Major Gilmour Menzies Anderson

Major G.M. Anderson, Colchester 1941.

Major G.M. Anderson, Colchester 1941.

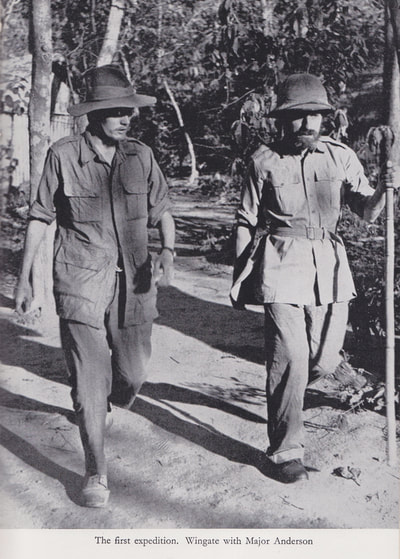

The commander of No. 6 Column was Gim Anderson of the Highland Light Infantry and the original Adjutant of the 13th King's. He was a sandy-haired solicitor from Glasgow, of which city he was already a councillor at the age of just twenty-seven and was one of the best officers we had in the Brigade.

Bernard Fergusson, from his book Beyond the Chindwin.

Gilmour Menzies Anderson was born on the 29th April 1914 in the Hillhead district of Glasgow. He was the son of William Menzies Anderson DSO, MC and Jessie Jack Gilmour. He was educated at Glasgow High School and Glasgow University, where presumably he studied Law as he became a qualified Solicitor in 1939. He was a Cadet at the Kelvinside Academy and undertook his officer training here before being commissioned into the Highland Light Infantry (6th Battalion) on the 24th May 1939, whilst serving with the Territorial Army. He also served as a Glasgow City councillor before the war, where he represented the Ruchill Ward.

2nd Lieutenant Anderson was mobilised on the 24th August 1939 with the Highland Light Infantry, before moving across to the 13th Battalion of the King's Regiment on the 6th July 1940 and taking on the roll of battalion Adjutant with immediate effect. After receiving two successive promotions in October 1940, Menzies Anderson was elevated once more, this time to the rank of Temporary Major in August 1941 and just prior to the 13th King's movement overseas to India.

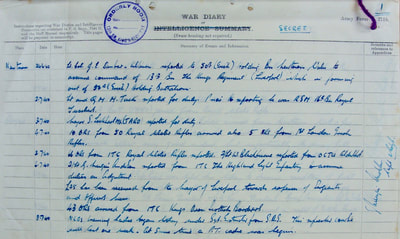

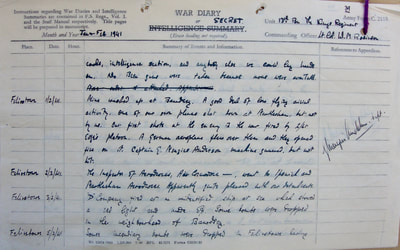

For the majority of his time as Adjutant, the 13th King's were based in the south east of England performing coastal defence duties. Included within his duties as Adjutant, was the keeping of the battalion War diary. On the 1st February 1941 whilst the King's were stationed at Felixstowe on the Suffolk coastline, Menzies Anderson recorded the following rather candid entry into the battalion diary:

A mine was washed up at Bawdsey today, also we had a lot of air activity and one of our planes was shot down at Martlesham, but not by us! Our first shots at the enemy in the war were fired by 2nd Lieutenant Edge's platoon. A German aeroplane (Messerschmidt) flew over them and they opened fire on it. Captain G. Menzies Anderson was then machine gunned (by the German plane), but was not hit.

After further postings to Ipswich, Colchester and Burford in Oxfordshire, in late October 1941 the 13th King's finally received orders to prepare for a move overseas. Six weeks later on the 8th December, the battalion left Liverpool Docks and voyaged to India aboard the troopship Oronsay, which formed part of Convoy WS 14. The convoy moved out into the Irish Sea and then headed north towards Greenock on the Scottish coastline, eventually pushing deeper into the Atlantic, initially in a north-westerly direction to avoid any unwanted attention from enemy U-Boats.

The first port of call on the voyage was Freetown, Sierra Leone, where the convoy was restocked with supplies, but no shore leave was granted. Later, as the convoy approached the South African seaboard, the ships were split into two groups, one docking at Cape Town and the other at Durban. The 13th King's enjoyed a five night shore-leave at Durban commencing on the 8th January 1942.

After changing ships on two further occasions, the 13th King's finally docked at Bombay on the 30th January 1942 and were met by a section from their sister battalion, the 1st King's Liverpool, who escorted them to their new home at Secunderabad in Telangana State. For the next five months the 13th King's performed internal security and garrison duties at Secunderabad and settled down to life on the sub-continent.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In late June 1942, the battalion were handed to Brigadier Wingate and became the British infantry element of his newly formed 77th Indian Infantry Brigade. The King's moved up to Saugor in the Central Provinces of India to commence training and Major Anderson was given command of No. 6 Column. Throughout the autumn months at Saugor, the men of the King's Regiment struggled to come to terms with the rigorous regime installed by Wingate and suffered greatly from sickness and disease. In the end it was decided to close down one of the King's columns and move the remaining men over to bolster the three surviving units. No. 6 Column was chosen and on the 26th December this unit was disbanded whilst the Brigade were stationed at Jhansi.

An extremely disgruntled Major Anderson was left to drown his sorrows at Jhansi, taking full part in Bernard Fergusson's Hogmanay celebrations a few nights later. Fergusson later remarked in his book, Beyond the Chindwin:

Gim Anderson was devastated to lose command of his column. He was then attached to Brigade Headquarters, where I found him one day not long after we had crossed the Chindwin in February 1943. He told me he did not think he was going to enjoy this placement one bit; he had no definite job and in his opinion was merely an extra Cipher Officer and bottle-washer.

As it turned out, Major Anderson did not have to wait long for a change of fortune. Around the beginning of March, as the Chindit Brigade approached their main points of attack along the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway, No. 4 Column had run in to difficulties. Disappointed with the performance of the then 4 Column Commander, Wingate relieved this officer of his command and sent his Brigade-Major, George Bromhead across to take control. In his place as Brigade-Major, Wingate promoted Gim Anderson and from this moment on he was involved in all decision making within the Brigade.

Three weeks later at a place called Baw, Wingate called an officers conference to discuss the Brigade's next move. In the end it was decided to call-off the operation and return to India with immediate effect. During this meeting, which took place on the 24th March, Bernard Fergusson once again found himself in the company of Major Anderson and they discussed their various plans for the return journey. Fergusson then confided in Anderson the names of the men from 5 Column who he believed should be recognised for the efforts on Operation Longcloth. He (Fergusson) feared that if he did not make it back, these men would never receive their just reward and requested that Anderson note the names down as extra insurance. Major Anderson was happy to oblige and duly recorded the names in his Army note book.

Major Anderson remained with Brigadier Wingate for the return journey to the Chindwin River. On 29th March, the Brigade had reached the village of Inywa on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy and looked out over the wide expanse of water with trepidation. As Columns 7 and 8 joined them on the shoreline, the commanders discussed the best way forward in getting their men across this most menacing of obstacles.

Some boats containing men from 7 Column began to make their way over to form a bridgehead, when suddenly from the far bank shots were heard as these boats came under attack from a large Japanese patrol. Most of the Chindits in the river were killed or drowned, but some made it over and quickly disappeared into the jungle beyond the western shore. Wingate, Major Anderson and column commanders Scott and Gilkes decided that the only option open to them was to withdraw and they melted away into the scrubland from whence they had just come. Gilkes and Scott decided to march away from the location almost immediately, but Wingate opted on finding a well concealed bivouac in the nearby woods at Tokpan Chaung and wait until things had quietened down.

During this time, which lasted for almost a week, Wingate prepared his group of around 40 men for dispersal. He also decided to relieve his men of all larger weapons and equipment in order to make their journey back to India as light-weight and speedy as possible. The other decision made at this point was to kill all the remaining mules, butchering them to supplement the depleted rations and to build up the men's strength for the long return trip to India. Being as always, a man of action, Wingate helped with the silent execution of the long suffering but ever loyal mules.

An extremely disgruntled Major Anderson was left to drown his sorrows at Jhansi, taking full part in Bernard Fergusson's Hogmanay celebrations a few nights later. Fergusson later remarked in his book, Beyond the Chindwin:

Gim Anderson was devastated to lose command of his column. He was then attached to Brigade Headquarters, where I found him one day not long after we had crossed the Chindwin in February 1943. He told me he did not think he was going to enjoy this placement one bit; he had no definite job and in his opinion was merely an extra Cipher Officer and bottle-washer.

As it turned out, Major Anderson did not have to wait long for a change of fortune. Around the beginning of March, as the Chindit Brigade approached their main points of attack along the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway, No. 4 Column had run in to difficulties. Disappointed with the performance of the then 4 Column Commander, Wingate relieved this officer of his command and sent his Brigade-Major, George Bromhead across to take control. In his place as Brigade-Major, Wingate promoted Gim Anderson and from this moment on he was involved in all decision making within the Brigade.

Three weeks later at a place called Baw, Wingate called an officers conference to discuss the Brigade's next move. In the end it was decided to call-off the operation and return to India with immediate effect. During this meeting, which took place on the 24th March, Bernard Fergusson once again found himself in the company of Major Anderson and they discussed their various plans for the return journey. Fergusson then confided in Anderson the names of the men from 5 Column who he believed should be recognised for the efforts on Operation Longcloth. He (Fergusson) feared that if he did not make it back, these men would never receive their just reward and requested that Anderson note the names down as extra insurance. Major Anderson was happy to oblige and duly recorded the names in his Army note book.

Major Anderson remained with Brigadier Wingate for the return journey to the Chindwin River. On 29th March, the Brigade had reached the village of Inywa on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy and looked out over the wide expanse of water with trepidation. As Columns 7 and 8 joined them on the shoreline, the commanders discussed the best way forward in getting their men across this most menacing of obstacles.

Some boats containing men from 7 Column began to make their way over to form a bridgehead, when suddenly from the far bank shots were heard as these boats came under attack from a large Japanese patrol. Most of the Chindits in the river were killed or drowned, but some made it over and quickly disappeared into the jungle beyond the western shore. Wingate, Major Anderson and column commanders Scott and Gilkes decided that the only option open to them was to withdraw and they melted away into the scrubland from whence they had just come. Gilkes and Scott decided to march away from the location almost immediately, but Wingate opted on finding a well concealed bivouac in the nearby woods at Tokpan Chaung and wait until things had quietened down.

During this time, which lasted for almost a week, Wingate prepared his group of around 40 men for dispersal. He also decided to relieve his men of all larger weapons and equipment in order to make their journey back to India as light-weight and speedy as possible. The other decision made at this point was to kill all the remaining mules, butchering them to supplement the depleted rations and to build up the men's strength for the long return trip to India. Being as always, a man of action, Wingate helped with the silent execution of the long suffering but ever loyal mules.

The next two weeks of arduous marching on generally empty stomachs took a great toll on the members of Wingate's dispersal party. Finally, on or around the 28th April, the group reached the eastern banks of the Chindwin River. To read in more depth about Brigadier Wingate's dispersal party and their three-week march from the Irrawaddy to the Chindwin River, please click on the following link: Wingate's Journey Home

On reaching the river, the men found not surprisingly, that all the main crossing points were heavily patrolled by the Japanese and that all boats had been removed from the various villages in the area. Out of desperation, Wingate decided he would attempt to swim the river alongside five other men, including Commando John Jefferies and Senior Burma Rifles officer, Aung Thin. After an epic struggle against the strong current and their own depleted physical condition, the six Chindits managed to cross the 600 torturous yards and reached the west bank.

Meanwhile, Major Anderson and the rest of the dispersal group had remained hidden in the jungle on the eastern banks of the river. It had been agreed that if Wingate and his companions succeeded in reaching the far bank and contacting Allied forces, they would arrange for boats to be sent over that evening to collect the remainder of the group.

From the book Wingate's Phantom Army, by Wilfred Burchett:

Major Anderson's men had stayed in their forest bivouac, where they rested till late afternoon. Then they edged forward through the path Wingate's party had made, arriving at the river bank an hour before dusk.

As soon as it was dark, Anderson cautiously displayed the signal with a lighted match cupped in his hand. There was no reply. Until after midnight, at regular intervals, he repeated the signal, but never a sign from the other bank. They were in a desperate position. The Japs must have a good idea of their whereabouts. It was impossible to travel far through this sea of reeds, and as far as they knew there were no villages within miles where they could obtain boats. Anderson concluded Wingate and his party must have been drowned or been shot up by Japs waiting on the other shore.

Four men, all weak swimmers, offered to try and get across and find out what was happening. In pitch darkness, they slipped off their jackets and boots and waded out into the gurgling river. Half an hour later, only one returned. The man alongside him had been swept away by the current and drowned. He didn't know what happened to the other two, but felt he couldn't make it, so turned back after travelling about 50 yards. The rest of the party stayed near the bank till dawn. Anderson repeated the signal at hourly intervals and as day began to break, marched the despairing men back through the reeds and made a fresh bivouac.

The following evening, Anderson collected up his men and set out for the river once more, struggling for a second time through the large area of reeds and marsh. Suddenly from behind them they heard shouts and looking back saw the Japanese setting fire to the reeds with flaming torches. Within minutes they were surrounded on three sides by the fast-flowing flames and thick choking smoke. There was still another 500 yards to the river and all seemed to be lost, when unexpectedly the wind changed direction and began to chase the flames away from the desperate Chindits and back towards the Japanese.

Major Anderson moved his men quickly away from the fire and closer to the waters edge. They then took a few minutes to take a drink and recover from their ordeal, before settling in an area of thick reeds. After posting guards to his rear, Anderson began signalling the far bank as he had done so the night before.

From the book, Wingate's Adventure also written by Wilfred Burchett:

Just before dusk, Anderson tried again. Was he dreaming, or perhaps going mad? Suddenly from the other side he thought he saw a flickering answer to his own signal. Yes, sure enough there it was again. Within a few seconds boats were pushing out from the opposite shore. Anderson called to his men, and by the time the boats had grounded they were all ready to pile in. Almost at once there was a ripple of automatic fire and bullets spat angrily into the sand around them. In the dim light they could see the Japanese running down the sandy banks about half a mile from where they stood. Mortars then opened up from the opposite bank pinning down the advancing Japanese and giving the escaping Chindits enough time to move out into the river.

After what seemed like an eternity, the boats reached the other side. Not a boat was hit, or a man wounded. Wingate was waiting on the beach as Anderson sprang ashore. 'What's the date today?' Anderson demanded almost the minute his feet touched the sand. 'April 29th', Wingate replied. 'Just as I thought, it is my birthday,' exclaimed Anderson. 'Well, many happy returns then,' replied Wingate.

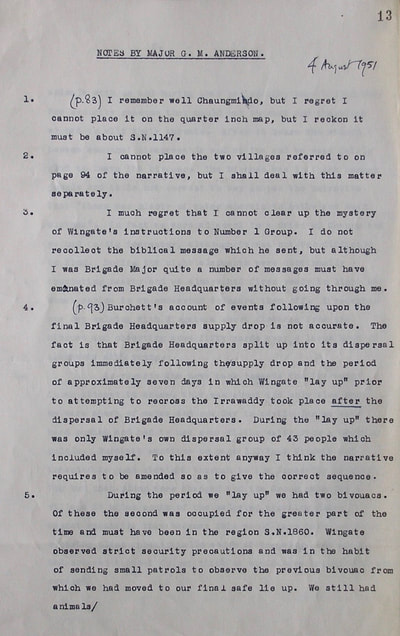

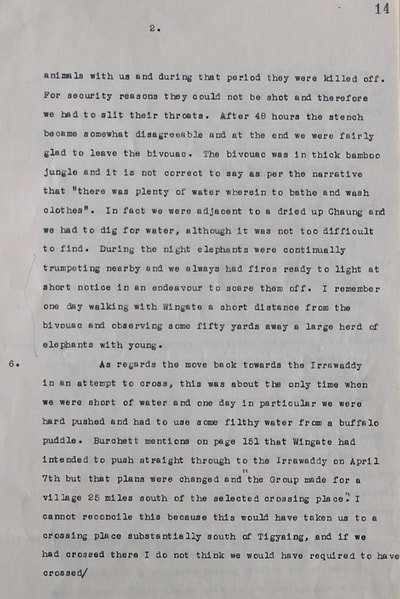

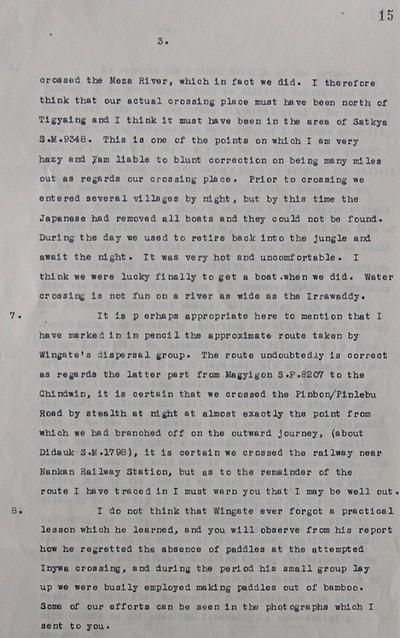

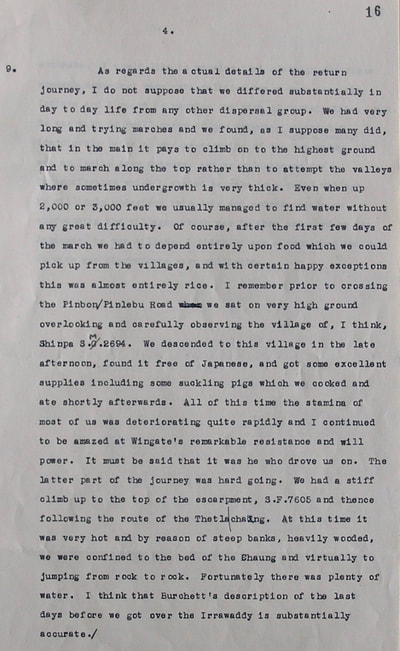

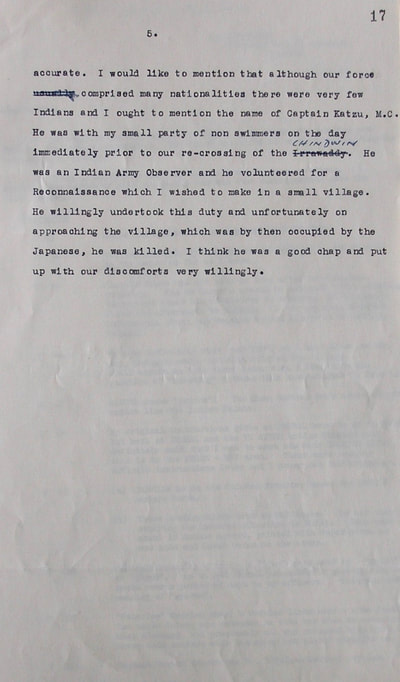

In August 1951, Gilmour Anderson was asked to examine the notes from the writings of author Wilfred Burchett, especially those pertaining to the first Chindit operation in 1943. This was mainly an exercise in ascertaining the accuracy of the books and the information contained within them. Shown below is his five-page report which was found in the Army document, CAB106/205, now held at the National Archives in London. I felt that although his debrief is somewhat after the event, it was worthwhile reproducing it here as an example of Anderson's viewpoint and feelings about his time on Operation Longcloth.

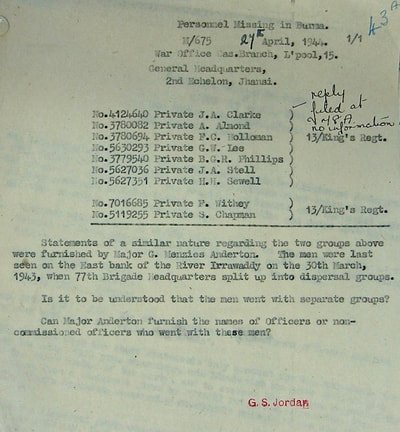

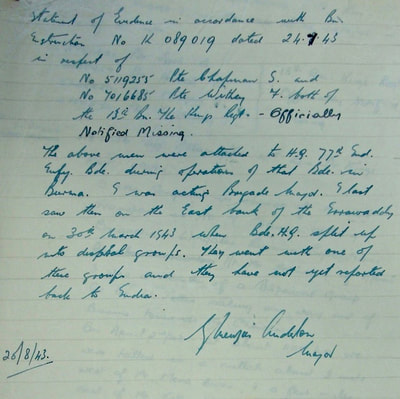

Also shown in the gallery are two witness statements given by Major Anderson on his return to India in 1943 and then further investigated by the Army Bureau in 1944. These concern the last known movements of men reported missing on Operation Longcloth, but especially those who were to become prisoners of war and who had made up the numbers of Wingate's Brigade Head Quarters. Major Anderson gave other similar reports to the ones shown below and I do wonder whether the men he takes great care to report as missing, were originally members of No. 6 Column, his own unit which had been disbanded in December 1942, just before the Brigade went into Burma. As always, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

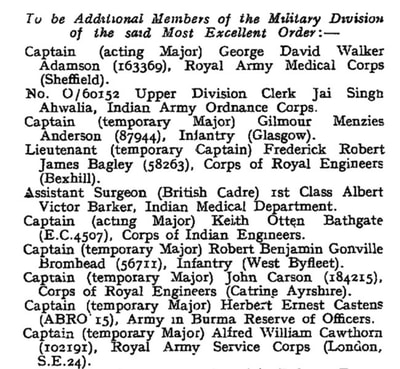

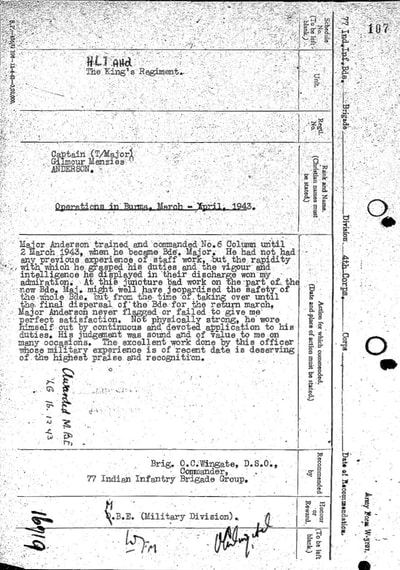

As already mentioned, Major Anderson was awarded the MBE for his efforts on Operation Longcloth and this was announced in the London Gazette on the 16th December 1943. The official recommendation was put forward by Brigadier Wingate and read:

Major Anderson trained and commanded No. 6 Column until the 2nd March, when he became Brigade-Major. He had no previous experience of staff work, but the rapidity with which he grasped his duties and the vigour and intelligence he displayed in their charge won my admiration. At this juncture, bad work on the part of any new Brigade-Major might well have jeopardised the safety of the whole Brigade, but from the time of taking over, until the final dispersal of the Brigade for the return march, Major Anderson never flagged of failed to give me perfect satisfaction. Not physically strong, he wore himself out by continuous and devoted application to his duties. His judgement was sound and of value to me on many occasions. The excellent work done by this officer whose military experience is of recent date is deserving of the highest praise and recognition.

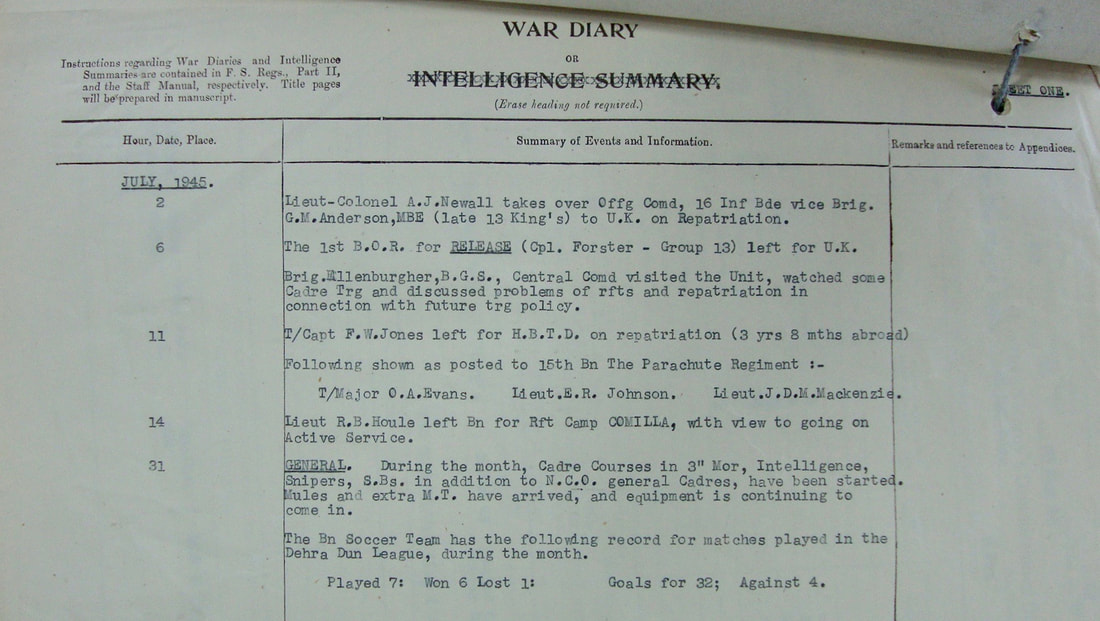

Gim Anderson was heavily involved in the planning and preparations for the second Chindit operation in 1944, but did not actually take part on the expedition itself. He was promoted to War Substantive Lt-Colonel on the 25th April 1944 and eventually assumed the role of Second-in-Command of the 16th British Infantry Brigade, as the returning Chindit columns were amalgamated at Dehra Dun for rest and recuperation, before being reallocated to various other units. By February 1945, he had attained the rank of Acting Brigadier and was now in full command of 16th Brigade. On the 2nd July 1945, he relinquished command of 16th Brigade to Lt-Colonel A.J. Newall of the King's Regiment and moved to the British Base Reinforcement Centre at Deolali for repatriation to the United Kingdom.

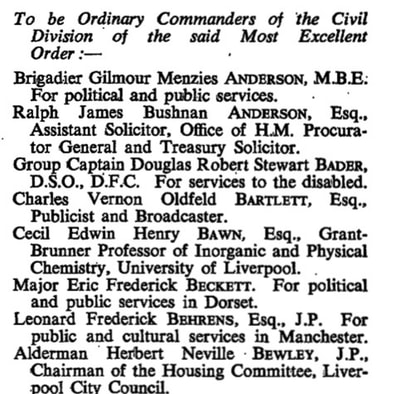

Gilmour Menzies Anderson left the British Army with the rank of Honorary Brigadier in 1945 and resumed his career in the political arena. He became the Chairman of the Glasgow Unionist Association in 1954 and became President of the Scottish Unionist Association in 1960. He was awarded the CBE in the New Year's Honours List of 1956 for his work in the political and public sectors. After holding the deputy position since 1965, he became the Chairman of the Scottish Conservative Party in 1967, a post he held for almost five years. In 1962, Gim Anderson was Knighted for his services to politics in Scotland.

Major Anderson trained and commanded No. 6 Column until the 2nd March, when he became Brigade-Major. He had no previous experience of staff work, but the rapidity with which he grasped his duties and the vigour and intelligence he displayed in their charge won my admiration. At this juncture, bad work on the part of any new Brigade-Major might well have jeopardised the safety of the whole Brigade, but from the time of taking over, until the final dispersal of the Brigade for the return march, Major Anderson never flagged of failed to give me perfect satisfaction. Not physically strong, he wore himself out by continuous and devoted application to his duties. His judgement was sound and of value to me on many occasions. The excellent work done by this officer whose military experience is of recent date is deserving of the highest praise and recognition.

Gim Anderson was heavily involved in the planning and preparations for the second Chindit operation in 1944, but did not actually take part on the expedition itself. He was promoted to War Substantive Lt-Colonel on the 25th April 1944 and eventually assumed the role of Second-in-Command of the 16th British Infantry Brigade, as the returning Chindit columns were amalgamated at Dehra Dun for rest and recuperation, before being reallocated to various other units. By February 1945, he had attained the rank of Acting Brigadier and was now in full command of 16th Brigade. On the 2nd July 1945, he relinquished command of 16th Brigade to Lt-Colonel A.J. Newall of the King's Regiment and moved to the British Base Reinforcement Centre at Deolali for repatriation to the United Kingdom.

Gilmour Menzies Anderson left the British Army with the rank of Honorary Brigadier in 1945 and resumed his career in the political arena. He became the Chairman of the Glasgow Unionist Association in 1954 and became President of the Scottish Unionist Association in 1960. He was awarded the CBE in the New Year's Honours List of 1956 for his work in the political and public sectors. After holding the deputy position since 1965, he became the Chairman of the Scottish Conservative Party in 1967, a post he held for almost five years. In 1962, Gim Anderson was Knighted for his services to politics in Scotland.

Gilmour Menzies Anderson sadly passed away on the 12th December 1977 whilst at Gartnavel Hospital in Glasgow. From the pages of the Glasgow Herald:

Gilmour Menzies Anderson dies aged 63

Sir Gilmour Menzies Anderson, who as chairman restructured the Conservative Party organisation in Scotland, died yesterday. He was 63.

Sir Gilmour, who had been deputy chairman of the party for two years, was appointed full chairman in 1967 by Edward Heath, the then party leader. Three years later he announced a streamlining of the party which kept Central Office in Edinburgh and also led to the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Association offices being transferred to Edinburgh from Glasgow. He was the first chairman of the party in Scotland who had been president of the SCUA. He gave up his chairmanship in 1971.

Previously he had been chairman of the Glasgow Unionist Association from 1954-57, and president of the Scottish Unionist Association from 1960-61. A partner in a Glasgow law firm, Anderson was educated at the High School of Glasgow and Glasgow University. He was a member of the Glasgow Corporation and became the youngest Progressive Councillor in 1938. He then served again after the war.

He was commissioned in the 6th Highland Light Infantry (TA) in 1939 and as Brigade-Major to the late General Wingate, served with the Chindits in India and Burma from 1942-45. As the Army’s youngest Brigadier he commanded the 16th British Infantry Brigade in 1945. He was appointed MBE in 1943, CBE in 1956 and was knighted in 1962 for political and public services. Sir Gilmour was president elect of the Glasgow Phoenix Angling Club.

Sir Gilmour’s sudden and untimely death comes as a great shock to his many friends. The heights he scaled in his varied career are already on record here and need no further embellishment. He was a man of many talents. He was also a man of sympathy, of understanding and of great friendliness. In his business life as a lawyer, he was at heart a countryman with a liking and deep appreciation of all that was therein involved.

A keen and expert angler, few in Scotland threw a better line and he tied the most enticing flies which his friends were ever eager to borrow. He was a good shot, effective without being ostentatious, a keen bird-watcher, a dog lover, so evident in his care for his beloved Labrador, Meg and an entertaining conversationalist over a dram or two after a day on the river. These are the things for which he will be remembered by his close friends and family, all of whom will miss him greatly.

Gilmour Menzies Anderson dies aged 63

Sir Gilmour Menzies Anderson, who as chairman restructured the Conservative Party organisation in Scotland, died yesterday. He was 63.

Sir Gilmour, who had been deputy chairman of the party for two years, was appointed full chairman in 1967 by Edward Heath, the then party leader. Three years later he announced a streamlining of the party which kept Central Office in Edinburgh and also led to the Scottish Conservative and Unionist Association offices being transferred to Edinburgh from Glasgow. He was the first chairman of the party in Scotland who had been president of the SCUA. He gave up his chairmanship in 1971.

Previously he had been chairman of the Glasgow Unionist Association from 1954-57, and president of the Scottish Unionist Association from 1960-61. A partner in a Glasgow law firm, Anderson was educated at the High School of Glasgow and Glasgow University. He was a member of the Glasgow Corporation and became the youngest Progressive Councillor in 1938. He then served again after the war.

He was commissioned in the 6th Highland Light Infantry (TA) in 1939 and as Brigade-Major to the late General Wingate, served with the Chindits in India and Burma from 1942-45. As the Army’s youngest Brigadier he commanded the 16th British Infantry Brigade in 1945. He was appointed MBE in 1943, CBE in 1956 and was knighted in 1962 for political and public services. Sir Gilmour was president elect of the Glasgow Phoenix Angling Club.

Sir Gilmour’s sudden and untimely death comes as a great shock to his many friends. The heights he scaled in his varied career are already on record here and need no further embellishment. He was a man of many talents. He was also a man of sympathy, of understanding and of great friendliness. In his business life as a lawyer, he was at heart a countryman with a liking and deep appreciation of all that was therein involved.

A keen and expert angler, few in Scotland threw a better line and he tied the most enticing flies which his friends were ever eager to borrow. He was a good shot, effective without being ostentatious, a keen bird-watcher, a dog lover, so evident in his care for his beloved Labrador, Meg and an entertaining conversationalist over a dram or two after a day on the river. These are the things for which he will be remembered by his close friends and family, all of whom will miss him greatly.

I have been extremely fortunate to have made contact with two of Gilmour Menzies Anderson's grandchildren. Firstly, in February 2014, from grandson Gordon Drysdale:

Dear Steve

I am Gilmour Menzies Anderson's grandson. I am keen to contact and meet any surviving Chindits who may have known my grandfather in Burma and India. Grandpa did not go into Burma on the second Chindit operation. I am told by my mother (his daughter) that he was much involved in the planning and running of the second operation from India and he then returned to the UK at the end of hostilities. However, I am most interested to learn more about this period of his war. I was delighted to discover your excellent site today, I have over the years read much about the Chindits, but I now wish I had endeavoured to meet some of these gentlemen many years ago. Sadly, I never knew Grandpa.

Very much hoping to make contact with you. Regards Gordon Drysdale.

In October 2017, I was pleased to receive an email from another grandson, Alistair Menzies Anderson:

I just wanted to say thanks for taking such enormous amount of effort to compile all this information on your remarkable website. As you might guess from my name, I'm the grandson of Major Gilmour Menzies Anderson, who unfortunately died aged 63 of a stroke in the late 1970's. I don't really have much to add to your incredible collection of stories because he was a very respectful amazing man who pretty much refused to talk about the war, citing repeatedly that it was too horrible to discuss.

The only thing I can recall, from a brief discussion with him, was how he thought that General Wingate was a brilliant commander and heard the story of the time when they were trapped against the Chindwin River trying to escape the Japanese and how they had to hide in the marshes for hours, soaking wet up to their necks and sometimes even hiding underwater. I could sense his enormous loss for the men he was trying to lead to freedom back then, it was as if he blamed himself. He was always so humble about his own achievements.

He went on to become a Brigadier after Wingate was killed and then to have quite a distinguished life post-war. He was enormously proud of being in the Chindits. I know he also maintained his friendship with Major Bernard Fergusson, a fellow Scot, who I think lived near the Lake of Menteith in Scotland. My Aunt, his daughter, still lives in Bearsden near Glasgow. I am looking forward to reading my way through the rest of the site and all the various stories. Sorry I can't be more informative for you.

Thanks again and kind regards. Alistair.

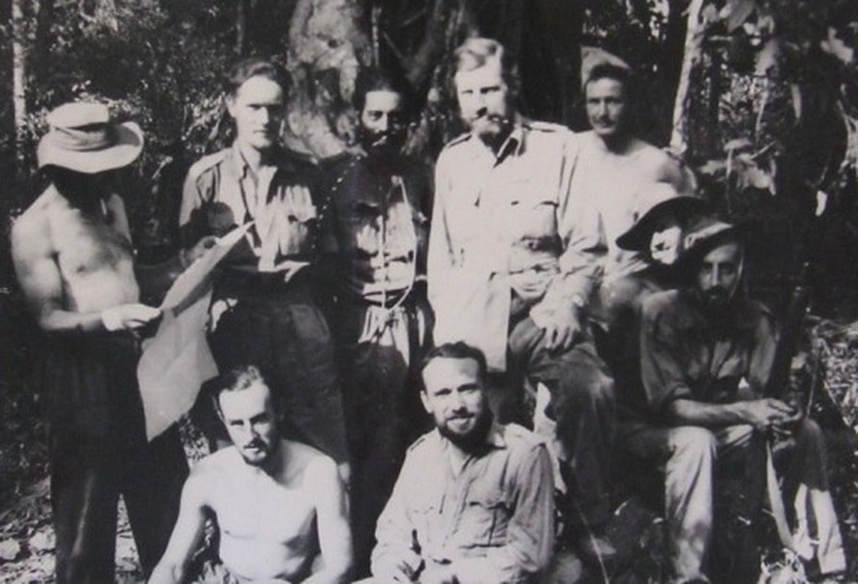

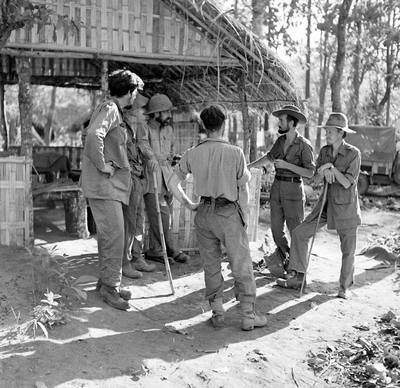

I would like to thank both Gordon and Alistair for their contact and support in bringing this story to these website pages. Seen below is a final gallery of images relating to the above narrative, including some wonderful photographs of Major Anderson and Brigadier Wingate in deep discussion post Operation Longcloth. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Dear Steve

I am Gilmour Menzies Anderson's grandson. I am keen to contact and meet any surviving Chindits who may have known my grandfather in Burma and India. Grandpa did not go into Burma on the second Chindit operation. I am told by my mother (his daughter) that he was much involved in the planning and running of the second operation from India and he then returned to the UK at the end of hostilities. However, I am most interested to learn more about this period of his war. I was delighted to discover your excellent site today, I have over the years read much about the Chindits, but I now wish I had endeavoured to meet some of these gentlemen many years ago. Sadly, I never knew Grandpa.

Very much hoping to make contact with you. Regards Gordon Drysdale.

In October 2017, I was pleased to receive an email from another grandson, Alistair Menzies Anderson:

I just wanted to say thanks for taking such enormous amount of effort to compile all this information on your remarkable website. As you might guess from my name, I'm the grandson of Major Gilmour Menzies Anderson, who unfortunately died aged 63 of a stroke in the late 1970's. I don't really have much to add to your incredible collection of stories because he was a very respectful amazing man who pretty much refused to talk about the war, citing repeatedly that it was too horrible to discuss.

The only thing I can recall, from a brief discussion with him, was how he thought that General Wingate was a brilliant commander and heard the story of the time when they were trapped against the Chindwin River trying to escape the Japanese and how they had to hide in the marshes for hours, soaking wet up to their necks and sometimes even hiding underwater. I could sense his enormous loss for the men he was trying to lead to freedom back then, it was as if he blamed himself. He was always so humble about his own achievements.

He went on to become a Brigadier after Wingate was killed and then to have quite a distinguished life post-war. He was enormously proud of being in the Chindits. I know he also maintained his friendship with Major Bernard Fergusson, a fellow Scot, who I think lived near the Lake of Menteith in Scotland. My Aunt, his daughter, still lives in Bearsden near Glasgow. I am looking forward to reading my way through the rest of the site and all the various stories. Sorry I can't be more informative for you.

Thanks again and kind regards. Alistair.

I would like to thank both Gordon and Alistair for their contact and support in bringing this story to these website pages. Seen below is a final gallery of images relating to the above narrative, including some wonderful photographs of Major Anderson and Brigadier Wingate in deep discussion post Operation Longcloth. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 20/06/2024.

In late 1944, (most likely November), the now Colonel Menzies Anderson was officer commanding Special Force Training Wing and led a fifteen-day course for Chindit officers in such exercises as: dispersal drill, deception & concealment, ambush tactics and supply drop organisation. The document shown below was found amongst the private papers of Colonel M.V. Liakhovsky, a Polish officer with the 6th Battalion, the Nigeria Regiment on Operation Thursday. Presumably, Liakhovsky was an attendee of the officers course led by Colonel Menzies Anderson. To read more about Michael Victor Liakhovsky, please follow the link to the Imperial War Museum website here: www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1030046152

I would like to thank Sue Langabeer, a fellow Burma campaign researcher, for bringing to my attention both the document below and the papers of Colonel Liakhovsky at the Imperial War Museum. Please click on the image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, March 2018.