Flight Officer Michael Vlasto DFC and Bar

Michael Vlasto aboard Dakota FD-781.

Michael Vlasto aboard Dakota FD-781.

At 11.00 hours on the 28th April 1943 a C47 Dakota aircraft landed in a jungle clearing a few miles west of the Irrawaddy township of Bhamo. Eighteen sick and wounded men from 8 Column boarded the plane and flew out to the safety of India. This incident has become one of the most iconic stories to emerge from the first Chindit operation.

The RAF Dakota belonging to 31 Squadron was piloted that day by Flight Officer Michael Vlasto. His great skill and bravery in landing the plane on what was basically just a jungle clearing, was the difference between life and probable death for the stricken Chindits involved. From that moment forward, Vlasto and his heroic crew were always looked upon as honorary members of 8 Column and have been forever revered by the wider Chindit family.

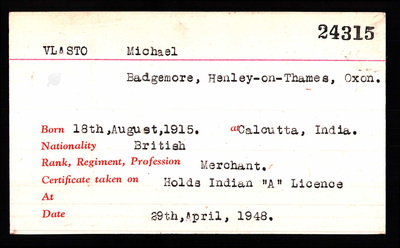

Michael Augustus Vlasto, born in Calcutta on the 18th August 1915 and was the son of Augustus Alexander and Mary Adeline Vlasto. His father's family, from a Greek Orthodox heritage, had been successful worldwide merchant traders for a number of generations.

As was common in those days, Michael was sent back to England for his education and attended Charterhouse School in Surrey, coincidently, the same school as Orde Wingate. On his return to India, he worked for Ralli Brothers at their business base in Calcutta, beginning his employment in 1936. He returned to his role with the company after WW2 ended and continued his service up until his retirement in 1966.

Ralli Brothers was a large merchant trading company with business centres all over the world. In 1851 the company expanded its empire to include the Indian cities of Calcutta and Bombay, the Vlasto family, as cousins had been heavily involved as partners over many decades.

Michael Vlasto and 31Squadron were based in India for the majority of WW2, but had served for a short while in Iraq and Egypt during 1941. On the 23rd July that year, Vlasto and fellow pilot, Flight Officer Mehar Singh took off aboard aircraft DC2, DG-471 'S', heading for Iraq. Their plane, carrying supplies which included live ammunition, crashed on take off at Karachi. He remembered:

Our DC 2's were old ones from America. We put in a lot of hours during this period and some of these aircraft were underpowered and had a tendency to swing.

Vlasto recalled another incident from earlier in his RAF service, when flying a 'Pig' (Vickers Valentia) at Abu Dhabi in the Persian Gulf:

We had been refuelling from four gallon tins on the sand strip, when the local Sheik turned up and began measuring the wings of our aircraft with his umbrella. When we asked him what he was doing, he told us he was going to make one of his own!

Later in the war, Vlasto recounted another story involving some experimentation in con-joining two makes of the Douglas Dakota aircraft:

Once we tried to make a DC-2.5 at Bangalore by putting DC-3 engines on to a DC-2. The resulting plane flew quite fast, but when I was waiting to fly it back to Lahore, a character called Flight Sergeant Herring from 194 Squadron, swung his Hudson whilst landing at Bangalore and wrote the 2.5 off. To be honest, I was rather relieved as I wondered how long the old airframe could stand it.

On the 19th July 1942, Michael was flying a supply sortie from Dinjan to Hkalak Ga, a village in Burma close to the Assam border and the famous Ledo Road. Included in the cargo were ten packets containing solid silver rupees, these were destined for the Special Forces (V Force) units based in the area and were to be used to pay local tribesmen for their assistance in the fight against the Japanese. The V Force operatives on the receiving end of this worthy supply drop recorded in their next report to rear base:

Congratulations to the pilot (Vic Lazell) who dropped the money, he did some good shooting and 9 out of the 10 packets were successfully collected.

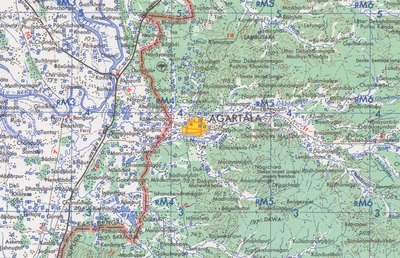

In early 1943, Vlasto was awarded the first of his two Mention in Despatches for his service with 31 Squadron whilst supplying Allied units in Northern Burma. In February 1943, 31 Squadron began supply drops to Operation Longcloth, firstly, from their original air base at Dhubalia and then subsequently from Agartala.

The RAF Dakota belonging to 31 Squadron was piloted that day by Flight Officer Michael Vlasto. His great skill and bravery in landing the plane on what was basically just a jungle clearing, was the difference between life and probable death for the stricken Chindits involved. From that moment forward, Vlasto and his heroic crew were always looked upon as honorary members of 8 Column and have been forever revered by the wider Chindit family.

Michael Augustus Vlasto, born in Calcutta on the 18th August 1915 and was the son of Augustus Alexander and Mary Adeline Vlasto. His father's family, from a Greek Orthodox heritage, had been successful worldwide merchant traders for a number of generations.

As was common in those days, Michael was sent back to England for his education and attended Charterhouse School in Surrey, coincidently, the same school as Orde Wingate. On his return to India, he worked for Ralli Brothers at their business base in Calcutta, beginning his employment in 1936. He returned to his role with the company after WW2 ended and continued his service up until his retirement in 1966.

Ralli Brothers was a large merchant trading company with business centres all over the world. In 1851 the company expanded its empire to include the Indian cities of Calcutta and Bombay, the Vlasto family, as cousins had been heavily involved as partners over many decades.

Michael Vlasto and 31Squadron were based in India for the majority of WW2, but had served for a short while in Iraq and Egypt during 1941. On the 23rd July that year, Vlasto and fellow pilot, Flight Officer Mehar Singh took off aboard aircraft DC2, DG-471 'S', heading for Iraq. Their plane, carrying supplies which included live ammunition, crashed on take off at Karachi. He remembered:

Our DC 2's were old ones from America. We put in a lot of hours during this period and some of these aircraft were underpowered and had a tendency to swing.

Vlasto recalled another incident from earlier in his RAF service, when flying a 'Pig' (Vickers Valentia) at Abu Dhabi in the Persian Gulf:

We had been refuelling from four gallon tins on the sand strip, when the local Sheik turned up and began measuring the wings of our aircraft with his umbrella. When we asked him what he was doing, he told us he was going to make one of his own!

Later in the war, Vlasto recounted another story involving some experimentation in con-joining two makes of the Douglas Dakota aircraft:

Once we tried to make a DC-2.5 at Bangalore by putting DC-3 engines on to a DC-2. The resulting plane flew quite fast, but when I was waiting to fly it back to Lahore, a character called Flight Sergeant Herring from 194 Squadron, swung his Hudson whilst landing at Bangalore and wrote the 2.5 off. To be honest, I was rather relieved as I wondered how long the old airframe could stand it.

On the 19th July 1942, Michael was flying a supply sortie from Dinjan to Hkalak Ga, a village in Burma close to the Assam border and the famous Ledo Road. Included in the cargo were ten packets containing solid silver rupees, these were destined for the Special Forces (V Force) units based in the area and were to be used to pay local tribesmen for their assistance in the fight against the Japanese. The V Force operatives on the receiving end of this worthy supply drop recorded in their next report to rear base:

Congratulations to the pilot (Vic Lazell) who dropped the money, he did some good shooting and 9 out of the 10 packets were successfully collected.

In early 1943, Vlasto was awarded the first of his two Mention in Despatches for his service with 31 Squadron whilst supplying Allied units in Northern Burma. In February 1943, 31 Squadron began supply drops to Operation Longcloth, firstly, from their original air base at Dhubalia and then subsequently from Agartala.

The story of the Dakota landing at Sonpu has been told many times on these website pages. In an attempt not to repeat the same information too many times, I have decided to use only one of the descriptive accounts available on this page. It is taken from the book 'Wingate's Lost Brigade', written by Phil Chinnery, but is in fact an amalgamation of first hand accounts given by men and journalists present at the time. My thanks must go to Philip for allowing me to reproduce his text on these pages.

Firstly, from the personal diary of Private Dennis Brown, remembering the speech that Lieutenant Colonel Cooke had made to the men, the day after they crossed the river Irrawaddy for the second time on the 20th April:

"It was not very encouraging. The gist of it was that he had orders from HQ to make the return journey to India, but that if he had his way, we would fight on to the last man and last bullet! You can image how that went down with the rank and file! I did hear that at one time he suggested that the RAF should drop soap, towels and razors, until it was pointed out that you can't eat them! The next day, our last mule, carrying the radio, keeled over and died. We radioed for one last supply drop, smashed the set and continued on our journey."

On 23rd April, Corporal Worsley fell by the side of the track. Suffering from acute jungle sores and with legs swollen to twice their normal size he could go no further. His platoon stayed behind to guide him to the next bivouac, but he would not budge and was left to follow in his own time. By now the troops were completely out of rations and water was becoming scarce. The next day Corporal Walker fell out again, this time from exhaustion. He had been suffering from dysentery for the past two weeks. Three Gurkhas fell out with him.

Company Quartermaster Sergeant Duncan Bett later recalled:

"We were all scared of being left behind. When we dropped down exhausted at night it was so dark under the jungle canopy that you could not see your hand at the end of your nose. It was like the tomb. I remember waking up suddenly once and I couldn't see a thing or hear a sound. No mules, no sentries, nothing. I thought I had been left behind when the column moved on before dawn. I scrabbled around in a panic, feeling for another body and the relief was indescribable when I felt someone else there on the ground. It seems hard to believe, but several men were left behind in the dark. Presumably they were so exhausted they didn't wake up and were not missed in the confusion when the column moved off."

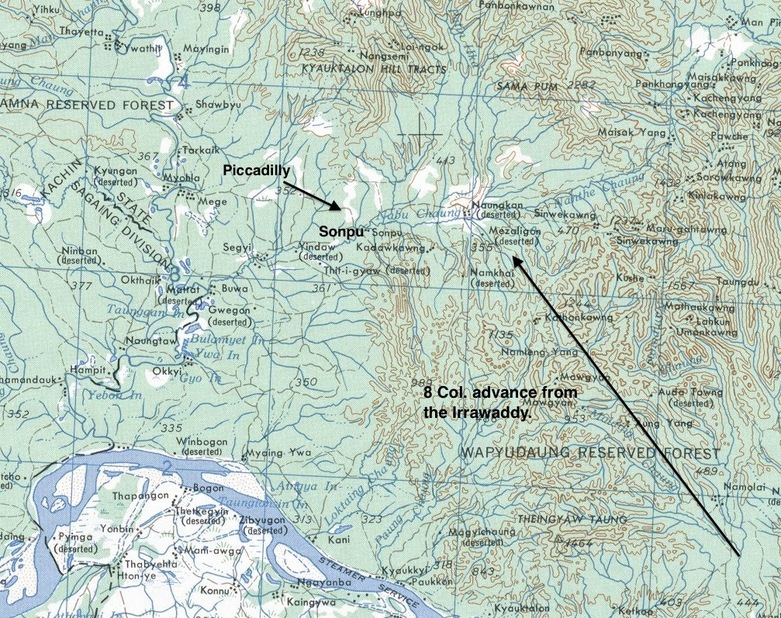

The rendezvous for the next supply drop was a clearing near Bhamo, a large town 150 miles behind Japanese lines. As he marched along through the dark jungle, Major Scott noticed that the track ahead of him was growing lighter, as if he were approaching the end of a tunnel. Soon he was standing at the edge of the jungle close to a village called Sonpu, looking out on what was probably the largest patch of open ground in northern Burma. The following day, 25th April, the Chindits scanned the sky, praying for a supply drop. Captain Johnny Carroll, the Support Group Commander, was one of them:

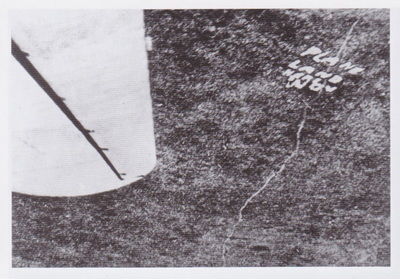

"Colonel Cooke agreed that we should work out the best area for a supply drop using white maps and socks. I suggested that we mark out PLANE LAND HERE NOW, Colonel Cooke said that we could not issue orders to the RAF and should therefore mark out REQUEST PLANE LAND HERE NOW. As the noise of a supply plane could already be heard, I suggested we start without the word REQUEST and add it later if time permitted."

The planes came over and dropped supplies to the waiting Chindits. Tommy guns, waterproof capes, bully beef, cheese and chocolate, and five days rations floated to the ground. One of the planes circled lower and saw the message. Flying Officer 'Lummie' Lord lowered his undercarriage and tried to land, but the area was too short and too rough to put down safely. The plane then made off to the west in a great hurry.

Shortly afterwards a thunderstorm burst upon them, hailstones the size of marbles fell and the troops started collecting them to eat. Only half of the rations had arrived, so the Chindits moved into bivouac to cook what they had and hope that the planes would return later. At 0600 hours the next day the planes returned and dropped enough rations for five more days. Another charged battery arrived, but there was no wireless now to send messages. They were also in desperate need of new clothing as their shirts and trousers were dropping to pieces. Many men had no sleeves to their shirts and no seats to their trousers, and many pairs of trousers had been cut down as shorts, with the result that at night the men were pestered by mosquitoes.

During the day the men were sent down to a nearby stream to bathe and to try to remove some of the lice which plagued them. On 27th April, a message was dropped to the men: 'Mark out 1,200 yard landing ground to hold twelve-ton transport.' A second message gave details of the route out taken by Major Fergusson of 5 Column who had by now found his way back to India.

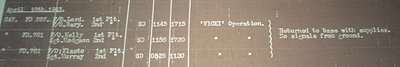

At dawn on 28th April, the Dakota rescue plane took off, escorted by eight Mohawk fighters. Flying Officer Michael Vlasto and his crew had been given a pair of Army boots each to walk home in if the plane did not land safely. When he reached the clearing, a white line was marked out on the field, together with a message: 'LAND ON WHITE LINE. GROUND THERE V.G.' The crew braced themselves as Vlasto made his approach. They touched down and the pilot hit the brakes, coming to a halt just at the end of the strip.

The plane was soon surrounded by bearded, malnourished men. But who would go out in the plane? There was only one answer: the wounded would go out first — Corporal Jimmy Walker of 7 Column, who had dropped out of the column with dysentery and an infected hip, but had dragged himself along behind them; Private Jim Suddery who had been shot in the back, the bullet going right through him; and Private Robert Hulse, shaken every couple of hours by violent fits of vomiting. Lieutenant Colonel Cooke also went aboard. This was a controversial decision which provoked much discussion among those left behind, that being, should the most senior soldier from the group leave the field ahead of his men.

Eighteen men were counted into the plane and the cargo door was closed behind them. One of them, Corporal Bert Fitton, who played left half in the company football team, helped Lieutenant Colonel Cooke and the sick and wounded into the plane, only to find himself locked in and about to take off and had to plead with the pilot to let him out. Back on the ground he told Major Scott, 'I came in on my feet and I'd like to go out the same way,' and rejoined his comrades.

Michael Vlasto gripped the control column as the end of the field rushed towards his plane. The runway was too short and they were overloaded. With knuckles white and his face dripping with sweat, he pulled back on the stick and the plane staggered into the air, brushing against the treetops below. 'God bless number eighteen,' he said.

Firstly, from the personal diary of Private Dennis Brown, remembering the speech that Lieutenant Colonel Cooke had made to the men, the day after they crossed the river Irrawaddy for the second time on the 20th April:

"It was not very encouraging. The gist of it was that he had orders from HQ to make the return journey to India, but that if he had his way, we would fight on to the last man and last bullet! You can image how that went down with the rank and file! I did hear that at one time he suggested that the RAF should drop soap, towels and razors, until it was pointed out that you can't eat them! The next day, our last mule, carrying the radio, keeled over and died. We radioed for one last supply drop, smashed the set and continued on our journey."

On 23rd April, Corporal Worsley fell by the side of the track. Suffering from acute jungle sores and with legs swollen to twice their normal size he could go no further. His platoon stayed behind to guide him to the next bivouac, but he would not budge and was left to follow in his own time. By now the troops were completely out of rations and water was becoming scarce. The next day Corporal Walker fell out again, this time from exhaustion. He had been suffering from dysentery for the past two weeks. Three Gurkhas fell out with him.

Company Quartermaster Sergeant Duncan Bett later recalled:

"We were all scared of being left behind. When we dropped down exhausted at night it was so dark under the jungle canopy that you could not see your hand at the end of your nose. It was like the tomb. I remember waking up suddenly once and I couldn't see a thing or hear a sound. No mules, no sentries, nothing. I thought I had been left behind when the column moved on before dawn. I scrabbled around in a panic, feeling for another body and the relief was indescribable when I felt someone else there on the ground. It seems hard to believe, but several men were left behind in the dark. Presumably they were so exhausted they didn't wake up and were not missed in the confusion when the column moved off."

The rendezvous for the next supply drop was a clearing near Bhamo, a large town 150 miles behind Japanese lines. As he marched along through the dark jungle, Major Scott noticed that the track ahead of him was growing lighter, as if he were approaching the end of a tunnel. Soon he was standing at the edge of the jungle close to a village called Sonpu, looking out on what was probably the largest patch of open ground in northern Burma. The following day, 25th April, the Chindits scanned the sky, praying for a supply drop. Captain Johnny Carroll, the Support Group Commander, was one of them:

"Colonel Cooke agreed that we should work out the best area for a supply drop using white maps and socks. I suggested that we mark out PLANE LAND HERE NOW, Colonel Cooke said that we could not issue orders to the RAF and should therefore mark out REQUEST PLANE LAND HERE NOW. As the noise of a supply plane could already be heard, I suggested we start without the word REQUEST and add it later if time permitted."

The planes came over and dropped supplies to the waiting Chindits. Tommy guns, waterproof capes, bully beef, cheese and chocolate, and five days rations floated to the ground. One of the planes circled lower and saw the message. Flying Officer 'Lummie' Lord lowered his undercarriage and tried to land, but the area was too short and too rough to put down safely. The plane then made off to the west in a great hurry.

Shortly afterwards a thunderstorm burst upon them, hailstones the size of marbles fell and the troops started collecting them to eat. Only half of the rations had arrived, so the Chindits moved into bivouac to cook what they had and hope that the planes would return later. At 0600 hours the next day the planes returned and dropped enough rations for five more days. Another charged battery arrived, but there was no wireless now to send messages. They were also in desperate need of new clothing as their shirts and trousers were dropping to pieces. Many men had no sleeves to their shirts and no seats to their trousers, and many pairs of trousers had been cut down as shorts, with the result that at night the men were pestered by mosquitoes.

During the day the men were sent down to a nearby stream to bathe and to try to remove some of the lice which plagued them. On 27th April, a message was dropped to the men: 'Mark out 1,200 yard landing ground to hold twelve-ton transport.' A second message gave details of the route out taken by Major Fergusson of 5 Column who had by now found his way back to India.

At dawn on 28th April, the Dakota rescue plane took off, escorted by eight Mohawk fighters. Flying Officer Michael Vlasto and his crew had been given a pair of Army boots each to walk home in if the plane did not land safely. When he reached the clearing, a white line was marked out on the field, together with a message: 'LAND ON WHITE LINE. GROUND THERE V.G.' The crew braced themselves as Vlasto made his approach. They touched down and the pilot hit the brakes, coming to a halt just at the end of the strip.

The plane was soon surrounded by bearded, malnourished men. But who would go out in the plane? There was only one answer: the wounded would go out first — Corporal Jimmy Walker of 7 Column, who had dropped out of the column with dysentery and an infected hip, but had dragged himself along behind them; Private Jim Suddery who had been shot in the back, the bullet going right through him; and Private Robert Hulse, shaken every couple of hours by violent fits of vomiting. Lieutenant Colonel Cooke also went aboard. This was a controversial decision which provoked much discussion among those left behind, that being, should the most senior soldier from the group leave the field ahead of his men.

Eighteen men were counted into the plane and the cargo door was closed behind them. One of them, Corporal Bert Fitton, who played left half in the company football team, helped Lieutenant Colonel Cooke and the sick and wounded into the plane, only to find himself locked in and about to take off and had to plead with the pilot to let him out. Back on the ground he told Major Scott, 'I came in on my feet and I'd like to go out the same way,' and rejoined his comrades.

Michael Vlasto gripped the control column as the end of the field rushed towards his plane. The runway was too short and they were overloaded. With knuckles white and his face dripping with sweat, he pulled back on the stick and the plane staggered into the air, brushing against the treetops below. 'God bless number eighteen,' he said.

William Vandivert, the war journalist present aboard FD-781 that day remembered:

"Boy was I afraid; when I looked across at the pilot after we had cleared the trees, there was a pool of sweat in his lap. Was I glad to see the tops of those trees go by!"

Michael Vlasto was awarded an immediate Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for his actions on the 28th April 1943, but probably more importantly had proved that air rescue was possible behind enemy lines in Burma. Many years after the war, 8 Column Commander, Major Walter Purcell Scott recalled the 'Piccadilly' incident at a reunion with the RAF personnel of 31 Squadron:

'Plane Land Here Now' was the request that 31 Squadron so nobly answered. This air rescue undoubtedly pioneered the air evacuation of the wounded and sick from deep inside Burma during our second Chindit campaign in 1944. It also set the pattern for all future campaigns in that theatre of war.

Before General Wingate left for Quebec and the Allied Conference held there, he told me that the air rescue carried out by 31 Squadron was an acorn, and that one day I would see it grow into an oak tree. He kept his word, and from then on air recovery of the sick and wounded took place all over South East Asia.

The inspired attempts of Lummie Lord and his crew and the final magnificent effort of Mike Vlasto and his crew, set the seal on the outstanding performance of 31 Squadron, who throughout our campaign supplied all our needs, even when we were beyond the Irrawaddy and in frightful weather and flying conditions. At times we gave the squadron some frightful dropping areas, varying from mountain tops to deep valleys and river banks, but they always met our requests.

I remember one of my Corporals saying, 'Thank God for the RAF' as a Dakota disappeared towards the west after a drop, when another of my lads said, 'Yes, but in a couple of hours those so and so's will be able to have a nice cold shower and a hot meal.' The first man replied, 'They have more than earned it, I only hope that someday I can thank them.'

During the planning stages for the second Chindit expedition, General Wingate looked to employ air supply and casualty recovery to a far greater degree than in 1943. The jungle clearing at Sonpu was chosen as one of the two initial landing areas for his second invasion force in early March 1944 and given the codename 'Piccadilly.'

"Boy was I afraid; when I looked across at the pilot after we had cleared the trees, there was a pool of sweat in his lap. Was I glad to see the tops of those trees go by!"

Michael Vlasto was awarded an immediate Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for his actions on the 28th April 1943, but probably more importantly had proved that air rescue was possible behind enemy lines in Burma. Many years after the war, 8 Column Commander, Major Walter Purcell Scott recalled the 'Piccadilly' incident at a reunion with the RAF personnel of 31 Squadron:

'Plane Land Here Now' was the request that 31 Squadron so nobly answered. This air rescue undoubtedly pioneered the air evacuation of the wounded and sick from deep inside Burma during our second Chindit campaign in 1944. It also set the pattern for all future campaigns in that theatre of war.

Before General Wingate left for Quebec and the Allied Conference held there, he told me that the air rescue carried out by 31 Squadron was an acorn, and that one day I would see it grow into an oak tree. He kept his word, and from then on air recovery of the sick and wounded took place all over South East Asia.

The inspired attempts of Lummie Lord and his crew and the final magnificent effort of Mike Vlasto and his crew, set the seal on the outstanding performance of 31 Squadron, who throughout our campaign supplied all our needs, even when we were beyond the Irrawaddy and in frightful weather and flying conditions. At times we gave the squadron some frightful dropping areas, varying from mountain tops to deep valleys and river banks, but they always met our requests.

I remember one of my Corporals saying, 'Thank God for the RAF' as a Dakota disappeared towards the west after a drop, when another of my lads said, 'Yes, but in a couple of hours those so and so's will be able to have a nice cold shower and a hot meal.' The first man replied, 'They have more than earned it, I only hope that someday I can thank them.'

During the planning stages for the second Chindit expedition, General Wingate looked to employ air supply and casualty recovery to a far greater degree than in 1943. The jungle clearing at Sonpu was chosen as one of the two initial landing areas for his second invasion force in early March 1944 and given the codename 'Piccadilly.'

As far as I can ascertain, Michael Vlasto attained the rank of Wing Commander during his time with the RAF and was awarded a bar to his DFC later on in the war. He was also Mentioned in Despatches on one further occasion. In 1962 he married Margaret Mancor and the couple had one son, John Michael Vlasto who was born in 1964. Michael sadly died on the 7th June 1997 in the village of Pen Selwood, located close to Wincanton in Somerset.

Seen below is one final gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Seen below is one final gallery of images in relation to this story, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

For a more detailed account of the Dakota landing at Sonpu and the Chindits who were involved, please click on the following link:

The Piccadilly Incident

Copyright © Steve Fogden, January 2016.

The Piccadilly Incident

Copyright © Steve Fogden, January 2016.