Lieutenant James Vernon Crispin Molesworth

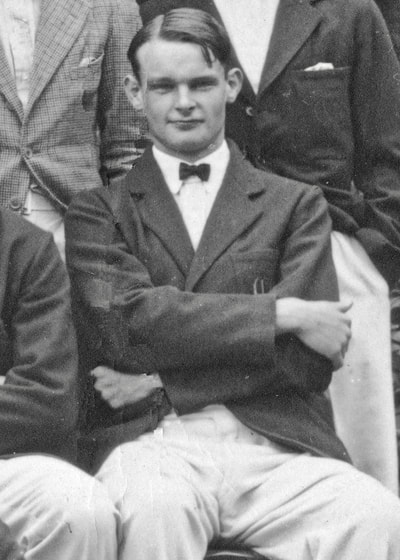

2nd Lt. James Molesworth, India c. 1942.

2nd Lt. James Molesworth, India c. 1942.

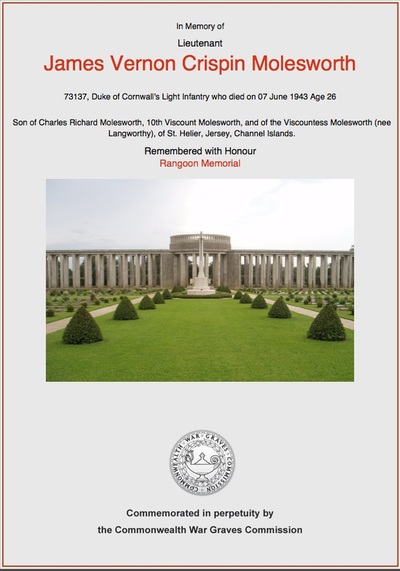

73137 Lieutenant James Vernon Crispin Molesworth was born on the 24th October 1917. He was the son of Charles Richard Molesworth, the 10th Viscount Molesworth, and of the Viscountess Molesworth (nee Langworthy), of St. Helier in Jersey part of the Channel Islands.

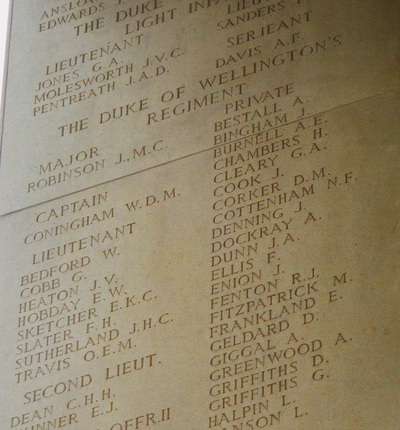

James attended Cheltenham College during the years 1931 through to 1935 and was a student of Hazelwell House. In January 1936 he attained a place at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, completing his studies the following year. On the 26th August 1937 he was commissioned into the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry as a 2nd Lieutenant. In 1939 he temporarily held the post of Adjutant in the Territorial Battalion of the Regiment.

To view Lieutenant Molesworth's CWGC details, please click on the link below: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2517933/MOLESWORTH,%20JAMES%20VERNON%20CRISPIN

At some point during the years of WW2 James must have been posted to a Commando unit, but I cannot find any information about his service from late 1939 up until mid-1942. He was however, definitely sent overseas and by June 1942 found himself attached to the 2nd Battalion the Green Howard's and part of the fledgling 142 Commando, based at Jubbulpore in India. 142 Commando was originally commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel T. Featherstonehaugh of the King's Royal Rifles. Featherstonehaugh had led No. 6 Commando earlier in the war, taking part in various raids against German forces in places such as Norway.

On the 13th July 1942, command of 142 Commando was given over to Major Mike Calvert of the Royal Engineers. The unit was then supplemented by soldiers from the Bush Warfare School based at Maymyo and the 204 Chinese Military Mission. Both these units had experience in Special Forces operations behind enemy lines and had only recently returned from expeditions in Burma and the Yunnan Provinces of China. It was at this time that 142 Commando moved to their new Chindit training camp at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India.

Each Chindit column had a platoon of men from 142 Commando, once behind enemy lines this unit was to be responsible for the planned demolition of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. Lieutenant Molesworth remained with 142 Commando throughout much of the training period at Saugor. However, according to the War diary for the Commando Unit, he suffered some sort of minor injury or wound and was posted across to the main Chindit Brigade Head Quarters on the 11th December 1942.

Now working inside Wingate's own Head Quarters, James took responsibility for the acquisition of all the animals required for the forthcoming operation in Burma. Lieutenant Dominic Neill, then a young and inexperienced Gurkha officer remembered James as being the Senior Animal Transport Officer on Operation Longcloth, organising each columns supply of mules and bullocks. Wingate's Intelligence Officer, Graham Hosegood mentioned James in a letter home to his parents in late 1942; he describes him as an invaluable addition to the unit, but "could be a little grumpy at times."

Sergeant Tony Aubrey of 8 Column remembered Lieutenant Molesworth in the pages of his book, With Wingate in Burma. Aubrey recalled the build up of supplies and pack animals, just before the Chindit Brigade moved off into Burma and were gathering together at Imphal in the state of Assam:

Next day, we reached Imphal, still riding in comfort, thanks to the generosity of our hosts with their transport. In Imphal, we found that one of the officers from our unit had started a bullock farm, and we parked ourselves there to give him a hand while Captain Herring went off to headquarters to make his report.

Mr. Molesworth had come up to Imphal with instructions to get together a herd of some 200 bullocks. He had been a farmer at home, and knew what he was doing. At first he had picked up the animals reasonably cheaply, but when the surrounding zemindars (Indian District landowners) got wise to the fact that he had to have them, up went the price. One or two of them in their earnest desire for profit went so far as to sell their bullocks to Mr. Molesworth, have them stolen back from him and artistically repainted, and then sell them back to him at an increased price, of course, to cover the outlay on paint.

We had some fun with these bullocks. We had to train them to wear a harness, consisting of a sort of horse-cloth with two girths, a tail strap, and saddle bags, and they didn't like it at first. In their desire to get rid of it they went through the most extraordinary gyrations, not at all suited to their bulk and dignity. But after a few days they settled down and gave no more trouble.

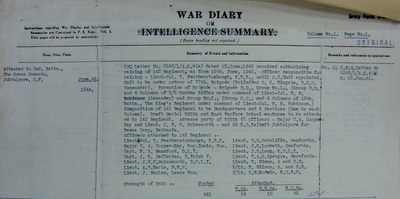

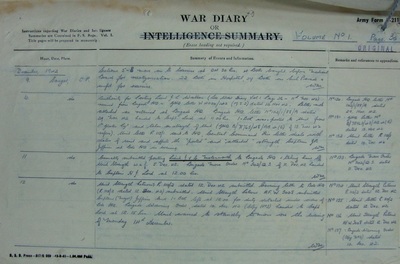

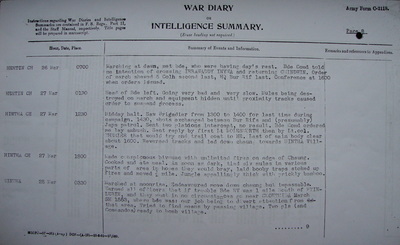

Seen below are some images in relation to this story. These include entries from the 142 Commando War diary, showing Lieutenant Molesworth's part in the raising of the commando unit and his departure to join Wingate's Brigade HQ. Also shown are two other War diary entries; one from the 13th King's battalion diary and one from the daily record of 5 Column. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

James attended Cheltenham College during the years 1931 through to 1935 and was a student of Hazelwell House. In January 1936 he attained a place at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, completing his studies the following year. On the 26th August 1937 he was commissioned into the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry as a 2nd Lieutenant. In 1939 he temporarily held the post of Adjutant in the Territorial Battalion of the Regiment.

To view Lieutenant Molesworth's CWGC details, please click on the link below: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2517933/MOLESWORTH,%20JAMES%20VERNON%20CRISPIN

At some point during the years of WW2 James must have been posted to a Commando unit, but I cannot find any information about his service from late 1939 up until mid-1942. He was however, definitely sent overseas and by June 1942 found himself attached to the 2nd Battalion the Green Howard's and part of the fledgling 142 Commando, based at Jubbulpore in India. 142 Commando was originally commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel T. Featherstonehaugh of the King's Royal Rifles. Featherstonehaugh had led No. 6 Commando earlier in the war, taking part in various raids against German forces in places such as Norway.

On the 13th July 1942, command of 142 Commando was given over to Major Mike Calvert of the Royal Engineers. The unit was then supplemented by soldiers from the Bush Warfare School based at Maymyo and the 204 Chinese Military Mission. Both these units had experience in Special Forces operations behind enemy lines and had only recently returned from expeditions in Burma and the Yunnan Provinces of China. It was at this time that 142 Commando moved to their new Chindit training camp at Saugor in the Central Provinces of India.

Each Chindit column had a platoon of men from 142 Commando, once behind enemy lines this unit was to be responsible for the planned demolition of the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. Lieutenant Molesworth remained with 142 Commando throughout much of the training period at Saugor. However, according to the War diary for the Commando Unit, he suffered some sort of minor injury or wound and was posted across to the main Chindit Brigade Head Quarters on the 11th December 1942.

Now working inside Wingate's own Head Quarters, James took responsibility for the acquisition of all the animals required for the forthcoming operation in Burma. Lieutenant Dominic Neill, then a young and inexperienced Gurkha officer remembered James as being the Senior Animal Transport Officer on Operation Longcloth, organising each columns supply of mules and bullocks. Wingate's Intelligence Officer, Graham Hosegood mentioned James in a letter home to his parents in late 1942; he describes him as an invaluable addition to the unit, but "could be a little grumpy at times."

Sergeant Tony Aubrey of 8 Column remembered Lieutenant Molesworth in the pages of his book, With Wingate in Burma. Aubrey recalled the build up of supplies and pack animals, just before the Chindit Brigade moved off into Burma and were gathering together at Imphal in the state of Assam:

Next day, we reached Imphal, still riding in comfort, thanks to the generosity of our hosts with their transport. In Imphal, we found that one of the officers from our unit had started a bullock farm, and we parked ourselves there to give him a hand while Captain Herring went off to headquarters to make his report.

Mr. Molesworth had come up to Imphal with instructions to get together a herd of some 200 bullocks. He had been a farmer at home, and knew what he was doing. At first he had picked up the animals reasonably cheaply, but when the surrounding zemindars (Indian District landowners) got wise to the fact that he had to have them, up went the price. One or two of them in their earnest desire for profit went so far as to sell their bullocks to Mr. Molesworth, have them stolen back from him and artistically repainted, and then sell them back to him at an increased price, of course, to cover the outlay on paint.

We had some fun with these bullocks. We had to train them to wear a harness, consisting of a sort of horse-cloth with two girths, a tail strap, and saddle bags, and they didn't like it at first. In their desire to get rid of it they went through the most extraordinary gyrations, not at all suited to their bulk and dignity. But after a few days they settled down and gave no more trouble.

Seen below are some images in relation to this story. These include entries from the 142 Commando War diary, showing Lieutenant Molesworth's part in the raising of the commando unit and his departure to join Wingate's Brigade HQ. Also shown are two other War diary entries; one from the 13th King's battalion diary and one from the daily record of 5 Column. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Once inside Burma, James Molesworth travelled alongside Brigadier Wingate in his Head Quarters. Presumably his duties in relation to the bullocks and mules became less and less arduous as the operation progressed, especially when you consider that most of the bullocks were only needed in the first few weeks to transport the larger equipment and that many of these were eaten by the Chindits as subsidy to their standard rations.

By March 1943, James was used as a liaison officer, often moving between columns and delivering Wingate's latest orders. This sounds quite straight forward, but in reality it often meant travelling alone or perhaps accompanied by another officer through the dense jungle trails and scrubland. A good understanding of both maps and compass was essential as even when a destination was just a few miles away, rarely could you travel as the crow flies and using well worn tracks was to be avoided.

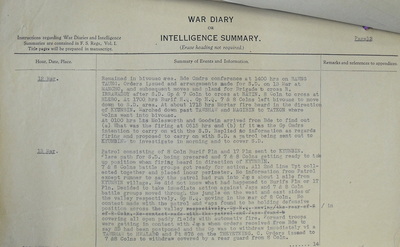

On the 27th March James Molesworth was the last officer to liaise with 5 Column (see diary page in the above gallery) before the Chindit Brigade was ordered to return to India. He had relayed Wingate's orders to Major Fergusson and was asked to return with the information that 5 Column were about to set a false trail for the Japanese to follow, leading the enemy away from the main body of troops and allowing them to march west toward the Irrawaddy River unmolested.

Returning to Brigade Head Quarters, James was just in time to join the Brigadier and Columns 7 and 8 as they marched to the Irrawaddy, reaching the river close to the village of Inywa. They began to cross on the 29th March, but their progress was blocked by a Japanese patrol on the western banks and the crossing had to be abandoned. Brigadier Wingate called an emergency meeting with his Column commanders and it was decided that the Chindit units would separate and attempt to make their own way back to India. Wingate withdrew with his HQ into the thickset bamboo jungle nearby and remained in this location for the best part of a week.

After this time Wingate ordered the last of the mules to be slaughtered and all heavy equipment to be destroyed, he then divided his own Brigade Headquarters into five dispersal parties: his own party consisting of the Commandos, some RAF personnel and Lt. Spurlock; a party of Gurkhas, mostly muleteers, under Major Conron; a party of Burma Rifles from the propaganda section and some Gurkha muleteers under Lt. Molesworth; a party of British Other Ranks under Major Ramsay (the senior Medical Officer) and Captain Moxham; and a party of British Other Ranks under Captain Hosegood and Lt. Wilding.

Wilding's party was about thirty strong. He recalled:

"We were instructed to go north, cross the Shweli River swing west and go home, a distance of some 200 miles. First of all we received an enormous supply drop by the RAF. This included some rum and some chocolate bars, a gift from the RAF station, bless them. Although James was in good company, in regards to the Burma Rifles contingent of his dispersal party, the group soon ran into difficulties."

Nothing has been written or is known about the following few weeks, but at some point, probably in late April, James Molesworth became a prisoner of war. I can only surmise that his party were still travelling together as one group when they were captured by the Japanese or possibly by some of the Burma Independence Army working for the enemy at that time. The prisoners were taken to the town of Maymyo, where a large civil concentration camp already existed, during the months of April and May 1943 over 200 ailing Chindits were collected together and imprisoned at Maymyo.

Conditions in the camp were appalling and it was at Maymyo that the Chindits were taught Japanese drill and behaviour, including answering all commands in Japanese and bowing to all Japanese soldiers and officials every time they encountered them. Sadly, it was whilst at Maymyo that James Molesworth died. His recorded date of death is the 7th June 1943. Lieutenant Ted Horton, another Chindit POW held at the camp gave a statement which stated that James Molesworth had perished at Maymyo and that his body had been cremated there. This statement forms part of a group of papers about Chindit prisoners of war and can be found at the Imperial War Museum in London.

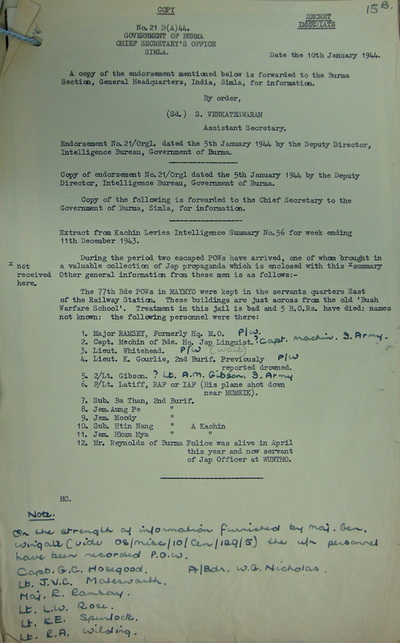

The only piece of documentary evidence that Lieutenant Molesworth did fall into Japanese hands in 1943 can be seen in the gallery below. It is a secret report given by two escapees from Maymyo, who disclosed the poor treatment and conditions experienced in the camp and named some of the Chindit personnel present. It is purely conjecture on my part, but, the very fact that Lieutenant Molesworth's body was reportedly cremated, makes me believe that he may have perished whilst suffering from one of the more contagious tropical diseases. The most common diseases suffered by the Chindits as prisoners of war were malaria, dysentery and beri beri, none of these afflictions would normally result in a casualty being cremated.

To read more about the POW camp at Maymyo and the Chindt soldier's experiences there, please click on the following link:

The Maymyo Camp

Seen below are some more images in relation to this story. These include some of the places where James Molesworth is remembered with honour for his valiant contribution to the Allied cause during the years of WW2. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

By March 1943, James was used as a liaison officer, often moving between columns and delivering Wingate's latest orders. This sounds quite straight forward, but in reality it often meant travelling alone or perhaps accompanied by another officer through the dense jungle trails and scrubland. A good understanding of both maps and compass was essential as even when a destination was just a few miles away, rarely could you travel as the crow flies and using well worn tracks was to be avoided.

On the 27th March James Molesworth was the last officer to liaise with 5 Column (see diary page in the above gallery) before the Chindit Brigade was ordered to return to India. He had relayed Wingate's orders to Major Fergusson and was asked to return with the information that 5 Column were about to set a false trail for the Japanese to follow, leading the enemy away from the main body of troops and allowing them to march west toward the Irrawaddy River unmolested.

Returning to Brigade Head Quarters, James was just in time to join the Brigadier and Columns 7 and 8 as they marched to the Irrawaddy, reaching the river close to the village of Inywa. They began to cross on the 29th March, but their progress was blocked by a Japanese patrol on the western banks and the crossing had to be abandoned. Brigadier Wingate called an emergency meeting with his Column commanders and it was decided that the Chindit units would separate and attempt to make their own way back to India. Wingate withdrew with his HQ into the thickset bamboo jungle nearby and remained in this location for the best part of a week.

After this time Wingate ordered the last of the mules to be slaughtered and all heavy equipment to be destroyed, he then divided his own Brigade Headquarters into five dispersal parties: his own party consisting of the Commandos, some RAF personnel and Lt. Spurlock; a party of Gurkhas, mostly muleteers, under Major Conron; a party of Burma Rifles from the propaganda section and some Gurkha muleteers under Lt. Molesworth; a party of British Other Ranks under Major Ramsay (the senior Medical Officer) and Captain Moxham; and a party of British Other Ranks under Captain Hosegood and Lt. Wilding.

Wilding's party was about thirty strong. He recalled:

"We were instructed to go north, cross the Shweli River swing west and go home, a distance of some 200 miles. First of all we received an enormous supply drop by the RAF. This included some rum and some chocolate bars, a gift from the RAF station, bless them. Although James was in good company, in regards to the Burma Rifles contingent of his dispersal party, the group soon ran into difficulties."

Nothing has been written or is known about the following few weeks, but at some point, probably in late April, James Molesworth became a prisoner of war. I can only surmise that his party were still travelling together as one group when they were captured by the Japanese or possibly by some of the Burma Independence Army working for the enemy at that time. The prisoners were taken to the town of Maymyo, where a large civil concentration camp already existed, during the months of April and May 1943 over 200 ailing Chindits were collected together and imprisoned at Maymyo.

Conditions in the camp were appalling and it was at Maymyo that the Chindits were taught Japanese drill and behaviour, including answering all commands in Japanese and bowing to all Japanese soldiers and officials every time they encountered them. Sadly, it was whilst at Maymyo that James Molesworth died. His recorded date of death is the 7th June 1943. Lieutenant Ted Horton, another Chindit POW held at the camp gave a statement which stated that James Molesworth had perished at Maymyo and that his body had been cremated there. This statement forms part of a group of papers about Chindit prisoners of war and can be found at the Imperial War Museum in London.

The only piece of documentary evidence that Lieutenant Molesworth did fall into Japanese hands in 1943 can be seen in the gallery below. It is a secret report given by two escapees from Maymyo, who disclosed the poor treatment and conditions experienced in the camp and named some of the Chindit personnel present. It is purely conjecture on my part, but, the very fact that Lieutenant Molesworth's body was reportedly cremated, makes me believe that he may have perished whilst suffering from one of the more contagious tropical diseases. The most common diseases suffered by the Chindits as prisoners of war were malaria, dysentery and beri beri, none of these afflictions would normally result in a casualty being cremated.

To read more about the POW camp at Maymyo and the Chindt soldier's experiences there, please click on the following link:

The Maymyo Camp

Seen below are some more images in relation to this story. These include some of the places where James Molesworth is remembered with honour for his valiant contribution to the Allied cause during the years of WW2. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After the war was over, the Imperial War Graves Commission attempted to locate as many graves and final resting places for casualties of the Burma Campaign as they possibly could. Many of these burials were eventually taken down to the newly built war cemeteries at Rangoon and Taukkyan. To my knowledge, none of the Chindits who perished at Maymyo have an individual grave in either of these two locations and all are remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial, the centre piece structure of Taukkyan War Cemetery. This memorial was constructed to record the 27,000 plus casualties from the Burma campaign who have no known grave.

Lieutenant James Molesworth was promoted to Captain in his absence on the 26th August 1945, exactly eight years after he received his first Army commission. He was promoted pending information of his actual fate as a prisoner of war in WW2. Information about his demise in June 1943 would not have been available or confirmed until after the surviving prisoners of war from the first Chindit operation were liberated from Rangoon Jail in May 1945 and had been debriefed by the Army Investigation Bureau. Perhaps this is when Lieutenant Ted Horton gave his information and witness statement concerning James to the authorities.

Update 15/04/2015.

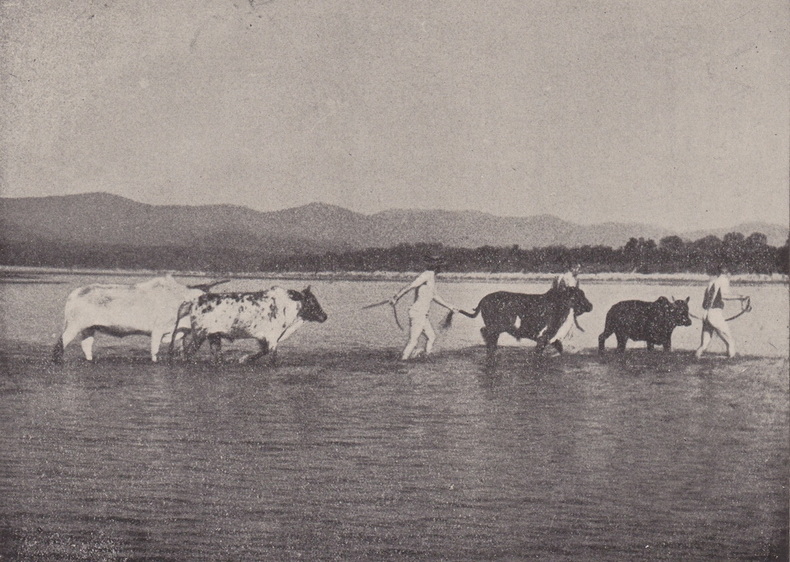

Seen below is an image of the bullock handlers from Chindit Column 5 driving their animals across the Chindwin River in February 1943. Perhaps these animals were part of the herd comprised by Lieutenant Molesworth at Imphal.

Lieutenant James Molesworth was promoted to Captain in his absence on the 26th August 1945, exactly eight years after he received his first Army commission. He was promoted pending information of his actual fate as a prisoner of war in WW2. Information about his demise in June 1943 would not have been available or confirmed until after the surviving prisoners of war from the first Chindit operation were liberated from Rangoon Jail in May 1945 and had been debriefed by the Army Investigation Bureau. Perhaps this is when Lieutenant Ted Horton gave his information and witness statement concerning James to the authorities.

Update 15/04/2015.

Seen below is an image of the bullock handlers from Chindit Column 5 driving their animals across the Chindwin River in February 1943. Perhaps these animals were part of the herd comprised by Lieutenant Molesworth at Imphal.

Update 06/06/2015.

I was delighted to receive this email enquiry from Louise Mann, a historical researcher for the villages of Levington and Stratton Hall in Suffolk.

Dear Steve,

I am the Village Recorder for Levington and Stratton Hall in Suffolk, and whilst carrying out some research into the Chindits, came across your website. I am currently assisting with putting together an annual display marking an aspect relating to Remembrance Sunday. This year, the theme is the war in the Far East.

One of the men named on the Levington war memorial is James Molesworth, and I was very interested to read your extensive article about him. The previous Village Recorder had carried out some research into him, as part of a booklet about those commemorated on the war memorial. The information you have found out will add much detail to that which we already have. I also have a request to make; would it be possible for me to use your article as part of the aforementioned display, with a view to keeping it in the village archive which I look after. Obviously, you will get full credit for it being your research.

You might like to have the following information about James Vernon Crispin Molesworth for your own records:

Excerpt from “History of Levington War Memorial 1920-2009." Produced by Derek Girling for the Levington Local History Club in 2009.

The family (Molesworth) had a strong connection with Levington. They lived for some years in Broke House. During this time, Charles Molesworth was the Estate Agent for Lord de Saumarez and also church warden at St. Peter’s Church. In fact, to commemorate his time as churchwarden from 1920-1934, he presented the church with a large black Bible which is kept on a small table in the chancel or on the lectern to this day. Before WWII started the family moved away. After their son’s untimely death, Viscount and Viscountess Molesworth requested that James’s name be put on Levington’s War Memorial.

Other details which may be of interest:

The de Saumarez family originate from Guernsey. The shared Channel Islands heritage suggests that this is how the de Saumarez and Molesworth families became involved. James St. Vincent Saumarez, 4th Baron de Saumarez married Jane Anne Vere-Broke in 1882. Broke Hall is located in Nacton, the adjacent village and parish to Levington. Broke House (possibly known in the past as Broke Farm) was part of the Broke estate, and is situated in Levington. The Levington War Memorial is located in the grounds of St. Peter’s Church, which is about two minutes walk from Broke House.

My thanks go to Louise Mann for this fascinating insight into the genealogy of James Molesworth and the history of Levington and surrounding areas. Seen below is a map showing the location of Levington and some of the other place names mentioned in the preceding text. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

I was delighted to receive this email enquiry from Louise Mann, a historical researcher for the villages of Levington and Stratton Hall in Suffolk.

Dear Steve,

I am the Village Recorder for Levington and Stratton Hall in Suffolk, and whilst carrying out some research into the Chindits, came across your website. I am currently assisting with putting together an annual display marking an aspect relating to Remembrance Sunday. This year, the theme is the war in the Far East.

One of the men named on the Levington war memorial is James Molesworth, and I was very interested to read your extensive article about him. The previous Village Recorder had carried out some research into him, as part of a booklet about those commemorated on the war memorial. The information you have found out will add much detail to that which we already have. I also have a request to make; would it be possible for me to use your article as part of the aforementioned display, with a view to keeping it in the village archive which I look after. Obviously, you will get full credit for it being your research.

You might like to have the following information about James Vernon Crispin Molesworth for your own records:

Excerpt from “History of Levington War Memorial 1920-2009." Produced by Derek Girling for the Levington Local History Club in 2009.

The family (Molesworth) had a strong connection with Levington. They lived for some years in Broke House. During this time, Charles Molesworth was the Estate Agent for Lord de Saumarez and also church warden at St. Peter’s Church. In fact, to commemorate his time as churchwarden from 1920-1934, he presented the church with a large black Bible which is kept on a small table in the chancel or on the lectern to this day. Before WWII started the family moved away. After their son’s untimely death, Viscount and Viscountess Molesworth requested that James’s name be put on Levington’s War Memorial.

Other details which may be of interest:

The de Saumarez family originate from Guernsey. The shared Channel Islands heritage suggests that this is how the de Saumarez and Molesworth families became involved. James St. Vincent Saumarez, 4th Baron de Saumarez married Jane Anne Vere-Broke in 1882. Broke Hall is located in Nacton, the adjacent village and parish to Levington. Broke House (possibly known in the past as Broke Farm) was part of the Broke estate, and is situated in Levington. The Levington War Memorial is located in the grounds of St. Peter’s Church, which is about two minutes walk from Broke House.

My thanks go to Louise Mann for this fascinating insight into the genealogy of James Molesworth and the history of Levington and surrounding areas. Seen below is a map showing the location of Levington and some of the other place names mentioned in the preceding text. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 09/04/2016.

In late August 2015, I received an email contact from William Molesworth, a nephew of Lieutenant James Molesworth:

Dear Steve,

A few years ago I came across Derek Girling's article on Lt. James Molesworth, and just recently your excellent website. Jim, as he was always known to family and friends, was in fact the younger son of Charles Richard, 10th Viscount Molesworth. His (Jim's) elder brother was the late Richard Gosset, 11th Viscount Molesworth. My brother, Robert and I are Richard's sons. Hence Jim was our uncle, although as we were born long after the war, our knowledge of him came mainly via our father, who was so deeply aggrieved by the loss of his brother that he spoke very little about early family life.

In recent years, however, we have managed to uncover a few more details about Uncle Jim from family records and personal reminiscences from school contemporaries while they were still living. We also have several photos, some from Cheltenham College, which my brother and I later attended. We would be more than happy to contribute to your records, and to Louise Mann's planned commemorative display, as well as the Remembrance Service on the 8th November (2015) at Levington. How fortunate to have stumbled upon all this in good time.

With all best wishes,

William Molesworth

Through our continued correspondence, William and I were able to exchange much more information about James, from his school days, right up until his sad and untimely demise as a prisoner of war in Burma. William is preparing an article about his uncle for the Floreat, the magazine of Cheltenham College and hopes for this to be published in the 2017 issue, this being the centenary of James' birth.

One fresh piece of information that our email conversations did manage to uncover, was Jim's service with No. 3 Commando during the early years of WW2. This was discovered when I stumbled across his name within the nominal rolls for the Regiment on the Commando Veterans Archive website. I have not had time to examine the war diaries for No. 3 Commando at the National Archives, but it seems likely that Lieutenant Molesworth would have participated in the raids on the Lofoten Islands and Vaagso in 1941.

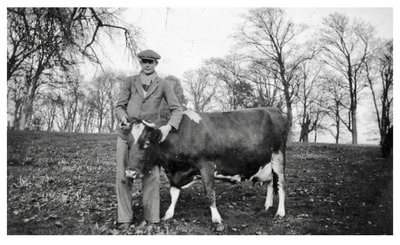

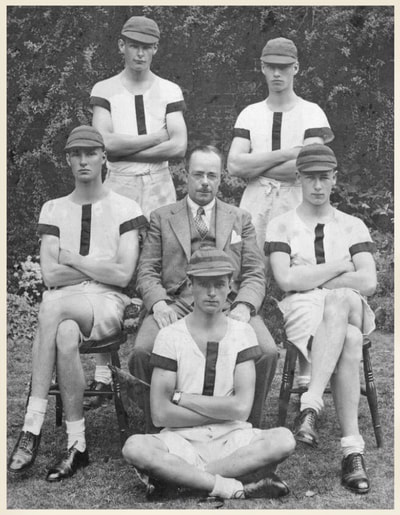

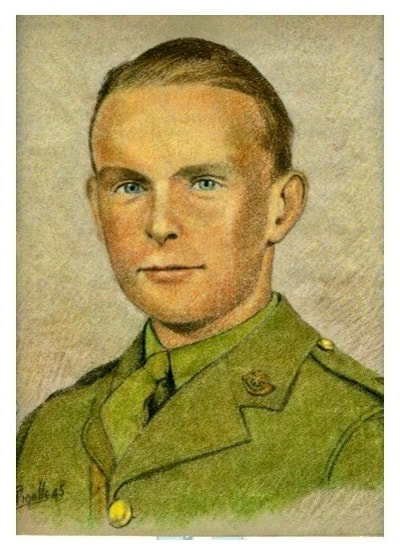

William has shared a number of photographs with me depicting James' early life, one of which is shown below. I hope to include more of these images on these pages, but will wait until William's full article in honour of his uncle has been published in the Floreat magazine.

In late August 2015, I received an email contact from William Molesworth, a nephew of Lieutenant James Molesworth:

Dear Steve,

A few years ago I came across Derek Girling's article on Lt. James Molesworth, and just recently your excellent website. Jim, as he was always known to family and friends, was in fact the younger son of Charles Richard, 10th Viscount Molesworth. His (Jim's) elder brother was the late Richard Gosset, 11th Viscount Molesworth. My brother, Robert and I are Richard's sons. Hence Jim was our uncle, although as we were born long after the war, our knowledge of him came mainly via our father, who was so deeply aggrieved by the loss of his brother that he spoke very little about early family life.

In recent years, however, we have managed to uncover a few more details about Uncle Jim from family records and personal reminiscences from school contemporaries while they were still living. We also have several photos, some from Cheltenham College, which my brother and I later attended. We would be more than happy to contribute to your records, and to Louise Mann's planned commemorative display, as well as the Remembrance Service on the 8th November (2015) at Levington. How fortunate to have stumbled upon all this in good time.

With all best wishes,

William Molesworth

Through our continued correspondence, William and I were able to exchange much more information about James, from his school days, right up until his sad and untimely demise as a prisoner of war in Burma. William is preparing an article about his uncle for the Floreat, the magazine of Cheltenham College and hopes for this to be published in the 2017 issue, this being the centenary of James' birth.

One fresh piece of information that our email conversations did manage to uncover, was Jim's service with No. 3 Commando during the early years of WW2. This was discovered when I stumbled across his name within the nominal rolls for the Regiment on the Commando Veterans Archive website. I have not had time to examine the war diaries for No. 3 Commando at the National Archives, but it seems likely that Lieutenant Molesworth would have participated in the raids on the Lofoten Islands and Vaagso in 1941.

William has shared a number of photographs with me depicting James' early life, one of which is shown below. I hope to include more of these images on these pages, but will wait until William's full article in honour of his uncle has been published in the Floreat magazine.

Update 18/09/2017.

I am now pleased to include William Molesworth's article which was published in the Floreat magazine in January this year. To view and read the entire magazine, please click on the following link: issuu.com/cheltenhamcollege/docs/floreat-2017-forweb

Here is William's article in full with some additional photographs shown in the gallery below:

Cheltonian, Commando and Chindit: Lt. James Molesworth (Hazelwell House, 1935)

William Molesworth (H, 1978) pays tribute to his uncle, James Vernon Crispin Molesworth, whose death as a POW in Burma in 1943 at the age of 26 is a reminder of the sacrifice made by the many young OC's of his generation.

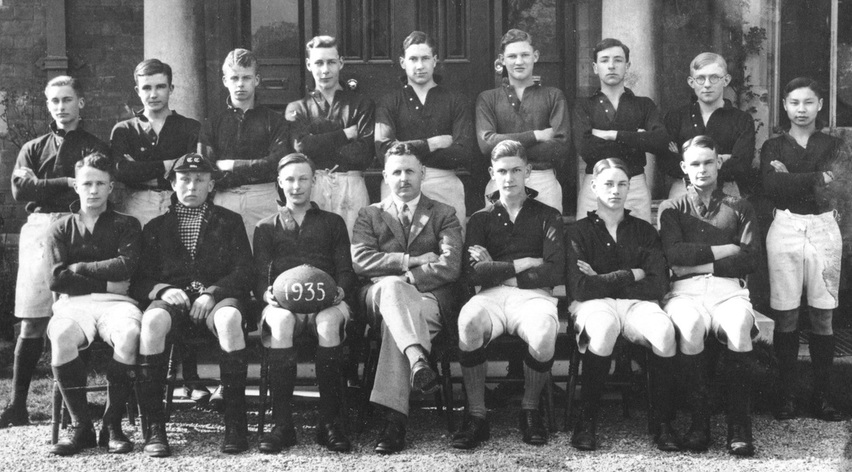

Born 100 years ago, Uncle Jim was the third generation of my family to attend College, following his father, Charles, 10th Viscount Molesworth (H, 1891) and grandfather, Samuel, 8th Viscount Molesworth (First Hall, 1849), the latter a Founder Pupil. After a troubled first term, when he is said to have run away to Dowdesell Reservoir, Jim earned kudos through his prowess at football (1935 XV), rowing and boxing. His time at Hazelwell coincided with the redoubtable John Cedric Gurney (1927-43), whose disdain of boys too young to have fought in the Great War may have prejudiced their relationship, although perhaps the reason partly lay in Jim’s penchant for long bicycle rides with a friend to nearby country pubs!

After Sandhurst in 1937, he joined the 2nd Battalion, The Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, which in its prenatal existence as the 46th Foot had been the family regiment since the eighteenth century. The pre-war years were good times for a young officer like Jim, with plenty of riding, hunt balls and a King’s Levée. With war declared in September 1939, he did not go with his battalion as part of the initial British Expeditionary Force that immediately crossed to France, only going over in the second wave of March 1940. Since little had happened during the Phoney War, however, he was still in time to take part in major actions along the Rivers Dyle and Escaut, as well as the final defensive position around Dunkirk, until evacuated in early June 1940.

The following month Jim volunteered for Special Service with the newly-formed No. 3 Commando, one of the first units to be so named. Training in utmost secrecy at the Combined Training Centre at Inverary, his posting came through by the end of the year, so that he was able to go on the large-scale raid on the Lofoten Islands in Norway in March 1941 (Operation Claymore), when vital components of a German Enigma machine were captured, which eventually led to the cracking of the German code. A return visit at the end of 1941 saw further raids carried out on the island of Vågsøy and port of Måløy (Operation Archery), which involved fierce street fighting.

In March 1942 Jim transferred to 142 Commando in India under Major ‘Mad Mike’ Calvert. The latter worked closely with the eccentric Brigadier Orde Wingate as part of the Special Forces element of the legendary Chindits, the pioneers of Long Range Penetration in the jungle. Wingate built up his men, officers included, with gruelling route marches in the unforgiving environment of the Indian jungle, during which there were several casualties to malaria and drowning. The justification for such hazardous training was Operation Longcloth, launched in February 1943, when some 3,200 men crossed into Japanese-held Burma. Their objective was to create havoc in the enemy’s back yard by disrupting his lines of communication and supply, particularly railways, bridges and ammunition depots, as well as harassing the enemy when opportunity arose. Divided into eight columns of 400 men, each column was to be capable of acting independently by weekly supply drops from the air, a novel concept in warfare.

Some 1,100 mules, nevertheless, were necessary for transporting the heavy weapons, ammunition, bulky radios and medical supplies, also 200 bullocks, 50 dogs of various breeds, and an assortment of horses and elephants. Since his father had bred Channel Island cattle, Jim was placed in overall charge of this Hannibalic assemblage, the likes of which had probably not gone into action with the British Army before, nor, one imagines, are ever likely to!

With the advantage of surprise, the Chindits at first carried out their acts of sabotage and ambush with little loss. Spurred on by early success, Wingate ordered the Brigade deeper into enemy territory. The initial response of the Japanese had been to cut off their road routes, but once they realised they were being supplied by air, they became adept at intercepting these. Inevitably this led to animals being slaughtered for food. Others were put down from injury and sickness, or else freed once beyond serviceable use. Jim’s role as chief muleteer thus lessened to the extent that by March he had become one of Wingate’s liaison officers, running between columns to deliver latest orders and report back. This entailed hazardous treks through dense jungle trails and scrubland, for which good orientation was essential, as even when a destination was only a few miles away, rarely could one travel as the crow flies and using well worn tracks was to be avoided.

By this time the Chindits were fighting off more and more Japanese, who were now fully mobilised. The enemy was able to use tanks on the jungle tracks, a threat the Chindits were unable to answer. Besides injury from contact, there were the ever-present risks of louse and disease. Those unable to keep up were simply left behind, although it was sometimes possible to leave them with friendly villagers. Rather than face capture or a lone death, some men requested a coup de grace – an overdose of morphia was the kindest option – or else took their own life.

By now, late March, the Chindits had been operational more than six weeks. Most were exhausted, many diseased or suffering hunger and dehydration. They were some 500 miles inside enemy territory, heavily outnumbered and on the wrong side of the Irrawaddy River, which was 3/4 mile wide in places. With little further that could be achieved, Wingate was ordered to pull out. After an attempted re-crossing of the Irrawaddy was stopped by a Japanese patrol on the far bank, he divided his men into small dispersal groups to make their own way back to India. With the offensive role over, the priority was now speed and evasion. They thus stripped down their arms, discarded heavy equipment and abandoned or ate the remaining animals. Jim was given a party of the highly regarded Burma Rifles and Gurkhas, but these soon ran into difficulties. For many Chindits would become trapped within the pocket of land at the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers, and Jim’s group seems to have been among those compromised. Still fit at time of capture, he later contracted dysentery, was transferred to a prison hospital, but succumbed to his illness in June 1943.

The rights and wrongs of Longcloth are still hotly debated. Although valuable propaganda at the time, it achieved little tactically, while those rendered hors de combat, whether through injury, disease, imprisonment or death, may have been as high as 80% of the Brigade. Ultimately, any assessment must take account of the controversial figure of Wingate himself, who has been variously hailed as military genius who paved the way for all future jungle operations, or dangerous maverick with profligate disregard for men and resources. Perhaps he was a little of both. What is agreed by all those who served under him is that he was an inspirational leader of men. For him they pushed themselves to the limit: my uncle was one of them.

I am now pleased to include William Molesworth's article which was published in the Floreat magazine in January this year. To view and read the entire magazine, please click on the following link: issuu.com/cheltenhamcollege/docs/floreat-2017-forweb

Here is William's article in full with some additional photographs shown in the gallery below:

Cheltonian, Commando and Chindit: Lt. James Molesworth (Hazelwell House, 1935)

William Molesworth (H, 1978) pays tribute to his uncle, James Vernon Crispin Molesworth, whose death as a POW in Burma in 1943 at the age of 26 is a reminder of the sacrifice made by the many young OC's of his generation.

Born 100 years ago, Uncle Jim was the third generation of my family to attend College, following his father, Charles, 10th Viscount Molesworth (H, 1891) and grandfather, Samuel, 8th Viscount Molesworth (First Hall, 1849), the latter a Founder Pupil. After a troubled first term, when he is said to have run away to Dowdesell Reservoir, Jim earned kudos through his prowess at football (1935 XV), rowing and boxing. His time at Hazelwell coincided with the redoubtable John Cedric Gurney (1927-43), whose disdain of boys too young to have fought in the Great War may have prejudiced their relationship, although perhaps the reason partly lay in Jim’s penchant for long bicycle rides with a friend to nearby country pubs!

After Sandhurst in 1937, he joined the 2nd Battalion, The Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, which in its prenatal existence as the 46th Foot had been the family regiment since the eighteenth century. The pre-war years were good times for a young officer like Jim, with plenty of riding, hunt balls and a King’s Levée. With war declared in September 1939, he did not go with his battalion as part of the initial British Expeditionary Force that immediately crossed to France, only going over in the second wave of March 1940. Since little had happened during the Phoney War, however, he was still in time to take part in major actions along the Rivers Dyle and Escaut, as well as the final defensive position around Dunkirk, until evacuated in early June 1940.

The following month Jim volunteered for Special Service with the newly-formed No. 3 Commando, one of the first units to be so named. Training in utmost secrecy at the Combined Training Centre at Inverary, his posting came through by the end of the year, so that he was able to go on the large-scale raid on the Lofoten Islands in Norway in March 1941 (Operation Claymore), when vital components of a German Enigma machine were captured, which eventually led to the cracking of the German code. A return visit at the end of 1941 saw further raids carried out on the island of Vågsøy and port of Måløy (Operation Archery), which involved fierce street fighting.

In March 1942 Jim transferred to 142 Commando in India under Major ‘Mad Mike’ Calvert. The latter worked closely with the eccentric Brigadier Orde Wingate as part of the Special Forces element of the legendary Chindits, the pioneers of Long Range Penetration in the jungle. Wingate built up his men, officers included, with gruelling route marches in the unforgiving environment of the Indian jungle, during which there were several casualties to malaria and drowning. The justification for such hazardous training was Operation Longcloth, launched in February 1943, when some 3,200 men crossed into Japanese-held Burma. Their objective was to create havoc in the enemy’s back yard by disrupting his lines of communication and supply, particularly railways, bridges and ammunition depots, as well as harassing the enemy when opportunity arose. Divided into eight columns of 400 men, each column was to be capable of acting independently by weekly supply drops from the air, a novel concept in warfare.

Some 1,100 mules, nevertheless, were necessary for transporting the heavy weapons, ammunition, bulky radios and medical supplies, also 200 bullocks, 50 dogs of various breeds, and an assortment of horses and elephants. Since his father had bred Channel Island cattle, Jim was placed in overall charge of this Hannibalic assemblage, the likes of which had probably not gone into action with the British Army before, nor, one imagines, are ever likely to!

With the advantage of surprise, the Chindits at first carried out their acts of sabotage and ambush with little loss. Spurred on by early success, Wingate ordered the Brigade deeper into enemy territory. The initial response of the Japanese had been to cut off their road routes, but once they realised they were being supplied by air, they became adept at intercepting these. Inevitably this led to animals being slaughtered for food. Others were put down from injury and sickness, or else freed once beyond serviceable use. Jim’s role as chief muleteer thus lessened to the extent that by March he had become one of Wingate’s liaison officers, running between columns to deliver latest orders and report back. This entailed hazardous treks through dense jungle trails and scrubland, for which good orientation was essential, as even when a destination was only a few miles away, rarely could one travel as the crow flies and using well worn tracks was to be avoided.

By this time the Chindits were fighting off more and more Japanese, who were now fully mobilised. The enemy was able to use tanks on the jungle tracks, a threat the Chindits were unable to answer. Besides injury from contact, there were the ever-present risks of louse and disease. Those unable to keep up were simply left behind, although it was sometimes possible to leave them with friendly villagers. Rather than face capture or a lone death, some men requested a coup de grace – an overdose of morphia was the kindest option – or else took their own life.

By now, late March, the Chindits had been operational more than six weeks. Most were exhausted, many diseased or suffering hunger and dehydration. They were some 500 miles inside enemy territory, heavily outnumbered and on the wrong side of the Irrawaddy River, which was 3/4 mile wide in places. With little further that could be achieved, Wingate was ordered to pull out. After an attempted re-crossing of the Irrawaddy was stopped by a Japanese patrol on the far bank, he divided his men into small dispersal groups to make their own way back to India. With the offensive role over, the priority was now speed and evasion. They thus stripped down their arms, discarded heavy equipment and abandoned or ate the remaining animals. Jim was given a party of the highly regarded Burma Rifles and Gurkhas, but these soon ran into difficulties. For many Chindits would become trapped within the pocket of land at the confluence of the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers, and Jim’s group seems to have been among those compromised. Still fit at time of capture, he later contracted dysentery, was transferred to a prison hospital, but succumbed to his illness in June 1943.

The rights and wrongs of Longcloth are still hotly debated. Although valuable propaganda at the time, it achieved little tactically, while those rendered hors de combat, whether through injury, disease, imprisonment or death, may have been as high as 80% of the Brigade. Ultimately, any assessment must take account of the controversial figure of Wingate himself, who has been variously hailed as military genius who paved the way for all future jungle operations, or dangerous maverick with profligate disregard for men and resources. Perhaps he was a little of both. What is agreed by all those who served under him is that he was an inspirational leader of men. For him they pushed themselves to the limit: my uncle was one of them.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and William Molesworth, March 2015.