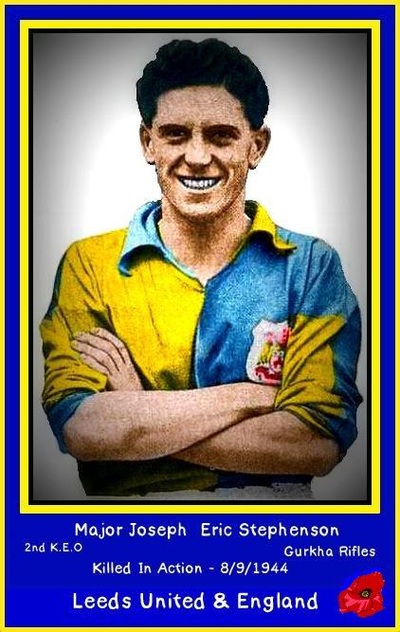

Major Joseph Eric Stephenson

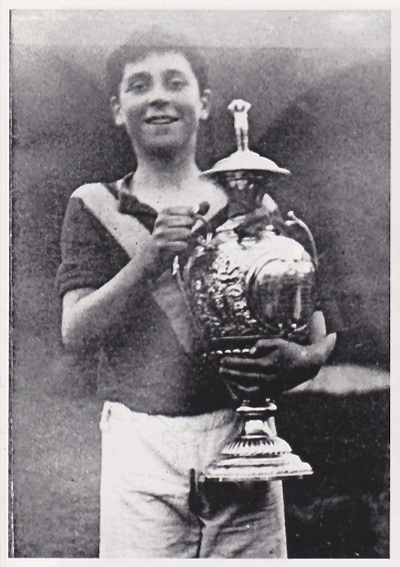

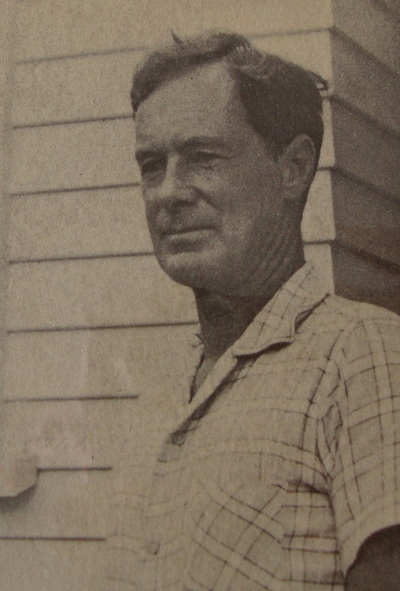

Eric Stephenson in 1938.

Eric Stephenson in 1938.

In January 2014 I was extremely fortunate to be contacted by the eldest daughter of Major Eric Stephenson. Jan had recently visited the Gurkha Museum at Winchester searching for more information about her father as she closed in on completing her book about his time as a professional footballer and his WW2 service. The curator at the museum mentioned my website and this is how she made contact and our conversation began.

From our first exchange of emails:

Dear Jan,

Thank you for your email contact via my website. It was good of Gavin to tell you about my website in honour of the men from Operation Longcloth. I hope you have enjoyed reading some of the pages.

Obviously, I am very much aware of your father and his contribution to the operation in 1943 and it is wonderful to be in touch with you now. I would be very happy to receive anything you are willing to share about him and his time in Burma. I have found the odd piece of information about his life before WW2 on line, his football career and so on.

When I was up at the Gurkha Museum I was able to copy some of the short diaries written by him in regard to Chindit Column 2 in 1943 and his involvement that year, it was a shame that these only amounted to some 5/6 pages. The story of Column 2, as you must know, has been shrouded in mystery and indeed controversy to this day.

I had previously been in contact with another member of the extended Stephenson family in the summer of 2011. Robin Lee and I had bumped into each other on line via the website forum WW2Talk. Once again we exchanged information about Eric Stephenson and eventually met up at the National Archives where we discussed Eric’s time as a footballer and his Army service.

Jan Rippin’s book, ‘The Happy Warrior’ was published in April 2014 and is a wonderful tribute to her father. It captures and portrays his true spirit as a loyal and loving family man and a compassionate and caring Army Officer. The book forms the basis of my own short presentation of the life of Major Eric Stephenson.

For me, Jan’s personal story is so much like that of my own mother. Both ladies were less than 5 years old when their Dad’s left Britain for India. Both had to look on, perhaps without true understanding, as those terrible telegrams tore apart their previously straightforward and safe family lives.

Early life, family and football

Eric was born on the 4th of September 1914, the son of Joseph and Fanny Stephenson. His father was an engineer, but had come from a long line of seafarers and butchers. Eric grew up in Leytonstone in the suburbs of east London; he was one of seven children living in the family home at 25 Leybourne Road.

Even at an early age Eric adored playing football, supporting his beloved West Ham and spending hour upon hour playing with his friends and siblings on Wanstead Flats, a large expanse of playing fields near his home, which also included a large lake and woodland. Eric was described as a lively, active and sociable little boy, with an engaging smile and always ready to entertain and amuse people. The family also recalled his helpful nature and maturity beyond his tender years. He brightened any place he frequented, but it was his love of all sports, especially football that defined his early life.

The pinnacle of Eric’s schoolboy football was to be chosen to represent London in April 1930 and play against Glasgow Schoolboys at Hampden Park. Eric left school at 15 having achieved both sporting and academic success. He was also a passionate member of the local Methodist Church at this time and his Christian faith would be a consistent influence throughout his life.

In May 1930 Eric’s young life must have been somewhat affected by the families sudden move to Oakwood, a suburb of the Yorkshire city of Leeds. His father had been offered a very good job in the area and eventually, after another short hop to Roundhay, the family settled down into their new home in Talbot Road. Eric soon adjusted to his new life in Yorkshire and joined the local amateur football club, Oakwood Old Boys. His obvious footballing talent was soon spotted and he was invited to join the ground staff at Leeds United FC.

Although his love for the game of football was strong, Eric had never really considered the sport as a career choice. However, at that time Joseph, his father, was not in work and the family were struggling to make ends meet. Eric must have decided that it was more important to help out his family during these difficult times, rather than follow any personal plans he may have had in regard to other employment opportunities. On his seventeenth birthday Eric Stephenson signed professional papers and joined Leeds United as a full-time player, earning the not inconsiderable sum for those times of £12 per week. True to his selfless and devoted nature, he handed over his wages to the family in support and upkeep of the household.

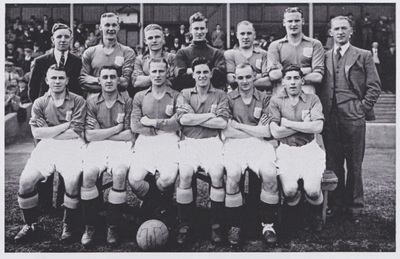

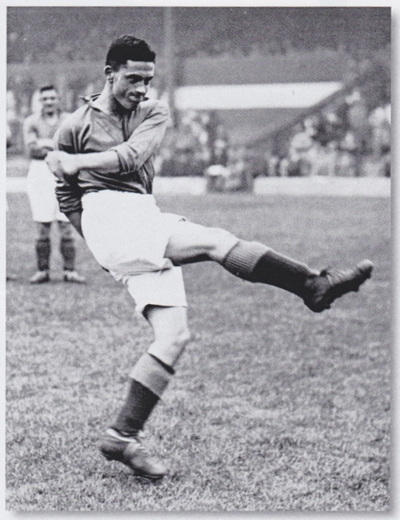

As a player Eric displayed an instinctive understanding for the game of football and enjoyed an excellent relationship with his team mates and was extremely popular with the supporters of the club. He managed to maintain his principles of fairness and good sportsmanship throughout his career, never putting too much emphasis of winning. Eric made his professional debut in March 1934 in a home match against Portsmouth FC. Leeds won the game by three goals to one and Eric Stephenson was lauded as “a great find at inside left.” His play was exciting and full of artistry and vision for one so young and this impressed many of the local sports writers of the time.

One journalist described Eric as: “an inexperienced lad with only a few games behind him, but a born footballer with quick control, astonishingly shrewd in distribution, pushing a ball through a yard gap as accurately as the long cross-field pass, with a forceful finish and an intelligent outlook.”

His successful early career at Leeds brought Eric to the attention of the National team. He attended trials for England in October 1937, making his full international debut at the age of 23 against Scotland. Although England lost the match, described by journalists as exceedingly dull, Eric had stood out as the one bright element to the day’s events. England beat Ireland 7-0 at Old Trafford in his second game, but sadly after taking part in a tour of Europe in May 1939, war was to put an end to his international career.

As we know Eric loved all sports, but he was particularly fond of tennis and played this game to quite a high standard. It was while attending a tennis tournament that Eric first met his bride to be, Olive Cook. Both Eric and Olive were members of the local Methodist Church and enjoyed the wide and varied social scene surrounding the church and it’s other members. Eric involved himself in many activities; he took advantage of the nearby Yorkshire countryside and was often out taking long walks on the moors or rock climbing in the Dales. He became a Lieutenant in the local Boys Brigade and especially devoted his time to those from deprived backgrounds, always looking to help these youngsters improve their lot in life.

Eric and Olive married on the 28th May 1938 at Lidgett Park Methodist Church in Leeds. They set up home close to both sets of parents in a new red-bricked house on the outskirts of Roundhay. It was whilst living at this house that both their daughters, Janet and Rosalind were born, with Olive running the house and Eric playing for Leeds United.

Seen below are some images in relation to this story and Eric's early life and football career. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

From our first exchange of emails:

Dear Jan,

Thank you for your email contact via my website. It was good of Gavin to tell you about my website in honour of the men from Operation Longcloth. I hope you have enjoyed reading some of the pages.

Obviously, I am very much aware of your father and his contribution to the operation in 1943 and it is wonderful to be in touch with you now. I would be very happy to receive anything you are willing to share about him and his time in Burma. I have found the odd piece of information about his life before WW2 on line, his football career and so on.

When I was up at the Gurkha Museum I was able to copy some of the short diaries written by him in regard to Chindit Column 2 in 1943 and his involvement that year, it was a shame that these only amounted to some 5/6 pages. The story of Column 2, as you must know, has been shrouded in mystery and indeed controversy to this day.

I had previously been in contact with another member of the extended Stephenson family in the summer of 2011. Robin Lee and I had bumped into each other on line via the website forum WW2Talk. Once again we exchanged information about Eric Stephenson and eventually met up at the National Archives where we discussed Eric’s time as a footballer and his Army service.

Jan Rippin’s book, ‘The Happy Warrior’ was published in April 2014 and is a wonderful tribute to her father. It captures and portrays his true spirit as a loyal and loving family man and a compassionate and caring Army Officer. The book forms the basis of my own short presentation of the life of Major Eric Stephenson.

For me, Jan’s personal story is so much like that of my own mother. Both ladies were less than 5 years old when their Dad’s left Britain for India. Both had to look on, perhaps without true understanding, as those terrible telegrams tore apart their previously straightforward and safe family lives.

Early life, family and football

Eric was born on the 4th of September 1914, the son of Joseph and Fanny Stephenson. His father was an engineer, but had come from a long line of seafarers and butchers. Eric grew up in Leytonstone in the suburbs of east London; he was one of seven children living in the family home at 25 Leybourne Road.

Even at an early age Eric adored playing football, supporting his beloved West Ham and spending hour upon hour playing with his friends and siblings on Wanstead Flats, a large expanse of playing fields near his home, which also included a large lake and woodland. Eric was described as a lively, active and sociable little boy, with an engaging smile and always ready to entertain and amuse people. The family also recalled his helpful nature and maturity beyond his tender years. He brightened any place he frequented, but it was his love of all sports, especially football that defined his early life.

The pinnacle of Eric’s schoolboy football was to be chosen to represent London in April 1930 and play against Glasgow Schoolboys at Hampden Park. Eric left school at 15 having achieved both sporting and academic success. He was also a passionate member of the local Methodist Church at this time and his Christian faith would be a consistent influence throughout his life.

In May 1930 Eric’s young life must have been somewhat affected by the families sudden move to Oakwood, a suburb of the Yorkshire city of Leeds. His father had been offered a very good job in the area and eventually, after another short hop to Roundhay, the family settled down into their new home in Talbot Road. Eric soon adjusted to his new life in Yorkshire and joined the local amateur football club, Oakwood Old Boys. His obvious footballing talent was soon spotted and he was invited to join the ground staff at Leeds United FC.

Although his love for the game of football was strong, Eric had never really considered the sport as a career choice. However, at that time Joseph, his father, was not in work and the family were struggling to make ends meet. Eric must have decided that it was more important to help out his family during these difficult times, rather than follow any personal plans he may have had in regard to other employment opportunities. On his seventeenth birthday Eric Stephenson signed professional papers and joined Leeds United as a full-time player, earning the not inconsiderable sum for those times of £12 per week. True to his selfless and devoted nature, he handed over his wages to the family in support and upkeep of the household.

As a player Eric displayed an instinctive understanding for the game of football and enjoyed an excellent relationship with his team mates and was extremely popular with the supporters of the club. He managed to maintain his principles of fairness and good sportsmanship throughout his career, never putting too much emphasis of winning. Eric made his professional debut in March 1934 in a home match against Portsmouth FC. Leeds won the game by three goals to one and Eric Stephenson was lauded as “a great find at inside left.” His play was exciting and full of artistry and vision for one so young and this impressed many of the local sports writers of the time.

One journalist described Eric as: “an inexperienced lad with only a few games behind him, but a born footballer with quick control, astonishingly shrewd in distribution, pushing a ball through a yard gap as accurately as the long cross-field pass, with a forceful finish and an intelligent outlook.”

His successful early career at Leeds brought Eric to the attention of the National team. He attended trials for England in October 1937, making his full international debut at the age of 23 against Scotland. Although England lost the match, described by journalists as exceedingly dull, Eric had stood out as the one bright element to the day’s events. England beat Ireland 7-0 at Old Trafford in his second game, but sadly after taking part in a tour of Europe in May 1939, war was to put an end to his international career.

As we know Eric loved all sports, but he was particularly fond of tennis and played this game to quite a high standard. It was while attending a tennis tournament that Eric first met his bride to be, Olive Cook. Both Eric and Olive were members of the local Methodist Church and enjoyed the wide and varied social scene surrounding the church and it’s other members. Eric involved himself in many activities; he took advantage of the nearby Yorkshire countryside and was often out taking long walks on the moors or rock climbing in the Dales. He became a Lieutenant in the local Boys Brigade and especially devoted his time to those from deprived backgrounds, always looking to help these youngsters improve their lot in life.

Eric and Olive married on the 28th May 1938 at Lidgett Park Methodist Church in Leeds. They set up home close to both sets of parents in a new red-bricked house on the outskirts of Roundhay. It was whilst living at this house that both their daughters, Janet and Rosalind were born, with Olive running the house and Eric playing for Leeds United.

Seen below are some images in relation to this story and Eric's early life and football career. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

War

The new domestic football season of September 1939 was very short lived. Leeds United decided to abandon their commitment to the league after only three matches, as players and other staff began to enlist into the Armed Services.

Eric’s good friend, Stan Maney, described the feelings at that time:

“Eric, Gordon and I were all married shortly before the second world war. Eric and Gordon went in to the Army and I joined the RAF. We had all been of a pacifist persuasion, but the Nazi atrocities so sickened us, that we felt there was no alternative but to resist.“

Eric Stephenson enlisted at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester on the 13th of October 1939. He joined the Royal Artillery Unit of the Territorial Army as Acting Sergeant attached to the 69th Infantry Brigade and was stationed at Beverley in Yorkshire. He soon moved on to the Army Physical Training Corps at Aldershot, where his obvious skills and attributes as a sportsman held him in good stead and high esteem.

Eric soon became frustrated with his post at Aldershot, feeling that, although his role as a PT Instructor was valid, it did not stretch his own capabilities enough or allow him the opportunity to make a difference at the sharp end of the fighting. In November 1941 he took up a transfer to the Officer Cadets Training Corps at Sandhurst and his Army life soon became very different indeed. He spent five months at Sandhurst, excelling at most elements of officer training, before passing out with credit on the 3rd April 1942. He was commissioned into the Indian Army as a Lieutenant and almost immediately received an overseas posting.

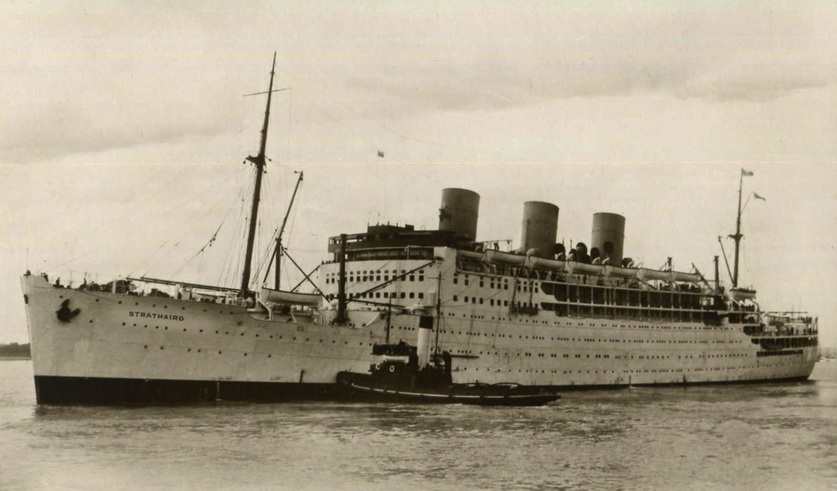

Eric left British shores aboard the troopship ‘Strathaird’ part of the convoy WS (Winston’s Specials) 19, taking the long route out to India with the usual stop-overs at Freetown in Sierre Leone for supplies and then on to Durban in South Africa, where the men disembarked for a shore leave of around nine days. Eric stayed at the Greyville Racecourse, which was a large tented camp set up to accommodate the visiting British troops as they journeyed through to the sub-continent. By mid-June the men had continued their voyage, reaching Bombay via Mombasa on the 1st July 1942.

For more information about convoy WS19 and Eric's journey to India, please click on the following link: http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/ws/index.html

The new domestic football season of September 1939 was very short lived. Leeds United decided to abandon their commitment to the league after only three matches, as players and other staff began to enlist into the Armed Services.

Eric’s good friend, Stan Maney, described the feelings at that time:

“Eric, Gordon and I were all married shortly before the second world war. Eric and Gordon went in to the Army and I joined the RAF. We had all been of a pacifist persuasion, but the Nazi atrocities so sickened us, that we felt there was no alternative but to resist.“

Eric Stephenson enlisted at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester on the 13th of October 1939. He joined the Royal Artillery Unit of the Territorial Army as Acting Sergeant attached to the 69th Infantry Brigade and was stationed at Beverley in Yorkshire. He soon moved on to the Army Physical Training Corps at Aldershot, where his obvious skills and attributes as a sportsman held him in good stead and high esteem.

Eric soon became frustrated with his post at Aldershot, feeling that, although his role as a PT Instructor was valid, it did not stretch his own capabilities enough or allow him the opportunity to make a difference at the sharp end of the fighting. In November 1941 he took up a transfer to the Officer Cadets Training Corps at Sandhurst and his Army life soon became very different indeed. He spent five months at Sandhurst, excelling at most elements of officer training, before passing out with credit on the 3rd April 1942. He was commissioned into the Indian Army as a Lieutenant and almost immediately received an overseas posting.

Eric left British shores aboard the troopship ‘Strathaird’ part of the convoy WS (Winston’s Specials) 19, taking the long route out to India with the usual stop-overs at Freetown in Sierre Leone for supplies and then on to Durban in South Africa, where the men disembarked for a shore leave of around nine days. Eric stayed at the Greyville Racecourse, which was a large tented camp set up to accommodate the visiting British troops as they journeyed through to the sub-continent. By mid-June the men had continued their voyage, reaching Bombay via Mombasa on the 1st July 1942.

For more information about convoy WS19 and Eric's journey to India, please click on the following link: http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/ws/index.html

Once on Indian soil Eric was posted to the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles and was sent by train to join the battalion at their Chindit training camp at Saugor. Like many officers before him he had taken the trouble to learn Urdu on the voyage out to India, this would prove useful when communicating with some of the Gurkha NCO’s, but did not really help when talking with the ordinary Gurkha Rifleman.

Eric enjoyed the challenge of working with the new Gurkha recruits and was comfortably at home with Wingate’s Chindit ideology. In his letters home during this period he constantly refers to his new environment, describing the flora and fauna to his eldest daughter and encouraging her to look up the animals he mentioned in his letters in her books back home.

Wingate’s philosophy, based on a strong physical mind and body suited Eric’s own personality perfectly. He also admired Wingate’s emphasis on complete trust between all ranks within the Chindit unit and that all men must be aware of their role and the task at hand. This sense of equality within the group sat well with Eric and complemented his own style of man management.

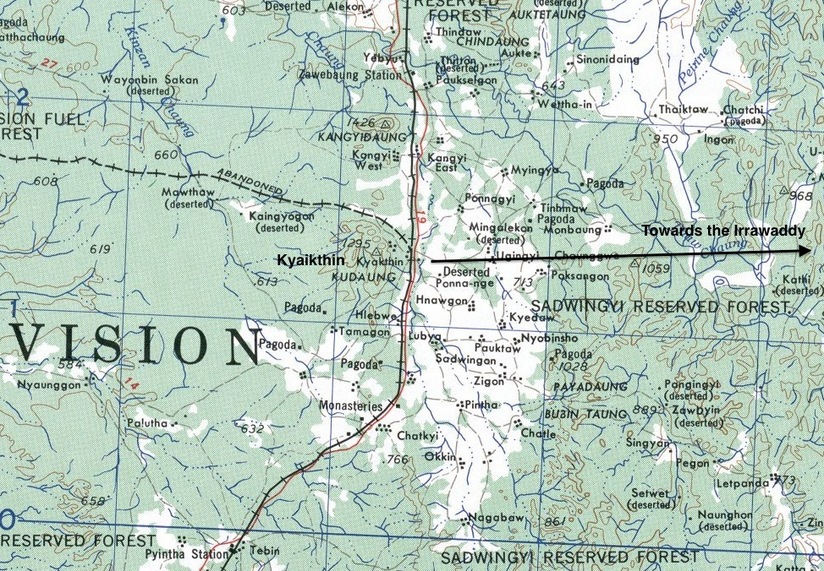

Eric was placed into Chindit Column 2, this unit was commanded by Major Arthur Emmett, a tea planter from Ceylon. Column 2 formed part of Southern Group in 1943, its main role was to create a diversion for Wingate, as he and Northern Group (Cols. 3,4,5,7 and 8) moved forward to sabotage the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. Southern Group’s role as decoy would inevitably mean a confrontation with the Japanese and this duly came at the railway town of Kyaikthin on the 2nd March 1943. Column 2 had been marching all day and were making up for lost time by moving along the railway lines towards Kyaikthin, before looking to make camp for the night.

As darkness fell the column was suddenly ambushed by a large group of Japanese and all hell broke loose. Ian Machorton, another young officer from Column 2 described this moment in his book, ‘Safer than a Known Way’.

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel".

Eric Stephenson was responsible for writing the official War diary for Column 2 in 1943. This is how he recorded the events of the 2nd March:

“At 22.00 hours according to orders from the Officer commanding No. 1 Group (Southern Section), No. 2 Column formed up on the small branch railway line and prepared to advance on Kyaikthin. No sooner had the column commenced its advance, than enemy machine guns opened fire. It was obvious that the column had walked into a strong and cleverly laid ambush and the valuable weapon of surprise had been snatched from us.

A vigorous encounter began. Major Emmett ordered an immediate counter attack, but this was beaten off by the enemy, and then attempts were made by both sides to out-flank and infiltrate. Either by good fortune or knowledge gained, the enemy mortar fire began to fall among the animals. These were already badly frightened and this caused terrific pandemonium, of which the enemy took full advantage by gaining ground and infiltrating.

After the engagement had gone on for two hours, the second dispersal call was sounded and the Column began to move away in groups. Jemadar Manbahadur Gurung, commanding the platoon detailed to cover dispersal put up a wonderful show, remaining in position to inflict a considerable number of casualties on the enemy. The column did not succeed in re-forming after this engagement, but the majority regained the Chindwin in several separate parties.”

As Eric has described, most of Column 2 turned and headed back to India after the disaster at Kyaikthin. This was not the agreed plan however and Major Emmett was to receive heavy criticism from Brigadier Wingate for his leadership of Column 2 after the operation was over.

After re-grouping some of the men from Column 2 did push on to the formerly agreed rendezvous location close to the western banks of the Irrawaddy River. Lieutenant Eric Stephenson was amongst these men, leading his small group of Gurkha Riflemen away from their terrifying ordeal at Kyaikthin and hoping to meet up with the rest of Southern Group.

Eric did meet up with the Burma Rifle platoon of Column 2 and came under the command of the senior officer of this group, Captain George Power Carne. The two groups then patrolled the local area for a further 5 weeks, providing useful reconnaissance for the other Chindit columns still operating further north. Eventually the decision was made to disperse and Lieutenant Stephenson and his Gurkhas returned to India.

Eric enjoyed the challenge of working with the new Gurkha recruits and was comfortably at home with Wingate’s Chindit ideology. In his letters home during this period he constantly refers to his new environment, describing the flora and fauna to his eldest daughter and encouraging her to look up the animals he mentioned in his letters in her books back home.

Wingate’s philosophy, based on a strong physical mind and body suited Eric’s own personality perfectly. He also admired Wingate’s emphasis on complete trust between all ranks within the Chindit unit and that all men must be aware of their role and the task at hand. This sense of equality within the group sat well with Eric and complemented his own style of man management.

Eric was placed into Chindit Column 2, this unit was commanded by Major Arthur Emmett, a tea planter from Ceylon. Column 2 formed part of Southern Group in 1943, its main role was to create a diversion for Wingate, as he and Northern Group (Cols. 3,4,5,7 and 8) moved forward to sabotage the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway. Southern Group’s role as decoy would inevitably mean a confrontation with the Japanese and this duly came at the railway town of Kyaikthin on the 2nd March 1943. Column 2 had been marching all day and were making up for lost time by moving along the railway lines towards Kyaikthin, before looking to make camp for the night.

As darkness fell the column was suddenly ambushed by a large group of Japanese and all hell broke loose. Ian Machorton, another young officer from Column 2 described this moment in his book, ‘Safer than a Known Way’.

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel".

Eric Stephenson was responsible for writing the official War diary for Column 2 in 1943. This is how he recorded the events of the 2nd March:

“At 22.00 hours according to orders from the Officer commanding No. 1 Group (Southern Section), No. 2 Column formed up on the small branch railway line and prepared to advance on Kyaikthin. No sooner had the column commenced its advance, than enemy machine guns opened fire. It was obvious that the column had walked into a strong and cleverly laid ambush and the valuable weapon of surprise had been snatched from us.

A vigorous encounter began. Major Emmett ordered an immediate counter attack, but this was beaten off by the enemy, and then attempts were made by both sides to out-flank and infiltrate. Either by good fortune or knowledge gained, the enemy mortar fire began to fall among the animals. These were already badly frightened and this caused terrific pandemonium, of which the enemy took full advantage by gaining ground and infiltrating.

After the engagement had gone on for two hours, the second dispersal call was sounded and the Column began to move away in groups. Jemadar Manbahadur Gurung, commanding the platoon detailed to cover dispersal put up a wonderful show, remaining in position to inflict a considerable number of casualties on the enemy. The column did not succeed in re-forming after this engagement, but the majority regained the Chindwin in several separate parties.”

As Eric has described, most of Column 2 turned and headed back to India after the disaster at Kyaikthin. This was not the agreed plan however and Major Emmett was to receive heavy criticism from Brigadier Wingate for his leadership of Column 2 after the operation was over.

After re-grouping some of the men from Column 2 did push on to the formerly agreed rendezvous location close to the western banks of the Irrawaddy River. Lieutenant Eric Stephenson was amongst these men, leading his small group of Gurkha Riflemen away from their terrifying ordeal at Kyaikthin and hoping to meet up with the rest of Southern Group.

Eric did meet up with the Burma Rifle platoon of Column 2 and came under the command of the senior officer of this group, Captain George Power Carne. The two groups then patrolled the local area for a further 5 weeks, providing useful reconnaissance for the other Chindit columns still operating further north. Eventually the decision was made to disperse and Lieutenant Stephenson and his Gurkhas returned to India.

George Power Carne was the officer in charge of the Guerrilla Platoon within Chindit Column 2 on Operation Longcloth. This unit was responsible for relaying pro-British propaganda to the Burmese villages it passed through during the early months of 1943. For his efforts on Operation Longcloth, Captain Carne was awarded the Military Cross. Here is the official recommendation for that award, as written by Lt. Colonel P. C. Buchanan, the officer commanding 2nd Burma Rifles by the close of the first Chindit expedition:

On the night 2/3 March 1943, No. 2 Column was ambushed at Kyaikthin. Captain Carne, who commanded its Guerilla Platoon, was some miles ahead of the spot where the action took place. In the confusion which resulted he was unable to ascertain the fate of the force, the only party of survivors which he encountered being one weak platoon of Gurkhas. A vigorous search in the area established that the Dispersal Groups into which the column had split had made their way back to the Chindwin River, a course which Captain Carne would have been fully justified in himself pursuing.

He preferred, however, to cross the Irrawaddy with the small party at his disposal in the hopes of meeting with the main body of the Brigade; and he carried out this decision although without wireless and without any means of knowing what alterations might have been made in the Brigade plans. Although he unfortunately failed to locate and join the Brigade, he boldly led his party across the Shweli River and into the Kachin Hills returning to India after a remarkable march which was the more praiseworthy in that his men were naturally depressed by the circumstances in which it had begun. His refusal to take the obvious and easy course back to the Chindwin and his choice to embark instead on a daring journey five times as long through enemy country shows this officer to be the possessor of a soldierly instinct in a high degree.

Eric Stephenson recommended his own Gurkha Sergeant, Havildar Ran Sing Gurung, for the award of an Indian Distinguished Service Medal in recognition of his valiant service on Operation Longcloth. Here is the official recommendation as submitted by Eric after his return to India:

Havildar Ran Sing Gurung IDSM

Action for which recommended:

Operations in Burma, March/April 1943.

On 3rd March, 1943, the column to which this N.C.O. belonged was ambushed near Kyaikthin. He was one was a small party which, with a British Officer, joined up with a platoon of Burma Riflemen and set out on a prolonged march across the Irrawaddy and through the Kachin Hills. Throughout the period he proved himself an admirable N.C.O. of great courage and resource, and was of the utmost assistance to his commander.

IDSM Recommended By: Lt. J.E.Stephenson (Column 2)

3/2nd Gurkha Rifles

77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Obviously the first Chindit operation was shrouded in secrecy and none of the families back in Britain had any idea what their particular soldier had been up to during the months of February-July 1943. On his return to India and probably during his recuperation period, spent in the Darjeeling area of Assam, Eric sent a short letter to his eldest daughter, Janet.

“Do you know what a little bird has told me? That you are now going to school. And then I got your lovely little letter, which told me that very same thing. Will you write and tell me all about it please?

I have not been able to write for such a long time …..

And now you have a baby sister! Do you love her and do you help mummy to do things now? What a big girl you must have grown into since I last saw you. You would have laughed a lot if you had seen me a short time ago. Dad had a big moustache, a beard and ever such long hair. I did look funny and I had to shave more than once before it all came off.

Goodbye darling. Write to me again soon.”

After his rest period was over Eric returned to his Regimental Centre at Dehra Dun, where the men from the 3rd battalion were beginning to re-assemble. Their next posting would take them back into Burma, but this time to the Arakan region on the eastern coastline of the Bay of Bengal. In late 1943, 3/2 GR joined the 74th Infantry Brigade, part of the 25th Indian Division and moved down to Tamil Nadu for renewed jungle training. By February the battalion were based close to Bangalore and then travelled from Calcutta by ship to Chittagong.

The newly promoted Captain Stephenson took command of C’ Company within the battalion and the unit began it’s acclimatisation to conditions in the Arakan. The region was a mixture of tidal estuaries, swampland, coastal beaches and razor-backed hills covered in dense humid jungle. During the monsoon period, roughly May through September, this disease-ridden land became a liquid morass, seriously impeding the movements of even the most lightly armed soldier.

From the 25th Indian Division’s own war history, comes this description of the conditions and fighting in the Arakan:

“The rains burst over the jungle. Tempers were tested to the limit. Tarpaulins covering hillside dugouts collapsed under the weight of collected water, half drowning the occupants. Hillside tracks became raging watercourses. Fallen trees and landslides made trails impassible.

But through the seven soggy months, drenched to the skin for days on end, the men of the 25th Indian Division never let up their pursuit of the enemy wherever he could be found. Bogged lines of communication ruled out large-scale actions. This was a war of little patrols, small raids and ambushes in the dripping jungle. But it was a killing war.”

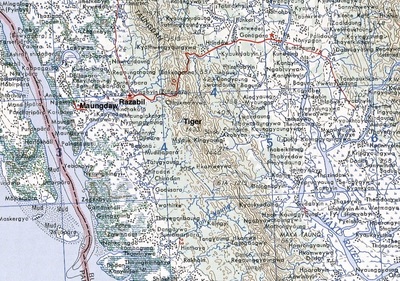

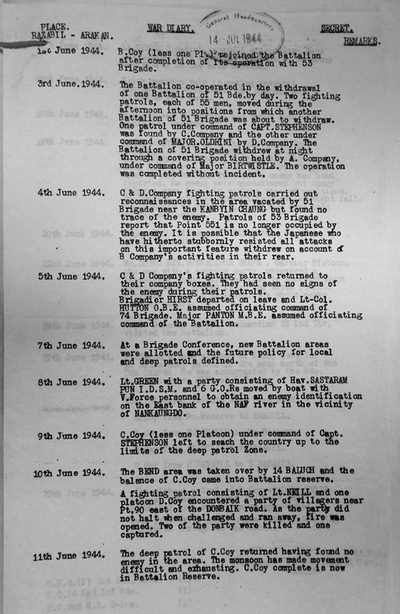

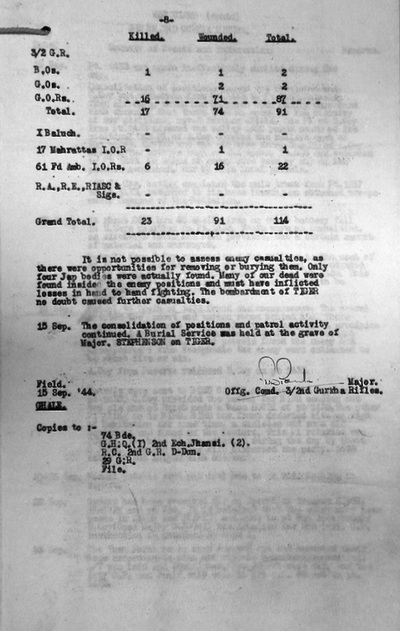

Seen in the gallery below is a map of the area in which Eric and the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles operated in 1944, also shown are some of the pages from the battalion's War diary for those long and arduous months. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

On the night 2/3 March 1943, No. 2 Column was ambushed at Kyaikthin. Captain Carne, who commanded its Guerilla Platoon, was some miles ahead of the spot where the action took place. In the confusion which resulted he was unable to ascertain the fate of the force, the only party of survivors which he encountered being one weak platoon of Gurkhas. A vigorous search in the area established that the Dispersal Groups into which the column had split had made their way back to the Chindwin River, a course which Captain Carne would have been fully justified in himself pursuing.

He preferred, however, to cross the Irrawaddy with the small party at his disposal in the hopes of meeting with the main body of the Brigade; and he carried out this decision although without wireless and without any means of knowing what alterations might have been made in the Brigade plans. Although he unfortunately failed to locate and join the Brigade, he boldly led his party across the Shweli River and into the Kachin Hills returning to India after a remarkable march which was the more praiseworthy in that his men were naturally depressed by the circumstances in which it had begun. His refusal to take the obvious and easy course back to the Chindwin and his choice to embark instead on a daring journey five times as long through enemy country shows this officer to be the possessor of a soldierly instinct in a high degree.

Eric Stephenson recommended his own Gurkha Sergeant, Havildar Ran Sing Gurung, for the award of an Indian Distinguished Service Medal in recognition of his valiant service on Operation Longcloth. Here is the official recommendation as submitted by Eric after his return to India:

Havildar Ran Sing Gurung IDSM

Action for which recommended:

Operations in Burma, March/April 1943.

On 3rd March, 1943, the column to which this N.C.O. belonged was ambushed near Kyaikthin. He was one was a small party which, with a British Officer, joined up with a platoon of Burma Riflemen and set out on a prolonged march across the Irrawaddy and through the Kachin Hills. Throughout the period he proved himself an admirable N.C.O. of great courage and resource, and was of the utmost assistance to his commander.

IDSM Recommended By: Lt. J.E.Stephenson (Column 2)

3/2nd Gurkha Rifles

77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

Obviously the first Chindit operation was shrouded in secrecy and none of the families back in Britain had any idea what their particular soldier had been up to during the months of February-July 1943. On his return to India and probably during his recuperation period, spent in the Darjeeling area of Assam, Eric sent a short letter to his eldest daughter, Janet.

“Do you know what a little bird has told me? That you are now going to school. And then I got your lovely little letter, which told me that very same thing. Will you write and tell me all about it please?

I have not been able to write for such a long time …..

And now you have a baby sister! Do you love her and do you help mummy to do things now? What a big girl you must have grown into since I last saw you. You would have laughed a lot if you had seen me a short time ago. Dad had a big moustache, a beard and ever such long hair. I did look funny and I had to shave more than once before it all came off.

Goodbye darling. Write to me again soon.”

After his rest period was over Eric returned to his Regimental Centre at Dehra Dun, where the men from the 3rd battalion were beginning to re-assemble. Their next posting would take them back into Burma, but this time to the Arakan region on the eastern coastline of the Bay of Bengal. In late 1943, 3/2 GR joined the 74th Infantry Brigade, part of the 25th Indian Division and moved down to Tamil Nadu for renewed jungle training. By February the battalion were based close to Bangalore and then travelled from Calcutta by ship to Chittagong.

The newly promoted Captain Stephenson took command of C’ Company within the battalion and the unit began it’s acclimatisation to conditions in the Arakan. The region was a mixture of tidal estuaries, swampland, coastal beaches and razor-backed hills covered in dense humid jungle. During the monsoon period, roughly May through September, this disease-ridden land became a liquid morass, seriously impeding the movements of even the most lightly armed soldier.

From the 25th Indian Division’s own war history, comes this description of the conditions and fighting in the Arakan:

“The rains burst over the jungle. Tempers were tested to the limit. Tarpaulins covering hillside dugouts collapsed under the weight of collected water, half drowning the occupants. Hillside tracks became raging watercourses. Fallen trees and landslides made trails impassible.

But through the seven soggy months, drenched to the skin for days on end, the men of the 25th Indian Division never let up their pursuit of the enemy wherever he could be found. Bogged lines of communication ruled out large-scale actions. This was a war of little patrols, small raids and ambushes in the dripping jungle. But it was a killing war.”

Seen in the gallery below is a map of the area in which Eric and the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles operated in 1944, also shown are some of the pages from the battalion's War diary for those long and arduous months. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Even during this period, with rain driving down day after day, Eric still managed to write home, telling his family about his daily existence, at least to the extent at which the Army Postal censor would allow.

Eric was joined in the Arakan by some of the men that had previously served with him on Operation Longcloth. From the officers, came George Silcock, Berty Birtwhistle, Nick Neill, ‘Jock’ Stuart-Jones and Richard Scamander Clarke. It is difficult to say how many of the Gurkha Riflemen that returned from Burma after the first Chindit Operation went on to serve in the Arakan, but there must have been a good number.

By late July 1944 the battalion had been involved in several actions against the Japanese, most seemingly successful in their outcome. From the Battalion War diary:

“The casualties inflicted on the enemy in the Task Force operations are known to be at least 80 killed and 2 captured, without a single casualty to ourselves. During the last three weeks of the month (July) heavy monsoon rain has fallen without a break. The whole of the Razabil area was subjected to very heavy air attacks and artillery bombardments, pulverizing the hillsides, before it was captured from the Japanese.”

Soon after this period Eric Stephenson was promoted to the rank of Major and the battalion’s focus became centered on the map reference point 1433 which the men nicknamed ‘Tiger’. The overreaching aim of the battalion was to assist in the re-capture of the Mayu Range of hills from the Japanese. This position was of strategic importance, as it would enable the Allies to once again control the important port of Akyab.

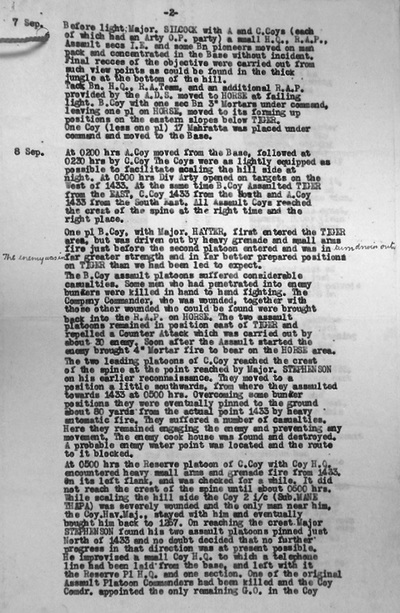

From the Battalion War diary dated 1st September 1944:

“The main spine of the Mayu Range drops steeply down to ravines 1200 ft and more below. The sides of the Range are covered with dense jungle and movement on them is further restricted by deep gorges scoured out by rain. The monsoon makes the whole area extremely slippery and restricts observation. Past attempts to attack Jap positions frontally along the spine had proved costly and it was accordingly decide to attack 1433 from a flank. The hillsides are a little less steep on the East than on the West. Recce patrols eventually reported that it would not be possible to scale the cliffs on the west of 1433 and so recce was concentrated on the East. Tiger, a feature 500 yards North of 1433 was found to be held by the enemy.”

One week later on the 8th September two units of the battalion moved up to attack the enemy position:

“At 0200 hours A Coy moved from the Base followed at 0230 hours by C Coy. The units were as lightly equipped as possible to facilitate scaling the hillside at night. At 0500 hours artillery opened on targets to the West of 1433. At the same time B Coy assaulted Tiger from the East and C Coy 1433 from the North and A Coy from the South East. All assault coys reached the crest of the spine at the right time and the right place.

The B company platoons entered the Tiger area but the enemy, in greater strength and better prepared than expected, inflicted many casualties and the Gurkhas were driven back. The diary continues:

"The two leading platoons of C Coy reached the crest of the spine at the point reached by Major Stephenson in his earlier reconnaissance. They moved to a position a little southward, from where they assaulted towards 1433 at 0500 hours. On reaching the crest Major Stephenson found his two assault platoons pinned just north of 1433 and no doubt decided that no further progress in that direction was at present possible. He improvised a small Company HQ to which a telephone line had been laid from the base and left it with the Reserve Platoon HQ.

It appears that he decided to recce northwards towards Tiger where B Coy might have arrived. Taking Jemadar Dhurbu and two sections from the Reserve Platoon he set off. One section was established in a strong supporting position about halfway between Coy HQ and Tiger and he went on with the remainder of his party. On reaching the vicinity of Tiger he left Jemadar Dhurbu and the remaining section in position and, in spite of protests, went forward alone to reconnoitre. He was killed on a bunker position in Tiger.”

The 3/2 GR diary mentions another hard fought assault on Tiger and on the 14th September the operation was judged to be a significant strategic success. The death of Major Stephenson was deeply felt by all in the battalion from both officers and Riflemen alike. Dominic Neill, who had served with Eric on Operation Longcloth in 1943, was kind enough to correspond with the family in 1995. Here is how he remembered the attack on Point 1433:

“The Battalion's objectives were, as already mentioned, Point 1433 and, 500 yards to its north, the feature known as Tiger. The two objectives were held by two Japanese companies of the 1st Battalion, 143 Regiment, of the famous and greatly experienced Japanese 55th Division.

Colonel Reggie's plan for the attack, in outline, was as follows. H hour (the start of the action) was to be at 0500hours on 8th September. At H hour, the division artillery was to bombard Point 904 and Bird, (two other geographical points) both some one and one-quarter miles to the south and south-west of 1433.

The bombardment was diversionary, in order to deceive the Jap companies into believing that 904 and Bird were to be the objectives of the British attack. It was I think an error of judgment, as its main achievement was to alert the Japs on 1433 and Tiger and cause them to stand to. They were therefore ready and waiting when A Company under Dickie Clarke, assaulted 1433 from the south and C Company under Steve (Eric's nickname in the Arakan) Stephenson, probed the same feature from the north.

At the same time, B Company ...was to hit Tiger from the east.....I remember so well, after he'd received his orders Steve telling me that he felt unhappy about launching his company on to 1433 before first light, without the advantage of a daylight reconnaissance. Darkness, he said, would rob him of one of his greatest assets — the men's eagle-eyesight. He was justified in these fears, I believe. He further considered that many good men would die the following morning. Sad to say, he was correct in having such premonitions.

The Colonel and Neill were awake together to hear the start of the battle, Neill writes that this was the first time he had heard the awe-inspiring roar "Ayo Gorkhali" of a whole company of Gurkhas but that the cries were quickly silenced by the Japanese fire from the hidden bunkers on the summit of Tiger, the volume of this ferocious response was a complete surprise.

"The firefight between B Company and the Japs ...must have gone on, in decreasing intensity, for an hour or so. We had reasonable radio communications with A and C companies on 1433 and soon learned that both companies had come up against impenetrable bunker positions. Then we lost radio contact with C Company.

The commander of B Company (Adrain Hayter) was helped back to HQ with many wounds and desperate about the number of dead and wounded in his company, then:

"Jemader Dhurbusing Thapa of C Company came with further news. His Company second in command, Subadar Mane Thapa had been badly wounded on 1433, where C Company's assault had been held up. Furthermore, he told Reggie that Steve Stephenson had taken a patrol northwards from 1433 to link up with B Company on Tiger to see if he could assist in that attack, as his own had had no success. Dhurba went on to say that Steve had been killed attacking a bunker on Tiger. Having given his report Dhurba returned to command C Company on the spine between 1433 and Tiger.

Poor Reggie, he was greatly affected by the news of Steve's death and the fact that his carefully planned battalion attack had failed. He loved all his men dearly and it was tragic to see the look in his eyes as he reported the situation to the Brigade Commander.”

Dominic Neill was able to take a small party of Riflemen up onto Tiger a few days later. Amongst the bodies of the men from C’ Company he found that of his great comrade Eric Stephenson. In the brave officer’s breast pocket was the yellow lead pencil he had used to write those loving letters to his family. Eric Stephenson was buried, close to where he fell on the 15th September 1944.

Seen in the gallery below are some images in relation to Eric Stephenson and his time in the Arakan. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Eric was joined in the Arakan by some of the men that had previously served with him on Operation Longcloth. From the officers, came George Silcock, Berty Birtwhistle, Nick Neill, ‘Jock’ Stuart-Jones and Richard Scamander Clarke. It is difficult to say how many of the Gurkha Riflemen that returned from Burma after the first Chindit Operation went on to serve in the Arakan, but there must have been a good number.

By late July 1944 the battalion had been involved in several actions against the Japanese, most seemingly successful in their outcome. From the Battalion War diary:

“The casualties inflicted on the enemy in the Task Force operations are known to be at least 80 killed and 2 captured, without a single casualty to ourselves. During the last three weeks of the month (July) heavy monsoon rain has fallen without a break. The whole of the Razabil area was subjected to very heavy air attacks and artillery bombardments, pulverizing the hillsides, before it was captured from the Japanese.”

Soon after this period Eric Stephenson was promoted to the rank of Major and the battalion’s focus became centered on the map reference point 1433 which the men nicknamed ‘Tiger’. The overreaching aim of the battalion was to assist in the re-capture of the Mayu Range of hills from the Japanese. This position was of strategic importance, as it would enable the Allies to once again control the important port of Akyab.

From the Battalion War diary dated 1st September 1944:

“The main spine of the Mayu Range drops steeply down to ravines 1200 ft and more below. The sides of the Range are covered with dense jungle and movement on them is further restricted by deep gorges scoured out by rain. The monsoon makes the whole area extremely slippery and restricts observation. Past attempts to attack Jap positions frontally along the spine had proved costly and it was accordingly decide to attack 1433 from a flank. The hillsides are a little less steep on the East than on the West. Recce patrols eventually reported that it would not be possible to scale the cliffs on the west of 1433 and so recce was concentrated on the East. Tiger, a feature 500 yards North of 1433 was found to be held by the enemy.”

One week later on the 8th September two units of the battalion moved up to attack the enemy position:

“At 0200 hours A Coy moved from the Base followed at 0230 hours by C Coy. The units were as lightly equipped as possible to facilitate scaling the hillside at night. At 0500 hours artillery opened on targets to the West of 1433. At the same time B Coy assaulted Tiger from the East and C Coy 1433 from the North and A Coy from the South East. All assault coys reached the crest of the spine at the right time and the right place.

The B company platoons entered the Tiger area but the enemy, in greater strength and better prepared than expected, inflicted many casualties and the Gurkhas were driven back. The diary continues:

"The two leading platoons of C Coy reached the crest of the spine at the point reached by Major Stephenson in his earlier reconnaissance. They moved to a position a little southward, from where they assaulted towards 1433 at 0500 hours. On reaching the crest Major Stephenson found his two assault platoons pinned just north of 1433 and no doubt decided that no further progress in that direction was at present possible. He improvised a small Company HQ to which a telephone line had been laid from the base and left it with the Reserve Platoon HQ.

It appears that he decided to recce northwards towards Tiger where B Coy might have arrived. Taking Jemadar Dhurbu and two sections from the Reserve Platoon he set off. One section was established in a strong supporting position about halfway between Coy HQ and Tiger and he went on with the remainder of his party. On reaching the vicinity of Tiger he left Jemadar Dhurbu and the remaining section in position and, in spite of protests, went forward alone to reconnoitre. He was killed on a bunker position in Tiger.”

The 3/2 GR diary mentions another hard fought assault on Tiger and on the 14th September the operation was judged to be a significant strategic success. The death of Major Stephenson was deeply felt by all in the battalion from both officers and Riflemen alike. Dominic Neill, who had served with Eric on Operation Longcloth in 1943, was kind enough to correspond with the family in 1995. Here is how he remembered the attack on Point 1433:

“The Battalion's objectives were, as already mentioned, Point 1433 and, 500 yards to its north, the feature known as Tiger. The two objectives were held by two Japanese companies of the 1st Battalion, 143 Regiment, of the famous and greatly experienced Japanese 55th Division.

Colonel Reggie's plan for the attack, in outline, was as follows. H hour (the start of the action) was to be at 0500hours on 8th September. At H hour, the division artillery was to bombard Point 904 and Bird, (two other geographical points) both some one and one-quarter miles to the south and south-west of 1433.

The bombardment was diversionary, in order to deceive the Jap companies into believing that 904 and Bird were to be the objectives of the British attack. It was I think an error of judgment, as its main achievement was to alert the Japs on 1433 and Tiger and cause them to stand to. They were therefore ready and waiting when A Company under Dickie Clarke, assaulted 1433 from the south and C Company under Steve (Eric's nickname in the Arakan) Stephenson, probed the same feature from the north.

At the same time, B Company ...was to hit Tiger from the east.....I remember so well, after he'd received his orders Steve telling me that he felt unhappy about launching his company on to 1433 before first light, without the advantage of a daylight reconnaissance. Darkness, he said, would rob him of one of his greatest assets — the men's eagle-eyesight. He was justified in these fears, I believe. He further considered that many good men would die the following morning. Sad to say, he was correct in having such premonitions.

The Colonel and Neill were awake together to hear the start of the battle, Neill writes that this was the first time he had heard the awe-inspiring roar "Ayo Gorkhali" of a whole company of Gurkhas but that the cries were quickly silenced by the Japanese fire from the hidden bunkers on the summit of Tiger, the volume of this ferocious response was a complete surprise.

"The firefight between B Company and the Japs ...must have gone on, in decreasing intensity, for an hour or so. We had reasonable radio communications with A and C companies on 1433 and soon learned that both companies had come up against impenetrable bunker positions. Then we lost radio contact with C Company.

The commander of B Company (Adrain Hayter) was helped back to HQ with many wounds and desperate about the number of dead and wounded in his company, then:

"Jemader Dhurbusing Thapa of C Company came with further news. His Company second in command, Subadar Mane Thapa had been badly wounded on 1433, where C Company's assault had been held up. Furthermore, he told Reggie that Steve Stephenson had taken a patrol northwards from 1433 to link up with B Company on Tiger to see if he could assist in that attack, as his own had had no success. Dhurba went on to say that Steve had been killed attacking a bunker on Tiger. Having given his report Dhurba returned to command C Company on the spine between 1433 and Tiger.

Poor Reggie, he was greatly affected by the news of Steve's death and the fact that his carefully planned battalion attack had failed. He loved all his men dearly and it was tragic to see the look in his eyes as he reported the situation to the Brigade Commander.”

Dominic Neill was able to take a small party of Riflemen up onto Tiger a few days later. Amongst the bodies of the men from C’ Company he found that of his great comrade Eric Stephenson. In the brave officer’s breast pocket was the yellow lead pencil he had used to write those loving letters to his family. Eric Stephenson was buried, close to where he fell on the 15th September 1944.

Seen in the gallery below are some images in relation to Eric Stephenson and his time in the Arakan. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Later on, after the war was over Dominic Neill wrote a journal of his time in the 2nd Gurkha Rifles. Part of this memoir included a passage about Eric Stephenson; here is what he had to say about him:

“And why have I written about Steve at some length in this journal? This is our final Journal before the 2nd Goorkhas departs from the Army List. Very few members of the Regiment who will read this Journal have ever heard of his name. I wanted, in this final journal, to let all of you in the Regiment know of him and to understand how he died on Tiger, nearly half a century ago.

He died as I said earlier two arms' length away from that Jap bunker. No one, apart from his small party from C Company who went with him to help B Company on Tiger, saw exactly what he did. Those Gurkhas cannot tell us his story — because they all died too, on that ill-starred morning. But, for my money, and with my intimate knowledge of Steve as a friend and my familiarity gained from experience of the Japanese soldier as an indomitable fighting man, I would say to you that Steve's actions, on the morning of 8th September 1944 were the stuff of which VC's are made. My story is, therefore, I hope, a tribute to Steve who was a British Officer fit to lead the Gurkhas in battle.

Why did Steve do what he did on Tiger, when he went to see if he could help Adrian's (Adrian Hayter) B company? Why did he, perhaps, attack that bunker single-handed? Why does any man do what he does in war? I can tell you quite simply. Steve did what he did because he knew who he was and what he was — he was a SECOND Goorkha. Like all good soldiers in all good regiments, his regiment's number meant everything to him; it motivated him to the point of giving his life. A regiment's number can mean so much to fighting men that, at times the certain knowledge of who one is, and what one is, makes all the difference between defeat and victory.”

Two weeks after Eric died, Olive Stephenson received this letter from the commanding officer of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles, Lieutenant-Colonel Reginald Hutton:

Dear Mrs. Stephenson,

I, and all the officers and men under my command, offer you and your children our sincerest sympathy. We ourselves miss your husband sadly but we fully realise how much greater is your loss. We feel deeply for you.

Your Eric died a happy warrior. He was killed instantly on the edge of a Japanese position in a remote part of Burma. We buried him where he lay on the top of a jungle covered mountain. A Service of Remembrance was held at his graveside soon afterwards.

We are placing a memorial over his grave and will provide a more permanent mark of our respect in Dehra Dun. A few words of your husband's favourite quotation from Rupert Brooke, ("and if I should die, think only this of me..."), form the end of the inscription on his headstone.

This reads: -

Major J E Stephenson-2nd K.E.O. Gurkha Rifles.

Killed in action-8th September 1944

'Our Steve' Who died, as he would have wished, gallantly leading Gurkhas whom he loved and served so well.

Forever England.

Be of good heart and take courage from the knowledge that Eric did not live or die in vain. His sterling worth will remain an inspiring example to us all, both now in the war and in the years of peace to come.

Yours sincerely, Lt-Col. R. Hutton.

Leeds United paid tribute to Eric’s passing with an announcement in their match day programme for Saturday 11th November 1944. Two years later, on the 27th May 1947 they held a benefit match in his memory, with Leeds playing against Glasgow Celtic. The proceeds from the match went to the Stephenson family.

For more details about this benefit match, please click on the following link:

http://www.celticprogrammesonline.com/PROGRAMME%20COVERS/4647/leeds/leeds4647a.htm

Later on, after the war was over, any known burial sites for Allied casualties were re-visited by the Imperial War Graves Commission. Because of the care and attention given by the men of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles to Eric’s original resting place, it was possible to remove his remains from Tiger Point and have them re-interred at Taukkyan War Cemetery located on the northern outskirts of Rangoon.

Eric’s eldest daughter, Jan, has visited her father’s grave at Taukkyan and recounts this emotional experience in her book:

“We visited Taukkyan Cemetery again before leaving Myanmar. Since my visit I have a sense that I know my father more, both through writing this memoir and by going to Myanmar. I still feel with all my heart that it would have been far, far better to have grown up with him, but I do feel close to his warm, humorous, lively personality.

I recognise and can appreciate his determination, courage, leadership and his generous acceptance of other people. I have enjoyed writing about his skills at sport and his insistence that the spirit of the game was more important than the outcome. One memory I do have: I am looking up at him, he is on the flat roof of the little outhouse in our garden, wearing a khaki uniform and he is dancing to make me laugh, the more I laugh the more he jigs around. He was a lot of fun.”

Eric Stephenson has another memorial in his honour which is much closer to home. It can be found at Lidgett Park Methodist Church in Roundhay, the same church in which Eric and Olive Stephenson were married back in May 1938. The memorial comes in the form of a stained glass chancel window found in the west end of the church. Eric is remembered on the inner left panel of the window showing St. Michael, which was dedicated in 1948.

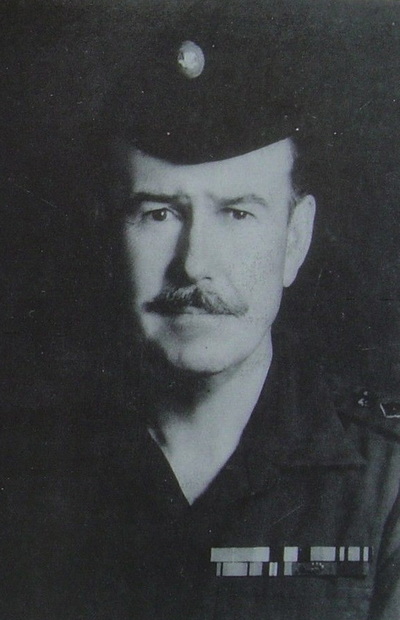

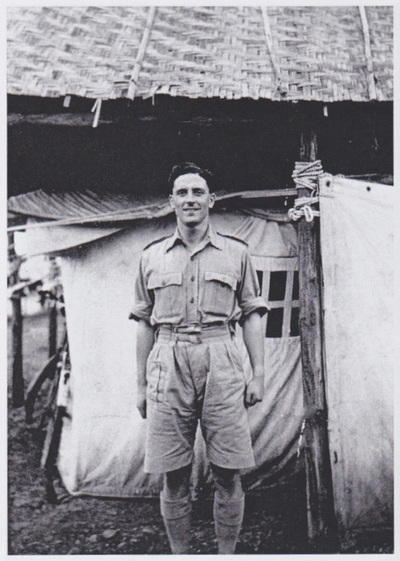

Seen below is a final gallery of images illustrating the story of Eric Stephenson. These include two photographs of him during his time in India and Burma, an image of the stained glass window at Lidgett Park Methodist Church and his memorial plaque at Taukkyan War Cemetery. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

“And why have I written about Steve at some length in this journal? This is our final Journal before the 2nd Goorkhas departs from the Army List. Very few members of the Regiment who will read this Journal have ever heard of his name. I wanted, in this final journal, to let all of you in the Regiment know of him and to understand how he died on Tiger, nearly half a century ago.

He died as I said earlier two arms' length away from that Jap bunker. No one, apart from his small party from C Company who went with him to help B Company on Tiger, saw exactly what he did. Those Gurkhas cannot tell us his story — because they all died too, on that ill-starred morning. But, for my money, and with my intimate knowledge of Steve as a friend and my familiarity gained from experience of the Japanese soldier as an indomitable fighting man, I would say to you that Steve's actions, on the morning of 8th September 1944 were the stuff of which VC's are made. My story is, therefore, I hope, a tribute to Steve who was a British Officer fit to lead the Gurkhas in battle.

Why did Steve do what he did on Tiger, when he went to see if he could help Adrian's (Adrian Hayter) B company? Why did he, perhaps, attack that bunker single-handed? Why does any man do what he does in war? I can tell you quite simply. Steve did what he did because he knew who he was and what he was — he was a SECOND Goorkha. Like all good soldiers in all good regiments, his regiment's number meant everything to him; it motivated him to the point of giving his life. A regiment's number can mean so much to fighting men that, at times the certain knowledge of who one is, and what one is, makes all the difference between defeat and victory.”

Two weeks after Eric died, Olive Stephenson received this letter from the commanding officer of the 3/2 Gurkha Rifles, Lieutenant-Colonel Reginald Hutton:

Dear Mrs. Stephenson,

I, and all the officers and men under my command, offer you and your children our sincerest sympathy. We ourselves miss your husband sadly but we fully realise how much greater is your loss. We feel deeply for you.

Your Eric died a happy warrior. He was killed instantly on the edge of a Japanese position in a remote part of Burma. We buried him where he lay on the top of a jungle covered mountain. A Service of Remembrance was held at his graveside soon afterwards.

We are placing a memorial over his grave and will provide a more permanent mark of our respect in Dehra Dun. A few words of your husband's favourite quotation from Rupert Brooke, ("and if I should die, think only this of me..."), form the end of the inscription on his headstone.

This reads: -

Major J E Stephenson-2nd K.E.O. Gurkha Rifles.

Killed in action-8th September 1944

'Our Steve' Who died, as he would have wished, gallantly leading Gurkhas whom he loved and served so well.

Forever England.

Be of good heart and take courage from the knowledge that Eric did not live or die in vain. His sterling worth will remain an inspiring example to us all, both now in the war and in the years of peace to come.

Yours sincerely, Lt-Col. R. Hutton.

Leeds United paid tribute to Eric’s passing with an announcement in their match day programme for Saturday 11th November 1944. Two years later, on the 27th May 1947 they held a benefit match in his memory, with Leeds playing against Glasgow Celtic. The proceeds from the match went to the Stephenson family.

For more details about this benefit match, please click on the following link:

http://www.celticprogrammesonline.com/PROGRAMME%20COVERS/4647/leeds/leeds4647a.htm

Later on, after the war was over, any known burial sites for Allied casualties were re-visited by the Imperial War Graves Commission. Because of the care and attention given by the men of 3/2 Gurkha Rifles to Eric’s original resting place, it was possible to remove his remains from Tiger Point and have them re-interred at Taukkyan War Cemetery located on the northern outskirts of Rangoon.

Eric’s eldest daughter, Jan, has visited her father’s grave at Taukkyan and recounts this emotional experience in her book:

“We visited Taukkyan Cemetery again before leaving Myanmar. Since my visit I have a sense that I know my father more, both through writing this memoir and by going to Myanmar. I still feel with all my heart that it would have been far, far better to have grown up with him, but I do feel close to his warm, humorous, lively personality.

I recognise and can appreciate his determination, courage, leadership and his generous acceptance of other people. I have enjoyed writing about his skills at sport and his insistence that the spirit of the game was more important than the outcome. One memory I do have: I am looking up at him, he is on the flat roof of the little outhouse in our garden, wearing a khaki uniform and he is dancing to make me laugh, the more I laugh the more he jigs around. He was a lot of fun.”

Eric Stephenson has another memorial in his honour which is much closer to home. It can be found at Lidgett Park Methodist Church in Roundhay, the same church in which Eric and Olive Stephenson were married back in May 1938. The memorial comes in the form of a stained glass chancel window found in the west end of the church. Eric is remembered on the inner left panel of the window showing St. Michael, which was dedicated in 1948.

Seen below is a final gallery of images illustrating the story of Eric Stephenson. These include two photographs of him during his time in India and Burma, an image of the stained glass window at Lidgett Park Methodist Church and his memorial plaque at Taukkyan War Cemetery. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Medals are held in high regard within the history and folklore of Gurkha Regiments. Rightly so, as they are the recognition of brave deeds and worthy actions. Eric Stephenson would have been happy to see his young Gurkhas adorned with these ‘bahaduris’ (gallantry medals), but for himself, the knowledge that he had led them well and done his best, was reward enough for one of the most selfless and courageous of all men.

I would like to thank Jan Rippin, Robin Lee and my good friend from the WW2Talk Forum, Enes Smajic, for helping to bring the story of Major Eric Stephenson to these pages.

I thought it fitting to end with Rupert Brooke's poem, The Soldier, especially as it seems to have been a particular favourite of Eric's, or at least struck a chord in regards to his own experiences in Burma.

The Soldier

If I should die, think only this of me;

That there's some corner of a foreign field

That is forever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England's breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

Article copyright © Steve Fogden, July 2015.

I would like to thank Jan Rippin, Robin Lee and my good friend from the WW2Talk Forum, Enes Smajic, for helping to bring the story of Major Eric Stephenson to these pages.

I thought it fitting to end with Rupert Brooke's poem, The Soldier, especially as it seems to have been a particular favourite of Eric's, or at least struck a chord in regards to his own experiences in Burma.

The Soldier

If I should die, think only this of me;

That there's some corner of a foreign field

That is forever England. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;

A dust whom England bore, shaped, made aware,

Gave, once, her flowers to love, her ways to roam,

A body of England's breathing English air,

Washed by the rivers, blest by suns of home.

And think, this heart, all evil shed away,

A pulse in the eternal mind, no less

Gives somewhere back the thoughts by England given;

Her sights and sounds; dreams happy as her day;

And laughter, learnt of friends; and gentleness,

In hearts at peace, under an English heaven.

Article copyright © Steve Fogden, July 2015.