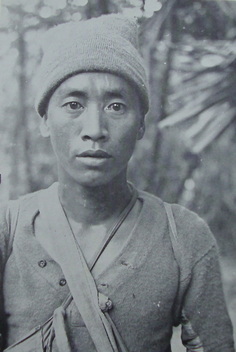

At this time some 100 men from Column 5 had joined up with Major Gilkes at the Shweli River. These men, including my grandfather, were in a very bad way indeed. Gilkes realised that it was time to split the column up into smaller dispersal groups.

Taken from the Column 7 War diary for 1943, here is an extract describing that decision:

"On 9th April, it was decided to split the column up. Gilkes would take half of the men and head firstly eastward before turning out along a more northern route. Captain Cottrell, Lieutenants Walker, Wood and Campbell-Patterson, each with 20 to 30 men, were to cross the Irrawaddy independently and then reunite for a supply dropping on the west side of the river.

On 10th April, with their packs and their bellies full, they split up into two groups, the stronger and weaker. Lieutenant Walker, together with Captain Aird, the 5 Column Medical Officer, Lieutenants Hector and Anderson-Williams and 25 Other Ranks, went off west across the Irrawaddy. The rest of the column moved off South East and after crossing the Mongmit-Myitson Road there was a minor clash between the rearguard and a Japanese patrol, with the enemy thankfully coming off worse."

Of the twenty five or so men from Rex Walker's dispersal group none were to ever reach the safety of India in 1943. For more information about this group, please click on the link below:

Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

Many mules and horses, underfed and overworked after thirty-three days of heavy load-carrying over difficult country, did not have the strength to swim across the Irrawaddy and had to be destroyed on the west bank. Any loads they were carrying had to be jettisoned. The precious wireless sets were allotted to the strongest mules which managed to reach the east bank.

Moreover, 77 Brigade now had no clear objectives. For two weeks 7 Column were constantly on the move, turning up in unexpected places and still hoping to mystify the Japanese and make them believe that they were a far larger force than they really were. After all, it could be argued, only a large force would have dared to advance so far into an occupied country. Then, unexpectedly, orders were received from India that the Chindits were to withdraw, before the monsoon broke and made withdrawal virtually impossible.

7 Column made a forced march of a day and a night and regained the Irrawaddy at dawn to discover that they could find but one boat with which to re-cross. A small party was ordered to take this boat and reconnoitre the west bank. The boat moved slowly into mid-river in the stillness of the dawn, a stillness suddenly shattered by the chatter of medium machine guns. The occupants of that boat, which received direct hits, were never seen again.

NB. At this moment both Wingate's HQ and Column 8 were also on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy with Column 7, they were situated near the town of Inywa, which was close to the spot where they had crossed over originally. The idea being that the Japanese would not think they would dare return from whence they had come.

Leslie Cottrell continues:

When strong Japanese Forces were observed on the west bank, it became evident that a whole column attempting to cross at that point would be annihilated. 7 Column therefore withdrew into the jungle to make an appreciation of the situation; and the Administrative Officer, writing up the day's events in the War Diary, wryly noted the date. It was 1st April.

7 Column were now in an even more desperate situation than they had previously imagined, for not only did they have the Irrawaddy to their west, but they also had a major tributary of it, the River Shweli, to their north and to their east. They were trapped on three sides by water.

That night they approached the Shweli but could not even reach the waters edge because of thick reeds stretching a hundred yards out into the river. The next night they approached the Shweli again, but in the course of several hours, succeeded in putting only one officer and sixty men across. It was considered unwise to remain longer endeavouring to put the whole column across as, according to intelligence reports, the river was under close scrutiny by the Japanese.

In such a situation the military manuals tell you to do what the enemy least expects you to do. So 7 Column moved south and were still doing so a fortnight after receiving orders so withdraw. They engaged and drove a Japanese force out of the village of Hintha-Baw at a cost of two wounded.

In bivouac two nights later the Column Commander, Major Gilkes, held a council of war with his most senior officers.

They would decide with him how to get out of the trap. Major Gilkes said that he had always considered withdrawal to China a possibility. Indeed, at the time of the final pre-operational Brigade orders, he had asked that when the withdrawal was ordered 7 Column might come out through China and that Wingate had given his permission for them to do so. Withdrawal to China, however, had very serious implications.

At this time some 100 men from Column 5 had joined up with Major Gilkes at the Shweli River. These men, including my grandfather, were in a very bad way indeed. Gilkes realised that it was time to split the column up into smaller dispersal groups.

Taken from the Column 7 War diary for 1943, here is an extract describing that decision:

"On 9th April, it was decided to split the column up. Gilkes would take half of the men and head firstly eastward before turning out along a more northern route. Captain Cottrell, Lieutenants Walker, Wood and Campbell-Patterson, each with 20 to 30 men, were to cross the Irrawaddy independently and then reunite for a supply dropping on the west side of the river.

On 10th April, with their packs and their bellies full, they split up into two groups, the stronger and weaker. Lieutenant Walker, together with Captain Aird, the 5 Column Medical Officer, Lieutenants Hector and Anderson-Williams and 25 Other Ranks, went off west across the Irrawaddy. The rest of the column moved off South East and after crossing the Mongmit-Myitson Road there was a minor clash between the rearguard and a Japanese patrol, with the enemy thankfully coming off worse."

Of the twenty five or so men from Rex Walker's dispersal group none were to ever reach the safety of India in 1943. For more information about this group, please click on the link below:

Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

After the men from Column 7 returned to India that year, Captain Cottrell supplied a witness statement to the Army Personnel Centre in regards to the fate of Lieutenant Rex Walker (see above) and his dispersal group. Here is a transcription of that report:

Statement of evidence 24th of July 1943.

Witness. 138760 Capt. L.R. Cottrell.

"I was Staff Officer of number seven Column, during Brigadier Wingate's Burma expedition. On April 10th, 1943 the Column Commander decided for various tactical and administrative reasons to split his column. This was midway between the Mongmit and the Myitson Road.

Lieutenant Walker was ordered to take charge of a party which consisted of three other officers and 25 British Other Ranks. His orders were to march approximately westward re-cross the Irrawaddy and return to Assam by the most direct route. The British Other Ranks were not considered by the Column Commander or by the Medical Officer as physically capable of marching the long way out via China, as the main body intended to do.

They were all equipped with arms and ammunition and had two days hard scale rations each, the officers had maps and compasses. An Air Supply drop was arranged for them just west of the Irrawaddy, but, the party failed to make the rendezvous and the aircraft concerned did not locate them. The Japanese were fairly active in this area. Nothing has been heard of any of these Officers or men since."

Signed Leslie Cottrell, Captain 13th KLR.

Counter-signed H. Cotton, Captain 13 KLR.

It is clear to me that Leslie Cottrell felt a great sense of responsibility to ensure that everything known about the missing and the lost was collated and recorded as early as possible after his return to India. He had written down information about the men from his unit and their last known whereabouts and delivered this knowledge to the Army investigation office in July 1943. I would go further and say that his decision to write down his experiences from Operation Longcloth through memoirs such as the one shown on these pages, was his way of ensuring that the men from 1943, whether they were a Captain or simply a Private soldier, were never to be forgotten.

Returning to the story once more, Major Gilkes now prepared the remainder of his Column for their exit out of Burma, a journey through the Yunnan Province of China.

Leslie Cottrell's memoir continues:

The column would be out of the range of aircraft from Agartala and therefore could no longer receive rations and other supplies, many men were by now in poor physical condition and it was doubtful whether they could cover the distances involved, or cross a twelve thousand foot mountain range and the column could still be beaten by the monsoon which was capable of making even the smallest rivers into impassable obstacles. Finally, enemy forces of far superior strength might still be encountered. The council of war weighed all possibilities but remained undecided. After further heart-searching deliberation the decision was taken to head east.

They asked for maps of their anticipated route to be delivered with their last supply drop which they took a few days later. Several of these map sheets were partially blank because they were of areas which had never been mapped, at least not by the British. The column commander decided to cross the Shweli nearer its source where it would be less wide, and so made a big sweep round the loop in the river.

The Kachins (Burma Rifle soldiers) with the column enlisted the support of locals who, on receipt of quite a large sum of money (all officers carried a number of freshly-minted silver rupees) agreed to build rafts and went off to do so, promising to return and guide the column to the crossing place that night. This would be a dangerous operation because the Japanese patrolled the road which ran beside the river in trucks at two-hourly intervals. The time of the rendezvous with the locals approached and passed; the hearts of all members of the column sank. Then suddenly there was a great commotion and the locals arrived, roaring drunk; they had spent their money on rice-wine.

Nevertheless, they kept their word and led the column down to the river by a track as yet unknown, to where well-constructed rafts capable of transporting the whole column and the few remaining mules across the Shweli waited.

There then occurred one of those happenings where fate appeared to be on the side of the British. With scarcely any warning a tropical storm of great intensity broke. The rain was so heavy as to flood completely the road along which the Japanese motorised patrols were expected. No sane person would venture out in such deafening thunder and blinding lightning. But 7 Column saw their chance.

Statement of evidence 24th of July 1943.

Witness. 138760 Capt. L.R. Cottrell.

"I was Staff Officer of number seven Column, during Brigadier Wingate's Burma expedition. On April 10th, 1943 the Column Commander decided for various tactical and administrative reasons to split his column. This was midway between the Mongmit and the Myitson Road.

Lieutenant Walker was ordered to take charge of a party which consisted of three other officers and 25 British Other Ranks. His orders were to march approximately westward re-cross the Irrawaddy and return to Assam by the most direct route. The British Other Ranks were not considered by the Column Commander or by the Medical Officer as physically capable of marching the long way out via China, as the main body intended to do.

They were all equipped with arms and ammunition and had two days hard scale rations each, the officers had maps and compasses. An Air Supply drop was arranged for them just west of the Irrawaddy, but, the party failed to make the rendezvous and the aircraft concerned did not locate them. The Japanese were fairly active in this area. Nothing has been heard of any of these Officers or men since."

Signed Leslie Cottrell, Captain 13th KLR.

Counter-signed H. Cotton, Captain 13 KLR.

It is clear to me that Leslie Cottrell felt a great sense of responsibility to ensure that everything known about the missing and the lost was collated and recorded as early as possible after his return to India. He had written down information about the men from his unit and their last known whereabouts and delivered this knowledge to the Army investigation office in July 1943. I would go further and say that his decision to write down his experiences from Operation Longcloth through memoirs such as the one shown on these pages, was his way of ensuring that the men from 1943, whether they were a Captain or simply a Private soldier, were never to be forgotten.

Returning to the story once more, Major Gilkes now prepared the remainder of his Column for their exit out of Burma, a journey through the Yunnan Province of China.

Leslie Cottrell's memoir continues:

The column would be out of the range of aircraft from Agartala and therefore could no longer receive rations and other supplies, many men were by now in poor physical condition and it was doubtful whether they could cover the distances involved, or cross a twelve thousand foot mountain range and the column could still be beaten by the monsoon which was capable of making even the smallest rivers into impassable obstacles. Finally, enemy forces of far superior strength might still be encountered. The council of war weighed all possibilities but remained undecided. After further heart-searching deliberation the decision was taken to head east.

They asked for maps of their anticipated route to be delivered with their last supply drop which they took a few days later. Several of these map sheets were partially blank because they were of areas which had never been mapped, at least not by the British. The column commander decided to cross the Shweli nearer its source where it would be less wide, and so made a big sweep round the loop in the river.

The Kachins (Burma Rifle soldiers) with the column enlisted the support of locals who, on receipt of quite a large sum of money (all officers carried a number of freshly-minted silver rupees) agreed to build rafts and went off to do so, promising to return and guide the column to the crossing place that night. This would be a dangerous operation because the Japanese patrolled the road which ran beside the river in trucks at two-hourly intervals. The time of the rendezvous with the locals approached and passed; the hearts of all members of the column sank. Then suddenly there was a great commotion and the locals arrived, roaring drunk; they had spent their money on rice-wine.

Nevertheless, they kept their word and led the column down to the river by a track as yet unknown, to where well-constructed rafts capable of transporting the whole column and the few remaining mules across the Shweli waited.

There then occurred one of those happenings where fate appeared to be on the side of the British. With scarcely any warning a tropical storm of great intensity broke. The rain was so heavy as to flood completely the road along which the Japanese motorised patrols were expected. No sane person would venture out in such deafening thunder and blinding lightning. But 7 Column saw their chance.

Captain Cottrell's memoir continues:

Attempting to cross the river under such conditions would be highly risky, but waiting until the storm had abated could mean annihilation by the enemy. They took their chance and all men and animals got safely across and up one of the steepest gradients they had ever encountered so far.

Some days later there occurred another incident to which the reader must be asked to attach the importance he considers its due. In bivouac one evening Major Gilkes asked his Signals Officer if there was any signal from Wingate, as it was the column's listening-in hour. The officer answered no. "Is there nothing you can raise," he asked. After a pause the officer replied, "I have All-India Radio. They appear to be taking a B.B.C. broadcast from London."

"Here, let me listen," said Gilkes.

What the Column Commander heard was part of a religious service being broadcast from St Andrews. The Minister announced the text for his sermon; it was the first verse of Psalm 121, "I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills from whence cometh my strength." Major Gilkes told those about him what he had heard, and to the Administrative Officer who was again writing up the war diary he said, "I know you know the date but do you know it is Easter Sunday." Somehow it seemed that 7 Column should be heading now for the mountains on the Sino-Burmese border.

Major Gilkes and the other officers took this occurrence as a good omen and confirmation of their decision to exit Burma via the hills of Yunnan Province.

Psalm 121:

I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help.

My help cometh from the Lord, which made heaven and earth.

He will not suffer thy foot to be moved: he that keepeth thee will not slumber.

Behold, he that keepeth Israel shall neither slumber nor sleep.

The Lord is thy keeper: the Lord is thy shade upon thy right hand.

The sun shall not smite thee by day, nor the moon by night.

The Lord shall preserve thee from all evil: he shall preserve thy soul.

The Lord shall preserve thy going out and thy coming in from this time forth, and even for evermore.

The column's next dangerous obstacle was the road running from Bhamo to Lashio because it was being used almost constantly by the Japanese. After careful reconnaissance it was decided to cross at midnight and at a point where the gradient up to and from the road was steep.

Column 7's luck held.