Major George Bromhead and 4 Column

George Bromhead and Wingate discuss Operation Longcloth

George Bromhead and Wingate discuss Operation Longcloth

On Operation Longcloth, Mike Calvert once sent me a ciphered evening map location which read, "Alas no paddle." Looking at my map, I was pleased to find a place called 'Shit Chaung.' (George Bromhead 12th March 1995).

Robert Benjamin Gonville Bromhead was born on the 26th December 1913, known as George, he was a relation of Major Gonville Bromhead VC of Rorke's Drift fame. George served originally and latterly with the Royal Berkshire Regiment in an Army career which spanned over thirty years.

In the summer of 1942, whilst serving in New Delhi with India Command, George renewed his acquaintance with Orde Wingate and became Brigade-Major for Wingate's fledgling Chindit Brigade.

In February 1995 (sadly also the year of his death aged 81) he told the author Philip Chinnery:

I first knew Wingate in 1936 during the Palestine rebellion. I was an Intelligence Officer and as the rebellion continued and units were added to the Brigade we began to look like a division. Eventually a Division HQ was sent from England to take over and Wingate was the Intelligence Staff Officer. The next time we met was in New Delhi six years later. I was doing a temporary staff job at GHQ. One day down a passage came a slightly untidy figure wearing a Wolseley helmet instead of the more normal topee. This I later knew was Wingate's trademark.

The figure greeted me with 'Just the sort of chap I am looking for, I need a Brigade Major.' My temporary staff job was nearly complete, so my boss let me go and there I was. Wingate explained that he had been running guerrilla operations behind Italian lines in Ethiopia, now finished since the enemy had packed in. Wavell had sent for him to do a similar job behind Jap lines in the jungle. Thus was 77 Indian Infantry Brigade formed.

This included a British battalion raised for defence in the United Kingdom and sent to India for peacekeeping and, on average, rather old for their new role. So we had the unenviable task of sorting out the older members. A Gurkha battalion rather too young. There are no birth certificates in Nepal! Lastly, a Burmese battalion which had previous experience in the retreat through Burma. One of their Majors, who was left out because of age, I met in a hotel in Delhi. 'What are you doing here?' I said. 'A bit of leave before I go back to Rangoon. Yes, I walk. You see I am working for Intelligence and every few weeks I have to walk across Burma to report and I take a spot of leave in a comfortable hotel.' And we left him out for reason of age!

Two incidents stand out in my mind during jungle training. First, an early monsoon was drumming on my office tent and the flies were sagging. Approaching through the mud came a pair of bare feet; as they came nearer a pair of naked knees appeared, and then some more naked body and finally Wingate crouched under the tent flies — wearing his Wolseley helmet and nothing else!

Second, the river where the Gurkha unit was camped started to rise and we were out of touch. Nothing for it, I had to swim through the flooded water to make contact. It was a nightmare. Every animal which could swim was in the water with me. I could rest by holding the branches of trees which was what the snakes were doing. An alligator gave me a dirty look. But it ended happily. The Gurkhas had taken to the trees and were safe if not happy, and the water went down quite quickly.

Wingate had a convenient theory about official correspondence: if left in the pending tray, most of it answered itself. If really important a reminder would follow and that was the time to reply. Sponsored by Wavell, he had of course the ear of all the heads of department in Delhi. However, he didn't understand the Indian bureaucracy and didn't want to, so every time he visited Delhi I had to nip up next day to get the results in black and white and signed. I didn't mind, I knew the system and had a girlfriend there.

George Bromhead took up his position as Brigade-Major at the Chindit training camp in Saugor, where he assisted Wingate with his operational planning for the first expedition into Burma. After Operation Longcloth, Bromhead sat down and wrote out his debrief notes and thoughts on the operation. These notes included his views on the experimental use of air supply in 1943, which in his opinion was perhaps the greatest success of the whole affair.

He remarked upon the haphazard nature of the training regime for Longcloth and the unsuitable nature of the 13th King's as infantry troops. However, he qualified this position by stating that the men who eventually entered Burma in February 1943 performed admirably and gave a good account of themselves. Equipment and supplies were another area of concern in his debrief paper, with items such as the wireless and radio sets coming under severe criticism for both their size and indeed performance in jungle conditions.

He comments on the positive effect of Operation Longcloth on the morale of the Allied troops back in the CBI theatre and for the British public back home. He states that: "the achievements of this small force were far out of proportion to its size. Its presence halting the Japanese offensive against Fort Hertz in the north of Burma when the railway was cut and the push against the Chinese across the Salween being severely hindered and enemy troops withdrawn from this front to deal with our incursion."

Bromhead congratulates his Brigadier on the use of the Burma Rifles in the campaign. He realises the critical importance of their local knowledge, field-craft and the essential advantage of winning the hearts and minds of the people, through whose country you are travelling. He applauds the use of the seven Chindit columns, spreading them over a wide enough area so as to ensure their individual security, but not so far apart that they became adrift and could if necessary come to each others aid.

Other groups to be praised in the report were the Commandos and the RAF liaison officers, who in Bromhead's opinion were the "most enthusiastic and toughest section of men that any commander in the field could have wanted." The quality and nutritional value of the rations for Operation Longcloth came under scrutiny in the report. The conclusion was that the calorific value of the rations, set at around 3000 calories per man per day and supplemented by another 1000 calories a day from local villages, was not nearly enough for a prolonged campaign over several months. In Bromhead's view, this undoubtedly caused fatigue and starvation amongst the troops, especially the British contingent and this in the end added significantly to the final casualty figures.

On the subject of casualties, the report touches on the negative effect on morale of having to leave wounded or sick men behind in the jungle. Also mentioned, was the lack of medicines available to the medical officers serving in each column, although the performance of these men is praised by Bromhead, stating that: "the medical officers on Longcloth, although not overladen with medicines found ways around certain difficulties and abundantly repaid the faith the men placed upon them."

The importance of morale is emphasised in the report time and again, but in the end according to Major Bromhead comes down to one single factor, that of confidence. He states in his paper: "confidence is vital, confidence of each soldier in his own abilities to fight and exist in the jungle, confidence in his leaders, confidence in those who are planning for him and feeding him, confidence in his weapons, but above all confidence in himself."

George Bromhead concluded in his report that: "The operations in 1943 were essentially experimental, but proved far more successful than the average soldier had expected. On these efforts were laid the basis of larger scale operations the following year, when more of the right equipment was available and when the forces for the most part entered Burma in gliders and thus overcame the problem of fatigue in reaching their initial objectives."

Robert Benjamin Gonville Bromhead was born on the 26th December 1913, known as George, he was a relation of Major Gonville Bromhead VC of Rorke's Drift fame. George served originally and latterly with the Royal Berkshire Regiment in an Army career which spanned over thirty years.

In the summer of 1942, whilst serving in New Delhi with India Command, George renewed his acquaintance with Orde Wingate and became Brigade-Major for Wingate's fledgling Chindit Brigade.

In February 1995 (sadly also the year of his death aged 81) he told the author Philip Chinnery:

I first knew Wingate in 1936 during the Palestine rebellion. I was an Intelligence Officer and as the rebellion continued and units were added to the Brigade we began to look like a division. Eventually a Division HQ was sent from England to take over and Wingate was the Intelligence Staff Officer. The next time we met was in New Delhi six years later. I was doing a temporary staff job at GHQ. One day down a passage came a slightly untidy figure wearing a Wolseley helmet instead of the more normal topee. This I later knew was Wingate's trademark.

The figure greeted me with 'Just the sort of chap I am looking for, I need a Brigade Major.' My temporary staff job was nearly complete, so my boss let me go and there I was. Wingate explained that he had been running guerrilla operations behind Italian lines in Ethiopia, now finished since the enemy had packed in. Wavell had sent for him to do a similar job behind Jap lines in the jungle. Thus was 77 Indian Infantry Brigade formed.

This included a British battalion raised for defence in the United Kingdom and sent to India for peacekeeping and, on average, rather old for their new role. So we had the unenviable task of sorting out the older members. A Gurkha battalion rather too young. There are no birth certificates in Nepal! Lastly, a Burmese battalion which had previous experience in the retreat through Burma. One of their Majors, who was left out because of age, I met in a hotel in Delhi. 'What are you doing here?' I said. 'A bit of leave before I go back to Rangoon. Yes, I walk. You see I am working for Intelligence and every few weeks I have to walk across Burma to report and I take a spot of leave in a comfortable hotel.' And we left him out for reason of age!

Two incidents stand out in my mind during jungle training. First, an early monsoon was drumming on my office tent and the flies were sagging. Approaching through the mud came a pair of bare feet; as they came nearer a pair of naked knees appeared, and then some more naked body and finally Wingate crouched under the tent flies — wearing his Wolseley helmet and nothing else!

Second, the river where the Gurkha unit was camped started to rise and we were out of touch. Nothing for it, I had to swim through the flooded water to make contact. It was a nightmare. Every animal which could swim was in the water with me. I could rest by holding the branches of trees which was what the snakes were doing. An alligator gave me a dirty look. But it ended happily. The Gurkhas had taken to the trees and were safe if not happy, and the water went down quite quickly.

Wingate had a convenient theory about official correspondence: if left in the pending tray, most of it answered itself. If really important a reminder would follow and that was the time to reply. Sponsored by Wavell, he had of course the ear of all the heads of department in Delhi. However, he didn't understand the Indian bureaucracy and didn't want to, so every time he visited Delhi I had to nip up next day to get the results in black and white and signed. I didn't mind, I knew the system and had a girlfriend there.

George Bromhead took up his position as Brigade-Major at the Chindit training camp in Saugor, where he assisted Wingate with his operational planning for the first expedition into Burma. After Operation Longcloth, Bromhead sat down and wrote out his debrief notes and thoughts on the operation. These notes included his views on the experimental use of air supply in 1943, which in his opinion was perhaps the greatest success of the whole affair.

He remarked upon the haphazard nature of the training regime for Longcloth and the unsuitable nature of the 13th King's as infantry troops. However, he qualified this position by stating that the men who eventually entered Burma in February 1943 performed admirably and gave a good account of themselves. Equipment and supplies were another area of concern in his debrief paper, with items such as the wireless and radio sets coming under severe criticism for both their size and indeed performance in jungle conditions.

He comments on the positive effect of Operation Longcloth on the morale of the Allied troops back in the CBI theatre and for the British public back home. He states that: "the achievements of this small force were far out of proportion to its size. Its presence halting the Japanese offensive against Fort Hertz in the north of Burma when the railway was cut and the push against the Chinese across the Salween being severely hindered and enemy troops withdrawn from this front to deal with our incursion."

Bromhead congratulates his Brigadier on the use of the Burma Rifles in the campaign. He realises the critical importance of their local knowledge, field-craft and the essential advantage of winning the hearts and minds of the people, through whose country you are travelling. He applauds the use of the seven Chindit columns, spreading them over a wide enough area so as to ensure their individual security, but not so far apart that they became adrift and could if necessary come to each others aid.

Other groups to be praised in the report were the Commandos and the RAF liaison officers, who in Bromhead's opinion were the "most enthusiastic and toughest section of men that any commander in the field could have wanted." The quality and nutritional value of the rations for Operation Longcloth came under scrutiny in the report. The conclusion was that the calorific value of the rations, set at around 3000 calories per man per day and supplemented by another 1000 calories a day from local villages, was not nearly enough for a prolonged campaign over several months. In Bromhead's view, this undoubtedly caused fatigue and starvation amongst the troops, especially the British contingent and this in the end added significantly to the final casualty figures.

On the subject of casualties, the report touches on the negative effect on morale of having to leave wounded or sick men behind in the jungle. Also mentioned, was the lack of medicines available to the medical officers serving in each column, although the performance of these men is praised by Bromhead, stating that: "the medical officers on Longcloth, although not overladen with medicines found ways around certain difficulties and abundantly repaid the faith the men placed upon them."

The importance of morale is emphasised in the report time and again, but in the end according to Major Bromhead comes down to one single factor, that of confidence. He states in his paper: "confidence is vital, confidence of each soldier in his own abilities to fight and exist in the jungle, confidence in his leaders, confidence in those who are planning for him and feeding him, confidence in his weapons, but above all confidence in himself."

George Bromhead concluded in his report that: "The operations in 1943 were essentially experimental, but proved far more successful than the average soldier had expected. On these efforts were laid the basis of larger scale operations the following year, when more of the right equipment was available and when the forces for the most part entered Burma in gliders and thus overcame the problem of fatigue in reaching their initial objectives."

As mentioned, Major Bromhead began the first Wingate expedition as part of Brigade Head Quarters. He recalled:

The move to the starting point on the Chindwin River was uneventful, but the crossing was more of a problem. Men and stores were ferried over by the local villagers in wooden boats. But what of the mules? Well, I had been told that they would follow a grey mare, so I got myself one. I was pretty sceptical, but I had the mules gathered where a long sand spit pointed out into a bend in the river, with only shallow water in front and so the first part of the crossing was achieved by wading. When we reached the deep part of the bend the other bank didn’t look that far away. I dismounted to swim alongside the grey and yes, the mules all followed.

Not long into the expedition, Major Bromhead was ordered by Wingate to take command of 4 Column, a Gurkha unit that formed part of Northern Group in 1943, and which was commanded in the first instance by Major Philip Conron. The column, whose main role on the expedition was to protect the British column's northern flank, was the first unit from Northern Group to be attacked by the Japanese and generally had a difficult time inside Burma.

NB. Major Conron had taken over command of No. 4 Column in late 1942 from the original D Company Commander (3/2 Gurkha Rifles), Captain David Kenneth Oldrini, later to be awarded the Military Cross for his efforts with the battalion in the Myebon area of the Arakan in January 1945.

There is very little written about the exploits of Column 4 in 1943. To help describe their time in Burma, here is an extract from the book, 'Wingate's Lost Brigade', by author Phil Chinnery:

4 Column was the first of the seven to break up and return to India. It had been led from the start by Major Conron of 3/2nd Gurkhas and had reached the Brigade rendezvous at Tonmakeng on 24 February. Thereafter it was tasked to protect a Brigade supply dropping and then to reconnoitre and improve Castens Trail, the secret track of the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment.

It was hard work clearing the route, but necessary to avoid the Japanese. As the columns descended they saw a deep valley, in reality the head-waters of two: the Chaunggyi or Great Stream, which went northward for a few miles before turning abruptly to the west to break through the Zibyu Taungdan in a deep gorge; and the Mu Valley proper.

Across the valley rose the hills of the Mangin range, running up to 3,700 feet of the Kalat Taung opposite. Beyond the hills was the Meza Valley and beyond that, the railway and the important communications centre of Indaw. As the columns reached the valley floor, Major Fergusson noted that 'Wingate was not in the best of tempers. He was annoyed with 4 Column for some sin of omission.'

That day, 1st March, Wingate relieved Major Conron of his command and replaced him with Major Bromhead, his Brigade Major. The official reason for such a drastic step is hard to fathom. The change of command was not mentioned in Wingate's after-action report. Bromhead himself told the author: 'We were halfway across Burma when 4 Column Commander lost his nerve. He could not stand the sound of a battery charging engine and so his radios failed. Wingate withdrew him to Brigade HQ and I took his place. We managed after a day or two to get the main radio working and set off to follow Brigade HQ, who by now were way ahead.'

Conron was never able to tell his side of the story. After Wingate later ordered the dispersal of the columns he was last seen near the Shweli River in command of a group from Brigade Headquarters. According to an eyewitness account he was drowned through the treachery of Burmese boatmen while attempting to cross that river.

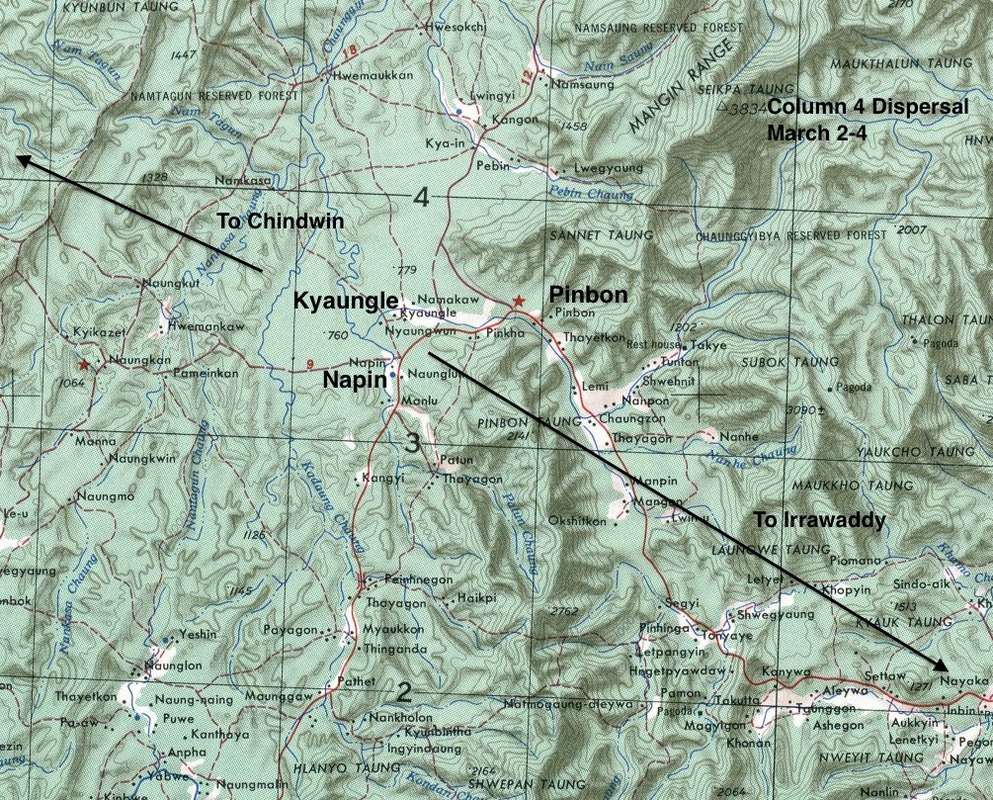

On 2nd March, the day after Bromhead took over command, the Burma Rifles reconnaissance detachment bumped a group of Japanese soldiers near Pinbon and one man was lost. A fighting patrol out searching for the missing man encountered another Japanese patrol and shot dead an NCO. In the meantime Wingate had decided to shift his attack on the railway from the Indaw area to the Wuntho-Bonchaung area, thirty-five miles further south.

He instructed 4 Column to rejoin the main group without delay. During the morning of 4th March, while the column was marching south-east along the base of the mountains, all hell broke loose. The column was in the usual single-file 'snake' formation and strung out over 1,000 yards when the undergrowth came alive with enemy small arms fire. Half of the formation had already crossed a small stream, when a shower of enemy mortar bombs began to fall on the ford, preventing the rest from crossing. The column had walked into a trap.

While a rearguard platoon held the enemy at the stream, Lieutenants Stuart-Jones and Green and Subedar Tikajit Pun led 135 men and thirty mules away to the north. The remainder of the column that had already crossed the stream dispersed in small groups and headed for the pre-arranged rendezvous twenty miles to the south.

Bromhead's group comprised about fifteen souls, including Captain Ray Scott of the Burma Rifles, whose knowledge of the countryside would help to get them home. However, their radios were finished. Bromhead recalled:

'We met a Jap patrol and although we beat them off our only radio got a bullet. Since the Japs used soft-nosed bullets it was the end of that radio. The column was split by the encounter, but all reached the rendezvous that evening and we sat down to consider our situation. No communications, little food and no way of getting more except courtesy of the locals, and the British Officers of the Gurkha column reported very poor morale. What to do?

'We could not influence the war, so I decided to turn back. At this point our luck changed a bit. A villager told me that at the top of a steep hill behind the village there started a forest boundary trail, going, roughly, the right way. The hill was certainly steep, but the Gurkhas with their kukris cut steps for the mules and we all reached the top. And there was a well marked trail and I could recognise the forest blazes. We managed to buy enough rice and had an uneventful march back to the Chindwin.

I mapped the route and by coincidence a battalion of my regiment (Royal Berkshires) used most of it later when Burma was invaded. On the way back my main worry was that we might be mistaken for the enemy by our own forces. Fortunately we spotted a British patrol east of the Chindwin before they saw us and made contact.

We crossed the river where a battalion of a State Force held the front. Jaipuris I think. Memorable because the Commanding Officer said, "I expect you could do with a bath", and his men dug a hole, lined it with ground sheets and filled it with hot water. The best bath I can remember.

I had written a series of non-committal "air grams" before we went into Burma and left them back at air base to be posted weekly. Thus it was that my mother got a brief letter saying that all was quite routine, at the same time as she opened her morning paper to see my ugly mug spread across the front page. 'I went back to Imphal and set up shop at the Army HQ. My tummy rebelled in a big way at the rich food and I realised that when the Brigade got back some hospital checks would be necessary.

Eventually Wingate and the columns returned but, alas, with many a gap. The Gurkhas to their own centres and the British to Bombay. Wingate and I visited Simla, the summer capital, to report. Finally he started raising the next year's force. At that moment the Army sent me to Staff College at Quetta, presumably to learn how it should be done. Next year I was in New Guinea with the Aussies.'

As for Lieutenant Stuart-Jones, his troubles were only just beginning. On the evening of the ambush he led his men north in an effort to contact the other columns. After two days he handed over command to Captain Finlay of the commando detachment and went ahead with eight others. Six days later, out of food and near collapse, they made contact with 8 Column. In the meantime Captain Finlay and his party had turned back for India, menaced by starvation. Weeks later, Stuart-Jones and his four faithful Gurkha Riflemen reached safety in Fort Hertz, a British outpost on the border with China.

The move to the starting point on the Chindwin River was uneventful, but the crossing was more of a problem. Men and stores were ferried over by the local villagers in wooden boats. But what of the mules? Well, I had been told that they would follow a grey mare, so I got myself one. I was pretty sceptical, but I had the mules gathered where a long sand spit pointed out into a bend in the river, with only shallow water in front and so the first part of the crossing was achieved by wading. When we reached the deep part of the bend the other bank didn’t look that far away. I dismounted to swim alongside the grey and yes, the mules all followed.

Not long into the expedition, Major Bromhead was ordered by Wingate to take command of 4 Column, a Gurkha unit that formed part of Northern Group in 1943, and which was commanded in the first instance by Major Philip Conron. The column, whose main role on the expedition was to protect the British column's northern flank, was the first unit from Northern Group to be attacked by the Japanese and generally had a difficult time inside Burma.

NB. Major Conron had taken over command of No. 4 Column in late 1942 from the original D Company Commander (3/2 Gurkha Rifles), Captain David Kenneth Oldrini, later to be awarded the Military Cross for his efforts with the battalion in the Myebon area of the Arakan in January 1945.

There is very little written about the exploits of Column 4 in 1943. To help describe their time in Burma, here is an extract from the book, 'Wingate's Lost Brigade', by author Phil Chinnery:

4 Column was the first of the seven to break up and return to India. It had been led from the start by Major Conron of 3/2nd Gurkhas and had reached the Brigade rendezvous at Tonmakeng on 24 February. Thereafter it was tasked to protect a Brigade supply dropping and then to reconnoitre and improve Castens Trail, the secret track of the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment.

It was hard work clearing the route, but necessary to avoid the Japanese. As the columns descended they saw a deep valley, in reality the head-waters of two: the Chaunggyi or Great Stream, which went northward for a few miles before turning abruptly to the west to break through the Zibyu Taungdan in a deep gorge; and the Mu Valley proper.

Across the valley rose the hills of the Mangin range, running up to 3,700 feet of the Kalat Taung opposite. Beyond the hills was the Meza Valley and beyond that, the railway and the important communications centre of Indaw. As the columns reached the valley floor, Major Fergusson noted that 'Wingate was not in the best of tempers. He was annoyed with 4 Column for some sin of omission.'

That day, 1st March, Wingate relieved Major Conron of his command and replaced him with Major Bromhead, his Brigade Major. The official reason for such a drastic step is hard to fathom. The change of command was not mentioned in Wingate's after-action report. Bromhead himself told the author: 'We were halfway across Burma when 4 Column Commander lost his nerve. He could not stand the sound of a battery charging engine and so his radios failed. Wingate withdrew him to Brigade HQ and I took his place. We managed after a day or two to get the main radio working and set off to follow Brigade HQ, who by now were way ahead.'

Conron was never able to tell his side of the story. After Wingate later ordered the dispersal of the columns he was last seen near the Shweli River in command of a group from Brigade Headquarters. According to an eyewitness account he was drowned through the treachery of Burmese boatmen while attempting to cross that river.

On 2nd March, the day after Bromhead took over command, the Burma Rifles reconnaissance detachment bumped a group of Japanese soldiers near Pinbon and one man was lost. A fighting patrol out searching for the missing man encountered another Japanese patrol and shot dead an NCO. In the meantime Wingate had decided to shift his attack on the railway from the Indaw area to the Wuntho-Bonchaung area, thirty-five miles further south.

He instructed 4 Column to rejoin the main group without delay. During the morning of 4th March, while the column was marching south-east along the base of the mountains, all hell broke loose. The column was in the usual single-file 'snake' formation and strung out over 1,000 yards when the undergrowth came alive with enemy small arms fire. Half of the formation had already crossed a small stream, when a shower of enemy mortar bombs began to fall on the ford, preventing the rest from crossing. The column had walked into a trap.

While a rearguard platoon held the enemy at the stream, Lieutenants Stuart-Jones and Green and Subedar Tikajit Pun led 135 men and thirty mules away to the north. The remainder of the column that had already crossed the stream dispersed in small groups and headed for the pre-arranged rendezvous twenty miles to the south.

Bromhead's group comprised about fifteen souls, including Captain Ray Scott of the Burma Rifles, whose knowledge of the countryside would help to get them home. However, their radios were finished. Bromhead recalled:

'We met a Jap patrol and although we beat them off our only radio got a bullet. Since the Japs used soft-nosed bullets it was the end of that radio. The column was split by the encounter, but all reached the rendezvous that evening and we sat down to consider our situation. No communications, little food and no way of getting more except courtesy of the locals, and the British Officers of the Gurkha column reported very poor morale. What to do?

'We could not influence the war, so I decided to turn back. At this point our luck changed a bit. A villager told me that at the top of a steep hill behind the village there started a forest boundary trail, going, roughly, the right way. The hill was certainly steep, but the Gurkhas with their kukris cut steps for the mules and we all reached the top. And there was a well marked trail and I could recognise the forest blazes. We managed to buy enough rice and had an uneventful march back to the Chindwin.

I mapped the route and by coincidence a battalion of my regiment (Royal Berkshires) used most of it later when Burma was invaded. On the way back my main worry was that we might be mistaken for the enemy by our own forces. Fortunately we spotted a British patrol east of the Chindwin before they saw us and made contact.

We crossed the river where a battalion of a State Force held the front. Jaipuris I think. Memorable because the Commanding Officer said, "I expect you could do with a bath", and his men dug a hole, lined it with ground sheets and filled it with hot water. The best bath I can remember.

I had written a series of non-committal "air grams" before we went into Burma and left them back at air base to be posted weekly. Thus it was that my mother got a brief letter saying that all was quite routine, at the same time as she opened her morning paper to see my ugly mug spread across the front page. 'I went back to Imphal and set up shop at the Army HQ. My tummy rebelled in a big way at the rich food and I realised that when the Brigade got back some hospital checks would be necessary.

Eventually Wingate and the columns returned but, alas, with many a gap. The Gurkhas to their own centres and the British to Bombay. Wingate and I visited Simla, the summer capital, to report. Finally he started raising the next year's force. At that moment the Army sent me to Staff College at Quetta, presumably to learn how it should be done. Next year I was in New Guinea with the Aussies.'

As for Lieutenant Stuart-Jones, his troubles were only just beginning. On the evening of the ambush he led his men north in an effort to contact the other columns. After two days he handed over command to Captain Finlay of the commando detachment and went ahead with eight others. Six days later, out of food and near collapse, they made contact with 8 Column. In the meantime Captain Finlay and his party had turned back for India, menaced by starvation. Weeks later, Stuart-Jones and his four faithful Gurkha Riflemen reached safety in Fort Hertz, a British outpost on the border with China.

Another Gurkha Officer with 4 Column in 1943 was Captain David Oldrini. As Adjutant, he was given the task of keeping the column War diary during Operation Longcloth and here is how he recalled the events leading up to the unit's demise:

On March 1st the Brigade group split up into its individual Columns, each having been allotted a separate task. Column 4's task was to watch a section of the motor road which ran north to south through Pinbon, Banmauk and down to the Aerodrome at Indaw just west of the Irrawaddy. We were then meant to join up with Brigade at a rendezvous south of Banmauk.

On March 2nd, the Guerrilla Platoon was ordered to go out and recce tracks leading west from the motor road, and also to find out any information regarding the enemy in the neighbouring villages. The second line stayed in bivouac some three miles east of the road, while two fighting platoons went to see what they could ambush on the road. Having watched the road for eighteen hours with no luck these platoons decided to return to bivouac.

Meanwhile, our Guerrilla Platoon had had a scrap with some Japs near the village of Napin. Some of the Guerrillas had returned with a wounded man and also reported that Lt. Burn and a Naik had also been wounded. A patrol under the command of Lt. Stuart-Jones set out to try and find Lt. Burn and the Naik. He was unsuccessful, however, shortly afterwards Lt. Burn turned up alone having been shot through the shoulder. The Naik was never found. It is believed that two Japanese were killed.

Stuart-Jones, during the course of his search managed to kill a Jap soldier, from whom he obtained a rifle, bayonet, three grenades, 200 rounds of ammunition, some money and a few other odds and ends. He also found a slip of paper with some writing on it. When he returned our Japanese interpreter tried to decipher the slip. We later discovered that it was part of a standing order for the Brothel at Pinlebu. The men became more than a little anxious to attack that village!

We left our little area just west of the motor road at dawn on the 4th March. We set off in the usual Column 'snake' and after about three hours marching we came to the village of Kyaungle. The only way we could get passed this village with the mules was along a small track through the forest just a few yards to the east.

When the column was nicely placed along this track, without warning, every possible type of weapon seemed to open up on us. Animals immediately started to panic and there was no holding them. Loads had been thrown right and left and caught up in branches, leaving nothing but a stampeding mass of mules.

This was at about 10:00 hours. Men dispersed and took up positions as best they could and the battle continued for about two and a half hours. We were unable to get our mortars into action, but we fired our Vickers guns until they were out of ammunition and the men used their grenades to good effect.

While the battle was going on the second line troops had collected together remarkably well, getting around 70% of the mules out complete with their loads. They then set off for the agreed rendezvous about twenty miles south of Kyaungle. When peace and quiet resumed, dispersal groups set off for the rendezvous as and when they could collect together.

Casualties on our side were three missing and two wounded, which is quite remarkable as everyone thought there must have been at least 100 killed. Our animals suffered much worse and we lost over thirty that day. No less than forty Japanese had been killed, possibly a lot more. However, as we had not turned up on time, Brigade had set off without us. Our wireless was out of order, so we could not call up for air supply droppings of food and ammunition. We were by then all out of food as it was March 7th and our last supply drop had been on the 26th February.

As we did not know where Brigade had gone and could no longer get in touch with them, there was nothing for it but to turn back to India. The villages in that area were full of Japs so we could not get food supplies in that way. We had a small amount of mule grain left, so we shared this out and set off on the homeward journey. After we had re-crossed the escarpment we were able to get rice in local villages and each man had half a cupful of rice each day, together with mule flesh for those who could eat it. Eventually we re-crossed the Chindwin River and on into Assam once more.

Wingate did write down his own views on the performance of Major Bromhead and 4 Column in 1943. As part of his full debrief for the operation he had this to say about the Gurkha unit:

On the 2nd and 3rd March, No.4 Column carried out various reconnaissances in the Pinbon area occasionally colliding with the enemy and collecting one Japanese body. I had ordered the Column Commander (Bromhead) to pass Pinbon eastwards not later than the 4th if he could, as I still intended to move on to Indaw.

Hearing nothing from No.5 Column about the "Happy Valley" route and learning from No.3 that the Kaignmakan route was clear, I decided to use the latter. This directed my main force on Wuntho and not Indaw. I therefore informed No.4 Column that the plan was changed, and since his wireless set was working badly, ordered him to join me before I proceeded.

He started out to do this on the 4th, and early in the morning encountered an enemy force of unknown strength, in the neighbourhood of Nyaungwuw. There followed what can only be described as a disgraceful exhibition of panic by the Gurkha Rifles; both the Burma Rifles and the British troops remaining firm and endeavouring to obey their Commander and restore order.

The brilliant history of the Gurkha Rifles in war, and indeed the splendid performances of No.3 Column in those Operations, makes it all the more necessary to tell the truth about what occurred on 4th March, but this is not the place for a post mortem.

It is sufficient to say that after repeated attempts to rally the Column and counter attack, the Column Commander did ultimately collect the greater part of his force at his Operational Rendezvous. Here I must point out that without the use of a Rendezvous to be used on Dispersal, this Column would have broken up and few indeed would have returned.

In the panic, the cipher had been lost, and it was quite impossible for me to send a R.V. in the clear although a cryptic message was sent from which it was hoped the general line of my advance could be deduced. This message did not reach the Column Commander.

The latter, who was now without supplies or means of obtaining them, had lost much indispensable equipment, and was separated from the Brigade Group by strong enemy forces, rightly decided to march back to the Chindwin. I have no adverse comment to pass on his conduct which showed judgment and courage throughout. The faults of No.4 Column were those of others.

After returning to India in April 1943, Brigadier Wingate recommended Major Bromhead for the award of a MBE for his efforts on Operation Longcloth and for his part in the overall planning of the expedition. His citation reads:

Operations in Burma, March - April 1943

Major Bromhead was Brigade Major of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade from the time of its formation until during the course of operations he took over command of No. 4 Column in the field. He showed himself to be an exceptionally conscientious and thorough staff officer with a real insight into the art of Long Range Penetration. Throughout the period of training, his services were of great value and to him is due much of the credit for the successful launching of the Brigade in operations. From the time of mobilization at the end of December 1942 until the Brigade was fully concentrated at Manipur Road on 19th January 1943, Major Bromhead was virtually in command and carried out the move to my complete satisfaction. Later, his organisation of all arrangements in connection with the march of the Brigade from Manipur Road to the Chindwin showed an excellent grasp of essentials and an eye for detail. In operations against the enemy Major Bromhead showed himself calm, cool and courageous and possessed of excellent judgement.

Recommended By- Brigadier O.C.Wingate, D.S.O.

Commander, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade Group.

Honour or Reward- M.B.E (Military Division).

(London Gazette 16.12.1943).

Seen below are two of the medallic awards received by George Bromhead during his long and illustrious Army career. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

On March 1st the Brigade group split up into its individual Columns, each having been allotted a separate task. Column 4's task was to watch a section of the motor road which ran north to south through Pinbon, Banmauk and down to the Aerodrome at Indaw just west of the Irrawaddy. We were then meant to join up with Brigade at a rendezvous south of Banmauk.

On March 2nd, the Guerrilla Platoon was ordered to go out and recce tracks leading west from the motor road, and also to find out any information regarding the enemy in the neighbouring villages. The second line stayed in bivouac some three miles east of the road, while two fighting platoons went to see what they could ambush on the road. Having watched the road for eighteen hours with no luck these platoons decided to return to bivouac.

Meanwhile, our Guerrilla Platoon had had a scrap with some Japs near the village of Napin. Some of the Guerrillas had returned with a wounded man and also reported that Lt. Burn and a Naik had also been wounded. A patrol under the command of Lt. Stuart-Jones set out to try and find Lt. Burn and the Naik. He was unsuccessful, however, shortly afterwards Lt. Burn turned up alone having been shot through the shoulder. The Naik was never found. It is believed that two Japanese were killed.

Stuart-Jones, during the course of his search managed to kill a Jap soldier, from whom he obtained a rifle, bayonet, three grenades, 200 rounds of ammunition, some money and a few other odds and ends. He also found a slip of paper with some writing on it. When he returned our Japanese interpreter tried to decipher the slip. We later discovered that it was part of a standing order for the Brothel at Pinlebu. The men became more than a little anxious to attack that village!

We left our little area just west of the motor road at dawn on the 4th March. We set off in the usual Column 'snake' and after about three hours marching we came to the village of Kyaungle. The only way we could get passed this village with the mules was along a small track through the forest just a few yards to the east.

When the column was nicely placed along this track, without warning, every possible type of weapon seemed to open up on us. Animals immediately started to panic and there was no holding them. Loads had been thrown right and left and caught up in branches, leaving nothing but a stampeding mass of mules.

This was at about 10:00 hours. Men dispersed and took up positions as best they could and the battle continued for about two and a half hours. We were unable to get our mortars into action, but we fired our Vickers guns until they were out of ammunition and the men used their grenades to good effect.

While the battle was going on the second line troops had collected together remarkably well, getting around 70% of the mules out complete with their loads. They then set off for the agreed rendezvous about twenty miles south of Kyaungle. When peace and quiet resumed, dispersal groups set off for the rendezvous as and when they could collect together.

Casualties on our side were three missing and two wounded, which is quite remarkable as everyone thought there must have been at least 100 killed. Our animals suffered much worse and we lost over thirty that day. No less than forty Japanese had been killed, possibly a lot more. However, as we had not turned up on time, Brigade had set off without us. Our wireless was out of order, so we could not call up for air supply droppings of food and ammunition. We were by then all out of food as it was March 7th and our last supply drop had been on the 26th February.

As we did not know where Brigade had gone and could no longer get in touch with them, there was nothing for it but to turn back to India. The villages in that area were full of Japs so we could not get food supplies in that way. We had a small amount of mule grain left, so we shared this out and set off on the homeward journey. After we had re-crossed the escarpment we were able to get rice in local villages and each man had half a cupful of rice each day, together with mule flesh for those who could eat it. Eventually we re-crossed the Chindwin River and on into Assam once more.

Wingate did write down his own views on the performance of Major Bromhead and 4 Column in 1943. As part of his full debrief for the operation he had this to say about the Gurkha unit:

On the 2nd and 3rd March, No.4 Column carried out various reconnaissances in the Pinbon area occasionally colliding with the enemy and collecting one Japanese body. I had ordered the Column Commander (Bromhead) to pass Pinbon eastwards not later than the 4th if he could, as I still intended to move on to Indaw.

Hearing nothing from No.5 Column about the "Happy Valley" route and learning from No.3 that the Kaignmakan route was clear, I decided to use the latter. This directed my main force on Wuntho and not Indaw. I therefore informed No.4 Column that the plan was changed, and since his wireless set was working badly, ordered him to join me before I proceeded.

He started out to do this on the 4th, and early in the morning encountered an enemy force of unknown strength, in the neighbourhood of Nyaungwuw. There followed what can only be described as a disgraceful exhibition of panic by the Gurkha Rifles; both the Burma Rifles and the British troops remaining firm and endeavouring to obey their Commander and restore order.

The brilliant history of the Gurkha Rifles in war, and indeed the splendid performances of No.3 Column in those Operations, makes it all the more necessary to tell the truth about what occurred on 4th March, but this is not the place for a post mortem.

It is sufficient to say that after repeated attempts to rally the Column and counter attack, the Column Commander did ultimately collect the greater part of his force at his Operational Rendezvous. Here I must point out that without the use of a Rendezvous to be used on Dispersal, this Column would have broken up and few indeed would have returned.

In the panic, the cipher had been lost, and it was quite impossible for me to send a R.V. in the clear although a cryptic message was sent from which it was hoped the general line of my advance could be deduced. This message did not reach the Column Commander.

The latter, who was now without supplies or means of obtaining them, had lost much indispensable equipment, and was separated from the Brigade Group by strong enemy forces, rightly decided to march back to the Chindwin. I have no adverse comment to pass on his conduct which showed judgment and courage throughout. The faults of No.4 Column were those of others.

After returning to India in April 1943, Brigadier Wingate recommended Major Bromhead for the award of a MBE for his efforts on Operation Longcloth and for his part in the overall planning of the expedition. His citation reads:

Operations in Burma, March - April 1943

Major Bromhead was Brigade Major of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade from the time of its formation until during the course of operations he took over command of No. 4 Column in the field. He showed himself to be an exceptionally conscientious and thorough staff officer with a real insight into the art of Long Range Penetration. Throughout the period of training, his services were of great value and to him is due much of the credit for the successful launching of the Brigade in operations. From the time of mobilization at the end of December 1942 until the Brigade was fully concentrated at Manipur Road on 19th January 1943, Major Bromhead was virtually in command and carried out the move to my complete satisfaction. Later, his organisation of all arrangements in connection with the march of the Brigade from Manipur Road to the Chindwin showed an excellent grasp of essentials and an eye for detail. In operations against the enemy Major Bromhead showed himself calm, cool and courageous and possessed of excellent judgement.

Recommended By- Brigadier O.C.Wingate, D.S.O.

Commander, 77th Indian Infantry Brigade Group.

Honour or Reward- M.B.E (Military Division).

(London Gazette 16.12.1943).

Seen below are two of the medallic awards received by George Bromhead during his long and illustrious Army career. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

After Operation Longcloth was over, Bromhead recalled:

When we were all back in India, the baboos (top brass Army clerks) got busy and demanded from me as Brigade Major, an account of all the cash spent by us in Burma. I replied that it was far too secret to divulge, as it could endanger the lives of the villagers that had helped us. After Burma fell they were back with the same question, but by that time I was under orders for home and dodged them again. Bernard Fergusson on Wingate’s orders, wrote a detailed report on the first operation. It was duly printed by GHQ at Delhi and delivered out to the necessary. However, no one in authority had read it before printing and when they finally did so it was immediately withdrawn. I have never seen it since.

George Bromhead continued to serve in the British Army long after WW2 was over. With the new rank of Lieutenant-Colonel he returned to his original regiment, the Royal Berkshire's, where he was again recognised for his efforts during the Cyprus campaign against the EOKA terrorists, receiving a Mention in Despatches, Gazetted on the 1st February 1958 and then the award of an OBE later that same year.

In March 1966 he finally took his retirement after nearly 33 years service. His remarkable Army career was acknowledged in the New Years Honours list for that same year, when he was awarded the CBE (Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire). To conclude this story, seen below is Colonel Bromhead's citation for the award of his CBE, which outlines the high points of his long and distinguished service in the British Army.

Colonel Bromhead retires in March 1966 after 32 years and 7 months service.

He was commissioned from the Royal Military College, Sandhurst in 1933 into the Royal Berkshire Regiment and saw service in Palestine pre-war. Since then he has held, with distinction, a number of important appointments including the command of the 1st Battalion of his Regiment during the EOKA emergency in Cyprus. He was appointed Colonel, The Duke of Edinburgh's Royal Regiment in November 1964.

Currently Colonel Bromhead is AAG, AG 2 (Assistant Adjutant General) at the Ministry of Defence. This Personnel Branch deals with the Infantry, and is not only responsible for the routine administration of infantry officers, the largest Corps in the Army, but also for the manning of infantry units and establishments world-wide, and the provision of individuals as emergency reinforcements and for secondment to the Commonwealth and Colonial Forces.

Since Colonel Bromhead has been AAG AG 2 these responsibilities have greatly increased due to rising commitments, demands for individual emergency reinforcements and the increasing number of infantry battalions on emergency tours. All this against a background of shortage of officers, particularly in those age groups where the demand is most severe. Great credit must be given to Colonel Bromhead that the infantry has been manned in the best possible way during this difficult period. He has never spared himself in his efforts to ensure this. It has involved him in long hours of hard and devoted work, careful planning and foresight and wise and firm direction of his staff.

In all Colonel Bromhead has given devoted, valuable and distinguished service to the Army over a period of nearly 33 years.

Date of recommendation 25/08/1965, announced New Year's Honours List 1966.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, October 2015.

When we were all back in India, the baboos (top brass Army clerks) got busy and demanded from me as Brigade Major, an account of all the cash spent by us in Burma. I replied that it was far too secret to divulge, as it could endanger the lives of the villagers that had helped us. After Burma fell they were back with the same question, but by that time I was under orders for home and dodged them again. Bernard Fergusson on Wingate’s orders, wrote a detailed report on the first operation. It was duly printed by GHQ at Delhi and delivered out to the necessary. However, no one in authority had read it before printing and when they finally did so it was immediately withdrawn. I have never seen it since.

George Bromhead continued to serve in the British Army long after WW2 was over. With the new rank of Lieutenant-Colonel he returned to his original regiment, the Royal Berkshire's, where he was again recognised for his efforts during the Cyprus campaign against the EOKA terrorists, receiving a Mention in Despatches, Gazetted on the 1st February 1958 and then the award of an OBE later that same year.

In March 1966 he finally took his retirement after nearly 33 years service. His remarkable Army career was acknowledged in the New Years Honours list for that same year, when he was awarded the CBE (Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire). To conclude this story, seen below is Colonel Bromhead's citation for the award of his CBE, which outlines the high points of his long and distinguished service in the British Army.

Colonel Bromhead retires in March 1966 after 32 years and 7 months service.

He was commissioned from the Royal Military College, Sandhurst in 1933 into the Royal Berkshire Regiment and saw service in Palestine pre-war. Since then he has held, with distinction, a number of important appointments including the command of the 1st Battalion of his Regiment during the EOKA emergency in Cyprus. He was appointed Colonel, The Duke of Edinburgh's Royal Regiment in November 1964.

Currently Colonel Bromhead is AAG, AG 2 (Assistant Adjutant General) at the Ministry of Defence. This Personnel Branch deals with the Infantry, and is not only responsible for the routine administration of infantry officers, the largest Corps in the Army, but also for the manning of infantry units and establishments world-wide, and the provision of individuals as emergency reinforcements and for secondment to the Commonwealth and Colonial Forces.

Since Colonel Bromhead has been AAG AG 2 these responsibilities have greatly increased due to rising commitments, demands for individual emergency reinforcements and the increasing number of infantry battalions on emergency tours. All this against a background of shortage of officers, particularly in those age groups where the demand is most severe. Great credit must be given to Colonel Bromhead that the infantry has been manned in the best possible way during this difficult period. He has never spared himself in his efforts to ensure this. It has involved him in long hours of hard and devoted work, careful planning and foresight and wise and firm direction of his staff.

In all Colonel Bromhead has given devoted, valuable and distinguished service to the Army over a period of nearly 33 years.

Date of recommendation 25/08/1965, announced New Year's Honours List 1966.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, October 2015.