Pte. Bernard Keelan

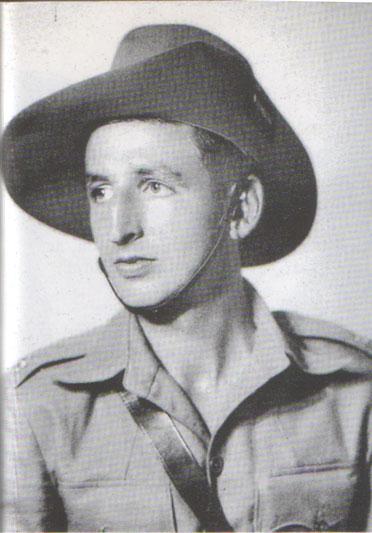

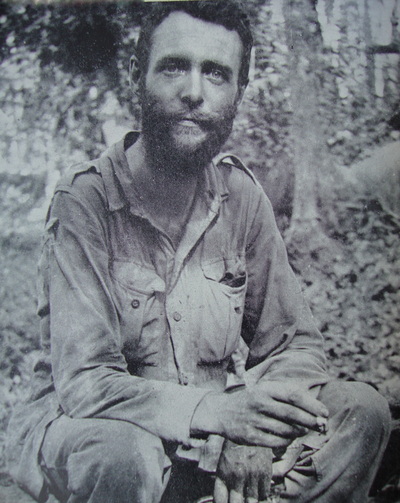

Bernard Keelan seen in 1940-41.

Bernard Keelan seen in 1940-41.

Pte. 3774986 Bernard Keelan enlisted in to the British Army when he was just 20 years old. He was a member of the 13th Battalion King's Liverpool Regiment that travelled overseas to India in December 1941. Bernard was allocated to Chindit Column 5 during training at the Saugor Camp in the Central Provinces of India. He became part of the Company Signals Section for the Column's Head Quarters.

None of this information was previously known to me. Like so many of the more fortunate men from the first Chindit Operation, those who had survived to return home after the war was over, Bernard's role in 1943 had so far eluded my research. His part in Operation Longcloth was brought to my attention by an email from his son, Brendan Keelan.

In his first email contact, dated 28th April 2014 Brendan had this to say about his father:

I found your website fairly recently and just wanted to add a bit of information about my father Bernard Keelan who was with 5 Column and was one of those few members of that group who made the trek into China.

I've recently seen a letter he sent from after the expedition which lists his details as 3774986 HQ Company Signals, 13th Bn King's Regiment.

As seems to be customary with these veterans, he shared some of his experiences with us, but not the horrors, and I never got him to commit his memories to paper before he died in 1993. I do recall some of the comments on individuals though. He was a great admirer of Bernard Fergusson and also told me that for the dispersal with Column 7, he was originally allocated to Lt. Campbell-Paterson's group with a plan to steal a river boat and sail down the Irrawaddy.

My Dad didn't think much of that idea and chose the march on into China instead. I'm sure he would have been glad to know Campbell-Paterson did at least manage to survive. He wasn't a great fan of Gilkes, recording that he had put a man on a charge even during the trek out. He mentioned some of his colleagues including an ex-Birkenhead bus conductor called Frank Townson, who was fluent in German and so obviously placed in the wrong theatre! Unfortunately he was one of those who didn't make it out.

As you can imagine I was delighted to receive this new information from Brendan and replied to his email immediately:

Dear Brendan,

Thank you for your email contact via my website. It is truly wonderful that you have taken the trouble to get in touch. I have not seen mention of your father, Bernard, before, which for me is very exciting. Discovering new members of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade is always exciting, but for him to be a member of Column 5 is an added bonus.

Bernard must of been a very fit and determined character to achieve the dispersal through the Yunnan Borders, especially coming as he did from Column 5, who as you will know, had the worst time of it in terms of rations and meeting the enemy in action.

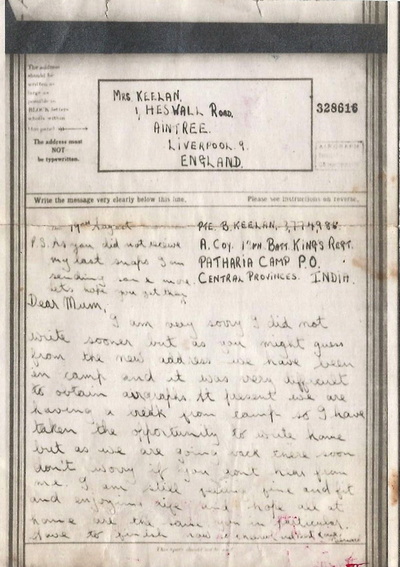

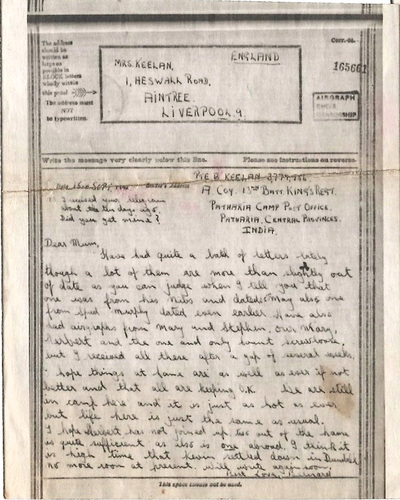

Brendan sent me a photograph of his father from early on in the war, probably 1940 or 1941, but certainly before the 13th King's left for India. He also shared two of Bernard's airgraph letters sent home during his time at the Chindit training camp in Patharia. These were addressed to Bernard's mother and like most correspondence home from those times were fairly light-hearted in content, discussing and enquiring about the health and happiness of various family members.

One thing the airgraphs did confirm for me was Bernard's placement in A' Company of the 13th King's, this matches perfectly with his eventual attachment to Chindit Column 5.

At the end of June 1942 the men from A' Company became the Infantry element for Chindit Column 5, the men from B' Company went over to Column 6, C' Company to Column 7 and D' Company made up the numbers for Column 8. Due to mis-fortune and a high degree of sickness Chindit Column 6 was disbanded in late December and the remaining personnel distributed amongst the other three units.

Bernard's placement with HQ Company Signals in Column 5 would almost certainly mean that he marched day in and day out close to his commander and namesake, Major Bernard Fergusson. Brendan also mentioned that his father had spoken about his friendship with a Gurkha soldier from those days in the Burmese jungle. He pronounced the Gurkha's name as 'Karakbader'. In Fergusson's Head Quarters there would have been two sets of Gurkhas present, the commander's own bodyguard platoon and then the muleteers for the Column radio equipment, perhaps Karakbader served with one of these units?

Seen below are the two Airgraphs sent home by Bernard Keelan to his mother in 1942 and an image of a Gurkha Rifleman from Operation Longcloth. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

None of this information was previously known to me. Like so many of the more fortunate men from the first Chindit Operation, those who had survived to return home after the war was over, Bernard's role in 1943 had so far eluded my research. His part in Operation Longcloth was brought to my attention by an email from his son, Brendan Keelan.

In his first email contact, dated 28th April 2014 Brendan had this to say about his father:

I found your website fairly recently and just wanted to add a bit of information about my father Bernard Keelan who was with 5 Column and was one of those few members of that group who made the trek into China.

I've recently seen a letter he sent from after the expedition which lists his details as 3774986 HQ Company Signals, 13th Bn King's Regiment.

As seems to be customary with these veterans, he shared some of his experiences with us, but not the horrors, and I never got him to commit his memories to paper before he died in 1993. I do recall some of the comments on individuals though. He was a great admirer of Bernard Fergusson and also told me that for the dispersal with Column 7, he was originally allocated to Lt. Campbell-Paterson's group with a plan to steal a river boat and sail down the Irrawaddy.

My Dad didn't think much of that idea and chose the march on into China instead. I'm sure he would have been glad to know Campbell-Paterson did at least manage to survive. He wasn't a great fan of Gilkes, recording that he had put a man on a charge even during the trek out. He mentioned some of his colleagues including an ex-Birkenhead bus conductor called Frank Townson, who was fluent in German and so obviously placed in the wrong theatre! Unfortunately he was one of those who didn't make it out.

As you can imagine I was delighted to receive this new information from Brendan and replied to his email immediately:

Dear Brendan,

Thank you for your email contact via my website. It is truly wonderful that you have taken the trouble to get in touch. I have not seen mention of your father, Bernard, before, which for me is very exciting. Discovering new members of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade is always exciting, but for him to be a member of Column 5 is an added bonus.

Bernard must of been a very fit and determined character to achieve the dispersal through the Yunnan Borders, especially coming as he did from Column 5, who as you will know, had the worst time of it in terms of rations and meeting the enemy in action.

Brendan sent me a photograph of his father from early on in the war, probably 1940 or 1941, but certainly before the 13th King's left for India. He also shared two of Bernard's airgraph letters sent home during his time at the Chindit training camp in Patharia. These were addressed to Bernard's mother and like most correspondence home from those times were fairly light-hearted in content, discussing and enquiring about the health and happiness of various family members.

One thing the airgraphs did confirm for me was Bernard's placement in A' Company of the 13th King's, this matches perfectly with his eventual attachment to Chindit Column 5.

At the end of June 1942 the men from A' Company became the Infantry element for Chindit Column 5, the men from B' Company went over to Column 6, C' Company to Column 7 and D' Company made up the numbers for Column 8. Due to mis-fortune and a high degree of sickness Chindit Column 6 was disbanded in late December and the remaining personnel distributed amongst the other three units.

Bernard's placement with HQ Company Signals in Column 5 would almost certainly mean that he marched day in and day out close to his commander and namesake, Major Bernard Fergusson. Brendan also mentioned that his father had spoken about his friendship with a Gurkha soldier from those days in the Burmese jungle. He pronounced the Gurkha's name as 'Karakbader'. In Fergusson's Head Quarters there would have been two sets of Gurkhas present, the commander's own bodyguard platoon and then the muleteers for the Column radio equipment, perhaps Karakbader served with one of these units?

Seen below are the two Airgraphs sent home by Bernard Keelan to his mother in 1942 and an image of a Gurkha Rifleman from Operation Longcloth. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

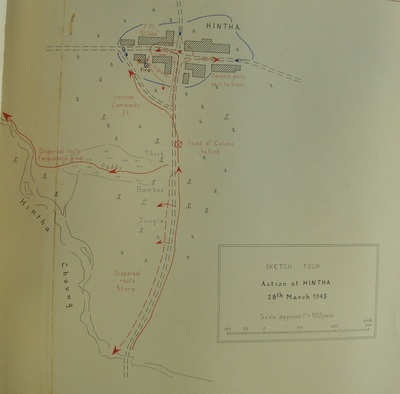

In another of Brendan's emails he recalled his father mentioning being involved in a bayonet charge against the Japanese in 1943. I feel confident that Bernard was talking about the engagement between Column 5 and an enemy garrison force at the village of Hintha. This attack, on the 28th March 1943, was effectively the Column's 'Waterloo', after which it never recovered as a complete fighting unit.

During the third week of March 1943, Column 5 had been given orders to create a diversion for the rest of the Chindit Brigade, which was now trapped in a three-sided bag between the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers to the west and north and the Mongmit-Myitson motor road to the south. Brigadier Wingate had instructed Fergusson to "trail his coat" and lead the Japanese pursuers away from the general direction of the Irrawaddy and in particular the area around the town of Inywa, where Wingate had hoped to cross.

By March 28th the column had reached the village of Hintha which was situated in an area of thick and tight-set bamboo scrub. Any attempt to navigate around the settlement proved impossible, reluctantly, Fergusson decided to enter the village by the main track and check for the presence of any enemy patrols. He unluckily stumbled upon such a patrol and a fire-fight ensued.

Fighting platoons led by Lieutenant Stibbe and Jim Harman entered the village in an attempt to clear the road of Japanese. These were met in full force by the enemy and several casualties were taken on both sides. Stibbe, himself now wounded, returned to the base position of the column and reported to the Major that the situation was getting very hot and that the Japanese were making any forward movement extremely difficult.

From his book 'Beyond the Chindwin' Bernard Fergusson takes up the story:

"Alec Macdonald was beside me, and immediately said: "I'll have a look. Come on," and disappeared up the track. I had a feeling that, having failed on Peter Dorans' flank, the Japs would try and come in on the right, somewhere down the column; so I passed the word back to try and work a small flank guard into the jungle on that side if possible.

Then I went back to the T-junction, and made arrangements to attract all the attention we could, so as to give Alec a free run. I seemed to spend the whole action trotting up and down that seventy yards of track.

There came another burst of fire from the little track, a mixture of light machine gun, tommy-guns and grenades. The Commando Platoon alone in the column had tommy-guns, which was one of the reasons I had selected them for the role. Their cheerful rattle, however, meant that the little track was no longer clear. I hurried back to the fork, and there found Denny Sharp.

"This is going to be no good," I said. "Denny, take all the animals you can find, go back to the chaung and see if you can get down it. We'll go on playing about here to keep their attention fixed; I'll try and join you farther down the chaung, but if I don't then you know the next rendezvous point. Keep away from Chaungmido, as we don't want to get Brigade muddled up in this."

From his own book, 'Return via Rangoon', Lieutenant Philip Stibbe remembered the 28th March 1943:

We did not have to wait many seconds before machine-gun fire started from somewhere down the left fork of the "T" junction; the Major told me to take my platoon in with the bayonet. My platoon were in threes behind me, facing down the the track in the direction of the firing. It was impossible to see much in the dark, but there was no time to waste, so I shouted "Bayonets" and told Corporal Litherland and the left-hand section to deal with anything on the left of the track and Corporal Handley and Corporal Berry with the right-hand section to deal with anything on the right.

Corporal Dunn was in the centre immediately behind me with his section and I the told him to follow me and deal with anything immediately in front. All this took only a moment; the Major shouted "Good luck", I gave the word and we doubled forward.

It is difficult to realise what is happening in the heat of battle and even more difficult to give a coherent account of it the afterwards, but I remember seeing something move under a house on our left as we went forward and firing at it with my revolver. Then machine-gun fire seemed to come from several directions in front of us and I hurled a grenade at the nearest gun and we got down while it went off.

I was standing up to go forward again when something knocked me down and I felt a pain in my left shoulder-blade. The platoon rushed on past me. What was happening in the darkness ahead I could not tell but there was a confused medley of shots, screams, shouts and explosions.

Stibbe was seriously wounded at Hintha, so much so that within a few short hours he realised he could not continue to march and had to be left by the column in the scrub jungle close to the village. He later became a prisoner of war, surviving almost two years in Rangoon Jail before he was liberated in late April 1945.

It was shortly after the battle of Hintha that Bernard's mate, Frank Townson died, according to the CWGC website on the 29th March 1943. For the record, Corporal Handley and Corporal Berry were both killed at Hintha.

Here are the CWGC details for Francis Basil Townson:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2527514/TOWNSON,%20FRANCIS%20BASIL

Seen below are some images in relation to the engagement at the village of Hintha. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

During the third week of March 1943, Column 5 had been given orders to create a diversion for the rest of the Chindit Brigade, which was now trapped in a three-sided bag between the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers to the west and north and the Mongmit-Myitson motor road to the south. Brigadier Wingate had instructed Fergusson to "trail his coat" and lead the Japanese pursuers away from the general direction of the Irrawaddy and in particular the area around the town of Inywa, where Wingate had hoped to cross.

By March 28th the column had reached the village of Hintha which was situated in an area of thick and tight-set bamboo scrub. Any attempt to navigate around the settlement proved impossible, reluctantly, Fergusson decided to enter the village by the main track and check for the presence of any enemy patrols. He unluckily stumbled upon such a patrol and a fire-fight ensued.

Fighting platoons led by Lieutenant Stibbe and Jim Harman entered the village in an attempt to clear the road of Japanese. These were met in full force by the enemy and several casualties were taken on both sides. Stibbe, himself now wounded, returned to the base position of the column and reported to the Major that the situation was getting very hot and that the Japanese were making any forward movement extremely difficult.

From his book 'Beyond the Chindwin' Bernard Fergusson takes up the story:

"Alec Macdonald was beside me, and immediately said: "I'll have a look. Come on," and disappeared up the track. I had a feeling that, having failed on Peter Dorans' flank, the Japs would try and come in on the right, somewhere down the column; so I passed the word back to try and work a small flank guard into the jungle on that side if possible.

Then I went back to the T-junction, and made arrangements to attract all the attention we could, so as to give Alec a free run. I seemed to spend the whole action trotting up and down that seventy yards of track.

There came another burst of fire from the little track, a mixture of light machine gun, tommy-guns and grenades. The Commando Platoon alone in the column had tommy-guns, which was one of the reasons I had selected them for the role. Their cheerful rattle, however, meant that the little track was no longer clear. I hurried back to the fork, and there found Denny Sharp.

"This is going to be no good," I said. "Denny, take all the animals you can find, go back to the chaung and see if you can get down it. We'll go on playing about here to keep their attention fixed; I'll try and join you farther down the chaung, but if I don't then you know the next rendezvous point. Keep away from Chaungmido, as we don't want to get Brigade muddled up in this."

From his own book, 'Return via Rangoon', Lieutenant Philip Stibbe remembered the 28th March 1943:

We did not have to wait many seconds before machine-gun fire started from somewhere down the left fork of the "T" junction; the Major told me to take my platoon in with the bayonet. My platoon were in threes behind me, facing down the the track in the direction of the firing. It was impossible to see much in the dark, but there was no time to waste, so I shouted "Bayonets" and told Corporal Litherland and the left-hand section to deal with anything on the left of the track and Corporal Handley and Corporal Berry with the right-hand section to deal with anything on the right.

Corporal Dunn was in the centre immediately behind me with his section and I the told him to follow me and deal with anything immediately in front. All this took only a moment; the Major shouted "Good luck", I gave the word and we doubled forward.

It is difficult to realise what is happening in the heat of battle and even more difficult to give a coherent account of it the afterwards, but I remember seeing something move under a house on our left as we went forward and firing at it with my revolver. Then machine-gun fire seemed to come from several directions in front of us and I hurled a grenade at the nearest gun and we got down while it went off.

I was standing up to go forward again when something knocked me down and I felt a pain in my left shoulder-blade. The platoon rushed on past me. What was happening in the darkness ahead I could not tell but there was a confused medley of shots, screams, shouts and explosions.

Stibbe was seriously wounded at Hintha, so much so that within a few short hours he realised he could not continue to march and had to be left by the column in the scrub jungle close to the village. He later became a prisoner of war, surviving almost two years in Rangoon Jail before he was liberated in late April 1945.

It was shortly after the battle of Hintha that Bernard's mate, Frank Townson died, according to the CWGC website on the 29th March 1943. For the record, Corporal Handley and Corporal Berry were both killed at Hintha.

Here are the CWGC details for Francis Basil Townson:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2527514/TOWNSON,%20FRANCIS%20BASIL

Seen below are some images in relation to the engagement at the village of Hintha. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

So how did Bernard Keelan end up exiting Burma in 1943 with 7 Column?

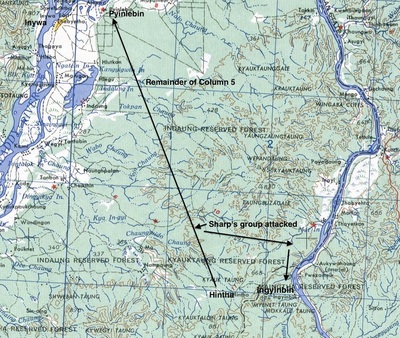

As we have already heard, Major Fergusson had ordered Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp to take the majority of the column away from Hintha and lead them roughly north-east towards the Irrawaddy River (see map above).

Unfortunately, the unit had lost cohesion and many men failed to re-join the column at the next agreed rendezvous point. Denny Sharp was now in command of a large group of soldiers (roughly 160 men and their animals) including Pte. Keelan and my own grandfather, Pte. Arthur Howney. Disaster struck Sharp's group the next day and barely two miles outside of Hintha, when a Japanese patrol ambushed the men, cutting off around one hundred Chindits from the front of the line.

From a witness statement given by CQMS. E. Henderson after reaching the safety of Allied held territory, comes this account of the period directly after the action at Hintha.

"I was with number five Column of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, during operations in Burma in 1943. The British Other Ranks mentioned below were in my dispersal group all the way through the campaign until we made contact with the enemy in a village in Burma called Hintha.

After the action in that village was over, these soldiers were still in my dispersal group, which was then commanded by Flight Lieutenant Sharp of the RAF. We halted and unsaddled our mules so we could go ahead much quicker.

After starting off from that halt, which was approximately 2 miles from Hintha, we were attacked by a Japanese patrol. This caused a gap in the column, but we kept marching for approximately another 4 miles and then stopped, we waited for these people to catch up, but they must have gone wrong way, because they did not rejoin us again. I saw all these men for the last time approximately two and a half miles north east of Hintha. They were all alive, and last seen on 28th March 1943."

Signed by, CQMS. E.G. Henderson, 13th Kings Regiment.

The men in question did not attempt to find or re-join any of Major Fergusson's three main dispersal parties after they were ambushed, but instead moved away from the area in small parties, where they rather fortuitously met up with Major Gilkes and Column 7 on the banks of the Shweli River (please see map above). Many of these soldiers never made it out of Burma alive in 1943, some perished on the arduous journey north towards the Chinese Borders, while others became prisoners of war and died in captivity.

These are the men that Ernest Henderson lists in his witness statement as being part of the ambushed group:

3777480 Pte. F.B. Townson

4198452 Pte. J. Fitzpatrick

3186149 Corp. W. McGee

5119278 Pte. J. Donovan

3779346 Pte. D. Clarke

3779444 Pte. T. A. James

4202370 Pte. W. Roche

3779364 Sgt. R.A. Rothwell BEM.

3777998 Pte. R. Hulme

4195166 Pte. E. Kenna

5114059 Pte. N.J. Fowler

3781718 Pte. E. Hodnett

5114104 Pte. J. Powell

3779270 Pte. W.C. Parry

5119069 L. Corp. T. Jones

3523186 Pte. F.C. Fairhurst

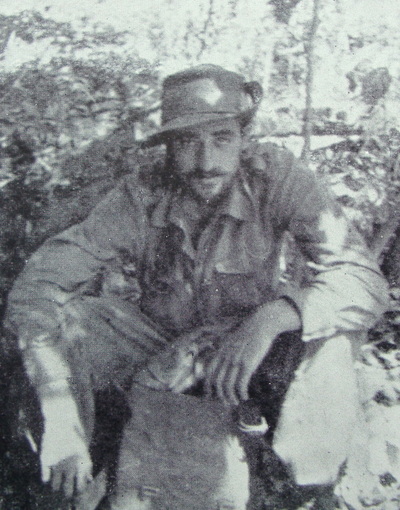

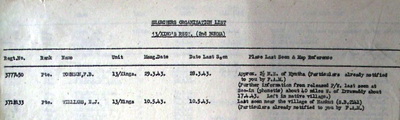

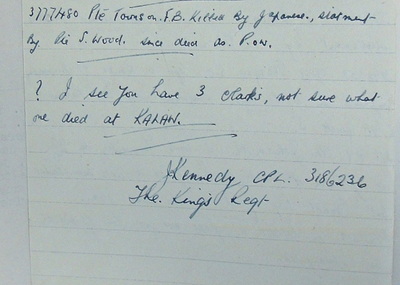

Seen below are three images in relation to the dispersal group led by Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp.

Apart from the photograph of Sharp himself taken in the Burmese jungle at some point during 1943, we also see statements about the death of Frank Townson. One is an official notification of his last known whereabouts, the other is secondhand information passed from one Chindit POW, Pte. Sidney Wood to another, Corporal John Kennedy, whilst the pair were held in Rangoon Jail. Sadly, Pte. Wood died in Rangoon, leaving Kennedy to relay the information after his liberation in May 1945.

Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As we have already heard, Major Fergusson had ordered Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp to take the majority of the column away from Hintha and lead them roughly north-east towards the Irrawaddy River (see map above).

Unfortunately, the unit had lost cohesion and many men failed to re-join the column at the next agreed rendezvous point. Denny Sharp was now in command of a large group of soldiers (roughly 160 men and their animals) including Pte. Keelan and my own grandfather, Pte. Arthur Howney. Disaster struck Sharp's group the next day and barely two miles outside of Hintha, when a Japanese patrol ambushed the men, cutting off around one hundred Chindits from the front of the line.

From a witness statement given by CQMS. E. Henderson after reaching the safety of Allied held territory, comes this account of the period directly after the action at Hintha.

"I was with number five Column of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, during operations in Burma in 1943. The British Other Ranks mentioned below were in my dispersal group all the way through the campaign until we made contact with the enemy in a village in Burma called Hintha.

After the action in that village was over, these soldiers were still in my dispersal group, which was then commanded by Flight Lieutenant Sharp of the RAF. We halted and unsaddled our mules so we could go ahead much quicker.

After starting off from that halt, which was approximately 2 miles from Hintha, we were attacked by a Japanese patrol. This caused a gap in the column, but we kept marching for approximately another 4 miles and then stopped, we waited for these people to catch up, but they must have gone wrong way, because they did not rejoin us again. I saw all these men for the last time approximately two and a half miles north east of Hintha. They were all alive, and last seen on 28th March 1943."

Signed by, CQMS. E.G. Henderson, 13th Kings Regiment.

The men in question did not attempt to find or re-join any of Major Fergusson's three main dispersal parties after they were ambushed, but instead moved away from the area in small parties, where they rather fortuitously met up with Major Gilkes and Column 7 on the banks of the Shweli River (please see map above). Many of these soldiers never made it out of Burma alive in 1943, some perished on the arduous journey north towards the Chinese Borders, while others became prisoners of war and died in captivity.

These are the men that Ernest Henderson lists in his witness statement as being part of the ambushed group:

3777480 Pte. F.B. Townson

4198452 Pte. J. Fitzpatrick

3186149 Corp. W. McGee

5119278 Pte. J. Donovan

3779346 Pte. D. Clarke

3779444 Pte. T. A. James

4202370 Pte. W. Roche

3779364 Sgt. R.A. Rothwell BEM.

3777998 Pte. R. Hulme

4195166 Pte. E. Kenna

5114059 Pte. N.J. Fowler

3781718 Pte. E. Hodnett

5114104 Pte. J. Powell

3779270 Pte. W.C. Parry

5119069 L. Corp. T. Jones

3523186 Pte. F.C. Fairhurst

Seen below are three images in relation to the dispersal group led by Flight-Lieutenant Denny Sharp.

Apart from the photograph of Sharp himself taken in the Burmese jungle at some point during 1943, we also see statements about the death of Frank Townson. One is an official notification of his last known whereabouts, the other is secondhand information passed from one Chindit POW, Pte. Sidney Wood to another, Corporal John Kennedy, whilst the pair were held in Rangoon Jail. Sadly, Pte. Wood died in Rangoon, leaving Kennedy to relay the information after his liberation in May 1945.

Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Now let us return to the western banks of the Shweli River, where on the 3rd April Bernard Keelan and the other men lost from Column 5, literally bumped into Major Kenneth Gilkes and his men. Column 7 had left Brigadier Wingate and Column 8 at the aborted crossing of the Irrawaddy River on the 29th-30th March and moved quickly east towards the Shweli. Here Gilkes hoped to find a suitable crossing point over this last watery obstacle, before heading further east into the Yunnan Borders of China.

He had recently received a large supply drop for his men, including new boots and ammunition in addition to the badly needed food rations. He had not reckoned with inheriting nearly 100 new mouths to feed from Column 5 and was extremely concerned at the condition of these soldiers and whether they would be fit enough to make the journey out via China.

For the next week the men marched southwards, often with the fast flowing Shweli on their immediate left hand-side. Many potential crossing points had been looked at, but none proved possible, whether that be because of the lack of boats available or the unexpected presence of the enemy. Gilkes took his men further south, close to the town of Mongmit, where the Shweli meandered round to the east and struck out directly towards the Chinese Borders.

On the 9th April the men were distributed into smaller dispersal parties, Bernard Keelan was allocated to an officer named Alan Campbell-Paterson formerly of the Royal Scots and originally part of Column 8, whilst my own grandfather was placed in to the very next group led by Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood. As we already know from Brendan's information, his father was nor overly impressed with Campbell-Paterson's leadership qualities or the highly improbable plan to hi-jack a boat and sail it down the Irrawaddy River.

However, I believe that for the time being at least Bernard remained with his allotted dispersal group as the majority of the men from Column 7 were still marching together at this point in time. On the 14th April the men from Column 7 finally made it over the Shweli River at a place called Nayok (see map below). I believe that soon after this point, possibly within the next few days, the dispersal parties did split up and head off in varying different directions according to the wishes of those officers which commanded each unit.

I believe that it was around this time that Bernard Keelan decided to drop out of the dispersal group led by Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson and join up with another party. It is most likely that he chose to be part of the largest group commanded by Major Gilkes and Captain Cottrell, but it is possible that he may have chosen to join up with the party led by Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood, as the two groups had been in close proximity to each other over those final few days.

In any event, Bernard's decision proved inspired, as within the next few hours, Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson would be captured by the Japanese and most of his dispersal party either taken prisoner with him or killed in their bid to escape.

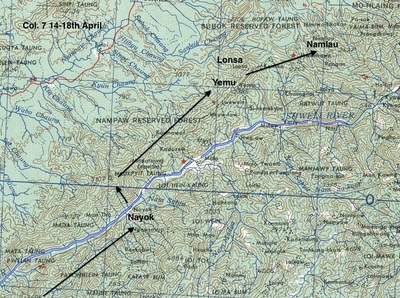

To help explain the situation, perhaps more clearly, seen below are three images in relation to this point in time. Firstly, a map of the area close to Nayok on the southern banks of the Shweli River, where Column 7 crossed over on the 14th April. This map also shows the villages of Yemu, where Musgrave-Wood states he last saw Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson, the village of Namlau, where Campbell-Paterson was final captured and the village of Lonsa, where my own grandfather became a prisoner of war.

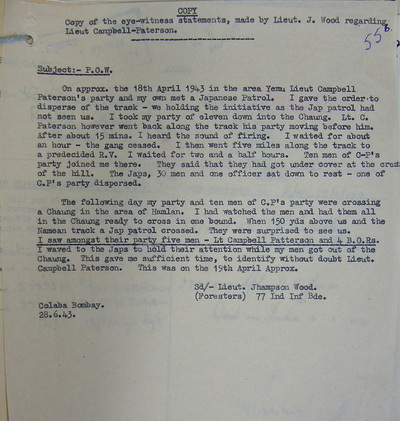

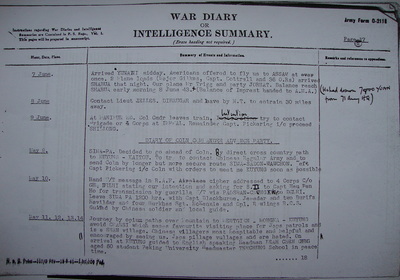

Also shown is a witness statement given by Jon Musgrave-Wood after he reached the safety of Allied lines in late June 1943, explaining the circumstances of the last time he saw Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson and his men. This document does read a little strangely and contains some spelling mistakes, however it does give the reader an understanding of what happened on that day.

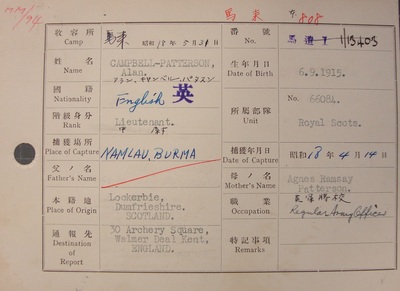

Finally, the POW index card of Alan Campbell-Paterson showing his Army details, next of kin contacts and place and date of capture. Alan was taken originally to Rangoon Jail, but was flown out to Singapore with some other Chindit prisoners who were then interrogated by the Japanese secret police, the Kempai-tai at Changi POW Camp. He and the rest of these officers all survived their time as prisoners of war and were liberated after the Japanese surrendered in September 1945.

Please click on any image to bring to forward on the page. To read more about my own grandfather and his capture at Lonsa village in April 1943, please click on the following link: Arthur Leslie Howney

He had recently received a large supply drop for his men, including new boots and ammunition in addition to the badly needed food rations. He had not reckoned with inheriting nearly 100 new mouths to feed from Column 5 and was extremely concerned at the condition of these soldiers and whether they would be fit enough to make the journey out via China.

For the next week the men marched southwards, often with the fast flowing Shweli on their immediate left hand-side. Many potential crossing points had been looked at, but none proved possible, whether that be because of the lack of boats available or the unexpected presence of the enemy. Gilkes took his men further south, close to the town of Mongmit, where the Shweli meandered round to the east and struck out directly towards the Chinese Borders.

On the 9th April the men were distributed into smaller dispersal parties, Bernard Keelan was allocated to an officer named Alan Campbell-Paterson formerly of the Royal Scots and originally part of Column 8, whilst my own grandfather was placed in to the very next group led by Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood. As we already know from Brendan's information, his father was nor overly impressed with Campbell-Paterson's leadership qualities or the highly improbable plan to hi-jack a boat and sail it down the Irrawaddy River.

However, I believe that for the time being at least Bernard remained with his allotted dispersal group as the majority of the men from Column 7 were still marching together at this point in time. On the 14th April the men from Column 7 finally made it over the Shweli River at a place called Nayok (see map below). I believe that soon after this point, possibly within the next few days, the dispersal parties did split up and head off in varying different directions according to the wishes of those officers which commanded each unit.

I believe that it was around this time that Bernard Keelan decided to drop out of the dispersal group led by Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson and join up with another party. It is most likely that he chose to be part of the largest group commanded by Major Gilkes and Captain Cottrell, but it is possible that he may have chosen to join up with the party led by Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood, as the two groups had been in close proximity to each other over those final few days.

In any event, Bernard's decision proved inspired, as within the next few hours, Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson would be captured by the Japanese and most of his dispersal party either taken prisoner with him or killed in their bid to escape.

To help explain the situation, perhaps more clearly, seen below are three images in relation to this point in time. Firstly, a map of the area close to Nayok on the southern banks of the Shweli River, where Column 7 crossed over on the 14th April. This map also shows the villages of Yemu, where Musgrave-Wood states he last saw Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson, the village of Namlau, where Campbell-Paterson was final captured and the village of Lonsa, where my own grandfather became a prisoner of war.

Also shown is a witness statement given by Jon Musgrave-Wood after he reached the safety of Allied lines in late June 1943, explaining the circumstances of the last time he saw Lieutenant Campbell-Paterson and his men. This document does read a little strangely and contains some spelling mistakes, however it does give the reader an understanding of what happened on that day.

Finally, the POW index card of Alan Campbell-Paterson showing his Army details, next of kin contacts and place and date of capture. Alan was taken originally to Rangoon Jail, but was flown out to Singapore with some other Chindit prisoners who were then interrogated by the Japanese secret police, the Kempai-tai at Changi POW Camp. He and the rest of these officers all survived their time as prisoners of war and were liberated after the Japanese surrendered in September 1945.

Please click on any image to bring to forward on the page. To read more about my own grandfather and his capture at Lonsa village in April 1943, please click on the following link: Arthur Leslie Howney

Regardless of which dispersal group Bernard ended up with, the next eight weeks would prove an extremely tough test for all these men, examining their will and determination to survive and the hope to see their homes and families once again. Many men fell out and perished along the wayside, never reaching the safety of Allied held territory and probably more importantly some decent food to eat. At last, by the first week in June 1943, the ailing Chindits began to straggle in to the Chinese city of Kunming, here they were met by an officer of the United States Airforce. After a short period of recuperation the men were flown back to Assam aboard USAAF Dakotas.

Not one of the exhausted Chindits could ever of imagined that the last leg of their incredible journey would be made in such a swift and relatively luxurious manner. Back in India they were given full medical attention and of course enjoyed freshly cooked meals once more. Sadly, even at this late and seemingly secure stage, some of the men lost their battle for life, it almost seemed that as soon as their minds relaxed thinking that their ordeal was finally over, their bodies gave way and the unfortunate men drifted into death.

Most of the recovering Chindits were given a long period of leave in the hill stations of Assam, where they enjoyed the pleasant and cool mountain air. Eventually they returned to their unit, the 13th King's Liverpool, who were now stationed at the Napier Barracks in the city of Karachi.

In one of Brendan's emails he mentioned a humorous anecdote his father once told him about his journey out via China in 1943. Bernard remembered how a Chinese Officer who was marching with the Chindits used to sing his own personal version of the song 'Rose Marie'.

Brendan also told me that his Dad had gone back into Burma a second time before the war finally came to an end. He is not sure why, or what Bernard's role might have been, but with the experience gained on Operation Longcloth and his expertise in Signals, this is not so surprising.

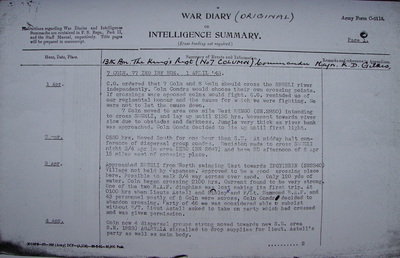

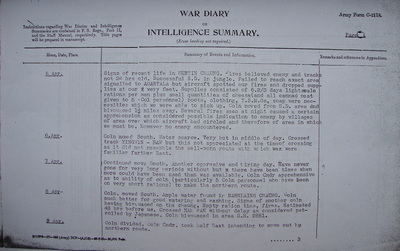

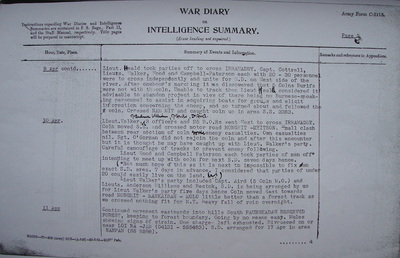

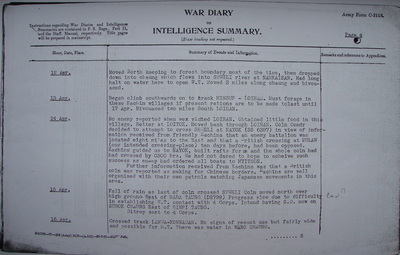

Seen below are some final images in relation to this story. These include pages from the Column 7 War Diary at various moments during their march for freedom and some photographs of other men mentioned along the way. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Not one of the exhausted Chindits could ever of imagined that the last leg of their incredible journey would be made in such a swift and relatively luxurious manner. Back in India they were given full medical attention and of course enjoyed freshly cooked meals once more. Sadly, even at this late and seemingly secure stage, some of the men lost their battle for life, it almost seemed that as soon as their minds relaxed thinking that their ordeal was finally over, their bodies gave way and the unfortunate men drifted into death.

Most of the recovering Chindits were given a long period of leave in the hill stations of Assam, where they enjoyed the pleasant and cool mountain air. Eventually they returned to their unit, the 13th King's Liverpool, who were now stationed at the Napier Barracks in the city of Karachi.

In one of Brendan's emails he mentioned a humorous anecdote his father once told him about his journey out via China in 1943. Bernard remembered how a Chinese Officer who was marching with the Chindits used to sing his own personal version of the song 'Rose Marie'.

Brendan also told me that his Dad had gone back into Burma a second time before the war finally came to an end. He is not sure why, or what Bernard's role might have been, but with the experience gained on Operation Longcloth and his expertise in Signals, this is not so surprising.

Seen below are some final images in relation to this story. These include pages from the Column 7 War Diary at various moments during their march for freedom and some photographs of other men mentioned along the way. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Dorothea and Brendan Keelan for all their help and assistance in compiling this story.

Bernard was quite clearly a very determined and resilient man, not only by being one of the few men able to survive the long march out via the Chinese Borders in 1943, but also for having recovered enough to go back into Burma later in the war. This feat was accomplished by only a handful of Longcloth veterans.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, October 2014.

Bernard was quite clearly a very determined and resilient man, not only by being one of the few men able to survive the long march out via the Chinese Borders in 1943, but also for having recovered enough to go back into Burma later in the war. This feat was accomplished by only a handful of Longcloth veterans.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, October 2014.