Sergeant Fred Thompson

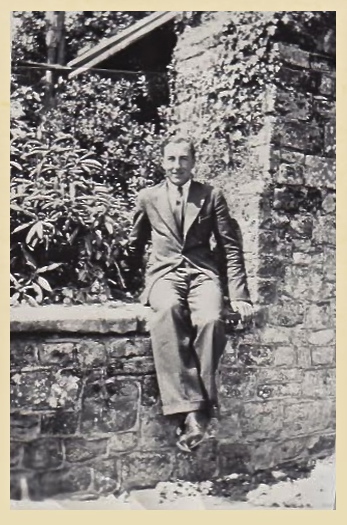

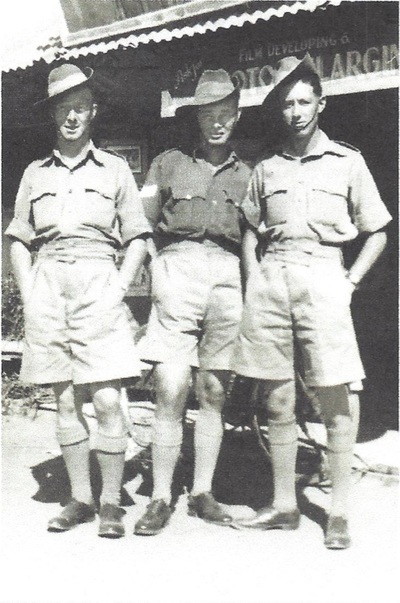

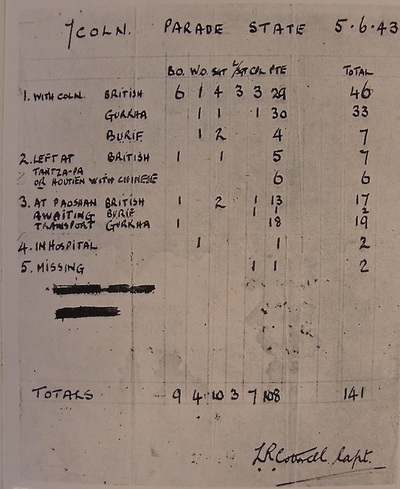

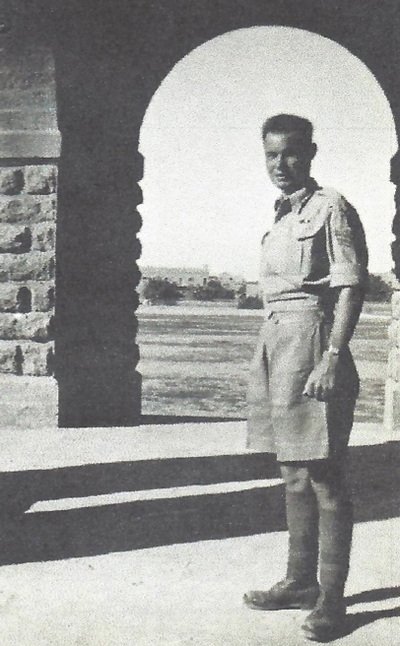

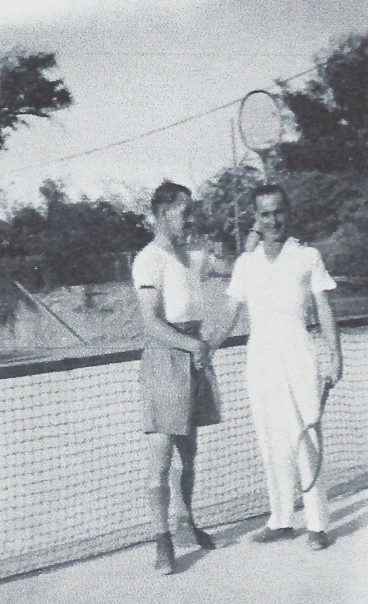

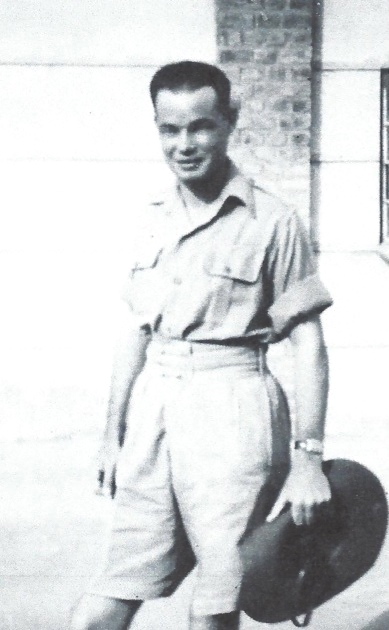

Fred Thompson, Karachi 1944.

Fred Thompson, Karachi 1944.

In December 2013, I was extremely fortunate to receive an email contact from the nephew of Sergeant Fred Thompson, who served with 7 Column on Operation Longcloth. Nephew Alan Lawrence informed me that his uncle, although well into his nineties, was still very bright in his demeanour and would very much enjoy a conversation with me about his time in India and Burma. I made that telephone call on the 15th December 2013 and spoke to Fred for around 40 minutes.

Fred, who now lives in North Wales, spoke with a slight Liverpool accent. He told me that he had started his Army service with the Head Quarters Group of the 9th Battalion, the Royal Welch Fusiliers. He took no time in informing me that:

"My heart was and still is with the Royal Welch Fusiliers, although I served with the 13th and 1st King's in Burma, these were only attachments to me. I enjoyed my time with the 13th King's and of course this was my most active role in WW2, my time with the 1st Battalion after Longcloth was not so memorable."

Fred was posted overseas whilst part of the 8th Battalion, the Royal Welch Fusiliers and it was after arriving at the Deolali Reinforcement Camp in India that he was transferred to the 13th King's.

At first we talked about my research and in particular my own grandfather and his membership of 5 Column in 1943. Fred told me that in his view, Fergusson and his men were used by Wingate to do his (Wingate's) dirty work, by acting as rear-guard and decoy for Brigade Head Quarters. I asked Fred if he remembered any of his colleagues or mates from Column 7. He said he couldn't really, although he had kept in touch with one man, who was a bus conductor from Manchester, but they had lost touch back in the late 1960's.

Fred hasn't really kept up with news from the Burma Star Association or the Chindit Old Comrades organisation and he does not read Dekho magazine. However, he has left some of his documents and a hand written memoir with the Imperial War Museum, but more of this later.

Fred told me, that it was at Deolali and then again whilst stationed at Poona, that he first heard the rumours about Wingate and his so called circus. Of course he had no idea then, that he would eventually end up joining this 'circus' at the Chindit training camp in Saugor. In regards to 1943, he said that they had been lucky that the Japanese did not realise for a long while that the Chindits were being supplied from the air, otherwise they would have been on their tails much quicker.

One name that Fred did mention during our phone call was that of Sgt. E. Whittaker of Brigade HQ. He told me that Whittaker and he had got to know each other well during training, but that he had no idea if he had survived the operation in 1943. I was able to inform him that Sgt. Whittaker was one of the fortunate men to be flown out of Burma, aboard the Dakota aircraft that had managed to land in a jungle clearing at the behest of 8 Column's commanding officer, Major Walter Purcell Scott.

I asked Fred if he remembered any of his commanding officers from 7 Column. He told me that he had known Column Adjutant, Captain Leslie Cottrell from his school years at Dovedale Road School in Liverpool, but had not spent much time in his company during Operation Longcloth. He also recalled Lieutenant Dennis Chambers, who he told me was in charge of the Column Gurkhas and had been killed by a Japanese sniper's bullet at the village of Baw.

Fred told me that when he joined the ranks of 7 Column he felt a bit like a spare part. He had been an Intelligence Sergeant in previous units and so, quite naturally Major Gilkes placed him in charge of recording the column's routes and daily map references whilst in Burma. He mentioned that the maps issued to the Chindits were of the half-inch variety, with large areas left bank and described as unchartered or un-surveyed.

He recounted an amusing conversation between himself and the Major after the Column had been in Burma for approximately eight weeks:

Gilkes: "So Thompson, where do you think we are then?"

Thompson: "I am not sure sir"

Gilkes: "Well Sergeant, you should jolly well know where we are, you have the maps!"

Thompson: "Yes sir, but there is nothing bloody well written on them!".

He described his long walk out through the Chinese borders and how the Chinese villagers and doctors had helped him immensely during this time and effectively saved his life. He had formed an allergic reaction to rice or any form of starch and this posed great problems for him as he could not hold on to any of the local rice for very long. As Fred put it: "I either shit it out or else it came out of the top end."

He told me that the Chinese managed to find him some meat to help solve his digestive problems. "The meat they gave me did the world of good and put me back on my feet again, but let me tell you that meat was in fact rat!"

Fred went on to say that: "the Chinese people were marvellous, especially when you consider they had very little food and materials for themselves, let alone for 150 starving British." He said that he gets annoyed whenever he hears people calling the Chinese this or that today, especially on the news programmes. He finished by telling me that he and other men from 7 Column had marched over 1500 miles by the time they arrived back in India in July 1943.

After Longcloth Fred was stationed at Karachi with the 13th King's until he was transferred to the 1st Battalion of the King's Regiment. He told me that the 1st King's were then to be turned into a Parachute Battalion, but that he had declined to volunteer for this posting. We then spoke about the 13th King's that lost their lives in 1943, he was particularly interested in why some men ended up being buried at Rangoon War Cemetery, whilst others seemed to have no grave. I told him that the majority of the men buried at Rangoon War Cemetery had perished inside Rangoon Jail as prisoners of war and that most of the other casualties from Longcloth had died in the jungle or in the Yunnan Provinces of China and were remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery; a memorial dedicated to those with no officially recorded final resting place.

I asked Fred if he would be happy for me to write about him and our conversation. He said that he wouldn't mind some press coverage especially at his age, his remark was very tongue in cheek. He told me that he was indebted to his computer as it kept him in touch with the outside world. I asked if he could use email. He laughed and said how do you think I order my groceries from Tesco! What a wonderful and charmingly witty man. I am happy to say that I was able to send Fred some of the War diaries for his beloved 9th Royal Welch Fusiliers, which I believe he very much enjoyed reading.

Seen below are images of some of the men mentioned in the above account, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Fred, who now lives in North Wales, spoke with a slight Liverpool accent. He told me that he had started his Army service with the Head Quarters Group of the 9th Battalion, the Royal Welch Fusiliers. He took no time in informing me that:

"My heart was and still is with the Royal Welch Fusiliers, although I served with the 13th and 1st King's in Burma, these were only attachments to me. I enjoyed my time with the 13th King's and of course this was my most active role in WW2, my time with the 1st Battalion after Longcloth was not so memorable."

Fred was posted overseas whilst part of the 8th Battalion, the Royal Welch Fusiliers and it was after arriving at the Deolali Reinforcement Camp in India that he was transferred to the 13th King's.

At first we talked about my research and in particular my own grandfather and his membership of 5 Column in 1943. Fred told me that in his view, Fergusson and his men were used by Wingate to do his (Wingate's) dirty work, by acting as rear-guard and decoy for Brigade Head Quarters. I asked Fred if he remembered any of his colleagues or mates from Column 7. He said he couldn't really, although he had kept in touch with one man, who was a bus conductor from Manchester, but they had lost touch back in the late 1960's.

Fred hasn't really kept up with news from the Burma Star Association or the Chindit Old Comrades organisation and he does not read Dekho magazine. However, he has left some of his documents and a hand written memoir with the Imperial War Museum, but more of this later.

Fred told me, that it was at Deolali and then again whilst stationed at Poona, that he first heard the rumours about Wingate and his so called circus. Of course he had no idea then, that he would eventually end up joining this 'circus' at the Chindit training camp in Saugor. In regards to 1943, he said that they had been lucky that the Japanese did not realise for a long while that the Chindits were being supplied from the air, otherwise they would have been on their tails much quicker.

One name that Fred did mention during our phone call was that of Sgt. E. Whittaker of Brigade HQ. He told me that Whittaker and he had got to know each other well during training, but that he had no idea if he had survived the operation in 1943. I was able to inform him that Sgt. Whittaker was one of the fortunate men to be flown out of Burma, aboard the Dakota aircraft that had managed to land in a jungle clearing at the behest of 8 Column's commanding officer, Major Walter Purcell Scott.

I asked Fred if he remembered any of his commanding officers from 7 Column. He told me that he had known Column Adjutant, Captain Leslie Cottrell from his school years at Dovedale Road School in Liverpool, but had not spent much time in his company during Operation Longcloth. He also recalled Lieutenant Dennis Chambers, who he told me was in charge of the Column Gurkhas and had been killed by a Japanese sniper's bullet at the village of Baw.

Fred told me that when he joined the ranks of 7 Column he felt a bit like a spare part. He had been an Intelligence Sergeant in previous units and so, quite naturally Major Gilkes placed him in charge of recording the column's routes and daily map references whilst in Burma. He mentioned that the maps issued to the Chindits were of the half-inch variety, with large areas left bank and described as unchartered or un-surveyed.

He recounted an amusing conversation between himself and the Major after the Column had been in Burma for approximately eight weeks:

Gilkes: "So Thompson, where do you think we are then?"

Thompson: "I am not sure sir"

Gilkes: "Well Sergeant, you should jolly well know where we are, you have the maps!"

Thompson: "Yes sir, but there is nothing bloody well written on them!".

He described his long walk out through the Chinese borders and how the Chinese villagers and doctors had helped him immensely during this time and effectively saved his life. He had formed an allergic reaction to rice or any form of starch and this posed great problems for him as he could not hold on to any of the local rice for very long. As Fred put it: "I either shit it out or else it came out of the top end."

He told me that the Chinese managed to find him some meat to help solve his digestive problems. "The meat they gave me did the world of good and put me back on my feet again, but let me tell you that meat was in fact rat!"

Fred went on to say that: "the Chinese people were marvellous, especially when you consider they had very little food and materials for themselves, let alone for 150 starving British." He said that he gets annoyed whenever he hears people calling the Chinese this or that today, especially on the news programmes. He finished by telling me that he and other men from 7 Column had marched over 1500 miles by the time they arrived back in India in July 1943.

After Longcloth Fred was stationed at Karachi with the 13th King's until he was transferred to the 1st Battalion of the King's Regiment. He told me that the 1st King's were then to be turned into a Parachute Battalion, but that he had declined to volunteer for this posting. We then spoke about the 13th King's that lost their lives in 1943, he was particularly interested in why some men ended up being buried at Rangoon War Cemetery, whilst others seemed to have no grave. I told him that the majority of the men buried at Rangoon War Cemetery had perished inside Rangoon Jail as prisoners of war and that most of the other casualties from Longcloth had died in the jungle or in the Yunnan Provinces of China and were remembered upon the Rangoon Memorial at Taukkyan War Cemetery; a memorial dedicated to those with no officially recorded final resting place.

I asked Fred if he would be happy for me to write about him and our conversation. He said that he wouldn't mind some press coverage especially at his age, his remark was very tongue in cheek. He told me that he was indebted to his computer as it kept him in touch with the outside world. I asked if he could use email. He laughed and said how do you think I order my groceries from Tesco! What a wonderful and charmingly witty man. I am happy to say that I was able to send Fred some of the War diaries for his beloved 9th Royal Welch Fusiliers, which I believe he very much enjoyed reading.

Seen below are images of some of the men mentioned in the above account, please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

As mentioned earlier, Fred Thompson has left a personal memoir in regards to his WW2 service with the Imperial War Museum in London. I am very grateful to him for allowing me to reproduce this memoir on these website pages. For details of how to view Fred's original and handwritten version, please click on the following link to the IWM website: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1030019808

“Fred’s Story”, the memoir of Sgt. Frederick Thompson, a member of Chindit Column 7

My involvement with the Wingate Chindit operation started in England when I was posted from the 115th Brigade Headquarters at Beaminster, Dorset, to the 8th Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers at Piddlehinton in March 1942, to take a draft of men abroad, no idea at the time where to.

At this time Marjorie (Fred's girlfriend) having been directed to work at the Ministry of Food, which had been moved to Colwyn Bay, was lodging with Mrs. Evans, 25 Vale Road, Rhyl and did not like the clerical work. I was given two weeks embarkation leave so spent the first week at Rhyl and then went home to Liverpool for the remainder. NB. Marjorie ended up working with the Women’s Land Army at a farm in Holywell, North Wales.

After this leave, with a very difficult parting, not knowing if or when we would see each other again, I returned to the 8th RWF to await transport details and equipment. We were issued with ancient tropical kit, drain pipe trousers, a buttoned to the neck jacket with brass buttons down the front, Wolsey helmet and white sea kit bag to be kept onboard, whilst the main kit bag went into the hold of the boat.

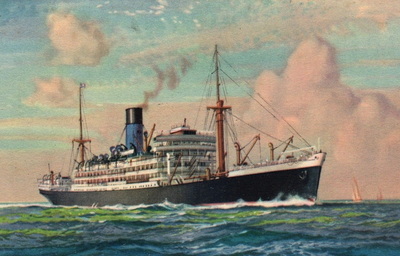

Finally, movement orders came and I knew from previous drafts that if we received two haversack rations we were headed for Glasgow or Liverpool and Liverpool it was. We boarded the train at Crewkerne near Yeovil and finally arrived at Aintree and were taken on buses to Pier Head where we boarded the troopship ‘Antenor’.

My involvement with the Wingate Chindit operation started in England when I was posted from the 115th Brigade Headquarters at Beaminster, Dorset, to the 8th Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers at Piddlehinton in March 1942, to take a draft of men abroad, no idea at the time where to.

At this time Marjorie (Fred's girlfriend) having been directed to work at the Ministry of Food, which had been moved to Colwyn Bay, was lodging with Mrs. Evans, 25 Vale Road, Rhyl and did not like the clerical work. I was given two weeks embarkation leave so spent the first week at Rhyl and then went home to Liverpool for the remainder. NB. Marjorie ended up working with the Women’s Land Army at a farm in Holywell, North Wales.

After this leave, with a very difficult parting, not knowing if or when we would see each other again, I returned to the 8th RWF to await transport details and equipment. We were issued with ancient tropical kit, drain pipe trousers, a buttoned to the neck jacket with brass buttons down the front, Wolsey helmet and white sea kit bag to be kept onboard, whilst the main kit bag went into the hold of the boat.

Finally, movement orders came and I knew from previous drafts that if we received two haversack rations we were headed for Glasgow or Liverpool and Liverpool it was. We boarded the train at Crewkerne near Yeovil and finally arrived at Aintree and were taken on buses to Pier Head where we boarded the troopship ‘Antenor’.

As a Sergeant I shared a cabin with another Sergeant from the Loyals and we were told not to shut the cabin door, but to leave it slightly open so that if we were hit by a torpedo it would not jam and trap us in. Another piece of advice was, should we have to jump into the sea with our life jackets on, to hold the front very firmly, otherwise the impact would jerk the head back with fatal results. We sailed the same night and next day we anchored off Greenock to await the convoy.

We waited there for five days until the other ships arrived; the convoy was a fast one with four troopers and two fast cargo ships. Our escort was five destroyers and a cruiser named the ‘Hawkins’. We set sail on May 20th in thick fog, our ship kept company with the one ahead by following its log line wake. We were glad of the fog as U-boats were known to patrol these waters.

NB. It is highly likely that Fred voyaged to India as part of Convoy WS21. This was the only convoy in 1942 that had both the SS Antenor and the cruiser 'Hawkins' present in any formation of ships. For more information about convoy WS21, please click on the following link: http://www.naval-history.net/xAH-WSConvoys05-1942B.htm

Fred continues:

We made a big sweep into the Atlantic, our watches altered by two hours. We Sergeants had to dress for dinner which was served in a large dining room. Men were on the mess decks converted from the cargo holds and had to collect their food from the cookhouse on deck and eat from narrow tables with their hammocks slung above.

No lit cigarettes were allowed on deck at night, nor was smoking allowed on mess decks, but the air was still blue down there! Cigarettes were available from the ships store and as no tax was due, a tin of 50 cost about 1’6d. Fresh water was only used for drinking and shaving. Baths and showers were available, but it was cold sea water and not very refreshing.

It was just sea, ships and sky, with the occasional flying fish being chased by a dolphin, for a while we had a dolphin swimming with us near the bow of our ship. Freetown, Sierra Leone was our next stop, escorted into harbour by a couple of Sunderland flying boats due to the frequent presence of U-Boats. By then our naval escort was down to just two destroyers and the ‘Hawkins’.

On leaving Freetown it was out into the South Atlantic to about 15 degrees west, with out next stop at Durban. We were allowed on shore for five days and we were greeted by local people who invited us in to their homes for a hot bath or a lovely meal. I made Marjorie jealous by describing the chocolate and fruit available in South Africa and not available at home. We watched men bringing nets of oranges and bananas back to the ship. After the five days we were off again, being sung farewell at the dockside by Perla Siedle, the ‘Lady in White’.

Our convoy had now split, ourselves and the ’Apapa’ escorted by our cruiser to Bombay, the others to Suez. Just before our arrival at Bombay the ‘Hawkins’ sailed close to our ships with the band playing, this was greeted with loud cheers from our troops.

We disembarked at Bombay in late August after two months at sea; it was a shock seeing so many beggars lying in the road and on station platforms. We boarded an electric train to Poona, then by steam train to Deolali, where we waited for postings and hearing a lot about Wingate’s Private Army. I and about 80 others were posted to 13th King’s Liverpool Regiment, to bring this unit back up to strength. The Loyal's Sergeant was sent to a unit fighting in the Arakan and was badly wounded.

On arrival at the King’s base I was allocated to C Company, which became Chindit Column number 7. It came as a shock to the Officer commanding, Major Gilkes that I had very little parade or battle training, due to being in Administrative posts previously. I became for a while, an odd Sergeant with no definite job.

Next we were kitted out, replacing our ships tropical kit for decent jungle attire and out Wolsey helmet for a bush hat. I was quite badly affected by the heat and all I wanted to do was drink, food did not interest me and in this condition I made the 20 mile march to our jungle training camp near Saugor.

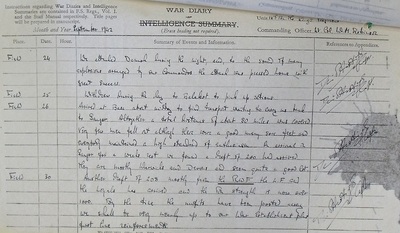

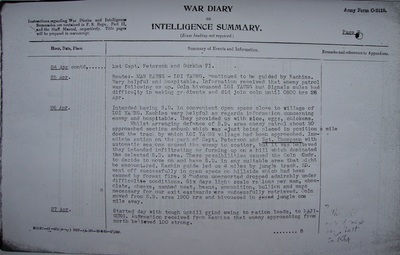

NB. According to the War diary for 13th King's in 1942, Fred and the other men from the Royal Welch Fusiliers, arrived at the Saugor training camp on the 30th September. They were part of a new reinforcement draft, comprising of RWF's, Lancashire Fusiliers and men from the Loyal Regiment. Please see the war diary page in the gallery below.

Being city men, going straight into the jungle was a shock, first we had to make ourselves some kind of shelter, our ‘basha’. Food was supplied by a central, open-air cookhouse and we learnt very quickly to protect our meat when going from the cookhouse to our bashas from the Kite Hawks, who would swoop down and swipe the meat from off our plates. Training started with marching in single file and dispersing into the jungle and night exercises with small parties sent out on compass bearing. Slowly, chaos became order, sections were now formed, Bren gun teams set up, this was followed by the addition of Medical staff, Signallers and then RAF officers with their teams and Commandos whose job it was to set explosives and carry out demolitions. At this time, I and two other Sergeants were given leave to go to Secunderabad; I was the only one of these three to survive the Chindit expedition.

We waited there for five days until the other ships arrived; the convoy was a fast one with four troopers and two fast cargo ships. Our escort was five destroyers and a cruiser named the ‘Hawkins’. We set sail on May 20th in thick fog, our ship kept company with the one ahead by following its log line wake. We were glad of the fog as U-boats were known to patrol these waters.

NB. It is highly likely that Fred voyaged to India as part of Convoy WS21. This was the only convoy in 1942 that had both the SS Antenor and the cruiser 'Hawkins' present in any formation of ships. For more information about convoy WS21, please click on the following link: http://www.naval-history.net/xAH-WSConvoys05-1942B.htm

Fred continues:

We made a big sweep into the Atlantic, our watches altered by two hours. We Sergeants had to dress for dinner which was served in a large dining room. Men were on the mess decks converted from the cargo holds and had to collect their food from the cookhouse on deck and eat from narrow tables with their hammocks slung above.

No lit cigarettes were allowed on deck at night, nor was smoking allowed on mess decks, but the air was still blue down there! Cigarettes were available from the ships store and as no tax was due, a tin of 50 cost about 1’6d. Fresh water was only used for drinking and shaving. Baths and showers were available, but it was cold sea water and not very refreshing.

It was just sea, ships and sky, with the occasional flying fish being chased by a dolphin, for a while we had a dolphin swimming with us near the bow of our ship. Freetown, Sierra Leone was our next stop, escorted into harbour by a couple of Sunderland flying boats due to the frequent presence of U-Boats. By then our naval escort was down to just two destroyers and the ‘Hawkins’.

On leaving Freetown it was out into the South Atlantic to about 15 degrees west, with out next stop at Durban. We were allowed on shore for five days and we were greeted by local people who invited us in to their homes for a hot bath or a lovely meal. I made Marjorie jealous by describing the chocolate and fruit available in South Africa and not available at home. We watched men bringing nets of oranges and bananas back to the ship. After the five days we were off again, being sung farewell at the dockside by Perla Siedle, the ‘Lady in White’.

Our convoy had now split, ourselves and the ’Apapa’ escorted by our cruiser to Bombay, the others to Suez. Just before our arrival at Bombay the ‘Hawkins’ sailed close to our ships with the band playing, this was greeted with loud cheers from our troops.

We disembarked at Bombay in late August after two months at sea; it was a shock seeing so many beggars lying in the road and on station platforms. We boarded an electric train to Poona, then by steam train to Deolali, where we waited for postings and hearing a lot about Wingate’s Private Army. I and about 80 others were posted to 13th King’s Liverpool Regiment, to bring this unit back up to strength. The Loyal's Sergeant was sent to a unit fighting in the Arakan and was badly wounded.

On arrival at the King’s base I was allocated to C Company, which became Chindit Column number 7. It came as a shock to the Officer commanding, Major Gilkes that I had very little parade or battle training, due to being in Administrative posts previously. I became for a while, an odd Sergeant with no definite job.

Next we were kitted out, replacing our ships tropical kit for decent jungle attire and out Wolsey helmet for a bush hat. I was quite badly affected by the heat and all I wanted to do was drink, food did not interest me and in this condition I made the 20 mile march to our jungle training camp near Saugor.

NB. According to the War diary for 13th King's in 1942, Fred and the other men from the Royal Welch Fusiliers, arrived at the Saugor training camp on the 30th September. They were part of a new reinforcement draft, comprising of RWF's, Lancashire Fusiliers and men from the Loyal Regiment. Please see the war diary page in the gallery below.

Being city men, going straight into the jungle was a shock, first we had to make ourselves some kind of shelter, our ‘basha’. Food was supplied by a central, open-air cookhouse and we learnt very quickly to protect our meat when going from the cookhouse to our bashas from the Kite Hawks, who would swoop down and swipe the meat from off our plates. Training started with marching in single file and dispersing into the jungle and night exercises with small parties sent out on compass bearing. Slowly, chaos became order, sections were now formed, Bren gun teams set up, this was followed by the addition of Medical staff, Signallers and then RAF officers with their teams and Commandos whose job it was to set explosives and carry out demolitions. At this time, I and two other Sergeants were given leave to go to Secunderabad; I was the only one of these three to survive the Chindit expedition.

On our return we found the mules had arrived, tall strong ones to carry the mortars and machine guns, other smaller animals to carry ammunition and signal sets. I had a mule with two panniers to carry maps for which I was responsible. These maps covered most of Burma and were half inch to the mile and seemed to have large amounts of white areas, simply marked ‘unsurveyed’!

The next job was to have the mules accept their saddler and loads, this was quite a job and with a few bruises received from their kicks. Each mule had a muleteer to look after it and it was surprising the bond that developed. Wingate was active, giving us talks on communications with our families with an Airmail letter sent each month to our next of kin, telling them we were alive and well or otherwise, we in turn were to ask our families to continue writing as we could have letters delivered along with our supplies.

There was no evacuation of the wounded or sick and if unable to keep up with the column, you would be left in a friendly village; all ranks had at least 25 silver rupees with them to pay for anything obtained. We were encouraged to grow beards; the idea was to save water, increase sleeping time and to help protect ourselves against mosquitoes.

Our tactics were to disrupt Japanese communications thus helping and advancing force, hit and run with no pitched battle unless totally unavoidable. Our faith in him (Wingate) was implicit, we being young thought ourselves fireproof and these talks usually ended with some biblical quotation. Various exercises were held to get used to loading and unloading the mules. After loading up we would often halt after half and hour to tighten the belt around their stomachs, this stopped the loads from slipping later on. It was essential to keep the mules load balanced.

The final training exercise was an attack on the Jhansi Railway Station 120 miles away from our camp. The station was defended by Indian troops. It was a dull and gruelling task, in that we had to attack from the North and cover over 180 miles in nine days. I was at the rear of our column and quite often found myself running to keep up as gaps appeared.

We had full packs and ammunition and for the last 20 miles we dumped these packs, this made us feel that we had wings on our feet. The attack was a success, but could not have been otherwise as the troops against us were almost new recruits.

We were now camped in Jhansi and there followed about two weeks of feverish preparation, all white underwear and apparel had to be died khaki, equipment checked and all deficiencies made up. We were issued with new and comfortable well studded boots. Rumours said (char wallah brand) that we would entrain for Assam the second or third week in January 1943. No one had any idea at the time about the nature of the fighting and the hardships that lay ahead. We did realise it was not going to be a cake walk, but were not unduly worried.

At this time a new frame for our packs was offered which I took. This allowed an air pocket between the pack and my back and reduced perspiration. Due to a shortage of officers and men the remnants of Column 6 was split up among the other three British Columns. The first to entrain were the mules and then ourselves, we travelled to a station north of Calcutta, transferred to a river steamer on the Brahmaputra River and then picked up the narrow gauge railway at Diburgarh. We reached Dimapur and then marched on foot to Imphal on the Manipur Road.

I did not se much of the Manipur Road because we marched along it at night, by day motor convoys were driving up and down and we would have caused chaos. We saw many vehicles in the valley that had failed to navigate the twists and turns in the road. We marched by stages, started at dusk, with a halt during the night for a brew up, then early the next morning meet our guides who led us into the next staging camp. We needed our blankets here because it was very cold as we were about 5000 feet up.

Daylight would sometimes give us some magnificent views, but at other times we would be in mist or rain. We marched in threes instead of the column snake and I am sure at times I was asleep as we marched. After nine days on the road covering about 120 miles we came to Imphal and pitched camp, made our own shelter and prepared for the visit of General Wavell.

The plan in which we were to assist did not materialise and it was not known if we would go in to Burma alone or the mission cancelled. In the end it was decided we should go it alone and instead of saluting the General, he saluted us. It was early February when we left camp all shaven and shorn and made our way to the Chindwin River, crossing at a place called Tonhe.

About this time the Burma Rifle contingent joined us. To cross the river we had rubber boats and RAF dinghies and were able to hire some native boats too. Those that could swim went over that way, the non-swimmers holding on to a mule or in boats. I do not remember a great deal about the crossing, but after all equipment, men and mules were over we formed up with our water bottles full, as ahead of us was a two day march, guided by a Burmese Forestry Officer (Major Hubert Castens) over a trail without water, which we hoped would bring us well behind any Jap positions.

We were carrying five days rations, with blankets, clothing change and groundsheet and in my case Bren gun pouches full of 20 round magazines for my Thomson sub machine gun. We also had a 50 round bandolier of 303 ammunition and three grenades held on a belt by their clips. Altogether we were carrying around 60-70 lbs. of kit.

During this section of the march we were accompanied by a host of chattering monkeys and kept awake by cicadas which made a noise like a circular saw. We eventually emerged from this trail well behind the Japanese outposts.The Japs knew we were in Burma, but spent their time looking for our lines of communication, not realising we were being supplied by air.

Seen below are photographs of two of the officers from the 2nd Burma Rifles, who commanded the Guerrilla Platoon in 7 Column in 1943. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

The next job was to have the mules accept their saddler and loads, this was quite a job and with a few bruises received from their kicks. Each mule had a muleteer to look after it and it was surprising the bond that developed. Wingate was active, giving us talks on communications with our families with an Airmail letter sent each month to our next of kin, telling them we were alive and well or otherwise, we in turn were to ask our families to continue writing as we could have letters delivered along with our supplies.

There was no evacuation of the wounded or sick and if unable to keep up with the column, you would be left in a friendly village; all ranks had at least 25 silver rupees with them to pay for anything obtained. We were encouraged to grow beards; the idea was to save water, increase sleeping time and to help protect ourselves against mosquitoes.

Our tactics were to disrupt Japanese communications thus helping and advancing force, hit and run with no pitched battle unless totally unavoidable. Our faith in him (Wingate) was implicit, we being young thought ourselves fireproof and these talks usually ended with some biblical quotation. Various exercises were held to get used to loading and unloading the mules. After loading up we would often halt after half and hour to tighten the belt around their stomachs, this stopped the loads from slipping later on. It was essential to keep the mules load balanced.

The final training exercise was an attack on the Jhansi Railway Station 120 miles away from our camp. The station was defended by Indian troops. It was a dull and gruelling task, in that we had to attack from the North and cover over 180 miles in nine days. I was at the rear of our column and quite often found myself running to keep up as gaps appeared.

We had full packs and ammunition and for the last 20 miles we dumped these packs, this made us feel that we had wings on our feet. The attack was a success, but could not have been otherwise as the troops against us were almost new recruits.

We were now camped in Jhansi and there followed about two weeks of feverish preparation, all white underwear and apparel had to be died khaki, equipment checked and all deficiencies made up. We were issued with new and comfortable well studded boots. Rumours said (char wallah brand) that we would entrain for Assam the second or third week in January 1943. No one had any idea at the time about the nature of the fighting and the hardships that lay ahead. We did realise it was not going to be a cake walk, but were not unduly worried.

At this time a new frame for our packs was offered which I took. This allowed an air pocket between the pack and my back and reduced perspiration. Due to a shortage of officers and men the remnants of Column 6 was split up among the other three British Columns. The first to entrain were the mules and then ourselves, we travelled to a station north of Calcutta, transferred to a river steamer on the Brahmaputra River and then picked up the narrow gauge railway at Diburgarh. We reached Dimapur and then marched on foot to Imphal on the Manipur Road.

I did not se much of the Manipur Road because we marched along it at night, by day motor convoys were driving up and down and we would have caused chaos. We saw many vehicles in the valley that had failed to navigate the twists and turns in the road. We marched by stages, started at dusk, with a halt during the night for a brew up, then early the next morning meet our guides who led us into the next staging camp. We needed our blankets here because it was very cold as we were about 5000 feet up.

Daylight would sometimes give us some magnificent views, but at other times we would be in mist or rain. We marched in threes instead of the column snake and I am sure at times I was asleep as we marched. After nine days on the road covering about 120 miles we came to Imphal and pitched camp, made our own shelter and prepared for the visit of General Wavell.

The plan in which we were to assist did not materialise and it was not known if we would go in to Burma alone or the mission cancelled. In the end it was decided we should go it alone and instead of saluting the General, he saluted us. It was early February when we left camp all shaven and shorn and made our way to the Chindwin River, crossing at a place called Tonhe.

About this time the Burma Rifle contingent joined us. To cross the river we had rubber boats and RAF dinghies and were able to hire some native boats too. Those that could swim went over that way, the non-swimmers holding on to a mule or in boats. I do not remember a great deal about the crossing, but after all equipment, men and mules were over we formed up with our water bottles full, as ahead of us was a two day march, guided by a Burmese Forestry Officer (Major Hubert Castens) over a trail without water, which we hoped would bring us well behind any Jap positions.

We were carrying five days rations, with blankets, clothing change and groundsheet and in my case Bren gun pouches full of 20 round magazines for my Thomson sub machine gun. We also had a 50 round bandolier of 303 ammunition and three grenades held on a belt by their clips. Altogether we were carrying around 60-70 lbs. of kit.

During this section of the march we were accompanied by a host of chattering monkeys and kept awake by cicadas which made a noise like a circular saw. We eventually emerged from this trail well behind the Japanese outposts.The Japs knew we were in Burma, but spent their time looking for our lines of communication, not realising we were being supplied by air.

Seen below are photographs of two of the officers from the 2nd Burma Rifles, who commanded the Guerrilla Platoon in 7 Column in 1943. Please click on either image to bring it forward on the page.

After three more days we asked for our first ration drop in a paddy field, we lit our smoke fires and the RAF Officer with his wireless set contacted the pilot and directed him in. First came the parachutes with the food and anything breakable, then the free drops which was mostly fodder for the mules, but later on might be boots and other clothing replacements.

The free drops were quite dangerous as any direct hit could result in death. Following sequences rather blurred by time, I remember using a trail that crossed and re-crossed a stream. Our boots were covered in mud and sloshing about in the water, even at night we could dry our socks, but always kept our boots on even when sleeping.

We spent the next few days preparing to ambush Jap outposts, but mostly they never materialised, eventually we set up guard areas protecting the commandos as they went about their demolition business.

We were paired in twos, each man looking after the other in case one went missing. At meal times one would begin to prepare the meal while the other would search for fire wood and check the perimeter. A favourite meal, that is when we had plenty of rations, which was not often, was ‘shakapura pudding’. This consisted of four broken biscuits placed in water with added sugar, powdered milk and any of the fruit such as raisins mixed in. Quite filling for a while that was.

The planes used for our supply drops were Dakotas and Hudsons and I must express our gratitude to the pilots who came across Burma without fighter escort to supply us. We were sometimes confused by our maps; we would turn up in a location expecting to find a certain village, only to discover it had moved many years previously. This was due to the ‘slash and burn’ style of farming used by the Burmese, where they would clear an area for cultivation, exhaust this for several years, then simply move away to a new location.

Wild fowl were very common in this area and also Peacocks. Some of the lads used to put feathers in their bush hats to the dismay of the Burrifs (Burma Rifles), who thought this would bring exceedingly bad luck. Odd incidents would happen, such as the capture of a large snake, which the Burrifs would cut into steaks and cook. Ants, both brown and red and about half an inch long, would if disturbed cause very painful bites to your flesh. Leeches were a constant hazard, usually picked up when wading through a marsh or other swampy ground. If a leech was not removed with care it could leave a bite mark that very quickly might turn into a large jungle sore which look similar to ulcers.

One of our columns had been attacked by the Japanese during a supply drop on a paddy field. It was then decided to take future drops only in jungle clearings, but this proved difficult for the pilots and many parachutes would become caught up in tall trees and we were not able to retrieve them.

Japs had a routine of patrolling roads in vehicles around any area they thought we were in, so when we came to cross these we lined up and crossed all in on go. On one of these crossings, I, along with my section were guarding one end and just as the crossing began a Jap patrol came along. There was a firefight and despite coming off best two of my men were wounded.

We carried them on ponies for a while, but it became impossible to continue like this, so they were left in a village with our Burmese Roman Catholic Padre volunteering to look after them, at considerable danger to himself. Rice was about the only extra food we could obtain from the villages and our silver rupees were eagerly taken as the Japs had issued paper occupation currency, which was seemed totally worthless.

In one of the Kachin villages, where the people were extremely helpful, we saw a hut which had been occupied by a Roman Catholic priest. He had helped the locals with his medical knowledge but had been taken away by the Japanese; they kept his hut spotlessly clean ready for his return.

When in the Kachin Hills, the villagers would hide us in a near by secluded valley, where one night I was on guard duty, I heard a rustling coming from down the track, I prepared myself, only to find it was just a pig scavenging for food.

Most of our work seemed to be in the Indaw area, ambushing convoys and bridge blowing. Packs seemed to be heavier, we were losing weight and our belts had to be tightened, also lice were being found in our clothing. We had little chance to stop and wash as this left us too exposed. At water stops in small streams the best we could do was fill our bottles and let the mules drink what they could. We were always hungry as we never received our full ration requests, if we asked for ten days supply we were lucky to get five, they told us there was not enough planes to go around.

At times a mess tin of weak tea was all we had to sustain us and in desperation we shot one of our ponies, on another occasion we also shot a mule, but the meat was very tough. Bamboo shoots were cut for the mules to eat; at least this was something for them to chew on. We used to torture ourselves by talking about the meals we would order when we got back out. Food replaced sex in our minds, one of my men told me, “If Betty Grable was lying naked in front of me, I would still swap her for a plate of fish and chips.”

We next had to cross the Irrawaddy River which turned out to be a poor move as it placed us in a loop, like an inverted letter u, between the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. The Japs moved all the boats away from the east banks and began squeezing us up into the top of the loop. Water was scarce and we had to dig holes in river beds and allow water to seep through into them. Another time, after being without water for two days we came across an elephant wallow, we followed the elephant tracks hoping that no enemy were waiting for us at the other end. We took the muddy water from these tracks and boiled and sterilised it, the tea tasted like nectar.

It was in this area that we met a small herd of elephants, an old bull with wives and calves; we were in a river bed at this time with very high banks. The old bull did not want to retreat, but neither did we, so we fired a couple of shots over his head which persuaded him to retire.

We were now intensely hunted, the Japs increasing patrols and moving more troops into the area, all villages seemed to be on the look out for us and we felt that everyone was against us. During this period from one of our ration drops I received a letter from my mother, in it she told me about my brother, Stanley and how he had been billeted at home having secured a posting in Liverpool.

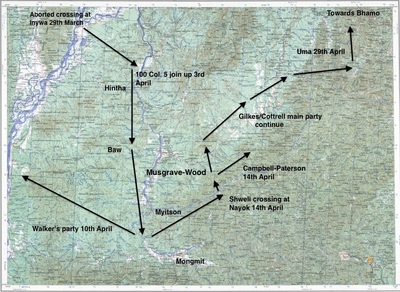

With the Japs pushing up into the loop we had to find a method of crossing the Shweli and after dodging their troops, often by retreating into the jungle, we found some bamboo rafts which enabled us to get to the east bank, still with our precious wireless sets. Shortly after this crossing Major Gilkes decided to split us to two parties, one to go with him and make for China, the other to try and return across the Irrawaddy and India led by Captain Whittaker. This second party was not seen or heard of again.

NB. It is highly likely that Fred was referring to the dispersal group led by Lieutenant Rex Walker, as no officer by the name of Whittaker took part on Operation Longcloth. The date of 7 Column's break up was approximately the 10th April. For more information about this dispersal group, please click on the following link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

Seen below are some more images in relation to the Fred's story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

The free drops were quite dangerous as any direct hit could result in death. Following sequences rather blurred by time, I remember using a trail that crossed and re-crossed a stream. Our boots were covered in mud and sloshing about in the water, even at night we could dry our socks, but always kept our boots on even when sleeping.

We spent the next few days preparing to ambush Jap outposts, but mostly they never materialised, eventually we set up guard areas protecting the commandos as they went about their demolition business.

We were paired in twos, each man looking after the other in case one went missing. At meal times one would begin to prepare the meal while the other would search for fire wood and check the perimeter. A favourite meal, that is when we had plenty of rations, which was not often, was ‘shakapura pudding’. This consisted of four broken biscuits placed in water with added sugar, powdered milk and any of the fruit such as raisins mixed in. Quite filling for a while that was.

The planes used for our supply drops were Dakotas and Hudsons and I must express our gratitude to the pilots who came across Burma without fighter escort to supply us. We were sometimes confused by our maps; we would turn up in a location expecting to find a certain village, only to discover it had moved many years previously. This was due to the ‘slash and burn’ style of farming used by the Burmese, where they would clear an area for cultivation, exhaust this for several years, then simply move away to a new location.

Wild fowl were very common in this area and also Peacocks. Some of the lads used to put feathers in their bush hats to the dismay of the Burrifs (Burma Rifles), who thought this would bring exceedingly bad luck. Odd incidents would happen, such as the capture of a large snake, which the Burrifs would cut into steaks and cook. Ants, both brown and red and about half an inch long, would if disturbed cause very painful bites to your flesh. Leeches were a constant hazard, usually picked up when wading through a marsh or other swampy ground. If a leech was not removed with care it could leave a bite mark that very quickly might turn into a large jungle sore which look similar to ulcers.

One of our columns had been attacked by the Japanese during a supply drop on a paddy field. It was then decided to take future drops only in jungle clearings, but this proved difficult for the pilots and many parachutes would become caught up in tall trees and we were not able to retrieve them.

Japs had a routine of patrolling roads in vehicles around any area they thought we were in, so when we came to cross these we lined up and crossed all in on go. On one of these crossings, I, along with my section were guarding one end and just as the crossing began a Jap patrol came along. There was a firefight and despite coming off best two of my men were wounded.

We carried them on ponies for a while, but it became impossible to continue like this, so they were left in a village with our Burmese Roman Catholic Padre volunteering to look after them, at considerable danger to himself. Rice was about the only extra food we could obtain from the villages and our silver rupees were eagerly taken as the Japs had issued paper occupation currency, which was seemed totally worthless.

In one of the Kachin villages, where the people were extremely helpful, we saw a hut which had been occupied by a Roman Catholic priest. He had helped the locals with his medical knowledge but had been taken away by the Japanese; they kept his hut spotlessly clean ready for his return.

When in the Kachin Hills, the villagers would hide us in a near by secluded valley, where one night I was on guard duty, I heard a rustling coming from down the track, I prepared myself, only to find it was just a pig scavenging for food.

Most of our work seemed to be in the Indaw area, ambushing convoys and bridge blowing. Packs seemed to be heavier, we were losing weight and our belts had to be tightened, also lice were being found in our clothing. We had little chance to stop and wash as this left us too exposed. At water stops in small streams the best we could do was fill our bottles and let the mules drink what they could. We were always hungry as we never received our full ration requests, if we asked for ten days supply we were lucky to get five, they told us there was not enough planes to go around.

At times a mess tin of weak tea was all we had to sustain us and in desperation we shot one of our ponies, on another occasion we also shot a mule, but the meat was very tough. Bamboo shoots were cut for the mules to eat; at least this was something for them to chew on. We used to torture ourselves by talking about the meals we would order when we got back out. Food replaced sex in our minds, one of my men told me, “If Betty Grable was lying naked in front of me, I would still swap her for a plate of fish and chips.”

We next had to cross the Irrawaddy River which turned out to be a poor move as it placed us in a loop, like an inverted letter u, between the Irrawaddy and Shweli Rivers. The Japs moved all the boats away from the east banks and began squeezing us up into the top of the loop. Water was scarce and we had to dig holes in river beds and allow water to seep through into them. Another time, after being without water for two days we came across an elephant wallow, we followed the elephant tracks hoping that no enemy were waiting for us at the other end. We took the muddy water from these tracks and boiled and sterilised it, the tea tasted like nectar.

It was in this area that we met a small herd of elephants, an old bull with wives and calves; we were in a river bed at this time with very high banks. The old bull did not want to retreat, but neither did we, so we fired a couple of shots over his head which persuaded him to retire.

We were now intensely hunted, the Japs increasing patrols and moving more troops into the area, all villages seemed to be on the look out for us and we felt that everyone was against us. During this period from one of our ration drops I received a letter from my mother, in it she told me about my brother, Stanley and how he had been billeted at home having secured a posting in Liverpool.

With the Japs pushing up into the loop we had to find a method of crossing the Shweli and after dodging their troops, often by retreating into the jungle, we found some bamboo rafts which enabled us to get to the east bank, still with our precious wireless sets. Shortly after this crossing Major Gilkes decided to split us to two parties, one to go with him and make for China, the other to try and return across the Irrawaddy and India led by Captain Whittaker. This second party was not seen or heard of again.

NB. It is highly likely that Fred was referring to the dispersal group led by Lieutenant Rex Walker, as no officer by the name of Whittaker took part on Operation Longcloth. The date of 7 Column's break up was approximately the 10th April. For more information about this dispersal group, please click on the following link: Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

Seen below are some more images in relation to the Fred's story. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

Fred's memoir continues:

A few days later we had stopped on a forest track for a midday halt. I was in charge of the rear platoon and took two men back down the path to act as sentries. One of our mules had lagged behind, so when I heard a mule harness jangling I assumed it was one of ours, but it was a Jap patrol and I feel the surprise experienced was mutual. I managed to fire a burst and then retreat back to where the two men were and take up a defensive position.

Much to my disgust the officer, a Dane named Petersen had moved off with the rest of the platoon, leaving me and the two other men to face the enemy patrol, however, after more shots were exchanged it became evident that I had wounded one and the others retired. After sorting ourselves out I found a bullet had partly shattered the butt of my Tommy gun and a dum dum bullet was found lodged in a shell dressing carried in my pack.

It took us two days to catch up the column and luckily we were able to pick up some rations left from the last supply drop. This was to be our last drop, as shortly after we lost the mule and wireless set and could no longer contact base. No more letters were sent to wives and families and Marjorie and Mother must have had a very anxious time.

The Japanese did not follow us into the jungle, they seemed reluctant to do so and this was our salvation as we escaped quite often by breaking up in to small parties and the reassembling further on. We now had to live off the land and rice was all we could obtain apart from smokers, who got some large green cheroots which smelt awful and made the men unwell. With this diet everyone became weaker and anything that was not needed was dumped, I remember the knife and fork in my pack seemingly becoming heavier and heavier and how light the pack felt after I threw them away.

Another item we needed was salt and this was both scarce and precious and was transported into the region by mule. It came in large pieces like cake and was coarse and dirty looking. Most villages sold us rice, sometimes cooked, but mostly raw. Again we used our silver rupees and were also given some Chinese bank notes. We tried every way to make the rice taste different; the most popular was to boil it dry and burning it.

We were now looking like a gang of ‘hill billies’ with our beards, long hair, filthy uniforms and boots practically falling off our feet. As far as I can remember we seemed to have a guide from one village to the next. Our eyes met a gruesome sight when we contacted the Chinese Army near a large area of scorched earth covered with unburied bodies. These were the result of Japanese atrocities.

When we felt safe we handed over to the Chinese all of our arms because they were short of weapons and then proceeded with nothing left to carry. I began falling behind and could not keep up with the column. I had developed some kind of fever and my body became allergic to starch so much so that I voided any rice immediately after eating it. I thought I was finished, but the villagers put me on a mule which carried me for three days until we reached a place with a Chinese doctor.

Somehow or other he managed to get me a small meal of meat and some kind of vegetable. I thought it was rabbit, but it was rat, even so it tasted delicious and helped me improve. Before we got to Paoshan we had to get across a fast flowing river, we met a boatman who took us across six at a time. Despite the strong current he skilfully used eddies to put us over safely.

The last hazard was a rope bridge so rickety we could only cross one at a time. My party of seventeen were now two days behind the column and when we reached Paoshan found that they had been taken by road to Yunnan. The lorries had been organised by the Military Attaché for that area and the column was due to be flown back to India from there.

On our arrival at Paoshan we had our clothes taken away and burned including my faithful bush hat. Next we had a bath where I saw the lice that had infested my body float away. Chinese uniforms were issued, far too small for us, but it was lovely feeling clean and not itching.

We had a haircut and shave, the sight of us all haggard and thin meant we had difficulty even recognising each other. The meal they gave us was some kind of meat, rice and vegetable. I ate some, but not the rice, I simply could not face it. We then had a four day wait before transport took us to Yunnan.

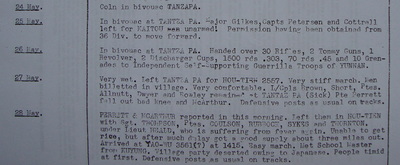

It transpired that the main party had only got to Yunnanyi, into which Dakotas were flying supplies to China. They would fly us back in small parties on their return journeys. Of the original 400 men of Column 7, only 141 made the return trip via Yunnanyi.

A few days later we had stopped on a forest track for a midday halt. I was in charge of the rear platoon and took two men back down the path to act as sentries. One of our mules had lagged behind, so when I heard a mule harness jangling I assumed it was one of ours, but it was a Jap patrol and I feel the surprise experienced was mutual. I managed to fire a burst and then retreat back to where the two men were and take up a defensive position.

Much to my disgust the officer, a Dane named Petersen had moved off with the rest of the platoon, leaving me and the two other men to face the enemy patrol, however, after more shots were exchanged it became evident that I had wounded one and the others retired. After sorting ourselves out I found a bullet had partly shattered the butt of my Tommy gun and a dum dum bullet was found lodged in a shell dressing carried in my pack.

It took us two days to catch up the column and luckily we were able to pick up some rations left from the last supply drop. This was to be our last drop, as shortly after we lost the mule and wireless set and could no longer contact base. No more letters were sent to wives and families and Marjorie and Mother must have had a very anxious time.

The Japanese did not follow us into the jungle, they seemed reluctant to do so and this was our salvation as we escaped quite often by breaking up in to small parties and the reassembling further on. We now had to live off the land and rice was all we could obtain apart from smokers, who got some large green cheroots which smelt awful and made the men unwell. With this diet everyone became weaker and anything that was not needed was dumped, I remember the knife and fork in my pack seemingly becoming heavier and heavier and how light the pack felt after I threw them away.

Another item we needed was salt and this was both scarce and precious and was transported into the region by mule. It came in large pieces like cake and was coarse and dirty looking. Most villages sold us rice, sometimes cooked, but mostly raw. Again we used our silver rupees and were also given some Chinese bank notes. We tried every way to make the rice taste different; the most popular was to boil it dry and burning it.

We were now looking like a gang of ‘hill billies’ with our beards, long hair, filthy uniforms and boots practically falling off our feet. As far as I can remember we seemed to have a guide from one village to the next. Our eyes met a gruesome sight when we contacted the Chinese Army near a large area of scorched earth covered with unburied bodies. These were the result of Japanese atrocities.

When we felt safe we handed over to the Chinese all of our arms because they were short of weapons and then proceeded with nothing left to carry. I began falling behind and could not keep up with the column. I had developed some kind of fever and my body became allergic to starch so much so that I voided any rice immediately after eating it. I thought I was finished, but the villagers put me on a mule which carried me for three days until we reached a place with a Chinese doctor.

Somehow or other he managed to get me a small meal of meat and some kind of vegetable. I thought it was rabbit, but it was rat, even so it tasted delicious and helped me improve. Before we got to Paoshan we had to get across a fast flowing river, we met a boatman who took us across six at a time. Despite the strong current he skilfully used eddies to put us over safely.

The last hazard was a rope bridge so rickety we could only cross one at a time. My party of seventeen were now two days behind the column and when we reached Paoshan found that they had been taken by road to Yunnan. The lorries had been organised by the Military Attaché for that area and the column was due to be flown back to India from there.

On our arrival at Paoshan we had our clothes taken away and burned including my faithful bush hat. Next we had a bath where I saw the lice that had infested my body float away. Chinese uniforms were issued, far too small for us, but it was lovely feeling clean and not itching.

We had a haircut and shave, the sight of us all haggard and thin meant we had difficulty even recognising each other. The meal they gave us was some kind of meat, rice and vegetable. I ate some, but not the rice, I simply could not face it. We then had a four day wait before transport took us to Yunnan.

It transpired that the main party had only got to Yunnanyi, into which Dakotas were flying supplies to China. They would fly us back in small parties on their return journeys. Of the original 400 men of Column 7, only 141 made the return trip via Yunnanyi.

My group stopped at a village at midday on the first day of travel and had obtained a meal of sorts from a roadside stall. Some needed the latrine and were shown to an area where pigs greedily ate anything you passed. Later we passed road workers breaking boulders by hand, once reduced to small stones women transported them in baskets upon their heads. It just looked like a procession of ants, there must have been hundreds of people working there and you could see the road developing. We were later informed that this was part of the Burma Road.

We spent that night at a Chinese Military Camp, next morning we were awakened by a dreadful caterwauling noise; it turned out to be Chinese funeral. We arrived in Yunnanyi early that afternoon and were soon on a plane to India. We lay on the bare metal floor, no first class seats and had a very bumpy trip caused by air pockets and down drafts over the mountain range called the ‘Hump’.

Our plane was based at Jorhat in Assam and on landing, was met by a RAF lorry which took us to hospital. Once in the ward and safe at last, I found that I could not walk from my bed to the latrine without assistance. It was suggested that Column 7 had marched over 1500 miles since it first entered Burma that February in 1943.

The Medical Officer asked us if there was any meal we would really fancy, we all requested bacon and eggs, but when it was brought to us we could not eat it as our stomachs had rebelled. We were put on a strict diet, the first meal being chicken boiled in milk.

My immediate concern was to get a message to Marjorie saying I was alive and well, knowing she would have been without news for at least two months. Four of my party caused the Medical Officer great concern and five days after our arrival they died of some kind of fever. I thought it ironic that they should have reached safety and then lost their lives. The RAF Station at Jorhat took care of the funerals and were very helpful.

NB. Several men were recorded as having died at Paoshan in July 1943. Among these were Ptes. Maurice Dwyer, Henry Walmsley, Alfred Short and Frank Rowley, plus Lance Corporal Robert Brown. It is possible that these were the men that Fred referred to as having died as a result of fever. However, only one of these men, Frank Rowley ended up being buried in an Indian War Cemetery after the war. Frank, from Gorton in Manchester was buried at Gauhati War Cemetery in Assam. For his CWGC details, please click on the link below: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2222460/ROWLEY,%20FRANK

We spent that night at a Chinese Military Camp, next morning we were awakened by a dreadful caterwauling noise; it turned out to be Chinese funeral. We arrived in Yunnanyi early that afternoon and were soon on a plane to India. We lay on the bare metal floor, no first class seats and had a very bumpy trip caused by air pockets and down drafts over the mountain range called the ‘Hump’.

Our plane was based at Jorhat in Assam and on landing, was met by a RAF lorry which took us to hospital. Once in the ward and safe at last, I found that I could not walk from my bed to the latrine without assistance. It was suggested that Column 7 had marched over 1500 miles since it first entered Burma that February in 1943.

The Medical Officer asked us if there was any meal we would really fancy, we all requested bacon and eggs, but when it was brought to us we could not eat it as our stomachs had rebelled. We were put on a strict diet, the first meal being chicken boiled in milk.

My immediate concern was to get a message to Marjorie saying I was alive and well, knowing she would have been without news for at least two months. Four of my party caused the Medical Officer great concern and five days after our arrival they died of some kind of fever. I thought it ironic that they should have reached safety and then lost their lives. The RAF Station at Jorhat took care of the funerals and were very helpful.

NB. Several men were recorded as having died at Paoshan in July 1943. Among these were Ptes. Maurice Dwyer, Henry Walmsley, Alfred Short and Frank Rowley, plus Lance Corporal Robert Brown. It is possible that these were the men that Fred referred to as having died as a result of fever. However, only one of these men, Frank Rowley ended up being buried in an Indian War Cemetery after the war. Frank, from Gorton in Manchester was buried at Gauhati War Cemetery in Assam. For his CWGC details, please click on the link below: http://www.cwgc.org/find-war-dead/casualty/2222460/ROWLEY,%20FRANK

Fred continues his story:

We did not realise the publicity our expedition had received, mainly I think because it must have been the first item of good news to come out of the Burma front and showed we could fight in the jungle just as well as the Japs. When the local tea planters heard that we were in hospital they came to invite us to their houses for an evening, the houses were wonderfully situated, surrounded by mountains and acres of tea plants.

As our health improved we were able to help the orderlies with other patients and as a result of not needing further medical attention, we were put into a bungalow in the grounds and looked after ourselves.

In India, instead of high pressure mains water, each building had a large tank of water nearby for use in case of fire. Our bungalow had one and as it was so hot, we asked the M.O. if we could swim. Permission was given, but this led to complaints from our Indian neighbours, who were unhappy with seeing naked men frolicking about.

During this time I had been writing to Marjorie and my mother, but their letters were still going to the unit back at Jhansi. After two months the M.O. thought it was time for us to go back to our original unit. We were happy to leave as we knew there would be plenty of mail waiting for us and also we were wanting to know what had happened to the other men from our column.

The RAF kitted us out the best they could, with solar topees instead of bush hats and we set off on the little Darjeeling Railway to Calcutta and then on to Jhansi. After leaving Calcutta we passed through an area of famine, everyone was starving. I learnt later that the rice harvest had failed, but the Indian Government had decided to ensure the Indian troops were fed at the expense of the civilian population.

The 13th King’s were under canvas at Jhansi and on arrival my first interest was the mail waiting for me, amongst which were six letters from people I did not know. These were from families of other men asking for information about their sons and husbands. I’m afraid I could not help them as we had all become so spread out during the operation. The reason this had happened was my mother had taken one of my letters down to the local Echo (newspaper) office and it had been published in the paper along with my photograph.

We were waiting at Jhansi for a move to Karachi and I was still unwell and having to cope with all the flies did not help me. Wingate had promised us a good posting and he kept his promise. Once at Karachi I was found a job as Sergeant in charge of Regimental Institutions. This covered all Regimental funds such as paying for sports equipment, barrack damages, compensation to locals and so on.

I had twelve different accounts, double cash entries, cash and bank columns and took money from entrance fees to dances or ‘housey housey’ sessions. Despite the excellent accommodation our time in the Burma jungle still caused illness, with men being admitted to hospital with fevers not yet diagnosed and despite the attention given to them some of these died. I suffered from swellings on my knees and ankles from which a horrible puss was extracted.

As time passed we became fitter and the queues for sick parade became less. We started having route marches, usually starting at 6am in the cool of the morning. During the first of these marches I was excused wearing webbing due to my ulcers, but I had to carry the rifles of other men who needed my help.

During early 1944 I was promoted to Company Quartermaster Sergeant at HQ Company, with about 350 men to look after for pay, rations and clothing etc. It was about this time that I went on leave to Quetta for a month, just a lazy holiday, no routine or parades. While I and another Sergeant were there we were invited to the homes of ex-King’s Officers who had retired there. They were keen to hear about our experiences in Burma and were very pleasant occasions.

At Karachi we had football and hockey pitches, tennis courts and some wonderful bathing beaches. We also went canoeing on Chinna Creek and hired local fishing boats to catch fish and then cook them over a charcoal fire. Often a Royal Marine Corvette would put in to harbour and we would invite the Petty Officers to our mess and in due course we visited them in theirs.

Our main duty was internal security and if there were any riots, we were called out to help the police, with out marksmen detailed to shoot any agitators. Another job we were asked to do was to clear the runways of the Aerodrome of sand, which occurred quite often during high winds. It was essential to keep this runway clear as it was a staging point for planes from England.

During the month of November 1944 we had a visit from Major Patey of the 1st Battalion King’s Liverpool, who was looking for men who took part in the 1943 expedition. All of us classed as A1 and under 30 were posted to the 1st King’s as reinforcements as the unit was preparing for another operation in 1946. So it was back to the jungle for me and about 40 others.

The unit was camped in the jungle along a stream with all the usual amenities, cook house, mess tents etc. My job was column CQMS and between training exercises I was encouraged to take the ponies out for rides and organise target shooting practice.

The rations were American K rations which were popular because of the exterior wrapper being made of wax and were useful for starting fires when conditions were wet. Replacement of kit was easy enough, although this upset the new Lieutenant Quartermaster who had not been involved with Special Forces before. I’m sure he would have had a heart attack if he knew that I had swapped a three inch mortar for three bags of rice from a West African unit!

Due to the rapid advance of the 14th Army in Burma our type of warfare was no longer needed and in February 1945 it was decided the 1st King’s would become paratroopers. The Commanding Officer expected everyone to volunteer, but when I learned that the time for service in India had been dropped from seven to three and a half years, I decided to refuse as I had been away long enough. This resulted in a series of insults, being called a coward, yellow and other such words, even the C.O. had me up to see if he could change my mind.

NB. The Ist King's duly became the 15th (King's) Battalion, the Parachute Regiment, (please see the link below) and were commanded initially by George Henry Astell, the former Burma Rifles Officer from Operation Longcloth now holding the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

www.paradata.org.uk/unit/15th-kings-parachute-battalion

Fred continues:

It was fortunate that the 1st King’s being a regular unit could not be disbanded like a ‘hostilities only’ unit. So, while the heroes went to Rawalpindi for paratroop training, we who were left were posted to Dehra Dun in the foothills of the Himalayas. We took over hutted accommodation just vacated by Italian POW’s and these were filthy.

The only decent hut was one used as a church which was beautifully decorated with murals. I, with a gang of ten men as advance party, had the job of cleaning enough huts to accommodate ‘us cowards’. I was senior CQMS and it fell to me to take over the Lieutenant Quartermaster’s job until one was posted to us, it was at this time that I enjoyed a life of luxury.

I was in charge of all the Indian attached troops, such as cooks, water carriers, sweepers etc. who had my bath ready, with my evening clothes laid out for me when I returned from the office. I could call on the cooks at any time for a meal and in the morning my daytime wear would be ready and my bed made after breakfast. I told my Marjorie about this and received a terse reply, telling me not to expect such treatment when I got home.

Later on, those potential paratroopers who failed the initial jump from a tethered balloon were automatically returned to unit and it gave me great delight to see them arrive back, including the RSM who had been so critical of me.

Dehra Dun was the reception area for the Gurkhas and it was great to see them training or on guard duty because they had starched shorts and trousers and would not lie down in case they creased. The next big occasion for us was an inspection of the unit by the G.O.C. India Command, General Auchinleck. For this the Quartermaster and I had to issue the men new kit just for the day and then, when the parade was over, take it all back and re-issue the old kit once more.

Seen below are some photographs of Fred at Karachi and Dehra Dun. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page.

We did not realise the publicity our expedition had received, mainly I think because it must have been the first item of good news to come out of the Burma front and showed we could fight in the jungle just as well as the Japs. When the local tea planters heard that we were in hospital they came to invite us to their houses for an evening, the houses were wonderfully situated, surrounded by mountains and acres of tea plants.

As our health improved we were able to help the orderlies with other patients and as a result of not needing further medical attention, we were put into a bungalow in the grounds and looked after ourselves.

In India, instead of high pressure mains water, each building had a large tank of water nearby for use in case of fire. Our bungalow had one and as it was so hot, we asked the M.O. if we could swim. Permission was given, but this led to complaints from our Indian neighbours, who were unhappy with seeing naked men frolicking about.

During this time I had been writing to Marjorie and my mother, but their letters were still going to the unit back at Jhansi. After two months the M.O. thought it was time for us to go back to our original unit. We were happy to leave as we knew there would be plenty of mail waiting for us and also we were wanting to know what had happened to the other men from our column.

The RAF kitted us out the best they could, with solar topees instead of bush hats and we set off on the little Darjeeling Railway to Calcutta and then on to Jhansi. After leaving Calcutta we passed through an area of famine, everyone was starving. I learnt later that the rice harvest had failed, but the Indian Government had decided to ensure the Indian troops were fed at the expense of the civilian population.