Major John B. Jefferies, Wingate's Doppelgänger

"The last time I swam in the Chindwin was on the way out last year, when John Jefferies nearly drowned."

Orde Wingate speaking with Bernard Fergusson in March 1944.

Orde Wingate speaking with Bernard Fergusson in March 1944.

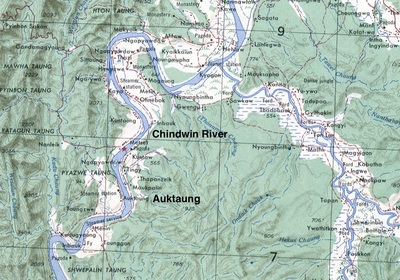

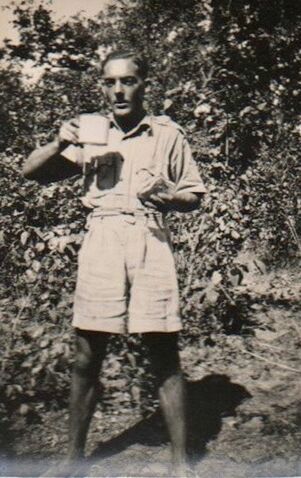

John B. Jefferies inside Burma, April 1943.

John B. Jefferies inside Burma, April 1943.

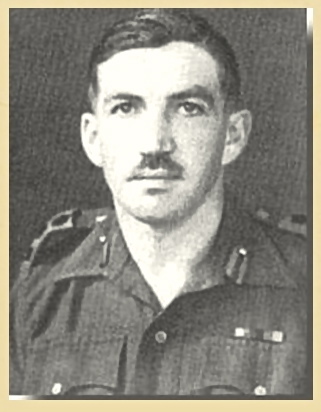

In amongst Longcloth folklore Major John B. Jefferies is probably most famous for masquerading as Brigadier Wingate during the first half of the Chindit operation in 1943. Leading his 'deception' squad and as part of Southern Group, Jefferies paraded openly through the Burmese jungles just east of the Chindwin River, visiting local villages and delivering a never ending supply of mis-information, whilst all the while dressed in the uniform of a fully fledged Brigadier.

Jefferies had already served with Special Forces during WW2 and was in every sense of the word an unconventional soldier. From his book 'Safer than a Known Way', author and former Gurkha officer, Ian Machorton provides some background on John Jefferies:

The two Chindit groups had split up just south of Tamu whence we, the decoys, marched on boldly by day while the main body lay low during the light hours and marched only by night. An even more ostentatious approach towards Jap-held territory was made by a still smaller party which split off from Colonel Alexander's force (Southern Group) immediately we had crossed the Chindwin. This, led by Major John Jefferies grandly dressed up as a Brigadier, headed deliberately for a village of which the headman was known to be a very willing tool of the Japanese.

John Jefferies was quite a character, by anyone's standards. An Irishman, it was perhaps quite typical of him that he should have started his professional service career in the Royal Navy, and was in line for promotion to Lieutenant-Commander when he decided to resign his commission to go into business.

When the Second World War broke out he was doing very well with a chain of super petrol stations around Southampton and Portsmouth, but he straight away volunteered for the Navy. When told it would be several months before he could be assigned to a warship for active war service, John Jefferies could not wait. He joined up as a Private in the Royal Ulster Rifles, with whom he served in the ranks for six months before being commissioned.

It was only natural that he should have volunteered for the Commandos and took part in the Lofoten Islands raids off the coast of Norway. It was also only natural that he should have volunteered for an unspecified special duty in the Far East just at the time the enemy there were right in the ascendancy. Thus he turned up in the Wingate circus.

Major John Jefferies was not content with being just a Brigadier when he marched into the pro-Jap village across the Chindwin. In a deep, dark spot in the jungle before he arrived there, he halted and decked himself out with the full insignia of a General, red tabs, hatband and all. Once in the village with his "staff officers" he lost no time in billeting himself in the traitorous headman's house. He lost even less time in pulling out important looking campaign maps and discussing the best tracks to use for the movement of a big force of British far south down the Chindwin. The headman was extremely helpful, and then undoubtedly sent runners hot-foot to warn the Japs of this strong thrust to be aimed at them far to the south. Having had lots of fun, John Jefferies and his deceptionists marched off and back into the jungle from whence they had come.

Before his attachment to the ranks of 142 Commando and meeting Wingate, Major Jefferies had taken part in the 204 Military Mission into the Yunnan Provinces of China. This mission, involving soldiers from both Britain and Australia was put together to train and support the Chinese Army in their actions against the Japanese. Many of the survivors from 204 Mission were eventually co-opted into the newly formed 142 Commando, the specialist unit for 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, commanded initially by Mike Calvert. John arrived at the Saugor training camp in the Central Provinces of India on the 16th September 1942 and began his Chindit odyssey. As time went on and with Calvert now required to lead 3 Column, Jefferies was ordered to assume command of 142 Commando on the 5th January 1943, just as the Chindit Brigade were preparing to move up to Imphal in Assam and commence their sojourn behind enemy lines.

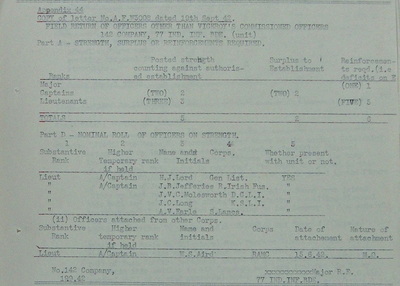

Seen below are some images in relation to the first part of this story, including the official notification of Jefferies promotion to Major and command of 142 Commando. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Jefferies had already served with Special Forces during WW2 and was in every sense of the word an unconventional soldier. From his book 'Safer than a Known Way', author and former Gurkha officer, Ian Machorton provides some background on John Jefferies:

The two Chindit groups had split up just south of Tamu whence we, the decoys, marched on boldly by day while the main body lay low during the light hours and marched only by night. An even more ostentatious approach towards Jap-held territory was made by a still smaller party which split off from Colonel Alexander's force (Southern Group) immediately we had crossed the Chindwin. This, led by Major John Jefferies grandly dressed up as a Brigadier, headed deliberately for a village of which the headman was known to be a very willing tool of the Japanese.

John Jefferies was quite a character, by anyone's standards. An Irishman, it was perhaps quite typical of him that he should have started his professional service career in the Royal Navy, and was in line for promotion to Lieutenant-Commander when he decided to resign his commission to go into business.

When the Second World War broke out he was doing very well with a chain of super petrol stations around Southampton and Portsmouth, but he straight away volunteered for the Navy. When told it would be several months before he could be assigned to a warship for active war service, John Jefferies could not wait. He joined up as a Private in the Royal Ulster Rifles, with whom he served in the ranks for six months before being commissioned.

It was only natural that he should have volunteered for the Commandos and took part in the Lofoten Islands raids off the coast of Norway. It was also only natural that he should have volunteered for an unspecified special duty in the Far East just at the time the enemy there were right in the ascendancy. Thus he turned up in the Wingate circus.

Major John Jefferies was not content with being just a Brigadier when he marched into the pro-Jap village across the Chindwin. In a deep, dark spot in the jungle before he arrived there, he halted and decked himself out with the full insignia of a General, red tabs, hatband and all. Once in the village with his "staff officers" he lost no time in billeting himself in the traitorous headman's house. He lost even less time in pulling out important looking campaign maps and discussing the best tracks to use for the movement of a big force of British far south down the Chindwin. The headman was extremely helpful, and then undoubtedly sent runners hot-foot to warn the Japs of this strong thrust to be aimed at them far to the south. Having had lots of fun, John Jefferies and his deceptionists marched off and back into the jungle from whence they had come.

Before his attachment to the ranks of 142 Commando and meeting Wingate, Major Jefferies had taken part in the 204 Military Mission into the Yunnan Provinces of China. This mission, involving soldiers from both Britain and Australia was put together to train and support the Chinese Army in their actions against the Japanese. Many of the survivors from 204 Mission were eventually co-opted into the newly formed 142 Commando, the specialist unit for 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, commanded initially by Mike Calvert. John arrived at the Saugor training camp in the Central Provinces of India on the 16th September 1942 and began his Chindit odyssey. As time went on and with Calvert now required to lead 3 Column, Jefferies was ordered to assume command of 142 Commando on the 5th January 1943, just as the Chindit Brigade were preparing to move up to Imphal in Assam and commence their sojourn behind enemy lines.

Seen below are some images in relation to the first part of this story, including the official notification of Jefferies promotion to Major and command of 142 Commando. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Major Jefferies' contribution during the first half of Operation Longcloth was clearly crucial in throwing the Japanese of the scent and allowing Wingate and Northern Group to make their way to the Myitkhina-Mandalay railway unmolested. His actual pathway is recounted in the book 'Wingate's Raiders', by Charles J. Rolo. Apologies for some repetition of information in the following account, however, I feel it is worthwhile to include it as part of the overall narrative:

At the Burma-Assam border one section of Wingate's force, acting as a decoy group, struck south. It consisted of two columns, led by Major Arthur Emmett and Major George Dunlop, and a ' deception group,' under the command of Major John B. Jefferies, who had crossed the river with Colonel Alexander and his Head Quarters. Its task was to divert the Japanese from the main body of the expedition and to deceive the enemy into believing that the British were driving in force towards the lower Chindwin.

A day's march brought the Southern Force to its last food dump. Here the men ate their last field service rations of bully beef stew with bacon, potatoes and onions, tinned fruit, tea, bread, butter and jam. At this point Wingate paid them a surprise farewell visit and wished them good luck.

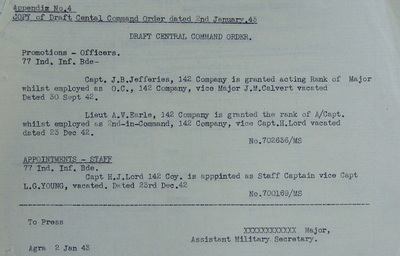

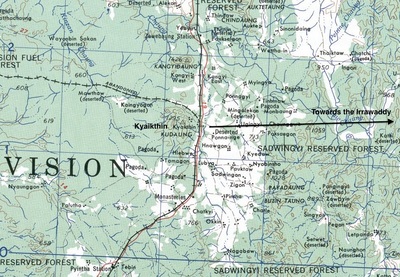

After two day's march from the Chindwin, they stopped for a supply-dropping and took a second on the following day, February 15th, making no attempt at concealment, with the deliberate intention of drawing attention to themselves. They crossed the Chindwin without incident at Auktaung, forty miles due south of the main body under Wingate on the nights of February 15th and 16th. They were agreeably surprised at the pleasure shown by the villagers, who gladly provided boats and helped them with the loading.

After the crossing they marched due south throughout the day, but that night their main body headed off to the east while Jefferies' deception group continued southward on a crucial assignment. Even in Wingate's Circus, which contained a generous assortment of unusual people, Jefferies was a unique phenomenon; a professional Navy man in the uniform of a Major in the Royal Irish Fusiliers. His home was Wexford in Southern Ireland. After graduating from Dartmouth Naval College he served nine years in the Royal Navy, and was approaching the rank of Lieutenant-Commander when he decided to resign his commission to go into business.

He started a chain of American-style super service petrol stations in the South of England, and in a year had built up the biggest business in the Portsmouth-Southampton area. When war broke out Jefferies at once volunteered for service in the Navy. The Navy was already swamped with enlistments, and he was told it would be some time before he could be assigned to a ship. He marched to the nearest Army recruiting office and joined up as a private in the Royal Ulster Rifles. He served six months in the ranks, was commissioned as a second lieutenant, and applied for service in the paratroops.

He was taken instead into the Commandos in August 1940, and saw action in the raids on the Lofoten Islands, off Norway. After several more Commando jobs he volunteered for special duty in the Far East, and found himself attached to Brigadier Wingate's raiding force as an expert in demolition.

Jefferies led his small deception group towards a village whose headman was known to have pro-Japanese sympathies and could be relied upon to relay information to the enemy. In the jungle, some distance from the village, he halted and pulled out of his pack a handful of military insignia. A little while later a red-tabbed General and his Staff officers entered the village and commandeered the Thugyi's (Headman) house, politely informing the headman's family that there was no need for them to leave.

Then, with carefully calculated indiscretion, Jefferies proceeded to give the impression that this was the headquarters of a large expedition heading due south. He pored over maps, mentioning the names of villages to the south. He asked about tracks and food supplies in the south, and about Japanese troop concentrations in that area. He dictated orders to mythical battalions. All the while his officers, with an air of great importance, brought in a constant stream of messages, which Jefferies read with a suitably grave expression.

The acting was good and the actors were thoroughly enjoying the play. One officer solemnly handed Jefferies a message which read: You have been invited to dine with Lady Snodgrass. 8 P.M., February 25th. Black tie is to be worn. Another brought in a chit which announced that he had drawn the favourite horse in the Irish Sweepstake. A third mysteriously produced an ancient cable from Jefferies' bank informing him that his account was slightly overdrawn. The latter caused the General's face to twitch so violently that the watchful Burmese must have imagined momentous doings were afoot. Regretfully Jefferies rang down the curtain with a message of thanks to the traitor's family. Then his party marched off with great dignity into the jungle, and next day caught up with the main body of the Southern Force, which had been moving east.

A forward party commanded by Captain Vivian Weatherall had already drawn blood. Picking their way through the jungle, Weatherall's men ambushed a Japanese patrol about twenty strong, marching jauntily along a track. They were right on their toes and picked off seven Japanese without suffering any casualties. The Japs, the Chindits were to discover, though individually good soldiers, were particularly slovenly about their reconnaissance. Time and again Wingate's men ambushed them sauntering through the jungle with their rifles slung over their shoulders as casually as though they were taking a walk in Tokyo.

From Burmese villagers the Chindits learned that the Japanese were in great strength in the area, which meant that the feint was succeeding in drawing the enemy's attention away from the Northern Force responsible for destroying the most important section of the railway. However, survivors from the Japanese patrol that had bumped into Weatherall's men must have reported that a British force was now heading east, and Jefferies, fearing that the deception plan might have been compromised, led a party off on a wide detour to the south to make false inquiries and plant false information about their movements.

After several days of marching and counter-marching Jefferies felt that the deception plan had been fully carried out, and set a course due east. He had previously arranged to catch up with the rest of the Southern Force for a supply-drop at a rendezvous roughly midway between the Chindwin and Kyaikthin, the point selected for one of the attacks on the Mandalay-Myitkyina railway. Major Dunlop's column was to cut the line roughly fifteen miles to the north. The deception plan, Intelligence reports disclosed later, was completely successful. The Japanese duly massed troops in the lower Chindwin area, and wasted two weeks combing the countryside for a British Army which, to their utter bewilderment, they could not find.

By the time we started heading for the rendezvous, Jefferies afterwards related, we had exhausted our supplies and were desperately in need of food. We couldn't ask for a supply-dropping, because we hadn't got a wireless set with us. Taking along an extra mule to carry the set, a wireless operator, batteries, and what not would have slowed us down too much. In any case, a supply-drop was really out of the question. It would have brought the Japs down on us, and might have wrecked the whole deception plan.

I decided there was nothing for it but to stalk a village I had picked out on the map. The captured enemy operational orders which the Brigadier had read to us at Imphal, showed that the Japanese were in the habit of sending out whole garrisons to hunt for our men when we sent patrols over the Chindwin. I felt there was a good chance we might find the village unguarded. I took along with me Corporal Hayes and a couple of men armed with hand grenades. Corporal Hayes, a red-haired, freckle-faced young giant, was plagued with an outsize appetite, he'd polish off three days rations between breakfast and supper and still grumble he was hungry.

NB. This was 5182207 Corporal F. Hayes formerly of the Gloucestershire Regiment, who had moved over to 142 Commando from the Bush Warfare School based at Maymyo on the 31st July 1942.

Jefferies continues:

Near the edge of the jungle not far from our target we came upon a small river, and beyond it we spotted through the trees a ridge that looked like a Jap sentry post. We saw smoke rising and could just catch the sound of voices. I posted two of my men in a firing position, crossed the river higher up with Corporal Hayes and started to stalk the sentry post. A ditch full of wet slime led up to the foot of the ridge and we had to go forward very slowly.

I think it must have taken us thirty minutes to advance thirty yards. When we were just under the ridge, I whispered to Hayes, "Get ready to rush them." Holding a grenade in one hand and a rifle in the other we shot out of the ditch with what we hoped were bloodcurdling cries. Sitting around a small fire, placidly eating their supper were five Burmese woodcutters. They gaped at us for a moment, then politely held out a dish of rice.

The woodcutters told us that the village was the headquarters of a Jap garrison of about fifty men, who at the moment were away hunting for us, just as I had hoped. Apparently they hadn't even left behind any pickets. I sent one of the Burmese into the village to buy food, and led my party back across the river in the jungle, just in case the natives had a trick up their sleeve. We were sitting by a clump of bamboo, from which we could watch the path down from the village, when a small dog trotted up and sniffed at our boots.

Just then I heard what sounded like shouted orders in Japanese or Burmese. The voice came from the other side of the river quite close to us. There didn't seem to be any way of escape. We couldn't move a foot through the undergrowth without being heard at that distance. It was one of the nastiest moments I can remember. My heart was beating like the drums of hell. Then we caught sight of the enemy, two Burmese peasants urging a herd of buffalo across the river.

Shortly afterwards, fourteen villagers arrived, carrying on their heads enormous baskets filled with curried fish, curried rice and vegetables, chickens, eggs, and bananas. It was the dinner they had been cooking for the Japanese garrison. I wonder what story they told the Japs when the garrison got back and found the larder had been cleaned out! We collected the rest of the deception group, wolfed what we could on the spot, and loaded what was left on to the mules. After a square meal I was tempted to lay an ambush for the returning Japs, but the Burmese had given us information about a more worth-while target, a village some distance to the east in which the Japanese were working surface oil wells.

We pushed on expecting to reach the village the next night, but ran into a stretch of really hellish jungle. We still didn't want the Japs to find out that we were heading east as they were looking for us to the south, so we kept clear of the beaten tracks, hacking our way through the densely matted undergrowth. In parts the jungle was so thick and steep that we had to build a path for the mules, and sometimes we had to unload them and manhandle their loads. It took us three days to cover fifteen miles.

The food we'd pinched from the enemy ran out excepting for the rice, which unfortunately had been cooked for the Japs and quickly turned sour. We kept going on a few handfuls a day of sour rice. Some of the men chewed on dry jungle roots. We weren't sure whether they were poisonous, but we were in no position to be fussy. Just before dusk on the third day of marching we came upon a small patch of bamboo forest on the top of a hill. We hadn't had a drop of water for nearly thirty-six hours and spent the last hour of daylight frantically slitting open hollow bamboos to see if there was any liquid in them. They were dry as a bone.

That night it seemed incredible that in London, New York or Delhi anyone could just stroll into a bar and drink as much beer as he wanted. I felt as if I'd been thirsty all my life. The hillside dropped steeply into a narrow valley and all the next morning we hunted for a way down for the mules. Eventually we man-handled the mule loads and the animals slid down the hillside on their haunches.

By this time we were desperate for water. An hour before dark we found a stream. The water was beautifully cool and clear; we drank like thirsty camels, then we bathed, watered the mules, and slept until dawn. We were now two and a half days march from the supply-dropping rendezvous, but forty-eight hours behind schedule. By forced marching we covered the distance in a day and a half, and learned from villagers we had only just missed the rest of our force, which had taken a dropping that morning.

We couldn't march another step and bivouacked for the night. The next morning we combed every foot of the dropping zone for any odds and ends that might have been left behind. We found about a dozen packages of dates. The next four days we lived on dates and sour rice, racing to catch up with Emmett's column which was heading for the railway at Kyaikthin. On March 2nd we joined up with them at a point three miles from Kyaikthin station. That same night we were scheduled to blow up the line.

At the Burma-Assam border one section of Wingate's force, acting as a decoy group, struck south. It consisted of two columns, led by Major Arthur Emmett and Major George Dunlop, and a ' deception group,' under the command of Major John B. Jefferies, who had crossed the river with Colonel Alexander and his Head Quarters. Its task was to divert the Japanese from the main body of the expedition and to deceive the enemy into believing that the British were driving in force towards the lower Chindwin.

A day's march brought the Southern Force to its last food dump. Here the men ate their last field service rations of bully beef stew with bacon, potatoes and onions, tinned fruit, tea, bread, butter and jam. At this point Wingate paid them a surprise farewell visit and wished them good luck.

After two day's march from the Chindwin, they stopped for a supply-dropping and took a second on the following day, February 15th, making no attempt at concealment, with the deliberate intention of drawing attention to themselves. They crossed the Chindwin without incident at Auktaung, forty miles due south of the main body under Wingate on the nights of February 15th and 16th. They were agreeably surprised at the pleasure shown by the villagers, who gladly provided boats and helped them with the loading.

After the crossing they marched due south throughout the day, but that night their main body headed off to the east while Jefferies' deception group continued southward on a crucial assignment. Even in Wingate's Circus, which contained a generous assortment of unusual people, Jefferies was a unique phenomenon; a professional Navy man in the uniform of a Major in the Royal Irish Fusiliers. His home was Wexford in Southern Ireland. After graduating from Dartmouth Naval College he served nine years in the Royal Navy, and was approaching the rank of Lieutenant-Commander when he decided to resign his commission to go into business.

He started a chain of American-style super service petrol stations in the South of England, and in a year had built up the biggest business in the Portsmouth-Southampton area. When war broke out Jefferies at once volunteered for service in the Navy. The Navy was already swamped with enlistments, and he was told it would be some time before he could be assigned to a ship. He marched to the nearest Army recruiting office and joined up as a private in the Royal Ulster Rifles. He served six months in the ranks, was commissioned as a second lieutenant, and applied for service in the paratroops.

He was taken instead into the Commandos in August 1940, and saw action in the raids on the Lofoten Islands, off Norway. After several more Commando jobs he volunteered for special duty in the Far East, and found himself attached to Brigadier Wingate's raiding force as an expert in demolition.

Jefferies led his small deception group towards a village whose headman was known to have pro-Japanese sympathies and could be relied upon to relay information to the enemy. In the jungle, some distance from the village, he halted and pulled out of his pack a handful of military insignia. A little while later a red-tabbed General and his Staff officers entered the village and commandeered the Thugyi's (Headman) house, politely informing the headman's family that there was no need for them to leave.

Then, with carefully calculated indiscretion, Jefferies proceeded to give the impression that this was the headquarters of a large expedition heading due south. He pored over maps, mentioning the names of villages to the south. He asked about tracks and food supplies in the south, and about Japanese troop concentrations in that area. He dictated orders to mythical battalions. All the while his officers, with an air of great importance, brought in a constant stream of messages, which Jefferies read with a suitably grave expression.

The acting was good and the actors were thoroughly enjoying the play. One officer solemnly handed Jefferies a message which read: You have been invited to dine with Lady Snodgrass. 8 P.M., February 25th. Black tie is to be worn. Another brought in a chit which announced that he had drawn the favourite horse in the Irish Sweepstake. A third mysteriously produced an ancient cable from Jefferies' bank informing him that his account was slightly overdrawn. The latter caused the General's face to twitch so violently that the watchful Burmese must have imagined momentous doings were afoot. Regretfully Jefferies rang down the curtain with a message of thanks to the traitor's family. Then his party marched off with great dignity into the jungle, and next day caught up with the main body of the Southern Force, which had been moving east.

A forward party commanded by Captain Vivian Weatherall had already drawn blood. Picking their way through the jungle, Weatherall's men ambushed a Japanese patrol about twenty strong, marching jauntily along a track. They were right on their toes and picked off seven Japanese without suffering any casualties. The Japs, the Chindits were to discover, though individually good soldiers, were particularly slovenly about their reconnaissance. Time and again Wingate's men ambushed them sauntering through the jungle with their rifles slung over their shoulders as casually as though they were taking a walk in Tokyo.

From Burmese villagers the Chindits learned that the Japanese were in great strength in the area, which meant that the feint was succeeding in drawing the enemy's attention away from the Northern Force responsible for destroying the most important section of the railway. However, survivors from the Japanese patrol that had bumped into Weatherall's men must have reported that a British force was now heading east, and Jefferies, fearing that the deception plan might have been compromised, led a party off on a wide detour to the south to make false inquiries and plant false information about their movements.

After several days of marching and counter-marching Jefferies felt that the deception plan had been fully carried out, and set a course due east. He had previously arranged to catch up with the rest of the Southern Force for a supply-drop at a rendezvous roughly midway between the Chindwin and Kyaikthin, the point selected for one of the attacks on the Mandalay-Myitkyina railway. Major Dunlop's column was to cut the line roughly fifteen miles to the north. The deception plan, Intelligence reports disclosed later, was completely successful. The Japanese duly massed troops in the lower Chindwin area, and wasted two weeks combing the countryside for a British Army which, to their utter bewilderment, they could not find.

By the time we started heading for the rendezvous, Jefferies afterwards related, we had exhausted our supplies and were desperately in need of food. We couldn't ask for a supply-dropping, because we hadn't got a wireless set with us. Taking along an extra mule to carry the set, a wireless operator, batteries, and what not would have slowed us down too much. In any case, a supply-drop was really out of the question. It would have brought the Japs down on us, and might have wrecked the whole deception plan.

I decided there was nothing for it but to stalk a village I had picked out on the map. The captured enemy operational orders which the Brigadier had read to us at Imphal, showed that the Japanese were in the habit of sending out whole garrisons to hunt for our men when we sent patrols over the Chindwin. I felt there was a good chance we might find the village unguarded. I took along with me Corporal Hayes and a couple of men armed with hand grenades. Corporal Hayes, a red-haired, freckle-faced young giant, was plagued with an outsize appetite, he'd polish off three days rations between breakfast and supper and still grumble he was hungry.

NB. This was 5182207 Corporal F. Hayes formerly of the Gloucestershire Regiment, who had moved over to 142 Commando from the Bush Warfare School based at Maymyo on the 31st July 1942.

Jefferies continues:

Near the edge of the jungle not far from our target we came upon a small river, and beyond it we spotted through the trees a ridge that looked like a Jap sentry post. We saw smoke rising and could just catch the sound of voices. I posted two of my men in a firing position, crossed the river higher up with Corporal Hayes and started to stalk the sentry post. A ditch full of wet slime led up to the foot of the ridge and we had to go forward very slowly.

I think it must have taken us thirty minutes to advance thirty yards. When we were just under the ridge, I whispered to Hayes, "Get ready to rush them." Holding a grenade in one hand and a rifle in the other we shot out of the ditch with what we hoped were bloodcurdling cries. Sitting around a small fire, placidly eating their supper were five Burmese woodcutters. They gaped at us for a moment, then politely held out a dish of rice.

The woodcutters told us that the village was the headquarters of a Jap garrison of about fifty men, who at the moment were away hunting for us, just as I had hoped. Apparently they hadn't even left behind any pickets. I sent one of the Burmese into the village to buy food, and led my party back across the river in the jungle, just in case the natives had a trick up their sleeve. We were sitting by a clump of bamboo, from which we could watch the path down from the village, when a small dog trotted up and sniffed at our boots.

Just then I heard what sounded like shouted orders in Japanese or Burmese. The voice came from the other side of the river quite close to us. There didn't seem to be any way of escape. We couldn't move a foot through the undergrowth without being heard at that distance. It was one of the nastiest moments I can remember. My heart was beating like the drums of hell. Then we caught sight of the enemy, two Burmese peasants urging a herd of buffalo across the river.

Shortly afterwards, fourteen villagers arrived, carrying on their heads enormous baskets filled with curried fish, curried rice and vegetables, chickens, eggs, and bananas. It was the dinner they had been cooking for the Japanese garrison. I wonder what story they told the Japs when the garrison got back and found the larder had been cleaned out! We collected the rest of the deception group, wolfed what we could on the spot, and loaded what was left on to the mules. After a square meal I was tempted to lay an ambush for the returning Japs, but the Burmese had given us information about a more worth-while target, a village some distance to the east in which the Japanese were working surface oil wells.

We pushed on expecting to reach the village the next night, but ran into a stretch of really hellish jungle. We still didn't want the Japs to find out that we were heading east as they were looking for us to the south, so we kept clear of the beaten tracks, hacking our way through the densely matted undergrowth. In parts the jungle was so thick and steep that we had to build a path for the mules, and sometimes we had to unload them and manhandle their loads. It took us three days to cover fifteen miles.

The food we'd pinched from the enemy ran out excepting for the rice, which unfortunately had been cooked for the Japs and quickly turned sour. We kept going on a few handfuls a day of sour rice. Some of the men chewed on dry jungle roots. We weren't sure whether they were poisonous, but we were in no position to be fussy. Just before dusk on the third day of marching we came upon a small patch of bamboo forest on the top of a hill. We hadn't had a drop of water for nearly thirty-six hours and spent the last hour of daylight frantically slitting open hollow bamboos to see if there was any liquid in them. They were dry as a bone.

That night it seemed incredible that in London, New York or Delhi anyone could just stroll into a bar and drink as much beer as he wanted. I felt as if I'd been thirsty all my life. The hillside dropped steeply into a narrow valley and all the next morning we hunted for a way down for the mules. Eventually we man-handled the mule loads and the animals slid down the hillside on their haunches.

By this time we were desperate for water. An hour before dark we found a stream. The water was beautifully cool and clear; we drank like thirsty camels, then we bathed, watered the mules, and slept until dawn. We were now two and a half days march from the supply-dropping rendezvous, but forty-eight hours behind schedule. By forced marching we covered the distance in a day and a half, and learned from villagers we had only just missed the rest of our force, which had taken a dropping that morning.

We couldn't march another step and bivouacked for the night. The next morning we combed every foot of the dropping zone for any odds and ends that might have been left behind. We found about a dozen packages of dates. The next four days we lived on dates and sour rice, racing to catch up with Emmett's column which was heading for the railway at Kyaikthin. On March 2nd we joined up with them at a point three miles from Kyaikthin station. That same night we were scheduled to blow up the line.

As Jefferies mentions, on the 2nd March Emmett's column had reached the outskirts of the railstation at Kyaikthin, it was already dark and as the column slowly made its way along the rail tracks it was ambushed by a large force of enemy troops. The column was badly caught out and suffered many casualties. Dispersal was called, but confusion reigned as the unit became cut into splintered groups of men, with some sections pushing on to the agreed forward rendezvous, whilst others deciding to turn around and head for home.

Major Jefferies managed to extricate himself and some of his men from the ambush at Kyaikthin, moving off to the east in search of the chosen rendezvous point. Eventually, after some days of hard and hungry marching, they met up with George Dunlop's column close to the banks of the Irrawaddy River. It was now the 9th of March.

Another section from the book 'Wingate's Raiders', by Charles J. Rolo, takes the story of John Jefferies still further:

One evening a patrol brought in some startling news to Major Calvert and 3 Column. Another of Wingate's columns was only three miles to the south. Calvert changed his plans for moving straight ahead that night and veered off southward, and bivouacked close by the other column, which turned out to be Major Dunlop's plus Jefferies' party and what was left of the column that had clashed with the Japanese at Kyaikthin. They had crossed the Irrawaddy at Tagaung, eight miles to the south of Calvert. Next day the officers from both columns met to compare notes.

It was March 16th, the eve of Saint Patrick's Day and Calvert and Jefferies, both Irishmen, were worried as to how they would celebrate the occasion; before his last supply-drop Jefferies had appealed to base for a bottle of Irish whisky, but was told there was none to be had. However, his party was well stocked with bully beef, hard-tack rations, raisins, and rum, and he invited Calvert to dinner. Calvert hit upon the idea of brewing a punch. He emptied the raisins into a mess tin filled with water and put it to boil over a wood fire. Jefferies heated a jar of rum, set fire to it, and mixed the flaming rum with the raisins and water. The concoction was a great success.

After toasts had been drunk to Saint Patrick and to Wingate and to the expedition, Jefferies produced a handful of native cheroots, comprising of bamboo shavings loosely wrapped in green tobacco leaves and listened to Calvert's account of his march from the railway. Then Jefferies told his own story:

I became detached from the rest of my party during the battle of Kyaikthin and crossed the railway with Corporal Hayes. The whole of Southern Force was to rendezvous ten miles west of the Irrawaddy. We could have got there in under forty-eight hours by following the beaten trails, but we didn't want to have the Japs on our heels and struck off through the jungle. We hit an appalling stretch which slowed us down to five or six miles a day and I soon realised it was going to take us three or four days to make the rendezvous.

I warned Corporal Hayes to go easy on his rations; we had less than one day's supply apiece and no water. During our third days march two rather queer things happened. It was very sultry with a stifling hot wind and the tops of the tall bamboos made an eerie noise grinding against each other. After trekking all out from the railway through the driest, deadest-looking jungle I've ever seen, we were done in and may have been a bit light-headed from hunger and thirst.

Anyhow, quite suddenly, above the creaking of the bamboos, I heard a very strange sound. I thought at first that it was an effect of the trees and the wind, but then I caught what sounded like native music on a crude reed pipe. It seemed to be very close. Corporal Hayes heard it too. We never found out what it was. A little farther on in the middle of thick teak jungle we came to a disused timber camp with old broken down shelters. I stopped to take a compass bearing, but I must have been rattled by the music, because I had an uneasy feeling that we were not alone.

I was standing taking my bearing when I heard a rending noise, and Corporal Hayes yelled, "Look out, sir!" I saw the top of an eighty foot teak tree crashing down and jumped clear. It hit the ground exactly where I had been standing. The whole thing struck me as very odd, since the wind was rather light. By now I was quite convinced the place was haunted and we pushed on in a hurry.

The next day we were so starved that at dusk we ventured into a village to buy food. The natives loaded us with chickens, rice, eggs and a jar of rice wine. They have a peculiar superstition that the wine isn't intoxicating when drunk at certain hours of the day. We couldn't wait to find that out. We drank it then and there and it was a good pick-me-up. Next morning we reached the rendezvous and joined up with the rest of the Southern Force.

Some of the men in my party had enjoyed miraculous escapes at Kyaikthin. One Private had the heel of his boot blown off by a mortar, got a bullet through his pack and another through his ammunition pouch, but wasn't scratched himself. We had lost several mules in the battle and one of their leaders, Gurkha Lal Bahadur, known as Red the Fearless, I had always considered as being one of the happiest of my men to be in Burma. When he reported to me I asked him where his mule was. Grinning all over his face he said, "Niche, sahib, niche " (dead sir, dead), as though he had been responsible for killing a dozen Japs. I knew that he had his heart set on joining the fighting platoons and promoted him to the exalted rank of orderly.

A short march brought us to a village where the headman spoke Urdu. He was delighted to see us and gave us tomatoes, bananas, breadfruit and green coconuts. On March 8th we started up the steep Gangan Mountain range overlooking the Irrawaddy and bivouacked on the top the following night. The jungle was so thick I had to climb a tree to see the river. We had no food left except rice and had no water to cook it in, so we gnawed on a few handfuls of uncooked rice and went to sleep dreaming of roast beef and Yorkshire pudding.

It was bitterly cold and the whole lot of us; officers, NCO's and Privates alike, huddled back to back for warmth. The next morning I led a party down to recce the crossing point. I saw two or three trading boats sailing downstream. They weren't really boats, they were more like enormous bamboo rafts, forty yards long by fifteen wide, with huts built on them. We hailed them and bought their cargo of jagri balls and native cheroots. It suddenly struck me that it would be a grand idea to sail down the Irrawaddy to Mandalay on one of these rafts, hiding in the hut during the daytime and stopping at night to blow up the railway where it runs close to the river. Then we'd cruise all the way to Rangoon, pirate a ship, and sail her back to India. But more of that later.

We crossed the Irrawaddy without interference. Some of the Burma Rifles wept when they saw the river. It was their home and they had lived on its banks for years before the war. Half-way through the crossing a Jap reconnaissance plane, the oldest crate I've ever seen in the sky, came flying slowly up the river and showered us with leaflets. It went stuttering up the Irrawaddy and disappeared again into the heat haze.

The leaflets were printed in English, Urdu, Karenni and Burmese, and were addressed to "The pitiable Anglo-Indian Soldiery." They started : "You are a beaten Army, surrender." That amused us no end because we had very different ideas. They told the men they were being led to certain death by bestial British officers and urged them to desert, then march to the nearest village and ask to be led to the Japanese, who would treat them kindly.

Can you imagine any of the British soldiers walking over to the Japs after what they had done to prisoners in 1942. I heard one little Gurkha muttering scornfully, "Private Tojo very dirty liar." However, all of us were really rather grateful for those leaflets as they came in very handy for sanitary purposes. We had scheduled a supply-dropping for March 11th, but were bivouacked on the east bank of the Irrawaddy and some distance short of the rendezvous, when we heard the faint hum of planes approaching from the west.

The RAF men tore down to the sandbanks and lit fires quicker than a bunch of super Boy Scouts. The planes flew past us and we thought they'd failed to spot the fires. We had done some very fancy swearing at the pilots when we suddenly saw them circling back towards the flare-path. The first dozen parachute loads were neatly grouped on the sand-banks. We were so hungry that we started cooking a cheese and biscuit soufflé over the fires while the planes were still dropping the other supplies. It was the first really good meal most of us had eaten since the eve of the battle of Kyaikthin ten days before.

Unfortunately, a wind got up before the third plane had unloaded and the parachutes began to drift into the river. There was nothing for it but to cancel the rest of the dropping. We pushed on due east and eventually found a good site for another supply drop. By this time we were absolutely fed up with biscuits and wirelessed to Peter Lord (Senior Staff Officer at Rear Base): "O' Lord, give us bread."

Back came a message from base saying, "The Lord hath heard thy prayer." The planes flew over next day, March 14th, and, lo and behold, down from the heavens tumbled a sack containing sixty loaves of bread. We also got bully beef, bacon, beans, onions, rice and rum, enough to last us six days. Two more days marching brought us here. And that, Michael, is how you came by this bang-up St Patrick's Eve dinner.

On St Patrick's Day, Calvert and Jefferies started debating the next move. After crossing the Irrawaddy Jefferies had told his party of his plan to sail down the river to Rangoon, a mere five hundred miles through the core of the Japanese occupation.

The men were in great spirits and all agreed it was a splendid idea. For the past three days Jefferies and his officers and N.C.O.'s had talked of nothing else. They had worked out the details very carefully and had even selected on the map points at which they would stop to blow up the railway. They would proceed cautiously, spending three months on the river if necessary. At Rangoon they were determined to pirate a really big ship and sail her back in triumph to Colombo.

Michael Calvert however, put forward another idea, which in reality he too was unable to carry out, after his column had received new orders from Wingate to attack a great strategic objective far to the east, namely the Gokteik Viaduct. More feasible than Jefferies' plan, Calvert argued, would be to blow up a hill section of the trunk motor road between Mandalay and Maymyo, roughly a hundred miles to the south. After some discussion Calvert convinced Jefferies that the odds against his ever reaching Rangoon were higher than the longest shot in the Derby.

Rather regretfully Jefferies dropped his own idea in favour of Calvert's less extravagant suggestion, which involved nothing more dangerous than staging an attack on a key line of communication in the heart of one of the heaviest Jap concentrations in Burma. At least the chances of carrying out a successful demolition of the Mandalay-Maymyo motor road were as good as one in five and the odds against getting back alive not more than ten to one. And so the next move was settled. Meanwhile both Calvert's column and Jefferies' party were in need of a large supply-drop, consisting of boots, clothing, food and new equipment. On March 18th they parted company, each bound on a mission that saner men would have called a suicide venture.

One week later, Wingate called for a conference with his column commanders, arranging on the 23rd March a massive supply dropping for all Northern Group units at a village called Baw, which was located some 5 miles west of the Shweli River. Bernard Fergusson and 5 Column having marched non-stop for over two days, fell just short of the drop zone rendezvous, resulting once again in a scanty share of the available rations.

It was whilst bivouaced south of Baw, that Fergusson was joined by John Jefferies, who had by then parted company, not just with Mike Calvert, but also with Major Dunlop and 1 Column. Jefferies had decided to seek out Wingate and take on fresh orders. He remained with Fergusson for a short time after the Baw supply dropping, before moving on to join Wingate's Brigade HQ and travel on with them.

Major Jefferies managed to extricate himself and some of his men from the ambush at Kyaikthin, moving off to the east in search of the chosen rendezvous point. Eventually, after some days of hard and hungry marching, they met up with George Dunlop's column close to the banks of the Irrawaddy River. It was now the 9th of March.

Another section from the book 'Wingate's Raiders', by Charles J. Rolo, takes the story of John Jefferies still further:

One evening a patrol brought in some startling news to Major Calvert and 3 Column. Another of Wingate's columns was only three miles to the south. Calvert changed his plans for moving straight ahead that night and veered off southward, and bivouacked close by the other column, which turned out to be Major Dunlop's plus Jefferies' party and what was left of the column that had clashed with the Japanese at Kyaikthin. They had crossed the Irrawaddy at Tagaung, eight miles to the south of Calvert. Next day the officers from both columns met to compare notes.

It was March 16th, the eve of Saint Patrick's Day and Calvert and Jefferies, both Irishmen, were worried as to how they would celebrate the occasion; before his last supply-drop Jefferies had appealed to base for a bottle of Irish whisky, but was told there was none to be had. However, his party was well stocked with bully beef, hard-tack rations, raisins, and rum, and he invited Calvert to dinner. Calvert hit upon the idea of brewing a punch. He emptied the raisins into a mess tin filled with water and put it to boil over a wood fire. Jefferies heated a jar of rum, set fire to it, and mixed the flaming rum with the raisins and water. The concoction was a great success.

After toasts had been drunk to Saint Patrick and to Wingate and to the expedition, Jefferies produced a handful of native cheroots, comprising of bamboo shavings loosely wrapped in green tobacco leaves and listened to Calvert's account of his march from the railway. Then Jefferies told his own story:

I became detached from the rest of my party during the battle of Kyaikthin and crossed the railway with Corporal Hayes. The whole of Southern Force was to rendezvous ten miles west of the Irrawaddy. We could have got there in under forty-eight hours by following the beaten trails, but we didn't want to have the Japs on our heels and struck off through the jungle. We hit an appalling stretch which slowed us down to five or six miles a day and I soon realised it was going to take us three or four days to make the rendezvous.

I warned Corporal Hayes to go easy on his rations; we had less than one day's supply apiece and no water. During our third days march two rather queer things happened. It was very sultry with a stifling hot wind and the tops of the tall bamboos made an eerie noise grinding against each other. After trekking all out from the railway through the driest, deadest-looking jungle I've ever seen, we were done in and may have been a bit light-headed from hunger and thirst.

Anyhow, quite suddenly, above the creaking of the bamboos, I heard a very strange sound. I thought at first that it was an effect of the trees and the wind, but then I caught what sounded like native music on a crude reed pipe. It seemed to be very close. Corporal Hayes heard it too. We never found out what it was. A little farther on in the middle of thick teak jungle we came to a disused timber camp with old broken down shelters. I stopped to take a compass bearing, but I must have been rattled by the music, because I had an uneasy feeling that we were not alone.

I was standing taking my bearing when I heard a rending noise, and Corporal Hayes yelled, "Look out, sir!" I saw the top of an eighty foot teak tree crashing down and jumped clear. It hit the ground exactly where I had been standing. The whole thing struck me as very odd, since the wind was rather light. By now I was quite convinced the place was haunted and we pushed on in a hurry.

The next day we were so starved that at dusk we ventured into a village to buy food. The natives loaded us with chickens, rice, eggs and a jar of rice wine. They have a peculiar superstition that the wine isn't intoxicating when drunk at certain hours of the day. We couldn't wait to find that out. We drank it then and there and it was a good pick-me-up. Next morning we reached the rendezvous and joined up with the rest of the Southern Force.

Some of the men in my party had enjoyed miraculous escapes at Kyaikthin. One Private had the heel of his boot blown off by a mortar, got a bullet through his pack and another through his ammunition pouch, but wasn't scratched himself. We had lost several mules in the battle and one of their leaders, Gurkha Lal Bahadur, known as Red the Fearless, I had always considered as being one of the happiest of my men to be in Burma. When he reported to me I asked him where his mule was. Grinning all over his face he said, "Niche, sahib, niche " (dead sir, dead), as though he had been responsible for killing a dozen Japs. I knew that he had his heart set on joining the fighting platoons and promoted him to the exalted rank of orderly.

A short march brought us to a village where the headman spoke Urdu. He was delighted to see us and gave us tomatoes, bananas, breadfruit and green coconuts. On March 8th we started up the steep Gangan Mountain range overlooking the Irrawaddy and bivouacked on the top the following night. The jungle was so thick I had to climb a tree to see the river. We had no food left except rice and had no water to cook it in, so we gnawed on a few handfuls of uncooked rice and went to sleep dreaming of roast beef and Yorkshire pudding.

It was bitterly cold and the whole lot of us; officers, NCO's and Privates alike, huddled back to back for warmth. The next morning I led a party down to recce the crossing point. I saw two or three trading boats sailing downstream. They weren't really boats, they were more like enormous bamboo rafts, forty yards long by fifteen wide, with huts built on them. We hailed them and bought their cargo of jagri balls and native cheroots. It suddenly struck me that it would be a grand idea to sail down the Irrawaddy to Mandalay on one of these rafts, hiding in the hut during the daytime and stopping at night to blow up the railway where it runs close to the river. Then we'd cruise all the way to Rangoon, pirate a ship, and sail her back to India. But more of that later.

We crossed the Irrawaddy without interference. Some of the Burma Rifles wept when they saw the river. It was their home and they had lived on its banks for years before the war. Half-way through the crossing a Jap reconnaissance plane, the oldest crate I've ever seen in the sky, came flying slowly up the river and showered us with leaflets. It went stuttering up the Irrawaddy and disappeared again into the heat haze.

The leaflets were printed in English, Urdu, Karenni and Burmese, and were addressed to "The pitiable Anglo-Indian Soldiery." They started : "You are a beaten Army, surrender." That amused us no end because we had very different ideas. They told the men they were being led to certain death by bestial British officers and urged them to desert, then march to the nearest village and ask to be led to the Japanese, who would treat them kindly.

Can you imagine any of the British soldiers walking over to the Japs after what they had done to prisoners in 1942. I heard one little Gurkha muttering scornfully, "Private Tojo very dirty liar." However, all of us were really rather grateful for those leaflets as they came in very handy for sanitary purposes. We had scheduled a supply-dropping for March 11th, but were bivouacked on the east bank of the Irrawaddy and some distance short of the rendezvous, when we heard the faint hum of planes approaching from the west.

The RAF men tore down to the sandbanks and lit fires quicker than a bunch of super Boy Scouts. The planes flew past us and we thought they'd failed to spot the fires. We had done some very fancy swearing at the pilots when we suddenly saw them circling back towards the flare-path. The first dozen parachute loads were neatly grouped on the sand-banks. We were so hungry that we started cooking a cheese and biscuit soufflé over the fires while the planes were still dropping the other supplies. It was the first really good meal most of us had eaten since the eve of the battle of Kyaikthin ten days before.

Unfortunately, a wind got up before the third plane had unloaded and the parachutes began to drift into the river. There was nothing for it but to cancel the rest of the dropping. We pushed on due east and eventually found a good site for another supply drop. By this time we were absolutely fed up with biscuits and wirelessed to Peter Lord (Senior Staff Officer at Rear Base): "O' Lord, give us bread."

Back came a message from base saying, "The Lord hath heard thy prayer." The planes flew over next day, March 14th, and, lo and behold, down from the heavens tumbled a sack containing sixty loaves of bread. We also got bully beef, bacon, beans, onions, rice and rum, enough to last us six days. Two more days marching brought us here. And that, Michael, is how you came by this bang-up St Patrick's Eve dinner.

On St Patrick's Day, Calvert and Jefferies started debating the next move. After crossing the Irrawaddy Jefferies had told his party of his plan to sail down the river to Rangoon, a mere five hundred miles through the core of the Japanese occupation.

The men were in great spirits and all agreed it was a splendid idea. For the past three days Jefferies and his officers and N.C.O.'s had talked of nothing else. They had worked out the details very carefully and had even selected on the map points at which they would stop to blow up the railway. They would proceed cautiously, spending three months on the river if necessary. At Rangoon they were determined to pirate a really big ship and sail her back in triumph to Colombo.

Michael Calvert however, put forward another idea, which in reality he too was unable to carry out, after his column had received new orders from Wingate to attack a great strategic objective far to the east, namely the Gokteik Viaduct. More feasible than Jefferies' plan, Calvert argued, would be to blow up a hill section of the trunk motor road between Mandalay and Maymyo, roughly a hundred miles to the south. After some discussion Calvert convinced Jefferies that the odds against his ever reaching Rangoon were higher than the longest shot in the Derby.

Rather regretfully Jefferies dropped his own idea in favour of Calvert's less extravagant suggestion, which involved nothing more dangerous than staging an attack on a key line of communication in the heart of one of the heaviest Jap concentrations in Burma. At least the chances of carrying out a successful demolition of the Mandalay-Maymyo motor road were as good as one in five and the odds against getting back alive not more than ten to one. And so the next move was settled. Meanwhile both Calvert's column and Jefferies' party were in need of a large supply-drop, consisting of boots, clothing, food and new equipment. On March 18th they parted company, each bound on a mission that saner men would have called a suicide venture.

One week later, Wingate called for a conference with his column commanders, arranging on the 23rd March a massive supply dropping for all Northern Group units at a village called Baw, which was located some 5 miles west of the Shweli River. Bernard Fergusson and 5 Column having marched non-stop for over two days, fell just short of the drop zone rendezvous, resulting once again in a scanty share of the available rations.

It was whilst bivouaced south of Baw, that Fergusson was joined by John Jefferies, who had by then parted company, not just with Mike Calvert, but also with Major Dunlop and 1 Column. Jefferies had decided to seek out Wingate and take on fresh orders. He remained with Fergusson for a short time after the Baw supply dropping, before moving on to join Wingate's Brigade HQ and travel on with them.

Major Jefferies, along with Wingate's Head Quarters reached the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th March and looked out over the wide expanse of water with trepidation. As Columns 7 and 8 joined them on the shoreline, the commanders discussed the best way forward in getting their men across this most menacing of obstacles. Some boats containing men from 7 Column began to make their way over, when suddenly from the far bank shots were heard as these boats came under attack from a large Japanese patrol. Most of the Chindits in the river were killed or drowned, but some made it over and quickly disappeared into the jungle beyond the western shore.

Wingate and commanders Scott and Gilkes decided that the only option open to them was to withdraw and they melted away into the scrubland from whence they had just come. Gilkes and Scott decided to march away from the location almost immediately, but Wingate opted on finding a well concealed bivouac in the nearby woods at Tokpan Chaung and wait until things had quietened down.

During this time, which went on for about a week, Wingate prepared his group for dispersal. He also decided to relieve his men of all the larger weapons and equipment in order to make their journey back to India as light-weight and speedy as possible. The other decision made was to kill all the remaining mules, butchering them to supplement the depleted rations and to build up the men's strength for the long return trip to India. Being, as always, a man of action, Wingate helped with the silent execution of the long suffering, but ever loyal mules.

We now take up the story using three short extracts from Orde Wingate's own debrief diary for Operation Longcloth:

07/08/43

Lay up all this period on Tokpan Chaung where we ate all our mules.

Moved from lying up on Tokpan with intention of crossing (Irrawaddy) at Kanni or Wegyi. In the late afternoon when in the neighbourhood of Cheikthin we discovered fresh foot prints on the main track leading to the village and deduced that it was probably garrisoned by the Japs. We went into bivouac for the night. The changed plan was to move south the following day towards spot height 1271 SM 8125 from which to observe the river with a view to crossing at Innet.

08/04/43

Moved south towards Myauk Chaung. Very hot and we were short of water. In the late afternoon we found a marsh where we got some water. We held and interrogated two peasants whom we found here. They stated that there were boats at Maunggon and although very tired we decided to push on with the aid of guides. We eventually reached Thabyeyla on the river where we found that the Japs had moved all boats on the east bank up to Tigyaing. We were exhausted by this time and at daybreak went into bivouac east of Maunggon.

09/04/43

In the early afternoon we descended on Maunggon and eventually with local aid found two boats in a backwater. Later we stopped a third boat which was moving upstream. We began crossing about 1530 hours, but when half the party was over automatic fire was heard from the north and our native boatmen made off with the boats leaving half our party still on the east bank. The group then consisted of Brigadier, Brigade Major, Jefferies, Aung Thin and Motlal Katju with 24 other ranks. We had apparently landed on an island and we immediately pushed on towards Nyaungbintha where we got a large boat and crossed the rest of the river at dusk.

To read more of Wingate's dispersal diary, please click on the following link: Wingate's Journey Home

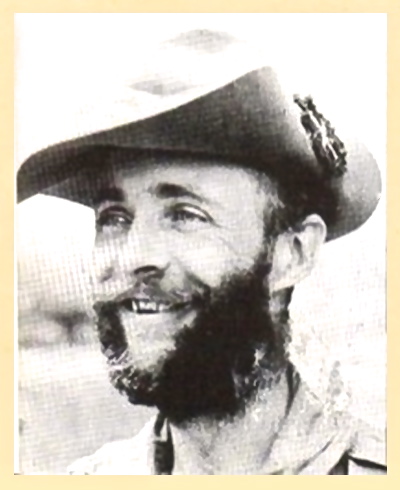

Seen below is a rather special photograph of Brigadier Wingate and some of the men from his dispersal group in April 1943. It cannot be confirmed, but this image in my view was probably taken whilst the group were held up in the scrub jungle near the Tokpan Chaung.

Wingate and commanders Scott and Gilkes decided that the only option open to them was to withdraw and they melted away into the scrubland from whence they had just come. Gilkes and Scott decided to march away from the location almost immediately, but Wingate opted on finding a well concealed bivouac in the nearby woods at Tokpan Chaung and wait until things had quietened down.

During this time, which went on for about a week, Wingate prepared his group for dispersal. He also decided to relieve his men of all the larger weapons and equipment in order to make their journey back to India as light-weight and speedy as possible. The other decision made was to kill all the remaining mules, butchering them to supplement the depleted rations and to build up the men's strength for the long return trip to India. Being, as always, a man of action, Wingate helped with the silent execution of the long suffering, but ever loyal mules.

We now take up the story using three short extracts from Orde Wingate's own debrief diary for Operation Longcloth:

07/08/43

Lay up all this period on Tokpan Chaung where we ate all our mules.

Moved from lying up on Tokpan with intention of crossing (Irrawaddy) at Kanni or Wegyi. In the late afternoon when in the neighbourhood of Cheikthin we discovered fresh foot prints on the main track leading to the village and deduced that it was probably garrisoned by the Japs. We went into bivouac for the night. The changed plan was to move south the following day towards spot height 1271 SM 8125 from which to observe the river with a view to crossing at Innet.

08/04/43

Moved south towards Myauk Chaung. Very hot and we were short of water. In the late afternoon we found a marsh where we got some water. We held and interrogated two peasants whom we found here. They stated that there were boats at Maunggon and although very tired we decided to push on with the aid of guides. We eventually reached Thabyeyla on the river where we found that the Japs had moved all boats on the east bank up to Tigyaing. We were exhausted by this time and at daybreak went into bivouac east of Maunggon.

09/04/43

In the early afternoon we descended on Maunggon and eventually with local aid found two boats in a backwater. Later we stopped a third boat which was moving upstream. We began crossing about 1530 hours, but when half the party was over automatic fire was heard from the north and our native boatmen made off with the boats leaving half our party still on the east bank. The group then consisted of Brigadier, Brigade Major, Jefferies, Aung Thin and Motlal Katju with 24 other ranks. We had apparently landed on an island and we immediately pushed on towards Nyaungbintha where we got a large boat and crossed the rest of the river at dusk.

To read more of Wingate's dispersal diary, please click on the following link: Wingate's Journey Home

Seen below is a rather special photograph of Brigadier Wingate and some of the men from his dispersal group in April 1943. It cannot be confirmed, but this image in my view was probably taken whilst the group were held up in the scrub jungle near the Tokpan Chaung.

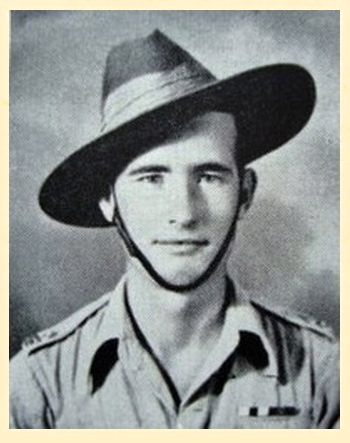

Arthur Willshaw, India 1942.

Arthur Willshaw, India 1942.

The next two weeks of arduous marching on generally empty stomachs, took a great toll on the members of Wingate's dispersal party. As the mental and physical strength of the men began to falter, an almost miraculous incident occurred that was to change the fortunes and ultimate destiny of the group. Contained within the book 'Wingate's Lost Brigade', by Phil Chinnery, is a short account from the memoirs of RAF Wireless Operator Sgt. Arthur Willshaw, which describes the last few days journey before the men regained the Chindwin River:

Arthur Willshaw recalled:

After crossing the Mu River we faced the last sixty miles over almost impossible country to the Chindwin. It was here that we met an old Burmese Buddhist hermit, who appeared one evening just out of nowhere. He explained via the interpreters, that he had been sent to lead to safety a party of white strangers who were coming into his area. He was asked who had sent him and his only answer was that his God had warned him.

It was a risk we had to take, especially as we knew from information from friendly villagers that the Japs, now wise to our escape plan, were watching every road and track from the Mu to the Chindwin. Day after day he led us along animal trails and elephant tracks, sometimes wading for a day at a time through waist-high mountain streams. At one point on a very high peak we saw, way in the distance, a thin blue ribbon, it was the Chindwin. What added spirit this gave our flagging bodies and spent energies!

All our supplies were gone and we were really living on what we could find. A kind of lethargy was slowly taking its toll on us, we just couldn't care less one way or the other. The old hermit took us to within a few miles of the Chindwin and disappeared as strangely as he had appeared. It was then around the 23rd April.

A villager we stopped on the track told us that the Japanese were everywhere and that it would be impossible to get boats to cross the river as they had it so well guarded. Wingate selected five swimmers who would, with himself, attempt to get to the Chindwin, swim it and send back boats to an agreed rendezvous with the others. These swimmers were Brigadier Wingate, Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles, Captain Jefferies, Sergeant Carey of the Commandos, Private Boardman of the 13th King's, and myself.

At 0400 hours on the morning of 29th April 1943 the six of us set out for the river. Soon we struck a terrible stretch of elephant grass, seven or eight feet high and with an edge like a razor. We reconnoitred along it but could see no end to it, and no track through it, so the decision was made to push through it. Each man in turn dived headlong into it while the others pushed him flat; after a few minutes another took his place at the front. In four hours we had covered about 300 yards and were making such a noise that we feared the Japanese would be waiting when we broke out of the other side.

We pushed our way into a small clearing and collapsed; I couldn't have gone another foot and I know that we all had the same sickening thought. After all we had been through, how could we find the strength to go on? Then Wingate crawled to a gap in the grass and disappeared, only to reappear within minutes beckoning us to join him. We pushed our way another few feet and there it was, the Chindwin, right under our noses.

Arms and legs streaming with blood, we decided to chance the Japs and swim for it right away. Among the many things I asked for on my pre-operational stocking-up visit to Karachi was a number of 'Mae West' lifejackets. I had carried mine throughout the whole of the expedition; I wore it as a waistcoat, used it as a pillow, used it to ford rivers and streams, and I still have it today. It was to save my life and that of Aung Thin that day.

Blowing it up, I explained that I would swim last and that if anybody got into difficulties they could hang on to me and we would drift downstream if necessary. How I feared that crossing, even though the Mae West was filthy and muddy from our time in Burma, it would soon wash clean in the water and what a bright orange coloured target it would make for the waiting Japs! And so into the water; ten yards made, twenty yards, fifty, one hundred, now almost just drifting, thoroughly exhausted. Aung Thin with a last despairing effort made it to my side and together we struggled the remaining fifty yards to the other bank. We dragged ourselves up the bank and into cover, I still relive those fifteen minutes waiting for the burst of machine-gun fire that thankfully didn't come.

In his book Phil Chinnery also remarked:

Major John Jefferies almost did not make it. After swimming about 40 yards he had to let go of his boots and rifle and at about 100 yards from the bank the tattered shreds of his shirt sleeves wound themselves tightly around his arms completely imprisoning them. He kicked out desperately with his legs and forged towards the bank. He began to swallow mouthfuls of water and his kicks grew feebler. He felt an enormous weariness and began to lose consciousness. Then his feet touched bottom and he dragged himself through the shallows and collapsed on the beach.

Wingate was waiting for them. He had strapped his Wolseley helmet to his chest, where the thick canvas made an airtight and waterproof float and did much to support him during his swim. The hat would remain with him until his death. The exhausted men struggled on for five more miles to the nearest British outpost, where a group of British officers were sitting on ration tins drinking tea. They were given hot sweet tea with condensed milk, bully-beef stew, rum and cigarettes.

The men were taken up to Tamu on the Assam/Burma border and eventually moved on to Imphal where they were treated for their various ailments and conditions by Matron Agnes McGeary at Casualty Clearing Station No. 19.

Arthur Willshaw recalled:

After crossing the Mu River we faced the last sixty miles over almost impossible country to the Chindwin. It was here that we met an old Burmese Buddhist hermit, who appeared one evening just out of nowhere. He explained via the interpreters, that he had been sent to lead to safety a party of white strangers who were coming into his area. He was asked who had sent him and his only answer was that his God had warned him.

It was a risk we had to take, especially as we knew from information from friendly villagers that the Japs, now wise to our escape plan, were watching every road and track from the Mu to the Chindwin. Day after day he led us along animal trails and elephant tracks, sometimes wading for a day at a time through waist-high mountain streams. At one point on a very high peak we saw, way in the distance, a thin blue ribbon, it was the Chindwin. What added spirit this gave our flagging bodies and spent energies!

All our supplies were gone and we were really living on what we could find. A kind of lethargy was slowly taking its toll on us, we just couldn't care less one way or the other. The old hermit took us to within a few miles of the Chindwin and disappeared as strangely as he had appeared. It was then around the 23rd April.

A villager we stopped on the track told us that the Japanese were everywhere and that it would be impossible to get boats to cross the river as they had it so well guarded. Wingate selected five swimmers who would, with himself, attempt to get to the Chindwin, swim it and send back boats to an agreed rendezvous with the others. These swimmers were Brigadier Wingate, Captain Aung Thin of the Burma Rifles, Captain Jefferies, Sergeant Carey of the Commandos, Private Boardman of the 13th King's, and myself.

At 0400 hours on the morning of 29th April 1943 the six of us set out for the river. Soon we struck a terrible stretch of elephant grass, seven or eight feet high and with an edge like a razor. We reconnoitred along it but could see no end to it, and no track through it, so the decision was made to push through it. Each man in turn dived headlong into it while the others pushed him flat; after a few minutes another took his place at the front. In four hours we had covered about 300 yards and were making such a noise that we feared the Japanese would be waiting when we broke out of the other side.

We pushed our way into a small clearing and collapsed; I couldn't have gone another foot and I know that we all had the same sickening thought. After all we had been through, how could we find the strength to go on? Then Wingate crawled to a gap in the grass and disappeared, only to reappear within minutes beckoning us to join him. We pushed our way another few feet and there it was, the Chindwin, right under our noses.

Arms and legs streaming with blood, we decided to chance the Japs and swim for it right away. Among the many things I asked for on my pre-operational stocking-up visit to Karachi was a number of 'Mae West' lifejackets. I had carried mine throughout the whole of the expedition; I wore it as a waistcoat, used it as a pillow, used it to ford rivers and streams, and I still have it today. It was to save my life and that of Aung Thin that day.

Blowing it up, I explained that I would swim last and that if anybody got into difficulties they could hang on to me and we would drift downstream if necessary. How I feared that crossing, even though the Mae West was filthy and muddy from our time in Burma, it would soon wash clean in the water and what a bright orange coloured target it would make for the waiting Japs! And so into the water; ten yards made, twenty yards, fifty, one hundred, now almost just drifting, thoroughly exhausted. Aung Thin with a last despairing effort made it to my side and together we struggled the remaining fifty yards to the other bank. We dragged ourselves up the bank and into cover, I still relive those fifteen minutes waiting for the burst of machine-gun fire that thankfully didn't come.

In his book Phil Chinnery also remarked:

Major John Jefferies almost did not make it. After swimming about 40 yards he had to let go of his boots and rifle and at about 100 yards from the bank the tattered shreds of his shirt sleeves wound themselves tightly around his arms completely imprisoning them. He kicked out desperately with his legs and forged towards the bank. He began to swallow mouthfuls of water and his kicks grew feebler. He felt an enormous weariness and began to lose consciousness. Then his feet touched bottom and he dragged himself through the shallows and collapsed on the beach.

Wingate was waiting for them. He had strapped his Wolseley helmet to his chest, where the thick canvas made an airtight and waterproof float and did much to support him during his swim. The hat would remain with him until his death. The exhausted men struggled on for five more miles to the nearest British outpost, where a group of British officers were sitting on ration tins drinking tea. They were given hot sweet tea with condensed milk, bully-beef stew, rum and cigarettes.

The men were taken up to Tamu on the Assam/Burma border and eventually moved on to Imphal where they were treated for their various ailments and conditions by Matron Agnes McGeary at Casualty Clearing Station No. 19.

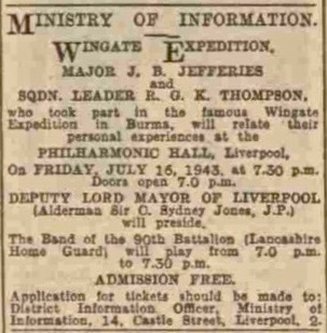

Liverpool Evening Express, 9th July 1943.

Liverpool Evening Express, 9th July 1943.

After a short period of rest and recuperation, John Jefferies was selected, along with RAF Liaison Officer, Squadron Leader Robert Thompson, to perform propaganda and publicity debriefs on behalf on Brigadier Wingate. This included in late June 1943, being flown back to the United Kingdom and giving witness to their experiences on Operation Longcloth to the Ministry of Defence and Army Command, as well as open seminars across the country.