Robert Valentine Hyner

Pte. Robert V. Hyner in India in 1942.

Pte. 5625272 Robert V. Hyner was part of the detachment of men from the Devonshire Regiment that joined initial Chindit training at the Saugor Camp in late September 1942. Originally from London, the tall cockney recruit had been sent to the Exeter Infantry Training Centre and had enjoyed his time there, although often his sharp-witted sense of humour had got him in to trouble.

It is possible that he travelled over to India aboard the same convoy vessel as my grandfather, but this cannot be verified at this time.

Once at Saugor, Robert was placed into Column 7, under the overall command of Major Kenneth Gilkes. Within this unit he was trained as a Bren-gunner (number one position) in Platoon 14, commanded by Captain William Jelliss, although throughout his memoir Robert mistakenly calls this officer Captain Jealous.

Early on during the operation in Burma, Hyner's Bren-gun team was used as covering protection at most of, if not all the river crossings undertaken by the Chindits. He remembered the first full supply drop that the column received not long after crossing the Chindwin River in February 1943, where, once again he was involved in the rear guard protection on the tracks leading into the drop-zone area.

Burmese scouts had then reported back to the column that there was a Japanese garrison not far from the unit's current position. The men were briefed about the attack that was to take place the following day. Robert remembers his feelings that morning:

"Dawn soon came and the attack began, the muleteers were left behind with most of our equipment, which I was glad to be relieved of. We walked silently on to the village, expecting to be fired upon at any moment, only to find that the 300 or Japs had vanished. I had mixed feelings, both disappointment and relief, as this would have been my first experience of coming under enemy-fire."

At this point in the operation all the columns in Northern Section spread out, leaving Column 7 to scout ahead of Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters. This was to be the column's main role during the operation, acting firstly as protection for the Brigadier, then sometimes as a decoy for Columns 3 and 5, as they moved off to their pre-planned locations along the railway. The men soon got used to this continuous marching, but began to wonder if they would ever finally meet the Japanese. Hyner recalls: "After 4 days in Burma we still hadn't seen a single Jap and wondered where they were."

They would not have to wait too long to find out.

"We still had not seen the enemy. Sometimes it was just like a summer's day in the country. Corporal Woodman was sitting on the right-handside of me on a tree trunk, the Sergeant was leaning against a tree to my left and had been suffering from a touch of malaria. Behind us was a dried up river bed, with a six foot bank which offered us good protection. I was lying flat on the deck leaning on my elbows with my finger on the trigger of my Bren. By this time a foraging party had entered the village and had seen another group of soldiers at the far end of the track. Thinking they were British they waved at them, and so began our first battle, the men to whom they had waved were Japs.

Sergeant Major Burns was twelve yards behind me, observing the area with a pair of binoculars. A Japanese machine gun opened up and the Sergeant dived for cover, Woodman also took cover behind his tree. I got even closer to the ground, grazing my nose in the process. My Bren gun was shot out of my hands with the bullets ricocheting off my gun and killing a chap called Ginger who was directly behind me. I needed to get back to the main position to collect a new barrel for my weapon, so I told the Sergeant of my intention and crawled back to the nula (dried up river bed) where the mules and equipment were stationed. At that moment Captain Hastings ordered Woody (Corporal Woodman) and I to return to our original position and to shoot at anything coming across the open paddy field."

Woodman and Hyner covered the column's retreat from this first engagement with the Japanese, waiting for over three hours before being able to re-join the main body and march away from the area. Column 7 had ordered another supply drop and with this came a pair of Hyner's false teeth, something he had been waiting for since the unit first entered Burma. The column marched on for several days moving up into the mountain range and along a secret track known only to the local Burmese guides. The men began to become weary with the seemingly endless hours of marching and noticed how tattered their uniforms were now looking.

Finally, they reached the Mandalay Road, where they settled into a concealed jungle camp and waited patiently in hope of ambushing any Japanese motorised convoys or patrols that might pass by. By this time water was becoming more difficult to find and the men were constantly on edge.

It is possible that he travelled over to India aboard the same convoy vessel as my grandfather, but this cannot be verified at this time.

Once at Saugor, Robert was placed into Column 7, under the overall command of Major Kenneth Gilkes. Within this unit he was trained as a Bren-gunner (number one position) in Platoon 14, commanded by Captain William Jelliss, although throughout his memoir Robert mistakenly calls this officer Captain Jealous.

Early on during the operation in Burma, Hyner's Bren-gun team was used as covering protection at most of, if not all the river crossings undertaken by the Chindits. He remembered the first full supply drop that the column received not long after crossing the Chindwin River in February 1943, where, once again he was involved in the rear guard protection on the tracks leading into the drop-zone area.

Burmese scouts had then reported back to the column that there was a Japanese garrison not far from the unit's current position. The men were briefed about the attack that was to take place the following day. Robert remembers his feelings that morning:

"Dawn soon came and the attack began, the muleteers were left behind with most of our equipment, which I was glad to be relieved of. We walked silently on to the village, expecting to be fired upon at any moment, only to find that the 300 or Japs had vanished. I had mixed feelings, both disappointment and relief, as this would have been my first experience of coming under enemy-fire."

At this point in the operation all the columns in Northern Section spread out, leaving Column 7 to scout ahead of Wingate's own Brigade Head Quarters. This was to be the column's main role during the operation, acting firstly as protection for the Brigadier, then sometimes as a decoy for Columns 3 and 5, as they moved off to their pre-planned locations along the railway. The men soon got used to this continuous marching, but began to wonder if they would ever finally meet the Japanese. Hyner recalls: "After 4 days in Burma we still hadn't seen a single Jap and wondered where they were."

They would not have to wait too long to find out.

"We still had not seen the enemy. Sometimes it was just like a summer's day in the country. Corporal Woodman was sitting on the right-handside of me on a tree trunk, the Sergeant was leaning against a tree to my left and had been suffering from a touch of malaria. Behind us was a dried up river bed, with a six foot bank which offered us good protection. I was lying flat on the deck leaning on my elbows with my finger on the trigger of my Bren. By this time a foraging party had entered the village and had seen another group of soldiers at the far end of the track. Thinking they were British they waved at them, and so began our first battle, the men to whom they had waved were Japs.

Sergeant Major Burns was twelve yards behind me, observing the area with a pair of binoculars. A Japanese machine gun opened up and the Sergeant dived for cover, Woodman also took cover behind his tree. I got even closer to the ground, grazing my nose in the process. My Bren gun was shot out of my hands with the bullets ricocheting off my gun and killing a chap called Ginger who was directly behind me. I needed to get back to the main position to collect a new barrel for my weapon, so I told the Sergeant of my intention and crawled back to the nula (dried up river bed) where the mules and equipment were stationed. At that moment Captain Hastings ordered Woody (Corporal Woodman) and I to return to our original position and to shoot at anything coming across the open paddy field."

Woodman and Hyner covered the column's retreat from this first engagement with the Japanese, waiting for over three hours before being able to re-join the main body and march away from the area. Column 7 had ordered another supply drop and with this came a pair of Hyner's false teeth, something he had been waiting for since the unit first entered Burma. The column marched on for several days moving up into the mountain range and along a secret track known only to the local Burmese guides. The men began to become weary with the seemingly endless hours of marching and noticed how tattered their uniforms were now looking.

Finally, they reached the Mandalay Road, where they settled into a concealed jungle camp and waited patiently in hope of ambushing any Japanese motorised convoys or patrols that might pass by. By this time water was becoming more difficult to find and the men were constantly on edge.

Robert Hyner remembers:

"Just at this moment news came through that the men who had been forming a road block had gone missing. Firing had been heard in the area, but no one was sure quite from which direction, due to the echoing noise of the jungle. The 14th Platoon was ordered out to search, but to keep well clear of the road. We wandered around in the afternoon heat searching the area where the men had last been reported. Nerves were on edge over the disappearance of the men and it was eventually decided to halt and to brew up tea and have something to eat.

Suddenly a muffled voice from one of the sentries seemed to shout "get out of here, quick." Momentary panic broke out. Men were rushing here and there and one chap had fallen down and was being trampled by his comrades as they tried to escape, myself included. I swore that from that day on I would always think before I moved, this I managed to do. The panic was understandable as one platoon was already missing and it was not found that day. I learned later that the sentry had challenged a Burmese civilian and this had somehow started the panic off. When we got back to the main group we reported no sign of the missing platoon and settled down for a rest."

Around this period Columns 3 and 5 where completing their explosive handy-work at Nankan and Bonchaung. Column 7 could hear the explosions in the distance, but all was relatively quiet for them. Finally the orders were given for the column to move directly to the banks of the Irrawaddy River, by now the men were becoming more and more weak with hunger, in fact some of the mules were killed at this point and used as meat to supplement the meagre rations. Column 7 and Wingate crossed the Irrawaddy in small country boats and canoes and headed further east into occupied territory, the men discussed the decision to cross the river amongst themselves, with many failing to see the point of this latest move.

By late March the column had arrived at a place called Baw. A large supply drop was arranged for this location and one by one other Chindit Columns began to arrive. It was at this time that Wingate received orders from India Command to return his men back to the safety of Allied held territory. Robert Hyner remembers what the Brigadier said to the men that day: "I want you all to get back safely to India. You have my orders that you can go back with a full column, a platoon or with just one mate, just as long as you get out."

Baw was to be the last full supply drop for the Chindits as a large group. Daylight broke that morning to the sound of machine-gun fire. Platoon 14 were once again used to repulse the Japanese attackers and to cover the supply drop zone on the western perimeter. There followed a very confused engagement with the enemy in a dense teak forest. Small groups of soldiers fought each other, sometimes in close quarter hand to hand combat, many casualties were taken on both sides. The supply drop continued all through the morning with Hyner's platoon defending their position against continuous enemy interference. Robert Hyner witnessed a Gurkha Officer lose his life at this engagement, from the time and description of the action I believe this could well have been Lieutenant Dennis Russell Chambers of the 3rd Gurkha Rifles.

Pte. Hyner also recalls:

"Later on in the afternoon we were ordered to rejoin the full platoon. In that supply dropping I had received a letter, informing me that my grandfather had died. This must have been on my mind while I was walking back towards the 14th Platoon, who were laid out on the floor in single file position, engaging the enemy. As I was getting nearer to them something seemed to push me in the centre of my back and I fell over. I did not trip and there was no one within touching distance behind me. At that precise moment a machine gun opened up, hitting the trees where I would have been standing. This, I feel sure, was my grandfather looking after me and that it was him that pushed me to the ground. I then recovered, got up and walked on towards the platoon."

With the rations collected the supply drop was closed and the Chindit Columns retreated to a dry chaung river bed and rested a while. It was here that Hyner saw Lieutenant Petersen, the only Danish soldier on the operation, being treated for a gun-shot wound to the head. Remarkably, although seriously injured, Petersen would survive the long trek back to safety and continue his service in Special Forces for the rest of the war.

After resting for a few hours and using the moonlight available that night, the group moved back towards the Irrawaddy River. The men of Platoon 14 had the important job of escorting their Brigadier, who was now travelling on foot having lost his horse to Japanese mortar fire the previous day.

"I saw the Brigadier sitting on a tree trunk. He had a beard just like us and his army tunic was also torn. He was drinking water and I asked him, "where did you get that water from, cock?" momentarily forgetting who I was talking to. He replied,"over their, son," pointing to some muddy hoove marks in the field. I half filled my water bottle and put my dirty handkerchief over the top of the bottle to strain it and then drank it, I remember the taste at the time was not very nice."

As the Chindits approached the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy, Hyner's platoon were stationed as rear guard, this time being commanded by Lieutenant Oakes. The platoon remained behind to cover the advance to the river and to deal with any Japanese following up from the previous day's battle at Baw. In the confusion and disorganisation that day, Platoon 14 were forgotten about, and were left in their rear guard position without orders to re-join the main group at the river side. The platoon decided to move off anyway and follow the trail which they hoped might return them to the rest of their Chindit comrades. Eventually they met up with Major Pickering of the King's who directed them into safe harbour once more.

"Just at this moment news came through that the men who had been forming a road block had gone missing. Firing had been heard in the area, but no one was sure quite from which direction, due to the echoing noise of the jungle. The 14th Platoon was ordered out to search, but to keep well clear of the road. We wandered around in the afternoon heat searching the area where the men had last been reported. Nerves were on edge over the disappearance of the men and it was eventually decided to halt and to brew up tea and have something to eat.

Suddenly a muffled voice from one of the sentries seemed to shout "get out of here, quick." Momentary panic broke out. Men were rushing here and there and one chap had fallen down and was being trampled by his comrades as they tried to escape, myself included. I swore that from that day on I would always think before I moved, this I managed to do. The panic was understandable as one platoon was already missing and it was not found that day. I learned later that the sentry had challenged a Burmese civilian and this had somehow started the panic off. When we got back to the main group we reported no sign of the missing platoon and settled down for a rest."

Around this period Columns 3 and 5 where completing their explosive handy-work at Nankan and Bonchaung. Column 7 could hear the explosions in the distance, but all was relatively quiet for them. Finally the orders were given for the column to move directly to the banks of the Irrawaddy River, by now the men were becoming more and more weak with hunger, in fact some of the mules were killed at this point and used as meat to supplement the meagre rations. Column 7 and Wingate crossed the Irrawaddy in small country boats and canoes and headed further east into occupied territory, the men discussed the decision to cross the river amongst themselves, with many failing to see the point of this latest move.

By late March the column had arrived at a place called Baw. A large supply drop was arranged for this location and one by one other Chindit Columns began to arrive. It was at this time that Wingate received orders from India Command to return his men back to the safety of Allied held territory. Robert Hyner remembers what the Brigadier said to the men that day: "I want you all to get back safely to India. You have my orders that you can go back with a full column, a platoon or with just one mate, just as long as you get out."

Baw was to be the last full supply drop for the Chindits as a large group. Daylight broke that morning to the sound of machine-gun fire. Platoon 14 were once again used to repulse the Japanese attackers and to cover the supply drop zone on the western perimeter. There followed a very confused engagement with the enemy in a dense teak forest. Small groups of soldiers fought each other, sometimes in close quarter hand to hand combat, many casualties were taken on both sides. The supply drop continued all through the morning with Hyner's platoon defending their position against continuous enemy interference. Robert Hyner witnessed a Gurkha Officer lose his life at this engagement, from the time and description of the action I believe this could well have been Lieutenant Dennis Russell Chambers of the 3rd Gurkha Rifles.

Pte. Hyner also recalls:

"Later on in the afternoon we were ordered to rejoin the full platoon. In that supply dropping I had received a letter, informing me that my grandfather had died. This must have been on my mind while I was walking back towards the 14th Platoon, who were laid out on the floor in single file position, engaging the enemy. As I was getting nearer to them something seemed to push me in the centre of my back and I fell over. I did not trip and there was no one within touching distance behind me. At that precise moment a machine gun opened up, hitting the trees where I would have been standing. This, I feel sure, was my grandfather looking after me and that it was him that pushed me to the ground. I then recovered, got up and walked on towards the platoon."

With the rations collected the supply drop was closed and the Chindit Columns retreated to a dry chaung river bed and rested a while. It was here that Hyner saw Lieutenant Petersen, the only Danish soldier on the operation, being treated for a gun-shot wound to the head. Remarkably, although seriously injured, Petersen would survive the long trek back to safety and continue his service in Special Forces for the rest of the war.

After resting for a few hours and using the moonlight available that night, the group moved back towards the Irrawaddy River. The men of Platoon 14 had the important job of escorting their Brigadier, who was now travelling on foot having lost his horse to Japanese mortar fire the previous day.

"I saw the Brigadier sitting on a tree trunk. He had a beard just like us and his army tunic was also torn. He was drinking water and I asked him, "where did you get that water from, cock?" momentarily forgetting who I was talking to. He replied,"over their, son," pointing to some muddy hoove marks in the field. I half filled my water bottle and put my dirty handkerchief over the top of the bottle to strain it and then drank it, I remember the taste at the time was not very nice."

As the Chindits approached the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy, Hyner's platoon were stationed as rear guard, this time being commanded by Lieutenant Oakes. The platoon remained behind to cover the advance to the river and to deal with any Japanese following up from the previous day's battle at Baw. In the confusion and disorganisation that day, Platoon 14 were forgotten about, and were left in their rear guard position without orders to re-join the main group at the river side. The platoon decided to move off anyway and follow the trail which they hoped might return them to the rest of their Chindit comrades. Eventually they met up with Major Pickering of the King's who directed them into safe harbour once more.

Wingate decided that the columns present (Columns 7, 8 and Wingate's HQ) should cross in strength and at once. Platoons 14 and 15 were chosen to lead the crossing and to form a secure bridgehead on the western bank. Robert Hyner recalls:

"Going back and forth in those Burmese canoes, well, it was just like being at Southend on a beautiful summer's day."

This illusion was quickly scuppered when these lead boats came under enemy machine gun and mortar fire. Some men were sadly killed at this time including Captain Hastings and Lance Sergeant William Royle. Hyner's boat had drifted around a bend in the river giving the men aboard some precious cover and the time to scramble up onto the river bank and quickly disappear into the nearby scrub jungle. After attempting to engage the Japanese positions for a time, Captain Jelliss, realising that no more Chindits were crossing the river, decided to move his party of men away from the river and westward towards India.

Hyner: "Unfortunately, we now knew that we were on our own, we had no food or ammunition and we had no wireless communication with anybody".

Another soldier, this time from Platoon 15 of Column 7 also remembers that fateful river crossing. Pte. Charles Aves was in another of the lead boats:

"As quietly as possible, we made our way to the small boats at the bank of the river, where a Burmese boatman had been paid to ferry us across. I think I was in the second or third boat. We proceeded across the river and it seemed like ages getting across. I suppose there were eight or 10 of us in each boat. Just as we and a couple of other boats reached the bank, the Japs opened up with mortar and automatic machine-gun fire from a point some few hundred yards north of our landing area. We couldn't see them, for they were well concealed in a jungle copse. We scrambled ashore. I shall never forget my Lieutenant; sitting in that boat eating cheese from a tin with a penknife, seemingly quite unconcerned about the firing which was directed onto our boats as we tried to get over and also against the troops on the other side."

"Going back and forth in those Burmese canoes, well, it was just like being at Southend on a beautiful summer's day."

This illusion was quickly scuppered when these lead boats came under enemy machine gun and mortar fire. Some men were sadly killed at this time including Captain Hastings and Lance Sergeant William Royle. Hyner's boat had drifted around a bend in the river giving the men aboard some precious cover and the time to scramble up onto the river bank and quickly disappear into the nearby scrub jungle. After attempting to engage the Japanese positions for a time, Captain Jelliss, realising that no more Chindits were crossing the river, decided to move his party of men away from the river and westward towards India.

Hyner: "Unfortunately, we now knew that we were on our own, we had no food or ammunition and we had no wireless communication with anybody".

Another soldier, this time from Platoon 15 of Column 7 also remembers that fateful river crossing. Pte. Charles Aves was in another of the lead boats:

"As quietly as possible, we made our way to the small boats at the bank of the river, where a Burmese boatman had been paid to ferry us across. I think I was in the second or third boat. We proceeded across the river and it seemed like ages getting across. I suppose there were eight or 10 of us in each boat. Just as we and a couple of other boats reached the bank, the Japs opened up with mortar and automatic machine-gun fire from a point some few hundred yards north of our landing area. We couldn't see them, for they were well concealed in a jungle copse. We scrambled ashore. I shall never forget my Lieutenant; sitting in that boat eating cheese from a tin with a penknife, seemingly quite unconcerned about the firing which was directed onto our boats as we tried to get over and also against the troops on the other side."

After the chaotic river crossing the two platoons, now somewhat inter-mixed moved away from the Irrawaddy and into the dense bamboo jungle, which soon engulfed the small Chindit force. The following day the group came across a Burmese village and with due caution met with the Headman and organised some food. Rice would now become the men's staple diet as they pushed on westward towards home.

A day later whilst resting in a jungle glade, the group was caught out by a Japanese patrol. The men had paid the penalty for not placing sentries around the perimeter and a mad panic saw the Chindits racing in all directions to escape the oncoming Japanese. Robert Hyner became separated from his best pal, Bill, and even more disastrously many men left behind their precious packs and rifles. This was the last time Captain Jelliss led the unit and Hyner's group was now down to about 25 men, with Lieutenant Oakes in command.

All discipline had been lost, weapons abandoned and officers struggled with the unfamiliar conditions and had little control over the men. The weary Chindits continued on, marching mostly by moonlight and in the early morning and resting up during the heat of the day to conserve energy. Several men decided to leave the main group and try and make for India on their own. One such soldier was Sgt. J. Jarvis formerly of the KOYLI (Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry), he had been attached to the Commandos on Operation Longcloth and was a seasoned campaigner. Jarvis was never seen again.

Water had now become a serious issue for the dwindling group of Column 7 Chindits. Hyner recalled:

"By now we were making our way along the side of the mountain range, marching by the only compass we still had and keeping our course due west. Our stomachs had forgotten about food; our problem was now water, or the lack of it. One soldier, Private Randall, was so thirsty he passed his own urine into his mug and then drank it. Within seconds of him doing so someone shouted out "water". A finger wide trickle was coming down the mountain side. We rested there a while and took our first good drink for several days, then we filled our water bottles and continued our journey to the top of the mountain."

Around this time an unfortunate accident befell one of the men. Nearly all of the men had discarded or lost their heavy Chindit packs, all that is except for Pte. Gordon David Rackham. Sadly this was to be his undoing. Robert Hyner explains:

"After a few more days we saw in the valley below a river which we decided to make for, still as always, heading west. One soldier Pte. Rackham had not discarded the Everest frame for his pack and he got it caught in some trees and fell over the side of the mountain. We all went down to see what we could do for him. He was so badly injured the officer in charge asked for a volunteer to shoot him, as he, the officer, couldn't possibly do it; but no one volunteered. As he was unable to walk under his own steam Pte. Rackham was left with some water and was made as comfortable as possible. Our intentions were to get help back to him from the next village, which we could actually see from where we now stood."

Sadly for Rackham the men were never able to send back help, as the next village took much longer to reach than first anticipated and was occupied by a Japanese patrol. For Pte. Rackham's CWGC details, please click on the link below:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2522158/RACKHAM,%20GORDON%20DAVID

On the 24th November 1943, the commander of No. 7 Column, Major Kenneth Gilkes gave the following witness statement in relation to Pte. Rackham and his eventual fate on Operation Longcloth:

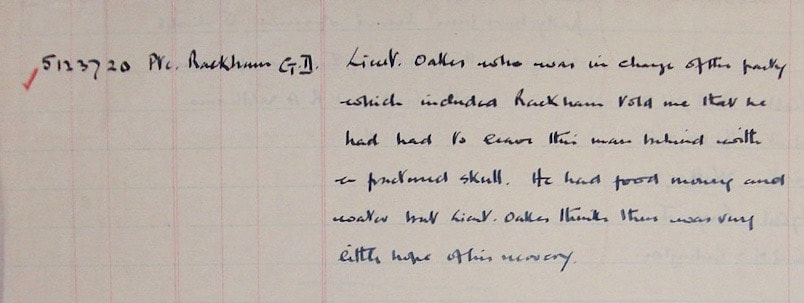

In regards Pte. 5123720 Pte. G. D. Rackham:

Lieut. Oakes, who was in charge of the party which included Rackham, told me that he had had to leave this man behind with a fractured skull. He had food, money and water, but Lt. Oakes thinks there was very little hope of his recovery.

A day later whilst resting in a jungle glade, the group was caught out by a Japanese patrol. The men had paid the penalty for not placing sentries around the perimeter and a mad panic saw the Chindits racing in all directions to escape the oncoming Japanese. Robert Hyner became separated from his best pal, Bill, and even more disastrously many men left behind their precious packs and rifles. This was the last time Captain Jelliss led the unit and Hyner's group was now down to about 25 men, with Lieutenant Oakes in command.

All discipline had been lost, weapons abandoned and officers struggled with the unfamiliar conditions and had little control over the men. The weary Chindits continued on, marching mostly by moonlight and in the early morning and resting up during the heat of the day to conserve energy. Several men decided to leave the main group and try and make for India on their own. One such soldier was Sgt. J. Jarvis formerly of the KOYLI (Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry), he had been attached to the Commandos on Operation Longcloth and was a seasoned campaigner. Jarvis was never seen again.

Water had now become a serious issue for the dwindling group of Column 7 Chindits. Hyner recalled:

"By now we were making our way along the side of the mountain range, marching by the only compass we still had and keeping our course due west. Our stomachs had forgotten about food; our problem was now water, or the lack of it. One soldier, Private Randall, was so thirsty he passed his own urine into his mug and then drank it. Within seconds of him doing so someone shouted out "water". A finger wide trickle was coming down the mountain side. We rested there a while and took our first good drink for several days, then we filled our water bottles and continued our journey to the top of the mountain."

Around this time an unfortunate accident befell one of the men. Nearly all of the men had discarded or lost their heavy Chindit packs, all that is except for Pte. Gordon David Rackham. Sadly this was to be his undoing. Robert Hyner explains:

"After a few more days we saw in the valley below a river which we decided to make for, still as always, heading west. One soldier Pte. Rackham had not discarded the Everest frame for his pack and he got it caught in some trees and fell over the side of the mountain. We all went down to see what we could do for him. He was so badly injured the officer in charge asked for a volunteer to shoot him, as he, the officer, couldn't possibly do it; but no one volunteered. As he was unable to walk under his own steam Pte. Rackham was left with some water and was made as comfortable as possible. Our intentions were to get help back to him from the next village, which we could actually see from where we now stood."

Sadly for Rackham the men were never able to send back help, as the next village took much longer to reach than first anticipated and was occupied by a Japanese patrol. For Pte. Rackham's CWGC details, please click on the link below:

http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2522158/RACKHAM,%20GORDON%20DAVID

On the 24th November 1943, the commander of No. 7 Column, Major Kenneth Gilkes gave the following witness statement in relation to Pte. Rackham and his eventual fate on Operation Longcloth:

In regards Pte. 5123720 Pte. G. D. Rackham:

Lieut. Oakes, who was in charge of the party which included Rackham, told me that he had had to leave this man behind with a fractured skull. He had food, money and water, but Lt. Oakes thinks there was very little hope of his recovery.

Meanwhile Pte. Charles Aves and his group were moving in a similar direction to that of Pte. Hyner and the men led by Lieutenant Oakes.

Aves remembers:

"We all had rifles, ammunition and grenades, but no food and little water. The Captain was a good officer who decided to involve us in all the decisions we needed to make. We had another bonus, me, as I was the only one who could speak any Burmese. Anyone can make themselves understood in their quest for food, but I was able to ask the villagers for the position of the nearest Japanese patrol and possible danger. We decided to make for the next village. Most of us really found ourselves (spiritually) during this period. We enjoyed being in the jungle, the thicker the better, and we felt safe. We could find paths amongst the undergrowth, however indistinct, we knew that they would eventually lead us to water or the next village.

Capt. Jelliss and I went into the new village, while the others kept watch. The villagers were friendly and helpful, all smiles and generosity. In fact our experiences during that time showed the Burmese to be generally good people. We each obtained a wedge of cooked rice within a large banana leaf envelope. The rice was delicious. The Burmese have a way of presenting boiled rice like I have never tasted since. We ate half of this there and then, and then moved off on our way."

Pte. Hyner's party had been travelling across the grain of the Burmese country for well over a week, with the Japanese in constant pursuit the whole while. In pure desperation they entered the next village they came to and begged the Headman for some food and water. They dined that day on dried fish and rice, paying for the meal with the last of their silver rupees. One of the men from the village offered to guide them to the Chindwin River, Lieutenant Oakes was only too pleased to accept this offer of help. There then followed three difficult days marching, pushing through some of the thickest bamboo jungle imaginable. Apart from hunger, thirst and exhaustion, a new torment began to bother the ailing Chindits, lice!

At the next village the group was very fortunate to receive a meal of rice and chicken, the men lay down after the feast and slowly drifted into sleep. The next morning Robert Hyner remembered looking around at the 15 or so Chindits:

"We no longer looked anything like British soldiers, in fact we looked more like pirates. All our spirits were very low by now and we were still slogging along when we hit the next village on the trail. I walked towards a woman, made a fuss of her baby and began talking to her in English, telling her I was hungry and asking her if she had any food to spare. She returned from her hut with a few bananas and a packet of cooked rice in a banana leaf. I put a couple of silver coins in the baby's hand and thanked her very much. By this time, other villagers had come out of their huts. Straw mats were laid on the ground in the centre of the village, and about fourteen troops sat down and food and drink was put onto the mats, which we thoroughly appreciated.

It was the best village we had ever entered. We had our fill, too much really because our stomachs were swollen and then we realised we had stayed too long. This village was almost on top of the hill and you could see for miles. Suddenly a woman shouted out 'Japanese Japanese'. We looked in the direction she was pointing and we saw a large column of dust, we estimated there were about 300 Japs coming from about half a days march away. The villagers quickly rolled up their mats and covered up all signs that British soldiers had ever been there. The Japanese would have burnt down the village if they found out that we had been present. We thanked them and said to the Headmen that British Forces will be returning soon and that we would tell them of the help they had given us. With Corporal Risedale leading the way we found it hard going now as we had had far too much to eat, but we had to go on because we knew we were being followed now by the Japs. The bloated feeling soon went as time moved on."

The view from the very next mountain top was encouraging, at last, the Chindwin River could be seen. The river valley still took over three more days to reach and all the while the Japanese were gaining ground.

At the next village the group was very fortunate to receive a meal of rice and chicken, the men lay down after the feast and slowly drifted into sleep. The next morning Robert Hyner remembered looking around at the 15 or so Chindits:

"We no longer looked anything like British soldiers, in fact we looked more like pirates. All our spirits were very low by now and we were still slogging along when we hit the next village on the trail. I walked towards a woman, made a fuss of her baby and began talking to her in English, telling her I was hungry and asking her if she had any food to spare. She returned from her hut with a few bananas and a packet of cooked rice in a banana leaf. I put a couple of silver coins in the baby's hand and thanked her very much. By this time, other villagers had come out of their huts. Straw mats were laid on the ground in the centre of the village, and about fourteen troops sat down and food and drink was put onto the mats, which we thoroughly appreciated.

It was the best village we had ever entered. We had our fill, too much really because our stomachs were swollen and then we realised we had stayed too long. This village was almost on top of the hill and you could see for miles. Suddenly a woman shouted out 'Japanese Japanese'. We looked in the direction she was pointing and we saw a large column of dust, we estimated there were about 300 Japs coming from about half a days march away. The villagers quickly rolled up their mats and covered up all signs that British soldiers had ever been there. The Japanese would have burnt down the village if they found out that we had been present. We thanked them and said to the Headmen that British Forces will be returning soon and that we would tell them of the help they had given us. With Corporal Risedale leading the way we found it hard going now as we had had far too much to eat, but we had to go on because we knew we were being followed now by the Japs. The bloated feeling soon went as time moved on."

The view from the very next mountain top was encouraging, at last, the Chindwin River could be seen. The river valley still took over three more days to reach and all the while the Japanese were gaining ground.

Having visited one more Burmese village and obtained some small amounts of rice, the ragged Chindit platoon turned a bend in the valley track which they hoped would lead them to the Chindwin. All at once they were confronted by a soldier from the Seaforth Highlanders, who was on patrol and specifically looking for stragglers from the Chindit expedition. The Seaforth Highlanders had spent the last few weeks moving up and down the eastern banks of the Chindwin River collecting up Longcloth survivors as they scrambled back in their small dispersal groups.

The Scot told them that the last village they had visited contained a large garrison of Japanese troops just a few hours beforehand and that they had been fortunate to avoid being captured or killed. The Seaforth's fed and watered the ailing Chindit platoon and handed out some cigarettes, which were well received. They then escorted the Chindits to a more secure location for recuperation, before sending them on to Tamu by boat. Here the men were kitted out with new clothing, fed again, this time with the first hot meal for over a month, a bully-beef stew. Also at Tamu the men were debriefed by British Army Intelligence, asking questions about their experiences, route on dispersal and the amount of enemy they had seen or encountered along the way. Finally that evening, an Army Padre visited the group and performed a service of thanksgiving.

The remnants of Hyner's platoon were then moved up to Imphal by truck, negotiating those infamous 'hair-pin' bends, with the men holding their breath and some closing their eyes. Robert Hyner recalls:

"We saw so many smashed up vehicles during that journey, we really didn't want to end up going over the top, not after all we had been through over the last three months."

The men were welcomed into the hospital by Senior Matron Agnes McGeary and her staff, they were washed down, de-loused and had their hair cut and beards shaved off. They were now unrecognisable in comparison to the fit and strong men who had crossed the Chindwin just twelve weeks before.

Many men found it hard to adjust to the comforts of hospital life, some still choosing to sleep on the floor instead of the soft matressed beds.

They were treated with compassion at Imphal, with the medical staff taking care of the usual array of ailments and disease. Most men were suffering from a combination of exhaustion, malaria, dysentery and jungle sores. Robert Hyner succumbed to a heavy bout of malaria at Imphal and was later sent up to a hill station in Assam to recuperate properly.

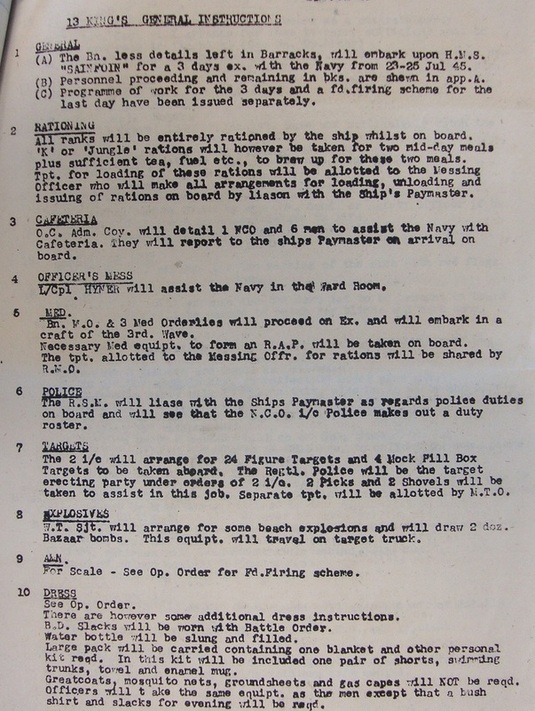

This is where Pte. Hyner's Longcloth story ends. After recovering from his Chindit adventure in 1943, he re-joined the 13th Battalion at their new home, the Napier Barracks in Karachi. He remained with the battalion in India for the rest of the war, being promoted to Lance Corporal at some point in 1945. Confirmation of his new rank can be seen below on an 'orders sheet' for a combined war time exercise between the 13th King's and the Royal Navy. The exercise was rather humorously code-named 'Operation Jacksee'!

The Scot told them that the last village they had visited contained a large garrison of Japanese troops just a few hours beforehand and that they had been fortunate to avoid being captured or killed. The Seaforth's fed and watered the ailing Chindit platoon and handed out some cigarettes, which were well received. They then escorted the Chindits to a more secure location for recuperation, before sending them on to Tamu by boat. Here the men were kitted out with new clothing, fed again, this time with the first hot meal for over a month, a bully-beef stew. Also at Tamu the men were debriefed by British Army Intelligence, asking questions about their experiences, route on dispersal and the amount of enemy they had seen or encountered along the way. Finally that evening, an Army Padre visited the group and performed a service of thanksgiving.

The remnants of Hyner's platoon were then moved up to Imphal by truck, negotiating those infamous 'hair-pin' bends, with the men holding their breath and some closing their eyes. Robert Hyner recalls:

"We saw so many smashed up vehicles during that journey, we really didn't want to end up going over the top, not after all we had been through over the last three months."

The men were welcomed into the hospital by Senior Matron Agnes McGeary and her staff, they were washed down, de-loused and had their hair cut and beards shaved off. They were now unrecognisable in comparison to the fit and strong men who had crossed the Chindwin just twelve weeks before.

Many men found it hard to adjust to the comforts of hospital life, some still choosing to sleep on the floor instead of the soft matressed beds.

They were treated with compassion at Imphal, with the medical staff taking care of the usual array of ailments and disease. Most men were suffering from a combination of exhaustion, malaria, dysentery and jungle sores. Robert Hyner succumbed to a heavy bout of malaria at Imphal and was later sent up to a hill station in Assam to recuperate properly.

This is where Pte. Hyner's Longcloth story ends. After recovering from his Chindit adventure in 1943, he re-joined the 13th Battalion at their new home, the Napier Barracks in Karachi. He remained with the battalion in India for the rest of the war, being promoted to Lance Corporal at some point in 1945. Confirmation of his new rank can be seen below on an 'orders sheet' for a combined war time exercise between the 13th King's and the Royal Navy. The exercise was rather humorously code-named 'Operation Jacksee'!

To read Lance Corporal Robert Hyner's full memoir from 1943 you will need to visit the Imperial War Museum in London and ask for Documents Reference 3700. Please follow the link below for more details:

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1030003680

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2013.

http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1030003680

Copyright © Steve Fogden 2013.