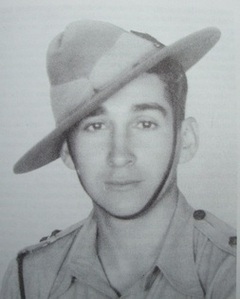

Rifleman Tilbahadur Thapa

Tilbahadur Thapa (Image courtesy of the GWT).

Tilbahadur Thapa (Image courtesy of the GWT).

Tilbahadur Thapa was a young and inexperienced Gurkha Rifleman in 1943. He was a part of the 3/2 GR battalion which formed part of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade on Operation Longcloth. He was attached to Column 3 that year, this is his epic story of survival:

"We crossed the Brahmaputra River in boats and continued by rail to Gauhati. We met a wagon load of Habsis (African troops) who laughed at us because we were so small. We moved by day and night to Manipur and stayed at Brigade HQ. The Nagas were all engaged on building roads. We were there three weeks.

The Subedar Major took all those too weak for war, the blind, lame and ill, all malingerers in my view, back to Dehra Dun. We went on to Tamu, another three miles away, and held a ceremonial parade for a General. The whole Brigade paraded and the General spoke in English and Khaskura (Indic Nepalese dialect). After that companies were sent to different places. The Officer Commanding C Company of 3/2 GR's name sounded like 'Calpat' (clearly meant to be Calvert), but he was known by his nickname, 'Brigade Major'.

NB. The OC of C Company was in fact Captain George W. Silcock. Captain Silcock was the original commander of Chindit Column 3 during training, but had been replaced just before the operation began by Major Mike Calvert. G.W.N. Silcock died at Chittagong on 14th January 1945 from a broken neck caused by falling from a first floor of a house at Akyab while sleep walking.

Tilbahadur continues:

I was now in the 3-inch Mortar Platoon. Each Rifle Company had two 3-inch mortars with it. We were in Tamu for two days. There was a large dry river there. On the other side the terrain was flat and covered in scrub and jungle. On the third day we advanced to a village near the river and I asked if any Japanese were there. We were told they sometimes came there, we went on day and night, with mules and horses.

We reached a hill early one morning where we stopped to brew up tea and I started cooking myself a snack as well but a firefight immediately started. I put my half-cooked food in my pocket and on we went, day and night and day and night through the jungle. Monkey calls sounded everywhere. One night at 2100 hours we reached the banks of the Irrawaddy and stayed near a bamboo clump. We were told that we'd cross at 0800 hours next morning and to keep quiet, no coughing, no smoking except under cover, because the Japanese were on the far side.

Next morning we loaded our heavy weapons on mules and horses and half of C Company moved upstream. As we moved out bombs started falling, "grum-kigrum-grum-kigrum", and small arms fire, "parara-parara-parara", came from the far bank. Nonstop it came, "parara-parara-parara", and hit the bamboo and undergrowth, "chim-chim-chim-chim-chuiaa-chuiaa-chuiaa". Second in Command of C Company, Subedar Siribhakta, his orderly and myself fell to the ground and many of the Company were killed. Havildar Hirasing, the Platoon Havildar, was hiding somewhere else. Some men scattered and went, where I knew not.

Many animals were killed; many, including the one elephant, ran away. The Japanese pinned us down and we could not fire back. The OC sahib (Harold James) shouted "Havildar Hirasing, where are the 3-inch mortarmen? Are they there?" "Yes, yes," he shouted back. The OC told him to fire the mortars, but I shouted back that the Nos. 1 and 4 were dead. "I'm by myself. No 2 is somewhere with the animals."

We told ourselves we had to fire back and we tried to but we could not lift our heads. Bullets zinged all around us. Subedar Siribhakta's orderly stood up and was immediately shot. His body fell on top of us, covering us in blood, he was babbling as he died. The bullets fell around us like hailstones. Siribhakta cursed us for not firing but kept his own head down. Our ammunition was with us but the mortars were on mules which were dead or scattered. Which one of us remaining three was to fetch them?

We were all squatting down and I decided that as I'd have to die one day why not die now. I got up to bring the tubes with bullets zinging around my head. I was not hit. I pulled a mortar, bipod, base-plate and ammunition from a dead mule and went into action. The OC sahib shouted "Fire, on a line of 11 o'clock, with a range of 500 yards." I fired one round then thought of our men being in that area so fired another at 700 yards. Even heavier fire came from the Japanese. On and on the bullets came and the OC sahib shouted "A little right, 12 o'clock." I fired by myself, as the others were still hiding. The second bomb hit the Japanese position and they stopped firing. And then our fire opened, "bhutu-tu-tu-bhutu-tu-tu, bhutu-tu-tu". The OC sahib shouted "Stop" so I stopped. Then other mortar sections also stopped firing.

Our wounded men were groaning. We collected as many weapons as possible from the dead men and dead animals and buried them in a pit. We also buried the dead. It took us three days to cross the river and we gave a lot of covering fire. I crossed over last of all. We took up positions on both flanks on the far bank. We met our Platoon Commander and I sternly rebuked him, reminding him he was under his oath of loyalty and how was it that he had hidden and not fought back.

We were only three and even then I was the only one to fire the mortar. We had no rations and were so hungry we were utterly exhausted. Some Burmese villagers brought up rations for the Japanese, sacks of rice, beans and other vegetables, which we captured. The Burmese ran away. We were so hungry we ate the rice uncooked. We only left the food which we did not recognise.

After feeding we went to the top of a high hill and sent a message for an airdrop and reinforcements. When they came they were from Abbottabad, 6 GR I think. We took up all-round positions and put up smoke from three places having been told we'd get an airdrop at 2200 hours. A fighter aircraft came first and the supply aeroplanes followed it. We only managed to distribute the rations the next day. We were ordered on to a village near the River Syaulilebar (Tilbahadur could mean the Shweli, but this is not overly clear). On our way we walked through a forest with a red mud floor. It was very hot and there was no water so we were very thirsty. We had not been allowed to drink from our water bottles all day.

"We crossed the Brahmaputra River in boats and continued by rail to Gauhati. We met a wagon load of Habsis (African troops) who laughed at us because we were so small. We moved by day and night to Manipur and stayed at Brigade HQ. The Nagas were all engaged on building roads. We were there three weeks.

The Subedar Major took all those too weak for war, the blind, lame and ill, all malingerers in my view, back to Dehra Dun. We went on to Tamu, another three miles away, and held a ceremonial parade for a General. The whole Brigade paraded and the General spoke in English and Khaskura (Indic Nepalese dialect). After that companies were sent to different places. The Officer Commanding C Company of 3/2 GR's name sounded like 'Calpat' (clearly meant to be Calvert), but he was known by his nickname, 'Brigade Major'.

NB. The OC of C Company was in fact Captain George W. Silcock. Captain Silcock was the original commander of Chindit Column 3 during training, but had been replaced just before the operation began by Major Mike Calvert. G.W.N. Silcock died at Chittagong on 14th January 1945 from a broken neck caused by falling from a first floor of a house at Akyab while sleep walking.

Tilbahadur continues:

I was now in the 3-inch Mortar Platoon. Each Rifle Company had two 3-inch mortars with it. We were in Tamu for two days. There was a large dry river there. On the other side the terrain was flat and covered in scrub and jungle. On the third day we advanced to a village near the river and I asked if any Japanese were there. We were told they sometimes came there, we went on day and night, with mules and horses.

We reached a hill early one morning where we stopped to brew up tea and I started cooking myself a snack as well but a firefight immediately started. I put my half-cooked food in my pocket and on we went, day and night and day and night through the jungle. Monkey calls sounded everywhere. One night at 2100 hours we reached the banks of the Irrawaddy and stayed near a bamboo clump. We were told that we'd cross at 0800 hours next morning and to keep quiet, no coughing, no smoking except under cover, because the Japanese were on the far side.

Next morning we loaded our heavy weapons on mules and horses and half of C Company moved upstream. As we moved out bombs started falling, "grum-kigrum-grum-kigrum", and small arms fire, "parara-parara-parara", came from the far bank. Nonstop it came, "parara-parara-parara", and hit the bamboo and undergrowth, "chim-chim-chim-chim-chuiaa-chuiaa-chuiaa". Second in Command of C Company, Subedar Siribhakta, his orderly and myself fell to the ground and many of the Company were killed. Havildar Hirasing, the Platoon Havildar, was hiding somewhere else. Some men scattered and went, where I knew not.

Many animals were killed; many, including the one elephant, ran away. The Japanese pinned us down and we could not fire back. The OC sahib (Harold James) shouted "Havildar Hirasing, where are the 3-inch mortarmen? Are they there?" "Yes, yes," he shouted back. The OC told him to fire the mortars, but I shouted back that the Nos. 1 and 4 were dead. "I'm by myself. No 2 is somewhere with the animals."

We told ourselves we had to fire back and we tried to but we could not lift our heads. Bullets zinged all around us. Subedar Siribhakta's orderly stood up and was immediately shot. His body fell on top of us, covering us in blood, he was babbling as he died. The bullets fell around us like hailstones. Siribhakta cursed us for not firing but kept his own head down. Our ammunition was with us but the mortars were on mules which were dead or scattered. Which one of us remaining three was to fetch them?

We were all squatting down and I decided that as I'd have to die one day why not die now. I got up to bring the tubes with bullets zinging around my head. I was not hit. I pulled a mortar, bipod, base-plate and ammunition from a dead mule and went into action. The OC sahib shouted "Fire, on a line of 11 o'clock, with a range of 500 yards." I fired one round then thought of our men being in that area so fired another at 700 yards. Even heavier fire came from the Japanese. On and on the bullets came and the OC sahib shouted "A little right, 12 o'clock." I fired by myself, as the others were still hiding. The second bomb hit the Japanese position and they stopped firing. And then our fire opened, "bhutu-tu-tu-bhutu-tu-tu, bhutu-tu-tu". The OC sahib shouted "Stop" so I stopped. Then other mortar sections also stopped firing.

Our wounded men were groaning. We collected as many weapons as possible from the dead men and dead animals and buried them in a pit. We also buried the dead. It took us three days to cross the river and we gave a lot of covering fire. I crossed over last of all. We took up positions on both flanks on the far bank. We met our Platoon Commander and I sternly rebuked him, reminding him he was under his oath of loyalty and how was it that he had hidden and not fought back.

We were only three and even then I was the only one to fire the mortar. We had no rations and were so hungry we were utterly exhausted. Some Burmese villagers brought up rations for the Japanese, sacks of rice, beans and other vegetables, which we captured. The Burmese ran away. We were so hungry we ate the rice uncooked. We only left the food which we did not recognise.

After feeding we went to the top of a high hill and sent a message for an airdrop and reinforcements. When they came they were from Abbottabad, 6 GR I think. We took up all-round positions and put up smoke from three places having been told we'd get an airdrop at 2200 hours. A fighter aircraft came first and the supply aeroplanes followed it. We only managed to distribute the rations the next day. We were ordered on to a village near the River Syaulilebar (Tilbahadur could mean the Shweli, but this is not overly clear). On our way we walked through a forest with a red mud floor. It was very hot and there was no water so we were very thirsty. We had not been allowed to drink from our water bottles all day.

Tilbahadur continues:

We were only allowed to drink after patrols had secured the river area. We got to the river at around 1800 hours. When we saw the village we mounted our mortars and the remainder advanced. At night we camped there and started to cook our meal. We were told to move at 0600 hours next morning. As we were cooking, the Japanese attacked us on all sides with small arms fire, we had mistakenly stopped in the middle of a Japanese position.

At midnight they attacked us and a free-for-all developed — man to man, kukris, bayonets, swords, hand-to-hand, Gurkhas killing Gurkhas and Japanese killing Japanese by mistake in the confusion. Both sides fired bombs blindly, even killing each other. It was like a nightmare, so noisy was it that we could not hear each other clearly. The jungle was set alight. Pandemonium all round.

The jungle reverberated with our shouts. Around 0200 hours, we saw a man armed only with a raised kukri running towards us. We thought he was mad, but he came to give a message that his platoon was completely surrounded and could not move forwards or backwards. "How far in front are you" we asked. "About 500 yards in front," he answered. We were also fighting, but I reckoned that if I fired at 800 yards I'd hit the Japanese.

Subedar Siribhakta mounted his weapon and fired rounds one at a time right and I one at a time left. We fired and fired, working by the light of the forest fire. The platoon in front managed to withdraw. No one had any idea of casualties, dead or wounded. The next day we took stock of the situation and by evening we were organised enough to move off into the night. We walked till dawn when we stopped in some low-lying ground. We set up our wireless and were told to return to India. We went back the same way and, on reaching the Irrawaddy, started making boats and rafts from cane and bamboo.

NB. Calvert, against his better judgement decided to split the men up into smaller dispersal parties of 25-30 men in each. Subedar Siribhakta was given command of one of the dispersal groups which included Tilbahadur and Burma Rifle officer Jemadar Cameron and personnel from Column 3's Support Platoon.

Tilbahadur's story continues:

By late evening we were ready to cross but were fired on from the opposite bank. We scattered and a British Sergeant was shot. He fell over. He took some gold out of his shirt pocket and offered it to me as he was about to die, but I declined it because I was in a hurry to join my platoon as we moved to some cover. Eventually we reached some high ground and asked for rations to be dropped the next day. We were told to conserve our matches and salt but no airdrop came. We were also told to eat any and everything we came across, horses, elephants, buffaloes and cows; once we got back to Kunraghat we would do 'pani patya' (a Gurkha purification ceremony) for eating forbidden meat.

We returned to our section formations. The OC sahib said he'd stay with the British troops and a Burmese Officer (Jemadar Cameron) and his Burmese soldiers would stay with us Gurkhas and we would have to obey him. Our first task was to cross the Irrawaddy. We were to bury all heavy weapons and only take light automatics, Stens and Tommy Guns, and Rifles. We were to let all our animals go free. The British battalion moved off and so did we, but we soon became two groups, the Burmese by themselves and we Gurkhas by ourselves, making our best way forward.

Subedar Siribhakta told us not to move in a group but to make our way individually so as to avoid leaving tracks the Japanese could follow. I found myself in a group of six, all muleteers who knew nothing. I made all the decisions. One of them was my wife's elder brother. I had a compass. We found wood-apples and ate them. There was nothing else. Later we killed and ate a deer. We lived off the land. We tried nettles but they made us piss many times during the night, always hot. We moved like that for three months. We were afraid of elephants, bears and apes.

Sometimes we slept in trees and sometimes on the ground, where possible in caves. By now it was the rainy season and we eked out our matches and salt. We took counsel. We had some rupee money so we decided to go to a village, buy some rations and if possible rejoin our troops. I put 180 degrees on my compass and aimed for a village called Waibang, remembered from before. I said "If we meet up with our forces, we'll get home; if we meet the enemy, let us die."

We had no hope of survival. We went on for one and a half miles and saw the village. We lay up, hiding, as we watched it. That night we slept separately so that we would not all be killed at once. Next morning we joined up and discussed if we should go into the village or not. We decided that three of us would go and the other three would stay behind. We took off our socks and boots and all clothing that would identify us as Indian Army, and carrying our rifles, I took two others into the village. I had told the other three I would bring back rations if at all possible.

Staying on one side of a dry ravine at the village edge, I called out to the villagers in Burmese, if there was any food. I spoke some Burmese. A Burman sent us to a storehouse. The men there asked us, in Hindi, where we had come from. "How much do you want?" they asked. "I'll take one sack of everything," I replied.

They told us the price by sign language. One sack of rice for eight rupees. By then the other three had joined us so we were six again. We were all given a large glass of tea. "Drink up, we are friends," we were told. "Drink up quickly, take your rations and go." We had only drunk half our tea when a meal of rice, meat and vegetables was brought for us, in six dishes. "How hungry you must be. How much dukha (trouble) you must have had in the jungle," they said.

As I drank my tea I said to the others there might be poison in the food. "No worry," they said, "if we die, we die." We still had our rifles slung and we started eating. "Eat up, lads, we are fated to die today," I said and one answered, "if we die we die, if we don't we don't." We started to eat. We were told not to hurry. "Even prisoners can eat without weapons. Put your weapons behind you and eat comfortably. The Japanese don't come often, only occasionally," we were told. We put our weapons behind us and someone came and took them away. I turned round and asked why they had been taken away and was told that, were the Japanese to come suddenly and see them, it would be dangerous. It were better to hide them.

We thought that, though we had escaped from enemy bullets, now, with no weapons, we were in the enemy's hands. We were bound to die now. But we had two grenades each in our pockets. The villagers surrounded us. We were caught. We thought we'd use the grenades on them. But no matter how many of them would die we would be captured, our chests cut open and raw chillies be rubbed in. So we didn't throw the grenades. We kept them hidden. Three of the others, including my wife's elder brother, said, "No, let's kill them and die ourselves," but I stopped them by saying, "Let's surrender and see what happens. If they kill us, they kill us and if they don't, the gods will save us."

My wife's elder brother and one other said they weren't going to stay and tried to move outside but were prevented by a crowd of Burmese, ranging from eight-year-olds to 84-year-olds, armed with all sorts of knives. A Burman killed my wife's elder brother with a heavy-bladed knife and cut his body into pieces, throwing his hat and shirt away. His remains were thrown into a ditch. The Burmese bound the second man and knocked him over. They fetched a cart, put us four in one corner and threw the bound man in after us. They saw him as trouble and a bad man.

We were taken into the jungle and handed over to the Japanese, still in the cart, were stripped. We wore only underpants but were allowed to keep our money. That night we reached a town and were fed. Then off again, for a day and a night. Next night we reached Mogok. On the way we hid from Allied aircraft.

We were only allowed to drink after patrols had secured the river area. We got to the river at around 1800 hours. When we saw the village we mounted our mortars and the remainder advanced. At night we camped there and started to cook our meal. We were told to move at 0600 hours next morning. As we were cooking, the Japanese attacked us on all sides with small arms fire, we had mistakenly stopped in the middle of a Japanese position.

At midnight they attacked us and a free-for-all developed — man to man, kukris, bayonets, swords, hand-to-hand, Gurkhas killing Gurkhas and Japanese killing Japanese by mistake in the confusion. Both sides fired bombs blindly, even killing each other. It was like a nightmare, so noisy was it that we could not hear each other clearly. The jungle was set alight. Pandemonium all round.

The jungle reverberated with our shouts. Around 0200 hours, we saw a man armed only with a raised kukri running towards us. We thought he was mad, but he came to give a message that his platoon was completely surrounded and could not move forwards or backwards. "How far in front are you" we asked. "About 500 yards in front," he answered. We were also fighting, but I reckoned that if I fired at 800 yards I'd hit the Japanese.

Subedar Siribhakta mounted his weapon and fired rounds one at a time right and I one at a time left. We fired and fired, working by the light of the forest fire. The platoon in front managed to withdraw. No one had any idea of casualties, dead or wounded. The next day we took stock of the situation and by evening we were organised enough to move off into the night. We walked till dawn when we stopped in some low-lying ground. We set up our wireless and were told to return to India. We went back the same way and, on reaching the Irrawaddy, started making boats and rafts from cane and bamboo.

NB. Calvert, against his better judgement decided to split the men up into smaller dispersal parties of 25-30 men in each. Subedar Siribhakta was given command of one of the dispersal groups which included Tilbahadur and Burma Rifle officer Jemadar Cameron and personnel from Column 3's Support Platoon.

Tilbahadur's story continues:

By late evening we were ready to cross but were fired on from the opposite bank. We scattered and a British Sergeant was shot. He fell over. He took some gold out of his shirt pocket and offered it to me as he was about to die, but I declined it because I was in a hurry to join my platoon as we moved to some cover. Eventually we reached some high ground and asked for rations to be dropped the next day. We were told to conserve our matches and salt but no airdrop came. We were also told to eat any and everything we came across, horses, elephants, buffaloes and cows; once we got back to Kunraghat we would do 'pani patya' (a Gurkha purification ceremony) for eating forbidden meat.

We returned to our section formations. The OC sahib said he'd stay with the British troops and a Burmese Officer (Jemadar Cameron) and his Burmese soldiers would stay with us Gurkhas and we would have to obey him. Our first task was to cross the Irrawaddy. We were to bury all heavy weapons and only take light automatics, Stens and Tommy Guns, and Rifles. We were to let all our animals go free. The British battalion moved off and so did we, but we soon became two groups, the Burmese by themselves and we Gurkhas by ourselves, making our best way forward.

Subedar Siribhakta told us not to move in a group but to make our way individually so as to avoid leaving tracks the Japanese could follow. I found myself in a group of six, all muleteers who knew nothing. I made all the decisions. One of them was my wife's elder brother. I had a compass. We found wood-apples and ate them. There was nothing else. Later we killed and ate a deer. We lived off the land. We tried nettles but they made us piss many times during the night, always hot. We moved like that for three months. We were afraid of elephants, bears and apes.

Sometimes we slept in trees and sometimes on the ground, where possible in caves. By now it was the rainy season and we eked out our matches and salt. We took counsel. We had some rupee money so we decided to go to a village, buy some rations and if possible rejoin our troops. I put 180 degrees on my compass and aimed for a village called Waibang, remembered from before. I said "If we meet up with our forces, we'll get home; if we meet the enemy, let us die."

We had no hope of survival. We went on for one and a half miles and saw the village. We lay up, hiding, as we watched it. That night we slept separately so that we would not all be killed at once. Next morning we joined up and discussed if we should go into the village or not. We decided that three of us would go and the other three would stay behind. We took off our socks and boots and all clothing that would identify us as Indian Army, and carrying our rifles, I took two others into the village. I had told the other three I would bring back rations if at all possible.

Staying on one side of a dry ravine at the village edge, I called out to the villagers in Burmese, if there was any food. I spoke some Burmese. A Burman sent us to a storehouse. The men there asked us, in Hindi, where we had come from. "How much do you want?" they asked. "I'll take one sack of everything," I replied.

They told us the price by sign language. One sack of rice for eight rupees. By then the other three had joined us so we were six again. We were all given a large glass of tea. "Drink up, we are friends," we were told. "Drink up quickly, take your rations and go." We had only drunk half our tea when a meal of rice, meat and vegetables was brought for us, in six dishes. "How hungry you must be. How much dukha (trouble) you must have had in the jungle," they said.

As I drank my tea I said to the others there might be poison in the food. "No worry," they said, "if we die, we die." We still had our rifles slung and we started eating. "Eat up, lads, we are fated to die today," I said and one answered, "if we die we die, if we don't we don't." We started to eat. We were told not to hurry. "Even prisoners can eat without weapons. Put your weapons behind you and eat comfortably. The Japanese don't come often, only occasionally," we were told. We put our weapons behind us and someone came and took them away. I turned round and asked why they had been taken away and was told that, were the Japanese to come suddenly and see them, it would be dangerous. It were better to hide them.

We thought that, though we had escaped from enemy bullets, now, with no weapons, we were in the enemy's hands. We were bound to die now. But we had two grenades each in our pockets. The villagers surrounded us. We were caught. We thought we'd use the grenades on them. But no matter how many of them would die we would be captured, our chests cut open and raw chillies be rubbed in. So we didn't throw the grenades. We kept them hidden. Three of the others, including my wife's elder brother, said, "No, let's kill them and die ourselves," but I stopped them by saying, "Let's surrender and see what happens. If they kill us, they kill us and if they don't, the gods will save us."

My wife's elder brother and one other said they weren't going to stay and tried to move outside but were prevented by a crowd of Burmese, ranging from eight-year-olds to 84-year-olds, armed with all sorts of knives. A Burman killed my wife's elder brother with a heavy-bladed knife and cut his body into pieces, throwing his hat and shirt away. His remains were thrown into a ditch. The Burmese bound the second man and knocked him over. They fetched a cart, put us four in one corner and threw the bound man in after us. They saw him as trouble and a bad man.

We were taken into the jungle and handed over to the Japanese, still in the cart, were stripped. We wore only underpants but were allowed to keep our money. That night we reached a town and were fed. Then off again, for a day and a night. Next night we reached Mogok. On the way we hid from Allied aircraft.

The story goes on:

At Mogok we were fed with the remains of some burnt rice, scraped from the bottom of the cooking pot. Then we were taken to a prison where there were about twenty other Gurkhas. We asked about each other. Next day we were left alone and the following morning some Chinese were brought along and we five were called out by the Japanese who gave us picks and shovels. We dug a deep pit. One Chinese was brought to the pit and we were ordered out of it. The Chinese was bayonetted in the stomach and fell into the pit. We were ordered to bury him alive.

Aah! I thought, that will be our fate. We dumped our tools and were led off back to the jail and given something like biscuits and water. Our friends asked us what had happened and I told them. We decided to ask to be shot instead. Someone said that how they killed us was up to them. That evening our captors told us was that they would bring some Japanese Officers — we called them Subedars and Jemadars because they had three or two rank stars on their uniforms — to us on the morrow. Next morning the Japanese took us outside. They were dressed in smart uniform. The jail commander turned to us and said "Look how smart our men are. You are useless mouths."

He asked us how many Japanese we had killed. We told him we had no idea. He told us to put our hands up and took our money away from where we had hidden it and gave it to the Burmese. We were locked in the jail for another three days and three nights, then marched off, walking day and night, to Rangoon Jail. We were put into the ground floor and the officers were on the upper floor. There were 700 people of all kinds bound arm to arm, lying on their backs, unable to stretch their legs. A trench from under them took away their urine and faeces.

NB: The Gurkha soldiers were held in Block 2 of the jail separated from all the other nationalities present. Occasionally messages did pass through to their British Army comrades detained in Blocks 3 and 6, informing them of new arrivals in the jail and any latest news about the war.

We were also trussed up like that. The smell was dreadful; mosquitoes went "gu-nu-nu-nu-nu-nu" all night and flies buzzed all day. And so hot! We were let loose after one month and taken out. We were told to fall in making two ranks and lectured by a Japanese and a Burmese Officer who asked us if we were willing to work for them or wanted to go back to jail. "Those who want to work put up your hands." Every hand went up as we opted to work. We were taken into wooded country full of tethered elephants and horses and our task was to look after them by preparing their feed and clearing up their dung, three times a day. We worked till 2200 hours each day.

We lived in long huts and were woken up every morning at 0200 hours with the command "Shaw-shaw-shaw" and made to prepare the fodder until 0600 hours, when the Japanese commanded us to feed them, "Mis-mis-mis". After that it was our turn to feed with some rice and gruel. We were not allowed to use our hands but had to use small sticks. If we ate with our hands they hit us in the face.

At last the weather became colder, much colder. Among the 700 were some Burmese and one morning, before 0200 hours, one older Burman had collected kindling and had lit a fire. When the Japanese came in the Burman and I were warming ourselves. He asked where the others were. I told him I didn't know but they were probably asleep somewhere. The Japanese sentry started hitting me in the face. The old Burman ran away. I was so angry I picked up a brick and, whether I died or not, made to throw it at the Japanese, who ran away. The Japanese told the other Gurkhas what I had done and that they were to watch me being shot when it was light.

We went out as normal to feed the animals and at our meal time I was called over by that Japanese to have a meal with him, but I was so angry I did not go. A 3/2 GR Subedar and Jemadar had also been captured and the Japanese said that these two would be told of our faults the next day and they would look after us. We all thought we'd be killed. "Why be afraid?" I asked the others. "Only I am to be killed as I am the only one who has done wrong. You have done nothing wrong," I told them.

Next day at noon the Subedar and Jemadar came. The Japanese fell in on one side and the Gurkhas on the other side. The case was discussed and the Japanese Officer ordered the sentry and the person who had done wrong to step forward. I stepped in front and pointed out the sentry who had hit me and called him forward. I explained what had happened in Hindi as the Japanese Officer spoke Hindi. "He always hits everybody every morning and many cheeks are swollen from continual hitting. My cheeks are very swollen. As I have done no wrong and have worked well, when he hit me I picked up the brick." I explained what I had said at the time. The sentry said I had driven the other prisoners outside. My answer was I was a coolie so were the others, so how could I send them away? The Japanese Officer told the sentry that we Gurkhas were there to help,

not to be hit. "Why have you hit them so much? Everybody's cheeks are swollen." The Japanese Officer then struck the sentry very hard and the other Japanese took him away.

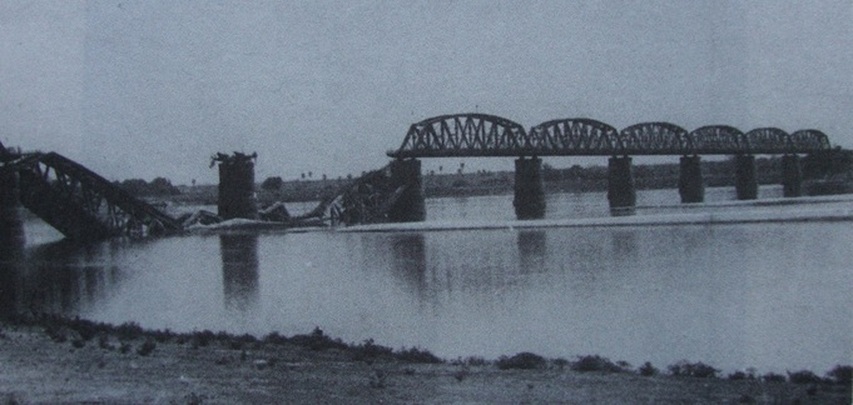

A new sentry came in his place. The Japanese Officer told the other Japanese that, "The Gurkhas' mothers and fathers are not here and there are no mail facilities and so no one knows they are here. They are prisoners and have to be here. Our fathers and mothers are not here either but we are here to fight. Will we die or stay alive? These men will have to work as long as they're here. If they are sick they must be treated." Some time after that we were moved and eventually reached Mandalay where we saw the Irrawaddy, vast as the sea. The bridge had been smashed and we spent the night crossing in boats, some way downstream.

At Mogok we were fed with the remains of some burnt rice, scraped from the bottom of the cooking pot. Then we were taken to a prison where there were about twenty other Gurkhas. We asked about each other. Next day we were left alone and the following morning some Chinese were brought along and we five were called out by the Japanese who gave us picks and shovels. We dug a deep pit. One Chinese was brought to the pit and we were ordered out of it. The Chinese was bayonetted in the stomach and fell into the pit. We were ordered to bury him alive.

Aah! I thought, that will be our fate. We dumped our tools and were led off back to the jail and given something like biscuits and water. Our friends asked us what had happened and I told them. We decided to ask to be shot instead. Someone said that how they killed us was up to them. That evening our captors told us was that they would bring some Japanese Officers — we called them Subedars and Jemadars because they had three or two rank stars on their uniforms — to us on the morrow. Next morning the Japanese took us outside. They were dressed in smart uniform. The jail commander turned to us and said "Look how smart our men are. You are useless mouths."

He asked us how many Japanese we had killed. We told him we had no idea. He told us to put our hands up and took our money away from where we had hidden it and gave it to the Burmese. We were locked in the jail for another three days and three nights, then marched off, walking day and night, to Rangoon Jail. We were put into the ground floor and the officers were on the upper floor. There were 700 people of all kinds bound arm to arm, lying on their backs, unable to stretch their legs. A trench from under them took away their urine and faeces.

NB: The Gurkha soldiers were held in Block 2 of the jail separated from all the other nationalities present. Occasionally messages did pass through to their British Army comrades detained in Blocks 3 and 6, informing them of new arrivals in the jail and any latest news about the war.

We were also trussed up like that. The smell was dreadful; mosquitoes went "gu-nu-nu-nu-nu-nu" all night and flies buzzed all day. And so hot! We were let loose after one month and taken out. We were told to fall in making two ranks and lectured by a Japanese and a Burmese Officer who asked us if we were willing to work for them or wanted to go back to jail. "Those who want to work put up your hands." Every hand went up as we opted to work. We were taken into wooded country full of tethered elephants and horses and our task was to look after them by preparing their feed and clearing up their dung, three times a day. We worked till 2200 hours each day.

We lived in long huts and were woken up every morning at 0200 hours with the command "Shaw-shaw-shaw" and made to prepare the fodder until 0600 hours, when the Japanese commanded us to feed them, "Mis-mis-mis". After that it was our turn to feed with some rice and gruel. We were not allowed to use our hands but had to use small sticks. If we ate with our hands they hit us in the face.

At last the weather became colder, much colder. Among the 700 were some Burmese and one morning, before 0200 hours, one older Burman had collected kindling and had lit a fire. When the Japanese came in the Burman and I were warming ourselves. He asked where the others were. I told him I didn't know but they were probably asleep somewhere. The Japanese sentry started hitting me in the face. The old Burman ran away. I was so angry I picked up a brick and, whether I died or not, made to throw it at the Japanese, who ran away. The Japanese told the other Gurkhas what I had done and that they were to watch me being shot when it was light.

We went out as normal to feed the animals and at our meal time I was called over by that Japanese to have a meal with him, but I was so angry I did not go. A 3/2 GR Subedar and Jemadar had also been captured and the Japanese said that these two would be told of our faults the next day and they would look after us. We all thought we'd be killed. "Why be afraid?" I asked the others. "Only I am to be killed as I am the only one who has done wrong. You have done nothing wrong," I told them.

Next day at noon the Subedar and Jemadar came. The Japanese fell in on one side and the Gurkhas on the other side. The case was discussed and the Japanese Officer ordered the sentry and the person who had done wrong to step forward. I stepped in front and pointed out the sentry who had hit me and called him forward. I explained what had happened in Hindi as the Japanese Officer spoke Hindi. "He always hits everybody every morning and many cheeks are swollen from continual hitting. My cheeks are very swollen. As I have done no wrong and have worked well, when he hit me I picked up the brick." I explained what I had said at the time. The sentry said I had driven the other prisoners outside. My answer was I was a coolie so were the others, so how could I send them away? The Japanese Officer told the sentry that we Gurkhas were there to help,

not to be hit. "Why have you hit them so much? Everybody's cheeks are swollen." The Japanese Officer then struck the sentry very hard and the other Japanese took him away.

A new sentry came in his place. The Japanese Officer told the other Japanese that, "The Gurkhas' mothers and fathers are not here and there are no mail facilities and so no one knows they are here. They are prisoners and have to be here. Our fathers and mothers are not here either but we are here to fight. Will we die or stay alive? These men will have to work as long as they're here. If they are sick they must be treated." Some time after that we were moved and eventually reached Mandalay where we saw the Irrawaddy, vast as the sea. The bridge had been smashed and we spent the night crossing in boats, some way downstream.

Tilbahadur goes on to say:

Next morning we moved onto high ground in very thick jungle. We rested up at a small stream. That day we sent Damarbahadur Chhetri to forage for some raksi (an alcoholic drink) from a village. I could not move because an aeroplane flew very low, "gun-nu-nu-nu-nu". I said out loud how lovely it would be if we could fly away like that. The Japanese Commander heard me and that evening came over and told me never to move when any aeroplane flew over. "What would we do if you had a wound in your feet?" he asked.

Damarbahadur came back with raksi and a chicken which we killed, cooked and ate. Next day at noon three aeroplanes came over and dropped bombs and fired on us, "gut-tu-tu-tu-tu", one way and over again, "pa-ra-ra-ra-ra". We did not know if they were British or Japanese aeroplanes. Some Gurkhas and many Japanese were killed and wounded. I was distraught; how to escape? I found a ditch and lay in it. I was joined by a "Jemadar" Japanese officer who kept on saying in Hindi, how bad the English were.

After the aircraft flew away Damarbahadur and I decided to escape. Blood was everywhere. We took one blanket each from dead Japanese. It was late afternoon and there were still one or two Japanese around the place so we stayed where we were. Another aeroplane came over and this time we heard the Japanese cry out that it was a British one. It was then we slipped away. We moved all night through thick undergrowth. We heard some Japanese shout "Hangku!" — "Halt!" We evaded them, moving along a stream, sometimes in deep water, sometimes in shallow.

At dawn we reached high ground. We found some water so we decided to rest and have a wash. No food, no weapons, no matches, only one bottle of raksi. We agreed to drink only half and leave the other half for later. We saw that our blankets were covered in blood so we threw them away. We had on one thin shirt, one pair of pants and a pair of boots, all Japanese — nothing else. And of course it rained all day.

Eventually, seven days later with only water to drink during that time, we met two Gurkhas, Subedar Narbahadur Gurung and a Rifleman. We were now four. The other two had seen a jungle clearing and some villagers so we decided to go there and ask for fire so we could cook bamboo shoots. Narbahadur and I were to go, but if either of us were wounded, the other would stay with him. On our way there we met some British soldiers who, on seeing us, took aim. We halted. They halted. They talked. We didn't understand what they said and they did not understand us.

A bearded Punjabi soldier was fetched as interpreter. "How many of you are there?" he asked. "Four of us." "Where are they?" "Up the hill." "Call them down." We called them down and we were told to sit. We sat down. We were asked all details, home village, date of enlistment, place of enlistment, number, rank and name, where we went after recruiting. "Dehra Dun," I said. "And after that?" "Fort Sandeman." "Then where?" "Loralei." And all the details of where we had been, the names of all our officers, British and Gurkha, what weapons we carried and much more.

Eventually we told them we were running away from the Japanese. "Who was your OC?" "Major Calpat." "Oh? Now he's a general. What is your Brigade number?" "I do not know. I can tell you everything except that. I have heard it is 77." "If you don't know your Brigade number, you can't be a genuine Gurkha soldier." "I don't know for sure. No one told us but I heard one soldier say it was 77."

After that we were told to spend the night there. "Our HQ is eight miles away and another four miles on is the Gurkha HQ. If the Japanese don't open fire between 1800 hours and 0600 hours, I'll take you there tomorrow. If there is any Japanese attack we will kill you." "Fine. If we are killed by a British bullet rather than a Japanese bullet, we'll go to heaven." We were happy. A British soldier gave us biscuits and tea. That evening three of us were bound together by our hands. One had his hands so tightly bound he started weeping. I told him to keep quiet as our captors would not understand as we had no common language. We other two managed to loosen our bonds sufficiently to relieve the pressure on the third. However, before our captors came to us in the morning we had tightened the knots again.

The Punjabi came in the morning and told us to follow him. We met the Brigade HQ Officers who were sitting down as though waiting for us and asked where we had come from. We were asked many questions which we answered. One officer told his orderly we were very hungry so quickly make some tea and bring biscuits. As we ate and drank we gave them full details of our experiences. Two men were detailed to take us to 'Calpat' sahib and some other Gurkhas. When we got there we were asked the same questions. "Good. You've escaped. I don't want to see you in Japanese clothes," he said. We were given new clothes and told to burn the old Japanese uniforms.

The Subedar Major ordered the cookhouse staff to feed us three times a day because we were so weak. Next day we were fully debriefed and we told all we knew, in detail, just as we had told the Punjabi, from the beginning. At the end the officer said that he'd tell the general about us and we would meet him next day. "You will get a bahaduri (bravery award) even if you don't get a pension."

They again asked me my name, number and rank. The paperwork went everywhere, including Gorakhpur. Later I learnt that my bahaduri had been given to someone else. I believe that the paperwork had the name altered before it was given to the General. The Gurkha Officer who wrote down the details changed the name to that of his cousin. In the evening the General came. We had met before and he called me by my name. "Do you want to continue fighting or go home?" he asked in khaskura. "We want to fight. Please give us weapons."

The officer said no, because the Japanese had treated us so badly and we were too weak for military operations. The British Officer said that we still had to capture Myitkyina so these men could stay looking after casualties in Brigade HQ. We heard the attack on Myitkyina, bombs bursting, "gu-du-du-gu-du-du", and machine guns firing, "da-ra-ra-da-ra-ra". There was heavy fighting. There were British troops, Hindu troops, Muslim troops, Gurkha troops, Chinese troops and Habsi troops, but the Japanese were in good prepared positions. The battle lasted a month. It seemed as though both sides suffered dreadful casualties but eventually we took the town. We were taken to the airfield and were flown to Pandu Ghat railway station.

There we met Subedar Siribhakta who had been captured and escaped. We went to Gauhati where again we were asked many questions. I was asked what I had been doing and I told them I had worked with mules. I was detailed to go to Calcutta next day. When Siribhakta was asked what he had been doing he said "This and that". He was rebuked and the officer ordered him to be locked up. I learnt that Siribhakta had, in fact, helped the Japanese and that a previous group of Gurkha POW's had reported against him.

NB. Column 3's Administration Officer, Lieutenant Alec Gibson has told me that many of the Gurkhas from his column had pretended to help the enemy whilst POW's, but had in fact tried their very best to mis-lead the Japanese interrogators with false information. He also explained that the ordinary Gurkhas had very little knowledge or understanding of the operation or its purpose and would not be able to tell the Japanese anything of importance.

Tilbahadur's testimony concludes at this point.

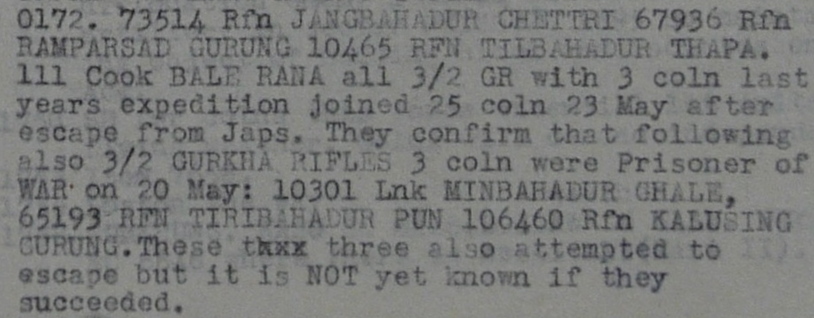

During one of my research visits to the National Archives I came across the diary extract shown below. It is taken from the 1944 War Diary of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, commanded by the now Brigadier Calvert. It refers to the discovery and rescue of a group of Gurka POW's during the Brigade's operational movements in 1944. It includes the name of a Tilbahadur Thapa, whether it is our Tilbahadur I cannot be sure, but the odds must be strongly in favour.

Next morning we moved onto high ground in very thick jungle. We rested up at a small stream. That day we sent Damarbahadur Chhetri to forage for some raksi (an alcoholic drink) from a village. I could not move because an aeroplane flew very low, "gun-nu-nu-nu-nu". I said out loud how lovely it would be if we could fly away like that. The Japanese Commander heard me and that evening came over and told me never to move when any aeroplane flew over. "What would we do if you had a wound in your feet?" he asked.

Damarbahadur came back with raksi and a chicken which we killed, cooked and ate. Next day at noon three aeroplanes came over and dropped bombs and fired on us, "gut-tu-tu-tu-tu", one way and over again, "pa-ra-ra-ra-ra". We did not know if they were British or Japanese aeroplanes. Some Gurkhas and many Japanese were killed and wounded. I was distraught; how to escape? I found a ditch and lay in it. I was joined by a "Jemadar" Japanese officer who kept on saying in Hindi, how bad the English were.

After the aircraft flew away Damarbahadur and I decided to escape. Blood was everywhere. We took one blanket each from dead Japanese. It was late afternoon and there were still one or two Japanese around the place so we stayed where we were. Another aeroplane came over and this time we heard the Japanese cry out that it was a British one. It was then we slipped away. We moved all night through thick undergrowth. We heard some Japanese shout "Hangku!" — "Halt!" We evaded them, moving along a stream, sometimes in deep water, sometimes in shallow.

At dawn we reached high ground. We found some water so we decided to rest and have a wash. No food, no weapons, no matches, only one bottle of raksi. We agreed to drink only half and leave the other half for later. We saw that our blankets were covered in blood so we threw them away. We had on one thin shirt, one pair of pants and a pair of boots, all Japanese — nothing else. And of course it rained all day.

Eventually, seven days later with only water to drink during that time, we met two Gurkhas, Subedar Narbahadur Gurung and a Rifleman. We were now four. The other two had seen a jungle clearing and some villagers so we decided to go there and ask for fire so we could cook bamboo shoots. Narbahadur and I were to go, but if either of us were wounded, the other would stay with him. On our way there we met some British soldiers who, on seeing us, took aim. We halted. They halted. They talked. We didn't understand what they said and they did not understand us.

A bearded Punjabi soldier was fetched as interpreter. "How many of you are there?" he asked. "Four of us." "Where are they?" "Up the hill." "Call them down." We called them down and we were told to sit. We sat down. We were asked all details, home village, date of enlistment, place of enlistment, number, rank and name, where we went after recruiting. "Dehra Dun," I said. "And after that?" "Fort Sandeman." "Then where?" "Loralei." And all the details of where we had been, the names of all our officers, British and Gurkha, what weapons we carried and much more.

Eventually we told them we were running away from the Japanese. "Who was your OC?" "Major Calpat." "Oh? Now he's a general. What is your Brigade number?" "I do not know. I can tell you everything except that. I have heard it is 77." "If you don't know your Brigade number, you can't be a genuine Gurkha soldier." "I don't know for sure. No one told us but I heard one soldier say it was 77."

After that we were told to spend the night there. "Our HQ is eight miles away and another four miles on is the Gurkha HQ. If the Japanese don't open fire between 1800 hours and 0600 hours, I'll take you there tomorrow. If there is any Japanese attack we will kill you." "Fine. If we are killed by a British bullet rather than a Japanese bullet, we'll go to heaven." We were happy. A British soldier gave us biscuits and tea. That evening three of us were bound together by our hands. One had his hands so tightly bound he started weeping. I told him to keep quiet as our captors would not understand as we had no common language. We other two managed to loosen our bonds sufficiently to relieve the pressure on the third. However, before our captors came to us in the morning we had tightened the knots again.

The Punjabi came in the morning and told us to follow him. We met the Brigade HQ Officers who were sitting down as though waiting for us and asked where we had come from. We were asked many questions which we answered. One officer told his orderly we were very hungry so quickly make some tea and bring biscuits. As we ate and drank we gave them full details of our experiences. Two men were detailed to take us to 'Calpat' sahib and some other Gurkhas. When we got there we were asked the same questions. "Good. You've escaped. I don't want to see you in Japanese clothes," he said. We were given new clothes and told to burn the old Japanese uniforms.

The Subedar Major ordered the cookhouse staff to feed us three times a day because we were so weak. Next day we were fully debriefed and we told all we knew, in detail, just as we had told the Punjabi, from the beginning. At the end the officer said that he'd tell the general about us and we would meet him next day. "You will get a bahaduri (bravery award) even if you don't get a pension."

They again asked me my name, number and rank. The paperwork went everywhere, including Gorakhpur. Later I learnt that my bahaduri had been given to someone else. I believe that the paperwork had the name altered before it was given to the General. The Gurkha Officer who wrote down the details changed the name to that of his cousin. In the evening the General came. We had met before and he called me by my name. "Do you want to continue fighting or go home?" he asked in khaskura. "We want to fight. Please give us weapons."

The officer said no, because the Japanese had treated us so badly and we were too weak for military operations. The British Officer said that we still had to capture Myitkyina so these men could stay looking after casualties in Brigade HQ. We heard the attack on Myitkyina, bombs bursting, "gu-du-du-gu-du-du", and machine guns firing, "da-ra-ra-da-ra-ra". There was heavy fighting. There were British troops, Hindu troops, Muslim troops, Gurkha troops, Chinese troops and Habsi troops, but the Japanese were in good prepared positions. The battle lasted a month. It seemed as though both sides suffered dreadful casualties but eventually we took the town. We were taken to the airfield and were flown to Pandu Ghat railway station.

There we met Subedar Siribhakta who had been captured and escaped. We went to Gauhati where again we were asked many questions. I was asked what I had been doing and I told them I had worked with mules. I was detailed to go to Calcutta next day. When Siribhakta was asked what he had been doing he said "This and that". He was rebuked and the officer ordered him to be locked up. I learnt that Siribhakta had, in fact, helped the Japanese and that a previous group of Gurkha POW's had reported against him.

NB. Column 3's Administration Officer, Lieutenant Alec Gibson has told me that many of the Gurkhas from his column had pretended to help the enemy whilst POW's, but had in fact tried their very best to mis-lead the Japanese interrogators with false information. He also explained that the ordinary Gurkhas had very little knowledge or understanding of the operation or its purpose and would not be able to tell the Japanese anything of importance.

Tilbahadur's testimony concludes at this point.

During one of my research visits to the National Archives I came across the diary extract shown below. It is taken from the 1944 War Diary of the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade, commanded by the now Brigadier Calvert. It refers to the discovery and rescue of a group of Gurka POW's during the Brigade's operational movements in 1944. It includes the name of a Tilbahadur Thapa, whether it is our Tilbahadur I cannot be sure, but the odds must be strongly in favour.

The escape and evasion of Tilbahadur Thapa is also recounted on the following website pages:

http://www.memorial-gates-london.org.uk/history/ww2/participants/indian-subcontinent/tilbahadur-thapa.html

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80025579

My special thanks must go to former Gurkha Officer, John P. Cross, for allowing me to reproduce the story of Rifleman Tilbahadur Thapa from his book 'Gurkhas at War'.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and JP Cross 2013.

http://www.memorial-gates-london.org.uk/history/ww2/participants/indian-subcontinent/tilbahadur-thapa.html

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80025579

My special thanks must go to former Gurkha Officer, John P. Cross, for allowing me to reproduce the story of Rifleman Tilbahadur Thapa from his book 'Gurkhas at War'.

Copyright © Steve Fogden and JP Cross 2013.