Fusilier Leslie Arthur Cecil Troth

Pte. L.A.C. Troth, known to his friends and family as Arthur.

Pte. L.A.C. Troth, known to his friends and family as Arthur.

Pte. Leslie Troth, known to his close friends and family as Arthur was part of Column 7 on Operation Longcloth, under the overall leadership of Major Kenneth Gilkes. For most of the the journey through the jungles of Burma in 1943, Arthur, along with his comrades in Column 7 had kept close to Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters, protecting and shadowing their leader wherever he went.

Formerly a Royal Welch Fusilier before being attached to the 13th King's and joining Chindit training in late September 1942, Arthur also served as 'batman' to Lieutenant Stephen Hector during his time with Column 7.

By late March 1943 many of the men from Column 7 were suffering from severe exhaustion, starvation and numerous other afflictions common to the jungles of Burma at that time. A group of Chindits, already very ill with diseases such as dysentery and malaria were placed under the leadership of Lieutenant Rex Walker, a young officer from Column 7. He was given the task (by Major Gilkes) of taking these men back to India when the Column split up into it's dispersal parties.

Arthur found himself a member of Walker's group, which also included Lieutenant Hector and the Medical Officer from Column 5, William Aird. They headed due west toward the Irrawaddy, where they hoped to receive a large supply drop of rations, which had been organised for them by Major Gilkes, just before they had all gone their separate ways. Walker's party never reached this rendezvous. According to battalion records Arthur Troth was last seen on the 10th April 1943.

To read more about both Rex Walker's dispersal group and Lieutenant Stephen Hector, please click on the links below:

Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

Stephen Hector (First story on page).

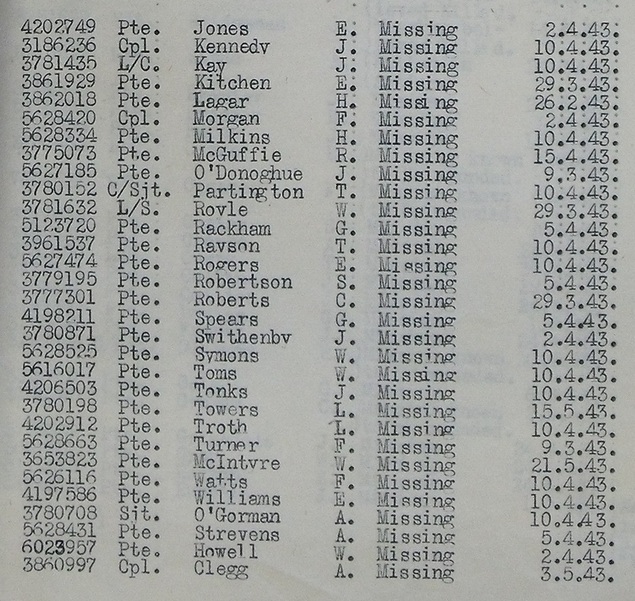

As mentioned earlier, this group were last seen on about the 10th April. Here is a transcription of a report made by Captain Leslie Cottrell, who was Column 7's Adjutant on Operation Longcloth.

Statement of evidence as of 24th of July 1943.

Witness. 138760 Capt. L.R. Cottrell.

"I was Staff Officer of number seven Column, during Brigadier Wingate's Burma expedition. On April 10th, 1943, the Column Commander (Gilkes) decided for various tactical and administrative reasons to split his column. This was mid-way between the Mongmit and the Myitson Road.

Lieutenant Walker was ordered to take charge of a party which consisted of three other officers and 25 British Other Ranks. His orders were to march approximately westward, re-cross the Irrawaddy and return to Assam by the most direct route. The British Other Ranks were not considered by the Column Commander or by the Medical Officer as physically capable of marching the long way out via China, as the main body intended to do.

They were all equipped with arms and ammunition and had two days hard scale rations each, the officers had maps and compasses. An Air Supply drop was arranged for them just west of the Irrawaddy, but, the party failed to make the rendezvous and the aircraft concerned did not locate them. The Japanese were fairly active in this area. Nothing has been heard of any of these Officers or men since."

Signed. Leslie Cottrell, Captain.

Counter-signed. H. Cotton, Captain.

From various other witness reports and first hand accounts, it would seem that Walker's group was attacked firstly by Burmese militia and then, perhaps, a Japanese patrol. Several men were lost during these attacks.

Formerly a Royal Welch Fusilier before being attached to the 13th King's and joining Chindit training in late September 1942, Arthur also served as 'batman' to Lieutenant Stephen Hector during his time with Column 7.

By late March 1943 many of the men from Column 7 were suffering from severe exhaustion, starvation and numerous other afflictions common to the jungles of Burma at that time. A group of Chindits, already very ill with diseases such as dysentery and malaria were placed under the leadership of Lieutenant Rex Walker, a young officer from Column 7. He was given the task (by Major Gilkes) of taking these men back to India when the Column split up into it's dispersal parties.

Arthur found himself a member of Walker's group, which also included Lieutenant Hector and the Medical Officer from Column 5, William Aird. They headed due west toward the Irrawaddy, where they hoped to receive a large supply drop of rations, which had been organised for them by Major Gilkes, just before they had all gone their separate ways. Walker's party never reached this rendezvous. According to battalion records Arthur Troth was last seen on the 10th April 1943.

To read more about both Rex Walker's dispersal group and Lieutenant Stephen Hector, please click on the links below:

Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

Stephen Hector (First story on page).

As mentioned earlier, this group were last seen on about the 10th April. Here is a transcription of a report made by Captain Leslie Cottrell, who was Column 7's Adjutant on Operation Longcloth.

Statement of evidence as of 24th of July 1943.

Witness. 138760 Capt. L.R. Cottrell.

"I was Staff Officer of number seven Column, during Brigadier Wingate's Burma expedition. On April 10th, 1943, the Column Commander (Gilkes) decided for various tactical and administrative reasons to split his column. This was mid-way between the Mongmit and the Myitson Road.

Lieutenant Walker was ordered to take charge of a party which consisted of three other officers and 25 British Other Ranks. His orders were to march approximately westward, re-cross the Irrawaddy and return to Assam by the most direct route. The British Other Ranks were not considered by the Column Commander or by the Medical Officer as physically capable of marching the long way out via China, as the main body intended to do.

They were all equipped with arms and ammunition and had two days hard scale rations each, the officers had maps and compasses. An Air Supply drop was arranged for them just west of the Irrawaddy, but, the party failed to make the rendezvous and the aircraft concerned did not locate them. The Japanese were fairly active in this area. Nothing has been heard of any of these Officers or men since."

Signed. Leslie Cottrell, Captain.

Counter-signed. H. Cotton, Captain.

From various other witness reports and first hand accounts, it would seem that Walker's group was attacked firstly by Burmese militia and then, perhaps, a Japanese patrol. Several men were lost during these attacks.

Of the 29 men who made up Lieutenant Walker's dispersal party, only five survived the war and returned home to the UK. The majority were taken prisoner by the Japanese at various times after the 11th April. Some died in POW transit camps, possibly in places like Kalaw and Maymyo, others made the final journey down to Rangoon, only to perish in Block 6 of the jail, succumbing to dreadful diseases such as dysentery and beri beri.

Arthur Troth was to be one of the very fortunate Chindits to survive his time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon. He was captured on 7th May 1943, this was fairly late in the day in terms of Chindits who became prisoners to the Japanese and makes me wonder if he ever frequented the other POW Camps, such as Maymyo. It is more likely I think, that Arthur was sent directly to Rangoon Jail after capture.

Arthur was given the POW number 348 by the Japanese guards and would have to answer with this number at all roll calls or 'tenko's' as they were know in the jail. Prisoners had to call out their own number in Japanese or suffer a beating at the hands of the brutal and sadistic prison guards.

Most of the Chindits captured in 1943 were eventually held in Block 6 of the jail. Here they quickly dwindled in number with men dying almost every day, mostly it has to be said from the effects of their time in the Burmese jungles on Operation Longcloth, rather than any ill-treatment from the Japanese.

To read more about the Chindits of Rangoon Jail and the other POW Camps they were held in, please click on the following link:

Chindit POW's

Pte. Troth survived just under two years of incarceration in Rangoon and was part of a large group of prisoners deemed fit to march out of the jail in late April 1945. The Japanese knew their time in the city of Rangoon was coming to an end and decided to take around 450 POW's out of the jail and attempt to march them all the way into Thailand. Some men thought they were simply being used as hostages by the Japanese as they fled Burma, while others now believed that they were destined to work on the infamous Burma or 'Death' Railway. Either way the Japanese decided to give up on the idea near the Burmese town of Pegu and the men were given their freedom on the 29th April 1945, close to a small village named Waw. Now all the men had to do was to negotiate their way safely across to the British lines, avoiding if possible the other retreating Japanese forces.

Seen below is Arthur Troth's Japanese index card. These were informational cards which detailed the POW's personal data in regard to their place and time of capture and to their next of kin, family etc. The cards are held at the National Archives in London and can be found in the file series WO345. The cards are stored alphabetically in 58 boxes.

Arthur Troth was to be one of the very fortunate Chindits to survive his time as a prisoner of war in Rangoon. He was captured on 7th May 1943, this was fairly late in the day in terms of Chindits who became prisoners to the Japanese and makes me wonder if he ever frequented the other POW Camps, such as Maymyo. It is more likely I think, that Arthur was sent directly to Rangoon Jail after capture.

Arthur was given the POW number 348 by the Japanese guards and would have to answer with this number at all roll calls or 'tenko's' as they were know in the jail. Prisoners had to call out their own number in Japanese or suffer a beating at the hands of the brutal and sadistic prison guards.

Most of the Chindits captured in 1943 were eventually held in Block 6 of the jail. Here they quickly dwindled in number with men dying almost every day, mostly it has to be said from the effects of their time in the Burmese jungles on Operation Longcloth, rather than any ill-treatment from the Japanese.

To read more about the Chindits of Rangoon Jail and the other POW Camps they were held in, please click on the following link:

Chindit POW's

Pte. Troth survived just under two years of incarceration in Rangoon and was part of a large group of prisoners deemed fit to march out of the jail in late April 1945. The Japanese knew their time in the city of Rangoon was coming to an end and decided to take around 450 POW's out of the jail and attempt to march them all the way into Thailand. Some men thought they were simply being used as hostages by the Japanese as they fled Burma, while others now believed that they were destined to work on the infamous Burma or 'Death' Railway. Either way the Japanese decided to give up on the idea near the Burmese town of Pegu and the men were given their freedom on the 29th April 1945, close to a small village named Waw. Now all the men had to do was to negotiate their way safely across to the British lines, avoiding if possible the other retreating Japanese forces.

Seen below is Arthur Troth's Japanese index card. These were informational cards which detailed the POW's personal data in regard to their place and time of capture and to their next of kin, family etc. The cards are held at the National Archives in London and can be found in the file series WO345. The cards are stored alphabetically in 58 boxes.

I was fortunate enough to be contacted by the family of Arthur Troth in the form of his daughter Diane and her husband Keith Phipps. This is what Keith had to tell me in our short email correspondance:

Steve, thank you so much for getting in touch and for the interesting information you have sent over. My wife Diane will be so excited when I tell her.

None of us know much about where Arthur was or what happened to him in Burma, although when he was posted as missing, his step sister saw a 'Pathe' newsreel at the cinema and went home and said that she saw him and he was alive."

We know he joined the Royal Welch Fusiliers at first and was later transferred to the Kings Regiment. We don't know how he got out to India, although I have read other people's accounts of soldiers leaving on ships and going via South Africa, to places such as Durban.

We originally got his date of capture from 'COFEPOW' (Children of Far East Prisoners of War) after finding his name on screen at the National Arboretum. I have since realised that this is the information held on his Japanese Index Card from the National Archives.

He told me that in captivity the local Burmese often treated the men worse than the Japanese. He also recalled playing Quoits with an American POW and that on release he had the choice of how to go home, by sea or by air. He chose to fly by Dakota. I don't know how long or which route he took. (There were many American airman in Rangoon Jail, most had been shot down over Burma in 1944/45, so Arthur could easily have been befriended by these men in Rangoon Jail).

One other piece of information that you probably no more of. I was told that Arthur didn't work on the railway but on road building. Do you know if this is true? I have read that the Japanese were using prisoners for this but again I don't know which POW Camps were involved. (None of the men from Rangoon Jail worked on the infamous 'Death Railway'. They were used as 'coolie' labour by the Japanese, clearing the bomb damaged streets of Rangoon, unloading ships at the city docks and building air-raid shelters for their hosts to take cover in during Allied bombing raids).

Keith continued:

Arhtur's time as a POW left him with poor health in the years after the war, although he did return to his previous employment when he got home.

We only have one photo of him in his Army uniform, his medals never came out of the box and he never wanted to join any Regimental Association or take part in any parades.

We have often wondered why Arthur originally was sent to join the Royal Welch Fusiliers, when his local and more obvious regiment would have been the Royal Warwickshire's. Was this normal practice in WW2? (I told Keith that my own grandfather was from Hampstead in London. He enlisted in December 1940 at a London Army recruitment office and was placed after Infantry training into the Devonshire Regiment. I do not think a man had a choice of regiment on enlistment or conscription. My understanding is that men were distributed where the need was at that particular time).

Keith concluded:

"Once again Steve, thank you for all your efforts, we have learned more in last couple of days than probably the last 50 odd years."

Many thanks must go to Keith and Diane Phipps for their help in compiling the story of Fusilier Arthur Troth.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2013.

Steve, thank you so much for getting in touch and for the interesting information you have sent over. My wife Diane will be so excited when I tell her.

None of us know much about where Arthur was or what happened to him in Burma, although when he was posted as missing, his step sister saw a 'Pathe' newsreel at the cinema and went home and said that she saw him and he was alive."

We know he joined the Royal Welch Fusiliers at first and was later transferred to the Kings Regiment. We don't know how he got out to India, although I have read other people's accounts of soldiers leaving on ships and going via South Africa, to places such as Durban.

We originally got his date of capture from 'COFEPOW' (Children of Far East Prisoners of War) after finding his name on screen at the National Arboretum. I have since realised that this is the information held on his Japanese Index Card from the National Archives.

He told me that in captivity the local Burmese often treated the men worse than the Japanese. He also recalled playing Quoits with an American POW and that on release he had the choice of how to go home, by sea or by air. He chose to fly by Dakota. I don't know how long or which route he took. (There were many American airman in Rangoon Jail, most had been shot down over Burma in 1944/45, so Arthur could easily have been befriended by these men in Rangoon Jail).

One other piece of information that you probably no more of. I was told that Arthur didn't work on the railway but on road building. Do you know if this is true? I have read that the Japanese were using prisoners for this but again I don't know which POW Camps were involved. (None of the men from Rangoon Jail worked on the infamous 'Death Railway'. They were used as 'coolie' labour by the Japanese, clearing the bomb damaged streets of Rangoon, unloading ships at the city docks and building air-raid shelters for their hosts to take cover in during Allied bombing raids).

Keith continued:

Arhtur's time as a POW left him with poor health in the years after the war, although he did return to his previous employment when he got home.

We only have one photo of him in his Army uniform, his medals never came out of the box and he never wanted to join any Regimental Association or take part in any parades.

We have often wondered why Arthur originally was sent to join the Royal Welch Fusiliers, when his local and more obvious regiment would have been the Royal Warwickshire's. Was this normal practice in WW2? (I told Keith that my own grandfather was from Hampstead in London. He enlisted in December 1940 at a London Army recruitment office and was placed after Infantry training into the Devonshire Regiment. I do not think a man had a choice of regiment on enlistment or conscription. My understanding is that men were distributed where the need was at that particular time).

Keith concluded:

"Once again Steve, thank you for all your efforts, we have learned more in last couple of days than probably the last 50 odd years."

Many thanks must go to Keith and Diane Phipps for their help in compiling the story of Fusilier Arthur Troth.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2013.