Lieutenant Robert Peter Wormell

Cap badge of the 4th Prince of Wales' Own Gurkha Rifles.

Cap badge of the 4th Prince of Wales' Own Gurkha Rifles.

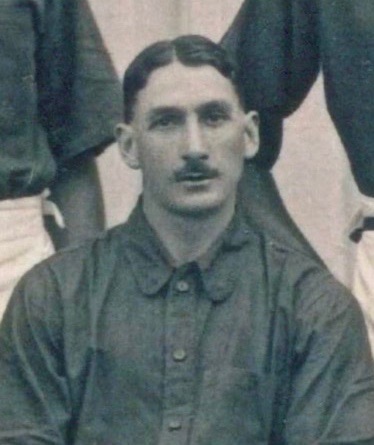

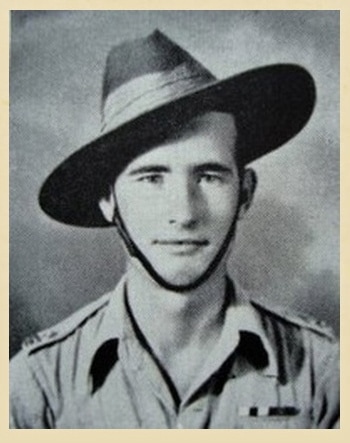

Robert Peter Wormell was born on the 30th May 1921, in the West Midlands village of Meriden. According to the pages of the London Gazette for April 1943, he was given an Emergency Commission into the Indian Army on the 15th November 1942, passing immediately from the rank of Lance Corporal to that of 2nd Lieutenant and taking up a posting into the 4th Prince of Wales' Own Gurkha Rifles.

Within one month of his promotion to 2nd Lieutenant, Wormell found himself transferred to the Gurkha battalion which was about to penetrate behind enemy lines as part of the first Chindit expedition. He was given the role of Assistant Animal Transport Officer in No. 1 Column, which was commanded by Major George Dunlop formerly of the Royal Scots. Robert is mentioned briefly in the book, the History of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles, which recounts some of his time with the Chindits in 1943, but it is upon his own written testimony, presented to the Regiment after the war, that the following story is based.

To Colonel A.L. Fell, Commandant 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

These are my personal experiences in Burma with the late Major-General Wingate’s first Chindit expedition, January-April 1943 and subsequent capture by the Japanese on April 30th 1943; by Lt. R. P. Wormell, 4th Prince of Wales’ Own Gurkha Rifles; attached 3/2 K.E.O. Gurkha Rifles.

I joined the Brigade on the 23rd December 1942 at Jhansi U.P. (Uttah Pradesh) and was attached to the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles under the command of Lt-Colonel Alexander. There were four Gurkha Columns, forming No. 1 Group, with one Company in each. I was in No.1 Column. There appeared to be a glut of officers attached from different Gurkha Regiments holding no important position in any column. I heard later that the original intention was to form a reserve of officers who were to be dropped by parachute to replace subsequent casualties. But, in the end we went in with the Brigade from the start.

There were plenty of odd jobs going and I was firstly Column Quartermaster and then later, after leaving Dimapur in Assam, became the officer in charge of Bullock Transport. After crossing the River Chindwin, I became assistant Animal Transport Officer (Mules) and then attached to No. 8 Platoon in A’ Company on the return journey as far as the Irrawaddy. Here I was put in command of a section of ten men who were sent across the river in a country boat to form a bridgehead on the west bank prior to the Column crossing over.

The expedition may be said to have started on the day we left Jhansi (11th January) for Assam. We travelled by train as far as Dimapur and after the full Brigade had assembled, left by Column for Imphal. This was the start of our long march beginning around the 22nd January. It was at Dimapur that I was given the temporary job of bringing on the bullock carts by our Column commander, Major Dunlop. After the column had left the bivouac area, the bullock transport could then proceed under it's own steam and usually arrived at the next halt, some four hours after the column had ‘turned in.’ The pace of these animals was very slow and consequently tiring and naturally enough I was quite pleased when we left the bullocks altogether on the west bank of the Chindwin.

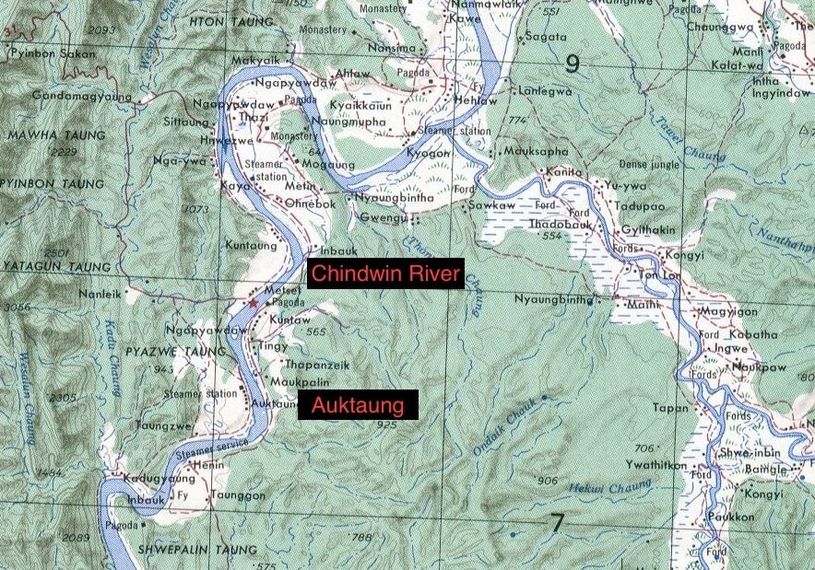

We arrived at Imphal about January 31st, after about nine days marching and then rested up until February 6th. After final conferences with the Brigadier held at the local Golf course club house and an inspection by General Wavell, we then set off for Tamu, arriving on the 11th February. We then drew three days hard rations and left on the following morning. The Column went ahead to Auktaung and I was just starting out with the bullocks, when the Brigadier appeared at the side of the track and wished me good luck and went on to tell me, that if I managed to reach Auktaung by the 14th February I would have done my job. It was the first and last time Wingate spoke to me personally and I never saw him again.

The first 16 miles were alright, but at the 17th milestone we were forced to leave the carts, loading all the important equipment on to the animals’ backs. The track had now become very narrow with a sheer drop on the right hand side. We carried on steadily and arrived at Auktaung on the afternoon of the 14th. We drew rations for ten days and received our mail. No. 1 Group had also received their first supply drop.

At dusk we marched down to the river bank. It was getting light again by the time we were all over on the east bank, with the mules being the cause of the delay. Our crossing was partially protected by the men of the Patiala State Forces, who had formed a bridgehead on the east bank. There was no sign of the Japanese and we marched clear of the bank and made our first bivouac a few miles into the jungle and rested until evening. I was now appointed assistant ATO under Lt. John Fowler. Altogether we had about 120 mules, which included 70 in the second-line baggage section. I became officer in charge of the second-line and was also responsible for the inspection and care of any sick animals.

Within one month of his promotion to 2nd Lieutenant, Wormell found himself transferred to the Gurkha battalion which was about to penetrate behind enemy lines as part of the first Chindit expedition. He was given the role of Assistant Animal Transport Officer in No. 1 Column, which was commanded by Major George Dunlop formerly of the Royal Scots. Robert is mentioned briefly in the book, the History of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles, which recounts some of his time with the Chindits in 1943, but it is upon his own written testimony, presented to the Regiment after the war, that the following story is based.

To Colonel A.L. Fell, Commandant 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

These are my personal experiences in Burma with the late Major-General Wingate’s first Chindit expedition, January-April 1943 and subsequent capture by the Japanese on April 30th 1943; by Lt. R. P. Wormell, 4th Prince of Wales’ Own Gurkha Rifles; attached 3/2 K.E.O. Gurkha Rifles.

I joined the Brigade on the 23rd December 1942 at Jhansi U.P. (Uttah Pradesh) and was attached to the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles under the command of Lt-Colonel Alexander. There were four Gurkha Columns, forming No. 1 Group, with one Company in each. I was in No.1 Column. There appeared to be a glut of officers attached from different Gurkha Regiments holding no important position in any column. I heard later that the original intention was to form a reserve of officers who were to be dropped by parachute to replace subsequent casualties. But, in the end we went in with the Brigade from the start.

There were plenty of odd jobs going and I was firstly Column Quartermaster and then later, after leaving Dimapur in Assam, became the officer in charge of Bullock Transport. After crossing the River Chindwin, I became assistant Animal Transport Officer (Mules) and then attached to No. 8 Platoon in A’ Company on the return journey as far as the Irrawaddy. Here I was put in command of a section of ten men who were sent across the river in a country boat to form a bridgehead on the west bank prior to the Column crossing over.

The expedition may be said to have started on the day we left Jhansi (11th January) for Assam. We travelled by train as far as Dimapur and after the full Brigade had assembled, left by Column for Imphal. This was the start of our long march beginning around the 22nd January. It was at Dimapur that I was given the temporary job of bringing on the bullock carts by our Column commander, Major Dunlop. After the column had left the bivouac area, the bullock transport could then proceed under it's own steam and usually arrived at the next halt, some four hours after the column had ‘turned in.’ The pace of these animals was very slow and consequently tiring and naturally enough I was quite pleased when we left the bullocks altogether on the west bank of the Chindwin.

We arrived at Imphal about January 31st, after about nine days marching and then rested up until February 6th. After final conferences with the Brigadier held at the local Golf course club house and an inspection by General Wavell, we then set off for Tamu, arriving on the 11th February. We then drew three days hard rations and left on the following morning. The Column went ahead to Auktaung and I was just starting out with the bullocks, when the Brigadier appeared at the side of the track and wished me good luck and went on to tell me, that if I managed to reach Auktaung by the 14th February I would have done my job. It was the first and last time Wingate spoke to me personally and I never saw him again.

The first 16 miles were alright, but at the 17th milestone we were forced to leave the carts, loading all the important equipment on to the animals’ backs. The track had now become very narrow with a sheer drop on the right hand side. We carried on steadily and arrived at Auktaung on the afternoon of the 14th. We drew rations for ten days and received our mail. No. 1 Group had also received their first supply drop.

At dusk we marched down to the river bank. It was getting light again by the time we were all over on the east bank, with the mules being the cause of the delay. Our crossing was partially protected by the men of the Patiala State Forces, who had formed a bridgehead on the east bank. There was no sign of the Japanese and we marched clear of the bank and made our first bivouac a few miles into the jungle and rested until evening. I was now appointed assistant ATO under Lt. John Fowler. Altogether we had about 120 mules, which included 70 in the second-line baggage section. I became officer in charge of the second-line and was also responsible for the inspection and care of any sick animals.

Lt. Wormell continues:

The following morning we bumped into a platoon of the enemy whilst passing close to a village. One of our platoons engaged the Japanese, whilst the rest of the column undertook second drill dispersal. Lt. Richard Scamander Clarke took command of our group and next day we contacted No. 1 Group HQ and No. 2 Column. We remained with them for a few days march before finally re-joining the rest of No. 1 Column. The platoon which had engaged the Japanese had broken off from the battle after inflicting several casualties on the enemy and had now caught up with the rest of the group. We crossed the escarpment and had our second supply dropping ten days after crossing the Chindwin. We were supplied short, only receiving half the quantity asked for. We had to make do on half rations for the next twelve days until we had crossed the Irrawaddy.

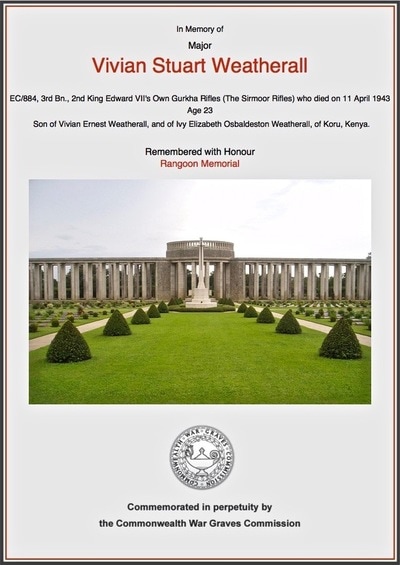

Between the escarpment and the Irrawaddy was our target; the railway line which runs between Myitkhina and Mandalay. Our job was to blow up a bridge north of Kawlin (Kyaikthin) and then proceed to the Irrawaddy. The Commando Section under Lt. John Nealon accomplished this task whilst being covered by a platoon led by Captain Vivian Weatherall. Southern Group HQ and No. 2 Column had left us during the last supply drop and were a few miles further south. Their attack on the railway was thwarted by the Japanese, who surprised them just before their own attack was to begin. No. 2 Column split up, with half returning to the Chindwin, whilst the remainder, including Group HQ joined up with us several days later and continued with us for the rest of the campaign.

NB. After Southern Group had crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February, their orders were to march toward the rail station at Kyaikthin. They were in effect acting as a decoy for the other Chindit columns moving to the north of us and marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must surely have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. On the 2nd March, Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin; Major Dunlop was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst 2 Column under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Group Head Quarters were to head on towards the rail station itself.

What neither group realised was that the Japanese were by now closing in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had now lost radio contact with one another. 2 Column and Group Head Quarters, in the black of night stumbled into an enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment. After several hours of hand to hand fighting, Colonel Alexander and his Group HQ, along with some men from 2 Column, extracted themselves from the engagement and headed east towards the Irrawaddy.

Lt. Wormell's memoir continues:

Our (1 Column) Irrawaddy crossing was uneventful, except for the loss of two or three horses and the visit of a Zero aircraft, which dropped pamphlets asking the Gurkhas to desert the Column and join the I.N.A. We crossed over near Tagaung and had a night time supply drop on the east bank of the river, resulting in three days rations and then another drop about 20 miles further east. We had not come across any Japanese since our first day over the Chindwin.

We had what proved to be our last supply dropping five days later just a few miles east of the previous one. We asked for ten days rations which was the most a man could carry at any one time. It was as well we did, because after this had gone we survived on at best, two meals of rice per day for the next month and more often than not, on nothing at all. We had received no definite orders from Brigade HQ, except to remain in the general area north west of Mong Mit. This we did, moving a few miles in different directions each day in order to keep the Japanese off our tracks.

The mules had begun to show signs of wear and tear; they had stood the going magnificently having crossed two very wide rivers and done some pretty hard marching with little rest. Their food for the remainder of the expedition was to be bamboo shoots. Previously, grain had been dropped for them when we received our own ration drops, but only four days’ supply was possible at one time, owing to the amounts required.

At last we received orders to march out of Burma, firstly by contacting the Kachin Levies who would guide us out north around Myitkhina. We marched east to the River Shweli, but our Recce patrols reported the river was too difficult to cross. This persuaded our C.O. (Alexander) to head south west around Mong Mit and up into the hills, hoping to strike the Shweli again, where it runs east to west. It was from this point that things became more and more of a strain. We made the hills alright but were soon harassed in our rear by a Japanese patrol. Eventually, in order to get along faster, all the mules were left behind, except those carrying the RAF wireless, mortars and machine guns. The climbing was becoming more difficult, almost sheer in places and we had to contact the Levies before the end of March, which seemed an impossible task as it was now March 27th.

On the morning after leaving the mules, we were just preparing to move off when our Perimeter Platoon spotted some Japanese coming up the hill on which we were camped. We managed to drive them away with some well-aimed 3” mortar bombs, but not before a two hour battle had taken place. It was very much in our interest to lose this enemy patrol, so that we could cross the Mong Mit-Mogok motor road to the east of our position. In order to facilitate this we dispensed with the remainder of our mules and all other heavy equipment, including our mortars and wireless set. We now resembled an infantry company of formidable strength, some 450 men, added to which we still had our Burma Rifle and Commando sections.

We crossed the road the following night without incident and made our way up into the hills. From then on we marched up and down many hills for the next eight or nine days, moving north towards the Shweli River. Our rations from the last supply drop were just about finished and we had to rely on villages for rice and anything else we could get. This proved very difficult due to the large number of mouths to feed.

By the time we reached the Shweli it was too late to contact the Kachin Levies and so we tested the river in several place for a crossing point.

The current was strong and the river deep and it was slow work getting our groups across. The Burma Rifles went over first, when suddenly fire was opened up from the far bank by a Japanese patrol. The crossing was abandoned and those already on the far bank managed to get back to our side again. As we marched away along the bank more fire came in on us and so we retired south on to a hill and took up a defensive position.

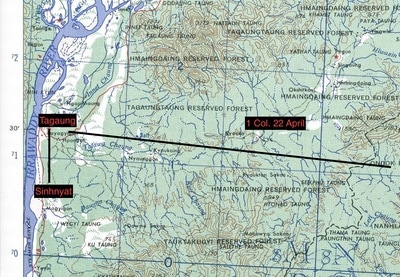

It was noticed that our rear platoon had not caught up with us and Captain Weatherall went back, against orders, to locate them. In passing close to the river bank, he was spotted from the other side and a burst of machine gun fire hit him. A patrol was sent back to look for him and returned to report that he was fatally wounded and could not be moved. Meanwhile, the rear platoon under Lt. Fowler had made a detour and managed to re-join the column. It was then decided that a crossing would now be impracticable, so we headed south west towards the Irrawaddy. We reached the river on the 21st April, only to discover that all boats had been seized by the Japanese. This was at Tagaung, but on marching a few miles further south, close to the village of Sinhnyat, we managed to procure two country boats which could hold twelve and twenty men respectively.

Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to this story, including a map of the area around Sinhnyat on the Irrawaddy. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The following morning we bumped into a platoon of the enemy whilst passing close to a village. One of our platoons engaged the Japanese, whilst the rest of the column undertook second drill dispersal. Lt. Richard Scamander Clarke took command of our group and next day we contacted No. 1 Group HQ and No. 2 Column. We remained with them for a few days march before finally re-joining the rest of No. 1 Column. The platoon which had engaged the Japanese had broken off from the battle after inflicting several casualties on the enemy and had now caught up with the rest of the group. We crossed the escarpment and had our second supply dropping ten days after crossing the Chindwin. We were supplied short, only receiving half the quantity asked for. We had to make do on half rations for the next twelve days until we had crossed the Irrawaddy.

Between the escarpment and the Irrawaddy was our target; the railway line which runs between Myitkhina and Mandalay. Our job was to blow up a bridge north of Kawlin (Kyaikthin) and then proceed to the Irrawaddy. The Commando Section under Lt. John Nealon accomplished this task whilst being covered by a platoon led by Captain Vivian Weatherall. Southern Group HQ and No. 2 Column had left us during the last supply drop and were a few miles further south. Their attack on the railway was thwarted by the Japanese, who surprised them just before their own attack was to begin. No. 2 Column split up, with half returning to the Chindwin, whilst the remainder, including Group HQ joined up with us several days later and continued with us for the rest of the campaign.

NB. After Southern Group had crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February, their orders were to march toward the rail station at Kyaikthin. They were in effect acting as a decoy for the other Chindit columns moving to the north of us and marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must surely have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. On the 2nd March, Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin; Major Dunlop was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst 2 Column under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Group Head Quarters were to head on towards the rail station itself.

What neither group realised was that the Japanese were by now closing in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had now lost radio contact with one another. 2 Column and Group Head Quarters, in the black of night stumbled into an enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment. After several hours of hand to hand fighting, Colonel Alexander and his Group HQ, along with some men from 2 Column, extracted themselves from the engagement and headed east towards the Irrawaddy.

Lt. Wormell's memoir continues:

Our (1 Column) Irrawaddy crossing was uneventful, except for the loss of two or three horses and the visit of a Zero aircraft, which dropped pamphlets asking the Gurkhas to desert the Column and join the I.N.A. We crossed over near Tagaung and had a night time supply drop on the east bank of the river, resulting in three days rations and then another drop about 20 miles further east. We had not come across any Japanese since our first day over the Chindwin.

We had what proved to be our last supply dropping five days later just a few miles east of the previous one. We asked for ten days rations which was the most a man could carry at any one time. It was as well we did, because after this had gone we survived on at best, two meals of rice per day for the next month and more often than not, on nothing at all. We had received no definite orders from Brigade HQ, except to remain in the general area north west of Mong Mit. This we did, moving a few miles in different directions each day in order to keep the Japanese off our tracks.

The mules had begun to show signs of wear and tear; they had stood the going magnificently having crossed two very wide rivers and done some pretty hard marching with little rest. Their food for the remainder of the expedition was to be bamboo shoots. Previously, grain had been dropped for them when we received our own ration drops, but only four days’ supply was possible at one time, owing to the amounts required.

At last we received orders to march out of Burma, firstly by contacting the Kachin Levies who would guide us out north around Myitkhina. We marched east to the River Shweli, but our Recce patrols reported the river was too difficult to cross. This persuaded our C.O. (Alexander) to head south west around Mong Mit and up into the hills, hoping to strike the Shweli again, where it runs east to west. It was from this point that things became more and more of a strain. We made the hills alright but were soon harassed in our rear by a Japanese patrol. Eventually, in order to get along faster, all the mules were left behind, except those carrying the RAF wireless, mortars and machine guns. The climbing was becoming more difficult, almost sheer in places and we had to contact the Levies before the end of March, which seemed an impossible task as it was now March 27th.

On the morning after leaving the mules, we were just preparing to move off when our Perimeter Platoon spotted some Japanese coming up the hill on which we were camped. We managed to drive them away with some well-aimed 3” mortar bombs, but not before a two hour battle had taken place. It was very much in our interest to lose this enemy patrol, so that we could cross the Mong Mit-Mogok motor road to the east of our position. In order to facilitate this we dispensed with the remainder of our mules and all other heavy equipment, including our mortars and wireless set. We now resembled an infantry company of formidable strength, some 450 men, added to which we still had our Burma Rifle and Commando sections.

We crossed the road the following night without incident and made our way up into the hills. From then on we marched up and down many hills for the next eight or nine days, moving north towards the Shweli River. Our rations from the last supply drop were just about finished and we had to rely on villages for rice and anything else we could get. This proved very difficult due to the large number of mouths to feed.

By the time we reached the Shweli it was too late to contact the Kachin Levies and so we tested the river in several place for a crossing point.

The current was strong and the river deep and it was slow work getting our groups across. The Burma Rifles went over first, when suddenly fire was opened up from the far bank by a Japanese patrol. The crossing was abandoned and those already on the far bank managed to get back to our side again. As we marched away along the bank more fire came in on us and so we retired south on to a hill and took up a defensive position.

It was noticed that our rear platoon had not caught up with us and Captain Weatherall went back, against orders, to locate them. In passing close to the river bank, he was spotted from the other side and a burst of machine gun fire hit him. A patrol was sent back to look for him and returned to report that he was fatally wounded and could not be moved. Meanwhile, the rear platoon under Lt. Fowler had made a detour and managed to re-join the column. It was then decided that a crossing would now be impracticable, so we headed south west towards the Irrawaddy. We reached the river on the 21st April, only to discover that all boats had been seized by the Japanese. This was at Tagaung, but on marching a few miles further south, close to the village of Sinhnyat, we managed to procure two country boats which could hold twelve and twenty men respectively.

Seen below is a Gallery of images in relation to this story, including a map of the area around Sinhnyat on the Irrawaddy. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Robert Wormell's memoir continues:

At 1600 hours on the 22nd April, I went across the Irrawaddy with ten Gurkhas from No. 9 Platoon. I was previously attached to No. 8 Platoon, so I was unacquainted with these fellows, except for Havildar Merbir Pun and Naik Chandra Singh. My orders were to form a bridgehead after patrolling the west bank to ensure there were no Japanese in the vicinity. My main concern was to get the patrolling done as quickly as possible, so that I could get the men into position to cover the crossing by the rest of the column which was due at 1900 hours. Our boat crossed without any trouble and I split the section in half; the Havildar and four men were to patrol north for 300 yards, while I headed south for the same distance with the rest of the men.

On returning to the rendezvous point, my party waited for the other men to put in an appearance, but after half-an-hour there was still no sign of them and so I walked a few yards in the direction they had taken. On pushing through some undergrowth I came face to face with a Japanese soldier about fifteen yards away, he was holding his rifle across his body, I also spotted other enemy soldiers screened by bushes in various positions. I withdrew out of sight and heard him call on me to stop, but deciding against this I started to run back to my patrol, which was waiting a few yards back. The Japanese opened up with grenades and automatic fire, but as far as I could tell no one was hit.

My party had deployed into the jungle immediately and I did not find them again. For some strange reason the Japanese did not follow up. I waited on the bank until 2300 hours for the column to cross, but saw no sign of them and concluded that they had decided against it. My orders were to proceed towards the Chindwin if anything went wrong, so I set out straight away. I had no map and I had lost my pack and hat, but using my compass I marched North West and hoped for the best; I knew that it was roughly 130 miles from where I was standing to the village of Auktaung on the Chindwin.

NB. Nothing more was heard of Havildar Merbir Pun, however this soldier does not feature in any missing in action files, POW lists, or on any casualty rolls for the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles. Could it be that he actually escaped capture on the 22nd April and made his own way back to India that year? Sadly, Naik Chandra Singh does feature in the casualty rolls for the battalion and was probably killed on, or shortly after the 22nd April 1943.

Lt. Wormell concludes:

From this time onward I counted eight days before I was captured and during that period I was completely alone except for two vultures which constantly circled above me. They used to roost in the trees above me during the night and started off at the same time as I did in the morning.

I remember that it tickled my sense of humour, thinking that they could not be as hungry as I was, else they would not have waited for me to snuff it.

I kept clear of all villages and tracks and in doing so had to go without food gained from any village. I had a small amount of rice grain which I soaked in water before eating. I had no matches and so was unable to cook any food, although I did once use a burning ember from a recent forest fire to heat up some of my rice grains. I remember that was on the 24th April, but from then on until the evening of the 30th, I was without food.

During the whole of my journey from the Irrawaddy to the place of my capture, just 13 miles from the Chindwin, I saw no sign of humanity. For three days (26-29th April) I paddled through a chaung with sheer cliffs on either side. No tracks were visible apart from those left by a tiger, which I followed for the whole three days. I learned later that Lt. Nealon and his Commando Section had also passed this way and seeing my footprints and the tracks, had been laying bets as to whether the tiger was following me or vice-versa. These fellows were taken prisoner about a week after myself.

Further details of my journey I cannot clearly remember. The sun was very hot and I had no hat, but somehow or other I avoided getting sun-stroke. The afternoon after leaving the chaung, I stumbled into a section of Japanese, who were with hindsight, the means of saving my life because I’d very nearly had it by this time. It was four months before I finally arrived in Rangoon, after being held in camps at Kalewa, Kalaw and Maymyo. I was released two years almost to the day after being captured, on the 29th April 1945.

At 1600 hours on the 22nd April, I went across the Irrawaddy with ten Gurkhas from No. 9 Platoon. I was previously attached to No. 8 Platoon, so I was unacquainted with these fellows, except for Havildar Merbir Pun and Naik Chandra Singh. My orders were to form a bridgehead after patrolling the west bank to ensure there were no Japanese in the vicinity. My main concern was to get the patrolling done as quickly as possible, so that I could get the men into position to cover the crossing by the rest of the column which was due at 1900 hours. Our boat crossed without any trouble and I split the section in half; the Havildar and four men were to patrol north for 300 yards, while I headed south for the same distance with the rest of the men.

On returning to the rendezvous point, my party waited for the other men to put in an appearance, but after half-an-hour there was still no sign of them and so I walked a few yards in the direction they had taken. On pushing through some undergrowth I came face to face with a Japanese soldier about fifteen yards away, he was holding his rifle across his body, I also spotted other enemy soldiers screened by bushes in various positions. I withdrew out of sight and heard him call on me to stop, but deciding against this I started to run back to my patrol, which was waiting a few yards back. The Japanese opened up with grenades and automatic fire, but as far as I could tell no one was hit.

My party had deployed into the jungle immediately and I did not find them again. For some strange reason the Japanese did not follow up. I waited on the bank until 2300 hours for the column to cross, but saw no sign of them and concluded that they had decided against it. My orders were to proceed towards the Chindwin if anything went wrong, so I set out straight away. I had no map and I had lost my pack and hat, but using my compass I marched North West and hoped for the best; I knew that it was roughly 130 miles from where I was standing to the village of Auktaung on the Chindwin.

NB. Nothing more was heard of Havildar Merbir Pun, however this soldier does not feature in any missing in action files, POW lists, or on any casualty rolls for the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles. Could it be that he actually escaped capture on the 22nd April and made his own way back to India that year? Sadly, Naik Chandra Singh does feature in the casualty rolls for the battalion and was probably killed on, or shortly after the 22nd April 1943.

Lt. Wormell concludes:

From this time onward I counted eight days before I was captured and during that period I was completely alone except for two vultures which constantly circled above me. They used to roost in the trees above me during the night and started off at the same time as I did in the morning.

I remember that it tickled my sense of humour, thinking that they could not be as hungry as I was, else they would not have waited for me to snuff it.

I kept clear of all villages and tracks and in doing so had to go without food gained from any village. I had a small amount of rice grain which I soaked in water before eating. I had no matches and so was unable to cook any food, although I did once use a burning ember from a recent forest fire to heat up some of my rice grains. I remember that was on the 24th April, but from then on until the evening of the 30th, I was without food.

During the whole of my journey from the Irrawaddy to the place of my capture, just 13 miles from the Chindwin, I saw no sign of humanity. For three days (26-29th April) I paddled through a chaung with sheer cliffs on either side. No tracks were visible apart from those left by a tiger, which I followed for the whole three days. I learned later that Lt. Nealon and his Commando Section had also passed this way and seeing my footprints and the tracks, had been laying bets as to whether the tiger was following me or vice-versa. These fellows were taken prisoner about a week after myself.

Further details of my journey I cannot clearly remember. The sun was very hot and I had no hat, but somehow or other I avoided getting sun-stroke. The afternoon after leaving the chaung, I stumbled into a section of Japanese, who were with hindsight, the means of saving my life because I’d very nearly had it by this time. It was four months before I finally arrived in Rangoon, after being held in camps at Kalewa, Kalaw and Maymyo. I was released two years almost to the day after being captured, on the 29th April 1945.

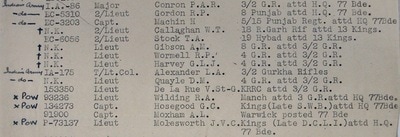

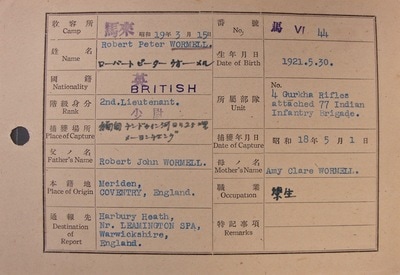

According to the information recorded on Lt. Wormell's POW index card, he was captured at Maingnyaung, a village close to the east banks of the Chindwin River on the 1st May 1943. The village was just a few short miles south-east of Auktaung, the original crossing place for 1 Column in February that year; Robert was in effect re-tracing the column's outbound journey.

The remainder of 1 Column did succeed in crossing the Irrawaddy on or around the 22nd April, however, the crossing was compromised with an enemy ambush inflicting many casualties upon the beleaguered Gurkha unit. A few days later on the 28th April, whilst attempting to cross the Mu River, Colonel Alexander was tragically killed by enemy mortar fire. Major Dunlop and the remnants of No. 1 Column finally reached the safety of Allied held territory during the second week of May.

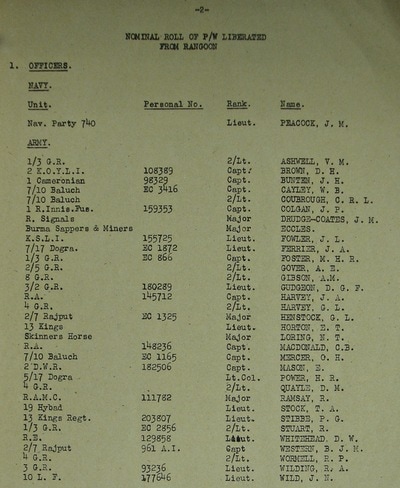

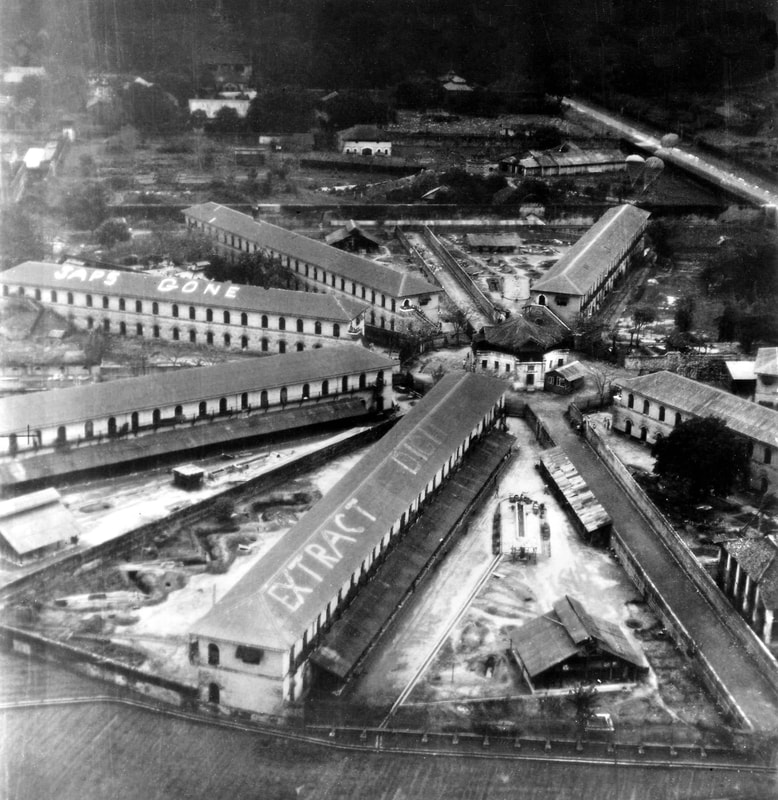

As already mentioned by Robert Wormell in his narrative, he did not arrive at Rangoon Central Jail until late August 1943. As was the norm for captured officers, he was immediately placed into solitary confinement and suffered a long and arduous period of interrogation. Some five weeks later, he finally joined his fellow Chindit captives in Block 3 of the prison. To read more about Chindit prisoners of war and their experiences inside Rangoon Jail, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

Robert Peter Wormell was liberated, along with some 400 other men from Rangoon Jail on the 29th April 1945. He and his comrades had been marched out of the jail a few days earlier, in the company of their Japanese guards as they attempted to withdraw across the border into Thailand. The senior Japanese officer decided that the prisoners were holding up his advance south and released the captives at a Burmese village called Waw, situated close to the Pegu Road. After some anxious and decidedly perilous hours, which included having to avoid instances of 'friendly fire' from the RAF, the prisoners were finally picked up by a company of soldiers from the West Yorkshire Regiment. The men were flown back to India aboard USAAF Dakotas and sent to hospital in Calcutta. After treatment for malnutrition and multiple other ailments, most of the men were directed back to their original units. Presumably, after being processed as a returning POW and a period of recuperation, Lt. Wormell was sent back to the Regimental Centre for the 4th Gurkha Rifles at Bakloh in Northern India.

Seen below is a final Gallery of images in relation to this story, including the POW index card for Robert Wormell. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The remainder of 1 Column did succeed in crossing the Irrawaddy on or around the 22nd April, however, the crossing was compromised with an enemy ambush inflicting many casualties upon the beleaguered Gurkha unit. A few days later on the 28th April, whilst attempting to cross the Mu River, Colonel Alexander was tragically killed by enemy mortar fire. Major Dunlop and the remnants of No. 1 Column finally reached the safety of Allied held territory during the second week of May.

As already mentioned by Robert Wormell in his narrative, he did not arrive at Rangoon Central Jail until late August 1943. As was the norm for captured officers, he was immediately placed into solitary confinement and suffered a long and arduous period of interrogation. Some five weeks later, he finally joined his fellow Chindit captives in Block 3 of the prison. To read more about Chindit prisoners of war and their experiences inside Rangoon Jail, please click on the following link: Chindit POW's

Robert Peter Wormell was liberated, along with some 400 other men from Rangoon Jail on the 29th April 1945. He and his comrades had been marched out of the jail a few days earlier, in the company of their Japanese guards as they attempted to withdraw across the border into Thailand. The senior Japanese officer decided that the prisoners were holding up his advance south and released the captives at a Burmese village called Waw, situated close to the Pegu Road. After some anxious and decidedly perilous hours, which included having to avoid instances of 'friendly fire' from the RAF, the prisoners were finally picked up by a company of soldiers from the West Yorkshire Regiment. The men were flown back to India aboard USAAF Dakotas and sent to hospital in Calcutta. After treatment for malnutrition and multiple other ailments, most of the men were directed back to their original units. Presumably, after being processed as a returning POW and a period of recuperation, Lt. Wormell was sent back to the Regimental Centre for the 4th Gurkha Rifles at Bakloh in Northern India.

Seen below is a final Gallery of images in relation to this story, including the POW index card for Robert Wormell. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, February 2017.