Captain Norman Fraser Stocks RAMC

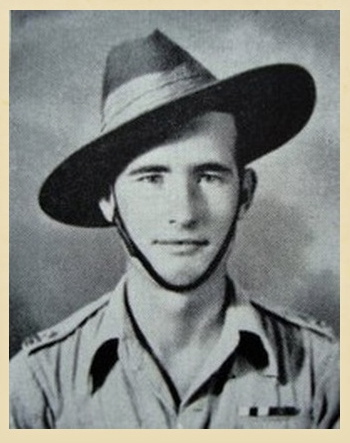

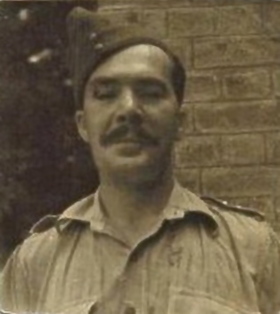

Norman Fraser Stocks, before Operation Longcloth.

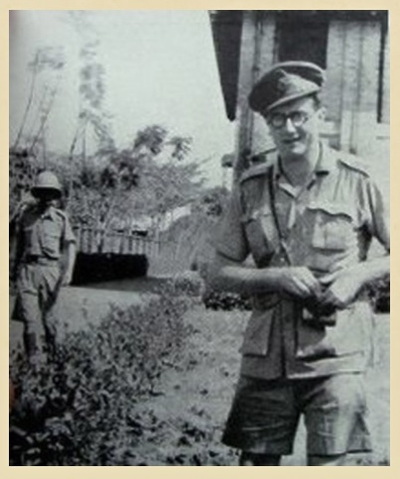

Norman Fraser Stocks, before Operation Longcloth.

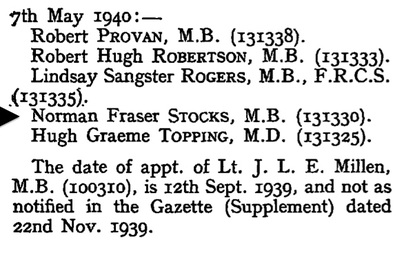

Norman Fraser Stocks was born on the 22nd May 1913 in the Scottish capital of Edinburgh. His family lived at 4 Priestfield Road, Edinburgh and Norman was educated at George Watson's College situated in the Merchiston area of the city. He was commissioned into the Royal Army Medical Corps on the 7th May 1940 with the Army Service number 131335.

In 1941-42, Norman served as Senior Medical Officer in Brigadier Jock Campbell's unit in the Western Desert, this included taking part in Operation Crusader. Later in 1942 he was posted to Saugor in India, where he joined Chindit training for the first Wingate expedition.

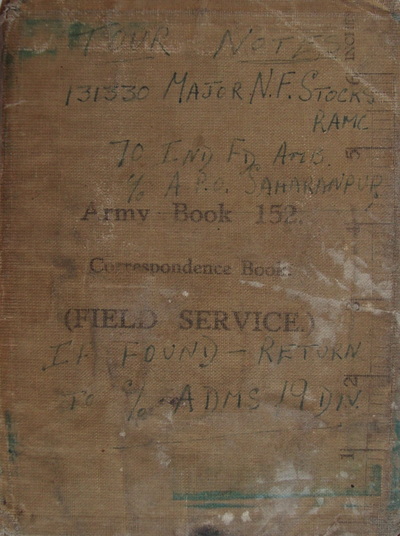

According to his Army Field Service Book, Norman also served as a Senior Medical Officer on the second Chindit expedition in 1944, followed by Chief Instructor to the Medical Branch Tactical School at Poona. At some point during his service in India he worked with 70 Indian Field Ambulance, which formed part of the 39th Indian Infantry Division.

Captain Stocks was attached to 142 Commando at Saugor, presumably acting as the Medical Officer for this unit in the months leading up to the commencement of Operation Longcloth. There is documentary evidence of his involvement with the commandos in the form of an inquiry into the death of Lance Corporal Percy Finch, a soldier training with 1 Column in 1942.

On Christmas Eve 1942, Percy Finch was accidentally killed in an incident involving the mis-use of explosives at the temporary training camp at Jhansi. Captain Stocks attended the casualties at the scene, including Finch and was now asked to give evidence at the Court of Inquiry held on the 26th December. He gave this account to the court:

On 24th December 1942 at about 22:00 hours, I was at Brigade Headquarters when several soldiers came in and asked me to attend a casualty in the column lines. They said that he'd had an accident with some gelignite.

I found the casualty, Lance Cpl. Finch lying outside a tent with a blanket over him. On a brief examination I found multiple injuries the worst being the right hand severed, and a large gaping wound in the chest and abdomen. I put on more blankets and went for a stretcher and morphia of which I injected half a grain. He was in severe shock, but conscious. I went with him in a truck to the British Military Hospital at Jhansi, where he was taken to the operating theatre. The O/C of the Hospital and the Duty Officer treated him, but he died 20 minutes after admission.

Further examination had revealed the extent of the injuries.

1. Gross ragged wound in the mid-line, penetrating chest and abdominal cavities, Viscua (organs) were protruding.

2. Traumatic amputation of the right wrist and hand and massive loss of tissue to the right fore-arm.

3. Numerous small lacerations of the head and face.

In my opinion, cause of death was surgical shock due to the above mentioned injuries.

To read more about the death of Lance Corporal Finch, please click on the following link: L/Cpl. Percy Finch

On the 6th January 1943, the Chindit Brigade boarded a succession of special trains at Jhansi in preparation for their journey up to Dimapur in Assam. Some personnel from 1 Column under the temporary command of Brigade-Major G. Menzies-Anderson were loaded on to train SA 5 at Jhansi, included amongst the passengers on this train were Captain Stocks and Animal Transport Officer, Lieutenant John Fowler. In a rather amusing movement order written for the transfer of the Brigade, it was stated that officers must be prepared to travel in 2nd or even 3rd Class carriages for the duration of the journey, as there was a severe shortage of 1st Class accommodation available.

From Dimapur, the Brigade marched along the Manipur Road towards Imphal. They marched only at night in order to allow normal Army traffic to use the road during daylight hours, but also to keep their presence and direction of travel as secretive as they possibly could. After reaching Imphal 77th Brigade assembled for the very last time as one unit, before setting off for the Chindwin River by column formation and crossing into Burma.

Captain Stocks became the Medical Officer for 1 Column on Operation Longcloth, under the command of Major George Dunlop, formerly of the Royal Scots Regiment. This was a predominately Gurkha column and formed part of Southern Group in 1943, along with 2 Column and Southern Group Head Quarters. The true role of Southern Group which was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel L.A. Alexander, was to act as a decoy for the other Chindit columns operating slightly to the north, by marching more openly through the tracks and pathways of the Burmese jungle and drawing attention to themselves and their activities.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

In 1941-42, Norman served as Senior Medical Officer in Brigadier Jock Campbell's unit in the Western Desert, this included taking part in Operation Crusader. Later in 1942 he was posted to Saugor in India, where he joined Chindit training for the first Wingate expedition.

According to his Army Field Service Book, Norman also served as a Senior Medical Officer on the second Chindit expedition in 1944, followed by Chief Instructor to the Medical Branch Tactical School at Poona. At some point during his service in India he worked with 70 Indian Field Ambulance, which formed part of the 39th Indian Infantry Division.

Captain Stocks was attached to 142 Commando at Saugor, presumably acting as the Medical Officer for this unit in the months leading up to the commencement of Operation Longcloth. There is documentary evidence of his involvement with the commandos in the form of an inquiry into the death of Lance Corporal Percy Finch, a soldier training with 1 Column in 1942.

On Christmas Eve 1942, Percy Finch was accidentally killed in an incident involving the mis-use of explosives at the temporary training camp at Jhansi. Captain Stocks attended the casualties at the scene, including Finch and was now asked to give evidence at the Court of Inquiry held on the 26th December. He gave this account to the court:

On 24th December 1942 at about 22:00 hours, I was at Brigade Headquarters when several soldiers came in and asked me to attend a casualty in the column lines. They said that he'd had an accident with some gelignite.

I found the casualty, Lance Cpl. Finch lying outside a tent with a blanket over him. On a brief examination I found multiple injuries the worst being the right hand severed, and a large gaping wound in the chest and abdomen. I put on more blankets and went for a stretcher and morphia of which I injected half a grain. He was in severe shock, but conscious. I went with him in a truck to the British Military Hospital at Jhansi, where he was taken to the operating theatre. The O/C of the Hospital and the Duty Officer treated him, but he died 20 minutes after admission.

Further examination had revealed the extent of the injuries.

1. Gross ragged wound in the mid-line, penetrating chest and abdominal cavities, Viscua (organs) were protruding.

2. Traumatic amputation of the right wrist and hand and massive loss of tissue to the right fore-arm.

3. Numerous small lacerations of the head and face.

In my opinion, cause of death was surgical shock due to the above mentioned injuries.

To read more about the death of Lance Corporal Finch, please click on the following link: L/Cpl. Percy Finch

On the 6th January 1943, the Chindit Brigade boarded a succession of special trains at Jhansi in preparation for their journey up to Dimapur in Assam. Some personnel from 1 Column under the temporary command of Brigade-Major G. Menzies-Anderson were loaded on to train SA 5 at Jhansi, included amongst the passengers on this train were Captain Stocks and Animal Transport Officer, Lieutenant John Fowler. In a rather amusing movement order written for the transfer of the Brigade, it was stated that officers must be prepared to travel in 2nd or even 3rd Class carriages for the duration of the journey, as there was a severe shortage of 1st Class accommodation available.

From Dimapur, the Brigade marched along the Manipur Road towards Imphal. They marched only at night in order to allow normal Army traffic to use the road during daylight hours, but also to keep their presence and direction of travel as secretive as they possibly could. After reaching Imphal 77th Brigade assembled for the very last time as one unit, before setting off for the Chindwin River by column formation and crossing into Burma.

Captain Stocks became the Medical Officer for 1 Column on Operation Longcloth, under the command of Major George Dunlop, formerly of the Royal Scots Regiment. This was a predominately Gurkha column and formed part of Southern Group in 1943, along with 2 Column and Southern Group Head Quarters. The true role of Southern Group which was commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel L.A. Alexander, was to act as a decoy for the other Chindit columns operating slightly to the north, by marching more openly through the tracks and pathways of the Burmese jungle and drawing attention to themselves and their activities.

Seen below is a gallery of images in relation to the first part of this story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

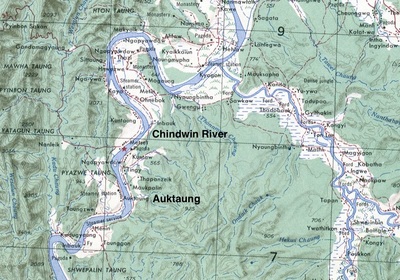

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktaung. Their orders were to march toward their own prime target, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. This supplementary unit were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their own objectives.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Dunlop was given the order to blow up the railway bridge and separated from the main body, whilst Column 2 under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Group HQ moved on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also now lost radio contact. Column 2 and Group Head Quarters in the black of night stumbled into an enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment. Here is how Lieutenant Ian MacHorton recalls that moment from the pages of his book, 'Safer Than a Known Way' :

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel".

Colonel Alexander managed to extract the majority of his Head Quarters from the chaos and devastation at Kyaikthin, he decided to lead them away to the agreed rendezvous point a few miles further east. His decision to keep to the pre-operational plan and move on toward the Irrawaddy River clearly showed his determination to carry out Wingate's orders and to test the theories of dispersal under enemy fire.

Within a few days (about the 7th March) Group Head Quarters with the survivors from Column 2 had met up once more with George Dunlop and his men. Together they crossed the Irrawaddy River. Southern Group now found themselves the most easterly placed Chindit unit and by that very nature the furthest from the safety of India. All remaining Chindit columns were now over the Irrawaddy and operating in a natural box contained on three sides by the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers and to the south by the Mongmit-Myitson Road, the force was effectively trapped and slowly the Japanese began to close in.

Important information about the contribution made by Captain Stocks on Operation Longcloth can be found in MacHorton's book. During another violent battle with the Japanese, at a place called Loi Sau just south of the town of Mongmit, Ian MacHorton was injured by mortar shrapnel and Colonel Alexander had to make the agonising decision to leave him by the track side. Norman Stocks treated MacHorton's wound at the scene and made him as comfortable as possible.

From 'Safer Than a Known Way' :

Jap bullets still whined and buzzed. Mortar bombs crashed beyond and around the rocks behind us. But behind the big boulder where we lay was a haven indeed. Still gasping for breath, Kulbahadur unfastened my belt and tugged my trousers down to expose my hip and thigh, which were now a mass of blood. It was pulsing out from an ugly wound where a long thin mortar splinter had cut into flesh and muscle a few inches below the hip joint.

Havildar Lalbahadur, seeing that I was now safe from immediate danger and that Kulbahadur was treating my wound, hurled himself out bent double from the shelter of the boulder to take over my place in command of the platoon. A yard short of the boulder to which he was running, to carry on controlling the fight, he suddenly straightened out like a puppet on violently tugged strings. Without a cry he plunged forward, bounced when he hit the ground, jerked spasmodically, and lay still.

I closed my eyes, not only because of the sudden onrush of pain from my wound. Tough, always smiling, Havildar Lalbahadur had been one of the sure things in life. He had strength and skill-at-arms and ardent courage. He was also a faithful friend.

Across the boulder-strewn hillside Captain Stocks, R.A.M.C., our Column Medical Officer, leaped into sight ducking and weaving through the no-man's-land of grenade bursts and zipping bullets. His red-cross haversack was bouncing on his hip as he ran. How he managed to get through that hail of fire unscathed, I never knew. Next moment he had reached my boulder and flung himself down beside me. He was feeling my thigh bone with one hand and my hip joint with the other.

"It's a mortar splinter," he gasped, breathless from his dash. "It's still in there. Can you move your leg?"

I tried, but pain in a searing fire swept through me and a cold sweat stood out on my brow.

"I can't, Doc, I can't," I groaned. "Where's your morphia?" he bellowed. This I heard.

In my shocked weakness I could not even reply. But Kulbahadur rummaged in my pack and withdrew a phial. Captain Stocks ripped off the top, exposing the sterilised needle. He jabbed it into my arm and squeezed. The pulsing of blood in my ears increased to a roaring that overwhelmed even the noise of battle. I was swallowed up in a red-black cloud of unconsciousness.

After treating Lieutenant MacHorton and finding a quiet and at least temporarily safe place to leave him, Captain Stocks, Colonel Alexander and the rest of the Southern Group Chindits moved away from Loi Sau to the north-east. Incredibly, Ian MacHorton survived Operation Longcloth, returning to India in spite of the crippling wound to his leg.

From that moment onwards, Major Dunlop and Colonel Alexander shared most of the decision making for their stricken Chindit column. After eventually deciding to return west to India rather than try for the safety of Yunnan Province in China, the group suffered a long and arduous journey home, including having to re-cross both the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. Over the coming weeks the column lost many men, some after sharp engagements with the enemy, but the majority simply due to thirst, starvation and total exhaustion. It must be presumed therefore, that Captain Stocks was kept extremely busy during these gruelling days on the march.

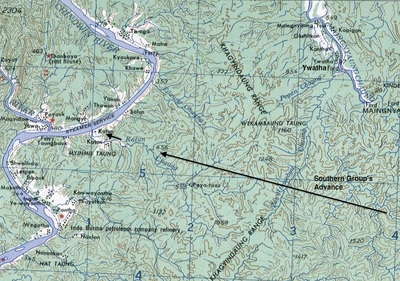

Shown below is a map of the area around Loi Sau, the location where Lieutenant MacHorton was injured. Loi Sau is translated into English as 'Old Baldy' which refers to the featureless hill that sits above the village.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin, Dunlop was given the order to blow up the railway bridge and separated from the main body, whilst Column 2 under the command of Major Arthur Emmett along with Group HQ moved on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also now lost radio contact. Column 2 and Group Head Quarters in the black of night stumbled into an enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment. Here is how Lieutenant Ian MacHorton recalls that moment from the pages of his book, 'Safer Than a Known Way' :

"We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel".

Colonel Alexander managed to extract the majority of his Head Quarters from the chaos and devastation at Kyaikthin, he decided to lead them away to the agreed rendezvous point a few miles further east. His decision to keep to the pre-operational plan and move on toward the Irrawaddy River clearly showed his determination to carry out Wingate's orders and to test the theories of dispersal under enemy fire.

Within a few days (about the 7th March) Group Head Quarters with the survivors from Column 2 had met up once more with George Dunlop and his men. Together they crossed the Irrawaddy River. Southern Group now found themselves the most easterly placed Chindit unit and by that very nature the furthest from the safety of India. All remaining Chindit columns were now over the Irrawaddy and operating in a natural box contained on three sides by the Shweli and Irrawaddy Rivers and to the south by the Mongmit-Myitson Road, the force was effectively trapped and slowly the Japanese began to close in.

Important information about the contribution made by Captain Stocks on Operation Longcloth can be found in MacHorton's book. During another violent battle with the Japanese, at a place called Loi Sau just south of the town of Mongmit, Ian MacHorton was injured by mortar shrapnel and Colonel Alexander had to make the agonising decision to leave him by the track side. Norman Stocks treated MacHorton's wound at the scene and made him as comfortable as possible.

From 'Safer Than a Known Way' :

Jap bullets still whined and buzzed. Mortar bombs crashed beyond and around the rocks behind us. But behind the big boulder where we lay was a haven indeed. Still gasping for breath, Kulbahadur unfastened my belt and tugged my trousers down to expose my hip and thigh, which were now a mass of blood. It was pulsing out from an ugly wound where a long thin mortar splinter had cut into flesh and muscle a few inches below the hip joint.

Havildar Lalbahadur, seeing that I was now safe from immediate danger and that Kulbahadur was treating my wound, hurled himself out bent double from the shelter of the boulder to take over my place in command of the platoon. A yard short of the boulder to which he was running, to carry on controlling the fight, he suddenly straightened out like a puppet on violently tugged strings. Without a cry he plunged forward, bounced when he hit the ground, jerked spasmodically, and lay still.

I closed my eyes, not only because of the sudden onrush of pain from my wound. Tough, always smiling, Havildar Lalbahadur had been one of the sure things in life. He had strength and skill-at-arms and ardent courage. He was also a faithful friend.

Across the boulder-strewn hillside Captain Stocks, R.A.M.C., our Column Medical Officer, leaped into sight ducking and weaving through the no-man's-land of grenade bursts and zipping bullets. His red-cross haversack was bouncing on his hip as he ran. How he managed to get through that hail of fire unscathed, I never knew. Next moment he had reached my boulder and flung himself down beside me. He was feeling my thigh bone with one hand and my hip joint with the other.

"It's a mortar splinter," he gasped, breathless from his dash. "It's still in there. Can you move your leg?"

I tried, but pain in a searing fire swept through me and a cold sweat stood out on my brow.

"I can't, Doc, I can't," I groaned. "Where's your morphia?" he bellowed. This I heard.

In my shocked weakness I could not even reply. But Kulbahadur rummaged in my pack and withdrew a phial. Captain Stocks ripped off the top, exposing the sterilised needle. He jabbed it into my arm and squeezed. The pulsing of blood in my ears increased to a roaring that overwhelmed even the noise of battle. I was swallowed up in a red-black cloud of unconsciousness.

After treating Lieutenant MacHorton and finding a quiet and at least temporarily safe place to leave him, Captain Stocks, Colonel Alexander and the rest of the Southern Group Chindits moved away from Loi Sau to the north-east. Incredibly, Ian MacHorton survived Operation Longcloth, returning to India in spite of the crippling wound to his leg.

From that moment onwards, Major Dunlop and Colonel Alexander shared most of the decision making for their stricken Chindit column. After eventually deciding to return west to India rather than try for the safety of Yunnan Province in China, the group suffered a long and arduous journey home, including having to re-cross both the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. Over the coming weeks the column lost many men, some after sharp engagements with the enemy, but the majority simply due to thirst, starvation and total exhaustion. It must be presumed therefore, that Captain Stocks was kept extremely busy during these gruelling days on the march.

Shown below is a map of the area around Loi Sau, the location where Lieutenant MacHorton was injured. Loi Sau is translated into English as 'Old Baldy' which refers to the featureless hill that sits above the village.

After finally crossing the Shweli River the men of Southern Group marched once more for that seemingly insurmountable obstacle, the Irrawaddy. Major Dunlop suggests in his diary, that the group reached the great river just south of the town of Sinhnyat on the eastern bank on approximately the 20th April, although he also states that due to the physical condition of himself and his men, many of the passing days had seemingly rolled into one. The Chindits gathered just outside of the town and organised their passage across the river. It is mentioned in MacHorton's book, that the Medical Officer for 2 Column, Captain George Lusk was also present at Sinhnyat, so hopefully the medical requirements of the men were being shared between the two Doctors at that time.

The ferrying of the Chindits across the Irrawaddy was almost complete, when disastrously, another enemy ambush occurred. The final few boats of the convoy were fired upon by Japanese machine guns and mortars, resulting in many casualties. It was at this time that Doc' Lusk was last seen alive, although rumour has it that he was actually taken prisoner at the Irrawaddy and died a few days later whilst in Japanese hands. In all the chaos and confusion at the Irrawaddy, many of the men had become separated from the main body, which was now commanded by Major Dunlop. It was reported that Captain Stocks led a small group of twenty or so Gurkhas away from the western bank and headed in a southerly direction.

By early May, Dunlop's group had reached the approaches to the Chindwin Valley and were searching for food in some of the local villages in that area. Captain Stocks and his party had re-joined at some point previously and the doctor was now travelling alongside his old comrades from 142 Commando. Lieutenant Nealon took a section of his Commandos away in an attempt to find food in the village of Ywatha. Shortly after this time, the main column were threatened by a group of Burmese Militia, then not long afterwards near a small stream called the Katun Chaung, the Chindits were attacked by a large Japanese patrol. Once again the men scattered in all directions, with the majority of the Commandos, along with Major Dunlop moving quickly away in the direction of the nearby hills.

From his own diary written after the operation, George Dunlop remembers the incident at Katun Chaung:

That evening Nealon (by this time the commander of the Commando Platoon) asked if he might try his luck at getting food at Ywatha, as his British troops could not go on without it. The remnants of my command being somewhat pathetic, I said yes, thinking that they might at least have a chance. He set off with his party and an hour later we heard a fight at the village, very short and sharp.

There followed more days of hunger and climbing those infernal hills. One night all the mule Jemadar's party disappeared, leaving me with the doctor Captain Stocks, Lts. Clarke, Fowler, MacHorton, the No. 2 Guerrilla Platoon Officer, two Signallers and three or four Gurkhas, including my clerk who could speak both English and Burmese.

Eventually we killed a buffalo on the Katun Chaung. While cutting it up we were approached by a party of Burmans armed with rifles and war dahs. They told us that no Japanese were about, but, as we heard mortar fire earlier on from the direction of the Chindwin, I did not believe them. We disarmed them and they fled up a spur. The clerk wanted to go with them but we stopped him. Much shouting followed and I guessed that their Japanese masters were up there. I gave the order to scatter from the open paddy.

It was at Katun Chaung that Captain Stocks was once again separated from Column Commander George Dunlop. However, another short quote from Dunlop's diary explains what eventually happened to his Medical Officer:

I eventually learned the fate of some of the men; Burma Rifles Officer Chit Kyin had passed through with 250 men having got boats to cross the Chindwin. Stocks and the other British Officer had gone through too. They had had incredible luck. They walked into Katun. The Japanese took post in the perimeter of the village as they walked down the waters edge. There they found a villager who ferried them to Yuwa.

After reaching the relative safety of the western banks of the Chindwin River, most Chindits were moved quickly up to Tamu and then to Imphal, where they were admitted to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station, run by Senior Matron Agnes McGeary. It was here that they began to recuperate and received treatment for the ailments and maladies acquired from their trials in the Burmese jungle. Norman Stocks arrived at Imphal in early June 1943 (see photograph in the gallery below), by which time he had lost a lot of weight and was extremely grateful to receive such excellent care from Nurse McGeary and her team.

As mentioned earlier in this story, Captain Stocks was involved with the second Wingate expedition in 1944 and according to the front cover of his Field Service Book, also worked within the ADMS (Assistant Director Medical Service) for the 19th Infantry Division (India), known as the Daggers in reference to their Divisional insignia. The 19th Infantry Division, commanded by Major-General Thomas Wynford Rees had taken a major role in the defence of the Imphal plain during the autumn of 1944 and then began to clear the way for the re-invasion of Burma by the 14th Army, including the capture of Mandalay. By the end of the war, Norman Stocks had risen to the rank of Major and it was with this rank that he ultimately left the Army.

Seen below are some more images in relation to the story of Captain Norman Stocks. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The ferrying of the Chindits across the Irrawaddy was almost complete, when disastrously, another enemy ambush occurred. The final few boats of the convoy were fired upon by Japanese machine guns and mortars, resulting in many casualties. It was at this time that Doc' Lusk was last seen alive, although rumour has it that he was actually taken prisoner at the Irrawaddy and died a few days later whilst in Japanese hands. In all the chaos and confusion at the Irrawaddy, many of the men had become separated from the main body, which was now commanded by Major Dunlop. It was reported that Captain Stocks led a small group of twenty or so Gurkhas away from the western bank and headed in a southerly direction.

By early May, Dunlop's group had reached the approaches to the Chindwin Valley and were searching for food in some of the local villages in that area. Captain Stocks and his party had re-joined at some point previously and the doctor was now travelling alongside his old comrades from 142 Commando. Lieutenant Nealon took a section of his Commandos away in an attempt to find food in the village of Ywatha. Shortly after this time, the main column were threatened by a group of Burmese Militia, then not long afterwards near a small stream called the Katun Chaung, the Chindits were attacked by a large Japanese patrol. Once again the men scattered in all directions, with the majority of the Commandos, along with Major Dunlop moving quickly away in the direction of the nearby hills.

From his own diary written after the operation, George Dunlop remembers the incident at Katun Chaung:

That evening Nealon (by this time the commander of the Commando Platoon) asked if he might try his luck at getting food at Ywatha, as his British troops could not go on without it. The remnants of my command being somewhat pathetic, I said yes, thinking that they might at least have a chance. He set off with his party and an hour later we heard a fight at the village, very short and sharp.

There followed more days of hunger and climbing those infernal hills. One night all the mule Jemadar's party disappeared, leaving me with the doctor Captain Stocks, Lts. Clarke, Fowler, MacHorton, the No. 2 Guerrilla Platoon Officer, two Signallers and three or four Gurkhas, including my clerk who could speak both English and Burmese.

Eventually we killed a buffalo on the Katun Chaung. While cutting it up we were approached by a party of Burmans armed with rifles and war dahs. They told us that no Japanese were about, but, as we heard mortar fire earlier on from the direction of the Chindwin, I did not believe them. We disarmed them and they fled up a spur. The clerk wanted to go with them but we stopped him. Much shouting followed and I guessed that their Japanese masters were up there. I gave the order to scatter from the open paddy.

It was at Katun Chaung that Captain Stocks was once again separated from Column Commander George Dunlop. However, another short quote from Dunlop's diary explains what eventually happened to his Medical Officer:

I eventually learned the fate of some of the men; Burma Rifles Officer Chit Kyin had passed through with 250 men having got boats to cross the Chindwin. Stocks and the other British Officer had gone through too. They had had incredible luck. They walked into Katun. The Japanese took post in the perimeter of the village as they walked down the waters edge. There they found a villager who ferried them to Yuwa.

After reaching the relative safety of the western banks of the Chindwin River, most Chindits were moved quickly up to Tamu and then to Imphal, where they were admitted to the 19th Casualty Clearing Station, run by Senior Matron Agnes McGeary. It was here that they began to recuperate and received treatment for the ailments and maladies acquired from their trials in the Burmese jungle. Norman Stocks arrived at Imphal in early June 1943 (see photograph in the gallery below), by which time he had lost a lot of weight and was extremely grateful to receive such excellent care from Nurse McGeary and her team.

As mentioned earlier in this story, Captain Stocks was involved with the second Wingate expedition in 1944 and according to the front cover of his Field Service Book, also worked within the ADMS (Assistant Director Medical Service) for the 19th Infantry Division (India), known as the Daggers in reference to their Divisional insignia. The 19th Infantry Division, commanded by Major-General Thomas Wynford Rees had taken a major role in the defence of the Imphal plain during the autumn of 1944 and then began to clear the way for the re-invasion of Burma by the 14th Army, including the capture of Mandalay. By the end of the war, Norman Stocks had risen to the rank of Major and it was with this rank that he ultimately left the Army.

Seen below are some more images in relation to the story of Captain Norman Stocks. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

After the war, Norman set up as a General Practitioner in a surgery in Gateshead, County Durham. He then moved down to London in the 1960's, living in the Borough of Islington for a number of years. Norman Stocks sadly passed away aged just 57, on the 11th September 1970 at the King's Mill Hospital, Sutton-in-Ashfield in the county of Nottinghamshire.

I would like to thank Jim Stocks, Norman's only son, for his invaluable assistance in providing information and photographs in relation to his father's experiences during WW2.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, March 2016.

I would like to thank Jim Stocks, Norman's only son, for his invaluable assistance in providing information and photographs in relation to his father's experiences during WW2.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, March 2016.