Samuel Ralph Tucker, Chindit Centurion

Ralph Tucker in Army uniform.

Ralph Tucker in Army uniform.

In September last year (2013) I received an email informing me that there was a surviving veteran of the 1943 Chindit Campaign living in the county of Devon.

Samuel Ralph Tucker had just celebrated his 100th birthday in the spring and he was to my knowledge the oldest living Chindit veteran from Operation Longcloth.

Ralph, as he preferred to be called, grew up in Exeter and joined the Devonshire Regiment early on in World War Two. After completing his initial infantry training he struggled with the seemingly endless drills and exercises, and the monotony of barrack room life. He asked for, and was granted a posting overseas, he received a transfer attachment to the 13th Battalion, the King’s Liverpool Regiment, who were at that point serving in India.

Like many men who experienced those turbulent and disturbing years, Ralph did not speak much about his time in India and Burma. Having only just managed to survive the Chindit operation in 1943, if he spoke about anything at all, he would concentrate on his arduous journey out of Burma that year or his time recuperating in India afterwards.

During this latter period Ralph remembered being treated “like a Lord” and being asked to perform some unusual and special duties.

Ralph Tucker was born on the 4th March 1913 and lived in Powderham Road in Exeter. His father had worked at Rice’s Collar Factory in Waterbeer Street. As a young boy Ralph attended the Bluecoat School, followed later on by Exeter Technical School. He was an excellent sportsman and very much enjoyed all outdoor activities. The life skills and attributes learned from this time would prove useful and probably vital during his harrowing time in the Burmese jungle.

Ralph had always set his heart on becoming a railway draughtsman, but sadly the family could not afford the study fees. Instead, he entered the textile industry working for local corporations such as Lear, Brown and Dunsford and Courtaulds.

As mentioned earlier, Ralph enlisted into the Devonshire Regiment and was originally posted to the 12th Battalion at Denbury, near Newton Abbott. Frustrated by the almost continuous training drills he volunteered for special duties and travelled overseas to India in 1942, joining the 13th King’s Liverpool’s at Saugor and thus became one of Wingate’s fledgling Chindit soldiers.

Ralph was placed into Bernard Fergusson’s Column 5 and trained alongside the Commando Platoon.

He remembered:

“I was trained as a sharpshooter and others in the team were the demolition experts. Our work was so secretive and experimental that we were not recognised as a regular Army Regiment.”

Ralph went on to explain:

“Our objective, once inside Burma, was to pave the way for a major offensive, but this was postponed. Then we heard that Wingate had managed to persuade General Wavell to let us go in anyway. All we had is what we basically stood up in and we lived mostly off the land. We used to cook rice in a bamboo cane, we wrapped this in leaves and then would hack off portions to eat along the way.”

Column 5 fared rather badly in regards to supply from the air in 1943, receiving just twenty days rations from the RAF during their ten weeks inside Burma.

The one hundred year old Chindit recalled:

“It was all about rivers and railways. The jungle was so dense that you could be just an arms length away from a Jap soldier and not be aware he was there. Of course he did not know we were about either.”

Column 5 were given the task of blowing up the railway at a place called Bonchaung, Ralph’s partners in the demolition squad achieved this aim and the unit disappeared once more into the jungle. After many more weeks of marching and counter-marching Column 5 were given the unenviable task of rear guard as the main body of the Brigade attempted to return to India.

Of the three Chindit columns made up of mainly British troops, Column 5 were to loose over two thirds of their number in 1943, men either disappeared along the paths and tracks of the jungle or became prisoners to the Japanese, with most of these perishing inside Rangoon Jail.

Ralph remembered this time well:

“We soon had to make our own way back to India. I was fortunate to receive a lot of help and kindness from friendly Burmese villagers along the way. A lot of our chaps never did come out. After many weeks of marching, covering in excess of 600 hundred miles I reached the safety of the Assam border.”

“I was a mere six stone when I reached the Military Hospital at Imphal. They put me in a tub of disinfectant and burned my clothes. I had malaria and could only eat liquid foods due to my shrunken stomach.”

After a long recuperation period in hospital, Ralph was given many special duties by the Army, including courier services, where he transported important documents to places all over India. He was offered a commission into the Indian Army, but declined, as this would have meant staying in India for at least another year. He had already served overseas longer than most and decided it was time to return home. Ralph never met any of his Chindit comrades again.

When asked about his favourite memory from those times he answered:

“An unforgettable memory for me was sitting on a mountain top at a place called Murree, which is in present day Pakistan and being able to see several different countries and Mount Everest from the same spot.”

Ralph flew out of Karachi and headed home in a Liberator aircraft that was going back to the UK for maintenance work. After a brief stop over at Tel Aviv, he landed at Merryfield Aerodrome near Tauton in Somerset. From here he travelled by train to London.

After demob he returned to his former job at Lear, Brown and Dunsford. In 1946 he met Gwen, his wife to be, at a speedway meeting in Exeter, they married in St. Thomas’s Church and went on to raise a family of five children.

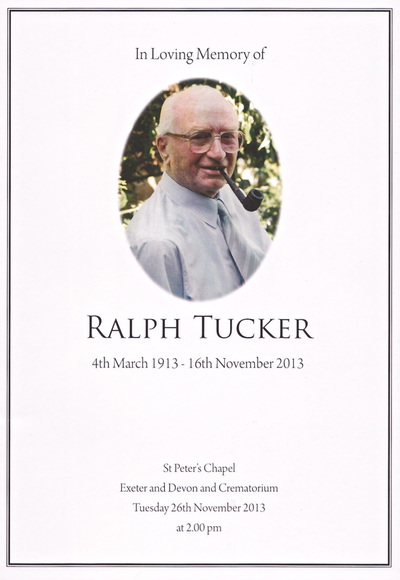

Sadly, having reached the great landmark of his 100th birthday in March, Ralph died peacefully at home on the 16th November 2013. He left behind his dear wife Gwen and all his wonderful family. His funeral was held at the Exeter and Devon Crematorium on the 26th November and was attended by family, friends and representatives of the ‘Friends of the Chindits’ organisiation.

This obituary is dedicated to the family of Samuel Ralph Tucker, a Chindit Centurion, one of the few fortunate soldiers to survive the rigours of Wingate’s first expedition. To paraphrase a famous quote by Brigadier Mike Calvert:

“Chindits never actually die, they just go to heaven and regroup, after all, they have been through hell already.”

Featured below, some photographs of Ralph and his wife, Gwen. Please click on any image to bring it forward.

Samuel Ralph Tucker had just celebrated his 100th birthday in the spring and he was to my knowledge the oldest living Chindit veteran from Operation Longcloth.

Ralph, as he preferred to be called, grew up in Exeter and joined the Devonshire Regiment early on in World War Two. After completing his initial infantry training he struggled with the seemingly endless drills and exercises, and the monotony of barrack room life. He asked for, and was granted a posting overseas, he received a transfer attachment to the 13th Battalion, the King’s Liverpool Regiment, who were at that point serving in India.

Like many men who experienced those turbulent and disturbing years, Ralph did not speak much about his time in India and Burma. Having only just managed to survive the Chindit operation in 1943, if he spoke about anything at all, he would concentrate on his arduous journey out of Burma that year or his time recuperating in India afterwards.

During this latter period Ralph remembered being treated “like a Lord” and being asked to perform some unusual and special duties.

Ralph Tucker was born on the 4th March 1913 and lived in Powderham Road in Exeter. His father had worked at Rice’s Collar Factory in Waterbeer Street. As a young boy Ralph attended the Bluecoat School, followed later on by Exeter Technical School. He was an excellent sportsman and very much enjoyed all outdoor activities. The life skills and attributes learned from this time would prove useful and probably vital during his harrowing time in the Burmese jungle.

Ralph had always set his heart on becoming a railway draughtsman, but sadly the family could not afford the study fees. Instead, he entered the textile industry working for local corporations such as Lear, Brown and Dunsford and Courtaulds.

As mentioned earlier, Ralph enlisted into the Devonshire Regiment and was originally posted to the 12th Battalion at Denbury, near Newton Abbott. Frustrated by the almost continuous training drills he volunteered for special duties and travelled overseas to India in 1942, joining the 13th King’s Liverpool’s at Saugor and thus became one of Wingate’s fledgling Chindit soldiers.

Ralph was placed into Bernard Fergusson’s Column 5 and trained alongside the Commando Platoon.

He remembered:

“I was trained as a sharpshooter and others in the team were the demolition experts. Our work was so secretive and experimental that we were not recognised as a regular Army Regiment.”

Ralph went on to explain:

“Our objective, once inside Burma, was to pave the way for a major offensive, but this was postponed. Then we heard that Wingate had managed to persuade General Wavell to let us go in anyway. All we had is what we basically stood up in and we lived mostly off the land. We used to cook rice in a bamboo cane, we wrapped this in leaves and then would hack off portions to eat along the way.”

Column 5 fared rather badly in regards to supply from the air in 1943, receiving just twenty days rations from the RAF during their ten weeks inside Burma.

The one hundred year old Chindit recalled:

“It was all about rivers and railways. The jungle was so dense that you could be just an arms length away from a Jap soldier and not be aware he was there. Of course he did not know we were about either.”

Column 5 were given the task of blowing up the railway at a place called Bonchaung, Ralph’s partners in the demolition squad achieved this aim and the unit disappeared once more into the jungle. After many more weeks of marching and counter-marching Column 5 were given the unenviable task of rear guard as the main body of the Brigade attempted to return to India.

Of the three Chindit columns made up of mainly British troops, Column 5 were to loose over two thirds of their number in 1943, men either disappeared along the paths and tracks of the jungle or became prisoners to the Japanese, with most of these perishing inside Rangoon Jail.

Ralph remembered this time well:

“We soon had to make our own way back to India. I was fortunate to receive a lot of help and kindness from friendly Burmese villagers along the way. A lot of our chaps never did come out. After many weeks of marching, covering in excess of 600 hundred miles I reached the safety of the Assam border.”

“I was a mere six stone when I reached the Military Hospital at Imphal. They put me in a tub of disinfectant and burned my clothes. I had malaria and could only eat liquid foods due to my shrunken stomach.”

After a long recuperation period in hospital, Ralph was given many special duties by the Army, including courier services, where he transported important documents to places all over India. He was offered a commission into the Indian Army, but declined, as this would have meant staying in India for at least another year. He had already served overseas longer than most and decided it was time to return home. Ralph never met any of his Chindit comrades again.

When asked about his favourite memory from those times he answered:

“An unforgettable memory for me was sitting on a mountain top at a place called Murree, which is in present day Pakistan and being able to see several different countries and Mount Everest from the same spot.”

Ralph flew out of Karachi and headed home in a Liberator aircraft that was going back to the UK for maintenance work. After a brief stop over at Tel Aviv, he landed at Merryfield Aerodrome near Tauton in Somerset. From here he travelled by train to London.

After demob he returned to his former job at Lear, Brown and Dunsford. In 1946 he met Gwen, his wife to be, at a speedway meeting in Exeter, they married in St. Thomas’s Church and went on to raise a family of five children.

Sadly, having reached the great landmark of his 100th birthday in March, Ralph died peacefully at home on the 16th November 2013. He left behind his dear wife Gwen and all his wonderful family. His funeral was held at the Exeter and Devon Crematorium on the 26th November and was attended by family, friends and representatives of the ‘Friends of the Chindits’ organisiation.

This obituary is dedicated to the family of Samuel Ralph Tucker, a Chindit Centurion, one of the few fortunate soldiers to survive the rigours of Wingate’s first expedition. To paraphrase a famous quote by Brigadier Mike Calvert:

“Chindits never actually die, they just go to heaven and regroup, after all, they have been through hell already.”

Featured below, some photographs of Ralph and his wife, Gwen. Please click on any image to bring it forward.

Copyright © Steve Fogden April 2014.