'Almost, but not Quite'.

A personal account about his time with Mission 204 by Ted Stuart of No.5 Cdo. Courtesy of his son Neil Stuart and the Commando Veterans Association. To view the story in it's original form, please click on the link below:

http://www.commandoveterans.org/cdoGallery/v/units/5/ted+stuart.jpg.html

Below is an account written by Sergeant Edward Stuart of No. 5 Commando about his time in India during WW2. His story is not unique, but sits perfectly within the criteria for my website, as, had fate not intervened, Ted would have travelled into Burma in February 1943 as part of column 8. I have reproduced the narrative exactly as it was first presented.

Here is his story:

Almost, but not Quite!

It all began just after the monsoons were over. The year was 1942, and the place was the jungle of the Central Province of India. Not the ideal spot to experience your first monsoon but there was no choice. It was during the early days of the formation of General Wingate’s first expedition, when we were undergoing jungle training. At least that was the general idea, but that was upset by the weather. You can’t do a fat lot of training when the heavens are continually open. All we did, most of the time, was to stay in our tents and pretend that we were in Manchester. We eventually managed to move camp to some higher ground, which was just as well, otherwise we might have been known as the ‘Water Babes in uniform’.

By the way. This was not the sort of place that I had expected to be in when I, along with several others, had volunteered for a special mission. At that time I was a member of Number 4 Troop, 5 Commando, then stationed at Dartmouth, when the great adventure began. There were twelve volunteers from the unit, for this unknown mission, eleven of these coming from 4 Troop, including the Troop Captain and one of the subalterns. We eventually embarked at Liverpool, where we met the remainder of the force, which had been drawn from each of the Commandos still in the country. Then it was up to the Clyde to join a convoy, and it wasn’t long before 204 Military Mission set sail for an unknown destination. It was real ‘cloak and dagger’ stuff . . . sealed orders, only to be opened on the fourth day at sea. As can be imagined there was much varied speculation as to where we were bound for, none of which was anywhere near the mark. There was only one man on that ship who could have even hazarded a guess as to the actual revealed destination. A Lieutenant, who spoke Chinese and was there to try to teach us the language, Anyone who knows anything about the Chinese dialects would wonder what kind of idiot could dream up a scheme so hair-brained. However, for a while it helped to pass away the monotony of having very little to do except look at the other ships in the convoy, watch the destroyers keeping them in station, and of course playing housey, cards and crown and anchor.

Here is his story:

Almost, but not Quite!

It all began just after the monsoons were over. The year was 1942, and the place was the jungle of the Central Province of India. Not the ideal spot to experience your first monsoon but there was no choice. It was during the early days of the formation of General Wingate’s first expedition, when we were undergoing jungle training. At least that was the general idea, but that was upset by the weather. You can’t do a fat lot of training when the heavens are continually open. All we did, most of the time, was to stay in our tents and pretend that we were in Manchester. We eventually managed to move camp to some higher ground, which was just as well, otherwise we might have been known as the ‘Water Babes in uniform’.

By the way. This was not the sort of place that I had expected to be in when I, along with several others, had volunteered for a special mission. At that time I was a member of Number 4 Troop, 5 Commando, then stationed at Dartmouth, when the great adventure began. There were twelve volunteers from the unit, for this unknown mission, eleven of these coming from 4 Troop, including the Troop Captain and one of the subalterns. We eventually embarked at Liverpool, where we met the remainder of the force, which had been drawn from each of the Commandos still in the country. Then it was up to the Clyde to join a convoy, and it wasn’t long before 204 Military Mission set sail for an unknown destination. It was real ‘cloak and dagger’ stuff . . . sealed orders, only to be opened on the fourth day at sea. As can be imagined there was much varied speculation as to where we were bound for, none of which was anywhere near the mark. There was only one man on that ship who could have even hazarded a guess as to the actual revealed destination. A Lieutenant, who spoke Chinese and was there to try to teach us the language, Anyone who knows anything about the Chinese dialects would wonder what kind of idiot could dream up a scheme so hair-brained. However, for a while it helped to pass away the monotony of having very little to do except look at the other ships in the convoy, watch the destroyers keeping them in station, and of course playing housey, cards and crown and anchor.

Yes! That’s where we were bound for, China, to train the Chinese troops. However, the War office had reckoned without their counterparts in India, where we, after nine weeks on an overcrowded tub, disembarked at Bombay. From there to the delightful spot, so beloved of our troops . . . Deolali. We spent a few days there, then for an acclimatisation period, off to Jubbalpore Ridge, where we were fortunate enough to be attached to a battalion of the Green Howards, who, I must say, looked after us very well indeed. I can’t recall whether it was the 1st or the 2nd Battalion, but I certainly can recall the right royal treatment we had whilst we were with them. Although it was 1942, they were still living in peacetime conditions, which, of course, suited us down to the ground.

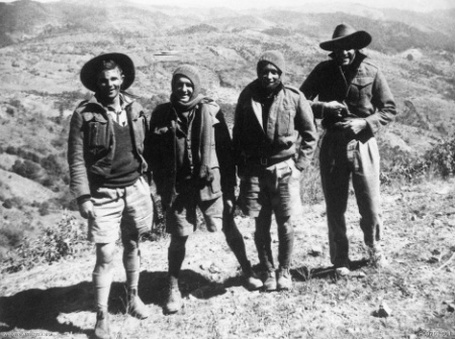

The photograph shown to the right is of four Australian members of 204 Military Mission, taken in the hills of Yunnan Province, China.

Lieutenant-Colonel Featherstonehaugh, the officer commanding the mission, went off to H.Q. Meerut, for further instructions as to our task. After a few days he returned with the news that nothing at all was known about any such mission and that he had been advised that we should return to the United Kingdom. This, he said, he had refused to do, stating that – ‘we had come to do a job and a job we would do!’ You can imagine how this announcement went down with the lads, who, by now, had come to realize that this was not the sort of mission that they had volunteered for. Off to Meerut went our officer commanding again, to sort things out, and that’s the last we saw of him. We did hear that he had been given a staff job but that was only hearsay, we really didn’t know what actually happened. The command of this unwanted and disillusioned mission, now known by their draft serial number, RZGHA, was assumed by Major Cooper-Keyes, and we continued on our attachment.

Meanwhile, lurking in the wings was Brigadier-General Orde Wingate, scouring the continent for likely candidates for the force he was building up. He must have regarded us as being sent from heaven. Over a hundred commando troops, trained in demolition, going spare. Before we knew it, we were out of our comfortable quarters in a civilised area and pitching our tents in some remote spot in the jungle of the Central Provinces of India. However, I have digressed, only I thought you might be interested in knowing how I got there in the first place.

So, there I was, the sergeant in charge of the commando section of number eight column (‘D’ Company of the King’s Liverpool Regiment). After the evening meal, I was always invited, by the company sergeant-major, to join the company commander and his senior non-commissioned officers, for an evening drink and chat. This of course, I appreciated and enjoyed, however, the habit of the evening visit was to prove of vital importance to me.

The photograph shown to the right is of four Australian members of 204 Military Mission, taken in the hills of Yunnan Province, China.

Lieutenant-Colonel Featherstonehaugh, the officer commanding the mission, went off to H.Q. Meerut, for further instructions as to our task. After a few days he returned with the news that nothing at all was known about any such mission and that he had been advised that we should return to the United Kingdom. This, he said, he had refused to do, stating that – ‘we had come to do a job and a job we would do!’ You can imagine how this announcement went down with the lads, who, by now, had come to realize that this was not the sort of mission that they had volunteered for. Off to Meerut went our officer commanding again, to sort things out, and that’s the last we saw of him. We did hear that he had been given a staff job but that was only hearsay, we really didn’t know what actually happened. The command of this unwanted and disillusioned mission, now known by their draft serial number, RZGHA, was assumed by Major Cooper-Keyes, and we continued on our attachment.

Meanwhile, lurking in the wings was Brigadier-General Orde Wingate, scouring the continent for likely candidates for the force he was building up. He must have regarded us as being sent from heaven. Over a hundred commando troops, trained in demolition, going spare. Before we knew it, we were out of our comfortable quarters in a civilised area and pitching our tents in some remote spot in the jungle of the Central Provinces of India. However, I have digressed, only I thought you might be interested in knowing how I got there in the first place.

So, there I was, the sergeant in charge of the commando section of number eight column (‘D’ Company of the King’s Liverpool Regiment). After the evening meal, I was always invited, by the company sergeant-major, to join the company commander and his senior non-commissioned officers, for an evening drink and chat. This of course, I appreciated and enjoyed, however, the habit of the evening visit was to prove of vital importance to me.

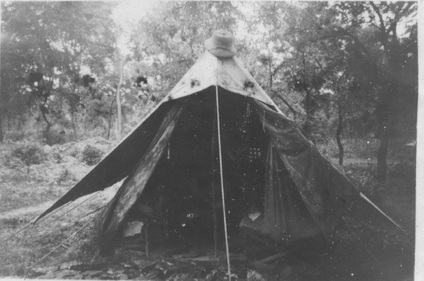

From out of the blue, the China project reared it’s ugly head once more and, with very little notice the whole of my section was whipped away, leaving me the sole occupant of a line of tents. (Pictured left, is an example of such a tent, Captain Tommy Roberts's tent in the Ramna Forest during Chindit training. Image courtesy and copyright of the Roberts family. Please click on the image to enlarge). Shortly after their departure, I went down with an attack of malaria, but there was nobody around to know it, I lay on my charpoy (bed), in a raging fever, unable to move or call out and, of course there was no one to know of my plight. It was only owing to the fact that I had missed two consecutive evening sessions that the sergeant-major suspected that there was something amiss, and sent one of the sergeants to see what was wrong.

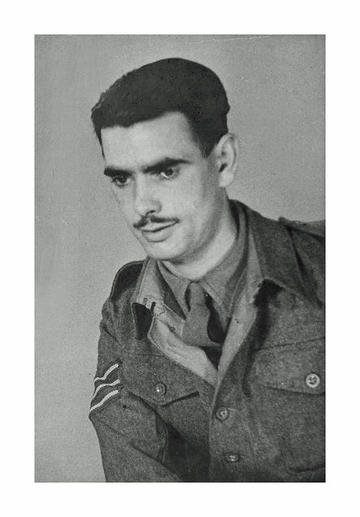

My next recollection was of being in our jungle ‘hospital’, which was situated in a rest house. These were bungalow type buildings, usually consisting of two or three rooms and cooking facilities. Charpoys were provided for sleeping in, but normally furnishing was sparse. As the name implies, they were intended for use by travellers to rest up in, the jungle not being the ideal place for night travel. There being a rest house near where the force was camped, it was taken over and used as a makeshift hospital, under the charge of the brigade medical officer, Captain W.S. Aird, RAMC. Bill Aird was one of the finest men I have ever had the privilege of knowing, a real gentleman, and a damned good and caring doctor.

By the time I was discharged, the force had moved to a place called Sagor, so, complete with all my kit, I set off to rejoin my unit, still mustering under the name of RZGHA. They even had a flag with the name on it and no doubt hold the record for keeping their draft serial number the longest. It was a ruling of General Wingate that anyone contracting recurring disease would have to leave the force. I was transported to the nearest railway station, or a more apt description would be that I was ‘dumped in a dump’, which went under that name of a station. There was no waiting room or refreshment room, and there was no European food to be had anywhere. The only refreshment to be had was from a native stall which sold hot and very sweet char (tea).

The train to Sagor wasn’t due for several hours and all that I could do was to moon around this desolate spot, drinking this ghastly, sickly concoction. As time passed, I began to feel very tired and my stomach was upset. I sat on a seat on the platform and, almost immediately fell into a heavy sleep. I awoke with a start to see the train standing at the platform, grabbing what kit I could carry, I ran and put it in the nearest carriage, rushing back to collect the rest of it, turning around I found to my horror and consternation, that the train was moving off. Although there were plenty of people on the platform, not one had offered me any assistance, and such railway officials that might have been were conspicuous by their absence. All that I could do was to stand holding half of my kit in my hands, staring in disbelief, as the train bearing the other half, disappeared into the distance.

I found the ‘Station master’ and explained what had happened, adding some strong comments, into which some strong epithets had been easily absorbed. To give him his due he was profusely apologetic about there being no staff to help me, promising to arrange to have the unaccompanied part of my belongings taken off the train at Sagor. As there wasn’t another train going in that direction until the next day, there was nothing for it but to find some alternative way of reaching my destination. This entailed humping my remaining gear five miles to a supply point, where I was fortunate to get a lift to Sagor on a supply truck. By this time I was feeling really ill and I must have looked it. As soon as my mates saw me, they whipped me down to the medical tent, so twenty-four hours after being discharged from one hospital, I found myself being admitted into another. My stomach upset turned out to be . . . dysentery!

Treatment in this hospital consisted of near starvation and liberal injections of emetine, given with much gusto, by an Anglo-Indian medico. This chap would have given Eric Bristow a close game in a darts match. He would ping the needle into one arm, twist it to the position that he wanted it, and then shoot the damned stuff into you. Truly an unforgettable character. However, I managed to survive both the darts and the starvation.

Again discharged from hospital, I was given a couple of weeks sick leave. At my request, arrangements were made for me to spend this with the Green Howards at Jubbalpore. An obvious choice really as I had made quite a number of friends whilst we were attached to them, and as most of them came from my part of England, so there was no trouble with my dialect. I must say I couldn’t have had better treatment if I had been royalty. They really went out of their way to make sure that I enjoyed myself and I have never forgotten their kindness. I recall having a photograph taken whilst I was there. I took one look at the prints and immediately tore them up. Talk about a walking skeleton! I could have easily had a star part in a freak show, eight stone of skin and bones. If I had turned sideways I couldn’t have been seen at all.

Rejoining the unit, which, by this time had moved back to a jungle camp, I had, as usual, to report to the medical officer. Captain Aird was pleased to see me looking so much better and, with typical Scottish hospitality insisted that we celebrate my return with a drink. Not having any of the usual beverages used on these occasions, we sat at a table in the medical tent, somewhere in the middle of the jungle, toasting each other in iron tonic, served up in Bakelite grenade caps. Shortly after that, I was posted away from the force and never saw Bill Aird again; he was a wonderful and much respected gentleman.

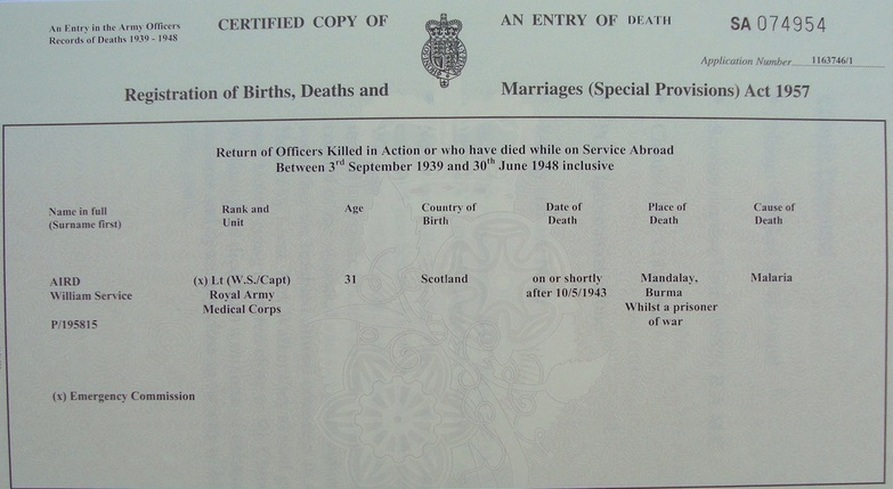

William Service Aird had been the Chindit HQ medic in 1942 and was stationed primarily with 142 Coy. Bernard Fergusson saw the doctor's obvious qualities and stole him away to column 5. During the operation in Burma William was separated from his column and later formed part of Lieutenant Rex Walker's dispersal party. The majority of this group were taken prisoner in April 1943, Captain Aird died from the effects of exhaustion and malaria near the city of Mandalay, as the Chindit POW's were being transported down to Rangoon by train. Shown below is a copy of his Army Death Certificate.

To read the full story of Rex Walker's dispersal group, please click on the link below:

Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

My next recollection was of being in our jungle ‘hospital’, which was situated in a rest house. These were bungalow type buildings, usually consisting of two or three rooms and cooking facilities. Charpoys were provided for sleeping in, but normally furnishing was sparse. As the name implies, they were intended for use by travellers to rest up in, the jungle not being the ideal place for night travel. There being a rest house near where the force was camped, it was taken over and used as a makeshift hospital, under the charge of the brigade medical officer, Captain W.S. Aird, RAMC. Bill Aird was one of the finest men I have ever had the privilege of knowing, a real gentleman, and a damned good and caring doctor.

By the time I was discharged, the force had moved to a place called Sagor, so, complete with all my kit, I set off to rejoin my unit, still mustering under the name of RZGHA. They even had a flag with the name on it and no doubt hold the record for keeping their draft serial number the longest. It was a ruling of General Wingate that anyone contracting recurring disease would have to leave the force. I was transported to the nearest railway station, or a more apt description would be that I was ‘dumped in a dump’, which went under that name of a station. There was no waiting room or refreshment room, and there was no European food to be had anywhere. The only refreshment to be had was from a native stall which sold hot and very sweet char (tea).

The train to Sagor wasn’t due for several hours and all that I could do was to moon around this desolate spot, drinking this ghastly, sickly concoction. As time passed, I began to feel very tired and my stomach was upset. I sat on a seat on the platform and, almost immediately fell into a heavy sleep. I awoke with a start to see the train standing at the platform, grabbing what kit I could carry, I ran and put it in the nearest carriage, rushing back to collect the rest of it, turning around I found to my horror and consternation, that the train was moving off. Although there were plenty of people on the platform, not one had offered me any assistance, and such railway officials that might have been were conspicuous by their absence. All that I could do was to stand holding half of my kit in my hands, staring in disbelief, as the train bearing the other half, disappeared into the distance.

I found the ‘Station master’ and explained what had happened, adding some strong comments, into which some strong epithets had been easily absorbed. To give him his due he was profusely apologetic about there being no staff to help me, promising to arrange to have the unaccompanied part of my belongings taken off the train at Sagor. As there wasn’t another train going in that direction until the next day, there was nothing for it but to find some alternative way of reaching my destination. This entailed humping my remaining gear five miles to a supply point, where I was fortunate to get a lift to Sagor on a supply truck. By this time I was feeling really ill and I must have looked it. As soon as my mates saw me, they whipped me down to the medical tent, so twenty-four hours after being discharged from one hospital, I found myself being admitted into another. My stomach upset turned out to be . . . dysentery!

Treatment in this hospital consisted of near starvation and liberal injections of emetine, given with much gusto, by an Anglo-Indian medico. This chap would have given Eric Bristow a close game in a darts match. He would ping the needle into one arm, twist it to the position that he wanted it, and then shoot the damned stuff into you. Truly an unforgettable character. However, I managed to survive both the darts and the starvation.

Again discharged from hospital, I was given a couple of weeks sick leave. At my request, arrangements were made for me to spend this with the Green Howards at Jubbalpore. An obvious choice really as I had made quite a number of friends whilst we were attached to them, and as most of them came from my part of England, so there was no trouble with my dialect. I must say I couldn’t have had better treatment if I had been royalty. They really went out of their way to make sure that I enjoyed myself and I have never forgotten their kindness. I recall having a photograph taken whilst I was there. I took one look at the prints and immediately tore them up. Talk about a walking skeleton! I could have easily had a star part in a freak show, eight stone of skin and bones. If I had turned sideways I couldn’t have been seen at all.

Rejoining the unit, which, by this time had moved back to a jungle camp, I had, as usual, to report to the medical officer. Captain Aird was pleased to see me looking so much better and, with typical Scottish hospitality insisted that we celebrate my return with a drink. Not having any of the usual beverages used on these occasions, we sat at a table in the medical tent, somewhere in the middle of the jungle, toasting each other in iron tonic, served up in Bakelite grenade caps. Shortly after that, I was posted away from the force and never saw Bill Aird again; he was a wonderful and much respected gentleman.

William Service Aird had been the Chindit HQ medic in 1942 and was stationed primarily with 142 Coy. Bernard Fergusson saw the doctor's obvious qualities and stole him away to column 5. During the operation in Burma William was separated from his column and later formed part of Lieutenant Rex Walker's dispersal party. The majority of this group were taken prisoner in April 1943, Captain Aird died from the effects of exhaustion and malaria near the city of Mandalay, as the Chindit POW's were being transported down to Rangoon by train. Shown below is a copy of his Army Death Certificate.

To read the full story of Rex Walker's dispersal group, please click on the link below:

Rex Walker's Dispersal Group 4

Ted now continues his story:

I was moved around the country, Bombay, Karachi and various minor places, eventually finishing up in Nasik Road reinforcement camp, the least said about which, the better. I went on leave to Calcutta from there; this was a two day train journey. A train journey in India could last for days, so this was something of a short hop. On this particular trip an unforgettable and entirely unexpected event was experienced. The event can be remembered but I’m afraid that the name of the place where it happened cannot. However, it was Christmas Day when we pulled into a fairly large station, where we were surprised to see quite a number of European ladies on the platform. They were calling to us to get off the train, which we dutifully did. We were then shepherded into a large, Christmas festooned hut, and sat down to a lovely Christmas dinner, with all the trimmings, including a bottle of beer and a small present. Apparently, these good ladies were meeting every train and ensuring that all our lads on it, had their Christmas dinner. This, of course, was right out of the blue, but I’m sure that everyone who experienced this entirely unexpected act of kindness will remember it with much appreciation.

The stay in Calcutta was quite pleasant with the exception of a rather upsetting incident. We were staying at the racecourse, where one of the stands was being used as sleeping quarters. We slept on the veranda of the stand and were provided with a charpoy and a chair and, of course, bedding, the chair was used to fold or hang our uniforms on. Well, we didn’t expect wardrobes, not on a racecourse. One morning we woke to find our uniforms weren’t there. These we found one floor below, all piled up in a big heap. I recovered mine only to find, as everyone else did, that all the money and personal documents were missing. It transpired that this was the work of two deserters, one from the Army, the other from the RAF, who would quietly go around the various billets and camps, when the occupants were asleep, take the clothing, nip off to some remote spot, and there go through the pockets at their leisure. This time, however, they had been caught before they could make their getaway. Our documents were returned to us, the money being retained by the military police who, whilst acknowledging possession, stated that it would be required to be produced as evidence at the forthcoming court-martial. As a point of interest – Oh, you’ve guessed. You’re dead right; I never did get it back, despite official requests. The reply was always the same, still required as evidence at the forthcoming court-martial. I reckoned they got so attached to it that they couldn’t bear to part with it.

After about a week, I was recalled from my leave, no reason being given but I surmised that a posting had come through for me. As this was what I wanted, I didn’t feel so bad at having to forgo the remainder of my leave. Besides which, I had no money. Arriving back at the reinforcement camp, I found to my delight, that I had been posted and, furthermore, the posting was the very one I wanted. It was to the Eastern Warfare School at Lake Karakvasla, which was about thirteen kilometres from Poona. I was particularly pleased because I would be rejoining my old troop skipper, Captain Bill Manford, who, somehow, had got to know that I was at Nasik Road camp and had arranged my posting, which, I was to discover, he had done for a couple more of the old troop.

It was another long journey and once again I underwent the, now familiar, feeling that all was not well with my stomach. By the time we reached Poona Station, in the late evening, I was feeling really ghastly and very tired. Fortunately I was met at the station by some of the boys from the school who, observing the state that I was in, whisked me away to the camp, gave me a warm drink and put me to bed.

Early next morning I received a visit from the School medical officer, Captain R.S. McCormack, an Irishman with a very blunt manner. A man who didn’t suffer fools gladly, regardless of their rank, but who had a marvellous sense of humour. He was accompanied by his sergeant, George Varley, a Yorkshireman who could vie with his Captain for humour. Aged about forty, a non-smoker and teetotal, George had in his younger days played rugby league for Castleford and county cricket for Northants if my memory serves me right. We hit it off from the start and soon became good friends. Captain McCormack began to give me a thorough examination, eventually straightening up.

“You know what you’ve got, don’t you?” he said.

“Yes sir,” I knew only too well, “dysentery.”

“Dead right my lad,” he confirmed, turning to George, “Get him to hospital as quickly as you can Sergeant. I’ll ring them and tell them that you’re on your way.” He stayed chatting to me until the transport arrived.

Before long we had arrived at Number 3 British Military Hospital, Poona, and I was soon tucked up in bed, feeling more than a little under the weather and extremely sorry for myself. Soon, dysentery working the way it does, I felt the need to go to the toilet. There being no nursing staff around at the time, I clambered out of bed, wobbled my way out on to the veranda, then down to the toilets which were at the far end. Whilst I was engaged in the process of complying with the demands of my body, unwelcome as they were. I wondered what on earth could have caused all the commotion that I could hear going on outside. It wasn’t long before I found out the reason, for as soon as I appeared on the veranda I was seized by two orderlies and carted off back to my bed, with a relieved looking Ward Sister in attendance. Seeing me settled safely in bed she proceeded to give me a rare ticking off, most of which I can’t recall but I do remember how she finished. . . .

“On no account whatever,” she lectured, “are you to get out of bed again. If you require the toilet, ask, and the orderly will get you a bed-pan and bottle.” There didn’t seem to be much point in saying that there was no staff around that I could ask at the time. What I didn’t realize at the time was just how seriously ill I was, and it wasn’t until some weeks after that this was brought home to me. I felt rough, of course but this I put down to tiredness as well as stomach trouble.

As I say it was some weeks before the real extent of my condition was revealed to me. I was then, happily, well on the way to recovery, able to sit up, smoke my head off and what’s more . . . go to the toilet on my own. My good friend the Ward Sister was due to return to the United Kingdom and the newly arrived Sister was being introduced to each case by the Medical Officer. They eventually got to my bed, where I was sitting up, looking a picture of health. I can’t remember the M.O.’s name, but I can still picture him. He was a Captain, about thirty years of age, slightly built, with dark hair, a small moustache, and he wore spectacles. Not much given to humour, but now he beamed at me.

“Now, Sister,” he said, “this is our proudest case. We had actually given this chap up at one time.” I felt my jaw drop. “Pardon?” I spluttered.

“Oh yes!” he continued “Naturally we didn’t tell you but you certainly gave use a fright. It was a bit touch and go for a while.” They moved on.

As I pondered this remarkable piece of news, various happenings, which at the time of my admittance had puzzled me, began to make sense. The extreme quietness of the ward, people talking in whispers mostly. My Commanding officer Colonel Ingham-Clarke, coming in to pay a visit almost every day. The visits from the lads from the unit most of whom I didn’t know and had never previously met. I could clearly recall the Medical officer, Matron, Ward Sister and the hospital Sergeant-Cook, all grouped around my bed, each trying to persuade me to eat, tempting me with all sorts of delicacies, but I didn’t want anything, except to be left alone. One of the terrible effects of dysentery is that you can easily lose the will to live and I had seen this happen. They managed to keep me alive but I must admit that I didn’t know much about how they did it. However, I lived and was eventually discharged from the hospital and returned to my unit, with whom I had spent only one night. Here I spent several months recuperating at one of our camps, Fort Singah, an old Maharati Fort some 4,500 feet above sea level, until, due to the efforts of my Commanding Officer, I was repatriated back to England.

I have had quite a number of upsets with the old tummy because it will never be quite right. However I am still alive and into my seventies now, but had it not been for the skill of the R.A.M.C. doctors and staff; the care and devotion of the officers and other ranks of the Queen Alexandra’s Army Nursing Corps; and people like Bill Aird and ‘Doc’ McCormack, it might not have been ‘almost, but not quite’.

My heartfelt thanks go to Neil Stuart for allowing me to reproduce his father's memoir on this website. Many thanks must also go to Pete Rogers from the CVA for helping me get permission in the first instance.

Copyright © Neil Stuart and Steve Fogden 2012.

I was moved around the country, Bombay, Karachi and various minor places, eventually finishing up in Nasik Road reinforcement camp, the least said about which, the better. I went on leave to Calcutta from there; this was a two day train journey. A train journey in India could last for days, so this was something of a short hop. On this particular trip an unforgettable and entirely unexpected event was experienced. The event can be remembered but I’m afraid that the name of the place where it happened cannot. However, it was Christmas Day when we pulled into a fairly large station, where we were surprised to see quite a number of European ladies on the platform. They were calling to us to get off the train, which we dutifully did. We were then shepherded into a large, Christmas festooned hut, and sat down to a lovely Christmas dinner, with all the trimmings, including a bottle of beer and a small present. Apparently, these good ladies were meeting every train and ensuring that all our lads on it, had their Christmas dinner. This, of course, was right out of the blue, but I’m sure that everyone who experienced this entirely unexpected act of kindness will remember it with much appreciation.

The stay in Calcutta was quite pleasant with the exception of a rather upsetting incident. We were staying at the racecourse, where one of the stands was being used as sleeping quarters. We slept on the veranda of the stand and were provided with a charpoy and a chair and, of course, bedding, the chair was used to fold or hang our uniforms on. Well, we didn’t expect wardrobes, not on a racecourse. One morning we woke to find our uniforms weren’t there. These we found one floor below, all piled up in a big heap. I recovered mine only to find, as everyone else did, that all the money and personal documents were missing. It transpired that this was the work of two deserters, one from the Army, the other from the RAF, who would quietly go around the various billets and camps, when the occupants were asleep, take the clothing, nip off to some remote spot, and there go through the pockets at their leisure. This time, however, they had been caught before they could make their getaway. Our documents were returned to us, the money being retained by the military police who, whilst acknowledging possession, stated that it would be required to be produced as evidence at the forthcoming court-martial. As a point of interest – Oh, you’ve guessed. You’re dead right; I never did get it back, despite official requests. The reply was always the same, still required as evidence at the forthcoming court-martial. I reckoned they got so attached to it that they couldn’t bear to part with it.

After about a week, I was recalled from my leave, no reason being given but I surmised that a posting had come through for me. As this was what I wanted, I didn’t feel so bad at having to forgo the remainder of my leave. Besides which, I had no money. Arriving back at the reinforcement camp, I found to my delight, that I had been posted and, furthermore, the posting was the very one I wanted. It was to the Eastern Warfare School at Lake Karakvasla, which was about thirteen kilometres from Poona. I was particularly pleased because I would be rejoining my old troop skipper, Captain Bill Manford, who, somehow, had got to know that I was at Nasik Road camp and had arranged my posting, which, I was to discover, he had done for a couple more of the old troop.

It was another long journey and once again I underwent the, now familiar, feeling that all was not well with my stomach. By the time we reached Poona Station, in the late evening, I was feeling really ghastly and very tired. Fortunately I was met at the station by some of the boys from the school who, observing the state that I was in, whisked me away to the camp, gave me a warm drink and put me to bed.

Early next morning I received a visit from the School medical officer, Captain R.S. McCormack, an Irishman with a very blunt manner. A man who didn’t suffer fools gladly, regardless of their rank, but who had a marvellous sense of humour. He was accompanied by his sergeant, George Varley, a Yorkshireman who could vie with his Captain for humour. Aged about forty, a non-smoker and teetotal, George had in his younger days played rugby league for Castleford and county cricket for Northants if my memory serves me right. We hit it off from the start and soon became good friends. Captain McCormack began to give me a thorough examination, eventually straightening up.

“You know what you’ve got, don’t you?” he said.

“Yes sir,” I knew only too well, “dysentery.”

“Dead right my lad,” he confirmed, turning to George, “Get him to hospital as quickly as you can Sergeant. I’ll ring them and tell them that you’re on your way.” He stayed chatting to me until the transport arrived.

Before long we had arrived at Number 3 British Military Hospital, Poona, and I was soon tucked up in bed, feeling more than a little under the weather and extremely sorry for myself. Soon, dysentery working the way it does, I felt the need to go to the toilet. There being no nursing staff around at the time, I clambered out of bed, wobbled my way out on to the veranda, then down to the toilets which were at the far end. Whilst I was engaged in the process of complying with the demands of my body, unwelcome as they were. I wondered what on earth could have caused all the commotion that I could hear going on outside. It wasn’t long before I found out the reason, for as soon as I appeared on the veranda I was seized by two orderlies and carted off back to my bed, with a relieved looking Ward Sister in attendance. Seeing me settled safely in bed she proceeded to give me a rare ticking off, most of which I can’t recall but I do remember how she finished. . . .

“On no account whatever,” she lectured, “are you to get out of bed again. If you require the toilet, ask, and the orderly will get you a bed-pan and bottle.” There didn’t seem to be much point in saying that there was no staff around that I could ask at the time. What I didn’t realize at the time was just how seriously ill I was, and it wasn’t until some weeks after that this was brought home to me. I felt rough, of course but this I put down to tiredness as well as stomach trouble.

As I say it was some weeks before the real extent of my condition was revealed to me. I was then, happily, well on the way to recovery, able to sit up, smoke my head off and what’s more . . . go to the toilet on my own. My good friend the Ward Sister was due to return to the United Kingdom and the newly arrived Sister was being introduced to each case by the Medical Officer. They eventually got to my bed, where I was sitting up, looking a picture of health. I can’t remember the M.O.’s name, but I can still picture him. He was a Captain, about thirty years of age, slightly built, with dark hair, a small moustache, and he wore spectacles. Not much given to humour, but now he beamed at me.

“Now, Sister,” he said, “this is our proudest case. We had actually given this chap up at one time.” I felt my jaw drop. “Pardon?” I spluttered.

“Oh yes!” he continued “Naturally we didn’t tell you but you certainly gave use a fright. It was a bit touch and go for a while.” They moved on.

As I pondered this remarkable piece of news, various happenings, which at the time of my admittance had puzzled me, began to make sense. The extreme quietness of the ward, people talking in whispers mostly. My Commanding officer Colonel Ingham-Clarke, coming in to pay a visit almost every day. The visits from the lads from the unit most of whom I didn’t know and had never previously met. I could clearly recall the Medical officer, Matron, Ward Sister and the hospital Sergeant-Cook, all grouped around my bed, each trying to persuade me to eat, tempting me with all sorts of delicacies, but I didn’t want anything, except to be left alone. One of the terrible effects of dysentery is that you can easily lose the will to live and I had seen this happen. They managed to keep me alive but I must admit that I didn’t know much about how they did it. However, I lived and was eventually discharged from the hospital and returned to my unit, with whom I had spent only one night. Here I spent several months recuperating at one of our camps, Fort Singah, an old Maharati Fort some 4,500 feet above sea level, until, due to the efforts of my Commanding Officer, I was repatriated back to England.

I have had quite a number of upsets with the old tummy because it will never be quite right. However I am still alive and into my seventies now, but had it not been for the skill of the R.A.M.C. doctors and staff; the care and devotion of the officers and other ranks of the Queen Alexandra’s Army Nursing Corps; and people like Bill Aird and ‘Doc’ McCormack, it might not have been ‘almost, but not quite’.

My heartfelt thanks go to Neil Stuart for allowing me to reproduce his father's memoir on this website. Many thanks must also go to Pete Rogers from the CVA for helping me get permission in the first instance.

Copyright © Neil Stuart and Steve Fogden 2012.