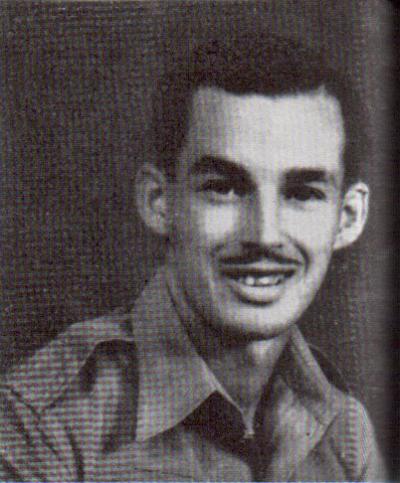

Pte. George Sullivan (5119801 Warwickshire Regiment).

Cap badge of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

Cap badge of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

George Sullivan was born on the 10th March 1916 in the Paddington area of West London. A butcher by trade, George married Mary Catherine Scaplehorn on the 24th March 1940 at St. Aidan's Roman Catholic Church, Old Oak Lane, East Acton. The couple lived in the Shepherds Bush area and had one daughter.

Pte. Sullivan was not an original member of the 13th King's, but had been posted to the Royal Warwickshire Regiment on enlistment. I have used George's Army service number and his original regiment as a means to identify him against another soldier also named George Sullivan who also features in the pages of this website.

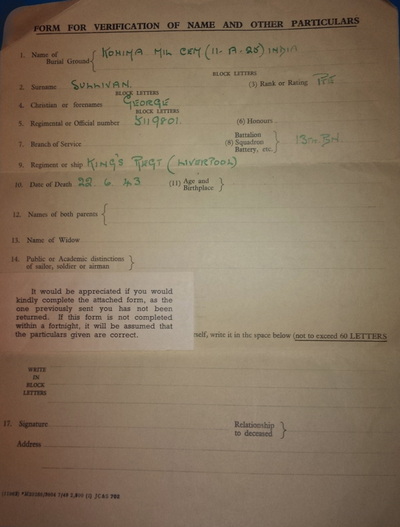

Sadly, George did not survive his time as a Chindit in 1943, he died on the 22nd of June 1943 in Kohima General Hospital. He was 27 years old. After the war was over he was buried in Kohima War Cemetery with the grave reference 11.A.25.

Here are George's CWGC details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2602138/SULLIVAN,%20GEORGE

The draft of Royal Warwickshire's, possibly from the 8th battalion had reached the sub-continent by mid-1942 and joined Chindit training in the Central Provinces of India on the 26th September. According the the War diary for the 13th King's that month the new reinforcements, which included the men from the Warwickshire's; "seem quite a good lot". Faint praise indeed from the battalion Adjutant, Captain David Hastings.

George and most of the other men from his draft were placed into Chindit Column 8, under the overall command of Major Walter Purcell Scott. Once inside Burma this column shadowed Wingate's own Head Quarters Brigade for the vast majority of the expedition, performing several ambushes and assaults on various Japanese garrisons and positions. Many of these actions, Pinlebu for example, have already been described in the pages of this website. Please use the search panel in the top right corner of the page to read more about Column 8 and the unit's adventures during Operation Longcloth.

After dispersal was called in late March 1943, Column 8 attempted to head back to India as one complete unit comprising of approximately 320 men. By the 12th of April and having struggled to re-cross the Irrawaddy River, the order was given by Major Scott for the column to split up into smaller dispersal groups of 25-30 men. By this time the column numbers had been supplemented by the men from Northern Group HQ led by Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke. George Sullivan found himself in a dispersal group made up of many men from Cooke's Head Quarters and commanded by a young officer named John Francis Pickering, formerly of the Royal Sussex Regiment, but now just like George, attached to the 13th King's.

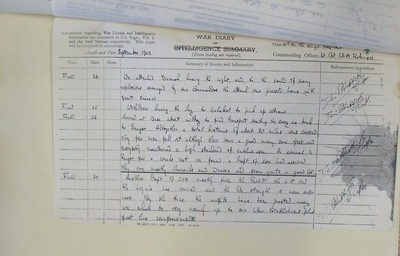

This is how the Column's war diary described the break up into dispersal groups and the following few days. From the book 'Wingate's Lost Brigade' and with the kind permission of author Philip Chinnery:

On 12th April, the front of the column was approaching a newly built bamboo bridge over a chaung when they bumped into a couple of Japs who turned and bolted back into the jungle. Intense firing broke out and Sergeant Bridgeman and Private Beard were killed, while Privates Lawton and Witheridge were both seriously wounded.

Most of the column turned around and disappeared along the track they had come down, leaving Major Scott and a small party isolated. It was not until the evening that the column reassembled and it was discovered that Lieutenant Horncastle and 14 others were missing. It was thought that they might have moved off as a separate party.

The column was up and moving at 0430 hours the next morning. The going was quite good but they now had three wounded on stretchers to carry with them. Major Scott and Lieutenant Colonel Cooke held an officers' conference and it was decided that they would request one last supply drop before breaking up into dispersal groups to cross the Irrawaddy.

The dispersal groups were arranged as follows:

Lieutenant Colonel Cooke, Lieutenant Borrow and half of Group Headquarters;

Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and the other half of Group Headquarters;

Major Scott with Column Headquarters, 17 Platoon and two sections of 16 Platoon;

Captain Whitehead and his Burma Rifles less those already allocated to assist the dispersal groups, plus Flying Officer Wheatley and a section of 16 Platoon;

Lieutenants Carroll, Hamilton-Bryant with Support Group and 19 Platoon;

Lieutenants Neill and Sprague with the Gurkha Platoon and 142 Commando Platoon.

On 15th April, Captain Whitehead and his dispersal group, together with the stretcher party under Sergeant Parsons and the Medical Officer, Captain Heathcote, left the column. They planned to move to the east of Bhamo, thence north of Myitkyina to Fort Hertz. If this plan failed they would cross the Irrawaddy north of Bhamo and then go west towards the Chindwin. On the way they intended to leave the stretcher cases at a friendly Kachin village.

Captain Whitehead's party had great difficulty gelling down the eastern slopes of the mountains to the Bhamo Plain and the first villages they visited were deserted. The escort party under Lieutenant Hamilton-Bryan returned after a couple of days, anxious not to lose contact with the main column. The decision of the MO to remain with Whitehead's group was rather controversial as it left the bulk of the column without a doctor. The fate of the stretcher party is unknown.

Meanwhile, the column received their supply drop on 17th April: four days' rations including corned beef and mutton and another charged radio battery. The following day Lieutenants Neill, Sprague and Gillow left with their dispersal group, intending to drop on to the plain before heading for Myale where they proposed to cross the Irrawaddy. Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and their group left for Watto on the Irrawaddy, and half an hour later Major Scott and the rest of the column continued on their journey to Sinkan. It had been decided that Lieutenant Colonel Cooke's dispersal group, together with that of Lieutenant Carroll, would remain with Scott for the time being, making a large party of six officers and 170 men, plus one mule with the wireless set.

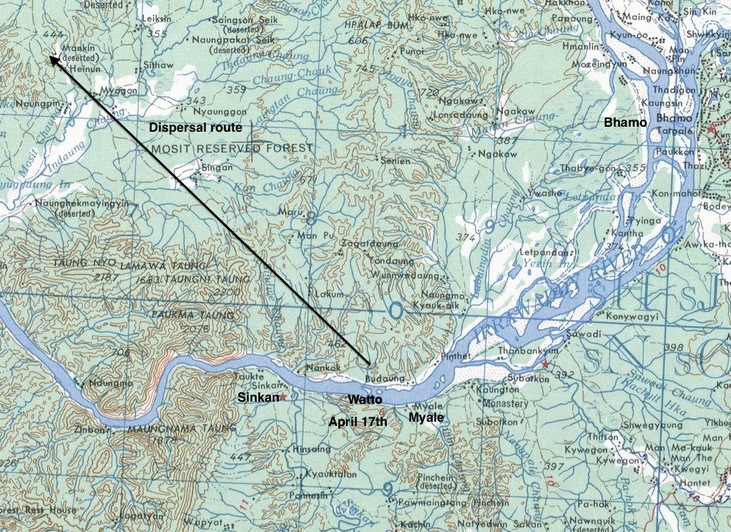

Seen below is a map of the area around the Irrawaddy close to where the dispersal groups were arranged and showing the general direction that some of the parties planned to take in vacating Burma that year. Please click on the map to bring it forward on the page.

Pte. Sullivan was not an original member of the 13th King's, but had been posted to the Royal Warwickshire Regiment on enlistment. I have used George's Army service number and his original regiment as a means to identify him against another soldier also named George Sullivan who also features in the pages of this website.

Sadly, George did not survive his time as a Chindit in 1943, he died on the 22nd of June 1943 in Kohima General Hospital. He was 27 years old. After the war was over he was buried in Kohima War Cemetery with the grave reference 11.A.25.

Here are George's CWGC details: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2602138/SULLIVAN,%20GEORGE

The draft of Royal Warwickshire's, possibly from the 8th battalion had reached the sub-continent by mid-1942 and joined Chindit training in the Central Provinces of India on the 26th September. According the the War diary for the 13th King's that month the new reinforcements, which included the men from the Warwickshire's; "seem quite a good lot". Faint praise indeed from the battalion Adjutant, Captain David Hastings.

George and most of the other men from his draft were placed into Chindit Column 8, under the overall command of Major Walter Purcell Scott. Once inside Burma this column shadowed Wingate's own Head Quarters Brigade for the vast majority of the expedition, performing several ambushes and assaults on various Japanese garrisons and positions. Many of these actions, Pinlebu for example, have already been described in the pages of this website. Please use the search panel in the top right corner of the page to read more about Column 8 and the unit's adventures during Operation Longcloth.

After dispersal was called in late March 1943, Column 8 attempted to head back to India as one complete unit comprising of approximately 320 men. By the 12th of April and having struggled to re-cross the Irrawaddy River, the order was given by Major Scott for the column to split up into smaller dispersal groups of 25-30 men. By this time the column numbers had been supplemented by the men from Northern Group HQ led by Lieutenant-Colonel S.A. Cooke. George Sullivan found himself in a dispersal group made up of many men from Cooke's Head Quarters and commanded by a young officer named John Francis Pickering, formerly of the Royal Sussex Regiment, but now just like George, attached to the 13th King's.

This is how the Column's war diary described the break up into dispersal groups and the following few days. From the book 'Wingate's Lost Brigade' and with the kind permission of author Philip Chinnery:

On 12th April, the front of the column was approaching a newly built bamboo bridge over a chaung when they bumped into a couple of Japs who turned and bolted back into the jungle. Intense firing broke out and Sergeant Bridgeman and Private Beard were killed, while Privates Lawton and Witheridge were both seriously wounded.

Most of the column turned around and disappeared along the track they had come down, leaving Major Scott and a small party isolated. It was not until the evening that the column reassembled and it was discovered that Lieutenant Horncastle and 14 others were missing. It was thought that they might have moved off as a separate party.

The column was up and moving at 0430 hours the next morning. The going was quite good but they now had three wounded on stretchers to carry with them. Major Scott and Lieutenant Colonel Cooke held an officers' conference and it was decided that they would request one last supply drop before breaking up into dispersal groups to cross the Irrawaddy.

The dispersal groups were arranged as follows:

Lieutenant Colonel Cooke, Lieutenant Borrow and half of Group Headquarters;

Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and the other half of Group Headquarters;

Major Scott with Column Headquarters, 17 Platoon and two sections of 16 Platoon;

Captain Whitehead and his Burma Rifles less those already allocated to assist the dispersal groups, plus Flying Officer Wheatley and a section of 16 Platoon;

Lieutenants Carroll, Hamilton-Bryant with Support Group and 19 Platoon;

Lieutenants Neill and Sprague with the Gurkha Platoon and 142 Commando Platoon.

On 15th April, Captain Whitehead and his dispersal group, together with the stretcher party under Sergeant Parsons and the Medical Officer, Captain Heathcote, left the column. They planned to move to the east of Bhamo, thence north of Myitkyina to Fort Hertz. If this plan failed they would cross the Irrawaddy north of Bhamo and then go west towards the Chindwin. On the way they intended to leave the stretcher cases at a friendly Kachin village.

Captain Whitehead's party had great difficulty gelling down the eastern slopes of the mountains to the Bhamo Plain and the first villages they visited were deserted. The escort party under Lieutenant Hamilton-Bryan returned after a couple of days, anxious not to lose contact with the main column. The decision of the MO to remain with Whitehead's group was rather controversial as it left the bulk of the column without a doctor. The fate of the stretcher party is unknown.

Meanwhile, the column received their supply drop on 17th April: four days' rations including corned beef and mutton and another charged radio battery. The following day Lieutenants Neill, Sprague and Gillow left with their dispersal group, intending to drop on to the plain before heading for Myale where they proposed to cross the Irrawaddy. Lieutenants Pickering, Pearce and Bennett and their group left for Watto on the Irrawaddy, and half an hour later Major Scott and the rest of the column continued on their journey to Sinkan. It had been decided that Lieutenant Colonel Cooke's dispersal group, together with that of Lieutenant Carroll, would remain with Scott for the time being, making a large party of six officers and 170 men, plus one mule with the wireless set.

Seen below is a map of the area around the Irrawaddy close to where the dispersal groups were arranged and showing the general direction that some of the parties planned to take in vacating Burma that year. Please click on the map to bring it forward on the page.

The story of Lieutenant Pickering's dispersal party and it's progress after the Irrawaddy crossing can be verified by one of the men who accompanied the young officer on the march out, Lance-Corporal George Bell. Bell's testimony also provides us with the only mention in books or diaries of George Sullivan and his fate in 1943.

"After taking another supply drop, the decision was made to split up into smaller dispersal parties. Some headed for China, while others stayed together and marched due west. Our party under Lieutenant Pearce, about fifty strong, went north-north-west. Before splitting up we shook hands with all our pals in the other groups, several of them we would never see again. Our party included three officers and two Burmese who were in the Burma Rifles and could speak both English and Burmese. They saved our lives, as they were able to enter villages and obtain information about the whereabouts of the Japs. Apart from the one occasion when they got drunk as newts in one village on rice wine.

After leaving the other groups we made for a small village on the Irrawaddy, only to find as we arrived there that the village had been moved to the other bank a few years before. It was then that we realised that our maps had been drawn up in 1912 and were extremely out of date. We made off for another village further towards the north, but got bogged down in thick jungle and so decided to halt and sleep for a few hours. This turned out to be a stroke of good luck, as it transpired that a Jap patrol had spent the night in the village and had only just moved out. From that moment on I always felt that someone above was looking out for us.

As soon as it was dark we started to cross over in a boat with a villager rowing, the water came right up to the top of the sides, I couldn't swim and so was pleased to reach the other side still afloat. Throughout the night the boat crossed and re-crossed the river until everyone was over. By that time we had no way of contacting our air base and had to rely on local villages for food, boiled rice with no salt for breakfast, lunch and dinner! We had also become lousy and our clothes were disgusting. Leeches became a real problem, they got everywhere and I mean everywhere. We were told to use a lighted cigarette to burn them off, but this advice presumed we had cigarettes, which by then we did not. At one stage the heavy smokers amongst our group bought local tobacco from a village and used one of the lads bible for roll-up papers.

We marched sometimes 20 miles in a day, re-crossing the railway and two more minor rivers. One day we came across a Burmese man who could speak English, his story did not ring true to us and so we kept him with us under guard. After collecting more rice in the next village the headman warned us that this man had recently been in the company of a Jap patrol. It was decide that it was too dangerous to let him go and that he should be shot. My section took him away from the main group and one of the Burma Rifle soldiers shot him through the head. This left us with the feeling of being judge, jury and executioner.

We slogged on for a few more days, by which time our food supplies had completely run out. I brewed up with a tea bag that must have been used at least twenty times before. Around midday we were walking along a dried-up river bed when we saw some parachutes caught up in a group of trees. We approached them carefully concerned it might be a Jap ambush or booby trap, but it was a definite ration dropping, presumably for another of our parties. The packs gave us eight days rations per man, exactly eight days later we were in a small village when a British plane came over and spotted us on the ground. They dropped a message canister asking if we needed supplies, we answered them using cut parachute strips to mark out our numbers and needs. We waited for almost two days hoping they would return, but reluctantly we moved on, worried about the dangers of staying put in one place for too long.

Not long after that incident two of our lads whose feet were in an awful state needed time to rest and bathe their feet in a stream. The order was given to move off, but the two men said they wanted to remain for a short while longer and would attempt to catch us up later. They never returned to the main group and we heard later that they had been killed by the Japanese.

We pushed on again and eventually reached the Chindwin River. Some Burmese boatmen ferried us across near Tamanthi which was occupied by the enemy at that time. We marched quickly westward and came to an Assam Rifles outpost. Here we shaved off our beards which showed us how thin we had become, losing two or three stones in weight. After a few days rest in the camp we set off again, this time knowing we were safe.

Remarkably this seemed to make matters worse for some of the men. Our incentive to keep going was no longer there, physiologically we were in a poorer state and many of the lads health began to go down hill. Eventually we hit the road and were transported to the hospital at Kohima. It was here that Lieutenant Pickering and Private Sullivan sadly died, after all we had been through it was heartbreaking."

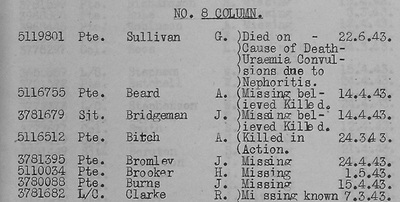

In the official notifications of those recorded as 'missing in action' from Column 8 in 1943, George Sullivan's cause of death was stated as 'uraemia convulsions due to nephritis.' In layman's terms George's kidneys had failed, probably due to the lack of good clean drinking water available and combined with the exhaustive state of his body after his arduous experiences on Operation Longcloth. As mentioned previously, he died in Kohima General Hospital a few short weeks after making it back safely to India.

In May 2013 I was extremely fortunate to receive an email contact from Lee Underwood, the grandson of Pte. George Sullivan. This is what Lee had to say:

I found your site while searching for information about my grandfather, Pte. 5119081 George Sullivan and noticed that you have a photo of his memorial at Kohima. Fascinating. Although my gran, his widow, remarried a couple of times and my Mum, his daughter was only 2 when he died, I've always been interested in his story. It was my gran's recent death that prompted me to start researching.

Unfortunately it was something she never discussed and my Mum passed away before we ever got to discuss it fully. Lance Corporal George Bell's account which mentions my grandfather left me wanting to know whether there was any more information available. I have some items in the family archive including his medals and some paperwork relating to his grave but have never followed them up before now. I am happy to provide copies of these documents if they are useful to your research. Thanks and congratulations on a great site.

A few weeks later Lee sent me the following email and as promised some of the papers relating to George and his time in WW2.

As I said I have a number of documents relating to George, a number of which are attached:

From these I have gleaned the following;

George was born 10th March 1916 and his birth was registered at Paddington Register Office. At the time of his marriage to my Gran in 1940 their address is recorded as Bentworth Road (opposite Hammersmith Hospital). His profession is quoted as 'Butcher's Assistant'. Just under a year later on my Mum's birth certificate he is recorded as a 'Butcher Journeyman', but his service number is also recorded along with the rank of Private in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

Whether he was conscripted or volunteered and why he went into the Warwickshire's I have no idea, but then I don't really know much about how the Army works in that respect. Any tips you could give about finding out would be useful.

In chronological order the next document I have is the notification of his death, in which he is recorded as a member of the 13th Kings Regiment. How he got to India and how he was transferred to the Kings I have no idea. After tracking down his burial site to Kohima from the War Graves Commission website (although the information was in my possession all the time had I realised it) and then from that finding your website, brings me up to date.

There is a lot more I'd like to learn about George's experience and I've started reading your book recommendation. Any gaps you're able to fill in or pointers you can give would be useful. I've attached a few of the documents which are most relevant and some perhaps of a more historical interest. His medals are the 1939-45 Star, Burma Star, Defence Medal and the War Medal and are identical to those pictured on your website.

Many thanks once again.

Lee Underwood

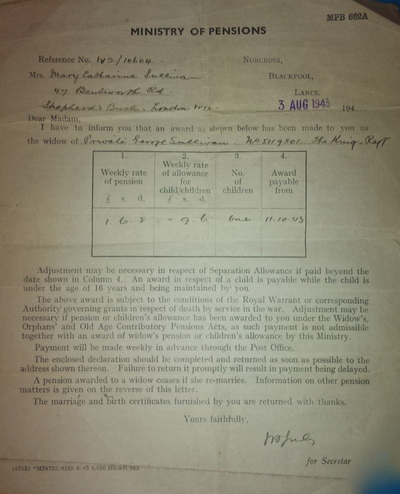

The documents Lee sent over were very much of interest to me, as they filled in so many of the gaps I had about my own grandfather and his WW2 journey. For instance, the notifications from the Imperial War Graves Commission and how they approached bereaved families with information concerning the allocation of graves and memorials, proved invaluable. Probably, most interesting of all was the war widows pension details. These showed a weekly payment (after confirmation of death) of one pound, six shillings and eight pence to the widow, with a supplement of nine shillings and six pence for one child.

Lee's grandmother, Mary, started to receive these payments some twelve weeks after George's sad passing at Kohima General Hospital. However, because my grandfather was presumed to have been a prisoner of war, my own grandmother did not receive any such payments until his death was confirmed when Rangoon Jail was liberated in May 1945, even though he had in fact perished five days before George Sullivan in June 1943.

Seen below are some of the documents Lee sent over, along with other relevant images in relation to George Sullivan and his time in India and Burma. Please click on any of the images to bring them forward on the page.

"After taking another supply drop, the decision was made to split up into smaller dispersal parties. Some headed for China, while others stayed together and marched due west. Our party under Lieutenant Pearce, about fifty strong, went north-north-west. Before splitting up we shook hands with all our pals in the other groups, several of them we would never see again. Our party included three officers and two Burmese who were in the Burma Rifles and could speak both English and Burmese. They saved our lives, as they were able to enter villages and obtain information about the whereabouts of the Japs. Apart from the one occasion when they got drunk as newts in one village on rice wine.

After leaving the other groups we made for a small village on the Irrawaddy, only to find as we arrived there that the village had been moved to the other bank a few years before. It was then that we realised that our maps had been drawn up in 1912 and were extremely out of date. We made off for another village further towards the north, but got bogged down in thick jungle and so decided to halt and sleep for a few hours. This turned out to be a stroke of good luck, as it transpired that a Jap patrol had spent the night in the village and had only just moved out. From that moment on I always felt that someone above was looking out for us.

As soon as it was dark we started to cross over in a boat with a villager rowing, the water came right up to the top of the sides, I couldn't swim and so was pleased to reach the other side still afloat. Throughout the night the boat crossed and re-crossed the river until everyone was over. By that time we had no way of contacting our air base and had to rely on local villages for food, boiled rice with no salt for breakfast, lunch and dinner! We had also become lousy and our clothes were disgusting. Leeches became a real problem, they got everywhere and I mean everywhere. We were told to use a lighted cigarette to burn them off, but this advice presumed we had cigarettes, which by then we did not. At one stage the heavy smokers amongst our group bought local tobacco from a village and used one of the lads bible for roll-up papers.

We marched sometimes 20 miles in a day, re-crossing the railway and two more minor rivers. One day we came across a Burmese man who could speak English, his story did not ring true to us and so we kept him with us under guard. After collecting more rice in the next village the headman warned us that this man had recently been in the company of a Jap patrol. It was decide that it was too dangerous to let him go and that he should be shot. My section took him away from the main group and one of the Burma Rifle soldiers shot him through the head. This left us with the feeling of being judge, jury and executioner.

We slogged on for a few more days, by which time our food supplies had completely run out. I brewed up with a tea bag that must have been used at least twenty times before. Around midday we were walking along a dried-up river bed when we saw some parachutes caught up in a group of trees. We approached them carefully concerned it might be a Jap ambush or booby trap, but it was a definite ration dropping, presumably for another of our parties. The packs gave us eight days rations per man, exactly eight days later we were in a small village when a British plane came over and spotted us on the ground. They dropped a message canister asking if we needed supplies, we answered them using cut parachute strips to mark out our numbers and needs. We waited for almost two days hoping they would return, but reluctantly we moved on, worried about the dangers of staying put in one place for too long.

Not long after that incident two of our lads whose feet were in an awful state needed time to rest and bathe their feet in a stream. The order was given to move off, but the two men said they wanted to remain for a short while longer and would attempt to catch us up later. They never returned to the main group and we heard later that they had been killed by the Japanese.

We pushed on again and eventually reached the Chindwin River. Some Burmese boatmen ferried us across near Tamanthi which was occupied by the enemy at that time. We marched quickly westward and came to an Assam Rifles outpost. Here we shaved off our beards which showed us how thin we had become, losing two or three stones in weight. After a few days rest in the camp we set off again, this time knowing we were safe.

Remarkably this seemed to make matters worse for some of the men. Our incentive to keep going was no longer there, physiologically we were in a poorer state and many of the lads health began to go down hill. Eventually we hit the road and were transported to the hospital at Kohima. It was here that Lieutenant Pickering and Private Sullivan sadly died, after all we had been through it was heartbreaking."

In the official notifications of those recorded as 'missing in action' from Column 8 in 1943, George Sullivan's cause of death was stated as 'uraemia convulsions due to nephritis.' In layman's terms George's kidneys had failed, probably due to the lack of good clean drinking water available and combined with the exhaustive state of his body after his arduous experiences on Operation Longcloth. As mentioned previously, he died in Kohima General Hospital a few short weeks after making it back safely to India.

In May 2013 I was extremely fortunate to receive an email contact from Lee Underwood, the grandson of Pte. George Sullivan. This is what Lee had to say:

I found your site while searching for information about my grandfather, Pte. 5119081 George Sullivan and noticed that you have a photo of his memorial at Kohima. Fascinating. Although my gran, his widow, remarried a couple of times and my Mum, his daughter was only 2 when he died, I've always been interested in his story. It was my gran's recent death that prompted me to start researching.

Unfortunately it was something she never discussed and my Mum passed away before we ever got to discuss it fully. Lance Corporal George Bell's account which mentions my grandfather left me wanting to know whether there was any more information available. I have some items in the family archive including his medals and some paperwork relating to his grave but have never followed them up before now. I am happy to provide copies of these documents if they are useful to your research. Thanks and congratulations on a great site.

A few weeks later Lee sent me the following email and as promised some of the papers relating to George and his time in WW2.

As I said I have a number of documents relating to George, a number of which are attached:

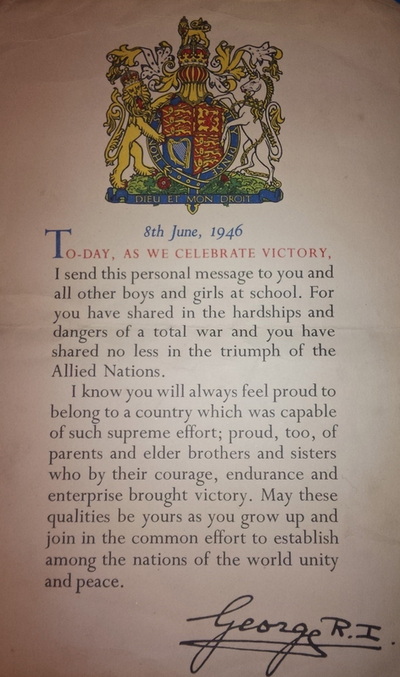

- his birth certificate

- his marriage certificate

- notification of his death

- letter from the War Graves Commission relating to his memorial

- letter to my gran with details of her war widow's pension

- picture of his temporary grave marker

- scroll of thanks from King George to schoolchildren (presumably given to my Mum).

From these I have gleaned the following;

George was born 10th March 1916 and his birth was registered at Paddington Register Office. At the time of his marriage to my Gran in 1940 their address is recorded as Bentworth Road (opposite Hammersmith Hospital). His profession is quoted as 'Butcher's Assistant'. Just under a year later on my Mum's birth certificate he is recorded as a 'Butcher Journeyman', but his service number is also recorded along with the rank of Private in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

Whether he was conscripted or volunteered and why he went into the Warwickshire's I have no idea, but then I don't really know much about how the Army works in that respect. Any tips you could give about finding out would be useful.

In chronological order the next document I have is the notification of his death, in which he is recorded as a member of the 13th Kings Regiment. How he got to India and how he was transferred to the Kings I have no idea. After tracking down his burial site to Kohima from the War Graves Commission website (although the information was in my possession all the time had I realised it) and then from that finding your website, brings me up to date.

There is a lot more I'd like to learn about George's experience and I've started reading your book recommendation. Any gaps you're able to fill in or pointers you can give would be useful. I've attached a few of the documents which are most relevant and some perhaps of a more historical interest. His medals are the 1939-45 Star, Burma Star, Defence Medal and the War Medal and are identical to those pictured on your website.

Many thanks once again.

Lee Underwood

The documents Lee sent over were very much of interest to me, as they filled in so many of the gaps I had about my own grandfather and his WW2 journey. For instance, the notifications from the Imperial War Graves Commission and how they approached bereaved families with information concerning the allocation of graves and memorials, proved invaluable. Probably, most interesting of all was the war widows pension details. These showed a weekly payment (after confirmation of death) of one pound, six shillings and eight pence to the widow, with a supplement of nine shillings and six pence for one child.

Lee's grandmother, Mary, started to receive these payments some twelve weeks after George's sad passing at Kohima General Hospital. However, because my grandfather was presumed to have been a prisoner of war, my own grandmother did not receive any such payments until his death was confirmed when Rangoon Jail was liberated in May 1945, even though he had in fact perished five days before George Sullivan in June 1943.

Seen below are some of the documents Lee sent over, along with other relevant images in relation to George Sullivan and his time in India and Burma. Please click on any of the images to bring them forward on the page.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank Lee Underwood for all his help with this story and for allowing me to use some of the personal family documents in this presentation.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, September 2014.

Copyright © Steve Fogden, September 2014.