Rfm. Ramkrishna Limbu IDSM, including the story of Vivian Weatherall

Indian Distinguished Service Medal.

Indian Distinguished Service Medal.

In the autumn of 2013 I was very fortunate to contact ex-Gurkha Rifles Officer JP Cross. He has been exceptionally kind, and has given me permission to reproduce the stories of five Gurkha Riflemen contained within his book, 'Gurkhas at War'.

These men were all at one point or another part of 3/2 GR and took part in Operation Longcloth. JP Cross with the help of companion Buddhiman Gurung, travelled over 10,000 miles within the borders of Nepal, to speak with many Gurkha soldiers who had served with the British Army, spanning many years and fighting in places such as Burma, Malaya and the Falklands.

'Gurkhas at War' is a wonderful book and more so, an amazing testimony and resource to those studying the history of the Gurkha Regiments during these times.

Featured below is the story of Ramkrishna Limbu, originally of the 10th GR. Firstly, let us begin with JP Cross's brief overview of the original Chindit operation in 1943:

"The history of the first Chindit operation, a thrust behind the Japanese lines in north Burma to cause havoc by blowing up rail and road links, and the order to retreat in small groups, abandoning wounded and dead, men and mules alike, remains controversial. Poignant stories are still graphically told and nightmares still disturb the sleep of the dwindling band of survivors."

Ramkrishna Limbu IDSM (Indian Distinguished Service Medal), 3/2 GR, 2/10 GR and 4/10 GR, was another muleteer on Operation Longcloth.

I joined the Army when I was 21 years old and I am now 83. I trained at the 10th GRRC (Gurkha Rifles Regimental Centre) and after eight months was sent to Lalitpur to learn how to be a mule driver. I then joined 3/2 GR. We marched into Burma. It was Wingate's fighting patrol. We took explosives and mines but our column did not destroy any bridges, but other columns did.

Each platoon had a Burma Rifles man to be the interpreter. I picked up a few Burmese words but had no real knowledge of the language. It was essential to get news of the Japanese. Weatherall sahib spoke very good Khaskura (the Indic dialect of Nepal). Some of the Burmese villagers were pro-Japanese and gave us dukha (trouble). When the Japanese were seen to be weak the Burmese became pro-British once more. Many of our men and mules were killed. I was in No.6 Column and my mule was number 373.

NB. Column 6 had been disbanded around Christmas 1942, the personnel from this column had suffered more than most from sickness and other misfortune. The remainder of the unit was distributed amongst the other surviving columns, it is likely that Ramkrishna went to either Column 1, which included Major Weatherall or Column 3 under the command of Major Calvert.

Ramkrishna contiunes:

I have no idea how far we moved in any day nor where we went. We had airdrops on the way in. We moved by night. Some railway bridges were blown up. We had to make our own way out after that and had no re-supply. I and my mule went hungry, as often there was nothing edible for either of us. I killed a few Japanese on the way out and many of our own men were killed. I can't remember the names of any of the places we went through.

The leader of our small group paid for boats to take us back over the Chindwin. Out of all the mules that went into Burma I was the only man to bring mine out and return it when we reached Manipur. All of us went to hospital for three or four days. We were skin and bones. Horses die easily, mules don't.

I was awarded an IDSM bahaduri (gallantry medal) in 1943. Lord Wavell came to give it to me and photos were taken but I never got a copy. After two months in Manipur we were sent on home leave. I was from Dehra Dun and returned there. 3/2 GR was disbanded and I went back to my own regiment and was posted to 4/10 GR.

4/10 GR went down the Tamu Road to engage the enemy. The Japanese wounded six of us when we attacked the RAP (regimental aid post) that they had captured. It was a grenade that damaged me. I was evacuated to India by air and after I was better, I worked in 10th GRRC (Gurkha Rifles Regimental Centre) Hospital for two years in charge of the medical orderlies. It was here that I was promoted to Naik (Corporal).

These men were all at one point or another part of 3/2 GR and took part in Operation Longcloth. JP Cross with the help of companion Buddhiman Gurung, travelled over 10,000 miles within the borders of Nepal, to speak with many Gurkha soldiers who had served with the British Army, spanning many years and fighting in places such as Burma, Malaya and the Falklands.

'Gurkhas at War' is a wonderful book and more so, an amazing testimony and resource to those studying the history of the Gurkha Regiments during these times.

Featured below is the story of Ramkrishna Limbu, originally of the 10th GR. Firstly, let us begin with JP Cross's brief overview of the original Chindit operation in 1943:

"The history of the first Chindit operation, a thrust behind the Japanese lines in north Burma to cause havoc by blowing up rail and road links, and the order to retreat in small groups, abandoning wounded and dead, men and mules alike, remains controversial. Poignant stories are still graphically told and nightmares still disturb the sleep of the dwindling band of survivors."

Ramkrishna Limbu IDSM (Indian Distinguished Service Medal), 3/2 GR, 2/10 GR and 4/10 GR, was another muleteer on Operation Longcloth.

I joined the Army when I was 21 years old and I am now 83. I trained at the 10th GRRC (Gurkha Rifles Regimental Centre) and after eight months was sent to Lalitpur to learn how to be a mule driver. I then joined 3/2 GR. We marched into Burma. It was Wingate's fighting patrol. We took explosives and mines but our column did not destroy any bridges, but other columns did.

Each platoon had a Burma Rifles man to be the interpreter. I picked up a few Burmese words but had no real knowledge of the language. It was essential to get news of the Japanese. Weatherall sahib spoke very good Khaskura (the Indic dialect of Nepal). Some of the Burmese villagers were pro-Japanese and gave us dukha (trouble). When the Japanese were seen to be weak the Burmese became pro-British once more. Many of our men and mules were killed. I was in No.6 Column and my mule was number 373.

NB. Column 6 had been disbanded around Christmas 1942, the personnel from this column had suffered more than most from sickness and other misfortune. The remainder of the unit was distributed amongst the other surviving columns, it is likely that Ramkrishna went to either Column 1, which included Major Weatherall or Column 3 under the command of Major Calvert.

Ramkrishna contiunes:

I have no idea how far we moved in any day nor where we went. We had airdrops on the way in. We moved by night. Some railway bridges were blown up. We had to make our own way out after that and had no re-supply. I and my mule went hungry, as often there was nothing edible for either of us. I killed a few Japanese on the way out and many of our own men were killed. I can't remember the names of any of the places we went through.

The leader of our small group paid for boats to take us back over the Chindwin. Out of all the mules that went into Burma I was the only man to bring mine out and return it when we reached Manipur. All of us went to hospital for three or four days. We were skin and bones. Horses die easily, mules don't.

I was awarded an IDSM bahaduri (gallantry medal) in 1943. Lord Wavell came to give it to me and photos were taken but I never got a copy. After two months in Manipur we were sent on home leave. I was from Dehra Dun and returned there. 3/2 GR was disbanded and I went back to my own regiment and was posted to 4/10 GR.

4/10 GR went down the Tamu Road to engage the enemy. The Japanese wounded six of us when we attacked the RAP (regimental aid post) that they had captured. It was a grenade that damaged me. I was evacuated to India by air and after I was better, I worked in 10th GRRC (Gurkha Rifles Regimental Centre) Hospital for two years in charge of the medical orderlies. It was here that I was promoted to Naik (Corporal).

Rifleman Ramkrishna's short testimony ends here. Below is the citation for his Indian Distinguished Service Medal as recommended by Major Mike Calvert:

107867 Rifleman Ramkrishna Limbu

Action for which recommended:

Operations in Burma, March/April 1943.

For gallantry and devotion to duty. This Rifleman, who was a muleteer throughout the campaign showed the greatest devotion to duty, and when under fire set an example to all muleteers by the coolness and calmness with which he remained by his mule and load. In crossing the River Chindwin, although a poor swimmer, he succeeded in bringing many mules across by hanging on to their manes, carrying on until he exhausted himself and had to be rescued from drowning at the last moment. At the end of the campaign he reached India still leading his mule with its valuable load, having brought it successfully through six hundred miles of enemy country, of which much of the going was the worst imaginable. He was an outstanding example to all muleteers.

IDSM Recommended By:

Major J.M.Calvert (Column 3)

77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

NB. Only two mules from Column 3 returned home to India that year; 'Mabel' the mule who carried the demolition equipment and 'Yankee', who bore the weight of the column radio. It is not known if Ramkrishna was in charge of either of these animals.

As Ramkrishna Limbu mentions, as do many other Gurkha soldiers from 1943, 'Weatherall sahib', I thought I would elaborate on this officer's contribution to Operation Longcloth.

Major Vivian Stuart Weatherall had served with 3/2 Gurkha for many months and had been the initial choice as Commander of Chindit Column 1, which he had led through the majority of its training and preparation for the forthcoming operation. However, in the end Brigadier Wingate decided to replace most of the Gurkha Officers originally in command of Gurkha columns with very experienced British Army officers.

Although on the face of it this decision seemed reasonable and wise, it contributed hugely to the perceived failure of the Gurkha units on Operation Longcloth. The crucial area where the British Army officers struggled, was not surprisingly in communicating with their men. Weatherall was replaced almost at the last minute by Major George Dickson Dunlop of the Royal Scots. Here is how he remembered the difficulties of those times:

"The great mistake was having officers that could not speak directly and properly to their men. This placed far too greater a strain on the Column Commander. In the Gurkha columns on Longcloth there were men from four different races and languages. To get these groups to work together in times of hardship was difficult in the extreme. I have to confess that this wore me right down".

"The commander must be as fit and strong as any of his men, indeed probably more so, as all questions and decisions are ultimately down to him. This is of course how it should be, but I can tell you it is very hard. He must decide everything, right down to the last grain of rice (literally) and he must take all the blame if things go wrong".

107867 Rifleman Ramkrishna Limbu

Action for which recommended:

Operations in Burma, March/April 1943.

For gallantry and devotion to duty. This Rifleman, who was a muleteer throughout the campaign showed the greatest devotion to duty, and when under fire set an example to all muleteers by the coolness and calmness with which he remained by his mule and load. In crossing the River Chindwin, although a poor swimmer, he succeeded in bringing many mules across by hanging on to their manes, carrying on until he exhausted himself and had to be rescued from drowning at the last moment. At the end of the campaign he reached India still leading his mule with its valuable load, having brought it successfully through six hundred miles of enemy country, of which much of the going was the worst imaginable. He was an outstanding example to all muleteers.

IDSM Recommended By:

Major J.M.Calvert (Column 3)

77th Indian Infantry Brigade.

NB. Only two mules from Column 3 returned home to India that year; 'Mabel' the mule who carried the demolition equipment and 'Yankee', who bore the weight of the column radio. It is not known if Ramkrishna was in charge of either of these animals.

As Ramkrishna Limbu mentions, as do many other Gurkha soldiers from 1943, 'Weatherall sahib', I thought I would elaborate on this officer's contribution to Operation Longcloth.

Major Vivian Stuart Weatherall had served with 3/2 Gurkha for many months and had been the initial choice as Commander of Chindit Column 1, which he had led through the majority of its training and preparation for the forthcoming operation. However, in the end Brigadier Wingate decided to replace most of the Gurkha Officers originally in command of Gurkha columns with very experienced British Army officers.

Although on the face of it this decision seemed reasonable and wise, it contributed hugely to the perceived failure of the Gurkha units on Operation Longcloth. The crucial area where the British Army officers struggled, was not surprisingly in communicating with their men. Weatherall was replaced almost at the last minute by Major George Dickson Dunlop of the Royal Scots. Here is how he remembered the difficulties of those times:

"The great mistake was having officers that could not speak directly and properly to their men. This placed far too greater a strain on the Column Commander. In the Gurkha columns on Longcloth there were men from four different races and languages. To get these groups to work together in times of hardship was difficult in the extreme. I have to confess that this wore me right down".

"The commander must be as fit and strong as any of his men, indeed probably more so, as all questions and decisions are ultimately down to him. This is of course how it should be, but I can tell you it is very hard. He must decide everything, right down to the last grain of rice (literally) and he must take all the blame if things go wrong".

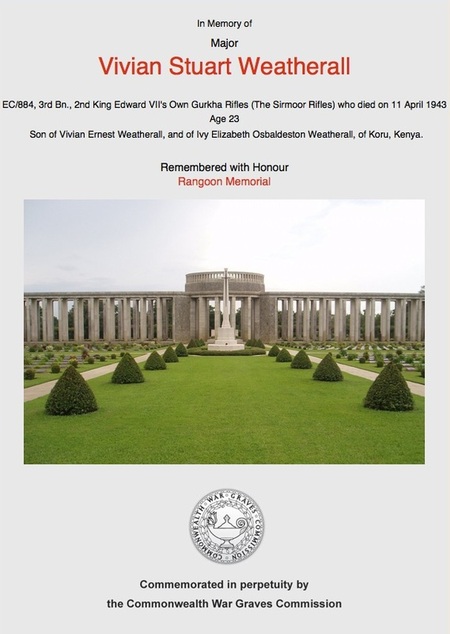

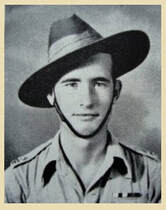

Major Vivian Stuart Weatherall

Whenever the Gurkha Riflemen from 1943 were asked to recall the names of their commanders from Operation Longcloth, one man seems to always be mentioned; 'Weatherall sahib'. As I stated previously, he was the original leader of Column 1 during training in the Central Provinces of India. He had worked hard to build up the trust and understanding of his Gurkha NCO's and in turn this respect had filtered out amongst all ranks.

EC/844 Major Vivian Stuart Weatherall had been commissioned into the Indian Army in October 1940, he studied hard at Officer Cadet classes and took time to learn the varying Gurkha dialects. This endeavour not only impressed his superiors, but also enabled his rise through the ranks, until his war time emergency commission as Major was issued in 1942/43. Weatherall's adoration for his Gurkhas was apparent to all who knew him, he understood their strong family ethic and that the operation set before them would be a difficult challenge, especially tactically.

In turn the men of 3/2 Gurkha loved him dearly.

From Ian MacHorton's book, 'Safer Than a Known Way', comes this short passage recalling the author's memories of Vivian Weatherall:

"Soon the loading operations for the Irrawaddy crossing were in full swing and we were detailed off into boatloads to await our call. Meanwhile, those detailed as rear guards were back behind us in the jungle, in position on each side of the track to give warning of pursuing Japs and to hold them off.

Captain Vivian Weatherall, a lean young officer who spoke fluent Gurkhali, and was adored by his Gurkha troops as greatly as he was admired by his brother officers, was in charge of these loading operations. So revered was he by the Gurkhas that I am certain if he had told them to swim across instead of using the boats, every man Jack of them would have set out to do so, even the non-swimmers.

Vivian had spent his adolescence on his father's tea-plantation in Assam and it was there that he had perfected his Gurkhali and had himself come to love the friendly people of the Gurkha race. As I watched him with his easy authority going about his task of allocating the men to their boats, I could not help remembering an incident which had made a deep impression upon me while we were at Jhansi awaiting our marching orders.

A three-tonner load of us had gone to the Jhansi Club for dinner and a bit of a party developed. Towards midnight the spacious teak-panelled lounge had filled up to capacity and the long polished bar had become invisible behind the scores of officers in khaki-drill. The drabness of the uniform was relieved here and there by the shimmering evening dresses and sparkling jewels of the ladies, mostly the wives of regular officers who had been stationed in India at the outbreak of war.

Harold James, Arthur Best and I, had been invited along by Major Arthur Emmett to join his party. Vivian was there as well and it was with obvious pride and pleasure that he introduced his mother, a charming woman in her late forties, with a quiet but firm voice, I found myself almost under a spell when in her presence.

Somehow I was not surprised when, after tongues had been loosened by alcohol, and barriers of shyness broken down, someone asked Mrs. Weatherall to read our palms. For some reason most of us seemed eager for this. Possibly despite the light-hearted buoyancy of the party, our subconscious minds were reaching ahead to the unknown future, and our unspoken inner-most worries were urging us to seek some foreknowledge of the dark and unknown ways that lay ahead.

There were several who knew Mrs. Weatherall from among our party and who had been greatly impressed by her talent for fore-telling the future in the happier days of peacetime. Now it was with some reluctance that she took Arthur Emmett's hand and fixed her deep intelligent eyes upon his palm. Suddenly her serious face broke into a smile as if she were overcome with relief. "It will be difficult for you," she said. "But have no fear. It is going to be all right ultimately."

She said much the same of most of the other hands that were eagerly thrust before her by men who would soon be marching out into the unknown alongside Arthur Emmett on this great and daring adventure. Then "Come on, Vivian" cried Major Emmett. "It's your turn now." Vivian had been returning from the bar with another round of drinks as Arthur Emmett light-heartedly called him into the circle to face his mother. Suddenly her face clouded. I noticed that her hand trembled a little as she took the drink Vivian handed to her. "Read my son's hand" she said, unable to hide an almost imperceptible tension from her voice. "Most certainly not. I know too much about him already."

At that we all laughed and we began to tease Vivian about what he had done on his last leave. But the smile that had accompanied his mother's remark had been a forced smile, I came away from that party with a curious feeling of apprehension for Vivian."

Sadly Ian MacHorton's concern was to be well placed.

From George Dunlop's debrief notes for Operation Longcloth, here is an eye-witness account of Vivian Weatherall's last moments:

"On the 10th April we reached the Shweli River and attempted to wade over with the help of a rope of rifle slings. This broke, so we made small rafts of bamboo. Next morning the rafts were used to ferry half a dozen men over at a time. Simultaneously the Guerrilla Platoon made a reconnaissance down stream where there was an island. They had just reached the island when the enemy opened fire from the other side. One man was killed and the rest quickly returned.

The Japanese came on up the opposite bank, and a panic ensued on our shore. Subedar Kulbir Gurung with his magnificent coolness helped quieten the men, and the bulk were withdrawn to the high ground further up-stream.

Weatherall and I remained on the bank with Kulbir and a few other men to cover the retreat of a Lance Naik and a Rifleman from the Burma Rifles, who had twice crossed the river to help retrieve some twenty or so men who were still over there. A dozen got back and the remainder disappeared into the opposite hills.

All then withdrew a short way upstream and made an observational post behind a bamboo clump. The last stragglers passed behind us, accompanied by bursts of fire from the Japanese. Only the platoon picqueting the heights above the crossing place remained. Weatherall said he was going to get them back. I ordered him to stay with me, telling him that the Jemadar in command, who was an old hand at mountain warfare, would have seen what had happened and would come round to rejoin us along the high ground, (which he in fact did do).

However, Weatherall for the first and last time disobeyed me and started to double off down the way we had just come. He had just reached the first turn in the path when there were two long bursts of fire from the opposite bank. He was hit badly in the chest and died almost instantly.

Kulbir and I returned to the column. I reported what had happened to Colonel Alexander. Within a few minutes everyone knew, many wept quite unashamedly. With Weatherall's death we lost the best officer we had, and the only one who really knew the Gurkhas of the 3/2.

Morale became non-existent and never again recovered until our last battle as a column near the River Chindwin."

So, as you can see there can be no doubting the bravery of Vivian Weatherall, nor the devotion to his Gurkha soldiers. It is testimony to his memory that so many of the ordinary soldiers from 3/2 Gurkha remember him and often him alone in their prayers. I will let his own mother, Ivy Elizabeth Weatherall conclude this sad story with her personal epitaph for her son, the words of which contain a sentiment that must have crossed the minds of many families of men lost in 1943 and where the last resting place was never known:

'Oh for a glimpse of the grave where you're laid, only to lay a flower at your head.'

Whenever the Gurkha Riflemen from 1943 were asked to recall the names of their commanders from Operation Longcloth, one man seems to always be mentioned; 'Weatherall sahib'. As I stated previously, he was the original leader of Column 1 during training in the Central Provinces of India. He had worked hard to build up the trust and understanding of his Gurkha NCO's and in turn this respect had filtered out amongst all ranks.

EC/844 Major Vivian Stuart Weatherall had been commissioned into the Indian Army in October 1940, he studied hard at Officer Cadet classes and took time to learn the varying Gurkha dialects. This endeavour not only impressed his superiors, but also enabled his rise through the ranks, until his war time emergency commission as Major was issued in 1942/43. Weatherall's adoration for his Gurkhas was apparent to all who knew him, he understood their strong family ethic and that the operation set before them would be a difficult challenge, especially tactically.

In turn the men of 3/2 Gurkha loved him dearly.

From Ian MacHorton's book, 'Safer Than a Known Way', comes this short passage recalling the author's memories of Vivian Weatherall:

"Soon the loading operations for the Irrawaddy crossing were in full swing and we were detailed off into boatloads to await our call. Meanwhile, those detailed as rear guards were back behind us in the jungle, in position on each side of the track to give warning of pursuing Japs and to hold them off.

Captain Vivian Weatherall, a lean young officer who spoke fluent Gurkhali, and was adored by his Gurkha troops as greatly as he was admired by his brother officers, was in charge of these loading operations. So revered was he by the Gurkhas that I am certain if he had told them to swim across instead of using the boats, every man Jack of them would have set out to do so, even the non-swimmers.

Vivian had spent his adolescence on his father's tea-plantation in Assam and it was there that he had perfected his Gurkhali and had himself come to love the friendly people of the Gurkha race. As I watched him with his easy authority going about his task of allocating the men to their boats, I could not help remembering an incident which had made a deep impression upon me while we were at Jhansi awaiting our marching orders.

A three-tonner load of us had gone to the Jhansi Club for dinner and a bit of a party developed. Towards midnight the spacious teak-panelled lounge had filled up to capacity and the long polished bar had become invisible behind the scores of officers in khaki-drill. The drabness of the uniform was relieved here and there by the shimmering evening dresses and sparkling jewels of the ladies, mostly the wives of regular officers who had been stationed in India at the outbreak of war.

Harold James, Arthur Best and I, had been invited along by Major Arthur Emmett to join his party. Vivian was there as well and it was with obvious pride and pleasure that he introduced his mother, a charming woman in her late forties, with a quiet but firm voice, I found myself almost under a spell when in her presence.

Somehow I was not surprised when, after tongues had been loosened by alcohol, and barriers of shyness broken down, someone asked Mrs. Weatherall to read our palms. For some reason most of us seemed eager for this. Possibly despite the light-hearted buoyancy of the party, our subconscious minds were reaching ahead to the unknown future, and our unspoken inner-most worries were urging us to seek some foreknowledge of the dark and unknown ways that lay ahead.

There were several who knew Mrs. Weatherall from among our party and who had been greatly impressed by her talent for fore-telling the future in the happier days of peacetime. Now it was with some reluctance that she took Arthur Emmett's hand and fixed her deep intelligent eyes upon his palm. Suddenly her serious face broke into a smile as if she were overcome with relief. "It will be difficult for you," she said. "But have no fear. It is going to be all right ultimately."

She said much the same of most of the other hands that were eagerly thrust before her by men who would soon be marching out into the unknown alongside Arthur Emmett on this great and daring adventure. Then "Come on, Vivian" cried Major Emmett. "It's your turn now." Vivian had been returning from the bar with another round of drinks as Arthur Emmett light-heartedly called him into the circle to face his mother. Suddenly her face clouded. I noticed that her hand trembled a little as she took the drink Vivian handed to her. "Read my son's hand" she said, unable to hide an almost imperceptible tension from her voice. "Most certainly not. I know too much about him already."

At that we all laughed and we began to tease Vivian about what he had done on his last leave. But the smile that had accompanied his mother's remark had been a forced smile, I came away from that party with a curious feeling of apprehension for Vivian."

Sadly Ian MacHorton's concern was to be well placed.

From George Dunlop's debrief notes for Operation Longcloth, here is an eye-witness account of Vivian Weatherall's last moments:

"On the 10th April we reached the Shweli River and attempted to wade over with the help of a rope of rifle slings. This broke, so we made small rafts of bamboo. Next morning the rafts were used to ferry half a dozen men over at a time. Simultaneously the Guerrilla Platoon made a reconnaissance down stream where there was an island. They had just reached the island when the enemy opened fire from the other side. One man was killed and the rest quickly returned.

The Japanese came on up the opposite bank, and a panic ensued on our shore. Subedar Kulbir Gurung with his magnificent coolness helped quieten the men, and the bulk were withdrawn to the high ground further up-stream.

Weatherall and I remained on the bank with Kulbir and a few other men to cover the retreat of a Lance Naik and a Rifleman from the Burma Rifles, who had twice crossed the river to help retrieve some twenty or so men who were still over there. A dozen got back and the remainder disappeared into the opposite hills.

All then withdrew a short way upstream and made an observational post behind a bamboo clump. The last stragglers passed behind us, accompanied by bursts of fire from the Japanese. Only the platoon picqueting the heights above the crossing place remained. Weatherall said he was going to get them back. I ordered him to stay with me, telling him that the Jemadar in command, who was an old hand at mountain warfare, would have seen what had happened and would come round to rejoin us along the high ground, (which he in fact did do).

However, Weatherall for the first and last time disobeyed me and started to double off down the way we had just come. He had just reached the first turn in the path when there were two long bursts of fire from the opposite bank. He was hit badly in the chest and died almost instantly.

Kulbir and I returned to the column. I reported what had happened to Colonel Alexander. Within a few minutes everyone knew, many wept quite unashamedly. With Weatherall's death we lost the best officer we had, and the only one who really knew the Gurkhas of the 3/2.

Morale became non-existent and never again recovered until our last battle as a column near the River Chindwin."

So, as you can see there can be no doubting the bravery of Vivian Weatherall, nor the devotion to his Gurkha soldiers. It is testimony to his memory that so many of the ordinary soldiers from 3/2 Gurkha remember him and often him alone in their prayers. I will let his own mother, Ivy Elizabeth Weatherall conclude this sad story with her personal epitaph for her son, the words of which contain a sentiment that must have crossed the minds of many families of men lost in 1943 and where the last resting place was never known:

'Oh for a glimpse of the grave where you're laid, only to lay a flower at your head.'

Update 09/12/2013.

Another Gurkha Rifleman to witness the untimely death of Major Weatherall was Subedar-Major Siblal Thapa of Column 2. Siblal, who was a highly responsible and well respected senior Gurkha Officer from the battalion, had survived the horrors of the battle at Kyaikthin and had led away the remnants of his defeated column to the relative safety of the formerly agreed rendezvous location at Taungbin.

It was here that he joined up with Major Dunlop and Column 1, renewing his acquaintance with 'Weatherall Sahib' and the remaining Gurkhas of Southern Group. After a long and arduous struggle Siblal finally made it back to India in mid-May 1943. When he had fully recovered from his time on Operation Longcloth he wrote down some of his experiences in the form of a narrative diary. This was then published in the Regimental Newsletter some months later.

From this diary comes Siblal's description of the events leading up to the Major's death on the 11th April 1943:

"We had rested in the nullah of Mulan Chaung near the village of Nampaw. From the villagers fields we removed some pumpkins and water melons. The next day we wandered off the map to the east, but sent out a patrol towards the Shweli River which we reached on the 10th.

At this point the river was about 100 yards wide and 20 feet deep. The C.O. gave orders that we would make rafts from bundles of bamboo and make a tow rope by joining together all the rifle slings. With this we started the first party across. The rope was intended to pull the raft from one bank the other and then back again.

When the first party was half way across the river the rope parted and it became dark by the time these people were rescued. On the 11th at dawn we again attempted the crossing but we had only got a few men across when the Japs attacked us. We held them off until all the men except five recrossed the river to our side again, then the C.O. ordered us to retire at once towards a small hill.

I did not see the five men who were left on the far side of the river again. NB. Lance Naik Jitbahadur Rana was one of the men left stranded on the far bank, he eventually made his way back to India, having at least once escaped Japanese custody. To read about Jitbahadur Rana and his award of the IDSM, please click on the following link:

Jitbahadur Rana. (third story on the page).

Siblal Thapa continues:

"Whilst retiring Capt. Weatherall kept on worrying about the men left behind. Eventually he went back with his orderly to find them. The orderly came back alone and reported to the C.O. that the Sahib had been killed outright by a Jap machine gun burst. After this we missed the Sahib greatly as he was the man who gave us our orders.

When we had got clear of the enemy the C.O. had a conference with all British and Gurkha Officers. He said it was useless to try and get through the enemy area, so we should keep going due east. That night and on the 14th and 15th we marched through the hill tracts well off the maps. We had eaten our last cooked meal at Man Htun on the 9th so my tummy was beginning to think that my throat was cut once again."

My thanks must go to the Gurkha Museum at Winchester for their help and co-operation with this additional information about Major Vivian Weatherall.

Another Gurkha Rifleman to witness the untimely death of Major Weatherall was Subedar-Major Siblal Thapa of Column 2. Siblal, who was a highly responsible and well respected senior Gurkha Officer from the battalion, had survived the horrors of the battle at Kyaikthin and had led away the remnants of his defeated column to the relative safety of the formerly agreed rendezvous location at Taungbin.

It was here that he joined up with Major Dunlop and Column 1, renewing his acquaintance with 'Weatherall Sahib' and the remaining Gurkhas of Southern Group. After a long and arduous struggle Siblal finally made it back to India in mid-May 1943. When he had fully recovered from his time on Operation Longcloth he wrote down some of his experiences in the form of a narrative diary. This was then published in the Regimental Newsletter some months later.

From this diary comes Siblal's description of the events leading up to the Major's death on the 11th April 1943:

"We had rested in the nullah of Mulan Chaung near the village of Nampaw. From the villagers fields we removed some pumpkins and water melons. The next day we wandered off the map to the east, but sent out a patrol towards the Shweli River which we reached on the 10th.

At this point the river was about 100 yards wide and 20 feet deep. The C.O. gave orders that we would make rafts from bundles of bamboo and make a tow rope by joining together all the rifle slings. With this we started the first party across. The rope was intended to pull the raft from one bank the other and then back again.

When the first party was half way across the river the rope parted and it became dark by the time these people were rescued. On the 11th at dawn we again attempted the crossing but we had only got a few men across when the Japs attacked us. We held them off until all the men except five recrossed the river to our side again, then the C.O. ordered us to retire at once towards a small hill.

I did not see the five men who were left on the far side of the river again. NB. Lance Naik Jitbahadur Rana was one of the men left stranded on the far bank, he eventually made his way back to India, having at least once escaped Japanese custody. To read about Jitbahadur Rana and his award of the IDSM, please click on the following link:

Jitbahadur Rana. (third story on the page).

Siblal Thapa continues:

"Whilst retiring Capt. Weatherall kept on worrying about the men left behind. Eventually he went back with his orderly to find them. The orderly came back alone and reported to the C.O. that the Sahib had been killed outright by a Jap machine gun burst. After this we missed the Sahib greatly as he was the man who gave us our orders.

When we had got clear of the enemy the C.O. had a conference with all British and Gurkha Officers. He said it was useless to try and get through the enemy area, so we should keep going due east. That night and on the 14th and 15th we marched through the hill tracts well off the maps. We had eaten our last cooked meal at Man Htun on the 9th so my tummy was beginning to think that my throat was cut once again."

My thanks must go to the Gurkha Museum at Winchester for their help and co-operation with this additional information about Major Vivian Weatherall.

Major George Dunlop MC.

Major George Dunlop MC.

Update 19/12/2020.

From the writings of Major George Dunlop in later life, comes this short, but quite detailed account of the death of Vivian Weatherall, which confirms the various eye-witness accounts from the narrative above:

At the Shweli, my Subedar Kulbir Thapa, Weatherall and I were behind a bamboo screen supervising the column’s withdrawal from the river. One platoon were positioned in the rise above the crossing place covering our rear. After all but one of the stragglers had gone past, Weatherall said that he must see to it that this platoon were now told to withdraw. I told him to remain with me and that the Jemadar in command of the platoon was well capable of dealing with the situation, which indeed he did do. Unfortunately, Weatherall had already jumped clear of our cover, and was killed just a few feet in front of us.

From the writings of Major George Dunlop in later life, comes this short, but quite detailed account of the death of Vivian Weatherall, which confirms the various eye-witness accounts from the narrative above:

At the Shweli, my Subedar Kulbir Thapa, Weatherall and I were behind a bamboo screen supervising the column’s withdrawal from the river. One platoon were positioned in the rise above the crossing place covering our rear. After all but one of the stragglers had gone past, Weatherall said that he must see to it that this platoon were now told to withdraw. I told him to remain with me and that the Jemadar in command of the platoon was well capable of dealing with the situation, which indeed he did do. Unfortunately, Weatherall had already jumped clear of our cover, and was killed just a few feet in front of us.

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2013.