Pre-Operational Reconnaissance

In early December 1942 Wingate began to form up several reconnaissance parties from his fledgling Chindit Brigade. He realised that before he sent his entire unit over the border into Burma, he ought to secure more current information about the lie of the land, the movements of the enemy in that area and that certain crucial elements of his tactical planning, air supply for instance, were feasible.

Just prior to the main Brigade's crossing of the Chindwin River in February 1943, Wingate had sent forward a party consisting of Lieut.-Col. Wheeler of the Burma Rifles and three of the RAF Air Liaison Officers from his Chindit columns. Flight Officers Robert Thompson, Denny Sharp and John Fleming Gibson had all accompanied Colonel Wheeler on this mission, in order to choose both a suitable crossing point for Northern Group and the potential location of at least the first scheduled air supply drop. For the latter they decided upon the area around the village of Tonmakeng.

However, there had been other reconnaissance parties long before this one. In early December 1942, Major Gilmour Menzies Anderson was tasked to form up a small section of British troops to accompany Captain Denis Clive Herring, known unsurprisingly as 'Fish' to his comrades, on another, more extensive foray into the jungle area just beyond the east banks of the Chindwin River.

Chosen to be part of this team were: Sgt. Tony Aubrey, a survivor of the Dunkirk disaster in 1940, Lance Corporal Tommy Vann, a stoically reliable soldier with witty sense of humour, and Pte. Stanley Allnutt, chosen one would imagine for his knowledge of the Burmese language, an unusual attribute for a British soldier at that time.

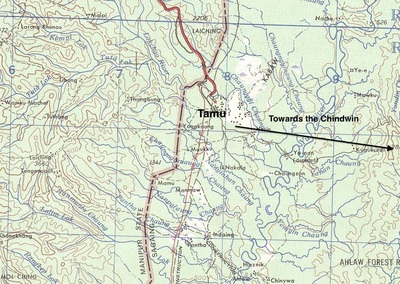

The group moved quickly across from the training centre at Saugor to the town of Imphal, they were then transported by an old three-ton Bedford truck along the tortuous and twisting hillside roads to Tamu, which lies close to the official land border with Burma. I will let Tony Aubrey take up the story at this point:

Our numbers were now much smaller than the original party, as Lieutenant Bruce had left us to strike out on his own at Imphal, taking with him all the Burmese, except for six. But we had been reinforced by the addition of two mules and their Punjabi Mussulmen muleteers. Our first halt was at Tamu, seventeen miles farther up the track.

This had been, in the days of peace, an elephant station belonging to the company of which Captain Herring had been an employee. He was the ideal man for the sort of job we had in hand, for he had been in Burma for a good many years, spoke the language like a native, and knew intimately the country through which we would travel. Also, he had been a Territorial Officer in the Burma Rifles, and had fought against the Japanese in the retreat. He didn't like them at all, but he did love the Burmese.

He was as pleased as a child with a new toy at having been given this chance of getting a bit of his own back. I don't actually know, of course, what orders he had been given about this reconnaissance, but I imagine they had simply said to him, "Get across the Chindwin River and find out all you can. Oh, and by the way, be back by the first of January, will you?"

That date was the limit set on the duration of our trip. An old friend of Captain Herring's named Mr.Thomas, was in charge of the elephant station at Tamu. The Japs had paid him a visit but had done him no physical harm, as they used him as an intermediary between themselves and the Burmese. But he had had in his charge fifty of the Company's elephants, and the Japanese tried to take away every one of these.

However, the few mahouts (elephant drivers) and their wives who had disdained to run away on the approach of the enemy, followed them when they had gone, and succeeded in regaining possession of seventeen of their animals. These seventeen were still in the station, and when we went ahead the next day we took one of them, and his mahout, Nandaw, with us in place of the two mules, which were returned with their drivers to Imphal.

So when we left on the final stage of our march to the Chindwin our party was ten strong, Captain Herring, myself, Vann and Allnutt, and the six men of the Burmese Rifles, and with us went Nandaw and his elephant. The path was now very narrow, and passed through jungle denser than any I had ever seen before. Visibility was sometimes practically nil, and I was lost in amazement at the silent progress of the elephant, which manoeuvred its colossal bulk through the scrub with less fuss and commotion than that made by any of us.

I marvelled, too, at the speed and skill Nandaw showed in clearing overhanging branches out of his way with one sweep of his dha, and without ever checking the elephant's progress. Every now and again, along the edges of this ill-omened path, we came on traces of the retreat from Burma. Now, it would be a single corpse, or two or three together in a melancholy huddle. Now, it would be an old-fashioned motor bus, lonely and incongruous in its tropical surroundings; now, a motor car or a lorry, overturned and defeated by the narrowness of the way, some heaps of bones around it showing that its occupants had also given up the unequal struggle.

The distance from Tamu to the Chindwin River is forty-seven miles as the crow flies, but we took three days to cover it. While Nandaw and his elephant kept straight ahead down the path without escort, as we had had reliable information that there were none of the enemy this side of the river, the remainder of us made continual casts in parties to north and south of us, gathering information about water for animals, and places suitable for the resting and concealment of bodies of troops.

Sometimes when making these casts we came across old hutments, and then, in spite of our information, we approached them with every precaution, for the Jap is a crafty animal, and we were always on the lookout for booby traps and other pieces of devilment. We arrived at a spot three miles from the river on the evening of the third day, and here Captain Herring decided we should camp, for straight ahead of us on the river itself lay a large village, and he did not feel inclined to let our presence be known there until he had found out how the land lay.

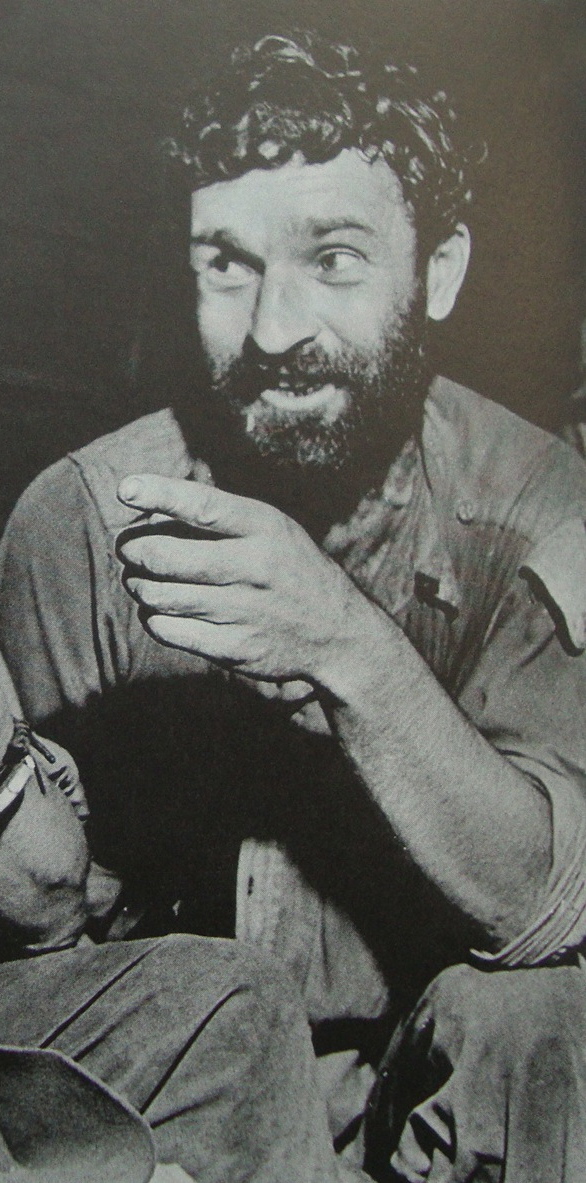

Seen below is a map of the area around the border town of Tamu and the general direction taken to the Chindwin River. Also seen is a map of the area around Tonmakeng, the location of the first Chindit supply drop, and a photograph of Sgt. Tony Aubrey from later on in 1943. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 27/06/2015. I have recently been contacted by the daughter of Sergeant Thomas Vann, who kindly sent me some photographs depicting his time in both India and Burma. Included below is a portrait photograph of Thomas in his Chindit slouch hat.

Just prior to the main Brigade's crossing of the Chindwin River in February 1943, Wingate had sent forward a party consisting of Lieut.-Col. Wheeler of the Burma Rifles and three of the RAF Air Liaison Officers from his Chindit columns. Flight Officers Robert Thompson, Denny Sharp and John Fleming Gibson had all accompanied Colonel Wheeler on this mission, in order to choose both a suitable crossing point for Northern Group and the potential location of at least the first scheduled air supply drop. For the latter they decided upon the area around the village of Tonmakeng.

However, there had been other reconnaissance parties long before this one. In early December 1942, Major Gilmour Menzies Anderson was tasked to form up a small section of British troops to accompany Captain Denis Clive Herring, known unsurprisingly as 'Fish' to his comrades, on another, more extensive foray into the jungle area just beyond the east banks of the Chindwin River.

Chosen to be part of this team were: Sgt. Tony Aubrey, a survivor of the Dunkirk disaster in 1940, Lance Corporal Tommy Vann, a stoically reliable soldier with witty sense of humour, and Pte. Stanley Allnutt, chosen one would imagine for his knowledge of the Burmese language, an unusual attribute for a British soldier at that time.

The group moved quickly across from the training centre at Saugor to the town of Imphal, they were then transported by an old three-ton Bedford truck along the tortuous and twisting hillside roads to Tamu, which lies close to the official land border with Burma. I will let Tony Aubrey take up the story at this point:

Our numbers were now much smaller than the original party, as Lieutenant Bruce had left us to strike out on his own at Imphal, taking with him all the Burmese, except for six. But we had been reinforced by the addition of two mules and their Punjabi Mussulmen muleteers. Our first halt was at Tamu, seventeen miles farther up the track.

This had been, in the days of peace, an elephant station belonging to the company of which Captain Herring had been an employee. He was the ideal man for the sort of job we had in hand, for he had been in Burma for a good many years, spoke the language like a native, and knew intimately the country through which we would travel. Also, he had been a Territorial Officer in the Burma Rifles, and had fought against the Japanese in the retreat. He didn't like them at all, but he did love the Burmese.

He was as pleased as a child with a new toy at having been given this chance of getting a bit of his own back. I don't actually know, of course, what orders he had been given about this reconnaissance, but I imagine they had simply said to him, "Get across the Chindwin River and find out all you can. Oh, and by the way, be back by the first of January, will you?"

That date was the limit set on the duration of our trip. An old friend of Captain Herring's named Mr.Thomas, was in charge of the elephant station at Tamu. The Japs had paid him a visit but had done him no physical harm, as they used him as an intermediary between themselves and the Burmese. But he had had in his charge fifty of the Company's elephants, and the Japanese tried to take away every one of these.

However, the few mahouts (elephant drivers) and their wives who had disdained to run away on the approach of the enemy, followed them when they had gone, and succeeded in regaining possession of seventeen of their animals. These seventeen were still in the station, and when we went ahead the next day we took one of them, and his mahout, Nandaw, with us in place of the two mules, which were returned with their drivers to Imphal.

So when we left on the final stage of our march to the Chindwin our party was ten strong, Captain Herring, myself, Vann and Allnutt, and the six men of the Burmese Rifles, and with us went Nandaw and his elephant. The path was now very narrow, and passed through jungle denser than any I had ever seen before. Visibility was sometimes practically nil, and I was lost in amazement at the silent progress of the elephant, which manoeuvred its colossal bulk through the scrub with less fuss and commotion than that made by any of us.

I marvelled, too, at the speed and skill Nandaw showed in clearing overhanging branches out of his way with one sweep of his dha, and without ever checking the elephant's progress. Every now and again, along the edges of this ill-omened path, we came on traces of the retreat from Burma. Now, it would be a single corpse, or two or three together in a melancholy huddle. Now, it would be an old-fashioned motor bus, lonely and incongruous in its tropical surroundings; now, a motor car or a lorry, overturned and defeated by the narrowness of the way, some heaps of bones around it showing that its occupants had also given up the unequal struggle.

The distance from Tamu to the Chindwin River is forty-seven miles as the crow flies, but we took three days to cover it. While Nandaw and his elephant kept straight ahead down the path without escort, as we had had reliable information that there were none of the enemy this side of the river, the remainder of us made continual casts in parties to north and south of us, gathering information about water for animals, and places suitable for the resting and concealment of bodies of troops.

Sometimes when making these casts we came across old hutments, and then, in spite of our information, we approached them with every precaution, for the Jap is a crafty animal, and we were always on the lookout for booby traps and other pieces of devilment. We arrived at a spot three miles from the river on the evening of the third day, and here Captain Herring decided we should camp, for straight ahead of us on the river itself lay a large village, and he did not feel inclined to let our presence be known there until he had found out how the land lay.

Seen below is a map of the area around the border town of Tamu and the general direction taken to the Chindwin River. Also seen is a map of the area around Tonmakeng, the location of the first Chindit supply drop, and a photograph of Sgt. Tony Aubrey from later on in 1943. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

Update 27/06/2015. I have recently been contacted by the daughter of Sergeant Thomas Vann, who kindly sent me some photographs depicting his time in both India and Burma. Included below is a portrait photograph of Thomas in his Chindit slouch hat.

The group led by Captain Herring moved across the Chindwin without incident and spent several days moving through the jungles on the eastern side of the river. They pushed on for about 60-80 miles taking their time to check on the morale and demeanour of the Burmese in the vicinity and evaluating whether these villagers might be prepared to assist Wingate's new force over the forthcoming weeks. After gathering this intelligence the party returned to Chindit HQ to report their findings.

None of these Chindit recce parties could have achieved anything much at all without the help of the Burma Rifles and some of the other 'stay behind' groups such as V Force and Z Force. In the case of Operation Longcloth, it was the unit, GSI (Z) that provided much of the intelligence gathered prior to the start of the expedition. After the retreat in early 1942, small groups of men were sent back into Burma and lived behind Japanese lines, checking on the enemy positions and cultivating good relations with the Burmese in those areas.

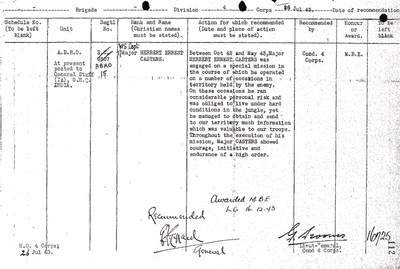

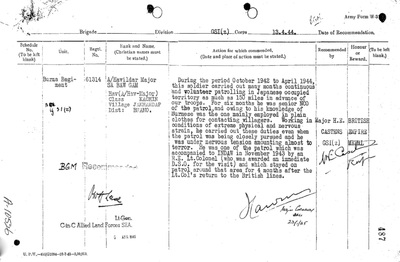

The Chindit operation in 1943 owed much to men such as Major Herbert Castens of GSI (Z) or Z Force as it was known. He had not only paved the way for the Chindit reconnaissance parties in late 1942, but had also informed Wingate of a secret track, which was used during the operation to bypass the Japanese garrisons stationed in the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment. Many of the men from Z Force and units just like them received recognition after the war for their brave and daring actions behind enemy lines. Without such men, the effectiveness of operations such as the first Chindit expedition would have been much reduced, with bodies of troops moving blindly through territories held by the enemy and never knowing what they might encounter next.

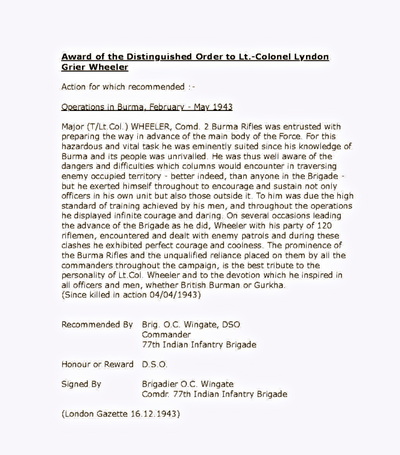

Seen below are some examples of award recommendations for men who had given support and intelligence in relation to Operation Longcloth. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

None of these Chindit recce parties could have achieved anything much at all without the help of the Burma Rifles and some of the other 'stay behind' groups such as V Force and Z Force. In the case of Operation Longcloth, it was the unit, GSI (Z) that provided much of the intelligence gathered prior to the start of the expedition. After the retreat in early 1942, small groups of men were sent back into Burma and lived behind Japanese lines, checking on the enemy positions and cultivating good relations with the Burmese in those areas.

The Chindit operation in 1943 owed much to men such as Major Herbert Castens of GSI (Z) or Z Force as it was known. He had not only paved the way for the Chindit reconnaissance parties in late 1942, but had also informed Wingate of a secret track, which was used during the operation to bypass the Japanese garrisons stationed in the Zibyu Taungdan Escarpment. Many of the men from Z Force and units just like them received recognition after the war for their brave and daring actions behind enemy lines. Without such men, the effectiveness of operations such as the first Chindit expedition would have been much reduced, with bodies of troops moving blindly through territories held by the enemy and never knowing what they might encounter next.

Seen below are some examples of award recommendations for men who had given support and intelligence in relation to Operation Longcloth. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, November 2014.