Sergeant-Major Bob Hobbs

Cap badge of 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

Cap badge of 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

Howard Robert Hobbs was born during the summer of 1922 in Edmonton, part of the North London Borough of Enfield. The son of working class parents, his father had been wounded twice during WW1; Bob, as he was known to his friends and family left school at the age of 14 and went to work for Cox & Co. a local electrical engineering firm, where he repaired car magnetos and dynamos.

Bob was called up into the Army in 1941 and served originally in the Royal Army Service Corps, but was included in a draft of men earmarked for overseas duty and was posted to the Indian Clerical Corps in 1942. Finding this work extremely dull, he volunteered for a locally advertised special mission. This turned out to be for Wingate's first expedition and Bob joined Chindit training at the Abchand Camp in the forests of Patharia in September 1942. His earliest memory of Brigadier Wingate was not a good one:

'Wingate came in to give us one of his talks. He asked everyone to hand in their cigarettes, adding that we would not need these where we were going. It was hardly a popular move on his part!'

Bob enjoyed the challenges thrown up by Wingate's theories on Long Range Penetration and excelled during his first few weeks at Patharia, showing a good understanding of jungle craft and building on his reputation as a top marksman. He was soon promoted to Sergeant and then posted over to the ranks of 2 Column, commanded by Major Arthur Emmett of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

Bob recalled the early weeks of training for Operation Longcloth:

'I loved the jungle. I was my own boss. I could almost please myself. The rations were good, we had two large tins of bully each week. I also liked the biscuits, but they had to be soaked in tea, to soften them up.'

Sergeant Hobbs continued to impress his seniors during training and was eventually promoted to Sergeant-Major, taking over the responsibility of Company discipline and guidance for the other NCO's in the column. He remembered:

'I wanted to get on in the Army. I had an older brother who stayed a Private the whole time. Perhaps I wanted to show him. My only set-back was an attack of Dengue Fever, which I think I caught because of my habit of going for a cooling swim in the lake near our training area. Anyway, I soon recovered.'

2 Column was composed predominately of Gurkha troops and was commanded by young officers recently commissioned into the Indian Army. Sgt-Major Hobbs took command of the British element of the column, ensuring that the standards set by these men were of the highest order:

'I spent my time at the back of this group, keeping everyone in line. They thought I was a right git. They all disliked me, but I had to be tough. Our march into Burma was very hard but I was extremely fit and never had any trouble with my feet. A chap in my group recommended soaking them in a solution of washing soda. I took his advice and never had problems with them.'

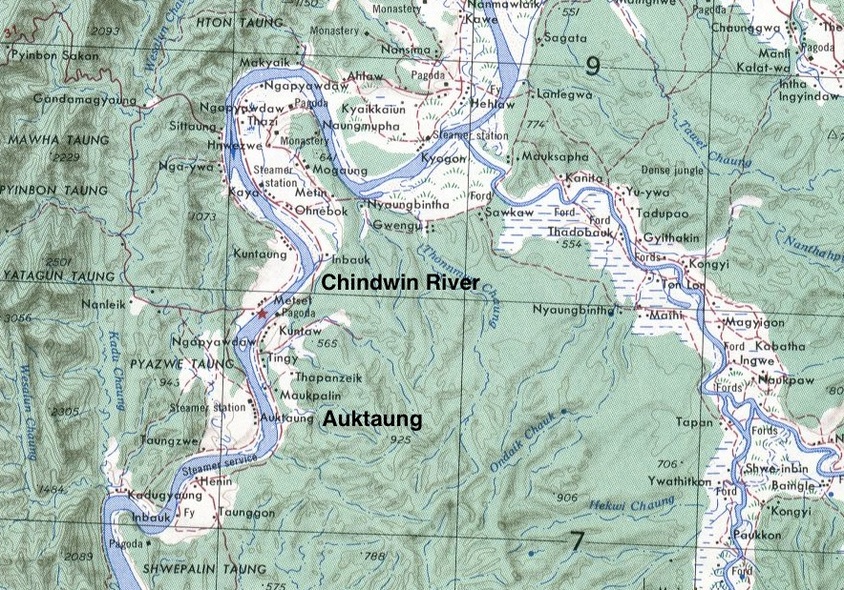

Major Emmett's unit formed part of Southern Group on Operation Longcloth, under the overall command of Lt-Colonel Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles. This section was used by Wingate as a decoy on the operation, the intention being for Southern Group to draw attention away from the main Chindit columns of Northern Group, as they crossed the Chindwin River and moved quickly east toward their targets along the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktaung. Their orders were to march toward their own prime target, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. This supplementary unit were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their objectives.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin; Major Dunlop (1 Column) was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst Bob Hobbs and 2 Column, along with Group HQ were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also now lost radio contact with each other. 2 Column and Group Head Quarters in the black of night, stumbled into the enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment. Here is how Lieutenant Ian MacHorton remembered that critical moment:

We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel.

Colonel Alexander managed to extract the majority of his Head Quarters from the chaos and devastation at Kyaikthin and decided to lead them away to the agreed rendezvous point a few miles further east. Major Emmett and a large part of his column had become separated from the main body and in the confusion and turmoil of the battle, turned east and returned to India. It is known, that the majority of the British Other Ranks from 2 Column, including the men of 142 Commando eventually joined up with Major Dunlop and continued on with the operation. It must be presumed that Sgt-Major Hobbs was with this group.

Bob was called up into the Army in 1941 and served originally in the Royal Army Service Corps, but was included in a draft of men earmarked for overseas duty and was posted to the Indian Clerical Corps in 1942. Finding this work extremely dull, he volunteered for a locally advertised special mission. This turned out to be for Wingate's first expedition and Bob joined Chindit training at the Abchand Camp in the forests of Patharia in September 1942. His earliest memory of Brigadier Wingate was not a good one:

'Wingate came in to give us one of his talks. He asked everyone to hand in their cigarettes, adding that we would not need these where we were going. It was hardly a popular move on his part!'

Bob enjoyed the challenges thrown up by Wingate's theories on Long Range Penetration and excelled during his first few weeks at Patharia, showing a good understanding of jungle craft and building on his reputation as a top marksman. He was soon promoted to Sergeant and then posted over to the ranks of 2 Column, commanded by Major Arthur Emmett of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

Bob recalled the early weeks of training for Operation Longcloth:

'I loved the jungle. I was my own boss. I could almost please myself. The rations were good, we had two large tins of bully each week. I also liked the biscuits, but they had to be soaked in tea, to soften them up.'

Sergeant Hobbs continued to impress his seniors during training and was eventually promoted to Sergeant-Major, taking over the responsibility of Company discipline and guidance for the other NCO's in the column. He remembered:

'I wanted to get on in the Army. I had an older brother who stayed a Private the whole time. Perhaps I wanted to show him. My only set-back was an attack of Dengue Fever, which I think I caught because of my habit of going for a cooling swim in the lake near our training area. Anyway, I soon recovered.'

2 Column was composed predominately of Gurkha troops and was commanded by young officers recently commissioned into the Indian Army. Sgt-Major Hobbs took command of the British element of the column, ensuring that the standards set by these men were of the highest order:

'I spent my time at the back of this group, keeping everyone in line. They thought I was a right git. They all disliked me, but I had to be tough. Our march into Burma was very hard but I was extremely fit and never had any trouble with my feet. A chap in my group recommended soaking them in a solution of washing soda. I took his advice and never had problems with them.'

Major Emmett's unit formed part of Southern Group on Operation Longcloth, under the overall command of Lt-Colonel Leigh Arbuthnot Alexander of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles. This section was used by Wingate as a decoy on the operation, the intention being for Southern Group to draw attention away from the main Chindit columns of Northern Group, as they crossed the Chindwin River and moved quickly east toward their targets along the Mandalay-Myitkhina railway.

Southern Group crossed the Chindwin on 15/16th February 1943 at a place called Auktaung. Their orders were to march toward their own prime target, the rail station at Kyaikthin. They marched openly along well known local trails and paths and also received a large supply drop from the air, which must have announced their presence in the area to the Japanese. The decoy group were accompanied at this time by a Company of Sikh Mountain Artillery and a section of Seaforth Highlanders. This supplementary unit were to create a further diversion for Wingate by attacking the town of Pantha, alerting the enemy to the possibility that there might well be a full-scale re-invasion taking place. To all intents and purposes these tactics succeeded and Northern Group did proceed unmolested toward their objectives.

On the 2nd March Columns 1 and 2 had reached the outskirts of Kyaikthin; Major Dunlop (1 Column) was given the order to blow up the railway bridge, whilst Bob Hobbs and 2 Column, along with Group HQ were to head on towards the rail station itself. What neither group realised was that the Japanese had by now closed in on the unsuspecting Chindits and lay in wait just a short way up the tracks. To make matters worse the two Gurkha columns had also now lost radio contact with each other. 2 Column and Group Head Quarters in the black of night, stumbled into the enemy ambush which straddled both sides of the railway line embankment. Here is how Lieutenant Ian MacHorton remembered that critical moment:

We shuffled to a halt as the guides probed forward. There came the sound of just one bang up front, then an inferno of noise engulfed the world around me. There came the high-pitched staccato scream of a machine gun, then overwhelmingly many others joined in, the crash and ping of rifle bullets, the banging of grenades as the battle reached a fearful crescendo. Men and mules were lying, twisted and contorted, twitching and writhing, others were still erect, stark in the moonlight, heaving and jerking in the midst of this chaos. Then a sinister scuffling noise made by men of all kinds in close combat. The close combat of bayonet and kukri, the fanatical, personal slaughter with blood-dripping cold steel.

Colonel Alexander managed to extract the majority of his Head Quarters from the chaos and devastation at Kyaikthin and decided to lead them away to the agreed rendezvous point a few miles further east. Major Emmett and a large part of his column had become separated from the main body and in the confusion and turmoil of the battle, turned east and returned to India. It is known, that the majority of the British Other Ranks from 2 Column, including the men of 142 Commando eventually joined up with Major Dunlop and continued on with the operation. It must be presumed that Sgt-Major Hobbs was with this group.

On March 24th 1943, the day that Wingate decided to order his men back to India, Major Dunlop's group were the furthest east of all the Chindit Columns. Their journey home lasted over five weeks and took many twists and turns, crossing at least three rivers as well as the heavily guarded Mandalay-Myitkhina Railway along the way. By the middle of April, concern about meeting the enemy began to take second place to the ever present sensations of hunger and thirst.

Bob Hobbs remembered:

'During the long march in over the Burmese hills we bought rice in villages. It took about a month to get used to jungle living, but we were quick to learn. For one thing, we found it best to under-cook this rice. When you eat under-cooked rice it swells up in your stomach and keeps you going for 24 hours or more, slowly releasing energy. I did try snake meat at one point, but it was no good.'

Sgt-Major Hobbs was a strict disciplinarian, always reminding his men to take salt and use the water-purifying tablets:

'It was important to use both water purification tablets. The first tablet 'killed all known germs', but you couldn't drink water in that state. The second tablet made it palatable. As for Mepacrine, I'd heard all the usual rumours but it didn't do me any harm. I went on to have three sons! We crossed and recrossed the many rivers. We always crossed in the hours of darkness. You'd die trying to cross in daylight. We were good at looking for and finding the enemy. I came under fire quite a few times. We often heard the Japanese call out in English at night. It was always obvious they were Japs. I killed at least three during an action in a goods yard near a railway station, the Gurkhas with me killed many more.'

On the return journey, Bob was put in charge of a group of fifteen men:

'We all grew accustomed to going hungry. I was determined to get them out and I always thought I would, but it took some believing at times. I brought all fifteen out alive. We carried an inflatable dinghy to cross the big rivers. Most dispersal groups had at least one good swimmer. Our worst problem at that time was the state of our boots. Mine just fell to bits after the Chindwin crossing. On reaching the west bank I threw the remains away and bound my feet in an old pair of shorts. I marched the rest of the way in rags.

I went from 13 stone to seven stone. All I thought about was getting home. In our starved condition, hundreds of miles behind enemy lines, the strain began to show. Eventually, I got to such a state that I became frightened of my own shadow. It was just lack of food. There were times at that stage when I began to doubt whether we would get out, yet we did. We all had private thoughts that kept us going. I used to dream of going to the chiropodist. This seemed to me to be the height of luxury.'

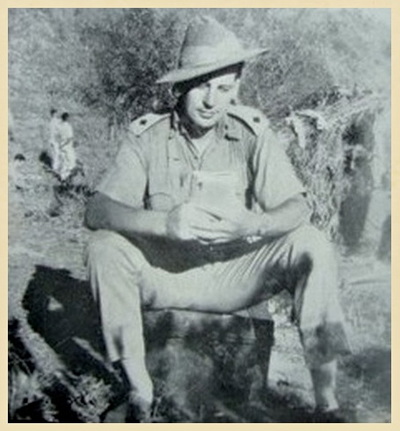

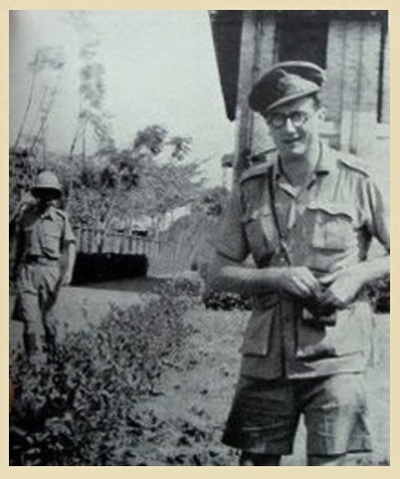

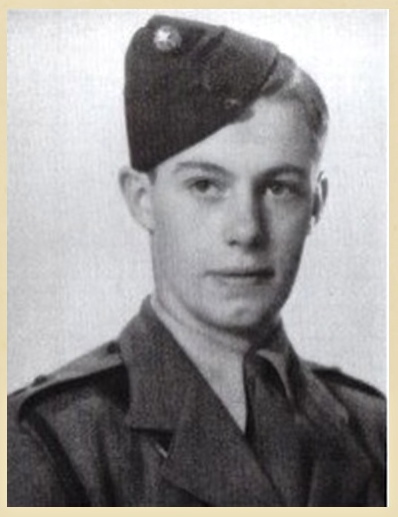

Seen below is a gallery of photographs of soldiers who were members of 2 Column on Operation Longcloth. Due to the small number of British personnel present in this column, it is highly likely that these men would have known Sgt-Major Hobbs. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. All the men featured in the gallery have more information written about them on these website pages. Please use the search engine in the top right hand corner of any page to search for their stories.

Bob Hobbs remembered:

'During the long march in over the Burmese hills we bought rice in villages. It took about a month to get used to jungle living, but we were quick to learn. For one thing, we found it best to under-cook this rice. When you eat under-cooked rice it swells up in your stomach and keeps you going for 24 hours or more, slowly releasing energy. I did try snake meat at one point, but it was no good.'

Sgt-Major Hobbs was a strict disciplinarian, always reminding his men to take salt and use the water-purifying tablets:

'It was important to use both water purification tablets. The first tablet 'killed all known germs', but you couldn't drink water in that state. The second tablet made it palatable. As for Mepacrine, I'd heard all the usual rumours but it didn't do me any harm. I went on to have three sons! We crossed and recrossed the many rivers. We always crossed in the hours of darkness. You'd die trying to cross in daylight. We were good at looking for and finding the enemy. I came under fire quite a few times. We often heard the Japanese call out in English at night. It was always obvious they were Japs. I killed at least three during an action in a goods yard near a railway station, the Gurkhas with me killed many more.'

On the return journey, Bob was put in charge of a group of fifteen men:

'We all grew accustomed to going hungry. I was determined to get them out and I always thought I would, but it took some believing at times. I brought all fifteen out alive. We carried an inflatable dinghy to cross the big rivers. Most dispersal groups had at least one good swimmer. Our worst problem at that time was the state of our boots. Mine just fell to bits after the Chindwin crossing. On reaching the west bank I threw the remains away and bound my feet in an old pair of shorts. I marched the rest of the way in rags.

I went from 13 stone to seven stone. All I thought about was getting home. In our starved condition, hundreds of miles behind enemy lines, the strain began to show. Eventually, I got to such a state that I became frightened of my own shadow. It was just lack of food. There were times at that stage when I began to doubt whether we would get out, yet we did. We all had private thoughts that kept us going. I used to dream of going to the chiropodist. This seemed to me to be the height of luxury.'

Seen below is a gallery of photographs of soldiers who were members of 2 Column on Operation Longcloth. Due to the small number of British personnel present in this column, it is highly likely that these men would have known Sgt-Major Hobbs. Please click on any image to bring it forward on the page. All the men featured in the gallery have more information written about them on these website pages. Please use the search engine in the top right hand corner of any page to search for their stories.

On his return to India, Bob Hobbs spent several weeks in hospital receiving treatment for his injured feet, severe malnutrition, malaria and dysentery. As soon as his health allowed, he was repatriated to the United Kingdom, but on arrival home was hospitalised once again.

Bob found it extremely difficult to settle back into civilian life. His first wife (Ann), sadly died just a few years after the war, leaving him with a young family to look after. He took up a job as a Milkman, working for United Dairies and met his second wife (Joy), at one of the firms Christmas parties.

Unfortunately and as with so many of the returning veterans from WW2, Bob's experiences in Burma continued to trouble him:

'I don't believe in talking about bad times. It is gone and finished. I have never mentioned my war service to my family.'

As mentioned earlier, Bob's column contained mostly Gurkha soldiers. His right forearm bears testimony to this fact, in the form of a large tattoo of crossed Kukri knives. When asked about the Japanese, Bob pulled no punches in his reply:

'Back then we said the only good one, was a dead one and I don't feel any different today.'

I would like to thank author Tony Redding, for allowing me to reproduce his conversations with Bob Hobbs, recorded in part for Tony's well-researched book, War in the Wilderness. In the Preface of the book, Tony recalls:

'Whilst talking to Sgt-Major Bob Hobbs of Westgate in Kent, I mentioned my own father's Chindit service. Bob asked me if he was still alive. When I replied that he wasn't, he paused, deep in thought, and then remarked: Your father may be gone, but he keeps very good company. This comment stayed with me throughout the preparation of my book. It was an inspiration.'

Copyright © Tony Redding and Steve Fogden, July 2016.

Bob found it extremely difficult to settle back into civilian life. His first wife (Ann), sadly died just a few years after the war, leaving him with a young family to look after. He took up a job as a Milkman, working for United Dairies and met his second wife (Joy), at one of the firms Christmas parties.

Unfortunately and as with so many of the returning veterans from WW2, Bob's experiences in Burma continued to trouble him:

'I don't believe in talking about bad times. It is gone and finished. I have never mentioned my war service to my family.'

As mentioned earlier, Bob's column contained mostly Gurkha soldiers. His right forearm bears testimony to this fact, in the form of a large tattoo of crossed Kukri knives. When asked about the Japanese, Bob pulled no punches in his reply:

'Back then we said the only good one, was a dead one and I don't feel any different today.'

I would like to thank author Tony Redding, for allowing me to reproduce his conversations with Bob Hobbs, recorded in part for Tony's well-researched book, War in the Wilderness. In the Preface of the book, Tony recalls:

'Whilst talking to Sgt-Major Bob Hobbs of Westgate in Kent, I mentioned my own father's Chindit service. Bob asked me if he was still alive. When I replied that he wasn't, he paused, deep in thought, and then remarked: Your father may be gone, but he keeps very good company. This comment stayed with me throughout the preparation of my book. It was an inspiration.'

Copyright © Tony Redding and Steve Fogden, July 2016.