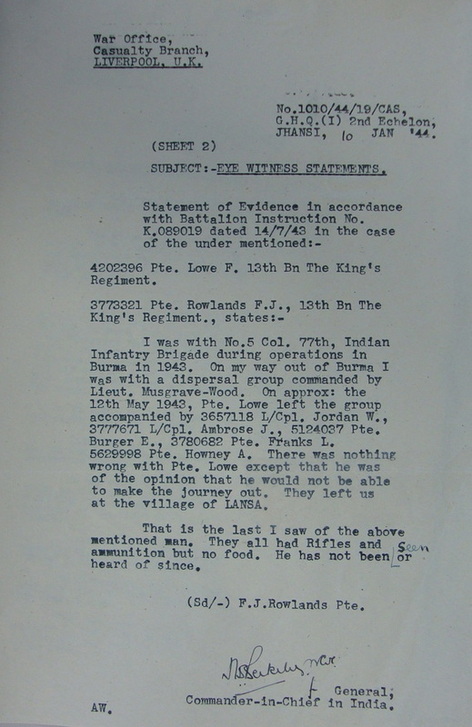

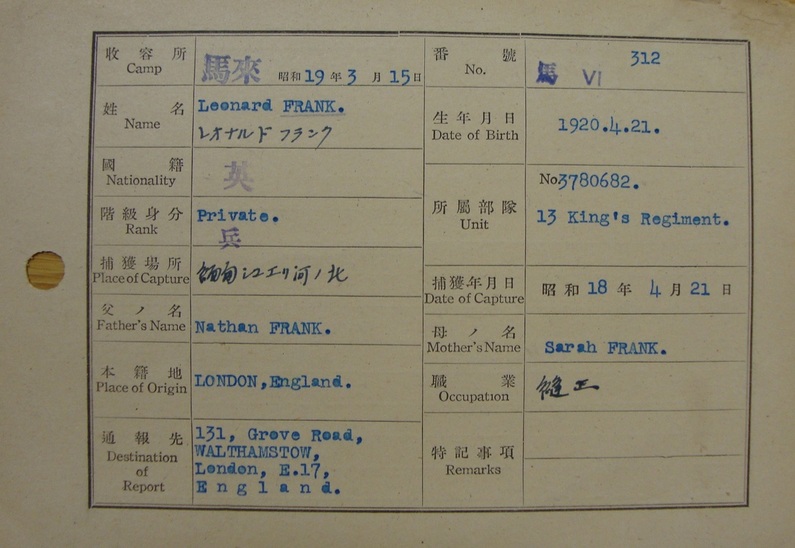

Pte. 3780682 Leonard Frank

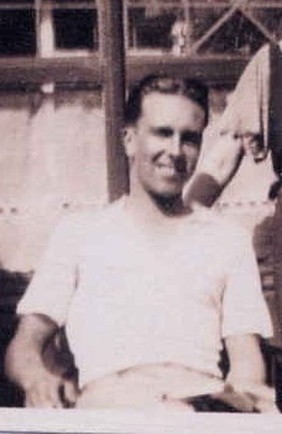

Pte. Leon Frank at Saugor during Chindit training.

Pte. 3780683 Leonard Frank was a muleteer in Major Kenneth Gilkes's Column 7 during Operation Longcloth. He served in Platoon 13 and often under the command of Captain W.B.E. Petersen, a Danish officer with a Special Forces background, who had worked in the rubber plantations of Malaya shortly before the war in Europe began.

Leon, as he was always called by his comrades, was born on 20th April 1920 in Green Dragon Yard, Shoreditch in the East End of London, and was the son of Eastern European parents of the Jewish faith, who had made their living in the tailoring business. Leon had helped his father in the trade, mostly running errands for him from the family home.

After war was declared and following a short spell serving with the A.R.P., Leon decided to 'join up' and in June 1940 was posted to the 13th Battalion, the King's Liverpool Regiment, at their Jordan Hill barracks in Glasgow. It was whilst in Glasgow that Leon met his future wife, Sylvia.

In the early days of my research into Operation Longcloth I had often seen Leon's name mentioned in books or papers. He had left an audio recording with the Imperial War Museum in 1995 and had spoken to well known authors interested in the Burma Campaign, writers such as Phil Chinnery and Martin Sugarman. It was clear that Leon was determined to ensure that his experiences and those of the men with whom he fought should not be forgotten. I for one will be eternally grateful for his effort in doing so.

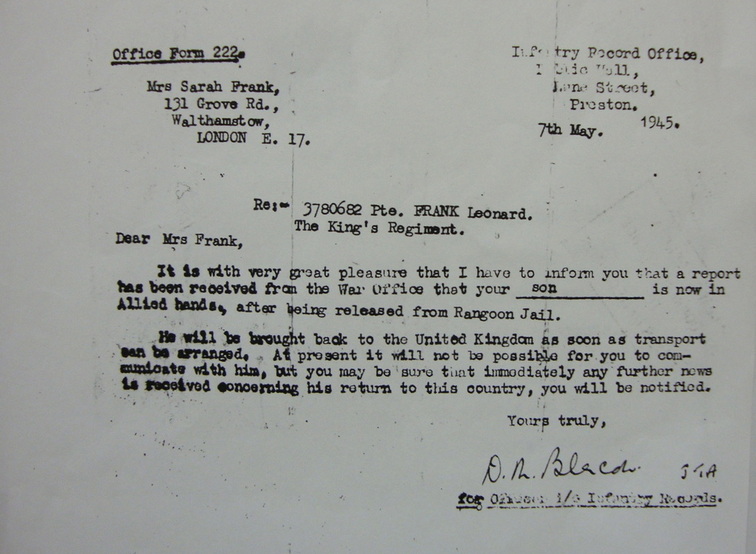

My research began in July 2006, and so, I sadly missed Leon by just three short years, after he died in 2003 aged 83. When I took the opportunity to listen to his audio recording at the IWM I was moved by his compassion and the care he took to recount his time in Burma, especially the years in Rangoon Jail. As I sat there in the museum's reading room, listening to his soft, gentle voice, I did not know how vitally important his story would be in regard to that of my own grandfather, Arthur Howney.

I am not going to repeat here, all the information about Leon that already features within the pages of this website. Instead, I am going to let the man himself tell you in his own words what happened during those difficult months and years.

I would like to thank the following for their help and support in being able to bring Leon's story to these pages: Martin Sugarman, Phil Chinnery, Sylvia G. Frank (Leon's wife) and the Jewish Military Museum in London. Here are the relevant links to the places where Leon has left his written legacy to his Chindit comrades:

The Jewish Military Museum

http://www.thejmm.org.uk/home

The Imperial War Museum

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80015277

On this website:

The story of Arthur Leslie Howney

James Ambrose and Bob Jordan. (second and third stories on the page).

Sylvia's letter. Fourth article on the page.

Leon's words can also be read within the pages of Phil Chinnery's book, 'Wingate's Lost Brigade'.

Leon, as he was always called by his comrades, was born on 20th April 1920 in Green Dragon Yard, Shoreditch in the East End of London, and was the son of Eastern European parents of the Jewish faith, who had made their living in the tailoring business. Leon had helped his father in the trade, mostly running errands for him from the family home.

After war was declared and following a short spell serving with the A.R.P., Leon decided to 'join up' and in June 1940 was posted to the 13th Battalion, the King's Liverpool Regiment, at their Jordan Hill barracks in Glasgow. It was whilst in Glasgow that Leon met his future wife, Sylvia.

In the early days of my research into Operation Longcloth I had often seen Leon's name mentioned in books or papers. He had left an audio recording with the Imperial War Museum in 1995 and had spoken to well known authors interested in the Burma Campaign, writers such as Phil Chinnery and Martin Sugarman. It was clear that Leon was determined to ensure that his experiences and those of the men with whom he fought should not be forgotten. I for one will be eternally grateful for his effort in doing so.

My research began in July 2006, and so, I sadly missed Leon by just three short years, after he died in 2003 aged 83. When I took the opportunity to listen to his audio recording at the IWM I was moved by his compassion and the care he took to recount his time in Burma, especially the years in Rangoon Jail. As I sat there in the museum's reading room, listening to his soft, gentle voice, I did not know how vitally important his story would be in regard to that of my own grandfather, Arthur Howney.

I am not going to repeat here, all the information about Leon that already features within the pages of this website. Instead, I am going to let the man himself tell you in his own words what happened during those difficult months and years.

I would like to thank the following for their help and support in being able to bring Leon's story to these pages: Martin Sugarman, Phil Chinnery, Sylvia G. Frank (Leon's wife) and the Jewish Military Museum in London. Here are the relevant links to the places where Leon has left his written legacy to his Chindit comrades:

The Jewish Military Museum

http://www.thejmm.org.uk/home

The Imperial War Museum

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80015277

On this website:

The story of Arthur Leslie Howney

James Ambrose and Bob Jordan. (second and third stories on the page).

Sylvia's letter. Fourth article on the page.

Leon's words can also be read within the pages of Phil Chinnery's book, 'Wingate's Lost Brigade'.

Leon Frank's story is presented courtesy of Martin Sugarman and the Jewish Military Museum in London. I have left his words almost untouched, with only the odd phrase or an explanation of some of the script added.

Pte. Leon Frank-A Man's Will to Survive

This story is a true one. There is nothing added and nothing taken away. It's a story of hardship, endurance, courage, privation, brutality and above all of comradeship and understanding which I think helped us obtain the will to survive.

I was just an ordinary British soldier doing my job like many others the best way I knew how. My unit was 13th Battalion King's Liverpool Regiment, which formed part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, which was later known as the Chindits. I was in the very first Chindit Expedition in 1943 - code name 'Longcloth'. This is my story.

It all began for me way back in 1940 when, like many other young men, I was called to the colours. I joined up in June 1940. I was stationed in Glasgow which is where I met my wife. There was the usual initial training, coastal defence duties and inevitably the embarkation leave.

We all recall the day of December 7th 1941. That was for me a tremendously important day. It was the day our convoy left Liverpool for God knows where. It was also the day the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour.

We had a pleasant cruise. We should have gone to Cape Town but I believe there was a submarine scare and we were diverted to Durban (where they would have been welcomed by the opera singer Perla Siedle-Gibson, known as the 'Lady in White', who used to sing to the newly arrived troopships as they docked). We had a very pleasant five days in Durban and it was quite surprising to go through the streets of this beautiful city and see the shops full of goods that we had all not seen for some time at home and with all the lights on. As a matter of fact, when I went to Clarewood transit camp and asked the cook for some bread and butter and jam he just tossed me a loaf of bread, a tin of butter and a tin of jam. I was absolutely amazed.

Anyway, after our very nice stay there our convoy made its way to India. Half the convoy went to Singapore, I believe right into the hands of the Japanese. We arrived in Bombay in February 1942. We went to the stores on the docks and traded in our pith helmets which we had taken all the way from Britain to get ourselves some bush hats.

From there it took us three days on a train to Secunderabad, the second city in the state of Hydrabad. You must have heard of the Nizam of Hydrabad. We settled down to some pleasant garrison duties and I became a regimental policeman. I was told I volunteered for it!

Pte. Leon Frank-A Man's Will to Survive

This story is a true one. There is nothing added and nothing taken away. It's a story of hardship, endurance, courage, privation, brutality and above all of comradeship and understanding which I think helped us obtain the will to survive.

I was just an ordinary British soldier doing my job like many others the best way I knew how. My unit was 13th Battalion King's Liverpool Regiment, which formed part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, which was later known as the Chindits. I was in the very first Chindit Expedition in 1943 - code name 'Longcloth'. This is my story.

It all began for me way back in 1940 when, like many other young men, I was called to the colours. I joined up in June 1940. I was stationed in Glasgow which is where I met my wife. There was the usual initial training, coastal defence duties and inevitably the embarkation leave.

We all recall the day of December 7th 1941. That was for me a tremendously important day. It was the day our convoy left Liverpool for God knows where. It was also the day the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour.

We had a pleasant cruise. We should have gone to Cape Town but I believe there was a submarine scare and we were diverted to Durban (where they would have been welcomed by the opera singer Perla Siedle-Gibson, known as the 'Lady in White', who used to sing to the newly arrived troopships as they docked). We had a very pleasant five days in Durban and it was quite surprising to go through the streets of this beautiful city and see the shops full of goods that we had all not seen for some time at home and with all the lights on. As a matter of fact, when I went to Clarewood transit camp and asked the cook for some bread and butter and jam he just tossed me a loaf of bread, a tin of butter and a tin of jam. I was absolutely amazed.

Anyway, after our very nice stay there our convoy made its way to India. Half the convoy went to Singapore, I believe right into the hands of the Japanese. We arrived in Bombay in February 1942. We went to the stores on the docks and traded in our pith helmets which we had taken all the way from Britain to get ourselves some bush hats.

From there it took us three days on a train to Secunderabad, the second city in the state of Hydrabad. You must have heard of the Nizam of Hydrabad. We settled down to some pleasant garrison duties and I became a regimental policeman. I was told I volunteered for it!

Perla Siedle-Gibson. 'The Lady in White' at Durban.

I must tell you an amusing incident during my duty there. We had a canteen, we called it the coffee shop, and every Friday night they would hold a dance for soldiers and the local girls, and residents.

We'd recently received a new intake of Cameronian troops and I believe a lot of them had been in trouble and had been on detention. Of course when they came ashore and re-stationed at our barracks, Meadows Barracks, they were all released but some of them still bore the semblances of their misdemeanours - the close cropped hair and such. Anyway, one night I was on duty at the coffee shop with a dance in progress and this burly Cameronian - he must have been well over six feet tall and was slightly the worse for drink - approached an Anglo-Indian girl and asked her for a dance. Evidently, seeing the state he was in she refused, so he promptly took a bottle and hit her on the head with it.

Sergeant Evans, the Welsh police sergeant, turned to me and said "Private Frank, arrest that man". You know how big I am (5'3") and I've told you how big he was. Without further ado I whipped my arm-band off, went over to him, put my arm round his shoulders, full of sympathy, and told him I knew a far better place where he could enjoy himself. I just gently led him to the police cells and put him away for the night.

That's just one of the more pleasant and funny things that happened. Well eventually, later in 1942, Wingate caught up with us. Later on I learned that it was his intention to use ordinary troops, not front line troops, just ordinary conscripts like we were, to prove that we could be as good or better than the Japanese. Of course we didn't know it at the time.

Jungle Training

We went into jungle training. We'd ceased to be the 13th Bn. The King's Liverpool Regiment. We became part of the 77th Infantry Brigade which comprised a lot of regiments. There were Gurkhas and of course there were mules and horses, often there were bullocks. In actual fact we were known as Wingate's Circus.

We trained in mud, we slept in mud and we ate mud. The training was very tough. We did river crossings, marching through the jungle, finding our way by the stars, it was part of the Commando training. We had one very sad thing that happened there. There was a Jewish Officer named Lt. Neville Nathan Saffer. My platoon was 13 Platoon and next to me was 14 Platoon, a few yards from each other, and we were each standing in a small circle for rifle inspection. You bring your rifle to the up position, first ejecting all your shells, and the officer in charge of the inspection would come round and look down the rifle barrel to see if it was clean.

We had almost completed our inspection when all of a sudden a shot rang out. We turned round at 14 Platoon. Lt. Saffer, the inspecting officer, had looked down the barrel of the rifle and the soldier concerned had left one shell in the breach. He pulled the trigger as the officer looked down the barrel and the bullet took him right through the cheek and out of the back of his head. He dropped like a stack. He was dead instantly. That was our first casualty and we were very shocked. Everyone was shocked. I think the soldier who did it had to be put in hospital. It was an accident - carelessness, but nevertheless an accident. We buried him and we put a cross above him but one of the soldiers said "Draw him the Star of David on the cross". That was a sad incident.

After training we took a steamer up the River Bramaputra to Manipur, from where our only transport was then our feet. We marched 300 miles to the Burmese border by which time we had adopted our usual method of travelling - single file in a snake column. It took us ten days to do the march winding through the mountains. You often saw the end of the column facing you as you at the front of the column were going the other way. It really was just like a snake.

During the previous year, 1942, there had been the great retreat from Burma as the victorious Japanese advanced, and as we walked through Kohima we saw lorries and other motor transport stranded at the side of the road with skeletons still in the trucks. The petrol had run out and they had just died at the wayside. It was very sad to see dereliction on such a scale.

We'd recently received a new intake of Cameronian troops and I believe a lot of them had been in trouble and had been on detention. Of course when they came ashore and re-stationed at our barracks, Meadows Barracks, they were all released but some of them still bore the semblances of their misdemeanours - the close cropped hair and such. Anyway, one night I was on duty at the coffee shop with a dance in progress and this burly Cameronian - he must have been well over six feet tall and was slightly the worse for drink - approached an Anglo-Indian girl and asked her for a dance. Evidently, seeing the state he was in she refused, so he promptly took a bottle and hit her on the head with it.

Sergeant Evans, the Welsh police sergeant, turned to me and said "Private Frank, arrest that man". You know how big I am (5'3") and I've told you how big he was. Without further ado I whipped my arm-band off, went over to him, put my arm round his shoulders, full of sympathy, and told him I knew a far better place where he could enjoy himself. I just gently led him to the police cells and put him away for the night.

That's just one of the more pleasant and funny things that happened. Well eventually, later in 1942, Wingate caught up with us. Later on I learned that it was his intention to use ordinary troops, not front line troops, just ordinary conscripts like we were, to prove that we could be as good or better than the Japanese. Of course we didn't know it at the time.

Jungle Training

We went into jungle training. We'd ceased to be the 13th Bn. The King's Liverpool Regiment. We became part of the 77th Infantry Brigade which comprised a lot of regiments. There were Gurkhas and of course there were mules and horses, often there were bullocks. In actual fact we were known as Wingate's Circus.

We trained in mud, we slept in mud and we ate mud. The training was very tough. We did river crossings, marching through the jungle, finding our way by the stars, it was part of the Commando training. We had one very sad thing that happened there. There was a Jewish Officer named Lt. Neville Nathan Saffer. My platoon was 13 Platoon and next to me was 14 Platoon, a few yards from each other, and we were each standing in a small circle for rifle inspection. You bring your rifle to the up position, first ejecting all your shells, and the officer in charge of the inspection would come round and look down the rifle barrel to see if it was clean.

We had almost completed our inspection when all of a sudden a shot rang out. We turned round at 14 Platoon. Lt. Saffer, the inspecting officer, had looked down the barrel of the rifle and the soldier concerned had left one shell in the breach. He pulled the trigger as the officer looked down the barrel and the bullet took him right through the cheek and out of the back of his head. He dropped like a stack. He was dead instantly. That was our first casualty and we were very shocked. Everyone was shocked. I think the soldier who did it had to be put in hospital. It was an accident - carelessness, but nevertheless an accident. We buried him and we put a cross above him but one of the soldiers said "Draw him the Star of David on the cross". That was a sad incident.

After training we took a steamer up the River Bramaputra to Manipur, from where our only transport was then our feet. We marched 300 miles to the Burmese border by which time we had adopted our usual method of travelling - single file in a snake column. It took us ten days to do the march winding through the mountains. You often saw the end of the column facing you as you at the front of the column were going the other way. It really was just like a snake.

During the previous year, 1942, there had been the great retreat from Burma as the victorious Japanese advanced, and as we walked through Kohima we saw lorries and other motor transport stranded at the side of the road with skeletons still in the trucks. The petrol had run out and they had just died at the wayside. It was very sad to see dereliction on such a scale.

Springboard into Burma

We continued into Imphal which was to be the springboard for our entry into Burma. Before we went in we were given speeches by Lord Wavell, the American General Stillwell (Vinegar Joe), and Brigadier Wingate. They all wished us God speed, told us what we had to do and gave us encouragement. Wingate said to us in his speech "If you want to leave step forward now, because we want no rotten apples on this tree" and told us that if any person felt sick or unable to continue during the operation they would be left at the wayside. This was a very serious operation and our only supplies would come by air.

There were many doubts in my mind, as I'm sure there must have been in many others. I looked around and saw all my friends whom I'd known from the beginning when we arrived in Glasgow as conscripts. I thought "To hell with this. If you back out now you'll only end up with another unit and go in some other action. At least here you are with people you know and trust and can rely on". No man stepped forward.

We went on through the Naga Hills to the River Chindwin which became like a mini Dunkirk. We had boats gathered, some of us swam, but eventually the whole seven columns were across.

The columns were numbered one to eight, but No. 6 column had been so decimated by sickness that the men had been dispersed throughout the other seven columns. There were about 2,500 men altogether, although each column worked independently of the others. We marauded through North Eastern Burma attacking isolated Japanese camps, blowing up dumps, attacking railway lines and so on. In between the actions we had to face the terrible enemy of the natural conditions. It was absolutely impenetrable. You could go through the jungle and never see the light of day because of the foliage. You would have to hack your way through with dahs, the long Burmese two-sided knives. Then there was the cold of the night and the heat of the day, and being entirely dependent on air supplies and ration drops. Whilst we were in the mountains we were pretty safe from the Japs and we'd get the ration drops. Quite a bit landed in the trees but nevertheless we were safe. But when we got onto flat ground we found that invariably we'd be mortared by the Japanese and have to beat a hasty retreat because our policy was only to hit and run.

One night thirty men from my Column, No. 7, and thirty men from Headquarters Column were ordered to set up a road block at a certain spot. We set up the road block but it was a very uneventful night. We were due to rendezvous with our respective columns the next day and what happened I don't know, but somehow we missed the rendezvous and as there should have been an air drop that day we also missed receiving our rations.

We continued into Imphal which was to be the springboard for our entry into Burma. Before we went in we were given speeches by Lord Wavell, the American General Stillwell (Vinegar Joe), and Brigadier Wingate. They all wished us God speed, told us what we had to do and gave us encouragement. Wingate said to us in his speech "If you want to leave step forward now, because we want no rotten apples on this tree" and told us that if any person felt sick or unable to continue during the operation they would be left at the wayside. This was a very serious operation and our only supplies would come by air.

There were many doubts in my mind, as I'm sure there must have been in many others. I looked around and saw all my friends whom I'd known from the beginning when we arrived in Glasgow as conscripts. I thought "To hell with this. If you back out now you'll only end up with another unit and go in some other action. At least here you are with people you know and trust and can rely on". No man stepped forward.

We went on through the Naga Hills to the River Chindwin which became like a mini Dunkirk. We had boats gathered, some of us swam, but eventually the whole seven columns were across.

The columns were numbered one to eight, but No. 6 column had been so decimated by sickness that the men had been dispersed throughout the other seven columns. There were about 2,500 men altogether, although each column worked independently of the others. We marauded through North Eastern Burma attacking isolated Japanese camps, blowing up dumps, attacking railway lines and so on. In between the actions we had to face the terrible enemy of the natural conditions. It was absolutely impenetrable. You could go through the jungle and never see the light of day because of the foliage. You would have to hack your way through with dahs, the long Burmese two-sided knives. Then there was the cold of the night and the heat of the day, and being entirely dependent on air supplies and ration drops. Whilst we were in the mountains we were pretty safe from the Japs and we'd get the ration drops. Quite a bit landed in the trees but nevertheless we were safe. But when we got onto flat ground we found that invariably we'd be mortared by the Japanese and have to beat a hasty retreat because our policy was only to hit and run.

One night thirty men from my Column, No. 7, and thirty men from Headquarters Column were ordered to set up a road block at a certain spot. We set up the road block but it was a very uneventful night. We were due to rendezvous with our respective columns the next day and what happened I don't know, but somehow we missed the rendezvous and as there should have been an air drop that day we also missed receiving our rations.

Captain W.B.E. Petersen, commander of the break away platoon.

Droppings lead the way

We walked for some time until we found elephant droppings and one or two wrappers from ration containers and realised that the only column with elephants was No. 3 Column, the Gurkha Column, under Major Calvert. So for three days sixty of us tracked the column. Suddenly we heard the sound of machine gun fire and following the sound we came upon Major Calvert's Column busily engaged in attacking a railway station. He was absolutely delighted to see sixty British soldiers and we joined in the attack. We were shooting up the railway station when the Japanese Force returned in trucks. We beat a hasty retreat with them firing after us.

We returned to the jungle and Major Calvert radioed in about our position. He was due for a ration drop that day and ordered sixty extra rations, but just before the drop was due there was a radio message that we were to rejoin our own column which was only twenty miles away. Column 3 were just about to roast a bullock and even though it had barely touched the fire we just grabbed some lumps of almost raw meat and ate them as we proceeded to rejoin our unit. This twenty miles took three days winding through mountains and jungle.

Eventually our group of thirty (by then we 'd split up and Headquarters Column had gone back to their column) found some scouts who had come to meet us. They said they'd been ambushed and the columns had all made their way to the jungle and they were left to guide us back.

We got back to our column and resumed the operations. We travelled eastwards and went across the Irrawaddy and continued to do our sabotage work. I won't go into detail. The order then came through that our work was done and we were to return to India. We came back and tried to cross the Irrawaddy. The local Burmese got some boats for us. Incidentally, I must tell you that the Lower Burmans betrayed a lot of our boys as I'll tell you later on. One of the boats had almost got across when it was fired on from the other side. You can imagine what happened to this boat stuck in the middle there. They were absolutely decimated. So we knew that the way back was blocked because by then the Japanese were pin-pointing our positions by our air droppings.

We walked for some time until we found elephant droppings and one or two wrappers from ration containers and realised that the only column with elephants was No. 3 Column, the Gurkha Column, under Major Calvert. So for three days sixty of us tracked the column. Suddenly we heard the sound of machine gun fire and following the sound we came upon Major Calvert's Column busily engaged in attacking a railway station. He was absolutely delighted to see sixty British soldiers and we joined in the attack. We were shooting up the railway station when the Japanese Force returned in trucks. We beat a hasty retreat with them firing after us.

We returned to the jungle and Major Calvert radioed in about our position. He was due for a ration drop that day and ordered sixty extra rations, but just before the drop was due there was a radio message that we were to rejoin our own column which was only twenty miles away. Column 3 were just about to roast a bullock and even though it had barely touched the fire we just grabbed some lumps of almost raw meat and ate them as we proceeded to rejoin our unit. This twenty miles took three days winding through mountains and jungle.

Eventually our group of thirty (by then we 'd split up and Headquarters Column had gone back to their column) found some scouts who had come to meet us. They said they'd been ambushed and the columns had all made their way to the jungle and they were left to guide us back.

We got back to our column and resumed the operations. We travelled eastwards and went across the Irrawaddy and continued to do our sabotage work. I won't go into detail. The order then came through that our work was done and we were to return to India. We came back and tried to cross the Irrawaddy. The local Burmese got some boats for us. Incidentally, I must tell you that the Lower Burmans betrayed a lot of our boys as I'll tell you later on. One of the boats had almost got across when it was fired on from the other side. You can imagine what happened to this boat stuck in the middle there. They were absolutely decimated. So we knew that the way back was blocked because by then the Japanese were pin-pointing our positions by our air droppings.

Lieutenant J. Musgrave-Wood of the Sherwood Foresters.

Wingate orders column split

The order came from Wingate that we were to split up into small groups, so the column split up into platoon strength, approximately thirty men. I was with a group under Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood from the Sherwood Forrester's and we decided to make our way north to Fort Hertz which was still, of course, in British hands. The idea was that we would take some guides from a village, who would then guide us on to the next village and so on in stepping stones.

We were doing this successfully for a little while and then we had these two guides and what happened was this. lf you can imagine a mountain path going up. Imagine a cross leaning on its side and you're going up the centre of the cross which is a path and either side of the blank space is jungle. The top of the cross, the 'T' of the cross, is a path going beyond at right angles. At this 'T' across the top, as we were going up the path with jungle either side, the two Burmese guides who were leading us, one went left and one went right and disappeared into the jungle, whilst strolling across the 'T' of the cross looking down on us was a Japanese patrol. We just melted into the jungle either side. The Japanese had spotted us but we hoped if we were quiet enough they might go away. One or our chaps, one of the Dennett twins, and for no apparent reason because we already had this knowledge, shouted "Japs". That gave our position away and they started to open fire at us. We literally rolled down the hill.

We didn't run, we just rolled or whatever to get to the bottom or the hill. We did everything we could to put our pursuers off the track. We crossed and re-crossed rivers. We could hear dogs in the distance. They used dogs to track us. Eventually we eluded them but we realised that the game was up. Such a comparatively large party were too obvious a target. So the Lieutenant said it was every man for himself now. Each man had a right to do what he wanted. He was still going north to Fort Hertz. Anybody who wished to go with him could. I and another five men including Lance Corporal Jordan, who had since removed his stripe as he didn't want to be conspicuous as anything else but a private, we decided to go east. We thought if we could go east far enough we could get into China.

We marched for a couple or days and became like bandits. We would go into villages and demand rice at gun-point. We must have looked a pretty tough sight. We were bearded, we had grenades and rifles. We found a valley with strange fruit on the trees, I don't know what, but we ate this and rested up for a couple of days and then we proceeded east again. We came to a hillside and there was a hut on the side of the hill and there was a small stream below and some wild tomatoes or some such fruit growing. We looked in the hut and saw some rice husks on the floor, so we beat out the rice and made ourselves a meal and settled down to get a rest. I don't know who should have been on guard, somebody or other should have been, but by this time you must realise that we were pretty well exhausted. We'd had enough. We were just exhausted.

Captured by Japs

The next thing we knew was the door burst open and in came a Jap soldier with a bayonet. He caught Lance Corporal Jordan who didn't have his insignia on his arm, in his hand and was just going to have another go when the Japanese officer called him off. They motioned for us to go outside and we stood outside in a line, the six of us, and there facing us was a half moon circle of Japanese soldiers, armed, and the centre one had a machine gun pointed at us. I remember turning round and saying "The bastards are going to shoot us in cold blood." But strangely enough we were fortunate in our captors. You see we were captured by the Imperial Guard and they were professional soldiers. Anyway they tied our hands, took our possessions off us, anything we had, and then they led us to their jungle camp.

We were interrogated, but there was nothing we could tell them, in fact it was just a formality, because they knew exactly what had happened, because they had previously sent over aircraft to the area where we'd been operating and dropped leaflets, saying that we had done our job, that there was no chance of getting out and we should surrender to the Imperial Japanese Army. It was propaganda. Anyway with this particular lot we weren't treated too bad.

They fed us and they gave us various jobs to do around the camp. It was an interim stop. As a matter of fact they made me a batman, evidently there were some Japanese Officers and the Japanese batmen were one short. I had to do chores around the camp and I had to sleep in the same place with these other batmen, and when they got their daily ration of jugrri, which is a sort of fudge, and some Burmese cigarettes, they would put a little pile at the place where I slept with them. And this is one of the light-hearted bits I must tell you about, because as I said at the beginning there's nothing added and nothing taken away here. I've got to speak as I find and in every rotten barrel of apples there may be one that survives, in everything that's good there's always something bad or in everything that's bad there's always something good. That's just trying to explain myself.

There was one Japanese soldier there. He could speak English not too badly and he said his name was Tagata. He was a barber in Tokyo and he wanted me to come to his hut for supper that night. I put my hands together and said "I'm a prisoner, I can't accept such an invitation." Evidently he'd obtained permission from his sergeant who guarded me, so under escort I went to his hut that night and he gave me rice and kidneys to eat and chatted to me and said that after the war I'd go to Tokyo and he'd introduce me to his mother and father. I felt quite good over this.

The order came from Wingate that we were to split up into small groups, so the column split up into platoon strength, approximately thirty men. I was with a group under Lieutenant Musgrave-Wood from the Sherwood Forrester's and we decided to make our way north to Fort Hertz which was still, of course, in British hands. The idea was that we would take some guides from a village, who would then guide us on to the next village and so on in stepping stones.

We were doing this successfully for a little while and then we had these two guides and what happened was this. lf you can imagine a mountain path going up. Imagine a cross leaning on its side and you're going up the centre of the cross which is a path and either side of the blank space is jungle. The top of the cross, the 'T' of the cross, is a path going beyond at right angles. At this 'T' across the top, as we were going up the path with jungle either side, the two Burmese guides who were leading us, one went left and one went right and disappeared into the jungle, whilst strolling across the 'T' of the cross looking down on us was a Japanese patrol. We just melted into the jungle either side. The Japanese had spotted us but we hoped if we were quiet enough they might go away. One or our chaps, one of the Dennett twins, and for no apparent reason because we already had this knowledge, shouted "Japs". That gave our position away and they started to open fire at us. We literally rolled down the hill.

We didn't run, we just rolled or whatever to get to the bottom or the hill. We did everything we could to put our pursuers off the track. We crossed and re-crossed rivers. We could hear dogs in the distance. They used dogs to track us. Eventually we eluded them but we realised that the game was up. Such a comparatively large party were too obvious a target. So the Lieutenant said it was every man for himself now. Each man had a right to do what he wanted. He was still going north to Fort Hertz. Anybody who wished to go with him could. I and another five men including Lance Corporal Jordan, who had since removed his stripe as he didn't want to be conspicuous as anything else but a private, we decided to go east. We thought if we could go east far enough we could get into China.

We marched for a couple or days and became like bandits. We would go into villages and demand rice at gun-point. We must have looked a pretty tough sight. We were bearded, we had grenades and rifles. We found a valley with strange fruit on the trees, I don't know what, but we ate this and rested up for a couple of days and then we proceeded east again. We came to a hillside and there was a hut on the side of the hill and there was a small stream below and some wild tomatoes or some such fruit growing. We looked in the hut and saw some rice husks on the floor, so we beat out the rice and made ourselves a meal and settled down to get a rest. I don't know who should have been on guard, somebody or other should have been, but by this time you must realise that we were pretty well exhausted. We'd had enough. We were just exhausted.

Captured by Japs

The next thing we knew was the door burst open and in came a Jap soldier with a bayonet. He caught Lance Corporal Jordan who didn't have his insignia on his arm, in his hand and was just going to have another go when the Japanese officer called him off. They motioned for us to go outside and we stood outside in a line, the six of us, and there facing us was a half moon circle of Japanese soldiers, armed, and the centre one had a machine gun pointed at us. I remember turning round and saying "The bastards are going to shoot us in cold blood." But strangely enough we were fortunate in our captors. You see we were captured by the Imperial Guard and they were professional soldiers. Anyway they tied our hands, took our possessions off us, anything we had, and then they led us to their jungle camp.

We were interrogated, but there was nothing we could tell them, in fact it was just a formality, because they knew exactly what had happened, because they had previously sent over aircraft to the area where we'd been operating and dropped leaflets, saying that we had done our job, that there was no chance of getting out and we should surrender to the Imperial Japanese Army. It was propaganda. Anyway with this particular lot we weren't treated too bad.

They fed us and they gave us various jobs to do around the camp. It was an interim stop. As a matter of fact they made me a batman, evidently there were some Japanese Officers and the Japanese batmen were one short. I had to do chores around the camp and I had to sleep in the same place with these other batmen, and when they got their daily ration of jugrri, which is a sort of fudge, and some Burmese cigarettes, they would put a little pile at the place where I slept with them. And this is one of the light-hearted bits I must tell you about, because as I said at the beginning there's nothing added and nothing taken away here. I've got to speak as I find and in every rotten barrel of apples there may be one that survives, in everything that's good there's always something bad or in everything that's bad there's always something good. That's just trying to explain myself.

There was one Japanese soldier there. He could speak English not too badly and he said his name was Tagata. He was a barber in Tokyo and he wanted me to come to his hut for supper that night. I put my hands together and said "I'm a prisoner, I can't accept such an invitation." Evidently he'd obtained permission from his sergeant who guarded me, so under escort I went to his hut that night and he gave me rice and kidneys to eat and chatted to me and said that after the war I'd go to Tokyo and he'd introduce me to his mother and father. I felt quite good over this.

After two weeks or so, I'm not quite sure of the length of time, it could have been ten days, we were put on a truck to Maymyo Discipline Camp.

Maymyo in peace time had been a local leave station for soldiers, because evidently when a soldier gets leave he can't go back to England. The climate was very pleasant and there were canteen facilities, or there had been for the British soldiers, snooker tables, I think there was a cinema and other forms of local recreation. On the way there we had to have an overnight stop at another Japanese jungle camp and while our escorts went off to have a break or a meal we were left under guard of the camp personnel. We were taken into a hut and made to kneel with our hands tied behind our backs in the execution position and a big Japanese Officer came in wielding a sword, he drew the sword from the scabbard and started flashing it around. We thought this was it, but thank God it wasn't. It was a sick joke but at that time it was quite traumatic.

When we got to Maymyo, as soon as we got through the gates we got punched and kicked, generally beaten up. I won't go into details but it was very harsh treatment. A lot of the guards were Korean and I can assure you that they were as bad if not worse than the Japanese themselves. There we were taught Japanese words of command so that the Japanese felt superior and learned how to count in Japanese and how to act at tenko, or roll call, and generally the word for attention and necessary words of discipline.

After about two to four weeks, I'm not sure, we were sent to Rangoon. Rangoon Jail had been built by the British. It was a civilian jail. A massive great big building. We were three days in steel cattle trucks on a train. We stopped for food in Mandalay and there's another contradiction to the very bad times we had later on. As the doors were opened to let the air in, one of the Japanese soldiers - his name was Hianossi - a big six footer of the Imperial Guard who captured us. Evidently, and like many British soldiers they were always on the move. He looked through the door of this train, recognised us and motioned us to say "Don't go away" - as if we could! He came back and threw a bunch of bananas into the train carriage.

Anyway, we got to Rangoon. Already one or two people had died because of the confined conditions and the reason my eyesight is not very good now - I got beri beri later on - is because somebody had done their business in my hat so I had no hat and no protection from the sun.

We went into Block 6 and then Block 3. What can I say about our prison life. We were short or food, no medical attention and the worst enemy there was disease. The discipline was less harsh than in the Discipline Camp. We were in compounds, although the air personnel from the RAF and the American Airforce were treated as criminals and locked in solitary confinement and treated much worse than us at the beginning, they were eventually allowed into the compounds with us.

Disease was rife. There was wet and dry beri-beri, I'll tell you the difference later. Malaria, dysentery, jungle sores, scabies, lockjaw, bugs, scorpions and cockroaches.

Beri-beri experience

Let me tell you about our first experience of beri beri. There was a Lance Corporal, only 19 years old, and all or a sudden we noticed that he looked very much pregnant, just like a woman seven or eight months gone. And suddenly Lance Corporal Talbot died. He was our first casualty in Rangoon itself.

When we had his funeral parade (we got the permission of the Japanese) one of the regular soldiers, Lt. Roberts, assembled us and said "You know that Lance Corporal Talbot died, you're probably wondering what he died of. Well he died of beri beri and this is a malnutrition disease, the lack of Vitamin B and it usually starts in the feet, in the instep. Your feet start to swell and when you press your thumb or finger in and the print remains, it doesn't come out, then you know you have it. And gradually it spreads all over the body. You get a terrible craving but the worst thing you can do is drink because more water you drink the worse it is. And eventually it kills you because the pressure of water presses on the arteries and the heart stops."

I don't want to be rude but to describe what it looks like, just imagine you took a human being and put a valve in the side of their body. You get a bicycle pump and start to pump them up. They just blow up like a blown up doll. It gets so bad for the men their testicles get to the size of a football and their penis swells and they have to cup their private parts in their hands to walk, and then they die. This is the extent of wet beri beri.

I got dry beri beri!

This is an excrutiating pain in the tips of your fingers and toes. It was ok when you were on the go but once you you tried to sleep it was terrible. We used to massage each other's toes. There were no medical facilities at all; you could have a sore one day the size of a sixpence and then gangrene would set in. People were dying every day from these various diseases. Harry Kinson of D Company got diphtheria (Leon is referring to Pte. Harry Kimpton of Column 8), and there was no treatment, so he just choked to death.

Another man from the Signals got peritonitis, his appendix burst and he was screaming every night until he died. We were out on a working party and there was an air raid of American B-29's and two were shot down. One came down half a mile from the jail and everyone in it was killed. The other one came down with smoke streaming from the fuselage. Two of the airmen survived. One of them was so badly burned it was a horrible sight and Colonel Mackenzie the Medical Officer begged the Japanese to shoot the man and put him out of his misery. Mercifully he died 24 hours later. The other man looked as though he was going to recover, but gangrene took over and he died too. This was all through lack of medical treatment.

The Japanese were experimenting with brain injections on the prisoners. One of them, Lance Corporal Hardy, was executed after escaping and wandering the streets of Rangoon. There was a propaganda newspaper called the 'Greater Asia', printed in English giving the Japanese version of what was happening in Europe. According to this newspaper London was destroyed, but the Japanese had their own newspapers and a Chinese General named Chi would translate this into English. The Japanese wanted General Chi to join their puppet regime in Rangoon, which he refused to do, and later in a Japanese instigated brawl between rival factions of Chinese, he was stabbed to death. We had lost a good friend.

Maymyo in peace time had been a local leave station for soldiers, because evidently when a soldier gets leave he can't go back to England. The climate was very pleasant and there were canteen facilities, or there had been for the British soldiers, snooker tables, I think there was a cinema and other forms of local recreation. On the way there we had to have an overnight stop at another Japanese jungle camp and while our escorts went off to have a break or a meal we were left under guard of the camp personnel. We were taken into a hut and made to kneel with our hands tied behind our backs in the execution position and a big Japanese Officer came in wielding a sword, he drew the sword from the scabbard and started flashing it around. We thought this was it, but thank God it wasn't. It was a sick joke but at that time it was quite traumatic.

When we got to Maymyo, as soon as we got through the gates we got punched and kicked, generally beaten up. I won't go into details but it was very harsh treatment. A lot of the guards were Korean and I can assure you that they were as bad if not worse than the Japanese themselves. There we were taught Japanese words of command so that the Japanese felt superior and learned how to count in Japanese and how to act at tenko, or roll call, and generally the word for attention and necessary words of discipline.

After about two to four weeks, I'm not sure, we were sent to Rangoon. Rangoon Jail had been built by the British. It was a civilian jail. A massive great big building. We were three days in steel cattle trucks on a train. We stopped for food in Mandalay and there's another contradiction to the very bad times we had later on. As the doors were opened to let the air in, one of the Japanese soldiers - his name was Hianossi - a big six footer of the Imperial Guard who captured us. Evidently, and like many British soldiers they were always on the move. He looked through the door of this train, recognised us and motioned us to say "Don't go away" - as if we could! He came back and threw a bunch of bananas into the train carriage.

Anyway, we got to Rangoon. Already one or two people had died because of the confined conditions and the reason my eyesight is not very good now - I got beri beri later on - is because somebody had done their business in my hat so I had no hat and no protection from the sun.

We went into Block 6 and then Block 3. What can I say about our prison life. We were short or food, no medical attention and the worst enemy there was disease. The discipline was less harsh than in the Discipline Camp. We were in compounds, although the air personnel from the RAF and the American Airforce were treated as criminals and locked in solitary confinement and treated much worse than us at the beginning, they were eventually allowed into the compounds with us.

Disease was rife. There was wet and dry beri-beri, I'll tell you the difference later. Malaria, dysentery, jungle sores, scabies, lockjaw, bugs, scorpions and cockroaches.

Beri-beri experience

Let me tell you about our first experience of beri beri. There was a Lance Corporal, only 19 years old, and all or a sudden we noticed that he looked very much pregnant, just like a woman seven or eight months gone. And suddenly Lance Corporal Talbot died. He was our first casualty in Rangoon itself.

When we had his funeral parade (we got the permission of the Japanese) one of the regular soldiers, Lt. Roberts, assembled us and said "You know that Lance Corporal Talbot died, you're probably wondering what he died of. Well he died of beri beri and this is a malnutrition disease, the lack of Vitamin B and it usually starts in the feet, in the instep. Your feet start to swell and when you press your thumb or finger in and the print remains, it doesn't come out, then you know you have it. And gradually it spreads all over the body. You get a terrible craving but the worst thing you can do is drink because more water you drink the worse it is. And eventually it kills you because the pressure of water presses on the arteries and the heart stops."

I don't want to be rude but to describe what it looks like, just imagine you took a human being and put a valve in the side of their body. You get a bicycle pump and start to pump them up. They just blow up like a blown up doll. It gets so bad for the men their testicles get to the size of a football and their penis swells and they have to cup their private parts in their hands to walk, and then they die. This is the extent of wet beri beri.

I got dry beri beri!

This is an excrutiating pain in the tips of your fingers and toes. It was ok when you were on the go but once you you tried to sleep it was terrible. We used to massage each other's toes. There were no medical facilities at all; you could have a sore one day the size of a sixpence and then gangrene would set in. People were dying every day from these various diseases. Harry Kinson of D Company got diphtheria (Leon is referring to Pte. Harry Kimpton of Column 8), and there was no treatment, so he just choked to death.

Another man from the Signals got peritonitis, his appendix burst and he was screaming every night until he died. We were out on a working party and there was an air raid of American B-29's and two were shot down. One came down half a mile from the jail and everyone in it was killed. The other one came down with smoke streaming from the fuselage. Two of the airmen survived. One of them was so badly burned it was a horrible sight and Colonel Mackenzie the Medical Officer begged the Japanese to shoot the man and put him out of his misery. Mercifully he died 24 hours later. The other man looked as though he was going to recover, but gangrene took over and he died too. This was all through lack of medical treatment.

The Japanese were experimenting with brain injections on the prisoners. One of them, Lance Corporal Hardy, was executed after escaping and wandering the streets of Rangoon. There was a propaganda newspaper called the 'Greater Asia', printed in English giving the Japanese version of what was happening in Europe. According to this newspaper London was destroyed, but the Japanese had their own newspapers and a Chinese General named Chi would translate this into English. The Japanese wanted General Chi to join their puppet regime in Rangoon, which he refused to do, and later in a Japanese instigated brawl between rival factions of Chinese, he was stabbed to death. We had lost a good friend.

I had an accident whilst working in the corrugated iron cookhouse, scalding an ankle. The only treatment given for the burn was stinging copper sulphate, that being the only thing to form a skin over the burn to stop infection. I contracted lockjaw, my legs seized up and I had to haul myself around using the walls.

If you had a friend in there it made things more bearable and I had a good friend called Dennis Walmsley. Dennis and I were born on the same day, 21st of April 1920, and it was on 21st April 1943, my 23rd birthday and I was taken prisoner. Dennis died and at his funeral people were saying that I would be next.

There was an outbreak of cholera which kills in 24 hours. Twelve men died and the bodies were burnt on a fire, then lime was put around to disinfect the area. There were hundreds of thousands of flies round the latrine, so stopping the spread of disease was impossible.

Eventually the Japanese seemed more tense and there were a lot of comings and goings. On 25th April 1945 the Japanese Commandant gave a list of all those able to walk and those who could not walk to our Commanding Officer. There were about 400 to 450 men classified as being able to walk. Some of us were given cast off Japanese clothing, although I still had bare feet and wore only a loincloth. We were given buckets of rice and left Rangoon not knowing what was going to happen to us.

We marched for five days northwards over hard crusty ground under constant strafing by British Mosquito aircraft, until we came to a river where the bridge was being mined by Japanese sappers. We were left there with a note saying we were free and would live to fight another day.

If you had a friend in there it made things more bearable and I had a good friend called Dennis Walmsley. Dennis and I were born on the same day, 21st of April 1920, and it was on 21st April 1943, my 23rd birthday and I was taken prisoner. Dennis died and at his funeral people were saying that I would be next.

There was an outbreak of cholera which kills in 24 hours. Twelve men died and the bodies were burnt on a fire, then lime was put around to disinfect the area. There were hundreds of thousands of flies round the latrine, so stopping the spread of disease was impossible.

Eventually the Japanese seemed more tense and there were a lot of comings and goings. On 25th April 1945 the Japanese Commandant gave a list of all those able to walk and those who could not walk to our Commanding Officer. There were about 400 to 450 men classified as being able to walk. Some of us were given cast off Japanese clothing, although I still had bare feet and wore only a loincloth. We were given buckets of rice and left Rangoon not knowing what was going to happen to us.

We marched for five days northwards over hard crusty ground under constant strafing by British Mosquito aircraft, until we came to a river where the bridge was being mined by Japanese sappers. We were left there with a note saying we were free and would live to fight another day.

The Rescue

The Burmese then became more friendly and gave us food. We had been pulling Japanese handcarts so we ransacked these to find sheets and blankets. Out of these we made a Union Jack and 4 foot high letters spelling out '400 prisoners', which we placed in a paddy field outside the village.

The next morning a flight of planes flew over the sign and then went away again. Just before dusk some Hurricanes came over really low, but instead of flying away again they machine-gunned us. When it was dark we made our way back to the village feeling very shocked. Colonel MacKenzie, the Medical Officer, and Brigadier Hobson the Commanding Officer in prison for three years, had lain side-by-side during the air-raid. The Brigadier had taken a 20 mm can shell through his back and was now dead. Everyone was stunned and didn't know what to do.

I was in a slit trench just outside of the village with an American called Frankie Hubbard. A Burmese girl gave us water and led us to another village. Here the Headman told us that the Japanese had left the area and that the Burmese would like to make friends with the British and Americans.

The following morning we helped each other towards the road. We were picked up by ambulances and rescued. We passed Japanese snipers strapped into trees, all of them dead.

It was wonderful. Some Dakotas arrived to take us to a base camp at Akyab where we had boiled eggs and bread and butter. From there we went to the base hospital at Comilla where we stayed for a few weeks. Everyone had their own padres and chaplains and I had a Jewish Chaplin called Major Jaffee. He told me that there was nothing wrong with me that a good chicken soup wouldn't cure. I promised him I'd write to my parents and let them know I was alright. Major Jaffee then went off to the frontline where he prepared to celebrate Passover with the Jewish troops.

NB. Jaffee remembered to write a letter to Leon's parents when he returned from the frontline, I'm not sure if Leon managed to do the same!

I was taken by Hospital ship to Madras and then by hospital train. I flew home via Poona, Karachi, the Persian Gulf, Libya and then to Taunton in Somerset. I was home in London at last. Six weeks later I married my girlfriend who was still waiting for me.

I went into the Army as a Private and came out as a Private. I re-call a Jewish boy in Rangoon, Berkowitz, who kept up his Jewish faith the whole time and every night read his prayerbook. The Flight Sergeant in the jail used to say "Quite everybody a man is saying his prayers."

When I was out in a working party from the camp I stole a pair of Japanese P.T. shoes and white socks from a warehouse. One day after roll call I put them on and was walking down the corridor, a Japanese guard stopped me and made me give them up and gave me a little lacquered cigarette box in exchange. I was thankful that I was not given up as a thief, because the Japanese have a great sense of honour and would have punished me severely.

This is the end of my story, it is just an insight of what happened to me and to others.

The Burmese then became more friendly and gave us food. We had been pulling Japanese handcarts so we ransacked these to find sheets and blankets. Out of these we made a Union Jack and 4 foot high letters spelling out '400 prisoners', which we placed in a paddy field outside the village.

The next morning a flight of planes flew over the sign and then went away again. Just before dusk some Hurricanes came over really low, but instead of flying away again they machine-gunned us. When it was dark we made our way back to the village feeling very shocked. Colonel MacKenzie, the Medical Officer, and Brigadier Hobson the Commanding Officer in prison for three years, had lain side-by-side during the air-raid. The Brigadier had taken a 20 mm can shell through his back and was now dead. Everyone was stunned and didn't know what to do.

I was in a slit trench just outside of the village with an American called Frankie Hubbard. A Burmese girl gave us water and led us to another village. Here the Headman told us that the Japanese had left the area and that the Burmese would like to make friends with the British and Americans.

The following morning we helped each other towards the road. We were picked up by ambulances and rescued. We passed Japanese snipers strapped into trees, all of them dead.

It was wonderful. Some Dakotas arrived to take us to a base camp at Akyab where we had boiled eggs and bread and butter. From there we went to the base hospital at Comilla where we stayed for a few weeks. Everyone had their own padres and chaplains and I had a Jewish Chaplin called Major Jaffee. He told me that there was nothing wrong with me that a good chicken soup wouldn't cure. I promised him I'd write to my parents and let them know I was alright. Major Jaffee then went off to the frontline where he prepared to celebrate Passover with the Jewish troops.

NB. Jaffee remembered to write a letter to Leon's parents when he returned from the frontline, I'm not sure if Leon managed to do the same!

I was taken by Hospital ship to Madras and then by hospital train. I flew home via Poona, Karachi, the Persian Gulf, Libya and then to Taunton in Somerset. I was home in London at last. Six weeks later I married my girlfriend who was still waiting for me.

I went into the Army as a Private and came out as a Private. I re-call a Jewish boy in Rangoon, Berkowitz, who kept up his Jewish faith the whole time and every night read his prayerbook. The Flight Sergeant in the jail used to say "Quite everybody a man is saying his prayers."

When I was out in a working party from the camp I stole a pair of Japanese P.T. shoes and white socks from a warehouse. One day after roll call I put them on and was walking down the corridor, a Japanese guard stopped me and made me give them up and gave me a little lacquered cigarette box in exchange. I was thankful that I was not given up as a thief, because the Japanese have a great sense of honour and would have punished me severely.

This is the end of my story, it is just an insight of what happened to me and to others.

After the war Leon joined the Far East Prisoners of War and Jewish War Veteran Associations. He settled fairly quickly into married life and did not suffer too much with nightmares or the after effects of his service in Burma and his time as a POW. Later in his working life he served as a Security Officer at the British Museum.

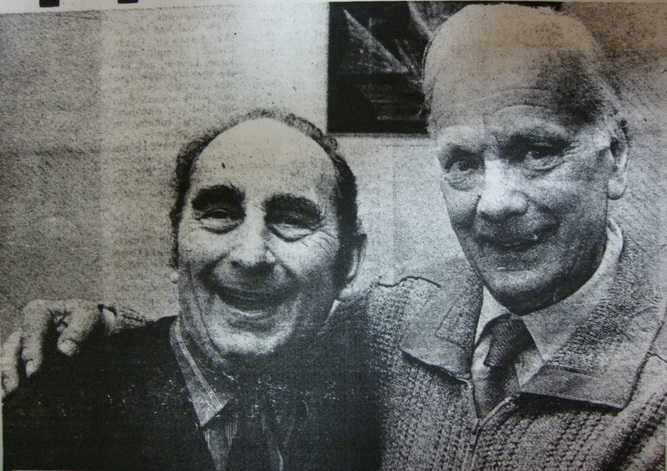

Leon made every effort during his later life to ensure that the Longcloth story was heard and written down. On the 5th February 1988 he had the chance to meet up with one of his Chindit comrades from 1943, fellow prisoner of war, Fred Holloman. Pte. Holloman had served as a muleteer in Northern Group Head Quarters and at times during the operation had been in close proximity to Brigadier Wingate.

Here is a transcription of the newspaper report that covered the reunion in 1988:

Hello Again!

Two old soldiers who were held captive by the Japanese at the same prisoner-of-war camp in Burma, have been re-united more than 40 years after they were liberated. Leon Frank, from Highams Park, who is Jewish, and Fred Holloman, from Walthamstow, served in the 13th Battalion, the Kings Liverpool Regiment and were part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, under the command of the then Brigadier, Orde Wingate.

Together, they crossed into Burma from India on a sabotage mission against Japanese front line troops. However, the Japanese offensive proved too strong and Leon and Fred were captured on April 21st, 1943, Leon's 23rd birthday (this is not strictly true, as Fred was captured on the 2nd May).

They were imprisoned in an old British leave station (Maymyo) in wooden huts, on the Burmese-Chinese border, and later transferred to a camp in Rangoon. Leon, now 67, recalled: "Out of 200 captives only 20 of us survived. I had every disease going, from malaria to dysentery and beri beri, but I was determined to survive. The big fellows died sometimes because they needed more food, but I am small and didn't need much."

Leon and Fred never gave up during their harsh ordeal and after two more years, on April 30th, 1945, they were liberated by Allied soldiers. The POW's were split up and never saw each other again, until they read a story in their local paper, appealing for soldiers to contact an organisation trying to reunite wartime comrades.

Leon made every effort during his later life to ensure that the Longcloth story was heard and written down. On the 5th February 1988 he had the chance to meet up with one of his Chindit comrades from 1943, fellow prisoner of war, Fred Holloman. Pte. Holloman had served as a muleteer in Northern Group Head Quarters and at times during the operation had been in close proximity to Brigadier Wingate.

Here is a transcription of the newspaper report that covered the reunion in 1988:

Hello Again!

Two old soldiers who were held captive by the Japanese at the same prisoner-of-war camp in Burma, have been re-united more than 40 years after they were liberated. Leon Frank, from Highams Park, who is Jewish, and Fred Holloman, from Walthamstow, served in the 13th Battalion, the Kings Liverpool Regiment and were part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, under the command of the then Brigadier, Orde Wingate.

Together, they crossed into Burma from India on a sabotage mission against Japanese front line troops. However, the Japanese offensive proved too strong and Leon and Fred were captured on April 21st, 1943, Leon's 23rd birthday (this is not strictly true, as Fred was captured on the 2nd May).

They were imprisoned in an old British leave station (Maymyo) in wooden huts, on the Burmese-Chinese border, and later transferred to a camp in Rangoon. Leon, now 67, recalled: "Out of 200 captives only 20 of us survived. I had every disease going, from malaria to dysentery and beri beri, but I was determined to survive. The big fellows died sometimes because they needed more food, but I am small and didn't need much."

Leon and Fred never gave up during their harsh ordeal and after two more years, on April 30th, 1945, they were liberated by Allied soldiers. The POW's were split up and never saw each other again, until they read a story in their local paper, appealing for soldiers to contact an organisation trying to reunite wartime comrades.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and stated contributors.

July 2013.

July 2013.