Lieutenant P.A.M. Heald, 2nd Burma Rifles

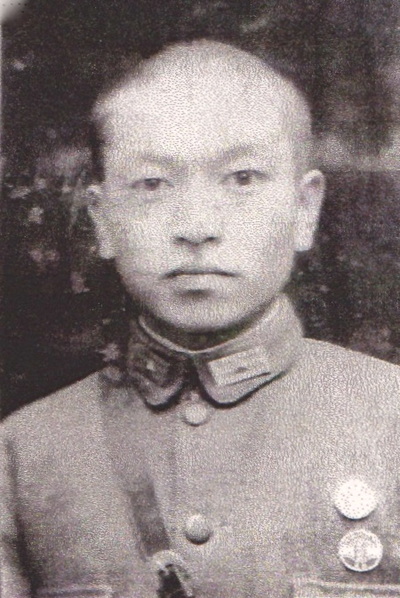

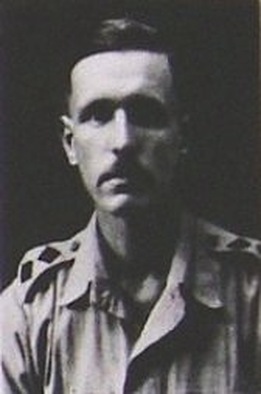

Lieutenant Heald, pictured here in 1944.

Philip Anthony Mair Heald was a member of the 2nd Burma Rifles during the Chindit operation in 1943. These were a special calibre of men who held vital local knowledge about the Burmese population and countryside in which the fledgling Chindits would operate. The Burma Riflemen and their trusted officers would become crucial during the operation, using their experience to help traverse the difficult terrain effectively, find water and food when ration drops were not possible and negotiate with local villagers for boats and other such requirements.

The men of the first Chindit expedition held their Burma Riflemen in high regard and soon became reliant on their skill, leadership and jungle craft.

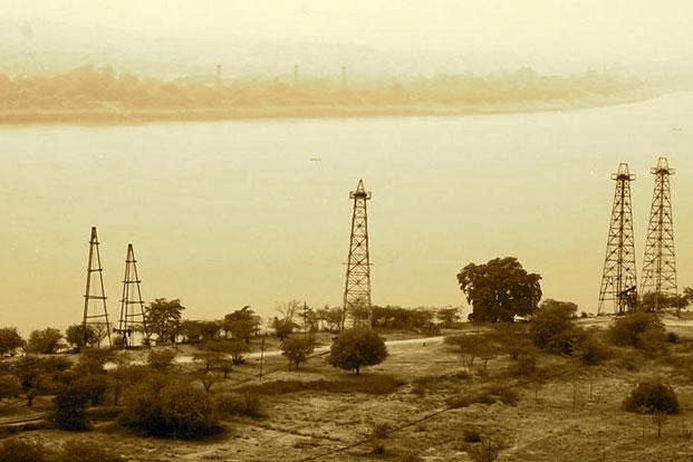

Lieutenant Heald, known as Tony to his friends and family, had worked for the Burmah Oil Company before the war as a Labour Welfare Officer. He had been sent to Chauk, a port-town in central Burma, situated on the banks of the Irrawaddy River. This was an important petroleum port for the Singu-Chauk oil fields, which had been discovered by British engineers in 1902. Once extracted, the crude oil from Chauk was sent by a 350 mile long pipeline to a place called Syriam for the refining process.

Like so many of his counterparts in the Burma Rifles, Tony had decided to enlist into the British Indian Army after witnessing the sweeping successes of the invading Japanese forces in Burma and especially after the painful and disastrous retreat by the British in the later part of 1941 and early 1942. Many men from his battalion (2nd Burma Rifles) had been displaced by the Japanese advance, forced to leave their posts as forestry officers, oil company officials and other such professional roles across Burmese industry.

Tony went through his Officer Cadet training in early 1942 and was commissioned to 2nd Lieutenant on April 15th that year. Presumably he was immediately posted to the 2nd Burma Rifles, although I do not have any actual details to confirm this. He was given the Army number 233584. The 2nd Burma Rifles had originally been based at Maymyo, a British hill station close to the city of Mandalay. In a different guise they had been involved in the retreat from the advancing Japanese Army and had fought against the enemy at places such as Allanmyo and Thayetmyo. Eventually the unit withdrew back into India, basing itself for a short time at Imphal in Assam.

The battalion remained in the Imphal area until 1st June before moving to Ranchi for refitting. In July the battalion moved to Hoshiarpur for re-equipping before finally moving to a rest camp at Dharmsala in August. In September, the battalion moved to join 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in the Saugor area and began preparing for the first Chindit Operation. At some point during this period Tony Heald would have joined up with his new unit and been absorbed into the battalion structure as a WS or War Substantive Lieutenant.

For more information about the history of the 2nd Burma Rifles, please click on the link below:

http://homepages.force9.net/rothwell/burmaweb/2ndburma.htm

Update 27/09/2014.

From information kindly sent to me by Steve Rothwell, I now know that 2nd Lieutenant Heald was originally posted to the 10th Battalion of the Burma Rifles after his commission. The 10th Battalion was the training battalion for the regiment, with Officers and Other Ranks passing through before they were given more permanent placements elsewhere in the regiment. After the retreat from Burma in early 1942, all surviving men from the regiment, including those from the 10th Battalion were amalgamated into the Composite Burma Rifles Battalion. This Composite unit would re-emerge later in the year as the 2nd Burma Rifles and go on to serve with the Chindits.

The men of the first Chindit expedition held their Burma Riflemen in high regard and soon became reliant on their skill, leadership and jungle craft.

Lieutenant Heald, known as Tony to his friends and family, had worked for the Burmah Oil Company before the war as a Labour Welfare Officer. He had been sent to Chauk, a port-town in central Burma, situated on the banks of the Irrawaddy River. This was an important petroleum port for the Singu-Chauk oil fields, which had been discovered by British engineers in 1902. Once extracted, the crude oil from Chauk was sent by a 350 mile long pipeline to a place called Syriam for the refining process.

Like so many of his counterparts in the Burma Rifles, Tony had decided to enlist into the British Indian Army after witnessing the sweeping successes of the invading Japanese forces in Burma and especially after the painful and disastrous retreat by the British in the later part of 1941 and early 1942. Many men from his battalion (2nd Burma Rifles) had been displaced by the Japanese advance, forced to leave their posts as forestry officers, oil company officials and other such professional roles across Burmese industry.

Tony went through his Officer Cadet training in early 1942 and was commissioned to 2nd Lieutenant on April 15th that year. Presumably he was immediately posted to the 2nd Burma Rifles, although I do not have any actual details to confirm this. He was given the Army number 233584. The 2nd Burma Rifles had originally been based at Maymyo, a British hill station close to the city of Mandalay. In a different guise they had been involved in the retreat from the advancing Japanese Army and had fought against the enemy at places such as Allanmyo and Thayetmyo. Eventually the unit withdrew back into India, basing itself for a short time at Imphal in Assam.

The battalion remained in the Imphal area until 1st June before moving to Ranchi for refitting. In July the battalion moved to Hoshiarpur for re-equipping before finally moving to a rest camp at Dharmsala in August. In September, the battalion moved to join 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in the Saugor area and began preparing for the first Chindit Operation. At some point during this period Tony Heald would have joined up with his new unit and been absorbed into the battalion structure as a WS or War Substantive Lieutenant.

For more information about the history of the 2nd Burma Rifles, please click on the link below:

http://homepages.force9.net/rothwell/burmaweb/2ndburma.htm

Update 27/09/2014.

From information kindly sent to me by Steve Rothwell, I now know that 2nd Lieutenant Heald was originally posted to the 10th Battalion of the Burma Rifles after his commission. The 10th Battalion was the training battalion for the regiment, with Officers and Other Ranks passing through before they were given more permanent placements elsewhere in the regiment. After the retreat from Burma in early 1942, all surviving men from the regiment, including those from the 10th Battalion were amalgamated into the Composite Burma Rifles Battalion. This Composite unit would re-emerge later in the year as the 2nd Burma Rifles and go on to serve with the Chindits.

The 2nd Burma Rifles arrived at the Abchand Camp and entered into full Chindit training on the 17th September 1942. Tony Heald was placed into Column 5 under the command of Major Bernard Fergusson formerly of the Black Watch. Here is how their arrival was logged in the 13th Kings War diary for that period:

"The Burma Rifle detachment arrived today, they will be distributed to all Columns at the rate of 2 British Officers and 41 men to each."

Alongside Tony in the Burma Rifle section of Column 5 was Captain John Coleridge Fraser, a tough Scot who had succeeded in escaping from Japanese captivity just a few short months previous, during the arduous retreat from Burma. After completing their jungle warfare training the Burma Rifle sections, along with their respective Chindit Columns moved across to Assam once more. On February 14th 1943 they re-entered Burma and Operation Longcloth began.

Most of my information in regard to Lieutenant Heald and his time with Column 5 in 1943 comes from the book 'Beyond the Chindwin', written by his then commander, Major Bernard Fergusson. Fergusson immediately nicknamed the young Lieutenant 'PAM', obviously combining the three initials from the soldiers christian names. This nickname stuck fast and was used from that moment on by all his Chindit comrades.

Major Fergusson was always one of the first to recognise the work done by the men of the Burma Rifles in 1943, placing a great deal of faith in their skills as guides and interpreters. There is no doubt that these men were responsible for saving the lives of many during the operation, either by securing food from local villages when the men were starving, or by leading lost British soldiers home once dispersal had been called.

From the book 'Beyond the Chindwin', Bernard Fergusson describes his first meeting with the two Burma Rifle Officers:

"In a hut skilfully built by some of the Burma Riflemen I first met my officers. John Fraser, who commanded my Burma Rifle platoon, dark and spectacled and showing no sign of the shocking ordeal from which he had emerged only six weeks before (a reference to his escape from being a prisoner of the Japanese earlier in 1942). Like all of these officers he was employed in one of the big civilian firms in Burma, John's being in the rice department of Steel Brothers; and also like most of them he was from Scotland. His second officer was 'PAM' Heald, broad-shouldered, fair and young; he had been a housemaster at a Borstal before becoming a Labour Welfare Officer under the Burmah Oil people at Chauk."

Early on in the books pages, Fergusson recounts on many occasions how Lieutenant Heald was worth his own weight in gold, helping lead the column on river-craft exercises and especially his accuracy in map reading and orientation. He (Fergusson) was none too pleased in early December 1942 when he lost Heald to another unit for a short while, due to the ill health of the other column's Burma Rifle officers. However, 'PAM' was back with Column 5 in time for their Christmas and New Year's celebrations in the railway junction town of Jhansi, and their final preparations before setting off for Imphal, the last staging point before 77th Brigade entered Burma and Operation Longcloth commenced.

"The Burma Rifle detachment arrived today, they will be distributed to all Columns at the rate of 2 British Officers and 41 men to each."

Alongside Tony in the Burma Rifle section of Column 5 was Captain John Coleridge Fraser, a tough Scot who had succeeded in escaping from Japanese captivity just a few short months previous, during the arduous retreat from Burma. After completing their jungle warfare training the Burma Rifle sections, along with their respective Chindit Columns moved across to Assam once more. On February 14th 1943 they re-entered Burma and Operation Longcloth began.

Most of my information in regard to Lieutenant Heald and his time with Column 5 in 1943 comes from the book 'Beyond the Chindwin', written by his then commander, Major Bernard Fergusson. Fergusson immediately nicknamed the young Lieutenant 'PAM', obviously combining the three initials from the soldiers christian names. This nickname stuck fast and was used from that moment on by all his Chindit comrades.

Major Fergusson was always one of the first to recognise the work done by the men of the Burma Rifles in 1943, placing a great deal of faith in their skills as guides and interpreters. There is no doubt that these men were responsible for saving the lives of many during the operation, either by securing food from local villages when the men were starving, or by leading lost British soldiers home once dispersal had been called.

From the book 'Beyond the Chindwin', Bernard Fergusson describes his first meeting with the two Burma Rifle Officers:

"In a hut skilfully built by some of the Burma Riflemen I first met my officers. John Fraser, who commanded my Burma Rifle platoon, dark and spectacled and showing no sign of the shocking ordeal from which he had emerged only six weeks before (a reference to his escape from being a prisoner of the Japanese earlier in 1942). Like all of these officers he was employed in one of the big civilian firms in Burma, John's being in the rice department of Steel Brothers; and also like most of them he was from Scotland. His second officer was 'PAM' Heald, broad-shouldered, fair and young; he had been a housemaster at a Borstal before becoming a Labour Welfare Officer under the Burmah Oil people at Chauk."

Early on in the books pages, Fergusson recounts on many occasions how Lieutenant Heald was worth his own weight in gold, helping lead the column on river-craft exercises and especially his accuracy in map reading and orientation. He (Fergusson) was none too pleased in early December 1942 when he lost Heald to another unit for a short while, due to the ill health of the other column's Burma Rifle officers. However, 'PAM' was back with Column 5 in time for their Christmas and New Year's celebrations in the railway junction town of Jhansi, and their final preparations before setting off for Imphal, the last staging point before 77th Brigade entered Burma and Operation Longcloth commenced.

Once inside Burma Lieutenant Heald was used on many occasions as the link man and interpreter, gaining information about the Japanese garrison locations and their numbers and movements, all this obtained from the various local Headmen of villages the column passed through during their long and winding pathway in 1943. He was present during the Column's first engagement with the enemy at Bonchaung, where the Commandos from Column 5 blew up the railway lines and bridges in an attempt to prevent the Japanese from supplying their troops to the north of the country.

After their work at Bonchaung was complete the Column moved quickly eastward to the banks of the Irrawaddy River. After some deliberation Wingate decided to put his men across the river and push on further into occupied territory. Column 5 reached the fast flowing Irrawaddy at a place called Tigyaing, they were warmly welcomed by the villagers and decided to take this opportunity to re-stock the larder; from Bernard Fergusson's book comes this paraphrased quote:

"Pam Heald stood at the end of the main street on the waterfront, looking much like a harvest festival co-ordinator, or Ceres, the goddess of plenty (I hope that's right). He had been entrusted with the buying of foodstuffs which would see us through until we got our next supply drop. Among other things, he had amassed eggs, potatoes, rice, vegetables in great quantities, cheroots and fruit of all kinds. He had also indulged in one or two private purchases, out of (or so he assured me) his own pocket: Scott's Porage Oats, Polson's Butter, and some tinned oysters, for which he had paid fabulous prices. They were the last such items in Tigyaing, and I should think the last in Upper Burma. He had always a prodigious appetite, and at intervals a man from a nearby restaurant was bringing him plates of pork and potatoes."

Over the coming days and weeks Lieutenant Heald led his Burma Riflemen through the winding tracks and bamboo jungles, seeking out the best or safest route for the Column to follow, as they and the other units pushed deeper into Japanese held territory. On the 25th of March Wingate decided to have one large scale supply drop for all his local Columns at a location just outside a village called Baw. Column 5 were just short of this location, having previously acted as section rearguard for the other units. Fergusson could hear that the supply drop had been compromised and that the Columns 7 and 8 were now engaged in battle with the Japanese. Placing Captain Fraser in charge of the main body of Column 5, he (Fergusson) along with Lieutenant Heald and a section of Karens (Burma Rifles Other Ranks) set off at pace towards Baw.

The Major by his own admission made a foolish error of judgement at this moment by leaving his own pack and rations with the main body of the Column, stuffing just a simple packet of biscuits into his pocket for what he believed to be the four or five hour march. He also left his maps and compass behind, trusting only to the map carried by Lieutenant Heald. Having trouble locating the rendezvous point which had been radioed forward by the other Chindit Columns a few hours previously, Fergusson decided to split his party up into small groups. In time frustration took hold and the Major and his escort, Rifleman Jameson became lost. They moved back and forth along a dried up river bed or chaung trying to find the jungle track suggested by the other Columns as leading to Baw. Tempers frayed as the heat of the day began to take it's toll and exhaustion set in.

From 'Beyond the Chindwin':

"I (Fergusson) reckoned we had walked twenty miles since we first set out, if I was tired then Jameson was whacked; and now he sat down and said he could go no further. I gave him five minutes and then hauled him to his feet and we started off again, striving hard to keep on our northward bearing, but being deflected from it every few yards by impassable jungle. It was nearly seven o'clock, the moment Pam was due to move away, I was nearly in tears, the whole jungle was strange, and we were irrevocably lost. Suddenly we heard the unmistakeable sound of a column marching through teak undergrowth: we crouched on the ground and held our breath, then Jameson cried out,"There is our Adjutant. It is our column!" In the same second, out of the bush popped the head of Pam Heald. It felt like a miracle, and I have never been more aware of God's mercy."

Column 5 did eventually make the rendezvous with other Chindit units just west of the village of Baw. Wingate had received a communication from General India Command telling him to draw a halt to the expedition and exit Burma immediately. The plan now was to move back toward the Irrawaddy as quickly as possible. Wingate once again handed the role of rearguard to Column 5. They were to obliterate all tracks and make a false trail for the ever-gaining Japanese patrols to follow.

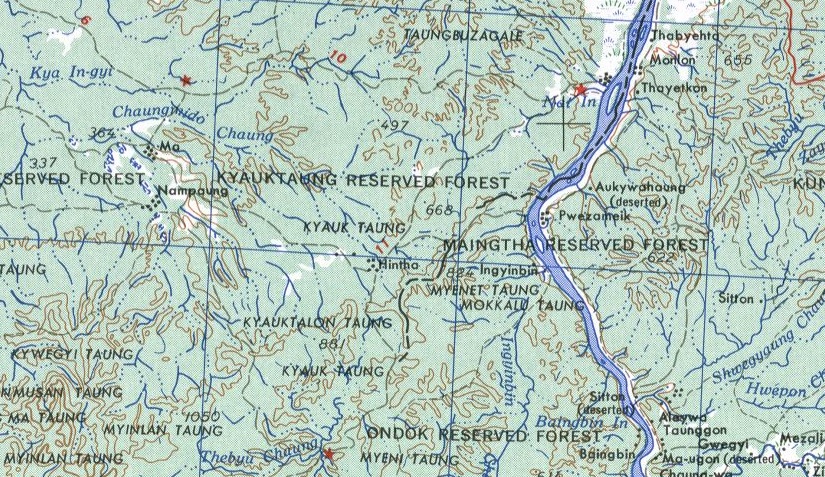

As the main group headed westward toward Inywa, Column 5 began their deception against the Japanese who were now following up quickly on the Chindits coat tails. Their route took them toward the Burmese village of Hintha, which they reached on the evening of 29th March. At Hintha, Column 5 met their Waterloo. The men were caught in a violent action against the Japanese in the village and many casualties were taken on both sides. Seeing no reason to prolong this engagement Bernard Fergusson called for their withdrawal and the Chindits of Column 5 broke away to the northeast.

Several of the Burma Riflemen had been wounded in the action, including Naik Jameson and another man named Nay Dun. In the confusion of the withdrawal some of the men became separated from Major Fergusson and the main group. The Japanese had ambushed the column as it dispersed away from Hintha and had cut-off around 100 men including my grandfather and Lieutenant Heald. These men gave up the original plan of moving west toward Inywa and struck out northeast once again in the general direction of the Shweli River and it's confluence with the Irrawaddy.

After their work at Bonchaung was complete the Column moved quickly eastward to the banks of the Irrawaddy River. After some deliberation Wingate decided to put his men across the river and push on further into occupied territory. Column 5 reached the fast flowing Irrawaddy at a place called Tigyaing, they were warmly welcomed by the villagers and decided to take this opportunity to re-stock the larder; from Bernard Fergusson's book comes this paraphrased quote:

"Pam Heald stood at the end of the main street on the waterfront, looking much like a harvest festival co-ordinator, or Ceres, the goddess of plenty (I hope that's right). He had been entrusted with the buying of foodstuffs which would see us through until we got our next supply drop. Among other things, he had amassed eggs, potatoes, rice, vegetables in great quantities, cheroots and fruit of all kinds. He had also indulged in one or two private purchases, out of (or so he assured me) his own pocket: Scott's Porage Oats, Polson's Butter, and some tinned oysters, for which he had paid fabulous prices. They were the last such items in Tigyaing, and I should think the last in Upper Burma. He had always a prodigious appetite, and at intervals a man from a nearby restaurant was bringing him plates of pork and potatoes."

Over the coming days and weeks Lieutenant Heald led his Burma Riflemen through the winding tracks and bamboo jungles, seeking out the best or safest route for the Column to follow, as they and the other units pushed deeper into Japanese held territory. On the 25th of March Wingate decided to have one large scale supply drop for all his local Columns at a location just outside a village called Baw. Column 5 were just short of this location, having previously acted as section rearguard for the other units. Fergusson could hear that the supply drop had been compromised and that the Columns 7 and 8 were now engaged in battle with the Japanese. Placing Captain Fraser in charge of the main body of Column 5, he (Fergusson) along with Lieutenant Heald and a section of Karens (Burma Rifles Other Ranks) set off at pace towards Baw.

The Major by his own admission made a foolish error of judgement at this moment by leaving his own pack and rations with the main body of the Column, stuffing just a simple packet of biscuits into his pocket for what he believed to be the four or five hour march. He also left his maps and compass behind, trusting only to the map carried by Lieutenant Heald. Having trouble locating the rendezvous point which had been radioed forward by the other Chindit Columns a few hours previously, Fergusson decided to split his party up into small groups. In time frustration took hold and the Major and his escort, Rifleman Jameson became lost. They moved back and forth along a dried up river bed or chaung trying to find the jungle track suggested by the other Columns as leading to Baw. Tempers frayed as the heat of the day began to take it's toll and exhaustion set in.

From 'Beyond the Chindwin':

"I (Fergusson) reckoned we had walked twenty miles since we first set out, if I was tired then Jameson was whacked; and now he sat down and said he could go no further. I gave him five minutes and then hauled him to his feet and we started off again, striving hard to keep on our northward bearing, but being deflected from it every few yards by impassable jungle. It was nearly seven o'clock, the moment Pam was due to move away, I was nearly in tears, the whole jungle was strange, and we were irrevocably lost. Suddenly we heard the unmistakeable sound of a column marching through teak undergrowth: we crouched on the ground and held our breath, then Jameson cried out,"There is our Adjutant. It is our column!" In the same second, out of the bush popped the head of Pam Heald. It felt like a miracle, and I have never been more aware of God's mercy."

Column 5 did eventually make the rendezvous with other Chindit units just west of the village of Baw. Wingate had received a communication from General India Command telling him to draw a halt to the expedition and exit Burma immediately. The plan now was to move back toward the Irrawaddy as quickly as possible. Wingate once again handed the role of rearguard to Column 5. They were to obliterate all tracks and make a false trail for the ever-gaining Japanese patrols to follow.

As the main group headed westward toward Inywa, Column 5 began their deception against the Japanese who were now following up quickly on the Chindits coat tails. Their route took them toward the Burmese village of Hintha, which they reached on the evening of 29th March. At Hintha, Column 5 met their Waterloo. The men were caught in a violent action against the Japanese in the village and many casualties were taken on both sides. Seeing no reason to prolong this engagement Bernard Fergusson called for their withdrawal and the Chindits of Column 5 broke away to the northeast.

Several of the Burma Riflemen had been wounded in the action, including Naik Jameson and another man named Nay Dun. In the confusion of the withdrawal some of the men became separated from Major Fergusson and the main group. The Japanese had ambushed the column as it dispersed away from Hintha and had cut-off around 100 men including my grandfather and Lieutenant Heald. These men gave up the original plan of moving west toward Inywa and struck out northeast once again in the general direction of the Shweli River and it's confluence with the Irrawaddy.

There is no doubt in my mind that Lieutenant Heald would have taken control of the separated group after the battle at Hintha and led the men toward the Shweli River in the hope of breaking out of the net that was closing in around the Chindits at that time. As fortune would have it the group bumped into Major Gilkes on the southern banks of the Shweli and the men from Column 5 were absorbed into Column 7's predetermined dispersal groups. Gilkes had already decided to exit Burma via the Yunnan border with China, trekking north until he and his men reached the safety of Allied held territory. The main problem with this strategy was the distances involved and the lack of accurate maps, and also that the men from Column 5 had not eaten properly for several days and were in poor physical shape compared to their brothers in Column 7.

Pam Heald was given charge of one of the dispersal parties. The route over the moutains of Yunnan Province was arduous and exhaustion and hunger soon took hold. Many men, including Lieutenant Heald were now suffering from the ravages of disease, malaria, dysentery and beri beri were common place amongst the troops. Having failed to cross the Shweli in early April the dispersal parties from Column 7 now moved towards the Irrawaddy once more. From the War Diary of Column 7, dated April 9th 1943:

"Lieutenant Heald took parties off to cross the Irrawaddy. Officers Walker, Musgrave-Wood and Campbell-Paterson each with 20-30 personnel were to cross independently and unite for a supply drop on the west side of the river. After one hours marching it was discovered that 5 Column's Burma Rifle platoon were not with the unit. Unable to track them Lieutenant Heald considered it advisable to abandon the project in view of there being no Burmese-speaking personnel to assist in acquiring information from local villagers or boats to cross the river."

Pam Heald was given charge of one of the dispersal parties. The route over the moutains of Yunnan Province was arduous and exhaustion and hunger soon took hold. Many men, including Lieutenant Heald were now suffering from the ravages of disease, malaria, dysentery and beri beri were common place amongst the troops. Having failed to cross the Shweli in early April the dispersal parties from Column 7 now moved towards the Irrawaddy once more. From the War Diary of Column 7, dated April 9th 1943:

"Lieutenant Heald took parties off to cross the Irrawaddy. Officers Walker, Musgrave-Wood and Campbell-Paterson each with 20-30 personnel were to cross independently and unite for a supply drop on the west side of the river. After one hours marching it was discovered that 5 Column's Burma Rifle platoon were not with the unit. Unable to track them Lieutenant Heald considered it advisable to abandon the project in view of there being no Burmese-speaking personnel to assist in acquiring information from local villagers or boats to cross the river."

Pam Heald seen after dispersal at Shillong, India.

What then became of the dispersal groups mentioned in the War diary? Lieutenant Rex Walker's party never reached the rendezvous point on the west bank of the Irrawaddy River. Neither he, nor any of his men returned to India that year, although five of this group did survive their time as prisoners of war in Rangoon Jail.

Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson was also captured along with the vast majority of his dispersal party, he ended up at Changi Prison Camp in Singapore, where he was liberated in the late summer of 1945. Captain Musgrave-Wood, also a Burma Rifle Officer on Operation Longcloth, succeeded in getting the majority of his dispersal group back to India via the Chinese borders. Amongst his original party were my grandfather and 5 other men, unfortunately these soldiers, already exhausted by the tribulations of the expedition, all became prisoners of war, only one, Leon Frank survived. To read more about any of the men mentioned above, or elsewhere in this story, simply enter their name into the search engine box found in the top right corner of every page.

After turning back at the Irrawaddy, Pam Heald and his group must have picked up the trail of Major Gilkes and the remainder of Column 7, because there is no doubt that he and his men travelled out of Burma in 1943 via the Chinese borders. Gilkes had doubled back to the Shweli River, successfully crossing at the second attempt at a place called Nayok.

From the book 'March or Die' and with the kind permission of the author Philip Chinnery:

"7 Column had been split in two when Wingate called off the crossing of the Irrawaddy at Inywa. When the order to disperse was given, the column commander, Major Ken Gilkes, decided to head for China. They had been joined by about 110 members of 5 Column who had failed to rejoin Major Fergusson after the fight at Hintha. Major Gilkes quite correctly separated those he considered physically capable of completing the journey to China, from those who were too weak or sick and ordered them to return to India by various routes. Many would be lost on the way. One of the parties, under Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood, reached Fort Hertz in good condition. The larger party, mostly comprising 5 Column men, was not heard from again.

Major Gilkes led his men south over the Mongmit—Myitson Road and then marched north-east to Nayok on the Shweli River, crossed over on 11th April and moved into the Kachin Hills. After a long journey they climbed a broad belt of mountains and linked up with Chinese irregular troops. The inhabitants of the first Chinese village fed all 150 of them and refused any payment. 'You have fought the enemies of China. The least we can do is feed you,' they were told. The Chinese guerrilla officer at Lenma remarked that he was delighted to meet British Officers with uncreased trousers who made no demands for beds to sleep on.

Eventually they reached the Salween Valley front, where the Japanese had been advancing when Wingate took his Brigade into Burma. There they watched a seven-day battle in which the Chinese routed the Japanese, who had transferred a full division to Burma to deal with the Chindits. They then crossed the Salween and later the Mekong Rivers, using guides supplied by the regular Chinese Army. Eventually they reached Kunming, having marched 1,500 miles since leaving Imphal in February. They were greeted with flags flying and a band playing military marches and the commander in-chief at Kunming lodged them in the best building in the town. They were given baths, new clothes and haircuts and the Chinese General even advanced Gilkes enough money to pay his men.

Only sixteen men from 5 Column reached China safely. They had acted as rearguard all the way and had lost eleven killed in four separate actions. Eventually Major Gilkes and his men were flown back to India from Kunming in planes from the United States 10th Air Force."

On the 24th May Major Gilkes reported in his War Diary that Lieutenant Heald was once again suffering from the fever that had plagued him in the latter weeks of the Longloth expedition. Heald's body weight was down to just 10st 4lbs.

During the time spent with the Chinese Army in Yunnan, Lieutenant Heald had made friends with an officer from the General Staff of the 36th Chinese Division. Major Han Shih Chieh had very much enjoyed meeting Heald and the other Chindit Officers from Column 7's dispersal parties and decided to write to Pam Heald in June 1944, asking how the officer had got on after returning to India. Here is a transcription of the letter:

Dear Lt. Heald,

I was very concerned about how was the travel from Chaio-To to India for you and your sick men. I was promoted to Division HQ, General Staff, one month after you left Chaio-To. Now I am Assistant Chief of Staff of G.I.

I just received your letter on 05/06/1944 that I hoped would reach me. Thanks for your photo and I shall keep it very carefully, and I shall treasure always the pistol and binoculars you so kindly gave me.

We are just making a general attack in Yunnan and then Burma. We have killed about 1500 of the enemy here. We took back Waitien yesterday. We will attack Tung-Chung very soon. I hope we meet in Rangoon in 1944.

Captain Ma left our Division last December. Now he is studying in a University in Kunming. I will tell him that you asked to be remembered to him. I would like to send some Japanese souvenirs in my next letter. Please say hello to Captain Pickling (Pickering) and the rest of your party. Please write and tell me how you are and anything about India. Good luck to you and your country in our common fight.

Major Han Shih Chieh (then signed in Chinese characters).

P.S. Did not mail this, so am enclosing money and Japanese photos in this one. Signed H.S.C.

The men eventually crossed over into Allied held territory on June 9th. They had received great help from the Chinese troops they had met along the way. These men were the last main group of Longcloth survivors to reach safety in 1943, only a handful of Gurkha Riflemen straggled back over the Chindwin River after this date.

Lieutenant Heald was eventually taken to the British Military Hospital in Rawalpindi to be treated for exhaustion, malnutrition and malaria. He was released from hospital in early November and rejoined the battalion, becoming Adjutant on the 24th November 1943.

The photograph below was probably taken in late 1943 or early 1944. Captain Heald is surrounded by men from the 2nd Burma Rifles all wearing Chindit flashes on their right arm. This insignia was not issued to the men in 1943, which makes me feel confident that this was taken just before the second expedition in March 1944. Although I cannot identify any of the other officers it can be assumed that they are soldiers who also served on Operation Longcloth in 1943. The man standing behind Tony's right shoulder has the medal ribbon for the Military Cross and the soldier far right as we look, possibly the Indian Order of Merit, these gallantry awards are likely to be for their efforts on Longcloth.

Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson was also captured along with the vast majority of his dispersal party, he ended up at Changi Prison Camp in Singapore, where he was liberated in the late summer of 1945. Captain Musgrave-Wood, also a Burma Rifle Officer on Operation Longcloth, succeeded in getting the majority of his dispersal group back to India via the Chinese borders. Amongst his original party were my grandfather and 5 other men, unfortunately these soldiers, already exhausted by the tribulations of the expedition, all became prisoners of war, only one, Leon Frank survived. To read more about any of the men mentioned above, or elsewhere in this story, simply enter their name into the search engine box found in the top right corner of every page.

After turning back at the Irrawaddy, Pam Heald and his group must have picked up the trail of Major Gilkes and the remainder of Column 7, because there is no doubt that he and his men travelled out of Burma in 1943 via the Chinese borders. Gilkes had doubled back to the Shweli River, successfully crossing at the second attempt at a place called Nayok.

From the book 'March or Die' and with the kind permission of the author Philip Chinnery:

"7 Column had been split in two when Wingate called off the crossing of the Irrawaddy at Inywa. When the order to disperse was given, the column commander, Major Ken Gilkes, decided to head for China. They had been joined by about 110 members of 5 Column who had failed to rejoin Major Fergusson after the fight at Hintha. Major Gilkes quite correctly separated those he considered physically capable of completing the journey to China, from those who were too weak or sick and ordered them to return to India by various routes. Many would be lost on the way. One of the parties, under Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood, reached Fort Hertz in good condition. The larger party, mostly comprising 5 Column men, was not heard from again.

Major Gilkes led his men south over the Mongmit—Myitson Road and then marched north-east to Nayok on the Shweli River, crossed over on 11th April and moved into the Kachin Hills. After a long journey they climbed a broad belt of mountains and linked up with Chinese irregular troops. The inhabitants of the first Chinese village fed all 150 of them and refused any payment. 'You have fought the enemies of China. The least we can do is feed you,' they were told. The Chinese guerrilla officer at Lenma remarked that he was delighted to meet British Officers with uncreased trousers who made no demands for beds to sleep on.

Eventually they reached the Salween Valley front, where the Japanese had been advancing when Wingate took his Brigade into Burma. There they watched a seven-day battle in which the Chinese routed the Japanese, who had transferred a full division to Burma to deal with the Chindits. They then crossed the Salween and later the Mekong Rivers, using guides supplied by the regular Chinese Army. Eventually they reached Kunming, having marched 1,500 miles since leaving Imphal in February. They were greeted with flags flying and a band playing military marches and the commander in-chief at Kunming lodged them in the best building in the town. They were given baths, new clothes and haircuts and the Chinese General even advanced Gilkes enough money to pay his men.

Only sixteen men from 5 Column reached China safely. They had acted as rearguard all the way and had lost eleven killed in four separate actions. Eventually Major Gilkes and his men were flown back to India from Kunming in planes from the United States 10th Air Force."

On the 24th May Major Gilkes reported in his War Diary that Lieutenant Heald was once again suffering from the fever that had plagued him in the latter weeks of the Longloth expedition. Heald's body weight was down to just 10st 4lbs.

During the time spent with the Chinese Army in Yunnan, Lieutenant Heald had made friends with an officer from the General Staff of the 36th Chinese Division. Major Han Shih Chieh had very much enjoyed meeting Heald and the other Chindit Officers from Column 7's dispersal parties and decided to write to Pam Heald in June 1944, asking how the officer had got on after returning to India. Here is a transcription of the letter:

Dear Lt. Heald,

I was very concerned about how was the travel from Chaio-To to India for you and your sick men. I was promoted to Division HQ, General Staff, one month after you left Chaio-To. Now I am Assistant Chief of Staff of G.I.

I just received your letter on 05/06/1944 that I hoped would reach me. Thanks for your photo and I shall keep it very carefully, and I shall treasure always the pistol and binoculars you so kindly gave me.

We are just making a general attack in Yunnan and then Burma. We have killed about 1500 of the enemy here. We took back Waitien yesterday. We will attack Tung-Chung very soon. I hope we meet in Rangoon in 1944.

Captain Ma left our Division last December. Now he is studying in a University in Kunming. I will tell him that you asked to be remembered to him. I would like to send some Japanese souvenirs in my next letter. Please say hello to Captain Pickling (Pickering) and the rest of your party. Please write and tell me how you are and anything about India. Good luck to you and your country in our common fight.

Major Han Shih Chieh (then signed in Chinese characters).

P.S. Did not mail this, so am enclosing money and Japanese photos in this one. Signed H.S.C.

The men eventually crossed over into Allied held territory on June 9th. They had received great help from the Chinese troops they had met along the way. These men were the last main group of Longcloth survivors to reach safety in 1943, only a handful of Gurkha Riflemen straggled back over the Chindwin River after this date.

Lieutenant Heald was eventually taken to the British Military Hospital in Rawalpindi to be treated for exhaustion, malnutrition and malaria. He was released from hospital in early November and rejoined the battalion, becoming Adjutant on the 24th November 1943.

The photograph below was probably taken in late 1943 or early 1944. Captain Heald is surrounded by men from the 2nd Burma Rifles all wearing Chindit flashes on their right arm. This insignia was not issued to the men in 1943, which makes me feel confident that this was taken just before the second expedition in March 1944. Although I cannot identify any of the other officers it can be assumed that they are soldiers who also served on Operation Longcloth in 1943. The man standing behind Tony's right shoulder has the medal ribbon for the Military Cross and the soldier far right as we look, possibly the Indian Order of Merit, these gallantry awards are likely to be for their efforts on Longcloth.

In late March this year (2013), I received this email contact via my website:

Dear Mr. Fogden

Is it possible to find the record of a Chindit and the column he served in from just the name? I have an interest in the Chindits because my father-in-law PAM Heald served with Bernard Fergusson. Thank you.

The email was sent by James Robinson who is married to Tony Heald's daughter, Jude. Over a short period we exchanged details about Tony and hopefully the family found some of my information both new and of interest. The family were able to tell me about his life after he had left the Army and returned to the United Kingdom. Here is a brief résumé of his working life after the war, taken from an obituary sent to me by James and Jude.

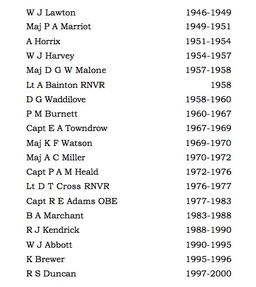

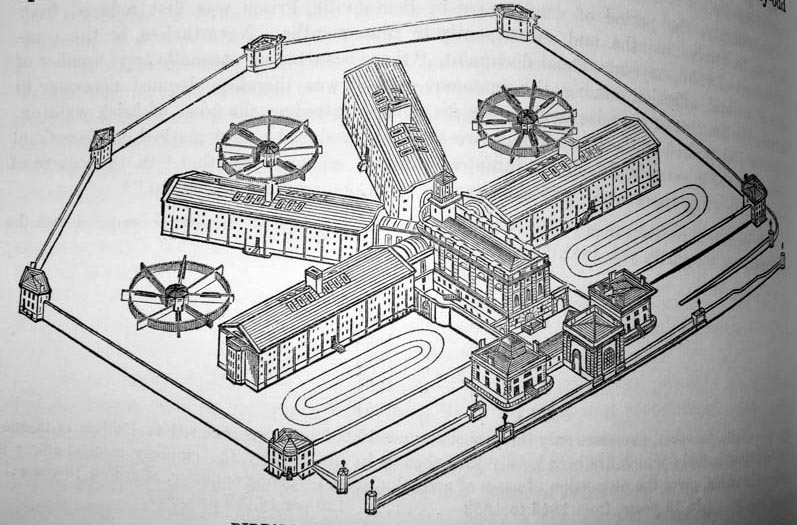

Tony 'Pam' Heald, prison governor, died on September 28th, 1991, aged 76.

Tony Heald had a career in the prison service spanning almost four decades and was governor of four prisons, finally of Pentonville in 1972. During his time in charge the prison managed to escape significant trouble at a time of serious disturbances in several other jails, when prisoners were aggressive in demands for what they perceived to be their rights. Heald was regarded by his colleagues, staff and prisoners as urbane, good-humoured and very polite. He was not particularly concerned with systems and organisation, but rather with the people under his charge.

Philip Anthony Mair Heald (nicknamed PAM after his first three initials) was born in Alexandria, Egypt on September 24th 1915, returning to England to be educated at Blundell's School, in Devon. After teaching in a preparatory school he joined the prison service in 1936 at the age of just 21, and became a housemaster at North Sea Camp Borstal under the influence of the then Governor Alexander Paterson. Working at the North Sea Camp in those early days was an unforgettable and demanding experience. As in the world outside, there was then a greater underlying sense of discipline, which allowed for informal give-and-take between boys and staff without the sacrifice of authority.

Housemasters lived in cubicles at the end of the boys dormitories. On one occasion at least, Heald was subjected to a practical joke when boys removed all springs from his bed, so that as he tried to get in he fell straight through the bed onto the floor.

Paterson encouraged young housemasters to gain experience abroad and Heald joined the Burmah Oil Company as personnel officer in 1937. He was caught up in the war and eventually joined Wingate's Chindits. He completed his war service as a Captain before returning briefly to the Burmah Oil Company.

In 1946 he rejoined the prison service as a clerical officer at Wormwood Scrubs in London, moving later in the year to Dartmoor where he took up a junior governor's post. After the icy winter of 1946/47 at Dartmoor he moved once more to help open Huntercombe Borstal. In 1952 he was promoted and transferred to Liverpool Prison. Further promotion in 1955 saw him reach Governor (Level 3) at Shrewsbury Prison and then onto level two in 1963 at Sudbury Open Prison in Derbyshire.

In 1966 he moved as governor to Exeter Prison where he was also responsible for the open prison at Haldon Camp. He encouraged a local theatre company to give performances for the prisoners which led in due course to the prisoners themselves producing plays. He was promoted to Governor Class One in 1972 and took charge of Pentonville Prison for the last three years of his service.

On retirement he worked for Westminster Chamber of Commerce. On death he leaves his widow, Patricia, daughter of R.L. Bradley, himself a former director of Borstal administration, he also leaves a son and daughter.

It is no surprise that Tony's fair minded approach with the prisoners under his charge had such a positive reaction, even as stated above, during times of great unrest in the prison system. He clearly learned a great deal from Paterson who had been a leading light in penal reform, especially in regard to younger offenders. Paterson's ideas and philosophies can be seen online and in many books, but, reading just two of his more famous quotations, admirably sum up his and to a large degree Tony Heald's concept of penal rehabilitation.

"It is impossible to train men for freedom in a condition of captivity."

"Men come to prison as a punishment, not for punishment."

It is somewhat ironic that Tony Heald would end his Prison Service career at Pentonville Jail. When I first looked for information about the jail online I was struck just how much the design of the prison resembled that of Rangoon Central Jail, the very place that many of his fellow comrades from Column 5 in 1943 ended their living days. I wondered then if Tony ever thought about those men during his time as a Prison Governor. I feel certain that he did.

Pentonville was built in 1842 in North London. Its design was influenced by the 'separate system' much in fashion at that time. Following the need for more prisons after the government decision to end transportation to Australia, Pentonville was completed in 1842 at a cost of £84,000. The design was intended to keep prisoners isolated from each other unlike the more traditional panopticon style.

The Panopticon was a type of institutional building designed by English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the late 18th century. The concept of the design is to allow a watchman to observe all inmates of an institution without their being able to tell whether they are being watched or not. Although its (Pentonville) design consisted of a central hall, with five radiating wings, all of which are visible to staff positioned at the centre, guards had no view into individual cells from their central position. Its design was was more about prisoner isolation rather than prisoner surveillance. It held 520 prisoners under the separate system, each having their own cell. Prisoners were made to undertake work, such as picking tarred rope and weaving. Pentonville became the model for British prisons; a further 54 were built to the same basic design over the next six years. It was built for prisoners awaiting transportation and did not house condemned prisoners until the closure of Newgate in 1902.

Dear Mr. Fogden

Is it possible to find the record of a Chindit and the column he served in from just the name? I have an interest in the Chindits because my father-in-law PAM Heald served with Bernard Fergusson. Thank you.

The email was sent by James Robinson who is married to Tony Heald's daughter, Jude. Over a short period we exchanged details about Tony and hopefully the family found some of my information both new and of interest. The family were able to tell me about his life after he had left the Army and returned to the United Kingdom. Here is a brief résumé of his working life after the war, taken from an obituary sent to me by James and Jude.

Tony 'Pam' Heald, prison governor, died on September 28th, 1991, aged 76.

Tony Heald had a career in the prison service spanning almost four decades and was governor of four prisons, finally of Pentonville in 1972. During his time in charge the prison managed to escape significant trouble at a time of serious disturbances in several other jails, when prisoners were aggressive in demands for what they perceived to be their rights. Heald was regarded by his colleagues, staff and prisoners as urbane, good-humoured and very polite. He was not particularly concerned with systems and organisation, but rather with the people under his charge.

Philip Anthony Mair Heald (nicknamed PAM after his first three initials) was born in Alexandria, Egypt on September 24th 1915, returning to England to be educated at Blundell's School, in Devon. After teaching in a preparatory school he joined the prison service in 1936 at the age of just 21, and became a housemaster at North Sea Camp Borstal under the influence of the then Governor Alexander Paterson. Working at the North Sea Camp in those early days was an unforgettable and demanding experience. As in the world outside, there was then a greater underlying sense of discipline, which allowed for informal give-and-take between boys and staff without the sacrifice of authority.

Housemasters lived in cubicles at the end of the boys dormitories. On one occasion at least, Heald was subjected to a practical joke when boys removed all springs from his bed, so that as he tried to get in he fell straight through the bed onto the floor.

Paterson encouraged young housemasters to gain experience abroad and Heald joined the Burmah Oil Company as personnel officer in 1937. He was caught up in the war and eventually joined Wingate's Chindits. He completed his war service as a Captain before returning briefly to the Burmah Oil Company.

In 1946 he rejoined the prison service as a clerical officer at Wormwood Scrubs in London, moving later in the year to Dartmoor where he took up a junior governor's post. After the icy winter of 1946/47 at Dartmoor he moved once more to help open Huntercombe Borstal. In 1952 he was promoted and transferred to Liverpool Prison. Further promotion in 1955 saw him reach Governor (Level 3) at Shrewsbury Prison and then onto level two in 1963 at Sudbury Open Prison in Derbyshire.

In 1966 he moved as governor to Exeter Prison where he was also responsible for the open prison at Haldon Camp. He encouraged a local theatre company to give performances for the prisoners which led in due course to the prisoners themselves producing plays. He was promoted to Governor Class One in 1972 and took charge of Pentonville Prison for the last three years of his service.

On retirement he worked for Westminster Chamber of Commerce. On death he leaves his widow, Patricia, daughter of R.L. Bradley, himself a former director of Borstal administration, he also leaves a son and daughter.

It is no surprise that Tony's fair minded approach with the prisoners under his charge had such a positive reaction, even as stated above, during times of great unrest in the prison system. He clearly learned a great deal from Paterson who had been a leading light in penal reform, especially in regard to younger offenders. Paterson's ideas and philosophies can be seen online and in many books, but, reading just two of his more famous quotations, admirably sum up his and to a large degree Tony Heald's concept of penal rehabilitation.

"It is impossible to train men for freedom in a condition of captivity."

"Men come to prison as a punishment, not for punishment."

It is somewhat ironic that Tony Heald would end his Prison Service career at Pentonville Jail. When I first looked for information about the jail online I was struck just how much the design of the prison resembled that of Rangoon Central Jail, the very place that many of his fellow comrades from Column 5 in 1943 ended their living days. I wondered then if Tony ever thought about those men during his time as a Prison Governor. I feel certain that he did.

Pentonville was built in 1842 in North London. Its design was influenced by the 'separate system' much in fashion at that time. Following the need for more prisons after the government decision to end transportation to Australia, Pentonville was completed in 1842 at a cost of £84,000. The design was intended to keep prisoners isolated from each other unlike the more traditional panopticon style.

The Panopticon was a type of institutional building designed by English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the late 18th century. The concept of the design is to allow a watchman to observe all inmates of an institution without their being able to tell whether they are being watched or not. Although its (Pentonville) design consisted of a central hall, with five radiating wings, all of which are visible to staff positioned at the centre, guards had no view into individual cells from their central position. Its design was was more about prisoner isolation rather than prisoner surveillance. It held 520 prisoners under the separate system, each having their own cell. Prisoners were made to undertake work, such as picking tarred rope and weaving. Pentonville became the model for British prisons; a further 54 were built to the same basic design over the next six years. It was built for prisoners awaiting transportation and did not house condemned prisoners until the closure of Newgate in 1902.

My thanks must go to Jude and James Robinson for their kind help in forming the story of Tony Heald, his time in Burma during World War Two and his career in the British Prison Service thereafter. Whether it was in the jungles of Burma in 1943 or on one of his prison wings in Pentonville, Tony always led those under his charge, with integrity, thoughtfulness and compassion.

Update 25/11/2016.

Back in October this year (2016), I was delighted to meet up with Jude and Jim Robinson at the Orange Tree public house in Richmond. After an enjoyable hour or two discussing her father's time in Burma, Jude handed me a large folder of papers and documents in relation to Tony Heald's Army Service during WW2.

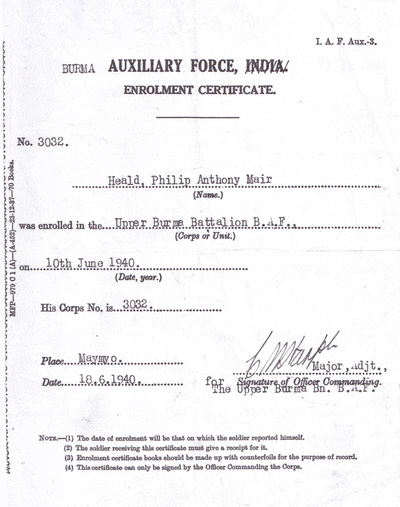

Here is a brief résumé of those documents, concentrating mostly on Tony's postings, promotions and ultimately his resignation from the Burmah Oil Company in late 1945.

As with all employees of the various industries in pre-WW2 Burma, Tony Heald was encouraged to learn the Burmese language as part of his training with the B.O.C. On the 25th April 1939 he was successful in passing the Lower Standard examination and was given a one-off bonus of Rs.1000. On June 10th 1940 he enlisted into the Upper Burma Battalion Auxiliary Force, which was based at Maymyo. Here he attained his first Military service number of the war, 3032.

After attending a (3rd) Militia Course in November 1941, he joined the O.C.T.U. at Maymyo in February 1942 and was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant into the 10th Battalion, the Burma Rifles in April that same year. Tony was transferred to the 2nd Burma Rifles at Hoshiarpur on 18th August 1942 and given the War Substantive Rank of Lieutenant as of 15th October 1942. He then commenced training with the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in preparation for Operation Longcloth.

Post Operation Longcloth, Lt. Heald was admitted to the 40th Indian Staging Section on 16th June 1943, then evacuated to 53rd Indian General Hospital located at Kohima and finally to the British Military Hospital at Shillong on the 14th August. On his immediate return from Burma in April 1943, he underwent a medical assessment in regards to an injury to his knee. The original injury was suffered during the march back (retreat) to India after the Japanese invasion of 1942. This condition was then exacerbated during the long and arduous march out through Burma to China on Operation Longcloth the following year. The medical examination board stated his disability as an internal derangement of the left knee joint and during an operation on the 17th September 1943, all cartilage was removed.

Tony spent a few weeks recuperating at BMH Rawalpindi, before his condition was re-assessed on 7th April 1944 by the Medical Board at BMH Jhansi, stating:

Patient has had a good recovery, but a month ago the knee swelled up again after a slight twist, and the patient was again admitted to hospital. Remains in Army Medical Category B.

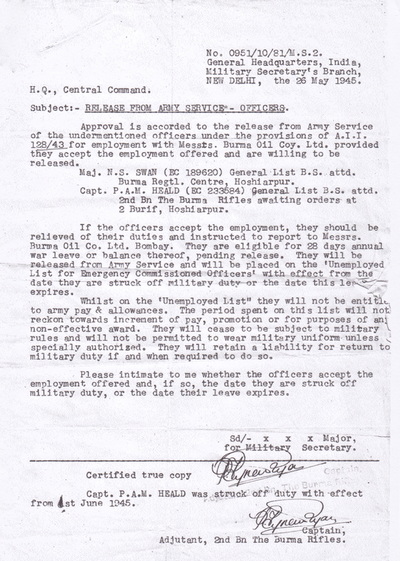

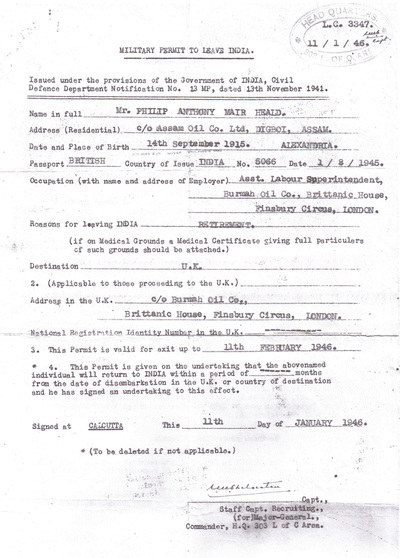

During his period in and out of hospital, Lt. Heald had become the Adjutant for the 2nd Burma Rifles and was given the rank of Acting Captain on the 1st December 1943. Captain EC 233584 P.A.M. Heald was released from Army Service on 1st June 1945 whilst the 2nd Battalion were stationed at Hoshiarpur. Tony returned to work for a short time, before resigning his position as Labour Superintendent with the Burmah Oil Company on the 12th November 1945. He was issued with a Military Permit to leave India on the grounds of his retirement from the B.O.C. and this documentation was arranged and signed off at Calcutta on the 11th January 1946.

To conclude this update, seen below is a gallery of images showing some of the documents and photographs presented to me by Jude Robinson on the 21st October 2016. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Back in October this year (2016), I was delighted to meet up with Jude and Jim Robinson at the Orange Tree public house in Richmond. After an enjoyable hour or two discussing her father's time in Burma, Jude handed me a large folder of papers and documents in relation to Tony Heald's Army Service during WW2.

Here is a brief résumé of those documents, concentrating mostly on Tony's postings, promotions and ultimately his resignation from the Burmah Oil Company in late 1945.

As with all employees of the various industries in pre-WW2 Burma, Tony Heald was encouraged to learn the Burmese language as part of his training with the B.O.C. On the 25th April 1939 he was successful in passing the Lower Standard examination and was given a one-off bonus of Rs.1000. On June 10th 1940 he enlisted into the Upper Burma Battalion Auxiliary Force, which was based at Maymyo. Here he attained his first Military service number of the war, 3032.

After attending a (3rd) Militia Course in November 1941, he joined the O.C.T.U. at Maymyo in February 1942 and was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant into the 10th Battalion, the Burma Rifles in April that same year. Tony was transferred to the 2nd Burma Rifles at Hoshiarpur on 18th August 1942 and given the War Substantive Rank of Lieutenant as of 15th October 1942. He then commenced training with the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade in preparation for Operation Longcloth.

Post Operation Longcloth, Lt. Heald was admitted to the 40th Indian Staging Section on 16th June 1943, then evacuated to 53rd Indian General Hospital located at Kohima and finally to the British Military Hospital at Shillong on the 14th August. On his immediate return from Burma in April 1943, he underwent a medical assessment in regards to an injury to his knee. The original injury was suffered during the march back (retreat) to India after the Japanese invasion of 1942. This condition was then exacerbated during the long and arduous march out through Burma to China on Operation Longcloth the following year. The medical examination board stated his disability as an internal derangement of the left knee joint and during an operation on the 17th September 1943, all cartilage was removed.

Tony spent a few weeks recuperating at BMH Rawalpindi, before his condition was re-assessed on 7th April 1944 by the Medical Board at BMH Jhansi, stating:

Patient has had a good recovery, but a month ago the knee swelled up again after a slight twist, and the patient was again admitted to hospital. Remains in Army Medical Category B.

During his period in and out of hospital, Lt. Heald had become the Adjutant for the 2nd Burma Rifles and was given the rank of Acting Captain on the 1st December 1943. Captain EC 233584 P.A.M. Heald was released from Army Service on 1st June 1945 whilst the 2nd Battalion were stationed at Hoshiarpur. Tony returned to work for a short time, before resigning his position as Labour Superintendent with the Burmah Oil Company on the 12th November 1945. He was issued with a Military Permit to leave India on the grounds of his retirement from the B.O.C. and this documentation was arranged and signed off at Calcutta on the 11th January 1946.

To conclude this update, seen below is a gallery of images showing some of the documents and photographs presented to me by Jude Robinson on the 21st October 2016. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 15/09/2020.

I was intrigued to receive two email contacts on the subject of the 36th Chinese Division and their liaison with No. 7 Column in June 1943. Firstly, from Lahn Chao who lives in Taiwan:

Greetings,

I have found a memoir from a 36th Division veteran who was responsible for escorting the 7th Column in Yunnan Province. I would like to ask if there is more detailed information or records of the 7th Column (Chindits) after they decided to go east and enter China? I am trying to piece together the history of the division by collecting together records from British, Chinese and Japanese sources.

The above email was followed shortly afterwards by a second contact, this time from Deryk Walker:

Dear Sir,

I am writing to you, on behalf of a Taiwanese colleague who is writing the history of the Chinese Nationalist 36th Division, to find out more facts about an episode that happened during Operation Longcloth in 1943. At the end of the operation, the columns split and one went into China. According to Japanese and Chinese records, the Chinese 36th Division was involved in helping and rescuing them, but I cannot, so far, find anything in British records. Would you have more information on this? Your help would be very much appreciated.

I replied to both enquiries confirming that No. 7 Column did indeed exit Burma in May-June 1943 via Yunnan Province and that there was in existence a war diary for the column that went some way in describing the unit's relationship and connection with the Chinese 36th Division. I then sent a digital copy of the diary to Deryk and asked him to pass this on to Lahn. I also expressed my own interest in the subject to hand and that I would appreciate any new information about the liaison between the two sides back then.

Lahn was kind enough to send me the following narrative on the subject:

I have read the War Diary and I found some interesting facts about the Chindits of No. 7 Column in Chinese records and memoirs, which I would like to share with you.

First of all, General Soong Si-Lian (Sung Xi-Lian, in Communist Pin-yin), the commander of 71st Army has mentioned in his memoir that about 300 to 400 Chindit commandos were air dropped behind Japanese lines, but had been discovered by Japanese forces. Thus he sent his troops to attempt a rescue mission in Japanese occupied western Yunnan. Since the 36th Division was one of the 12 divisions assigned for Operation Anakim to attack the Japanese positions from the east, and the 36th Division had been sending scouts and commandos behind the Japanese lines for many months already, they were well prepared to undertake this mission.

The 36th Division sent a commando battalion, led by Major Chang Chin-Kun across the Irrawaddy (the Anger River) and had a series of engagements with the Japanese 56th Division. The battalion was intercepted by the Japanese 113th Brigade en route, and heavy casualties were reported by the battalion. Only 6 Officers and 49 soldiers remained intact after the fight and it was these men who met the British forces in May.

A member of the irregular forces in the area noted about their activities too. By the time the Chindits arrived, there were two different Chinese partisan forces in the area. One of them was the Partisan Detachment of Lungling-Lusi, led by Ju Jia-Si, while the other was the Partisan of Charlie led by Hsieh Jin-Sheng. Both these detachments were controlled by the local Yunnan Warlord, instead of the KMT government. The 71st Army commando would gather information from them, but they rarely cooperated willingly with each other. Neither the Yunnan Warlord or the 71st Army would give the Chindits supplies, food or munitions.

Tsai Lan-hui, was a high school student and capable of speaking Japanese, she was captured as a sex slave by the Japanese but was actually a disguised partisan spy. She was so beautiful that a Japanese officer called Tanashima married her. She began to leak information to the irregular forces in the area. The Partisans received the information that the Chindits were coming and the 36th Division commandos undertook their rescue mission. The memoir does not mention whether they met No. 7 Column or not, and there were no records of them ever disarming the Chindits or receiving British weapons as suggested in the British records. This would have been a strange thing in any respect, because the Nationalist Chinese Army were using German 7.92mm Mauser Rifles and ammunition.

I would guess that it was the Partisans of Charlie who met the Chindits and disarmed them. It is a wild guess but it is reasonable, since the Partisans had no supply of weapons and had been trying all means to get guns and ammunition. Ms. Tsai Lan-hui died in 2005 and her memoir was published by her daughter. Mr. Hsieh of the Partisans did not mention any word of disarming the Chindits in his memoir either.

In further email exchanges with Lahn, I explained that my understanding of this matter was that the Chindits had willingly handed over their weapons as payment and a thank you for the outstanding hospitality they had received on their march through Yunnan.

I was intrigued to receive two email contacts on the subject of the 36th Chinese Division and their liaison with No. 7 Column in June 1943. Firstly, from Lahn Chao who lives in Taiwan:

Greetings,

I have found a memoir from a 36th Division veteran who was responsible for escorting the 7th Column in Yunnan Province. I would like to ask if there is more detailed information or records of the 7th Column (Chindits) after they decided to go east and enter China? I am trying to piece together the history of the division by collecting together records from British, Chinese and Japanese sources.

The above email was followed shortly afterwards by a second contact, this time from Deryk Walker:

Dear Sir,

I am writing to you, on behalf of a Taiwanese colleague who is writing the history of the Chinese Nationalist 36th Division, to find out more facts about an episode that happened during Operation Longcloth in 1943. At the end of the operation, the columns split and one went into China. According to Japanese and Chinese records, the Chinese 36th Division was involved in helping and rescuing them, but I cannot, so far, find anything in British records. Would you have more information on this? Your help would be very much appreciated.

I replied to both enquiries confirming that No. 7 Column did indeed exit Burma in May-June 1943 via Yunnan Province and that there was in existence a war diary for the column that went some way in describing the unit's relationship and connection with the Chinese 36th Division. I then sent a digital copy of the diary to Deryk and asked him to pass this on to Lahn. I also expressed my own interest in the subject to hand and that I would appreciate any new information about the liaison between the two sides back then.

Lahn was kind enough to send me the following narrative on the subject:

I have read the War Diary and I found some interesting facts about the Chindits of No. 7 Column in Chinese records and memoirs, which I would like to share with you.

First of all, General Soong Si-Lian (Sung Xi-Lian, in Communist Pin-yin), the commander of 71st Army has mentioned in his memoir that about 300 to 400 Chindit commandos were air dropped behind Japanese lines, but had been discovered by Japanese forces. Thus he sent his troops to attempt a rescue mission in Japanese occupied western Yunnan. Since the 36th Division was one of the 12 divisions assigned for Operation Anakim to attack the Japanese positions from the east, and the 36th Division had been sending scouts and commandos behind the Japanese lines for many months already, they were well prepared to undertake this mission.

The 36th Division sent a commando battalion, led by Major Chang Chin-Kun across the Irrawaddy (the Anger River) and had a series of engagements with the Japanese 56th Division. The battalion was intercepted by the Japanese 113th Brigade en route, and heavy casualties were reported by the battalion. Only 6 Officers and 49 soldiers remained intact after the fight and it was these men who met the British forces in May.

A member of the irregular forces in the area noted about their activities too. By the time the Chindits arrived, there were two different Chinese partisan forces in the area. One of them was the Partisan Detachment of Lungling-Lusi, led by Ju Jia-Si, while the other was the Partisan of Charlie led by Hsieh Jin-Sheng. Both these detachments were controlled by the local Yunnan Warlord, instead of the KMT government. The 71st Army commando would gather information from them, but they rarely cooperated willingly with each other. Neither the Yunnan Warlord or the 71st Army would give the Chindits supplies, food or munitions.

Tsai Lan-hui, was a high school student and capable of speaking Japanese, she was captured as a sex slave by the Japanese but was actually a disguised partisan spy. She was so beautiful that a Japanese officer called Tanashima married her. She began to leak information to the irregular forces in the area. The Partisans received the information that the Chindits were coming and the 36th Division commandos undertook their rescue mission. The memoir does not mention whether they met No. 7 Column or not, and there were no records of them ever disarming the Chindits or receiving British weapons as suggested in the British records. This would have been a strange thing in any respect, because the Nationalist Chinese Army were using German 7.92mm Mauser Rifles and ammunition.

I would guess that it was the Partisans of Charlie who met the Chindits and disarmed them. It is a wild guess but it is reasonable, since the Partisans had no supply of weapons and had been trying all means to get guns and ammunition. Ms. Tsai Lan-hui died in 2005 and her memoir was published by her daughter. Mr. Hsieh of the Partisans did not mention any word of disarming the Chindits in his memoir either.

In further email exchanges with Lahn, I explained that my understanding of this matter was that the Chindits had willingly handed over their weapons as payment and a thank you for the outstanding hospitality they had received on their march through Yunnan.

Update 12/11/2020.

I was delighted to receive further information from Lahn Chao in relation to No. 7 Column and their interaction with local Chinese Forces in 1943:

Steve, after some more searching, I have found some new evidence for No. 7 Column. The source is from Yunnan, China. On page 215 of the Teng-Chung local history book volume one, under the title Anti-Japanese Partisan Activities of Mong-Yun. I will just quote the words from this book:

The weapons of the Mong-Yun Partisan team dates back to 1924, they bought 10 Mauser rifles to fight local bandits. As the Chinese Expeditionary Forces enters Burma helping the British defending Japanese, the Mong-Yun Partisan team leader, HSU Ben-Her, organized his men and helped the Chinese Expeditionary Forces on evacuating the wounded and refugees. After Japanese took Bhamo, HSU Ben-Her met 5 British soldiers and one of them was a manager of the Burma Oil Corporation near the Chinese-Burma border. The British have 5 Lee-Enfield in their hand, and HSU told them, foreigners are not allowed to enter Chinese border with weapons without permission, thus acquired all their guns. Later, about 30 British commandos, led by Royal Officer Gilkes, were escorted by Mong-Yun Partisan to Pao-Shan to meet the 36th Division.

They did not mention where and when they meet Major Gilkes in the article, but all other details are matching. The "irregular force" is now confirmed to be Mong-Yun Partisan Team, and led by HSU Ben-Her. So I have to correct my previous information, it was not the Partisan team of Charlie who met the Chindits, but Mong-Yun's Partisan team. The previous is one of the two teams which wandered around ambushing the Japanese in the area, while the latter is more like a Home Guard or local resistance organisation. I will look up Mong-Yun for more details. "Mong" means a clearing or village in Northern Thai Chiang Mai dialect. It is possible that the Chindits were found near this village.

I was delighted to receive further information from Lahn Chao in relation to No. 7 Column and their interaction with local Chinese Forces in 1943:

Steve, after some more searching, I have found some new evidence for No. 7 Column. The source is from Yunnan, China. On page 215 of the Teng-Chung local history book volume one, under the title Anti-Japanese Partisan Activities of Mong-Yun. I will just quote the words from this book:

The weapons of the Mong-Yun Partisan team dates back to 1924, they bought 10 Mauser rifles to fight local bandits. As the Chinese Expeditionary Forces enters Burma helping the British defending Japanese, the Mong-Yun Partisan team leader, HSU Ben-Her, organized his men and helped the Chinese Expeditionary Forces on evacuating the wounded and refugees. After Japanese took Bhamo, HSU Ben-Her met 5 British soldiers and one of them was a manager of the Burma Oil Corporation near the Chinese-Burma border. The British have 5 Lee-Enfield in their hand, and HSU told them, foreigners are not allowed to enter Chinese border with weapons without permission, thus acquired all their guns. Later, about 30 British commandos, led by Royal Officer Gilkes, were escorted by Mong-Yun Partisan to Pao-Shan to meet the 36th Division.

They did not mention where and when they meet Major Gilkes in the article, but all other details are matching. The "irregular force" is now confirmed to be Mong-Yun Partisan Team, and led by HSU Ben-Her. So I have to correct my previous information, it was not the Partisan team of Charlie who met the Chindits, but Mong-Yun's Partisan team. The previous is one of the two teams which wandered around ambushing the Japanese in the area, while the latter is more like a Home Guard or local resistance organisation. I will look up Mong-Yun for more details. "Mong" means a clearing or village in Northern Thai Chiang Mai dialect. It is possible that the Chindits were found near this village.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and the Robinson family.

July 2013.